User login

Rap music mention of mental health topics more than doubles

Mental health distress is rising but often is undertreated among children and young adults in the United States, wrote Alex Kresovich, MA, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“Mental health risk especially is increasing among young Black/ African American male individuals (YBAAM), who are often disproportionately exposed to environmental, economic, and family stressors linked with depression and anxiety,” they said. Adolescents and young adults, especially YBAAM, make up a large part of the audience for rap music.

In recent years, more rap artists have disclosed mental health issues, and they have included mental health topics such as depression and suicidal thoughts into their music, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 125 songs from the period between 1998 and 2018, then assessed them for references to mental health. The song selections included the top 25 rap songs in 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018, based on the Billboard music charts.

The majority of the songs (123) featured lead artists from North America, and 97 of them were Black/African American males. The average age of the artists was 28 years. “Prominent artists captured in the sample included 50 Cent, Drake, Eminem, Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Lil’Wayne, among others,” they said. The researchers divided mental health issues into four categories: anxiety or anxious thinking; depression or depressive thinking; metaphors (such as struggling with mental stability); and suicide or suicidal ideation.

Mental health references rise

Across the study period, 35 songs (28%) mentioned anxiety, 28 (22%) mentioned depression, 8 (6%) mentioned suicide, and 26 (21%) mentioned a mental health metaphor. The proportion of songs with a mental health reference increased in a significant linear trend across the study period for suicide (0%-12%), depression (16%-32%), and mental health metaphors (8%-44%).

All references to suicide or suicidal ideation were found in songs that were popular between 2013 and 2018, the researchers noted.

“This increase is important, given that rap artists serve as role models to their audience, which extends beyond YBAAM to include U.S. young people across strata, constituting a large group with increased risk of mental health issues and underuse of mental health services,” Mr. Kresovich and associates said.

In addition, the researchers found that stressors related to environmental conditions and love were significantly more likely to co-occur with mental health references (adjusted odds ratios 8.1 and 4.8, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the selection of songs only from the Billboard hot rap songs year-end charts, which “does not fully represent the population of rap music between 1998 and 2018,” the researchers said. In addition, they could not address causation or motivations for the increased mental health references over the study period. “We are also unable to ascertain how U.S. youth interact with this music or are positively or negatively affected by its messages.”

“For example, positively framed references to mental health awareness, treatment, or support may lead to reduced stigma and increased willingness to seek treatment,” Mr. Kresovich and associates wrote. “However, negatively framed references to mental health struggles might lead to negative outcomes, including copycat behavior in which listeners model harmful behavior, such as suicide attempts, if those behaviors are described in lyrics (i.e., the Werther effect),” they added.

Despite these limitations, the results support the need for more research on the impact of rap music as a way to reduce stigma and potentially reduce mental health risk in adolescents and young adults, Mr. Kresovich and associates concluded.

Music may help raise tough topics

The study is important because children and adolescents have more control than ever over the media they consume, Sarah Vinson, MD, founder of the Lorio Psych Group in Atlanta, said in an interview.

“With more and more children with access to their own devices, they spend a great amount of time consuming content, including music,” Dr. Vinson said. “The norms reflected in the lyrics they hear have an impact on their emerging view of themselves, others, and the world.”

The increased recognition of mental health issues by rap musicians as a topic “certainly has the potential to have a positive impact; however, the way that it is discussed can influence [the] nature of that impact,” she explained.

“It is important for people who are dealing with the normal range of human emotions to know that they are not alone. It is even more important for people dealing with suicidality or mental illness to know that,” Dr. Vinson said.

“Validation and sense of connection are human needs, and stigma related to mental illness can be isolating,” she emphasized. “Rappers have a platform and are often people that children and adolescents look up to, for better or for worse.” Through their music, “the rappers are signaling that these topics are worthy of our attention and okay to talk about.”

Unfortunately, many barriers persist for adolescents in need of mental health treatment, said Dr. Vinson. “The children’s mental health workforce, quantitatively, is not enough to meet the current needs,” she said. “Mental health is not reimbursed at the same rate as other kinds of health care, which contributes to healthy systems not prioritizing these services. Additionally, the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic background of those who are mental health providers is not reflective of the larger population, and mental health training insufficiently incorporates the cultural and structural humility needed to help professionals navigate those differences,” she explained.

“Children at increased risk are those who face many of those environmental barriers that the rappers reference in those lyrics. They are likely to have even poorer access because they are disproportionately impacted by residential segregation, transportation challenges, financial barriers, and structural racism in mental health care,” Dr. Vinson added. A take-home message for clinicians is to find out what their patients are listening to. “One way to understand what is on the hearts and minds of children is to ask them what’s in their playlist,” she said.

Additional research is needed to examine “moderating factors for the impact, good or bad, of increased mental health content in hip hop for young listeners’ mental health awareness, symptoms and/or interest in seeking treatment,” Dr. Vinson concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Vinson served as chair for a workshop on mental health and hip-hop at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kresovich A et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5155.

This article was updated on December 21, 2020.

Mental health distress is rising but often is undertreated among children and young adults in the United States, wrote Alex Kresovich, MA, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“Mental health risk especially is increasing among young Black/ African American male individuals (YBAAM), who are often disproportionately exposed to environmental, economic, and family stressors linked with depression and anxiety,” they said. Adolescents and young adults, especially YBAAM, make up a large part of the audience for rap music.

In recent years, more rap artists have disclosed mental health issues, and they have included mental health topics such as depression and suicidal thoughts into their music, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 125 songs from the period between 1998 and 2018, then assessed them for references to mental health. The song selections included the top 25 rap songs in 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018, based on the Billboard music charts.

The majority of the songs (123) featured lead artists from North America, and 97 of them were Black/African American males. The average age of the artists was 28 years. “Prominent artists captured in the sample included 50 Cent, Drake, Eminem, Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Lil’Wayne, among others,” they said. The researchers divided mental health issues into four categories: anxiety or anxious thinking; depression or depressive thinking; metaphors (such as struggling with mental stability); and suicide or suicidal ideation.

Mental health references rise

Across the study period, 35 songs (28%) mentioned anxiety, 28 (22%) mentioned depression, 8 (6%) mentioned suicide, and 26 (21%) mentioned a mental health metaphor. The proportion of songs with a mental health reference increased in a significant linear trend across the study period for suicide (0%-12%), depression (16%-32%), and mental health metaphors (8%-44%).

All references to suicide or suicidal ideation were found in songs that were popular between 2013 and 2018, the researchers noted.

“This increase is important, given that rap artists serve as role models to their audience, which extends beyond YBAAM to include U.S. young people across strata, constituting a large group with increased risk of mental health issues and underuse of mental health services,” Mr. Kresovich and associates said.

In addition, the researchers found that stressors related to environmental conditions and love were significantly more likely to co-occur with mental health references (adjusted odds ratios 8.1 and 4.8, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the selection of songs only from the Billboard hot rap songs year-end charts, which “does not fully represent the population of rap music between 1998 and 2018,” the researchers said. In addition, they could not address causation or motivations for the increased mental health references over the study period. “We are also unable to ascertain how U.S. youth interact with this music or are positively or negatively affected by its messages.”

“For example, positively framed references to mental health awareness, treatment, or support may lead to reduced stigma and increased willingness to seek treatment,” Mr. Kresovich and associates wrote. “However, negatively framed references to mental health struggles might lead to negative outcomes, including copycat behavior in which listeners model harmful behavior, such as suicide attempts, if those behaviors are described in lyrics (i.e., the Werther effect),” they added.

Despite these limitations, the results support the need for more research on the impact of rap music as a way to reduce stigma and potentially reduce mental health risk in adolescents and young adults, Mr. Kresovich and associates concluded.

Music may help raise tough topics

The study is important because children and adolescents have more control than ever over the media they consume, Sarah Vinson, MD, founder of the Lorio Psych Group in Atlanta, said in an interview.

“With more and more children with access to their own devices, they spend a great amount of time consuming content, including music,” Dr. Vinson said. “The norms reflected in the lyrics they hear have an impact on their emerging view of themselves, others, and the world.”

The increased recognition of mental health issues by rap musicians as a topic “certainly has the potential to have a positive impact; however, the way that it is discussed can influence [the] nature of that impact,” she explained.

“It is important for people who are dealing with the normal range of human emotions to know that they are not alone. It is even more important for people dealing with suicidality or mental illness to know that,” Dr. Vinson said.

“Validation and sense of connection are human needs, and stigma related to mental illness can be isolating,” she emphasized. “Rappers have a platform and are often people that children and adolescents look up to, for better or for worse.” Through their music, “the rappers are signaling that these topics are worthy of our attention and okay to talk about.”

Unfortunately, many barriers persist for adolescents in need of mental health treatment, said Dr. Vinson. “The children’s mental health workforce, quantitatively, is not enough to meet the current needs,” she said. “Mental health is not reimbursed at the same rate as other kinds of health care, which contributes to healthy systems not prioritizing these services. Additionally, the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic background of those who are mental health providers is not reflective of the larger population, and mental health training insufficiently incorporates the cultural and structural humility needed to help professionals navigate those differences,” she explained.

“Children at increased risk are those who face many of those environmental barriers that the rappers reference in those lyrics. They are likely to have even poorer access because they are disproportionately impacted by residential segregation, transportation challenges, financial barriers, and structural racism in mental health care,” Dr. Vinson added. A take-home message for clinicians is to find out what their patients are listening to. “One way to understand what is on the hearts and minds of children is to ask them what’s in their playlist,” she said.

Additional research is needed to examine “moderating factors for the impact, good or bad, of increased mental health content in hip hop for young listeners’ mental health awareness, symptoms and/or interest in seeking treatment,” Dr. Vinson concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Vinson served as chair for a workshop on mental health and hip-hop at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kresovich A et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5155.

This article was updated on December 21, 2020.

Mental health distress is rising but often is undertreated among children and young adults in the United States, wrote Alex Kresovich, MA, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“Mental health risk especially is increasing among young Black/ African American male individuals (YBAAM), who are often disproportionately exposed to environmental, economic, and family stressors linked with depression and anxiety,” they said. Adolescents and young adults, especially YBAAM, make up a large part of the audience for rap music.

In recent years, more rap artists have disclosed mental health issues, and they have included mental health topics such as depression and suicidal thoughts into their music, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 125 songs from the period between 1998 and 2018, then assessed them for references to mental health. The song selections included the top 25 rap songs in 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, and 2018, based on the Billboard music charts.

The majority of the songs (123) featured lead artists from North America, and 97 of them were Black/African American males. The average age of the artists was 28 years. “Prominent artists captured in the sample included 50 Cent, Drake, Eminem, Kanye West, Jay-Z, and Lil’Wayne, among others,” they said. The researchers divided mental health issues into four categories: anxiety or anxious thinking; depression or depressive thinking; metaphors (such as struggling with mental stability); and suicide or suicidal ideation.

Mental health references rise

Across the study period, 35 songs (28%) mentioned anxiety, 28 (22%) mentioned depression, 8 (6%) mentioned suicide, and 26 (21%) mentioned a mental health metaphor. The proportion of songs with a mental health reference increased in a significant linear trend across the study period for suicide (0%-12%), depression (16%-32%), and mental health metaphors (8%-44%).

All references to suicide or suicidal ideation were found in songs that were popular between 2013 and 2018, the researchers noted.

“This increase is important, given that rap artists serve as role models to their audience, which extends beyond YBAAM to include U.S. young people across strata, constituting a large group with increased risk of mental health issues and underuse of mental health services,” Mr. Kresovich and associates said.

In addition, the researchers found that stressors related to environmental conditions and love were significantly more likely to co-occur with mental health references (adjusted odds ratios 8.1 and 4.8, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the selection of songs only from the Billboard hot rap songs year-end charts, which “does not fully represent the population of rap music between 1998 and 2018,” the researchers said. In addition, they could not address causation or motivations for the increased mental health references over the study period. “We are also unable to ascertain how U.S. youth interact with this music or are positively or negatively affected by its messages.”

“For example, positively framed references to mental health awareness, treatment, or support may lead to reduced stigma and increased willingness to seek treatment,” Mr. Kresovich and associates wrote. “However, negatively framed references to mental health struggles might lead to negative outcomes, including copycat behavior in which listeners model harmful behavior, such as suicide attempts, if those behaviors are described in lyrics (i.e., the Werther effect),” they added.

Despite these limitations, the results support the need for more research on the impact of rap music as a way to reduce stigma and potentially reduce mental health risk in adolescents and young adults, Mr. Kresovich and associates concluded.

Music may help raise tough topics

The study is important because children and adolescents have more control than ever over the media they consume, Sarah Vinson, MD, founder of the Lorio Psych Group in Atlanta, said in an interview.

“With more and more children with access to their own devices, they spend a great amount of time consuming content, including music,” Dr. Vinson said. “The norms reflected in the lyrics they hear have an impact on their emerging view of themselves, others, and the world.”

The increased recognition of mental health issues by rap musicians as a topic “certainly has the potential to have a positive impact; however, the way that it is discussed can influence [the] nature of that impact,” she explained.

“It is important for people who are dealing with the normal range of human emotions to know that they are not alone. It is even more important for people dealing with suicidality or mental illness to know that,” Dr. Vinson said.

“Validation and sense of connection are human needs, and stigma related to mental illness can be isolating,” she emphasized. “Rappers have a platform and are often people that children and adolescents look up to, for better or for worse.” Through their music, “the rappers are signaling that these topics are worthy of our attention and okay to talk about.”

Unfortunately, many barriers persist for adolescents in need of mental health treatment, said Dr. Vinson. “The children’s mental health workforce, quantitatively, is not enough to meet the current needs,” she said. “Mental health is not reimbursed at the same rate as other kinds of health care, which contributes to healthy systems not prioritizing these services. Additionally, the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic background of those who are mental health providers is not reflective of the larger population, and mental health training insufficiently incorporates the cultural and structural humility needed to help professionals navigate those differences,” she explained.

“Children at increased risk are those who face many of those environmental barriers that the rappers reference in those lyrics. They are likely to have even poorer access because they are disproportionately impacted by residential segregation, transportation challenges, financial barriers, and structural racism in mental health care,” Dr. Vinson added. A take-home message for clinicians is to find out what their patients are listening to. “One way to understand what is on the hearts and minds of children is to ask them what’s in their playlist,” she said.

Additional research is needed to examine “moderating factors for the impact, good or bad, of increased mental health content in hip hop for young listeners’ mental health awareness, symptoms and/or interest in seeking treatment,” Dr. Vinson concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Vinson served as chair for a workshop on mental health and hip-hop at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kresovich A et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Dec 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5155.

This article was updated on December 21, 2020.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Cryoballoon, cryospray found equivalent for eradicating Barret’s esophagus

Cryoballoon and cryospray ablation were equivalent for eradicating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, according to the findings of a single-center retrospective study of 71 ablation-naive patients.

At 18 months, rates of complete eradication of dysplasia were 95.6% in patients who received cryoballoon therapy and 96% in recipients of cryospray, reported Mohammed Alshelleh, MD, of Northwell Health System, a tertiary care system in New Hyde Park, N.Y. Rates of complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia were 84.75% and 80%, respectively. However, selection bias was likely, and a post hoc power calculation suggested that the cryospray group was underpowered by four patients. “Prospective studies are needed to confirm [these] data,” Dr. Alshelleh and associates wrote in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Cryotherapy is common for treating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus when patients do not achieve remission with radiofrequency ablation. For treatment-naive individuals, prospective studies suggest that cryotherapy may be less painful and as effective as radiofrequency ablation, but no studies have directly compared the two commercially available systems: a cryogenic balloon catheter (C2 Cryoballoon, Pentax Medical, Montvale, N.J.) that delivers cryogenic nitrous oxide (–85° C) into an inflated balloon in direct contact with the esophageal mucosa, and a spray cryotherapy system (truFreeze, Steris Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio), which flash-freezes the mucosa to –196° C by delivering liquid nitrogen through a low-pressure catheter that is not directly in contact with the esophagus.

For the study, the investigators retrospectively compared rates of complete eradication of dysplasia, and complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia, among ablation-naive patients at their institution who had received one of these two cryogenic modalities between 2015 and 2019. All patients were treated at least twice, at 3-month intervals, and were followed for least 12 months, or until complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia was confirmed by at least one endoscopic biopsy. In all, 46 patients received cryoballoon therapy and 25 received cryospray. Outcomes between the two modalities showed no significant differences in subgroups stratified by baseline histology, nor were there significant differences in rates of postprocedural stricture (8.7% in the cryoballoon group vs. 12% in the cryospray group). However, the investigators acknowledged that the study was underpowered. Overall, clinicians tended to prefer cryoballoon because it uses prefilled nitrous oxide cartridges, making it unnecessary to fill up a large nitrogen tank or use a “cumbersome decompression tube,” the investigators wrote. “However, in patients with a very large hiatal hernia or if there was a need to treat in a retroflexed position, spray cryotherapy was used given its ease of use over cryoballoon in these scenarios. Finally, cryospray is more amenable to treat larger surface areas of Barrett’s versus the focal cryoballoon that treats focal areas, and thus was the cryotherapy choice for a long segment of Barrett’s.”

The investigators reported receiving no grant support. One investigator disclosed ties to Olympus America, Pentax Medical Research, and Ninepoint Medical.

SOURCE: Alshelleh M et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.07.004.

The role of cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus eradication continues to evolve. Early data on liquid nitrogen (LN) cryospray included patients who failed radiofrequency ablation or had long segment or nodular disease, resulting in eradication rates lower than those for RFA. More recent studies, with cohorts similar to RFA studies, show comparable results with LN cryospray and the newer nitrous oxide cryoballoon. Cryotherapy tends to produce less postprocedure pain compared with RFA, especially when treating longer segments, and this is a common reason for choosing cryotherapy. This study by Alshelleh et al. compared complete eradication rates of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia between cryospray and cryoballoon in a retrospective single-center study. Complete eradication rate of dysplasia was 95%-96% and that of intestinal metaplasia was 80%-85%, comparable with reported results for RFA.

Bruce D. Greenwald, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. He receives research funding from and serves as a consultant for Steris.

The role of cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus eradication continues to evolve. Early data on liquid nitrogen (LN) cryospray included patients who failed radiofrequency ablation or had long segment or nodular disease, resulting in eradication rates lower than those for RFA. More recent studies, with cohorts similar to RFA studies, show comparable results with LN cryospray and the newer nitrous oxide cryoballoon. Cryotherapy tends to produce less postprocedure pain compared with RFA, especially when treating longer segments, and this is a common reason for choosing cryotherapy. This study by Alshelleh et al. compared complete eradication rates of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia between cryospray and cryoballoon in a retrospective single-center study. Complete eradication rate of dysplasia was 95%-96% and that of intestinal metaplasia was 80%-85%, comparable with reported results for RFA.

Bruce D. Greenwald, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. He receives research funding from and serves as a consultant for Steris.

The role of cryotherapy in Barrett’s esophagus eradication continues to evolve. Early data on liquid nitrogen (LN) cryospray included patients who failed radiofrequency ablation or had long segment or nodular disease, resulting in eradication rates lower than those for RFA. More recent studies, with cohorts similar to RFA studies, show comparable results with LN cryospray and the newer nitrous oxide cryoballoon. Cryotherapy tends to produce less postprocedure pain compared with RFA, especially when treating longer segments, and this is a common reason for choosing cryotherapy. This study by Alshelleh et al. compared complete eradication rates of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia between cryospray and cryoballoon in a retrospective single-center study. Complete eradication rate of dysplasia was 95%-96% and that of intestinal metaplasia was 80%-85%, comparable with reported results for RFA.

Bruce D. Greenwald, MD, is a professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. He receives research funding from and serves as a consultant for Steris.

Cryoballoon and cryospray ablation were equivalent for eradicating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, according to the findings of a single-center retrospective study of 71 ablation-naive patients.

At 18 months, rates of complete eradication of dysplasia were 95.6% in patients who received cryoballoon therapy and 96% in recipients of cryospray, reported Mohammed Alshelleh, MD, of Northwell Health System, a tertiary care system in New Hyde Park, N.Y. Rates of complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia were 84.75% and 80%, respectively. However, selection bias was likely, and a post hoc power calculation suggested that the cryospray group was underpowered by four patients. “Prospective studies are needed to confirm [these] data,” Dr. Alshelleh and associates wrote in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Cryotherapy is common for treating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus when patients do not achieve remission with radiofrequency ablation. For treatment-naive individuals, prospective studies suggest that cryotherapy may be less painful and as effective as radiofrequency ablation, but no studies have directly compared the two commercially available systems: a cryogenic balloon catheter (C2 Cryoballoon, Pentax Medical, Montvale, N.J.) that delivers cryogenic nitrous oxide (–85° C) into an inflated balloon in direct contact with the esophageal mucosa, and a spray cryotherapy system (truFreeze, Steris Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio), which flash-freezes the mucosa to –196° C by delivering liquid nitrogen through a low-pressure catheter that is not directly in contact with the esophagus.

For the study, the investigators retrospectively compared rates of complete eradication of dysplasia, and complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia, among ablation-naive patients at their institution who had received one of these two cryogenic modalities between 2015 and 2019. All patients were treated at least twice, at 3-month intervals, and were followed for least 12 months, or until complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia was confirmed by at least one endoscopic biopsy. In all, 46 patients received cryoballoon therapy and 25 received cryospray. Outcomes between the two modalities showed no significant differences in subgroups stratified by baseline histology, nor were there significant differences in rates of postprocedural stricture (8.7% in the cryoballoon group vs. 12% in the cryospray group). However, the investigators acknowledged that the study was underpowered. Overall, clinicians tended to prefer cryoballoon because it uses prefilled nitrous oxide cartridges, making it unnecessary to fill up a large nitrogen tank or use a “cumbersome decompression tube,” the investigators wrote. “However, in patients with a very large hiatal hernia or if there was a need to treat in a retroflexed position, spray cryotherapy was used given its ease of use over cryoballoon in these scenarios. Finally, cryospray is more amenable to treat larger surface areas of Barrett’s versus the focal cryoballoon that treats focal areas, and thus was the cryotherapy choice for a long segment of Barrett’s.”

The investigators reported receiving no grant support. One investigator disclosed ties to Olympus America, Pentax Medical Research, and Ninepoint Medical.

SOURCE: Alshelleh M et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.07.004.

Cryoballoon and cryospray ablation were equivalent for eradicating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, according to the findings of a single-center retrospective study of 71 ablation-naive patients.

At 18 months, rates of complete eradication of dysplasia were 95.6% in patients who received cryoballoon therapy and 96% in recipients of cryospray, reported Mohammed Alshelleh, MD, of Northwell Health System, a tertiary care system in New Hyde Park, N.Y. Rates of complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia were 84.75% and 80%, respectively. However, selection bias was likely, and a post hoc power calculation suggested that the cryospray group was underpowered by four patients. “Prospective studies are needed to confirm [these] data,” Dr. Alshelleh and associates wrote in Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

Cryotherapy is common for treating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus when patients do not achieve remission with radiofrequency ablation. For treatment-naive individuals, prospective studies suggest that cryotherapy may be less painful and as effective as radiofrequency ablation, but no studies have directly compared the two commercially available systems: a cryogenic balloon catheter (C2 Cryoballoon, Pentax Medical, Montvale, N.J.) that delivers cryogenic nitrous oxide (–85° C) into an inflated balloon in direct contact with the esophageal mucosa, and a spray cryotherapy system (truFreeze, Steris Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio), which flash-freezes the mucosa to –196° C by delivering liquid nitrogen through a low-pressure catheter that is not directly in contact with the esophagus.

For the study, the investigators retrospectively compared rates of complete eradication of dysplasia, and complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia, among ablation-naive patients at their institution who had received one of these two cryogenic modalities between 2015 and 2019. All patients were treated at least twice, at 3-month intervals, and were followed for least 12 months, or until complete eradication of intestinal metaplasia was confirmed by at least one endoscopic biopsy. In all, 46 patients received cryoballoon therapy and 25 received cryospray. Outcomes between the two modalities showed no significant differences in subgroups stratified by baseline histology, nor were there significant differences in rates of postprocedural stricture (8.7% in the cryoballoon group vs. 12% in the cryospray group). However, the investigators acknowledged that the study was underpowered. Overall, clinicians tended to prefer cryoballoon because it uses prefilled nitrous oxide cartridges, making it unnecessary to fill up a large nitrogen tank or use a “cumbersome decompression tube,” the investigators wrote. “However, in patients with a very large hiatal hernia or if there was a need to treat in a retroflexed position, spray cryotherapy was used given its ease of use over cryoballoon in these scenarios. Finally, cryospray is more amenable to treat larger surface areas of Barrett’s versus the focal cryoballoon that treats focal areas, and thus was the cryotherapy choice for a long segment of Barrett’s.”

The investigators reported receiving no grant support. One investigator disclosed ties to Olympus America, Pentax Medical Research, and Ninepoint Medical.

SOURCE: Alshelleh M et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Jul 26. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2020.07.004.

FROM TECHNIQUES AND INNOVATIONS IN GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Phase 1 study: Beta-blocker may improve melanoma treatment response

Response rates were high without dose-limiting toxicities in a small phase 1 study that evaluated the addition of propranolol to pembrolizumab in treatment-naive patients with metastatic melanoma.

“To our knowledge, this effort is the,” wrote the two co-first authors, Shipra Gandhi, MD, and Manu Pandey, MBBS, from the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and coauthors.

The need for combinations built on anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy strategies in metastatic melanoma that safely improve outcomes is underscored by the high (59%) grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) rates when an anti-CTLA4 agent (ipilimumab) was added to an anti-PD-1 agent (nivolumab), they noted. In contrast, a TRAE rate of only 17% has been reported with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

The phase 1b study was stimulated by preclinical, retrospective observations of improved overall survival (OS) in cancer patients treated with beta-blockers. These were preceded by murine melanoma studies showing decreased tumor growth and metastasis with the nonselective beta-blocker propranolol. “Propranolol exerts an antitumor effect,” the authors stated, “by favorably modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) by decreasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells and increasing CD8+ T-cell and natural killer cells in the TME.” Other research in a melanoma model in chronically-stressed mice has demonstrated synergy between an anti-PD1 antibody and propranolol.

“We know that stress can have a significant negative effect on health, but the extent to which stress may impact the outcome of cancer therapy is not well understood at all,” Dr. Ghandi said in a statement provided by Roswell Park. “We set out to better understand this relationship and to explore its implications for cancer treatment.”

The investigators recruited nine White adults (median age 65 years) with treatment-naive, histologically confirmed unresectable stage III or IV melanoma and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 to the open-label, single arm, nonrandomized, single-center, dose-finding study. Patients received standard of care intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks and, in three groups, propranolol doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, or 30 mg twice a day until 2 years on study or disease progression or the development of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs). Assessing the safety and efficacy (overall response rate [ORR] within 6 months of starting therapy) of pembrolizumab with the increasing doses of propranolol and selecting the recommended phase 2 dose were the study’s primary objectives.

Objective responses (complete or partial responses) were reported in seven of the nine patients, with partial tumor responses in two patients in the propranolol 10-mg group, two partial responses in the 20-mg group, and three partial responses in the 30-mg group.

While all patients experienced TRAEs, only one was above grade 2. The most commonly reported TRAEs were fatigue, rash and vitiligo, reported in four of the nine patients. Two patients in the 20-mg twice-a-day group discontinued therapy because of TRAEs (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and labyrinthitis). No DLTs were observed at any of the three dose levels, and no deaths occurred on study treatment.

The authors said that propranolol 30 mg twice a day was chosen as the recommended phase 2 dose, because in combination with pembrolizumab, there were no DLTs, and preliminary antitumor efficacy was observed in all three patients. Also, in all three patients, the investigators observed a trend toward higher CD8+T-cell percentage, higher ratios of CD8+T-cell/ Treg and CD8+T-cell/ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells. They underscored, however, that the small size and significant heterogeneity in biomarkers made a statistically sound and meaningful interpretation of biomarkers for deciding the phase 2 dose difficult.

“In repurposing propranolol,” Dr. Pandey said in the Roswell statement, “we’ve gained important insights on how to manage stress in people with cancer – who can face dangerously elevated levels of mental and physical stress related to their diagnosis and treatment.”

In an interview, one of the two senior authors, Elizabeth Repasky, PhD, professor of oncology and immunology at Roswell Park, said, “it’s exciting that an extremely inexpensive drug like propranolol that could be used in every country around the world could have an impact on cancer by blocking stress, especially chronic stress.” Her murine research showing that adding propranolol to immunotherapy or radiotherapy or chemotherapy improved tumor growth control provided rationale for the current study.

“The breakthrough in this study is that it reveals the immune system as the best target to look at, and shows that what stress reduction is doing is improving a patient’s immune response to his or her own tumor,” Dr. Repasky said. “The mind/body connection is so important, but we have not had a handle on how to study it,” she added.

Further research funded by Herd of Hope grants at Roswell will look at tumor effects of propranolol and nonpharmacological reducers of chronic stress such as exercise, meditation, yoga, and Tai Chi, with first studies in breast cancer.

The study was funded by Roswell Park, private, and NIH grants. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gandhi S et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Oct 30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2381

Response rates were high without dose-limiting toxicities in a small phase 1 study that evaluated the addition of propranolol to pembrolizumab in treatment-naive patients with metastatic melanoma.

“To our knowledge, this effort is the,” wrote the two co-first authors, Shipra Gandhi, MD, and Manu Pandey, MBBS, from the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and coauthors.

The need for combinations built on anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy strategies in metastatic melanoma that safely improve outcomes is underscored by the high (59%) grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) rates when an anti-CTLA4 agent (ipilimumab) was added to an anti-PD-1 agent (nivolumab), they noted. In contrast, a TRAE rate of only 17% has been reported with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

The phase 1b study was stimulated by preclinical, retrospective observations of improved overall survival (OS) in cancer patients treated with beta-blockers. These were preceded by murine melanoma studies showing decreased tumor growth and metastasis with the nonselective beta-blocker propranolol. “Propranolol exerts an antitumor effect,” the authors stated, “by favorably modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) by decreasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells and increasing CD8+ T-cell and natural killer cells in the TME.” Other research in a melanoma model in chronically-stressed mice has demonstrated synergy between an anti-PD1 antibody and propranolol.

“We know that stress can have a significant negative effect on health, but the extent to which stress may impact the outcome of cancer therapy is not well understood at all,” Dr. Ghandi said in a statement provided by Roswell Park. “We set out to better understand this relationship and to explore its implications for cancer treatment.”

The investigators recruited nine White adults (median age 65 years) with treatment-naive, histologically confirmed unresectable stage III or IV melanoma and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 to the open-label, single arm, nonrandomized, single-center, dose-finding study. Patients received standard of care intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks and, in three groups, propranolol doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, or 30 mg twice a day until 2 years on study or disease progression or the development of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs). Assessing the safety and efficacy (overall response rate [ORR] within 6 months of starting therapy) of pembrolizumab with the increasing doses of propranolol and selecting the recommended phase 2 dose were the study’s primary objectives.

Objective responses (complete or partial responses) were reported in seven of the nine patients, with partial tumor responses in two patients in the propranolol 10-mg group, two partial responses in the 20-mg group, and three partial responses in the 30-mg group.

While all patients experienced TRAEs, only one was above grade 2. The most commonly reported TRAEs were fatigue, rash and vitiligo, reported in four of the nine patients. Two patients in the 20-mg twice-a-day group discontinued therapy because of TRAEs (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and labyrinthitis). No DLTs were observed at any of the three dose levels, and no deaths occurred on study treatment.

The authors said that propranolol 30 mg twice a day was chosen as the recommended phase 2 dose, because in combination with pembrolizumab, there were no DLTs, and preliminary antitumor efficacy was observed in all three patients. Also, in all three patients, the investigators observed a trend toward higher CD8+T-cell percentage, higher ratios of CD8+T-cell/ Treg and CD8+T-cell/ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells. They underscored, however, that the small size and significant heterogeneity in biomarkers made a statistically sound and meaningful interpretation of biomarkers for deciding the phase 2 dose difficult.

“In repurposing propranolol,” Dr. Pandey said in the Roswell statement, “we’ve gained important insights on how to manage stress in people with cancer – who can face dangerously elevated levels of mental and physical stress related to their diagnosis and treatment.”

In an interview, one of the two senior authors, Elizabeth Repasky, PhD, professor of oncology and immunology at Roswell Park, said, “it’s exciting that an extremely inexpensive drug like propranolol that could be used in every country around the world could have an impact on cancer by blocking stress, especially chronic stress.” Her murine research showing that adding propranolol to immunotherapy or radiotherapy or chemotherapy improved tumor growth control provided rationale for the current study.

“The breakthrough in this study is that it reveals the immune system as the best target to look at, and shows that what stress reduction is doing is improving a patient’s immune response to his or her own tumor,” Dr. Repasky said. “The mind/body connection is so important, but we have not had a handle on how to study it,” she added.

Further research funded by Herd of Hope grants at Roswell will look at tumor effects of propranolol and nonpharmacological reducers of chronic stress such as exercise, meditation, yoga, and Tai Chi, with first studies in breast cancer.

The study was funded by Roswell Park, private, and NIH grants. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gandhi S et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Oct 30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2381

Response rates were high without dose-limiting toxicities in a small phase 1 study that evaluated the addition of propranolol to pembrolizumab in treatment-naive patients with metastatic melanoma.

“To our knowledge, this effort is the,” wrote the two co-first authors, Shipra Gandhi, MD, and Manu Pandey, MBBS, from the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, N.Y., and coauthors.

The need for combinations built on anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy strategies in metastatic melanoma that safely improve outcomes is underscored by the high (59%) grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) rates when an anti-CTLA4 agent (ipilimumab) was added to an anti-PD-1 agent (nivolumab), they noted. In contrast, a TRAE rate of only 17% has been reported with pembrolizumab monotherapy.

The phase 1b study was stimulated by preclinical, retrospective observations of improved overall survival (OS) in cancer patients treated with beta-blockers. These were preceded by murine melanoma studies showing decreased tumor growth and metastasis with the nonselective beta-blocker propranolol. “Propranolol exerts an antitumor effect,” the authors stated, “by favorably modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) by decreasing myeloid-derived suppressor cells and increasing CD8+ T-cell and natural killer cells in the TME.” Other research in a melanoma model in chronically-stressed mice has demonstrated synergy between an anti-PD1 antibody and propranolol.

“We know that stress can have a significant negative effect on health, but the extent to which stress may impact the outcome of cancer therapy is not well understood at all,” Dr. Ghandi said in a statement provided by Roswell Park. “We set out to better understand this relationship and to explore its implications for cancer treatment.”

The investigators recruited nine White adults (median age 65 years) with treatment-naive, histologically confirmed unresectable stage III or IV melanoma and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1 to the open-label, single arm, nonrandomized, single-center, dose-finding study. Patients received standard of care intravenous pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks and, in three groups, propranolol doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, or 30 mg twice a day until 2 years on study or disease progression or the development of dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs). Assessing the safety and efficacy (overall response rate [ORR] within 6 months of starting therapy) of pembrolizumab with the increasing doses of propranolol and selecting the recommended phase 2 dose were the study’s primary objectives.

Objective responses (complete or partial responses) were reported in seven of the nine patients, with partial tumor responses in two patients in the propranolol 10-mg group, two partial responses in the 20-mg group, and three partial responses in the 30-mg group.

While all patients experienced TRAEs, only one was above grade 2. The most commonly reported TRAEs were fatigue, rash and vitiligo, reported in four of the nine patients. Two patients in the 20-mg twice-a-day group discontinued therapy because of TRAEs (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and labyrinthitis). No DLTs were observed at any of the three dose levels, and no deaths occurred on study treatment.

The authors said that propranolol 30 mg twice a day was chosen as the recommended phase 2 dose, because in combination with pembrolizumab, there were no DLTs, and preliminary antitumor efficacy was observed in all three patients. Also, in all three patients, the investigators observed a trend toward higher CD8+T-cell percentage, higher ratios of CD8+T-cell/ Treg and CD8+T-cell/ polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells. They underscored, however, that the small size and significant heterogeneity in biomarkers made a statistically sound and meaningful interpretation of biomarkers for deciding the phase 2 dose difficult.

“In repurposing propranolol,” Dr. Pandey said in the Roswell statement, “we’ve gained important insights on how to manage stress in people with cancer – who can face dangerously elevated levels of mental and physical stress related to their diagnosis and treatment.”

In an interview, one of the two senior authors, Elizabeth Repasky, PhD, professor of oncology and immunology at Roswell Park, said, “it’s exciting that an extremely inexpensive drug like propranolol that could be used in every country around the world could have an impact on cancer by blocking stress, especially chronic stress.” Her murine research showing that adding propranolol to immunotherapy or radiotherapy or chemotherapy improved tumor growth control provided rationale for the current study.

“The breakthrough in this study is that it reveals the immune system as the best target to look at, and shows that what stress reduction is doing is improving a patient’s immune response to his or her own tumor,” Dr. Repasky said. “The mind/body connection is so important, but we have not had a handle on how to study it,” she added.

Further research funded by Herd of Hope grants at Roswell will look at tumor effects of propranolol and nonpharmacological reducers of chronic stress such as exercise, meditation, yoga, and Tai Chi, with first studies in breast cancer.

The study was funded by Roswell Park, private, and NIH grants. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Gandhi S et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Oct 30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2381

FROM CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH

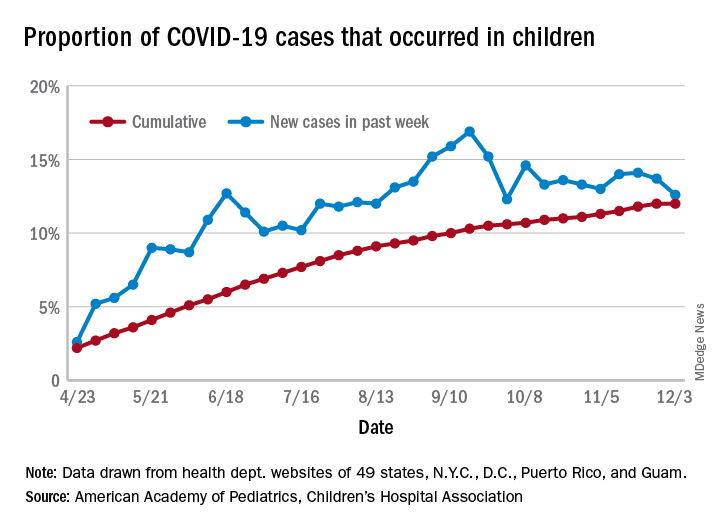

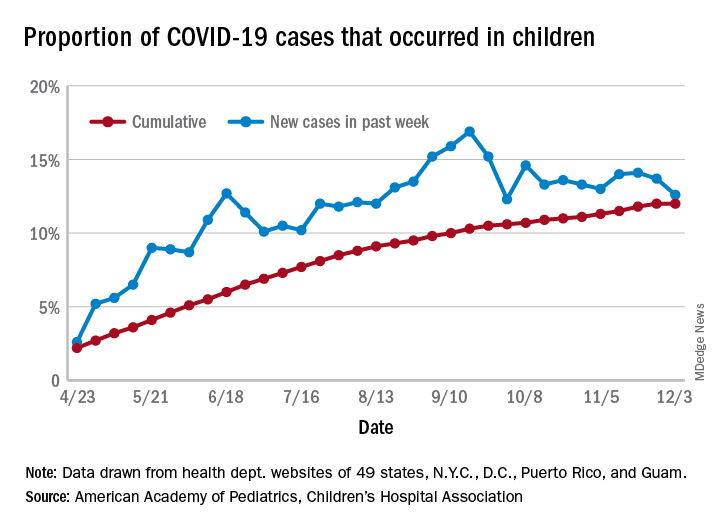

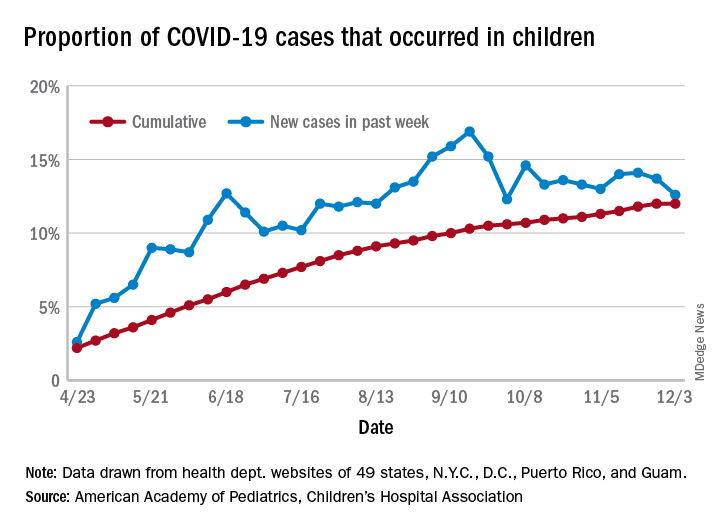

New child COVID-19 cases down in last weekly count

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

A tiny bit of light may have broken though the COVID-19 storm clouds.

The number of new cases in children in the United States did not set a new weekly high for the first time in months and the cumulative proportion of COVID-19 cases occurring in children did not go up for the first time since the pandemic started, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

which is the first time since late September that the weekly total has fallen in the United States, the AAP/CHA data show.

Another measure, the cumulative proportion of infected children among all COVID-19 cases, stayed at 12.0% for the second week in a row, and that is the first time there was no increase since the AAP and CHA started tracking health department websites in 49 states (not New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam in April.

For the week ending Dec. 3, those 123,688 children represented 12.6% of all U.S. COVID-19 cases, marking the second consecutive weekly drop in that figure, which has been as high as 16.9% in the previous 3 months, based on data in the AAP/CHA weekly report.

The total number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is now up to 1.46 million, and the overall rate is 1,941 per 100,000 children. Comparable figures for states show that California has the most cumulative cases at over 139,000 and that North Dakota has the highest rate at over 6,800 per 100,000 children. Vermont, the state with the smallest child population, has the fewest cases (687) and the lowest rate (511 per 100,000), the report said.

The total number of COVID-19–related deaths in children has reached 154 in the 44 jurisdictions (43 states and New York City) reporting such data. That number represents 0.06% of all coronavirus deaths, a proportion that has changed little – ranging from 0.04% to 0.07% – over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said.

‘Practice changing’: Ruxolitinib as second-line in chronic GVHD

When chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) develops as a complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloHSCT), treatment options are limited. New findings show that ruxolitinib (Jakafi) was superior to standard therapy in reducing symptoms of cGVHD in the second-line setting, and the results are potentially practice changing.

The new data, from the REACH3 trial, were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

This trial is “almost certainly a practice changer,” Robert Brodsky, MD, ASH secretary, said during a press preview webinar.

Chronic GVHD occurs in approximately 30%-70% of patients who undergo alloSCT, and “has been really hard to treat,” said Dr. Brodsky, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Steroids are the first-line treatment, but after that, nothing else has shown any improvement and even steroids don’t work that well.”

Of the patients assessed, 50% of those who received ruxolitinib responded to therapy compared with only 25% who received standard therapies.

“This is the first multicenter randomized controlled trial for chronic GVHD that is positive,” said senior study author Robert Zeiser, PhD, of University Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany. “It shows a significant advantage for ruxolitinib. It is likely that this trial will lead to approval for this indication and change the guidelines for the treatment of this disease.”

Ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor first marketed for use in myelofibrosis, is already approved for acute GVHD. The Food and Drug Administration approved that indication last year on the basis of data from two previous trials, REACH 1 and REACH 2. The trials found that ruxolitinib was superior to best available therapy for treating patients with acute GVHD.

Superior to best available therapy

In the current REACH 3 study, Dr. Zeiser and colleagues compared ruxolitinib with best available therapy in 329 patients with moderate-to-severe cGVHD (both steroid dependent and steroid resistant).

All patients had undergone alloSCT and were randomly assigned to ruxolitinib (10 mg twice daily) for six 28-day cycles or investigator-selected best available therapy (BAT), of which there were 10 options. Patients continued receiving their regimen of corticosteroids, and viral prophylaxis and antibiotics were allowed as needed for infection prevention and treatment.

The study permitted crossover: Patients on BAT were allowed to start on ruxolitinib on or after cycle 7 day 1 for those who did not achieve or maintain a response, developed toxicity to BAT, or had a cGVHD flare.

The study met its primary endpoint of overall response rate (ORR), with a clear and substantial improvement among patients taking ruxolitinib (50% vs 26%; odds ratio, 2.99; P < .0001a), Dr. Zeiser noted. The complete response rate was also higher (7% vs. 3%).

Both key secondary endpoints also showed that ruxolitinib was superior to BAT. Failure-free survival was significantly longer in the ruxolitinib group (median not reached vs 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.370; P < .0001). There was also an improvement in symptoms based on changes in the modified Lee symptom score (mLSS; 0 [no symptoms] to 100 [worst symptoms]) at cycle 7 day 1; the results show that the mLSS responder rate was higher in patients on ruxolitinib (24% vs. 11%; odds ratio, 2.62; P = .0011).

A total of 31 patients in the ruxolitinib group died (19%) along with 27 in the BAT group (16%), with the cGVHD as the main cause of death.

Adverse events were comparable in both groups (ruxolitinib 98% [grade ≥ 3, 57%]; BAT, 92% [grade ≥ 3, 58%], with the most common being anemia (29% vs. 13%), hypertension (16% vs. 13%), pyrexia (16% vs. 9%), and ALT increase (15% vs 4%).

More options for patients

“The addition of ruxolitinib is definitely practice changing for this very difficult to treat population,” said James Essell, MD, medical director of the Blood Cancer Center at Mercy Health, Cincinnati, who was not involved in the study.

However, he added, “more options are still required, as evidenced by the continued deaths of patients despite this new option.”

Dr. Essell pointed out that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) is already approved for the treatment of cGVHD. “Ruxolitinib offers another option for treating this group of patients,” he said, and predicted that “it will be used frequently and has a different toxicity profile, ultimately improving the care for patients with cGVHD.”

It is likely that ruxolitinib will be considered earlier in the treatment of cGVHD to avoid the toxicity of chronic steroid use, he added, but price is a consideration. “The cost of ruxolitinib is over 200 times more than prednisone, limiting the adoption front line without a clinical trial.”

Another expert approached for comment was enthusiastic. “The abstract gave good evidence and efficacy with chronic GVHD,” said Ryotaro Nakamura, MD, associate professor of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplantation at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif. He noted that there have been two previous REACH trials which showed a benefit for ruxolitinib in acute GVHD.

What this means is that there is now global evidence that ruxolitinib is better than anything else so far, he said, and this latest trial is just part of the “practice-changing data,” from the three studies. “It is practice changing in that it is providing options now for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Zeiser has disclosed relationships with Incyte, Novartis and Mallinckrodt; other authors disclosed relationships with industry as noted in the abstract. Dr. Essell and Dr. Nakamura have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) develops as a complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloHSCT), treatment options are limited. New findings show that ruxolitinib (Jakafi) was superior to standard therapy in reducing symptoms of cGVHD in the second-line setting, and the results are potentially practice changing.

The new data, from the REACH3 trial, were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

This trial is “almost certainly a practice changer,” Robert Brodsky, MD, ASH secretary, said during a press preview webinar.

Chronic GVHD occurs in approximately 30%-70% of patients who undergo alloSCT, and “has been really hard to treat,” said Dr. Brodsky, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Steroids are the first-line treatment, but after that, nothing else has shown any improvement and even steroids don’t work that well.”

Of the patients assessed, 50% of those who received ruxolitinib responded to therapy compared with only 25% who received standard therapies.

“This is the first multicenter randomized controlled trial for chronic GVHD that is positive,” said senior study author Robert Zeiser, PhD, of University Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany. “It shows a significant advantage for ruxolitinib. It is likely that this trial will lead to approval for this indication and change the guidelines for the treatment of this disease.”

Ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor first marketed for use in myelofibrosis, is already approved for acute GVHD. The Food and Drug Administration approved that indication last year on the basis of data from two previous trials, REACH 1 and REACH 2. The trials found that ruxolitinib was superior to best available therapy for treating patients with acute GVHD.

Superior to best available therapy

In the current REACH 3 study, Dr. Zeiser and colleagues compared ruxolitinib with best available therapy in 329 patients with moderate-to-severe cGVHD (both steroid dependent and steroid resistant).

All patients had undergone alloSCT and were randomly assigned to ruxolitinib (10 mg twice daily) for six 28-day cycles or investigator-selected best available therapy (BAT), of which there were 10 options. Patients continued receiving their regimen of corticosteroids, and viral prophylaxis and antibiotics were allowed as needed for infection prevention and treatment.

The study permitted crossover: Patients on BAT were allowed to start on ruxolitinib on or after cycle 7 day 1 for those who did not achieve or maintain a response, developed toxicity to BAT, or had a cGVHD flare.

The study met its primary endpoint of overall response rate (ORR), with a clear and substantial improvement among patients taking ruxolitinib (50% vs 26%; odds ratio, 2.99; P < .0001a), Dr. Zeiser noted. The complete response rate was also higher (7% vs. 3%).

Both key secondary endpoints also showed that ruxolitinib was superior to BAT. Failure-free survival was significantly longer in the ruxolitinib group (median not reached vs 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.370; P < .0001). There was also an improvement in symptoms based on changes in the modified Lee symptom score (mLSS; 0 [no symptoms] to 100 [worst symptoms]) at cycle 7 day 1; the results show that the mLSS responder rate was higher in patients on ruxolitinib (24% vs. 11%; odds ratio, 2.62; P = .0011).

A total of 31 patients in the ruxolitinib group died (19%) along with 27 in the BAT group (16%), with the cGVHD as the main cause of death.

Adverse events were comparable in both groups (ruxolitinib 98% [grade ≥ 3, 57%]; BAT, 92% [grade ≥ 3, 58%], with the most common being anemia (29% vs. 13%), hypertension (16% vs. 13%), pyrexia (16% vs. 9%), and ALT increase (15% vs 4%).

More options for patients

“The addition of ruxolitinib is definitely practice changing for this very difficult to treat population,” said James Essell, MD, medical director of the Blood Cancer Center at Mercy Health, Cincinnati, who was not involved in the study.

However, he added, “more options are still required, as evidenced by the continued deaths of patients despite this new option.”

Dr. Essell pointed out that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) is already approved for the treatment of cGVHD. “Ruxolitinib offers another option for treating this group of patients,” he said, and predicted that “it will be used frequently and has a different toxicity profile, ultimately improving the care for patients with cGVHD.”

It is likely that ruxolitinib will be considered earlier in the treatment of cGVHD to avoid the toxicity of chronic steroid use, he added, but price is a consideration. “The cost of ruxolitinib is over 200 times more than prednisone, limiting the adoption front line without a clinical trial.”

Another expert approached for comment was enthusiastic. “The abstract gave good evidence and efficacy with chronic GVHD,” said Ryotaro Nakamura, MD, associate professor of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplantation at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif. He noted that there have been two previous REACH trials which showed a benefit for ruxolitinib in acute GVHD.

What this means is that there is now global evidence that ruxolitinib is better than anything else so far, he said, and this latest trial is just part of the “practice-changing data,” from the three studies. “It is practice changing in that it is providing options now for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Zeiser has disclosed relationships with Incyte, Novartis and Mallinckrodt; other authors disclosed relationships with industry as noted in the abstract. Dr. Essell and Dr. Nakamura have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) develops as a complication of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloHSCT), treatment options are limited. New findings show that ruxolitinib (Jakafi) was superior to standard therapy in reducing symptoms of cGVHD in the second-line setting, and the results are potentially practice changing.

The new data, from the REACH3 trial, were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

This trial is “almost certainly a practice changer,” Robert Brodsky, MD, ASH secretary, said during a press preview webinar.

Chronic GVHD occurs in approximately 30%-70% of patients who undergo alloSCT, and “has been really hard to treat,” said Dr. Brodsky, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “Steroids are the first-line treatment, but after that, nothing else has shown any improvement and even steroids don’t work that well.”

Of the patients assessed, 50% of those who received ruxolitinib responded to therapy compared with only 25% who received standard therapies.

“This is the first multicenter randomized controlled trial for chronic GVHD that is positive,” said senior study author Robert Zeiser, PhD, of University Medical Center, Freiburg, Germany. “It shows a significant advantage for ruxolitinib. It is likely that this trial will lead to approval for this indication and change the guidelines for the treatment of this disease.”

Ruxolitinib, a JAK inhibitor first marketed for use in myelofibrosis, is already approved for acute GVHD. The Food and Drug Administration approved that indication last year on the basis of data from two previous trials, REACH 1 and REACH 2. The trials found that ruxolitinib was superior to best available therapy for treating patients with acute GVHD.

Superior to best available therapy

In the current REACH 3 study, Dr. Zeiser and colleagues compared ruxolitinib with best available therapy in 329 patients with moderate-to-severe cGVHD (both steroid dependent and steroid resistant).

All patients had undergone alloSCT and were randomly assigned to ruxolitinib (10 mg twice daily) for six 28-day cycles or investigator-selected best available therapy (BAT), of which there were 10 options. Patients continued receiving their regimen of corticosteroids, and viral prophylaxis and antibiotics were allowed as needed for infection prevention and treatment.

The study permitted crossover: Patients on BAT were allowed to start on ruxolitinib on or after cycle 7 day 1 for those who did not achieve or maintain a response, developed toxicity to BAT, or had a cGVHD flare.

The study met its primary endpoint of overall response rate (ORR), with a clear and substantial improvement among patients taking ruxolitinib (50% vs 26%; odds ratio, 2.99; P < .0001a), Dr. Zeiser noted. The complete response rate was also higher (7% vs. 3%).

Both key secondary endpoints also showed that ruxolitinib was superior to BAT. Failure-free survival was significantly longer in the ruxolitinib group (median not reached vs 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.370; P < .0001). There was also an improvement in symptoms based on changes in the modified Lee symptom score (mLSS; 0 [no symptoms] to 100 [worst symptoms]) at cycle 7 day 1; the results show that the mLSS responder rate was higher in patients on ruxolitinib (24% vs. 11%; odds ratio, 2.62; P = .0011).

A total of 31 patients in the ruxolitinib group died (19%) along with 27 in the BAT group (16%), with the cGVHD as the main cause of death.

Adverse events were comparable in both groups (ruxolitinib 98% [grade ≥ 3, 57%]; BAT, 92% [grade ≥ 3, 58%], with the most common being anemia (29% vs. 13%), hypertension (16% vs. 13%), pyrexia (16% vs. 9%), and ALT increase (15% vs 4%).

More options for patients

“The addition of ruxolitinib is definitely practice changing for this very difficult to treat population,” said James Essell, MD, medical director of the Blood Cancer Center at Mercy Health, Cincinnati, who was not involved in the study.

However, he added, “more options are still required, as evidenced by the continued deaths of patients despite this new option.”

Dr. Essell pointed out that ibrutinib (Imbruvica) is already approved for the treatment of cGVHD. “Ruxolitinib offers another option for treating this group of patients,” he said, and predicted that “it will be used frequently and has a different toxicity profile, ultimately improving the care for patients with cGVHD.”

It is likely that ruxolitinib will be considered earlier in the treatment of cGVHD to avoid the toxicity of chronic steroid use, he added, but price is a consideration. “The cost of ruxolitinib is over 200 times more than prednisone, limiting the adoption front line without a clinical trial.”

Another expert approached for comment was enthusiastic. “The abstract gave good evidence and efficacy with chronic GVHD,” said Ryotaro Nakamura, MD, associate professor of hematology & hematopoietic cell transplantation at City of Hope, Duarte, Calif. He noted that there have been two previous REACH trials which showed a benefit for ruxolitinib in acute GVHD.

What this means is that there is now global evidence that ruxolitinib is better than anything else so far, he said, and this latest trial is just part of the “practice-changing data,” from the three studies. “It is practice changing in that it is providing options now for these patients,” he said.

Dr. Zeiser has disclosed relationships with Incyte, Novartis and Mallinckrodt; other authors disclosed relationships with industry as noted in the abstract. Dr. Essell and Dr. Nakamura have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Air pollution linked to brain amyloid pathology

Higher levels of air pollution were associated with an increased risk for amyloid-beta pathology in a new study of older adults with cognitive impairment. “Many studies have now found a link between air pollution and clinical outcomes of dementia or cognitive decline,” said lead author Leonardo Iaccarino, PhD, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco. “But this study is now showing a clear link between air pollution and a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease: It shows a relationship between bad air quality and pathology in the brain.

“We believe that exposure to air pollution should be considered as one factor in the lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease,” he added. “We believe it is a significant determinant. Our results suggest that, if we can reduce occupational and residential exposure to air pollution, then this could help reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The study was published online Nov. 30 in JAMA Neurology.

A modifiable risk factor

Dr. Iaccarino explained that it is well known that air pollution is linked to poor health outcomes. “As well as cardiovascular and respiratory disease, there is also growing interest in the relationship between air pollution and brain health,” he said. “The link is becoming more and more convincing, with evidence from laboratory, animal, and human studies suggesting that individuals exposed to poor air quality have an increased risk of cognitive decline and dementia.”

In addition, this year, the Lancet Commission included air pollution in its updated list of modifiable risk factors for dementia.

For the current study, the researchers analyzed data from the Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) Study, which included more than 18,000 U.S. participants with cognitive impairment who received an amyloid positron-emission tomography scan between 2016 and 2018.

The investigators used data from the IDEAS study to assess the relationship between the air quality at the place of residence of each patient and the likelihood of a positive amyloid PET result. Public records from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were used to estimate air quality in individual ZIP-code areas during two periods – 2002-2003 (approximately 14 years before the amyloid PET scan) and 2015-2016 (approximately 1 year before the amyloid PET scan).

Results showed that those living in an area with increased air pollution, as determined using concentrations of predicted fine particulate matter (PM2.5), had a higher probability of a positive amyloid PET scan. This association was dose dependent and statistically significant after adjusting for demographic, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors as well as medical comorbidities. The association was seen in both periods; the adjusted odds ratio was 1.10 in 2002-2003 and 1.15 in 2015-2016.

“This shows about a 10% increased probability of a positive amyloid test for individuals living in the worst polluted areas, compared with those in the least polluted areas,” Dr. Iaccarino explained.

Every unit increase in PM2.5 in 2002-2003 was associated with an increased probability of positive amyloid findings on PET of 0.5%. Every unit increase in PM2.5 in for the 2015-2016 period was associated with an increased probability of positive amyloid findings on PET of 0.8%.

“This was a very large cohort study, and we adjusted for multiple other factors, so these are pretty robust findings,” Dr. Iaccarino said.

Exposure to higher ozone concentrations was not associated with amyloid positivity on PET scans in either time window.

“These findings suggest that brain amyloid-beta accumulation could be one of the biological pathways in the increased incidence of dementia and cognitive decline associated with exposure to air pollution,” the researchers stated.

A public health concern