User login

Pediatricians can effectively promote gun safety

When pediatricians and other pediatric providers are given training and resource materials, levels of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance about firearm safety increase significantly, according to two new studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With the rise in firearm sales and injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that pediatricians address the firearm epidemic,” said Alexandra Byrne, MD, a pediatric resident at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who presented one of the studies.

There were 4.3 million more firearms purchased from March through July 2020 than expected, a recent study estimates, and 4,075 more firearm injuries than expected from April through July 2020.

In states with more excess purchases, firearm injuries related to domestic violence increased in April (rate ratio, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.32-5.93) and May (RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.19-2.91) 2020. However, excess gun purchases had no effect on rates of firearm violence outside the home.

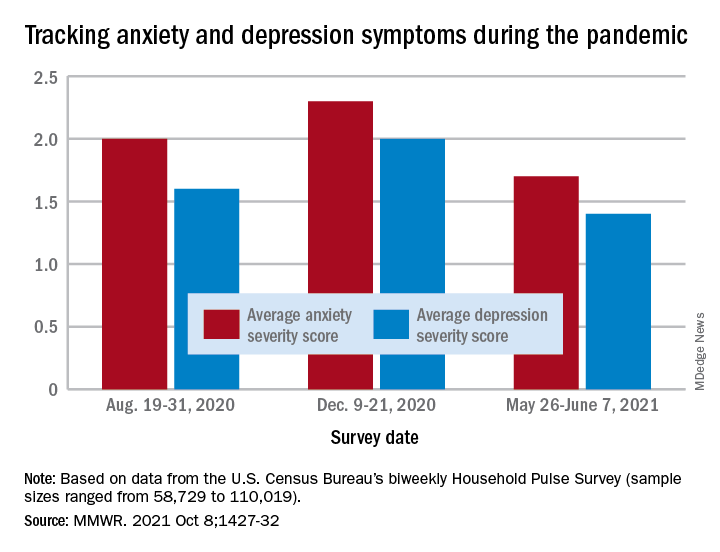

In addition to the link between firearms in the home and domestic violence, they are also linked to a three- to fourfold greater risk for teen suicide, and both depression and suicidal thoughts have risen in teens during the pandemic.

“The data are pretty clear that if you have an unlocked, loaded weapon in your home, and you have a kid who’s depressed or anxious or dysregulated or doing maladaptive things for the pandemic, they’re much more likely to inadvertently take their own or someone else’s life by grabbing [a gun],” said Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

However, there is no difference in gun ownership or gun-safety measures between homes with and without at-risk children, previous research shows.

Training, guidance, and locks

Previous research has also shown that there has been a reluctance by pediatricians to conduct firearm screenings and counsel parents about gun safety in the home.

For their two-step program, Dr. Byrne’s team used a plan-do-study-act approach. They started by providing training on firearm safety, evidence-based recommendations for firearm screening, and anticipatory guidance regarding safe firearm storage to members of the general pediatrics division at the University of Florida. And they supplied clinics with free firearm locks.

Next they supplied clinics with posters and educational cards from the Be SMART campaign, an initiative of the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, which provides materials for anyone, including physicians, to use.

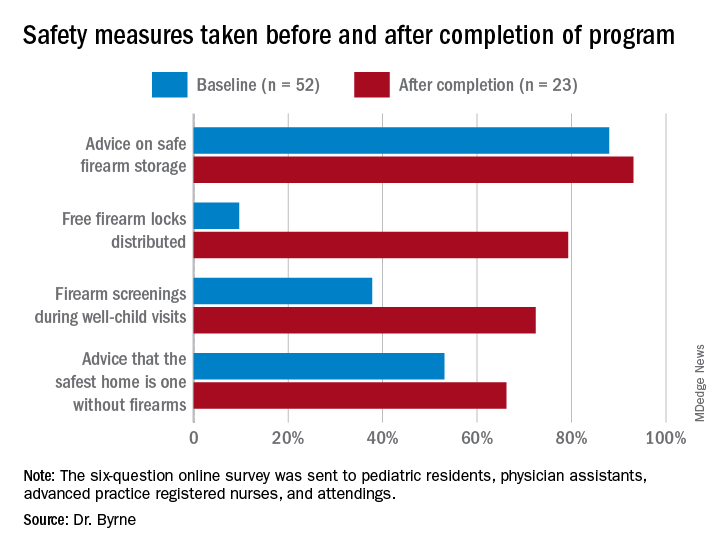

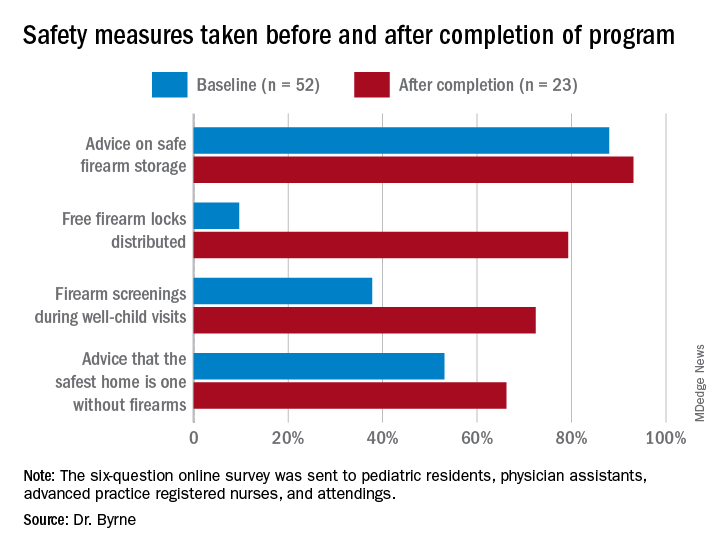

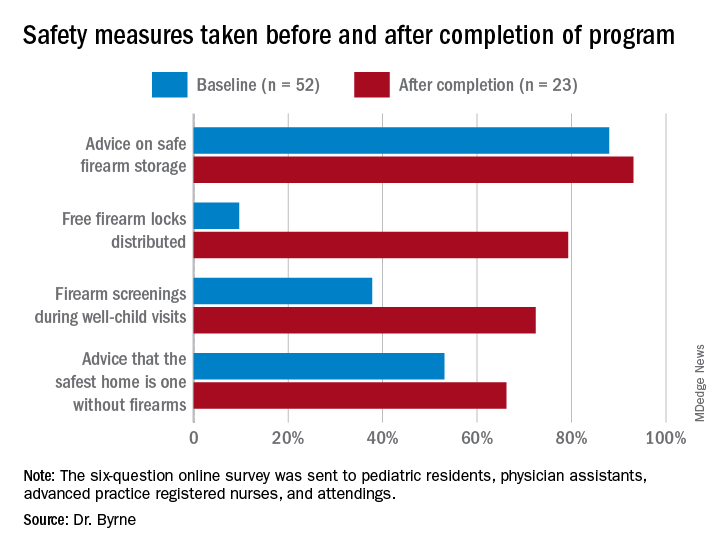

During their study, the researchers sent three anonymous six-question online surveys – at baseline and 3 to 4 months after each of the two steps – to pediatric residents, physician assistants, advanced practice registered nurses, and attendings to assess the project. There were 52 responses to the first survey, for a response rate of 58.4%, 42 responses to the second survey, for a response rate of 47.2%, and 23 responses to the third survey, for a rate of response 25.8%.

The program nearly doubled screenings during well-child visits and dramatically increased the proportion of families who received a firearm lock when they told providers they had a firearm at home.

Previous research has shown “a significant increase in safe firearm storage when firearm locks were provided to families in clinic compared to verbal counseling alone,” Dr. Byrne said. “We know that safe firearm storage reduces injuries. Roughly one in three children in the United States lives in a home with a firearm. Individuals with a firearm are at two times the risk of homicide and three to four times the risk of suicide, so it is essential we further study how pediatricians can be most effective when it comes to firearm counseling.”

The difference in lock distribution as a result of the program is a “tremendous increase,” said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“Locks could go a long way to minimizing the risk,” he said in an interview, adding that nearly half of all teen suicide deaths that occurred over a decade in Houston involved a firearm.

Adding a social-history component

A program to increase firearm screening was also presented at the AAP conference.

After random review of medical records from 30 patients admitted to the hospital documented zero firearm screenings, Marjorie Farrington, MD, and Samantha Gunkelman, MD, from Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio, implemented a program that they hope will increase firearm screenings during inpatient admissions to at least 50%.

They started their ongoing program in April 2020 by adding a social-history component to the history and physical (H&P) exam template and educating residents on how to screen and included guidance on safe firearm storage.

They also had physicians with firearm expertise give gun-safety lectures, and they plan to involve the Family Resource Center at their hospital in the creation of resources that can be incorporated into discharge instructions.

From April 2020 to June 2021, after the addition to the H&P template, 63% of the 5196 patients admitted to the hospital underwent a firearm screening. Of the 25% of patients who reported guns at home, 3% were not storing their firearms safely.

The pair used the “Store It Safe” Physician Handout provided by the Ohio chapter of the AAP.

Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic.

The BulletPoints Project — developed by the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis — can also help physicians talk to patients about guns.

“Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic,” Dr. Byrne said in an interview. “Additionally, it is a challenging topic that can often be met with resistance from patients and families. Lack of time during visits is also a huge barrier.”

Lack of training is an obstacle to greater firearm screenings, Dr. Greeley agreed, as are the feeling that guidance simply won’t make a difference and concerns about political pressure and divineness. The lack of research on firearm injuries and the impact of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance is a challenge, he added, although that is starting to change.

Pediatricians need education on how to make a difference when it comes to firearm safety, and should follow AAP guidelines, Dr. Greeley said.

Counseling on firearm safety is in the same category as immunizations, seatbelts, substance use, helmets, and other public-health issues that are important to address at visits, regardless of how difficult it might be, Dr. Breuner told this news organization.

“It is our mission, as pediatricians, to provide every ounce of prevention in our well-child and anticipatory guidance visits,” she said. “It’s our job, so we shouldn’t shy away from it even though it’s hard.”

Doctors are more comfortable discussing firearm safety if they are firearm owners, previous research has shown, so she advises pediatricians who feel unqualified to discuss firearms to seek guidance from their peers on how to approach screenings and anticipatory guidance, she noted.

The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause. The populations are often very different than private practice.

Both of these studies were conducted at single institutions and might not reflect what would work in private clinics.

“The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause,” Dr. Greeley said. “The populations are often very different than private practice. I think that there is still a lot that remains unknown about decreasing household firearm injury and death.”

And the degree to which findings from these two gun-safety programs can be generalized to other academic centers or children’s hospitals is unclear.

“There are states where, I suspect, firearm screening is much more common. Some states have very pro-firearm cultures and others are anti-firearm,” Dr. Greeley said. “There are also likely differences within states,” particularly between urban and rural regions.

“Firearms are often a very personal issue for families, and pediatricians in ‘pro-firearm’ communities may have greater resistance to working on this,” he pointed out.

Nevertheless, Dr. Greeley said, “this is a promising strategy that could be part of a broad injury prevention initiative.”

Neither study noted any external funding. Dr. Byrne is a member of the Moms Demand Action Gainesville Chapter, which donated the firearm locks for the project. Dr. Breuner, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Farrington have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When pediatricians and other pediatric providers are given training and resource materials, levels of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance about firearm safety increase significantly, according to two new studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With the rise in firearm sales and injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that pediatricians address the firearm epidemic,” said Alexandra Byrne, MD, a pediatric resident at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who presented one of the studies.

There were 4.3 million more firearms purchased from March through July 2020 than expected, a recent study estimates, and 4,075 more firearm injuries than expected from April through July 2020.

In states with more excess purchases, firearm injuries related to domestic violence increased in April (rate ratio, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.32-5.93) and May (RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.19-2.91) 2020. However, excess gun purchases had no effect on rates of firearm violence outside the home.

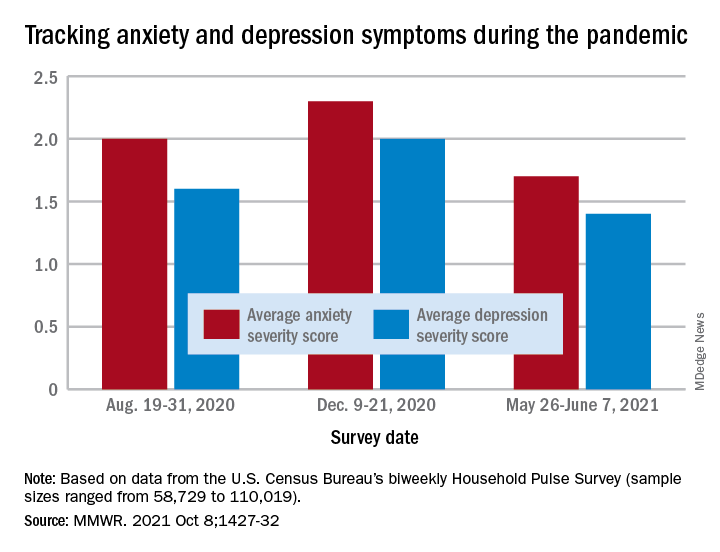

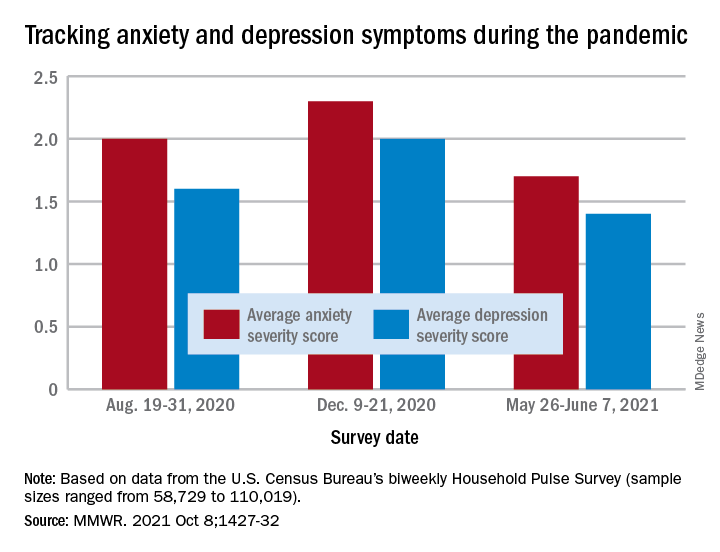

In addition to the link between firearms in the home and domestic violence, they are also linked to a three- to fourfold greater risk for teen suicide, and both depression and suicidal thoughts have risen in teens during the pandemic.

“The data are pretty clear that if you have an unlocked, loaded weapon in your home, and you have a kid who’s depressed or anxious or dysregulated or doing maladaptive things for the pandemic, they’re much more likely to inadvertently take their own or someone else’s life by grabbing [a gun],” said Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

However, there is no difference in gun ownership or gun-safety measures between homes with and without at-risk children, previous research shows.

Training, guidance, and locks

Previous research has also shown that there has been a reluctance by pediatricians to conduct firearm screenings and counsel parents about gun safety in the home.

For their two-step program, Dr. Byrne’s team used a plan-do-study-act approach. They started by providing training on firearm safety, evidence-based recommendations for firearm screening, and anticipatory guidance regarding safe firearm storage to members of the general pediatrics division at the University of Florida. And they supplied clinics with free firearm locks.

Next they supplied clinics with posters and educational cards from the Be SMART campaign, an initiative of the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, which provides materials for anyone, including physicians, to use.

During their study, the researchers sent three anonymous six-question online surveys – at baseline and 3 to 4 months after each of the two steps – to pediatric residents, physician assistants, advanced practice registered nurses, and attendings to assess the project. There were 52 responses to the first survey, for a response rate of 58.4%, 42 responses to the second survey, for a response rate of 47.2%, and 23 responses to the third survey, for a rate of response 25.8%.

The program nearly doubled screenings during well-child visits and dramatically increased the proportion of families who received a firearm lock when they told providers they had a firearm at home.

Previous research has shown “a significant increase in safe firearm storage when firearm locks were provided to families in clinic compared to verbal counseling alone,” Dr. Byrne said. “We know that safe firearm storage reduces injuries. Roughly one in three children in the United States lives in a home with a firearm. Individuals with a firearm are at two times the risk of homicide and three to four times the risk of suicide, so it is essential we further study how pediatricians can be most effective when it comes to firearm counseling.”

The difference in lock distribution as a result of the program is a “tremendous increase,” said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“Locks could go a long way to minimizing the risk,” he said in an interview, adding that nearly half of all teen suicide deaths that occurred over a decade in Houston involved a firearm.

Adding a social-history component

A program to increase firearm screening was also presented at the AAP conference.

After random review of medical records from 30 patients admitted to the hospital documented zero firearm screenings, Marjorie Farrington, MD, and Samantha Gunkelman, MD, from Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio, implemented a program that they hope will increase firearm screenings during inpatient admissions to at least 50%.

They started their ongoing program in April 2020 by adding a social-history component to the history and physical (H&P) exam template and educating residents on how to screen and included guidance on safe firearm storage.

They also had physicians with firearm expertise give gun-safety lectures, and they plan to involve the Family Resource Center at their hospital in the creation of resources that can be incorporated into discharge instructions.

From April 2020 to June 2021, after the addition to the H&P template, 63% of the 5196 patients admitted to the hospital underwent a firearm screening. Of the 25% of patients who reported guns at home, 3% were not storing their firearms safely.

The pair used the “Store It Safe” Physician Handout provided by the Ohio chapter of the AAP.

Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic.

The BulletPoints Project — developed by the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis — can also help physicians talk to patients about guns.

“Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic,” Dr. Byrne said in an interview. “Additionally, it is a challenging topic that can often be met with resistance from patients and families. Lack of time during visits is also a huge barrier.”

Lack of training is an obstacle to greater firearm screenings, Dr. Greeley agreed, as are the feeling that guidance simply won’t make a difference and concerns about political pressure and divineness. The lack of research on firearm injuries and the impact of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance is a challenge, he added, although that is starting to change.

Pediatricians need education on how to make a difference when it comes to firearm safety, and should follow AAP guidelines, Dr. Greeley said.

Counseling on firearm safety is in the same category as immunizations, seatbelts, substance use, helmets, and other public-health issues that are important to address at visits, regardless of how difficult it might be, Dr. Breuner told this news organization.

“It is our mission, as pediatricians, to provide every ounce of prevention in our well-child and anticipatory guidance visits,” she said. “It’s our job, so we shouldn’t shy away from it even though it’s hard.”

Doctors are more comfortable discussing firearm safety if they are firearm owners, previous research has shown, so she advises pediatricians who feel unqualified to discuss firearms to seek guidance from their peers on how to approach screenings and anticipatory guidance, she noted.

The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause. The populations are often very different than private practice.

Both of these studies were conducted at single institutions and might not reflect what would work in private clinics.

“The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause,” Dr. Greeley said. “The populations are often very different than private practice. I think that there is still a lot that remains unknown about decreasing household firearm injury and death.”

And the degree to which findings from these two gun-safety programs can be generalized to other academic centers or children’s hospitals is unclear.

“There are states where, I suspect, firearm screening is much more common. Some states have very pro-firearm cultures and others are anti-firearm,” Dr. Greeley said. “There are also likely differences within states,” particularly between urban and rural regions.

“Firearms are often a very personal issue for families, and pediatricians in ‘pro-firearm’ communities may have greater resistance to working on this,” he pointed out.

Nevertheless, Dr. Greeley said, “this is a promising strategy that could be part of a broad injury prevention initiative.”

Neither study noted any external funding. Dr. Byrne is a member of the Moms Demand Action Gainesville Chapter, which donated the firearm locks for the project. Dr. Breuner, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Farrington have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When pediatricians and other pediatric providers are given training and resource materials, levels of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance about firearm safety increase significantly, according to two new studies presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“With the rise in firearm sales and injuries during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is more important than ever that pediatricians address the firearm epidemic,” said Alexandra Byrne, MD, a pediatric resident at the University of Florida in Gainesville, who presented one of the studies.

There were 4.3 million more firearms purchased from March through July 2020 than expected, a recent study estimates, and 4,075 more firearm injuries than expected from April through July 2020.

In states with more excess purchases, firearm injuries related to domestic violence increased in April (rate ratio, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.32-5.93) and May (RR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.19-2.91) 2020. However, excess gun purchases had no effect on rates of firearm violence outside the home.

In addition to the link between firearms in the home and domestic violence, they are also linked to a three- to fourfold greater risk for teen suicide, and both depression and suicidal thoughts have risen in teens during the pandemic.

“The data are pretty clear that if you have an unlocked, loaded weapon in your home, and you have a kid who’s depressed or anxious or dysregulated or doing maladaptive things for the pandemic, they’re much more likely to inadvertently take their own or someone else’s life by grabbing [a gun],” said Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

However, there is no difference in gun ownership or gun-safety measures between homes with and without at-risk children, previous research shows.

Training, guidance, and locks

Previous research has also shown that there has been a reluctance by pediatricians to conduct firearm screenings and counsel parents about gun safety in the home.

For their two-step program, Dr. Byrne’s team used a plan-do-study-act approach. They started by providing training on firearm safety, evidence-based recommendations for firearm screening, and anticipatory guidance regarding safe firearm storage to members of the general pediatrics division at the University of Florida. And they supplied clinics with free firearm locks.

Next they supplied clinics with posters and educational cards from the Be SMART campaign, an initiative of the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, which provides materials for anyone, including physicians, to use.

During their study, the researchers sent three anonymous six-question online surveys – at baseline and 3 to 4 months after each of the two steps – to pediatric residents, physician assistants, advanced practice registered nurses, and attendings to assess the project. There were 52 responses to the first survey, for a response rate of 58.4%, 42 responses to the second survey, for a response rate of 47.2%, and 23 responses to the third survey, for a rate of response 25.8%.

The program nearly doubled screenings during well-child visits and dramatically increased the proportion of families who received a firearm lock when they told providers they had a firearm at home.

Previous research has shown “a significant increase in safe firearm storage when firearm locks were provided to families in clinic compared to verbal counseling alone,” Dr. Byrne said. “We know that safe firearm storage reduces injuries. Roughly one in three children in the United States lives in a home with a firearm. Individuals with a firearm are at two times the risk of homicide and three to four times the risk of suicide, so it is essential we further study how pediatricians can be most effective when it comes to firearm counseling.”

The difference in lock distribution as a result of the program is a “tremendous increase,” said Christopher S. Greeley, MD, MS, chief of the division of public health pediatrics at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the research.

“Locks could go a long way to minimizing the risk,” he said in an interview, adding that nearly half of all teen suicide deaths that occurred over a decade in Houston involved a firearm.

Adding a social-history component

A program to increase firearm screening was also presented at the AAP conference.

After random review of medical records from 30 patients admitted to the hospital documented zero firearm screenings, Marjorie Farrington, MD, and Samantha Gunkelman, MD, from Akron Children’s Hospital in Ohio, implemented a program that they hope will increase firearm screenings during inpatient admissions to at least 50%.

They started their ongoing program in April 2020 by adding a social-history component to the history and physical (H&P) exam template and educating residents on how to screen and included guidance on safe firearm storage.

They also had physicians with firearm expertise give gun-safety lectures, and they plan to involve the Family Resource Center at their hospital in the creation of resources that can be incorporated into discharge instructions.

From April 2020 to June 2021, after the addition to the H&P template, 63% of the 5196 patients admitted to the hospital underwent a firearm screening. Of the 25% of patients who reported guns at home, 3% were not storing their firearms safely.

The pair used the “Store It Safe” Physician Handout provided by the Ohio chapter of the AAP.

Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic.

The BulletPoints Project — developed by the Violence Prevention Research Program at the University of California, Davis — can also help physicians talk to patients about guns.

“Many pediatricians and pediatric trainees are not comfortable counseling on firearm safety, often a result of inadequate training on the topic,” Dr. Byrne said in an interview. “Additionally, it is a challenging topic that can often be met with resistance from patients and families. Lack of time during visits is also a huge barrier.”

Lack of training is an obstacle to greater firearm screenings, Dr. Greeley agreed, as are the feeling that guidance simply won’t make a difference and concerns about political pressure and divineness. The lack of research on firearm injuries and the impact of firearm screenings and anticipatory guidance is a challenge, he added, although that is starting to change.

Pediatricians need education on how to make a difference when it comes to firearm safety, and should follow AAP guidelines, Dr. Greeley said.

Counseling on firearm safety is in the same category as immunizations, seatbelts, substance use, helmets, and other public-health issues that are important to address at visits, regardless of how difficult it might be, Dr. Breuner told this news organization.

“It is our mission, as pediatricians, to provide every ounce of prevention in our well-child and anticipatory guidance visits,” she said. “It’s our job, so we shouldn’t shy away from it even though it’s hard.”

Doctors are more comfortable discussing firearm safety if they are firearm owners, previous research has shown, so she advises pediatricians who feel unqualified to discuss firearms to seek guidance from their peers on how to approach screenings and anticipatory guidance, she noted.

The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause. The populations are often very different than private practice.

Both of these studies were conducted at single institutions and might not reflect what would work in private clinics.

“The firearm study being done in an academic center gives me great pause,” Dr. Greeley said. “The populations are often very different than private practice. I think that there is still a lot that remains unknown about decreasing household firearm injury and death.”

And the degree to which findings from these two gun-safety programs can be generalized to other academic centers or children’s hospitals is unclear.

“There are states where, I suspect, firearm screening is much more common. Some states have very pro-firearm cultures and others are anti-firearm,” Dr. Greeley said. “There are also likely differences within states,” particularly between urban and rural regions.

“Firearms are often a very personal issue for families, and pediatricians in ‘pro-firearm’ communities may have greater resistance to working on this,” he pointed out.

Nevertheless, Dr. Greeley said, “this is a promising strategy that could be part of a broad injury prevention initiative.”

Neither study noted any external funding. Dr. Byrne is a member of the Moms Demand Action Gainesville Chapter, which donated the firearm locks for the project. Dr. Breuner, Dr. Greeley, and Dr. Farrington have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAP 2021

Homicide remains a top cause of maternal mortality

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

You’ve been uneasy about the mother’s boyfriend: This may be why

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

The first patient of the afternoon is a 4-month-old in for his health maintenance visit. You’ve known his 20-year-old mother since she was a toddler. This infant has a 2-year-old sister. Also in the exam room is a young man you don’t recognize whom the mother introduces as Jason, her new boyfriend. He never makes eye contact and despite your best efforts you can’t get him to engage.

At the child’s next visit you are relieved to see the 6-month-old is alive and well and learn that your former patient and her two children have moved back in with her parents and Jason is no longer in the picture.

You don’t have to have been doing pediatrics very long to have learned that a “family” that includes an infant and a young adult male who is probably not the father is an environment in which the infant’s health and well-being is at significant risk. It is a situation in which child abuse even to the point of infanticide should be waving a red flag in your face.

Infanticide occurs in many animal species including our own. As abhorrent we may find the act, it occurs often enough to be, if not normal, at least not unexpected in certain circumstances. Theories abound as to what advantage the act of infanticide might convey to the success of a species. However, little if anything is known about any possible mechanisms that would allow it to occur.

Recently, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University discovered a specific set of neurons in the mouse brain that controls aggressive behavior toward infants (Biological triggers for infant abuse, by Juan Siliezar, The Harvard Gazette, Sept 27, 2021). This same set of neurons also appears to trigger avoidance and neglect behaviors as well.

Research in other animal species has found that these antiparental behaviors occur in both virgins and sexually mature males who are strangers to the group. Interestingly, the behaviors switch off once individuals have their own offspring or have had the opportunity to familiarize themselves with infants. Not surprisingly, other studies have found that in some species environmental stress such as food shortage or threats of predation have triggered females to attack or ignore their offspring.

I think it is safe to assume a similar collection of neurons controlling aggressive behavior also exists in humans. One can imagine some well-read defense attorney dredging up this study and claiming that because his client had not yet fathered a child of his own that it was his nervous system’s normal response that made him toss his girlfriend’s baby against the wall.

The lead author of the study intends to study this collection of neurons in more depth to discover more about the process. It is conceivable that with more information her initial findings may help in the development of treatment and specific prevention strategies. Until that happens, we must rely on our intuition and keep our antennae tuned and alert for high-risk scenarios like the one I described at the opening of this letter.

We are left with leaning heavily on our community social work networks to keep close tabs on these high-risk families, offering both financial and emotional support. Parenting classes may be helpful, but some of this research leads me to suspect that immersing these young parents-to-be in hands-on child care situations might provide the best protection we can offer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Synthetic chemical in consumer products linked to early death, study says

Daily exposure to phthalates, which are synthetic chemicals founds in many consumer products, may lead to hundreds of thousands of early deaths each year among older adults in the United States, according to a new study published Oct. 12, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution.

The chemicals are found in hundreds of types of products, including children’s toys, food storage containers, makeup, perfume, and shampoo. In the study, those with the highest levels of phthalates had a greater risk of death from any cause, especially heart disease.

“This study adds to the growing database on the impact of plastics on the human body and bolsters public health and business cases for reducing or eliminating the use of plastics,” Leonardo Trasande, MD, the lead author and a professor of environmental medicine and population health at New York University Langone Health, told CNN.

Dr. Trasande and colleagues measured the urine concentration of phthalates in more than 5,000 adults aged 55-64 and compared the levels with the risk of early death over an average of 10 years. The research team controlled for preexisting heart diseases, diabetes, cancer, poor eating habits, physical activity, body mass, and other known hormone disruptors such as bisphenol A, or BPA, an industrial chemical that’s been used since the 1950s to make certain plastics and resins, according to the Mayo Clinic

The research team found that phthalates could contribute to 91,000-107,000 premature deaths per year in the United States. These early deaths could cost the nation $40 billion to $47 billion each year in lost economic productivity.

Phthalates interrupt the body’s endocrine system and hormone production. Previous studies have found that the chemicals are linked with developmental, reproductive, and immune system problems, according to NYU Langone Health. They’ve also been linked with asthma, childhood obesity, heart issues, and cancer.

“These chemicals have a rap sheet,” Dr. Trasande told CNN. “And the fact of the matter is that when you look at the entire body of evidence, it provides a haunting pattern of concern.”

Phthalates are often called “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common, CNN reported. Also called “plasticizers,” they are added to products to make them more durable, including PVC plumbing, vinyl flooring, medical tubing, garden hoses, food packaging, detergents, clothing, furniture, and automotive materials.

People are often exposed when they breathe contaminated air or consume food that comes into contact with the chemical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children may be exposed by touching plastic items and putting their hands in their mouth.

Dr. Trasande told CNN that it’s possible to lessen exposure to phthalates and other endocrine disruptors such as BPA by using unscented lotions, laundry detergents, and cleaning supplies, as well as substituting glass, stainless steel, ceramic, and wood for plastic food storage.

“First, avoid plastics as much as you can. Never put plastic containers in the microwave or dishwasher, where the heat can break down the linings so they might be absorbed more readily,” he said. “In addition, cooking at home and reducing your use of processed foods can reduce the levels of the chemical exposures you come in contact with.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Daily exposure to phthalates, which are synthetic chemicals founds in many consumer products, may lead to hundreds of thousands of early deaths each year among older adults in the United States, according to a new study published Oct. 12, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution.

The chemicals are found in hundreds of types of products, including children’s toys, food storage containers, makeup, perfume, and shampoo. In the study, those with the highest levels of phthalates had a greater risk of death from any cause, especially heart disease.

“This study adds to the growing database on the impact of plastics on the human body and bolsters public health and business cases for reducing or eliminating the use of plastics,” Leonardo Trasande, MD, the lead author and a professor of environmental medicine and population health at New York University Langone Health, told CNN.

Dr. Trasande and colleagues measured the urine concentration of phthalates in more than 5,000 adults aged 55-64 and compared the levels with the risk of early death over an average of 10 years. The research team controlled for preexisting heart diseases, diabetes, cancer, poor eating habits, physical activity, body mass, and other known hormone disruptors such as bisphenol A, or BPA, an industrial chemical that’s been used since the 1950s to make certain plastics and resins, according to the Mayo Clinic

The research team found that phthalates could contribute to 91,000-107,000 premature deaths per year in the United States. These early deaths could cost the nation $40 billion to $47 billion each year in lost economic productivity.

Phthalates interrupt the body’s endocrine system and hormone production. Previous studies have found that the chemicals are linked with developmental, reproductive, and immune system problems, according to NYU Langone Health. They’ve also been linked with asthma, childhood obesity, heart issues, and cancer.

“These chemicals have a rap sheet,” Dr. Trasande told CNN. “And the fact of the matter is that when you look at the entire body of evidence, it provides a haunting pattern of concern.”

Phthalates are often called “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common, CNN reported. Also called “plasticizers,” they are added to products to make them more durable, including PVC plumbing, vinyl flooring, medical tubing, garden hoses, food packaging, detergents, clothing, furniture, and automotive materials.

People are often exposed when they breathe contaminated air or consume food that comes into contact with the chemical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children may be exposed by touching plastic items and putting their hands in their mouth.

Dr. Trasande told CNN that it’s possible to lessen exposure to phthalates and other endocrine disruptors such as BPA by using unscented lotions, laundry detergents, and cleaning supplies, as well as substituting glass, stainless steel, ceramic, and wood for plastic food storage.

“First, avoid plastics as much as you can. Never put plastic containers in the microwave or dishwasher, where the heat can break down the linings so they might be absorbed more readily,” he said. “In addition, cooking at home and reducing your use of processed foods can reduce the levels of the chemical exposures you come in contact with.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Daily exposure to phthalates, which are synthetic chemicals founds in many consumer products, may lead to hundreds of thousands of early deaths each year among older adults in the United States, according to a new study published Oct. 12, 2021, in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Pollution.

The chemicals are found in hundreds of types of products, including children’s toys, food storage containers, makeup, perfume, and shampoo. In the study, those with the highest levels of phthalates had a greater risk of death from any cause, especially heart disease.

“This study adds to the growing database on the impact of plastics on the human body and bolsters public health and business cases for reducing or eliminating the use of plastics,” Leonardo Trasande, MD, the lead author and a professor of environmental medicine and population health at New York University Langone Health, told CNN.

Dr. Trasande and colleagues measured the urine concentration of phthalates in more than 5,000 adults aged 55-64 and compared the levels with the risk of early death over an average of 10 years. The research team controlled for preexisting heart diseases, diabetes, cancer, poor eating habits, physical activity, body mass, and other known hormone disruptors such as bisphenol A, or BPA, an industrial chemical that’s been used since the 1950s to make certain plastics and resins, according to the Mayo Clinic

The research team found that phthalates could contribute to 91,000-107,000 premature deaths per year in the United States. These early deaths could cost the nation $40 billion to $47 billion each year in lost economic productivity.

Phthalates interrupt the body’s endocrine system and hormone production. Previous studies have found that the chemicals are linked with developmental, reproductive, and immune system problems, according to NYU Langone Health. They’ve also been linked with asthma, childhood obesity, heart issues, and cancer.

“These chemicals have a rap sheet,” Dr. Trasande told CNN. “And the fact of the matter is that when you look at the entire body of evidence, it provides a haunting pattern of concern.”

Phthalates are often called “everywhere chemicals” because they are so common, CNN reported. Also called “plasticizers,” they are added to products to make them more durable, including PVC plumbing, vinyl flooring, medical tubing, garden hoses, food packaging, detergents, clothing, furniture, and automotive materials.

People are often exposed when they breathe contaminated air or consume food that comes into contact with the chemical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Children may be exposed by touching plastic items and putting their hands in their mouth.

Dr. Trasande told CNN that it’s possible to lessen exposure to phthalates and other endocrine disruptors such as BPA by using unscented lotions, laundry detergents, and cleaning supplies, as well as substituting glass, stainless steel, ceramic, and wood for plastic food storage.

“First, avoid plastics as much as you can. Never put plastic containers in the microwave or dishwasher, where the heat can break down the linings so they might be absorbed more readily,” he said. “In addition, cooking at home and reducing your use of processed foods can reduce the levels of the chemical exposures you come in contact with.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID-19: U.S. adds latest million cases in record time

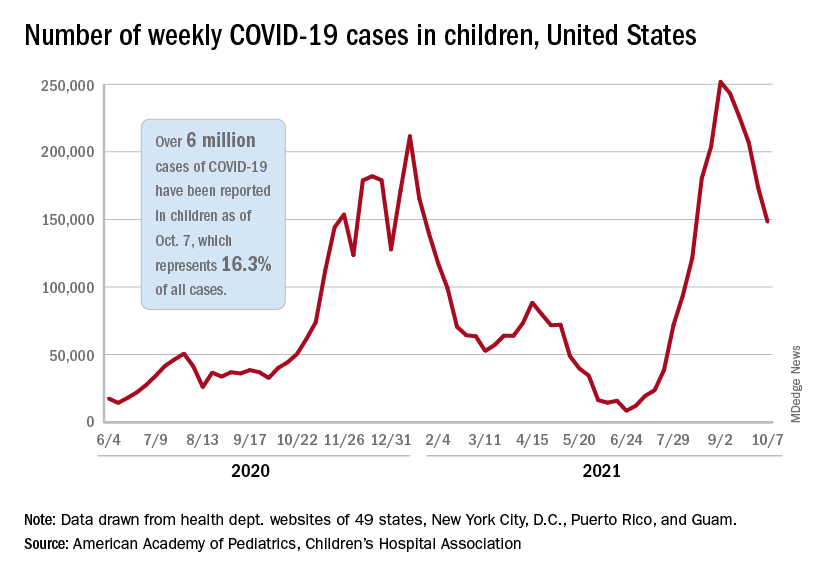

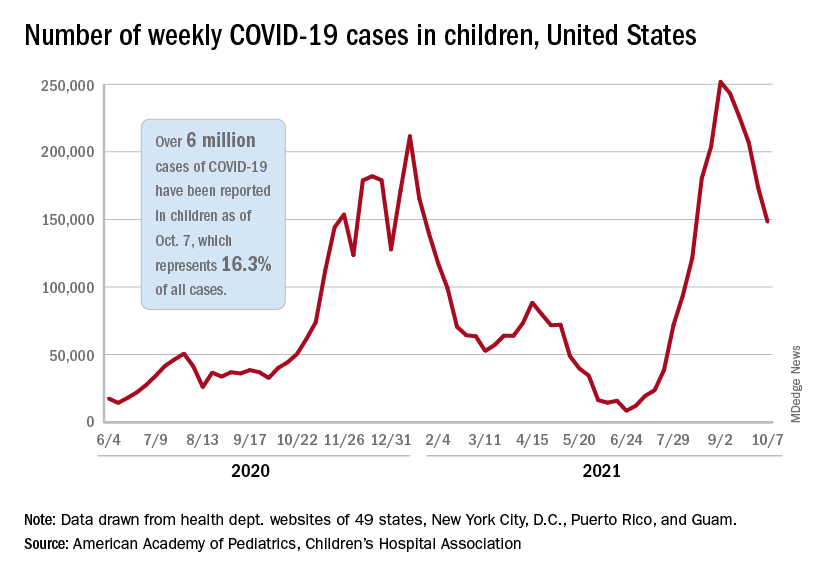

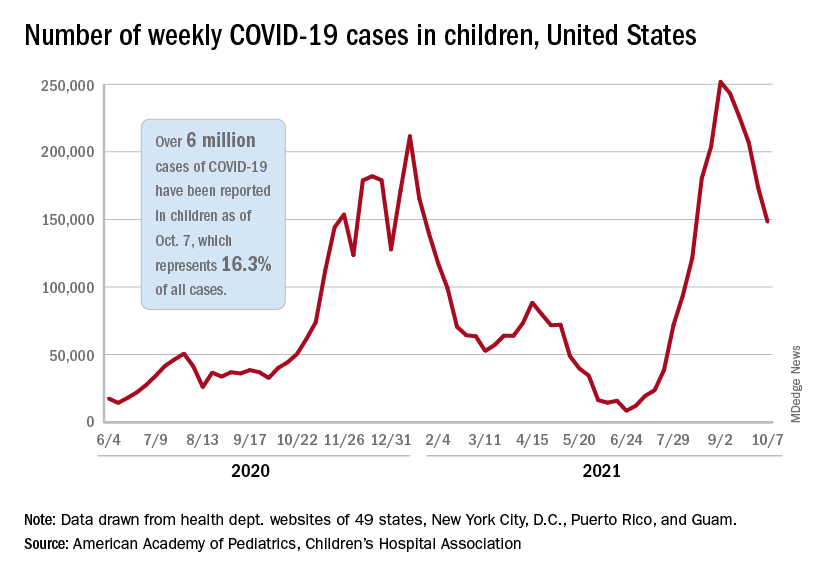

The United States just passed the 6-million mark in COVID-19 cases among children, with the last million cases taking less time to record than any of the first five, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The five-millionth case was reported during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2, and case number 6 million came during the week of Oct. 1-7, just 5 weeks later, compared with the 6 weeks it took to go from 1 million to 2 million last November and December, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

New cases continued to drop, however, and that weekly count was down by 14.6% from the previous week and by 41.1% from the peak of almost 252,000 reached in early September, the two groups said while also noting limitations to the data, such as three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) that are no longer updating their COVID-19 dashboards.

Other metrics show similar drops in recent weeks. Among children aged 0-11 years, emergency department visits involving a COVID-19 diagnosis dropped from 4.1% of all ED visits in late August to 1.4% of ED visits on Oct. 6. ED visits with a COVID-19 diagnosis fell from a peak of 8.5% on Aug. 22 to 1.5% on Oct. 6 for 12- to 15-year-olds and from 8.5% to 1.5% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was down to 0.26 per 100,000 population on Oct. 9 after reaching 0.51 per 100,000 on Sept. 4. Hospitalizations in children totaled just over 64,000 from Aug. 1, 2020, to Oct. 9, 2021, which is just over 2% of all COVID-19–related admissions over that time period, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

That pattern, unfortunately, also applies to vaccinations. “The number of children receiving their first COVID-19 vaccine this week [Sept. 30 to Oct. 6], about 156,000, was the lowest number since vaccines were available,” the AAP said in a separate report on vaccination trends, adding that “the number of children receiving their first dose has steadily declined from 8 weeks ago when 586,000 children received their initial dose the week ending Aug. 11.”

The United States just passed the 6-million mark in COVID-19 cases among children, with the last million cases taking less time to record than any of the first five, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The five-millionth case was reported during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2, and case number 6 million came during the week of Oct. 1-7, just 5 weeks later, compared with the 6 weeks it took to go from 1 million to 2 million last November and December, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

New cases continued to drop, however, and that weekly count was down by 14.6% from the previous week and by 41.1% from the peak of almost 252,000 reached in early September, the two groups said while also noting limitations to the data, such as three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) that are no longer updating their COVID-19 dashboards.

Other metrics show similar drops in recent weeks. Among children aged 0-11 years, emergency department visits involving a COVID-19 diagnosis dropped from 4.1% of all ED visits in late August to 1.4% of ED visits on Oct. 6. ED visits with a COVID-19 diagnosis fell from a peak of 8.5% on Aug. 22 to 1.5% on Oct. 6 for 12- to 15-year-olds and from 8.5% to 1.5% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was down to 0.26 per 100,000 population on Oct. 9 after reaching 0.51 per 100,000 on Sept. 4. Hospitalizations in children totaled just over 64,000 from Aug. 1, 2020, to Oct. 9, 2021, which is just over 2% of all COVID-19–related admissions over that time period, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

That pattern, unfortunately, also applies to vaccinations. “The number of children receiving their first COVID-19 vaccine this week [Sept. 30 to Oct. 6], about 156,000, was the lowest number since vaccines were available,” the AAP said in a separate report on vaccination trends, adding that “the number of children receiving their first dose has steadily declined from 8 weeks ago when 586,000 children received their initial dose the week ending Aug. 11.”

The United States just passed the 6-million mark in COVID-19 cases among children, with the last million cases taking less time to record than any of the first five, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The five-millionth case was reported during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2, and case number 6 million came during the week of Oct. 1-7, just 5 weeks later, compared with the 6 weeks it took to go from 1 million to 2 million last November and December, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

New cases continued to drop, however, and that weekly count was down by 14.6% from the previous week and by 41.1% from the peak of almost 252,000 reached in early September, the two groups said while also noting limitations to the data, such as three states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas) that are no longer updating their COVID-19 dashboards.

Other metrics show similar drops in recent weeks. Among children aged 0-11 years, emergency department visits involving a COVID-19 diagnosis dropped from 4.1% of all ED visits in late August to 1.4% of ED visits on Oct. 6. ED visits with a COVID-19 diagnosis fell from a peak of 8.5% on Aug. 22 to 1.5% on Oct. 6 for 12- to 15-year-olds and from 8.5% to 1.5% in those aged 16-17 years, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of new hospital admissions for children aged 0-17 years was down to 0.26 per 100,000 population on Oct. 9 after reaching 0.51 per 100,000 on Sept. 4. Hospitalizations in children totaled just over 64,000 from Aug. 1, 2020, to Oct. 9, 2021, which is just over 2% of all COVID-19–related admissions over that time period, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

That pattern, unfortunately, also applies to vaccinations. “The number of children receiving their first COVID-19 vaccine this week [Sept. 30 to Oct. 6], about 156,000, was the lowest number since vaccines were available,” the AAP said in a separate report on vaccination trends, adding that “the number of children receiving their first dose has steadily declined from 8 weeks ago when 586,000 children received their initial dose the week ending Aug. 11.”

Underrepresented Minority Students Applying to Dermatology Residency in the COVID-19 Era: Challenges and Considerations

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8