User login

Managing herpes simplex virus genital infection in pregnancy

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

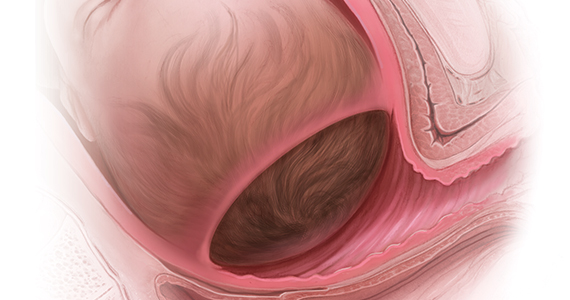

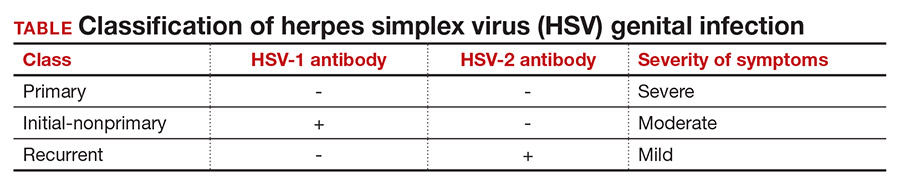

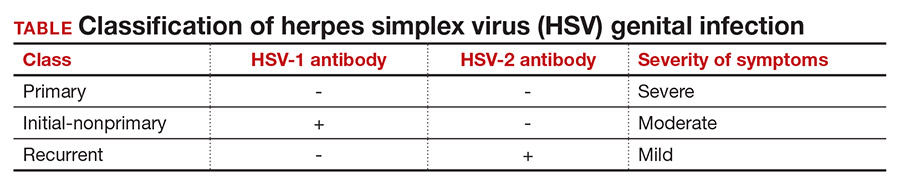

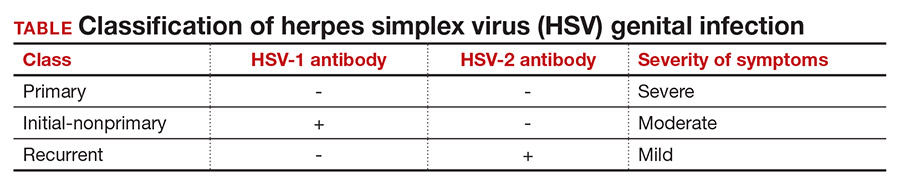

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

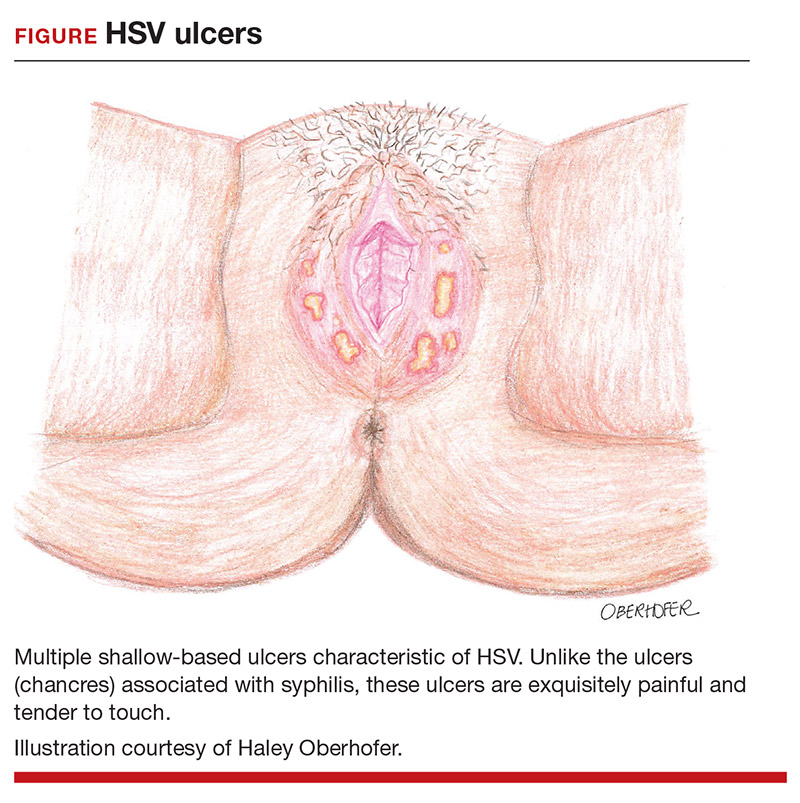

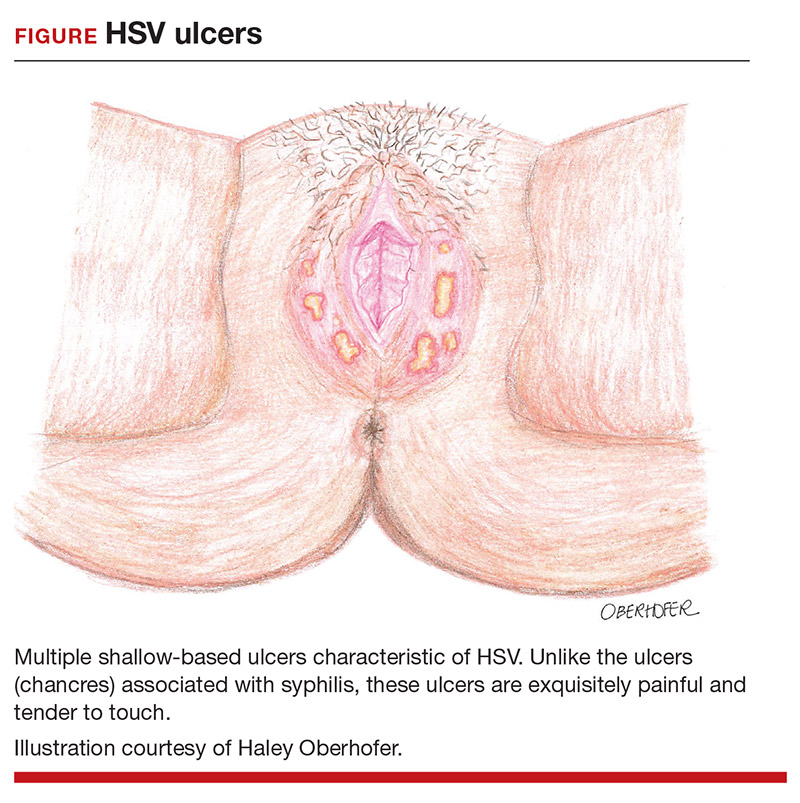

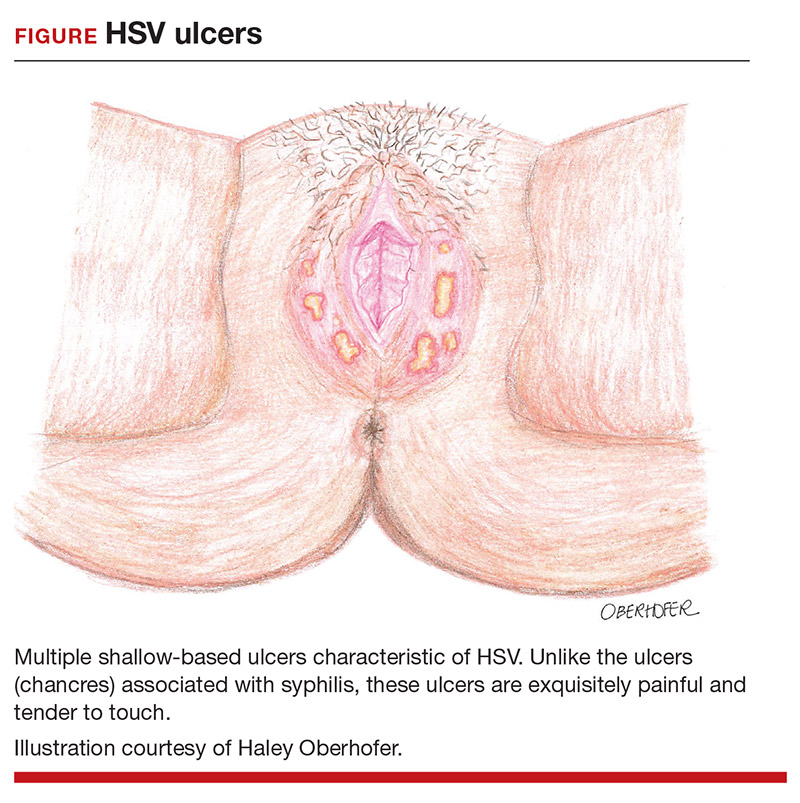

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.

Patient-centered contraceptive care for medically complex patients

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

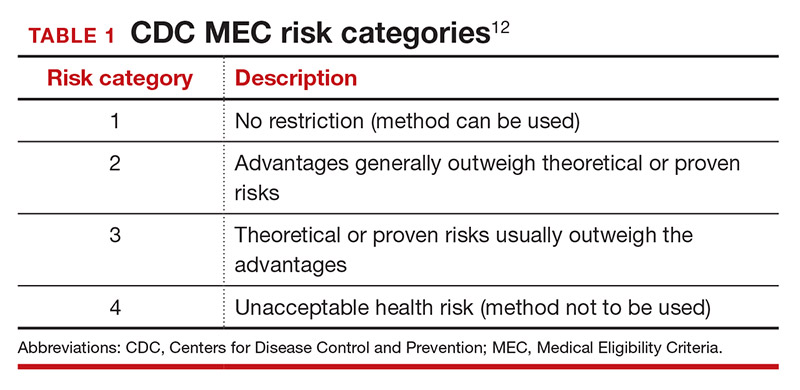

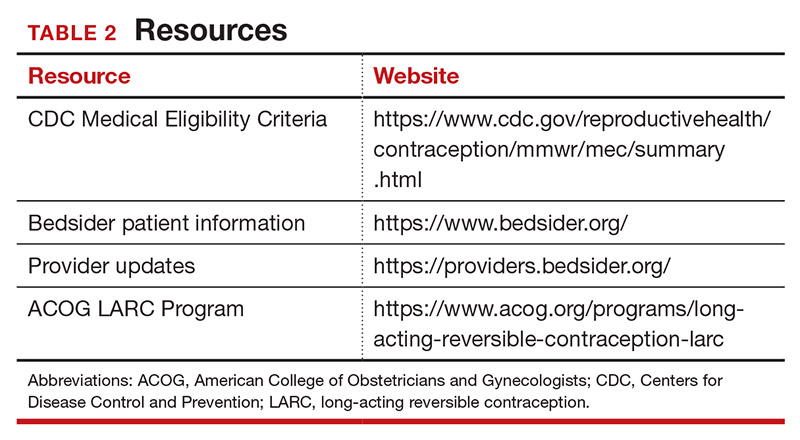

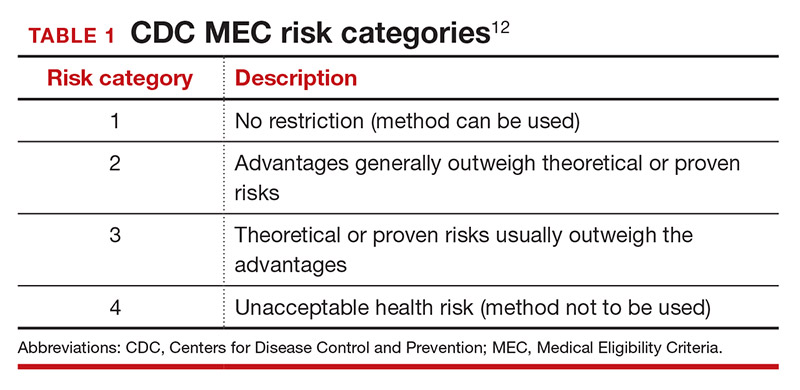

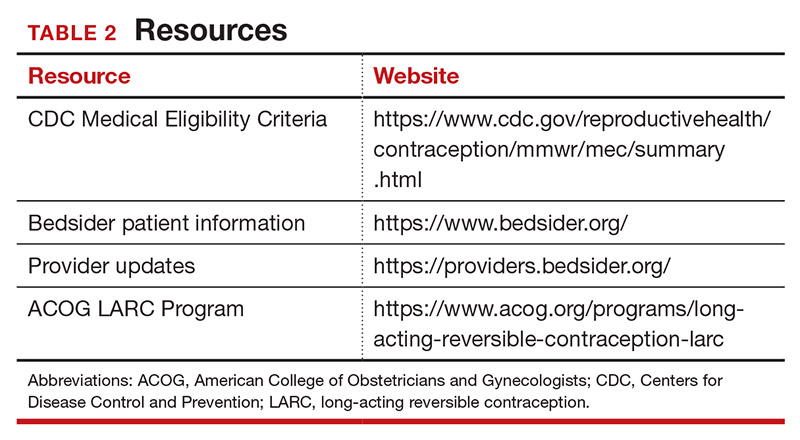

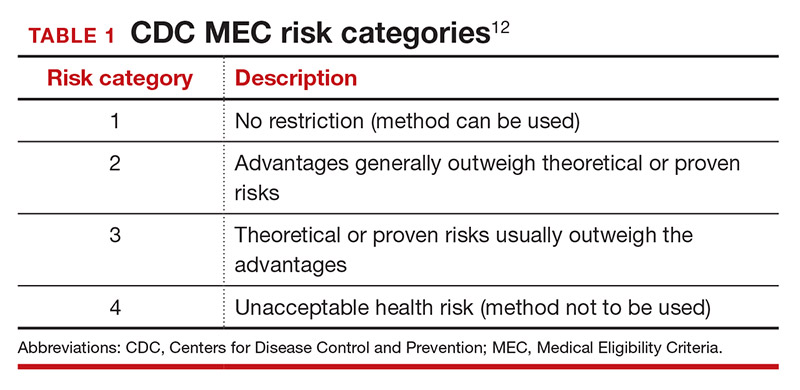

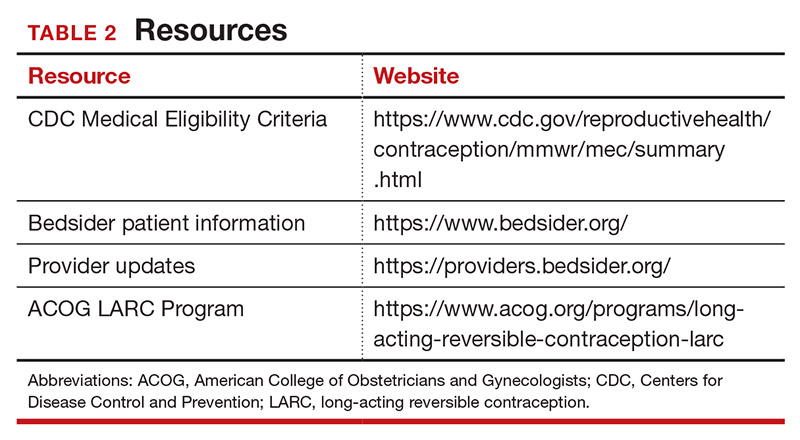

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

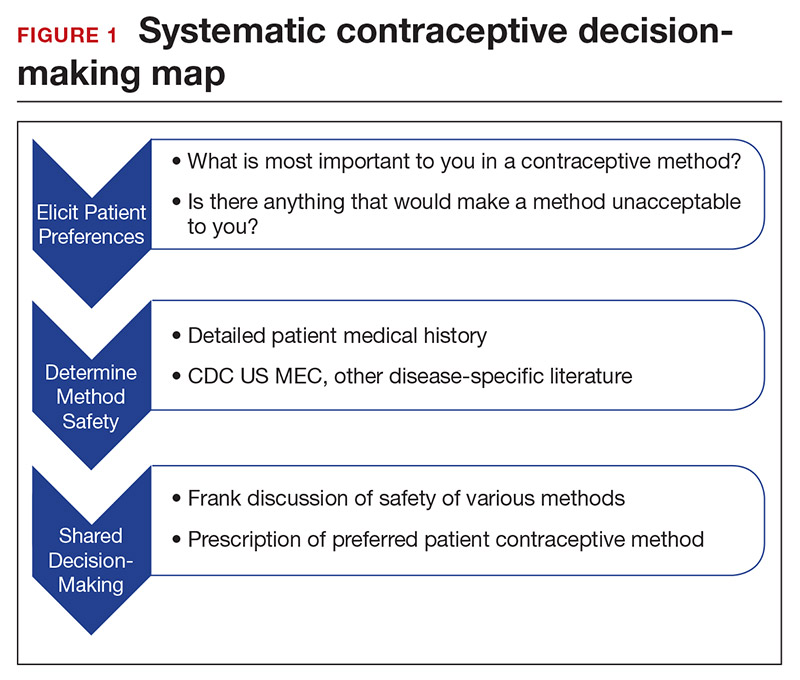

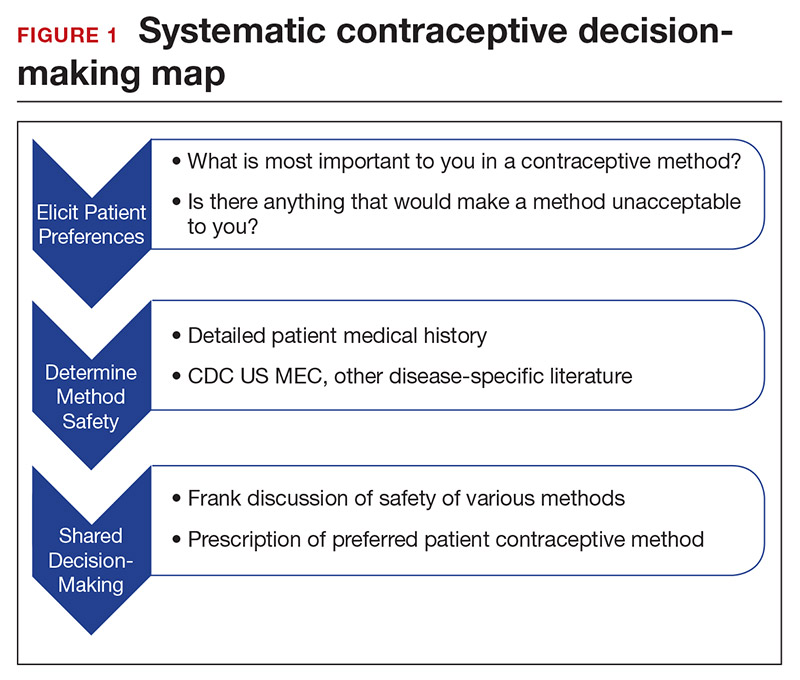

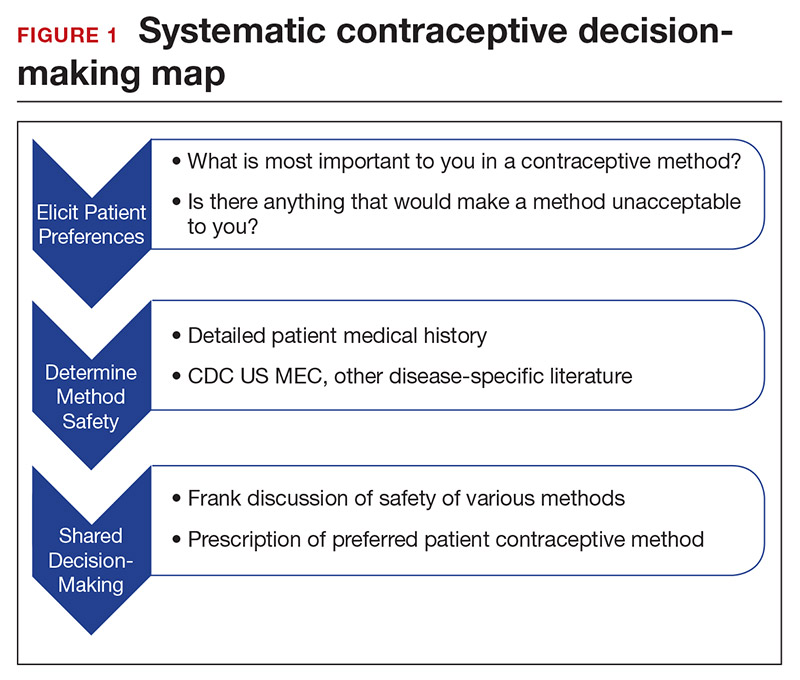

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

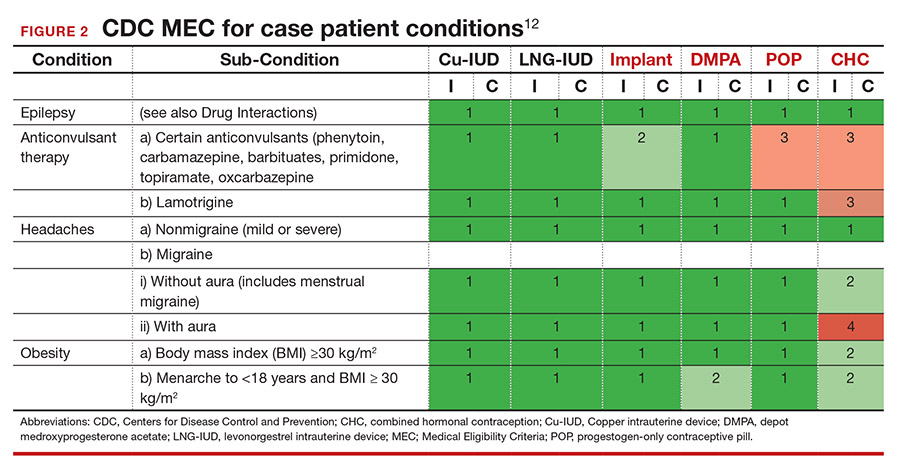

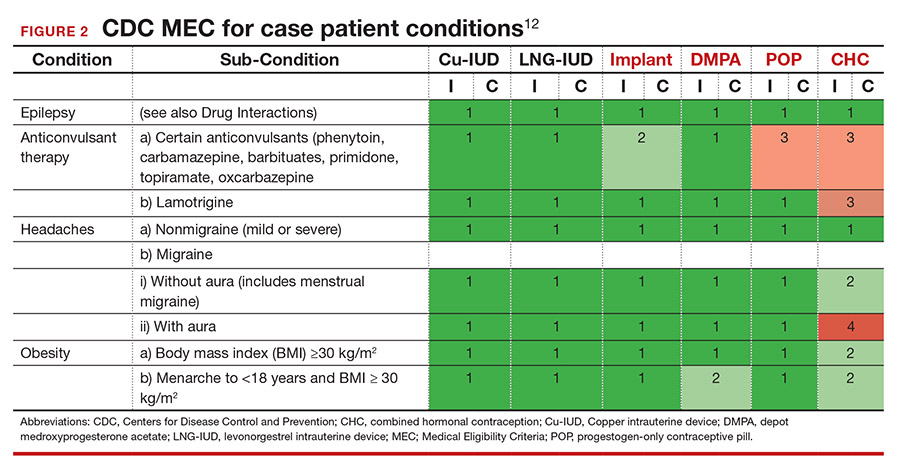

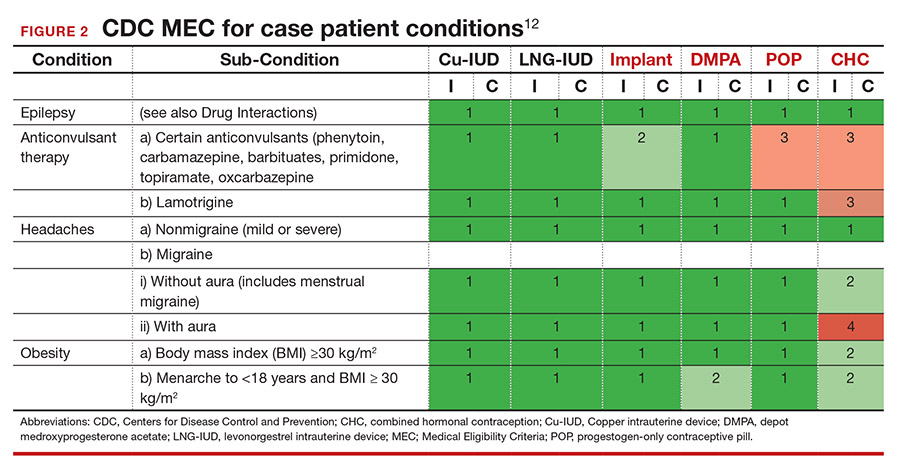

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

CASE Patient-centered counseling for contraception

A 19-year-old woman (G0) with moderately well-controlled seizure disorder while taking levetiracetam, who reports migraines, and has a BMI of 32 kg/m2 presents to your office seeking contraception. She is currently sexually active with her second lifetime partner and uses condoms inconsistently. She is otherwise healthy and has no problems to report. Her last menstrual period (LMP) was 1 week ago, and a pregnancy test today is negative. How do you approach counseling for this patient?

The modern contraceptive patient

Our patients are becoming increasingly medically and socially complicated. Meeting the contraceptive needs of patients with multiple comorbidities can be a daunting task. Doing so in a patient-centered way that also recognizes the social contexts and intimacy inherent to contraceptive care can feel overwhelming. However, by employing a systematic approach to each patient, we can provide safe, effective, individualized care to our medically complex patients. Having a few “go-to tools” can streamline the process.

Medically complex patients are often told that they need to avoid pregnancy or optimize their health conditions prior to becoming pregnant, but they may not receive medically-appropriate contraception.1-3 Additionally, obesity rates in women of reproductive age in the United States are increasing, along with related medical complexities.4 Disparities in contraceptive access and use of particular methods exist by socioeconomic status, body mass index (BMI), age, and geography. 5,6 Evidence-based, shared decision making can improve contraceptive satisfaction.7

Clinicians need to stay attuned to all options. Staying current on available contraceptive methods can broaden clinicians’ thinking and allow patients more choices that are compatible with their medical needs. In the last 2 years alone, a 1-year combined estrogen-progestin vaginal ring, a drospirinone-only pill, and a nonhormonal spermicide have become available for prescription.8-10 Both 52 mg levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for 6 years, and there is excellent data for off-label use to 7 years.11

Tools are available for use. To ensure patient safety, we must evaluate the relative risks of each method given their specific medical history. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC) provides a comprehensive reference for using each contraceptive method category with preexisting medical conditions on a scale from 1 (no restrictions) to 4 (unacceptable health risk) (TABLE 1).12 It is important to remember that pregnancy often poses a larger risk even than category 4 methods. With proper counseling and documentation, a category 3 method may be appropriate in some circumstances. The CDC MEC can serve as an excellent counseling tool and is available as a free smartphone app. The app can be downloaded via https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/mmwr/mec/summary.html (TABLE 2).

In a shared decision-making model, we contribute our medical knowledge, and the patient provides expertise on her own values and social context.13 By starting the contraceptive conversation with open-ended questions, we invite the patient to lead the discussion. We partner with them in finding a safe, effective method that is compatible with both the medical history and stated preferences. Bedsider.org has an interactive tool that allows patients to explore different contraceptive methods and compare their various characteristics. While tiered efficacy models may help us to organize our thinking as clinicians, it is important to recognize that patients may consider side effect profiles, nonreliance on clinicians for discontinuation, or other priorities above effectiveness.

Continue to: How to craft your approach...

How to craft your approach

Developing a systematic approach to the medically complex patient seeking contraception can help to change an initially daunting task into a fulfilling experience (FIGURE 1). Begin by eliciting patient priorities. Then frame the discussion around them, rather than around efficacy. Although anecdotal reasoning can initially be frustrating (“My best friend’s IUD was really painful and I don’t want anything like that inside me!”), learning about these experiences prior to counseling can be incredibly informative. Ask detailed questions about medical comorbidities, as these subtleties may change the relative safety of each method. Finally, engage the patient in a frank discussion of the relative merits, safety, and use of all medically appropriate contraceptive methods. The right method is the method that the patient will use.

CASE Continued: Applying our counseling method

Upon open-ended questioning, the patient tells you that she absolutely cannot be on a contraceptive method that will make her gain weight. She has several friends who told her that they gained weight on “the shot” and “the implant.” She wants to avoid these at all costs and thinks she might want to take “the pill.” She also tells you that she is in college and that her daily routine varies significantly between weekdays and weekends. She definitely does not want to get pregnant until she has completed her education, which will be at least 3 years from now.

To best counsel this patient and arrive at the most appropriate contraceptive option for her, clarify her medical history and employ shared decision-making for her chosen method.

Probe her seizure history

She tells you that she has had seizures since she was a child, and the last one occurred 4 months ago when she ran out of her anticonvulsant medication. Her seizures have never been associated with her menses. This is an important piece of information. The frequency of catamenial seizures can be decreased with use of any method that suppresses ovulation, such as depot-medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) injections, continuous combined hormonal contraceptive (CHC) pills or ring, or the implant. Noncatamenial seizures also can be suppressed by DMPA, which increases the seizure threshold.14 Many anticonvulsants are metabolized through cytochrome P450 in the liver and, therefore, interact with all oral contraceptive formulations. However, levetiracetam is not among them and may be safely taken with progestin-only pills. At this point, all contraceptive methods remain CDC MEC category 1 (FIGURE 2).12

Ask migraine specifics

It is important to clarify whether or not the patient experiences aura with her migraines. She says that she always knows when a migraine is coming on because she sees floaters in her vision for about 30 minutes prior to the onset of excruciating headache. One tool that may aid in the diagnosis of aura is the Visual Aura Rating Scale (VARS).15 The presence of aura renders all CHCs category 4 by the CDC MEC.12 (See FIGURE 2.)

Discuss contraceptive pros and cons

Have a frank discussion about the relative risks and benefits of each method. For instance, although DMPA may improve the patient’s seizures, she has expressed a desire to avoid weight gain, and DMPA is the only method consistently shown in studies to do so.16 Her seizures are not associated with menses, so menstrual suppression is neither beneficial nor deleterious. Although her current medication levetiracetam does not influence the metabolism of contraceptive methods, many anticonvulsants do. Offer anticipatory guidance around seeking gynecologic consultation with any future seizure medication changes.

Allow for shared decision-making on a final choice

The patient indicated that she had been considering “the pill” when she made this appointment, but you have explained that CHCs are contraindicated for her. She is concerned that she will not be able to stick to the strict dosing schedule of a progestin-only pill. Although you inform her that the drospirinone-only pill has a more forgiving window, the patient decides that she wants a “set it and forget it” method and opts for an IUD.

CASE Resolved

Following recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), you provide for same-day insertion of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD.17 You use a paracervical block in addition to ibuprofen for pain control.18 The patient undergoes same-day testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia, and she understands that if a test is found to be positive, she can be treated without removing the IUD. You provide instruction on the importance of dual contraceptive use with barrier methods for the prevention of STIs. The patient is instructed on self-string checks, and she acknowledges that she will call if she has any concerns; no routine follow-up is required. She leaves her visit satisfied with her preferred, safe, effective contraceptive method in situ. ●

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

- Lauring JR, Lehman EB, Deimling TA, et al. Combined hormonal contraception use in reproductive-age women with contraindications to estrogen use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:330.e1-e7.

- Mendel A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA, et al. Use of combined hormonal contraceptives among women with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without medical contraindications to oestrogen. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:1259-1267.

- Judge CP, Zhao X, Sileanu FE, et al. Medical contraindications to estrogen and contraceptive use among women veterans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:234.e1-234.e9.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;360:1-8.

- Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive use in the United States. April 2020. . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Mosher WD, Lantos H, Burke AE. Obesity and contraceptive use among women 20–44 years of age in the United States: results from the 2011–15 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). Contraception. 2018:97:392-398.

- Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, et al. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95:452-455.

- Annovera [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD, Inc; 2020.

- Slynd [package insert]. Florham Park, NJ: Exeltis; 2019.

- Phexxi [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Evofem; 2020.

- , et al. Safety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380A. Contraception. 2016;93:498-506.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2016. . Accessed March 23, 2021.

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681-692.

- Dutton C, Foldvary‐Schaefer N. Contraception in women with epilepsy: pharmacokinetic interactions, contraceptive options, and management. Int Rev Neurobiol. 83;2008:113-134.

- Eriksen MK, Thomsen LL, Olesen J. The visual aura rating scale (VARS) for migraine aura diagnosis. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:801-810.

- ME, , , et al. Prospective study of weight change in new adolescent users of DMPA, NET-EN, COCs, nonusers and discontinuers of hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2010;81:30-34.

- Espey E, Hofler L. Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Practice bulletin 186. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-269.

- Akers AY, Steinway C, Sonalkar S, et al. Reducing pain during intrauterine device insertion: a randomized controlled trial in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:795-802.

Can a once-daily oral formulation treat symptoms of uterine fibroids without causing hot flashes or bone loss?

Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN 3rd, et al. Treatment of uterine fibroid symptoms with relugolix combination therapy. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:630-642. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008283

Expert Commentary

By age 50, approximately 70% of White women and 80% of Black women will have uterine fibroids.1 Of these, about 25% will have symptoms—most often including heavy menstrual bleeding,2 and associated pain the second most common symptom.3 First-line treatment has traditionally been hormonal contraceptives. Injectable gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist like leuprolide acetate have been commonly employed, although their actual approved indication is “for concomitant use with iron therapy for preoperative hematologic improvement of patients with anemia caused by uterine leiomyomata (fibroids).”4 Recently, an oral GnRH antagonist, elagolix, combined with estrogen and progestogen, was approved for treatment of uterine fibroids for up to 24 months. However, it is dosed twice per day because of its short half-life and results in a loss of bone mineral density at 1 year.5,6

Details of the studies

Al-Hendy and colleagues report on two double-blind 24-week phase 3 trials involving women with heavy menstrual bleeding associated with fibroids. There were just under 400 women in each trial. There was a 1:1:1 randomization to: placebo, once-daily oral relugolix 40 mg with 1 mg estradiol and 0.5 mg norethindrone acetate, or oral relugolix by itself for 12 weeks followed by the combination for 12 weeks (referred to as the “delayed relugolix combination therapy” arm).

Results. The primary end point was the percentage of patients who had a volume of menstrual blood loss less than 80 mL and a ≥50% reduction in blood loss volume as measured by the alkaline hematin method. The baseline blood loss in these studies ranged from approximately 210–250 mL. Secondary end points included amenorrhea, volume of menstrual blood loss, distress from bleeding and pelvic discomfort, anemia, pain, uterine volume, and the largest fibroid volume.

In trials one and two, 73% and 71% of patients in the relugolix combination groups, respectively, achieved the primary endpoint, compared with 19% and 15% in the placebo groups (P <.001). In addition, all secondary endpoints except largest fibroid volume were significantly improved versus placebo. Adverse events, including any change in bone mineral density, were no different between the combination and placebo groups. The delayed combination groups did have more hot flashes and diminished bone density compared with both the placebo and combination groups.

Strengths and weaknesses

The studies appropriately enrolled women with a mean age of 41–42 years and a mean BMI >30 kg/m2, and more than 50% were African American. Thus, the samples are adequately representative of the type of population most likely to have fibroids and associated symptoms. The results showed the advantages of built-in “add back therapy” with estrogen plus progestogen, as the vasomotor symptoms and bone loss that treatment with a GnRH antagonist alone produces were reduced.

Although the trials were only conducted for 24 weeks, efficacy was seen as early as 4 weeks, and was clearly maintained throughout the full trials—and there is no scientific reason to assume it would not be maintained indefinitely. However, one cannot make a similar assumption about long-term safety. As another GnRH antagonist, with a shorter half-life requiring twice-daily-dosing with add back therapy, has been approved for use for 2 years, it is likely that the once-daily formulation of combination relugolix will be approved for this timeframe as well. Still, with patients’ mean age of 41–42 years, what will clinicians do after 2-year treatment? Clearly, study of long-term safety would be valuable. ●

Fibroids are extremely common in clinical practice, with their associated symptoms depending greatly on size and location. In many patients, symptoms are serious enough to be the most common indication for hysterectomy. In the past, combination oral contraceptives, injectable leuprolide acetate, and more recently, a GnRH antagonist given twice daily with estrogen/progestogen add-back have been utilized. The formulation described in Al-Hendy and colleagues’ study, which is dosed once per day and appears to not increase vasomotor symptoms or diminish bone mass, may provide a very nice “tool” in the clinician’s toolbox to either avoid any surgery in some patients (likely those aged closer to menopause) or optimize other patients preoperatively in terms of reversing anemia and reducing uterine volume, thus making any planned surgical procedure safer.

STEVEN R. GOLDSTEIN, MD, NCMP, CCD

- Wise LA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: from menarche to menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:2-24.

- Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, et al. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:319.e1-319.e20.

- David M, Pitz CM, Mihaylova A, et al. Myoma-associated pain frequency and intensity: a retrospective evaluation of 1548 myoma patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:137-140.

- Lupron Depot [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2018.

- Schlaff WD, Ackerman RT, Al-Hendy A, et al. Elagolix for heavy menstrual bleeding in women with uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:328-340.

- Oriahnn [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2020.

Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN 3rd, et al. Treatment of uterine fibroid symptoms with relugolix combination therapy. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:630-642. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008283

Expert Commentary