User login

COVID-19: Hand sanitizer poisonings soar, psych patients at high risk

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of poisoning – intentional and unintentional – from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United Kingdom alone, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service jumped 157% – from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between Jan. 1 and Sept. 14, 2020, new research shows.

More needs to be done to protect those at risk of unintentional and intentional swallowing of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, including children, people with dementia/confusion, and those with mental health issues, according to Georgia Richards, DPhil student, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford (England).

“If providers are supplying alcohol-based hand sanitizers in the community to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2, Ms. Richards said in an interview.

The study was published online Dec. 1 in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.

European, U.S. poisoning rates soar

In the paper Ms. Richards described two deaths that occurred in hospitals in England.

In one case, a 30-year-old woman, detained in a psychiatric unit who received the antidepressant venlafaxine was found dead in her hospital bed with a container of hand-sanitizing gel beside her.

“The gel was readily accessible to patients on the ward from a communal dispenser, and patients were allowed to fill cups or other containers with it to keep in their rooms,” Ms. Richards reported.

A postmortem analysis found a high level of alcohol in her blood (214 mg of alcohol in 100 mL of blood). The medical cause of death was listed as “ingestion of alcohol and venlafaxine.” The coroner concluded that the combination of these substances suppressed the patient’s breathing, leading to her death.

The other case involved a 76-year-old man who unintentionally swallowed an unknown quantity of alcohol-based hand-sanitizing foam attached to the foot of his hospital bed.

The patient had a history of agitation and depression and was treated with antidepressants. He had become increasingly confused over the preceding 9 months, possibly because of vascular dementia.

His blood ethanol concentration was 463 mg/dL (100 mmol/L) initially and 354 mg/dL (77mmol/L) 10 hours later. He was admitted to the ICU, where he received lorazepam and haloperidol and treated with ventilation, with a plan to allow the alcohol to be naturally metabolized.

The patient developed complications and died 6 days later. The primary causes of death were bronchopneumonia and acute alcohol toxicity, secondary to acute delirium and coronary artery disease.

Since COVID-19 started, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are among the most sought-after commodities around the world. The volume of these products – now found in homes, hospitals, schools, workplaces, and elsewhere – “may be a cause for concern,” Ms. Richards wrote.

Yet, warnings about the toxicity and lethality of intentional or unintentional ingestion of these products have not been widely disseminated, she noted.

To reduce the risk of harm, Ms. Richards suggested educating the public and health care professionals, improving warning labels on products, and increasing the awareness and reporting of such exposures to public health authorities.

“While governments and public health authorities have successfully heightened our awareness of, and need for, better hand hygiene during the COVID-19 outbreak, they must also make the public aware of the potential harms and encourage the reporting of such harms to poisons information centers,” she noted.

Increases in alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisoning during the pandemic have also been reported in the United States.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers reports that data from the National Poison Data System show 32,892 hand sanitizer exposure cases reported to the 55 U.S. poison control centers from Jan. 1 to Nov. 15, 2020 – an increase of 73%, compared with the same time period during the previous year.

An increase in self-harm

Weighing in on this issue, Robert Bassett, DO, associate medical director of the Poison Control Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview that “cleaning agents and disinfectants have been around for eons and their potential for toxicity hasn’t changed.

“Now with COVID, and this hypervigilance when it comes to cleanliness, there is increased access and the exposure risk has gone up,” he said.

“One of the sad casualties of an overstressed health care system and a globally depressed environment is worsening behavioral health emergencies and, as part of that, the risk of self-harm goes up,” Dr. Bassett added.

“The consensus is that there has been an exacerbation of behavioral health emergencies and behavioral health needs since COVID started and hand sanitizers are readily accessible to someone who may be looking to self-harm,” he said.

This research had no specific funding. Ms. Richards is the editorial registrar of BMJ Evidence Based Medicine and is developing a website to track preventable deaths. Dr. Bassett disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Addressing Maternal Mortality Through Education: The Mommies Methadone Program

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

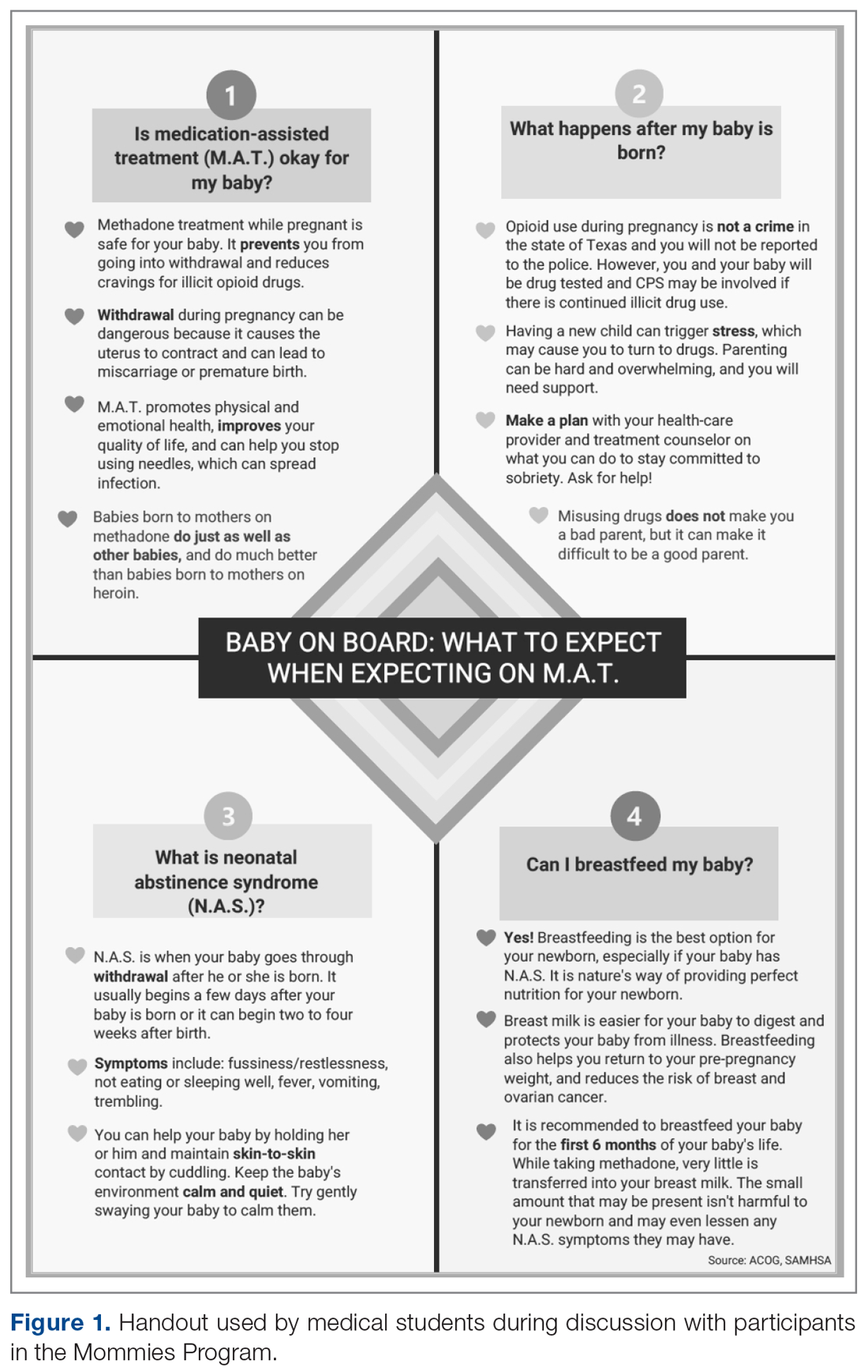

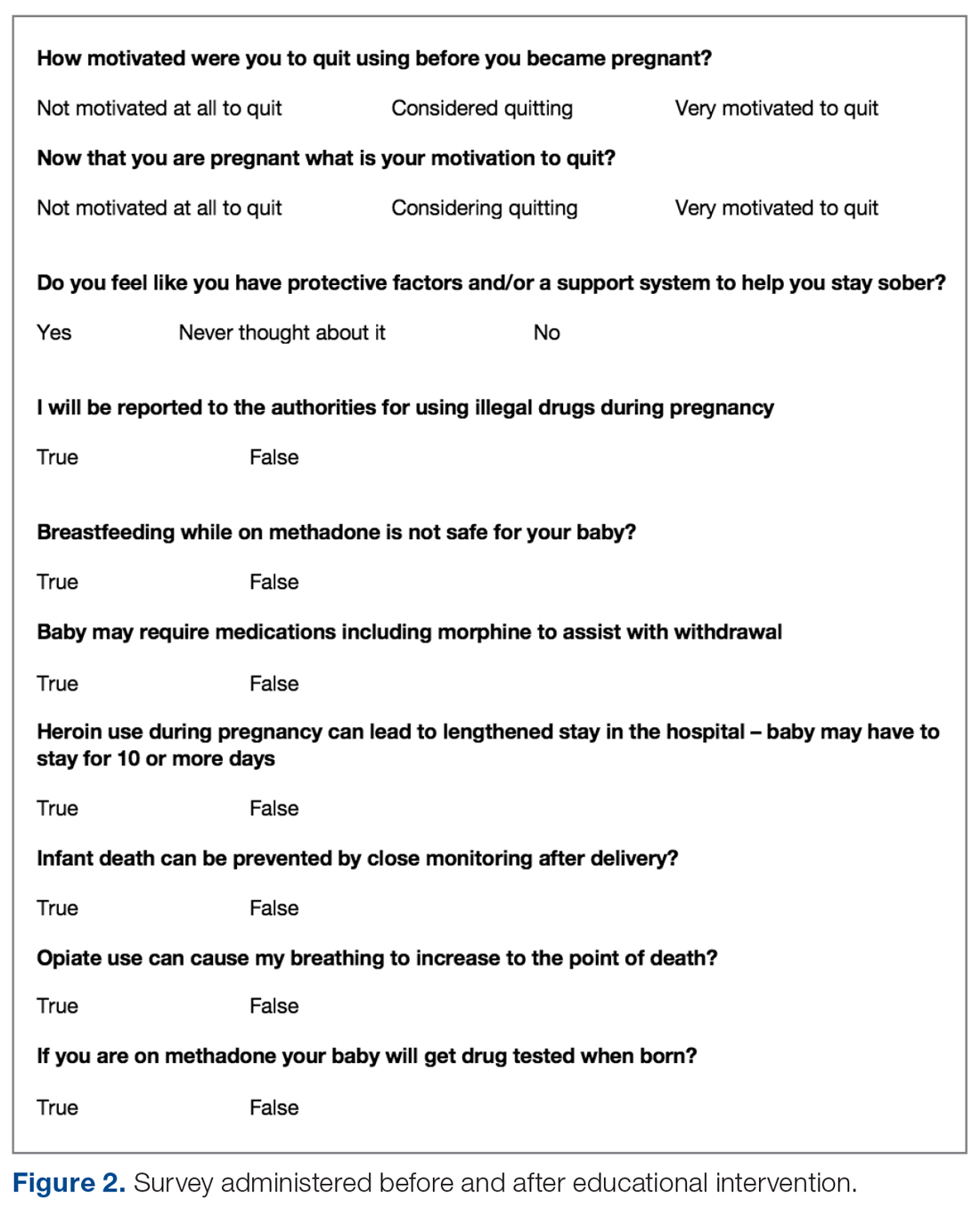

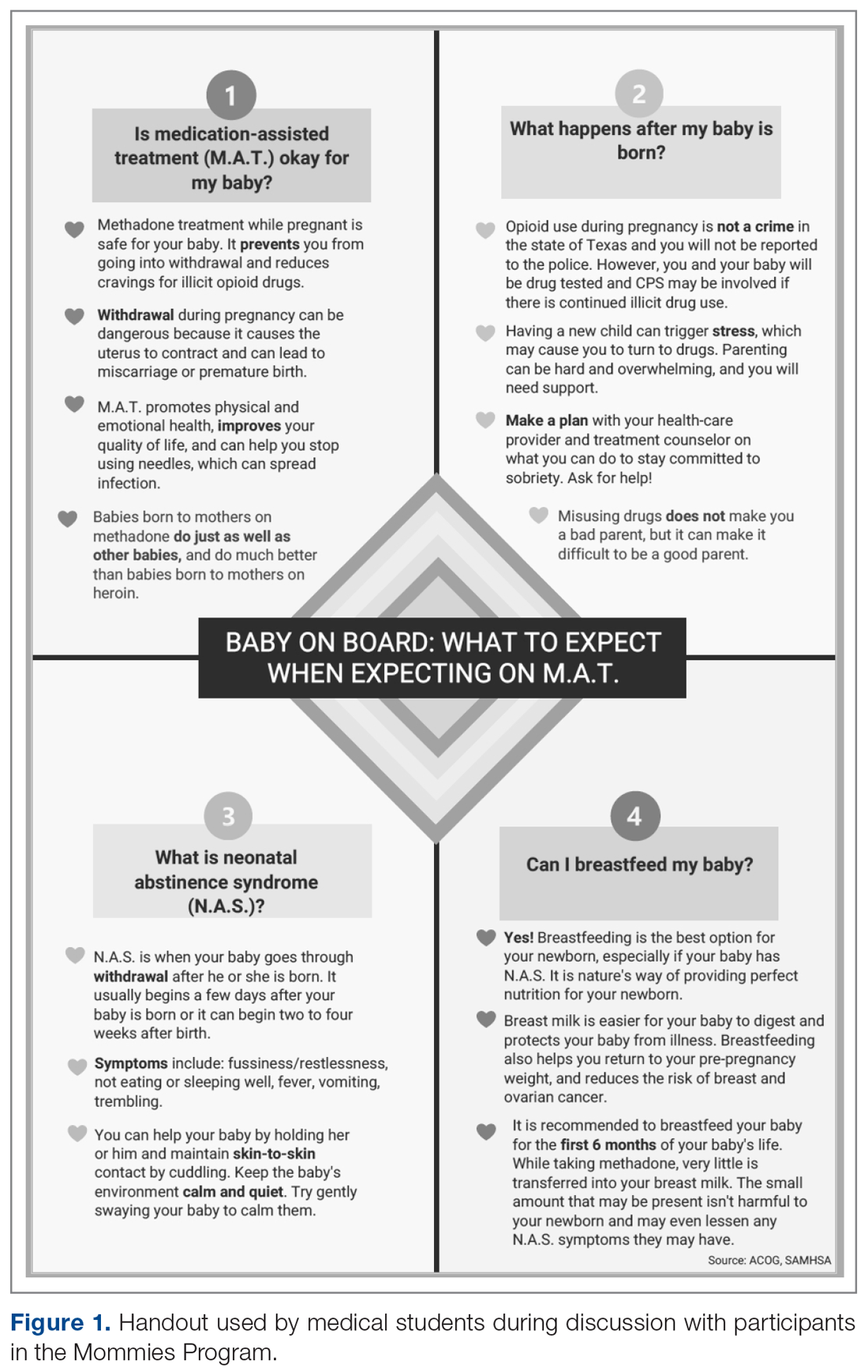

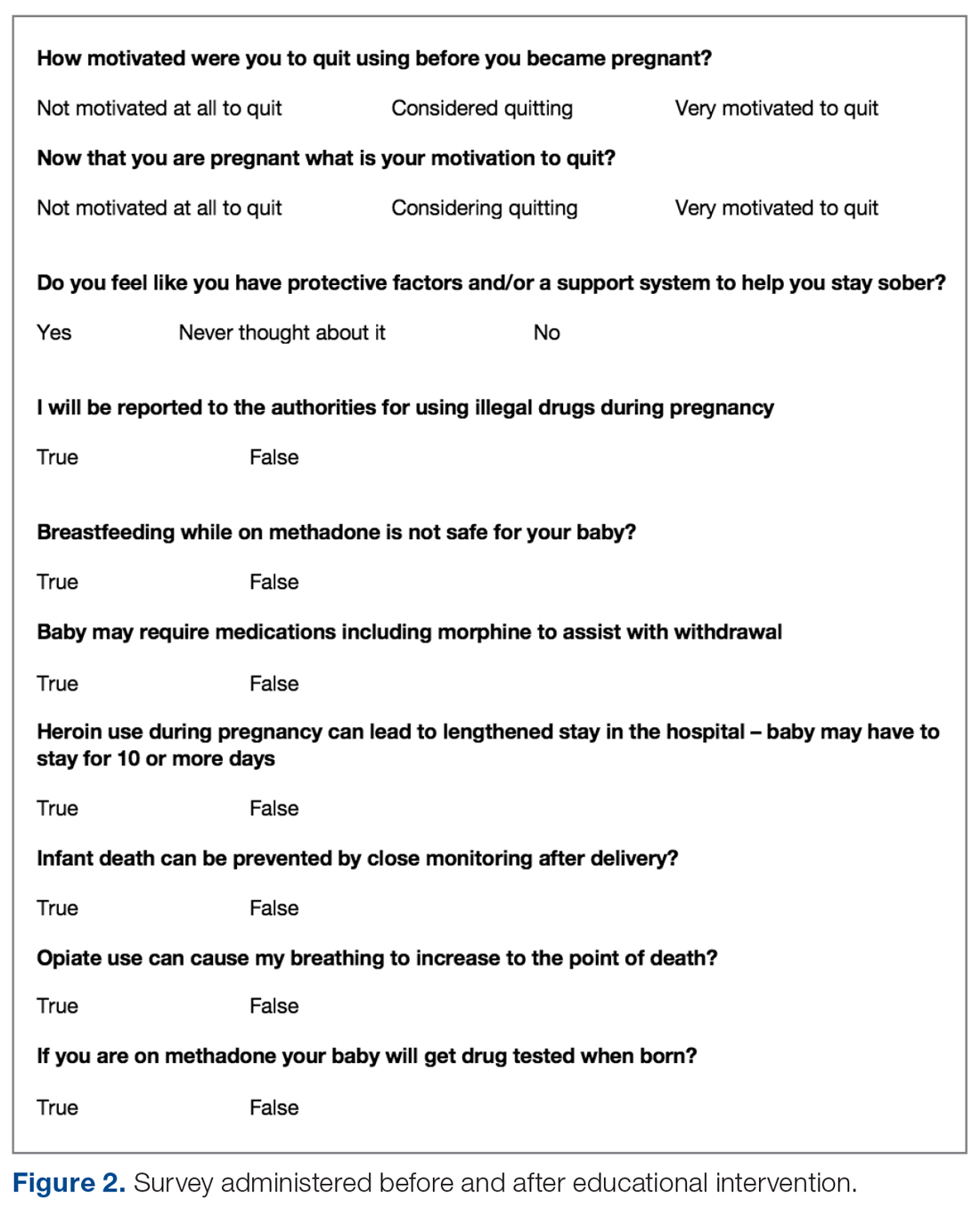

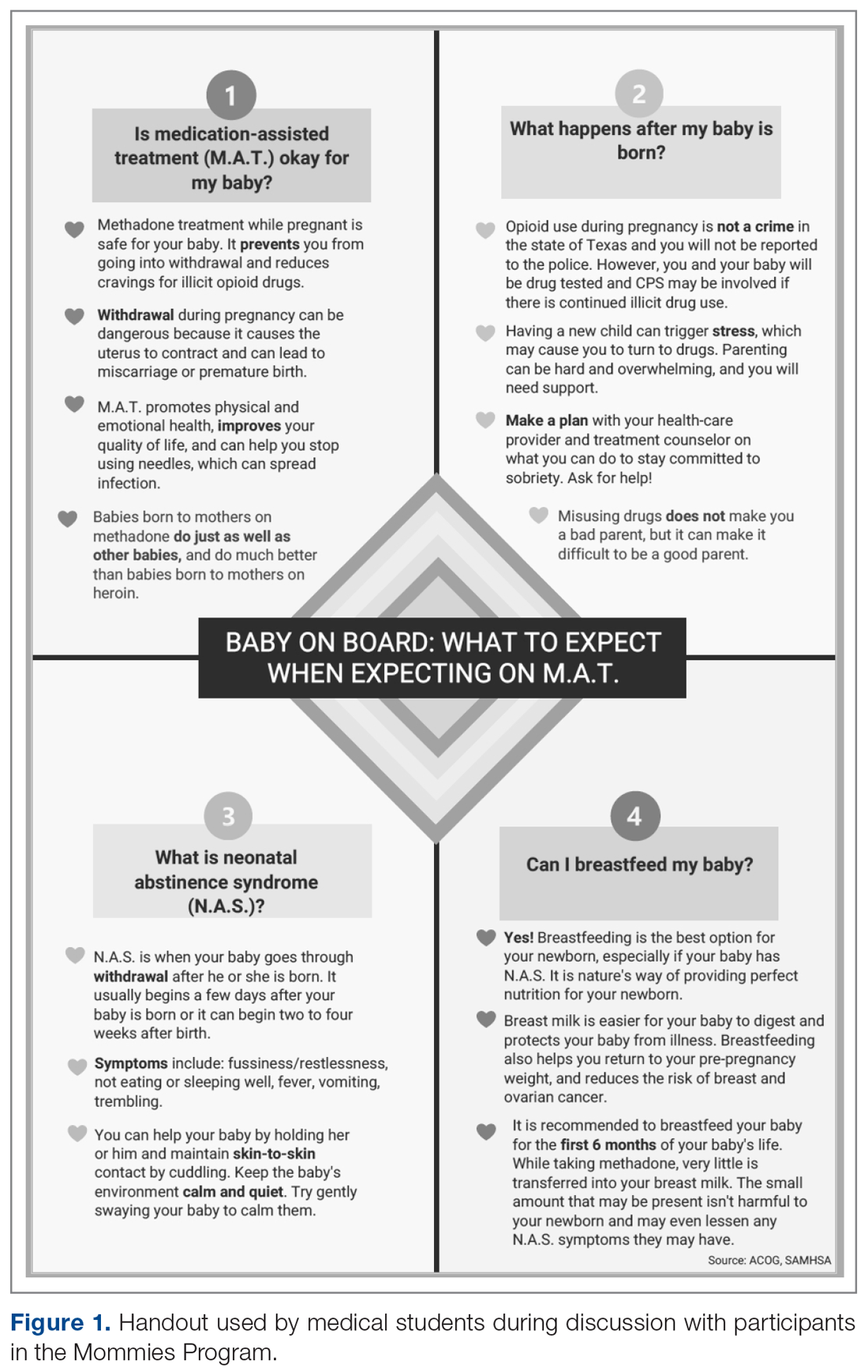

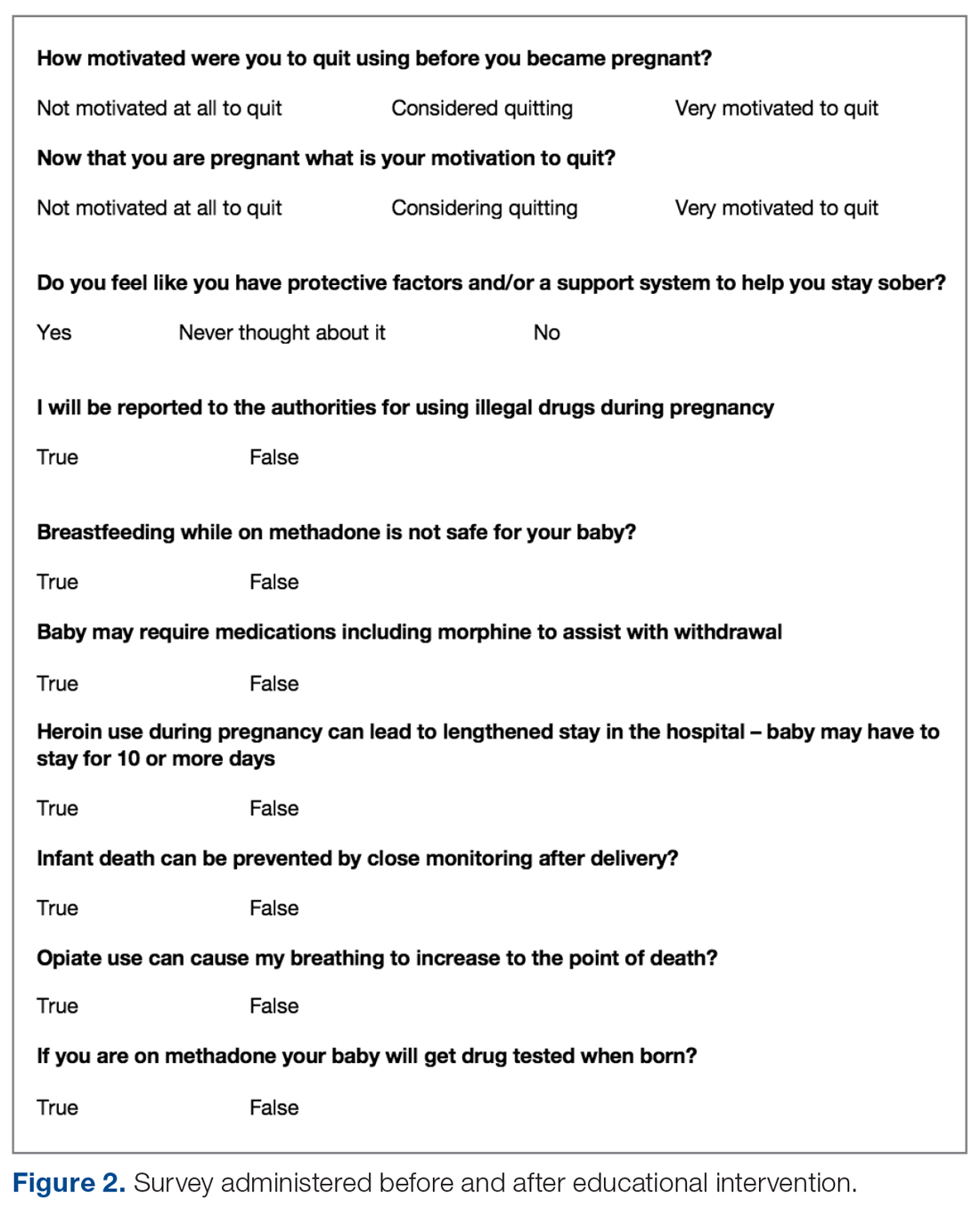

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the UT Health Long School of Medicine San Antonio, Texas.

Abstract

Objective: To educate pregnant patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) about the effects of opioids in order to improve understanding and help achieve sustained abstinence.

Methods: The Center for Health Care Services and University Hospital System (UHS) in San Antonio, TX, jointly o

Results: Of 68 women enrolled in the program, 33 completed both the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Nearly half (48%) were very motivated to quit before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. All participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety. Prior to the educational intervention, 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed on methadone, which improved to 97% in the post-survey, and 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health care providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so.

Conclusion: Pregnancy and education about opioids increased patients’ motivation to quit. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge and learned about patient-provider confidentiality. Our greatest challenge was participant follow-up; however, this improved with the help of a full-time Mommies Program nurse. Our future aim is to increase project awareness and extend the educational research.

Keywords: pregnancy; addiction; opioids; OUD; counseling.

In 2012 more than 259 million prescriptions for opioids were written in the United States, which was a 200% increase since 1998.1 Since the early 2000s, admissions to opioid substance abuse programs and the death rate from opioids have quadrupled.2-4 Specifically, the rate of heroin use increased more than 300% from 2010 to 2014.5 Opioid use in pregnancy has also escalated in recent years, with a 3- to 4-fold increase from 2000 to 2009 and with 4 in 1000 deliveries being complicated by opioid use disorder (OUD) in 2011.6-8

Between 2000 and 2014, the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased 24%, making it the only industrialized nation with a maternal mortality rate that is rising rather than falling.9 The Texas Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force found that between 2012 and 2015 drug overdose was the leading cause of maternal death in the period from delivery to 365 days postpartum, and it has increased dramatically since 2010.10,11

In addition, maternal mortality reviews in several states have identified substance use as a major risk factor for pregnancy-associated deaths.12,13 In Texas between 2012 and 2015, opioids were found in 58% of maternal drug overdoses.10 In 2007, 22.8% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid programs in 46 states filled an opioid prescription during pregnancy.14 Additionally, the rising prevalence of opioid use in pregnancy has led to a sharp increase in neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), rising from 1.5 cases per 1000 hospital births in 1999 to 6.0 per 1000 hospital births in 2013.15 Unsurprisingly, states with the highest rates of opioid prescribing also have the highest rates of NAS.16

Methadone combined with counseling and behavioral therapy has been the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in pregnancy since the 1970s. Methadone treatment prevents opioid withdrawal symptoms and increases adherence to prenatal care.17 One of the largest methadone treatment clinics in the San Antonio, TX, area is the Center for Health Care Services (CHCS). University Health System in San Antonio (UHS) has established a clinic called The Mommies Program, where mothers addicted to opioids can receive prenatal care by a dedicated physician, registered nurse, and a certified nurse midwife, who work in collaboration with the CHCS methadone clinic. Pregnant patients with OUD in pregnancy are concurrently enrolled in the Mommies Program and receive prenatal care through UHS and methadone treatment and counseling through CHCS. The continuity effort aims to increase prenatal care rates and adherence to methadone treatment.

Once mothers are off illicit opioids and on methadone, it is essential to discuss breastfeeding with them, as many mothers addicted to illicit opioids may have been told that they should not be breastfeeding. However, breastfeeding should be encouraged in women who are stable on methadone if they are not using illicit drugs and do not have other contraindications, regardless of maternal methadone dose, since the transfer of methadone into breast milk is minimal.18-20 Breastfeeding is beneficial in women taking methadone and has been associated with decreased severity of NAS symptoms, decreased need for pharmacotherapy, and a shorter hospital stay for the baby.21 In addition, breastfeeding contributes to the development of an attachment between mother and infant, while also providing the infant with natural immunity. Women should be counseled about the need to stop breastfeeding in the event of a relapse.22

Finally, the postpartum period represents a time of increased stressors, such as loss of sleep, child protective services involvement, and frustration with constant demands from new baby. For mothers with addiction, this is an especially sensitive time, as the stressors may be exacerbated by their new sobriety and a sudden end to the motivation they experienced from pregnancy.23 Therefore, early and frequent postpartum care with methadone dose evaluation is essential in order to decrease drug relapse and screen for postpartum depression in detail, since patients with a history of drug use are at increased risk of postpartum depression.

In 2017 medical students at UT Health Long School of Medicine in San Antonio created a project to educate women about OUD in pregnancy and provide motivational incentives for sustained abstinence; this project has continued each year since. Students provide education about methadone treatment and the dangers of using illicit opioids during and after pregnancy. Students especially focus on educating patients on the key problem areas in the literature, such as overdose, NAS, breastfeeding, postpartum substance use, and postpartum depression.

Methods

From October 2018 to February 2020, a total of 15 medical students volunteered between 1 and 20 times at the Mommies Program clinic, which was held once or twice per week from 8

The only inclusion criteria for participating in the educational intervention and survey was participants had to be 18 years of age or older and enrolled in the Mommies Program. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate completed a pre-survey administered by the students during the patient’s initial prenatal visit (Figure 2). This survey collected baseline information about the patient’s history with opioid use and their current knowledge of methadone treatment, NAS, legal aspects of drug use disclosure, and drug testing prior to the education portion of the encounter. After the pre-survey was administered, students spent 30 minutes reviewing the correct answers of the survey with the patients by utilizing the standardized handout to help patients understand details of methadone and opioid use in pregnancy (Figure 1). The post-survey was administered by a student once patients entered the third trimester to assess whether the education session increased patients’ knowledge of these topics.

At the time patients completed the post-survey, they received a Baby Bag as well as education regarding each item in the bag. The aim of distributing Baby Bags was to relieve some possible postnatal stressors and educate the patients about infant care. Items included in the bag were diapers, wipes, bottles, clothes, and swaddles. Prenatal vitamins were added in January 2020, as many patients struggle to afford vitamins if they are not currently covered by Medicaid or have other barriers. The Baby Bag items were purchased through a Community Service Learning grant through UT Health San Antonio.

Results

Of 68 women enrolled in the Mommies Program during the intervention period, 33 completed the pre-survey and the post-survey (48.5%). Even though all patients enrolled in the program met the inclusion criteria, patients were not included in the educational program for multiple reasons, including refusal to participate, poor clinic follow-up, or lack of students to collect surveys. However, all patients who completed the pre-survey did complete the post-survey. In the pre-survey, only 39% of participants knew it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone. In the post-survey, 97% knew it safe to breastfeed. Nearly half (48%) reported being very motivated to quit opioids before pregnancy, but 85% were very motivated to quit once pregnant. In the pre-survey, 76% incorrectly thought they would be reported to authorities by their health providers if they used illegal drugs during pregnancy, while in the post-survey, 100% knew they would not be reported for doing so. Also, all participants said learning more about the effects of opiates would increase motivation for sobriety.

Discussion

Questions assessed during the educational surveys revolved around patients’ knowledge of the intricacies, legally and physiologically, of methadone treatment for OUD, as well as beneficial aspects for patients and future child health, such as breastfeeding and motivation to quit and stay sober.

It was clear that there was a lack of knowledge and education about breastfeeding, as only 39% of the participants thought that it was safe to breastfeed while on methadone in the pre-survey; in the post survey, this improved to 97%. Students spent a large portion of the educational time going over the safety of breastfeeding for patients on methadone and the many benefits to mother and baby. Students also reviewed breastfeeding with patients every time patients came in for a visit and debunked any falsehoods about the negatives of breastfeeding while on methadone. This is another testament to the benefits of reinforcement around patient education.

The area of trust between provider and patient is essential in all provider-patient relationships. However, in the area of addiction, a trusting bond is especially important, as patients must feel confident and comfortable to disclose every aspect of their lives so the provider can give the best care. It was clear from our initial data that many patients did not feel this trust or understand the legal aspects regarding the provider-patient relationship in the terms of drug use, as the pre-survey shows 76% of patients originally thought they would be reported to authorities if they told their provider they used illegal drugs during pregnancy. This was an enormous issue in the clinic and something that needed to be addressed because, based on these data, we feared many patients would not be honest about using illegal drugs to supplement their methadone if they believed they would be reported to the authorities or even jailed. The medical student education team continually assured patients that their honesty about illegal drug use during pregnancy would not be revealed to the authorities, and also made it clear to patients that it was essential they were honest about illegal drug use so the optimal care could be provided by the team. These discussions were successful, as the post-survey showed that 100% of patients knew they would not be reported to the authorities if they used illegal drugs during the pregnancy. This showed an increase in knowledge, but also suggested an increase in confidence in the provider-patient relationship by patients, which we speculate allowed for a better patient experience, better patient outcomes, and less emotional stress for the patient and provider.

Last, we wanted to study and address the motivation to quit using drugs and stay sober through learning about the effects of opiates and how this motivation was related to pregnancy. A study by Mitchell et al makes clear that pregnancy is a motivation to seek treatment for drug use and to quit,24 and our survey data support these findings, with 48% of patients motivated to quit before they were pregnant and 85% motivated to quit once they knew they were pregnant. In addition, all patients attested on the pre- and post-survey that learning more about opioids would increase their motivation for sobriety. Therefore, we believe education about the use of opioids and other drugs is a strong motivation towards sobriety and should be further studied in methadone treatment and other drugs as well.

We will continue to focus on sobriety postpartum by using the education in pregnancy as a springboard to further postpartum education, as education seems to be very beneficial to future sobriety. In the future, we believe extending the educational program past pregnancy and discussing opioid use and addiction with patients at multiple follow-up visits will be beneficial to patients’ sobriety.

We faced 2 main challenges in implementing this intervention and survey: patients would often miss multiple appointments during their third trimester or would not attend their postpartum visit if they only had 1 prenatal visit; and many clinic sessions had low student attendance because students often had many other responsibilities in medical school and there were only 15 volunteers over the study time. These challenges decreased our post-survey completion rate. However, there has been improvement in follow-up as the project has continued. The Mommies Program now has a full-time registered nurse, and a larger number of medical student teachers have volunteered to attend the clinic. In the future, we aim to increase awareness of our project and the benefits of participation, expand advertising at our medical school to increase student participation, and increase follow-up education in the postpartum period.

Another future direction is to include local, free doula services, which are offered through Catholic Charities in San Antonio. Doulas provide antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum services, which we believe will help our patients through advocacy and support for sobriety during this emotional and stressful time.

Conclusion

Counseled participants were receptive to learning about the effects of OUD and methadone on themselves and their newborn. Participants unanimously stated that learning more about OUD increased their motivation for sobriety. It was also clear that the increased motivation to be sober during pregnancy, as compared to before pregnancy, is an opportunity to help these women take steps to get sober. Patients also advanced their breastfeeding knowledge, as we helped debunk falsehoods surrounding breastfeeding while on methadone, and we anticipate this will lead to greater breastfeeding rates for our patients on methadone, although this was not specifically studied. Finally, patients learned about patient-provider confidentiality, which allowed for more open and clear communication with patients so they could be cared for to the greatest degree and trust could remain paramount.

Drug use is a common problem in the health care system, and exposure to patients with addiction is important for medical students in training. We believe that attending the Mommies Program allowed medical students to gain exposure and skills to better help patients with OUD.

Corresponding author: Nicholas Stansbury, MD, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid painkiller prescribing: where you live makes a difference. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing. Accessed October 28, 2020.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4760, DAWN Series D-39. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2013. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154-63.

4. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug-poisoning deaths. NCHS Factsheet. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet-drug-poisoning-H.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. Bethesda (MD): NIDA; 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2016/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse. Accessed October 28, 2020.

6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2011 Contract No.: HHS Publication no. (SMA) 11–4658.

7. Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, et al. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:1158-1165.

8. Whiteman VE, Salemi JL, Mogos MF, et al. Maternal opioid drug use during pregnancy and its impact on perinatal morbidity, mortality, and the costs of medical care in the United States. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:1-8

9. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm#trends. Accessed February 4, 2020.

10. Macdorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:447-455.

11. Texas Health and Human Services. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report, September 2018. www.dshs.texas.gov/legislative/2018-Reports/MMMTFJointReport2018.pdf

12. Virginia Department of Health. Pregnancy-associated deaths from drug overdose in Virginia, 1999-2007: a report from the Virginia Maternal Mortality Review Team. Richmond, VA: VDH; 2015. www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/18/2016/04/Final-Pregnancy-Associated-Deaths-Due-to-Drug-Overdose.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

13. Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Maryland maternal mortality review 2016 annual report. Baltimore: DHMH; 2016. https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/Documents/Maryland-Maternal-Mortality-Review-2016-Report.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2020.

14. Desai RJ, Hernandez-Diaz S, Bateman BT, Huybrechts KF. Increase in prescription opioid use during pregnancy among Medicaid-enrolled women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:997-1002.

15. Reddy UM, Davis JM, Ren Z, et al. Opioid use in pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and childhood outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2017;72:703-705.

16. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35:650-655.

17. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction during pregnancy. In: Medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction in opioid treatment programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 43. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005:211-224.

18. Wojnar-Horton RE, Kristensen JH, Yapp P, et al. Methadone distribution and excretion into breast milk of clients in a methadone maintenance programme. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:543-547.

19. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10:135-141.

20. Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Committee on Drugs. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796-809.

21. Bagley SM, Wachman EM, Holland E, Brogly SB. Review of the assessment and management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:19.

22. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:488-489.

23. Gopman S. Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41:213-228.

24. Mitchell M, Severtson S, Latimer W. Pregnancy and race/ethnicity as predictors of motivation for drug treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:397-404.

‘Impressive’ results with neoadjuvant T-VEC in advanced melanoma

T-VEC is a modified virus that lyses tumor cells locally and induces a systemic immune response. In the phase 2 trial, neoadjuvant T-VEC plus surgery improved 3-year recurrence-free survival, when compared with immediate surgery, in patients with resectable melanoma.

“This is the first neoadjuvant trial for an approved oncolytic virus in melanoma and the largest randomized prospectively controlled neoadjuvant melanoma trial completed to date,” said investigator Reinhard Dummer, MD, of University Hospital Zürich.

The multicenter trial enrolled 150 patients with resectable stage IIIB–IV M1a melanoma (thereby including many with in-transit metastasis) who had at least one injectable lesion.

“This patient population is typically excluded from the trials that are published. Those trials typically focus on lymph node metastasis only,” Dr. Dummer noted.

The patients were randomized evenly to receive six doses over 12 weeks of intralesional T-VEC followed by surgical resection, or to the conventional approach of immediate surgical resection.

Survival results

The median follow-up for this interim analysis was 41.3 months.

The 3-year rate of recurrence-free survival, the trial’s primary endpoint, was 46.5% with T-VEC plus surgery and 31.0% with immediate surgery (hazard ratio, 0.67; P = .043). The median duration of recurrence-free survival was 27.5 months and 5.4 months, respectively.