User login

Is proactive TDM the way to go?

Dear colleagues,

We shift gears from discussing GI hospitalists to focusing on the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. The introduction of anti-TNFs brought about a paradigm shift in IBD management. With the ability to measure drug and antibody levels, we are also able to alter dose and timing to increase the efficacy of these medications. Some experts have extended this reactive drug monitoring approach to a more proactive method with the expectation that this may prevent loss of efficacy and development of adverse events. Dr. Loren G. Rabinowitz and colleagues and Dr. Hans Herfarth describe these two approaches to anti-TNF management in IBD, drawing from the current data and their own experiences. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Better outcomes than reactive TDM

By Loren G. Rabinowitz, MD; Konstantinos Papamichael, PhD, MD; and Adam S. Cheifetz, MD, AGAF

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), or the practice of treatment optimization based on serum drug concentrations, is used in many settings, including solid organ transplantation, infection, and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In IBD, the use of TDM has been an area of keen research focus, and, in our view, should be standard practice for optimization of biologic therapy, particularly in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. TDM has demonstrated utility in determining the correct timing and dosage of biologics and can provide the impetus for deescalating or discontinuing a biologic in favor of an alternative one. It also allows prescribers the ability to protect patients from severe infusion reactions if they have developed anti-drug antibodies (ADAs).

Reactive TDM refers to a strategy of assessing drug concentration and presence of ADAs in the setting of primary nonresponse (PNR) and loss of response (LOR) to a biologic agent. In this context, TDM informs possible reasons for loss or lack of response to treatment – for example, insufficient drug concentration or the development of high-titer ADAs (immunogenicity) – thus better directing the management of these unwanted outcomes.1 Insufficient anti-TNF concentrations have been associated with PNR and lack of clinical remission at 1 year in patients with IBD,2 which underscores the need for a durable strategy to ensure appropriate drug concentrations from the induction through maintenance phases of biologic administration. Reactive TDM can also be used to inform the decision to abandon a particular therapy in favor of a different biologic and to guide the selection of the next biologic agent, and has been shown to be less expensive than empiric dose escalation.2 With regard to infliximab and adalimumab, it is our practice to continue dose escalation until drug concentrations are above 10-15 mcg/mL prior to abandoning therapy.1

For a significant number of patients, reactive TDM identifies at-risk patients too late, when ADAs have already formed. Because the number of medications to treat IBD remains limited, waiting for a patient to lose response to an agent, particularly anti-TNF therapies, increases the likelihood of immunogenicity, thus rendering an agent unusable. Proactive TDM or checking drug trough concentrations preemptively and at predetermined intervals, and dosing to an appropriate concentration, can improve patient outcomes. If drug concentration is determined to be not “at target,” dosage and timing of administration can be increased with or without the addition of an immunomodulator (thiopurines or methotrexate) to optimize the biologic’s efficacy and prevent immunogenicity. This approach allows the provider to anticipate and proactively guard against PNR and future LOR.

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy has been associated with better patient outcomes in both pediatric and adult populations when compared with empiric dose optimization and/or reactive TDM.2,3 In patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases undergoing maintenance therapy with infliximab, proactive TDM was found to be more effective than treatment without TDM in sustaining disease control without disease worsening.4 Proactive TDM has been associated with better patient outcomes, including increased rates of clinical remission in both pediatric and adult populations and decreased rates of IBD-related surgery, hospitalization, serious infusion reactions, and development of ADAs, when compared with reactive TDM or empiric optimization. Preliminary data suggest that proactive TDM can also be used to efficiently guide dose deescalation in patients in remission with drug concentrations markedly above target and to allow for optimization of infliximab monotherapy so that combination therapy can be employed more judiciously (that is, in a patient who developed rapid ADA to a different anti-TNF).1 This could potentially attenuate the risks associated with long-term immunomodulator use, which include lymphomas and higher rates of serious and opportunistic infections. A recent study using a pharmacokinetic dashboard showed that the majority of patients with IBD will need accelerated dosing by the third infusion to maintain therapeutic infliximab concentrations during induction and maintenance therapy, highlighting the urgent need for widespread adoption of early proactive TDM.5 It is likely that proactive TDM is most important early in therapy when patients are most inflamed and have more rapid drug clearance. For this reason, proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase. It is our practice to continue to follow drug concentrations one or two times per year once a patient has achieved remission. A recent literature review and consensus statement highlights the utility of TDM and what is known at this time.1

TDM should be standard of care for patients with IBD. At minimum, reactive TDM has rationalized the management of PNR, is associated with better outcomes, and is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation.1,2 In this setting, however, many patients have already developed ADAs that cannot be overcome. At present, anti-TNF therapy remains the most effective agent for our sickest patients with IBD. Given the as-yet limited armamentarium of medications available, particularly for patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease (CD) and severe ulcerative colitis (UC), proactive TDM, which allows for improved optimization and long-term durability of biologics, is essential to the care of any IBD patient requiring these medications. Proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase and at least once during maintenance therapy. There is also the potential for TDM-driven dose de-escalation for patients in remission and optimization of infliximab monotherapy, thus avoiding combination therapy with an immunomodulator in some cases. Future perspectives for a more precise application of TDM include the use of pharmacokinetic modeling dashboards and pharmacogenetics toward achieving truly individualized medicine.3

Dr. Rabinowitz, Dr. Papamichael, and Dr. Cheifetz are with the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Rabinowitz reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Papamichael reports lecture fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Physicians’ Education Resource; consultancy fee from Prometheus Laboratories; and scientific advisory board fees from ProciseDx and Scipher Medicine Corporation. Dr. Cheifetz reports consulting for Janssen, AbbVie, Samsung, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Grifols, Prometheus, Bristol Myers Squibb, Artizan Biosciences, Artugan Therapeutics, and Equillium.

References

1. Cheifetz AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 1;116(10):2014-25.

2. Kennedy NA et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;4(5):341-53.

3. Papamichael K et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(2):171-85.

4. Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2375-84.

5. Dubinsky MC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 3. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab285.

Taking a closer look at the evidence

By Hans Herfarth, MD, PhD, AGAF

The debate of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy has been ongoing for more than a decade. Reactive TDM, the measurement of drug concentrations in the context of loss of treatment response, is now generally accepted and recommended in multiple national and international inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) guidelines. Proactive TDM, defined as the systematic measurement of drug trough concentrations and anti-drug antibodies with dose adaptations to a predefined target drug concentration, seems to offer a possibility to stabilize drug levels and prevent anti-drug antibody formation due to low systemic drug levels, thus potentially preventing the well-known loss of response to anti-TNF therapy, which occurs in more than 50% of patients over time. However, proactive TDM is not endorsed by evidence-based guidelines, dividing IBD physicians into believers and nonbelievers and limiting uptake into clinical practice.

As with reactive TDM, one should assume that the framework for proactive TDM should have been reliably established based on factual data derived from prospective controlled studies and not rely on retrospective cohorts or “Expert Panel” consensus statements. And indeed, several prospective controlled studies with sizable IBD patient cohorts have been published. Of note, all TDM studies for IBD were conducted in patients on anti-TNF maintenance therapy, and currently no prospective studies in larger IBD populations are available for proactive TDM during induction therapy. Two prospective studies, the PRECISION and the NOR-DRUM trial, report that proactive TDM is better than no TDM at all.

However, in the comparison of proactive TDM and reactive TDM (including at least one drug adaptation in maintenance or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers), three studies have demonstrated no significant differences in drug persistence or overall maintenance of clinical remission. Only a fourth (the pediatric PAILOT study) reported a lower frequency of mild flares and less steroid exposure in the proactive TDM arm over 1 year, but it did not show differences in drug persistence or overall clinical remission compared with the reactive TDM arm. Interestingly, the differences in flare frequency were apparent only in patients on monotherapy but not in the subgroup on combination therapy with an immunomodulator, stressing the well-known beneficial effect of a combination therapy with thiopurines in CD first shown in the SONIC trial.

One problem, at least in the TDM trials with infliximab (IFX), may have been a delay in optimizing IFX levels until the next drug infusion because of the turnaround time of the drug assays. However, even the most recently published ultra-proactive TDM study with ad hoc dose adjustments based on

The value of proactive TDM in induction therapy remains an ongoing concern. There is no doubt that the severity of intestinal inflammation with subsequent loss of drug in the intestine can result in low drug serum concentrations correlating to lower clinical responses and higher rates of immunogenicity with the formation of anti-drug antibodies. A recent study including patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis did not find a value in proactive TDM of IFX in the induction phase, but more severe IBD may have been underrepresented in this study. Administration of significantly higher induction dosing of adalimumab (160 mg weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3) with significantly higher trough levels compared with a standard induction regimen in the SERENE study has not been shown to increase the short- or long-term remission rates in UC or CD patients. Therefore, higher trough levels in a patient population do not automatically result in better outcomes, but proactive TDM may still have found a few patients who may have benefited from an even higher induction regimen. The UC and CD SERENE maintenance studies also evaluated proactive TDM versus clinical adjustment based on clinical and biomarkers. After 1 year, no differences in the efficacy endpoints of clinical, endoscopic, and deep remission were found. These somewhat surprising results, which have been reported only in meeting abstracts, suggest that simply increasing trough levels to a higher target (one of the primary aims of proactive TDM) is not an effective universal approach for achieving higher remission rates in induction or better outcomes in maintenance. Instead, the SERENE data show that similar results can be achieved by regular clinical follow-up and monitoring of loss of response based on symptoms and/or biochemical markers followed by drug adaptation (which may then also be based on reactive TDM).

One unquestionable effect of proactive TDM is that the process of checking and controlling drug levels suggests for the treating physician better control over the anti-TNF therapy and for the patient reassurance that the treatment is in the intended target range. Proactive TDM also may be cost effective in the group of patients whose anti-TNF treatment regimen can be deescalated because of high drug levels. Despite the increased number of studies showing no clinical advantage of proactive TDM of every patient on anti-TNF therapy, there may be benefits for subgroups. Proactive TDM with point-of-care testing of drug levels may be helpful during induction therapy in patients with a high inflammatory burden, which results in uncontrolled drug loss via the intestine. Proactive TDM during maintenance therapy (for example, every 6-12 months) may be beneficial in subgroups of patients at risk for developing low anti-TNF levels or anti-drug antibodies, such as patients with a genetic predisposition to anti-TNF anti-drug antibody formation (such as the HLA-DQ1*05 allele), patients on a second anti-TNF therapy after loss of response to the first one, and patients on anti-TNF therapy in combination with thiopurines or methotrexate who deescalate to anti-TNF monotherapy.

In summary, there is no doubt that proactive TDM is better than no TDM (meaning no drug adjustments at all). However, nearly all controlled prospective studies show no significant benefit of proactive TDM versus reactive TDM or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers. Future studies should target clearly defined patient groups at risk of losing response to anti-TNF to clarify if proactive TDM is a valuable tool to achieving better therapeutic results in clinical practice.

Dr. Herfarth is professor of medicine and codirector of the UNC Multidisciplinary IBD Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reports serving as a consultant to Alivio Therapeutics, AMAG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingleheim, ExeGi Pharma, Finch, Gilead, Janssen, Lycera, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, PureTech, and Seres and receiving research support from Allakos, Artizan Biosciences, and Pfizer.

Relevant resources

- Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326:2375-84.

- Strik AS et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021 Feb;56(2):145-54.

- Bossuyt P et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Feb 23;16(2):199-206.

- D’Haens G et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1343-51.e1.

Dear colleagues,

We shift gears from discussing GI hospitalists to focusing on the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. The introduction of anti-TNFs brought about a paradigm shift in IBD management. With the ability to measure drug and antibody levels, we are also able to alter dose and timing to increase the efficacy of these medications. Some experts have extended this reactive drug monitoring approach to a more proactive method with the expectation that this may prevent loss of efficacy and development of adverse events. Dr. Loren G. Rabinowitz and colleagues and Dr. Hans Herfarth describe these two approaches to anti-TNF management in IBD, drawing from the current data and their own experiences. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Better outcomes than reactive TDM

By Loren G. Rabinowitz, MD; Konstantinos Papamichael, PhD, MD; and Adam S. Cheifetz, MD, AGAF

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), or the practice of treatment optimization based on serum drug concentrations, is used in many settings, including solid organ transplantation, infection, and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In IBD, the use of TDM has been an area of keen research focus, and, in our view, should be standard practice for optimization of biologic therapy, particularly in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. TDM has demonstrated utility in determining the correct timing and dosage of biologics and can provide the impetus for deescalating or discontinuing a biologic in favor of an alternative one. It also allows prescribers the ability to protect patients from severe infusion reactions if they have developed anti-drug antibodies (ADAs).

Reactive TDM refers to a strategy of assessing drug concentration and presence of ADAs in the setting of primary nonresponse (PNR) and loss of response (LOR) to a biologic agent. In this context, TDM informs possible reasons for loss or lack of response to treatment – for example, insufficient drug concentration or the development of high-titer ADAs (immunogenicity) – thus better directing the management of these unwanted outcomes.1 Insufficient anti-TNF concentrations have been associated with PNR and lack of clinical remission at 1 year in patients with IBD,2 which underscores the need for a durable strategy to ensure appropriate drug concentrations from the induction through maintenance phases of biologic administration. Reactive TDM can also be used to inform the decision to abandon a particular therapy in favor of a different biologic and to guide the selection of the next biologic agent, and has been shown to be less expensive than empiric dose escalation.2 With regard to infliximab and adalimumab, it is our practice to continue dose escalation until drug concentrations are above 10-15 mcg/mL prior to abandoning therapy.1

For a significant number of patients, reactive TDM identifies at-risk patients too late, when ADAs have already formed. Because the number of medications to treat IBD remains limited, waiting for a patient to lose response to an agent, particularly anti-TNF therapies, increases the likelihood of immunogenicity, thus rendering an agent unusable. Proactive TDM or checking drug trough concentrations preemptively and at predetermined intervals, and dosing to an appropriate concentration, can improve patient outcomes. If drug concentration is determined to be not “at target,” dosage and timing of administration can be increased with or without the addition of an immunomodulator (thiopurines or methotrexate) to optimize the biologic’s efficacy and prevent immunogenicity. This approach allows the provider to anticipate and proactively guard against PNR and future LOR.

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy has been associated with better patient outcomes in both pediatric and adult populations when compared with empiric dose optimization and/or reactive TDM.2,3 In patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases undergoing maintenance therapy with infliximab, proactive TDM was found to be more effective than treatment without TDM in sustaining disease control without disease worsening.4 Proactive TDM has been associated with better patient outcomes, including increased rates of clinical remission in both pediatric and adult populations and decreased rates of IBD-related surgery, hospitalization, serious infusion reactions, and development of ADAs, when compared with reactive TDM or empiric optimization. Preliminary data suggest that proactive TDM can also be used to efficiently guide dose deescalation in patients in remission with drug concentrations markedly above target and to allow for optimization of infliximab monotherapy so that combination therapy can be employed more judiciously (that is, in a patient who developed rapid ADA to a different anti-TNF).1 This could potentially attenuate the risks associated with long-term immunomodulator use, which include lymphomas and higher rates of serious and opportunistic infections. A recent study using a pharmacokinetic dashboard showed that the majority of patients with IBD will need accelerated dosing by the third infusion to maintain therapeutic infliximab concentrations during induction and maintenance therapy, highlighting the urgent need for widespread adoption of early proactive TDM.5 It is likely that proactive TDM is most important early in therapy when patients are most inflamed and have more rapid drug clearance. For this reason, proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase. It is our practice to continue to follow drug concentrations one or two times per year once a patient has achieved remission. A recent literature review and consensus statement highlights the utility of TDM and what is known at this time.1

TDM should be standard of care for patients with IBD. At minimum, reactive TDM has rationalized the management of PNR, is associated with better outcomes, and is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation.1,2 In this setting, however, many patients have already developed ADAs that cannot be overcome. At present, anti-TNF therapy remains the most effective agent for our sickest patients with IBD. Given the as-yet limited armamentarium of medications available, particularly for patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease (CD) and severe ulcerative colitis (UC), proactive TDM, which allows for improved optimization and long-term durability of biologics, is essential to the care of any IBD patient requiring these medications. Proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase and at least once during maintenance therapy. There is also the potential for TDM-driven dose de-escalation for patients in remission and optimization of infliximab monotherapy, thus avoiding combination therapy with an immunomodulator in some cases. Future perspectives for a more precise application of TDM include the use of pharmacokinetic modeling dashboards and pharmacogenetics toward achieving truly individualized medicine.3

Dr. Rabinowitz, Dr. Papamichael, and Dr. Cheifetz are with the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Rabinowitz reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Papamichael reports lecture fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Physicians’ Education Resource; consultancy fee from Prometheus Laboratories; and scientific advisory board fees from ProciseDx and Scipher Medicine Corporation. Dr. Cheifetz reports consulting for Janssen, AbbVie, Samsung, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Grifols, Prometheus, Bristol Myers Squibb, Artizan Biosciences, Artugan Therapeutics, and Equillium.

References

1. Cheifetz AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 1;116(10):2014-25.

2. Kennedy NA et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;4(5):341-53.

3. Papamichael K et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(2):171-85.

4. Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2375-84.

5. Dubinsky MC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 3. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab285.

Taking a closer look at the evidence

By Hans Herfarth, MD, PhD, AGAF

The debate of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy has been ongoing for more than a decade. Reactive TDM, the measurement of drug concentrations in the context of loss of treatment response, is now generally accepted and recommended in multiple national and international inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) guidelines. Proactive TDM, defined as the systematic measurement of drug trough concentrations and anti-drug antibodies with dose adaptations to a predefined target drug concentration, seems to offer a possibility to stabilize drug levels and prevent anti-drug antibody formation due to low systemic drug levels, thus potentially preventing the well-known loss of response to anti-TNF therapy, which occurs in more than 50% of patients over time. However, proactive TDM is not endorsed by evidence-based guidelines, dividing IBD physicians into believers and nonbelievers and limiting uptake into clinical practice.

As with reactive TDM, one should assume that the framework for proactive TDM should have been reliably established based on factual data derived from prospective controlled studies and not rely on retrospective cohorts or “Expert Panel” consensus statements. And indeed, several prospective controlled studies with sizable IBD patient cohorts have been published. Of note, all TDM studies for IBD were conducted in patients on anti-TNF maintenance therapy, and currently no prospective studies in larger IBD populations are available for proactive TDM during induction therapy. Two prospective studies, the PRECISION and the NOR-DRUM trial, report that proactive TDM is better than no TDM at all.

However, in the comparison of proactive TDM and reactive TDM (including at least one drug adaptation in maintenance or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers), three studies have demonstrated no significant differences in drug persistence or overall maintenance of clinical remission. Only a fourth (the pediatric PAILOT study) reported a lower frequency of mild flares and less steroid exposure in the proactive TDM arm over 1 year, but it did not show differences in drug persistence or overall clinical remission compared with the reactive TDM arm. Interestingly, the differences in flare frequency were apparent only in patients on monotherapy but not in the subgroup on combination therapy with an immunomodulator, stressing the well-known beneficial effect of a combination therapy with thiopurines in CD first shown in the SONIC trial.

One problem, at least in the TDM trials with infliximab (IFX), may have been a delay in optimizing IFX levels until the next drug infusion because of the turnaround time of the drug assays. However, even the most recently published ultra-proactive TDM study with ad hoc dose adjustments based on

The value of proactive TDM in induction therapy remains an ongoing concern. There is no doubt that the severity of intestinal inflammation with subsequent loss of drug in the intestine can result in low drug serum concentrations correlating to lower clinical responses and higher rates of immunogenicity with the formation of anti-drug antibodies. A recent study including patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis did not find a value in proactive TDM of IFX in the induction phase, but more severe IBD may have been underrepresented in this study. Administration of significantly higher induction dosing of adalimumab (160 mg weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3) with significantly higher trough levels compared with a standard induction regimen in the SERENE study has not been shown to increase the short- or long-term remission rates in UC or CD patients. Therefore, higher trough levels in a patient population do not automatically result in better outcomes, but proactive TDM may still have found a few patients who may have benefited from an even higher induction regimen. The UC and CD SERENE maintenance studies also evaluated proactive TDM versus clinical adjustment based on clinical and biomarkers. After 1 year, no differences in the efficacy endpoints of clinical, endoscopic, and deep remission were found. These somewhat surprising results, which have been reported only in meeting abstracts, suggest that simply increasing trough levels to a higher target (one of the primary aims of proactive TDM) is not an effective universal approach for achieving higher remission rates in induction or better outcomes in maintenance. Instead, the SERENE data show that similar results can be achieved by regular clinical follow-up and monitoring of loss of response based on symptoms and/or biochemical markers followed by drug adaptation (which may then also be based on reactive TDM).

One unquestionable effect of proactive TDM is that the process of checking and controlling drug levels suggests for the treating physician better control over the anti-TNF therapy and for the patient reassurance that the treatment is in the intended target range. Proactive TDM also may be cost effective in the group of patients whose anti-TNF treatment regimen can be deescalated because of high drug levels. Despite the increased number of studies showing no clinical advantage of proactive TDM of every patient on anti-TNF therapy, there may be benefits for subgroups. Proactive TDM with point-of-care testing of drug levels may be helpful during induction therapy in patients with a high inflammatory burden, which results in uncontrolled drug loss via the intestine. Proactive TDM during maintenance therapy (for example, every 6-12 months) may be beneficial in subgroups of patients at risk for developing low anti-TNF levels or anti-drug antibodies, such as patients with a genetic predisposition to anti-TNF anti-drug antibody formation (such as the HLA-DQ1*05 allele), patients on a second anti-TNF therapy after loss of response to the first one, and patients on anti-TNF therapy in combination with thiopurines or methotrexate who deescalate to anti-TNF monotherapy.

In summary, there is no doubt that proactive TDM is better than no TDM (meaning no drug adjustments at all). However, nearly all controlled prospective studies show no significant benefit of proactive TDM versus reactive TDM or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers. Future studies should target clearly defined patient groups at risk of losing response to anti-TNF to clarify if proactive TDM is a valuable tool to achieving better therapeutic results in clinical practice.

Dr. Herfarth is professor of medicine and codirector of the UNC Multidisciplinary IBD Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reports serving as a consultant to Alivio Therapeutics, AMAG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingleheim, ExeGi Pharma, Finch, Gilead, Janssen, Lycera, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, PureTech, and Seres and receiving research support from Allakos, Artizan Biosciences, and Pfizer.

Relevant resources

- Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326:2375-84.

- Strik AS et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021 Feb;56(2):145-54.

- Bossuyt P et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Feb 23;16(2):199-206.

- D’Haens G et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1343-51.e1.

Dear colleagues,

We shift gears from discussing GI hospitalists to focusing on the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. The introduction of anti-TNFs brought about a paradigm shift in IBD management. With the ability to measure drug and antibody levels, we are also able to alter dose and timing to increase the efficacy of these medications. Some experts have extended this reactive drug monitoring approach to a more proactive method with the expectation that this may prevent loss of efficacy and development of adverse events. Dr. Loren G. Rabinowitz and colleagues and Dr. Hans Herfarth describe these two approaches to anti-TNF management in IBD, drawing from the current data and their own experiences. I look forward to hearing your thoughts and experiences by email ([email protected]).

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is an assistant professor of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Better outcomes than reactive TDM

By Loren G. Rabinowitz, MD; Konstantinos Papamichael, PhD, MD; and Adam S. Cheifetz, MD, AGAF

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), or the practice of treatment optimization based on serum drug concentrations, is used in many settings, including solid organ transplantation, infection, and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In IBD, the use of TDM has been an area of keen research focus, and, in our view, should be standard practice for optimization of biologic therapy, particularly in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. TDM has demonstrated utility in determining the correct timing and dosage of biologics and can provide the impetus for deescalating or discontinuing a biologic in favor of an alternative one. It also allows prescribers the ability to protect patients from severe infusion reactions if they have developed anti-drug antibodies (ADAs).

Reactive TDM refers to a strategy of assessing drug concentration and presence of ADAs in the setting of primary nonresponse (PNR) and loss of response (LOR) to a biologic agent. In this context, TDM informs possible reasons for loss or lack of response to treatment – for example, insufficient drug concentration or the development of high-titer ADAs (immunogenicity) – thus better directing the management of these unwanted outcomes.1 Insufficient anti-TNF concentrations have been associated with PNR and lack of clinical remission at 1 year in patients with IBD,2 which underscores the need for a durable strategy to ensure appropriate drug concentrations from the induction through maintenance phases of biologic administration. Reactive TDM can also be used to inform the decision to abandon a particular therapy in favor of a different biologic and to guide the selection of the next biologic agent, and has been shown to be less expensive than empiric dose escalation.2 With regard to infliximab and adalimumab, it is our practice to continue dose escalation until drug concentrations are above 10-15 mcg/mL prior to abandoning therapy.1

For a significant number of patients, reactive TDM identifies at-risk patients too late, when ADAs have already formed. Because the number of medications to treat IBD remains limited, waiting for a patient to lose response to an agent, particularly anti-TNF therapies, increases the likelihood of immunogenicity, thus rendering an agent unusable. Proactive TDM or checking drug trough concentrations preemptively and at predetermined intervals, and dosing to an appropriate concentration, can improve patient outcomes. If drug concentration is determined to be not “at target,” dosage and timing of administration can be increased with or without the addition of an immunomodulator (thiopurines or methotrexate) to optimize the biologic’s efficacy and prevent immunogenicity. This approach allows the provider to anticipate and proactively guard against PNR and future LOR.

Proactive TDM of anti-TNF therapy has been associated with better patient outcomes in both pediatric and adult populations when compared with empiric dose optimization and/or reactive TDM.2,3 In patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases undergoing maintenance therapy with infliximab, proactive TDM was found to be more effective than treatment without TDM in sustaining disease control without disease worsening.4 Proactive TDM has been associated with better patient outcomes, including increased rates of clinical remission in both pediatric and adult populations and decreased rates of IBD-related surgery, hospitalization, serious infusion reactions, and development of ADAs, when compared with reactive TDM or empiric optimization. Preliminary data suggest that proactive TDM can also be used to efficiently guide dose deescalation in patients in remission with drug concentrations markedly above target and to allow for optimization of infliximab monotherapy so that combination therapy can be employed more judiciously (that is, in a patient who developed rapid ADA to a different anti-TNF).1 This could potentially attenuate the risks associated with long-term immunomodulator use, which include lymphomas and higher rates of serious and opportunistic infections. A recent study using a pharmacokinetic dashboard showed that the majority of patients with IBD will need accelerated dosing by the third infusion to maintain therapeutic infliximab concentrations during induction and maintenance therapy, highlighting the urgent need for widespread adoption of early proactive TDM.5 It is likely that proactive TDM is most important early in therapy when patients are most inflamed and have more rapid drug clearance. For this reason, proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase. It is our practice to continue to follow drug concentrations one or two times per year once a patient has achieved remission. A recent literature review and consensus statement highlights the utility of TDM and what is known at this time.1

TDM should be standard of care for patients with IBD. At minimum, reactive TDM has rationalized the management of PNR, is associated with better outcomes, and is more cost effective than empiric dose escalation.1,2 In this setting, however, many patients have already developed ADAs that cannot be overcome. At present, anti-TNF therapy remains the most effective agent for our sickest patients with IBD. Given the as-yet limited armamentarium of medications available, particularly for patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease (CD) and severe ulcerative colitis (UC), proactive TDM, which allows for improved optimization and long-term durability of biologics, is essential to the care of any IBD patient requiring these medications. Proactive TDM should ideally be used for all patients during the induction phase and at least once during maintenance therapy. There is also the potential for TDM-driven dose de-escalation for patients in remission and optimization of infliximab monotherapy, thus avoiding combination therapy with an immunomodulator in some cases. Future perspectives for a more precise application of TDM include the use of pharmacokinetic modeling dashboards and pharmacogenetics toward achieving truly individualized medicine.3

Dr. Rabinowitz, Dr. Papamichael, and Dr. Cheifetz are with the department of medicine and division of gastroenterology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Dr. Rabinowitz reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Papamichael reports lecture fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma and Physicians’ Education Resource; consultancy fee from Prometheus Laboratories; and scientific advisory board fees from ProciseDx and Scipher Medicine Corporation. Dr. Cheifetz reports consulting for Janssen, AbbVie, Samsung, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Grifols, Prometheus, Bristol Myers Squibb, Artizan Biosciences, Artugan Therapeutics, and Equillium.

References

1. Cheifetz AS et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021 Oct 1;116(10):2014-25.

2. Kennedy NA et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May;4(5):341-53.

3. Papamichael K et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(2):171-85.

4. Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326(23):2375-84.

5. Dubinsky MC et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 Jan 3. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab285.

Taking a closer look at the evidence

By Hans Herfarth, MD, PhD, AGAF

The debate of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the setting of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy has been ongoing for more than a decade. Reactive TDM, the measurement of drug concentrations in the context of loss of treatment response, is now generally accepted and recommended in multiple national and international inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) guidelines. Proactive TDM, defined as the systematic measurement of drug trough concentrations and anti-drug antibodies with dose adaptations to a predefined target drug concentration, seems to offer a possibility to stabilize drug levels and prevent anti-drug antibody formation due to low systemic drug levels, thus potentially preventing the well-known loss of response to anti-TNF therapy, which occurs in more than 50% of patients over time. However, proactive TDM is not endorsed by evidence-based guidelines, dividing IBD physicians into believers and nonbelievers and limiting uptake into clinical practice.

As with reactive TDM, one should assume that the framework for proactive TDM should have been reliably established based on factual data derived from prospective controlled studies and not rely on retrospective cohorts or “Expert Panel” consensus statements. And indeed, several prospective controlled studies with sizable IBD patient cohorts have been published. Of note, all TDM studies for IBD were conducted in patients on anti-TNF maintenance therapy, and currently no prospective studies in larger IBD populations are available for proactive TDM during induction therapy. Two prospective studies, the PRECISION and the NOR-DRUM trial, report that proactive TDM is better than no TDM at all.

However, in the comparison of proactive TDM and reactive TDM (including at least one drug adaptation in maintenance or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers), three studies have demonstrated no significant differences in drug persistence or overall maintenance of clinical remission. Only a fourth (the pediatric PAILOT study) reported a lower frequency of mild flares and less steroid exposure in the proactive TDM arm over 1 year, but it did not show differences in drug persistence or overall clinical remission compared with the reactive TDM arm. Interestingly, the differences in flare frequency were apparent only in patients on monotherapy but not in the subgroup on combination therapy with an immunomodulator, stressing the well-known beneficial effect of a combination therapy with thiopurines in CD first shown in the SONIC trial.

One problem, at least in the TDM trials with infliximab (IFX), may have been a delay in optimizing IFX levels until the next drug infusion because of the turnaround time of the drug assays. However, even the most recently published ultra-proactive TDM study with ad hoc dose adjustments based on

The value of proactive TDM in induction therapy remains an ongoing concern. There is no doubt that the severity of intestinal inflammation with subsequent loss of drug in the intestine can result in low drug serum concentrations correlating to lower clinical responses and higher rates of immunogenicity with the formation of anti-drug antibodies. A recent study including patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases such as IBD, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis did not find a value in proactive TDM of IFX in the induction phase, but more severe IBD may have been underrepresented in this study. Administration of significantly higher induction dosing of adalimumab (160 mg weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3) with significantly higher trough levels compared with a standard induction regimen in the SERENE study has not been shown to increase the short- or long-term remission rates in UC or CD patients. Therefore, higher trough levels in a patient population do not automatically result in better outcomes, but proactive TDM may still have found a few patients who may have benefited from an even higher induction regimen. The UC and CD SERENE maintenance studies also evaluated proactive TDM versus clinical adjustment based on clinical and biomarkers. After 1 year, no differences in the efficacy endpoints of clinical, endoscopic, and deep remission were found. These somewhat surprising results, which have been reported only in meeting abstracts, suggest that simply increasing trough levels to a higher target (one of the primary aims of proactive TDM) is not an effective universal approach for achieving higher remission rates in induction or better outcomes in maintenance. Instead, the SERENE data show that similar results can be achieved by regular clinical follow-up and monitoring of loss of response based on symptoms and/or biochemical markers followed by drug adaptation (which may then also be based on reactive TDM).

One unquestionable effect of proactive TDM is that the process of checking and controlling drug levels suggests for the treating physician better control over the anti-TNF therapy and for the patient reassurance that the treatment is in the intended target range. Proactive TDM also may be cost effective in the group of patients whose anti-TNF treatment regimen can be deescalated because of high drug levels. Despite the increased number of studies showing no clinical advantage of proactive TDM of every patient on anti-TNF therapy, there may be benefits for subgroups. Proactive TDM with point-of-care testing of drug levels may be helpful during induction therapy in patients with a high inflammatory burden, which results in uncontrolled drug loss via the intestine. Proactive TDM during maintenance therapy (for example, every 6-12 months) may be beneficial in subgroups of patients at risk for developing low anti-TNF levels or anti-drug antibodies, such as patients with a genetic predisposition to anti-TNF anti-drug antibody formation (such as the HLA-DQ1*05 allele), patients on a second anti-TNF therapy after loss of response to the first one, and patients on anti-TNF therapy in combination with thiopurines or methotrexate who deescalate to anti-TNF monotherapy.

In summary, there is no doubt that proactive TDM is better than no TDM (meaning no drug adjustments at all). However, nearly all controlled prospective studies show no significant benefit of proactive TDM versus reactive TDM or drug escalation based on clinical symptoms or biomarkers. Future studies should target clearly defined patient groups at risk of losing response to anti-TNF to clarify if proactive TDM is a valuable tool to achieving better therapeutic results in clinical practice.

Dr. Herfarth is professor of medicine and codirector of the UNC Multidisciplinary IBD Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He reports serving as a consultant to Alivio Therapeutics, AMAG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingleheim, ExeGi Pharma, Finch, Gilead, Janssen, Lycera, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, PureTech, and Seres and receiving research support from Allakos, Artizan Biosciences, and Pfizer.

Relevant resources

- Syversen SW et al. JAMA. 2021;326:2375-84.

- Strik AS et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2021 Feb;56(2):145-54.

- Bossuyt P et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Feb 23;16(2):199-206.

- D’Haens G et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1343-51.e1.

NY radiation oncologist loses license, poses ‘potential danger’

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The state Board for Professional Medical Conduct has revoked the medical license of Won Sam Yi, MD, following a lengthy review of the care he provided to seven cancer patients; six of them died.

“He is a danger to potential new patients should he be reinstated as a radiation oncologist,” board members wrote, according to a news report in the Buffalo News.

Dr. Yi’s lawyer said that he is appealing the decision.

Dr. Yi was the former CEO of the now-defunct private cancer practice CCS Oncology, located in western New York.

In 2018, the state health department brought numerous charges of professional misconduct against Dr. Yi, including charges that he had failed to “account for prior doses of radiotherapy” as well as exceeding “appropriate tissue tolerances” during the treatment.

Now, the state’s Board for Professional Medical Conduct has upheld nearly all of the departmental charges that had been levied against him, and also found that Dr. Yi failed to take responsibility or show contrition for his treatment decisions.

However, whistleblower claims from a former CSS Oncology employee were dismissed.

Troubled history

CCS Oncology was once one of the largest private cancer practices in Erie and Niagara counties, both in the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Dr. Yi purchased CCS Oncology in 2008 and was its sole shareholder, and in 2012 he also acquired CCS Medical. As of 2016, the practices provided care to about 30% of cancer patients in the region. CCS also began acquiring other practices as it expanded into noncancer specialties, including primary care.

However, CCS began to struggle financially in late 2016, when health insurance provider Independent Health announced it was removing CCS Oncology from its network, and several vendors and lenders subsequently sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The announcement from Independent Health was “financially devastating to CCS,” and also was “the direct cause” of the practice defaulting on its Bank of America loan and of the practice’s inability to pay not only its vendors but state and federal tax agencies, the Buffalo News reported. As a result, several vendors and lenders had sued CCS and Dr. Yi for nonpayment.

The FBI raided numerous CCS locations in March 2018, seizing financial and other data as part of an investigation into possible Medicare billing fraud. The following month, CCS filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, citing it owed millions of dollars to Bank of America and other creditors. Shortly afterward, the practice closed.

Medical misconduct

The state’s charges of professional misconduct accused Dr. Yi of “gross negligence,” “gross incompetence,” and several other cases of misconduct in treating seven patients between 2009 and 2013 at various CCS locations. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 72. Six of the seven patients died.

In one case, Dr. Yi was accused of providing whole-brain radiation therapy to a 43-year-old woman for about 6 weeks in 2012, but the treatment was “contrary to medical indications” and did not take into account prior doses of such treatment. The patient died in December of that year, and the board concluded that Dr. Yi had improperly treated her with a high dose of radiation that was intended to cure her cancer even though she was at a stage where her disease was incurable.

The state board eventually concluded that for all but one of the patients in question, Dr. Yi was guilty of misconduct in his treatment decisions. They wrote that Dr. Yi had frequently administered radiation doses without taking into account how much radiation therapy the patients had received previously and without considering the risk of serious complications for them.

Dr. Yi plans to appeal the board’s decision in state court, according to his attorney, Anthony Scher.

“Dr Yi has treated over 10,000 patients in his career,” Mr. Scher told the Buffalo News. “These handful of cases don’t represent the thousands of success stories that he’s had.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

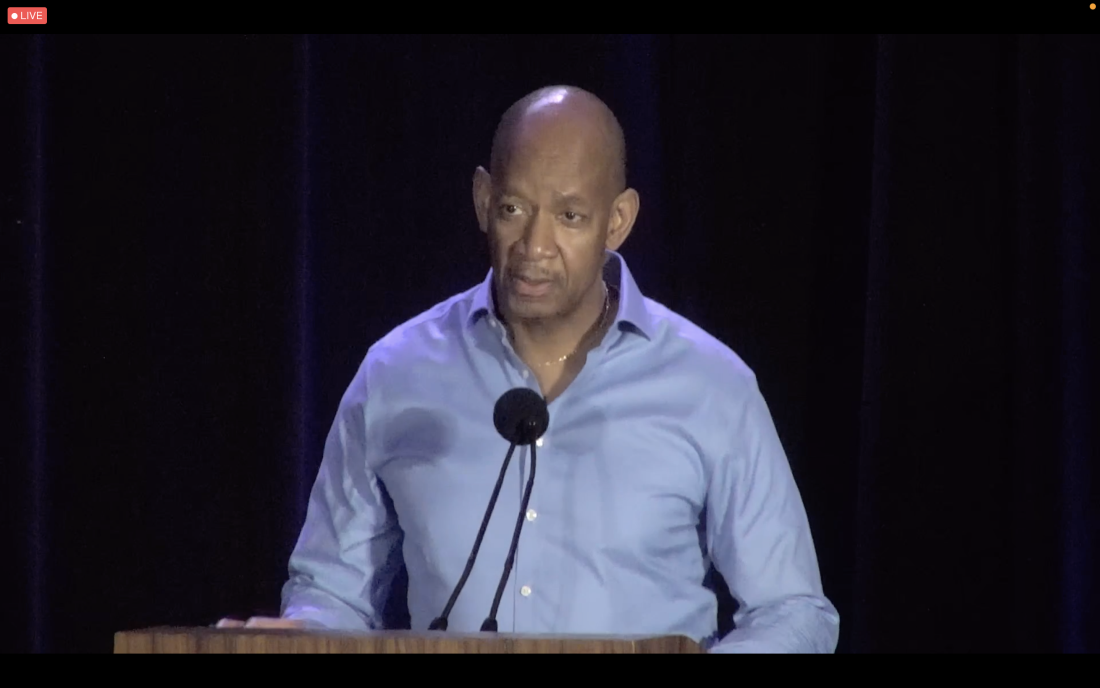

Health disparities exist all over rheumatology: What can be done?

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?

Eric Ruderman, MD, professor of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, commented that institutions have been forming committees and focus groups, but “not a lot of action.”

“They’re checking boxes,” he said, “which is very frustrating.” What can rheumatologists do in the short term, he asked?

Dr. Wells noted that there has been some success in using a “carrot” model of using payment models to reduce racial disparities. For example, a recent study analyzing the effects of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model highlighted the need for payment reform that incentivizes clinicians to spend wisely on patient treatment. Under a payment model that rewards clinicians for treating patients cost effectively, “if I do a great job cost effectively, I could just have more of that money back to my group,” he said.

George Martin, MD, a clinical dermatologist practicing in Maui, recalled the disparity in health care he observed as a child growing up in Philadelphia. “There’s really, within the city, there’s two different levels of health care,” he said. “There’s a tremendous disparity in the quality of the physician in hospital, and way out in the community. Because that’s the point of contact. That’s when either you’re going to prescribe a biologic, or [you’re] going to give them some aspirin and tell them go home. That’s where it starts, point of contact.”

Dr. Wells agreed that it is a big challenge, noting that cities also contribute to pollution, crowding, and other factors that adversely impact health care.

“It’s a shared responsibility. How do we solve that?” Dr. Martin asked. “And if you tell me, I’m going to give you a Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Wells reported he is a reviewer for the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?

Eric Ruderman, MD, professor of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, commented that institutions have been forming committees and focus groups, but “not a lot of action.”

“They’re checking boxes,” he said, “which is very frustrating.” What can rheumatologists do in the short term, he asked?

Dr. Wells noted that there has been some success in using a “carrot” model of using payment models to reduce racial disparities. For example, a recent study analyzing the effects of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model highlighted the need for payment reform that incentivizes clinicians to spend wisely on patient treatment. Under a payment model that rewards clinicians for treating patients cost effectively, “if I do a great job cost effectively, I could just have more of that money back to my group,” he said.

George Martin, MD, a clinical dermatologist practicing in Maui, recalled the disparity in health care he observed as a child growing up in Philadelphia. “There’s really, within the city, there’s two different levels of health care,” he said. “There’s a tremendous disparity in the quality of the physician in hospital, and way out in the community. Because that’s the point of contact. That’s when either you’re going to prescribe a biologic, or [you’re] going to give them some aspirin and tell them go home. That’s where it starts, point of contact.”

Dr. Wells agreed that it is a big challenge, noting that cities also contribute to pollution, crowding, and other factors that adversely impact health care.

“It’s a shared responsibility. How do we solve that?” Dr. Martin asked. “And if you tell me, I’m going to give you a Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Wells reported he is a reviewer for the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?