User login

Light Brown and Pink Macule on the Upper Arm

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

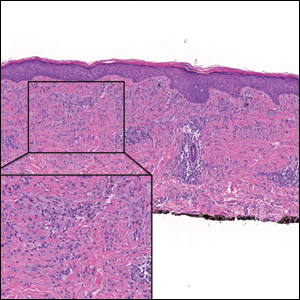

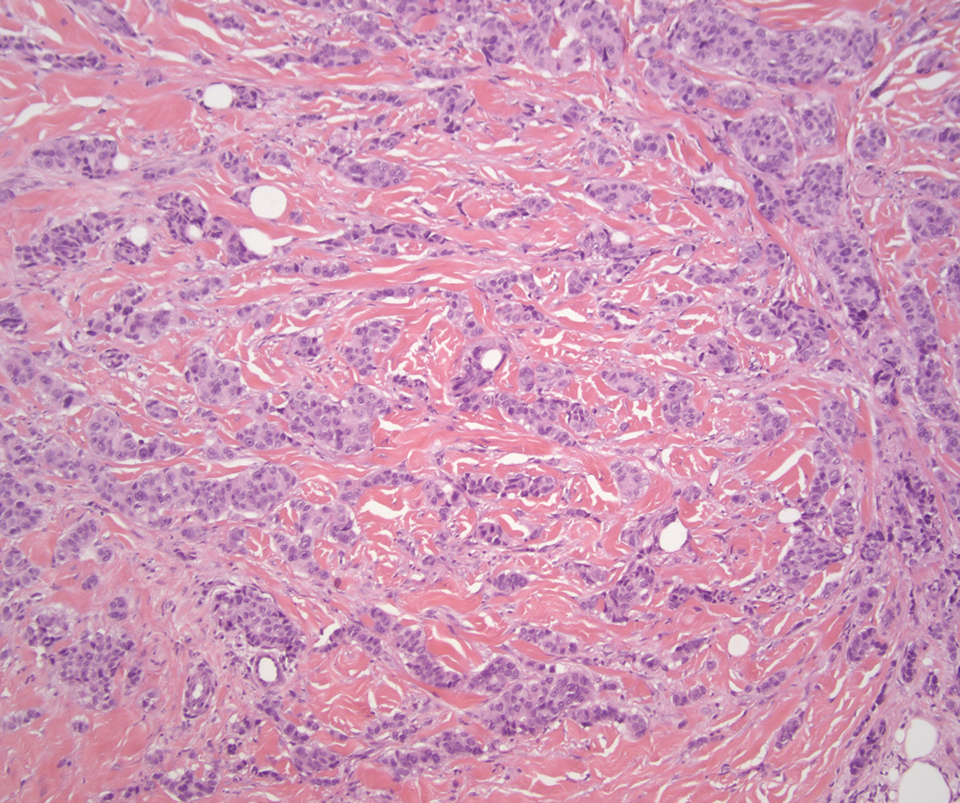

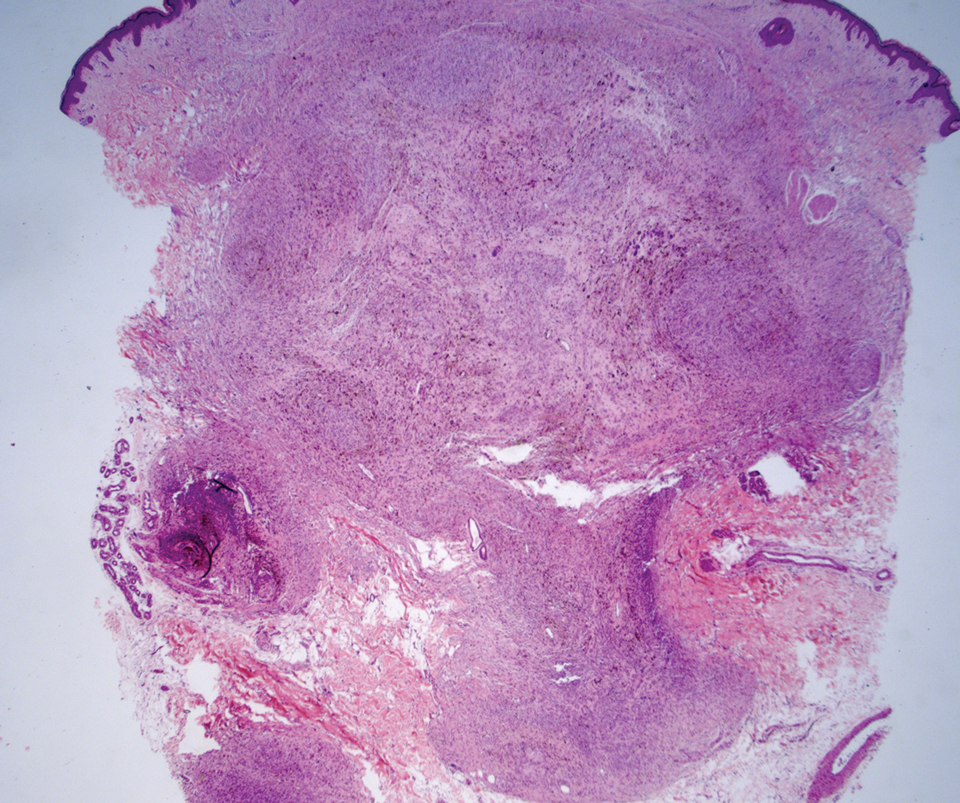

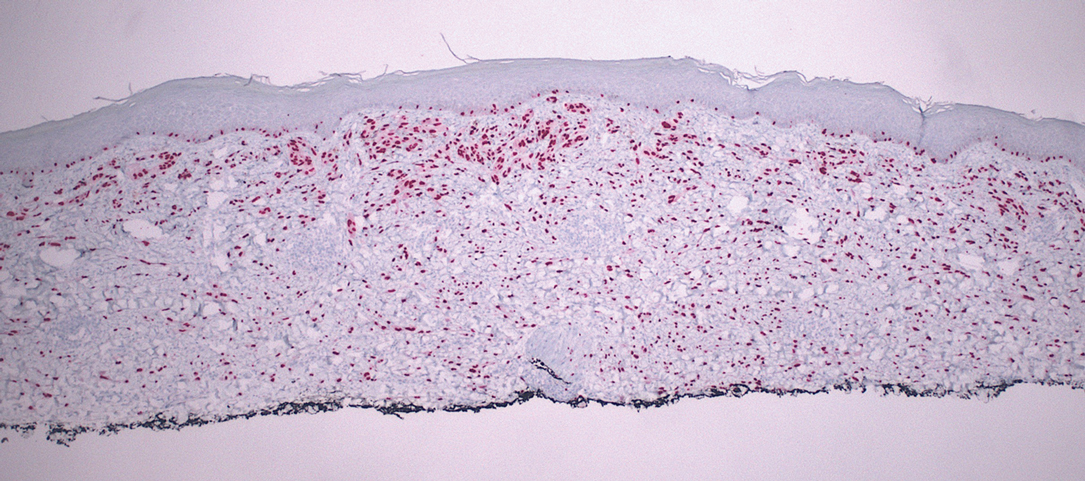

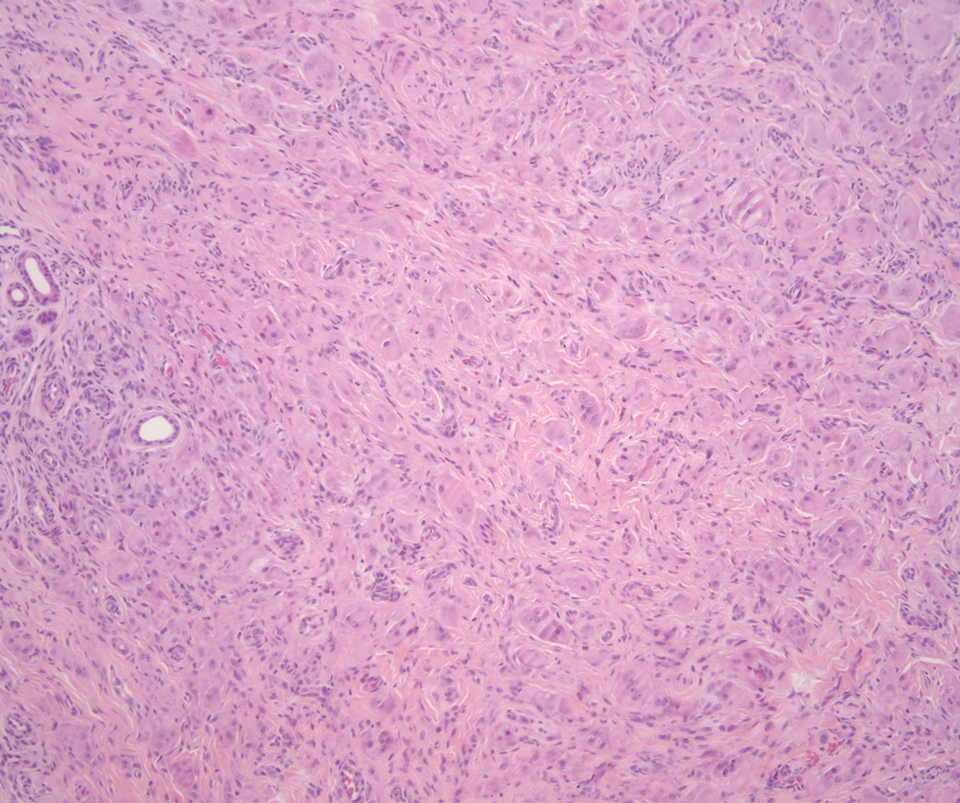

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

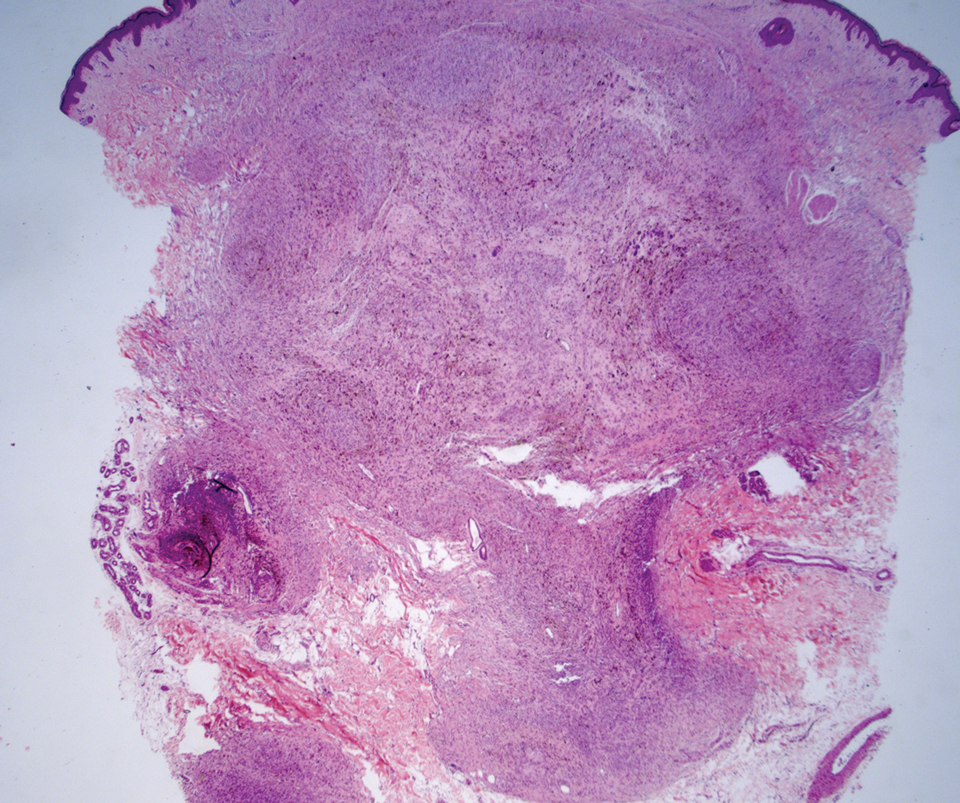

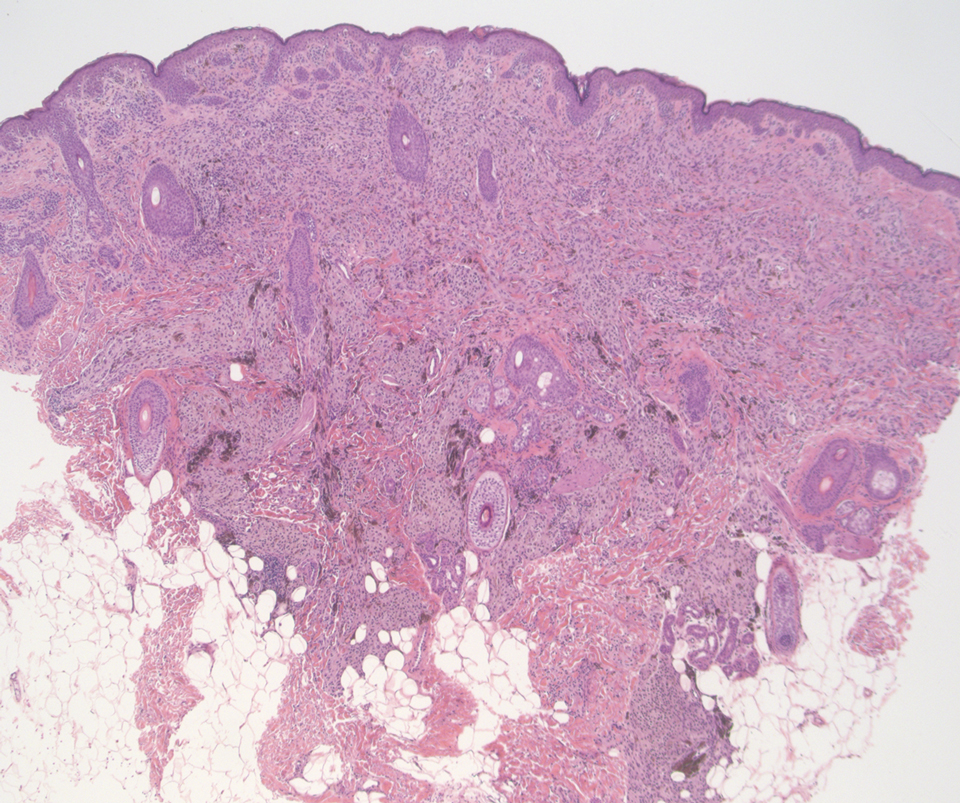

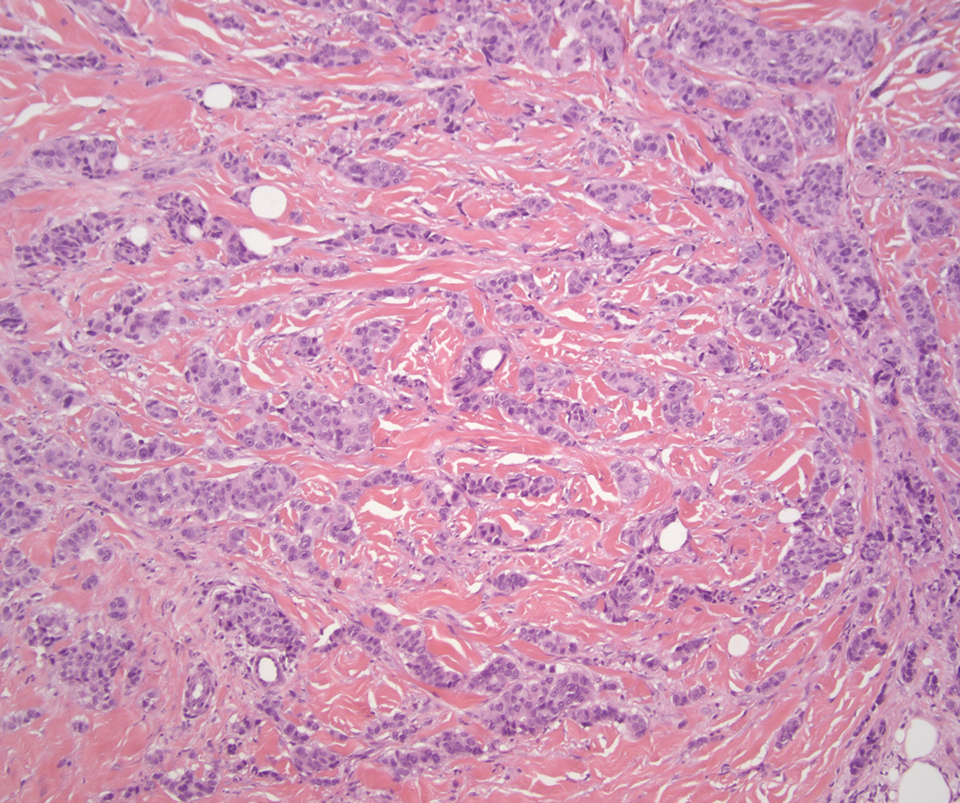

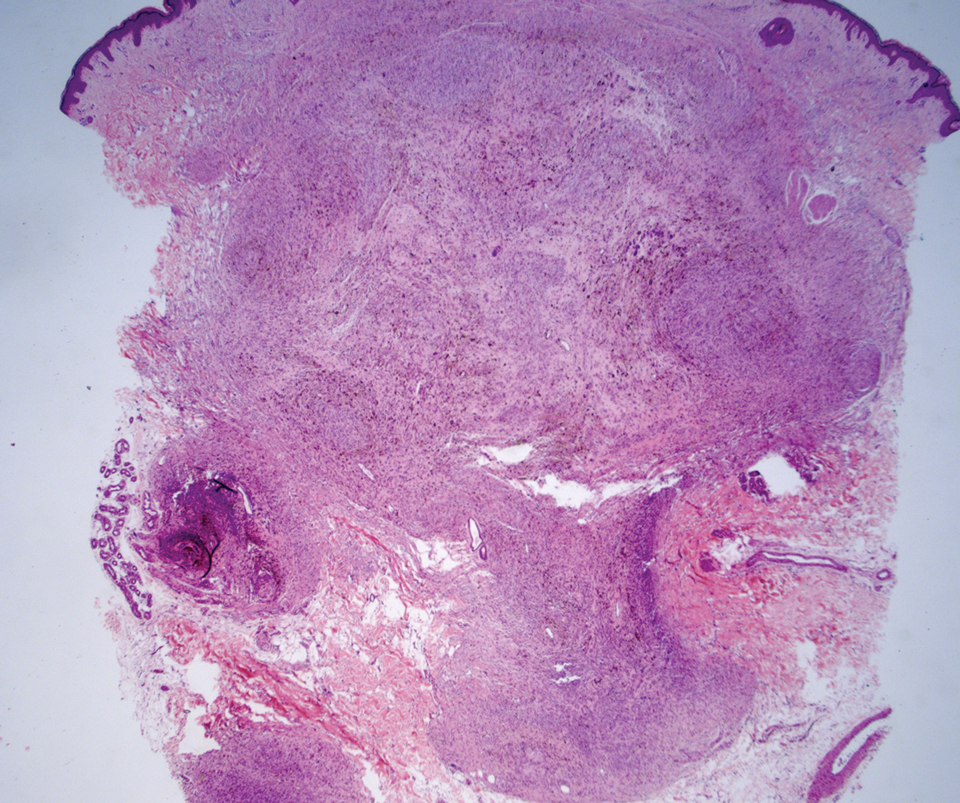

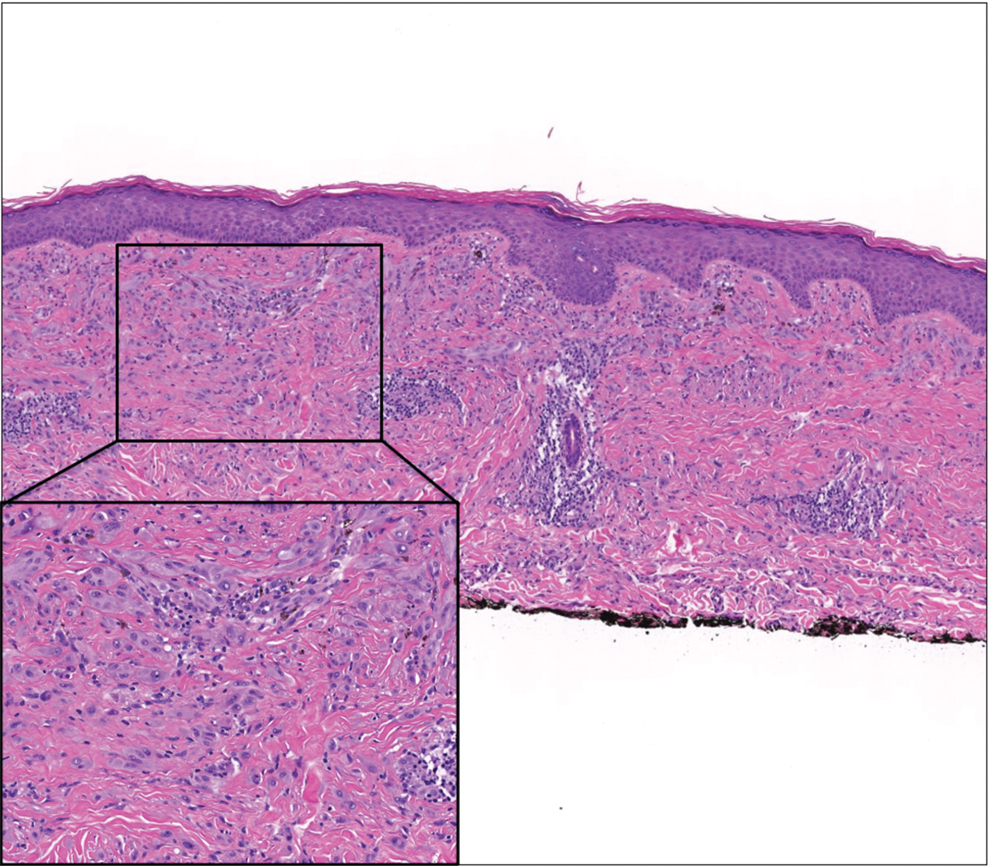

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

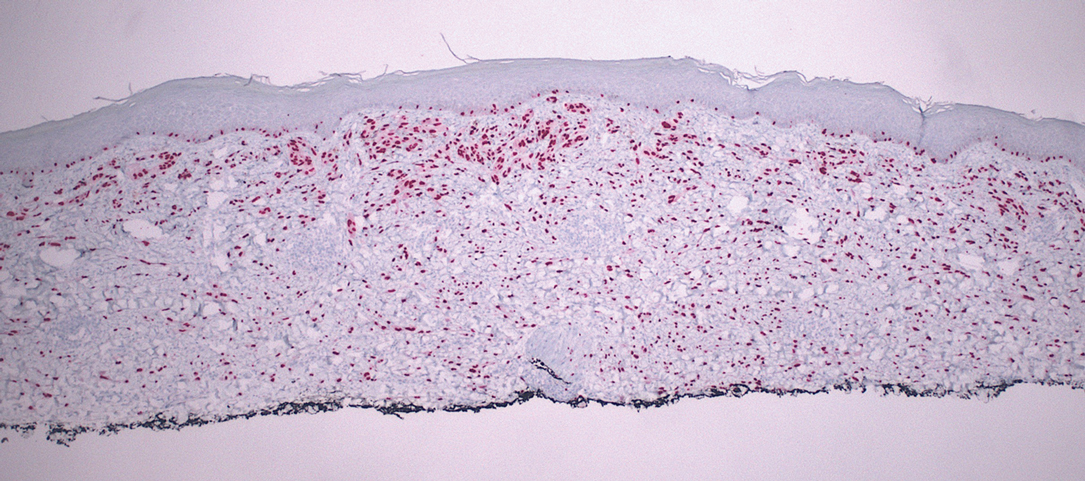

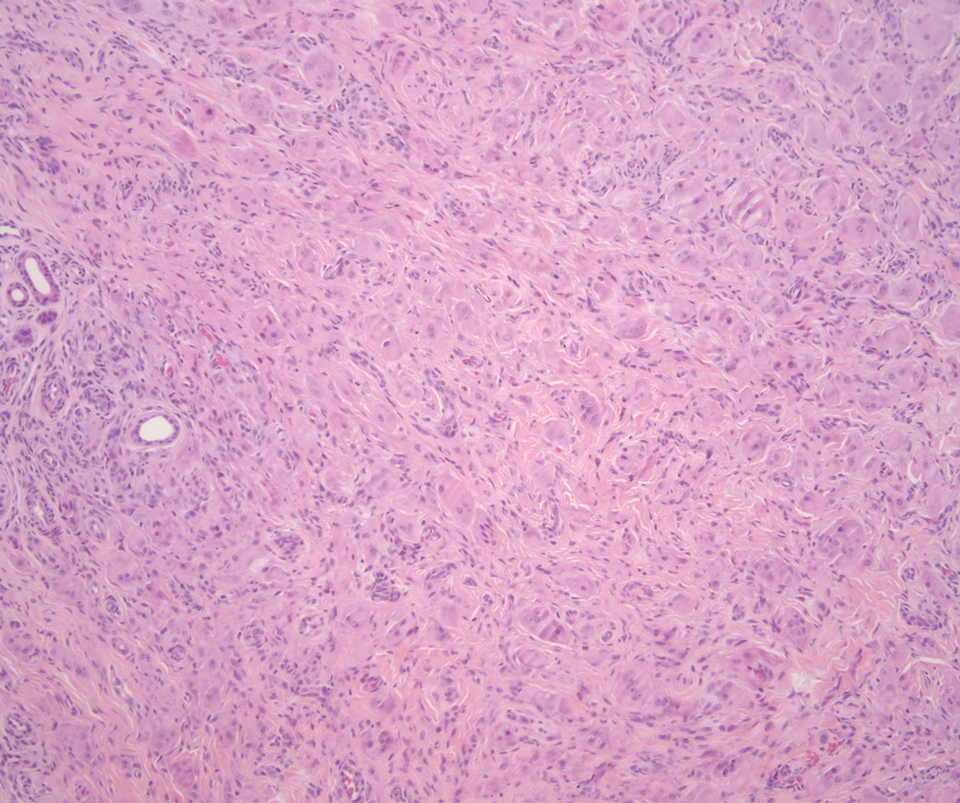

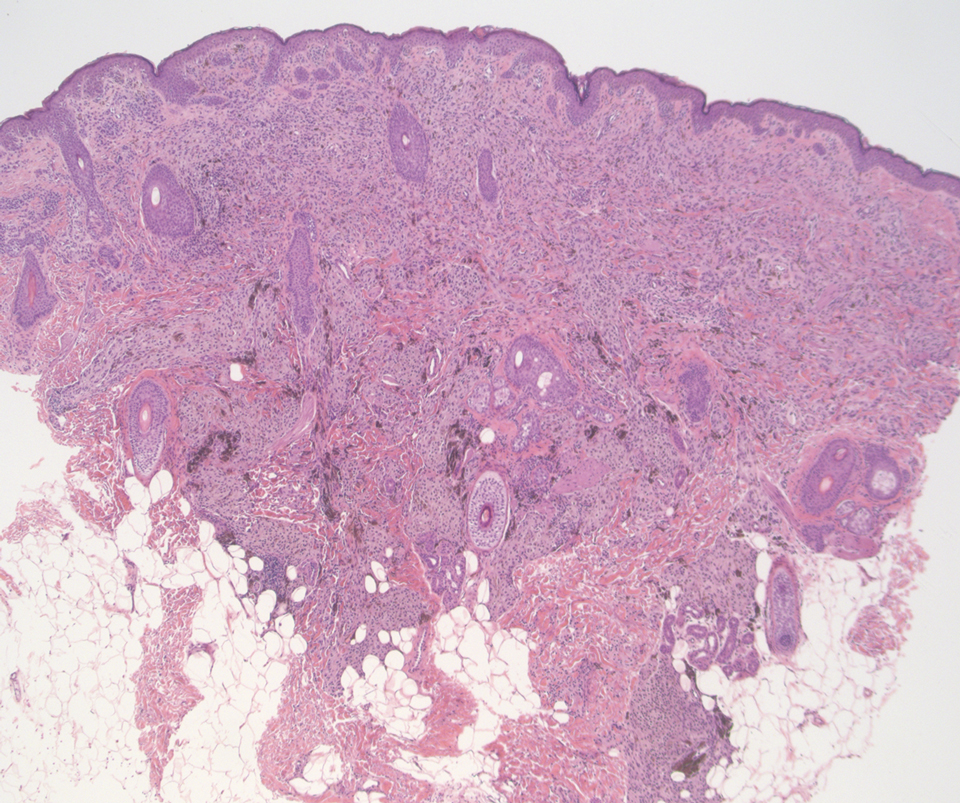

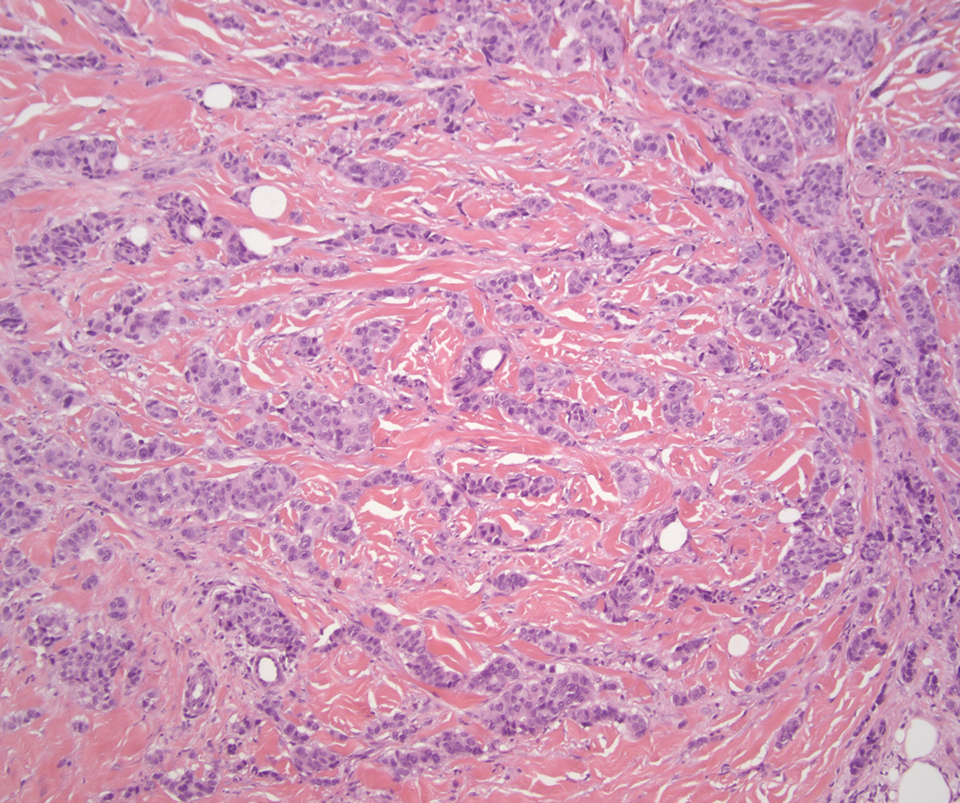

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

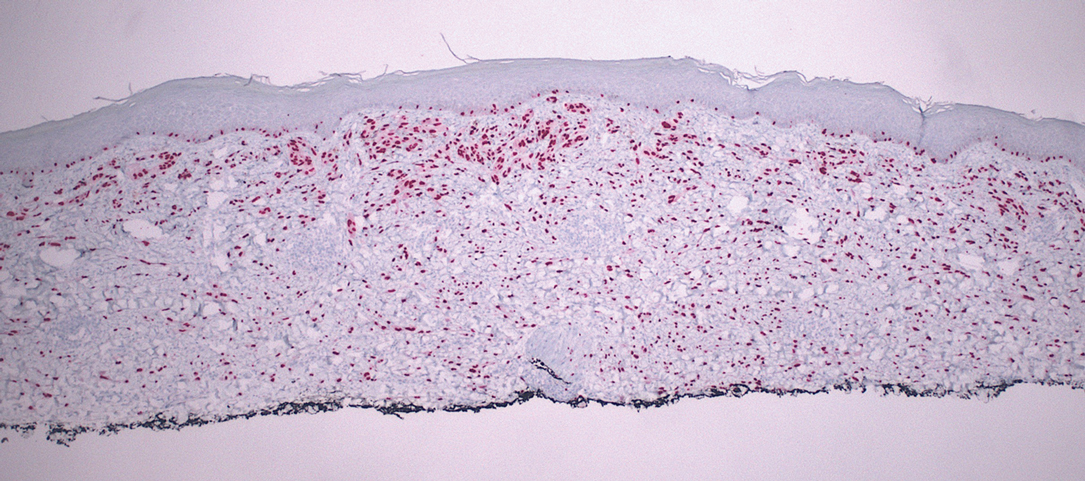

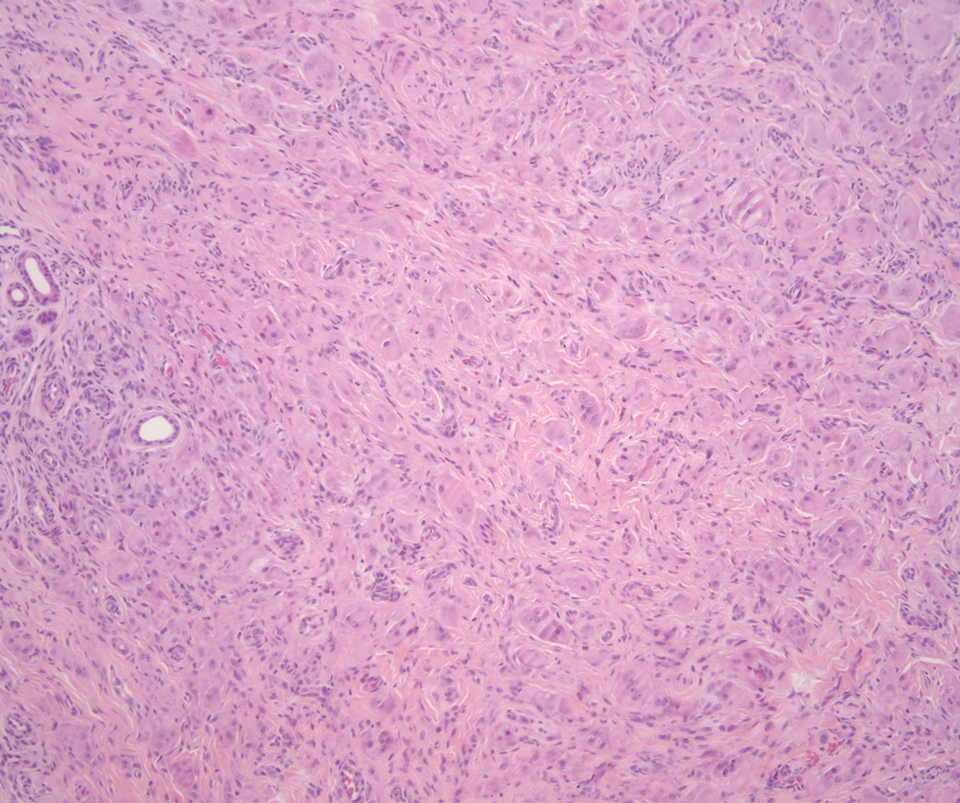

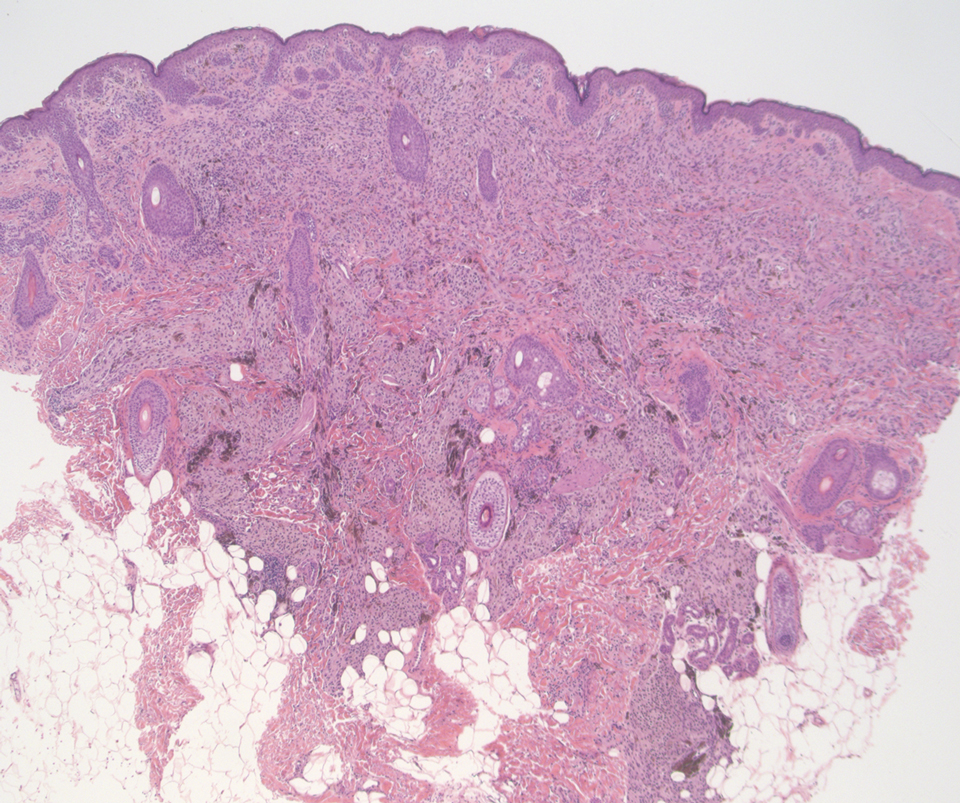

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

The Diagnosis: Desmoplastic Spitz Nevus

Desmoplastic Spitz nevus is a rare variant of Spitz nevus that commonly presents as a red to brown papule on the head, neck, or extremities. It is pertinent to review the histologic features of this neoplasm, as it can be confused with other more sinister entities such as spitzoid melanoma. Histologically, there is a dermal infiltrate of melanocytes containing eosinophilic cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. Junctional involvement is rare, and there should be no pagetoid spread.1 This entity features abundant stromal fibrosis formed by dense collagen bundles, low cellular density, and polygonal-shaped melanocytes, which helps to differentiate it from melanoma.2,3 In a retrospective study comparing the characteristics of desmoplastic Spitz nevi with desmoplastic melanoma, desmoplastic Spitz nevi histologically were more symmetric and circumscribed with greater melanocytic maturation and adnexal structure involvement.3 Although this entity demonstrates maturation from the superficial to the deep dermis, it also may feature deep dermal vascular proliferation.4 S-100 and SRY-related HMG box 10, SOX-10, are noted to be positive in desmoplastic Spitz nevi, which can help to differentiate it from nonmelanocytic entities (Figure 1).

Although spitzoid lesions can be ambiguous and difficult even for experts to classify, spitzoid melanoma tends to have a high Breslow thickness, high cell density, marked atypia, and an increased nucleus to cytoplasm ratio.5 Additionally, desmoplastic melanoma was found to more often display “melanocytic junctional nests associated with discohesive cells, variations in size and shape of the nests, lentiginous melanocytic proliferation, actinic elastosis, pagetoid spread, dermal mitosis, perineural involvement and brisk inflammatory infiltrate.”3 Given the challenge of histologically separating desmoplastic Spitz nevi from melanoma, immunostaining can be useful. For example, Hilliard et al6 used a p16 antibody to differentiate desmoplastic Spitz nevi from desmoplastic melanoma, finding that most desmoplastic melanomas (81.8%; n=11) were negative for p16, whereas all desmoplastic Spitz nevi were at least moderately positive. However, another study re-evaluated the utility of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma and found that 72.7% (16/22) were at least focally reactive for the immunostain.7 Thus, caution must be exercised when using p16.

PReferentially expressed Antigen in MElanoma (PRAME) is a newer nuclear immunohistochemical marker that tends to be positive in melanomas and negative in nevi. Desmoplastic Spitz nevi would be expected to be negative for PRAME, while desmoplastic melanoma may be positive; however, this marker seems to be less effective in desmoplastic melanoma than in most other subtypes of the malignancy. In one study, only 35% (n=20) of desmoplastic melanomas were positive for PRAME.8 Likewise, another study showed that some benign Spitz nevi may diffusely express PRAME.9 As such, PRAME should be used prudently.

For cases in which immunohistochemistry is equivocal, molecular testing may aid in differentiating Spitz nevi from melanoma. For example, comparative genomic hybridization has revealed an increased copy number of chromosome 11p in approximately 20% of Spitz nevi cases10; this finding is not seen in melanoma. Mutation analyses of HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase, HRAS; B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, BRAF; and NRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase, NRAS, also have shown some promise in distinguishing spitzoid lesions from melanoma, but these analyses may be oversimplified.11 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is another diagnostic modality that has been studied to differentiate benign nevi from melanoma. One study challenged the utility of FISH, reporting 7 of 15 desmoplastic melanomas tested positive compared to 0 of 15 sclerotic melanocytic nevi.12 Thus, negative FISH cannot reliably rule out melanoma. Ultimately, a combination of immunostains along with FISH or another genetic study would prove to be most effective in ruling out melanoma in difficult cases. Even then, a dermatopathologist may be faced with a degree of uncertainty.

Cellular blue nevi predominantly affect adults younger than 40 years and commonly are seen on the buttocks.13 This benign neoplasm demonstrates areas that are distinctly sclerotic as well as those that are cellular in nature.14 This entity demonstrates a well-circumscribed dermal growth pattern with 2 main populations of cells. The sclerotic portion of the cellular blue nevus mimics that of the blue nevus in that it is noted superficially with irregular margins. The cellular aspect of the nevus features spindle cells contained within well-circumscribed nodules (Figure 2). Stromal melanophages are not uncommon, and some can be observed adjacent to nerve fibers. Although this blue nevus variant displays features of the common blue nevus, its melanocytes track along adnexal and neurovascular structures similar to the deep penetrating nevus and the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. However, these melanocytes are variable in morphology and can appear on a spectrum spanning from pale and lightly pigmented to clear.15

The breast is the most common site of origin of tumor metastasis to the skin. These cutaneous metastases can vary in both their clinical and histological presentations. For example, cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma often can present clinically as pink-violaceous papules and plaques on the breast or on other parts of the body. Histologically, it can demonstrate a varying degree of patterns such as collagen infiltration by single cells, cords, tubules, and sheets of atypical cells (Figure 3) that can be observed together in areas of mucin or can form glandular structures.16 Metastatic breast carcinoma is noted to be positive for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, estrogen receptor, and cytokeratin 7, which can help differentiate this entity from other tumors of glandular origin.16 Although rare, primary melanoma of the breast has been reported in the literature.17,18 These malignant melanocytic lesions easily could be differentiated from other breast tumors such as adenocarcinoma using immunohistochemical staining patterns.

Deep penetrating nevi most often are observed clinically as blue, brown, or black papules or nodules on the head or neck.19 Histologically, this lesion features a wedge-shaped infiltrate of deep dermal melanocytes with oval nuclei. It commonly extends to the reticular dermis or further into the subcutis (Figure 4).20,21 This neoplasm frequently tracks along adnexal and neurovascular structures, resulting in a plexiform appearance.22 The adnexal involvement of deep penetrating nevi is a shared feature with desmoplastic Spitz nevi. The presence of any number of melanophages is characteristic of this lesion.23 Lastly, there is a well-documented association between β-catenin mutations and deep penetrating nevi.24 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is a rare form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis that has the pathognomonic clinical finding of pink-red papules (coral beading) with a predilection for acral surfaces. Histology of affected skin reveals a dermal infiltrate of ground glass as well as eosinophilic histiocytes that most often stain positive for CD68 and human alveolar macrophage 56 but negative for S-100 and CD1a (Figure 5).25 Although MRH is rare, negative staining for S-100 could serve as a useful diagnostic clue to differentiate it from other entities that are positive for S-100, such as the desmoplastic Spitz nevus. Arthritis mutilans is a potential complication of MRH, but a reported association with an underlying malignancy is seen in approximately 25% of cases.26 Thus, the cutaneous, rheumatologic, and oncologic implications of this disease help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses that may be considered.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

- Luzar B, Bastian BC, North JP, et al. Melanocytic nevi. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1275-1280.

- Busam KJ, Gerami P. Spitz nevi. In: Busam KJ, Gerami P, Scolyer RA, eds. Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:37-60.

- Nojavan H, Cribier B, Mehregan DR. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus: a histopathological review and comparison with desmoplastic melanoma [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2009;136:689-695.

- Tomizawa K. Desmoplastic Spitz nevus showing vascular proliferation more prominently in the deep portion. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:184-185.

- Requena C, Botella R, Nagore E, et al. Characteristics of spitzoid melanoma and clues for differential diagnosis with Spitz nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:478-486.

- Hilliard NJ, Krahl D, Sellheyer K. p16 expression differentiates between desmoplastic Spitz nevus and desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:753-759.

- Blokhin E, Pulitzer M, Busam KJ. Immunohistochemical expression of p16 in desmoplastic melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:796-800.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131.

- Bauer J, Bastian BC. DNA copy number changes in the diagnosis of melanocytic tumors [in German]. Pathologe. 2007;28:464-473.

- Luo S, Sepehr A, Tsao H. Spitz nevi and other spitzoid lesions part I. background and diagnoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1073-1084.

- Gerami P, Beilfuss B, Haghighat Z, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization as an ancillary method for the distinction of desmoplastic melanomas from sclerosing melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:329-334.

- Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:401-415.

- Rodriguez HA, Ackerman LV. Cellular blue nevus. clinicopathologic study of forty-five cases. Cancer. 1968;21:393-405.

- Phadke PA, Zembowicz A. Blue nevi and related tumors. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:345-358.

- Ko CJ. Metastatic tumors and simulators. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier Limited; 2019:496-504.

- Drueppel D, Schultheis B, Solass W, et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the breast: case report and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:1709-1713.

- Kurul S, Tas¸ F, Büyükbabani N, et al. Different manifestations of malignant melanoma in the breast: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:202-206.

- Strazzula L, Senna MM, Yasuda M, et al. The deep penetrating nevus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1234-1240.

- Mehregan DA, Mehregan AH. Deep penetrating nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:328-331.

- Robson A, Morley-Quante M, Hempel H, et al. Deep penetrating naevus: clinicopathological study of 31 cases with further delineation of histological features allowing distinction from other pigmented benign melanocytic lesions and melanoma. Histopathology. 2003;43:529-537.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Deep penetrating nevus: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:321-326.

- Cooper PH. Deep penetrating (plexiform spindle cell) nevus. a frequent participant in combined nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:172-180.

- de la Fouchardière A, Caillot C, Jacquemus J, et al. β-Catenin nuclear expression discriminates deep penetrating nevi from other cutaneous melanocytic tumors. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:539-550.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Selmi C, Greenspan A, Huntley A, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a critical review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:511.

A 37-year-old woman with a history of fibrocystic breast disease and a family history of breast cancer presented with a light brown macule on the right upper arm of 10 years’ duration. The patient first noticed this macule 10 years prior; however, within the last 4 months she noticed a small amount of homogenous darkening and occasional pruritus. Physical examination revealed a 4.0-mm, light brown and pink macule on the right upper arm. Dermoscopy showed a homogenous pigment network with reticular lines and branched streaks centrally. No crystalline structures, milky red globules, or pseudopods were appreciated. A tangential shave biopsy was obtained and submitted for hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Motor function restored in three men after complete paralysis from spinal cord injury

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

The Final Rule for 2022: What’s New and How Changes in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and Quality Payment Program Affect Dermatologists

On November 2, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released its final rule for the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and the Quality Payment Program (QPP).1,2 These guidelines contain updates that will remarkably impact the field of medicine—and dermatology in particular—in 2022. This article will walk you through some of the updates most relevant to dermatology and how they may affect your practice.

Process for the Final Rule

The CMS releases an annual rule for the PFS and QPP. The interim rule generally is released over the summer with preliminary guidelines for the upcoming payment year. There is then a period of open comment where those affected by these changes, including physicians and medical associations, can submit comments to support what has been proposed or advocate for any changes. This input is then reviewed, and a final rule generally is published in the fall.

For this calendar year, the interim 2022 rule was released on July 13, 2021,3 and included many of guidelines that will be discussed in more detail in this article. Many associations that represent medicine overall and specifically dermatology, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, submitted comments in response to these proposals.4,5

PFS Conversion Factor

The PFS conversion factor is updated annually to ensure budget neutrality in the setting of changes in relative value units. For 2022, the PFS conversion factor is $34.6062, representing a reduction of approximately $0.29 from the 2021 PFS conversion factor of $34.8931.6 This reduction does not take into account other payment adjustments due to legislative changes.

In combination, these changes previously were estimated to represent an overall payment cut of 10% or higher for dermatology, with those practitioners doing more procedural work or dermatopathology likely being impacted more heavily. However, with the passing of the Protecting Medicare and American Farmers from Sequester Cuts Act, it is estimated that the reductions in payment to dermatology will begin at 0.75% and reach 2.75% in the second half of the year with the phased-in reinstatement of the Medicare sequester.4,5,7

Clinical Labor Pricing Updates

Starting in 2022, the CMS will utilize updated wage rates from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics to revise clinical labor costs over a 4-year period. Clinical labor rates are important, as they are used to calculate practice expense within the PFS. These clinical labor rates were last updated in 2002.8 Median wage data, as opposed to mean data, from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics will be utilized to calculate the updated clinical labor rates.

A multiyear implementation plan was put into place by CMS due to multiple concerns, including that current wage rates are inadequate and may not reflect current labor rate information. Additionally, comments on this proposal voiced concern that updating the supply and equipment pricing without updating the clinical labor pricing could create distortions in the allocation of direct practice expense, which also factored into the implementation of a multiyear plan.8

It is anticipated that specialties that rely primarily on clinical labor will receive the largest increases in these rates and that specialties that rely primarily on supply or equipment items are anticipated to receive the largest reductions relative to other specialties. Dermatology is estimated to have a 0% change during the year 1 transition period; however, it will have an estimated 1% reduction in clinical labor pricing overall once the updates are completed.1 Pathology also is estimated to have a similar overall decrease during this transition period.

Evaluation and Management Visits

The biggest update in this area primarily is related to refining policies for split (shared) evaluation and management (E/M) visits and teaching physician activities. Split E/M visits are defined by the CMS as visits provided in the facility setting by a physician and nonphysician practitioner in the same group, with the visit billed by whomever provides the substantive portion of the visit. For 2022, the term substantive portion will be defined by the CMS as history, physical examination, medical decision-making, or more than half of the total time; for 2023, it will be defined as more than half of the total time spent.3 A split visit also can apply to an E/M visit provided in part by both a teaching physician and resident. Split visits can be reported for new or established patients. For proper reimbursement, the 2 practitioners who performed the services must be documented in the medical record, and the practitioner who provided the substantive portion must sign and date the encounter in the medical record. Additionally, the CMS has indicated the modifier FS must be included on the claim to indicate the split visit.9

For dermatologists who act as teaching physicians, it is important to note that many of the existing CMS policies for billing E/M services are still in place, specifically that if a resident participates in a service in a teaching setting, the teaching physician can bill for the service only if they are present for the key or critical portion of the service. A primary care exception does exist, in which teaching physicians at certain teaching hospital primary care centers can bill for some services performed independently by a resident without the physical presence of the teaching physician; however, this often is not applicable within dermatology.

With updated outpatient E/M guidelines, if time is being selected to bill, only the time that the teaching physician was present can be included to determine the overall E/M level.

Billing for Physician Assistant Services

Currently Medicare can only make payments to the employer or independent contractor of a physician assistant (PA); however, starting January 1, 2022, the CMS has authorized Medicare to make direct payments to PAs for qualifying professional services, in the same manner that nurse practitioners can currently bill. This also will allow PAs to incorporate as a group and bill Medicare for PA services. This stems from a congressional mandate within the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021.8 As a result, in states where PAs can practice independently, they can opt out of physician-led care teams and furnish services independently, including dermatologic services.

QPP Updates

Several changes were made to the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Some of these changes include:

- Increase the MIPS performance threshold to 75 points from 60 points.

- Set the performance threshold at 89 points.

- Reduce the quality performance category weight from 40% to 30% of the final MIPS score.

- Increase the cost performance category weight from 20% to 30% of the final MIPS score.

- The extreme and uncontrollable circumstances application also has been extended to the end of 2022, allowing those remarkably impacted by the COVID-19 public health emergency to request for reweighting on any or all MIPS performance categories.

Cost Measures and MIPS Value Pathways

The melanoma resection cost measure will be implemented in 2022, representing the first dermatology cost measure, which will include the cost to Medicare over a 1-year period for all patient care for the excision of a melanoma. Although cost measures will be part of the MIPS value pathways (MVPs) reporting, dermatology currently is not part of the MVP; however, with the CMS moving forward with an initial set of MVPs that physicians can voluntarily report on in 2023, there is a possibility that dermatology will be asked to be part of the program in the future.10

Final Thoughts

There are many upcoming changes as part of the 2022 final rule, including to the conversion factor, E/M split visits, PA billing, and the QPP. Advocacy in these areas to the CMS and lawmakers, either directly or through dermatologic and other medical societies, is critical to help influence eventual recommendations.

- Medicare Program; CY 2022 payment policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and other changes to part B payment policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program requirements; provider enrollment regulation updates; and provider and supplier prepayment and post-payment medical review requirements. Fed Regist. 2021;86:64996-66031. To be codified at 42 CFR §403, §405, §410, §411, §414, §415, §423, §424, and §425. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/11/19/2021-23972/medicare-program-cy-2022-payment-policies-under-the-physician-fee-schedule-and-other-changes-to-part

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS physician payment rule promotes greater access to telehealth services, diabetes prevention programs. Published November 2, 2021. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-physician-payment-rule-promotes-greater-access-telehealth-services-diabetes-prevention-programs

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. Published July 13, 2021. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2022-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- American Academy of Dermatology. Dermatology World Weekly. October 27, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.aad.org/dw/weekly

- O’Reilly KB. 2022 Medicare pay schedule confirms Congress needs to act. American Medical Association website. Published November 10, 2021. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/2022-medicare-pay-schedule-confirms-congress-needs-act

- History of Medicare conversion factors. American Medical Association website. Accessed January 19, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2021-01/cf-history.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology. Dermatology World Weekly. December 15, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.aad.org/dw/weekly

- American Medical Association. CY 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and Quality Payment Program (QPP) final rule summary. Accessed January 10, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2022-pfs-qpp-final-rule.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. January 2022 alpha-numeric HCPCS file. Updated December 20, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets/HCPCS-Quarterly-Update

- CMS finalizes Medicare payments for 2022. American Academy of Dermatology website. NEED PUB DATE. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/mips/fee-schedule/2022-fee-schedule-final

On November 2, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released its final rule for the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and the Quality Payment Program (QPP).1,2 These guidelines contain updates that will remarkably impact the field of medicine—and dermatology in particular—in 2022. This article will walk you through some of the updates most relevant to dermatology and how they may affect your practice.

Process for the Final Rule

The CMS releases an annual rule for the PFS and QPP. The interim rule generally is released over the summer with preliminary guidelines for the upcoming payment year. There is then a period of open comment where those affected by these changes, including physicians and medical associations, can submit comments to support what has been proposed or advocate for any changes. This input is then reviewed, and a final rule generally is published in the fall.

For this calendar year, the interim 2022 rule was released on July 13, 2021,3 and included many of guidelines that will be discussed in more detail in this article. Many associations that represent medicine overall and specifically dermatology, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, submitted comments in response to these proposals.4,5

PFS Conversion Factor

The PFS conversion factor is updated annually to ensure budget neutrality in the setting of changes in relative value units. For 2022, the PFS conversion factor is $34.6062, representing a reduction of approximately $0.29 from the 2021 PFS conversion factor of $34.8931.6 This reduction does not take into account other payment adjustments due to legislative changes.

In combination, these changes previously were estimated to represent an overall payment cut of 10% or higher for dermatology, with those practitioners doing more procedural work or dermatopathology likely being impacted more heavily. However, with the passing of the Protecting Medicare and American Farmers from Sequester Cuts Act, it is estimated that the reductions in payment to dermatology will begin at 0.75% and reach 2.75% in the second half of the year with the phased-in reinstatement of the Medicare sequester.4,5,7

Clinical Labor Pricing Updates

Starting in 2022, the CMS will utilize updated wage rates from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics to revise clinical labor costs over a 4-year period. Clinical labor rates are important, as they are used to calculate practice expense within the PFS. These clinical labor rates were last updated in 2002.8 Median wage data, as opposed to mean data, from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics will be utilized to calculate the updated clinical labor rates.

A multiyear implementation plan was put into place by CMS due to multiple concerns, including that current wage rates are inadequate and may not reflect current labor rate information. Additionally, comments on this proposal voiced concern that updating the supply and equipment pricing without updating the clinical labor pricing could create distortions in the allocation of direct practice expense, which also factored into the implementation of a multiyear plan.8

It is anticipated that specialties that rely primarily on clinical labor will receive the largest increases in these rates and that specialties that rely primarily on supply or equipment items are anticipated to receive the largest reductions relative to other specialties. Dermatology is estimated to have a 0% change during the year 1 transition period; however, it will have an estimated 1% reduction in clinical labor pricing overall once the updates are completed.1 Pathology also is estimated to have a similar overall decrease during this transition period.

Evaluation and Management Visits

The biggest update in this area primarily is related to refining policies for split (shared) evaluation and management (E/M) visits and teaching physician activities. Split E/M visits are defined by the CMS as visits provided in the facility setting by a physician and nonphysician practitioner in the same group, with the visit billed by whomever provides the substantive portion of the visit. For 2022, the term substantive portion will be defined by the CMS as history, physical examination, medical decision-making, or more than half of the total time; for 2023, it will be defined as more than half of the total time spent.3 A split visit also can apply to an E/M visit provided in part by both a teaching physician and resident. Split visits can be reported for new or established patients. For proper reimbursement, the 2 practitioners who performed the services must be documented in the medical record, and the practitioner who provided the substantive portion must sign and date the encounter in the medical record. Additionally, the CMS has indicated the modifier FS must be included on the claim to indicate the split visit.9

For dermatologists who act as teaching physicians, it is important to note that many of the existing CMS policies for billing E/M services are still in place, specifically that if a resident participates in a service in a teaching setting, the teaching physician can bill for the service only if they are present for the key or critical portion of the service. A primary care exception does exist, in which teaching physicians at certain teaching hospital primary care centers can bill for some services performed independently by a resident without the physical presence of the teaching physician; however, this often is not applicable within dermatology.

With updated outpatient E/M guidelines, if time is being selected to bill, only the time that the teaching physician was present can be included to determine the overall E/M level.

Billing for Physician Assistant Services

Currently Medicare can only make payments to the employer or independent contractor of a physician assistant (PA); however, starting January 1, 2022, the CMS has authorized Medicare to make direct payments to PAs for qualifying professional services, in the same manner that nurse practitioners can currently bill. This also will allow PAs to incorporate as a group and bill Medicare for PA services. This stems from a congressional mandate within the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021.8 As a result, in states where PAs can practice independently, they can opt out of physician-led care teams and furnish services independently, including dermatologic services.

QPP Updates

Several changes were made to the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Some of these changes include:

- Increase the MIPS performance threshold to 75 points from 60 points.

- Set the performance threshold at 89 points.

- Reduce the quality performance category weight from 40% to 30% of the final MIPS score.

- Increase the cost performance category weight from 20% to 30% of the final MIPS score.

- The extreme and uncontrollable circumstances application also has been extended to the end of 2022, allowing those remarkably impacted by the COVID-19 public health emergency to request for reweighting on any or all MIPS performance categories.

Cost Measures and MIPS Value Pathways

The melanoma resection cost measure will be implemented in 2022, representing the first dermatology cost measure, which will include the cost to Medicare over a 1-year period for all patient care for the excision of a melanoma. Although cost measures will be part of the MIPS value pathways (MVPs) reporting, dermatology currently is not part of the MVP; however, with the CMS moving forward with an initial set of MVPs that physicians can voluntarily report on in 2023, there is a possibility that dermatology will be asked to be part of the program in the future.10

Final Thoughts

There are many upcoming changes as part of the 2022 final rule, including to the conversion factor, E/M split visits, PA billing, and the QPP. Advocacy in these areas to the CMS and lawmakers, either directly or through dermatologic and other medical societies, is critical to help influence eventual recommendations.

On November 2, 2021, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released its final rule for the 2022 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) and the Quality Payment Program (QPP).1,2 These guidelines contain updates that will remarkably impact the field of medicine—and dermatology in particular—in 2022. This article will walk you through some of the updates most relevant to dermatology and how they may affect your practice.

Process for the Final Rule

The CMS releases an annual rule for the PFS and QPP. The interim rule generally is released over the summer with preliminary guidelines for the upcoming payment year. There is then a period of open comment where those affected by these changes, including physicians and medical associations, can submit comments to support what has been proposed or advocate for any changes. This input is then reviewed, and a final rule generally is published in the fall.

For this calendar year, the interim 2022 rule was released on July 13, 2021,3 and included many of guidelines that will be discussed in more detail in this article. Many associations that represent medicine overall and specifically dermatology, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Dermatology, submitted comments in response to these proposals.4,5

PFS Conversion Factor

The PFS conversion factor is updated annually to ensure budget neutrality in the setting of changes in relative value units. For 2022, the PFS conversion factor is $34.6062, representing a reduction of approximately $0.29 from the 2021 PFS conversion factor of $34.8931.6 This reduction does not take into account other payment adjustments due to legislative changes.