User login

Is genetic testing valuable in the clinical management of epilepsy?

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

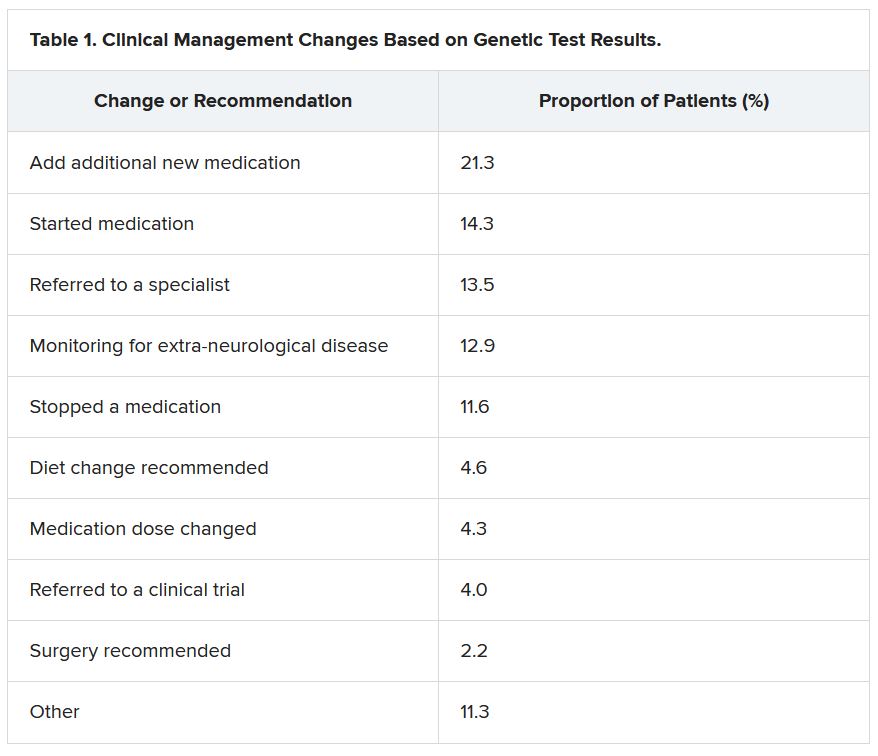

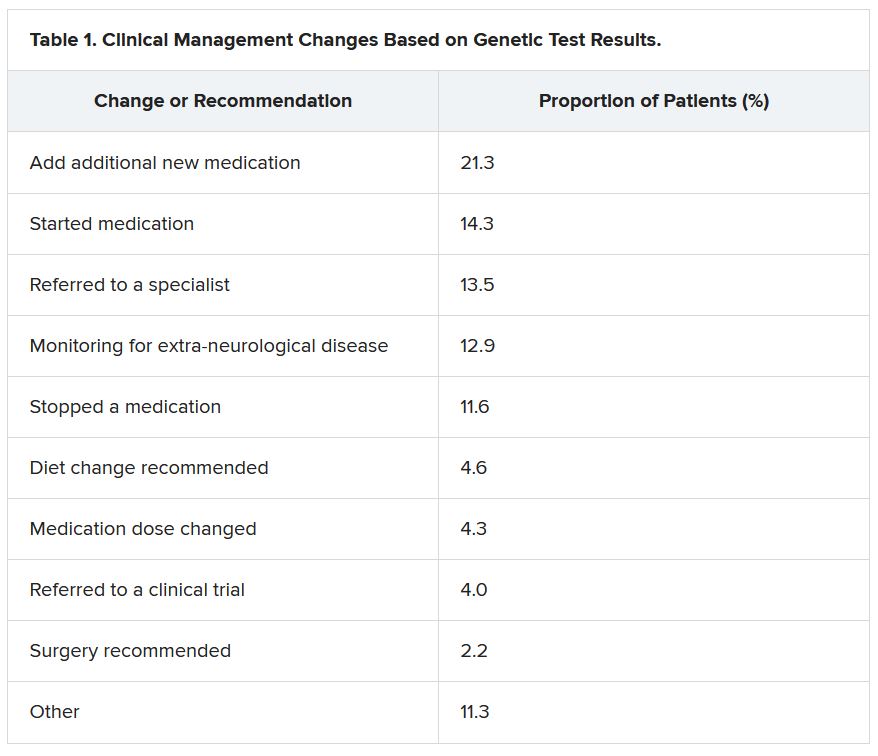

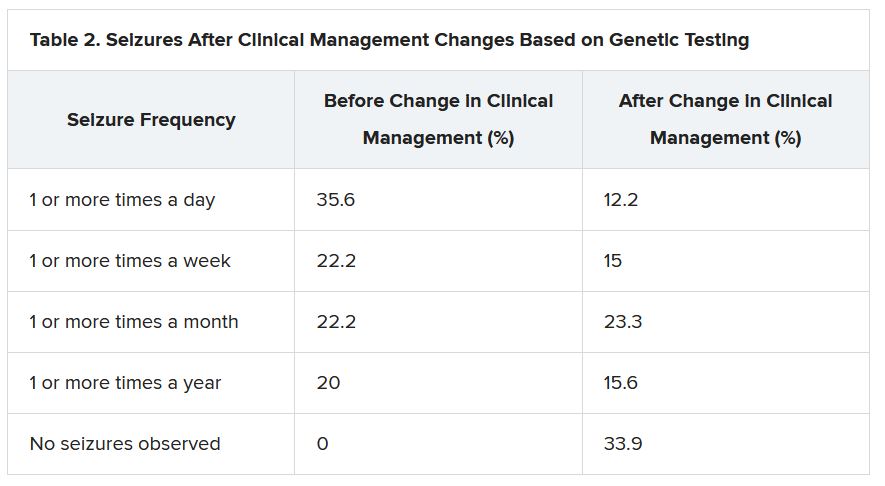

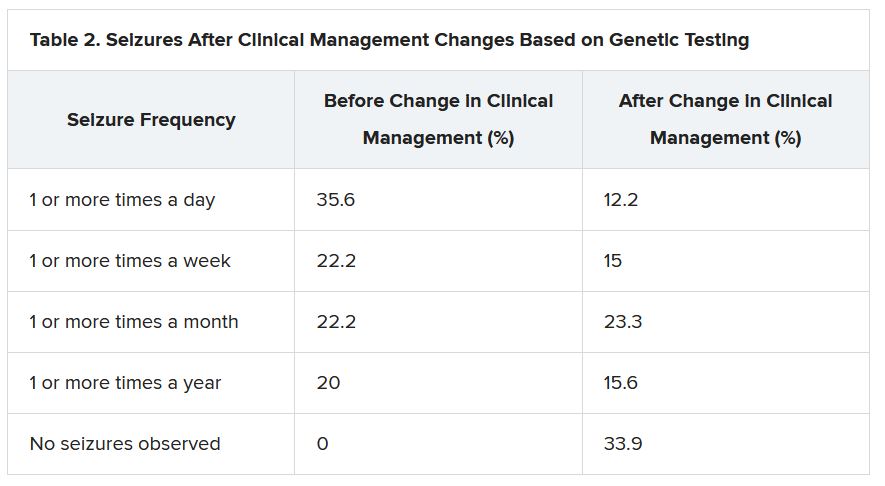

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

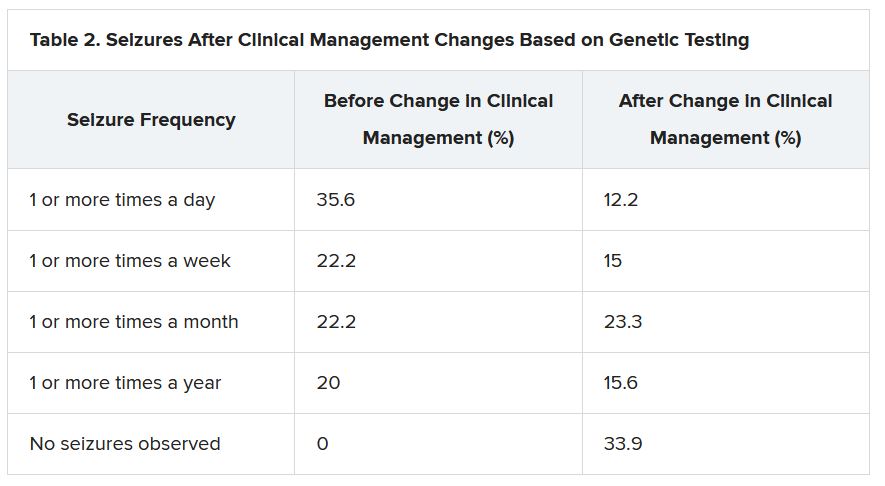

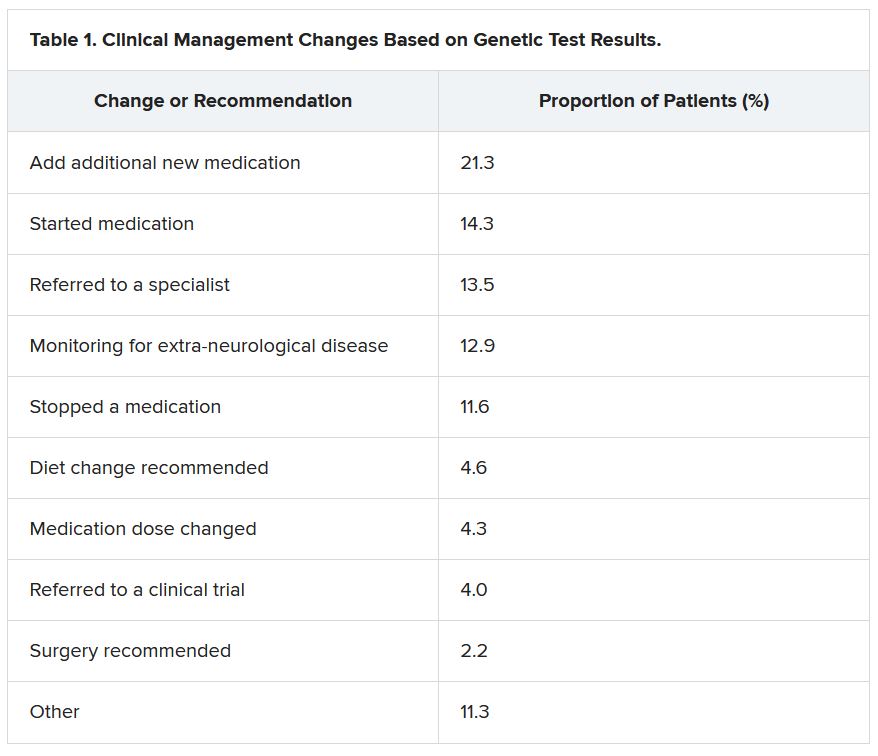

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

Results of a survey that included more than 400 patients showed that positive findings from genetic testing helped guide clinical management in 50% of cases and improved patient outcomes in 75%. In addition, the findings were applicable to both children and adults.

“Fifty percent of the time the physicians reported that, yes, receiving the genetic diagnosis did change how they managed the patients,” reported co-investigator Dianalee McKnight, PhD, director of medical affairs at Invitae, a medical genetic testing company headquartered in San Francisco. In 81.3% of cases, providers reported they changed clinical management within 3 months of receiving the genetic results, she added.

The findings were presented at the 2021 World Congress of Neurology (WCN).

Test results can be practice-changing

Nearly 50% of positive genetic test results in epilepsy patients can help guide clinical management, Dr. McKnight noted. However, information on how physicians use genetic information in decision-making has been limited, prompting her conduct the survey.

A total of 1,567 physicians with 3,572 patients who had a definitive diagnosis of epilepsy were contacted. A total of 170 (10.8%) clinicians provided completed and eligible surveys on 429 patients with epilepsy.

The patient cohort comprised mostly children, with nearly 50 adults, which Dr. McKnight said is typical of the population receiving genetic testing in clinical practice.

She reported that genetic testing results prompted clinicians to make medication changes about 50% of the time. Other changes included specialist referral or to a clinical trial, monitoring for other neurological disease, and recommendations for dietary change or for surgery.

“Of the physicians who changed treatment, 75% reported there were positive outcomes for the patients,” Dr. McKnight told meeting attendees. “Most common was a reduction or a complete elimination of seizures, and that was reported in 65% of the cases.”

In many cases, the changes resulted in clinical improvements.

“There were 64 individuals who were having daily seizures before the genetic testing,” Dr. McKnight reported via email. “After receiving the genetic diagnosis and modifying their treatment, their physicians reported that 26% of individuals had complete seizure control and 46% of individuals had reduced seizure frequency to either weekly (20%), monthly (20%) or annually (6%).”

The best seizure control after modifying disease management occurred among children. Although the changes were not as dramatic for adults, they trended toward lower seizure frequency.

“It is still pretty significant that adults can receive genetic testing later in life and still have benefit in controlling their seizures,” Dr. McKnight said.

Twenty-three percent of patients showed improvement in behavior, development, academics, or movement issues, while 6% experienced reduced medication side effects.

Dr. McKnight also explored reasons for physicians not making changes to clinical management of patients based on the genetic results. The most common reason was that management was already consistent with the results (47.3%), followed by the results not being informative (26.1%), the results possibly being useful for future treatments in development (19.0%), or other or unknown reasons (7.6%).

Besides direct health and quality of life benefits from better seizure control, Dr. McKnight cited previous economic studies showing lower health care costs.

“It looked like an individual who has good seizure control will incur about 14,000 U.S. dollars a year compared with an individual with pretty poor seizure control, where it can be closer to 23,000 U.S. dollars a year,” Dr. McKnight said. This is mainly attributed to reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Dr. McKnight noted that currently there is no cost of genetic testing to the patient, the hospital, or insurers. Pharmaceutical companies, she said, sponsor the testing to potentially gather patients for clinical drug trials in development. However, patients remain completely anonymous.

Physicians who wish to have patient samples tested agree that the companies may contact them to ask if any of their patients with positive genetic test results would like to participate in a trial.

Dr. McKnight noted that genetic testing can be considered actionable in the clinic, helping to guide clinical decision-making and potentially leading to better outcomes. Going forward, she suggested performing large case-controlled studies “of individuals with the same genetic etiology ... to really find a true causation or correlation.”

Growing influence of genetic testing

Commenting on the findings, Jaysingh Singh, MD, co-director of the Epilepsy Surgery Center at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, noted that the study highlights the value of gene testing in improving outcomes in patients with epilepsy, particularly the pediatric population.

He said the findings make him optimistic about the potential of genetic testing in adult patients – with at least one caveat.

“The limitation is that if we do find some mutation, we don’t know what to do with that. That’s definitely one challenge. And we see that more often in the adult patient population,” said Dr. Singh, who was not involved with the research.

He noted that there is a small group of genetic mutations when, found in adults, may dramatically alter treatment.

For example, he noted that if there is a gene mutation related to mTOR pathways, that could provide a future target because there are already medications that target this pathway.

Genetic testing may also be useful in cases where patients have normal brain imaging and poor response to standard treatment or in cases where patients have congenital abnormalities such as intellectual impairment or facial dysmorphic features and a co-morbid seizure disorder, he said.

Dr. Singh noted that he has often found genetic testing impractical because “if I order DNA testing right now, it will take 4 months for me to get the results. I cannot wait 4 months for the results to come back” to adjust treatment.

Dr. McKnight is an employee of and a shareholder in Invitae, which funded the study. Dr. Singh has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From WCN 2021

USPSTF rules out aspirin for over 60s in primary CVD prevention

New draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been released and appear to limit the population in which it should be considered.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk has a small net benefit,” the recommendation notes. They conclude that for these patients, the decision to use aspirin “should be an individual one.”

“Persons who are not at increased risk for bleeding and are willing to take low-dose aspirin daily are more likely to benefit,” they note.

For older individuals, however, the task force concludes.

The new recommendations were posted online Oct. 12 and will be available for public comment until November 8. Once it is finalized, the recommendation will replace the 2016 USPSTF recommendation on aspirin use to prevent CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC), they note.

In that document, the task force recommended initiating low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of both CVD and CRC in adults 50-59 years of age who had a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, were not at increased risk for bleeding, had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, and were willing to take daily low-dose aspirin for at least 10 years, with the decision to start being an individual one.

For older and younger patients, they found at that time that the evidence was “insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD and CRC in adults younger than age 50 years or adults aged 70 years or older.”

In the new draft document, “the USPSTF has changed the age ranges and grades of its recommendation on aspirin use.” Besides the recommendations for CVD prevention, they have also changed the previous recommendation of aspirin for the prevention of CRC given evidence generated from large primary CVD prevention trials.

“Based on new analyses of the evidence from primary CVD prevention populations, longer-term follow-up data from the Women’s Health Study (WHS) (JE Buring, personal communication, November 23, 2020), and new trial evidence, the USPSTF concluded that the evidence is inadequate that low-dose aspirin use reduces CRC incidence or mortality,” it states.

Optimum dose

On the optimum dose for primary CVD prevention, the task force says the benefit appears similar for a low dose (≤100 mg/d) and all doses that have been studied in CVD prevention trials (50 to 500 mg/d). “A pragmatic approach would be to use 81 mg/d, which is the most commonly prescribed dose in the United States,” it states.

The USPSTF recommends using the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate cardiovascular risk but it points out that these equations are imperfect for risk prediction at the individual level, and suggests using these risk estimates as a starting point to discuss with appropriate candidates their desire for daily aspirin use. The benefits of initiating aspirin use are greater for individuals at higher risk for CVD events (eg, those with >15% or >20% 10-year CVD risk), they note.

“Decisions about initiating aspirin use should be based on shared decision-making between clinicians and patients about the potential benefits and harms. Persons who place a higher value on the potential benefits than the potential harms may choose to initiate low-dose aspirin use. Persons who place a higher value on the potential harms or on the burden of taking a daily preventive medication than the potential benefits may choose not to initiate low-dose aspirin use,” the task force says.

It also points out that the risk for bleeding increases modestly with advancing age. “For persons who have initiated aspirin use, the net benefits continue to accrue over time in the absence of a bleeding event. The net benefits, however, become smaller with advancing age because of an increased risk for bleeding, so modeling data suggest that it may be reasonable to consider stopping aspirin use around age 75 years,” it states.

Systematic review

The updated draft recommendations are based on a new systematic review commissioned by the USPSTF on the effectiveness of aspirin to reduce the risk of CVD events (myocardial infarction and stroke), cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in persons without a history of CVD.

The systematic review also investigated the effect of aspirin use on CRC incidence and mortality in primary CVD prevention populations, as well as the harms, particularly bleeding harms, associated with aspirin use.

In addition to the systematic evidence review, the USPSTF commissioned a microsimulation modeling study to assess the net balance of benefits and harms from aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD and CRC, stratified by age, sex, and CVD risk level. Modeling study parameter inputs were informed by the results of the systematic review, and the primary outcomes were net benefits expressed as quality-adjusted life-years and life-years.

The USPSTF found 13 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that reported on the benefits of aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The total number of participants was 161,680, and most trials used low-dose aspirin of 100 mg/d or less or aspirin every other day. The 13 primary prevention trials included a balanced number of male and female participants and included a broad distribution of ages, with mean age ranging from 53 years in the Physicians’ Health Study to 74 years in the ASPREE trial.

This body of evidence shows that aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD is associated with a decreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke but not cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality. Results are quite similar when including studies using all doses of aspirin compared with studies using low-dose aspirin.

The USPSTF reviewed 14 RCTs in CVD primary prevention populations that reported on the bleeding harms of aspirin.

When looking at studies reporting on the harms of low-dose aspirin use (≤100 mg/d), which is most relevant to current practice, a pooled analysis of 10 trials showed that aspirin use was associated with a 58% increase in major gastrointestinal bleeding, and a pooled analysis of 11 trials showed a 31% increase in intracranial bleeds in the aspirin group compared with the control group. Low-dose aspirin use was not associated with a statistically significant increase in risk of fatal hemorrhagic stroke.

Data suggested that the increased risk of bleeding associated with aspirin use occurs relatively quickly after initiating aspirin, and data do not suggest that aspirin has a differential relative bleeding risk based on age, sex, presence of diabetes, level of CVD risk, or race or ethnicity. Although the increase in relative risk does not appear to differ based on age, the absolute risk of bleeding, and thus the magnitude of bleeding harm, does increase with age, and more so in adults age 60 years or older, they note.

The microsimulation model to estimate the magnitude of net benefit of low-dose aspirin use incorporated findings from the systematic review.

Modeling data demonstrated that aspirin use in both men and women ages 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk generally provides a modest net benefit in both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years gained. Initiation of aspirin use in persons aged 60-69 years results in quality-adjusted life-years gained that range from slightly negative to slightly positive depending on CVD risk level, and life-years gained are generally negative.

In persons aged 70-79 years, initiation of aspirin use results in a loss of both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years at essentially all CVD risk levels modeled (ie, up to 20% 10-year CVD risk).

The USPSTF thus determined that aspirin use has a small net benefit in persons aged 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, and initiation of aspirin use has no net benefit in persons age 60 years or older.

When looking at net lifetime benefit of continuous aspirin use until stopping at age 65, 70, 75, 80, or 85 years, modeling data suggest that there is generally little incremental lifetime net benefit in continuing aspirin use beyond the age of 75-80 years.

The task force points out that the net benefit of continuing aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s is not the same as the net benefit of initiating aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s. This is because, in part, of the fact that CVD risk is heavily influenced by age. Persons who meet the eligibility criteria for aspirin use at a younger age (ie, ≥10% 10-year CVD risk in their 40s or 50s) typically have even higher CVD risk by their 60s or 70s compared with persons who first reach a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk in their 60s or 70s, and may gain more benefit by continuing aspirin use than a person at lower risk might gain by initiating aspirin use, the USPSTF explains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been released and appear to limit the population in which it should be considered.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk has a small net benefit,” the recommendation notes. They conclude that for these patients, the decision to use aspirin “should be an individual one.”

“Persons who are not at increased risk for bleeding and are willing to take low-dose aspirin daily are more likely to benefit,” they note.

For older individuals, however, the task force concludes.

The new recommendations were posted online Oct. 12 and will be available for public comment until November 8. Once it is finalized, the recommendation will replace the 2016 USPSTF recommendation on aspirin use to prevent CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC), they note.

In that document, the task force recommended initiating low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of both CVD and CRC in adults 50-59 years of age who had a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, were not at increased risk for bleeding, had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, and were willing to take daily low-dose aspirin for at least 10 years, with the decision to start being an individual one.

For older and younger patients, they found at that time that the evidence was “insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD and CRC in adults younger than age 50 years or adults aged 70 years or older.”

In the new draft document, “the USPSTF has changed the age ranges and grades of its recommendation on aspirin use.” Besides the recommendations for CVD prevention, they have also changed the previous recommendation of aspirin for the prevention of CRC given evidence generated from large primary CVD prevention trials.

“Based on new analyses of the evidence from primary CVD prevention populations, longer-term follow-up data from the Women’s Health Study (WHS) (JE Buring, personal communication, November 23, 2020), and new trial evidence, the USPSTF concluded that the evidence is inadequate that low-dose aspirin use reduces CRC incidence or mortality,” it states.

Optimum dose

On the optimum dose for primary CVD prevention, the task force says the benefit appears similar for a low dose (≤100 mg/d) and all doses that have been studied in CVD prevention trials (50 to 500 mg/d). “A pragmatic approach would be to use 81 mg/d, which is the most commonly prescribed dose in the United States,” it states.

The USPSTF recommends using the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate cardiovascular risk but it points out that these equations are imperfect for risk prediction at the individual level, and suggests using these risk estimates as a starting point to discuss with appropriate candidates their desire for daily aspirin use. The benefits of initiating aspirin use are greater for individuals at higher risk for CVD events (eg, those with >15% or >20% 10-year CVD risk), they note.

“Decisions about initiating aspirin use should be based on shared decision-making between clinicians and patients about the potential benefits and harms. Persons who place a higher value on the potential benefits than the potential harms may choose to initiate low-dose aspirin use. Persons who place a higher value on the potential harms or on the burden of taking a daily preventive medication than the potential benefits may choose not to initiate low-dose aspirin use,” the task force says.

It also points out that the risk for bleeding increases modestly with advancing age. “For persons who have initiated aspirin use, the net benefits continue to accrue over time in the absence of a bleeding event. The net benefits, however, become smaller with advancing age because of an increased risk for bleeding, so modeling data suggest that it may be reasonable to consider stopping aspirin use around age 75 years,” it states.

Systematic review

The updated draft recommendations are based on a new systematic review commissioned by the USPSTF on the effectiveness of aspirin to reduce the risk of CVD events (myocardial infarction and stroke), cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in persons without a history of CVD.

The systematic review also investigated the effect of aspirin use on CRC incidence and mortality in primary CVD prevention populations, as well as the harms, particularly bleeding harms, associated with aspirin use.

In addition to the systematic evidence review, the USPSTF commissioned a microsimulation modeling study to assess the net balance of benefits and harms from aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD and CRC, stratified by age, sex, and CVD risk level. Modeling study parameter inputs were informed by the results of the systematic review, and the primary outcomes were net benefits expressed as quality-adjusted life-years and life-years.

The USPSTF found 13 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that reported on the benefits of aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The total number of participants was 161,680, and most trials used low-dose aspirin of 100 mg/d or less or aspirin every other day. The 13 primary prevention trials included a balanced number of male and female participants and included a broad distribution of ages, with mean age ranging from 53 years in the Physicians’ Health Study to 74 years in the ASPREE trial.

This body of evidence shows that aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD is associated with a decreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke but not cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality. Results are quite similar when including studies using all doses of aspirin compared with studies using low-dose aspirin.

The USPSTF reviewed 14 RCTs in CVD primary prevention populations that reported on the bleeding harms of aspirin.

When looking at studies reporting on the harms of low-dose aspirin use (≤100 mg/d), which is most relevant to current practice, a pooled analysis of 10 trials showed that aspirin use was associated with a 58% increase in major gastrointestinal bleeding, and a pooled analysis of 11 trials showed a 31% increase in intracranial bleeds in the aspirin group compared with the control group. Low-dose aspirin use was not associated with a statistically significant increase in risk of fatal hemorrhagic stroke.

Data suggested that the increased risk of bleeding associated with aspirin use occurs relatively quickly after initiating aspirin, and data do not suggest that aspirin has a differential relative bleeding risk based on age, sex, presence of diabetes, level of CVD risk, or race or ethnicity. Although the increase in relative risk does not appear to differ based on age, the absolute risk of bleeding, and thus the magnitude of bleeding harm, does increase with age, and more so in adults age 60 years or older, they note.

The microsimulation model to estimate the magnitude of net benefit of low-dose aspirin use incorporated findings from the systematic review.

Modeling data demonstrated that aspirin use in both men and women ages 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk generally provides a modest net benefit in both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years gained. Initiation of aspirin use in persons aged 60-69 years results in quality-adjusted life-years gained that range from slightly negative to slightly positive depending on CVD risk level, and life-years gained are generally negative.

In persons aged 70-79 years, initiation of aspirin use results in a loss of both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years at essentially all CVD risk levels modeled (ie, up to 20% 10-year CVD risk).

The USPSTF thus determined that aspirin use has a small net benefit in persons aged 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, and initiation of aspirin use has no net benefit in persons age 60 years or older.

When looking at net lifetime benefit of continuous aspirin use until stopping at age 65, 70, 75, 80, or 85 years, modeling data suggest that there is generally little incremental lifetime net benefit in continuing aspirin use beyond the age of 75-80 years.

The task force points out that the net benefit of continuing aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s is not the same as the net benefit of initiating aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s. This is because, in part, of the fact that CVD risk is heavily influenced by age. Persons who meet the eligibility criteria for aspirin use at a younger age (ie, ≥10% 10-year CVD risk in their 40s or 50s) typically have even higher CVD risk by their 60s or 70s compared with persons who first reach a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk in their 60s or 70s, and may gain more benefit by continuing aspirin use than a person at lower risk might gain by initiating aspirin use, the USPSTF explains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New draft recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been released and appear to limit the population in which it should be considered.

“The USPSTF concludes with moderate certainty that aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD events in adults ages 40 to 59 years who have a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk has a small net benefit,” the recommendation notes. They conclude that for these patients, the decision to use aspirin “should be an individual one.”

“Persons who are not at increased risk for bleeding and are willing to take low-dose aspirin daily are more likely to benefit,” they note.

For older individuals, however, the task force concludes.

The new recommendations were posted online Oct. 12 and will be available for public comment until November 8. Once it is finalized, the recommendation will replace the 2016 USPSTF recommendation on aspirin use to prevent CVD and colorectal cancer (CRC), they note.

In that document, the task force recommended initiating low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of both CVD and CRC in adults 50-59 years of age who had a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, were not at increased risk for bleeding, had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, and were willing to take daily low-dose aspirin for at least 10 years, with the decision to start being an individual one.

For older and younger patients, they found at that time that the evidence was “insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of initiating aspirin use for the primary prevention of CVD and CRC in adults younger than age 50 years or adults aged 70 years or older.”

In the new draft document, “the USPSTF has changed the age ranges and grades of its recommendation on aspirin use.” Besides the recommendations for CVD prevention, they have also changed the previous recommendation of aspirin for the prevention of CRC given evidence generated from large primary CVD prevention trials.

“Based on new analyses of the evidence from primary CVD prevention populations, longer-term follow-up data from the Women’s Health Study (WHS) (JE Buring, personal communication, November 23, 2020), and new trial evidence, the USPSTF concluded that the evidence is inadequate that low-dose aspirin use reduces CRC incidence or mortality,” it states.

Optimum dose

On the optimum dose for primary CVD prevention, the task force says the benefit appears similar for a low dose (≤100 mg/d) and all doses that have been studied in CVD prevention trials (50 to 500 mg/d). “A pragmatic approach would be to use 81 mg/d, which is the most commonly prescribed dose in the United States,” it states.

The USPSTF recommends using the ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations to estimate cardiovascular risk but it points out that these equations are imperfect for risk prediction at the individual level, and suggests using these risk estimates as a starting point to discuss with appropriate candidates their desire for daily aspirin use. The benefits of initiating aspirin use are greater for individuals at higher risk for CVD events (eg, those with >15% or >20% 10-year CVD risk), they note.

“Decisions about initiating aspirin use should be based on shared decision-making between clinicians and patients about the potential benefits and harms. Persons who place a higher value on the potential benefits than the potential harms may choose to initiate low-dose aspirin use. Persons who place a higher value on the potential harms or on the burden of taking a daily preventive medication than the potential benefits may choose not to initiate low-dose aspirin use,” the task force says.

It also points out that the risk for bleeding increases modestly with advancing age. “For persons who have initiated aspirin use, the net benefits continue to accrue over time in the absence of a bleeding event. The net benefits, however, become smaller with advancing age because of an increased risk for bleeding, so modeling data suggest that it may be reasonable to consider stopping aspirin use around age 75 years,” it states.

Systematic review

The updated draft recommendations are based on a new systematic review commissioned by the USPSTF on the effectiveness of aspirin to reduce the risk of CVD events (myocardial infarction and stroke), cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality in persons without a history of CVD.

The systematic review also investigated the effect of aspirin use on CRC incidence and mortality in primary CVD prevention populations, as well as the harms, particularly bleeding harms, associated with aspirin use.

In addition to the systematic evidence review, the USPSTF commissioned a microsimulation modeling study to assess the net balance of benefits and harms from aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD and CRC, stratified by age, sex, and CVD risk level. Modeling study parameter inputs were informed by the results of the systematic review, and the primary outcomes were net benefits expressed as quality-adjusted life-years and life-years.

The USPSTF found 13 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that reported on the benefits of aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The total number of participants was 161,680, and most trials used low-dose aspirin of 100 mg/d or less or aspirin every other day. The 13 primary prevention trials included a balanced number of male and female participants and included a broad distribution of ages, with mean age ranging from 53 years in the Physicians’ Health Study to 74 years in the ASPREE trial.

This body of evidence shows that aspirin use for primary prevention of CVD is associated with a decreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke but not cardiovascular mortality or all-cause mortality. Results are quite similar when including studies using all doses of aspirin compared with studies using low-dose aspirin.

The USPSTF reviewed 14 RCTs in CVD primary prevention populations that reported on the bleeding harms of aspirin.

When looking at studies reporting on the harms of low-dose aspirin use (≤100 mg/d), which is most relevant to current practice, a pooled analysis of 10 trials showed that aspirin use was associated with a 58% increase in major gastrointestinal bleeding, and a pooled analysis of 11 trials showed a 31% increase in intracranial bleeds in the aspirin group compared with the control group. Low-dose aspirin use was not associated with a statistically significant increase in risk of fatal hemorrhagic stroke.

Data suggested that the increased risk of bleeding associated with aspirin use occurs relatively quickly after initiating aspirin, and data do not suggest that aspirin has a differential relative bleeding risk based on age, sex, presence of diabetes, level of CVD risk, or race or ethnicity. Although the increase in relative risk does not appear to differ based on age, the absolute risk of bleeding, and thus the magnitude of bleeding harm, does increase with age, and more so in adults age 60 years or older, they note.

The microsimulation model to estimate the magnitude of net benefit of low-dose aspirin use incorporated findings from the systematic review.

Modeling data demonstrated that aspirin use in both men and women ages 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk generally provides a modest net benefit in both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years gained. Initiation of aspirin use in persons aged 60-69 years results in quality-adjusted life-years gained that range from slightly negative to slightly positive depending on CVD risk level, and life-years gained are generally negative.

In persons aged 70-79 years, initiation of aspirin use results in a loss of both quality-adjusted life-years and life-years at essentially all CVD risk levels modeled (ie, up to 20% 10-year CVD risk).

The USPSTF thus determined that aspirin use has a small net benefit in persons aged 40-59 years with 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk, and initiation of aspirin use has no net benefit in persons age 60 years or older.

When looking at net lifetime benefit of continuous aspirin use until stopping at age 65, 70, 75, 80, or 85 years, modeling data suggest that there is generally little incremental lifetime net benefit in continuing aspirin use beyond the age of 75-80 years.

The task force points out that the net benefit of continuing aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s is not the same as the net benefit of initiating aspirin use by a person in their 60s or 70s. This is because, in part, of the fact that CVD risk is heavily influenced by age. Persons who meet the eligibility criteria for aspirin use at a younger age (ie, ≥10% 10-year CVD risk in their 40s or 50s) typically have even higher CVD risk by their 60s or 70s compared with persons who first reach a 10% or greater 10-year CVD risk in their 60s or 70s, and may gain more benefit by continuing aspirin use than a person at lower risk might gain by initiating aspirin use, the USPSTF explains.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Soft Nodule on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

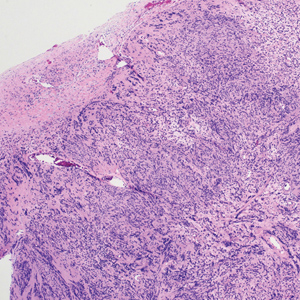

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

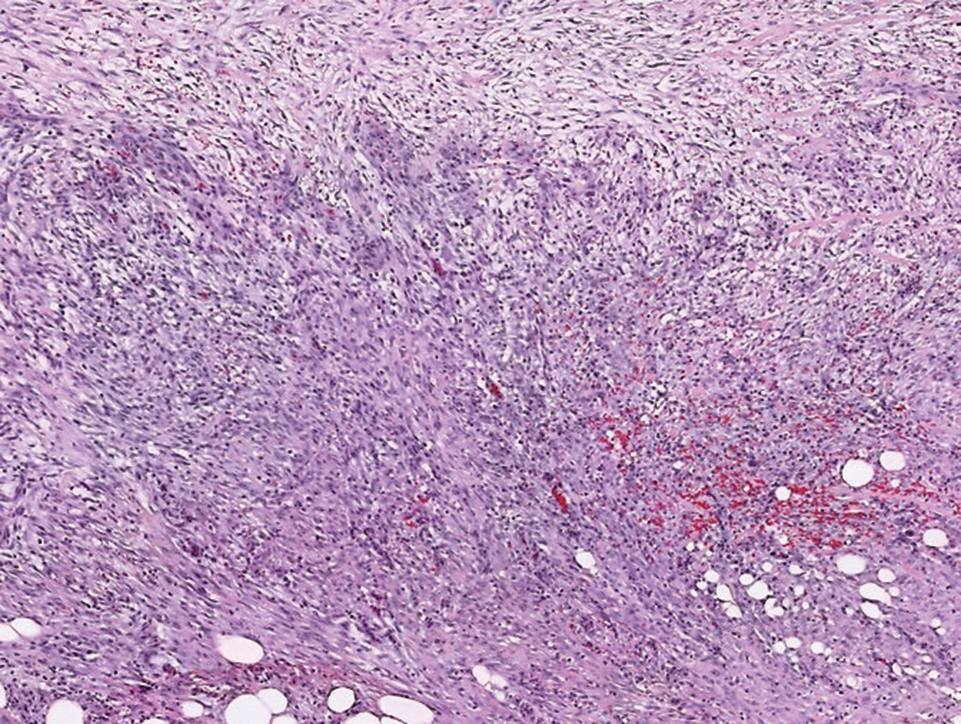

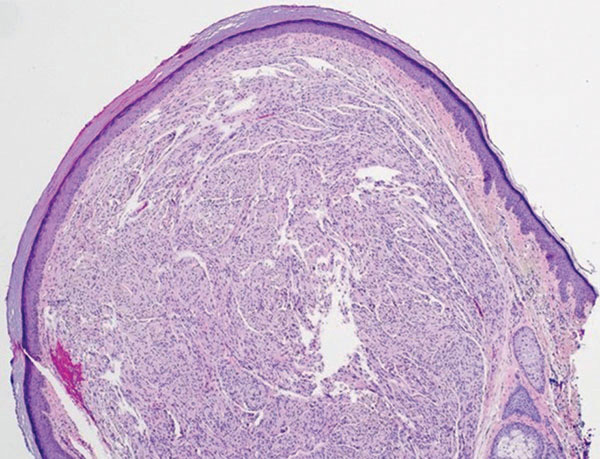

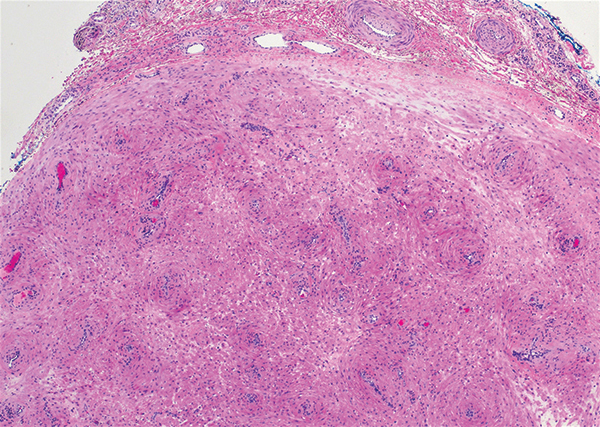

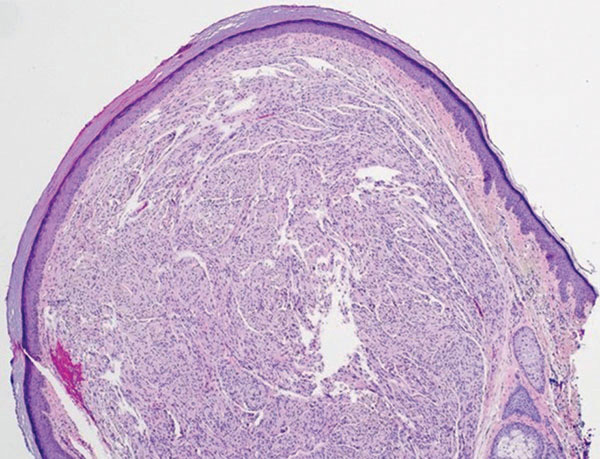

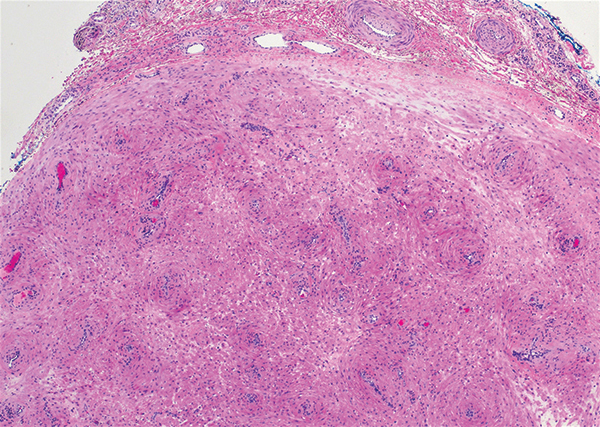

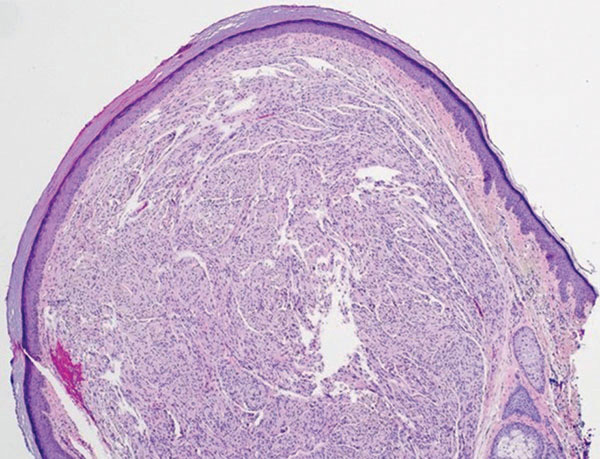

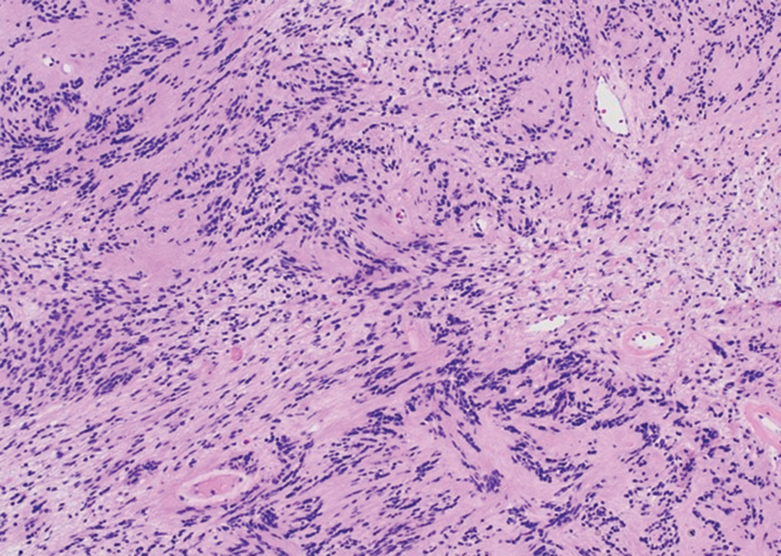

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

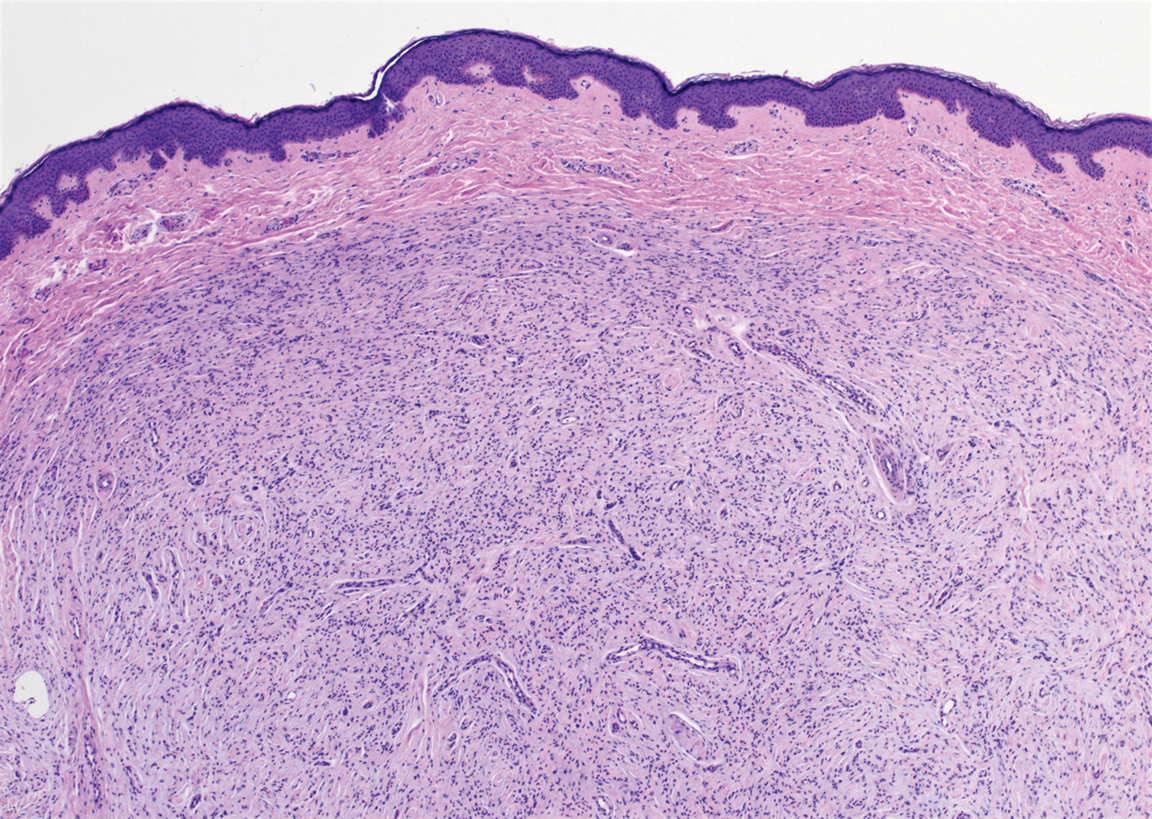

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

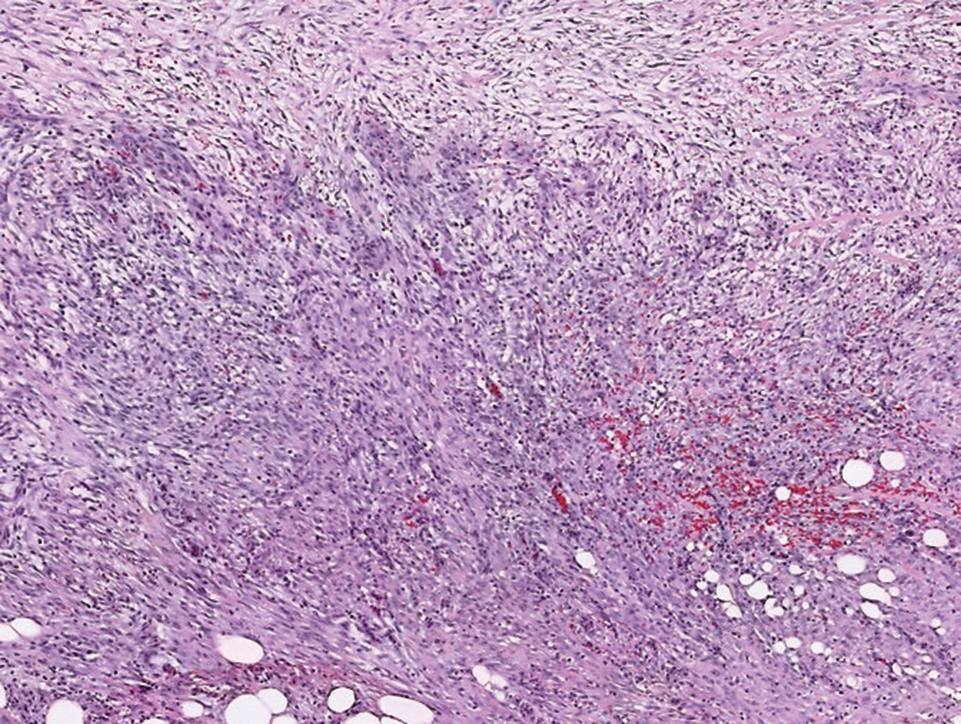

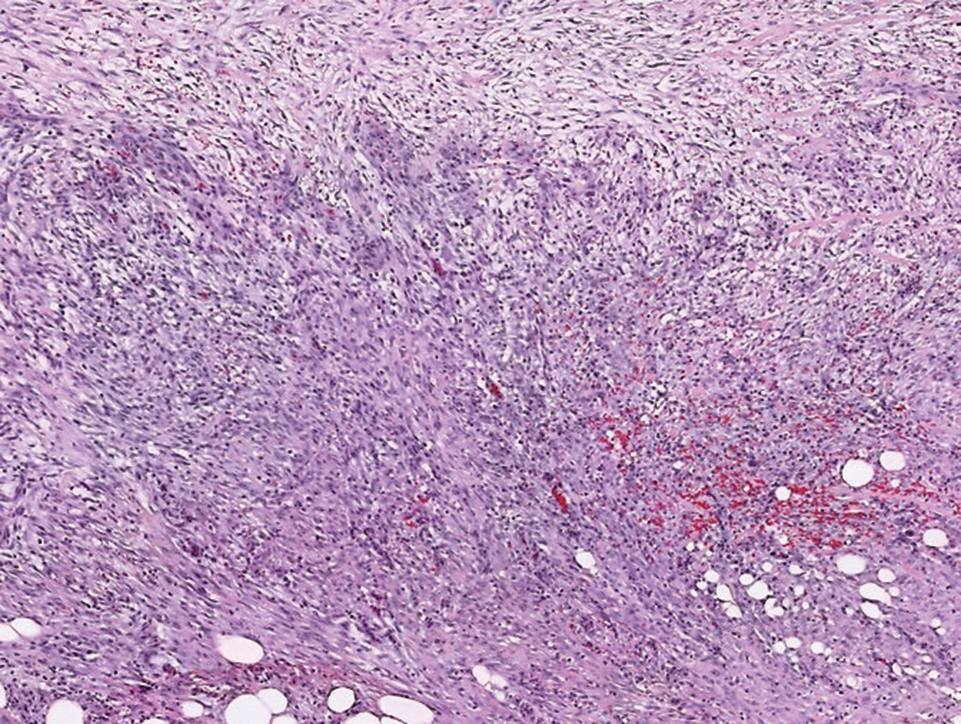

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

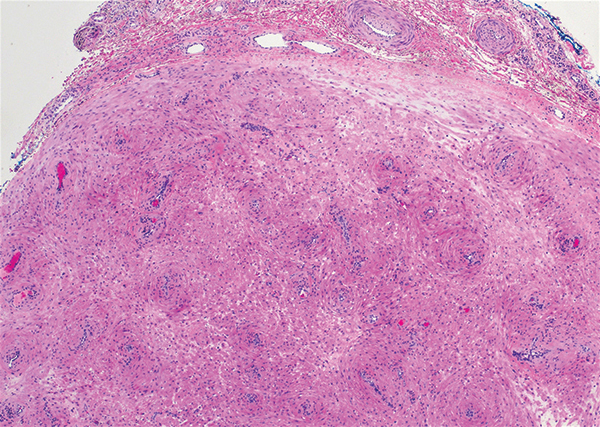

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

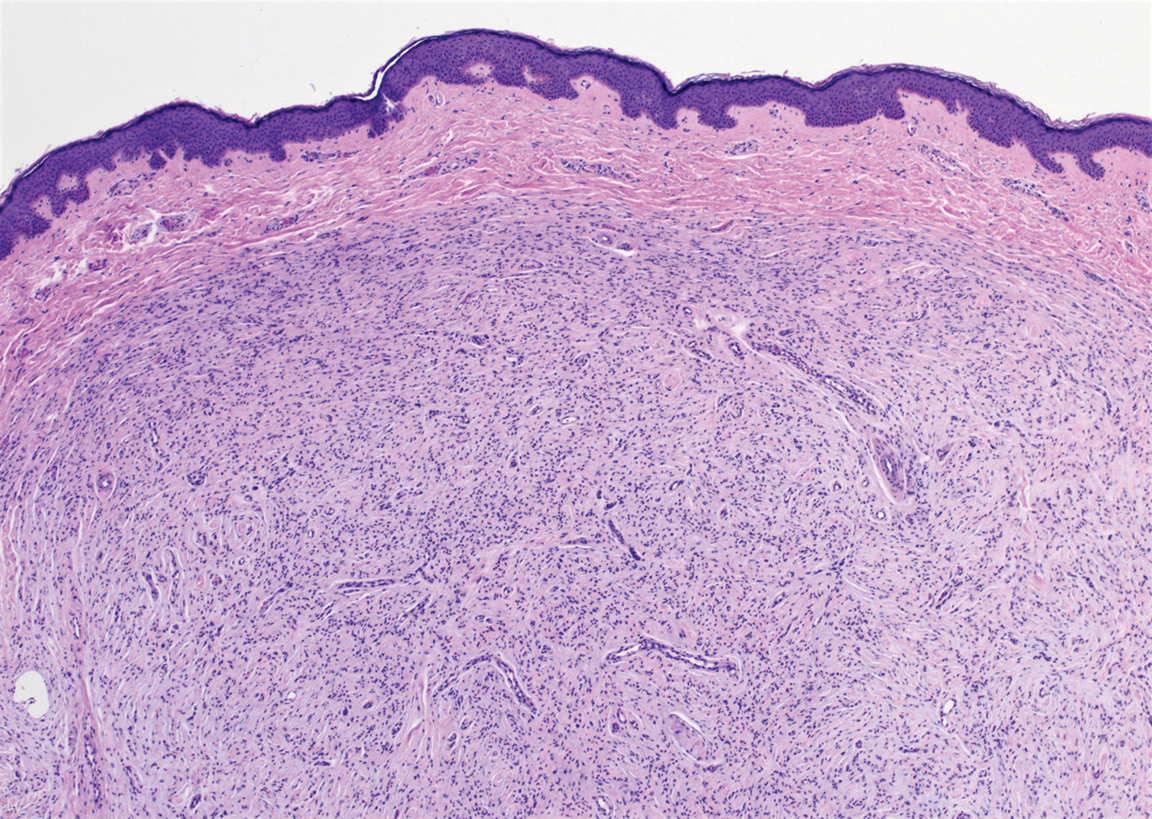

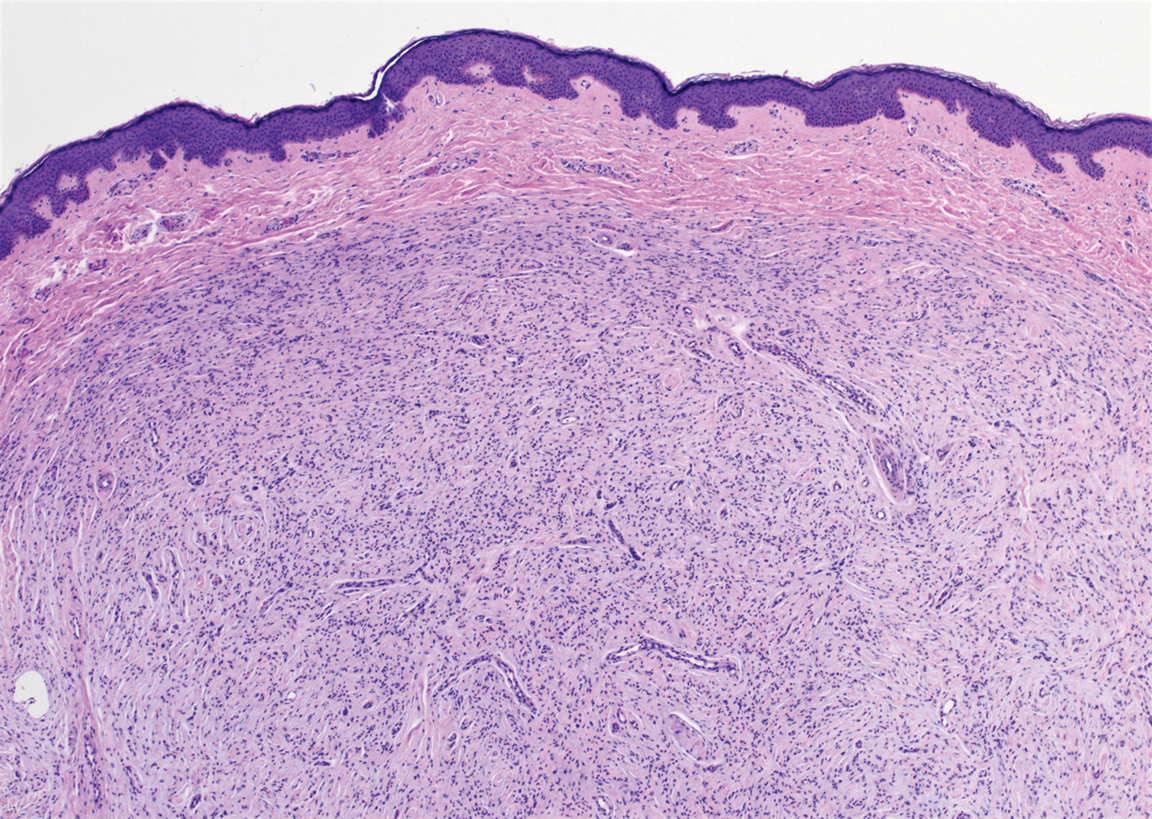

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

A 54-year-old woman presented with an enlarging mass on the right volar forearm. Physical examination revealed a 1-cm, soft, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. Excision revealed tan-pink, indurated, fibrous, nodular tissue.

Product News October 2021

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Things We Do for No Reason™: Routine Use of Corticosteroids for the Treatment of Anaphylaxis

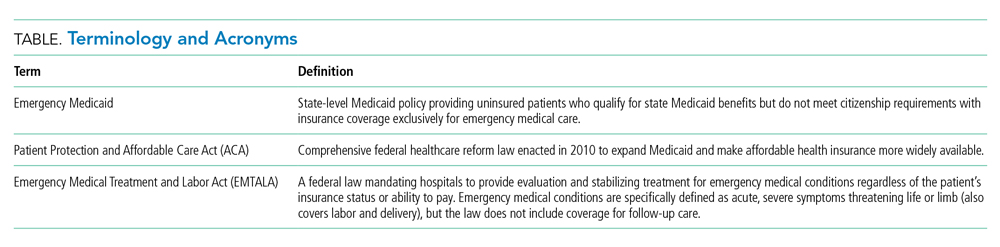

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A 56-year-old man with coronary artery disease (CAD) undergoes hospital treatment for diverticulitis. He receives ketorolac for abdominal pain upon arrival to the medical ward despite his known allergy to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Fifteen minutes after administration, he develops lightheadedness and experiences swelling of his lips. On exam, he has tachycardia and a diffuse urticarial rash across his torso. The admitting physician prescribes methylprednisolone, diphenhydramine, and a liter bolus of normal saline for suspected anaphylaxis. Epinephrine is not administered for fear of precipitating an adverse cardiovascular event given the patient’s history of CAD.

BACKGROUND

Anaphylaxis, a rapid-onset generalized immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated hypersensitivity reaction, can lead to significant morbidity and mortality when not managed properly. Patients can present with anaphylaxis in heterogeneous ways. Fulfilling any one of three criteria establishes the diagnosis of anaphylaxis: (1) rapid onset of skin or mucosal symptoms complicated by either respiratory compromise or hypotension; (2) two or more symptoms involving the respiratory, mucosal, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal systems following exposure to a likely allergen; and (3) reduced blood pressure in response to a known allergen.1 Up to 5% of the population experiences anaphylaxis in a lifetime. Medication and stinging insects account for the majority of anaphylactic reactions in adults, while food and insect stings commonly trigger it in children and adolescents.2

The majority of anaphylactic reactions, known as uniphasic or monophasic, occur rapidly as single episodes following exposure to a specific trigger and resolve within minutes to hours after treatment. Meanwhile, biphasic, or delayed-phase, anaphylaxis occurs when symptoms recur after an apparent resolution and in the absence of reexposure to the trigger. Symptoms restart within 1 to 72 hours after resolution of an initial anaphylaxis episode, with a median time to onset of 11 hours. Biphasic reactions occur in roughly 5% of patients with anaphylaxis.3

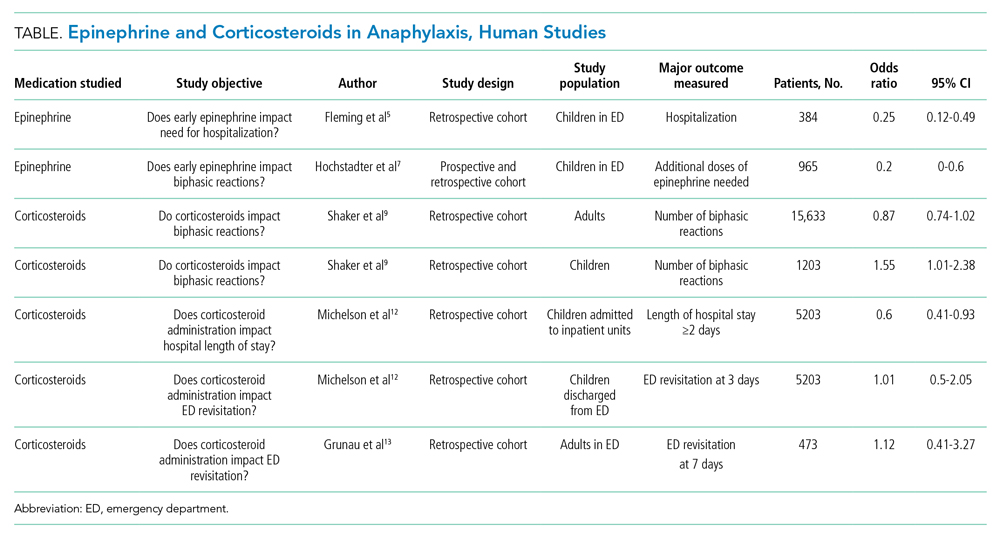

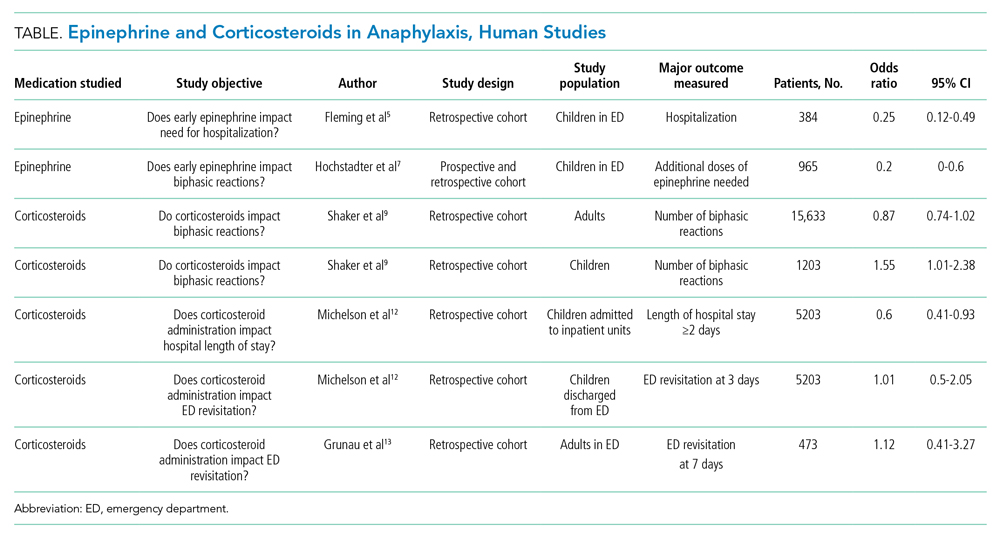

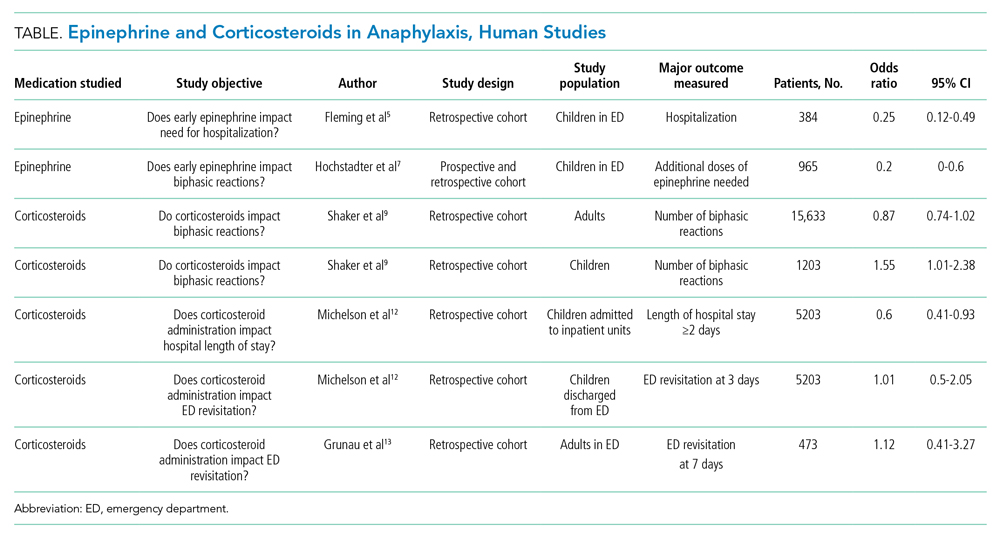

Epinephrine is the only recommended first-line medication for the treatment of anaphylaxis in all age groups.4 Epinephrine counteracts the cardiovascular and respiratory compromise induced by anaphylaxis through its α- and β-adrenergic activity and stabilizes mast cells.4 Early administration of intramuscular epinephrine decreases the need for additional interventions, reduces the likelihood of hospitalization, and is associated with reduced biphasic reactions.5-7 Paradoxically, patients receive corticosteroids more often than epinephrine for suspected anaphylaxis, despite no robust evidence for their efficacy.4,8,9

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK STEROIDS aRE HELPFUL FOR ANAPHYLAXIS