User login

Replace routine preoperative testing with individualized risk assessment and indicated testing

CASE Patient questions need for preoperative tests

A healthy 42-year-old woman (G2P2) with abnormal uterine bleeding and a 2-cm endometrial polyp is scheduled for hysteroscopic polypectomy. After your preoperative clinic visit, the patient receives her paperwork containing information about preoperative lab work and diagnostic studies. You are asked to come into the room because she has further questions. When you arrive, the patient holds the papers out and asks, “Is all this blood work and a chest x-ray necessary? I thought I was healthy and this was a fairly simple surgery. Is there more I should be worried about?”

How would you respond?

The goal of preoperative testing is to determine which patients may be at an increased risk for experiencing an adverse perioperative event, taking into account both the inherent risks of the surgical procedure and the health of the individual patient. In the literature, the general consensus is that physicians rely too heavily on unnecessary laboratory and diagnostic testing during their preoperative assessment.1 More than 50% of patients who underwent preoperative evaluation had at least 1 unindicated test.2 These tests may result in a high frequency of abnormal findings, with less than 3% of abnormalities having clinical value or leading to a change in management.3

With health care costs accounting for almost 20% of the gross domestic product in the United States (totaling about $3.5 billion in 2017), performing unindicated preoperative testing contributes to the economic burden on health care systems, with an estimated cost of $3 to $18 million annually.4,5 In addition, unindicated tests can increase patient anxiety and necessitate follow-up testing, possibly exposing physicians to increased liability if abnormal results are not adequately investigated.6

It is time to rethink our use of routine preoperative testing.

Which tests to consider—or not: Evidence-based guidance

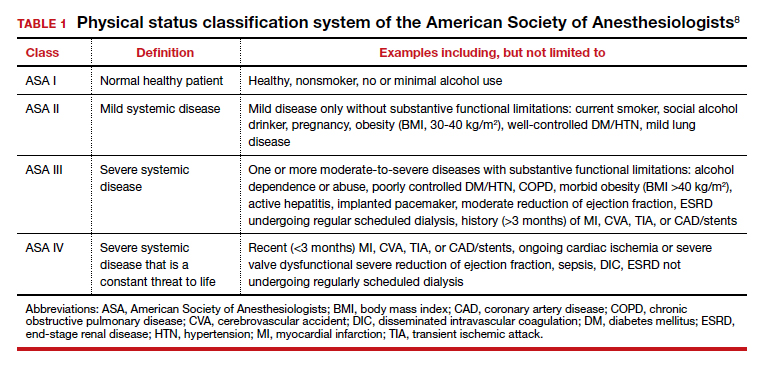

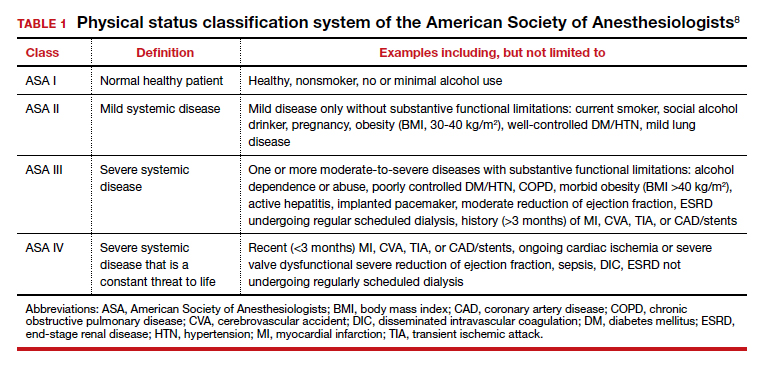

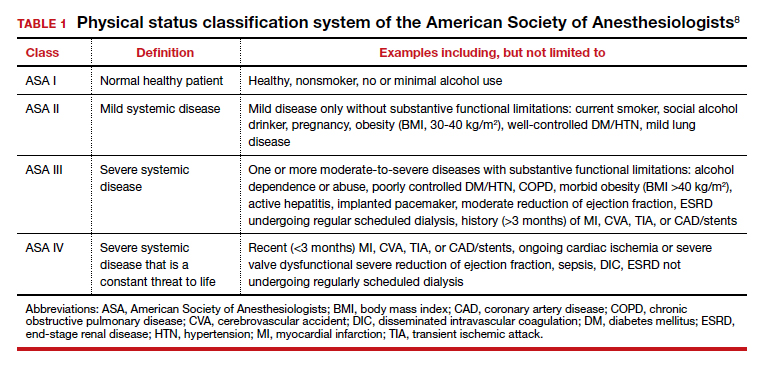

Professional societies, including the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, promote a move away from routine testing to avoid unnecessary visits and studies. In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published recommendations to guide preoperative testing.7 To stratify patients’ surgical risk according to their pre-existing health conditions, the ASA created a physical status classification system (TABLE 1).8

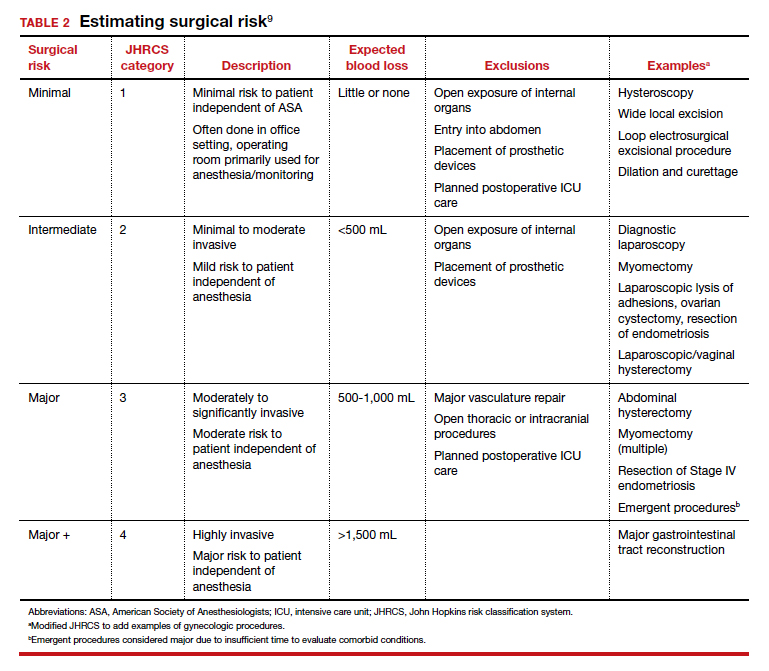

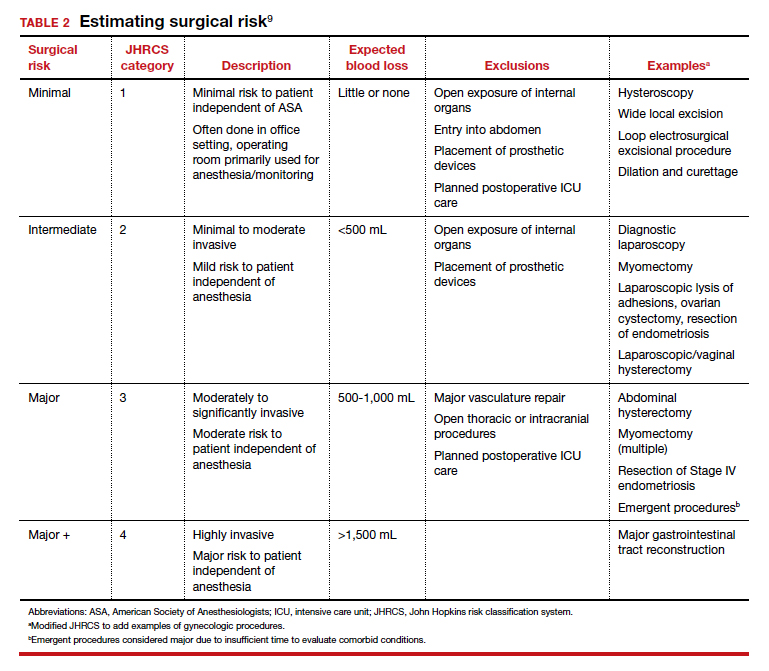

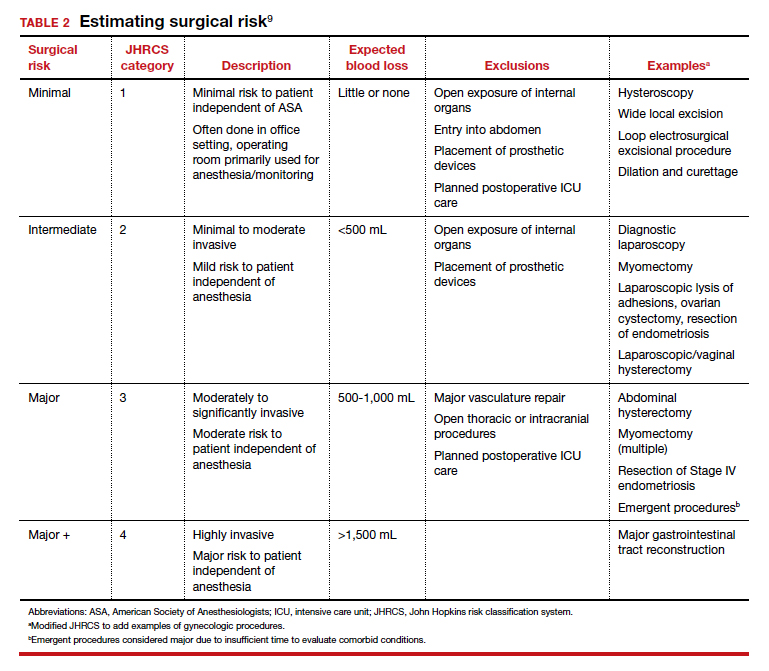

In addition to individual patient characteristics, some guidelines similarly stratify surgical procedures into minor, intermediate, and major risk. The modified Johns Hopkins surgical criteria allocates surgical risk based on expected blood loss, insensible loss, and the inherent risk of a procedure separate from anesthesia (TABLE 2).9 Despite these guidelines, physicians responsible for preoperative evaluations continue to order laboratory and diagnostic tests that are not indicated, often over concerns of case delays or cancellations.10,11

The following evidence-based recommendations provide guidance to gynecologists performing surgery for benign indications to determine which preoperative studies should be performed.

Serum chemistries

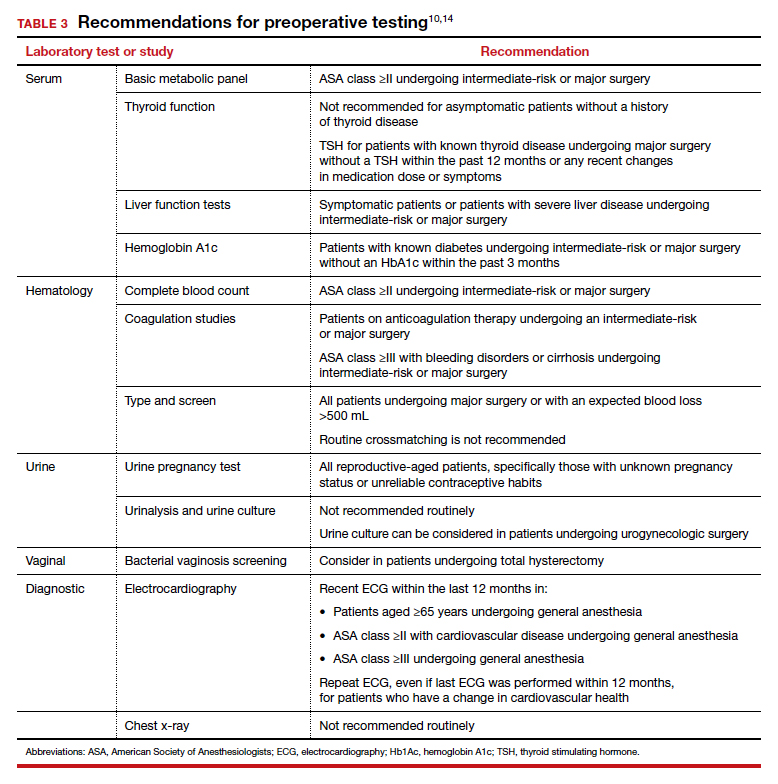

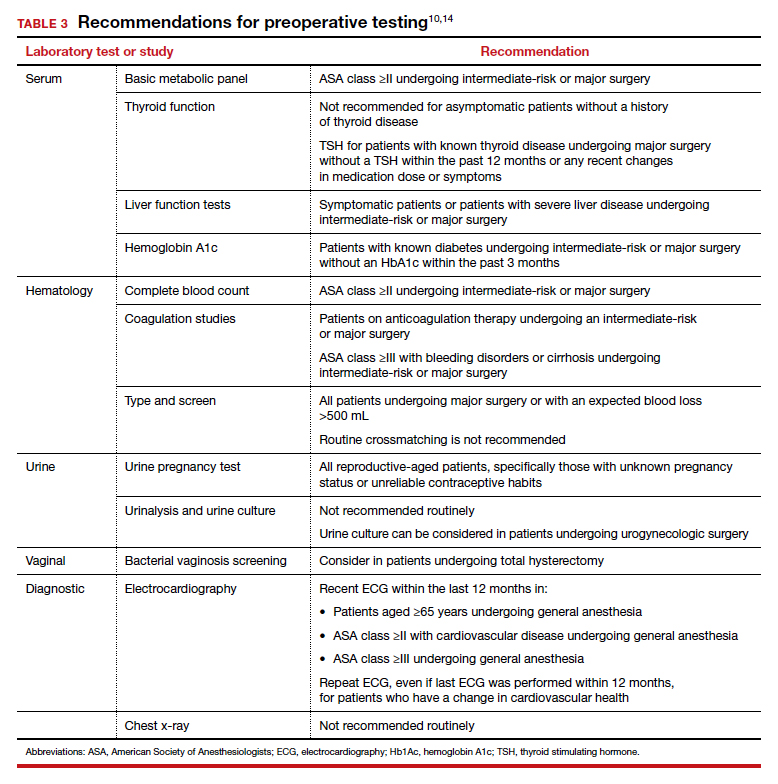

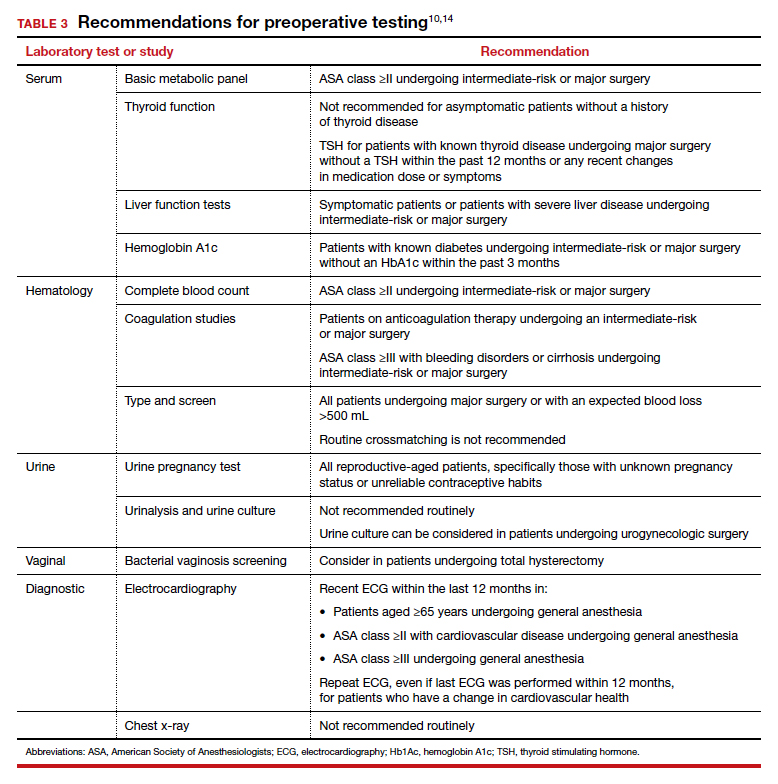

Basic metabolic panel (BMP). In both contemporary studies and earlier prospective studies, a preoperative BMP has a low likelihood of changing the surgical procedure or the patient’s management, especially in patients who are classified as ASA I and are undergoing minor- and intermediate-risk procedures.12,13 Therefore, we recommend a BMP for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Thyroid function. A basic tenet of preoperative evaluation is that asymptomatic patients should not be diagnosed according to lab values prior to surgical intervention. Therefore, we do not recommend routine preoperative thyroid function testing in patients without a history of thyroid disease.10 For patients with known thyroid disease, a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level should be evaluated prior to major surgery, or with any changes in medication dose or symptoms, within the past year.15

Liver function tests (LFTs). Routine screening of asymptomatic individuals without risk factors for liver disease is not recommended because there is a significantly lower incidence of abnormal lab values for LFTs than for other lab tests.16 We recommend LFTs only in symptomatic patients or patients diagnosed with severe liver disease undergoing intermediate-risk or major procedures.14

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Poorly controlled diabetes is a risk factor for poor wound healing, hospital readmission, prolonged hospitalization, and adverse events following surgery.17 We recommend that HbA1c levels be drawn only for patients with known diabetes undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery who do not have an available lab value within the past 3 months.14

Continue to: Hematologic studies...

Hematologic studies

Complete blood count (CBC). Many patients undergoing gynecologic procedures may have unreported or undiagnosed anemia secondary to abnormal uterine bleeding, which also may encompass heavy menstrual bleeding. With an abnormal CBC likely to affect preoperative management, assessment of preoperative hemoglobin levels is critical so that hemoglobin levels can be appropriately corrected before surgery. We therefore recommend obtaining a CBC for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.10,14

Coagulation studies. Preoperative coagulation studies are unlikely to uncover previously undiagnosed inherited coagulopathies, which are generally uncommon in the general population, and they do not predict operative bleeding when ordered unnecessarily.18,19 Therefore, we recommend preoperative coagulation studies only in patients 1) currently on anticoagulation therapy undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery or 2) in class ASA III or higher with bleeding disorders or cirrhosis undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Type and screen (T&S). Complicated algorithms have been proposed to determine when a preoperative T&S is necessary, but these may be impractical for busy gynecologists.20 We recommend a T&S within 72 hours, or on the day, of surgery for all patients undergoing major surgery, including hysterectomy, or with an anticipated blood loss of more than 500 mL; routine crossmatching of blood is not recommended.10,14

Urologic studies

Urine pregnancy test. Although the probability of a positive pregnancy test is likely very low, its occurrence frequently leads to the cancellation of surgery. We therefore recommend a preoperative urine pregnancy test, particularly in reproductive-aged patients with unknown pregnancy status or unreliable contraceptive habits.14 Preoperative urine pregnancy testing, even in patients who report sexual inactivity, ideally should be individualized and based on risk of fetal harm during or subsequent to surgery. Surgeries involving the uterus, or those involving possible teratogens like radiation, also should be considered when making recommendations for testing.

Urinalysis and urine culture. In asymptomatic patients undergoing general gynecologic procedures, a routine preoperative urinalysis and urine culture are of little value.18 However, among patients undergoing a urogynecologic surgical procedure, the risk of a postoperative urinary tract infection is higher than among patients undergoing a nonurogynecologic procedure.21,22 Therefore, we typically do not recommend routine preoperative urinalysis or urine culture, but a preoperative urine culture may be beneficial in patients undergoing urogynecologic surgery.14

Continue to: Diagnostic studies...

Diagnostic studies

Electrocardiography (ECG). The absolute difference in cardiovascular death is less than 1% among patients with and without ECG abnormalities undergoing a noncardiac procedure with minimal to moderate risk; therefore, routine ECG for low-risk patients should not be performed.23 Instead, ECG should be performed in patients with known coronary artery disease or structural heart disease and in patients aged 65 years and older, since age older than 65 years is an independent predictor of significant ECG abnormalities.24,25 We therefore recommend that the following individuals have an ECG within the last 12 months: patients aged 65 years and older, patients in class ASA II or higher with cardiovascular disease, and patients in class ASA III or higher undergoing general anesthesia. If there is a change in cardiovascular health since the most recent ECG—even if it was performed within 12 months—a repeat ECG is warranted.10,14

Chest x-ray. Despite a high rate of abnormalities seen on routine and indicated chest x-rays, there is no significant difference in perioperative pulmonary complications among patients with a normal or abnormal chest x-ray.16 Rather than changing surgical management, these abnormal results are more likely to lead to the cancellation or postponement of a surgical procedure.7 We therefore recommend against routine preoperative chest x-ray.14

The bottom line

Preoperative testing serves as an additional component of surgical planning. The fact is, however, that abnormal test results are common and frequently do not correlate with surgical outcomes.26 Instead, they can lead to unnecessary surgical procedure cancellations or postponements, undue anxiety in patients, increased liability among physicians, and rising health care costs.5-7

Rather than overly relying on routine laboratory or diagnostic studies, the history and physical examination should continue to be the cornerstone for surgeons responsible for assessing surgical risk. With individualized risk assessment, specific, indicated testing rather than routine nonspecific testing can be obtained.10,14 In short, low-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery are unlikely to benefit from preoperative ECG, chest x-ray, or routine laboratory testing without clinical indication. ●

- Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:100-108.

- Onuoha OC, Hatch M, Miano TA, et al. The incidence of un-indicated preoperative testing in a tertiary academic ambulatory center: a retrospective cohort study. Perioper Med. 2015; 4:14.

- Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, et al. The usefulness of preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA. 1985;253:3576-3581.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Table 42: Gross domestic product, national health expenditures, per capita amounts, percent distribution, and average annual percent change: United States, selected years 1960-2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ data/hus/2018/042.pdf. Accessed July 2020.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256:518-528.

- O’Neill F, Carter E, Pink N, et al. Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354: i3292.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:522-538.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. https://www.asahq.org/standardsand-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed July 2020.

- Pasternak LR, Johns A. Ambulatory gynaecological surgery: risk and assessment. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:663-679.

- Shields J, Lupo A, Walsh T, et al. Preoperative evaluation for gynecologic surgery: a guide to judicious, evidence-based testing. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:252-259.

- Sigmund AE, Stevens ER, Blitz JD, et al. Use of preoperative testing and physicians’ response to professional society guidance. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1352-1359.

- St Clair CM, Shah M, Diver EJ, et al. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for preoperative testing in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:694-700.

- De Sousa Soares D, Brandao RR, Mourao MR, et al. Relevance of routine testing in low-risk patients undergoing minor and medium surgical procedures. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63:197-201.

- Shields J, Kho KA. Preoperative evaluation for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what is the best evidence and recommendations for clinical practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:312-320.

- Palace MR. Perioperative management of thyroid dysfunction. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632916689677.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:7-40.

- Jehan F, Khan M, Sakran JV, et al. Perioperative glycemic control and postoperative complications in patients undergoing emergency general surgery: what is the role of plasma hemoglobin A1c? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:112-117.

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, et al. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:414-418.

- Rusk MH. Avoiding unnecessary preoperative testing. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100:1003-1008.

- Dexter F, Ledolter J, Davis E, et al. Systematic criteria for type and screen based on procedure’s probability of erythrocyte transfusion. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:768-778.

- Gehrich AP, Lustik MB, Mehr AA, et al. Risk of postoperative urinary tract infections following midurethral sling operations in women undergoing hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:483-490.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 195 summary: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:1177- 1179.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol, 2006;97: 1103-1106.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/ AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular examination and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2215-2245.

- Correll DJ, Hepner DL, Chang C, et al. Preoperative electrocardiograms: patient factors predictive of abnormalities. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1217-1122.

- Fritsch G, Flamm M, Hepner DL, et al. Abnormal preoperative tests, pathologic findings of medical history, and their predictive value for perioperative complications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:339-350.

CASE Patient questions need for preoperative tests

A healthy 42-year-old woman (G2P2) with abnormal uterine bleeding and a 2-cm endometrial polyp is scheduled for hysteroscopic polypectomy. After your preoperative clinic visit, the patient receives her paperwork containing information about preoperative lab work and diagnostic studies. You are asked to come into the room because she has further questions. When you arrive, the patient holds the papers out and asks, “Is all this blood work and a chest x-ray necessary? I thought I was healthy and this was a fairly simple surgery. Is there more I should be worried about?”

How would you respond?

The goal of preoperative testing is to determine which patients may be at an increased risk for experiencing an adverse perioperative event, taking into account both the inherent risks of the surgical procedure and the health of the individual patient. In the literature, the general consensus is that physicians rely too heavily on unnecessary laboratory and diagnostic testing during their preoperative assessment.1 More than 50% of patients who underwent preoperative evaluation had at least 1 unindicated test.2 These tests may result in a high frequency of abnormal findings, with less than 3% of abnormalities having clinical value or leading to a change in management.3

With health care costs accounting for almost 20% of the gross domestic product in the United States (totaling about $3.5 billion in 2017), performing unindicated preoperative testing contributes to the economic burden on health care systems, with an estimated cost of $3 to $18 million annually.4,5 In addition, unindicated tests can increase patient anxiety and necessitate follow-up testing, possibly exposing physicians to increased liability if abnormal results are not adequately investigated.6

It is time to rethink our use of routine preoperative testing.

Which tests to consider—or not: Evidence-based guidance

Professional societies, including the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, promote a move away from routine testing to avoid unnecessary visits and studies. In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published recommendations to guide preoperative testing.7 To stratify patients’ surgical risk according to their pre-existing health conditions, the ASA created a physical status classification system (TABLE 1).8

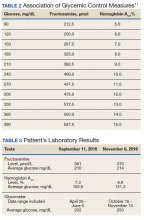

In addition to individual patient characteristics, some guidelines similarly stratify surgical procedures into minor, intermediate, and major risk. The modified Johns Hopkins surgical criteria allocates surgical risk based on expected blood loss, insensible loss, and the inherent risk of a procedure separate from anesthesia (TABLE 2).9 Despite these guidelines, physicians responsible for preoperative evaluations continue to order laboratory and diagnostic tests that are not indicated, often over concerns of case delays or cancellations.10,11

The following evidence-based recommendations provide guidance to gynecologists performing surgery for benign indications to determine which preoperative studies should be performed.

Serum chemistries

Basic metabolic panel (BMP). In both contemporary studies and earlier prospective studies, a preoperative BMP has a low likelihood of changing the surgical procedure or the patient’s management, especially in patients who are classified as ASA I and are undergoing minor- and intermediate-risk procedures.12,13 Therefore, we recommend a BMP for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Thyroid function. A basic tenet of preoperative evaluation is that asymptomatic patients should not be diagnosed according to lab values prior to surgical intervention. Therefore, we do not recommend routine preoperative thyroid function testing in patients without a history of thyroid disease.10 For patients with known thyroid disease, a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level should be evaluated prior to major surgery, or with any changes in medication dose or symptoms, within the past year.15

Liver function tests (LFTs). Routine screening of asymptomatic individuals without risk factors for liver disease is not recommended because there is a significantly lower incidence of abnormal lab values for LFTs than for other lab tests.16 We recommend LFTs only in symptomatic patients or patients diagnosed with severe liver disease undergoing intermediate-risk or major procedures.14

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Poorly controlled diabetes is a risk factor for poor wound healing, hospital readmission, prolonged hospitalization, and adverse events following surgery.17 We recommend that HbA1c levels be drawn only for patients with known diabetes undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery who do not have an available lab value within the past 3 months.14

Continue to: Hematologic studies...

Hematologic studies

Complete blood count (CBC). Many patients undergoing gynecologic procedures may have unreported or undiagnosed anemia secondary to abnormal uterine bleeding, which also may encompass heavy menstrual bleeding. With an abnormal CBC likely to affect preoperative management, assessment of preoperative hemoglobin levels is critical so that hemoglobin levels can be appropriately corrected before surgery. We therefore recommend obtaining a CBC for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.10,14

Coagulation studies. Preoperative coagulation studies are unlikely to uncover previously undiagnosed inherited coagulopathies, which are generally uncommon in the general population, and they do not predict operative bleeding when ordered unnecessarily.18,19 Therefore, we recommend preoperative coagulation studies only in patients 1) currently on anticoagulation therapy undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery or 2) in class ASA III or higher with bleeding disorders or cirrhosis undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Type and screen (T&S). Complicated algorithms have been proposed to determine when a preoperative T&S is necessary, but these may be impractical for busy gynecologists.20 We recommend a T&S within 72 hours, or on the day, of surgery for all patients undergoing major surgery, including hysterectomy, or with an anticipated blood loss of more than 500 mL; routine crossmatching of blood is not recommended.10,14

Urologic studies

Urine pregnancy test. Although the probability of a positive pregnancy test is likely very low, its occurrence frequently leads to the cancellation of surgery. We therefore recommend a preoperative urine pregnancy test, particularly in reproductive-aged patients with unknown pregnancy status or unreliable contraceptive habits.14 Preoperative urine pregnancy testing, even in patients who report sexual inactivity, ideally should be individualized and based on risk of fetal harm during or subsequent to surgery. Surgeries involving the uterus, or those involving possible teratogens like radiation, also should be considered when making recommendations for testing.

Urinalysis and urine culture. In asymptomatic patients undergoing general gynecologic procedures, a routine preoperative urinalysis and urine culture are of little value.18 However, among patients undergoing a urogynecologic surgical procedure, the risk of a postoperative urinary tract infection is higher than among patients undergoing a nonurogynecologic procedure.21,22 Therefore, we typically do not recommend routine preoperative urinalysis or urine culture, but a preoperative urine culture may be beneficial in patients undergoing urogynecologic surgery.14

Continue to: Diagnostic studies...

Diagnostic studies

Electrocardiography (ECG). The absolute difference in cardiovascular death is less than 1% among patients with and without ECG abnormalities undergoing a noncardiac procedure with minimal to moderate risk; therefore, routine ECG for low-risk patients should not be performed.23 Instead, ECG should be performed in patients with known coronary artery disease or structural heart disease and in patients aged 65 years and older, since age older than 65 years is an independent predictor of significant ECG abnormalities.24,25 We therefore recommend that the following individuals have an ECG within the last 12 months: patients aged 65 years and older, patients in class ASA II or higher with cardiovascular disease, and patients in class ASA III or higher undergoing general anesthesia. If there is a change in cardiovascular health since the most recent ECG—even if it was performed within 12 months—a repeat ECG is warranted.10,14

Chest x-ray. Despite a high rate of abnormalities seen on routine and indicated chest x-rays, there is no significant difference in perioperative pulmonary complications among patients with a normal or abnormal chest x-ray.16 Rather than changing surgical management, these abnormal results are more likely to lead to the cancellation or postponement of a surgical procedure.7 We therefore recommend against routine preoperative chest x-ray.14

The bottom line

Preoperative testing serves as an additional component of surgical planning. The fact is, however, that abnormal test results are common and frequently do not correlate with surgical outcomes.26 Instead, they can lead to unnecessary surgical procedure cancellations or postponements, undue anxiety in patients, increased liability among physicians, and rising health care costs.5-7

Rather than overly relying on routine laboratory or diagnostic studies, the history and physical examination should continue to be the cornerstone for surgeons responsible for assessing surgical risk. With individualized risk assessment, specific, indicated testing rather than routine nonspecific testing can be obtained.10,14 In short, low-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery are unlikely to benefit from preoperative ECG, chest x-ray, or routine laboratory testing without clinical indication. ●

CASE Patient questions need for preoperative tests

A healthy 42-year-old woman (G2P2) with abnormal uterine bleeding and a 2-cm endometrial polyp is scheduled for hysteroscopic polypectomy. After your preoperative clinic visit, the patient receives her paperwork containing information about preoperative lab work and diagnostic studies. You are asked to come into the room because she has further questions. When you arrive, the patient holds the papers out and asks, “Is all this blood work and a chest x-ray necessary? I thought I was healthy and this was a fairly simple surgery. Is there more I should be worried about?”

How would you respond?

The goal of preoperative testing is to determine which patients may be at an increased risk for experiencing an adverse perioperative event, taking into account both the inherent risks of the surgical procedure and the health of the individual patient. In the literature, the general consensus is that physicians rely too heavily on unnecessary laboratory and diagnostic testing during their preoperative assessment.1 More than 50% of patients who underwent preoperative evaluation had at least 1 unindicated test.2 These tests may result in a high frequency of abnormal findings, with less than 3% of abnormalities having clinical value or leading to a change in management.3

With health care costs accounting for almost 20% of the gross domestic product in the United States (totaling about $3.5 billion in 2017), performing unindicated preoperative testing contributes to the economic burden on health care systems, with an estimated cost of $3 to $18 million annually.4,5 In addition, unindicated tests can increase patient anxiety and necessitate follow-up testing, possibly exposing physicians to increased liability if abnormal results are not adequately investigated.6

It is time to rethink our use of routine preoperative testing.

Which tests to consider—or not: Evidence-based guidance

Professional societies, including the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely campaign, promote a move away from routine testing to avoid unnecessary visits and studies. In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) has published recommendations to guide preoperative testing.7 To stratify patients’ surgical risk according to their pre-existing health conditions, the ASA created a physical status classification system (TABLE 1).8

In addition to individual patient characteristics, some guidelines similarly stratify surgical procedures into minor, intermediate, and major risk. The modified Johns Hopkins surgical criteria allocates surgical risk based on expected blood loss, insensible loss, and the inherent risk of a procedure separate from anesthesia (TABLE 2).9 Despite these guidelines, physicians responsible for preoperative evaluations continue to order laboratory and diagnostic tests that are not indicated, often over concerns of case delays or cancellations.10,11

The following evidence-based recommendations provide guidance to gynecologists performing surgery for benign indications to determine which preoperative studies should be performed.

Serum chemistries

Basic metabolic panel (BMP). In both contemporary studies and earlier prospective studies, a preoperative BMP has a low likelihood of changing the surgical procedure or the patient’s management, especially in patients who are classified as ASA I and are undergoing minor- and intermediate-risk procedures.12,13 Therefore, we recommend a BMP for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Thyroid function. A basic tenet of preoperative evaluation is that asymptomatic patients should not be diagnosed according to lab values prior to surgical intervention. Therefore, we do not recommend routine preoperative thyroid function testing in patients without a history of thyroid disease.10 For patients with known thyroid disease, a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level should be evaluated prior to major surgery, or with any changes in medication dose or symptoms, within the past year.15

Liver function tests (LFTs). Routine screening of asymptomatic individuals without risk factors for liver disease is not recommended because there is a significantly lower incidence of abnormal lab values for LFTs than for other lab tests.16 We recommend LFTs only in symptomatic patients or patients diagnosed with severe liver disease undergoing intermediate-risk or major procedures.14

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Poorly controlled diabetes is a risk factor for poor wound healing, hospital readmission, prolonged hospitalization, and adverse events following surgery.17 We recommend that HbA1c levels be drawn only for patients with known diabetes undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery who do not have an available lab value within the past 3 months.14

Continue to: Hematologic studies...

Hematologic studies

Complete blood count (CBC). Many patients undergoing gynecologic procedures may have unreported or undiagnosed anemia secondary to abnormal uterine bleeding, which also may encompass heavy menstrual bleeding. With an abnormal CBC likely to affect preoperative management, assessment of preoperative hemoglobin levels is critical so that hemoglobin levels can be appropriately corrected before surgery. We therefore recommend obtaining a CBC for patients in class ASA II or higher who are undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.10,14

Coagulation studies. Preoperative coagulation studies are unlikely to uncover previously undiagnosed inherited coagulopathies, which are generally uncommon in the general population, and they do not predict operative bleeding when ordered unnecessarily.18,19 Therefore, we recommend preoperative coagulation studies only in patients 1) currently on anticoagulation therapy undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery or 2) in class ASA III or higher with bleeding disorders or cirrhosis undergoing intermediate-risk or major surgery.14

Type and screen (T&S). Complicated algorithms have been proposed to determine when a preoperative T&S is necessary, but these may be impractical for busy gynecologists.20 We recommend a T&S within 72 hours, or on the day, of surgery for all patients undergoing major surgery, including hysterectomy, or with an anticipated blood loss of more than 500 mL; routine crossmatching of blood is not recommended.10,14

Urologic studies

Urine pregnancy test. Although the probability of a positive pregnancy test is likely very low, its occurrence frequently leads to the cancellation of surgery. We therefore recommend a preoperative urine pregnancy test, particularly in reproductive-aged patients with unknown pregnancy status or unreliable contraceptive habits.14 Preoperative urine pregnancy testing, even in patients who report sexual inactivity, ideally should be individualized and based on risk of fetal harm during or subsequent to surgery. Surgeries involving the uterus, or those involving possible teratogens like radiation, also should be considered when making recommendations for testing.

Urinalysis and urine culture. In asymptomatic patients undergoing general gynecologic procedures, a routine preoperative urinalysis and urine culture are of little value.18 However, among patients undergoing a urogynecologic surgical procedure, the risk of a postoperative urinary tract infection is higher than among patients undergoing a nonurogynecologic procedure.21,22 Therefore, we typically do not recommend routine preoperative urinalysis or urine culture, but a preoperative urine culture may be beneficial in patients undergoing urogynecologic surgery.14

Continue to: Diagnostic studies...

Diagnostic studies

Electrocardiography (ECG). The absolute difference in cardiovascular death is less than 1% among patients with and without ECG abnormalities undergoing a noncardiac procedure with minimal to moderate risk; therefore, routine ECG for low-risk patients should not be performed.23 Instead, ECG should be performed in patients with known coronary artery disease or structural heart disease and in patients aged 65 years and older, since age older than 65 years is an independent predictor of significant ECG abnormalities.24,25 We therefore recommend that the following individuals have an ECG within the last 12 months: patients aged 65 years and older, patients in class ASA II or higher with cardiovascular disease, and patients in class ASA III or higher undergoing general anesthesia. If there is a change in cardiovascular health since the most recent ECG—even if it was performed within 12 months—a repeat ECG is warranted.10,14

Chest x-ray. Despite a high rate of abnormalities seen on routine and indicated chest x-rays, there is no significant difference in perioperative pulmonary complications among patients with a normal or abnormal chest x-ray.16 Rather than changing surgical management, these abnormal results are more likely to lead to the cancellation or postponement of a surgical procedure.7 We therefore recommend against routine preoperative chest x-ray.14

The bottom line

Preoperative testing serves as an additional component of surgical planning. The fact is, however, that abnormal test results are common and frequently do not correlate with surgical outcomes.26 Instead, they can lead to unnecessary surgical procedure cancellations or postponements, undue anxiety in patients, increased liability among physicians, and rising health care costs.5-7

Rather than overly relying on routine laboratory or diagnostic studies, the history and physical examination should continue to be the cornerstone for surgeons responsible for assessing surgical risk. With individualized risk assessment, specific, indicated testing rather than routine nonspecific testing can be obtained.10,14 In short, low-risk patients undergoing noncardiac surgery are unlikely to benefit from preoperative ECG, chest x-ray, or routine laboratory testing without clinical indication. ●

- Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:100-108.

- Onuoha OC, Hatch M, Miano TA, et al. The incidence of un-indicated preoperative testing in a tertiary academic ambulatory center: a retrospective cohort study. Perioper Med. 2015; 4:14.

- Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, et al. The usefulness of preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA. 1985;253:3576-3581.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Table 42: Gross domestic product, national health expenditures, per capita amounts, percent distribution, and average annual percent change: United States, selected years 1960-2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ data/hus/2018/042.pdf. Accessed July 2020.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256:518-528.

- O’Neill F, Carter E, Pink N, et al. Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354: i3292.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:522-538.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. https://www.asahq.org/standardsand-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed July 2020.

- Pasternak LR, Johns A. Ambulatory gynaecological surgery: risk and assessment. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:663-679.

- Shields J, Lupo A, Walsh T, et al. Preoperative evaluation for gynecologic surgery: a guide to judicious, evidence-based testing. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:252-259.

- Sigmund AE, Stevens ER, Blitz JD, et al. Use of preoperative testing and physicians’ response to professional society guidance. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1352-1359.

- St Clair CM, Shah M, Diver EJ, et al. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for preoperative testing in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:694-700.

- De Sousa Soares D, Brandao RR, Mourao MR, et al. Relevance of routine testing in low-risk patients undergoing minor and medium surgical procedures. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63:197-201.

- Shields J, Kho KA. Preoperative evaluation for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what is the best evidence and recommendations for clinical practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:312-320.

- Palace MR. Perioperative management of thyroid dysfunction. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632916689677.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:7-40.

- Jehan F, Khan M, Sakran JV, et al. Perioperative glycemic control and postoperative complications in patients undergoing emergency general surgery: what is the role of plasma hemoglobin A1c? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:112-117.

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, et al. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:414-418.

- Rusk MH. Avoiding unnecessary preoperative testing. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100:1003-1008.

- Dexter F, Ledolter J, Davis E, et al. Systematic criteria for type and screen based on procedure’s probability of erythrocyte transfusion. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:768-778.

- Gehrich AP, Lustik MB, Mehr AA, et al. Risk of postoperative urinary tract infections following midurethral sling operations in women undergoing hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:483-490.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 195 summary: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:1177- 1179.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol, 2006;97: 1103-1106.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/ AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular examination and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2215-2245.

- Correll DJ, Hepner DL, Chang C, et al. Preoperative electrocardiograms: patient factors predictive of abnormalities. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1217-1122.

- Fritsch G, Flamm M, Hepner DL, et al. Abnormal preoperative tests, pathologic findings of medical history, and their predictive value for perioperative complications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:339-350.

- Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:100-108.

- Onuoha OC, Hatch M, Miano TA, et al. The incidence of un-indicated preoperative testing in a tertiary academic ambulatory center: a retrospective cohort study. Perioper Med. 2015; 4:14.

- Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, et al. The usefulness of preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA. 1985;253:3576-3581.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. Table 42: Gross domestic product, national health expenditures, per capita amounts, percent distribution, and average annual percent change: United States, selected years 1960-2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ data/hus/2018/042.pdf. Accessed July 2020.

- Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256:518-528.

- O’Neill F, Carter E, Pink N, et al. Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;354: i3292.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:522-538.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. ASA physical status classification system. https://www.asahq.org/standardsand-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed July 2020.

- Pasternak LR, Johns A. Ambulatory gynaecological surgery: risk and assessment. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;19:663-679.

- Shields J, Lupo A, Walsh T, et al. Preoperative evaluation for gynecologic surgery: a guide to judicious, evidence-based testing. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:252-259.

- Sigmund AE, Stevens ER, Blitz JD, et al. Use of preoperative testing and physicians’ response to professional society guidance. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1352-1359.

- St Clair CM, Shah M, Diver EJ, et al. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines for preoperative testing in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:694-700.

- De Sousa Soares D, Brandao RR, Mourao MR, et al. Relevance of routine testing in low-risk patients undergoing minor and medium surgical procedures. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63:197-201.

- Shields J, Kho KA. Preoperative evaluation for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery: what is the best evidence and recommendations for clinical practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26:312-320.

- Palace MR. Perioperative management of thyroid dysfunction. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1178632916689677.

- Smetana GW, Macpherson DS. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:7-40.

- Jehan F, Khan M, Sakran JV, et al. Perioperative glycemic control and postoperative complications in patients undergoing emergency general surgery: what is the role of plasma hemoglobin A1c? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84:112-117.

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, et al. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:414-418.

- Rusk MH. Avoiding unnecessary preoperative testing. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100:1003-1008.

- Dexter F, Ledolter J, Davis E, et al. Systematic criteria for type and screen based on procedure’s probability of erythrocyte transfusion. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:768-778.

- Gehrich AP, Lustik MB, Mehr AA, et al. Risk of postoperative urinary tract infections following midurethral sling operations in women undergoing hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:483-490.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin No. 195 summary: prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:1177- 1179.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol, 2006;97: 1103-1106.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/ AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular examination and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2215-2245.

- Correll DJ, Hepner DL, Chang C, et al. Preoperative electrocardiograms: patient factors predictive of abnormalities. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1217-1122.

- Fritsch G, Flamm M, Hepner DL, et al. Abnormal preoperative tests, pathologic findings of medical history, and their predictive value for perioperative complications. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:339-350.

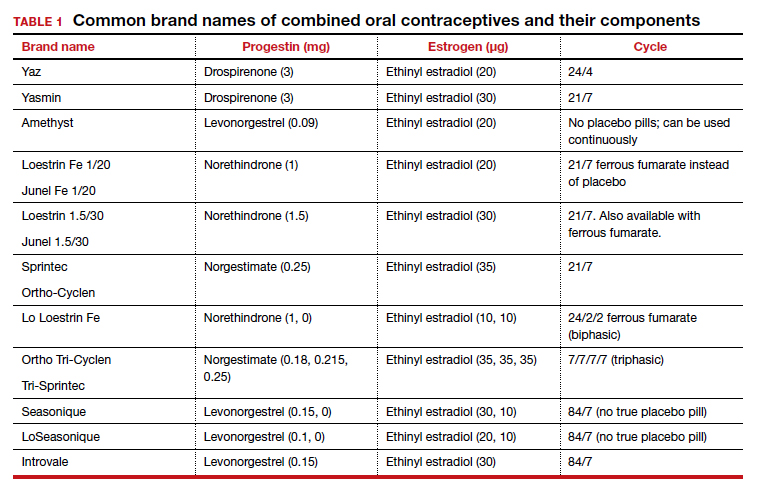

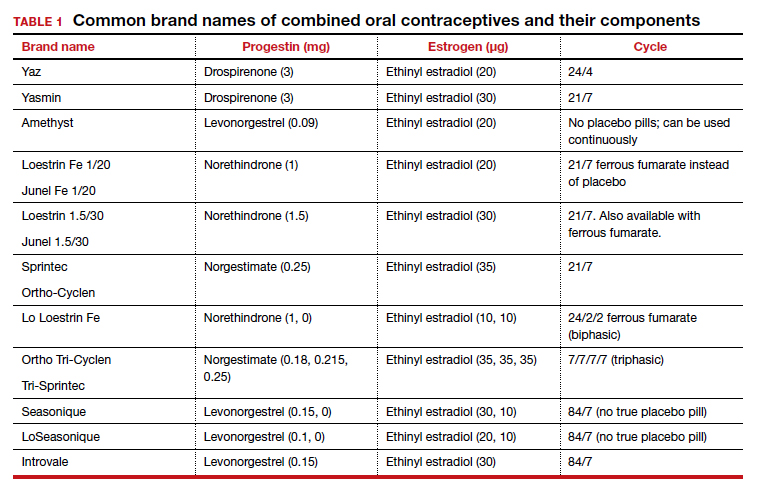

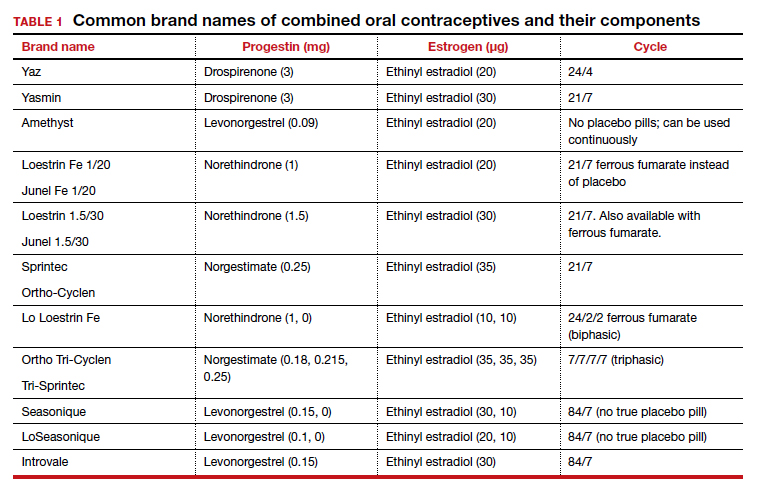

The pill toolbox: How to choose a combined oral contraceptive

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.

Another common concern is that COCs cause mood changes. A 2016 review by Schaffir and colleagues sheds some light on this topic,3 albeit limited by the paucity of prospective studies. This review identified only 1 randomized controlled trial comparing depression incidence among women initiating a COC versus a placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of depression among the groups at 3 months. Among 4 large retrospective studies of women using COCs, the agents either had no or a beneficial effect on mood. Schaffir’s review reports that there may be greater mood adverse effects with COCs among women with underlying mood disorders.

Patients may worry that COC use will permanently impair their fertility or delay return to fertility after discontinuation. Research does indicate that return of fertility after stopping COCs often takes several months (compared with immediate fertility after discontinuing a barrier method). However, there still seem to be comparable conception rates within 12 months after discontinuing COCs as there are after discontinuing other common nonhormonal or hormonal contraceptive methods. Fertility is not impacted by the duration of COC use. In addition, return to fertility seems to be comparable after discontinuation of extended cycle or continuous COCs compared with traditional-cycle COCs.4

COC safety

Known major risks of COCs include venous thromboembolism (VTE). The risk of VTE is about double among COC users than among nonpregnant nonusers: 3–9 per 10,000 woman-years compared with 1–5.5 In a study by the US Food and Drug Administration, drospirenone-containing COCs had double the risk of VTE than other COCs. However, the position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on this increased risk of VTE with drospirenone-containing pills is that it is “possible” and “minimal.”5 It is important to remember that an alternative to COC use is pregnancy, in which the VTE risk is about double that among COC users, at 5–20 per 10,000 woman-years. This risk increases further in the postpartum period, to 40–65 per 10,000 woman-years.5

Another known major risk of COCs is arterial embolic disease, including cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarctions. Women at increased risk for these complications include those with hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity and women who are aged 35 or older and smoke. Interestingly, women with migraines with aura are at increased risk for stroke but not for myocardial infarction. These women increase their risk of stroke 2- to 4-fold if they use COCs.

Continue to: Different pills for different problems...

Different pills for different problems

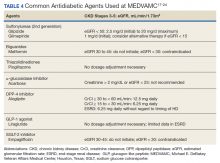

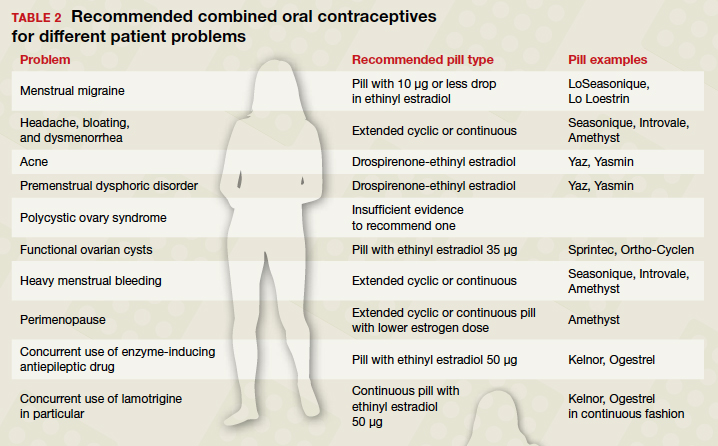

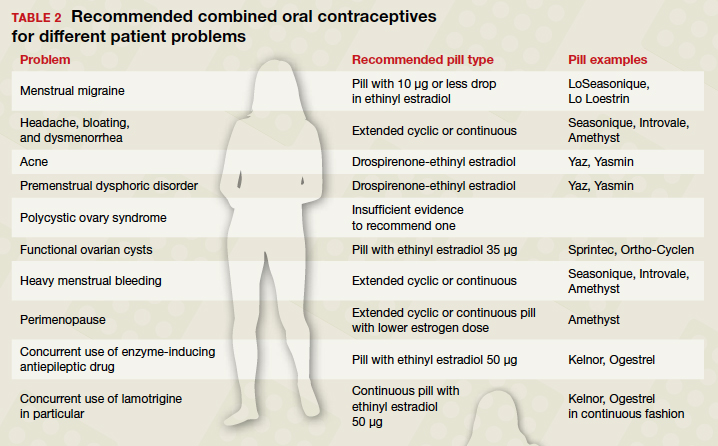

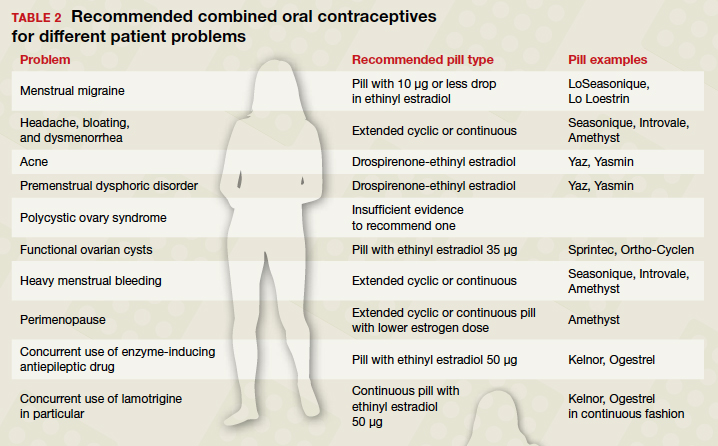

With so many pills on the market, it is important for clinicians to know how to choose a particular pill for a particular patient. The following discussion assumes that the patient in question desires a COC for contraception, then offers guidance on how to choose a pill with patient-specific noncontraceptive benefits (TABLE 2).

When HMB is a concern. Patients with heavy menstrual bleeding may experience fewer bleeding and/or spotting days with extended cyclic or continuous use of a COC rather than with traditional cyclic use.6 Examples of such COC options include:

- Introvale and Seasonique, both extended-cycle formulations

- Amethyst, which is formulated without placebo pills so that it can be used continuously

- any other COC prescribed with instructions for the patient to skip placebo pills.

An extrapolated benefit to extended-cycle or continuous COCs use for heavy menstrual bleeding is addressing anemia.

For premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the only randomized controlled trials showing improvement involve drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol pills (Yaz and Yasmin).7 There is also evidence that extended cyclic or continuous use of these formulations is more impactful for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than a traditional cycle.8

Keeping migraine avoidance and prevention in mind. Various studies have looked at the impact of different COC formulations on menstrual-related symptoms. There is evidence of greater improvement in headache, bloating, and dysmenorrhea with extended cyclic or continuous use compared with traditional cyclic use.6

In terms of headache, let us delve into menstrual migraine in particular. Menstrual migraines occur sometime between 2 days prior to 2 days after the first day of menses and are linked to a sharp drop in estrogen levels. COCs are contraindicated in women with menstrual migraines with aura because of the increased stroke risk. For women with menstrual migraines without aura, COCs can prevent migraines. Prevention depends on minimizing fluctuations in estrogen levels; any change in estrogen level greater than 10 µg of ethinyl estradiol may trigger an estrogen-related migraine. All currently available regimens of COCs that comprise 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo involve a drop of more than 10 µg. Options that involve a drop of 10 µg or less include any continuous formulation, the extended formulation LoSeasonique (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg and ethinyl estradiol 20 µg for 84 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 7 days), and Lo Loestrin (ethinyl estradiol 10 µg and norethindrone 1 mg for 24 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 2 days, then placebo for 2 days).9

What’s best for acne-prone patients? All COCs should improve acne by increasing levels of sex hormone binding globulin. However, some comparative studies have shown drospirenone-containing COCs to be the most effective for acne. This finding makes sense in light of studies demonstrating antiandrogenic effects of drospirenone.10

Managing PCOS symptoms. It seems logical, by extension, that drospirenone-containing COCs would be particularly beneficial for treating hirsutism associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Other low‒androgenic-potential progestins, such as a third-generation progestin (norgestimate or desogestrel), might similarly be hypothesized to be advantageous. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any one COC formulation over another for the indication of PCOS.11

Ovarian cysts: Can COCs be helpful? COCs are commonly prescribed by gynecologists for patients with functional ovarian cysts. It is important to note that COCs have not been found to hasten the resolution of existing cysts, so they should not be used for this purpose.12 Studies of early COCs, which had high doses of estrogen (on the order of 50 µg), showed lower rates of cysts among users. This effect seems to be attenuated with the lower-estrogen-dose pills that are currently available, but there still appears to be benefit. Therefore, for a patient prone to cysts who desires an oral contraceptive, a COC containing estrogen 35 µg is likely to be the most beneficial of COCs currently on the market.13,14

Lower-dosage COCs in perimenopause may be beneficial. COCs can ameliorate perimenopausal symptoms including abnormal uterine bleeding and vasomotor symptoms. Clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe COCs for perimenopausal women because of increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer with increasing age. However, age alone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method. An extended cyclic or continuous regimen COC may be the best choice for a perimenopausal woman in order to avoid vasomotor symptoms that occur during hormone-free intervals. In addition, given the increasing risk of adverse effects like VTE with estrogen dose, a lower estrogen formulation is advisable.15

Patients with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are a special population when it comes to COCs. Certain AEDs induce hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism and protein binding of COCs, which can result in contraceptive failure. Strong inducers are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Weak inducers are clobazam, eslicarbazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and topiramate. Women taking any of the above AEDs are recommended to choose a different form of contraception than a COC. However, if they are limited to COCs for some reason, a preparation containing estrogen 50 µg is recommended. It is speculated that the efficacy and adverse effects of COCs with increased hormone doses, used in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs, should be comparable to those with standard doses when not combined with AEDs; however, this speculation is unproven.16 There are few COCs on the market with estrogen doses of 50 µg, but a couple of examples are Kelnor and Ogestrel.

Additional factors have to be considered with concurrent COC use with the AED lamotrigine since COCs increase clearance of this agent. Therefore, patients taking lamotrigine who start COCs will need an increase in lamotrigine dose. To avoid fluctuations in lamotrigine serum levels, use of a continuous COC is recommended.17

Continue to: Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks...

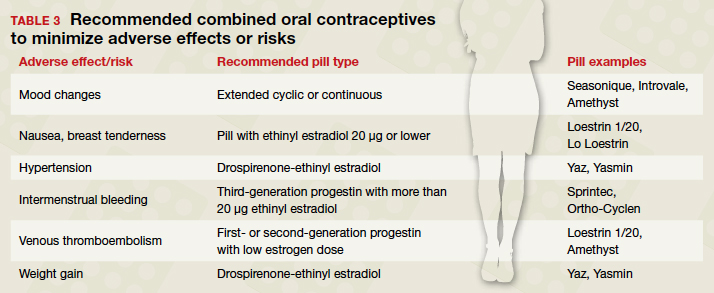

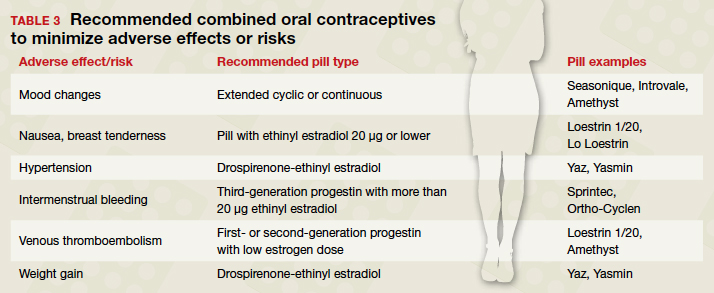

Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks

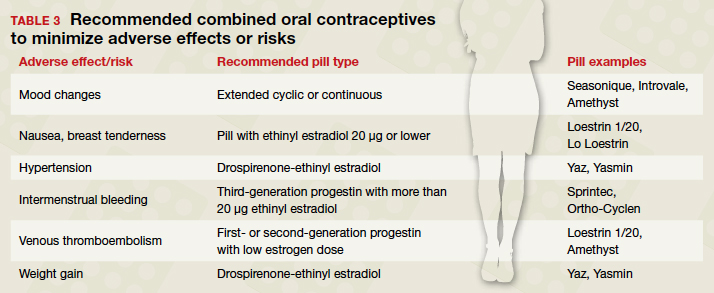

For women who desire to use a COC for contraception but who are at risk for a particular complication or are bothered by a particular adverse effect, ObGyns can optimize the choice of pill (TABLE 3). For example, women who have adverse effects of nausea and/or breast tenderness may benefit from reducing the estrogen dose to 20 µg or lower.18

Considering VTE

As discussed previously, VTE is a risk with all COCs, but some pills confer greater risk than others. For one, VTE risk increases with estrogen dose. In addition, VTE risk depends on the type of progestin. Drospirenone and third-generation progestins (norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel) confer a higher risk of VTE than first- or second-generation progestins. For example, a pill with estradiol 30 µg and either a third-generation progestin or drospirenone has a 50% to 80% higher risk of VTE compared with a pill with estradiol 30 µg and levonorgestrel.

For patients at particularly high risk for VTE, COCs are contraindicated. For patients for whom COCs are considered medically appropriate but who are at higher risk (eg, obese women), it is wise to use a pill containing a first-generation (norethindrone) or second-generation progestin (levonorgestrel) combined with the lowest dose of estrogen that has tolerable adverse effects.19

What about hypertension concerns?

Let us turn our attention briefly to hypertension and its relation to COC use. While the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association redefined hypertension in 2017 using a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers hypertension to be 140/90 mm Hg in terms of safety of using COCs. ACOG states, “women with blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg may use any hormonal contraceptive method.”20 In women with hypertension in the range of 140‒159 mm Hg systolic or 90‒99 mm Hg diastolic, COCs are category 3 according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits. For women with blood pressures of 160/110 mm Hg or greater, COCs are category 4 (contraindicated). If a woman with mild hypertension is started on a COC, a drospirenone-containing pill may be the best choice because of its diuretic effects. While other contemporary COCs have been associated with a mild increase in blood pressure, drospirenone-containing pills have not shown this association.21

Continue to: At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain...

At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain

For women bothered by intermenstrual bleeding, use of a COC with a third-generation progestin may be preferable to use of one with a first- or second-generation. It may be because of decreased abnormal bleeding that COCs with third-generation progestins have lower discontinuation rates.22 In addition, COCs containing estrogen 20 µg or less are associated with more intermenstrual bleeding than those with more than 20 µg estrogen.23 Keep in mind that it is common with any COC to have intermenstrual bleeding for the first several months.

For women with pre-existing mood disorders or who report mood changes with COCs, it appears that fluctuations in hormone levels are problematic. Consistently, there is evidence that monophasic pills are preferable to multiphasic and that extended cyclic or continuous use is preferable to traditional cyclic use for mitigating mood adverse effects. There is mixed evidence on whether a low dose of ethinyl estradiol is better for mood.3

Although it is discussed above that randomized controlled trials have not shown an association between COC use and weight gain, many women remain concerned. For these women, a drospirenone-containing COC may be the best choice. Drospirenone has antimineralocorticoid activity, so it may help prevent water retention.

A brief word about multiphasic COCs. While these pills were designed to mimic physiologic hormone fluctuations and minimize hormonal adverse effects, there is insufficient evidence to compare their effects to those of monophasic pills.24 Without such evidence, there is little reason to recommend a multiphasic pill to a patient over the more straightforward monophasic formulation.

Conclusion

There are more nuances to prescribing an optimal COC for a patient than may initially come to mind. It is useful to remember that any formulation of pill may be prescribed in an extended or continuous fashion, and there are benefits for such use for premenstrual dysphoric disorder, heavy menstrual bleeding, perimenopause, and menstrual symptoms. Although there are numerous brands of COCs available, a small cadre will suffice for almost all purposes. Such a “toolbox” of pills could include a pill formatted for continuous use (Seasonique), a low estrogen pill (Loestrin), a drospirenone-containing pill (Yaz), and a pill containing a third-generation progestin and a higher dose of estrogen (Sprintec). ●

- Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-49: United States, 2015-2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 327. Hyattsville, MD; 2018.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Schaffir J, Worly BL, Gur TL. Combined hormonal contraception and its effects on mood: a critical review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:347-355.

- Barnhart KT, Schreiber CA. Return to fertility following discontinuation of oral contraceptives. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:659-663.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #540: Risk of Venous Thromboembolism Among Users of Drospirenone-Containing Oral Contraceptive Pills. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1239-1242.

- Edelman A, Micks E, Gallo MF, et al. Continuous or extended cycle vs. cyclic use of combined hormonal contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD004695.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #110: Noncontraceptive Uses of Hormonal Contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2010:206-218.

- Coffee AL, Kuehl TJ, Willis S, et al. Oral contraceptives and premenstrual symptoms: comparison of a 21/7 and extended regimen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1311-1319.

- Calhoun AH, Batur P. Combined hormonal contraceptives and migraine: an update on the evidence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:631-638.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- McCartney CR, Marshall JC. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:54-64.

- Grimes DA, Jones LB, Lopez LM, et al. Oral contraceptives for functional ovarian cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD006134.

- Grimes DA, Godwin AJ, Rubin A, et al. Ovulation and follicular development associated with three low-dose oral contraceptives: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:29-34.

- Christensen JT, Boldsen JL, Westergaard JG. Functional ovarian cysts in premenopausal and gynecologically healthy women. Contraception. 2002;66:153-157.

- Hardman SM, Gebbie AE. Hormonal contraceptive regimens in the perimenopause. Maturitas. 2009;63:204-212.

- Zupanc ML. Antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives in adolescent women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2006;66 (6 suppl 3):S37-S45.

- Wegner I, Edelbroek PM, Bulk S, et al. Lamotrigine kinetics within the menstrual cycle, after menopause, and with oral contraceptives. Neurology. 2009;73:1388-1393.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Australian Prescriber. 2015;38:6-11.

- de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010813.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin #206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150.

- de Morais TL, Giribela C, Nisenbaum MG, et al. Effects of a contraceptive containing drospirenone and ethinylestradiol on blood pressure, metabolic profile and neurohumoral axis in hypertensive women at reproductive age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:113-117.

- Lawrie TA, Helmerhorst FM, Maitra NK, et al. Types of progestogens in combined oral contraception: effectiveness and side-effects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004861.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 µg versus >20 µg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003553

In the era of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), the pill can seem obsolete. However, it is still the second most commonly used birth control method in the United States, chosen by 19% of female contraceptive users as of 2015–2017.1 It also has noncontraceptive benefits, so it is important that obstetrician-gynecologists are well-versed in its uses. In this article, I will focus on combined oral contraceptives (COCs; TABLE 1), reviewing the major risks, benefits, and adverse effects of COCs before focusing on recommendations for particular formulations of COCs for various patient populations.

Benefits and risks

There are numerous noncontraceptive benefits of COCs, including menstrual cycle regulation; reduced risk of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancer; and treatment of menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, acne, menstrual migraine, premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, pelvic pain due to endometriosis, and hirsutism.

Common patient concerns

In terms of adverse effects, there are more potential unwanted effects of concern to women than there are ones validated in the literature. Accepted adverse effects include nausea, breast tenderness, and decreased libido. However, one of the most common concerns voiced during contraceptive counseling is that COCs will cause weight gain. A 2014 Cochrane review identified 49 trials studying the weight gain question.2 Of those, only 4 had a placebo or nonintervention group. Of these 4, there was no significant difference in weight change between the COC-receiving group and the control group. When patients bring up their concerns, it may help to remind them that women tend to gain weight over time whether or not they are taking a COC.

Another common concern is that COCs cause mood changes. A 2016 review by Schaffir and colleagues sheds some light on this topic,3 albeit limited by the paucity of prospective studies. This review identified only 1 randomized controlled trial comparing depression incidence among women initiating a COC versus a placebo. There was no difference in the incidence of depression among the groups at 3 months. Among 4 large retrospective studies of women using COCs, the agents either had no or a beneficial effect on mood. Schaffir’s review reports that there may be greater mood adverse effects with COCs among women with underlying mood disorders.

Patients may worry that COC use will permanently impair their fertility or delay return to fertility after discontinuation. Research does indicate that return of fertility after stopping COCs often takes several months (compared with immediate fertility after discontinuing a barrier method). However, there still seem to be comparable conception rates within 12 months after discontinuing COCs as there are after discontinuing other common nonhormonal or hormonal contraceptive methods. Fertility is not impacted by the duration of COC use. In addition, return to fertility seems to be comparable after discontinuation of extended cycle or continuous COCs compared with traditional-cycle COCs.4

COC safety

Known major risks of COCs include venous thromboembolism (VTE). The risk of VTE is about double among COC users than among nonpregnant nonusers: 3–9 per 10,000 woman-years compared with 1–5.5 In a study by the US Food and Drug Administration, drospirenone-containing COCs had double the risk of VTE than other COCs. However, the position of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists on this increased risk of VTE with drospirenone-containing pills is that it is “possible” and “minimal.”5 It is important to remember that an alternative to COC use is pregnancy, in which the VTE risk is about double that among COC users, at 5–20 per 10,000 woman-years. This risk increases further in the postpartum period, to 40–65 per 10,000 woman-years.5

Another known major risk of COCs is arterial embolic disease, including cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarctions. Women at increased risk for these complications include those with hypertension, diabetes, and/or obesity and women who are aged 35 or older and smoke. Interestingly, women with migraines with aura are at increased risk for stroke but not for myocardial infarction. These women increase their risk of stroke 2- to 4-fold if they use COCs.

Continue to: Different pills for different problems...

Different pills for different problems

With so many pills on the market, it is important for clinicians to know how to choose a particular pill for a particular patient. The following discussion assumes that the patient in question desires a COC for contraception, then offers guidance on how to choose a pill with patient-specific noncontraceptive benefits (TABLE 2).

When HMB is a concern. Patients with heavy menstrual bleeding may experience fewer bleeding and/or spotting days with extended cyclic or continuous use of a COC rather than with traditional cyclic use.6 Examples of such COC options include:

- Introvale and Seasonique, both extended-cycle formulations

- Amethyst, which is formulated without placebo pills so that it can be used continuously

- any other COC prescribed with instructions for the patient to skip placebo pills.

An extrapolated benefit to extended-cycle or continuous COCs use for heavy menstrual bleeding is addressing anemia.

For premenstrual dysphoric disorder, the only randomized controlled trials showing improvement involve drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol pills (Yaz and Yasmin).7 There is also evidence that extended cyclic or continuous use of these formulations is more impactful for premenstrual dysphoric disorder than a traditional cycle.8

Keeping migraine avoidance and prevention in mind. Various studies have looked at the impact of different COC formulations on menstrual-related symptoms. There is evidence of greater improvement in headache, bloating, and dysmenorrhea with extended cyclic or continuous use compared with traditional cyclic use.6

In terms of headache, let us delve into menstrual migraine in particular. Menstrual migraines occur sometime between 2 days prior to 2 days after the first day of menses and are linked to a sharp drop in estrogen levels. COCs are contraindicated in women with menstrual migraines with aura because of the increased stroke risk. For women with menstrual migraines without aura, COCs can prevent migraines. Prevention depends on minimizing fluctuations in estrogen levels; any change in estrogen level greater than 10 µg of ethinyl estradiol may trigger an estrogen-related migraine. All currently available regimens of COCs that comprise 21 days of active pills and 7 days of placebo involve a drop of more than 10 µg. Options that involve a drop of 10 µg or less include any continuous formulation, the extended formulation LoSeasonique (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg and ethinyl estradiol 20 µg for 84 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 7 days), and Lo Loestrin (ethinyl estradiol 10 µg and norethindrone 1 mg for 24 days, then ethinyl estradiol 10 µg for 2 days, then placebo for 2 days).9

What’s best for acne-prone patients? All COCs should improve acne by increasing levels of sex hormone binding globulin. However, some comparative studies have shown drospirenone-containing COCs to be the most effective for acne. This finding makes sense in light of studies demonstrating antiandrogenic effects of drospirenone.10

Managing PCOS symptoms. It seems logical, by extension, that drospirenone-containing COCs would be particularly beneficial for treating hirsutism associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Other low‒androgenic-potential progestins, such as a third-generation progestin (norgestimate or desogestrel), might similarly be hypothesized to be advantageous. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to recommend any one COC formulation over another for the indication of PCOS.11

Ovarian cysts: Can COCs be helpful? COCs are commonly prescribed by gynecologists for patients with functional ovarian cysts. It is important to note that COCs have not been found to hasten the resolution of existing cysts, so they should not be used for this purpose.12 Studies of early COCs, which had high doses of estrogen (on the order of 50 µg), showed lower rates of cysts among users. This effect seems to be attenuated with the lower-estrogen-dose pills that are currently available, but there still appears to be benefit. Therefore, for a patient prone to cysts who desires an oral contraceptive, a COC containing estrogen 35 µg is likely to be the most beneficial of COCs currently on the market.13,14

Lower-dosage COCs in perimenopause may be beneficial. COCs can ameliorate perimenopausal symptoms including abnormal uterine bleeding and vasomotor symptoms. Clinicians are often hesitant to prescribe COCs for perimenopausal women because of increased risk of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer with increasing age. However, age alone is not a contraindication to any contraceptive method. An extended cyclic or continuous regimen COC may be the best choice for a perimenopausal woman in order to avoid vasomotor symptoms that occur during hormone-free intervals. In addition, given the increasing risk of adverse effects like VTE with estrogen dose, a lower estrogen formulation is advisable.15

Patients with epilepsy who are taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are a special population when it comes to COCs. Certain AEDs induce hepatic enzymes involved in the metabolism and protein binding of COCs, which can result in contraceptive failure. Strong inducers are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, perampanel, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Weak inducers are clobazam, eslicarbazepine, felbamate, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and topiramate. Women taking any of the above AEDs are recommended to choose a different form of contraception than a COC. However, if they are limited to COCs for some reason, a preparation containing estrogen 50 µg is recommended. It is speculated that the efficacy and adverse effects of COCs with increased hormone doses, used in combination with enzyme-inducing AEDs, should be comparable to those with standard doses when not combined with AEDs; however, this speculation is unproven.16 There are few COCs on the market with estrogen doses of 50 µg, but a couple of examples are Kelnor and Ogestrel.

Additional factors have to be considered with concurrent COC use with the AED lamotrigine since COCs increase clearance of this agent. Therefore, patients taking lamotrigine who start COCs will need an increase in lamotrigine dose. To avoid fluctuations in lamotrigine serum levels, use of a continuous COC is recommended.17

Continue to: Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks...

Pill types to minimize adverse effects or risks

For women who desire to use a COC for contraception but who are at risk for a particular complication or are bothered by a particular adverse effect, ObGyns can optimize the choice of pill (TABLE 3). For example, women who have adverse effects of nausea and/or breast tenderness may benefit from reducing the estrogen dose to 20 µg or lower.18

Considering VTE

As discussed previously, VTE is a risk with all COCs, but some pills confer greater risk than others. For one, VTE risk increases with estrogen dose. In addition, VTE risk depends on the type of progestin. Drospirenone and third-generation progestins (norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel) confer a higher risk of VTE than first- or second-generation progestins. For example, a pill with estradiol 30 µg and either a third-generation progestin or drospirenone has a 50% to 80% higher risk of VTE compared with a pill with estradiol 30 µg and levonorgestrel.

For patients at particularly high risk for VTE, COCs are contraindicated. For patients for whom COCs are considered medically appropriate but who are at higher risk (eg, obese women), it is wise to use a pill containing a first-generation (norethindrone) or second-generation progestin (levonorgestrel) combined with the lowest dose of estrogen that has tolerable adverse effects.19

What about hypertension concerns?

Let us turn our attention briefly to hypertension and its relation to COC use. While the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association redefined hypertension in 2017 using a threshold of 130/80 mm Hg, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers hypertension to be 140/90 mm Hg in terms of safety of using COCs. ACOG states, “women with blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg may use any hormonal contraceptive method.”20 In women with hypertension in the range of 140‒159 mm Hg systolic or 90‒99 mm Hg diastolic, COCs are category 3 according to the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, meaning that the risks usually outweigh the benefits. For women with blood pressures of 160/110 mm Hg or greater, COCs are category 4 (contraindicated). If a woman with mild hypertension is started on a COC, a drospirenone-containing pill may be the best choice because of its diuretic effects. While other contemporary COCs have been associated with a mild increase in blood pressure, drospirenone-containing pills have not shown this association.21

Continue to: At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain...

At issue: Break-through bleeding, mood, and weight gain

For women bothered by intermenstrual bleeding, use of a COC with a third-generation progestin may be preferable to use of one with a first- or second-generation. It may be because of decreased abnormal bleeding that COCs with third-generation progestins have lower discontinuation rates.22 In addition, COCs containing estrogen 20 µg or less are associated with more intermenstrual bleeding than those with more than 20 µg estrogen.23 Keep in mind that it is common with any COC to have intermenstrual bleeding for the first several months.

For women with pre-existing mood disorders or who report mood changes with COCs, it appears that fluctuations in hormone levels are problematic. Consistently, there is evidence that monophasic pills are preferable to multiphasic and that extended cyclic or continuous use is preferable to traditional cyclic use for mitigating mood adverse effects. There is mixed evidence on whether a low dose of ethinyl estradiol is better for mood.3