User login

Common Comorbidities of Chronic Rhinosinusitis With Nasal Polyps

The majority of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have both upper and lower airway comorbidities such as asthma, allergic rhinosinusitis, and GERD. Recent data show that more than 50% of patients with CRSwNP have concurrent asthma.

Comorbidities in CRSwNP increase the risk for refractory disease, lead to repeated surgical procedures, and adversely affect patients' quality of life.

Dr Anju Peters, from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, discusses the importance of identifying comorbidities in patients with CRSwNP in order to create a more effective and personalized treatment plan.

---

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; Director of Clinical Research, Associate Chief of Research, Education, and Clinical Affairs, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on the advisory board for: Sanofi Regeneron; Optinose; AstraZeneca. Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Optinose.

The majority of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have both upper and lower airway comorbidities such as asthma, allergic rhinosinusitis, and GERD. Recent data show that more than 50% of patients with CRSwNP have concurrent asthma.

Comorbidities in CRSwNP increase the risk for refractory disease, lead to repeated surgical procedures, and adversely affect patients' quality of life.

Dr Anju Peters, from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, discusses the importance of identifying comorbidities in patients with CRSwNP in order to create a more effective and personalized treatment plan.

---

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; Director of Clinical Research, Associate Chief of Research, Education, and Clinical Affairs, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on the advisory board for: Sanofi Regeneron; Optinose; AstraZeneca. Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Optinose.

The majority of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) have both upper and lower airway comorbidities such as asthma, allergic rhinosinusitis, and GERD. Recent data show that more than 50% of patients with CRSwNP have concurrent asthma.

Comorbidities in CRSwNP increase the risk for refractory disease, lead to repeated surgical procedures, and adversely affect patients' quality of life.

Dr Anju Peters, from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, discusses the importance of identifying comorbidities in patients with CRSwNP in order to create a more effective and personalized treatment plan.

---

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; Director of Clinical Research, Associate Chief of Research, Education, and Clinical Affairs, Division of Allergy-Immunology, Northwestern Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Anju T. Peters, MD, MSci, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on the advisory board for: Sanofi Regeneron; Optinose; AstraZeneca. Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Optinose.

AGA, GI societies support lowering CRC screening age

American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy issued a statement of support that also notes our Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer is finalizing our own recommendation to start screening at 45 years of age as well.

Incoming AGA President John M. Inadomi, MD, AGAF, notes that, “We expect this important change to save lives and improve the health of the U.S. population.”

AGA fully supports the decision of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to reduce the age at which to initiate screening among individuals at average risk for development of colorectal cancer to 45 years. This decision harmonizes the recommendations between the major U.S. screening guidelines including the American Cancer Society and American College of Physicians.

“The analysis by the USPSTF is timely and incredibly helpful to population health and to gastroenterologists and other providers,” says Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, AGAF, president of AGA. “We now have clear guidance to start colorectal cancer screening at age 45 for those with average risk and discontinue screening after age 85.”

American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy issued a statement of support that also notes our Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer is finalizing our own recommendation to start screening at 45 years of age as well.

Incoming AGA President John M. Inadomi, MD, AGAF, notes that, “We expect this important change to save lives and improve the health of the U.S. population.”

AGA fully supports the decision of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to reduce the age at which to initiate screening among individuals at average risk for development of colorectal cancer to 45 years. This decision harmonizes the recommendations between the major U.S. screening guidelines including the American Cancer Society and American College of Physicians.

“The analysis by the USPSTF is timely and incredibly helpful to population health and to gastroenterologists and other providers,” says Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, AGAF, president of AGA. “We now have clear guidance to start colorectal cancer screening at age 45 for those with average risk and discontinue screening after age 85.”

American Gastroenterological Association, American College of Gastroenterology, and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy issued a statement of support that also notes our Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer is finalizing our own recommendation to start screening at 45 years of age as well.

Incoming AGA President John M. Inadomi, MD, AGAF, notes that, “We expect this important change to save lives and improve the health of the U.S. population.”

AGA fully supports the decision of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to reduce the age at which to initiate screening among individuals at average risk for development of colorectal cancer to 45 years. This decision harmonizes the recommendations between the major U.S. screening guidelines including the American Cancer Society and American College of Physicians.

“The analysis by the USPSTF is timely and incredibly helpful to population health and to gastroenterologists and other providers,” says Bishr Omary, MD, PhD, AGAF, president of AGA. “We now have clear guidance to start colorectal cancer screening at age 45 for those with average risk and discontinue screening after age 85.”

The 2021-2022 research awards cycle is now open

We are pleased to announce that the AGA Research Foundation’s research awards cycle is now open.

The cycle begins with our two specialty awards focused on digestive and gastric cancers – applications are due on July 21.

AGA–Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer: One $40,000 award supports an early career investigator who holds a career development award devoted to digestive cancer research.

AGA–R. Robert & Sally Funderburg Research Award in Gastric Cancer One $100,000 award supports an established investigator working on novel approaches in gastric cancer research.

In addition to our usual awards portfolio focused on a broad range of digestive diseases, we have established several new awards that will fund research focused on health and health care disparities. Click on the links below to learn more about each award and application requirements.

- Pilot Research Awards: Currently accepting applications

- Research Scholar Awards: Open Aug. 12

We are pleased to announce that the AGA Research Foundation’s research awards cycle is now open.

The cycle begins with our two specialty awards focused on digestive and gastric cancers – applications are due on July 21.

AGA–Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer: One $40,000 award supports an early career investigator who holds a career development award devoted to digestive cancer research.

AGA–R. Robert & Sally Funderburg Research Award in Gastric Cancer One $100,000 award supports an established investigator working on novel approaches in gastric cancer research.

In addition to our usual awards portfolio focused on a broad range of digestive diseases, we have established several new awards that will fund research focused on health and health care disparities. Click on the links below to learn more about each award and application requirements.

- Pilot Research Awards: Currently accepting applications

- Research Scholar Awards: Open Aug. 12

We are pleased to announce that the AGA Research Foundation’s research awards cycle is now open.

The cycle begins with our two specialty awards focused on digestive and gastric cancers – applications are due on July 21.

AGA–Caroline Craig Augustyn & Damian Augustyn Award in Digestive Cancer: One $40,000 award supports an early career investigator who holds a career development award devoted to digestive cancer research.

AGA–R. Robert & Sally Funderburg Research Award in Gastric Cancer One $100,000 award supports an established investigator working on novel approaches in gastric cancer research.

In addition to our usual awards portfolio focused on a broad range of digestive diseases, we have established several new awards that will fund research focused on health and health care disparities. Click on the links below to learn more about each award and application requirements.

- Pilot Research Awards: Currently accepting applications

- Research Scholar Awards: Open Aug. 12

The gift you should be talking about

If you want to make a lasting impact at the AGA Research Foundation, one of the easiest ways is to name us as a beneficiary of one of your assets, such as your retirement plan, life insurance policy, bank account, or donor-advised fund.

When you do, don’t forget to notify us of your decisions. Many charities and individuals aren’t aware that they have been named to receive a gift. Informing them helps preserve your intentions and ensures that your beneficiaries are able to follow your wishes.

Steps to protect the people and charities you love

- Review your beneficiary designations periodically because circumstances change throughout your lifetime.

- Alert your beneficiaries that you have a life insurance policy or have named them as beneficiaries of a retirement plan.

- Share the location and details of the policy or plan with your beneficiaries.

As you update your beneficiary designations, consider making a gift of a life insurance policy or retirement plan to the AGA Research Foundation so that we can continue to progress with our mission. Then let us know about your decision so that we can carry out your wishes as intended and thank you for your gift.

We want to hear from you

If you have already named the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy or retirement plan assets, please contact us at [email protected] today. If you are still creating your estate plan, we would be happy to answer any questions you may have about making this type of gift.

If you want to make a lasting impact at the AGA Research Foundation, one of the easiest ways is to name us as a beneficiary of one of your assets, such as your retirement plan, life insurance policy, bank account, or donor-advised fund.

When you do, don’t forget to notify us of your decisions. Many charities and individuals aren’t aware that they have been named to receive a gift. Informing them helps preserve your intentions and ensures that your beneficiaries are able to follow your wishes.

Steps to protect the people and charities you love

- Review your beneficiary designations periodically because circumstances change throughout your lifetime.

- Alert your beneficiaries that you have a life insurance policy or have named them as beneficiaries of a retirement plan.

- Share the location and details of the policy or plan with your beneficiaries.

As you update your beneficiary designations, consider making a gift of a life insurance policy or retirement plan to the AGA Research Foundation so that we can continue to progress with our mission. Then let us know about your decision so that we can carry out your wishes as intended and thank you for your gift.

We want to hear from you

If you have already named the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy or retirement plan assets, please contact us at [email protected] today. If you are still creating your estate plan, we would be happy to answer any questions you may have about making this type of gift.

If you want to make a lasting impact at the AGA Research Foundation, one of the easiest ways is to name us as a beneficiary of one of your assets, such as your retirement plan, life insurance policy, bank account, or donor-advised fund.

When you do, don’t forget to notify us of your decisions. Many charities and individuals aren’t aware that they have been named to receive a gift. Informing them helps preserve your intentions and ensures that your beneficiaries are able to follow your wishes.

Steps to protect the people and charities you love

- Review your beneficiary designations periodically because circumstances change throughout your lifetime.

- Alert your beneficiaries that you have a life insurance policy or have named them as beneficiaries of a retirement plan.

- Share the location and details of the policy or plan with your beneficiaries.

As you update your beneficiary designations, consider making a gift of a life insurance policy or retirement plan to the AGA Research Foundation so that we can continue to progress with our mission. Then let us know about your decision so that we can carry out your wishes as intended and thank you for your gift.

We want to hear from you

If you have already named the AGA Research Foundation as a beneficiary of a life insurance policy or retirement plan assets, please contact us at [email protected] today. If you are still creating your estate plan, we would be happy to answer any questions you may have about making this type of gift.

Top cases

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. Here’s a preview of a recent popular clinical discussion:

From Rafael Ching Companioni, MD: Malnutrition, elevated liver enzymes, anemia, and malabsorption

“Early 30 year-old female who was initially referred to GI in December 2020 for abnormal liver enzymes ALT 263, AST 114, alk phosp 212, albumin 3.2, bili [within normal limits]. At that time, she reports some diarrhea, few episodes of diarrhea per day, diffuse abdominal pain, ~20 LBs weight loss. She denied herbal medications, OTC medications or other medications. Last travel was 2 years ago to England. No history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia. On examination, cachexia and extremity edema. She has iron deficiency anemia and reactive thrombocytosis. Her initial lipid panel in November 2020, the lipid panel shows total cholesterol 208, LDL 113, triglycerides 227.

“She is still losing weight: 20 lbs from Feb 2021. The liver enzymes elevation resolved. She has anemia, malnutrition and malabsorption. I recommended gluten free diet, MVI, iron pills, protein bars. I had ordered scleroderma workup and SIBO tests today. I am planning to do MRE.”

See how AGA members responded and join the discussion: https://community.gastro.org/posts/24416.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. Here’s a preview of a recent popular clinical discussion:

From Rafael Ching Companioni, MD: Malnutrition, elevated liver enzymes, anemia, and malabsorption

“Early 30 year-old female who was initially referred to GI in December 2020 for abnormal liver enzymes ALT 263, AST 114, alk phosp 212, albumin 3.2, bili [within normal limits]. At that time, she reports some diarrhea, few episodes of diarrhea per day, diffuse abdominal pain, ~20 LBs weight loss. She denied herbal medications, OTC medications or other medications. Last travel was 2 years ago to England. No history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia. On examination, cachexia and extremity edema. She has iron deficiency anemia and reactive thrombocytosis. Her initial lipid panel in November 2020, the lipid panel shows total cholesterol 208, LDL 113, triglycerides 227.

“She is still losing weight: 20 lbs from Feb 2021. The liver enzymes elevation resolved. She has anemia, malnutrition and malabsorption. I recommended gluten free diet, MVI, iron pills, protein bars. I had ordered scleroderma workup and SIBO tests today. I am planning to do MRE.”

See how AGA members responded and join the discussion: https://community.gastro.org/posts/24416.

Physicians with difficult patient scenarios regularly bring their questions to the AGA Community (https://community.gastro.org) to seek advice from colleagues about therapy and disease management options, best practices, and diagnoses. Here’s a preview of a recent popular clinical discussion:

From Rafael Ching Companioni, MD: Malnutrition, elevated liver enzymes, anemia, and malabsorption

“Early 30 year-old female who was initially referred to GI in December 2020 for abnormal liver enzymes ALT 263, AST 114, alk phosp 212, albumin 3.2, bili [within normal limits]. At that time, she reports some diarrhea, few episodes of diarrhea per day, diffuse abdominal pain, ~20 LBs weight loss. She denied herbal medications, OTC medications or other medications. Last travel was 2 years ago to England. No history of anorexia nervosa or bulimia. On examination, cachexia and extremity edema. She has iron deficiency anemia and reactive thrombocytosis. Her initial lipid panel in November 2020, the lipid panel shows total cholesterol 208, LDL 113, triglycerides 227.

“She is still losing weight: 20 lbs from Feb 2021. The liver enzymes elevation resolved. She has anemia, malnutrition and malabsorption. I recommended gluten free diet, MVI, iron pills, protein bars. I had ordered scleroderma workup and SIBO tests today. I am planning to do MRE.”

See how AGA members responded and join the discussion: https://community.gastro.org/posts/24416.

Lessons from COVID-19 and planning for a postpandemic screening surge

It is not an exaggeration to say that everything in my gastroenterology practice changed in response to COVID-19.

Due to the overwhelming surge that Massachusetts saw in the early days of the pandemic, the Department of Public Health issued a moratorium on elective procedures in mid-March of 2020, for both hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers. The moratorium included colorectal cancer (CRC) screenings and other procedures that make up a significant portion of the services we provide to our community. Greater Boston Gastroenterology treats patients in and around the area of Framingham, Mass. – not too far outside of Boston. In our practice, we have seven physicians and three nurse practitioners, with one main office and two satellite offices. By national standards, our practice would be considered small, but it is on the larger side of independent GI physician practices in the commonwealth.

Nationally, moratoria on elective procedures led to one of the steepest drop-offs in screenings for cancers, including colorectal cancer. In late summer of 2020, it was estimated that CRC screenings dropped by 86 percent. Two-thirds of independent GI practices saw a significant decline in patient volume, and many believe that they may not get it back.

However, I’m an optimist in this situation, and I believe that as life gets more normal, people will get back to screenings. With the recommendation by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force that CRC screening should begin at age 45, I expect that there will be an additional increase in screening soon.

Pivoting and developing a reopening plan

Almost immediately after the Department of Public Health issued the moratorium, Greater Boston Gastroenterology began putting together a reopening plan that would allow us to continue treating some patients and prepare for a surge once restrictions were lifted.

Part of our plan was to stay informed by talking with other practices about what they were doing and to stay abreast of policy changes at the local, state, and federal levels.

We also needed to keep our patients informed to alleviate safety concerns. Just prior to our reopening, we developed videos of the precautions that we were taking in all our facilities to assure our patients that we were doing everything possible to keep them safe. We also put information on our website through every stage of reopening so patients could know what to expect at their visits.

Helping our staff feel safe as they returned to work was also an important focus of our reopening plan. We prepared for our eventual reopening by installing safety measures such as plexiglass barriers and HEPA filter machines for our common areas and exam rooms. We also procured access to rapid turnaround polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing that allowed us to regularly test all patients seeking elective procedures. Additionally, we invested in point-of-care antigen tests for the office, and we regularly test all our patient-facing staff.

We had corralled enough personal protective equipment to keep our office infusion services operating with our nurses and patients feeling safe. The preparation allowed us to resume in-person visits almost immediately after the Department of Public Health allowed us to reopen.

Once we reopened, we concentrated on in-office visits for patients who were under 65 and at lower risk for COVID-19, while focusing our telemedicine efforts on patients who were older and at higher risk. We’re now back to seeing all patients who want to have in-office visits and are actually above par for our visits. The number of procedures we have performed in the last 3 months is similar to the 3 months before the pandemic.

During the pandemic, Massachusetts had the best conversion to telehealth in the nation, and it worked well for patients and providers. The key was to use several telehealth apps, as using only one may not work for everyone. Having several options made it likely that we would be able to do complete visits and connect with patients. When we needed to, we switched to telephone visits.

All the physicians and staff in our practice are telemedicine enthusiasts, and it will remain a significant part of our practices as long as Medicare, the state health plans, and commercial payers remain supportive.

Planning for a surge in screenings

There may be a surge in screenings once more people are vaccinated and comfortable getting back into the office, and we’re planning for this as well. We’ve recruited new physicians and have expanded our available hours for procedures at our ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). Surprisingly, we have found that there is a lot of interest from physicians for weekend shifts at the ASC, and we now have a physician waiting list for Saturday procedure time.

With the new lower age for recommended screening, there will be a lag with primary care physicians referring their younger patients. This may provide some time to prepare for an increase in screenings resulting from this new policy.

Another strategy that has worked well for us is to train and develop our advanced practitioners into nonphysician experts in GI and liver disease. Greater Boston Gastroenterology has used this strategy since its founding, and we think our most experienced nurse practitioners could rival any office-based gastroenterologist in their acumen and capabilities.

Over the last 3 years we have transitioned our nonphysician practitioners into the inpatient setting. As a result, consults are completed earlier in the day, and we are better able to help coordinate inpatient procedure scheduling, discharge planning, and outpatient follow-up.

The time we spend on training is worth it. It improves customer service, allows us to book appointments with shorter notice, and overall has a positive effect on our bottom line. Utilizing our advanced providers in this capacity will help us manage any volume increases we see in the near future. In addition, most patients in our community are used to seeing advanced providers in their physician’s office, so the acceptance among our patients is high.

Being flexible and favoring strategic planning

Overall, I think the greatest thing we learned during the pandemic is that we need to be flexible. It was a helpful reminder that, in medicine, things are constantly changing. I remember when passing the GI boards seemed like my final step, but everyone comes to realize it is just the first step in the journey.

As an early-career physician, you should remember the hard work that helped you get to medical school, land a good residency, stand out to get a fellowship, and master your specialty. Harness that personal drive and energy and keep moving forward. Remember that your first job is unlikely to be your last. Try not to see your choices as either/or – either academic or private practice, hospital-employed or self-employed. The boundaries are blurring. We have long careers and face myriad opportunities for professional advancement.

Be patient. Some goals take time to achieve. At each stage be prepared to work hard, use your time wisely, and try not to lose sight of maximizing your professional happiness.

Dr. Dickstein is a practicing gastroenterologist at Greater Boston Gastroenterology in Framingham, Mass., and serves on the executive committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

It is not an exaggeration to say that everything in my gastroenterology practice changed in response to COVID-19.

Due to the overwhelming surge that Massachusetts saw in the early days of the pandemic, the Department of Public Health issued a moratorium on elective procedures in mid-March of 2020, for both hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers. The moratorium included colorectal cancer (CRC) screenings and other procedures that make up a significant portion of the services we provide to our community. Greater Boston Gastroenterology treats patients in and around the area of Framingham, Mass. – not too far outside of Boston. In our practice, we have seven physicians and three nurse practitioners, with one main office and two satellite offices. By national standards, our practice would be considered small, but it is on the larger side of independent GI physician practices in the commonwealth.

Nationally, moratoria on elective procedures led to one of the steepest drop-offs in screenings for cancers, including colorectal cancer. In late summer of 2020, it was estimated that CRC screenings dropped by 86 percent. Two-thirds of independent GI practices saw a significant decline in patient volume, and many believe that they may not get it back.

However, I’m an optimist in this situation, and I believe that as life gets more normal, people will get back to screenings. With the recommendation by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force that CRC screening should begin at age 45, I expect that there will be an additional increase in screening soon.

Pivoting and developing a reopening plan

Almost immediately after the Department of Public Health issued the moratorium, Greater Boston Gastroenterology began putting together a reopening plan that would allow us to continue treating some patients and prepare for a surge once restrictions were lifted.

Part of our plan was to stay informed by talking with other practices about what they were doing and to stay abreast of policy changes at the local, state, and federal levels.

We also needed to keep our patients informed to alleviate safety concerns. Just prior to our reopening, we developed videos of the precautions that we were taking in all our facilities to assure our patients that we were doing everything possible to keep them safe. We also put information on our website through every stage of reopening so patients could know what to expect at their visits.

Helping our staff feel safe as they returned to work was also an important focus of our reopening plan. We prepared for our eventual reopening by installing safety measures such as plexiglass barriers and HEPA filter machines for our common areas and exam rooms. We also procured access to rapid turnaround polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing that allowed us to regularly test all patients seeking elective procedures. Additionally, we invested in point-of-care antigen tests for the office, and we regularly test all our patient-facing staff.

We had corralled enough personal protective equipment to keep our office infusion services operating with our nurses and patients feeling safe. The preparation allowed us to resume in-person visits almost immediately after the Department of Public Health allowed us to reopen.

Once we reopened, we concentrated on in-office visits for patients who were under 65 and at lower risk for COVID-19, while focusing our telemedicine efforts on patients who were older and at higher risk. We’re now back to seeing all patients who want to have in-office visits and are actually above par for our visits. The number of procedures we have performed in the last 3 months is similar to the 3 months before the pandemic.

During the pandemic, Massachusetts had the best conversion to telehealth in the nation, and it worked well for patients and providers. The key was to use several telehealth apps, as using only one may not work for everyone. Having several options made it likely that we would be able to do complete visits and connect with patients. When we needed to, we switched to telephone visits.

All the physicians and staff in our practice are telemedicine enthusiasts, and it will remain a significant part of our practices as long as Medicare, the state health plans, and commercial payers remain supportive.

Planning for a surge in screenings

There may be a surge in screenings once more people are vaccinated and comfortable getting back into the office, and we’re planning for this as well. We’ve recruited new physicians and have expanded our available hours for procedures at our ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). Surprisingly, we have found that there is a lot of interest from physicians for weekend shifts at the ASC, and we now have a physician waiting list for Saturday procedure time.

With the new lower age for recommended screening, there will be a lag with primary care physicians referring their younger patients. This may provide some time to prepare for an increase in screenings resulting from this new policy.

Another strategy that has worked well for us is to train and develop our advanced practitioners into nonphysician experts in GI and liver disease. Greater Boston Gastroenterology has used this strategy since its founding, and we think our most experienced nurse practitioners could rival any office-based gastroenterologist in their acumen and capabilities.

Over the last 3 years we have transitioned our nonphysician practitioners into the inpatient setting. As a result, consults are completed earlier in the day, and we are better able to help coordinate inpatient procedure scheduling, discharge planning, and outpatient follow-up.

The time we spend on training is worth it. It improves customer service, allows us to book appointments with shorter notice, and overall has a positive effect on our bottom line. Utilizing our advanced providers in this capacity will help us manage any volume increases we see in the near future. In addition, most patients in our community are used to seeing advanced providers in their physician’s office, so the acceptance among our patients is high.

Being flexible and favoring strategic planning

Overall, I think the greatest thing we learned during the pandemic is that we need to be flexible. It was a helpful reminder that, in medicine, things are constantly changing. I remember when passing the GI boards seemed like my final step, but everyone comes to realize it is just the first step in the journey.

As an early-career physician, you should remember the hard work that helped you get to medical school, land a good residency, stand out to get a fellowship, and master your specialty. Harness that personal drive and energy and keep moving forward. Remember that your first job is unlikely to be your last. Try not to see your choices as either/or – either academic or private practice, hospital-employed or self-employed. The boundaries are blurring. We have long careers and face myriad opportunities for professional advancement.

Be patient. Some goals take time to achieve. At each stage be prepared to work hard, use your time wisely, and try not to lose sight of maximizing your professional happiness.

Dr. Dickstein is a practicing gastroenterologist at Greater Boston Gastroenterology in Framingham, Mass., and serves on the executive committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

It is not an exaggeration to say that everything in my gastroenterology practice changed in response to COVID-19.

Due to the overwhelming surge that Massachusetts saw in the early days of the pandemic, the Department of Public Health issued a moratorium on elective procedures in mid-March of 2020, for both hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers. The moratorium included colorectal cancer (CRC) screenings and other procedures that make up a significant portion of the services we provide to our community. Greater Boston Gastroenterology treats patients in and around the area of Framingham, Mass. – not too far outside of Boston. In our practice, we have seven physicians and three nurse practitioners, with one main office and two satellite offices. By national standards, our practice would be considered small, but it is on the larger side of independent GI physician practices in the commonwealth.

Nationally, moratoria on elective procedures led to one of the steepest drop-offs in screenings for cancers, including colorectal cancer. In late summer of 2020, it was estimated that CRC screenings dropped by 86 percent. Two-thirds of independent GI practices saw a significant decline in patient volume, and many believe that they may not get it back.

However, I’m an optimist in this situation, and I believe that as life gets more normal, people will get back to screenings. With the recommendation by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force that CRC screening should begin at age 45, I expect that there will be an additional increase in screening soon.

Pivoting and developing a reopening plan

Almost immediately after the Department of Public Health issued the moratorium, Greater Boston Gastroenterology began putting together a reopening plan that would allow us to continue treating some patients and prepare for a surge once restrictions were lifted.

Part of our plan was to stay informed by talking with other practices about what they were doing and to stay abreast of policy changes at the local, state, and federal levels.

We also needed to keep our patients informed to alleviate safety concerns. Just prior to our reopening, we developed videos of the precautions that we were taking in all our facilities to assure our patients that we were doing everything possible to keep them safe. We also put information on our website through every stage of reopening so patients could know what to expect at their visits.

Helping our staff feel safe as they returned to work was also an important focus of our reopening plan. We prepared for our eventual reopening by installing safety measures such as plexiglass barriers and HEPA filter machines for our common areas and exam rooms. We also procured access to rapid turnaround polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing that allowed us to regularly test all patients seeking elective procedures. Additionally, we invested in point-of-care antigen tests for the office, and we regularly test all our patient-facing staff.

We had corralled enough personal protective equipment to keep our office infusion services operating with our nurses and patients feeling safe. The preparation allowed us to resume in-person visits almost immediately after the Department of Public Health allowed us to reopen.

Once we reopened, we concentrated on in-office visits for patients who were under 65 and at lower risk for COVID-19, while focusing our telemedicine efforts on patients who were older and at higher risk. We’re now back to seeing all patients who want to have in-office visits and are actually above par for our visits. The number of procedures we have performed in the last 3 months is similar to the 3 months before the pandemic.

During the pandemic, Massachusetts had the best conversion to telehealth in the nation, and it worked well for patients and providers. The key was to use several telehealth apps, as using only one may not work for everyone. Having several options made it likely that we would be able to do complete visits and connect with patients. When we needed to, we switched to telephone visits.

All the physicians and staff in our practice are telemedicine enthusiasts, and it will remain a significant part of our practices as long as Medicare, the state health plans, and commercial payers remain supportive.

Planning for a surge in screenings

There may be a surge in screenings once more people are vaccinated and comfortable getting back into the office, and we’re planning for this as well. We’ve recruited new physicians and have expanded our available hours for procedures at our ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). Surprisingly, we have found that there is a lot of interest from physicians for weekend shifts at the ASC, and we now have a physician waiting list for Saturday procedure time.

With the new lower age for recommended screening, there will be a lag with primary care physicians referring their younger patients. This may provide some time to prepare for an increase in screenings resulting from this new policy.

Another strategy that has worked well for us is to train and develop our advanced practitioners into nonphysician experts in GI and liver disease. Greater Boston Gastroenterology has used this strategy since its founding, and we think our most experienced nurse practitioners could rival any office-based gastroenterologist in their acumen and capabilities.

Over the last 3 years we have transitioned our nonphysician practitioners into the inpatient setting. As a result, consults are completed earlier in the day, and we are better able to help coordinate inpatient procedure scheduling, discharge planning, and outpatient follow-up.

The time we spend on training is worth it. It improves customer service, allows us to book appointments with shorter notice, and overall has a positive effect on our bottom line. Utilizing our advanced providers in this capacity will help us manage any volume increases we see in the near future. In addition, most patients in our community are used to seeing advanced providers in their physician’s office, so the acceptance among our patients is high.

Being flexible and favoring strategic planning

Overall, I think the greatest thing we learned during the pandemic is that we need to be flexible. It was a helpful reminder that, in medicine, things are constantly changing. I remember when passing the GI boards seemed like my final step, but everyone comes to realize it is just the first step in the journey.

As an early-career physician, you should remember the hard work that helped you get to medical school, land a good residency, stand out to get a fellowship, and master your specialty. Harness that personal drive and energy and keep moving forward. Remember that your first job is unlikely to be your last. Try not to see your choices as either/or – either academic or private practice, hospital-employed or self-employed. The boundaries are blurring. We have long careers and face myriad opportunities for professional advancement.

Be patient. Some goals take time to achieve. At each stage be prepared to work hard, use your time wisely, and try not to lose sight of maximizing your professional happiness.

Dr. Dickstein is a practicing gastroenterologist at Greater Boston Gastroenterology in Framingham, Mass., and serves on the executive committee of the Digestive Health Physicians Association. He has no conflicts to declare.

Telemedicine is poised to drive new models of care

Telemedicine has been proposed as a solution for an array of health care access problems over decades of gradual growth. The vast ramping up of , according to an update at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The cat is out of the bag,” said Jaspal Singh, MD, professor of medicine, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. Due to changes in access and reimbursement to telemedicine driven by the pandemic, he said, “we now have permission to explore new models of care.”

Prior to February 2020, telemedicine was crawling forward at a leisurely pace, according to Dr. Singh. After March 2020, it broke into a run due to enormous demand and was met by a rapid response from the U.S. Congress. The first of four legislative bills that directly or indirectly supported telemedicine was passed on March 6, 2020.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services responded in kind, making modifications in a number of rules that removed obstacles to telehealth. One modification on April 6, 2020, for example, removed the requirement for a preexisting relationship between the clinician and patient, Dr. Singh said. The CMS also subsequently modified reimbursement policies in order to make telemedicine more tenable for physicians.

Given the risk of contagion from face-to-face encounters, telemedicine in the early days of the pandemic was not just attractive but the only practical and safe approach to medical care in many circumstances. Physicians and patients were anxious for health care that did not require in-office visits even though many critical issues for telemedicine, including its relative effectiveness, had not yet been fully evaluated.

Much has been learned regarding the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine during the pandemic, but Dr. Singh noted that quality of care relative to in-person visits remains weakly supported for most indications. Indeed, he outlined sizable list of incompletely resolved issues, including optimal payment models, management of privacy concerns, and how to balance advantages to disadvantages.

For patients and physicians, the strengths of telemedicine include greater convenience made possible by the elimination of travel and waiting rooms. For the health care system, it can include less infrastructure and overhead. For many physicians, telemedicine might be perceived as more efficient.

On the other hand, some patients might feel that a clinical encounter is incomplete without a physical examination even when the physician does not feel the physical examination is needed, according to Dr. Singh. He cited a survey suggesting nearly half of patients expressed concern about a lack of connection to health care providers following a virtual visit.

In the same 2020 National Poll on Healthy Aging 2020 survey conducted by the University of Michigan 67% of respondents reported that the quality of care was not as good as that provided by in-patient visits, and 24% expressed concern about privacy. However, at the time the poll was taken in May 2020, experience with telemedicine among many of the respondents may have been limited. As telemedicine is integrated into routine care, perceptions might change as experience increases.

A distinction between telemedicine in routine care and telemedicine as a strategy to respond to a pandemic is important, Dr. Singh indicated. Dr. Singh was the lead author for a position paper on telemedicine for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 5 years ago, but he acknowledged that models of care might differ when responding to abnormal surges in health care demand.

The surge in demand for COVID-19–related care engendered numerous innovative solutions. As examples, Dr. Singh recounted how a virtual hospital was created at his own institution. In a published study, 1,477 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 over a 6-week period remained at home and received care in a virtual observation unit (VCU) or a virtual acute care unit (VACU) . Only a small percentage required eventual hospital admission. In the VACU, patients were able to receive advanced care including IV fluids and some form of respiratory support .

It is unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic will change telemedicine. Now, with declining cases of the infection, telemedicine is back to a walk after the sprint required during the height of the pandemic, according to Dr. Singh. However, Dr. Singh thinks many physicians and patients will have a different perception of telemedicine after the widespread exposure to this type of care.

In terms of the relative role of in-patient and virtual visits across indications, “we do not know how this will play out, but we will probably end up toggling between the two,” Dr. Singh said.

This is an area that is being followed closely by the CHEST Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, according to Kathleen Sarmiento, MD, director, VISN 21 Sleep Clinical Resource Hub for the San Francisco VA Health Care System. A member of that committee and moderator of the session in which Dr. Singh spoke,

Dr. Sarmiento called the effort to bring permanent coverage of telehealth services “the shared responsibility of every medical society engaged in advocacy.”

However, she cautioned that there might be intended and unintended consequences from telehealth that require analysis to develop policies that are in the best interests of effective care. She said, the “ACCP, along with its sister societies, does have a role in supporting the evaluation of the impact of these changes on both patients and providers in the fields of pulmonary medicine, critical care, and sleep medicine.”

Dr. Singh reports a financial relationship with AstraZeneca. Dr. Sarmiento reports no relevant financial relationship with AstraZeneca.

Telemedicine has been proposed as a solution for an array of health care access problems over decades of gradual growth. The vast ramping up of , according to an update at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The cat is out of the bag,” said Jaspal Singh, MD, professor of medicine, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. Due to changes in access and reimbursement to telemedicine driven by the pandemic, he said, “we now have permission to explore new models of care.”

Prior to February 2020, telemedicine was crawling forward at a leisurely pace, according to Dr. Singh. After March 2020, it broke into a run due to enormous demand and was met by a rapid response from the U.S. Congress. The first of four legislative bills that directly or indirectly supported telemedicine was passed on March 6, 2020.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services responded in kind, making modifications in a number of rules that removed obstacles to telehealth. One modification on April 6, 2020, for example, removed the requirement for a preexisting relationship between the clinician and patient, Dr. Singh said. The CMS also subsequently modified reimbursement policies in order to make telemedicine more tenable for physicians.

Given the risk of contagion from face-to-face encounters, telemedicine in the early days of the pandemic was not just attractive but the only practical and safe approach to medical care in many circumstances. Physicians and patients were anxious for health care that did not require in-office visits even though many critical issues for telemedicine, including its relative effectiveness, had not yet been fully evaluated.

Much has been learned regarding the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine during the pandemic, but Dr. Singh noted that quality of care relative to in-person visits remains weakly supported for most indications. Indeed, he outlined sizable list of incompletely resolved issues, including optimal payment models, management of privacy concerns, and how to balance advantages to disadvantages.

For patients and physicians, the strengths of telemedicine include greater convenience made possible by the elimination of travel and waiting rooms. For the health care system, it can include less infrastructure and overhead. For many physicians, telemedicine might be perceived as more efficient.

On the other hand, some patients might feel that a clinical encounter is incomplete without a physical examination even when the physician does not feel the physical examination is needed, according to Dr. Singh. He cited a survey suggesting nearly half of patients expressed concern about a lack of connection to health care providers following a virtual visit.

In the same 2020 National Poll on Healthy Aging 2020 survey conducted by the University of Michigan 67% of respondents reported that the quality of care was not as good as that provided by in-patient visits, and 24% expressed concern about privacy. However, at the time the poll was taken in May 2020, experience with telemedicine among many of the respondents may have been limited. As telemedicine is integrated into routine care, perceptions might change as experience increases.

A distinction between telemedicine in routine care and telemedicine as a strategy to respond to a pandemic is important, Dr. Singh indicated. Dr. Singh was the lead author for a position paper on telemedicine for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 5 years ago, but he acknowledged that models of care might differ when responding to abnormal surges in health care demand.

The surge in demand for COVID-19–related care engendered numerous innovative solutions. As examples, Dr. Singh recounted how a virtual hospital was created at his own institution. In a published study, 1,477 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 over a 6-week period remained at home and received care in a virtual observation unit (VCU) or a virtual acute care unit (VACU) . Only a small percentage required eventual hospital admission. In the VACU, patients were able to receive advanced care including IV fluids and some form of respiratory support .

It is unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic will change telemedicine. Now, with declining cases of the infection, telemedicine is back to a walk after the sprint required during the height of the pandemic, according to Dr. Singh. However, Dr. Singh thinks many physicians and patients will have a different perception of telemedicine after the widespread exposure to this type of care.

In terms of the relative role of in-patient and virtual visits across indications, “we do not know how this will play out, but we will probably end up toggling between the two,” Dr. Singh said.

This is an area that is being followed closely by the CHEST Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, according to Kathleen Sarmiento, MD, director, VISN 21 Sleep Clinical Resource Hub for the San Francisco VA Health Care System. A member of that committee and moderator of the session in which Dr. Singh spoke,

Dr. Sarmiento called the effort to bring permanent coverage of telehealth services “the shared responsibility of every medical society engaged in advocacy.”

However, she cautioned that there might be intended and unintended consequences from telehealth that require analysis to develop policies that are in the best interests of effective care. She said, the “ACCP, along with its sister societies, does have a role in supporting the evaluation of the impact of these changes on both patients and providers in the fields of pulmonary medicine, critical care, and sleep medicine.”

Dr. Singh reports a financial relationship with AstraZeneca. Dr. Sarmiento reports no relevant financial relationship with AstraZeneca.

Telemedicine has been proposed as a solution for an array of health care access problems over decades of gradual growth. The vast ramping up of , according to an update at the annual health policy and advocacy conference sponsored by the American College of Chest Physicians.

“The cat is out of the bag,” said Jaspal Singh, MD, professor of medicine, Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C. Due to changes in access and reimbursement to telemedicine driven by the pandemic, he said, “we now have permission to explore new models of care.”

Prior to February 2020, telemedicine was crawling forward at a leisurely pace, according to Dr. Singh. After March 2020, it broke into a run due to enormous demand and was met by a rapid response from the U.S. Congress. The first of four legislative bills that directly or indirectly supported telemedicine was passed on March 6, 2020.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services responded in kind, making modifications in a number of rules that removed obstacles to telehealth. One modification on April 6, 2020, for example, removed the requirement for a preexisting relationship between the clinician and patient, Dr. Singh said. The CMS also subsequently modified reimbursement policies in order to make telemedicine more tenable for physicians.

Given the risk of contagion from face-to-face encounters, telemedicine in the early days of the pandemic was not just attractive but the only practical and safe approach to medical care in many circumstances. Physicians and patients were anxious for health care that did not require in-office visits even though many critical issues for telemedicine, including its relative effectiveness, had not yet been fully evaluated.

Much has been learned regarding the feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine during the pandemic, but Dr. Singh noted that quality of care relative to in-person visits remains weakly supported for most indications. Indeed, he outlined sizable list of incompletely resolved issues, including optimal payment models, management of privacy concerns, and how to balance advantages to disadvantages.

For patients and physicians, the strengths of telemedicine include greater convenience made possible by the elimination of travel and waiting rooms. For the health care system, it can include less infrastructure and overhead. For many physicians, telemedicine might be perceived as more efficient.

On the other hand, some patients might feel that a clinical encounter is incomplete without a physical examination even when the physician does not feel the physical examination is needed, according to Dr. Singh. He cited a survey suggesting nearly half of patients expressed concern about a lack of connection to health care providers following a virtual visit.

In the same 2020 National Poll on Healthy Aging 2020 survey conducted by the University of Michigan 67% of respondents reported that the quality of care was not as good as that provided by in-patient visits, and 24% expressed concern about privacy. However, at the time the poll was taken in May 2020, experience with telemedicine among many of the respondents may have been limited. As telemedicine is integrated into routine care, perceptions might change as experience increases.

A distinction between telemedicine in routine care and telemedicine as a strategy to respond to a pandemic is important, Dr. Singh indicated. Dr. Singh was the lead author for a position paper on telemedicine for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine 5 years ago, but he acknowledged that models of care might differ when responding to abnormal surges in health care demand.

The surge in demand for COVID-19–related care engendered numerous innovative solutions. As examples, Dr. Singh recounted how a virtual hospital was created at his own institution. In a published study, 1,477 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 over a 6-week period remained at home and received care in a virtual observation unit (VCU) or a virtual acute care unit (VACU) . Only a small percentage required eventual hospital admission. In the VACU, patients were able to receive advanced care including IV fluids and some form of respiratory support .

It is unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic will change telemedicine. Now, with declining cases of the infection, telemedicine is back to a walk after the sprint required during the height of the pandemic, according to Dr. Singh. However, Dr. Singh thinks many physicians and patients will have a different perception of telemedicine after the widespread exposure to this type of care.

In terms of the relative role of in-patient and virtual visits across indications, “we do not know how this will play out, but we will probably end up toggling between the two,” Dr. Singh said.

This is an area that is being followed closely by the CHEST Health Policy and Advocacy Committee, according to Kathleen Sarmiento, MD, director, VISN 21 Sleep Clinical Resource Hub for the San Francisco VA Health Care System. A member of that committee and moderator of the session in which Dr. Singh spoke,

Dr. Sarmiento called the effort to bring permanent coverage of telehealth services “the shared responsibility of every medical society engaged in advocacy.”

However, she cautioned that there might be intended and unintended consequences from telehealth that require analysis to develop policies that are in the best interests of effective care. She said, the “ACCP, along with its sister societies, does have a role in supporting the evaluation of the impact of these changes on both patients and providers in the fields of pulmonary medicine, critical care, and sleep medicine.”

Dr. Singh reports a financial relationship with AstraZeneca. Dr. Sarmiento reports no relevant financial relationship with AstraZeneca.

FROM A HEALTH POLICY AND ADVOCACY CONFERENCE

Low-dose nitrous oxide shows benefit for resistant depression

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

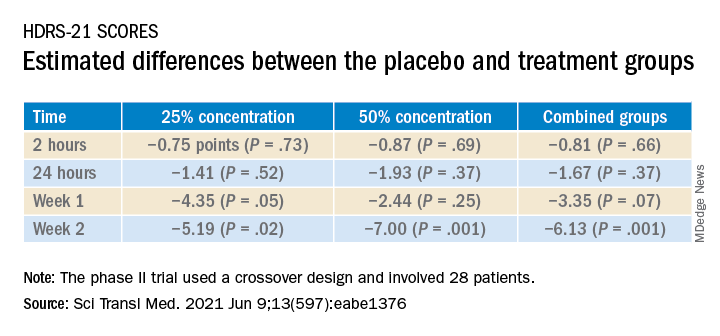

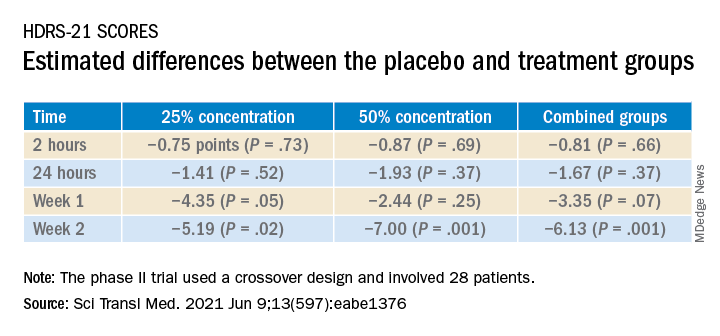

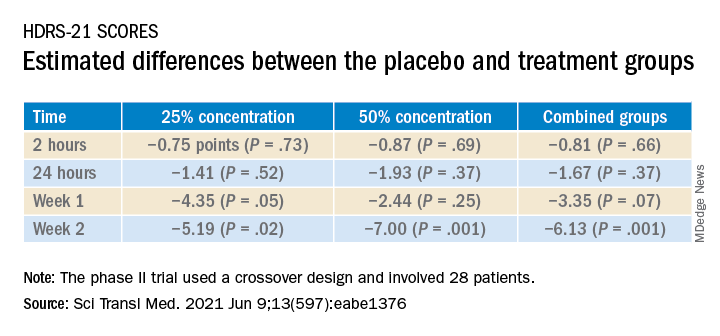

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”

Dr. McIntyre, also the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, found it “interesting” that “almost 20% of the sample had previously had suboptimal outcomes to ketamine and/or neurostimulation, meaning these patients had serious refractory illness, but the benefit [of nitrous oxide] was sustained at 2 weeks.”

Studies of the use of nitrous oxide for patients with bipolar depression “would be warranted, since it appears generally safe and well tolerated,” said Dr. McIntyre, director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance.

The study was sponsored by an award to Dr. Nagele from the NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and an award to Dr. Nagele and other coauthors from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Nagele receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health the American Foundation for Prevention of Suicide, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; has received research funding and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics; and has previously filed for intellectual property protection related to the use of nitrous oxide in major depression. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and Abbvie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”

Dr. McIntyre, also the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, found it “interesting” that “almost 20% of the sample had previously had suboptimal outcomes to ketamine and/or neurostimulation, meaning these patients had serious refractory illness, but the benefit [of nitrous oxide] was sustained at 2 weeks.”

Studies of the use of nitrous oxide for patients with bipolar depression “would be warranted, since it appears generally safe and well tolerated,” said Dr. McIntyre, director of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance.

The study was sponsored by an award to Dr. Nagele from the NARSAD Independent Investigator Award from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation and an award to Dr. Nagele and other coauthors from the Taylor Family Institute for Innovative Psychiatric Research at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Nagele receives funding from the National Institute of Mental Health the American Foundation for Prevention of Suicide, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; has received research funding and honoraria from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics; and has previously filed for intellectual property protection related to the use of nitrous oxide in major depression. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original article. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and Abbvie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 1-hour treatment with a low concentration of nitrous oxide, commonly known as “laughing gas,” appears to relieve symptoms of treatment-resistant major depression (TRMD), with effects lasting as long as several weeks, new research suggests.

In a trial with a crossover design, investigators randomly assigned 28 patients with severe TRMD to receive a single 1-hour inhalation of placebo or nitrous oxide once a month over a 3-month period. Participants received an inhalation of placebo; a 25% concentration of nitrous oxide; and a 50% concentration of nitrous oxide. Sessions were conducted 4 weeks apart.

Both doses of nitrous oxide were associated with substantial improvement in depressive symptoms for roughly 85% of participants. However, the 25% concentration had a lower risk for adverse effects, which included sedation, nausea, and mild dissociation, compared to the 50% concentration.

“Twenty-five percent nitrous oxide has similar efficacy, compared to 50% nitrous oxide, and reduced side effects fourfold,” lead author Peter Nagele, MD, MSc, chair and professor of anesthesia and critical care, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“We also observed that many patients had a 2-week improvement of depressive symptoms after a nitrous oxide treatment,” said Dr. Nagele, who also is professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience.

The study was published online June 9 in Science Translational Medicine.

Further refinement

A previous proof-of-principle study conducted by the same researchers demonstrated that a 1-hour inhalation of 50% nitrous oxide had rapid antidepressant effects for patients with TRMD.

The current phase 2 trial “is a follow-up study to our earlier 2015 pilot trial and was designed to further refine the dose of nitrous oxide needed for antidepressant efficacy,” Dr. Nagele said.

“An important secondary aim [of the current study] was to determine whether a lower dose – 25% – would reduce side effects, and a third aim was to determine how long the antidepressants effects last,” he explained.

To investigate, the researchers enrolled 28 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age 39 years [26-68 years]; 71% women; 96% White) to have three inhalation sessions (placebo, 25%, and 50% nitrous oxide) at 4-week intervals. Twenty patients completed all three inhalation sessions, and four completed ≥1 treatment.

Participants had “sustained and refractory depressive illness,” with a mean illness lifetime duration of 17.5 years and an extensive history of antidepressant drug failure (median, 4.5 [2-10] adequate-dose/duration antidepressants).

Some patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy, or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or had received ketamine (4%, 8%, 13%, and 8%, respectively).

The primary outcome was improvement on the 21-item Hamilton Depression rating Scale (HDRS-21) score over a 2-week observation period.

‘Stronger evidence’

Compared to placebo, nitrous oxide significantly improved depressive symptoms (P = .01). There was no significant difference between the 25% and the 50% concentrations (P = .58).

The estimated difference in HDRS-21 scores between the placebo and various treatment groups are shown in the following table.

To ensure there where were carryover effects between the two doses, the researchers performed an analysis to ascertain whether order of receipt of the higher dose was related to the 2-week HDRS-21 score; they found no significant effect of trial order (P = .22).

The 20 patients who completed the entire course of treatment “experienced a clinically significant improvement in depressive symptoms from a median baseline HDRS-21 score of 20.5 (IQR, 19.0 to 25.5) to 8.5 (IQR, 2.0 to 16.0) at study completion, corresponding to a median change of −11.0 points (IQR, −3.3 to −14.0 points; P < .0001) after the 3-month study period,” the investigators noted.

The types of treatment response and improvement in depressive symptoms from baseline to study completion are listed in the table below.

There were statistically significant differences in adverse events between the two treatment doses; 47 events occurred following inhalation of the 50% concentration, compared to 11 after inhalation of the 25% concentration. There were six adverse events after inhalation of placebo (P < .0001).

“None of the adverse events were serious, and nearly all occurred either during or immediately after the treatment session and resolved within several hours,” the authors reported.

“We need to be remindful that – despite the exciting results of the study – the study was small and cannot be considered definitive evidence; as such, it is too early to advocate for the use of nitrous oxide in everyday clinical practice,” Dr. Nagele said.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the current findings, he stated.

Rapid-acting antidepressants

Commenting on the study in an interview, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit at Toronto Western Hospital, noted that the research into nitrous oxide is “part of an interest in rapid-acting antidepressants.”