User login

Burnt Out ? The Phenomenon of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in End-Stage Renal Disease

In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice with a hemoglobin A1c target of 6 to 8%, using fructosamine levels or other measures for better assessment of glycemic control.

More than 34 million adults in the US have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a chronic progressive disease identified by worsening hyperglycemia and micro- and macrovascular complications.1 Consequently, 12.2% of the US adult population is currently at risk for macrovascular diseases, such as stroke and coronary artery disease (CAD) and microvascular diseases, such as neuropathy and diabetic nephropathy.1

T2DM is the most common comorbid risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). As of 2017, about 750,000 Americans have CKD stage 5 requiring dialysis, and 50% of these patients have preexisting diabetic nephropathy.2 Rates of mortality and morbidity are observed to be higher in patients with both CKD and T2DM compared with patients with CKD without T2DM.2 Previous clinical trials, including the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study of 1998, have proven that optimal glycemic control decreases the risk of complications of T2DM (ie, nephropathy) in the general population.3 Conversely, tight glycemic control that targets hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 7%, in patients with T2DM with ESRD has not shown the same benefits and may lead to worse outcomes. It is postulated that this may be due to the increased incidence of hypoglycemia in this patient population.4

Dialysis has varying effects on patients both with and without T2DM. While patients with ESRD without T2DM have the potential to develop impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM, about 33% of patients with T2DM on dialysis actually have HbA1c < 6%.5 In these patients, glycemic control improves spontaneously as their disease progresses, leading to a decrease or cessation of insulin or other antidiabetic medications. This phenomenon, known as burnt-out diabetes, is characterized by (1) alterations in glucose homeostasis and normoglycemia without antidiabetic treatment; (2) HbA1c levels < 6% despite having established T2DM; (3) decline in insulin requirements or cessation of insulin altogether; and (4) spontaneous hypoglycemia.

There is a misconception that burnt-out diabetes is a favorable condition due to the alteration of the natural course of T2DM. Although this may be true, patients with this condition are prone to develop hypoglycemic episodes and may be linked to poor survival outcomes due to low HbA1c.6,7

Since Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues presented a 2009 case study, there has been a lack of research regarding this unique condition.8 The purpose of this case study is to shed further light on burnt-out diabetes and present a patient case pertaining to the challenges of glycemic control in ESRD.

Case Presentation

Mr. A is a 49-year-old Hispanic male veteran with a history of ESRD on hemodialysis (HD) for 6 years, anemia of CKD, and T2DM for 22 years. The patient also has an extensive cardiovascular disease history, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CAD status post-4-vessel coronary artery bypass graft in December 2014. The patient receives in-home HD Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and is on the wait list for kidney transplantation. The patient’s T2DM is managed by a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) at the

Mr. A’s antidiabetic regimen is 45 units of subcutaneous insulin glargine every morning; insulin aspart sliding scale (about 15-27 units) subcutaneous 3 times daily with meals; and saxagliptin 2.5 mg by mouth once daily.

At a follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A stated, “I feel fine except for the occasional low blood sugar episode.” The patient’s most recent HbA1c was 6.1%, and he reported medication adherence and no signs or symptoms of hyperglycemia (ie, polydipsia, polyphagia, nocturia, visual disturbances). Mr. A reported no use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. He walks 1 mile every other day and participates in self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) about 2 to 3 times daily (Table 1).

Although Mr. A’s most recent HbA1c was well controlled, his estimated fasting blood glucose at the same laboratory draw was 224 mg/dL. His SMBG readings in the past month also were elevated with higher readings in the evening. Mr. A attributed the elevated readings to dietary excursions and a high carbohydrate intake. At this visit, the CPS increased his insulin glargine dose to 50 units subcutaneous every morning and educated him on lifestyle modifications. Follow-up with the CPS was scheduled for 2 months from the day of the visit.

Analysis

Few articles on potential contributors to burnt-out diabetes have been published.6,7 These articles discuss decreased renal and hepatic clearance of insulin (which increases its half-life) hypoglycemia during HD, and low HbA1c due to preexisting anemia. Inappropriately low HbA1c levels may be secondary to, but not limited to, hemolysis, recent blood transfusion, acute blood loss, and medications, such as erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs).9 The conditions that affect red blood cell turnover are common in patients with advanced CKD and may result in discrepancies in HbA1c levels.

Glycated hemoglobin is a series of minor hemoglobin components formed by the adduction of various carbohydrate molecules to hemoglobin. HbA1c is the largest fraction formed and the most consistent index of the concentration of glucose in the blood.10 Hence, HbA1c is the traditional indicator of overall glycemic control. The current HbA1c goals recommended by the American Diabetes Association are derived from landmark trials conducted with patients in the general adult diabetic non-CKD population. However, hemoglobin measurements can be confounded by conditions present in ESRD and tend to underestimate glucose measurements in patients with T2DM on HD. Despite this, HbA1c is still regarded as a reasonable measure of glycemic control even in patients with ESRD; however, alternative markers of glycemia may be preferable.11

Although HbA1c is the gold standard, there are other laboratory measures of average glycemic control available. Fructosamine is a ketoamine formed when glucose binds to serum proteins. When these proteins are exposed to high concentrations of glucose, they experience increased glycation. Fructosamine assays measure the total glycated serum proteins, of which albumin accounts for about 90%.11 Because the half-life of serum proteins is about 20 days, fructosamine levels can reflect glycemic control over a 2- to 3-week period. This is advantageous in conditions that affect the average age of red blood cells, in pregnancy where frequent monitoring and measures of short-term glucose control are especially important, and in the evaluation of a medication adjustment in the management of T2DM. However, this test is not without its limitations. It is less reliable in settings of decreased protein levels (eg, liver disease), there is a lack of availability in routine practice, and reference levels have not been established.11

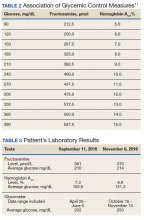

Fructosamine has been shown to be strongly associated with mean blood glucose and HbA1c (Table 2). In 2010, Mittman and colleagues published a study that compared HbA1c with fructosamine and their correlation to glycemic control and morbidity, defined as rates of hospitalization and infection.12 The study included 100 patients with T2DM on HD with a mean age of 63 years, 54% were women, mean HbA1c of 7.2%, and mean dialysis duration of 3 years. Average follow-up was 3 years. At the end of follow-up, Mittman and colleagues found that HbA1c and fructosamine were highly correlated and associated with serum glucose (P < .01). However, fructosamine was found to be more highly correlated with mean glucose levels when those levels were below 150 mg/dL (P = .01). A higher fructosamine level, not HbA1c was a more significant predictor of hospitalization (P = .007) and infection (P = .001). Mittman and colleagues presented evidence for the use of fructosamine over HbA1c in patients with T2DM on HD.12

Hypoglycemic Episodes

At the 2-month follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A reported having 5 hypoglycemic episodes in the past 30 days. He also stated he would forget to take his insulin aspart dose before dinner about 3 to 4 times a week but would take it 30 to 60 minutes after the meal. Mr. A did not bring his glucometer or SMBG readings to the visit, but he indicated that his blood glucose levels continued to fluctuate and were elevated when consuming carbohydrates.

Laboratory tests 1 month prior to the 2-month follow-up visit showed HbA1c of 7.3%, which had increased from his previous level of 6.1%. He was counseled on the proper administration of insulin aspart and lifestyle modifications. A fructosamine level was ordered at this visit to further assess his glycemic control. A follow-up appointment and laboratory workup (fructosamine and HbA1c) were scheduled for 2 months from the visit (Table 3).

Mr. A was educated on the unreliability of his HbA1c levels secondary to his condition of ESRD on HD. He was counseled on the purpose of fructosamine and how it may be a better predictor of his glycemic control and morbidity. Mr. A continued to be followed closely by the primary care CPS for T2DM management.

Discussion

Management of T2DM in patients with ESRD presents challenges for clinicians in determining HbA1c goals and selecting appropriate medication options. The 2012 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) diabetes guideline does not recommend treatment for patients with substantially reduced kidney function to a target HbA1c < 7% due to risk of hypoglycemia.13 Although a target HbA1c > 7% is suggested for these patients, little is known about appropriate glycemic control in these patients as there is a paucity of prospective, randomized clinical trials that include patients with advanced CKD.13

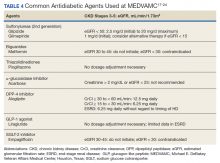

Moreover, many oral antidiabetic medications and their metabolites are cleared by the kidneys and, therefore, pose with potential harm for patients with CKD. Because of this, insulin is the medication of choice for patients with ESRD.7 Although insulin requirements may diminish with worsening kidney function, insulin provides the safest method of glycemic control. Insulin dosing can be individualized according to a patient’s renal status as there is no uniformity in renal dose adjustments. There are some noninsulin antidiabetic agents that can be used in ESRD, but use of these agents requires close monitoring and evaluation of the medication’s pharmacokinetics (Table 4). Overall, medication management can be a difficult task for patients with T2DM and ESRD, but antidiabetic regimens may be reduced or discontinued altogether in burnt-out diabetes.

One of 3 patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis has burnt-out diabetes, defined as a phenomenon in which glucose homeostasis is altered to cause normoglycemia, spontaneous hypoglycemia, and decreased insulin requirements in established patients with T2DM.5 Although Mr. A had a normal-to-low HbA1c, he did not meet these criteria. Due to his elevated SMBG readings, he did not have normoglycemia and did require an increase in his basal insulin dose. Therefore, our patient did not have burnt-out diabetes.

Mr. A represents the relevant issue of inappropriately and unreliably low HbA1c levels due to various factors in ESRD. Our patient did not receive a blood transfusion in the past 2 years and was not on ESA therapy; nevertheless, Mr. A was a patient with ESRD on HD with a diagnosis of anemia. These diagnoses are confounders for low HbA1c values. When fructosamine levels were drawn for Mr. A on September 11, 2018 and November 6, 2018, they correlated well with his serum glucose and SMBG readings. This indicated to the CPS that the patient’s glycemic control was poor despite a promising HbA1c level.

This patient’s case and supporting evidence suggests that other measures of glycemic control (eg, fructosamine) can be used to supplement HbA1c, serum glucose, and glucometer readings to provide an accurate assessment of glycemic control in T2DM. Fructosamine also can assist HbA1c with predicting morbidity and potentially mortality, which are of great importance in this patient population.

Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues conducted a study of 23,618 patients with T2DM on dialysis to observe mortality in association with HbA1c.5 This analysis showed that patients with HbA1c levels < 5% or > 8% had a higher risk of mortality; higher values of HbA1c (> 10%) were associated with increased death risk vs all other values. In the unadjusted analysis, HbA1c levels between 6 and 8% had the lowest death risk (hazard ratios [HR] 0.8 - 0.9, 95% CI) compared with those of higher and lower HbA1c ranges.5 In nonanemic patients, HbA1c > 6% was associated with increased death risk, whereas anemic patients did not show this trend.

Other studies made similar observations. In 2001, Morioka and colleagues published an observational study of 150 patients with DM on intermittent hemodialysis. The study analyzed survival and HbA1c levels at 1, 3, and 5 years. The study found that at 1, 3, and 5 years, patients with HbA1c < 7.5% had better survival than did patients with HbA1c > 7.5% (3.6 years vs 2.0 years, P = .008). Morioka and colleagues also found that there was a 13% increase in death per 1% increase in HbA1c.14 Oomichi and colleagues conducted an observational study of 114 patients with T2DM and ESRD on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with fair control (HbA1c 6.5 - 8%) and good control (HbA1c < 6.5%) were compared with patients with poor control (HbA1c > 8%); it was found that the poor control group had nearly triple the mortality when compared with the good and fair control groups (HR = 2.89, P = .01).15 Park and colleagues also saw a similar observation in a study of 1,239 patients with ESRD and DM; 70% of these patients were on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with poor control (HbA1c ≥ 8%) had worse survival outcomes than those with HbA1c < 8% (HR 2.2, P < .001).16

Our patient case forced us to ask the question, “What should our patient’s HbA1c goals be?” In the study by Oomichi and colleagues, a HbA1c level of 8% has usefulness as a “signpost for management of glycemic control.”15 All patients’ goals should be individualized based on various factors (eg, age, comorbidities), but based on the survival studies above, a HbA1c goal range of 6 to 8% may be optimal.

Conclusions

Patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis may have higher morbidity and mortality rates than the rates of those without T2DM. It has been shown in various studies that very low HbA1c (< 5%) and high HbA1c (> 8%) are associated with poor survival. Some patients with T2DM on dialysis may experience burnt-out diabetes in which they may have normoglycemia and a HbA1c below goal; despite these facts, this condition is not positive and can be linked to bad outcomes. In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice, and we recommend a HbA1c target of 6 to 8%. In this patient population, consider using fructosamine levels or other measures of glycemic control to supplement HbA1c and glucose values to provide a better assessment of glycemic control, morbidity, and mortality. Larger clinical trials are needed to assist in answering questions regarding mortality and optimal HbA1c targets in burnt-out diabetes.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2020.

2. Saran R, Robinson B, et al. US renal data system 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of klidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Jan;75(1 suppl 1):A6-A7. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Nov 5.

3. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):854-865.

4. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545-2559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

5. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Regidor DL, et al. A1c and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1049-10.55. doi:10.2337/dc06-2127

6. Park J, Lertdumrongluk P, Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Glycemic control in diabetic dialysis patients and the burnt-out diabetes phenomenon. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(4):432-439. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0286-3

7. Rhee CM, Leung AM, Kovesdy CP, Lynch KE, Brent GA, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Updates on the management of diabetes in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2014;27(2):135-145. doi:10.1111/sdi.12198

8. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Derose SF, Nicholas S, Benner D, Sharma K, Kovesdy CP. Burnt-out diabetes: impact of chronic kidney disease progression on the natural course of diabetes mellitus. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19(1):33-37. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2008.11.012

9. Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Drugs affecting HbA1c levels. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):528-531. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.98004

10. Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(6):1572-1583. doi:10.1177/193229681100500634

11. Wright LAC, Hirsch IB. The challenge of the use of glycemic biomarkers in diabetes: reflecting on hemoglobin A1c, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, and the glycated proteins fructosamine and glycated albumin. Diabetes Spectr. 2012;25(3):141-148. doi:10.2337/diaspect.25.3.141

12. Mittman N, Desiraju B, Fazil I, et al. Serum fructosamine versus glycosylated hemoglobin as an index of glycemic control, hospitalization, and infection in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78 (suppl 117):S41-S45. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.193

13. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850-886. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005

14. Morioka T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Glycemic control is a predictor of survival for diabetic patients on hemodialysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):909-913. doi.10.2337/diacare.24.5.909

15. Oomichi T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Impact of glycemic control on survival of diabetic patients on chronic regular hemodialysis: a 7-year observational study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1496-1500. doi:10.2337/dc05-1887

16. Park JI, Bae E, Kim YL, et al. Glycemic control and mortality in diabetic patients undergoing dialysis focusing on the effects of age and dialysis type: a prospective cohort study in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136085. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136085

17. Glucotrol tablets [

18. Amaryl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; December 2018.

19. Glucophage [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; May 2018.

20. Actos [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; December 2017.

21. Precose [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; March 2015.

22. Nesina [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; June 2019.

23. Victoza [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc; June 2019.

24. Jardiance [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc; October 2018.

In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice with a hemoglobin A1c target of 6 to 8%, using fructosamine levels or other measures for better assessment of glycemic control.

In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice with a hemoglobin A1c target of 6 to 8%, using fructosamine levels or other measures for better assessment of glycemic control.

More than 34 million adults in the US have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a chronic progressive disease identified by worsening hyperglycemia and micro- and macrovascular complications.1 Consequently, 12.2% of the US adult population is currently at risk for macrovascular diseases, such as stroke and coronary artery disease (CAD) and microvascular diseases, such as neuropathy and diabetic nephropathy.1

T2DM is the most common comorbid risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). As of 2017, about 750,000 Americans have CKD stage 5 requiring dialysis, and 50% of these patients have preexisting diabetic nephropathy.2 Rates of mortality and morbidity are observed to be higher in patients with both CKD and T2DM compared with patients with CKD without T2DM.2 Previous clinical trials, including the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study of 1998, have proven that optimal glycemic control decreases the risk of complications of T2DM (ie, nephropathy) in the general population.3 Conversely, tight glycemic control that targets hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 7%, in patients with T2DM with ESRD has not shown the same benefits and may lead to worse outcomes. It is postulated that this may be due to the increased incidence of hypoglycemia in this patient population.4

Dialysis has varying effects on patients both with and without T2DM. While patients with ESRD without T2DM have the potential to develop impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM, about 33% of patients with T2DM on dialysis actually have HbA1c < 6%.5 In these patients, glycemic control improves spontaneously as their disease progresses, leading to a decrease or cessation of insulin or other antidiabetic medications. This phenomenon, known as burnt-out diabetes, is characterized by (1) alterations in glucose homeostasis and normoglycemia without antidiabetic treatment; (2) HbA1c levels < 6% despite having established T2DM; (3) decline in insulin requirements or cessation of insulin altogether; and (4) spontaneous hypoglycemia.

There is a misconception that burnt-out diabetes is a favorable condition due to the alteration of the natural course of T2DM. Although this may be true, patients with this condition are prone to develop hypoglycemic episodes and may be linked to poor survival outcomes due to low HbA1c.6,7

Since Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues presented a 2009 case study, there has been a lack of research regarding this unique condition.8 The purpose of this case study is to shed further light on burnt-out diabetes and present a patient case pertaining to the challenges of glycemic control in ESRD.

Case Presentation

Mr. A is a 49-year-old Hispanic male veteran with a history of ESRD on hemodialysis (HD) for 6 years, anemia of CKD, and T2DM for 22 years. The patient also has an extensive cardiovascular disease history, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CAD status post-4-vessel coronary artery bypass graft in December 2014. The patient receives in-home HD Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and is on the wait list for kidney transplantation. The patient’s T2DM is managed by a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) at the

Mr. A’s antidiabetic regimen is 45 units of subcutaneous insulin glargine every morning; insulin aspart sliding scale (about 15-27 units) subcutaneous 3 times daily with meals; and saxagliptin 2.5 mg by mouth once daily.

At a follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A stated, “I feel fine except for the occasional low blood sugar episode.” The patient’s most recent HbA1c was 6.1%, and he reported medication adherence and no signs or symptoms of hyperglycemia (ie, polydipsia, polyphagia, nocturia, visual disturbances). Mr. A reported no use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. He walks 1 mile every other day and participates in self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) about 2 to 3 times daily (Table 1).

Although Mr. A’s most recent HbA1c was well controlled, his estimated fasting blood glucose at the same laboratory draw was 224 mg/dL. His SMBG readings in the past month also were elevated with higher readings in the evening. Mr. A attributed the elevated readings to dietary excursions and a high carbohydrate intake. At this visit, the CPS increased his insulin glargine dose to 50 units subcutaneous every morning and educated him on lifestyle modifications. Follow-up with the CPS was scheduled for 2 months from the day of the visit.

Analysis

Few articles on potential contributors to burnt-out diabetes have been published.6,7 These articles discuss decreased renal and hepatic clearance of insulin (which increases its half-life) hypoglycemia during HD, and low HbA1c due to preexisting anemia. Inappropriately low HbA1c levels may be secondary to, but not limited to, hemolysis, recent blood transfusion, acute blood loss, and medications, such as erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs).9 The conditions that affect red blood cell turnover are common in patients with advanced CKD and may result in discrepancies in HbA1c levels.

Glycated hemoglobin is a series of minor hemoglobin components formed by the adduction of various carbohydrate molecules to hemoglobin. HbA1c is the largest fraction formed and the most consistent index of the concentration of glucose in the blood.10 Hence, HbA1c is the traditional indicator of overall glycemic control. The current HbA1c goals recommended by the American Diabetes Association are derived from landmark trials conducted with patients in the general adult diabetic non-CKD population. However, hemoglobin measurements can be confounded by conditions present in ESRD and tend to underestimate glucose measurements in patients with T2DM on HD. Despite this, HbA1c is still regarded as a reasonable measure of glycemic control even in patients with ESRD; however, alternative markers of glycemia may be preferable.11

Although HbA1c is the gold standard, there are other laboratory measures of average glycemic control available. Fructosamine is a ketoamine formed when glucose binds to serum proteins. When these proteins are exposed to high concentrations of glucose, they experience increased glycation. Fructosamine assays measure the total glycated serum proteins, of which albumin accounts for about 90%.11 Because the half-life of serum proteins is about 20 days, fructosamine levels can reflect glycemic control over a 2- to 3-week period. This is advantageous in conditions that affect the average age of red blood cells, in pregnancy where frequent monitoring and measures of short-term glucose control are especially important, and in the evaluation of a medication adjustment in the management of T2DM. However, this test is not without its limitations. It is less reliable in settings of decreased protein levels (eg, liver disease), there is a lack of availability in routine practice, and reference levels have not been established.11

Fructosamine has been shown to be strongly associated with mean blood glucose and HbA1c (Table 2). In 2010, Mittman and colleagues published a study that compared HbA1c with fructosamine and their correlation to glycemic control and morbidity, defined as rates of hospitalization and infection.12 The study included 100 patients with T2DM on HD with a mean age of 63 years, 54% were women, mean HbA1c of 7.2%, and mean dialysis duration of 3 years. Average follow-up was 3 years. At the end of follow-up, Mittman and colleagues found that HbA1c and fructosamine were highly correlated and associated with serum glucose (P < .01). However, fructosamine was found to be more highly correlated with mean glucose levels when those levels were below 150 mg/dL (P = .01). A higher fructosamine level, not HbA1c was a more significant predictor of hospitalization (P = .007) and infection (P = .001). Mittman and colleagues presented evidence for the use of fructosamine over HbA1c in patients with T2DM on HD.12

Hypoglycemic Episodes

At the 2-month follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A reported having 5 hypoglycemic episodes in the past 30 days. He also stated he would forget to take his insulin aspart dose before dinner about 3 to 4 times a week but would take it 30 to 60 minutes after the meal. Mr. A did not bring his glucometer or SMBG readings to the visit, but he indicated that his blood glucose levels continued to fluctuate and were elevated when consuming carbohydrates.

Laboratory tests 1 month prior to the 2-month follow-up visit showed HbA1c of 7.3%, which had increased from his previous level of 6.1%. He was counseled on the proper administration of insulin aspart and lifestyle modifications. A fructosamine level was ordered at this visit to further assess his glycemic control. A follow-up appointment and laboratory workup (fructosamine and HbA1c) were scheduled for 2 months from the visit (Table 3).

Mr. A was educated on the unreliability of his HbA1c levels secondary to his condition of ESRD on HD. He was counseled on the purpose of fructosamine and how it may be a better predictor of his glycemic control and morbidity. Mr. A continued to be followed closely by the primary care CPS for T2DM management.

Discussion

Management of T2DM in patients with ESRD presents challenges for clinicians in determining HbA1c goals and selecting appropriate medication options. The 2012 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) diabetes guideline does not recommend treatment for patients with substantially reduced kidney function to a target HbA1c < 7% due to risk of hypoglycemia.13 Although a target HbA1c > 7% is suggested for these patients, little is known about appropriate glycemic control in these patients as there is a paucity of prospective, randomized clinical trials that include patients with advanced CKD.13

Moreover, many oral antidiabetic medications and their metabolites are cleared by the kidneys and, therefore, pose with potential harm for patients with CKD. Because of this, insulin is the medication of choice for patients with ESRD.7 Although insulin requirements may diminish with worsening kidney function, insulin provides the safest method of glycemic control. Insulin dosing can be individualized according to a patient’s renal status as there is no uniformity in renal dose adjustments. There are some noninsulin antidiabetic agents that can be used in ESRD, but use of these agents requires close monitoring and evaluation of the medication’s pharmacokinetics (Table 4). Overall, medication management can be a difficult task for patients with T2DM and ESRD, but antidiabetic regimens may be reduced or discontinued altogether in burnt-out diabetes.

One of 3 patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis has burnt-out diabetes, defined as a phenomenon in which glucose homeostasis is altered to cause normoglycemia, spontaneous hypoglycemia, and decreased insulin requirements in established patients with T2DM.5 Although Mr. A had a normal-to-low HbA1c, he did not meet these criteria. Due to his elevated SMBG readings, he did not have normoglycemia and did require an increase in his basal insulin dose. Therefore, our patient did not have burnt-out diabetes.

Mr. A represents the relevant issue of inappropriately and unreliably low HbA1c levels due to various factors in ESRD. Our patient did not receive a blood transfusion in the past 2 years and was not on ESA therapy; nevertheless, Mr. A was a patient with ESRD on HD with a diagnosis of anemia. These diagnoses are confounders for low HbA1c values. When fructosamine levels were drawn for Mr. A on September 11, 2018 and November 6, 2018, they correlated well with his serum glucose and SMBG readings. This indicated to the CPS that the patient’s glycemic control was poor despite a promising HbA1c level.

This patient’s case and supporting evidence suggests that other measures of glycemic control (eg, fructosamine) can be used to supplement HbA1c, serum glucose, and glucometer readings to provide an accurate assessment of glycemic control in T2DM. Fructosamine also can assist HbA1c with predicting morbidity and potentially mortality, which are of great importance in this patient population.

Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues conducted a study of 23,618 patients with T2DM on dialysis to observe mortality in association with HbA1c.5 This analysis showed that patients with HbA1c levels < 5% or > 8% had a higher risk of mortality; higher values of HbA1c (> 10%) were associated with increased death risk vs all other values. In the unadjusted analysis, HbA1c levels between 6 and 8% had the lowest death risk (hazard ratios [HR] 0.8 - 0.9, 95% CI) compared with those of higher and lower HbA1c ranges.5 In nonanemic patients, HbA1c > 6% was associated with increased death risk, whereas anemic patients did not show this trend.

Other studies made similar observations. In 2001, Morioka and colleagues published an observational study of 150 patients with DM on intermittent hemodialysis. The study analyzed survival and HbA1c levels at 1, 3, and 5 years. The study found that at 1, 3, and 5 years, patients with HbA1c < 7.5% had better survival than did patients with HbA1c > 7.5% (3.6 years vs 2.0 years, P = .008). Morioka and colleagues also found that there was a 13% increase in death per 1% increase in HbA1c.14 Oomichi and colleagues conducted an observational study of 114 patients with T2DM and ESRD on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with fair control (HbA1c 6.5 - 8%) and good control (HbA1c < 6.5%) were compared with patients with poor control (HbA1c > 8%); it was found that the poor control group had nearly triple the mortality when compared with the good and fair control groups (HR = 2.89, P = .01).15 Park and colleagues also saw a similar observation in a study of 1,239 patients with ESRD and DM; 70% of these patients were on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with poor control (HbA1c ≥ 8%) had worse survival outcomes than those with HbA1c < 8% (HR 2.2, P < .001).16

Our patient case forced us to ask the question, “What should our patient’s HbA1c goals be?” In the study by Oomichi and colleagues, a HbA1c level of 8% has usefulness as a “signpost for management of glycemic control.”15 All patients’ goals should be individualized based on various factors (eg, age, comorbidities), but based on the survival studies above, a HbA1c goal range of 6 to 8% may be optimal.

Conclusions

Patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis may have higher morbidity and mortality rates than the rates of those without T2DM. It has been shown in various studies that very low HbA1c (< 5%) and high HbA1c (> 8%) are associated with poor survival. Some patients with T2DM on dialysis may experience burnt-out diabetes in which they may have normoglycemia and a HbA1c below goal; despite these facts, this condition is not positive and can be linked to bad outcomes. In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice, and we recommend a HbA1c target of 6 to 8%. In this patient population, consider using fructosamine levels or other measures of glycemic control to supplement HbA1c and glucose values to provide a better assessment of glycemic control, morbidity, and mortality. Larger clinical trials are needed to assist in answering questions regarding mortality and optimal HbA1c targets in burnt-out diabetes.

More than 34 million adults in the US have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a chronic progressive disease identified by worsening hyperglycemia and micro- and macrovascular complications.1 Consequently, 12.2% of the US adult population is currently at risk for macrovascular diseases, such as stroke and coronary artery disease (CAD) and microvascular diseases, such as neuropathy and diabetic nephropathy.1

T2DM is the most common comorbid risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). As of 2017, about 750,000 Americans have CKD stage 5 requiring dialysis, and 50% of these patients have preexisting diabetic nephropathy.2 Rates of mortality and morbidity are observed to be higher in patients with both CKD and T2DM compared with patients with CKD without T2DM.2 Previous clinical trials, including the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study of 1998, have proven that optimal glycemic control decreases the risk of complications of T2DM (ie, nephropathy) in the general population.3 Conversely, tight glycemic control that targets hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) < 7%, in patients with T2DM with ESRD has not shown the same benefits and may lead to worse outcomes. It is postulated that this may be due to the increased incidence of hypoglycemia in this patient population.4

Dialysis has varying effects on patients both with and without T2DM. While patients with ESRD without T2DM have the potential to develop impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM, about 33% of patients with T2DM on dialysis actually have HbA1c < 6%.5 In these patients, glycemic control improves spontaneously as their disease progresses, leading to a decrease or cessation of insulin or other antidiabetic medications. This phenomenon, known as burnt-out diabetes, is characterized by (1) alterations in glucose homeostasis and normoglycemia without antidiabetic treatment; (2) HbA1c levels < 6% despite having established T2DM; (3) decline in insulin requirements or cessation of insulin altogether; and (4) spontaneous hypoglycemia.

There is a misconception that burnt-out diabetes is a favorable condition due to the alteration of the natural course of T2DM. Although this may be true, patients with this condition are prone to develop hypoglycemic episodes and may be linked to poor survival outcomes due to low HbA1c.6,7

Since Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues presented a 2009 case study, there has been a lack of research regarding this unique condition.8 The purpose of this case study is to shed further light on burnt-out diabetes and present a patient case pertaining to the challenges of glycemic control in ESRD.

Case Presentation

Mr. A is a 49-year-old Hispanic male veteran with a history of ESRD on hemodialysis (HD) for 6 years, anemia of CKD, and T2DM for 22 years. The patient also has an extensive cardiovascular disease history, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CAD status post-4-vessel coronary artery bypass graft in December 2014. The patient receives in-home HD Monday, Wednesday, and Friday and is on the wait list for kidney transplantation. The patient’s T2DM is managed by a primary care clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS) at the

Mr. A’s antidiabetic regimen is 45 units of subcutaneous insulin glargine every morning; insulin aspart sliding scale (about 15-27 units) subcutaneous 3 times daily with meals; and saxagliptin 2.5 mg by mouth once daily.

At a follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A stated, “I feel fine except for the occasional low blood sugar episode.” The patient’s most recent HbA1c was 6.1%, and he reported medication adherence and no signs or symptoms of hyperglycemia (ie, polydipsia, polyphagia, nocturia, visual disturbances). Mr. A reported no use of alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs. He walks 1 mile every other day and participates in self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG) about 2 to 3 times daily (Table 1).

Although Mr. A’s most recent HbA1c was well controlled, his estimated fasting blood glucose at the same laboratory draw was 224 mg/dL. His SMBG readings in the past month also were elevated with higher readings in the evening. Mr. A attributed the elevated readings to dietary excursions and a high carbohydrate intake. At this visit, the CPS increased his insulin glargine dose to 50 units subcutaneous every morning and educated him on lifestyle modifications. Follow-up with the CPS was scheduled for 2 months from the day of the visit.

Analysis

Few articles on potential contributors to burnt-out diabetes have been published.6,7 These articles discuss decreased renal and hepatic clearance of insulin (which increases its half-life) hypoglycemia during HD, and low HbA1c due to preexisting anemia. Inappropriately low HbA1c levels may be secondary to, but not limited to, hemolysis, recent blood transfusion, acute blood loss, and medications, such as erythropoietin-stimulating agents (ESAs).9 The conditions that affect red blood cell turnover are common in patients with advanced CKD and may result in discrepancies in HbA1c levels.

Glycated hemoglobin is a series of minor hemoglobin components formed by the adduction of various carbohydrate molecules to hemoglobin. HbA1c is the largest fraction formed and the most consistent index of the concentration of glucose in the blood.10 Hence, HbA1c is the traditional indicator of overall glycemic control. The current HbA1c goals recommended by the American Diabetes Association are derived from landmark trials conducted with patients in the general adult diabetic non-CKD population. However, hemoglobin measurements can be confounded by conditions present in ESRD and tend to underestimate glucose measurements in patients with T2DM on HD. Despite this, HbA1c is still regarded as a reasonable measure of glycemic control even in patients with ESRD; however, alternative markers of glycemia may be preferable.11

Although HbA1c is the gold standard, there are other laboratory measures of average glycemic control available. Fructosamine is a ketoamine formed when glucose binds to serum proteins. When these proteins are exposed to high concentrations of glucose, they experience increased glycation. Fructosamine assays measure the total glycated serum proteins, of which albumin accounts for about 90%.11 Because the half-life of serum proteins is about 20 days, fructosamine levels can reflect glycemic control over a 2- to 3-week period. This is advantageous in conditions that affect the average age of red blood cells, in pregnancy where frequent monitoring and measures of short-term glucose control are especially important, and in the evaluation of a medication adjustment in the management of T2DM. However, this test is not without its limitations. It is less reliable in settings of decreased protein levels (eg, liver disease), there is a lack of availability in routine practice, and reference levels have not been established.11

Fructosamine has been shown to be strongly associated with mean blood glucose and HbA1c (Table 2). In 2010, Mittman and colleagues published a study that compared HbA1c with fructosamine and their correlation to glycemic control and morbidity, defined as rates of hospitalization and infection.12 The study included 100 patients with T2DM on HD with a mean age of 63 years, 54% were women, mean HbA1c of 7.2%, and mean dialysis duration of 3 years. Average follow-up was 3 years. At the end of follow-up, Mittman and colleagues found that HbA1c and fructosamine were highly correlated and associated with serum glucose (P < .01). However, fructosamine was found to be more highly correlated with mean glucose levels when those levels were below 150 mg/dL (P = .01). A higher fructosamine level, not HbA1c was a more significant predictor of hospitalization (P = .007) and infection (P = .001). Mittman and colleagues presented evidence for the use of fructosamine over HbA1c in patients with T2DM on HD.12

Hypoglycemic Episodes

At the 2-month follow-up visit with the CPS, Mr. A reported having 5 hypoglycemic episodes in the past 30 days. He also stated he would forget to take his insulin aspart dose before dinner about 3 to 4 times a week but would take it 30 to 60 minutes after the meal. Mr. A did not bring his glucometer or SMBG readings to the visit, but he indicated that his blood glucose levels continued to fluctuate and were elevated when consuming carbohydrates.

Laboratory tests 1 month prior to the 2-month follow-up visit showed HbA1c of 7.3%, which had increased from his previous level of 6.1%. He was counseled on the proper administration of insulin aspart and lifestyle modifications. A fructosamine level was ordered at this visit to further assess his glycemic control. A follow-up appointment and laboratory workup (fructosamine and HbA1c) were scheduled for 2 months from the visit (Table 3).

Mr. A was educated on the unreliability of his HbA1c levels secondary to his condition of ESRD on HD. He was counseled on the purpose of fructosamine and how it may be a better predictor of his glycemic control and morbidity. Mr. A continued to be followed closely by the primary care CPS for T2DM management.

Discussion

Management of T2DM in patients with ESRD presents challenges for clinicians in determining HbA1c goals and selecting appropriate medication options. The 2012 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) diabetes guideline does not recommend treatment for patients with substantially reduced kidney function to a target HbA1c < 7% due to risk of hypoglycemia.13 Although a target HbA1c > 7% is suggested for these patients, little is known about appropriate glycemic control in these patients as there is a paucity of prospective, randomized clinical trials that include patients with advanced CKD.13

Moreover, many oral antidiabetic medications and their metabolites are cleared by the kidneys and, therefore, pose with potential harm for patients with CKD. Because of this, insulin is the medication of choice for patients with ESRD.7 Although insulin requirements may diminish with worsening kidney function, insulin provides the safest method of glycemic control. Insulin dosing can be individualized according to a patient’s renal status as there is no uniformity in renal dose adjustments. There are some noninsulin antidiabetic agents that can be used in ESRD, but use of these agents requires close monitoring and evaluation of the medication’s pharmacokinetics (Table 4). Overall, medication management can be a difficult task for patients with T2DM and ESRD, but antidiabetic regimens may be reduced or discontinued altogether in burnt-out diabetes.

One of 3 patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis has burnt-out diabetes, defined as a phenomenon in which glucose homeostasis is altered to cause normoglycemia, spontaneous hypoglycemia, and decreased insulin requirements in established patients with T2DM.5 Although Mr. A had a normal-to-low HbA1c, he did not meet these criteria. Due to his elevated SMBG readings, he did not have normoglycemia and did require an increase in his basal insulin dose. Therefore, our patient did not have burnt-out diabetes.

Mr. A represents the relevant issue of inappropriately and unreliably low HbA1c levels due to various factors in ESRD. Our patient did not receive a blood transfusion in the past 2 years and was not on ESA therapy; nevertheless, Mr. A was a patient with ESRD on HD with a diagnosis of anemia. These diagnoses are confounders for low HbA1c values. When fructosamine levels were drawn for Mr. A on September 11, 2018 and November 6, 2018, they correlated well with his serum glucose and SMBG readings. This indicated to the CPS that the patient’s glycemic control was poor despite a promising HbA1c level.

This patient’s case and supporting evidence suggests that other measures of glycemic control (eg, fructosamine) can be used to supplement HbA1c, serum glucose, and glucometer readings to provide an accurate assessment of glycemic control in T2DM. Fructosamine also can assist HbA1c with predicting morbidity and potentially mortality, which are of great importance in this patient population.

Kalantar-Zadeh and colleagues conducted a study of 23,618 patients with T2DM on dialysis to observe mortality in association with HbA1c.5 This analysis showed that patients with HbA1c levels < 5% or > 8% had a higher risk of mortality; higher values of HbA1c (> 10%) were associated with increased death risk vs all other values. In the unadjusted analysis, HbA1c levels between 6 and 8% had the lowest death risk (hazard ratios [HR] 0.8 - 0.9, 95% CI) compared with those of higher and lower HbA1c ranges.5 In nonanemic patients, HbA1c > 6% was associated with increased death risk, whereas anemic patients did not show this trend.

Other studies made similar observations. In 2001, Morioka and colleagues published an observational study of 150 patients with DM on intermittent hemodialysis. The study analyzed survival and HbA1c levels at 1, 3, and 5 years. The study found that at 1, 3, and 5 years, patients with HbA1c < 7.5% had better survival than did patients with HbA1c > 7.5% (3.6 years vs 2.0 years, P = .008). Morioka and colleagues also found that there was a 13% increase in death per 1% increase in HbA1c.14 Oomichi and colleagues conducted an observational study of 114 patients with T2DM and ESRD on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with fair control (HbA1c 6.5 - 8%) and good control (HbA1c < 6.5%) were compared with patients with poor control (HbA1c > 8%); it was found that the poor control group had nearly triple the mortality when compared with the good and fair control groups (HR = 2.89, P = .01).15 Park and colleagues also saw a similar observation in a study of 1,239 patients with ESRD and DM; 70% of these patients were on intermittent hemodialysis. Patients with poor control (HbA1c ≥ 8%) had worse survival outcomes than those with HbA1c < 8% (HR 2.2, P < .001).16

Our patient case forced us to ask the question, “What should our patient’s HbA1c goals be?” In the study by Oomichi and colleagues, a HbA1c level of 8% has usefulness as a “signpost for management of glycemic control.”15 All patients’ goals should be individualized based on various factors (eg, age, comorbidities), but based on the survival studies above, a HbA1c goal range of 6 to 8% may be optimal.

Conclusions

Patients with T2DM and ESRD on dialysis may have higher morbidity and mortality rates than the rates of those without T2DM. It has been shown in various studies that very low HbA1c (< 5%) and high HbA1c (> 8%) are associated with poor survival. Some patients with T2DM on dialysis may experience burnt-out diabetes in which they may have normoglycemia and a HbA1c below goal; despite these facts, this condition is not positive and can be linked to bad outcomes. In patients with T2DM and ESRD, insulin is the antidiabetic medication of choice, and we recommend a HbA1c target of 6 to 8%. In this patient population, consider using fructosamine levels or other measures of glycemic control to supplement HbA1c and glucose values to provide a better assessment of glycemic control, morbidity, and mortality. Larger clinical trials are needed to assist in answering questions regarding mortality and optimal HbA1c targets in burnt-out diabetes.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2020.

2. Saran R, Robinson B, et al. US renal data system 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of klidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Jan;75(1 suppl 1):A6-A7. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Nov 5.

3. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):854-865.

4. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545-2559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

5. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Regidor DL, et al. A1c and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1049-10.55. doi:10.2337/dc06-2127

6. Park J, Lertdumrongluk P, Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Glycemic control in diabetic dialysis patients and the burnt-out diabetes phenomenon. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(4):432-439. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0286-3

7. Rhee CM, Leung AM, Kovesdy CP, Lynch KE, Brent GA, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Updates on the management of diabetes in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2014;27(2):135-145. doi:10.1111/sdi.12198

8. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Derose SF, Nicholas S, Benner D, Sharma K, Kovesdy CP. Burnt-out diabetes: impact of chronic kidney disease progression on the natural course of diabetes mellitus. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19(1):33-37. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2008.11.012

9. Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Drugs affecting HbA1c levels. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):528-531. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.98004

10. Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(6):1572-1583. doi:10.1177/193229681100500634

11. Wright LAC, Hirsch IB. The challenge of the use of glycemic biomarkers in diabetes: reflecting on hemoglobin A1c, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, and the glycated proteins fructosamine and glycated albumin. Diabetes Spectr. 2012;25(3):141-148. doi:10.2337/diaspect.25.3.141

12. Mittman N, Desiraju B, Fazil I, et al. Serum fructosamine versus glycosylated hemoglobin as an index of glycemic control, hospitalization, and infection in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78 (suppl 117):S41-S45. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.193

13. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850-886. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005

14. Morioka T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Glycemic control is a predictor of survival for diabetic patients on hemodialysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):909-913. doi.10.2337/diacare.24.5.909

15. Oomichi T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Impact of glycemic control on survival of diabetic patients on chronic regular hemodialysis: a 7-year observational study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1496-1500. doi:10.2337/dc05-1887

16. Park JI, Bae E, Kim YL, et al. Glycemic control and mortality in diabetic patients undergoing dialysis focusing on the effects of age and dialysis type: a prospective cohort study in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136085. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136085

17. Glucotrol tablets [

18. Amaryl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; December 2018.

19. Glucophage [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; May 2018.

20. Actos [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; December 2017.

21. Precose [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; March 2015.

22. Nesina [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; June 2019.

23. Victoza [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc; June 2019.

24. Jardiance [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc; October 2018.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Updated August 28, 2020. Accessed November 17, 2020.

2. Saran R, Robinson B, et al. US renal data system 2019 annual data report: epidemiology of klidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Jan;75(1 suppl 1):A6-A7. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Nov 5.

3. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998;352(9131):854-865.

4. Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545-2559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802743

5. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Regidor DL, et al. A1c and survival in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(5):1049-10.55. doi:10.2337/dc06-2127

6. Park J, Lertdumrongluk P, Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Glycemic control in diabetic dialysis patients and the burnt-out diabetes phenomenon. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(4):432-439. doi:10.1007/s11892-012-0286-3

7. Rhee CM, Leung AM, Kovesdy CP, Lynch KE, Brent GA, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Updates on the management of diabetes in dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2014;27(2):135-145. doi:10.1111/sdi.12198

8. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Derose SF, Nicholas S, Benner D, Sharma K, Kovesdy CP. Burnt-out diabetes: impact of chronic kidney disease progression on the natural course of diabetes mellitus. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19(1):33-37. doi:10.1053/j.jrn.2008.11.012

9. Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. Drugs affecting HbA1c levels. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):528-531. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.98004

10. Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(6):1572-1583. doi:10.1177/193229681100500634

11. Wright LAC, Hirsch IB. The challenge of the use of glycemic biomarkers in diabetes: reflecting on hemoglobin A1c, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, and the glycated proteins fructosamine and glycated albumin. Diabetes Spectr. 2012;25(3):141-148. doi:10.2337/diaspect.25.3.141

12. Mittman N, Desiraju B, Fazil I, et al. Serum fructosamine versus glycosylated hemoglobin as an index of glycemic control, hospitalization, and infection in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78 (suppl 117):S41-S45. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.193

13. National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(5):850-886. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005

14. Morioka T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Glycemic control is a predictor of survival for diabetic patients on hemodialysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(5):909-913. doi.10.2337/diacare.24.5.909

15. Oomichi T, Emoto M, Tabata T, et al. Impact of glycemic control on survival of diabetic patients on chronic regular hemodialysis: a 7-year observational study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(7):1496-1500. doi:10.2337/dc05-1887

16. Park JI, Bae E, Kim YL, et al. Glycemic control and mortality in diabetic patients undergoing dialysis focusing on the effects of age and dialysis type: a prospective cohort study in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136085. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136085

17. Glucotrol tablets [

18. Amaryl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-Aventis; December 2018.

19. Glucophage [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; May 2018.

20. Actos [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; December 2017.

21. Precose [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; March 2015.

22. Nesina [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc; June 2019.

23. Victoza [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc; June 2019.

24. Jardiance [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc; October 2018.

Recalled to Life: The Best and Worst of 2020 Is the Year 2020

Some who read Federal Practitioner regularly may recall that since 2017, I have been dedicating the December and January editorials to a more substantive version of the popular best and worst awards that appear in the media this time of year. Everything from the most comfortable slippers to the weirdest lawsuits is scored annually. In an effort to elevate the ranking routine, this column has reviewed and evaluated ethical and unethical events and decisions in the 3 federal health care systems Federal Practitioner primarily serves. In previous years it was a challenge requiring research and deliberation to select the most inspiring and troubling occurrences in the world of federal health care. This year neither great effort or prolonged study was required as the choice was immediate and obvious—the year itself. A year in which our individual identities as health care professionals serving in the US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and US Public Health Service is subsumed in our realities as citizens of a nation in crisis.

The opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities have become such a literary platitude taken out of the context of the novel that the terror and fascination with which Dickens wrote these oft-quoted lines has been diluted and dulled.1 In citing the entire paragraph as the epigraph, I hope to recapture the moral seriousness of its message, which is so relevant in 2020. While protesting the widespread injustice that fueled the progress of London’s industrial revolution, Dickens also feared such discontent would ignite a bloody uprising as it had done in Paris.1 This passage is a classic example of the literary device of parallelism that so perfectly expressed Dickens’ reflections on the trajectory of the unprecedented historical impact of the French Revolution. A parallelism that also aptly captures the contemporary contrasts and comparisons of the best and worst of 2020.

It is estimated that at least 66% of those eligible to vote did so on November 3, 2020, the highest turnout in more than a century, demonstrating the strength of the United States as a representative democracy.2 It is not about partisan politics, it is that more than 150 million citizens braved the winter, the virus, and potential intimidation to cast a ballot for their values.3 Still, America has never been more divided, and Dickens’ fear of political upheaval has never been more real in our country, or at least since the Civil War.

As I write this editorial, manufacturers for 2 vaccines have submitted phase 3 trial data to the US Food and Drug Administration for Emergency Use Authorizations and a third consortium may follow suit soon. Scientists report that the 2 vaccines, which were developed in less than a year, have high efficacy rates (> 90%) with only modest adverse effects.4 It is an unparalleled, really unimaginable, scientific feat. Americans’ characteristic gift for logistical efficiency and scientific innovation faces daunting administrative and technical barriers to achieve a similar viral victory, yet we may have faced even more formidable odds in World War II.

As of December 4, 2020, Johns Hopkins University reports that more than 275,000 Americans have died of coronavirus.5 The United States is on track to reach 200,000 cases a day with the signature holiday season of family festivities brutally morphed into gatherings of contagion.6 Hospitals across the country are running out of intensive care beds and nurses and doctors to staff them. Unlike the Spring surge in the Northeast, cases are rising in 49 states, and there is nowhere in the land from which respite and reinforcements can come.7

Thousands of health care professionals are exhausted, many with COVID-19 or recovering from it, morally distressed, and emotionally spent. Masks and social distancing are no longer public health essentials but elements of a culture war. Those same nurses, doctors, and public health officers still show up day after night for what is much closer to war than work. They struggle to prevent patients from going on ventilators they may never come off and use the few available therapies to keep as many patients alive as possible—whether those patients believe in COVID-19, wore a mask, no matter who they voted for—because that is what it means to practice health care according to a code of ethics.

In March 2020, I pledged to devote every editorial to COVID-19 for as long as the pandemic lasted, as one small candle for all those who have died of COVID-19, who are suffering as survivors of it, and who take risks and labor to deliver essential services from groceries to intensive care. Prudent public health officials wisely advise that the vaccine(s) are not a miracle cure to revive a depleted country, in part because it may undermine life-saving public health measures.8 And so the columns will continue in 2021 to illuminate the ethical issues of the pandemic as they affect all of us as federal health care professionals and Americans.

The Tale of Two Cities chapter that begins with the “best of times, and the worst of times” is entitled “Recalled to Life.” Let that be our hope and prayer for the coming year.

1. Dickens C. A Tale of Two Cities. Douglas-Fairhust ed. New York: Norton; 2020.

2. Schaul K, Rabinowitz K, Mellnik T. 2020 turnout is the highest in over a century. Washington Post, November 5, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/elections/voter-turnout. Accessed November 23, 2020.

3. Desilver D. In past elections, U.S. trailed most developed countries in voter turnout. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout. Published November 3, 2020. Accessed November 23, 2020.

4. Herper M, Garde D. Moderna to submit Covid-19 vaccine to FDA as full results show 94% efficacy.https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/30/moderna-covid-19-vaccine-full-results. Published November 30, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

5. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus research center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Updated November 23, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2020.

6. Hawkins D, Knowles H. As U.S. coronavirus cases soar toward 200,000 a day holiday travel is surging. Washington Post, November 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/11/21/coronavirus-thanksgiving-travel. Accessed November 23, 2020.

7. Goldhill O. ‘People are going to die’: Hospitals in half the states are facing massive staffing shortages as COVID-19 surges. November 19, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/19/covid19-hospitals-in-half-the-states-facing-massive-staffing-shortage. Published November 19, 2020. Accessed November 23, 2020.

8. Lazar K. Is Pfizer’s vaccine a ‘magic bullet?’ Scientists warn masks, distancing may last well into 2021. Boston Globe . November 9, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/11/09/metro/is-pfizer-vaccine-magic-bullet-scientists-warn-public-should-be-prepared-live-with-masks-social-distancing-months. Accessed November 23, 2020.

Some who read Federal Practitioner regularly may recall that since 2017, I have been dedicating the December and January editorials to a more substantive version of the popular best and worst awards that appear in the media this time of year. Everything from the most comfortable slippers to the weirdest lawsuits is scored annually. In an effort to elevate the ranking routine, this column has reviewed and evaluated ethical and unethical events and decisions in the 3 federal health care systems Federal Practitioner primarily serves. In previous years it was a challenge requiring research and deliberation to select the most inspiring and troubling occurrences in the world of federal health care. This year neither great effort or prolonged study was required as the choice was immediate and obvious—the year itself. A year in which our individual identities as health care professionals serving in the US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and US Public Health Service is subsumed in our realities as citizens of a nation in crisis.

The opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities have become such a literary platitude taken out of the context of the novel that the terror and fascination with which Dickens wrote these oft-quoted lines has been diluted and dulled.1 In citing the entire paragraph as the epigraph, I hope to recapture the moral seriousness of its message, which is so relevant in 2020. While protesting the widespread injustice that fueled the progress of London’s industrial revolution, Dickens also feared such discontent would ignite a bloody uprising as it had done in Paris.1 This passage is a classic example of the literary device of parallelism that so perfectly expressed Dickens’ reflections on the trajectory of the unprecedented historical impact of the French Revolution. A parallelism that also aptly captures the contemporary contrasts and comparisons of the best and worst of 2020.

It is estimated that at least 66% of those eligible to vote did so on November 3, 2020, the highest turnout in more than a century, demonstrating the strength of the United States as a representative democracy.2 It is not about partisan politics, it is that more than 150 million citizens braved the winter, the virus, and potential intimidation to cast a ballot for their values.3 Still, America has never been more divided, and Dickens’ fear of political upheaval has never been more real in our country, or at least since the Civil War.

As I write this editorial, manufacturers for 2 vaccines have submitted phase 3 trial data to the US Food and Drug Administration for Emergency Use Authorizations and a third consortium may follow suit soon. Scientists report that the 2 vaccines, which were developed in less than a year, have high efficacy rates (> 90%) with only modest adverse effects.4 It is an unparalleled, really unimaginable, scientific feat. Americans’ characteristic gift for logistical efficiency and scientific innovation faces daunting administrative and technical barriers to achieve a similar viral victory, yet we may have faced even more formidable odds in World War II.

As of December 4, 2020, Johns Hopkins University reports that more than 275,000 Americans have died of coronavirus.5 The United States is on track to reach 200,000 cases a day with the signature holiday season of family festivities brutally morphed into gatherings of contagion.6 Hospitals across the country are running out of intensive care beds and nurses and doctors to staff them. Unlike the Spring surge in the Northeast, cases are rising in 49 states, and there is nowhere in the land from which respite and reinforcements can come.7

Thousands of health care professionals are exhausted, many with COVID-19 or recovering from it, morally distressed, and emotionally spent. Masks and social distancing are no longer public health essentials but elements of a culture war. Those same nurses, doctors, and public health officers still show up day after night for what is much closer to war than work. They struggle to prevent patients from going on ventilators they may never come off and use the few available therapies to keep as many patients alive as possible—whether those patients believe in COVID-19, wore a mask, no matter who they voted for—because that is what it means to practice health care according to a code of ethics.

In March 2020, I pledged to devote every editorial to COVID-19 for as long as the pandemic lasted, as one small candle for all those who have died of COVID-19, who are suffering as survivors of it, and who take risks and labor to deliver essential services from groceries to intensive care. Prudent public health officials wisely advise that the vaccine(s) are not a miracle cure to revive a depleted country, in part because it may undermine life-saving public health measures.8 And so the columns will continue in 2021 to illuminate the ethical issues of the pandemic as they affect all of us as federal health care professionals and Americans.

The Tale of Two Cities chapter that begins with the “best of times, and the worst of times” is entitled “Recalled to Life.” Let that be our hope and prayer for the coming year.

Some who read Federal Practitioner regularly may recall that since 2017, I have been dedicating the December and January editorials to a more substantive version of the popular best and worst awards that appear in the media this time of year. Everything from the most comfortable slippers to the weirdest lawsuits is scored annually. In an effort to elevate the ranking routine, this column has reviewed and evaluated ethical and unethical events and decisions in the 3 federal health care systems Federal Practitioner primarily serves. In previous years it was a challenge requiring research and deliberation to select the most inspiring and troubling occurrences in the world of federal health care. This year neither great effort or prolonged study was required as the choice was immediate and obvious—the year itself. A year in which our individual identities as health care professionals serving in the US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and US Public Health Service is subsumed in our realities as citizens of a nation in crisis.

The opening lines of A Tale of Two Cities have become such a literary platitude taken out of the context of the novel that the terror and fascination with which Dickens wrote these oft-quoted lines has been diluted and dulled.1 In citing the entire paragraph as the epigraph, I hope to recapture the moral seriousness of its message, which is so relevant in 2020. While protesting the widespread injustice that fueled the progress of London’s industrial revolution, Dickens also feared such discontent would ignite a bloody uprising as it had done in Paris.1 This passage is a classic example of the literary device of parallelism that so perfectly expressed Dickens’ reflections on the trajectory of the unprecedented historical impact of the French Revolution. A parallelism that also aptly captures the contemporary contrasts and comparisons of the best and worst of 2020.

It is estimated that at least 66% of those eligible to vote did so on November 3, 2020, the highest turnout in more than a century, demonstrating the strength of the United States as a representative democracy.2 It is not about partisan politics, it is that more than 150 million citizens braved the winter, the virus, and potential intimidation to cast a ballot for their values.3 Still, America has never been more divided, and Dickens’ fear of political upheaval has never been more real in our country, or at least since the Civil War.

As I write this editorial, manufacturers for 2 vaccines have submitted phase 3 trial data to the US Food and Drug Administration for Emergency Use Authorizations and a third consortium may follow suit soon. Scientists report that the 2 vaccines, which were developed in less than a year, have high efficacy rates (> 90%) with only modest adverse effects.4 It is an unparalleled, really unimaginable, scientific feat. Americans’ characteristic gift for logistical efficiency and scientific innovation faces daunting administrative and technical barriers to achieve a similar viral victory, yet we may have faced even more formidable odds in World War II.

As of December 4, 2020, Johns Hopkins University reports that more than 275,000 Americans have died of coronavirus.5 The United States is on track to reach 200,000 cases a day with the signature holiday season of family festivities brutally morphed into gatherings of contagion.6 Hospitals across the country are running out of intensive care beds and nurses and doctors to staff them. Unlike the Spring surge in the Northeast, cases are rising in 49 states, and there is nowhere in the land from which respite and reinforcements can come.7

Thousands of health care professionals are exhausted, many with COVID-19 or recovering from it, morally distressed, and emotionally spent. Masks and social distancing are no longer public health essentials but elements of a culture war. Those same nurses, doctors, and public health officers still show up day after night for what is much closer to war than work. They struggle to prevent patients from going on ventilators they may never come off and use the few available therapies to keep as many patients alive as possible—whether those patients believe in COVID-19, wore a mask, no matter who they voted for—because that is what it means to practice health care according to a code of ethics.

In March 2020, I pledged to devote every editorial to COVID-19 for as long as the pandemic lasted, as one small candle for all those who have died of COVID-19, who are suffering as survivors of it, and who take risks and labor to deliver essential services from groceries to intensive care. Prudent public health officials wisely advise that the vaccine(s) are not a miracle cure to revive a depleted country, in part because it may undermine life-saving public health measures.8 And so the columns will continue in 2021 to illuminate the ethical issues of the pandemic as they affect all of us as federal health care professionals and Americans.

The Tale of Two Cities chapter that begins with the “best of times, and the worst of times” is entitled “Recalled to Life.” Let that be our hope and prayer for the coming year.

1. Dickens C. A Tale of Two Cities. Douglas-Fairhust ed. New York: Norton; 2020.

2. Schaul K, Rabinowitz K, Mellnik T. 2020 turnout is the highest in over a century. Washington Post, November 5, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/elections/voter-turnout. Accessed November 23, 2020.

3. Desilver D. In past elections, U.S. trailed most developed countries in voter turnout. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout. Published November 3, 2020. Accessed November 23, 2020.

4. Herper M, Garde D. Moderna to submit Covid-19 vaccine to FDA as full results show 94% efficacy.https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/30/moderna-covid-19-vaccine-full-results. Published November 30, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

5. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus research center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Updated November 23, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2020.

6. Hawkins D, Knowles H. As U.S. coronavirus cases soar toward 200,000 a day holiday travel is surging. Washington Post, November 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/11/21/coronavirus-thanksgiving-travel. Accessed November 23, 2020.

7. Goldhill O. ‘People are going to die’: Hospitals in half the states are facing massive staffing shortages as COVID-19 surges. November 19, 2020. https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/19/covid19-hospitals-in-half-the-states-facing-massive-staffing-shortage. Published November 19, 2020. Accessed November 23, 2020.

8. Lazar K. Is Pfizer’s vaccine a ‘magic bullet?’ Scientists warn masks, distancing may last well into 2021. Boston Globe . November 9, 2020. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/11/09/metro/is-pfizer-vaccine-magic-bullet-scientists-warn-public-should-be-prepared-live-with-masks-social-distancing-months. Accessed November 23, 2020.

1. Dickens C. A Tale of Two Cities. Douglas-Fairhust ed. New York: Norton; 2020.

2. Schaul K, Rabinowitz K, Mellnik T. 2020 turnout is the highest in over a century. Washington Post, November 5, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/elections/voter-turnout. Accessed November 23, 2020.

3. Desilver D. In past elections, U.S. trailed most developed countries in voter turnout. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/11/03/in-past-elections-u-s-trailed-most-developed-countries-in-voter-turnout. Published November 3, 2020. Accessed November 23, 2020.

4. Herper M, Garde D. Moderna to submit Covid-19 vaccine to FDA as full results show 94% efficacy.https://www.statnews.com/2020/11/30/moderna-covid-19-vaccine-full-results. Published November 30, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2020.

5. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus research center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Updated November 23, 2020. Accessed December 4, 2020.