User login

COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider: An update

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

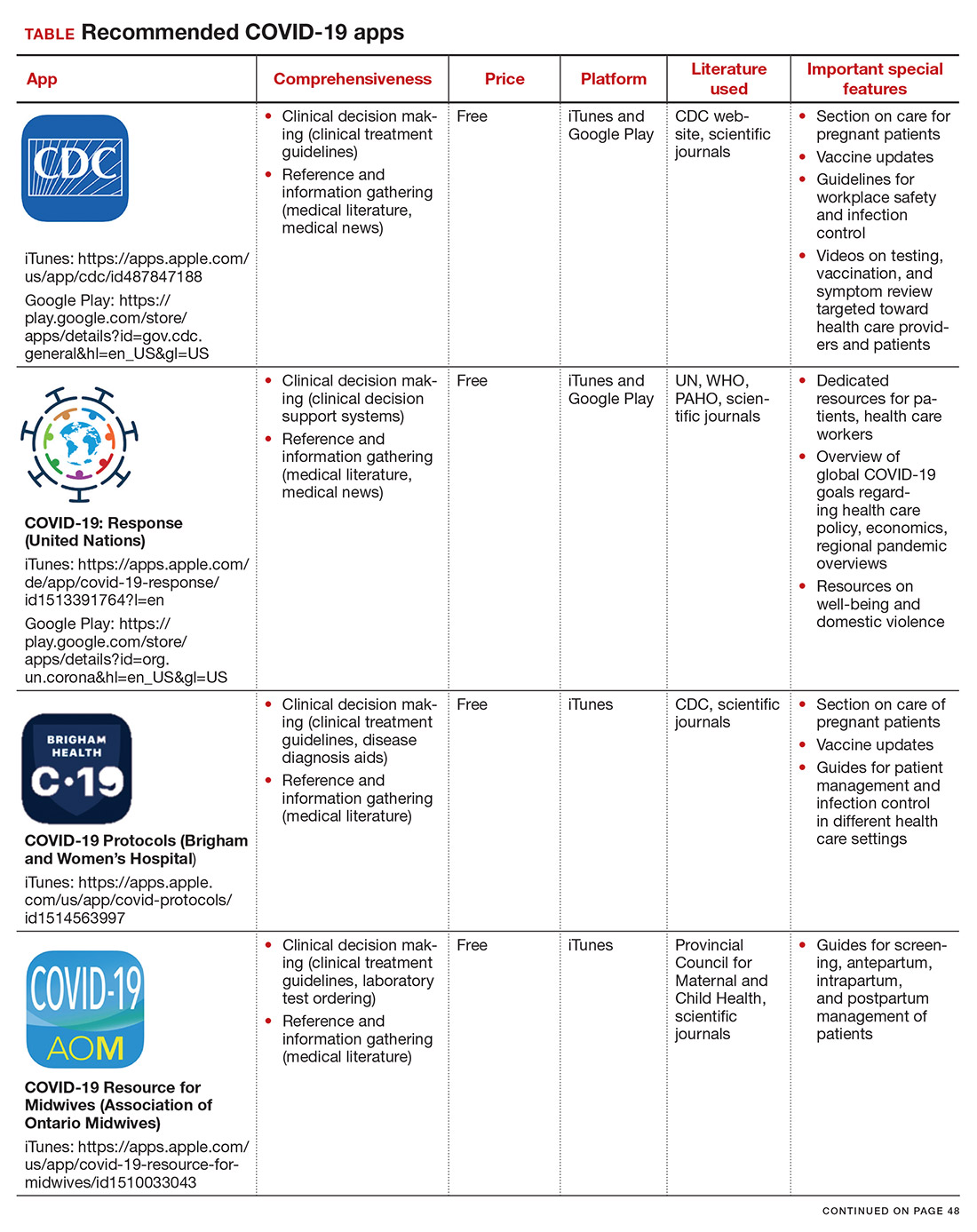

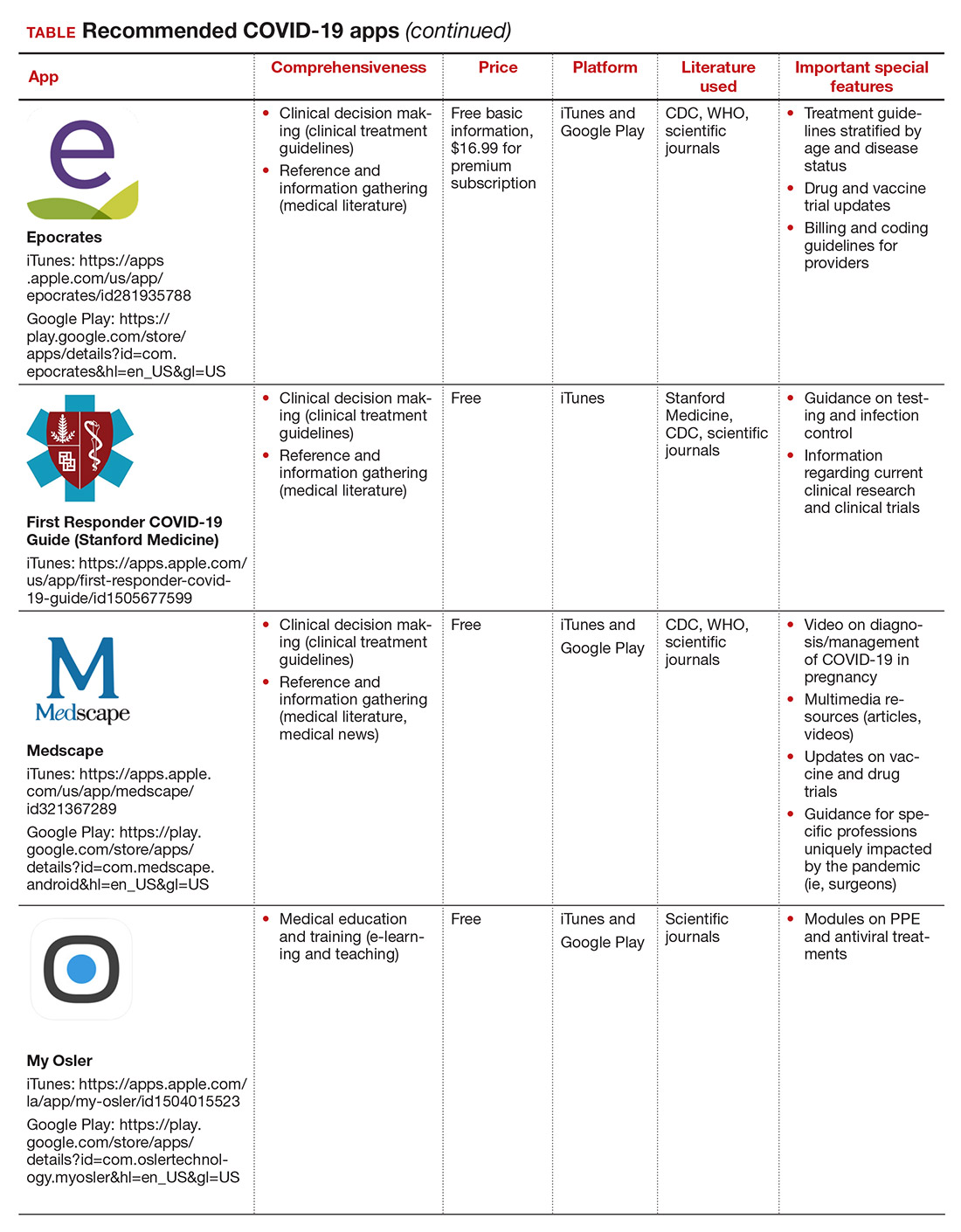

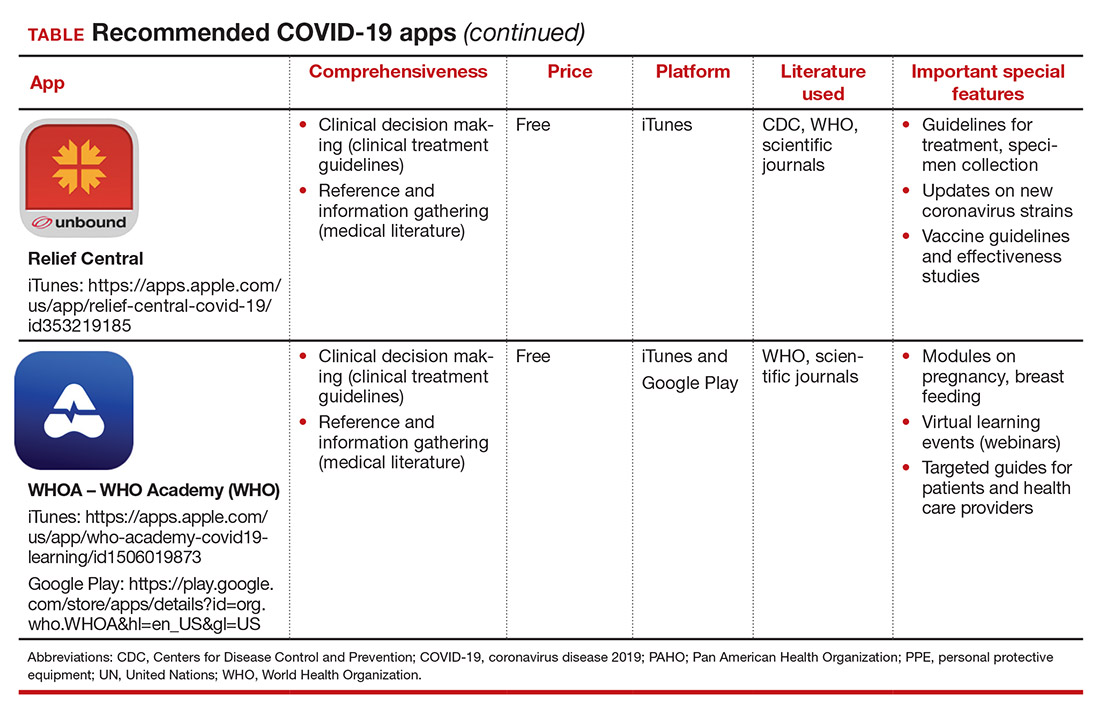

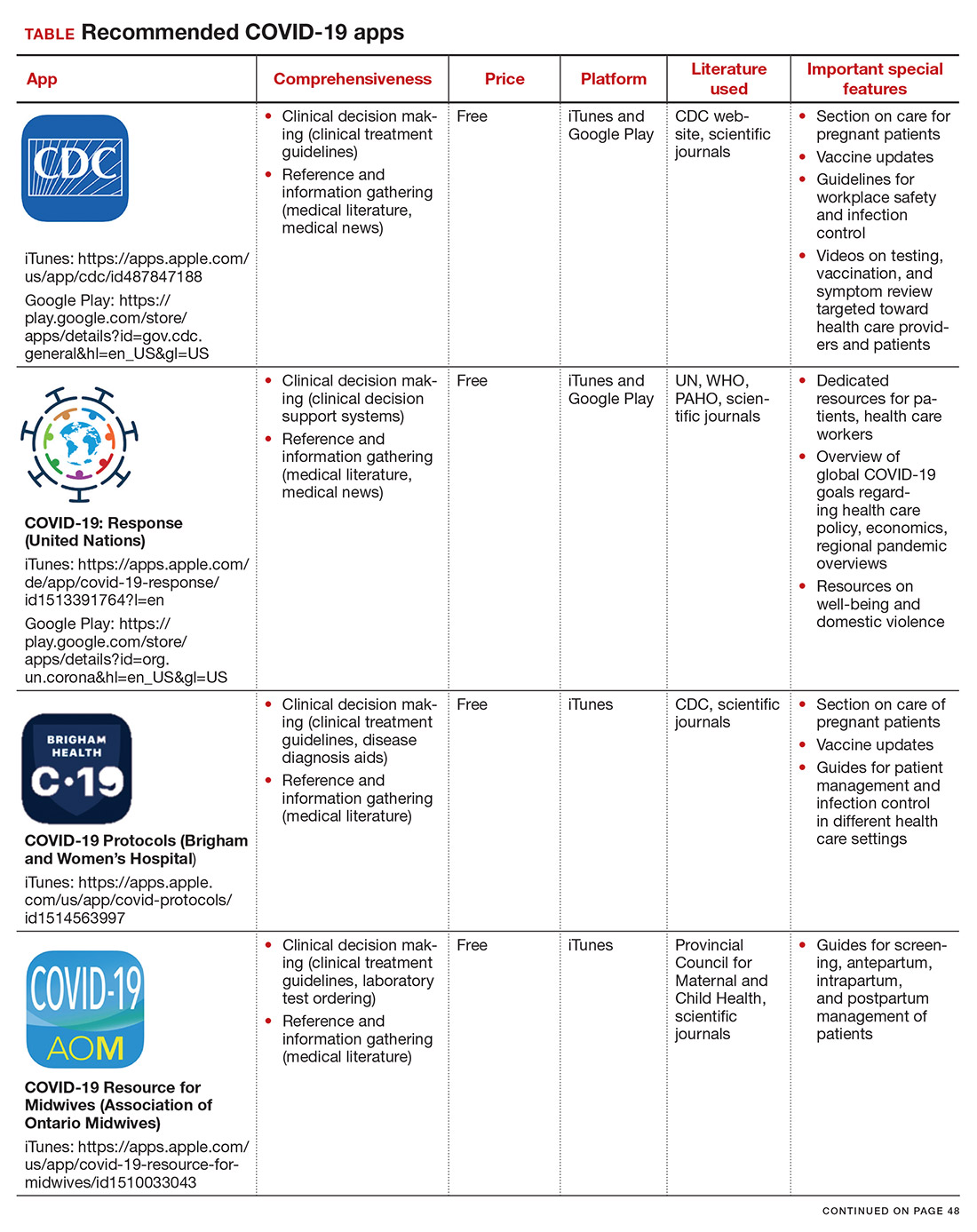

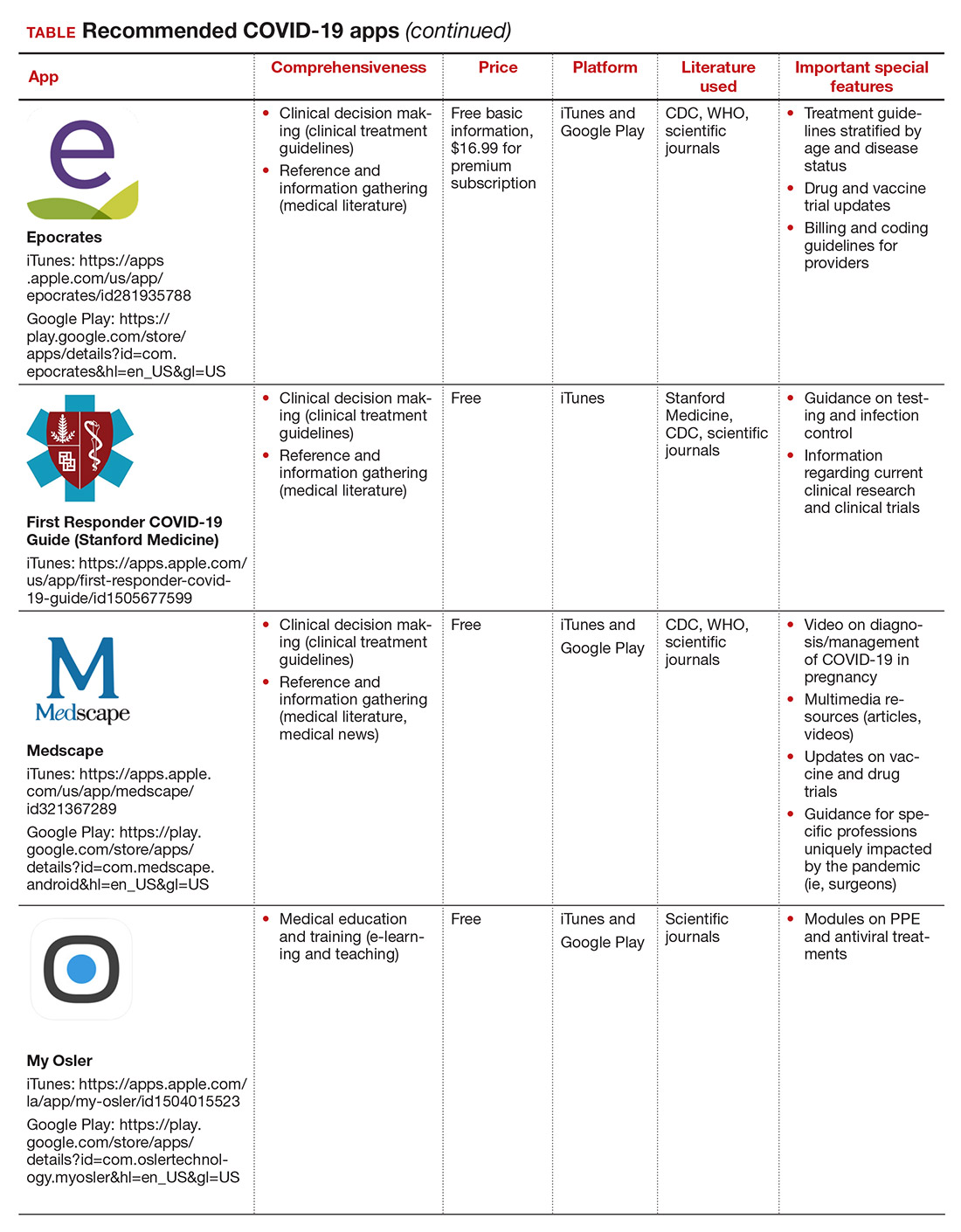

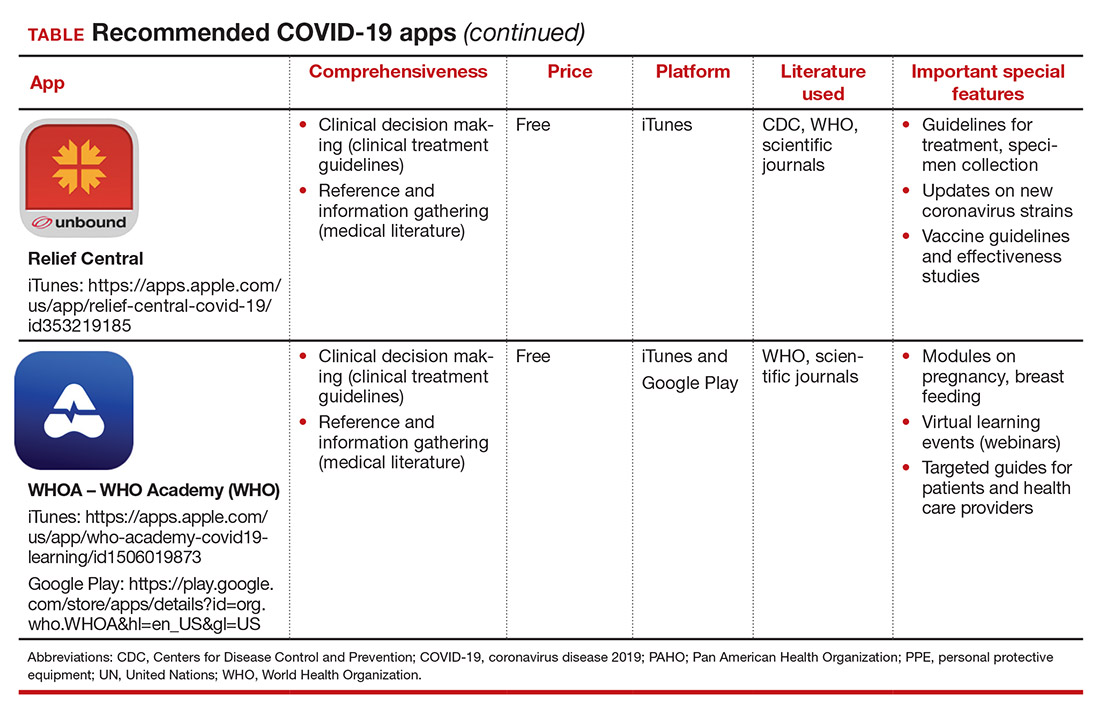

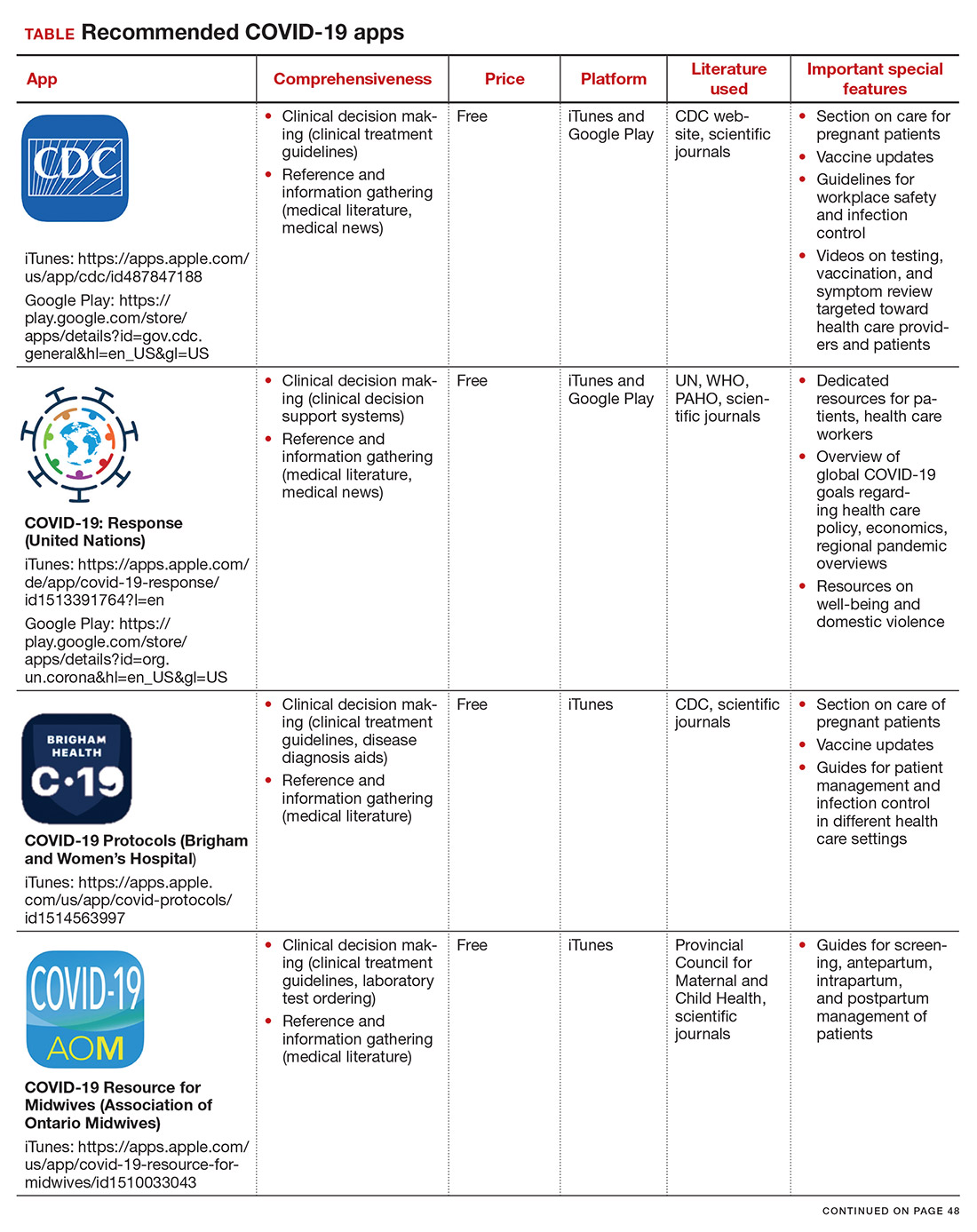

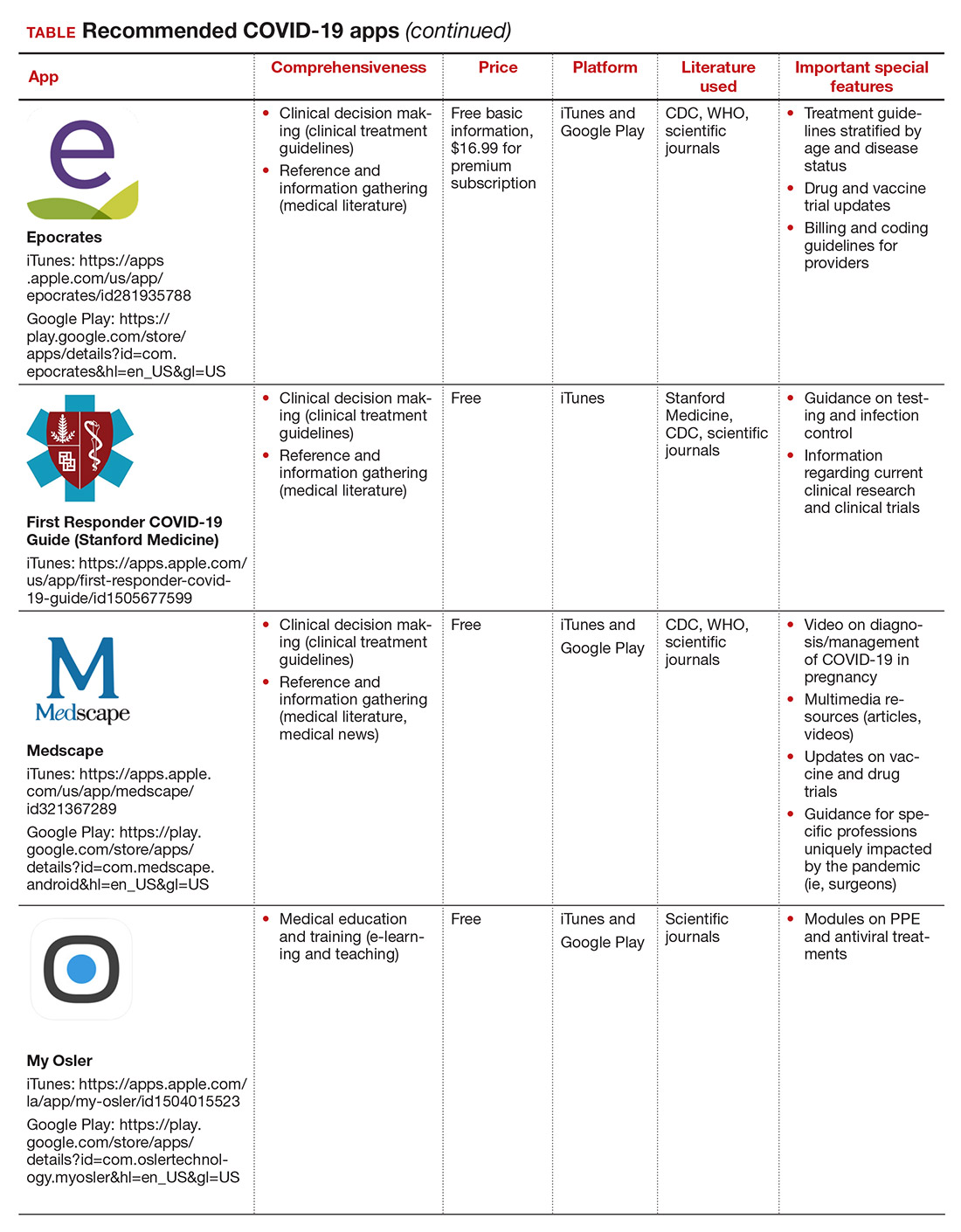

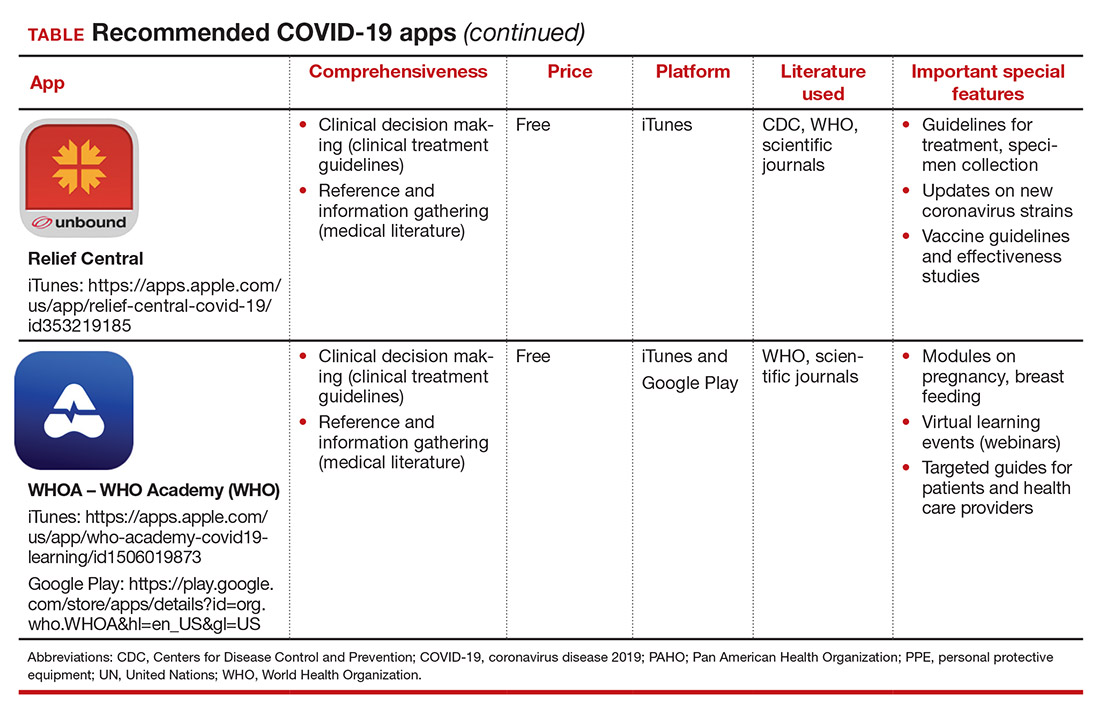

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

More than one year after COVID-19 was declared a worldwide pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, the disease continues to persist, infecting more than 110 million individuals to date globally.1 As new information emerges about the coronavirus, the literature on diagnosis and management also has grown exponentially over the last year, including specific guidance for obstetric populations. With abundant information available to health care providers, COVID-19 mobile apps have the advantage of summarizing and presenting information in an organized and easily accessible manner.2

This updated review expands on a previous article by Bogaert and Chen at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Using the same methodology, in March 2021 we searched the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores using the term “COVID.” The search yielded 230 unique applications available for download. We excluded apps that were primarily developed as geographic area-specific case trackers or personal symptom trackers (193), those that provide telemedicine services (7), and nonmedical apps or ones published in a language other than English (20).

Here, we focus on the 3 mobile apps previously discussed (CDC, My Osler, and Relief Central) and 7 additional apps (TABLE). Most summarize information on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus, and several also provide information on the COVID-19 vaccine. One app (COVID-19 Resource for Midwives) is specifically designed for obstetric providers, and 4 others (CDC, COVID-19 Protocols, Medscape, and WHO Academy) contain information on specific guidance for obstetric and gynecologic patient populations.

Each app was evaluated based on a condensed version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and special features).4

We hope that these mobile apps will assist the ObGyn health care provider in continuing to care for patients during this pandemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

- World Health Organization. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

2. Kondylakis H, Katehakis DG, Kouroubali A, et al. COVID-19 mobile apps: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e23170.

3. Bogaert K, Chen KT. COVID-19 apps for the ObGyn health care provider. OBG Manag. 2020; 32(5):44, 46.

4. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

Study IDs most common lingering symptoms 8 months after mild COVID

Loss of smell, loss of taste, dyspnea, and fatigue are the four most common symptoms that health care professionals in Sweden report 8 months after mild COVID-19 illness, new evidence reveals.

according to the study.

“We see that a substantial portion of health care workers suffer from long-term symptoms after mild COVID-19,” senior author Charlotte Thålin, MD, PhD, said in an interview. She added that loss of smell and taste “may seem trivial, but have a negative impact on work, social, and home life in the long run.”

The study is noteworthy not only for tracking the COVID-19-related experiences of health care workers over time, but also for what it did not find. There was no increased prevalence of cognitive issues – including memory or concentration – that others have linked to what’s often called long-haul COVID-19.

The research letter was published online April 7, 2021, in JAMA.

“Even if you are young and previously healthy, a mild COVID-19 infection may result in long-term consequences,” said Dr. Thålin, from the department of clinical sciences at Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The researchers did not observe an increased risk for long-term symptoms after asymptomatic COVID-19.

Adding to existing evidence

This research letter “adds to the growing body of literature showing that people recovering from COVID have reported a diverse array of symptoms lasting for months after initial infection,” Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, said in an interview. She is physician faculty lead at the University of California, San Francisco Post-COVID OPTIMAL Clinic.

Previous research revealed severe long-term symptoms, including heart palpitations and neurologic impairments, among people hospitalized with COVID-19. However, “there is limited data on the long-term effects after mild COVID-19, and these studies are often hampered by selection bias and without proper control groups,” Dr. Thålin said.

The absence of these more severe symptoms after mild COVID-19 is “reassuring,” she added.

The current findings are part of the ongoing COMMUNITY (COVID-19 Biomarker and Immunity) study looking at long-term immunity. Health care professionals enrolled in the research between April 15 and May 8, 2020, and have initial blood tests repeated every 4 months.

Dr. Thålin, lead author Sebastian Havervall, MD, and their colleagues compared symptom reporting between 323 hospital employees who had mild COVID-19 at least 8 months earlier with 1,072 employees who did not have COVID-19 throughout the study.

The results show that 26% of those who had COVID-19 previously had at least one moderate to severe symptom that lasted more than 2 months, compared with 9% in the control group.

The group with a history of mild COVID-19 was a median 43 years old and 83% were women. The controls were a median 47 years old and 86% were women.

“These data mirror what we have seen across long-term cohorts of patients with COVID-19 infection. Notably, mild illness among previously healthy individuals may be associated with long-term persistent symptoms,” Sarah Jolley, MD, a pulmonologist specializing in critical care at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and director of the Post-COVID Clinic, said in an interview.

“In this cohort, similar to others, this seems to be more pronounced in women,” Dr. Jolley added.

Key findings on functioning

At 8 months, using a smartphone app, participants reported presence, duration, and severity of 23 predefined symptoms. Researchers used the Sheehan Disability Scale to gauge functional impairment.

A total of 11% participants reported at least one symptom that negatively affected work or social or home life at 8 months versus only 2% of the control group.

Seropositive participants were almost two times more likely to report that their long-term symptoms moderately to markedly disrupted their work life, 8% versus 4% of seronegative healthcare workers (relative risk, 1.8; 95%; confidence interval, 1.2-2.9).

Disruptions to a social life from long-term symptoms were 2.5 times more likely in the seropositive group. A total 15% of this cohort reported moderate to marked effects, compared with 6% of the seronegative group (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.8-3.6).

The researchers also inquired about home life disruptions, which were reported by 12% of the seropositive health care workers and 5% of the seronegative participants (RR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6-3.4).

The study’s findings “tracks with a lot of the other work we’re seeing,” David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview. He and his colleagues are responsible for managing the rehabilitation of patients with long COVID.

Interestingly, the proportion of people with persistent symptoms might be underestimated in this research, Dr. Putrino said. “Antibodies are not an entirely reliable biomarker. So what the researchers are using here is the most conservative measure of who may have had the virus.”

Potential recall bias and the subjective rating of symptoms were possible limitations of the study.

When asked to speculate why researchers did not find higher levels of cognitive dysfunction, Dr. Putrino said that self-reports are generally less reliable than measures like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for detecting cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, unlike many of the people with long-haul COVID-19 whom he treats clinically – ones who are “really struggling” – the health care workers studied in Sweden are functioning well enough to perform their duties at the hospital, so the study population may not represent the population at large.

More research required

“More research needs to be conducted to investigate the mechanisms underlying these persistent symptoms, and several centers, including UCSF, are conducting research into why this might be,” Dr. Santhosh said.

Dr. Thålin and colleagues plan to continue following participants. “The primary aim of the COMMUNITY study is to investigate long-term immunity after COVID-19, but we will also look into possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms behind COVID-19–related long-term symptoms,” she said.

“I hope to see that taste and smell will return,” Dr. Thålin added.

“We’re really just starting to understand the long-term effects of COVID-19,” Putrino said. “This is something we’re going to see a lot of moving forward.”

Dr. Thålin, Dr. Santhosh, Dr. Jolley, and Dr. Putrino disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The research was funded by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Jonas and Christina af Jochnick Foundation, Leif Lundblad Family Foundation, Region Stockholm, and Erling-Persson Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Loss of smell, loss of taste, dyspnea, and fatigue are the four most common symptoms that health care professionals in Sweden report 8 months after mild COVID-19 illness, new evidence reveals.

according to the study.

“We see that a substantial portion of health care workers suffer from long-term symptoms after mild COVID-19,” senior author Charlotte Thålin, MD, PhD, said in an interview. She added that loss of smell and taste “may seem trivial, but have a negative impact on work, social, and home life in the long run.”

The study is noteworthy not only for tracking the COVID-19-related experiences of health care workers over time, but also for what it did not find. There was no increased prevalence of cognitive issues – including memory or concentration – that others have linked to what’s often called long-haul COVID-19.

The research letter was published online April 7, 2021, in JAMA.

“Even if you are young and previously healthy, a mild COVID-19 infection may result in long-term consequences,” said Dr. Thålin, from the department of clinical sciences at Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The researchers did not observe an increased risk for long-term symptoms after asymptomatic COVID-19.

Adding to existing evidence

This research letter “adds to the growing body of literature showing that people recovering from COVID have reported a diverse array of symptoms lasting for months after initial infection,” Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, said in an interview. She is physician faculty lead at the University of California, San Francisco Post-COVID OPTIMAL Clinic.

Previous research revealed severe long-term symptoms, including heart palpitations and neurologic impairments, among people hospitalized with COVID-19. However, “there is limited data on the long-term effects after mild COVID-19, and these studies are often hampered by selection bias and without proper control groups,” Dr. Thålin said.

The absence of these more severe symptoms after mild COVID-19 is “reassuring,” she added.

The current findings are part of the ongoing COMMUNITY (COVID-19 Biomarker and Immunity) study looking at long-term immunity. Health care professionals enrolled in the research between April 15 and May 8, 2020, and have initial blood tests repeated every 4 months.

Dr. Thålin, lead author Sebastian Havervall, MD, and their colleagues compared symptom reporting between 323 hospital employees who had mild COVID-19 at least 8 months earlier with 1,072 employees who did not have COVID-19 throughout the study.

The results show that 26% of those who had COVID-19 previously had at least one moderate to severe symptom that lasted more than 2 months, compared with 9% in the control group.

The group with a history of mild COVID-19 was a median 43 years old and 83% were women. The controls were a median 47 years old and 86% were women.

“These data mirror what we have seen across long-term cohorts of patients with COVID-19 infection. Notably, mild illness among previously healthy individuals may be associated with long-term persistent symptoms,” Sarah Jolley, MD, a pulmonologist specializing in critical care at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and director of the Post-COVID Clinic, said in an interview.

“In this cohort, similar to others, this seems to be more pronounced in women,” Dr. Jolley added.

Key findings on functioning

At 8 months, using a smartphone app, participants reported presence, duration, and severity of 23 predefined symptoms. Researchers used the Sheehan Disability Scale to gauge functional impairment.

A total of 11% participants reported at least one symptom that negatively affected work or social or home life at 8 months versus only 2% of the control group.

Seropositive participants were almost two times more likely to report that their long-term symptoms moderately to markedly disrupted their work life, 8% versus 4% of seronegative healthcare workers (relative risk, 1.8; 95%; confidence interval, 1.2-2.9).

Disruptions to a social life from long-term symptoms were 2.5 times more likely in the seropositive group. A total 15% of this cohort reported moderate to marked effects, compared with 6% of the seronegative group (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.8-3.6).

The researchers also inquired about home life disruptions, which were reported by 12% of the seropositive health care workers and 5% of the seronegative participants (RR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6-3.4).

The study’s findings “tracks with a lot of the other work we’re seeing,” David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview. He and his colleagues are responsible for managing the rehabilitation of patients with long COVID.

Interestingly, the proportion of people with persistent symptoms might be underestimated in this research, Dr. Putrino said. “Antibodies are not an entirely reliable biomarker. So what the researchers are using here is the most conservative measure of who may have had the virus.”

Potential recall bias and the subjective rating of symptoms were possible limitations of the study.

When asked to speculate why researchers did not find higher levels of cognitive dysfunction, Dr. Putrino said that self-reports are generally less reliable than measures like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for detecting cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, unlike many of the people with long-haul COVID-19 whom he treats clinically – ones who are “really struggling” – the health care workers studied in Sweden are functioning well enough to perform their duties at the hospital, so the study population may not represent the population at large.

More research required

“More research needs to be conducted to investigate the mechanisms underlying these persistent symptoms, and several centers, including UCSF, are conducting research into why this might be,” Dr. Santhosh said.

Dr. Thålin and colleagues plan to continue following participants. “The primary aim of the COMMUNITY study is to investigate long-term immunity after COVID-19, but we will also look into possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms behind COVID-19–related long-term symptoms,” she said.

“I hope to see that taste and smell will return,” Dr. Thålin added.

“We’re really just starting to understand the long-term effects of COVID-19,” Putrino said. “This is something we’re going to see a lot of moving forward.”

Dr. Thålin, Dr. Santhosh, Dr. Jolley, and Dr. Putrino disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The research was funded by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Jonas and Christina af Jochnick Foundation, Leif Lundblad Family Foundation, Region Stockholm, and Erling-Persson Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Loss of smell, loss of taste, dyspnea, and fatigue are the four most common symptoms that health care professionals in Sweden report 8 months after mild COVID-19 illness, new evidence reveals.

according to the study.

“We see that a substantial portion of health care workers suffer from long-term symptoms after mild COVID-19,” senior author Charlotte Thålin, MD, PhD, said in an interview. She added that loss of smell and taste “may seem trivial, but have a negative impact on work, social, and home life in the long run.”

The study is noteworthy not only for tracking the COVID-19-related experiences of health care workers over time, but also for what it did not find. There was no increased prevalence of cognitive issues – including memory or concentration – that others have linked to what’s often called long-haul COVID-19.

The research letter was published online April 7, 2021, in JAMA.

“Even if you are young and previously healthy, a mild COVID-19 infection may result in long-term consequences,” said Dr. Thålin, from the department of clinical sciences at Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm.

The researchers did not observe an increased risk for long-term symptoms after asymptomatic COVID-19.

Adding to existing evidence

This research letter “adds to the growing body of literature showing that people recovering from COVID have reported a diverse array of symptoms lasting for months after initial infection,” Lekshmi Santhosh, MD, said in an interview. She is physician faculty lead at the University of California, San Francisco Post-COVID OPTIMAL Clinic.

Previous research revealed severe long-term symptoms, including heart palpitations and neurologic impairments, among people hospitalized with COVID-19. However, “there is limited data on the long-term effects after mild COVID-19, and these studies are often hampered by selection bias and without proper control groups,” Dr. Thålin said.

The absence of these more severe symptoms after mild COVID-19 is “reassuring,” she added.

The current findings are part of the ongoing COMMUNITY (COVID-19 Biomarker and Immunity) study looking at long-term immunity. Health care professionals enrolled in the research between April 15 and May 8, 2020, and have initial blood tests repeated every 4 months.

Dr. Thålin, lead author Sebastian Havervall, MD, and their colleagues compared symptom reporting between 323 hospital employees who had mild COVID-19 at least 8 months earlier with 1,072 employees who did not have COVID-19 throughout the study.

The results show that 26% of those who had COVID-19 previously had at least one moderate to severe symptom that lasted more than 2 months, compared with 9% in the control group.

The group with a history of mild COVID-19 was a median 43 years old and 83% were women. The controls were a median 47 years old and 86% were women.

“These data mirror what we have seen across long-term cohorts of patients with COVID-19 infection. Notably, mild illness among previously healthy individuals may be associated with long-term persistent symptoms,” Sarah Jolley, MD, a pulmonologist specializing in critical care at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora and director of the Post-COVID Clinic, said in an interview.

“In this cohort, similar to others, this seems to be more pronounced in women,” Dr. Jolley added.

Key findings on functioning

At 8 months, using a smartphone app, participants reported presence, duration, and severity of 23 predefined symptoms. Researchers used the Sheehan Disability Scale to gauge functional impairment.

A total of 11% participants reported at least one symptom that negatively affected work or social or home life at 8 months versus only 2% of the control group.

Seropositive participants were almost two times more likely to report that their long-term symptoms moderately to markedly disrupted their work life, 8% versus 4% of seronegative healthcare workers (relative risk, 1.8; 95%; confidence interval, 1.2-2.9).

Disruptions to a social life from long-term symptoms were 2.5 times more likely in the seropositive group. A total 15% of this cohort reported moderate to marked effects, compared with 6% of the seronegative group (RR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.8-3.6).

The researchers also inquired about home life disruptions, which were reported by 12% of the seropositive health care workers and 5% of the seronegative participants (RR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.6-3.4).

The study’s findings “tracks with a lot of the other work we’re seeing,” David Putrino, PT, PhD, director of rehabilitation innovation at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, said in an interview. He and his colleagues are responsible for managing the rehabilitation of patients with long COVID.

Interestingly, the proportion of people with persistent symptoms might be underestimated in this research, Dr. Putrino said. “Antibodies are not an entirely reliable biomarker. So what the researchers are using here is the most conservative measure of who may have had the virus.”

Potential recall bias and the subjective rating of symptoms were possible limitations of the study.

When asked to speculate why researchers did not find higher levels of cognitive dysfunction, Dr. Putrino said that self-reports are generally less reliable than measures like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for detecting cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, unlike many of the people with long-haul COVID-19 whom he treats clinically – ones who are “really struggling” – the health care workers studied in Sweden are functioning well enough to perform their duties at the hospital, so the study population may not represent the population at large.

More research required

“More research needs to be conducted to investigate the mechanisms underlying these persistent symptoms, and several centers, including UCSF, are conducting research into why this might be,” Dr. Santhosh said.

Dr. Thålin and colleagues plan to continue following participants. “The primary aim of the COMMUNITY study is to investigate long-term immunity after COVID-19, but we will also look into possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms behind COVID-19–related long-term symptoms,” she said.

“I hope to see that taste and smell will return,” Dr. Thålin added.

“We’re really just starting to understand the long-term effects of COVID-19,” Putrino said. “This is something we’re going to see a lot of moving forward.”

Dr. Thålin, Dr. Santhosh, Dr. Jolley, and Dr. Putrino disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The research was funded by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Jonas and Christina af Jochnick Foundation, Leif Lundblad Family Foundation, Region Stockholm, and Erling-Persson Family Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High-Potency Topical Steroid Treatment of Multiple Keratoacanthomas Associated With Prurigo Nodularis

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

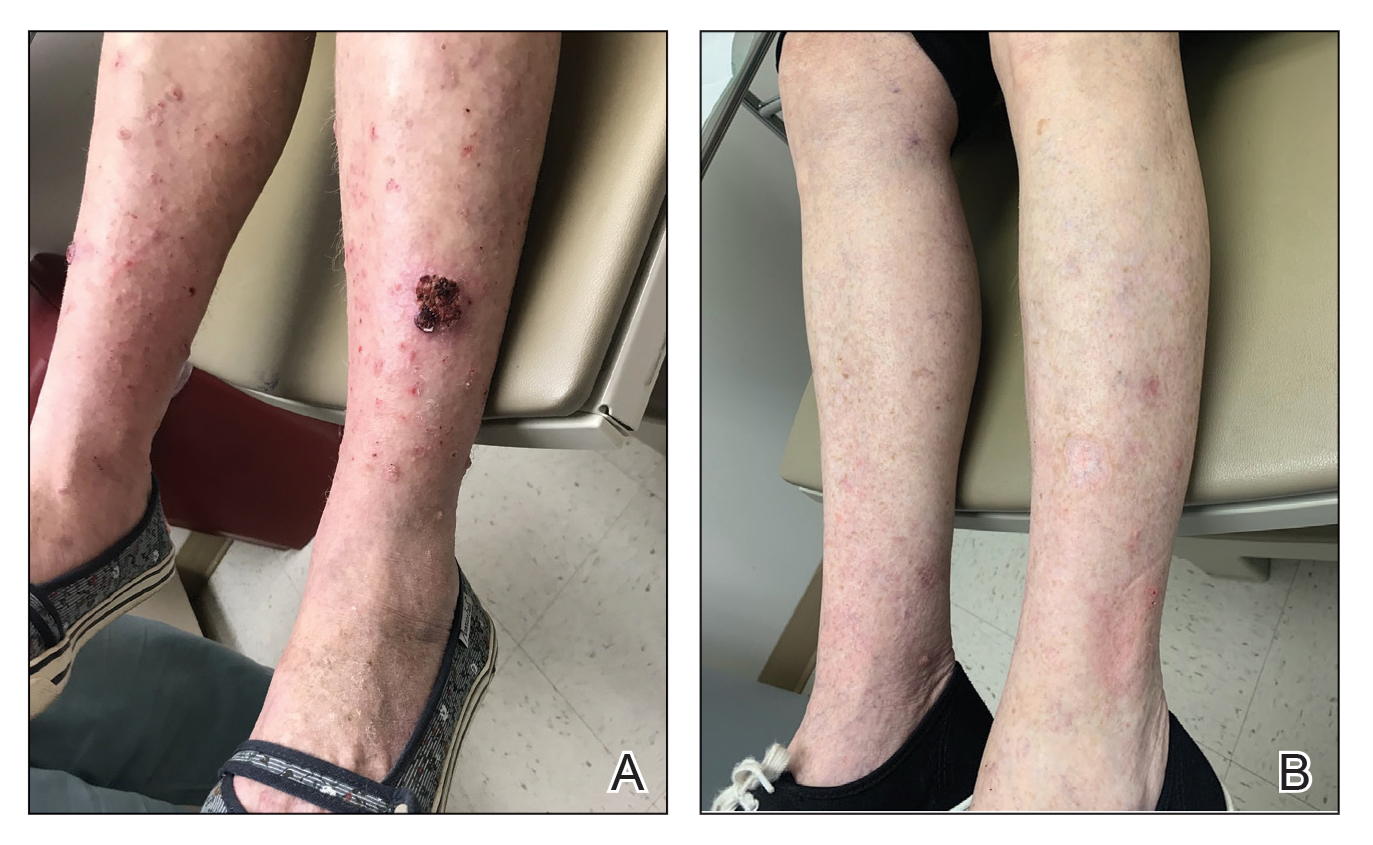

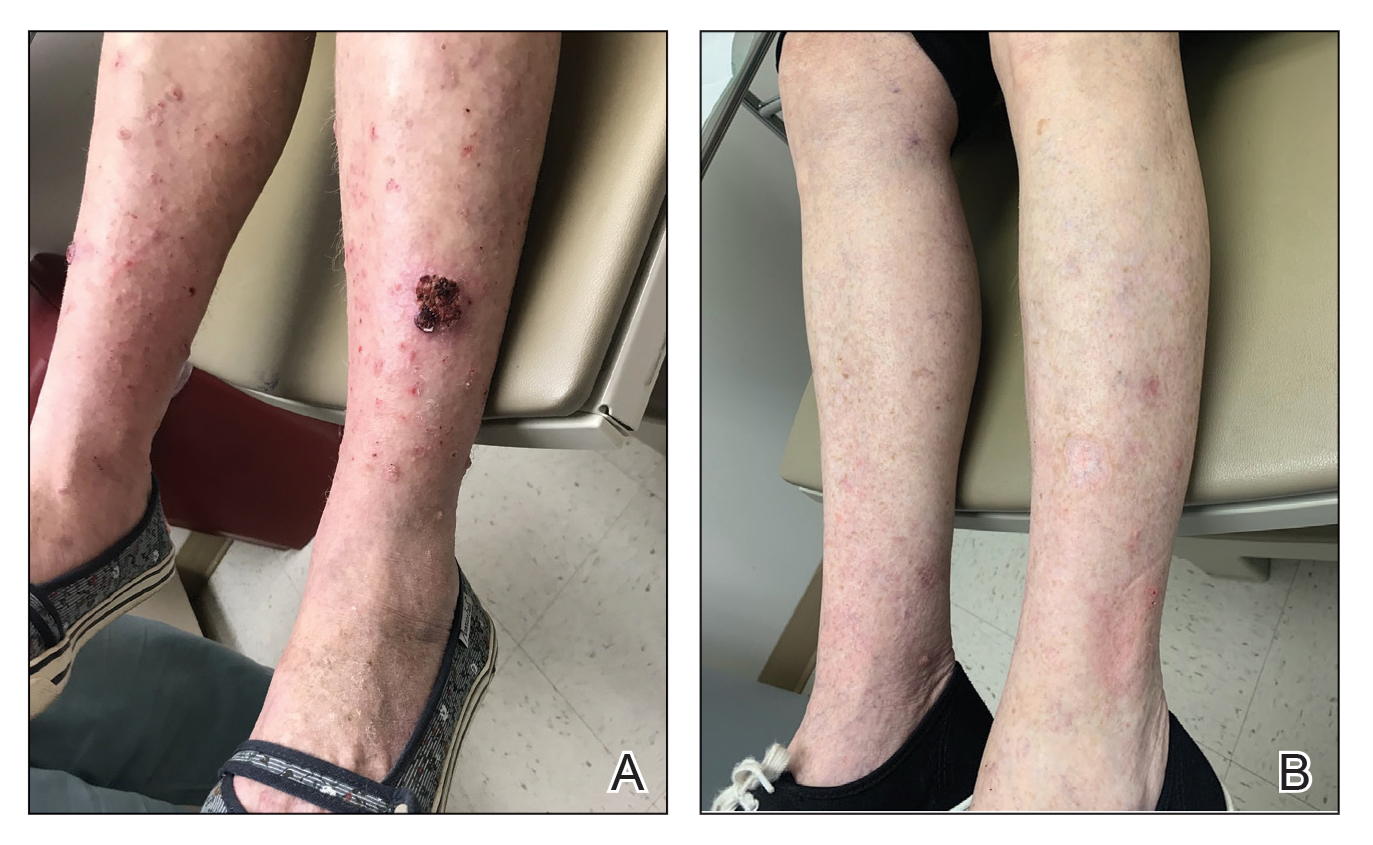

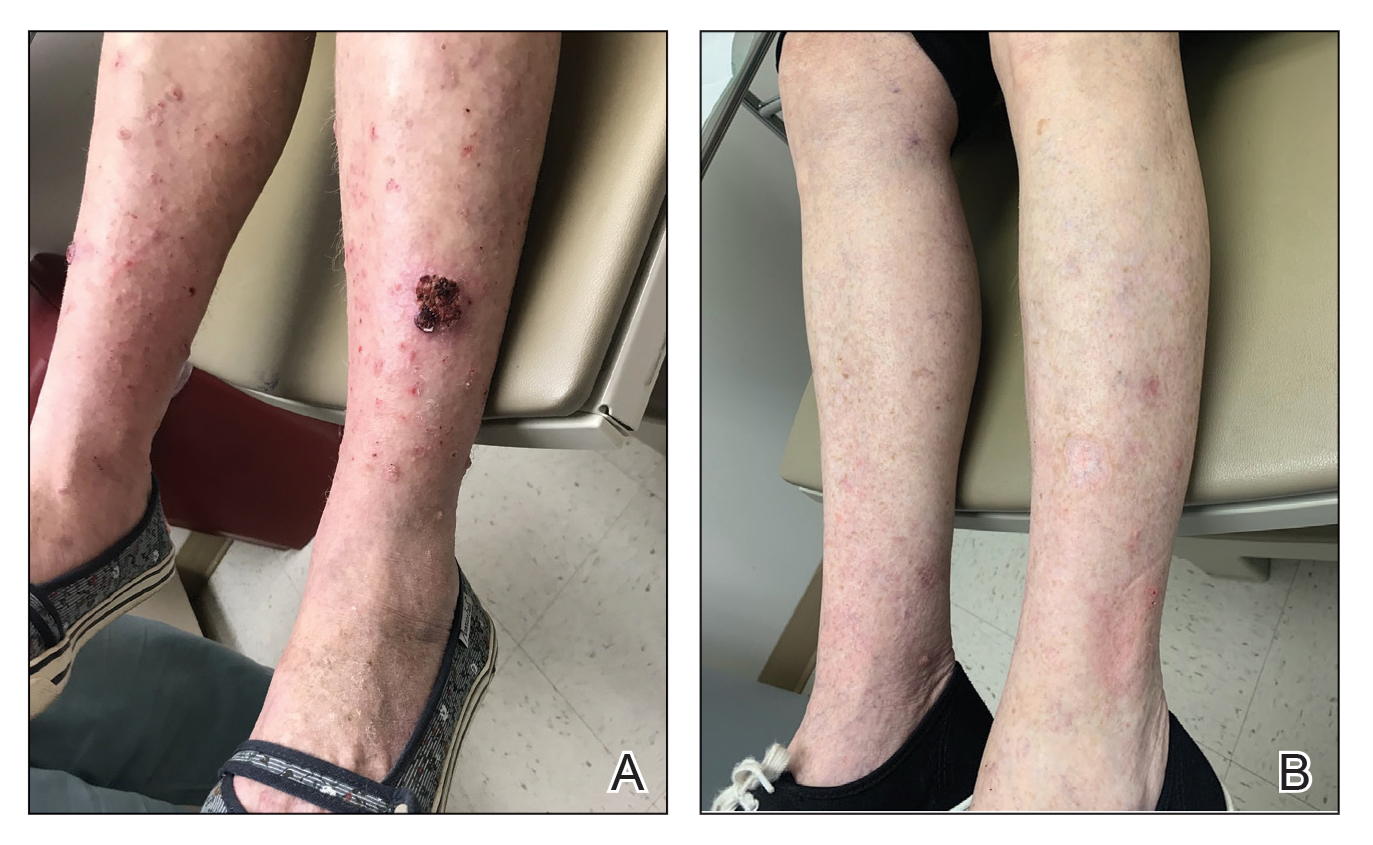

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

Practice Gap

Multiple keratoacanthomas (KAs) of the legs often are a challenge to treat, especially when these lesions appear within a field of prurigo nodules. Multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis is a rarer finding; more often, the condition is reported on the lower limbs of elderly women with actinically damaged skin.1,2 At times, it can be difficult to distinguish between KA and prurigo nodularis in these patients, who often report notable pruritus and might have associated eczematous dermatitis.2

Keratoacanthomas often are treated with aggressive modalities, such as Mohs micrographic surgery, excision, and electrodesiccation and curettage. Some patients are hesitant to undergo surgical treatment, however, preferring a less invasive approach. Trauma from these aggressive modalities also can be associated with recurrence of existing lesions or development of new KAs, possibly related to stimulation of a local inflammatory response and upregulation of helper T cells.2-4

Acitretin and other systemic retinoids often are considered first-line therapy for multiple KAs. Cyclosporine has been added as adjunctive treatment in cases associated with prurigo nodularis or eczematous dermatitis1,2; however, these treatments have a high rate of discontinuation because of adverse effects, including transaminitis, xerostomia, alopecia (acitretin), and renal toxicity (cyclosporine).2

Another treatment option for patients with coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis is intralesional corticosteroids, often administered in combination with systemic retinoids.3 Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) has been used successfully for KA, but topical treatment options are limited if 5-FU fails. Topical imiquimod and cryotherapy are thought to be of little benefit, and the appearance of new KA within imiquimod and cryotherapy treatment fields has been reported.1,2 Topical corticosteroids have been used as an adjuvant therapy for multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms keratoacanthoma and steroid and keratoacanthoma and prurigo nodularis yielded no published reports of successful use of topical corticosteroids as monotherapy.2

The Technique

For patients who want to continue topical treatment of coexisting KA and prurigo nodularis after topical 5-FU fails, we have found success applying a high-potency topical corticosteroid to affected areas under occlusion nightly for 6 to 8 weeks. This treatment not only leads to resolution of KA but also simultaneously treats prurigo nodules that might be clinically difficult to distinguish from KA in some presentations. This regimen has been implemented in our practice with remarkable reduction of KA burden and relief of pruritus.

In a 68-year-old woman who was treated with this technique, multiple biopsies had shown KA (or well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma that appeared clinically as KA) on the shin (Figure, A) arising amid many lesions consistent with prurigo nodules. Topical 5-FU had failed, but the patient did not want to be treated with a more invasive modality, such as excision or injection.

Instead, we treated the patient with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion nightly for 6 weeks. This strategy produced resolution of both KA and prurigo nodules (Figure, B). When lesions recurred after a few months, they were successfully re-treated with topical clobetasol under occlusion in a second 6-week course.

Practical Implications

Treatment of multiple KAs associated with prurigo nodularis can present a distinct challenge. For the subset of patients who want to pursue topical treatment, options reported in the literature are limited. We have found success treating multiple KAs and associated prurigo nodules with a high-potency topical corticosteroid under occlusion, with minimal or no adverse effects. We believe that a topical corticosteroid can be implemented easily in clinical practice before a more invasive surgical or intralesional modality is considered.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033

- Wu TP, Miller K, Cohen DE, et al. Keratoacanthomas arising in association with prurigo nodules in pruritic, actinically damaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:426-430. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2013.03.035

- Sanders S, Busam KJ, Halpern AC, et al. Intralesional corticosteroid treatment of multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas: case report and review of a controversial therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:954-958. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02069.x

- Lee S, Coutts I, Ryan A, et al. Keratoacanthoma formation after skin grafting: a brief report and pathophysiological hypothesis. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E117-E119. doi:10.1111/ajd.12501

Gynecologic and Obstetric Implications of Darier Disease: A Dermatologist’s Perspective

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

Darier disease (DD)(also known as dyskeratosis follicularis) is a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by greasy, rough, keratotic papules; typical nail abnormalities; mucosal changes; and characteristic dyskeratotic acantholysis that is called corps ronds and grains on histopathologic analysis. Darier disease is caused by mutations of the ATP2A2 gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1,2

Because of the autosomal-dominant pattern of inheritance in DD, if either parent is affected by DD, approximately 50% of their offspring will have the disorder. Therefore, couples need to be offered genetic counseling at a preconception visit or early in pregnancy. Although penetrance of DD is complete, spontaneous mutations are frequent and expressivity is variable1; prenatal diagnosis, though available since the 1980s, is therefore unreliable in DD, given the considerable variation in phenotypic expressivity. Differing phenotypes underscore the importance of proper counseling by the treating dermatologist or other provider. Females with a mild or nearly undetectable phenotype can give birth to a child with severe disease.

Lack of clear understanding about the variable phenotypic expressivity of DD can cause considerable anger, anxiety, guilt, psychological trauma, and fear in parents, should their child later develop a severe phenotype. They may feel that they were not properly prepared for the outcome. The physician-parent or physician-patient relationship can be negatively impacted if ongoing counseling is inadequate.

Clinically, DD presents in early adolescence (age range, 6–20 years) in most patients, which means that the disease and female reproductive years are contemporaneous. However, gynecologic and obstetric issues and complications of DD rarely have been addressed.3 Oromucosal involvement in DD is reported in 13% to 50% of cases, yet vaginal and cervical mucosal involvement rarely has been described,4,5 likely due to underreporting. Therefore, in this rare disease, it is important to address these aspects so that the patients are provided with appropriate management options.

Implications for Cervical Screening and Papanicolaou Tests

Cytopathologic findings of a Papanicolaou test taken from a patient with DD can lead to erroneous diagnosis of a low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion due to cervical involvement by the disease process; therefore, correct interpretation of a smear may be inappropriate and erroneous. The cytopathologist needs to be informed of the patient’s diagnosis of DD in advance for appropriate reporting.5,6

Obstetric Implications

Fertility is normal in DD patients, and pregnancy usually has a normal course; however, exacerbation and remission of disease have been reported. de la Rosa Carrillo7 reported a case of vegetating DD during pregnancy. He described it as an exacerbation with concurrent bacterial infection and bilateral external otitis.7 Spouge et al8 reported a case of a 58-year-old woman who was the mother of 4 DD patients. She experienced an exacerbation of DD during all 6 pregnancies but improved immediately postpartum.8 Espy et al9 evaluated 8 cases of women with DD and described spontaneous improvement of the disorder during pregnancy (1 case) or while taking an oral contraceptive (3 cases).

Prenatal Counseling

Women with DD should be encouraged to talk to their dermatologist, obstetrician, or other provider of prenatal care regarding plans for pregnancy, labor, and delivery, as these events might be affected by the disorder. During pregnancy, careful monitoring and self-care remain essential. Simple measures to reduce the impact of irritants on DD during pregnancy include keeping the skin cool, using a soothing moisturizer, applying photoprotection, and using sunscreen. Treatment with systemic retinoids must be avoided if pregnancy is planned.

Warty plaques and papules of DD can involve flexures (groin, vulva, and perineum), with resultant malodor and pruritus10 as well as the potential for (drug resistant) secondary infection (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, group B Streptococcus, viruses [eg, Kaposi varicelliform eruption]). Skin swabs should be taken for culture and susceptibility testing, and infection should be treated at the earliest sign.

Management Concerns During Pregnancy and Delivery

Because the benefits of treating DD might outweigh risk in certain cases, thorough discussion with the patient about options is recommended, including the following concerns:

• Because mucocutaneous elasticity of the birth canal, including the vulva, perineum, and groin, is essential for nontraumatic vaginal delivery, it might be necessary to schedule an elective cesarean delivery in DD patients in whom these regions are involved.11

• In females with lower abdominal lesions, using a Pfannenstiel-Kerr incision for cesarean delivery might be problematic.11

• A single case report has described successful anesthetic management of labor, delivery, and postpartum care in a DD patient.12 Involvement of the skin of the back might preclude safe administration of regional anesthesia; however, because DD lesions are considered noninfectious, the authors operatively administered a subarachnoid block at the L3-L4 interspace through a lesion-free area. Postpartum, the patient was observed in the intensive care unit. She and the baby remained stable; she did not develop infectious complications, including a central nervous system infection.12

•Mucosal involvement is relatively rare in DD and has not been reported to compromise airway management.8

Postnatal Considerations

Breastfeeding might have to be stopped early or withheld altogether if there is widespread involvement of the skin of the breast or the nipple.11 Darier disease has been associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, including major depression (30%), suicide attempts (13%), suicidal thoughts (31%), cyclothymia, bipolar disorder (4%), and epilepsy (3%).13,14 Therefore, patients should be screened for postpartum psychiatric manifestations at an early follow-up visit.

Final Thoughts

Although the etiology of DD is well known, the gynelogic and obstretric implications of this genodermatosis have rarely been described. This brief commentary is an attempt to provide the important information to a practicing dermatologist for appropriate management of female DD patients.

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

- Bale SJ, Toro JR. Genetic basis of Darier-White disease: bad pumps cause bumps. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:103-106. doi:10.1177/120347540000400212

- Kansal NK, Hazarika N, Rao S. Familial case of Darier disease with guttate leukoderma: a case series from India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:62-63. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_52_17

- Lynch PJ. Vulvar dermatoses: the eczematous diseases. In: Black M, Ambros-Rudolph CM, Edwards L, Lynch P, eds. Obstetric and Gynecologic Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mosby-Elsevier; 2008:192-194.

- Adam AE. Ectopic Darier’s disease of the cervix: an extraordinary cause of an abnormal smear. Cytopathology. 1996;7:414-421. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2303.1996.tb00547.x

- Suárez-Peñaranda JM, Antúnez JR, Del Rio E, et al. Vaginal involvement in a woman with Darier’s disease: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:530-532. doi:10.1159/000326200

- Boon ME. Dr. Darier’s lesson: it can be advantageous to the patient to ignore evident cytonuclear changes. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:469-470. doi:10.1159/000326189

- de la Rosa Carrillo D. Vegetating Darier’s disease during pregnancy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:259-260. doi:10.2340/00015555-0066

- Spouge JD, Trott JR, Chesko G. Darier-White’s disease: a cause of white lesions of the mucosa. report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:441-457. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(66)90401-4

- Espy PD, Stone S, Jolly HW Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315-320.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Saikia UN. Uncommon flexural presentation of Darier disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:249-252. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07035

- Quinlivan JA, O'Halloran LC. Darier’s disease and pregnancy. Dermatol Aspects. 2013;1:1-3. doi:10.7243/2053-5309-1-1

- Sharma R, Singh BP, Das SN. Anesthetic management of cesarean section in a parturient with Darier’s disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2010;48:158-159. doi:10.1016/S1875-4597(10)60051-3

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Dodiuk-Gad RP, Cohen-Barak E, Khayat M, et al. Darier disease in Israel: combined evaluation of genetic and neuropsychiatric aspects. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:562-568. doi:10.1111/bjd.14220

Practice Points

- Because Darier disease (DD) manifests during reproductive years, systemic retinoids should be used carefully in female patients.

- For a Papanicolaou test to be properly interpreted in a patient with DD, the cytopathologist must be informed of the DD diagnosis.

- Darier disease may be exacerbated or relieved during pregnancy.

A thoughtful approach to drug screening and addiction

Reading the excellent article on urine drug screening by Drs. Hayes and Fox reminds me of 2 important aspects of primary care: (1) Diagnosing and treating patients with drug addiction is an important service we provide, and (2) interpreting laboratory tests requires training, skill, and clinical judgment.

Drs. Hayes and Fox describe the proper use of urine drug testing in the management of patients for whom we prescribe opioids, whether for chronic pain or for addiction treatment. Combining a review of the literature with their own professional experience treating these patients, Drs. Hayes and Fox highlight the potential pitfalls in interpreting urine drug screening results and admonish us to use good clinical judgment in applying those results to patient care. They emphasize the need to avoid racial bias and blaming the patient.

This article is very timely because, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic has continued unabated. The most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that the estimated number of opioid overdose deaths increased by a whopping 32%, from 47,772 for the 1-year period ending August 2019 to 62,972 for the 1-year period ending August 2020.1 Although this increase began in fall 2019, there can be little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is partly responsible. A positive sign, however, is that opioid prescribing in the United States is trending downward, reaching its lowest level in 14 years in 2019.2 In fact, use of cheap street fentanyl, rather than prescription drugs, accounts for nearly all of the increase in opioid overdose deaths.1

Despite this positive news, the number of deaths associated with opioid use remains sobering. The statistics continue to underscore the fact that there simply are not enough addiction treatment centers to manage all of those who need and want help. All primary care physicians are eligible to prescribe suboxone to treat patients with opioid addiction—a treatment that can be highly effective in reducing the use of street opioids and, therefore, reducing deaths from overdose. Fewer than 10% of primary care physicians prescribed suboxone in 2017.3 I hope that more of you will take the required training and become involved in assisting your patients who struggle with opioid addiction.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2. CDC. US opioid dispensing rate maps. Updated December 7, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html

3. McBain RK, Dick A, Sorbero M, et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:504-506.

Reading the excellent article on urine drug screening by Drs. Hayes and Fox reminds me of 2 important aspects of primary care: (1) Diagnosing and treating patients with drug addiction is an important service we provide, and (2) interpreting laboratory tests requires training, skill, and clinical judgment.

Drs. Hayes and Fox describe the proper use of urine drug testing in the management of patients for whom we prescribe opioids, whether for chronic pain or for addiction treatment. Combining a review of the literature with their own professional experience treating these patients, Drs. Hayes and Fox highlight the potential pitfalls in interpreting urine drug screening results and admonish us to use good clinical judgment in applying those results to patient care. They emphasize the need to avoid racial bias and blaming the patient.

This article is very timely because, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic has continued unabated. The most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that the estimated number of opioid overdose deaths increased by a whopping 32%, from 47,772 for the 1-year period ending August 2019 to 62,972 for the 1-year period ending August 2020.1 Although this increase began in fall 2019, there can be little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is partly responsible. A positive sign, however, is that opioid prescribing in the United States is trending downward, reaching its lowest level in 14 years in 2019.2 In fact, use of cheap street fentanyl, rather than prescription drugs, accounts for nearly all of the increase in opioid overdose deaths.1

Despite this positive news, the number of deaths associated with opioid use remains sobering. The statistics continue to underscore the fact that there simply are not enough addiction treatment centers to manage all of those who need and want help. All primary care physicians are eligible to prescribe suboxone to treat patients with opioid addiction—a treatment that can be highly effective in reducing the use of street opioids and, therefore, reducing deaths from overdose. Fewer than 10% of primary care physicians prescribed suboxone in 2017.3 I hope that more of you will take the required training and become involved in assisting your patients who struggle with opioid addiction.

Reading the excellent article on urine drug screening by Drs. Hayes and Fox reminds me of 2 important aspects of primary care: (1) Diagnosing and treating patients with drug addiction is an important service we provide, and (2) interpreting laboratory tests requires training, skill, and clinical judgment.

Drs. Hayes and Fox describe the proper use of urine drug testing in the management of patients for whom we prescribe opioids, whether for chronic pain or for addiction treatment. Combining a review of the literature with their own professional experience treating these patients, Drs. Hayes and Fox highlight the potential pitfalls in interpreting urine drug screening results and admonish us to use good clinical judgment in applying those results to patient care. They emphasize the need to avoid racial bias and blaming the patient.

This article is very timely because, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic has continued unabated. The most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that the estimated number of opioid overdose deaths increased by a whopping 32%, from 47,772 for the 1-year period ending August 2019 to 62,972 for the 1-year period ending August 2020.1 Although this increase began in fall 2019, there can be little doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic is partly responsible. A positive sign, however, is that opioid prescribing in the United States is trending downward, reaching its lowest level in 14 years in 2019.2 In fact, use of cheap street fentanyl, rather than prescription drugs, accounts for nearly all of the increase in opioid overdose deaths.1

Despite this positive news, the number of deaths associated with opioid use remains sobering. The statistics continue to underscore the fact that there simply are not enough addiction treatment centers to manage all of those who need and want help. All primary care physicians are eligible to prescribe suboxone to treat patients with opioid addiction—a treatment that can be highly effective in reducing the use of street opioids and, therefore, reducing deaths from overdose. Fewer than 10% of primary care physicians prescribed suboxone in 2017.3 I hope that more of you will take the required training and become involved in assisting your patients who struggle with opioid addiction.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2. CDC. US opioid dispensing rate maps. Updated December 7, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html

3. McBain RK, Dick A, Sorbero M, et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:504-506.

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

2. CDC. US opioid dispensing rate maps. Updated December 7, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2021. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html

3. McBain RK, Dick A, Sorbero M, et al. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:504-506.

Botanical Briefs: Phytophotodermatitis Is an Occupational and Recreational Dermatosis in the Limelight