User login

Short-acting opioids needed for withdrawal in U.S. hospitals, say experts

The commentary by Robert A. Kleinman, MD, with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, and department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and Sarah E. Wakeman, MD, with the division of general internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Currently, short-acting opioids are not recommended in the United States for opioid withdrawal symptoms (OWS) management in the hospital, the authors wrote. Instead, withdrawal symptoms are typically treated, followed by methadone or buprenorphine or nonopioid medications, but many patients don’t get enough relief. Undertreated withdrawal can result in patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, which is linked with higher risk of death.

Addiction specialist Elisabeth Poorman, MD, of the University of Illinois Chicago, said in an interview that she agrees it’s time to start shifting the thinking on using short-acting opioids for OWS in hospitals. Use varies greatly by hospital and by clinician, she said.

“It’s time to let evidence guide us and to be flexible,” Dr. Poorman said.

The commentary authors noted that with methadone, patients must wait several hours for maximal symptom reduction, and the full benefits of methadone treatment are not realized until days after initiation.

Rapid initiation of methadone may be feasible in hospitals and has been proposed as an option, but further study is necessary before widespread use, the authors wrote.

Short-acting opioids may address limitations of other opioids

Lofexidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, is the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for OWS.

“However,” the authors said, “more than half of patients with OWS treated with lofexidine in phase 3 efficacy trials dropped out by day five. Clonidine, another alpha-2-agonist used off label to treat OWS, has similar effects to those of lofexidine. “

Therefore, short-acting opioids may complement methadone and buprenorphine in treating OWS in the hospital by addressing their limitations, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman also say short-acting opioids may help with starting buprenorphine for patients exposed to fentanyl, because short-acting opioids can relieve withdrawal symptoms while fentanyl is metabolized and excreted.

Supplementation with short-acting opioids within the hospital can relieve withdrawal symptoms and help keep patients comfortable while methadone is titrated to more effective doses for long-term treatment, they wrote.

With short-acting opioids, patients may become more engaged in their care with, for example, a tamper-proof, patient-controlled analgesia pump, which would allow them to have more autonomy in administration of opioids to relieve pain and withdrawal symptoms, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman noted that many patients who inject drugs already consume short-acting illicit drugs in the hospital, typically in washrooms and smoking areas, so supervised use of short-acting opioids helps eliminate the risk for unwitnessed overdoses.

Barriers to short-acting opioid use

Despite use of short-acting opioids internationally, barriers in the United States include limited prospective, randomized, controlled research on their benefits. There is limited institutional support for such approaches, and concerns and stigma around providing opioids to patients with OUD.

“[M]any institutions have insufficient numbers of providers who are both confident and competent with standard buprenorphine and methadone initiation approaches, a prerequisite before adopting more complex regimens,” the authors wrote.

Short-acting, full-agonist opioids, as a complement to methadone or buprenorphine, is already recommended for inpatients with OUD who are experiencing acute pain.

But the authors argue it should be an option when pain is not present, but methadone or buprenorphine have not provided enough OWS relief.

When short-acting opioids are helpful, according to outside expert

Dr. Poorman agrees and says she has found short-acting opioids simple to use in the hospital and very helpful in two situations.

One is when patients are very clear that they don’t want any medication for opioid use disorder, but they do want to be treated for their acute medical issue.

“I thought that was a fantastic tool to have to demonstrate we’re listening to them and weren’t trying to impose something on them and left the door open to come back when they did want treatment, which many of them did,” Dr. Poorman said.

The second situation is when the patient is uncertain about options but very afraid of precipitated withdrawal from buprenorphine.

She said she then found it easy to switch from those medications to buprenorphine and methadone.

Dr. Poorman described a situation she encountered previously where the patient was injecting heroin several times a day for 30-40 years. He was very clear he wasn’t going to stop injecting heroin, but he needed medical attention. He was willing to get medical attention, but he told his doctor he didn’t want to be uncomfortable while in the hospital.

It was very hard for his doctor to accept relieving his symptoms of withdrawal as part of her job, because she felt as though she was condoning his drug use, Dr. Poorman explained.

But Dr. Poorman said it’s not realistic to think that someone who clearly does not want to stop using is going to stop using because a doctor made that person go through painful withdrawal “that they’ve structured their whole life around avoiding.”

Take-home message

“We need to understand that addiction is very complex. A lot of times people come to us distressed, and it’s a great time to engage them in care but engaging them in care doesn’t mean imposing discomfort or pain on them,” Dr. Poorman noted. Instead, it means “listening to them, helping them be comfortable in a really stressful situation and then letting them know we are always there for them wherever they are on their disease process or recovery journey so that they can come back to us.”

Dr. Wakeman previously served on clinical advisory board for Celero Systems and receives textbook royalties from Springer and author payment from UpToDate. Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Poorman declared no relevant financial relationships.

The commentary by Robert A. Kleinman, MD, with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, and department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and Sarah E. Wakeman, MD, with the division of general internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Currently, short-acting opioids are not recommended in the United States for opioid withdrawal symptoms (OWS) management in the hospital, the authors wrote. Instead, withdrawal symptoms are typically treated, followed by methadone or buprenorphine or nonopioid medications, but many patients don’t get enough relief. Undertreated withdrawal can result in patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, which is linked with higher risk of death.

Addiction specialist Elisabeth Poorman, MD, of the University of Illinois Chicago, said in an interview that she agrees it’s time to start shifting the thinking on using short-acting opioids for OWS in hospitals. Use varies greatly by hospital and by clinician, she said.

“It’s time to let evidence guide us and to be flexible,” Dr. Poorman said.

The commentary authors noted that with methadone, patients must wait several hours for maximal symptom reduction, and the full benefits of methadone treatment are not realized until days after initiation.

Rapid initiation of methadone may be feasible in hospitals and has been proposed as an option, but further study is necessary before widespread use, the authors wrote.

Short-acting opioids may address limitations of other opioids

Lofexidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, is the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for OWS.

“However,” the authors said, “more than half of patients with OWS treated with lofexidine in phase 3 efficacy trials dropped out by day five. Clonidine, another alpha-2-agonist used off label to treat OWS, has similar effects to those of lofexidine. “

Therefore, short-acting opioids may complement methadone and buprenorphine in treating OWS in the hospital by addressing their limitations, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman also say short-acting opioids may help with starting buprenorphine for patients exposed to fentanyl, because short-acting opioids can relieve withdrawal symptoms while fentanyl is metabolized and excreted.

Supplementation with short-acting opioids within the hospital can relieve withdrawal symptoms and help keep patients comfortable while methadone is titrated to more effective doses for long-term treatment, they wrote.

With short-acting opioids, patients may become more engaged in their care with, for example, a tamper-proof, patient-controlled analgesia pump, which would allow them to have more autonomy in administration of opioids to relieve pain and withdrawal symptoms, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman noted that many patients who inject drugs already consume short-acting illicit drugs in the hospital, typically in washrooms and smoking areas, so supervised use of short-acting opioids helps eliminate the risk for unwitnessed overdoses.

Barriers to short-acting opioid use

Despite use of short-acting opioids internationally, barriers in the United States include limited prospective, randomized, controlled research on their benefits. There is limited institutional support for such approaches, and concerns and stigma around providing opioids to patients with OUD.

“[M]any institutions have insufficient numbers of providers who are both confident and competent with standard buprenorphine and methadone initiation approaches, a prerequisite before adopting more complex regimens,” the authors wrote.

Short-acting, full-agonist opioids, as a complement to methadone or buprenorphine, is already recommended for inpatients with OUD who are experiencing acute pain.

But the authors argue it should be an option when pain is not present, but methadone or buprenorphine have not provided enough OWS relief.

When short-acting opioids are helpful, according to outside expert

Dr. Poorman agrees and says she has found short-acting opioids simple to use in the hospital and very helpful in two situations.

One is when patients are very clear that they don’t want any medication for opioid use disorder, but they do want to be treated for their acute medical issue.

“I thought that was a fantastic tool to have to demonstrate we’re listening to them and weren’t trying to impose something on them and left the door open to come back when they did want treatment, which many of them did,” Dr. Poorman said.

The second situation is when the patient is uncertain about options but very afraid of precipitated withdrawal from buprenorphine.

She said she then found it easy to switch from those medications to buprenorphine and methadone.

Dr. Poorman described a situation she encountered previously where the patient was injecting heroin several times a day for 30-40 years. He was very clear he wasn’t going to stop injecting heroin, but he needed medical attention. He was willing to get medical attention, but he told his doctor he didn’t want to be uncomfortable while in the hospital.

It was very hard for his doctor to accept relieving his symptoms of withdrawal as part of her job, because she felt as though she was condoning his drug use, Dr. Poorman explained.

But Dr. Poorman said it’s not realistic to think that someone who clearly does not want to stop using is going to stop using because a doctor made that person go through painful withdrawal “that they’ve structured their whole life around avoiding.”

Take-home message

“We need to understand that addiction is very complex. A lot of times people come to us distressed, and it’s a great time to engage them in care but engaging them in care doesn’t mean imposing discomfort or pain on them,” Dr. Poorman noted. Instead, it means “listening to them, helping them be comfortable in a really stressful situation and then letting them know we are always there for them wherever they are on their disease process or recovery journey so that they can come back to us.”

Dr. Wakeman previously served on clinical advisory board for Celero Systems and receives textbook royalties from Springer and author payment from UpToDate. Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Poorman declared no relevant financial relationships.

The commentary by Robert A. Kleinman, MD, with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, and department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, and Sarah E. Wakeman, MD, with the division of general internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Currently, short-acting opioids are not recommended in the United States for opioid withdrawal symptoms (OWS) management in the hospital, the authors wrote. Instead, withdrawal symptoms are typically treated, followed by methadone or buprenorphine or nonopioid medications, but many patients don’t get enough relief. Undertreated withdrawal can result in patients leaving the hospital against medical advice, which is linked with higher risk of death.

Addiction specialist Elisabeth Poorman, MD, of the University of Illinois Chicago, said in an interview that she agrees it’s time to start shifting the thinking on using short-acting opioids for OWS in hospitals. Use varies greatly by hospital and by clinician, she said.

“It’s time to let evidence guide us and to be flexible,” Dr. Poorman said.

The commentary authors noted that with methadone, patients must wait several hours for maximal symptom reduction, and the full benefits of methadone treatment are not realized until days after initiation.

Rapid initiation of methadone may be feasible in hospitals and has been proposed as an option, but further study is necessary before widespread use, the authors wrote.

Short-acting opioids may address limitations of other opioids

Lofexidine, an alpha-2-adrenergic agonist, is the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for OWS.

“However,” the authors said, “more than half of patients with OWS treated with lofexidine in phase 3 efficacy trials dropped out by day five. Clonidine, another alpha-2-agonist used off label to treat OWS, has similar effects to those of lofexidine. “

Therefore, short-acting opioids may complement methadone and buprenorphine in treating OWS in the hospital by addressing their limitations, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman also say short-acting opioids may help with starting buprenorphine for patients exposed to fentanyl, because short-acting opioids can relieve withdrawal symptoms while fentanyl is metabolized and excreted.

Supplementation with short-acting opioids within the hospital can relieve withdrawal symptoms and help keep patients comfortable while methadone is titrated to more effective doses for long-term treatment, they wrote.

With short-acting opioids, patients may become more engaged in their care with, for example, a tamper-proof, patient-controlled analgesia pump, which would allow them to have more autonomy in administration of opioids to relieve pain and withdrawal symptoms, the authors wrote.

Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Wakeman noted that many patients who inject drugs already consume short-acting illicit drugs in the hospital, typically in washrooms and smoking areas, so supervised use of short-acting opioids helps eliminate the risk for unwitnessed overdoses.

Barriers to short-acting opioid use

Despite use of short-acting opioids internationally, barriers in the United States include limited prospective, randomized, controlled research on their benefits. There is limited institutional support for such approaches, and concerns and stigma around providing opioids to patients with OUD.

“[M]any institutions have insufficient numbers of providers who are both confident and competent with standard buprenorphine and methadone initiation approaches, a prerequisite before adopting more complex regimens,” the authors wrote.

Short-acting, full-agonist opioids, as a complement to methadone or buprenorphine, is already recommended for inpatients with OUD who are experiencing acute pain.

But the authors argue it should be an option when pain is not present, but methadone or buprenorphine have not provided enough OWS relief.

When short-acting opioids are helpful, according to outside expert

Dr. Poorman agrees and says she has found short-acting opioids simple to use in the hospital and very helpful in two situations.

One is when patients are very clear that they don’t want any medication for opioid use disorder, but they do want to be treated for their acute medical issue.

“I thought that was a fantastic tool to have to demonstrate we’re listening to them and weren’t trying to impose something on them and left the door open to come back when they did want treatment, which many of them did,” Dr. Poorman said.

The second situation is when the patient is uncertain about options but very afraid of precipitated withdrawal from buprenorphine.

She said she then found it easy to switch from those medications to buprenorphine and methadone.

Dr. Poorman described a situation she encountered previously where the patient was injecting heroin several times a day for 30-40 years. He was very clear he wasn’t going to stop injecting heroin, but he needed medical attention. He was willing to get medical attention, but he told his doctor he didn’t want to be uncomfortable while in the hospital.

It was very hard for his doctor to accept relieving his symptoms of withdrawal as part of her job, because she felt as though she was condoning his drug use, Dr. Poorman explained.

But Dr. Poorman said it’s not realistic to think that someone who clearly does not want to stop using is going to stop using because a doctor made that person go through painful withdrawal “that they’ve structured their whole life around avoiding.”

Take-home message

“We need to understand that addiction is very complex. A lot of times people come to us distressed, and it’s a great time to engage them in care but engaging them in care doesn’t mean imposing discomfort or pain on them,” Dr. Poorman noted. Instead, it means “listening to them, helping them be comfortable in a really stressful situation and then letting them know we are always there for them wherever they are on their disease process or recovery journey so that they can come back to us.”

Dr. Wakeman previously served on clinical advisory board for Celero Systems and receives textbook royalties from Springer and author payment from UpToDate. Dr. Kleinman and Dr. Poorman declared no relevant financial relationships.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Inexplicably drunk: A case of an underdiagnosed condition?

A 46-year-old North Carolina man, who was pulled over on suspicion of drunk driving, vehemently denied consuming alcohol. When he refused to take a breathalyzer test, he was hospitalized and doctors confirmed what police suspected – his blood alcohol level was 0.20, two-and-a-half times the state’s legal limit – and he was charged with driving while intoxicated (DWI).

For an entire year after his arrest, the cause of his “intoxication” remained a mystery. It wasn’t until his aunt learned about a similar case that had been successfully treated at an Ohio clinic that he understood what was happening to him – he had auto brewery syndrome (ABS).

and suffer all the medical and social implications of alcoholism.

“ABS occurs when ingested carbohydrates are converted to alcohol by fungi in the gastrointestinal tract,” Fahad Malik, MD, who reported the case in BMJ Open Gastroenterology while a resident at Richmond University Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

At the urging of his aunt, the patient attended the Ohio clinic where he underwent a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, immunology panel and urinalysis, all of which were normal.

However, stool testing revealed the presence of two strains of yeast – Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly used in winemaking, baking, and beer brewing, and Saccharomyces boulardii.

To confirm the ABS diagnosis, the patient received a carbohydrate meal and clinicians monitored his blood alcohol level, which, after 8 hours, reached 57 mg/dL. He was treated with antifungals for the Saccharomyces fungi in his stool and discharged on a strict carbohydrate-free diet along with special supplements, including multivitamins and probiotics, but no further antifungal therapy.

Probiotics, said Dr. Malik, competitively inhibit bad bacteria and fungi, but currently there is evidence to show they are useful for ABS.

Although the patient adhered to his prescribed treatment regimen, after a few weeks of no symptoms, intermittent “flares” returned. In one instance of inebriation, he fell and hit his head, resulting in intracranial bleeding that resulted in a transfer to a neurosurgical center. During his hospital stay, his blood alcohol levels ranged from 50 to 400 mg/dL.

Antibiotics the culprit?

Disheartened by the continuation of his symptoms, the patient sought support from an online forum. It was there he read about Dr. Malik and gastroenterologist Prasanna Wickremesinghe, MD (a colleague of Dr. Malik’s at Richmond MC), who had treated a complicated, very similar case of ABS. The patient made contact with the two physicians and they assessed him.

“We went from A to Z with the patient, because we were trying to look for similar things in the history – we wanted to know the exact point at which it started and understand when he started experiencing mental fog,” said Dr. Malik.

After speaking to the patient, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe traced his initial symptoms to a 2011 course of antibiotics (cephalexin 250 mg oral three times a day for 3 weeks) prescribed for a complicated traumatic thumb injury.

About a week after he finished the antibiotics, he experienced noticeable behavioral changes, including depression, brain fog, and aggressive outbursts, all of which were very uncharacteristic.

He visited his primary care physician in 2014 for treatment, which resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist, who treated him with lorazepam and fluoxetine. The patient noted that he was previously healthy, with no significant medical or psychiatric history.

Dr. Malik believes the antibiotics prescribed all those years ago is the culprit. “We were postulating that the antibiotics had changed the microbiome of his gut and allowed the fungi to develop,” he said.

Since there are no established diagnostic criteria or treatment regimen for ABS, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe developed their own.

Diagnosis consisted of a standardized carbohydrate challenge test vs. a carbohydrate meal, where they gave the patient 200 g of glucose by mouth after an overnight fast and drew blood at timed intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours to test for glucose and blood alcohol levels.

“After that we needed to isolate the fungi by examining the gut secretions through an upper and lower endoscopy,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. Fungal cultures from the upper small gut and cecal secretions grew Candida albicans and C. parapsilosis.

Both fungi were sensitive to azoles and the physicians prescribed oral itraconazole 150 mg per day as an initial therapy. After 10 days, his symptoms did not improve so the dose was increased to 200 mg/day and the patient became “completely asymptomatic.”

“We had nothing to follow. We didn’t know how long to treat the patient, it was really just a process of trial and error,” said Dr. Malik. The physicians asked the patient to monitor his breath alcohol levels twice a day during treatment and immediately report any increases. Over time, he also received treatment with various probiotics to help normalize his gut flora.

Underdiagnosed condition?

At the time of the case study’s publication in the summer of 2019, the patient had been asymptomatic for 18 months and had been able to resume a normal diet, but still checks his breath alcohol levels from time to time.

“Before this patient’s case, I went all through the literature and found only a few cases of ABS,” said Dr. Malik.

However, he added, after this case study was published 10 other patients contacted him with a similar history of antibiotic use and the same symptoms. This, said Dr. Malik, is “significant” and suggests ABS is much more common than previously thought.

The clinicians also note that to the best of their knowledge this is the first report of antibiotic exposure initiating ABS.

“What we tried to do was set up a protocol by which to identify these patients, confirm a diagnosis, and treat them for a sufficient amount of time,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. “We also wanted to inform other physicians that this may function as a standardized way of treating these patients, and may promote further study,” added Dr. Malik, who emphasized that the role of probiotics in ABS still needs to be studied.

Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe note that physicians should be aware that mood changes, brain fog, and delirium in patients who deny alcohol ingestion may be the first symptoms of ABS.

Dr. Wickremesinghe said since the case study was published he and Dr. Malik have received queries from all over the world. “It’s unbelievable the amount of interest we have had in the paper, so if we have made the medical community and the general population aware of this condition and how to treat it, we have done a major thing for medicine,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 46-year-old North Carolina man, who was pulled over on suspicion of drunk driving, vehemently denied consuming alcohol. When he refused to take a breathalyzer test, he was hospitalized and doctors confirmed what police suspected – his blood alcohol level was 0.20, two-and-a-half times the state’s legal limit – and he was charged with driving while intoxicated (DWI).

For an entire year after his arrest, the cause of his “intoxication” remained a mystery. It wasn’t until his aunt learned about a similar case that had been successfully treated at an Ohio clinic that he understood what was happening to him – he had auto brewery syndrome (ABS).

and suffer all the medical and social implications of alcoholism.

“ABS occurs when ingested carbohydrates are converted to alcohol by fungi in the gastrointestinal tract,” Fahad Malik, MD, who reported the case in BMJ Open Gastroenterology while a resident at Richmond University Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

At the urging of his aunt, the patient attended the Ohio clinic where he underwent a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, immunology panel and urinalysis, all of which were normal.

However, stool testing revealed the presence of two strains of yeast – Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly used in winemaking, baking, and beer brewing, and Saccharomyces boulardii.

To confirm the ABS diagnosis, the patient received a carbohydrate meal and clinicians monitored his blood alcohol level, which, after 8 hours, reached 57 mg/dL. He was treated with antifungals for the Saccharomyces fungi in his stool and discharged on a strict carbohydrate-free diet along with special supplements, including multivitamins and probiotics, but no further antifungal therapy.

Probiotics, said Dr. Malik, competitively inhibit bad bacteria and fungi, but currently there is evidence to show they are useful for ABS.

Although the patient adhered to his prescribed treatment regimen, after a few weeks of no symptoms, intermittent “flares” returned. In one instance of inebriation, he fell and hit his head, resulting in intracranial bleeding that resulted in a transfer to a neurosurgical center. During his hospital stay, his blood alcohol levels ranged from 50 to 400 mg/dL.

Antibiotics the culprit?

Disheartened by the continuation of his symptoms, the patient sought support from an online forum. It was there he read about Dr. Malik and gastroenterologist Prasanna Wickremesinghe, MD (a colleague of Dr. Malik’s at Richmond MC), who had treated a complicated, very similar case of ABS. The patient made contact with the two physicians and they assessed him.

“We went from A to Z with the patient, because we were trying to look for similar things in the history – we wanted to know the exact point at which it started and understand when he started experiencing mental fog,” said Dr. Malik.

After speaking to the patient, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe traced his initial symptoms to a 2011 course of antibiotics (cephalexin 250 mg oral three times a day for 3 weeks) prescribed for a complicated traumatic thumb injury.

About a week after he finished the antibiotics, he experienced noticeable behavioral changes, including depression, brain fog, and aggressive outbursts, all of which were very uncharacteristic.

He visited his primary care physician in 2014 for treatment, which resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist, who treated him with lorazepam and fluoxetine. The patient noted that he was previously healthy, with no significant medical or psychiatric history.

Dr. Malik believes the antibiotics prescribed all those years ago is the culprit. “We were postulating that the antibiotics had changed the microbiome of his gut and allowed the fungi to develop,” he said.

Since there are no established diagnostic criteria or treatment regimen for ABS, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe developed their own.

Diagnosis consisted of a standardized carbohydrate challenge test vs. a carbohydrate meal, where they gave the patient 200 g of glucose by mouth after an overnight fast and drew blood at timed intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours to test for glucose and blood alcohol levels.

“After that we needed to isolate the fungi by examining the gut secretions through an upper and lower endoscopy,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. Fungal cultures from the upper small gut and cecal secretions grew Candida albicans and C. parapsilosis.

Both fungi were sensitive to azoles and the physicians prescribed oral itraconazole 150 mg per day as an initial therapy. After 10 days, his symptoms did not improve so the dose was increased to 200 mg/day and the patient became “completely asymptomatic.”

“We had nothing to follow. We didn’t know how long to treat the patient, it was really just a process of trial and error,” said Dr. Malik. The physicians asked the patient to monitor his breath alcohol levels twice a day during treatment and immediately report any increases. Over time, he also received treatment with various probiotics to help normalize his gut flora.

Underdiagnosed condition?

At the time of the case study’s publication in the summer of 2019, the patient had been asymptomatic for 18 months and had been able to resume a normal diet, but still checks his breath alcohol levels from time to time.

“Before this patient’s case, I went all through the literature and found only a few cases of ABS,” said Dr. Malik.

However, he added, after this case study was published 10 other patients contacted him with a similar history of antibiotic use and the same symptoms. This, said Dr. Malik, is “significant” and suggests ABS is much more common than previously thought.

The clinicians also note that to the best of their knowledge this is the first report of antibiotic exposure initiating ABS.

“What we tried to do was set up a protocol by which to identify these patients, confirm a diagnosis, and treat them for a sufficient amount of time,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. “We also wanted to inform other physicians that this may function as a standardized way of treating these patients, and may promote further study,” added Dr. Malik, who emphasized that the role of probiotics in ABS still needs to be studied.

Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe note that physicians should be aware that mood changes, brain fog, and delirium in patients who deny alcohol ingestion may be the first symptoms of ABS.

Dr. Wickremesinghe said since the case study was published he and Dr. Malik have received queries from all over the world. “It’s unbelievable the amount of interest we have had in the paper, so if we have made the medical community and the general population aware of this condition and how to treat it, we have done a major thing for medicine,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A 46-year-old North Carolina man, who was pulled over on suspicion of drunk driving, vehemently denied consuming alcohol. When he refused to take a breathalyzer test, he was hospitalized and doctors confirmed what police suspected – his blood alcohol level was 0.20, two-and-a-half times the state’s legal limit – and he was charged with driving while intoxicated (DWI).

For an entire year after his arrest, the cause of his “intoxication” remained a mystery. It wasn’t until his aunt learned about a similar case that had been successfully treated at an Ohio clinic that he understood what was happening to him – he had auto brewery syndrome (ABS).

and suffer all the medical and social implications of alcoholism.

“ABS occurs when ingested carbohydrates are converted to alcohol by fungi in the gastrointestinal tract,” Fahad Malik, MD, who reported the case in BMJ Open Gastroenterology while a resident at Richmond University Medical Center in New York, told this news organization.

At the urging of his aunt, the patient attended the Ohio clinic where he underwent a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, immunology panel and urinalysis, all of which were normal.

However, stool testing revealed the presence of two strains of yeast – Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly used in winemaking, baking, and beer brewing, and Saccharomyces boulardii.

To confirm the ABS diagnosis, the patient received a carbohydrate meal and clinicians monitored his blood alcohol level, which, after 8 hours, reached 57 mg/dL. He was treated with antifungals for the Saccharomyces fungi in his stool and discharged on a strict carbohydrate-free diet along with special supplements, including multivitamins and probiotics, but no further antifungal therapy.

Probiotics, said Dr. Malik, competitively inhibit bad bacteria and fungi, but currently there is evidence to show they are useful for ABS.

Although the patient adhered to his prescribed treatment regimen, after a few weeks of no symptoms, intermittent “flares” returned. In one instance of inebriation, he fell and hit his head, resulting in intracranial bleeding that resulted in a transfer to a neurosurgical center. During his hospital stay, his blood alcohol levels ranged from 50 to 400 mg/dL.

Antibiotics the culprit?

Disheartened by the continuation of his symptoms, the patient sought support from an online forum. It was there he read about Dr. Malik and gastroenterologist Prasanna Wickremesinghe, MD (a colleague of Dr. Malik’s at Richmond MC), who had treated a complicated, very similar case of ABS. The patient made contact with the two physicians and they assessed him.

“We went from A to Z with the patient, because we were trying to look for similar things in the history – we wanted to know the exact point at which it started and understand when he started experiencing mental fog,” said Dr. Malik.

After speaking to the patient, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe traced his initial symptoms to a 2011 course of antibiotics (cephalexin 250 mg oral three times a day for 3 weeks) prescribed for a complicated traumatic thumb injury.

About a week after he finished the antibiotics, he experienced noticeable behavioral changes, including depression, brain fog, and aggressive outbursts, all of which were very uncharacteristic.

He visited his primary care physician in 2014 for treatment, which resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist, who treated him with lorazepam and fluoxetine. The patient noted that he was previously healthy, with no significant medical or psychiatric history.

Dr. Malik believes the antibiotics prescribed all those years ago is the culprit. “We were postulating that the antibiotics had changed the microbiome of his gut and allowed the fungi to develop,” he said.

Since there are no established diagnostic criteria or treatment regimen for ABS, Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe developed their own.

Diagnosis consisted of a standardized carbohydrate challenge test vs. a carbohydrate meal, where they gave the patient 200 g of glucose by mouth after an overnight fast and drew blood at timed intervals of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 hours to test for glucose and blood alcohol levels.

“After that we needed to isolate the fungi by examining the gut secretions through an upper and lower endoscopy,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. Fungal cultures from the upper small gut and cecal secretions grew Candida albicans and C. parapsilosis.

Both fungi were sensitive to azoles and the physicians prescribed oral itraconazole 150 mg per day as an initial therapy. After 10 days, his symptoms did not improve so the dose was increased to 200 mg/day and the patient became “completely asymptomatic.”

“We had nothing to follow. We didn’t know how long to treat the patient, it was really just a process of trial and error,” said Dr. Malik. The physicians asked the patient to monitor his breath alcohol levels twice a day during treatment and immediately report any increases. Over time, he also received treatment with various probiotics to help normalize his gut flora.

Underdiagnosed condition?

At the time of the case study’s publication in the summer of 2019, the patient had been asymptomatic for 18 months and had been able to resume a normal diet, but still checks his breath alcohol levels from time to time.

“Before this patient’s case, I went all through the literature and found only a few cases of ABS,” said Dr. Malik.

However, he added, after this case study was published 10 other patients contacted him with a similar history of antibiotic use and the same symptoms. This, said Dr. Malik, is “significant” and suggests ABS is much more common than previously thought.

The clinicians also note that to the best of their knowledge this is the first report of antibiotic exposure initiating ABS.

“What we tried to do was set up a protocol by which to identify these patients, confirm a diagnosis, and treat them for a sufficient amount of time,” said Dr. Wickremesinghe. “We also wanted to inform other physicians that this may function as a standardized way of treating these patients, and may promote further study,” added Dr. Malik, who emphasized that the role of probiotics in ABS still needs to be studied.

Dr. Malik and Dr. Wickremesinghe note that physicians should be aware that mood changes, brain fog, and delirium in patients who deny alcohol ingestion may be the first symptoms of ABS.

Dr. Wickremesinghe said since the case study was published he and Dr. Malik have received queries from all over the world. “It’s unbelievable the amount of interest we have had in the paper, so if we have made the medical community and the general population aware of this condition and how to treat it, we have done a major thing for medicine,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TikTok trends: Scalp popping, EpiPen tutorial, and plant juice

With the holidays just around the corner (how did that happen?), it’s a good time to remind yourself of the things you’re grateful for.

Perhaps you’re grateful for spending chilly evenings under a warm blanket binge-watching your favorite shows or being able to safely gather with loved ones. If you’re William Shatner, maybe you’re grateful for that quick trip to space (because apparently, that’s a thing now) and the poetic tweets it induced. Down here on earth, TikTok has surpassed 1 billion users, and while we’re not grateful, necessarily, we are entertained.

Here are the latest ugly, good, and bad TikToks that have been trending lately.

The Ugly: Scalp popping

Warning: Don’t watch this if you’re easily freaked out by weird body sounds. It’s like cracking your knuckles but way, way worse.

This TikTok from @asmr.barber has 1.7 million likes, and lots of people are trying it out for themselves. The viral video features the (disturbed) art of scalp popping, also known as hair cracking. It features what is assumed to be some sort of barber or professional (here’s hoping) twisting a client’s hair around his fingers and then yanking, creating an audible popping sound. Many are posting their own hair-cracking attempts on the platform. It’s unclear if this is supposed to feel good or just be grossly satisfying, though some users claim it helps with migraines.

But it turns out this might be more than kind of gross; it can be dangerous, too.

Anthony Youn, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon, comments on the trend with concern: “What the hell is going on here?” Not something you want to hear from a doctor. Dr. Youn explained that the popping sound comes from the galea aponeurotica, a fibrous sheet of connective tissue under your scalp, being pulled off the skull.

In a comment, Dr. Youn continued to warn people of replicating this trend: “It can tear the inside of the scalp, which can bleed a ton on the inside. Think boxer or MMA fighter with scalp hematoma.”

Let’s keep our scalps attached to our skulls, people. If I never have to hear that sound again, I’ll be eternally grateful.

The Good: Doctor demonstrates correct EpiPen use

This reaction TikTok from medical student Mutahir Farhan (aka @madmedicine) has over 252,000 likes and hundreds of comments. In it, Ms. Farhan watches a video of a young woman attempting to administer an EpiPen to her friend, with the caption “How NOT to use an EpiPen” over it (in bright red, of course).

The woman in the video is using the wrong end of the EpiPen against her friend’s leg, so it isn’t working. When she uses her thumb to press down and help, her thumb is actually pressed against the needle end and the EpiPen sticks her instead of her friend. Ouch!

Ms. Farhan goes on to explain the anatomy of the EpiPen and shows his audience of 1.1 million followers where to inject it.

“You gotta remember that the orange tip is where the needle comes out. Otherwise, you’re going to end up stabbing yourself with epinephrine, like that girl in the video,” Ms. Farhan says. He goes on to instruct the important, but often overlooked, follow-up: “After you stab someone with epinephrine, call 911 or go to the ER, so that we can make sure they’re actually okay and good to go.”

The Bad: Liquid chlorophyll

Here is another one of those tricky trends that are so widespread and popular that it’s hard to find exactly where it originated from. A video from @lenamaiah has over 5 million views and 800,000 likes, which even by TikTok standards, is a lot. TikTok is rife with similar videos, which feature drops of liquid chlorophyll being added to water and smoothies.

The pretty emerald hue is mesmerizing and it’s hard to resist trying it out when it’s being peddled by seemingly every pretty, smooth-skinned pseudo-model on the platform. In this video, Lena says drinking a glass of water with a few drops of chlorophyll can reduce inflammation, get rid of eye bags, boost your vitamin levels, reduce free radical damage, detoxify your system, and file your taxes. Okay, I made that last one up, but it follows, doesn’t it? This stuff sounds pretty good. Maybe too good.

Chlorophyll, if you skipped biology class (somehow, I doubt you did), is what makes plants green. Medscape has a detailed explanation of chlorophyll, but all you really need to know is that it’s the secret to that cool thing plants do: photosynthesis, or turning sunlight into energy. Scientists have been trying to find uses for it in people since the 1940s. Unfortunately, studies never found much that it can do for us, aside from being kind of deodorizing. So, while it’s been historically marketed as toothpaste and deodorant, the new TikTok claims of it being a cure-all or the next big skincare supplement are not widely substantiated by scientific studies. The only real evidence of it being effective is word of mouth from those who claim to like the way they look or feel since taking it, which isn’t enough for doctors to recommend it.

TikTok’s resident dermatologist, Muneeb Shah, DO, stitched a TikTok from another user, with his captions explaining, “[There’s] no scientific evidence for liquid chlorophyll [helping] rosacea or acne.”

His advice: “Chlorophyll is great, but just eat more veggies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the holidays just around the corner (how did that happen?), it’s a good time to remind yourself of the things you’re grateful for.

Perhaps you’re grateful for spending chilly evenings under a warm blanket binge-watching your favorite shows or being able to safely gather with loved ones. If you’re William Shatner, maybe you’re grateful for that quick trip to space (because apparently, that’s a thing now) and the poetic tweets it induced. Down here on earth, TikTok has surpassed 1 billion users, and while we’re not grateful, necessarily, we are entertained.

Here are the latest ugly, good, and bad TikToks that have been trending lately.

The Ugly: Scalp popping

Warning: Don’t watch this if you’re easily freaked out by weird body sounds. It’s like cracking your knuckles but way, way worse.

This TikTok from @asmr.barber has 1.7 million likes, and lots of people are trying it out for themselves. The viral video features the (disturbed) art of scalp popping, also known as hair cracking. It features what is assumed to be some sort of barber or professional (here’s hoping) twisting a client’s hair around his fingers and then yanking, creating an audible popping sound. Many are posting their own hair-cracking attempts on the platform. It’s unclear if this is supposed to feel good or just be grossly satisfying, though some users claim it helps with migraines.

But it turns out this might be more than kind of gross; it can be dangerous, too.

Anthony Youn, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon, comments on the trend with concern: “What the hell is going on here?” Not something you want to hear from a doctor. Dr. Youn explained that the popping sound comes from the galea aponeurotica, a fibrous sheet of connective tissue under your scalp, being pulled off the skull.

In a comment, Dr. Youn continued to warn people of replicating this trend: “It can tear the inside of the scalp, which can bleed a ton on the inside. Think boxer or MMA fighter with scalp hematoma.”

Let’s keep our scalps attached to our skulls, people. If I never have to hear that sound again, I’ll be eternally grateful.

The Good: Doctor demonstrates correct EpiPen use

This reaction TikTok from medical student Mutahir Farhan (aka @madmedicine) has over 252,000 likes and hundreds of comments. In it, Ms. Farhan watches a video of a young woman attempting to administer an EpiPen to her friend, with the caption “How NOT to use an EpiPen” over it (in bright red, of course).

The woman in the video is using the wrong end of the EpiPen against her friend’s leg, so it isn’t working. When she uses her thumb to press down and help, her thumb is actually pressed against the needle end and the EpiPen sticks her instead of her friend. Ouch!

Ms. Farhan goes on to explain the anatomy of the EpiPen and shows his audience of 1.1 million followers where to inject it.

“You gotta remember that the orange tip is where the needle comes out. Otherwise, you’re going to end up stabbing yourself with epinephrine, like that girl in the video,” Ms. Farhan says. He goes on to instruct the important, but often overlooked, follow-up: “After you stab someone with epinephrine, call 911 or go to the ER, so that we can make sure they’re actually okay and good to go.”

The Bad: Liquid chlorophyll

Here is another one of those tricky trends that are so widespread and popular that it’s hard to find exactly where it originated from. A video from @lenamaiah has over 5 million views and 800,000 likes, which even by TikTok standards, is a lot. TikTok is rife with similar videos, which feature drops of liquid chlorophyll being added to water and smoothies.

The pretty emerald hue is mesmerizing and it’s hard to resist trying it out when it’s being peddled by seemingly every pretty, smooth-skinned pseudo-model on the platform. In this video, Lena says drinking a glass of water with a few drops of chlorophyll can reduce inflammation, get rid of eye bags, boost your vitamin levels, reduce free radical damage, detoxify your system, and file your taxes. Okay, I made that last one up, but it follows, doesn’t it? This stuff sounds pretty good. Maybe too good.

Chlorophyll, if you skipped biology class (somehow, I doubt you did), is what makes plants green. Medscape has a detailed explanation of chlorophyll, but all you really need to know is that it’s the secret to that cool thing plants do: photosynthesis, or turning sunlight into energy. Scientists have been trying to find uses for it in people since the 1940s. Unfortunately, studies never found much that it can do for us, aside from being kind of deodorizing. So, while it’s been historically marketed as toothpaste and deodorant, the new TikTok claims of it being a cure-all or the next big skincare supplement are not widely substantiated by scientific studies. The only real evidence of it being effective is word of mouth from those who claim to like the way they look or feel since taking it, which isn’t enough for doctors to recommend it.

TikTok’s resident dermatologist, Muneeb Shah, DO, stitched a TikTok from another user, with his captions explaining, “[There’s] no scientific evidence for liquid chlorophyll [helping] rosacea or acne.”

His advice: “Chlorophyll is great, but just eat more veggies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With the holidays just around the corner (how did that happen?), it’s a good time to remind yourself of the things you’re grateful for.

Perhaps you’re grateful for spending chilly evenings under a warm blanket binge-watching your favorite shows or being able to safely gather with loved ones. If you’re William Shatner, maybe you’re grateful for that quick trip to space (because apparently, that’s a thing now) and the poetic tweets it induced. Down here on earth, TikTok has surpassed 1 billion users, and while we’re not grateful, necessarily, we are entertained.

Here are the latest ugly, good, and bad TikToks that have been trending lately.

The Ugly: Scalp popping

Warning: Don’t watch this if you’re easily freaked out by weird body sounds. It’s like cracking your knuckles but way, way worse.

This TikTok from @asmr.barber has 1.7 million likes, and lots of people are trying it out for themselves. The viral video features the (disturbed) art of scalp popping, also known as hair cracking. It features what is assumed to be some sort of barber or professional (here’s hoping) twisting a client’s hair around his fingers and then yanking, creating an audible popping sound. Many are posting their own hair-cracking attempts on the platform. It’s unclear if this is supposed to feel good or just be grossly satisfying, though some users claim it helps with migraines.

But it turns out this might be more than kind of gross; it can be dangerous, too.

Anthony Youn, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon, comments on the trend with concern: “What the hell is going on here?” Not something you want to hear from a doctor. Dr. Youn explained that the popping sound comes from the galea aponeurotica, a fibrous sheet of connective tissue under your scalp, being pulled off the skull.

In a comment, Dr. Youn continued to warn people of replicating this trend: “It can tear the inside of the scalp, which can bleed a ton on the inside. Think boxer or MMA fighter with scalp hematoma.”

Let’s keep our scalps attached to our skulls, people. If I never have to hear that sound again, I’ll be eternally grateful.

The Good: Doctor demonstrates correct EpiPen use

This reaction TikTok from medical student Mutahir Farhan (aka @madmedicine) has over 252,000 likes and hundreds of comments. In it, Ms. Farhan watches a video of a young woman attempting to administer an EpiPen to her friend, with the caption “How NOT to use an EpiPen” over it (in bright red, of course).

The woman in the video is using the wrong end of the EpiPen against her friend’s leg, so it isn’t working. When she uses her thumb to press down and help, her thumb is actually pressed against the needle end and the EpiPen sticks her instead of her friend. Ouch!

Ms. Farhan goes on to explain the anatomy of the EpiPen and shows his audience of 1.1 million followers where to inject it.

“You gotta remember that the orange tip is where the needle comes out. Otherwise, you’re going to end up stabbing yourself with epinephrine, like that girl in the video,” Ms. Farhan says. He goes on to instruct the important, but often overlooked, follow-up: “After you stab someone with epinephrine, call 911 or go to the ER, so that we can make sure they’re actually okay and good to go.”

The Bad: Liquid chlorophyll

Here is another one of those tricky trends that are so widespread and popular that it’s hard to find exactly where it originated from. A video from @lenamaiah has over 5 million views and 800,000 likes, which even by TikTok standards, is a lot. TikTok is rife with similar videos, which feature drops of liquid chlorophyll being added to water and smoothies.

The pretty emerald hue is mesmerizing and it’s hard to resist trying it out when it’s being peddled by seemingly every pretty, smooth-skinned pseudo-model on the platform. In this video, Lena says drinking a glass of water with a few drops of chlorophyll can reduce inflammation, get rid of eye bags, boost your vitamin levels, reduce free radical damage, detoxify your system, and file your taxes. Okay, I made that last one up, but it follows, doesn’t it? This stuff sounds pretty good. Maybe too good.

Chlorophyll, if you skipped biology class (somehow, I doubt you did), is what makes plants green. Medscape has a detailed explanation of chlorophyll, but all you really need to know is that it’s the secret to that cool thing plants do: photosynthesis, or turning sunlight into energy. Scientists have been trying to find uses for it in people since the 1940s. Unfortunately, studies never found much that it can do for us, aside from being kind of deodorizing. So, while it’s been historically marketed as toothpaste and deodorant, the new TikTok claims of it being a cure-all or the next big skincare supplement are not widely substantiated by scientific studies. The only real evidence of it being effective is word of mouth from those who claim to like the way they look or feel since taking it, which isn’t enough for doctors to recommend it.

TikTok’s resident dermatologist, Muneeb Shah, DO, stitched a TikTok from another user, with his captions explaining, “[There’s] no scientific evidence for liquid chlorophyll [helping] rosacea or acne.”

His advice: “Chlorophyll is great, but just eat more veggies.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Misleading’ results in colchicine COVID-19 trials meta-analysis

A new meta-analysis appears to show that colchicine has no benefit as a treatment for COVID-19, but its inclusion of trials studying differing patient populations and testing different outcomes led to “misleading” results, says a researcher involved in one of the trials.

The meta-analysis, which includes data from the recent Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, was published Nov. 22 in RMD Open.

Kedar Gautambhai Mehta, MBBS, MD, of the GMERS Medical College Gotri in Vadodara, India, and colleagues included outcomes from six studies of 16,148 patients with COVID-19 who received colchicine or supportive care. They evaluated the efficacy outcomes of mortality, need for ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and length of stay in hospital, as well as safety outcomes of adverse events, serious adverse events, and diarrhea.

The studies in the meta-analysis included a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 105 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Greece, the international, open-label RECOVERY RCT of 11,340 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, an RCT of 72 hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 in Brazil, an RCT of 100 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Iran, the international COLCORONA trial of 4,488 patients with COVID-19 who were treated with colchicine or placebo on an outpatient basis, and the randomized COLORIT trial of 43 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Russia.

Studies “asked very different questions” about colchicine

Commenting on the meta-analysis, Michael H. Pillinger, MD, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular pharmacology with New York University, said the authors combined studies “that are not comparable and that asked very different questions.” Two of the studies in the meta-analysis are very large, and four are very small, which skews the results, he explained.

“The larger studies therefore drive the outcome, and while the small studies are potentially insight providing, the large studies are the only ones worth giving our attention to in the context of the meta-analysis,” he said. The two largest studies – RECOVERY and COLCORONA – taken together show no benefit for colchicine as a treatment, even though the former demonstrated no benefit and the latter did show a benefit, explained Dr. Pillinger, a co–principal investigator for the COLCORONA trial in the United States.

The studies were designed differently and should not have been included in the same analysis, Dr. Pillinger argued. In the case of COLCORONA, early treatment with colchicine was the intervention, whereas RECOVERY focused on hospitalized patients.

“In designing [COLCORONA], the author group (of whom I was a member) expressly rejected the idea that colchicine might be useful for the sicker hospitalized patients, based on the long experience with colchicine of some of us as rheumatologists,” Dr. Pillinger said.

“In short, COLCORONA proved a benefit of colchicine in outpatient COVID-19, and its authors presumed there would be no inpatient benefit; RECOVERY went ahead and proved a lack of inpatient benefit, at least when high-dose steroids were also given,” he said. “While there is no conflict between these results, the combination of the two studies in this meta-analysis suggests there might be no benefit for colchicine overall, which is misleading and can lead physicians to reject the potential of outpatient colchicine, even for future studies.”

Dr. Pillinger said he still believes colchicine has potential value as a COVID-19 treatment option for patients with mild disease, “especially for low–vaccine rate, resource-starved countries.

“It would be unfortunate if meta-analyses such as this one would put a stop to colchicine’s use, or at least its further investigation,” he said.

Study details

The authors of the study assessed heterogeneity of the trials’ data across the outcomes using an I2 test. They evaluated the quality of the evidence for the outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

The results of their meta-analysis showed that colchicine offered no significant improvement in mortality in six studies (risk difference, –0.0; 95% confidence interval, –0.01 to 0.01; I2 = 15%). It showed no benefit with respect to requiring ventilatory support in five studies of 15,519 patients (risk ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.38-1.21; I2 = 47%); being admitted to the ICU in three studies with 220 patients (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.19-1.25; I2 = 34%); and length of stay while in the hospital in four studies of 11,560 patients (mean difference, –1.17; 95% CI, –3.02 to 0.67; I2 = 77%).

There was no difference in serious adverse events in three studies with 4,665 patients (RD, –0.01; 95% CI, –0.02 to 0.00; I2 = 28%) for patients who received colchicine, compared with supportive care alone. Patients who received colchicine were more likely to have a higher rate of adverse events (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.07-2.33; I2 = 81%) and to experience diarrhea (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.62-2.29; I2 = 0%) than were patients who received supportive care alone. The researchers note that for most outcomes, the GRADE quality of evidence was moderate.

“Our findings on colchicine should be interpreted cautiously due to the inclusion of open-labeled, randomized clinical trials,” Dr. Mehta and colleagues write. “The analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes are based on a small number of RCTs in control interventions.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pillinger is co–principal investigator of the U.S. component of the COLCORONA trial; he reported no other relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new meta-analysis appears to show that colchicine has no benefit as a treatment for COVID-19, but its inclusion of trials studying differing patient populations and testing different outcomes led to “misleading” results, says a researcher involved in one of the trials.

The meta-analysis, which includes data from the recent Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, was published Nov. 22 in RMD Open.

Kedar Gautambhai Mehta, MBBS, MD, of the GMERS Medical College Gotri in Vadodara, India, and colleagues included outcomes from six studies of 16,148 patients with COVID-19 who received colchicine or supportive care. They evaluated the efficacy outcomes of mortality, need for ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and length of stay in hospital, as well as safety outcomes of adverse events, serious adverse events, and diarrhea.

The studies in the meta-analysis included a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 105 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Greece, the international, open-label RECOVERY RCT of 11,340 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, an RCT of 72 hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 in Brazil, an RCT of 100 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Iran, the international COLCORONA trial of 4,488 patients with COVID-19 who were treated with colchicine or placebo on an outpatient basis, and the randomized COLORIT trial of 43 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Russia.

Studies “asked very different questions” about colchicine

Commenting on the meta-analysis, Michael H. Pillinger, MD, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular pharmacology with New York University, said the authors combined studies “that are not comparable and that asked very different questions.” Two of the studies in the meta-analysis are very large, and four are very small, which skews the results, he explained.

“The larger studies therefore drive the outcome, and while the small studies are potentially insight providing, the large studies are the only ones worth giving our attention to in the context of the meta-analysis,” he said. The two largest studies – RECOVERY and COLCORONA – taken together show no benefit for colchicine as a treatment, even though the former demonstrated no benefit and the latter did show a benefit, explained Dr. Pillinger, a co–principal investigator for the COLCORONA trial in the United States.

The studies were designed differently and should not have been included in the same analysis, Dr. Pillinger argued. In the case of COLCORONA, early treatment with colchicine was the intervention, whereas RECOVERY focused on hospitalized patients.

“In designing [COLCORONA], the author group (of whom I was a member) expressly rejected the idea that colchicine might be useful for the sicker hospitalized patients, based on the long experience with colchicine of some of us as rheumatologists,” Dr. Pillinger said.

“In short, COLCORONA proved a benefit of colchicine in outpatient COVID-19, and its authors presumed there would be no inpatient benefit; RECOVERY went ahead and proved a lack of inpatient benefit, at least when high-dose steroids were also given,” he said. “While there is no conflict between these results, the combination of the two studies in this meta-analysis suggests there might be no benefit for colchicine overall, which is misleading and can lead physicians to reject the potential of outpatient colchicine, even for future studies.”

Dr. Pillinger said he still believes colchicine has potential value as a COVID-19 treatment option for patients with mild disease, “especially for low–vaccine rate, resource-starved countries.

“It would be unfortunate if meta-analyses such as this one would put a stop to colchicine’s use, or at least its further investigation,” he said.

Study details

The authors of the study assessed heterogeneity of the trials’ data across the outcomes using an I2 test. They evaluated the quality of the evidence for the outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

The results of their meta-analysis showed that colchicine offered no significant improvement in mortality in six studies (risk difference, –0.0; 95% confidence interval, –0.01 to 0.01; I2 = 15%). It showed no benefit with respect to requiring ventilatory support in five studies of 15,519 patients (risk ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.38-1.21; I2 = 47%); being admitted to the ICU in three studies with 220 patients (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.19-1.25; I2 = 34%); and length of stay while in the hospital in four studies of 11,560 patients (mean difference, –1.17; 95% CI, –3.02 to 0.67; I2 = 77%).

There was no difference in serious adverse events in three studies with 4,665 patients (RD, –0.01; 95% CI, –0.02 to 0.00; I2 = 28%) for patients who received colchicine, compared with supportive care alone. Patients who received colchicine were more likely to have a higher rate of adverse events (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.07-2.33; I2 = 81%) and to experience diarrhea (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.62-2.29; I2 = 0%) than were patients who received supportive care alone. The researchers note that for most outcomes, the GRADE quality of evidence was moderate.

“Our findings on colchicine should be interpreted cautiously due to the inclusion of open-labeled, randomized clinical trials,” Dr. Mehta and colleagues write. “The analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes are based on a small number of RCTs in control interventions.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pillinger is co–principal investigator of the U.S. component of the COLCORONA trial; he reported no other relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new meta-analysis appears to show that colchicine has no benefit as a treatment for COVID-19, but its inclusion of trials studying differing patient populations and testing different outcomes led to “misleading” results, says a researcher involved in one of the trials.

The meta-analysis, which includes data from the recent Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, was published Nov. 22 in RMD Open.

Kedar Gautambhai Mehta, MBBS, MD, of the GMERS Medical College Gotri in Vadodara, India, and colleagues included outcomes from six studies of 16,148 patients with COVID-19 who received colchicine or supportive care. They evaluated the efficacy outcomes of mortality, need for ventilation, intensive care unit admission, and length of stay in hospital, as well as safety outcomes of adverse events, serious adverse events, and diarrhea.

The studies in the meta-analysis included a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of 105 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Greece, the international, open-label RECOVERY RCT of 11,340 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, an RCT of 72 hospitalized patients with moderate or severe COVID-19 in Brazil, an RCT of 100 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Iran, the international COLCORONA trial of 4,488 patients with COVID-19 who were treated with colchicine or placebo on an outpatient basis, and the randomized COLORIT trial of 43 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Russia.

Studies “asked very different questions” about colchicine

Commenting on the meta-analysis, Michael H. Pillinger, MD, a rheumatologist and professor of medicine, biochemistry, and molecular pharmacology with New York University, said the authors combined studies “that are not comparable and that asked very different questions.” Two of the studies in the meta-analysis are very large, and four are very small, which skews the results, he explained.

“The larger studies therefore drive the outcome, and while the small studies are potentially insight providing, the large studies are the only ones worth giving our attention to in the context of the meta-analysis,” he said. The two largest studies – RECOVERY and COLCORONA – taken together show no benefit for colchicine as a treatment, even though the former demonstrated no benefit and the latter did show a benefit, explained Dr. Pillinger, a co–principal investigator for the COLCORONA trial in the United States.

The studies were designed differently and should not have been included in the same analysis, Dr. Pillinger argued. In the case of COLCORONA, early treatment with colchicine was the intervention, whereas RECOVERY focused on hospitalized patients.

“In designing [COLCORONA], the author group (of whom I was a member) expressly rejected the idea that colchicine might be useful for the sicker hospitalized patients, based on the long experience with colchicine of some of us as rheumatologists,” Dr. Pillinger said.

“In short, COLCORONA proved a benefit of colchicine in outpatient COVID-19, and its authors presumed there would be no inpatient benefit; RECOVERY went ahead and proved a lack of inpatient benefit, at least when high-dose steroids were also given,” he said. “While there is no conflict between these results, the combination of the two studies in this meta-analysis suggests there might be no benefit for colchicine overall, which is misleading and can lead physicians to reject the potential of outpatient colchicine, even for future studies.”

Dr. Pillinger said he still believes colchicine has potential value as a COVID-19 treatment option for patients with mild disease, “especially for low–vaccine rate, resource-starved countries.

“It would be unfortunate if meta-analyses such as this one would put a stop to colchicine’s use, or at least its further investigation,” he said.

Study details

The authors of the study assessed heterogeneity of the trials’ data across the outcomes using an I2 test. They evaluated the quality of the evidence for the outcomes using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).

The results of their meta-analysis showed that colchicine offered no significant improvement in mortality in six studies (risk difference, –0.0; 95% confidence interval, –0.01 to 0.01; I2 = 15%). It showed no benefit with respect to requiring ventilatory support in five studies of 15,519 patients (risk ratio, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.38-1.21; I2 = 47%); being admitted to the ICU in three studies with 220 patients (RR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.19-1.25; I2 = 34%); and length of stay while in the hospital in four studies of 11,560 patients (mean difference, –1.17; 95% CI, –3.02 to 0.67; I2 = 77%).

There was no difference in serious adverse events in three studies with 4,665 patients (RD, –0.01; 95% CI, –0.02 to 0.00; I2 = 28%) for patients who received colchicine, compared with supportive care alone. Patients who received colchicine were more likely to have a higher rate of adverse events (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.07-2.33; I2 = 81%) and to experience diarrhea (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.62-2.29; I2 = 0%) than were patients who received supportive care alone. The researchers note that for most outcomes, the GRADE quality of evidence was moderate.

“Our findings on colchicine should be interpreted cautiously due to the inclusion of open-labeled, randomized clinical trials,” Dr. Mehta and colleagues write. “The analysis of efficacy and safety outcomes are based on a small number of RCTs in control interventions.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pillinger is co–principal investigator of the U.S. component of the COLCORONA trial; he reported no other relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

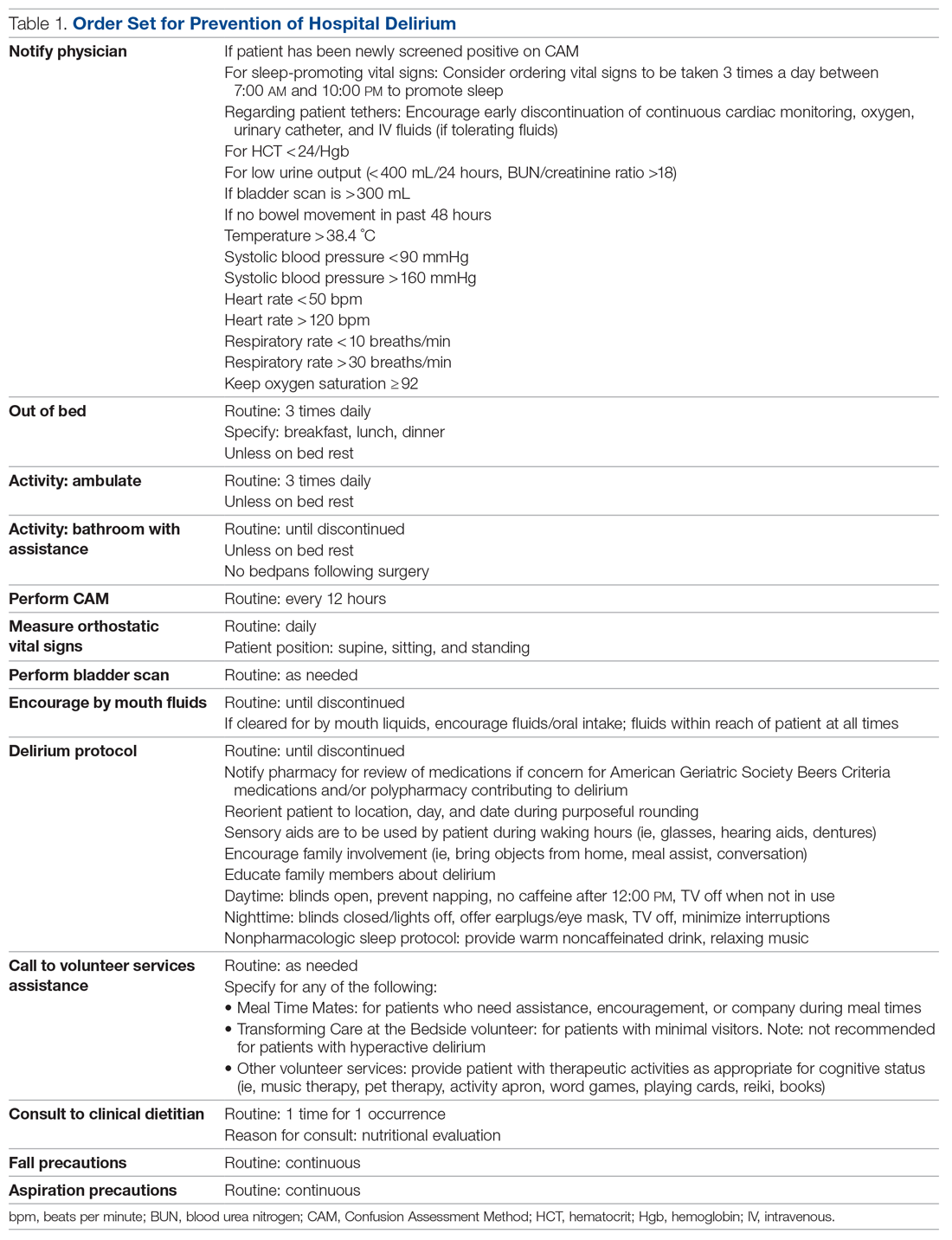

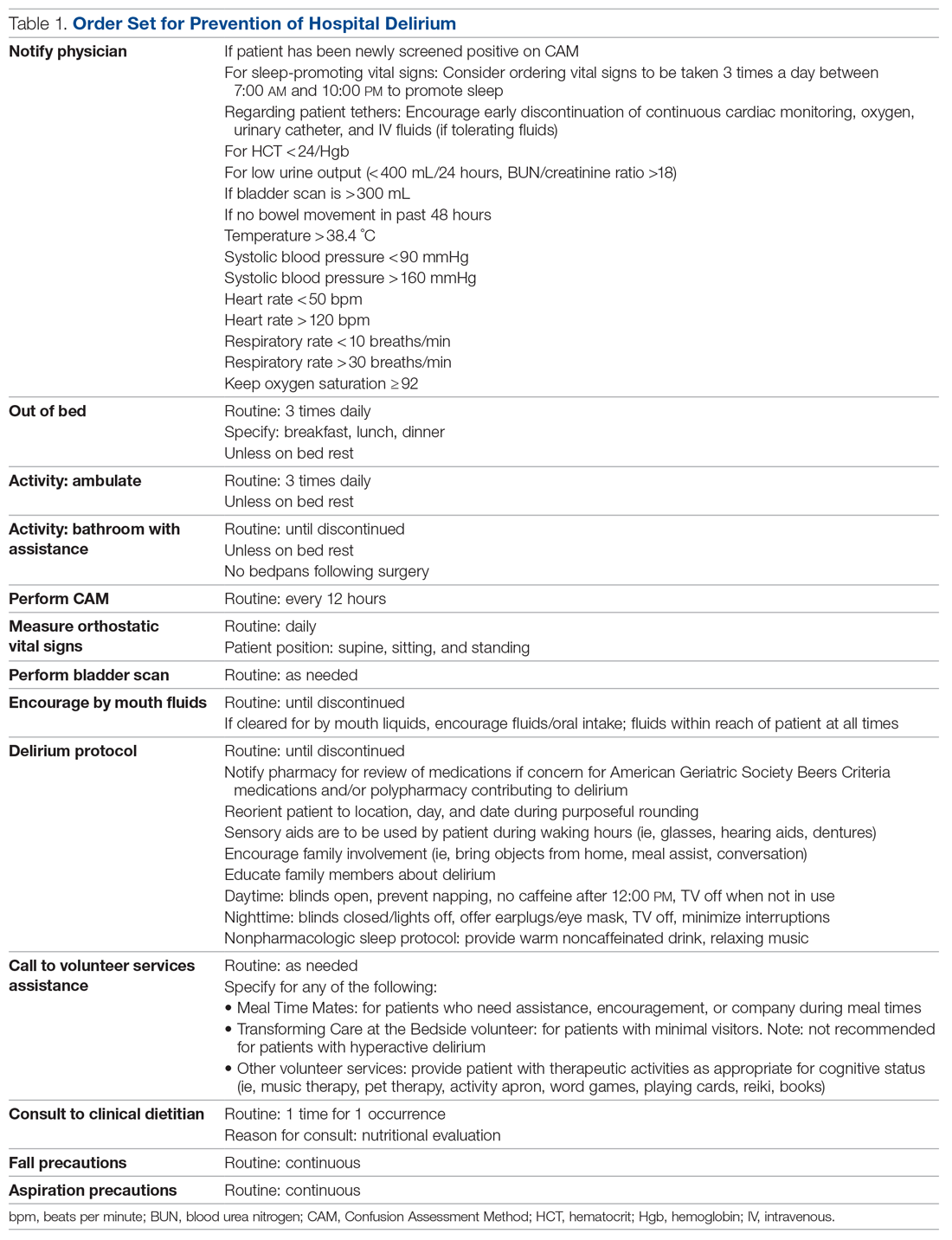

Positive Outcomes Following a Multidisciplinary Approach in the Diagnosis and Prevention of Hospital Delirium

From the Department of Neurology, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Drs. Ching, Darwish, Li, Wong, Simpson, and Funk), the Department of Anesthesia, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Keith Siegel), and the Department of Psychiatry, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Bamgbose).

Objectives: To reduce the incidence and duration of delirium among patients in a hospital ward through standardized delirium screening tools and nonpharmacologic interventions. To advance nursing-focused education on delirium-prevention strategies. To measure the efficacy of the interventions with the aim of reproducing best practices.

Background: Delirium is associated with poor patient outcomes but may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients.

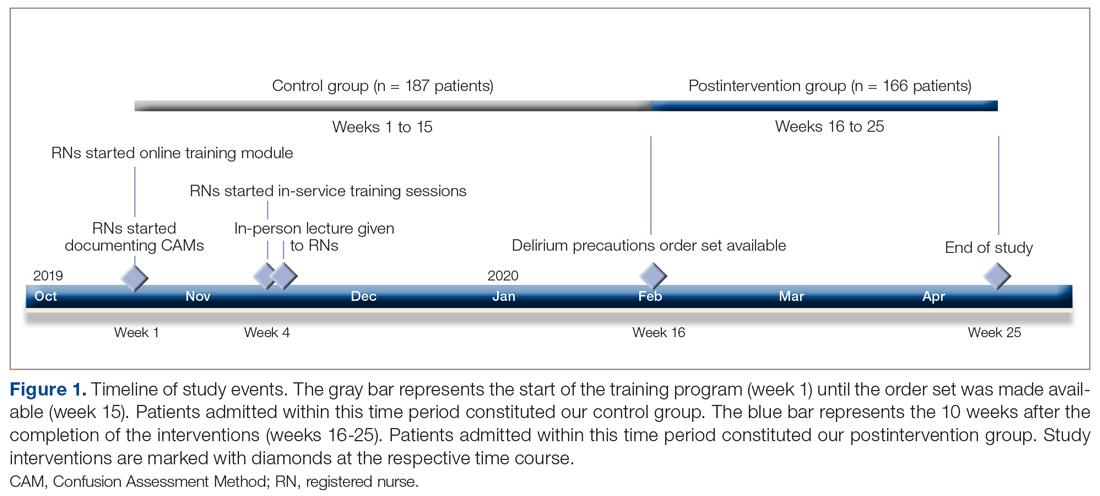

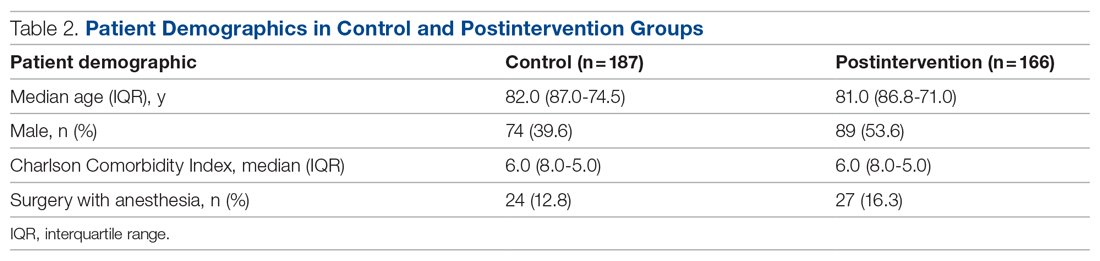

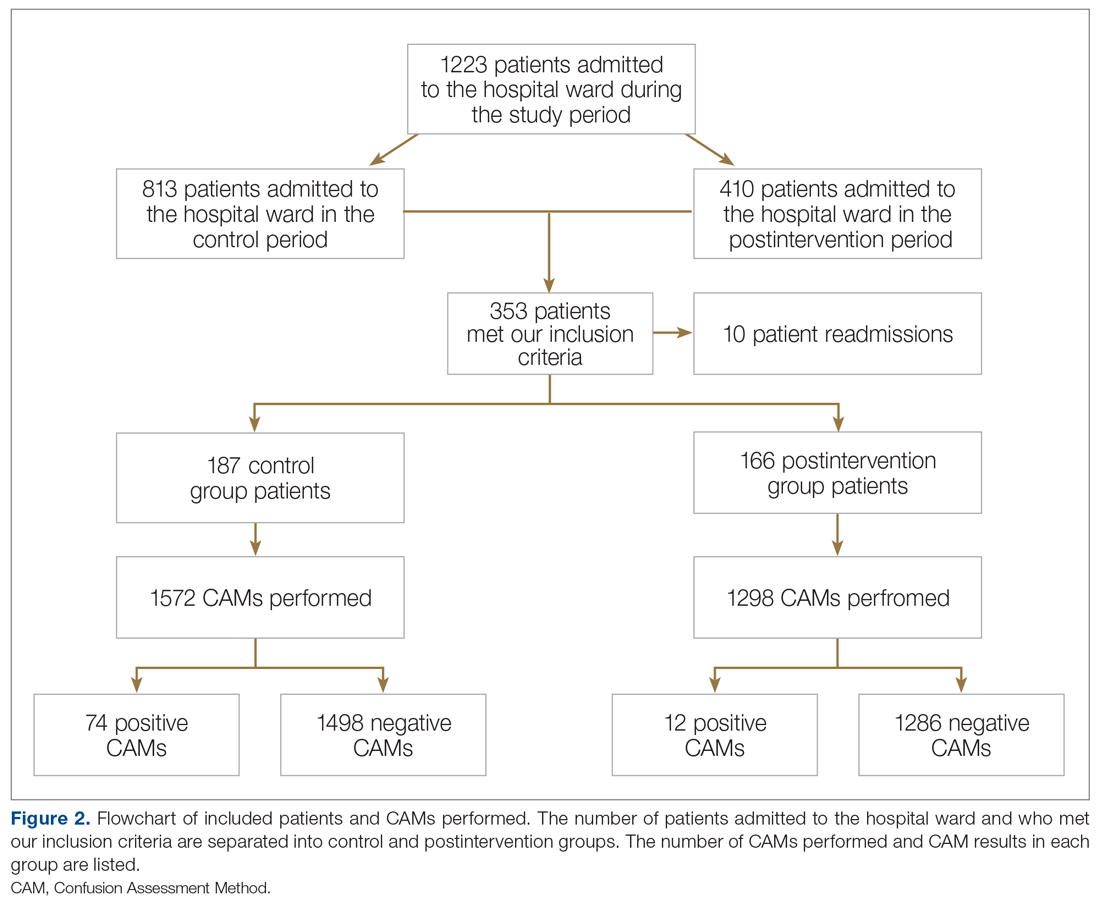

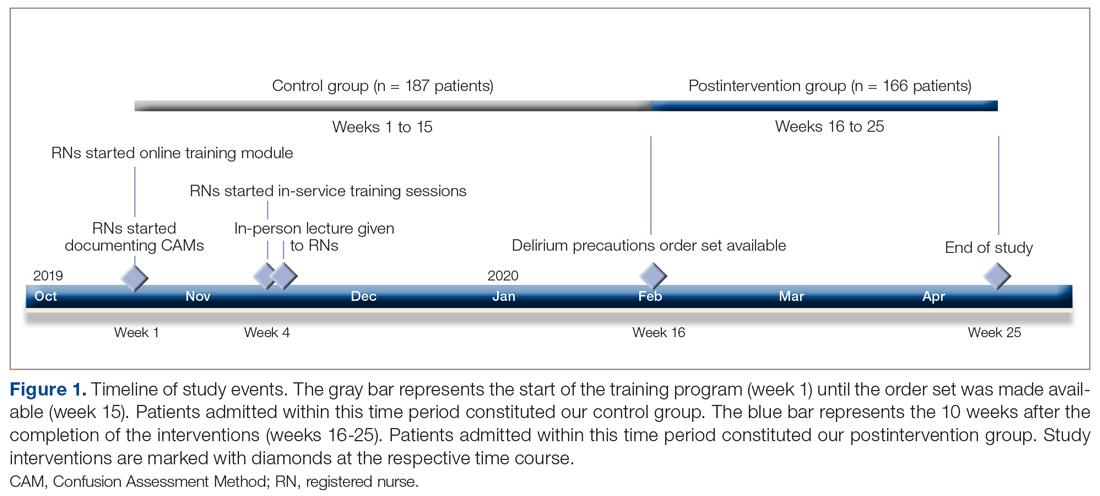

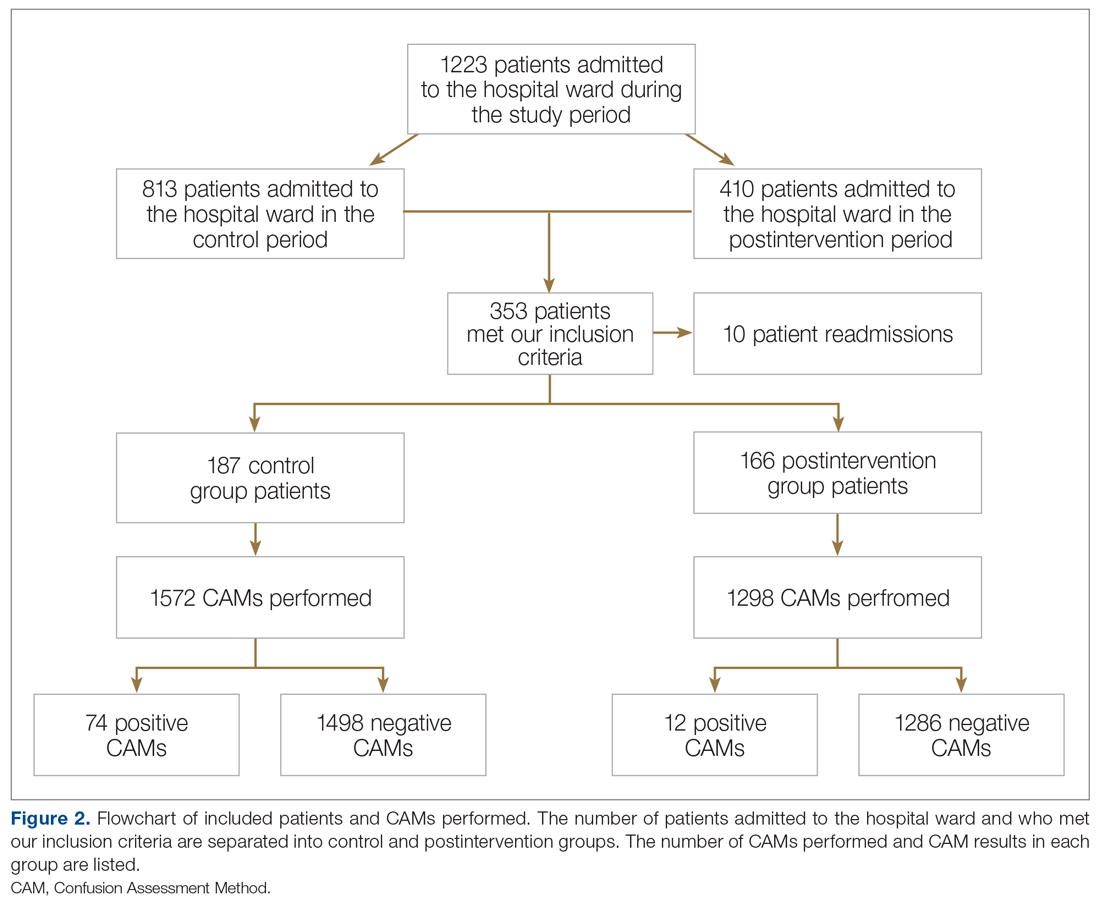

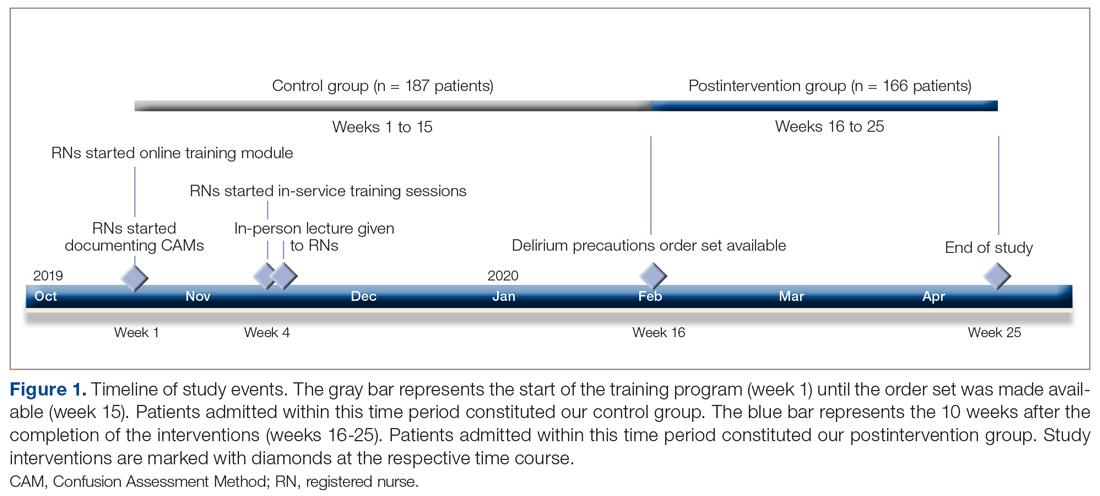

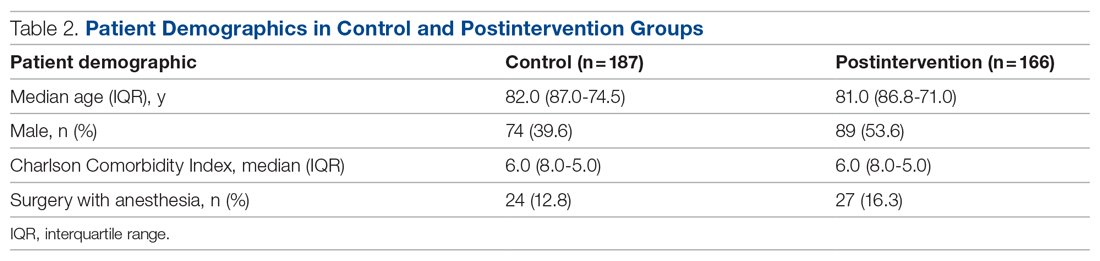

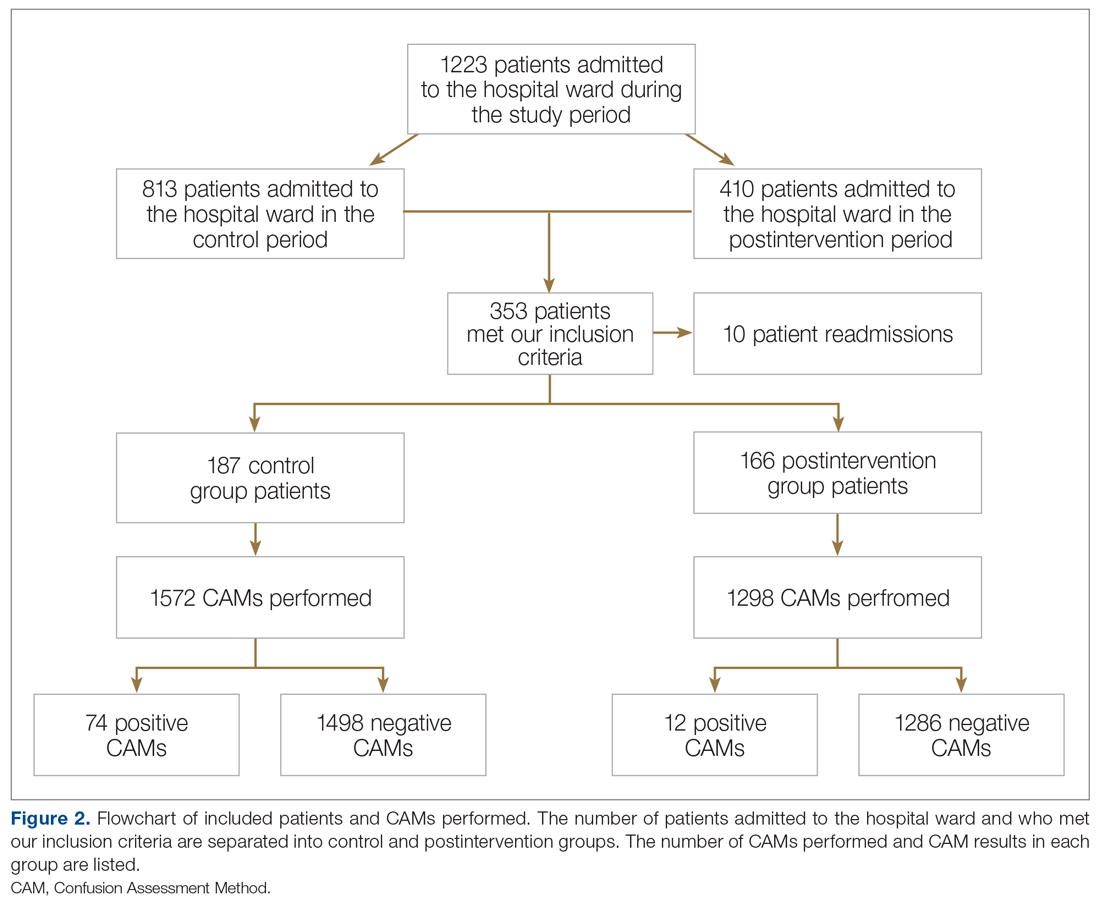

Methods: Following nursing-focused education to prevent delirium, we prospectively evaluated patient care outcomes in a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period. All patients who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria (N = 353). Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence guidelines were adhered to.

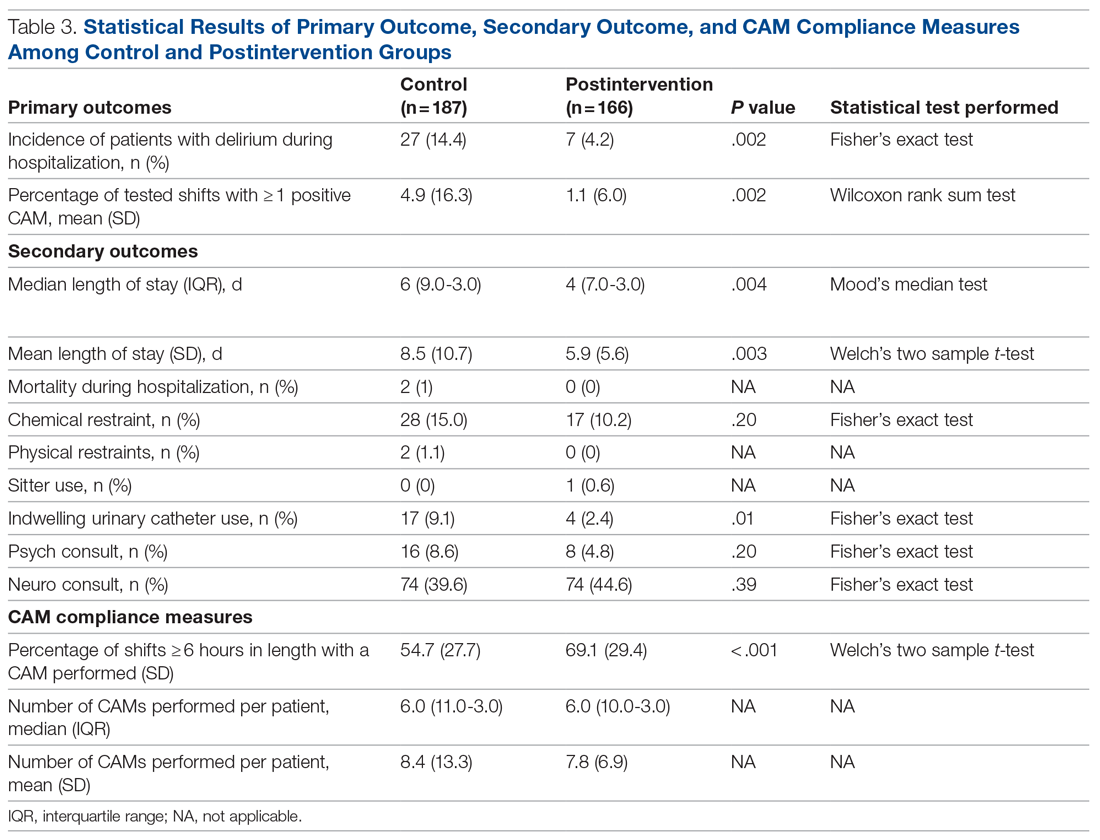

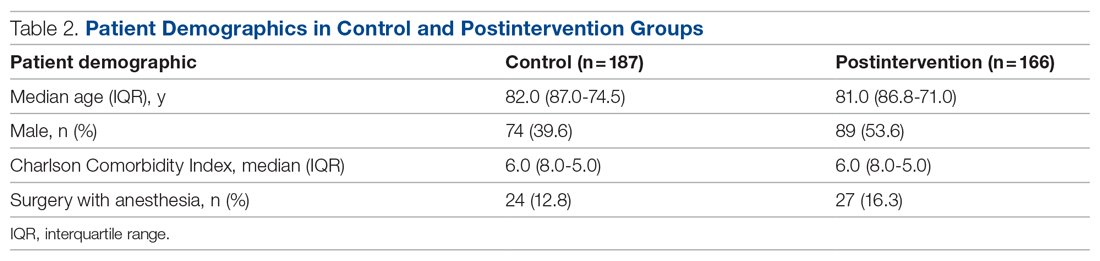

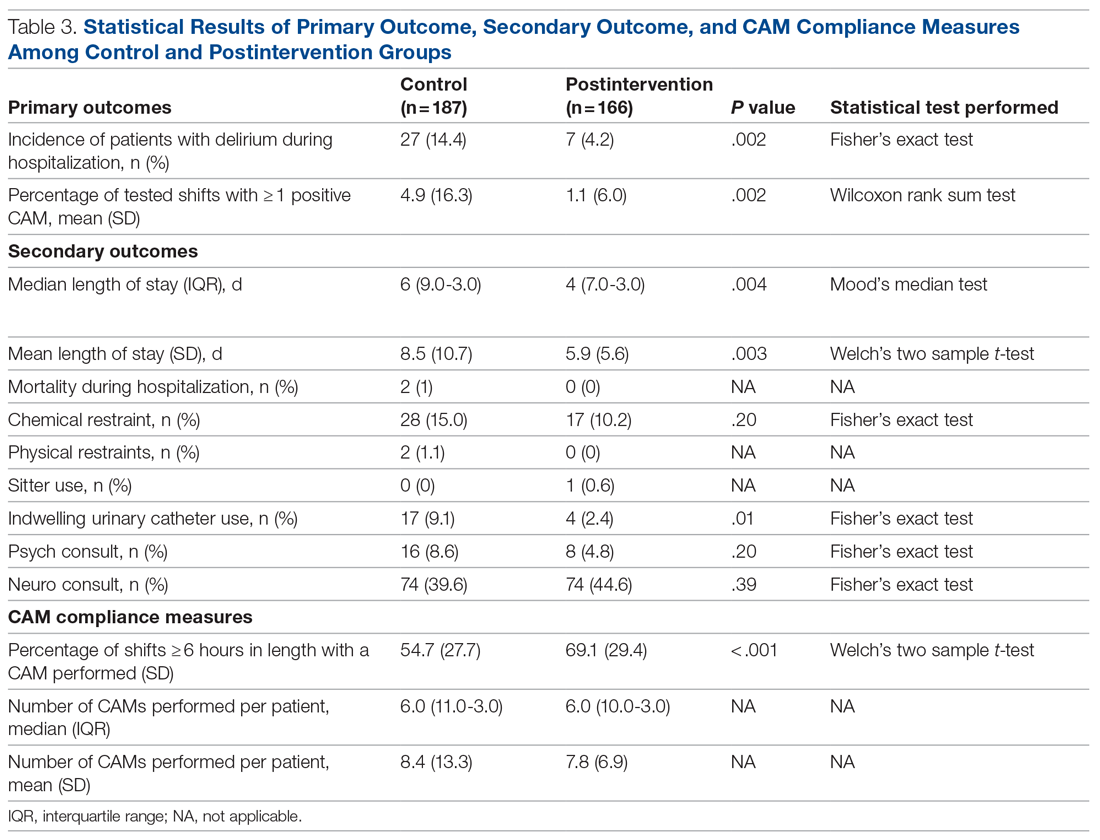

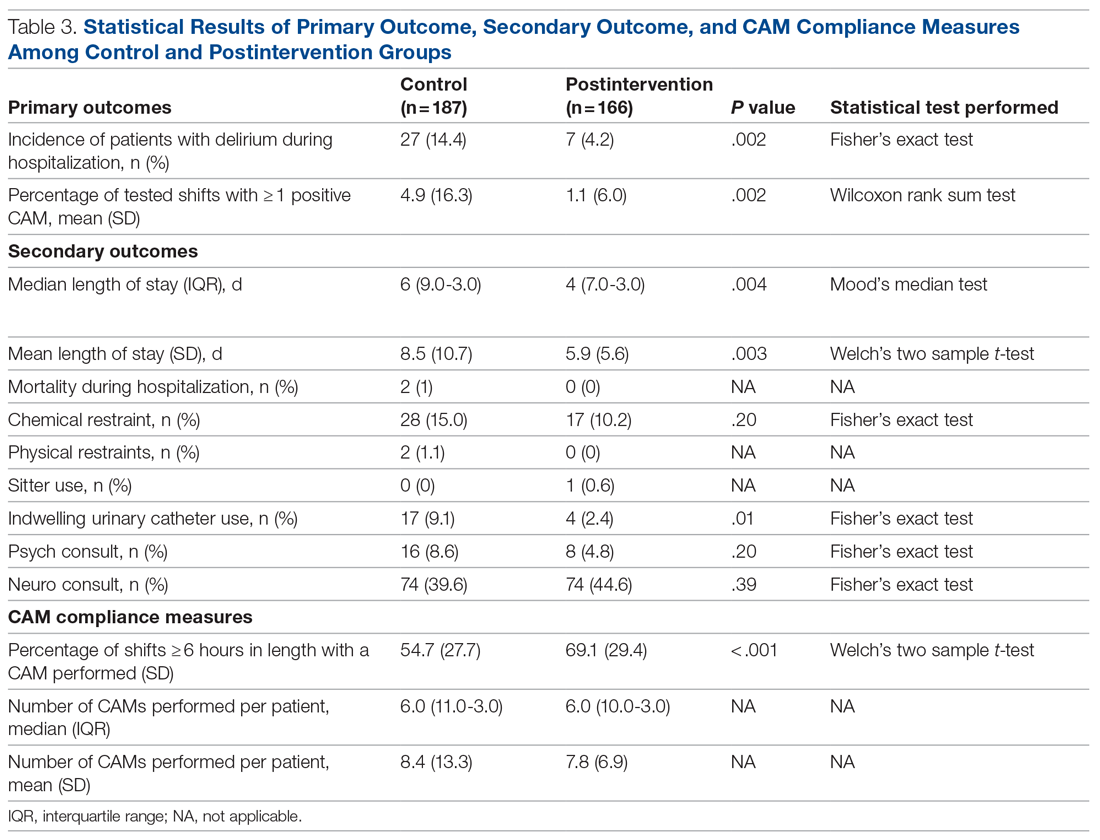

Results: There were 187 patients in the control group, and 166 in the postintervention group. Compared to the control group, the postintervention group had a significant decrease in the incidence of delirium during hospitalization (14.4% vs 4.2%) and a significant decrease in the mean percentage of tested nursing shifts with 1 or more positive CAM (4.9% vs 1.1%). Significant differences in secondary outcomes between the control and postintervention groups included median length of stay (6 days vs 4 days), mean length of stay (8.5 days vs 5.9 days), and use of an indwelling urinary catheter (9.1% vs 2.4%).

Conclusion: A multimodal strategy involving nursing-focused training and nonpharmacologic interventions to address hospital delirium is associated with improved patient care outcomes and nursing confidence. Nurses play an integral role in the early recognition and prevention of hospital delirium, which directly translates to reducing burdens in both patient functionality and health care costs.

Delirium is a disorder characterized by inattention and acute changes in cognition. It is defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a disturbance in attention, awareness, and cognition over hours to a few days that is not better explained by a preexisting, established, or other evolving neurocognitive disorder.1 Delirium is common yet often under-recognized among hospitalized patients, particularly in the elderly. The incidence of delirium in elderly patients on admission is estimated to be 11% to 25%, and an additional 29% to 31% of elderly patients will develop delirium during the hospitalization.2 Delirium costs the health care system an estimated $38 billion to $152 billion per year.3 It is associated with negative outcomes, such as increased new placements to nursing homes, increased mortality, increased risk of dementia, and further cognitive deterioration among patients with dementia.4-6

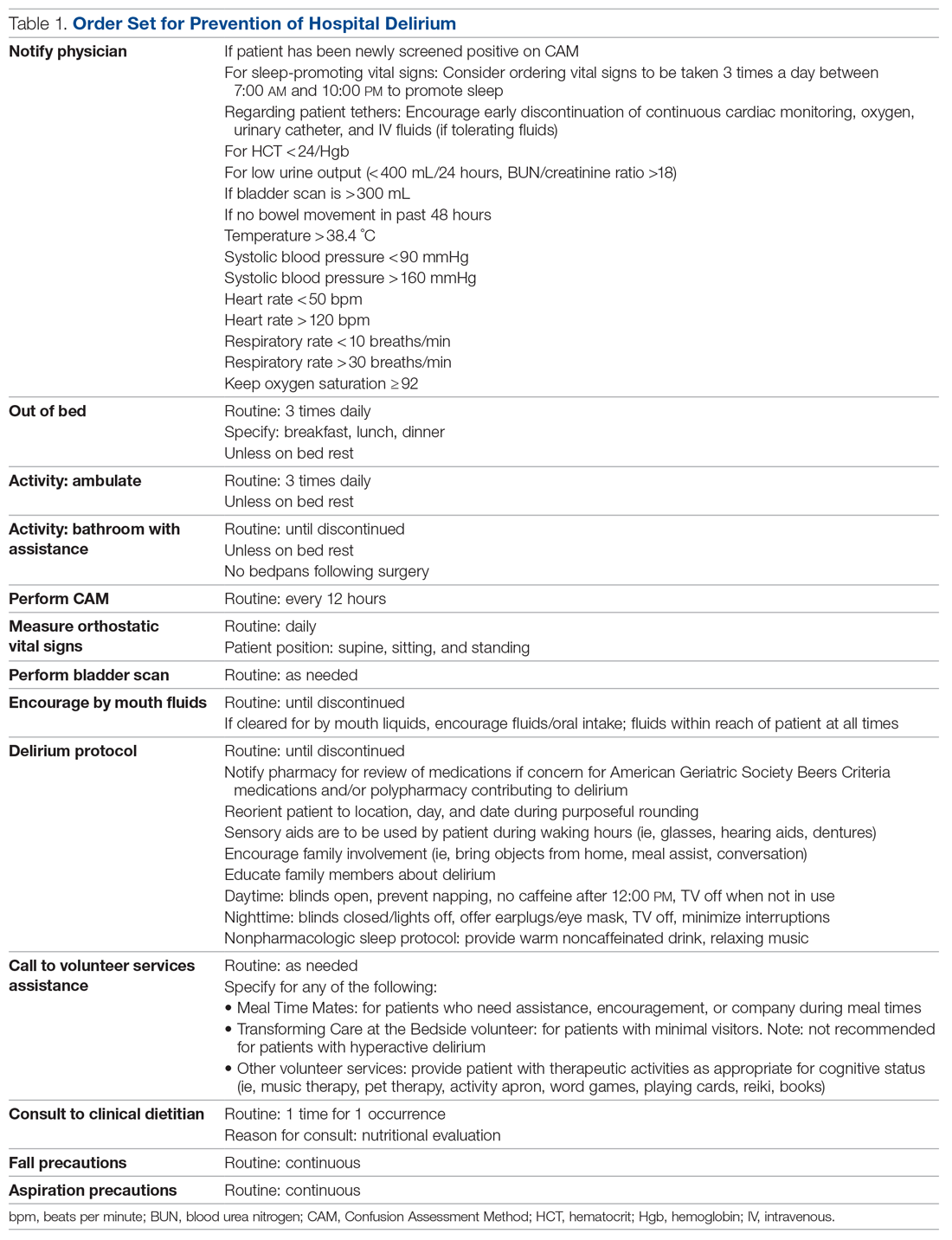

Despite its prevalence, delirium may be preventable in a significant percentage of hospitalized patients. Targeted intervention strategies, such as frequent reorientation, maximizing sleep, early mobilization, restricting use of psychoactive medications, and addressing hearing or vision impairment, have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of hospital delirium.7,8 To achieve these goals, we explored the use of a multimodal strategy centered on nursing education. We integrated consistent, standardized delirium screening and nonpharmacologic interventions as part of a preventative protocol to reduce the incidence of delirium in the hospital ward.

Methods

We evaluated a consecutive series of patients who were admitted to a designated hospital medical-surgical ward within a 25-week period between October 2019 and April 2020. All patients during this period who had at least 1 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) documented by a nurse during hospitalization met our inclusion criteria. Patients who did not have a CAM documented were excluded from the analysis. Delirium was defined according to the CAM diagnostic algorithm.9

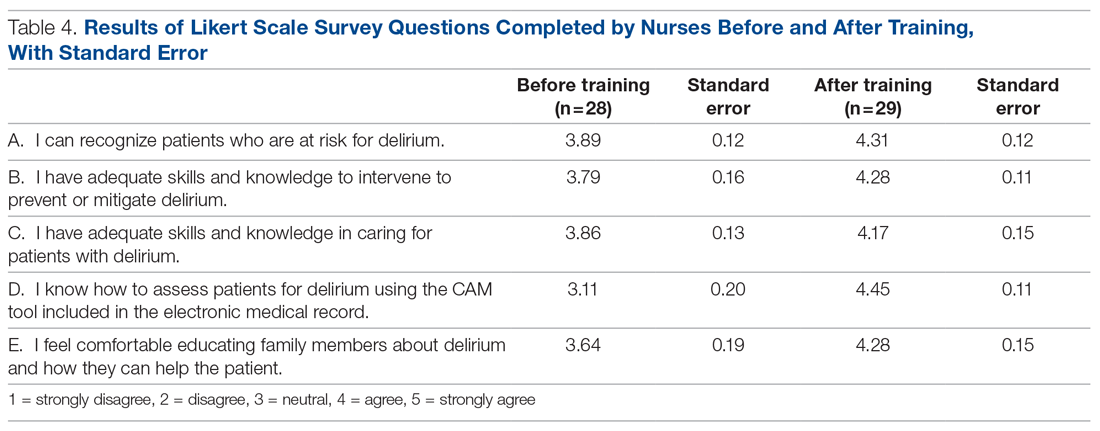

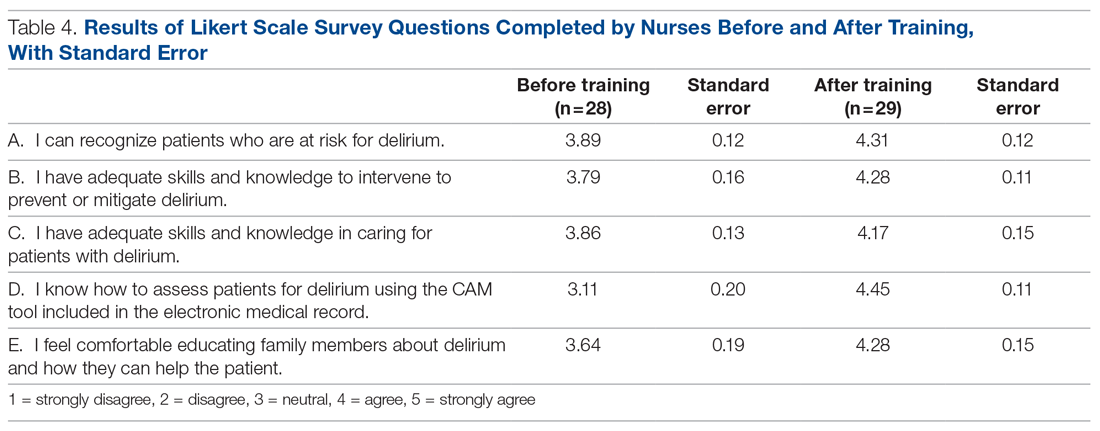

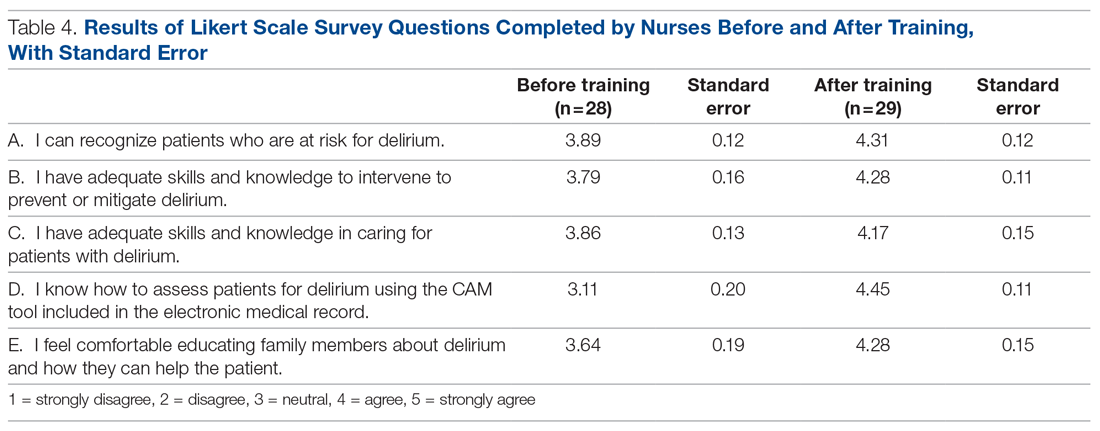

Core nursing staff regularly assigned to the ward completed a multimodal training program designed to improve recognition, documentation, and prevention of hospital delirium. Prior to the training, the nurses completed a 5-point Likert scale survey assessing their level of confidence with recognizing delirium risk factors, preventing delirium, addressing delirium, utilizing the CAM tool, and educating others about delirium. Nurses completed the same survey after the study period ended.