User login

FDA, CDC urge pause of J&J COVID vaccine

The Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 13 recommended that use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine be paused after reports of blood clots in patients receiving the shot, the agencies have announced.

In a statement, FDA said 6.8 million doses of the J&J vaccine have been administered and the agency is investigating six reported cases of a rare and severe blood clot occurring in patients who received the vaccine.

The pause is intended to give time to alert the public to this "very rare" condition, experts said during a joint CDC-FDA media briefing April 13.

"It was clear to us that we needed to alert the public," Janet Woodcock, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said. The move also will allow "time for the healthcare community to learn what they need to know about how to diagnose, treat and report" any additional cases.

The CDC will convene a meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on April 14 to review the cases.

"I know the information today will be very concerning to Americans who have already received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine," said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director at the CDC.

"For people who got the vaccine more than one month ago, the risk is very low at this time," she added. "For people who recently got the vaccine, in the last couple of weeks, look for symptoms."

Headache, leg pain, abdominal pain, and shortness of breath were among the reported symptoms. All six cases arose within 6 to 13 days of receipt of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Traditional treatment dangerous

Importantly, treatment for traditional blood clots, such as the drug heparin, should not be used for these clots. "The issue here with these types of blood clots is that if one administers the standard treatment we give for blood clots, one can cause tremendous harm or it can be fatal," said Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

If health care providers see people with these symptoms along with a low platelet count or blood clots, they should ask about any recent vaccinations, Dr. Marks added.

Headache is a common side effect of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Marks said, but it typically happens within a day or two. In contrast, the headaches associated with these blood clots come 1 to 2 weeks later and were very severe.

Not all of the six women involved in the events had a pre-existing condition or risk factor, Dr. Schuchat said.

Severe but 'extremely rare'

To put the numbers in context, the six reported events occurred among millions of people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to date.

"There have been six reports of a severe stroke-like illness due to low platelet count and more than six million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been administered so far," Dr. Schuchat said.

"I would like to stress these events are extremely rare," Dr. Woodcock said, "but we take all reports of adverse events after vaccination very seriously."

The company response

Johnson & Johnson in a statement said, "We are aware of an extremely rare disorder involving people with blood clots in combination with low platelets in a small number of individuals who have received our COVID-19 vaccine. The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are reviewing data involving six reported U.S. cases out of more than 6.8 million doses administered. Out of an abundance of caution, the CDC and FDA have recommended a pause in the use of our vaccine."

The company said they are also reviewing these cases with European regulators and "we have made the decision to proactively delay the rollout of our vaccine in Europe."

Overall vaccinations continuing apace

"This announcement will not have a significant impact on our vaccination plan. Johnson & Johnson vaccine makes up less than 5% of the recorded shots in arms in the United States to date," Jeff Zients, White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a statement.

"Based on actions taken by the president earlier this year, the United States has secured enough Pfizer and Moderna doses for 300 million Americans. We are working now with our state and federal partners to get anyone scheduled for a J&J vaccine quickly rescheduled for a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine," he added.

The likely duration of the pause remains unclear.

"I know this has been a long and difficult pandemic, and people are tired of the steps they have to take," Dr. Schuchat said. "Steps taken today make sure the health care system is ready to diagnose, treat and report [any additional cases] and the public has the information necessary to stay safe."

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 4/13/21.

The Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 13 recommended that use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine be paused after reports of blood clots in patients receiving the shot, the agencies have announced.

In a statement, FDA said 6.8 million doses of the J&J vaccine have been administered and the agency is investigating six reported cases of a rare and severe blood clot occurring in patients who received the vaccine.

The pause is intended to give time to alert the public to this "very rare" condition, experts said during a joint CDC-FDA media briefing April 13.

"It was clear to us that we needed to alert the public," Janet Woodcock, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said. The move also will allow "time for the healthcare community to learn what they need to know about how to diagnose, treat and report" any additional cases.

The CDC will convene a meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on April 14 to review the cases.

"I know the information today will be very concerning to Americans who have already received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine," said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director at the CDC.

"For people who got the vaccine more than one month ago, the risk is very low at this time," she added. "For people who recently got the vaccine, in the last couple of weeks, look for symptoms."

Headache, leg pain, abdominal pain, and shortness of breath were among the reported symptoms. All six cases arose within 6 to 13 days of receipt of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Traditional treatment dangerous

Importantly, treatment for traditional blood clots, such as the drug heparin, should not be used for these clots. "The issue here with these types of blood clots is that if one administers the standard treatment we give for blood clots, one can cause tremendous harm or it can be fatal," said Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

If health care providers see people with these symptoms along with a low platelet count or blood clots, they should ask about any recent vaccinations, Dr. Marks added.

Headache is a common side effect of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Marks said, but it typically happens within a day or two. In contrast, the headaches associated with these blood clots come 1 to 2 weeks later and were very severe.

Not all of the six women involved in the events had a pre-existing condition or risk factor, Dr. Schuchat said.

Severe but 'extremely rare'

To put the numbers in context, the six reported events occurred among millions of people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to date.

"There have been six reports of a severe stroke-like illness due to low platelet count and more than six million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been administered so far," Dr. Schuchat said.

"I would like to stress these events are extremely rare," Dr. Woodcock said, "but we take all reports of adverse events after vaccination very seriously."

The company response

Johnson & Johnson in a statement said, "We are aware of an extremely rare disorder involving people with blood clots in combination with low platelets in a small number of individuals who have received our COVID-19 vaccine. The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are reviewing data involving six reported U.S. cases out of more than 6.8 million doses administered. Out of an abundance of caution, the CDC and FDA have recommended a pause in the use of our vaccine."

The company said they are also reviewing these cases with European regulators and "we have made the decision to proactively delay the rollout of our vaccine in Europe."

Overall vaccinations continuing apace

"This announcement will not have a significant impact on our vaccination plan. Johnson & Johnson vaccine makes up less than 5% of the recorded shots in arms in the United States to date," Jeff Zients, White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a statement.

"Based on actions taken by the president earlier this year, the United States has secured enough Pfizer and Moderna doses for 300 million Americans. We are working now with our state and federal partners to get anyone scheduled for a J&J vaccine quickly rescheduled for a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine," he added.

The likely duration of the pause remains unclear.

"I know this has been a long and difficult pandemic, and people are tired of the steps they have to take," Dr. Schuchat said. "Steps taken today make sure the health care system is ready to diagnose, treat and report [any additional cases] and the public has the information necessary to stay safe."

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 4/13/21.

The Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on April 13 recommended that use of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine be paused after reports of blood clots in patients receiving the shot, the agencies have announced.

In a statement, FDA said 6.8 million doses of the J&J vaccine have been administered and the agency is investigating six reported cases of a rare and severe blood clot occurring in patients who received the vaccine.

The pause is intended to give time to alert the public to this "very rare" condition, experts said during a joint CDC-FDA media briefing April 13.

"It was clear to us that we needed to alert the public," Janet Woodcock, MD, acting FDA commissioner, said. The move also will allow "time for the healthcare community to learn what they need to know about how to diagnose, treat and report" any additional cases.

The CDC will convene a meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices on April 14 to review the cases.

"I know the information today will be very concerning to Americans who have already received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine," said Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director at the CDC.

"For people who got the vaccine more than one month ago, the risk is very low at this time," she added. "For people who recently got the vaccine, in the last couple of weeks, look for symptoms."

Headache, leg pain, abdominal pain, and shortness of breath were among the reported symptoms. All six cases arose within 6 to 13 days of receipt of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

Traditional treatment dangerous

Importantly, treatment for traditional blood clots, such as the drug heparin, should not be used for these clots. "The issue here with these types of blood clots is that if one administers the standard treatment we give for blood clots, one can cause tremendous harm or it can be fatal," said Peter Marks, MD, director of the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

If health care providers see people with these symptoms along with a low platelet count or blood clots, they should ask about any recent vaccinations, Dr. Marks added.

Headache is a common side effect of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Marks said, but it typically happens within a day or two. In contrast, the headaches associated with these blood clots come 1 to 2 weeks later and were very severe.

Not all of the six women involved in the events had a pre-existing condition or risk factor, Dr. Schuchat said.

Severe but 'extremely rare'

To put the numbers in context, the six reported events occurred among millions of people who received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to date.

"There have been six reports of a severe stroke-like illness due to low platelet count and more than six million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been administered so far," Dr. Schuchat said.

"I would like to stress these events are extremely rare," Dr. Woodcock said, "but we take all reports of adverse events after vaccination very seriously."

The company response

Johnson & Johnson in a statement said, "We are aware of an extremely rare disorder involving people with blood clots in combination with low platelets in a small number of individuals who have received our COVID-19 vaccine. The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are reviewing data involving six reported U.S. cases out of more than 6.8 million doses administered. Out of an abundance of caution, the CDC and FDA have recommended a pause in the use of our vaccine."

The company said they are also reviewing these cases with European regulators and "we have made the decision to proactively delay the rollout of our vaccine in Europe."

Overall vaccinations continuing apace

"This announcement will not have a significant impact on our vaccination plan. Johnson & Johnson vaccine makes up less than 5% of the recorded shots in arms in the United States to date," Jeff Zients, White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a statement.

"Based on actions taken by the president earlier this year, the United States has secured enough Pfizer and Moderna doses for 300 million Americans. We are working now with our state and federal partners to get anyone scheduled for a J&J vaccine quickly rescheduled for a Pfizer or Moderna vaccine," he added.

The likely duration of the pause remains unclear.

"I know this has been a long and difficult pandemic, and people are tired of the steps they have to take," Dr. Schuchat said. "Steps taken today make sure the health care system is ready to diagnose, treat and report [any additional cases] and the public has the information necessary to stay safe."

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 4/13/21.

OCS heart system earns hard-won backing of FDA panel

After more than 10 hours of intense debate, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel gave its support to a premarket approval application (PMA) for the TransMedics Organ Care System (OCS) Heart system.

The OCS Heart is a portable extracorporeal perfusion and monitoring system designed to keep a donor heart in a normothermic, beating state. The “heart in a box” technology allows donor hearts to be transported across longer distances than is possible with standard cold storage, which can safely preserve donor hearts for about 4 hours.

The Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee voted 12 to 5, with 1 abstention, that the benefits of the OCS Heart System outweigh its risks.

The panel voted in favor of the OCS Heart being effective (10 yes, 6 no, and 2 abstaining) and safe (9 yes, 7 no, 2 abstaining) but not without mixed feelings.

James Blankenship, MD, a cardiologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, voted yes to all three questions but said: “If it had been compared to standard of care, I would have voted no to all three. But if it’s compared to getting an [left ventricular assist device] LVAD or not getting a heart at all, I would say the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Marc R. Katz, MD, chief of cardiothoracic surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, also gave universal support, noting that the rate of heart transplantations has been flat for years. “This is a big step forward toward being able to expand that number. Now all that said, it obviously was a less-than-perfect study and I do think there needs to be some constraints put on the utilization.”

The panel reviewed data from the single-arm OCS Heart EXPAND trial and associated EXPAND Continued Access Protocol (CAP), as well the sponsor’s first OCS Heart trial, PROCEED II.

EXPAND met its effectiveness endpoint, with 88% of donor hearts successfully transplanted, an 8% incidence of severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD) 24 hours after transplantation, and 94.6% survival at 30 days.

Data from 41 patients with 30-day follow-up in the ongoing EXPAND CAP show 91% of donor hearts were utilized, a 2.4% incidence of severe PGD, and 100% 30-day survival.

The sponsor and the FDA clashed over changes made to the trial after the PMA was submitted, the appropriateness of the effectiveness outcome, and claims by the FDA that there was substantial overlap in demographic characteristics between the extended criteria donor hearts in the EXPAND trials and the standard criteria donor hearts in PROCEED II.

TransMedics previously submitted a PMA based on PROCEED II but it noted in submitted documents that it was withdrawn because of “fundamental disagreements with FDA” on the interpretation of a post hoc analysis with United Network for Organ Sharing registry data that identified increased all-cause mortality risk but comparable cardiac-related mortality in patients with OCS hearts.

During the marathon hearing, FDA officials presented several post hoc analyses, including one stratified by donor inclusion criteria, in which 30-day survival estimates were worse in recipients of single-criterion organs than for those receiving donor organs with multiple inclusion criteria (85% vs. 91.4%). In a second analysis, 2-year point estimates of survival also trended lower with donor organs having only one extended criterion.

Reported EXPAND CAP 6- and 12-month survival estimates were 100% and 93%, respectively, which was higher than EXPAND (93% and 84%), but there was substantial censoring (>50%) at 6 months and beyond, FDA officials said.

When EXPAND and CAP data were pooled, modeled survival curves shifted upward but there was a substantial site effect, with a single site contributing 46% of data, which may affect generalizability of the results, they noted.

“I voted yes for safety, no for efficacy, and no for approval and I’d just like to say I found this to be the most difficult vote in my experience on this panel,” John Hirshfeld, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “I was very concerned that the PROCEED data suggests a possible harm, and in the absence of an interpretable comparator for the EXPAND trial, it’s really not possible to decide if there’s efficacy.”

Keith B. Allen, MD, director of surgical research at Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City (Mo.), said, “I voted no on safety; I’m not going to give the company a pass. I think their animal data was sorely lacking and a lot of issues over the last 10 years could have been addressed with some key animal studies.

“For efficacy and risk/benefit, I voted yes for both,” he said. “Had this been standard of care and only PROCEED II, I would have voted no, but I do think there are a lot of hearts that go in the bucket and this is a challenging population.”

More than a dozen physicians and patients spoke at the open public hearing about the potential for the device to expand donor heart utilization, including a recipient whose own father died while waiting on the transplant list. Only about 3 out of every 10 donated hearts are used for transplant. To ensure fair access, particularly for patients in rural areas, federal changes in 2020 mandate that organs be allocated to the sickest patients first.

Data showed that the OCS Heart System was associated with shorter waiting list times, compared with U.S. averages but longer preservation times than cold static preservation.

In all, 13% of accepted donor organs were subsequently turned down after OCS heart preservation. Lactate levels were cited as the principal reason for turn-down but, FDA officials said, the validity of using lactate as a marker for transplantability is unclear.

Pathologic analysis of OCS Heart turned-down donor hearts with stable antemortem hemodynamics, normal or near-normal anatomy and normal ventricular function by echocardiography, and autopsy findings of acute diffuse or multifocal myocardial damage “suggest that in an important proportion of cases the OCS Heart system did not provide effective organ preservation or its use caused severe myocardial damage to what might have been an acceptable graft for transplant,” said Andrew Farb, MD, chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Cardiovascular Devices.

Proposed indication

In the present PMA, the OCS Heart System is indicated for donor hearts with one or more of the following characteristics: an expected cross-clamp or ischemic time of at least 4 hours because of donor or recipient characteristics; or an expected total cross-clamp time of at least 2 hours plus one of the following risk factors: donor age 55 or older, history of cardiac arrest and downtime of at least 20 minutes, history of alcoholism, history of diabetes, donor ejection fraction of 40%-50%,history of left ventricular hypertrophy, and donor angiogram with luminal irregularities but no significant coronary artery disease

Several members voiced concern about “indication creep” should the device be approved by the FDA, and highlighted the 2-hour cross-clamp time plus wide-ranging risk factors.

“I’m a surgeon and I voted no on all three counts,” said Murray H. Kwon, MD, Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center. “As far as risk/benefit, if it was just limited to one group – the 4-hour plus – I would say yes, but if you’re going to tell me that there’s a risk/benefit for the 2-hour with the alcoholic, I don’t know how that was proved in anything.”

Dr. Kwon was also troubled by lack of proper controls and by the one quarter of patients who ended up on mechanical circulatory support in the first 30 days after transplant. “I find that highly aberrant.”

Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said the unmet need for patients with refractory, end-stage heart failure is challenging and quite emotional, but also voted no across the board, citing concerns about a lack of comparator in the EXPAND trials and overall out-of-body ischemic time.

“As it relates to risk/benefit, I thought long and hard about voting yes despite all the unknowns because of this emotion, but ultimately I voted no because of the secondary 2-hours plus alcoholism, diabetes, or minor coronary disease, in which the ischemic burden and ongoing lactate production concern me,” he said.

Although the panel decision is nonbinding, there was strong support from the committee members for a randomized, postapproval trial and more complete animal studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After more than 10 hours of intense debate, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel gave its support to a premarket approval application (PMA) for the TransMedics Organ Care System (OCS) Heart system.

The OCS Heart is a portable extracorporeal perfusion and monitoring system designed to keep a donor heart in a normothermic, beating state. The “heart in a box” technology allows donor hearts to be transported across longer distances than is possible with standard cold storage, which can safely preserve donor hearts for about 4 hours.

The Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee voted 12 to 5, with 1 abstention, that the benefits of the OCS Heart System outweigh its risks.

The panel voted in favor of the OCS Heart being effective (10 yes, 6 no, and 2 abstaining) and safe (9 yes, 7 no, 2 abstaining) but not without mixed feelings.

James Blankenship, MD, a cardiologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, voted yes to all three questions but said: “If it had been compared to standard of care, I would have voted no to all three. But if it’s compared to getting an [left ventricular assist device] LVAD or not getting a heart at all, I would say the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Marc R. Katz, MD, chief of cardiothoracic surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, also gave universal support, noting that the rate of heart transplantations has been flat for years. “This is a big step forward toward being able to expand that number. Now all that said, it obviously was a less-than-perfect study and I do think there needs to be some constraints put on the utilization.”

The panel reviewed data from the single-arm OCS Heart EXPAND trial and associated EXPAND Continued Access Protocol (CAP), as well the sponsor’s first OCS Heart trial, PROCEED II.

EXPAND met its effectiveness endpoint, with 88% of donor hearts successfully transplanted, an 8% incidence of severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD) 24 hours after transplantation, and 94.6% survival at 30 days.

Data from 41 patients with 30-day follow-up in the ongoing EXPAND CAP show 91% of donor hearts were utilized, a 2.4% incidence of severe PGD, and 100% 30-day survival.

The sponsor and the FDA clashed over changes made to the trial after the PMA was submitted, the appropriateness of the effectiveness outcome, and claims by the FDA that there was substantial overlap in demographic characteristics between the extended criteria donor hearts in the EXPAND trials and the standard criteria donor hearts in PROCEED II.

TransMedics previously submitted a PMA based on PROCEED II but it noted in submitted documents that it was withdrawn because of “fundamental disagreements with FDA” on the interpretation of a post hoc analysis with United Network for Organ Sharing registry data that identified increased all-cause mortality risk but comparable cardiac-related mortality in patients with OCS hearts.

During the marathon hearing, FDA officials presented several post hoc analyses, including one stratified by donor inclusion criteria, in which 30-day survival estimates were worse in recipients of single-criterion organs than for those receiving donor organs with multiple inclusion criteria (85% vs. 91.4%). In a second analysis, 2-year point estimates of survival also trended lower with donor organs having only one extended criterion.

Reported EXPAND CAP 6- and 12-month survival estimates were 100% and 93%, respectively, which was higher than EXPAND (93% and 84%), but there was substantial censoring (>50%) at 6 months and beyond, FDA officials said.

When EXPAND and CAP data were pooled, modeled survival curves shifted upward but there was a substantial site effect, with a single site contributing 46% of data, which may affect generalizability of the results, they noted.

“I voted yes for safety, no for efficacy, and no for approval and I’d just like to say I found this to be the most difficult vote in my experience on this panel,” John Hirshfeld, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “I was very concerned that the PROCEED data suggests a possible harm, and in the absence of an interpretable comparator for the EXPAND trial, it’s really not possible to decide if there’s efficacy.”

Keith B. Allen, MD, director of surgical research at Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City (Mo.), said, “I voted no on safety; I’m not going to give the company a pass. I think their animal data was sorely lacking and a lot of issues over the last 10 years could have been addressed with some key animal studies.

“For efficacy and risk/benefit, I voted yes for both,” he said. “Had this been standard of care and only PROCEED II, I would have voted no, but I do think there are a lot of hearts that go in the bucket and this is a challenging population.”

More than a dozen physicians and patients spoke at the open public hearing about the potential for the device to expand donor heart utilization, including a recipient whose own father died while waiting on the transplant list. Only about 3 out of every 10 donated hearts are used for transplant. To ensure fair access, particularly for patients in rural areas, federal changes in 2020 mandate that organs be allocated to the sickest patients first.

Data showed that the OCS Heart System was associated with shorter waiting list times, compared with U.S. averages but longer preservation times than cold static preservation.

In all, 13% of accepted donor organs were subsequently turned down after OCS heart preservation. Lactate levels were cited as the principal reason for turn-down but, FDA officials said, the validity of using lactate as a marker for transplantability is unclear.

Pathologic analysis of OCS Heart turned-down donor hearts with stable antemortem hemodynamics, normal or near-normal anatomy and normal ventricular function by echocardiography, and autopsy findings of acute diffuse or multifocal myocardial damage “suggest that in an important proportion of cases the OCS Heart system did not provide effective organ preservation or its use caused severe myocardial damage to what might have been an acceptable graft for transplant,” said Andrew Farb, MD, chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Cardiovascular Devices.

Proposed indication

In the present PMA, the OCS Heart System is indicated for donor hearts with one or more of the following characteristics: an expected cross-clamp or ischemic time of at least 4 hours because of donor or recipient characteristics; or an expected total cross-clamp time of at least 2 hours plus one of the following risk factors: donor age 55 or older, history of cardiac arrest and downtime of at least 20 minutes, history of alcoholism, history of diabetes, donor ejection fraction of 40%-50%,history of left ventricular hypertrophy, and donor angiogram with luminal irregularities but no significant coronary artery disease

Several members voiced concern about “indication creep” should the device be approved by the FDA, and highlighted the 2-hour cross-clamp time plus wide-ranging risk factors.

“I’m a surgeon and I voted no on all three counts,” said Murray H. Kwon, MD, Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center. “As far as risk/benefit, if it was just limited to one group – the 4-hour plus – I would say yes, but if you’re going to tell me that there’s a risk/benefit for the 2-hour with the alcoholic, I don’t know how that was proved in anything.”

Dr. Kwon was also troubled by lack of proper controls and by the one quarter of patients who ended up on mechanical circulatory support in the first 30 days after transplant. “I find that highly aberrant.”

Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said the unmet need for patients with refractory, end-stage heart failure is challenging and quite emotional, but also voted no across the board, citing concerns about a lack of comparator in the EXPAND trials and overall out-of-body ischemic time.

“As it relates to risk/benefit, I thought long and hard about voting yes despite all the unknowns because of this emotion, but ultimately I voted no because of the secondary 2-hours plus alcoholism, diabetes, or minor coronary disease, in which the ischemic burden and ongoing lactate production concern me,” he said.

Although the panel decision is nonbinding, there was strong support from the committee members for a randomized, postapproval trial and more complete animal studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After more than 10 hours of intense debate, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel gave its support to a premarket approval application (PMA) for the TransMedics Organ Care System (OCS) Heart system.

The OCS Heart is a portable extracorporeal perfusion and monitoring system designed to keep a donor heart in a normothermic, beating state. The “heart in a box” technology allows donor hearts to be transported across longer distances than is possible with standard cold storage, which can safely preserve donor hearts for about 4 hours.

The Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee voted 12 to 5, with 1 abstention, that the benefits of the OCS Heart System outweigh its risks.

The panel voted in favor of the OCS Heart being effective (10 yes, 6 no, and 2 abstaining) and safe (9 yes, 7 no, 2 abstaining) but not without mixed feelings.

James Blankenship, MD, a cardiologist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, voted yes to all three questions but said: “If it had been compared to standard of care, I would have voted no to all three. But if it’s compared to getting an [left ventricular assist device] LVAD or not getting a heart at all, I would say the benefits outweigh the risks.”

Marc R. Katz, MD, chief of cardiothoracic surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, also gave universal support, noting that the rate of heart transplantations has been flat for years. “This is a big step forward toward being able to expand that number. Now all that said, it obviously was a less-than-perfect study and I do think there needs to be some constraints put on the utilization.”

The panel reviewed data from the single-arm OCS Heart EXPAND trial and associated EXPAND Continued Access Protocol (CAP), as well the sponsor’s first OCS Heart trial, PROCEED II.

EXPAND met its effectiveness endpoint, with 88% of donor hearts successfully transplanted, an 8% incidence of severe primary graft dysfunction (PGD) 24 hours after transplantation, and 94.6% survival at 30 days.

Data from 41 patients with 30-day follow-up in the ongoing EXPAND CAP show 91% of donor hearts were utilized, a 2.4% incidence of severe PGD, and 100% 30-day survival.

The sponsor and the FDA clashed over changes made to the trial after the PMA was submitted, the appropriateness of the effectiveness outcome, and claims by the FDA that there was substantial overlap in demographic characteristics between the extended criteria donor hearts in the EXPAND trials and the standard criteria donor hearts in PROCEED II.

TransMedics previously submitted a PMA based on PROCEED II but it noted in submitted documents that it was withdrawn because of “fundamental disagreements with FDA” on the interpretation of a post hoc analysis with United Network for Organ Sharing registry data that identified increased all-cause mortality risk but comparable cardiac-related mortality in patients with OCS hearts.

During the marathon hearing, FDA officials presented several post hoc analyses, including one stratified by donor inclusion criteria, in which 30-day survival estimates were worse in recipients of single-criterion organs than for those receiving donor organs with multiple inclusion criteria (85% vs. 91.4%). In a second analysis, 2-year point estimates of survival also trended lower with donor organs having only one extended criterion.

Reported EXPAND CAP 6- and 12-month survival estimates were 100% and 93%, respectively, which was higher than EXPAND (93% and 84%), but there was substantial censoring (>50%) at 6 months and beyond, FDA officials said.

When EXPAND and CAP data were pooled, modeled survival curves shifted upward but there was a substantial site effect, with a single site contributing 46% of data, which may affect generalizability of the results, they noted.

“I voted yes for safety, no for efficacy, and no for approval and I’d just like to say I found this to be the most difficult vote in my experience on this panel,” John Hirshfeld, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “I was very concerned that the PROCEED data suggests a possible harm, and in the absence of an interpretable comparator for the EXPAND trial, it’s really not possible to decide if there’s efficacy.”

Keith B. Allen, MD, director of surgical research at Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City (Mo.), said, “I voted no on safety; I’m not going to give the company a pass. I think their animal data was sorely lacking and a lot of issues over the last 10 years could have been addressed with some key animal studies.

“For efficacy and risk/benefit, I voted yes for both,” he said. “Had this been standard of care and only PROCEED II, I would have voted no, but I do think there are a lot of hearts that go in the bucket and this is a challenging population.”

More than a dozen physicians and patients spoke at the open public hearing about the potential for the device to expand donor heart utilization, including a recipient whose own father died while waiting on the transplant list. Only about 3 out of every 10 donated hearts are used for transplant. To ensure fair access, particularly for patients in rural areas, federal changes in 2020 mandate that organs be allocated to the sickest patients first.

Data showed that the OCS Heart System was associated with shorter waiting list times, compared with U.S. averages but longer preservation times than cold static preservation.

In all, 13% of accepted donor organs were subsequently turned down after OCS heart preservation. Lactate levels were cited as the principal reason for turn-down but, FDA officials said, the validity of using lactate as a marker for transplantability is unclear.

Pathologic analysis of OCS Heart turned-down donor hearts with stable antemortem hemodynamics, normal or near-normal anatomy and normal ventricular function by echocardiography, and autopsy findings of acute diffuse or multifocal myocardial damage “suggest that in an important proportion of cases the OCS Heart system did not provide effective organ preservation or its use caused severe myocardial damage to what might have been an acceptable graft for transplant,” said Andrew Farb, MD, chief medical officer of the FDA’s Office of Cardiovascular Devices.

Proposed indication

In the present PMA, the OCS Heart System is indicated for donor hearts with one or more of the following characteristics: an expected cross-clamp or ischemic time of at least 4 hours because of donor or recipient characteristics; or an expected total cross-clamp time of at least 2 hours plus one of the following risk factors: donor age 55 or older, history of cardiac arrest and downtime of at least 20 minutes, history of alcoholism, history of diabetes, donor ejection fraction of 40%-50%,history of left ventricular hypertrophy, and donor angiogram with luminal irregularities but no significant coronary artery disease

Several members voiced concern about “indication creep” should the device be approved by the FDA, and highlighted the 2-hour cross-clamp time plus wide-ranging risk factors.

“I’m a surgeon and I voted no on all three counts,” said Murray H. Kwon, MD, Ronald Reagan University of California, Los Angeles Medical Center. “As far as risk/benefit, if it was just limited to one group – the 4-hour plus – I would say yes, but if you’re going to tell me that there’s a risk/benefit for the 2-hour with the alcoholic, I don’t know how that was proved in anything.”

Dr. Kwon was also troubled by lack of proper controls and by the one quarter of patients who ended up on mechanical circulatory support in the first 30 days after transplant. “I find that highly aberrant.”

Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said the unmet need for patients with refractory, end-stage heart failure is challenging and quite emotional, but also voted no across the board, citing concerns about a lack of comparator in the EXPAND trials and overall out-of-body ischemic time.

“As it relates to risk/benefit, I thought long and hard about voting yes despite all the unknowns because of this emotion, but ultimately I voted no because of the secondary 2-hours plus alcoholism, diabetes, or minor coronary disease, in which the ischemic burden and ongoing lactate production concern me,” he said.

Although the panel decision is nonbinding, there was strong support from the committee members for a randomized, postapproval trial and more complete animal studies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Secukinumab brings high PASI 75 results in 6- to 17-year-olds with psoriasis

at 24 weeks of follow-up in an ongoing 4-year phase 2 clinical trial, Adam Reich, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

Secukinumab (Cosentyx), a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-17A, is widely approved for treatment of psoriasis in adults. In August 2020, the biologic received an expanded indication in Europe for treatment of 6- to 17-year-olds. Two phase 3 clinical trials are underway in an effort to gain a similar broadened indication in the United States to help address the high unmet need for new treatments for psoriasis in the pediatric population, said Dr. Reich, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of Rzeszow (Poland).

He reported on 84 pediatric patients participating in the open-label, phase 2, international study. They were randomized to one of two weight-based dosing regimens. Those in the low-dose arm received secukinumab dosed at 75 mg if they weighed less than 50 kg and 150 mg if they weighed more. In the high-dose arm, patients got secukinumab 75 mg if they weighed less than 25 kg, 150 mg if they weighed 25-50 kg, and 300 mg if they tipped the scales in excess of 50 kg.

The primary endpoint in the study was the week-12 rate of at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, or PASI 75. The rates were similar: 92.9% of patients in the high-dose arm achieved this endpoint, as did 90.5% in the low-dose arm. The PASI 90 rates were 83.3% and 78%, the PASI 100 rates were 61.9% and 54.8%, and clear or almost clear skin, as measured by the Investigator Global Assessment, was achieved in 88.7% of the high- and 85.7% of the low-dose groups. In addition,61.9% of those in the high-dose secukinumab group and 50% in the low-dose group had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index – indicating psoriasis has no impact on daily quality of life, he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

At week 24, roughly 95% of patients in both the low- and high-dose secukinumab groups had achieved PASI 75s, 88% reached a PASI 90 response, and 67% were at PASI 100. Nearly 60% of the low-dose and 70% of the high-dose groups had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in the two study arms. Of note, there was one case of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in the high-dose group, and one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis as well.

Discussant Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, said that, if secukinumab gets a pediatric indication from the Food and Drug Administration, as seems likely, it won’t alter his biologic treatment hierarchy.

“I treat a lot of kids with psoriasis. We have three approved drugs now in etanercept [Enbrel], ustekinumab [Stelara], and ixekizumab [Taltz]. My bias is still towards ustekinumab because it’s infrequently dosed and that’s a huge issue for children. You want to expose them to as few injections as possible, for obvious reasons: It’s easier for parents and other caregivers,” explained Dr. Strober, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Central Connecticut Dermatology, Cromwell, Conn.

“The other issue is in IL-17 inhibition there has been a slight signal of inflammatory bowel disease popping up in children getting these drugs, and therefore you need to screen patients in this age group very carefully – not only the patients themselves, but their family – for IBD risk. If there is any sign of that I would move the IL-17 inhibitors to the back of the line, compared to ustekinumab and etanercept. Ustekinumab is still clearly the one that I think has to be used first line,” he said.

Dr. Strober offered a final word of advice for his colleagues: “You can’t be afraid to treat children with biologic therapies. In fact, preferentially I would use a biologic therapy over methotrexate or light therapy, which is really difficult for children.”

Dr. Reich and Dr. Strober reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which markets secukinumab and funded the study.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

at 24 weeks of follow-up in an ongoing 4-year phase 2 clinical trial, Adam Reich, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

Secukinumab (Cosentyx), a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-17A, is widely approved for treatment of psoriasis in adults. In August 2020, the biologic received an expanded indication in Europe for treatment of 6- to 17-year-olds. Two phase 3 clinical trials are underway in an effort to gain a similar broadened indication in the United States to help address the high unmet need for new treatments for psoriasis in the pediatric population, said Dr. Reich, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of Rzeszow (Poland).

He reported on 84 pediatric patients participating in the open-label, phase 2, international study. They were randomized to one of two weight-based dosing regimens. Those in the low-dose arm received secukinumab dosed at 75 mg if they weighed less than 50 kg and 150 mg if they weighed more. In the high-dose arm, patients got secukinumab 75 mg if they weighed less than 25 kg, 150 mg if they weighed 25-50 kg, and 300 mg if they tipped the scales in excess of 50 kg.

The primary endpoint in the study was the week-12 rate of at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, or PASI 75. The rates were similar: 92.9% of patients in the high-dose arm achieved this endpoint, as did 90.5% in the low-dose arm. The PASI 90 rates were 83.3% and 78%, the PASI 100 rates were 61.9% and 54.8%, and clear or almost clear skin, as measured by the Investigator Global Assessment, was achieved in 88.7% of the high- and 85.7% of the low-dose groups. In addition,61.9% of those in the high-dose secukinumab group and 50% in the low-dose group had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index – indicating psoriasis has no impact on daily quality of life, he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

At week 24, roughly 95% of patients in both the low- and high-dose secukinumab groups had achieved PASI 75s, 88% reached a PASI 90 response, and 67% were at PASI 100. Nearly 60% of the low-dose and 70% of the high-dose groups had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in the two study arms. Of note, there was one case of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in the high-dose group, and one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis as well.

Discussant Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, said that, if secukinumab gets a pediatric indication from the Food and Drug Administration, as seems likely, it won’t alter his biologic treatment hierarchy.

“I treat a lot of kids with psoriasis. We have three approved drugs now in etanercept [Enbrel], ustekinumab [Stelara], and ixekizumab [Taltz]. My bias is still towards ustekinumab because it’s infrequently dosed and that’s a huge issue for children. You want to expose them to as few injections as possible, for obvious reasons: It’s easier for parents and other caregivers,” explained Dr. Strober, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Central Connecticut Dermatology, Cromwell, Conn.

“The other issue is in IL-17 inhibition there has been a slight signal of inflammatory bowel disease popping up in children getting these drugs, and therefore you need to screen patients in this age group very carefully – not only the patients themselves, but their family – for IBD risk. If there is any sign of that I would move the IL-17 inhibitors to the back of the line, compared to ustekinumab and etanercept. Ustekinumab is still clearly the one that I think has to be used first line,” he said.

Dr. Strober offered a final word of advice for his colleagues: “You can’t be afraid to treat children with biologic therapies. In fact, preferentially I would use a biologic therapy over methotrexate or light therapy, which is really difficult for children.”

Dr. Reich and Dr. Strober reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which markets secukinumab and funded the study.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

at 24 weeks of follow-up in an ongoing 4-year phase 2 clinical trial, Adam Reich, MD, PhD, reported at Innovations in Dermatology: Virtual Spring Conference 2021.

Secukinumab (Cosentyx), a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits interleukin-17A, is widely approved for treatment of psoriasis in adults. In August 2020, the biologic received an expanded indication in Europe for treatment of 6- to 17-year-olds. Two phase 3 clinical trials are underway in an effort to gain a similar broadened indication in the United States to help address the high unmet need for new treatments for psoriasis in the pediatric population, said Dr. Reich, professor and head of the department of dermatology at the University of Rzeszow (Poland).

He reported on 84 pediatric patients participating in the open-label, phase 2, international study. They were randomized to one of two weight-based dosing regimens. Those in the low-dose arm received secukinumab dosed at 75 mg if they weighed less than 50 kg and 150 mg if they weighed more. In the high-dose arm, patients got secukinumab 75 mg if they weighed less than 25 kg, 150 mg if they weighed 25-50 kg, and 300 mg if they tipped the scales in excess of 50 kg.

The primary endpoint in the study was the week-12 rate of at least a 75% improvement from baseline in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, or PASI 75. The rates were similar: 92.9% of patients in the high-dose arm achieved this endpoint, as did 90.5% in the low-dose arm. The PASI 90 rates were 83.3% and 78%, the PASI 100 rates were 61.9% and 54.8%, and clear or almost clear skin, as measured by the Investigator Global Assessment, was achieved in 88.7% of the high- and 85.7% of the low-dose groups. In addition,61.9% of those in the high-dose secukinumab group and 50% in the low-dose group had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index – indicating psoriasis has no impact on daily quality of life, he said at the conference sponsored by MedscapeLIVE! and the producers of the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar and Caribbean Dermatology Symposium.

At week 24, roughly 95% of patients in both the low- and high-dose secukinumab groups had achieved PASI 75s, 88% reached a PASI 90 response, and 67% were at PASI 100. Nearly 60% of the low-dose and 70% of the high-dose groups had a score of 0 or 1 on the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Treatment-emergent adverse event rates were similar in the two study arms. Of note, there was one case of new-onset inflammatory bowel disease in the high-dose group, and one case of vulvovaginal candidiasis as well.

Discussant Bruce E. Strober, MD, PhD, said that, if secukinumab gets a pediatric indication from the Food and Drug Administration, as seems likely, it won’t alter his biologic treatment hierarchy.

“I treat a lot of kids with psoriasis. We have three approved drugs now in etanercept [Enbrel], ustekinumab [Stelara], and ixekizumab [Taltz]. My bias is still towards ustekinumab because it’s infrequently dosed and that’s a huge issue for children. You want to expose them to as few injections as possible, for obvious reasons: It’s easier for parents and other caregivers,” explained Dr. Strober, a dermatologist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and Central Connecticut Dermatology, Cromwell, Conn.

“The other issue is in IL-17 inhibition there has been a slight signal of inflammatory bowel disease popping up in children getting these drugs, and therefore you need to screen patients in this age group very carefully – not only the patients themselves, but their family – for IBD risk. If there is any sign of that I would move the IL-17 inhibitors to the back of the line, compared to ustekinumab and etanercept. Ustekinumab is still clearly the one that I think has to be used first line,” he said.

Dr. Strober offered a final word of advice for his colleagues: “You can’t be afraid to treat children with biologic therapies. In fact, preferentially I would use a biologic therapy over methotrexate or light therapy, which is really difficult for children.”

Dr. Reich and Dr. Strober reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis, which markets secukinumab and funded the study.

MedscapeLIVE! and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM INNOVATIONS IN DERMATOLOGY

Deadly brain tumor: Survival extended by oncolytic virus product

This is a rapidly fatal form of brain cancer. Among historical control patients, the median overall survival was only 5.3 months.

The new results show a median overall survival of 12.2 months.

They come from a phase 1 trial conducted in 12 patients aged 7-18 years who had high-grade gliomas. All of the patients received the experimental therapy, dubbed G207, which was infused directly into the brain tumors.

“In our secondary objectives, we saw promising overall survival data ... [and] we saw that G207 turned immunologically ‘cold’ tumors to ‘hot,’ ” said lead investigator Gregory K. Friedman, MD, from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr. Friedman presented the new data at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract CT018). The study was also published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although the number of patients in the study was small, the data from this early trial look promising, commented Howard Kaufman, MD, director of the Oncolytic Virus Research Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“This is just a horrendous disease that hasn’t really responded to anything, so seeing some signs of benefit as well as a pretty tolerable safety profile is a very important observation that I think merits further investigation,” he said in an interview.

Engineered virus

G207 is an oncolytic form of HSV-1 created through genetic engineering in which a neurovirulence gene was deleted and viral nucleotide reductase was disabled. The engineered mutations prevent HSV-1 from infecting normal cells while allowing the virus to replicate in tumor cells.

The oncolytic virus product can be inoculated directly into tumors to circumvent the blood-brain barrier, and it preferentially infects neural tissue, making it ideal for treating brain tumors, the investigators explain.

One example of this type of product is already on the market. Talimogene laherparepvec is an oncolytic HSV-1 therapy that was approved in 2015 by the Food and Drug Administration for local treatment (i.e., injection directly into the skin lesion) of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with melanoma that recurs after initial surgery.

In their article, Dr. Friedman and colleagues summarized some of the data with G207 that “provided a strong rationale for conducting a trial involving children and adolescents.

“In addition to infecting and lysing tumor cells directly, G207 can reverse tumor immune evasion, increase cross-presentation of tumor antigens, and promote an antitumor immune response even in the absence of virus permissivity,” they wrote. “A single radiation dose enhances G207 efficacy in animal models by increasing viral replication and spread.”

In preclinical studies using tumor xenografts, pediatric brain tumors were 11-fold more sensitive to G207, compared with glioblastomas in adults.

The researchers hypothesized that intratumoral G207 would increase the amount of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and thereby convert immunologically “cold” pediatric brain tumors to “hot” and “inflamed” tumors.

Phase 1 trial

The phase 1 trial included four dose cohorts of children and adolescents with a pathologically proven malignant supratentorial brain tumor of at least 1 cm in diameter that had progressed after surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.

There were three patients in each dose cohort. One cohort received 107 plaque-forming units, the second received 108 PFU, the third received 107 PFU with 5 Gy of radiation, and the fourth received 108 PFU with 5 Gy radiation.

The patients first underwent stereotactic placement of up to four intratumoral catheters. The next day, they underwent infusion of the assigned PFU doses by controlled-rate infusion over 6 hours.

For the patients who received radiation, 5 Gy were administered to the gross tumor volume within 24 hours following G207 administration.

Among the 12 patients, tumors included 10 glioblastomas, one anaplastic astrocytoma, and one high-grade glioma not otherwise specified.

Responses (radiographic, neuropathologic, or clinical) occurred in 11 of the 12 patients.

Four patients were still alive 18 months after treatment, “which exceeds the life expectancy for newly diagnosed patients,” Dr. Friedman noted. Most patients die within 1 year of being diagnosed with pediatric glioma.

The investigators also found evidence to suggest that survival may be improved for patients who experience seroconversion after exposure to HSV-1 in comparison to patients with HSV-1 antibodies from prior HSV-1 infection. The median overall survival was 18.3 months for patients who experienced seroconversion, compared with 5.1 months for three patients who, at baseline, had IgG antibodies to HSV-1.

No dose-limiting toxicities or serious adverse events attributable to G207 occurred. There were 20 grade 1 adverse events that were potentially related to G207.

There was no evidence of peripheral G207 shedding or viremia, the investigators reported.

Radiation effect?

Commenting on the results in an interview, Dr. Kaufman noted that the sample size (12 patients) in this study was too small to determine whether the radiation received by patients in two of the four cohorts had any additive effect.

“Whether to move forward with virus alone or to add the radiation remains an open question that I don’t think was adequately answered,” he said.

Regarding the evidence suggesting that survival was better among patients who did not have antibodies to HSV-1 at baseline, Dr. Kaufman said, “We’ve looked at that in the melanoma population but haven’t seen any correlation there, so that’s interesting.”

The finding could be related to the fact that this was a pediatric population, or it could be related to the location of the tumors in the brain.

“It’s an interesting finding, and it suggests that, in future studies, they might want to select patients who are HSV seronegative up front,” he said.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues are currently planning a phase 2 trial of G207 with 5 Gy of radiation for children and adolescents with recurrent or progressive high-grade gliomas.

The study was supported by grants from the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, Cannonball Kids’ Cancer Foundation, the Rally Foundation for Childhood Cancer Research, Hyundai Hope on Wheels, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the Department of Defense, the Andrew McDonough B+ Foundation, and the Kaul Pediatric Research Institute; by NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grants to the University of Alabama at Birmingham and to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and by Kelsie’s Crew, Eli’s Block Party Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Eli Jackson Foundation, Jaxon’s FROG Foundation, Battle for a Cure Foundation, and Sandcastle Kids. Dr. Friedman has received grants/support from the organizations listed above, as well as from Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Dr. Kaufman disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a rapidly fatal form of brain cancer. Among historical control patients, the median overall survival was only 5.3 months.

The new results show a median overall survival of 12.2 months.

They come from a phase 1 trial conducted in 12 patients aged 7-18 years who had high-grade gliomas. All of the patients received the experimental therapy, dubbed G207, which was infused directly into the brain tumors.

“In our secondary objectives, we saw promising overall survival data ... [and] we saw that G207 turned immunologically ‘cold’ tumors to ‘hot,’ ” said lead investigator Gregory K. Friedman, MD, from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr. Friedman presented the new data at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract CT018). The study was also published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although the number of patients in the study was small, the data from this early trial look promising, commented Howard Kaufman, MD, director of the Oncolytic Virus Research Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“This is just a horrendous disease that hasn’t really responded to anything, so seeing some signs of benefit as well as a pretty tolerable safety profile is a very important observation that I think merits further investigation,” he said in an interview.

Engineered virus

G207 is an oncolytic form of HSV-1 created through genetic engineering in which a neurovirulence gene was deleted and viral nucleotide reductase was disabled. The engineered mutations prevent HSV-1 from infecting normal cells while allowing the virus to replicate in tumor cells.

The oncolytic virus product can be inoculated directly into tumors to circumvent the blood-brain barrier, and it preferentially infects neural tissue, making it ideal for treating brain tumors, the investigators explain.

One example of this type of product is already on the market. Talimogene laherparepvec is an oncolytic HSV-1 therapy that was approved in 2015 by the Food and Drug Administration for local treatment (i.e., injection directly into the skin lesion) of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with melanoma that recurs after initial surgery.

In their article, Dr. Friedman and colleagues summarized some of the data with G207 that “provided a strong rationale for conducting a trial involving children and adolescents.

“In addition to infecting and lysing tumor cells directly, G207 can reverse tumor immune evasion, increase cross-presentation of tumor antigens, and promote an antitumor immune response even in the absence of virus permissivity,” they wrote. “A single radiation dose enhances G207 efficacy in animal models by increasing viral replication and spread.”

In preclinical studies using tumor xenografts, pediatric brain tumors were 11-fold more sensitive to G207, compared with glioblastomas in adults.

The researchers hypothesized that intratumoral G207 would increase the amount of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and thereby convert immunologically “cold” pediatric brain tumors to “hot” and “inflamed” tumors.

Phase 1 trial

The phase 1 trial included four dose cohorts of children and adolescents with a pathologically proven malignant supratentorial brain tumor of at least 1 cm in diameter that had progressed after surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.

There were three patients in each dose cohort. One cohort received 107 plaque-forming units, the second received 108 PFU, the third received 107 PFU with 5 Gy of radiation, and the fourth received 108 PFU with 5 Gy radiation.

The patients first underwent stereotactic placement of up to four intratumoral catheters. The next day, they underwent infusion of the assigned PFU doses by controlled-rate infusion over 6 hours.

For the patients who received radiation, 5 Gy were administered to the gross tumor volume within 24 hours following G207 administration.

Among the 12 patients, tumors included 10 glioblastomas, one anaplastic astrocytoma, and one high-grade glioma not otherwise specified.

Responses (radiographic, neuropathologic, or clinical) occurred in 11 of the 12 patients.

Four patients were still alive 18 months after treatment, “which exceeds the life expectancy for newly diagnosed patients,” Dr. Friedman noted. Most patients die within 1 year of being diagnosed with pediatric glioma.

The investigators also found evidence to suggest that survival may be improved for patients who experience seroconversion after exposure to HSV-1 in comparison to patients with HSV-1 antibodies from prior HSV-1 infection. The median overall survival was 18.3 months for patients who experienced seroconversion, compared with 5.1 months for three patients who, at baseline, had IgG antibodies to HSV-1.

No dose-limiting toxicities or serious adverse events attributable to G207 occurred. There were 20 grade 1 adverse events that were potentially related to G207.

There was no evidence of peripheral G207 shedding or viremia, the investigators reported.

Radiation effect?

Commenting on the results in an interview, Dr. Kaufman noted that the sample size (12 patients) in this study was too small to determine whether the radiation received by patients in two of the four cohorts had any additive effect.

“Whether to move forward with virus alone or to add the radiation remains an open question that I don’t think was adequately answered,” he said.

Regarding the evidence suggesting that survival was better among patients who did not have antibodies to HSV-1 at baseline, Dr. Kaufman said, “We’ve looked at that in the melanoma population but haven’t seen any correlation there, so that’s interesting.”

The finding could be related to the fact that this was a pediatric population, or it could be related to the location of the tumors in the brain.

“It’s an interesting finding, and it suggests that, in future studies, they might want to select patients who are HSV seronegative up front,” he said.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues are currently planning a phase 2 trial of G207 with 5 Gy of radiation for children and adolescents with recurrent or progressive high-grade gliomas.

The study was supported by grants from the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, Cannonball Kids’ Cancer Foundation, the Rally Foundation for Childhood Cancer Research, Hyundai Hope on Wheels, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the Department of Defense, the Andrew McDonough B+ Foundation, and the Kaul Pediatric Research Institute; by NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grants to the University of Alabama at Birmingham and to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and by Kelsie’s Crew, Eli’s Block Party Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Eli Jackson Foundation, Jaxon’s FROG Foundation, Battle for a Cure Foundation, and Sandcastle Kids. Dr. Friedman has received grants/support from the organizations listed above, as well as from Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Dr. Kaufman disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This is a rapidly fatal form of brain cancer. Among historical control patients, the median overall survival was only 5.3 months.

The new results show a median overall survival of 12.2 months.

They come from a phase 1 trial conducted in 12 patients aged 7-18 years who had high-grade gliomas. All of the patients received the experimental therapy, dubbed G207, which was infused directly into the brain tumors.

“In our secondary objectives, we saw promising overall survival data ... [and] we saw that G207 turned immunologically ‘cold’ tumors to ‘hot,’ ” said lead investigator Gregory K. Friedman, MD, from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dr. Friedman presented the new data at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract CT018). The study was also published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although the number of patients in the study was small, the data from this early trial look promising, commented Howard Kaufman, MD, director of the Oncolytic Virus Research Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“This is just a horrendous disease that hasn’t really responded to anything, so seeing some signs of benefit as well as a pretty tolerable safety profile is a very important observation that I think merits further investigation,” he said in an interview.

Engineered virus

G207 is an oncolytic form of HSV-1 created through genetic engineering in which a neurovirulence gene was deleted and viral nucleotide reductase was disabled. The engineered mutations prevent HSV-1 from infecting normal cells while allowing the virus to replicate in tumor cells.

The oncolytic virus product can be inoculated directly into tumors to circumvent the blood-brain barrier, and it preferentially infects neural tissue, making it ideal for treating brain tumors, the investigators explain.

One example of this type of product is already on the market. Talimogene laherparepvec is an oncolytic HSV-1 therapy that was approved in 2015 by the Food and Drug Administration for local treatment (i.e., injection directly into the skin lesion) of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with melanoma that recurs after initial surgery.

In their article, Dr. Friedman and colleagues summarized some of the data with G207 that “provided a strong rationale for conducting a trial involving children and adolescents.

“In addition to infecting and lysing tumor cells directly, G207 can reverse tumor immune evasion, increase cross-presentation of tumor antigens, and promote an antitumor immune response even in the absence of virus permissivity,” they wrote. “A single radiation dose enhances G207 efficacy in animal models by increasing viral replication and spread.”

In preclinical studies using tumor xenografts, pediatric brain tumors were 11-fold more sensitive to G207, compared with glioblastomas in adults.

The researchers hypothesized that intratumoral G207 would increase the amount of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and thereby convert immunologically “cold” pediatric brain tumors to “hot” and “inflamed” tumors.

Phase 1 trial

The phase 1 trial included four dose cohorts of children and adolescents with a pathologically proven malignant supratentorial brain tumor of at least 1 cm in diameter that had progressed after surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy.

There were three patients in each dose cohort. One cohort received 107 plaque-forming units, the second received 108 PFU, the third received 107 PFU with 5 Gy of radiation, and the fourth received 108 PFU with 5 Gy radiation.

The patients first underwent stereotactic placement of up to four intratumoral catheters. The next day, they underwent infusion of the assigned PFU doses by controlled-rate infusion over 6 hours.

For the patients who received radiation, 5 Gy were administered to the gross tumor volume within 24 hours following G207 administration.

Among the 12 patients, tumors included 10 glioblastomas, one anaplastic astrocytoma, and one high-grade glioma not otherwise specified.

Responses (radiographic, neuropathologic, or clinical) occurred in 11 of the 12 patients.

Four patients were still alive 18 months after treatment, “which exceeds the life expectancy for newly diagnosed patients,” Dr. Friedman noted. Most patients die within 1 year of being diagnosed with pediatric glioma.

The investigators also found evidence to suggest that survival may be improved for patients who experience seroconversion after exposure to HSV-1 in comparison to patients with HSV-1 antibodies from prior HSV-1 infection. The median overall survival was 18.3 months for patients who experienced seroconversion, compared with 5.1 months for three patients who, at baseline, had IgG antibodies to HSV-1.

No dose-limiting toxicities or serious adverse events attributable to G207 occurred. There were 20 grade 1 adverse events that were potentially related to G207.

There was no evidence of peripheral G207 shedding or viremia, the investigators reported.

Radiation effect?

Commenting on the results in an interview, Dr. Kaufman noted that the sample size (12 patients) in this study was too small to determine whether the radiation received by patients in two of the four cohorts had any additive effect.

“Whether to move forward with virus alone or to add the radiation remains an open question that I don’t think was adequately answered,” he said.

Regarding the evidence suggesting that survival was better among patients who did not have antibodies to HSV-1 at baseline, Dr. Kaufman said, “We’ve looked at that in the melanoma population but haven’t seen any correlation there, so that’s interesting.”

The finding could be related to the fact that this was a pediatric population, or it could be related to the location of the tumors in the brain.

“It’s an interesting finding, and it suggests that, in future studies, they might want to select patients who are HSV seronegative up front,” he said.

Dr. Friedman and colleagues are currently planning a phase 2 trial of G207 with 5 Gy of radiation for children and adolescents with recurrent or progressive high-grade gliomas.

The study was supported by grants from the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, Cannonball Kids’ Cancer Foundation, the Rally Foundation for Childhood Cancer Research, Hyundai Hope on Wheels, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the Department of Defense, the Andrew McDonough B+ Foundation, and the Kaul Pediatric Research Institute; by NIH/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grants to the University of Alabama at Birmingham and to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and by Kelsie’s Crew, Eli’s Block Party Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Eli Jackson Foundation, Jaxon’s FROG Foundation, Battle for a Cure Foundation, and Sandcastle Kids. Dr. Friedman has received grants/support from the organizations listed above, as well as from Eli Lilly and Pfizer. Dr. Kaufman disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AACR 2021

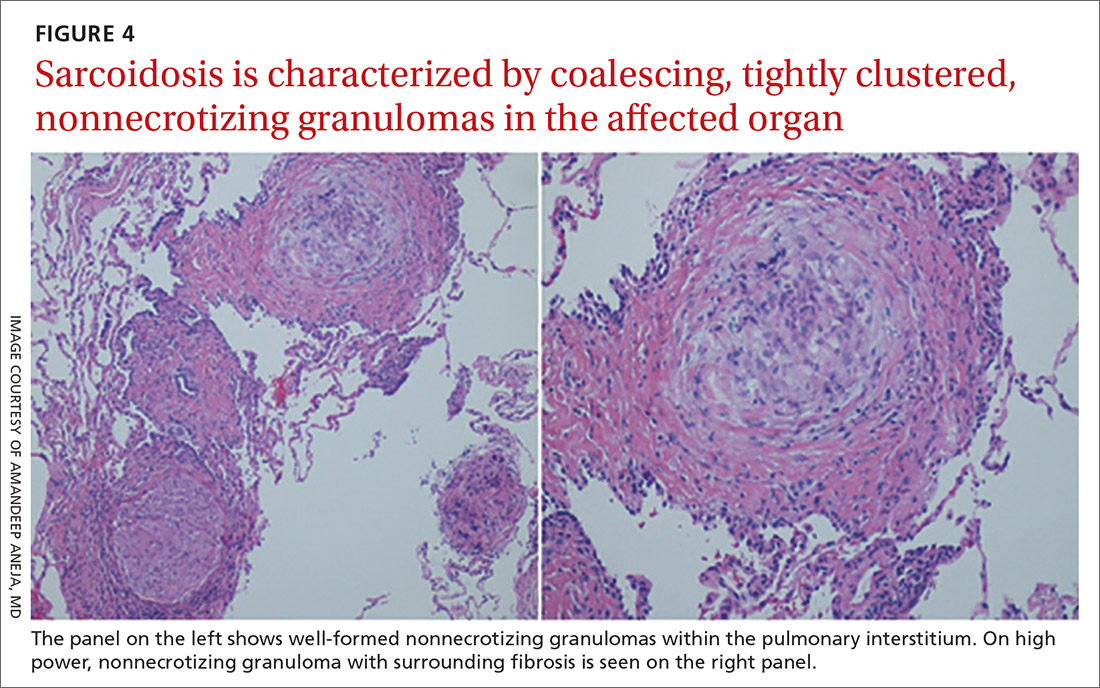

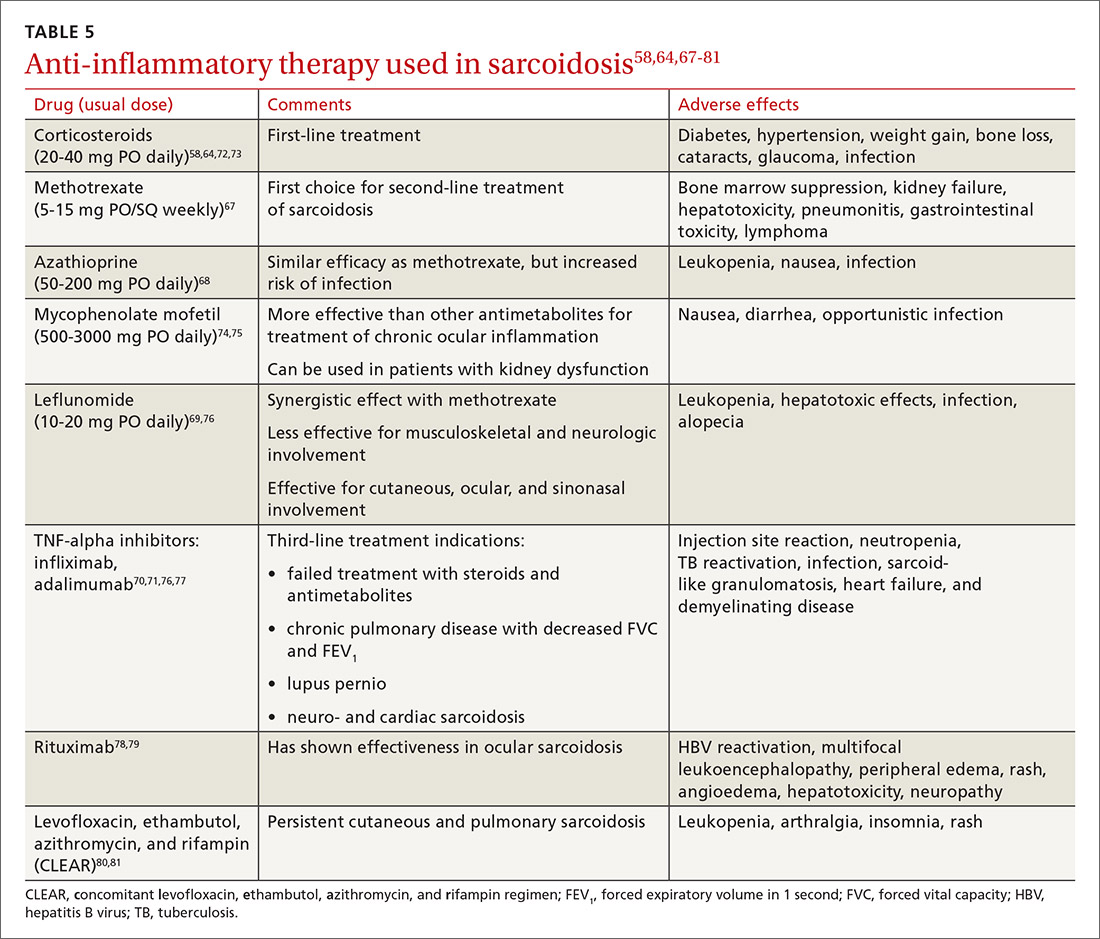

Sarcoidosis: An FP’s primer on an enigmatic disease

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unclear etiology that primarily affects the lungs. It can occur at any age but usually develops before the age of 50 years, with an initial peak incidence at 20 to 29 years and a second peak incidence after 50 years of age, especially among women in Scandinavia and Japan.1 Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups throughout the world, but differences based on race, sex, and geography are noted.1

The highest rates are reported in northern European and African-American individuals, particularly in women.1,2 The adjusted annual incidence of sarcoidosis among African Americans is approximately 3 times that among White Americans3 and is more likely to be chronic and fatal in African Americans.3 The disease can be familial with a possible recessive inheritance mode with incomplete penetrance.4 Risk of sarcoidosis in monozygotic twins appears to be 80 times greater than that in the general population, which supports genetic factors accounting for two-thirds of disease susceptibility.5

Likely factors in the development of sarcoidosis

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, but we have insights into its pathogenesis and potential triggers.1,6-9 Genes involved are being identified: class I and II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules are most consistently associated with risk of sarcoidosis. Environmental exposures can activate the innate immune system and precondition a susceptible individual to react to potential causative antigens in a highly polarized, antigen-specific Th1 immune response. The epithelioid granulomatous response involves local proinflammatory cytokine production and enhanced T-cell immunity at sites of inflammation.10 Granulomas generally form to confine pathogens, restrict inflammation, and protect surrounding tissue.11-13

ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis) identified several environmental exposures such as chemicals used in the agriculture industry, mold or mildew, and musty odors at work.14 Tobacco use was not associated with sarcoidosis.14 Recent studies have shown positive associations with service in the US Navy,15 metal working,16 firefighting,17 the handling of building supplies,18 and onsite exposure while assisting in rescue efforts at the World Trade Center disaster.19 Other data support the likelihood that specific environmental exposures associated with microbe-rich environments modestly increase the risk of sarcoidosis.14 Mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA and RNA are potentially associated with sarcoidosis.20

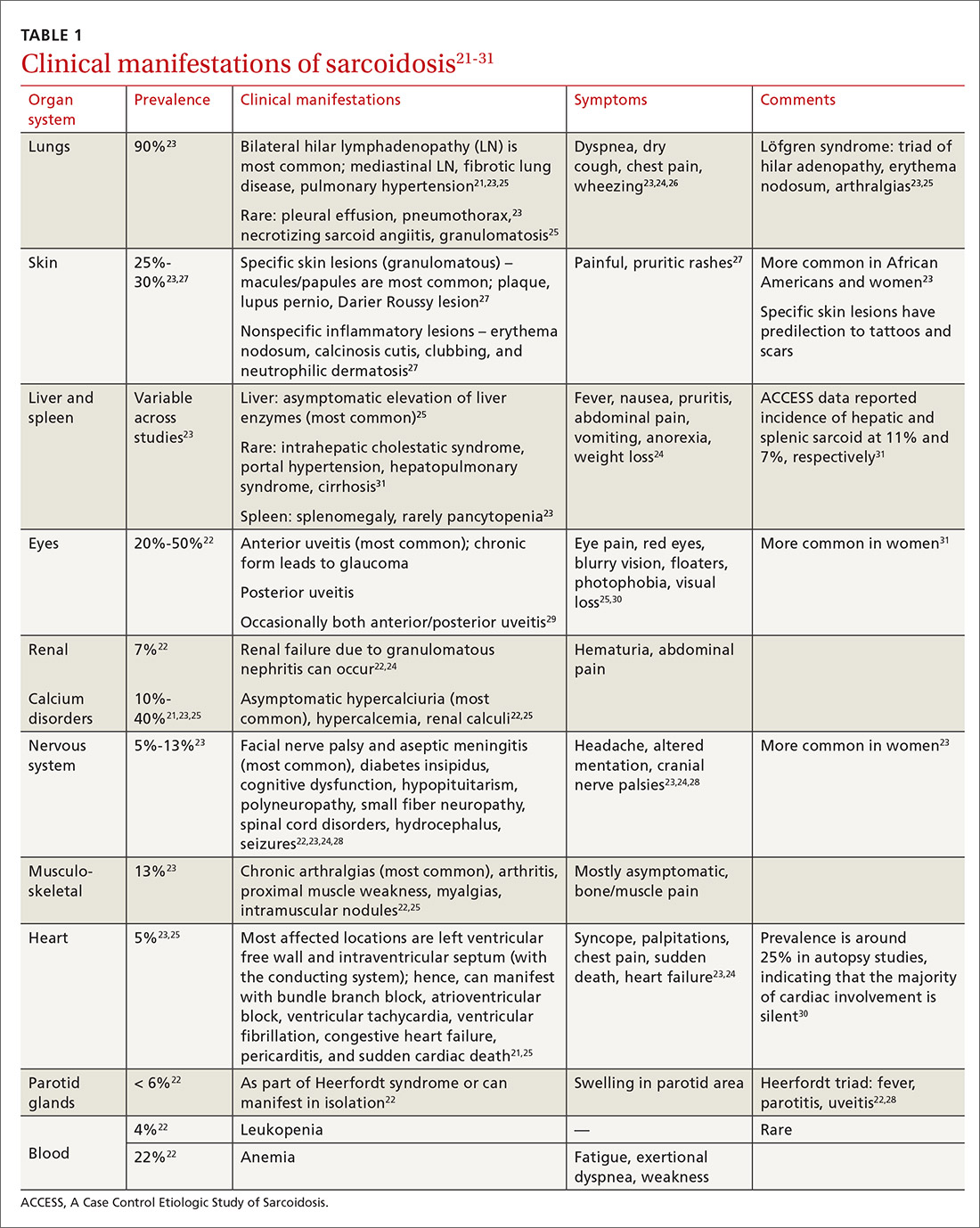

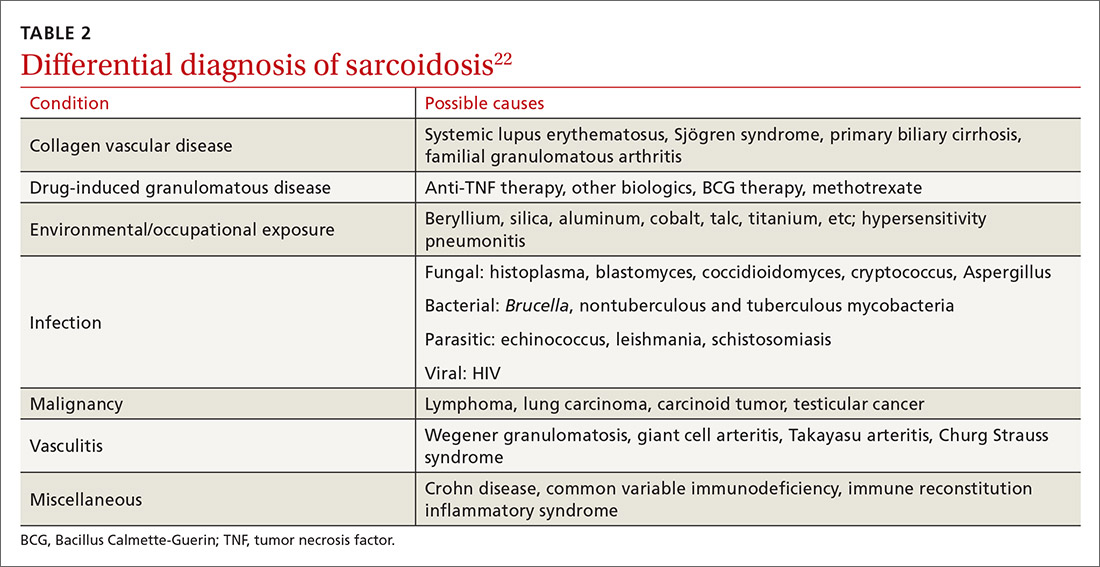

Clinical manifestations are nonspecific

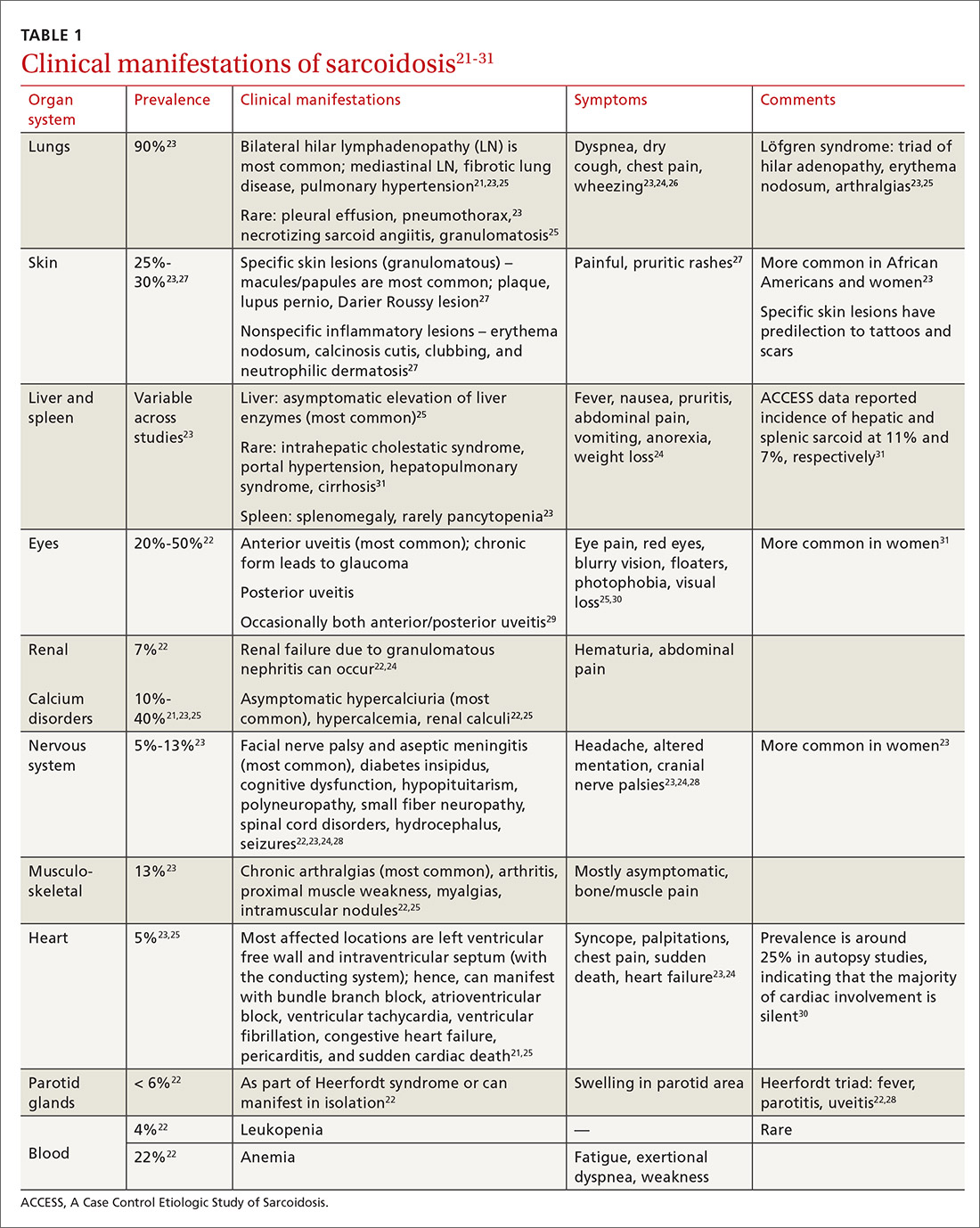

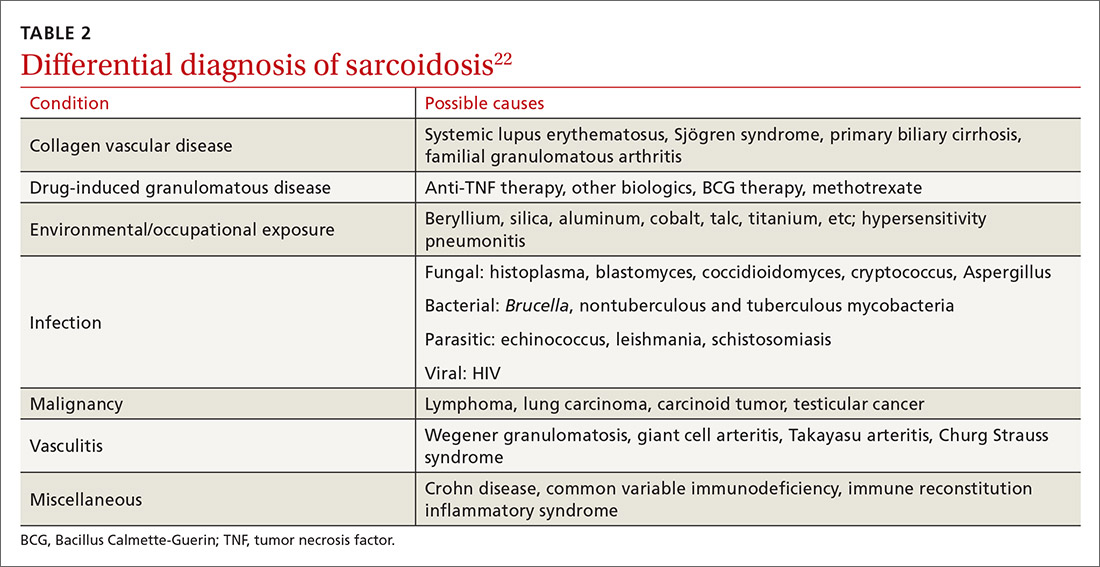

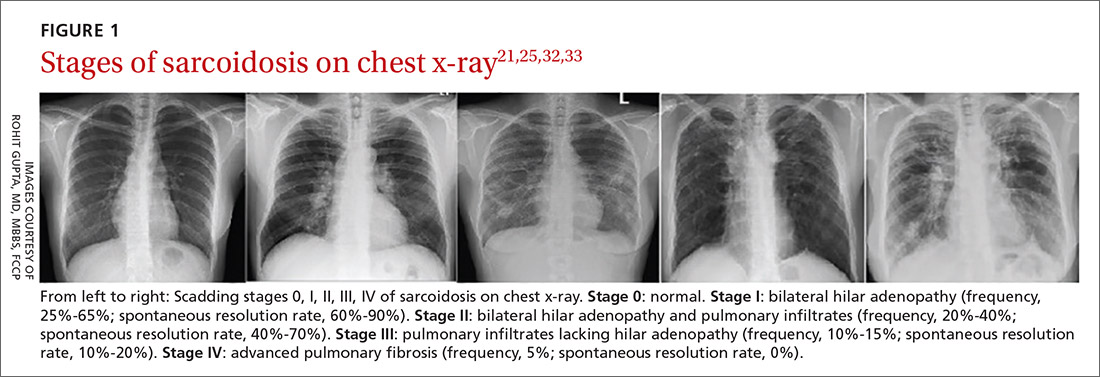

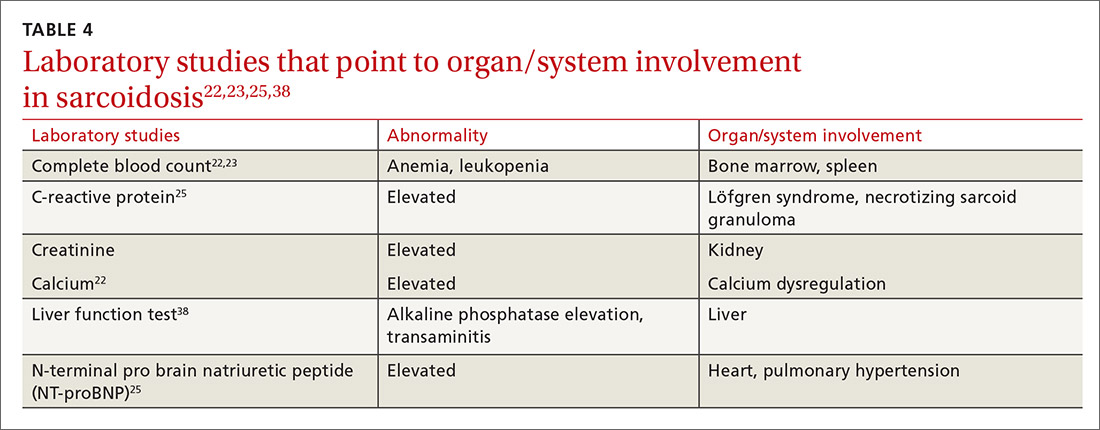

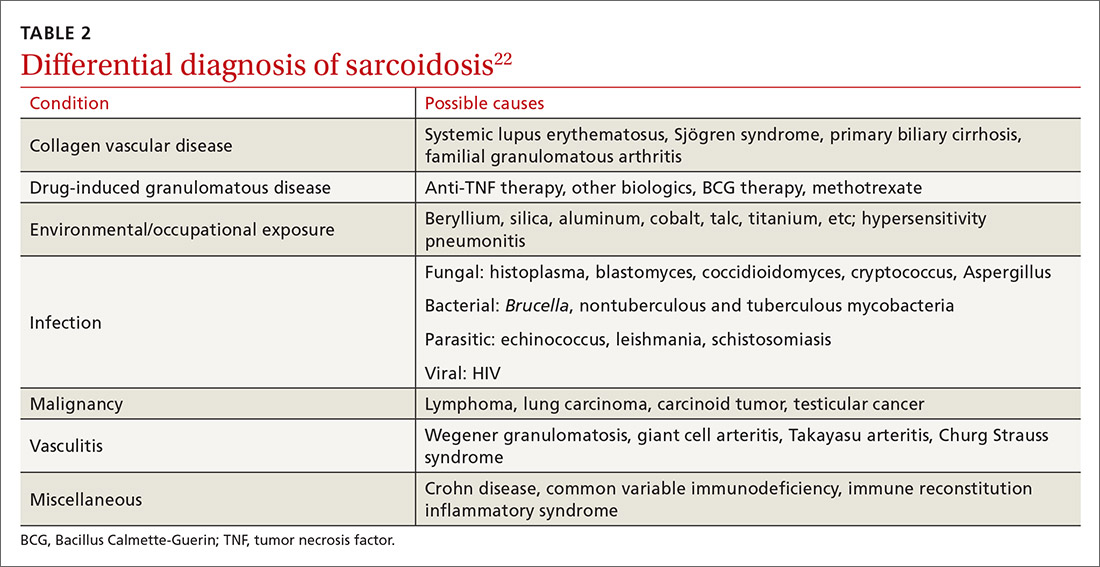

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be difficult and delayed due to diverse organ involvement and nonspecific presentations. TABLE 121-31 shows the diverse manifestations in a patient with suspected sarcoidosis. Around 50% of the patients are asymptomatic.23,24 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, starting with a detailed history to rule out infections, occupational or environmental exposures, malignancies, and other possible disorders (TABLE 2).22

Diagnostic work-up

Radiologic studies