User login

Counterintuitive findings for domestic violence during COVID-19

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has not increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, at least during the early stages of the pandemic, new research suggests.

In April 2020, investigators surveyed over 1,750 individuals in intimate partner relationships. The survey was drawn from social media and email distribution lists. The researchers found that, of the roughly one-fifth who screened positive for IPV, half stated that the degree of victimization had remained the same since the COVID-19 outbreak; 17% reported that it had worsened; and one third reported that it had gotten better.

Those who reported worsening victimization said that sexual and physical violence, in particular, were exacerbated early in the pandemic’s course.

“I was surprised by this finding, and we certainly were not expecting it – in fact, I expected that the vast majority of victims would report that victimization got worse during stay-at-home policies, but that wasn’t the case,” lead author Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“I think the biggest take-home message is that some victims got better, but the vast majority stayed the same. These victims, men and women, were isolated with their perpetrator during COVID-19, so she added.

The study was published online Sept. 1 in Injury Prevention.

‘Shadow pandemic?’

The World Health Organization called upon health care organizations to be prepared to curb a potential IPV “shadow pandemic” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, no study has specifically evaluated whether self-reported victimization, particularly with regard to the severity and type of abuse, changed during the early period after COVID-19 social distancing polices were mandated.

“We scrambled right away when the pandemic hit because it was a unique opportunity to examine how behaviors change due to early stay-at-home policies; and, as a violence and injury epidemiologist, I am always curious about IPV, and this was a small subanalysis of that larger question,” Dr. Jetelina said.

The researchers recruited participants through their university and private social media accounts as well as professional distribution lists. Of those who completed the survey, 1,759 (mean age, 42 years) reported that they currently had an intimate partner. These participants were included in the study.

IPV was determined using the five-item Extended Hurt, Insulted, Threatened, and Scream (E-HITS) construct. Respondents were asked how often their partner physically hurt them, insulted them, threatened them with harm, screamed or cursed at them, or forced them to engage in sexual activities.

Each item was answered using a 5-point Likert scale. Scores ranged from 1, indicating never, to 5, indicating frequently. Participants who scored ≥7 were considered IPV positive.

Participants were also asked whether IPV severity had gotten much/somewhat better, had remained the same, or had gotten somewhat/much worse.

First peek

Of the total sample, 18% screened positive for IPV. Of these, 54% reported that the victimization had remained the same, 17% reported that it had worsened, and 30% said it had improved.

The majority of IPV victims experienced being insulted (97%) or being screamed at (86%).

Among those who reported worsening of IPV, the risk for physical violence was 4.38 times higher than the risk for nonphysical victimization. The risk for sexual victimization was 2.31 times higher than the risk for nonsexual victimization.

Among those who reported that IPV had gotten better, the improvement was 3.47 times higher with regard to physical victimization, compared with nonphysical victimization. Dr. Jetelina acknowledged that the findings cannot be generalized to the broader population.

“This was a convenience sample, but it is the first peek into what is happening behind closed doors and a first step to hearing collecting data from the victims themselves to better understand this ‘shadow pandemic’ and inform creative efforts to create better services for them while they are in isolation,” she said.

Lethality indicators

Commenting on the study, Peter Cronholm, MD, MSCE, associate professor of family medicine and community health at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned the use of a score of 7 on the E-HITS screen to determine the presence of IPV.

“I think there are other thresholds that might be important, and even low levels of sexual violence may be different than higher levels of emotional violence,” said Dr. Cronholm, who was not involved with the study.

“Someone may have been sexually assaulted frequently but not cross the threshold, so I think it would have been helpful for the researchers to look at different types of violence,” he said.

Also commenting on the study, Jessica Palardy, LSW, program supervisor at STOP Intimate Partner Violence, Philadelphia, said, the findings “solidify a trend we sensed was happening but couldn’t confirm.”

She said her agency’s clients “have had a wide variety of experiences, in terms of increases or decreases in victimization.”

Some clients were able to use the quarantine as an excuse to stay with family or friends and so could avoid seeing their partners. “Others indicated that because their partners were distracted by figuring out a new method of work, the tension shifted away from the victim,” said Ms. Palardy, who was not involved in the research.

“For those who saw an increase in victimization, we noticed that this increase also came with an increase in lethality indicators, such as strangulation, physical violence, use of weapons and substances, etc,” she said.

She emphasized that it is critical to screen people for IPV to ensure their safety.

“The goal is to connect people with resources before they are in a more lethal situation so that they can increase their safety and know their options,” Ms. Palardy said.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline and the Crisis Text Line are two sources of support for IPV victims.

Dr. Jetelina and coauthors, Dr. Cronholm, and Ms. Palardy reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has not increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, at least during the early stages of the pandemic, new research suggests.

In April 2020, investigators surveyed over 1,750 individuals in intimate partner relationships. The survey was drawn from social media and email distribution lists. The researchers found that, of the roughly one-fifth who screened positive for IPV, half stated that the degree of victimization had remained the same since the COVID-19 outbreak; 17% reported that it had worsened; and one third reported that it had gotten better.

Those who reported worsening victimization said that sexual and physical violence, in particular, were exacerbated early in the pandemic’s course.

“I was surprised by this finding, and we certainly were not expecting it – in fact, I expected that the vast majority of victims would report that victimization got worse during stay-at-home policies, but that wasn’t the case,” lead author Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“I think the biggest take-home message is that some victims got better, but the vast majority stayed the same. These victims, men and women, were isolated with their perpetrator during COVID-19, so she added.

The study was published online Sept. 1 in Injury Prevention.

‘Shadow pandemic?’

The World Health Organization called upon health care organizations to be prepared to curb a potential IPV “shadow pandemic” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, no study has specifically evaluated whether self-reported victimization, particularly with regard to the severity and type of abuse, changed during the early period after COVID-19 social distancing polices were mandated.

“We scrambled right away when the pandemic hit because it was a unique opportunity to examine how behaviors change due to early stay-at-home policies; and, as a violence and injury epidemiologist, I am always curious about IPV, and this was a small subanalysis of that larger question,” Dr. Jetelina said.

The researchers recruited participants through their university and private social media accounts as well as professional distribution lists. Of those who completed the survey, 1,759 (mean age, 42 years) reported that they currently had an intimate partner. These participants were included in the study.

IPV was determined using the five-item Extended Hurt, Insulted, Threatened, and Scream (E-HITS) construct. Respondents were asked how often their partner physically hurt them, insulted them, threatened them with harm, screamed or cursed at them, or forced them to engage in sexual activities.

Each item was answered using a 5-point Likert scale. Scores ranged from 1, indicating never, to 5, indicating frequently. Participants who scored ≥7 were considered IPV positive.

Participants were also asked whether IPV severity had gotten much/somewhat better, had remained the same, or had gotten somewhat/much worse.

First peek

Of the total sample, 18% screened positive for IPV. Of these, 54% reported that the victimization had remained the same, 17% reported that it had worsened, and 30% said it had improved.

The majority of IPV victims experienced being insulted (97%) or being screamed at (86%).

Among those who reported worsening of IPV, the risk for physical violence was 4.38 times higher than the risk for nonphysical victimization. The risk for sexual victimization was 2.31 times higher than the risk for nonsexual victimization.

Among those who reported that IPV had gotten better, the improvement was 3.47 times higher with regard to physical victimization, compared with nonphysical victimization. Dr. Jetelina acknowledged that the findings cannot be generalized to the broader population.

“This was a convenience sample, but it is the first peek into what is happening behind closed doors and a first step to hearing collecting data from the victims themselves to better understand this ‘shadow pandemic’ and inform creative efforts to create better services for them while they are in isolation,” she said.

Lethality indicators

Commenting on the study, Peter Cronholm, MD, MSCE, associate professor of family medicine and community health at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned the use of a score of 7 on the E-HITS screen to determine the presence of IPV.

“I think there are other thresholds that might be important, and even low levels of sexual violence may be different than higher levels of emotional violence,” said Dr. Cronholm, who was not involved with the study.

“Someone may have been sexually assaulted frequently but not cross the threshold, so I think it would have been helpful for the researchers to look at different types of violence,” he said.

Also commenting on the study, Jessica Palardy, LSW, program supervisor at STOP Intimate Partner Violence, Philadelphia, said, the findings “solidify a trend we sensed was happening but couldn’t confirm.”

She said her agency’s clients “have had a wide variety of experiences, in terms of increases or decreases in victimization.”

Some clients were able to use the quarantine as an excuse to stay with family or friends and so could avoid seeing their partners. “Others indicated that because their partners were distracted by figuring out a new method of work, the tension shifted away from the victim,” said Ms. Palardy, who was not involved in the research.

“For those who saw an increase in victimization, we noticed that this increase also came with an increase in lethality indicators, such as strangulation, physical violence, use of weapons and substances, etc,” she said.

She emphasized that it is critical to screen people for IPV to ensure their safety.

“The goal is to connect people with resources before they are in a more lethal situation so that they can increase their safety and know their options,” Ms. Palardy said.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline and the Crisis Text Line are two sources of support for IPV victims.

Dr. Jetelina and coauthors, Dr. Cronholm, and Ms. Palardy reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has not increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, at least during the early stages of the pandemic, new research suggests.

In April 2020, investigators surveyed over 1,750 individuals in intimate partner relationships. The survey was drawn from social media and email distribution lists. The researchers found that, of the roughly one-fifth who screened positive for IPV, half stated that the degree of victimization had remained the same since the COVID-19 outbreak; 17% reported that it had worsened; and one third reported that it had gotten better.

Those who reported worsening victimization said that sexual and physical violence, in particular, were exacerbated early in the pandemic’s course.

“I was surprised by this finding, and we certainly were not expecting it – in fact, I expected that the vast majority of victims would report that victimization got worse during stay-at-home policies, but that wasn’t the case,” lead author Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“I think the biggest take-home message is that some victims got better, but the vast majority stayed the same. These victims, men and women, were isolated with their perpetrator during COVID-19, so she added.

The study was published online Sept. 1 in Injury Prevention.

‘Shadow pandemic?’

The World Health Organization called upon health care organizations to be prepared to curb a potential IPV “shadow pandemic” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, no study has specifically evaluated whether self-reported victimization, particularly with regard to the severity and type of abuse, changed during the early period after COVID-19 social distancing polices were mandated.

“We scrambled right away when the pandemic hit because it was a unique opportunity to examine how behaviors change due to early stay-at-home policies; and, as a violence and injury epidemiologist, I am always curious about IPV, and this was a small subanalysis of that larger question,” Dr. Jetelina said.

The researchers recruited participants through their university and private social media accounts as well as professional distribution lists. Of those who completed the survey, 1,759 (mean age, 42 years) reported that they currently had an intimate partner. These participants were included in the study.

IPV was determined using the five-item Extended Hurt, Insulted, Threatened, and Scream (E-HITS) construct. Respondents were asked how often their partner physically hurt them, insulted them, threatened them with harm, screamed or cursed at them, or forced them to engage in sexual activities.

Each item was answered using a 5-point Likert scale. Scores ranged from 1, indicating never, to 5, indicating frequently. Participants who scored ≥7 were considered IPV positive.

Participants were also asked whether IPV severity had gotten much/somewhat better, had remained the same, or had gotten somewhat/much worse.

First peek

Of the total sample, 18% screened positive for IPV. Of these, 54% reported that the victimization had remained the same, 17% reported that it had worsened, and 30% said it had improved.

The majority of IPV victims experienced being insulted (97%) or being screamed at (86%).

Among those who reported worsening of IPV, the risk for physical violence was 4.38 times higher than the risk for nonphysical victimization. The risk for sexual victimization was 2.31 times higher than the risk for nonsexual victimization.

Among those who reported that IPV had gotten better, the improvement was 3.47 times higher with regard to physical victimization, compared with nonphysical victimization. Dr. Jetelina acknowledged that the findings cannot be generalized to the broader population.

“This was a convenience sample, but it is the first peek into what is happening behind closed doors and a first step to hearing collecting data from the victims themselves to better understand this ‘shadow pandemic’ and inform creative efforts to create better services for them while they are in isolation,” she said.

Lethality indicators

Commenting on the study, Peter Cronholm, MD, MSCE, associate professor of family medicine and community health at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned the use of a score of 7 on the E-HITS screen to determine the presence of IPV.

“I think there are other thresholds that might be important, and even low levels of sexual violence may be different than higher levels of emotional violence,” said Dr. Cronholm, who was not involved with the study.

“Someone may have been sexually assaulted frequently but not cross the threshold, so I think it would have been helpful for the researchers to look at different types of violence,” he said.

Also commenting on the study, Jessica Palardy, LSW, program supervisor at STOP Intimate Partner Violence, Philadelphia, said, the findings “solidify a trend we sensed was happening but couldn’t confirm.”

She said her agency’s clients “have had a wide variety of experiences, in terms of increases or decreases in victimization.”

Some clients were able to use the quarantine as an excuse to stay with family or friends and so could avoid seeing their partners. “Others indicated that because their partners were distracted by figuring out a new method of work, the tension shifted away from the victim,” said Ms. Palardy, who was not involved in the research.

“For those who saw an increase in victimization, we noticed that this increase also came with an increase in lethality indicators, such as strangulation, physical violence, use of weapons and substances, etc,” she said.

She emphasized that it is critical to screen people for IPV to ensure their safety.

“The goal is to connect people with resources before they are in a more lethal situation so that they can increase their safety and know their options,” Ms. Palardy said.

The National Domestic Violence Hotline and the Crisis Text Line are two sources of support for IPV victims.

Dr. Jetelina and coauthors, Dr. Cronholm, and Ms. Palardy reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Even in a virtual environment, the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons delivers without a “glitch”

Earlier this year, I was honored to serve as the Scientific Program Chair for the 46th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS). This year’s meeting was the first ever (and hopefully last) “virtual” scientific meeting, which consisted of a hybrid of prerecorded and live presentations. Although faculty and attendees were not able to be together physically, the essence of the lively SGS meetings came through loud and clear. We still had “discussants” comment on the oral presentations and ask questions of the presenters. These questions and answers were all done live—without a glitch! Many thanks to all who made this meeting possible.

In addition to the outstanding abstract and video presentations, there were 4 superb postgraduate courses:

- Mikio Nihira, MD, chaired “Enhanced recovery after surgery: Overcoming barriers to implementation.”

- Charles Hanes, MD, headed up “It’s all about the apex: The key to successful POP surgery.”

- Cara King, DO, MS, led “Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Pushing the envelope.”

- Vincent Lucente, MD, chaired “Transvaginal reconstructive pelvic surgery using graft augmentation post-FDA.”

Many special thanks to Dr. Lucente who transformed his course into a wonderful article for this special section of

One of our exceptional keynote speakers was Marc Beer (a serial entrepreneur and cofounder, chairman, and CEO of Renovia, Inc.), whose talk was entitled “A primer on medical device innovation—How to avoid common pitfalls while realizing your vision.” Mr. Beer has turned this topic into a unique article for this special section (see next month’s issue for Part 2).

Our TeLinde Lecture, entitled “Artificial intelligence in surgery,” was delivered by the dynamic Vicente Gracias, MD, professor of surgery at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, New Jersey. We also held 2 live panel discussions that were very popular. The first, “Work-life balance and gynecologic surgery,” featured various perspectives from Drs. Kristie Green, Sally Huber, Catherine Matthews, and Charles Rardin. The second panel discussion, entitled “Understanding, managing, and benefiting from your e-presence,” by experts Heather Schueppert; Chief Marketing Officer at Unified Physician Management, Brad Bowman, MD; and Peter Lotze, MD. Both of these panel discussions are included in this special section as well.

I hope you enjoy the content of this special section of

Earlier this year, I was honored to serve as the Scientific Program Chair for the 46th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS). This year’s meeting was the first ever (and hopefully last) “virtual” scientific meeting, which consisted of a hybrid of prerecorded and live presentations. Although faculty and attendees were not able to be together physically, the essence of the lively SGS meetings came through loud and clear. We still had “discussants” comment on the oral presentations and ask questions of the presenters. These questions and answers were all done live—without a glitch! Many thanks to all who made this meeting possible.

In addition to the outstanding abstract and video presentations, there were 4 superb postgraduate courses:

- Mikio Nihira, MD, chaired “Enhanced recovery after surgery: Overcoming barriers to implementation.”

- Charles Hanes, MD, headed up “It’s all about the apex: The key to successful POP surgery.”

- Cara King, DO, MS, led “Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Pushing the envelope.”

- Vincent Lucente, MD, chaired “Transvaginal reconstructive pelvic surgery using graft augmentation post-FDA.”

Many special thanks to Dr. Lucente who transformed his course into a wonderful article for this special section of

One of our exceptional keynote speakers was Marc Beer (a serial entrepreneur and cofounder, chairman, and CEO of Renovia, Inc.), whose talk was entitled “A primer on medical device innovation—How to avoid common pitfalls while realizing your vision.” Mr. Beer has turned this topic into a unique article for this special section (see next month’s issue for Part 2).

Our TeLinde Lecture, entitled “Artificial intelligence in surgery,” was delivered by the dynamic Vicente Gracias, MD, professor of surgery at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, New Jersey. We also held 2 live panel discussions that were very popular. The first, “Work-life balance and gynecologic surgery,” featured various perspectives from Drs. Kristie Green, Sally Huber, Catherine Matthews, and Charles Rardin. The second panel discussion, entitled “Understanding, managing, and benefiting from your e-presence,” by experts Heather Schueppert; Chief Marketing Officer at Unified Physician Management, Brad Bowman, MD; and Peter Lotze, MD. Both of these panel discussions are included in this special section as well.

I hope you enjoy the content of this special section of

Earlier this year, I was honored to serve as the Scientific Program Chair for the 46th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS). This year’s meeting was the first ever (and hopefully last) “virtual” scientific meeting, which consisted of a hybrid of prerecorded and live presentations. Although faculty and attendees were not able to be together physically, the essence of the lively SGS meetings came through loud and clear. We still had “discussants” comment on the oral presentations and ask questions of the presenters. These questions and answers were all done live—without a glitch! Many thanks to all who made this meeting possible.

In addition to the outstanding abstract and video presentations, there were 4 superb postgraduate courses:

- Mikio Nihira, MD, chaired “Enhanced recovery after surgery: Overcoming barriers to implementation.”

- Charles Hanes, MD, headed up “It’s all about the apex: The key to successful POP surgery.”

- Cara King, DO, MS, led “Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Pushing the envelope.”

- Vincent Lucente, MD, chaired “Transvaginal reconstructive pelvic surgery using graft augmentation post-FDA.”

Many special thanks to Dr. Lucente who transformed his course into a wonderful article for this special section of

One of our exceptional keynote speakers was Marc Beer (a serial entrepreneur and cofounder, chairman, and CEO of Renovia, Inc.), whose talk was entitled “A primer on medical device innovation—How to avoid common pitfalls while realizing your vision.” Mr. Beer has turned this topic into a unique article for this special section (see next month’s issue for Part 2).

Our TeLinde Lecture, entitled “Artificial intelligence in surgery,” was delivered by the dynamic Vicente Gracias, MD, professor of surgery at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, New Brunswick, New Jersey. We also held 2 live panel discussions that were very popular. The first, “Work-life balance and gynecologic surgery,” featured various perspectives from Drs. Kristie Green, Sally Huber, Catherine Matthews, and Charles Rardin. The second panel discussion, entitled “Understanding, managing, and benefiting from your e-presence,” by experts Heather Schueppert; Chief Marketing Officer at Unified Physician Management, Brad Bowman, MD; and Peter Lotze, MD. Both of these panel discussions are included in this special section as well.

I hope you enjoy the content of this special section of

Large waistline linked to higher risk of prostate cancer death

Men with prostate cancer may be wise to watch their waistlines, according to the findings of a large observational study in which patients with the highest waist measurements had a higher chance of dying from prostate cancer.

Researchers found that, over a 10.8-year period, men with the largest waist circumferences appeared 35% more likely to die from prostate cancer, when compared to men with the smallest waist circumferences (hazard ratio = 1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.73).

Men in the highest quartile for waist-to-hip ratio measurements also had a 34% higher risk of dying from prostate cancer, when compared to men in the lowest quartile (HR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.04–1.72).

There was no association between the total body fat percentage (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.79–1.28) or body mass index (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.78–1.28) and the risk for prostate cancer death.

The findings – reported in a late-breaking poster at the European and International Conference on Obesity (ECOICO) – provide further insight into how fat and its distribution may be associated with prostate cancer death.

A ‘complex’ relationship

“Obesity is a known risk factor for many cancer sites, but its association with prostate cancer is less clear. It’s very complex,” said study investigator Aurora Pérez-Cornago, PhD, a nutritional epidemiologist in the Nuffield Department of Population Health at University of Oxford, England.

Three years ago, Dr. Pérez-Cornago and collaborators looked for risk factors for prostate cancer among men who had volunteered to participate in the prospective UK Biobank cohort study.

One of the group’s findings was that excess adiposity and body fat were not associated with an increase in the development of prostate cancer (Br J Cancer. 2017 Nov 7;117[10]:1562-71). In fact, these factors were associated with a lower risk. This inverse association likely had more to do with prostate-specific antigen screening than a true effect of body weight, as men with obesity were potentially less likely to be screened or have lower prostate-specific antigen levels, Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

For the present study, attention was turned to men with aggressive prostate tumors as “these are the kind of tumors we are more interested in because they are the ones that can kill these men,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

There was also previous evidence suggesting that adiposity may be associated with a higher risk of aggressive disease.

Data on 218,225 men with no previous cancer when they enrolled in the UK Biobank cohort study were linked to health care administrative databases that provided information on prostate cancer deaths. This showed that 571 men died from prostate cancer over a 10.8-year follow-up period.

“When we looked at the association of adiposity measurements – we looked at [body mass index] and body fat percentage as markers of total adiposity, and waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as markers of central adiposity – we found that the association seems to be more specific for fat located around the waist,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

“Excessive fat accumulation around your belly is likely to be visceral fat, which may induce metabolic and hormonal dysfunction that, in turn, may help prostate cancer cells to develop and to progress,” she added.

Study strengths and next steps

As this was an observational study, the researchers could not confirm a causal association between central adiposity and prostate cancer death. That is why Dr. Perez-Cornago and collaborators plan to do further work that will include biomarker studies. The team also will look at stage and grade data when available in the UK Biobank.

“There is strong evidence that men with greater body fat are at a higher risk of advanced and fatal prostate cancer. It is time to build on this,” said Barbra Dickerman, PhD, who has looked at the relationship between obesity and prostate cancer progression (Cancer. 2019 Aug 15;125[16]:2877-85).

“First, predictive analyses of directly measured body fat distribution may sharpen our view of who is at the highest risk,” observed Dr. Dickerman, a research fellow in the department of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

“Second, causal analyses of precisely defined energy balance strategies may help to identify targeted prevention strategies that minimize that risk,” she added.

One of the strengths of Dr. Pérez-Cornago’s work was that it used data from a large, prospective study to examine the link between adiposity and the risk of fatal prostate cancer, observed Ying Wang, PhD, a senior principal scientist of epidemiology research at The American Cancer Society.

“In addition to the large sample size, anthropometric measurements were obtained by trained research clinic staff rather than self-reported by participants, which is a strength compared with many other studies,” Dr. Wang noted.

Furthermore, Dr. Wang said, “The study was also able to control for multiple confounders, including lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical activity. Future studies need to confirm their findings.”

The study was supported by a fellowship from Cancer Research UK. The investigators, Dr. Dickerman, and Dr. Wang had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Pérez-Cornago A et al. ECOICO 2020. LBP-075.

Men with prostate cancer may be wise to watch their waistlines, according to the findings of a large observational study in which patients with the highest waist measurements had a higher chance of dying from prostate cancer.

Researchers found that, over a 10.8-year period, men with the largest waist circumferences appeared 35% more likely to die from prostate cancer, when compared to men with the smallest waist circumferences (hazard ratio = 1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.73).

Men in the highest quartile for waist-to-hip ratio measurements also had a 34% higher risk of dying from prostate cancer, when compared to men in the lowest quartile (HR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.04–1.72).

There was no association between the total body fat percentage (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.79–1.28) or body mass index (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.78–1.28) and the risk for prostate cancer death.

The findings – reported in a late-breaking poster at the European and International Conference on Obesity (ECOICO) – provide further insight into how fat and its distribution may be associated with prostate cancer death.

A ‘complex’ relationship

“Obesity is a known risk factor for many cancer sites, but its association with prostate cancer is less clear. It’s very complex,” said study investigator Aurora Pérez-Cornago, PhD, a nutritional epidemiologist in the Nuffield Department of Population Health at University of Oxford, England.

Three years ago, Dr. Pérez-Cornago and collaborators looked for risk factors for prostate cancer among men who had volunteered to participate in the prospective UK Biobank cohort study.

One of the group’s findings was that excess adiposity and body fat were not associated with an increase in the development of prostate cancer (Br J Cancer. 2017 Nov 7;117[10]:1562-71). In fact, these factors were associated with a lower risk. This inverse association likely had more to do with prostate-specific antigen screening than a true effect of body weight, as men with obesity were potentially less likely to be screened or have lower prostate-specific antigen levels, Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

For the present study, attention was turned to men with aggressive prostate tumors as “these are the kind of tumors we are more interested in because they are the ones that can kill these men,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

There was also previous evidence suggesting that adiposity may be associated with a higher risk of aggressive disease.

Data on 218,225 men with no previous cancer when they enrolled in the UK Biobank cohort study were linked to health care administrative databases that provided information on prostate cancer deaths. This showed that 571 men died from prostate cancer over a 10.8-year follow-up period.

“When we looked at the association of adiposity measurements – we looked at [body mass index] and body fat percentage as markers of total adiposity, and waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as markers of central adiposity – we found that the association seems to be more specific for fat located around the waist,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

“Excessive fat accumulation around your belly is likely to be visceral fat, which may induce metabolic and hormonal dysfunction that, in turn, may help prostate cancer cells to develop and to progress,” she added.

Study strengths and next steps

As this was an observational study, the researchers could not confirm a causal association between central adiposity and prostate cancer death. That is why Dr. Perez-Cornago and collaborators plan to do further work that will include biomarker studies. The team also will look at stage and grade data when available in the UK Biobank.

“There is strong evidence that men with greater body fat are at a higher risk of advanced and fatal prostate cancer. It is time to build on this,” said Barbra Dickerman, PhD, who has looked at the relationship between obesity and prostate cancer progression (Cancer. 2019 Aug 15;125[16]:2877-85).

“First, predictive analyses of directly measured body fat distribution may sharpen our view of who is at the highest risk,” observed Dr. Dickerman, a research fellow in the department of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

“Second, causal analyses of precisely defined energy balance strategies may help to identify targeted prevention strategies that minimize that risk,” she added.

One of the strengths of Dr. Pérez-Cornago’s work was that it used data from a large, prospective study to examine the link between adiposity and the risk of fatal prostate cancer, observed Ying Wang, PhD, a senior principal scientist of epidemiology research at The American Cancer Society.

“In addition to the large sample size, anthropometric measurements were obtained by trained research clinic staff rather than self-reported by participants, which is a strength compared with many other studies,” Dr. Wang noted.

Furthermore, Dr. Wang said, “The study was also able to control for multiple confounders, including lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical activity. Future studies need to confirm their findings.”

The study was supported by a fellowship from Cancer Research UK. The investigators, Dr. Dickerman, and Dr. Wang had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Pérez-Cornago A et al. ECOICO 2020. LBP-075.

Men with prostate cancer may be wise to watch their waistlines, according to the findings of a large observational study in which patients with the highest waist measurements had a higher chance of dying from prostate cancer.

Researchers found that, over a 10.8-year period, men with the largest waist circumferences appeared 35% more likely to die from prostate cancer, when compared to men with the smallest waist circumferences (hazard ratio = 1.35, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05–1.73).

Men in the highest quartile for waist-to-hip ratio measurements also had a 34% higher risk of dying from prostate cancer, when compared to men in the lowest quartile (HR = 1.34, 95% CI, 1.04–1.72).

There was no association between the total body fat percentage (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.79–1.28) or body mass index (HR = 1.00, 95% CI, 0.78–1.28) and the risk for prostate cancer death.

The findings – reported in a late-breaking poster at the European and International Conference on Obesity (ECOICO) – provide further insight into how fat and its distribution may be associated with prostate cancer death.

A ‘complex’ relationship

“Obesity is a known risk factor for many cancer sites, but its association with prostate cancer is less clear. It’s very complex,” said study investigator Aurora Pérez-Cornago, PhD, a nutritional epidemiologist in the Nuffield Department of Population Health at University of Oxford, England.

Three years ago, Dr. Pérez-Cornago and collaborators looked for risk factors for prostate cancer among men who had volunteered to participate in the prospective UK Biobank cohort study.

One of the group’s findings was that excess adiposity and body fat were not associated with an increase in the development of prostate cancer (Br J Cancer. 2017 Nov 7;117[10]:1562-71). In fact, these factors were associated with a lower risk. This inverse association likely had more to do with prostate-specific antigen screening than a true effect of body weight, as men with obesity were potentially less likely to be screened or have lower prostate-specific antigen levels, Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

For the present study, attention was turned to men with aggressive prostate tumors as “these are the kind of tumors we are more interested in because they are the ones that can kill these men,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

There was also previous evidence suggesting that adiposity may be associated with a higher risk of aggressive disease.

Data on 218,225 men with no previous cancer when they enrolled in the UK Biobank cohort study were linked to health care administrative databases that provided information on prostate cancer deaths. This showed that 571 men died from prostate cancer over a 10.8-year follow-up period.

“When we looked at the association of adiposity measurements – we looked at [body mass index] and body fat percentage as markers of total adiposity, and waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as markers of central adiposity – we found that the association seems to be more specific for fat located around the waist,” Dr. Pérez-Cornago said.

“Excessive fat accumulation around your belly is likely to be visceral fat, which may induce metabolic and hormonal dysfunction that, in turn, may help prostate cancer cells to develop and to progress,” she added.

Study strengths and next steps

As this was an observational study, the researchers could not confirm a causal association between central adiposity and prostate cancer death. That is why Dr. Perez-Cornago and collaborators plan to do further work that will include biomarker studies. The team also will look at stage and grade data when available in the UK Biobank.

“There is strong evidence that men with greater body fat are at a higher risk of advanced and fatal prostate cancer. It is time to build on this,” said Barbra Dickerman, PhD, who has looked at the relationship between obesity and prostate cancer progression (Cancer. 2019 Aug 15;125[16]:2877-85).

“First, predictive analyses of directly measured body fat distribution may sharpen our view of who is at the highest risk,” observed Dr. Dickerman, a research fellow in the department of epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

“Second, causal analyses of precisely defined energy balance strategies may help to identify targeted prevention strategies that minimize that risk,” she added.

One of the strengths of Dr. Pérez-Cornago’s work was that it used data from a large, prospective study to examine the link between adiposity and the risk of fatal prostate cancer, observed Ying Wang, PhD, a senior principal scientist of epidemiology research at The American Cancer Society.

“In addition to the large sample size, anthropometric measurements were obtained by trained research clinic staff rather than self-reported by participants, which is a strength compared with many other studies,” Dr. Wang noted.

Furthermore, Dr. Wang said, “The study was also able to control for multiple confounders, including lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical activity. Future studies need to confirm their findings.”

The study was supported by a fellowship from Cancer Research UK. The investigators, Dr. Dickerman, and Dr. Wang had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Pérez-Cornago A et al. ECOICO 2020. LBP-075.

FROM ECOICO 2020

COVID-19 and Blood Clots: Inside the Battle to Save Patients

Abnormal coagulation is a hallmark of COVID-19. Now, as we’re learning more about the high risk of thrombosis, physicians need to prescribe prophylaxis routinely in the hospital, stay alert, and act immediately when signs of trouble appear. “We must have a low suspicion for diagnosis and treatment of thrombosis,” said hematologist-oncologist Thomas DeLoughery, MD, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland in a presentation at the virtual 2020 annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

Still, research is sparse, and there are disagreements about the best strategies to protect patients, said DeLoughery. Physicians recognized coagulation problems early on during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, and they’re very common. According to DeLoughery, most patients have abnormal coagulation, very high D-dimer test results, and very high fibrinogen levels—even to the extraordinary level of 1,500 mg/dL, he said. And unlike in typical patients with septic shock, patients with thrombosis have a higher risk than bleeding.

A high D-dimer level is a major prognostic indicator of thrombosis and bad outcomes. “It’s representative of widespread coagulation activation, and it can be a sign of pulmonary thrombosis and local thrombosis happening at the site of the COVID infection,” he said.

DeLoughery highlighted an April 2020 study that found that “patients with D‐dimer levels ≥ 2.0 µg/mL had a higher incidence of mortality when compared with those who with D‐dimer levels < 2.0 µg/mL (12/67 vs 1/267; P < .001; hazard ratio, 51.5; 95% CI, 12.9‐206.7).”

Research also suggests that “there's something about getting COVID and going to the intensive care unit (ICU) that dramatically raises the risk of thrombosis,” he said, and the risk goes up over time in the ICU. Venous thrombosis isn’t the only risk. Relatively young patients with COVID have suffered from arterial thrombosis, even though they have minimal to no respiratory symptoms and no cardiovascular risk factors.

As for treatments, DeLoughery noted that thrombosis can occur despite standard prophylaxis, and patients may show resistance to heparin and, therefore, need massive doses. Still, there’s consensus that every patient with COVID-19 in the hospital should get thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), he said, and unfractionated heparin is appropriate for those with renal failure.

“The problem is everything else is controversial,” he said. For example, hematologists are split evenly on whether heparin dosing should be increased beyond standard protocol for patients in the ICU with 1.5 to 3 times normal D-dimers levels. He agreed with this approach but notes that some centers set their D-dimer triggers higher—at 3 to 6 times the normal level.

“The problem is that there’s limited data,” he said. “We have lots of observational studies suggesting benefits from higher doses, but we have no randomized trial data, and the observational studies are not uniform in their recommendations.”

What about outpatient prophylaxis? It appears that risk of thrombosis is < 1% percent when patients are out of the hospital, he said. “This is very reassuring that once the patient gets better, their prothrombotic drive goes away.”

Dr. DeLoughery highlighted the protocol at Oregon Health & Science University:

- Prophylaxis. Everyone with COVID-19 admitted to the hospital receives enoxaparin 40 mg daily. If the patient’s body mass index > 40, it should be increased to twice daily. For patients with renal failure, use unfractionated heparin 5000 u twice daily or enoxaparin 30 mg daily.

- In the ICU. Screen for deep vein thrombosis at admission and every 4 to 5 days thereafter. Increase enoxaparin to 40 mg twice daily, and to 1 mg/kg twice daily if signs of thrombosis develop, such as sudden deterioration, respiratory failure, the patient is too unstable to get a computed tomography, or with D-dimer > 3.0 µg/mL. “People’s thresholds for initiating empiric therapy differ, but this is an option,” he said.

For outpatient patients who are likely to be immobile for a month, 40 mg enoxaparin or 10 mg rivaroxaban are appropriate. “We’re not as aggressive as we used to be about outpatient prophylaxis,” he said.

Moving forward, he said, “this is an area where we really need clinical trials. There's just so much uncertainty.”

DeLoughery reported no disclosures.

Abnormal coagulation is a hallmark of COVID-19. Now, as we’re learning more about the high risk of thrombosis, physicians need to prescribe prophylaxis routinely in the hospital, stay alert, and act immediately when signs of trouble appear. “We must have a low suspicion for diagnosis and treatment of thrombosis,” said hematologist-oncologist Thomas DeLoughery, MD, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland in a presentation at the virtual 2020 annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

Still, research is sparse, and there are disagreements about the best strategies to protect patients, said DeLoughery. Physicians recognized coagulation problems early on during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, and they’re very common. According to DeLoughery, most patients have abnormal coagulation, very high D-dimer test results, and very high fibrinogen levels—even to the extraordinary level of 1,500 mg/dL, he said. And unlike in typical patients with septic shock, patients with thrombosis have a higher risk than bleeding.

A high D-dimer level is a major prognostic indicator of thrombosis and bad outcomes. “It’s representative of widespread coagulation activation, and it can be a sign of pulmonary thrombosis and local thrombosis happening at the site of the COVID infection,” he said.

DeLoughery highlighted an April 2020 study that found that “patients with D‐dimer levels ≥ 2.0 µg/mL had a higher incidence of mortality when compared with those who with D‐dimer levels < 2.0 µg/mL (12/67 vs 1/267; P < .001; hazard ratio, 51.5; 95% CI, 12.9‐206.7).”

Research also suggests that “there's something about getting COVID and going to the intensive care unit (ICU) that dramatically raises the risk of thrombosis,” he said, and the risk goes up over time in the ICU. Venous thrombosis isn’t the only risk. Relatively young patients with COVID have suffered from arterial thrombosis, even though they have minimal to no respiratory symptoms and no cardiovascular risk factors.

As for treatments, DeLoughery noted that thrombosis can occur despite standard prophylaxis, and patients may show resistance to heparin and, therefore, need massive doses. Still, there’s consensus that every patient with COVID-19 in the hospital should get thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), he said, and unfractionated heparin is appropriate for those with renal failure.

“The problem is everything else is controversial,” he said. For example, hematologists are split evenly on whether heparin dosing should be increased beyond standard protocol for patients in the ICU with 1.5 to 3 times normal D-dimers levels. He agreed with this approach but notes that some centers set their D-dimer triggers higher—at 3 to 6 times the normal level.

“The problem is that there’s limited data,” he said. “We have lots of observational studies suggesting benefits from higher doses, but we have no randomized trial data, and the observational studies are not uniform in their recommendations.”

What about outpatient prophylaxis? It appears that risk of thrombosis is < 1% percent when patients are out of the hospital, he said. “This is very reassuring that once the patient gets better, their prothrombotic drive goes away.”

Dr. DeLoughery highlighted the protocol at Oregon Health & Science University:

- Prophylaxis. Everyone with COVID-19 admitted to the hospital receives enoxaparin 40 mg daily. If the patient’s body mass index > 40, it should be increased to twice daily. For patients with renal failure, use unfractionated heparin 5000 u twice daily or enoxaparin 30 mg daily.

- In the ICU. Screen for deep vein thrombosis at admission and every 4 to 5 days thereafter. Increase enoxaparin to 40 mg twice daily, and to 1 mg/kg twice daily if signs of thrombosis develop, such as sudden deterioration, respiratory failure, the patient is too unstable to get a computed tomography, or with D-dimer > 3.0 µg/mL. “People’s thresholds for initiating empiric therapy differ, but this is an option,” he said.

For outpatient patients who are likely to be immobile for a month, 40 mg enoxaparin or 10 mg rivaroxaban are appropriate. “We’re not as aggressive as we used to be about outpatient prophylaxis,” he said.

Moving forward, he said, “this is an area where we really need clinical trials. There's just so much uncertainty.”

DeLoughery reported no disclosures.

Abnormal coagulation is a hallmark of COVID-19. Now, as we’re learning more about the high risk of thrombosis, physicians need to prescribe prophylaxis routinely in the hospital, stay alert, and act immediately when signs of trouble appear. “We must have a low suspicion for diagnosis and treatment of thrombosis,” said hematologist-oncologist Thomas DeLoughery, MD, professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland in a presentation at the virtual 2020 annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO).

Still, research is sparse, and there are disagreements about the best strategies to protect patients, said DeLoughery. Physicians recognized coagulation problems early on during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, and they’re very common. According to DeLoughery, most patients have abnormal coagulation, very high D-dimer test results, and very high fibrinogen levels—even to the extraordinary level of 1,500 mg/dL, he said. And unlike in typical patients with septic shock, patients with thrombosis have a higher risk than bleeding.

A high D-dimer level is a major prognostic indicator of thrombosis and bad outcomes. “It’s representative of widespread coagulation activation, and it can be a sign of pulmonary thrombosis and local thrombosis happening at the site of the COVID infection,” he said.

DeLoughery highlighted an April 2020 study that found that “patients with D‐dimer levels ≥ 2.0 µg/mL had a higher incidence of mortality when compared with those who with D‐dimer levels < 2.0 µg/mL (12/67 vs 1/267; P < .001; hazard ratio, 51.5; 95% CI, 12.9‐206.7).”

Research also suggests that “there's something about getting COVID and going to the intensive care unit (ICU) that dramatically raises the risk of thrombosis,” he said, and the risk goes up over time in the ICU. Venous thrombosis isn’t the only risk. Relatively young patients with COVID have suffered from arterial thrombosis, even though they have minimal to no respiratory symptoms and no cardiovascular risk factors.

As for treatments, DeLoughery noted that thrombosis can occur despite standard prophylaxis, and patients may show resistance to heparin and, therefore, need massive doses. Still, there’s consensus that every patient with COVID-19 in the hospital should get thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), he said, and unfractionated heparin is appropriate for those with renal failure.

“The problem is everything else is controversial,” he said. For example, hematologists are split evenly on whether heparin dosing should be increased beyond standard protocol for patients in the ICU with 1.5 to 3 times normal D-dimers levels. He agreed with this approach but notes that some centers set their D-dimer triggers higher—at 3 to 6 times the normal level.

“The problem is that there’s limited data,” he said. “We have lots of observational studies suggesting benefits from higher doses, but we have no randomized trial data, and the observational studies are not uniform in their recommendations.”

What about outpatient prophylaxis? It appears that risk of thrombosis is < 1% percent when patients are out of the hospital, he said. “This is very reassuring that once the patient gets better, their prothrombotic drive goes away.”

Dr. DeLoughery highlighted the protocol at Oregon Health & Science University:

- Prophylaxis. Everyone with COVID-19 admitted to the hospital receives enoxaparin 40 mg daily. If the patient’s body mass index > 40, it should be increased to twice daily. For patients with renal failure, use unfractionated heparin 5000 u twice daily or enoxaparin 30 mg daily.

- In the ICU. Screen for deep vein thrombosis at admission and every 4 to 5 days thereafter. Increase enoxaparin to 40 mg twice daily, and to 1 mg/kg twice daily if signs of thrombosis develop, such as sudden deterioration, respiratory failure, the patient is too unstable to get a computed tomography, or with D-dimer > 3.0 µg/mL. “People’s thresholds for initiating empiric therapy differ, but this is an option,” he said.

For outpatient patients who are likely to be immobile for a month, 40 mg enoxaparin or 10 mg rivaroxaban are appropriate. “We’re not as aggressive as we used to be about outpatient prophylaxis,” he said.

Moving forward, he said, “this is an area where we really need clinical trials. There's just so much uncertainty.”

DeLoughery reported no disclosures.

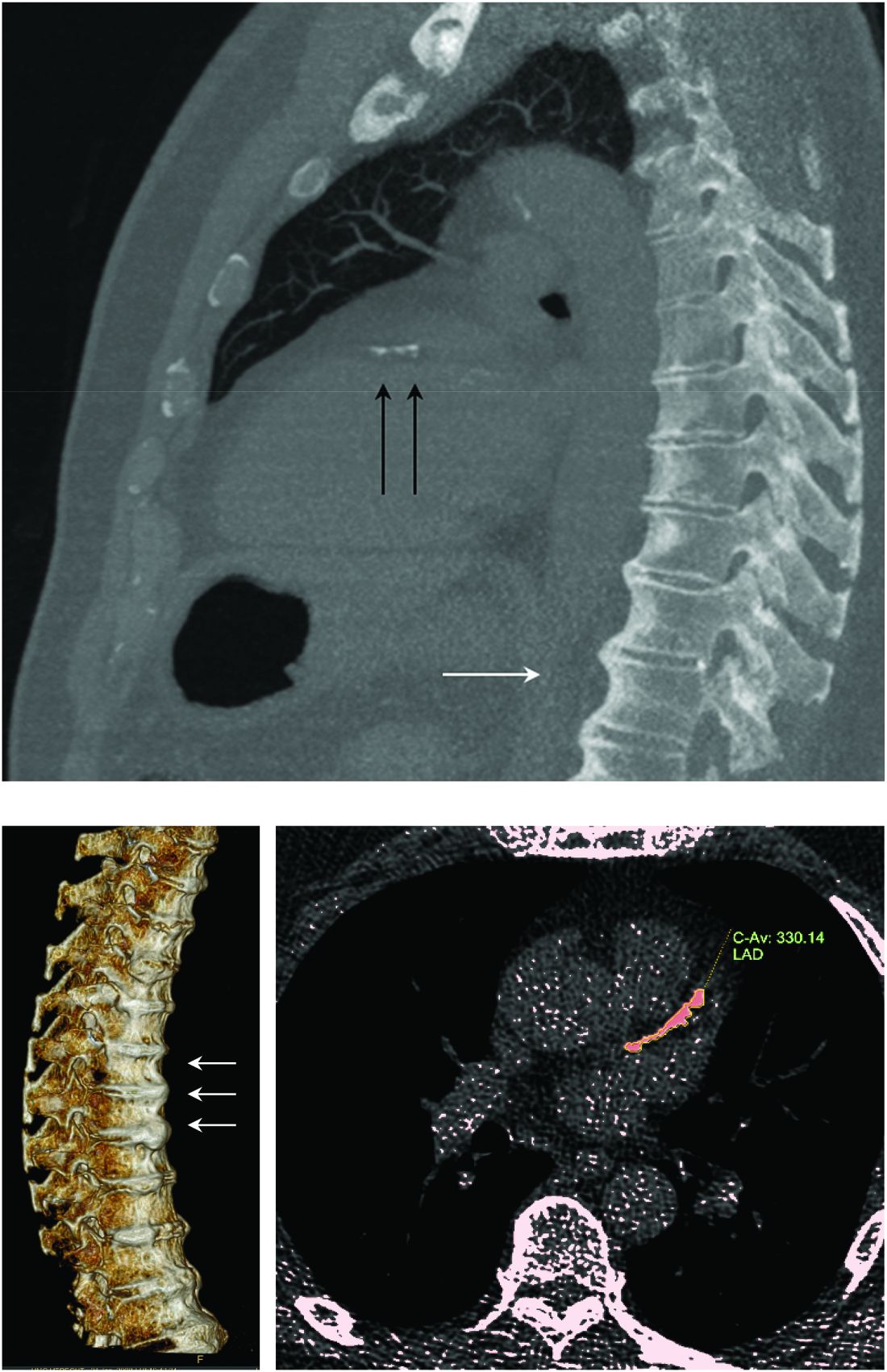

Trabecular bone loss may contribute to axial spondyloarthritis progression

A paper published in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism reports the outcomes of a prospective observational cohort study in 245 patients with axial spondyloarthritis that sought to identify possible predictors of spinal radiographic progression of the disease.

Joon-Yong Jung, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea, wrote that inflammation of the vertebrae is the first stage of progression of axial spondyloarthritis. One hypothesis is that this inflammation is associated with trabecular bone loss, which then leads to spinal instability, which in turns causes biomechanical stress on the area and the formation of new bone as syndesmophytes.

To evaluate the possible relationship between trabecular bone loss and syndesmophytes, researchers used dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry imaging of the lumbar spine, which can assess the microarchitecture of trabecular bone, as well as radiographs of the cervical and lumbar spine at 2 and 4 years of follow-up to assess the presence of syndesmophytes.

At baseline, 40% of patients had syndesmophytes, and the mean number of syndesmophytes was 3.3. A total of 11% of patients at baseline had mild trabecular bone loss, defined as trabecular bone score values between 1.230 and 1.310, and 10% had severe trabecular bone loss, with a score of 1.230 or less.

While on average patients had an increase of 1.41 syndesmophytes every 2 years during the study, patients with severe trabecular bone loss at baseline formed 1.26 more syndesmophytes every 2 years than did patients with normal trabecular bone loss score. After adjusting for variables such as disease activity and clinical factors, the authors found that both mild and severe trabecular bone loss were independently associated with progression of structural damage in the cervical and lumbar spine.

Patients with mild trabecular bone loss had a 120% greater odds of new syndesmophyte formation over the next 2 years, compared with those with normal trabecular bone loss scores, while those with severe loss had a 280% greater odds.

“The more severe the trabecular bone loss, the stronger the effect on the progression of the spine,” the authors wrote. Other factors associated with new syndesmophyte formation included higher C-reactive protein levels, longer symptom duration, smoking, and high NSAID index.

The study also pointed to an association between trabecular bone loss and modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score. Patients with severe trabecular bone loss showed an average increase of 0.37 in their modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score over 2 years, compared with patients with normal trabecular bone loss score at baseline, even after adjusting for confounders.

The authors commented that inflammation is hypothesized to lead to structural damage in two ways. “Inflammation-induced bone loss in the spine results in instability, another type of biomechanical stress, which then triggers a biomechanical response in an attempt to increase stability,” they wrote. Or inflammation leads to the formation of granulated repair tissue which then triggers new bone formation.

Whatever the mechanism, the authors said finding that trabecular bone loss is associated with disease progression suggests a possible use for the trabecular bone score as a practical and noninvasive means to predict spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis.

The study received no funding, and the authors said they had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Jung J-Y et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(5):827-33.

A paper published in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism reports the outcomes of a prospective observational cohort study in 245 patients with axial spondyloarthritis that sought to identify possible predictors of spinal radiographic progression of the disease.

Joon-Yong Jung, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea, wrote that inflammation of the vertebrae is the first stage of progression of axial spondyloarthritis. One hypothesis is that this inflammation is associated with trabecular bone loss, which then leads to spinal instability, which in turns causes biomechanical stress on the area and the formation of new bone as syndesmophytes.

To evaluate the possible relationship between trabecular bone loss and syndesmophytes, researchers used dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry imaging of the lumbar spine, which can assess the microarchitecture of trabecular bone, as well as radiographs of the cervical and lumbar spine at 2 and 4 years of follow-up to assess the presence of syndesmophytes.

At baseline, 40% of patients had syndesmophytes, and the mean number of syndesmophytes was 3.3. A total of 11% of patients at baseline had mild trabecular bone loss, defined as trabecular bone score values between 1.230 and 1.310, and 10% had severe trabecular bone loss, with a score of 1.230 or less.

While on average patients had an increase of 1.41 syndesmophytes every 2 years during the study, patients with severe trabecular bone loss at baseline formed 1.26 more syndesmophytes every 2 years than did patients with normal trabecular bone loss score. After adjusting for variables such as disease activity and clinical factors, the authors found that both mild and severe trabecular bone loss were independently associated with progression of structural damage in the cervical and lumbar spine.

Patients with mild trabecular bone loss had a 120% greater odds of new syndesmophyte formation over the next 2 years, compared with those with normal trabecular bone loss scores, while those with severe loss had a 280% greater odds.

“The more severe the trabecular bone loss, the stronger the effect on the progression of the spine,” the authors wrote. Other factors associated with new syndesmophyte formation included higher C-reactive protein levels, longer symptom duration, smoking, and high NSAID index.

The study also pointed to an association between trabecular bone loss and modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score. Patients with severe trabecular bone loss showed an average increase of 0.37 in their modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score over 2 years, compared with patients with normal trabecular bone loss score at baseline, even after adjusting for confounders.

The authors commented that inflammation is hypothesized to lead to structural damage in two ways. “Inflammation-induced bone loss in the spine results in instability, another type of biomechanical stress, which then triggers a biomechanical response in an attempt to increase stability,” they wrote. Or inflammation leads to the formation of granulated repair tissue which then triggers new bone formation.

Whatever the mechanism, the authors said finding that trabecular bone loss is associated with disease progression suggests a possible use for the trabecular bone score as a practical and noninvasive means to predict spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis.

The study received no funding, and the authors said they had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Jung J-Y et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(5):827-33.

A paper published in Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism reports the outcomes of a prospective observational cohort study in 245 patients with axial spondyloarthritis that sought to identify possible predictors of spinal radiographic progression of the disease.

Joon-Yong Jung, MD, PhD, and colleagues from the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea, wrote that inflammation of the vertebrae is the first stage of progression of axial spondyloarthritis. One hypothesis is that this inflammation is associated with trabecular bone loss, which then leads to spinal instability, which in turns causes biomechanical stress on the area and the formation of new bone as syndesmophytes.

To evaluate the possible relationship between trabecular bone loss and syndesmophytes, researchers used dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry imaging of the lumbar spine, which can assess the microarchitecture of trabecular bone, as well as radiographs of the cervical and lumbar spine at 2 and 4 years of follow-up to assess the presence of syndesmophytes.

At baseline, 40% of patients had syndesmophytes, and the mean number of syndesmophytes was 3.3. A total of 11% of patients at baseline had mild trabecular bone loss, defined as trabecular bone score values between 1.230 and 1.310, and 10% had severe trabecular bone loss, with a score of 1.230 or less.

While on average patients had an increase of 1.41 syndesmophytes every 2 years during the study, patients with severe trabecular bone loss at baseline formed 1.26 more syndesmophytes every 2 years than did patients with normal trabecular bone loss score. After adjusting for variables such as disease activity and clinical factors, the authors found that both mild and severe trabecular bone loss were independently associated with progression of structural damage in the cervical and lumbar spine.

Patients with mild trabecular bone loss had a 120% greater odds of new syndesmophyte formation over the next 2 years, compared with those with normal trabecular bone loss scores, while those with severe loss had a 280% greater odds.

“The more severe the trabecular bone loss, the stronger the effect on the progression of the spine,” the authors wrote. Other factors associated with new syndesmophyte formation included higher C-reactive protein levels, longer symptom duration, smoking, and high NSAID index.

The study also pointed to an association between trabecular bone loss and modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score. Patients with severe trabecular bone loss showed an average increase of 0.37 in their modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score over 2 years, compared with patients with normal trabecular bone loss score at baseline, even after adjusting for confounders.

The authors commented that inflammation is hypothesized to lead to structural damage in two ways. “Inflammation-induced bone loss in the spine results in instability, another type of biomechanical stress, which then triggers a biomechanical response in an attempt to increase stability,” they wrote. Or inflammation leads to the formation of granulated repair tissue which then triggers new bone formation.

Whatever the mechanism, the authors said finding that trabecular bone loss is associated with disease progression suggests a possible use for the trabecular bone score as a practical and noninvasive means to predict spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis.

The study received no funding, and the authors said they had no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCE: Jung J-Y et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(5):827-33.

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATISM

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis heart risk higher than expected

More people with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) develop cardiovascular disease (CVD) than is predicted by the Framingham Risk Score, results of an observational study have shown.

Notably, a higher rate of myocardial infarction (MI) was seen in those with DISH than in those without DISH over the 10-year follow-up period (24.4% vs. 4.3%; P = .0055).

“We propose more scrutiny is warranted in evaluating CV risk in these patients, more demanding treatment target goals should be established, and as a result, earlier and more aggressive preventive medical interventions instituted,” corresponding author Reuven Mader, MD, and associates wrote in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

“What Mader’s study is pointing out is that it’s worth the radiologist reporting [DISH],” Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD, from the National Jewish Health Center in Denver, said in an interview.

DISH on a chest x-ray or CT scan should be another “red flag to be even more attentive to cardiovascular risk,” she added, particularly because studies have shown that people with DISH tend to be obese, have metabolic syndrome, or diabetes – all of which independently increase their risk for cardiovascular disease.

An old condition often found by accident

Physicians have known about DISH for many years, Dr. Mader of Ha’Emek Medical Center in Afula, Israel, observed in an interview. Historical evidence suggests it was present more than a thousand years ago, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that it gained scientific interest. Originally coined Forestier’s disease, it was renamed DISH in the late 1960s following the realization that it was not limited to the spine.

“It is a condition which is characterized by new bone formation,” Dr. Mader explained. This new bone formation has some predilection for the entheses – the tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules, that attach to the bone.

“Diagnosis of the disease is based mainly on radiographs, especially of the thoracic spine, and it requires the formation of bridges that connect at least four contiguous vertebra,” he continued.

“The bridges are usually right-sided and usually the intervertebral spaces are spared. Classically there is no involvement of the sacroiliac joints, although there are some changes that might involve the sacroiliac joints but in a different manner than in inflammatory sacroiliitis.”

DISH was originally thought to be a pain syndrome, which has “not played out,” Dr. Regan noted in her interview. While there may be people who experience pain as a result of DISH, most cases are asymptomatic and usually picked up incidentally on a chest x-ray or CT scan.

“It’s something that’s not obvious,” she said. One of the main problems it can cause is stiffness and lack of mobility in the spine and this can lead to quite severe fractures in some cases, such as during a car accident. Hence spinal surgeons and other orthopedic specialists, such as Dr. Regan, have also taken an interest in the condition.

“Apart from the thoracic spine, DISH may also involve the cervical spine; there have been many reports about difficulty in swallowing, breathing, and in the lumbar spine, spinal stenosis and so forth,” Dr. Mader said. The differential diagnosis includes ankylosing spondylitis, although there is some evidence that the two can coexist.

“The diagnosis depends on the alertness of the examining physician,” he added, noting that rheumatologists and other specialists would be “very aware of this condition” and “sensitive to changes that we see when we examine these patients.”

DISH and heightened cardiovascular risk

Previous work by Dr. Mader and associates has shown that people with DISH are more often affected by the metabolic syndrome than are those without DISH. The cross-sectional study had excluded those with preexisting CVD and found that people with DISH had a significantly higher Framingham Risk Score, compared with a control group of people with osteoarthritis and no DISH (P = .004), which in turn meant they had a significantly (P = .007) higher 10-year risk for developing CVD.

The aim of their most recent study was to compare the actual rate of CV events in 2016 versus those predicted by the Framingham Risk Score in 2006. To do this, they compared the available electronic medical records of 45 individuals with DISH and 47 without it.

The results showed that almost 39% of people with DISH had developed CVD, whereas the Framingham Risk Score had estimated that just under 27% would develop CVD.

For every 1% increase in the CVD risk calculated by the Framingham Risk Score, the odds of CVD increased by 4% in the DISH group versus the control group (P = .02).

While there was a significant (P < .003) difference in the Framingham Risk Score between the DISH and control groups in 2006 (28.6% vs. 17.8%), there was no overall statistical difference (P = .2) in the composite CVD outcome (38.8% vs. 25.5%) 10 years later, as calculated by the revised Framingham Risk Score, which included MI, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

“We are dealing with patients who are in their 70s. So, it is expected that this group of patients will be more often affected by cardiovascular disease” than younger individuals, Dr. Mader observed. That said, the study’s findings “confirm the theory that patients with DISH have a high likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease,” he added, acknowledging that it was only the risk for MI that was statistically significantly higher in people with DISH than in the controls.

DISH and coronary artery calcification

“It might be even more interesting to have a different control population that had no osteoarthritis,” Dr. Regan observed.

As the associate director of the COPDGene study, Dr. Regan has access to data collected from a large cohort of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; n = 2,728), around 13% of whom were identified as having DISH in one recent study.

In that study, the presence of DISH versus no DISH was associated with a 37% higher risk for having coronary artery calcification (CAC) – a marker for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Two-thirds of people with DISH had CAC, compared with 46.9% of those without DISH (P < .001). The prevalence of DISH was 8.8% in those without CAC, 12.8% in those with a CAC score of 1-100, 20% in those with a CAC score of 100-400, and 24.7% in those with a CAC score of more than 400, which is associated with a very high risk for coronary artery disease.

Dr. Regan observed that information on heart attacks and strokes were collected within the COPDGene study, so it would be possible to look at cardiovascular risk in their patients with DISH and confirm the findings of Mader and colleagues.

“I think the most important thing is recognizing that there are things going on in the spine that are important to people’s general health,” Dr. Regan said.

Dr. Mader noted: “It makes sense that patients with DISH should be more meticulously followed for at least the traditional risk factors and better treated because they are at a higher risk for these events.”

The study received no financial support. Neither Dr. Mader nor Dr. Regan had any conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Glick K et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02278-w.

More people with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) develop cardiovascular disease (CVD) than is predicted by the Framingham Risk Score, results of an observational study have shown.

Notably, a higher rate of myocardial infarction (MI) was seen in those with DISH than in those without DISH over the 10-year follow-up period (24.4% vs. 4.3%; P = .0055).

“We propose more scrutiny is warranted in evaluating CV risk in these patients, more demanding treatment target goals should be established, and as a result, earlier and more aggressive preventive medical interventions instituted,” corresponding author Reuven Mader, MD, and associates wrote in Arthritis Research & Therapy.

“What Mader’s study is pointing out is that it’s worth the radiologist reporting [DISH],” Elizabeth A. Regan, MD, PhD, from the National Jewish Health Center in Denver, said in an interview.

DISH on a chest x-ray or CT scan should be another “red flag to be even more attentive to cardiovascular risk,” she added, particularly because studies have shown that people with DISH tend to be obese, have metabolic syndrome, or diabetes – all of which independently increase their risk for cardiovascular disease.

An old condition often found by accident

Physicians have known about DISH for many years, Dr. Mader of Ha’Emek Medical Center in Afula, Israel, observed in an interview. Historical evidence suggests it was present more than a thousand years ago, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that it gained scientific interest. Originally coined Forestier’s disease, it was renamed DISH in the late 1960s following the realization that it was not limited to the spine.

“It is a condition which is characterized by new bone formation,” Dr. Mader explained. This new bone formation has some predilection for the entheses – the tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules, that attach to the bone.

“Diagnosis of the disease is based mainly on radiographs, especially of the thoracic spine, and it requires the formation of bridges that connect at least four contiguous vertebra,” he continued.

“The bridges are usually right-sided and usually the intervertebral spaces are spared. Classically there is no involvement of the sacroiliac joints, although there are some changes that might involve the sacroiliac joints but in a different manner than in inflammatory sacroiliitis.”

DISH was originally thought to be a pain syndrome, which has “not played out,” Dr. Regan noted in her interview. While there may be people who experience pain as a result of DISH, most cases are asymptomatic and usually picked up incidentally on a chest x-ray or CT scan.

“It’s something that’s not obvious,” she said. One of the main problems it can cause is stiffness and lack of mobility in the spine and this can lead to quite severe fractures in some cases, such as during a car accident. Hence spinal surgeons and other orthopedic specialists, such as Dr. Regan, have also taken an interest in the condition.

“Apart from the thoracic spine, DISH may also involve the cervical spine; there have been many reports about difficulty in swallowing, breathing, and in the lumbar spine, spinal stenosis and so forth,” Dr. Mader said. The differential diagnosis includes ankylosing spondylitis, although there is some evidence that the two can coexist.

“The diagnosis depends on the alertness of the examining physician,” he added, noting that rheumatologists and other specialists would be “very aware of this condition” and “sensitive to changes that we see when we examine these patients.”

DISH and heightened cardiovascular risk

Previous work by Dr. Mader and associates has shown that people with DISH are more often affected by the metabolic syndrome than are those without DISH. The cross-sectional study had excluded those with preexisting CVD and found that people with DISH had a significantly higher Framingham Risk Score, compared with a control group of people with osteoarthritis and no DISH (P = .004), which in turn meant they had a significantly (P = .007) higher 10-year risk for developing CVD.