User login

Health care on holidays

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

My office was open on Presidents Day this year. Granted, I’ve never closed for it.

We’re also open on Veteran’s Day, Columbus Day, and Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Occasionally (usually MLK or Veteran’s days) we get a call from someone unhappy we’re open that day. Banks, government offices, and schools are closed, and they feel that, by not following suit, I’m insulting the memory of veterans and those who fought for civil rights.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, I don’t know any doctors’ offices that AREN’T open on those days.

Part of this is patient centered. When people need to see a doctor, they don’t want to wait too long. The emergency room isn’t where the majority of things should be handled. Besides, they’re already swamped with nonemergent cases.

Most practices work 8-5 on weekdays, and are booked out. Every additional weekday you’re closed only adds to the wait. So I try to be there enough days to care for people, but not enough so that I lose my sanity or family.

In my area, a fair number of my patients are schoolteachers, who work the same hours I do. So many of them come in on those days, and appreciate that I’m open when they’re off.

Another part is practical. In a small practice, cash flow is critical, and there are just so many days in a given year you can be closed without hurting your financial picture. So most practices are closed for the Big 6 (Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years). Usually this also includes Black Friday and Christmas Eve. So a total of 8 days per year (in addition to vacations).

Unlike other businesses (such as stores and restaurants) most medical offices aren’t open on weekends and nights, so our entire revenue stream is dependent on weekdays from 8 to 5. In this day and age, with most practices running on razor-thin margins, every day off adds to the red line. I can’t take care of anyone if I can’t pay my rent and staff.

I mean no disrespect to anyone. Like other doctors I work hard to provide quality care to all. But So I try to be there for them as much as I can, without going overboard and at the same time keeping my small practice afloat.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: PsA March 2022

The influence of sex and gender on psoriatic arthritis (PsA) continues to be of interest. Using data from the Dutch south-west Early Psoriatic Arthritis cohort (DEPAR), Passia et al1 assessed sex-related differences in demographics, disease characteristics, and evolution over 1 year in 273 men and 294 women newly diagnosed with PsA. They found that at baseline, women had a significantly longer duration of symptoms, higher tender joint count and enthesitis, higher disease activity, higher levels of pain, more severe limitations in function and worse quality of life. During the 1 year follow up, composite measures of disease activity declined in men and women, but women continued to have higher levels than men. At the end of 1 year, fewer women achieved the criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA). Thus, the disease burden of PsA was higher in women vs. men at all time points and even after 1 year of standard-of-care treatment. Sex-specific treatment strategies might help a higher proportion of women achieve MDA.

Although, enthesitis is believed to be a primary pathogenetic lesion in PsA, the relationship between active enthesitis and disease severity as measured by the presence of joint erosions is less well studied. In a cross-sectional study of 104 PsA patients, Smerilli et al2 explored the association between ultrasound (US) entheseal abnormalities and the presence of US detected bone erosions in PsA joints. At least 1 joint bone erosion was found in 45.2% of patients and was associated with power Doppler signal at enthesis (odds ratio [OR] 1.74; P < .01), entheseal bone erosions (OR 3.17; P = .01), and greyscale synovitis (OR 2.59; P = .02). Thus, Doppler signal and bone erosions at entheses indicate more severe PsA and patients with such abnormalities should therefore be treated aggressively.

Comorbidities and associated conditions were a focus of several publications last month. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is associated with inflammatory diseases, including PsA. In a retrospective cohort study including 5,275 patients with newly diagnosed PsA, Gazitt et al3 assessed the association between PsA and VTE events using a large population-based database in Israel. During follow-up, 1.2% vs. 0.8% patients in the PsA vs. control group were diagnosed with VTE, but this association was not statistically significant after adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; P = .16) with only older age (aHR 1.08; P < .0001) and history of VTE (aHR 31.63; P < .0001) remaining associated with an increased risk for VTE. Thus, VTE in patients with PsA may be associated with underlying comorbidities rather than PsA per se. In another study, Harris et al4 demonstrated that PsA was associated with increased risk of endometriosis. In an analysis of 4112 patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis from the Nurses’ Health Study II, they found that psoriasis with concomitant PsA was associated with increased risk for subsequent endometriosis (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.23-3.30), which persisted even after adjusting for comorbidities. Finally, in a cross-sectional study using data from 1862 juvenile PsA (jPsA) patients (122 [6.6%] of whom developed uveitis) in the German National Pediatric Rheumatological Database, Walscheid et al5 showed that patients with jPsA were more likely to develop uveitis if they were diagnosed with PsA at a younger age or were antinuclear antibody positive, with higher disease activity being the only factor significantly associated with the presence of uveitis.

References

1. Passia E et al. Sex-specific differences and how to handle them in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):22 (Jan 11).

2. Smerilli G et al. Doppler signal and bone erosions at the enthesis are independently associated with ultrasound joint erosive damage in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Feb 1).

3. Gazitt T et al. The association between psoriatic arthritis and venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):16 (Jan 7).

4. Harris HR et al. Endometriosis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2022 (Jan 13).

5. Walscheid K et al. Occurrence and risk factors of uveitis in juvenile psoriatic arthritis: Data from a population-based nationwide study in Germany. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Jan 15).

The influence of sex and gender on psoriatic arthritis (PsA) continues to be of interest. Using data from the Dutch south-west Early Psoriatic Arthritis cohort (DEPAR), Passia et al1 assessed sex-related differences in demographics, disease characteristics, and evolution over 1 year in 273 men and 294 women newly diagnosed with PsA. They found that at baseline, women had a significantly longer duration of symptoms, higher tender joint count and enthesitis, higher disease activity, higher levels of pain, more severe limitations in function and worse quality of life. During the 1 year follow up, composite measures of disease activity declined in men and women, but women continued to have higher levels than men. At the end of 1 year, fewer women achieved the criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA). Thus, the disease burden of PsA was higher in women vs. men at all time points and even after 1 year of standard-of-care treatment. Sex-specific treatment strategies might help a higher proportion of women achieve MDA.

Although, enthesitis is believed to be a primary pathogenetic lesion in PsA, the relationship between active enthesitis and disease severity as measured by the presence of joint erosions is less well studied. In a cross-sectional study of 104 PsA patients, Smerilli et al2 explored the association between ultrasound (US) entheseal abnormalities and the presence of US detected bone erosions in PsA joints. At least 1 joint bone erosion was found in 45.2% of patients and was associated with power Doppler signal at enthesis (odds ratio [OR] 1.74; P < .01), entheseal bone erosions (OR 3.17; P = .01), and greyscale synovitis (OR 2.59; P = .02). Thus, Doppler signal and bone erosions at entheses indicate more severe PsA and patients with such abnormalities should therefore be treated aggressively.

Comorbidities and associated conditions were a focus of several publications last month. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is associated with inflammatory diseases, including PsA. In a retrospective cohort study including 5,275 patients with newly diagnosed PsA, Gazitt et al3 assessed the association between PsA and VTE events using a large population-based database in Israel. During follow-up, 1.2% vs. 0.8% patients in the PsA vs. control group were diagnosed with VTE, but this association was not statistically significant after adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; P = .16) with only older age (aHR 1.08; P < .0001) and history of VTE (aHR 31.63; P < .0001) remaining associated with an increased risk for VTE. Thus, VTE in patients with PsA may be associated with underlying comorbidities rather than PsA per se. In another study, Harris et al4 demonstrated that PsA was associated with increased risk of endometriosis. In an analysis of 4112 patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis from the Nurses’ Health Study II, they found that psoriasis with concomitant PsA was associated with increased risk for subsequent endometriosis (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.23-3.30), which persisted even after adjusting for comorbidities. Finally, in a cross-sectional study using data from 1862 juvenile PsA (jPsA) patients (122 [6.6%] of whom developed uveitis) in the German National Pediatric Rheumatological Database, Walscheid et al5 showed that patients with jPsA were more likely to develop uveitis if they were diagnosed with PsA at a younger age or were antinuclear antibody positive, with higher disease activity being the only factor significantly associated with the presence of uveitis.

References

1. Passia E et al. Sex-specific differences and how to handle them in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):22 (Jan 11).

2. Smerilli G et al. Doppler signal and bone erosions at the enthesis are independently associated with ultrasound joint erosive damage in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Feb 1).

3. Gazitt T et al. The association between psoriatic arthritis and venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):16 (Jan 7).

4. Harris HR et al. Endometriosis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2022 (Jan 13).

5. Walscheid K et al. Occurrence and risk factors of uveitis in juvenile psoriatic arthritis: Data from a population-based nationwide study in Germany. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Jan 15).

The influence of sex and gender on psoriatic arthritis (PsA) continues to be of interest. Using data from the Dutch south-west Early Psoriatic Arthritis cohort (DEPAR), Passia et al1 assessed sex-related differences in demographics, disease characteristics, and evolution over 1 year in 273 men and 294 women newly diagnosed with PsA. They found that at baseline, women had a significantly longer duration of symptoms, higher tender joint count and enthesitis, higher disease activity, higher levels of pain, more severe limitations in function and worse quality of life. During the 1 year follow up, composite measures of disease activity declined in men and women, but women continued to have higher levels than men. At the end of 1 year, fewer women achieved the criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA). Thus, the disease burden of PsA was higher in women vs. men at all time points and even after 1 year of standard-of-care treatment. Sex-specific treatment strategies might help a higher proportion of women achieve MDA.

Although, enthesitis is believed to be a primary pathogenetic lesion in PsA, the relationship between active enthesitis and disease severity as measured by the presence of joint erosions is less well studied. In a cross-sectional study of 104 PsA patients, Smerilli et al2 explored the association between ultrasound (US) entheseal abnormalities and the presence of US detected bone erosions in PsA joints. At least 1 joint bone erosion was found in 45.2% of patients and was associated with power Doppler signal at enthesis (odds ratio [OR] 1.74; P < .01), entheseal bone erosions (OR 3.17; P = .01), and greyscale synovitis (OR 2.59; P = .02). Thus, Doppler signal and bone erosions at entheses indicate more severe PsA and patients with such abnormalities should therefore be treated aggressively.

Comorbidities and associated conditions were a focus of several publications last month. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is associated with inflammatory diseases, including PsA. In a retrospective cohort study including 5,275 patients with newly diagnosed PsA, Gazitt et al3 assessed the association between PsA and VTE events using a large population-based database in Israel. During follow-up, 1.2% vs. 0.8% patients in the PsA vs. control group were diagnosed with VTE, but this association was not statistically significant after adjusting for demographic factors and comorbidities (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.27; P = .16) with only older age (aHR 1.08; P < .0001) and history of VTE (aHR 31.63; P < .0001) remaining associated with an increased risk for VTE. Thus, VTE in patients with PsA may be associated with underlying comorbidities rather than PsA per se. In another study, Harris et al4 demonstrated that PsA was associated with increased risk of endometriosis. In an analysis of 4112 patients with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis from the Nurses’ Health Study II, they found that psoriasis with concomitant PsA was associated with increased risk for subsequent endometriosis (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.23-3.30), which persisted even after adjusting for comorbidities. Finally, in a cross-sectional study using data from 1862 juvenile PsA (jPsA) patients (122 [6.6%] of whom developed uveitis) in the German National Pediatric Rheumatological Database, Walscheid et al5 showed that patients with jPsA were more likely to develop uveitis if they were diagnosed with PsA at a younger age or were antinuclear antibody positive, with higher disease activity being the only factor significantly associated with the presence of uveitis.

References

1. Passia E et al. Sex-specific differences and how to handle them in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):22 (Jan 11).

2. Smerilli G et al. Doppler signal and bone erosions at the enthesis are independently associated with ultrasound joint erosive damage in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Feb 1).

3. Gazitt T et al. The association between psoriatic arthritis and venous thromboembolism: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24(1):16 (Jan 7).

4. Harris HR et al. Endometriosis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2022 (Jan 13).

5. Walscheid K et al. Occurrence and risk factors of uveitis in juvenile psoriatic arthritis: Data from a population-based nationwide study in Germany. J Rheumatol. 2022 (Jan 15).

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: RA March 2022

The recent ORAL Surveillance trial has raised concerns about the safety of tofacitinib (and potentially other JAK inhibitors) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.1 JAK inhibitors are known to increase cholesterol levels; however, this was not previously known to increase cardiovascular risk. The ORAL Surveillance trial was an open-label randomized non-inferiority trial comparing 5mg or 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor use. Both adverse cardiac events and cancer were increased in the tofacitinib groups (with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48, respectively). The study did not include a control group and so the impact of RA itself on cardiac events and cancer is not known. However, the apparent risk was greatest in patients over the age of 65, suggesting caution should be used in treating older patients with RA with JAK inhibitors. Interestingly, the STAR-RA study, an observational cohort study, looked at claims data from several sources to try to replicate trial results as well as provide real-world evidence on the topic of cardiovascular risk associated with tofacitinib use.2 The authors were able to replicate the inclusion/exclusion criteria from the ORAL Surveillance trial and found that the results were similar. However, on “relaxing” inclusion and exclusion criteria, ie, the “real-world evidence” cohort, there was no difference in incidence of cardiovascular outcomes between tofacitinib and TNF-inhibitor groups. Specifically, patients in the real-world cohort who had no cardiovascular risk factors or prior events were not found to have an increased cardiovascular risk with tofacitinib use, a reassuring finding supporting careful attention to cardiovascular risk in patients with RA when evaluating treatment options.

One consideration in the use of rituximab for treatment of RA is the possibility of changing or lowering subsequent or maintenance doses. Past studies have suggested that halving the dose of rituximab to a single 1000 mg infusion was tolerated by RA patients. The REDO trial, published in 2019, looked at even lower doses: 500 mg and 200 mg. The study did not establish non-inferiority of lower doses at 6 months in a per-protocol analysis, only in intention-to-treat. An extension study of REDO presented at the ACR Convergence in 2021 looked at a subset of those patients for up to 4 years and did find non-inferiority in terms of disease activity. Wientjes et al3 present further analysis of the REDO trial with 140 RA patients at 6 months, looking at the association of rituximab dosage with B cell counts as well as the predictive value of different patient characteristics in terms of response to lower dosages. Interestingly, serum drug levels and B cell counts at 3 and 6 months did not predict response to rituximab, nor did patient characteristics, such as age, smoking, disease, duration, or seropositivity for RF and CCP. Though the authors suggest that this implies even lower doses may be effective, it is not clear, and a similar analysis of the extension trial would be of interest.

Use of methotrexate as a first-line DMARD for RA is cost-effective but often limited by patient fears or intolerance due to adverse events (AE). This observational cohort study by Sherbini et al4 evaluates not only the prevalence of AE, but also baseline factors that may predict the development of AE. Over 1,000 patients with early RA initiating methotrexate were included in analysis. More than 75% reported at least one AE in 12 months, with gastrointestinal AE, such as nausea, being most prevalent (42%); 18% developed elevated liver enzyme tests (defined as a single reading above the upper limit of normal). Few strong predictors of AE were identified, though women were overall more likely than men to report AE. Reassuringly, combination conventional synthetic DMARD therapy did not generally lead to more reported AE. Given the few predictive findings from this study, analysis of a comparator group or comparison of AE at different starting and maintenance doses of methotrexate would be of interest.

References

- Ytterberg SR et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326 (Jan 27).

- Khosrow-Khavar F et al. Tofacitinib and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine care patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 (Jan 13).

- Wientjes MHM et al. Drug levels, anti-drug antibodies and B-cell counts were not predictive of response in rheumatoid arthritis patients on (ultra-)low-dose rituximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 12).

- Sherbini AA et al. Rates and predictors of methotrexate-related adverse events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a nationwide UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 25).

The recent ORAL Surveillance trial has raised concerns about the safety of tofacitinib (and potentially other JAK inhibitors) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.1 JAK inhibitors are known to increase cholesterol levels; however, this was not previously known to increase cardiovascular risk. The ORAL Surveillance trial was an open-label randomized non-inferiority trial comparing 5mg or 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor use. Both adverse cardiac events and cancer were increased in the tofacitinib groups (with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48, respectively). The study did not include a control group and so the impact of RA itself on cardiac events and cancer is not known. However, the apparent risk was greatest in patients over the age of 65, suggesting caution should be used in treating older patients with RA with JAK inhibitors. Interestingly, the STAR-RA study, an observational cohort study, looked at claims data from several sources to try to replicate trial results as well as provide real-world evidence on the topic of cardiovascular risk associated with tofacitinib use.2 The authors were able to replicate the inclusion/exclusion criteria from the ORAL Surveillance trial and found that the results were similar. However, on “relaxing” inclusion and exclusion criteria, ie, the “real-world evidence” cohort, there was no difference in incidence of cardiovascular outcomes between tofacitinib and TNF-inhibitor groups. Specifically, patients in the real-world cohort who had no cardiovascular risk factors or prior events were not found to have an increased cardiovascular risk with tofacitinib use, a reassuring finding supporting careful attention to cardiovascular risk in patients with RA when evaluating treatment options.

One consideration in the use of rituximab for treatment of RA is the possibility of changing or lowering subsequent or maintenance doses. Past studies have suggested that halving the dose of rituximab to a single 1000 mg infusion was tolerated by RA patients. The REDO trial, published in 2019, looked at even lower doses: 500 mg and 200 mg. The study did not establish non-inferiority of lower doses at 6 months in a per-protocol analysis, only in intention-to-treat. An extension study of REDO presented at the ACR Convergence in 2021 looked at a subset of those patients for up to 4 years and did find non-inferiority in terms of disease activity. Wientjes et al3 present further analysis of the REDO trial with 140 RA patients at 6 months, looking at the association of rituximab dosage with B cell counts as well as the predictive value of different patient characteristics in terms of response to lower dosages. Interestingly, serum drug levels and B cell counts at 3 and 6 months did not predict response to rituximab, nor did patient characteristics, such as age, smoking, disease, duration, or seropositivity for RF and CCP. Though the authors suggest that this implies even lower doses may be effective, it is not clear, and a similar analysis of the extension trial would be of interest.

Use of methotrexate as a first-line DMARD for RA is cost-effective but often limited by patient fears or intolerance due to adverse events (AE). This observational cohort study by Sherbini et al4 evaluates not only the prevalence of AE, but also baseline factors that may predict the development of AE. Over 1,000 patients with early RA initiating methotrexate were included in analysis. More than 75% reported at least one AE in 12 months, with gastrointestinal AE, such as nausea, being most prevalent (42%); 18% developed elevated liver enzyme tests (defined as a single reading above the upper limit of normal). Few strong predictors of AE were identified, though women were overall more likely than men to report AE. Reassuringly, combination conventional synthetic DMARD therapy did not generally lead to more reported AE. Given the few predictive findings from this study, analysis of a comparator group or comparison of AE at different starting and maintenance doses of methotrexate would be of interest.

References

- Ytterberg SR et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326 (Jan 27).

- Khosrow-Khavar F et al. Tofacitinib and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine care patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 (Jan 13).

- Wientjes MHM et al. Drug levels, anti-drug antibodies and B-cell counts were not predictive of response in rheumatoid arthritis patients on (ultra-)low-dose rituximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 12).

- Sherbini AA et al. Rates and predictors of methotrexate-related adverse events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a nationwide UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 25).

The recent ORAL Surveillance trial has raised concerns about the safety of tofacitinib (and potentially other JAK inhibitors) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.1 JAK inhibitors are known to increase cholesterol levels; however, this was not previously known to increase cardiovascular risk. The ORAL Surveillance trial was an open-label randomized non-inferiority trial comparing 5mg or 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor use. Both adverse cardiac events and cancer were increased in the tofacitinib groups (with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48, respectively). The study did not include a control group and so the impact of RA itself on cardiac events and cancer is not known. However, the apparent risk was greatest in patients over the age of 65, suggesting caution should be used in treating older patients with RA with JAK inhibitors. Interestingly, the STAR-RA study, an observational cohort study, looked at claims data from several sources to try to replicate trial results as well as provide real-world evidence on the topic of cardiovascular risk associated with tofacitinib use.2 The authors were able to replicate the inclusion/exclusion criteria from the ORAL Surveillance trial and found that the results were similar. However, on “relaxing” inclusion and exclusion criteria, ie, the “real-world evidence” cohort, there was no difference in incidence of cardiovascular outcomes between tofacitinib and TNF-inhibitor groups. Specifically, patients in the real-world cohort who had no cardiovascular risk factors or prior events were not found to have an increased cardiovascular risk with tofacitinib use, a reassuring finding supporting careful attention to cardiovascular risk in patients with RA when evaluating treatment options.

One consideration in the use of rituximab for treatment of RA is the possibility of changing or lowering subsequent or maintenance doses. Past studies have suggested that halving the dose of rituximab to a single 1000 mg infusion was tolerated by RA patients. The REDO trial, published in 2019, looked at even lower doses: 500 mg and 200 mg. The study did not establish non-inferiority of lower doses at 6 months in a per-protocol analysis, only in intention-to-treat. An extension study of REDO presented at the ACR Convergence in 2021 looked at a subset of those patients for up to 4 years and did find non-inferiority in terms of disease activity. Wientjes et al3 present further analysis of the REDO trial with 140 RA patients at 6 months, looking at the association of rituximab dosage with B cell counts as well as the predictive value of different patient characteristics in terms of response to lower dosages. Interestingly, serum drug levels and B cell counts at 3 and 6 months did not predict response to rituximab, nor did patient characteristics, such as age, smoking, disease, duration, or seropositivity for RF and CCP. Though the authors suggest that this implies even lower doses may be effective, it is not clear, and a similar analysis of the extension trial would be of interest.

Use of methotrexate as a first-line DMARD for RA is cost-effective but often limited by patient fears or intolerance due to adverse events (AE). This observational cohort study by Sherbini et al4 evaluates not only the prevalence of AE, but also baseline factors that may predict the development of AE. Over 1,000 patients with early RA initiating methotrexate were included in analysis. More than 75% reported at least one AE in 12 months, with gastrointestinal AE, such as nausea, being most prevalent (42%); 18% developed elevated liver enzyme tests (defined as a single reading above the upper limit of normal). Few strong predictors of AE were identified, though women were overall more likely than men to report AE. Reassuringly, combination conventional synthetic DMARD therapy did not generally lead to more reported AE. Given the few predictive findings from this study, analysis of a comparator group or comparison of AE at different starting and maintenance doses of methotrexate would be of interest.

References

- Ytterberg SR et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326 (Jan 27).

- Khosrow-Khavar F et al. Tofacitinib and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: results from the Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine care patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022 (Jan 13).

- Wientjes MHM et al. Drug levels, anti-drug antibodies and B-cell counts were not predictive of response in rheumatoid arthritis patients on (ultra-)low-dose rituximab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 12).

- Sherbini AA et al. Rates and predictors of methotrexate-related adverse events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a nationwide UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 (Jan 25).

Survey: Artificial intelligence finds support among dermatologists

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

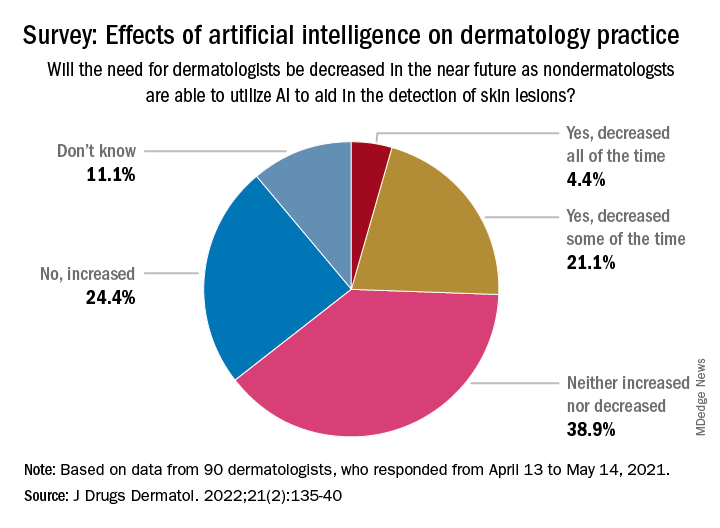

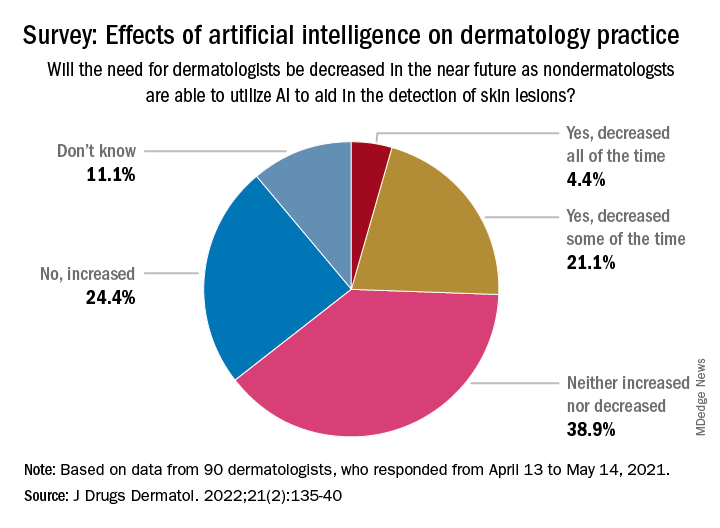

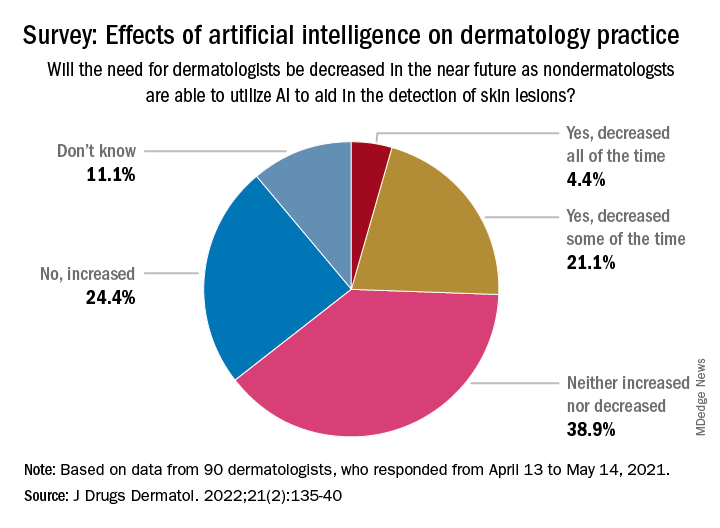

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

according to the results of a small survey.

Just 9% of the 90 respondents acknowledged that they have used AI in their practices, while 81% said they had not, and 10% weren’t sure or didn’t know. Despite that lack of familiarity, however, “many embrace the potential positive benefits, such as reducing misdiagnoses” and a majority (94.5%) “would use it at least in certain scenarios,” Vishal A. Patel, MD, and associates said in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

Dermatologists aged 40 years and under were more likely to have used AI previously: 15% reported previous experience, compared with 4% of those over age 40 – but the difference in “age did not have a significant effect on perception of AI,” the investigators noted, adding that most of the dermatologists over 40 believe “that AI would be most beneficial and used for detection of malignant skin lesions.”

The survey also asked about ways the respondents would use AI to help their patients. Almost two-thirds of respondents (66%) chose analysis and management of electronic health records “for research purposes to improve patient outcomes,” compared with 56% who chose identifying unknown/screening skin lesions “with a list of differential diagnoses,” 32% who chose telemedicine, and 26% who chose primary surveys of skin, said Dr. Patel, director of cutaneous oncology at the George Washington University Cancer Center in Washington, and coauthors.

The respondents were fairly evenly split when asked about the possible impact of nondermatologists using AI in the near future to detect skin lesions, such as melanomas, on the need for dermatologists. Just over a quarter said that the need for dermatologists will be decreased all (about 4.4%) or some (about 21.1%) of the time, and 24.4% said that the need will be increased, with the largest share (39.9%) of respondents choosing the middle ground: neither increased or decreased, the investigators reported.

The survey form was emailed to 850 members of the Orlando Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference listserv, with responses accepted from April 13 to May 14, 2021. The investigators noted that the response rate was low enough to be a limiting factor, making selection bias “by those with a particular interest in the topic” a possibility.

No funding sources for the study were disclosed. Dr. Patel disclosed that he is chief medical officer for Lazarus AI, the other authors had no disclosures listed.

FROM JOURNAL OF DRUGS IN DERMATOLOGY

The importance of a post-COVID wellness program for medical staff

LAS VEGAS – , according to Jon A. Levenson, MD.

“We can learn from previous pandemics and epidemics, which will be important for us going forward from COVID-19,” Dr. Levenson, associate professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2005, 68% of health care workers reported significant job-related stress, including increased workload, changing work duties, redeployment, shortage of medical supplies, concerns about insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of safety at work, absence of effective treatment protocols, inconsistent organizational support and information and misinformation from hospital management, and witnessing intense pain, isolation, and loss on a daily basis with few opportunities to take breaks (Psychiatr Serv. 2020 Oct 6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000274).

Personal concerns associated with psychopathological symptoms included spreading infection to family members; feeling responsibility for family members’ social isolation; self-isolating to avoid infecting family, which can lead to increased loneliness and sadness. “For those who were working remotely, this level of work is hard and challenging,” Dr. Levenson said. “For those who are parents, the 24-hour childcare responsibilities exist on top of work. They often found they can’t unwind with friends.”

Across SARS, MERS, Ebola, and swine flu, a wide range of prevalence in symptoms of distress, stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance use emerged, he continued. During COVID-19, at least three studies reported significant percentages of distress, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD among health care workers (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[3]:e203976, Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 8;11:608986., and Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Sep-Oct 2020;66:1-8).

“Who is at most-increased risk?” Dr. Levenson asked. “Women; those who are younger and have fewer years of work experience; those working on the front lines such as nurses and advanced practice professionals; and people with preexisting vulnerabilities to psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depression, obsessional symptoms, substance use, suicidal behavior, and impulse control disorders are likely to be especially vulnerable to stress-related symptoms.”

At CUIMC, there were certain “tipping points,” to the vulnerability of health care worker well-being in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, including the loss of an emergency medicine physician colleague from death by suicide. “On the national level there were so many other issues going on such as health care disparities of the COVID-19 infection itself, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, other issues of racial injustice, a tense political climate with an upcoming election at the time, and other factors related to the natural climate concerns,” he said. This prompted several faculty members in the CUIMC department of psychiatry including Claude Ann Mellins, PhD, Laurel S. Mayer, MD, and Lourival Baptista-Neto, MD, to partner with ColumbiaDoctors and New York-Presbyterian Hospital and develop a model of care for health care workers known as CopeColumbia, a virtual program intended to address staff burnout and fatigue, with an emphasis on prevention and promotion of resilience.* It launched in March of 2020 and consists of 1:1 peer support, a peer support group program, town halls/webinars, and an active web site.

The 1:1 peer support sessions typically last 20-30 minutes and provide easy access for all distressed hospital and medical center staff. “We have a phone line staffed by Columbia psychiatrists and psychologists so that a distressed staff member can reach support directly,” he said. The format of these sessions includes a brief discussion of challenges and brainstorming around potential coping strategies. “This is not a psychotherapy session,” Dr. Levenson said. “Each session can be individualized to further assess the type of distress or to implement rating scales such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale to assess for signs and symptoms consistent with GAD. There are options to schedule a second or third peer support session, or a prompt referral within Columbia psychiatry when indicated.”

A typical peer support group meeting lasts about 30 minutes and comprises individual divisions or departments. Some goals of the peer groups are to discuss unique challenges of the work environment and to encourage the members of the group to come up with solutions; to promote team support and coping; to teach resilience-enhancing strategies from empirically based treatments such as CBT, “and to end each meeting with expressions of gratitude and of thanks within the group,” he said.

According to Dr. Levenson, sample questions CopeColumbia faculty use to facilitate coping, include “which coping skills are working for you?”; “Are you able to be present?”; “Have you honored loss with any specific ways or traditions?”; “Do you have any work buddies who support you and vice versa?”; “Can your work community build off each other’s individual strengths to help both the individual and the work group cope optimally?”; and “How can your work team help facilitate each other to best support each other?”

Other aspects of the CopeColumbia program include town halls/grand rounds that range from 30 to 60 minutes in length. “It may be a virtual presentation from a mental health professional on specific aspects of coping such as relaxation techniques,” he said. “The focus is how to manage stress, anxiety, trauma, loss, and grief. It also includes an active Q&A to engage staff participants. The advantage of this format is that you can reach many staff in an entire department.” The program also has an active web site for staff with both internal and external support links including mindfulness, meditation, exercise, parenting suggestions/caregiving, and other resources to promote well-being and resilience for staff and family.

To date, certain themes emerged from the 1:1 and peer support group sessions, including expressions of difficulty adapting to “such a new reality,” compared with the pre-COVID era. “Staff would often express anticipatory anxiety and uncertainty, such as is there going to be another surge of COVID-19 cases, and will there be a change in policies?” Dr. Levenson said. “There was a lot of expression of stress and frustration related to politicizing the virus and public containment strategies, both on a local and national level.”

Staff also mentioned the loss of usual coping strategies because of prolonged social isolation, especially for those doing remote work, and the loss of usual support resources that have helped them in the past. “They also reported delayed trauma and grief reactions, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress,” he said. “Health care workers with children mentioned high levels of stress related to childcare, increased workload, and what seems like an impossible work-life balance.” Many reported exhaustion and irritability, “which could affect and cause tension within the work group and challenges to effective team cohesion,” he said. “There were also stressors related to the impact of racial injustices and the [presidential] election that could exacerbate the impact of COVID-19.”

Dr. Levenson hopes that CopeColumbia serves as a model for other health care systems looking for ways to support the mental well-being of their employees. “We want to promote the message that emotional health should have the same priority level as physical health,” he said. “The term that I like to use is total health. Addressing the well-being of health care workers is critical for a healthy workforce and for delivering high-quality patient care.”

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures related to his presentation.

Correction, 2/28/22: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Lourival Baptista-Neto's name.

LAS VEGAS – , according to Jon A. Levenson, MD.

“We can learn from previous pandemics and epidemics, which will be important for us going forward from COVID-19,” Dr. Levenson, associate professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2005, 68% of health care workers reported significant job-related stress, including increased workload, changing work duties, redeployment, shortage of medical supplies, concerns about insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of safety at work, absence of effective treatment protocols, inconsistent organizational support and information and misinformation from hospital management, and witnessing intense pain, isolation, and loss on a daily basis with few opportunities to take breaks (Psychiatr Serv. 2020 Oct 6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000274).

Personal concerns associated with psychopathological symptoms included spreading infection to family members; feeling responsibility for family members’ social isolation; self-isolating to avoid infecting family, which can lead to increased loneliness and sadness. “For those who were working remotely, this level of work is hard and challenging,” Dr. Levenson said. “For those who are parents, the 24-hour childcare responsibilities exist on top of work. They often found they can’t unwind with friends.”

Across SARS, MERS, Ebola, and swine flu, a wide range of prevalence in symptoms of distress, stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance use emerged, he continued. During COVID-19, at least three studies reported significant percentages of distress, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD among health care workers (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[3]:e203976, Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 8;11:608986., and Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Sep-Oct 2020;66:1-8).

“Who is at most-increased risk?” Dr. Levenson asked. “Women; those who are younger and have fewer years of work experience; those working on the front lines such as nurses and advanced practice professionals; and people with preexisting vulnerabilities to psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depression, obsessional symptoms, substance use, suicidal behavior, and impulse control disorders are likely to be especially vulnerable to stress-related symptoms.”

At CUIMC, there were certain “tipping points,” to the vulnerability of health care worker well-being in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, including the loss of an emergency medicine physician colleague from death by suicide. “On the national level there were so many other issues going on such as health care disparities of the COVID-19 infection itself, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, other issues of racial injustice, a tense political climate with an upcoming election at the time, and other factors related to the natural climate concerns,” he said. This prompted several faculty members in the CUIMC department of psychiatry including Claude Ann Mellins, PhD, Laurel S. Mayer, MD, and Lourival Baptista-Neto, MD, to partner with ColumbiaDoctors and New York-Presbyterian Hospital and develop a model of care for health care workers known as CopeColumbia, a virtual program intended to address staff burnout and fatigue, with an emphasis on prevention and promotion of resilience.* It launched in March of 2020 and consists of 1:1 peer support, a peer support group program, town halls/webinars, and an active web site.

The 1:1 peer support sessions typically last 20-30 minutes and provide easy access for all distressed hospital and medical center staff. “We have a phone line staffed by Columbia psychiatrists and psychologists so that a distressed staff member can reach support directly,” he said. The format of these sessions includes a brief discussion of challenges and brainstorming around potential coping strategies. “This is not a psychotherapy session,” Dr. Levenson said. “Each session can be individualized to further assess the type of distress or to implement rating scales such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale to assess for signs and symptoms consistent with GAD. There are options to schedule a second or third peer support session, or a prompt referral within Columbia psychiatry when indicated.”

A typical peer support group meeting lasts about 30 minutes and comprises individual divisions or departments. Some goals of the peer groups are to discuss unique challenges of the work environment and to encourage the members of the group to come up with solutions; to promote team support and coping; to teach resilience-enhancing strategies from empirically based treatments such as CBT, “and to end each meeting with expressions of gratitude and of thanks within the group,” he said.

According to Dr. Levenson, sample questions CopeColumbia faculty use to facilitate coping, include “which coping skills are working for you?”; “Are you able to be present?”; “Have you honored loss with any specific ways or traditions?”; “Do you have any work buddies who support you and vice versa?”; “Can your work community build off each other’s individual strengths to help both the individual and the work group cope optimally?”; and “How can your work team help facilitate each other to best support each other?”

Other aspects of the CopeColumbia program include town halls/grand rounds that range from 30 to 60 minutes in length. “It may be a virtual presentation from a mental health professional on specific aspects of coping such as relaxation techniques,” he said. “The focus is how to manage stress, anxiety, trauma, loss, and grief. It also includes an active Q&A to engage staff participants. The advantage of this format is that you can reach many staff in an entire department.” The program also has an active web site for staff with both internal and external support links including mindfulness, meditation, exercise, parenting suggestions/caregiving, and other resources to promote well-being and resilience for staff and family.

To date, certain themes emerged from the 1:1 and peer support group sessions, including expressions of difficulty adapting to “such a new reality,” compared with the pre-COVID era. “Staff would often express anticipatory anxiety and uncertainty, such as is there going to be another surge of COVID-19 cases, and will there be a change in policies?” Dr. Levenson said. “There was a lot of expression of stress and frustration related to politicizing the virus and public containment strategies, both on a local and national level.”

Staff also mentioned the loss of usual coping strategies because of prolonged social isolation, especially for those doing remote work, and the loss of usual support resources that have helped them in the past. “They also reported delayed trauma and grief reactions, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress,” he said. “Health care workers with children mentioned high levels of stress related to childcare, increased workload, and what seems like an impossible work-life balance.” Many reported exhaustion and irritability, “which could affect and cause tension within the work group and challenges to effective team cohesion,” he said. “There were also stressors related to the impact of racial injustices and the [presidential] election that could exacerbate the impact of COVID-19.”

Dr. Levenson hopes that CopeColumbia serves as a model for other health care systems looking for ways to support the mental well-being of their employees. “We want to promote the message that emotional health should have the same priority level as physical health,” he said. “The term that I like to use is total health. Addressing the well-being of health care workers is critical for a healthy workforce and for delivering high-quality patient care.”

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures related to his presentation.

Correction, 2/28/22: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Lourival Baptista-Neto's name.

LAS VEGAS – , according to Jon A. Levenson, MD.

“We can learn from previous pandemics and epidemics, which will be important for us going forward from COVID-19,” Dr. Levenson, associate professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said during an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

During the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2005, 68% of health care workers reported significant job-related stress, including increased workload, changing work duties, redeployment, shortage of medical supplies, concerns about insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of safety at work, absence of effective treatment protocols, inconsistent organizational support and information and misinformation from hospital management, and witnessing intense pain, isolation, and loss on a daily basis with few opportunities to take breaks (Psychiatr Serv. 2020 Oct 6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000274).

Personal concerns associated with psychopathological symptoms included spreading infection to family members; feeling responsibility for family members’ social isolation; self-isolating to avoid infecting family, which can lead to increased loneliness and sadness. “For those who were working remotely, this level of work is hard and challenging,” Dr. Levenson said. “For those who are parents, the 24-hour childcare responsibilities exist on top of work. They often found they can’t unwind with friends.”

Across SARS, MERS, Ebola, and swine flu, a wide range of prevalence in symptoms of distress, stress, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and substance use emerged, he continued. During COVID-19, at least three studies reported significant percentages of distress, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD among health care workers (JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[3]:e203976, Front Psychol. 2020 Dec 8;11:608986., and Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Sep-Oct 2020;66:1-8).

“Who is at most-increased risk?” Dr. Levenson asked. “Women; those who are younger and have fewer years of work experience; those working on the front lines such as nurses and advanced practice professionals; and people with preexisting vulnerabilities to psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depression, obsessional symptoms, substance use, suicidal behavior, and impulse control disorders are likely to be especially vulnerable to stress-related symptoms.”

At CUIMC, there were certain “tipping points,” to the vulnerability of health care worker well-being in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, including the loss of an emergency medicine physician colleague from death by suicide. “On the national level there were so many other issues going on such as health care disparities of the COVID-19 infection itself, the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, other issues of racial injustice, a tense political climate with an upcoming election at the time, and other factors related to the natural climate concerns,” he said. This prompted several faculty members in the CUIMC department of psychiatry including Claude Ann Mellins, PhD, Laurel S. Mayer, MD, and Lourival Baptista-Neto, MD, to partner with ColumbiaDoctors and New York-Presbyterian Hospital and develop a model of care for health care workers known as CopeColumbia, a virtual program intended to address staff burnout and fatigue, with an emphasis on prevention and promotion of resilience.* It launched in March of 2020 and consists of 1:1 peer support, a peer support group program, town halls/webinars, and an active web site.

The 1:1 peer support sessions typically last 20-30 minutes and provide easy access for all distressed hospital and medical center staff. “We have a phone line staffed by Columbia psychiatrists and psychologists so that a distressed staff member can reach support directly,” he said. The format of these sessions includes a brief discussion of challenges and brainstorming around potential coping strategies. “This is not a psychotherapy session,” Dr. Levenson said. “Each session can be individualized to further assess the type of distress or to implement rating scales such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale to assess for signs and symptoms consistent with GAD. There are options to schedule a second or third peer support session, or a prompt referral within Columbia psychiatry when indicated.”

A typical peer support group meeting lasts about 30 minutes and comprises individual divisions or departments. Some goals of the peer groups are to discuss unique challenges of the work environment and to encourage the members of the group to come up with solutions; to promote team support and coping; to teach resilience-enhancing strategies from empirically based treatments such as CBT, “and to end each meeting with expressions of gratitude and of thanks within the group,” he said.

According to Dr. Levenson, sample questions CopeColumbia faculty use to facilitate coping, include “which coping skills are working for you?”; “Are you able to be present?”; “Have you honored loss with any specific ways or traditions?”; “Do you have any work buddies who support you and vice versa?”; “Can your work community build off each other’s individual strengths to help both the individual and the work group cope optimally?”; and “How can your work team help facilitate each other to best support each other?”

Other aspects of the CopeColumbia program include town halls/grand rounds that range from 30 to 60 minutes in length. “It may be a virtual presentation from a mental health professional on specific aspects of coping such as relaxation techniques,” he said. “The focus is how to manage stress, anxiety, trauma, loss, and grief. It also includes an active Q&A to engage staff participants. The advantage of this format is that you can reach many staff in an entire department.” The program also has an active web site for staff with both internal and external support links including mindfulness, meditation, exercise, parenting suggestions/caregiving, and other resources to promote well-being and resilience for staff and family.

To date, certain themes emerged from the 1:1 and peer support group sessions, including expressions of difficulty adapting to “such a new reality,” compared with the pre-COVID era. “Staff would often express anticipatory anxiety and uncertainty, such as is there going to be another surge of COVID-19 cases, and will there be a change in policies?” Dr. Levenson said. “There was a lot of expression of stress and frustration related to politicizing the virus and public containment strategies, both on a local and national level.”

Staff also mentioned the loss of usual coping strategies because of prolonged social isolation, especially for those doing remote work, and the loss of usual support resources that have helped them in the past. “They also reported delayed trauma and grief reactions, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress,” he said. “Health care workers with children mentioned high levels of stress related to childcare, increased workload, and what seems like an impossible work-life balance.” Many reported exhaustion and irritability, “which could affect and cause tension within the work group and challenges to effective team cohesion,” he said. “There were also stressors related to the impact of racial injustices and the [presidential] election that could exacerbate the impact of COVID-19.”

Dr. Levenson hopes that CopeColumbia serves as a model for other health care systems looking for ways to support the mental well-being of their employees. “We want to promote the message that emotional health should have the same priority level as physical health,” he said. “The term that I like to use is total health. Addressing the well-being of health care workers is critical for a healthy workforce and for delivering high-quality patient care.”

He reported having no relevant financial disclosures related to his presentation.

Correction, 2/28/22: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Lourival Baptista-Neto's name.

FROM NPA 2022

Freiburg index accurately predicts survival in liver procedure

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

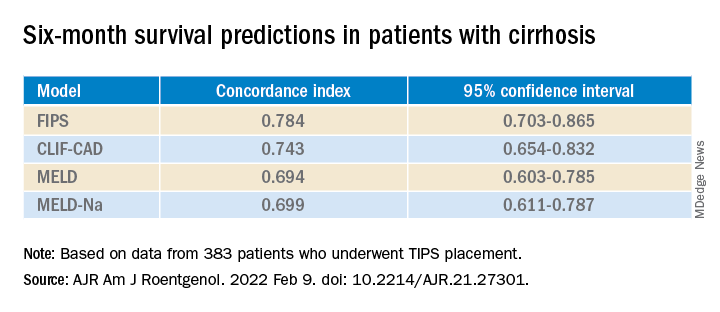

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

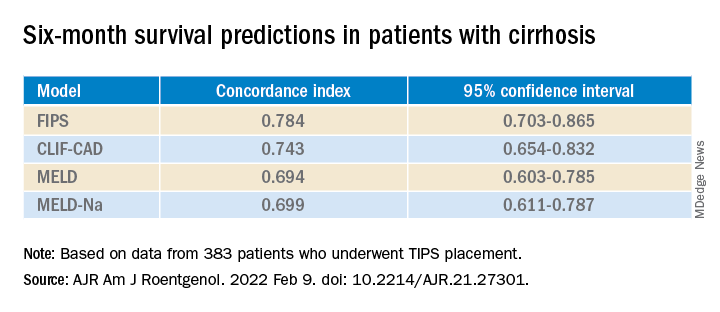

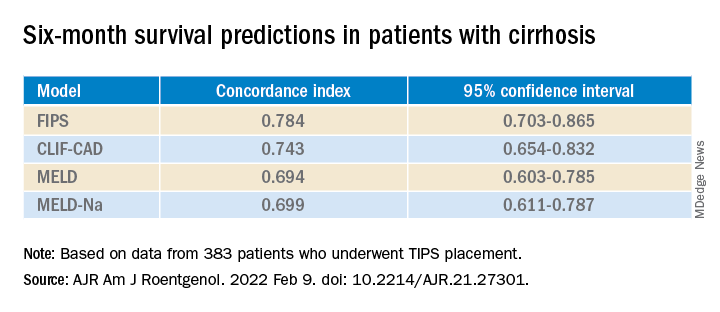

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.

By this measure, the prediction of survival at 6 months was highest for FIPS followed by CLIF-CAD, MELD, and MELD-Na. However, the confidence intervals overlapped.

FIPS also scored highest in the concordance index at 12 and 24 months.

In a second measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used Brier scores, which calculate the mean squared error between predicted probabilities and actual values. Like the concordance index, Brier scores range from 0.0 to 1.0 but differ in that the lowest Brier score number represents the highest accuracy.

At 6 months, the CLIF-CAD score was the best, at 0.074. MELD and FIPS were equivalent at 0.075, with MELD-Na coming in at 0.077. However, FIPS attained slightly better scores than the other systems at 12 and 24 months.

Is FIPS worth implementing?

With scores this close, it may not be worth changing the predictive model clinicians use for choosing TIPS candidates, said Nancy Reau, MD, chief of hepatology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, who was not involved in the study.

MELD scores are already programmed into many electronic medical record systems in the United States, and clinicians are familiar with using that system to aid in further decisions, such as decisions regarding other kinds of surgery, she told this news organization.

“If you’re going to try to advocate for a new system, you really have to show that the performance of the predictive score is monumentally better than the tried and true,” she said.

Dr. Yang and Dr. Reau report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new prognostic score is more accurate than the commonly used Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in predicting post–transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) survival, researchers say.

The Freiburg Index of Post-TIPS Survival (FIPS) could help patients and doctors weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure, said Chongtu Yang, MD, a postgraduate fellow at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

“For patients defined as high risk, the TIPS procedure may not be the optimal choice, and transplantation may be better,” Dr. Yang told this news organization. He cautioned that FIPS needs further validation before being applied in clinical practice.

The study by Dr. Yang and his colleagues was published online Feb. 9 in the American Journal of Roentgenology. To their knowledge, this is the first study to validate FIPS in a cohort of Asian patients.

Decompensated cirrhosis can cause variceal bleeding and refractory ascites and may be life threatening. TIPS can manage these complications but comes with its own risks.

To determine which patients can best benefit from the procedure, researchers have proposed a variety of prognostic scoring systems. Some were developed for other purposes, such as predicting survival following hospitalization, rather than specifically for TIPS. Additionally, few studies have compared these approaches to each other.

A four-way comparison

To fill that gap, Dr. Yang and his colleagues compared four predictive models: the MELD, the sodium MELD (MELD-Na), the Chronic Liver Failure–Consortium Acute Decompensation (CLIF-CAD), and FIPS.

The MELD score uses serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and the international normalized ratio (INR) of prothrombin time. MELD-Na adds sodium to this algorithm. The CLIF-CAD score is calculated using age, serum creatinine, INR, white blood count, and sodium level. FIPS, which was recently devised to predict results with TIPS, uses age, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine.

To see which yielded more accurate predictions, Dr. Yang and his colleagues followed 383 patients with cirrhosis (mean age, 55 years; 341 with variceal bleeding and 42 with refractory ascites) who underwent TIPS placement at Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2016 and August 2021.

The most common cause of cirrhosis was hepatitis B infection (58.2% of patients), followed by hepatitis C infection (11.7%) and alcohol use (13.6%).

The researchers followed the patients for a median of 23.4 months. They lost track of 31 patients over that time, and another 72 died. The survival rate after TIPS placement was 92.3% at 6 months, 87.8% at 12 months, and 81.2% at 24 months. Thirty-seven patients received a TIPS revision.

In their first measure of the models’ accuracy, the researchers used a concordance index, which compares actual results with predicted results. The number of concordant pairs are divided by the total number of possible evaluation pairs. A score of 1 represents 100% accuracy.