User login

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Migraine March 2022

The theme of the articles this month is migraine and blood vessels. Migraine is a known risk factor for vascular events, it is a known vasodilatory phenomenon, and it is commonly treated with vasoconstrictive medications. Genetic studies are further elucidating the connection between migraine and vascular risk factors. The following studies take this vascular connection to clinical relevance in different ways.

Previous studies have investigated the combination of simvastatin and vitamin D for migraine prevention. Statins have anti-inflammatory properties and migraine can partially be understood as an inflammatory vascular phenomenon. Vitamin D and simvastatin were previously shown to be effective in a randomized trial; this study1 investigated the combination of atorvastatin with nortriptyline for migraine prevention. Patients were excluded if they had a vitamin D deficiency.

This was a triple-blinded study with one control group, one placebo plus notriptyline group, and one atorvastatin plus nortiptyline group. The nortiptyline dosage was 25mg nightly, and the interventions were given for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was decrease in headache day frequency; secondary outcomes were severity and quality of life as measured by the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ).

Migraine frequency was seen to be significantly improved after 24 weeks in the statin group; however severity was not significantly affected. Adverse effects were mild and overall no subjects discontinued due to the intervention. Quality of life was also seen to be better in the combination statin/nortriptyline group.

The results of this study are compelling enough to consider the addition of a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) for a patient already on a statin or to start a statin (in the appropriate clinical setting) on a patient already on a TCA. The main limiting factor may be the hesitation to use a TCA medication in an older patient, where the anticholinergic effects may be less predictable.

Caffeine has a controversial place in the headache world. Many patients either use caffeine as a way to treat their migraine attacks, or avoid it completely as they are told it is a migraine trigger. Most headache specialists recommend the avoidance of excessive caffeine use (typically considered >150 mg daily) and tell their patients to be consistent about when they consume caffeine. The effect of caffeine on migraine likely is due to its vasoactive property, specifically that it is vasoconstrictive in nature. These vasoactive properties may also be why many studies investigating cerebrovascular reactivity have been inconclusive in the past.

The authors in this study2 recruited patients with episodic migraine and divided them based on caffeine use. All subjects underwent transcranial Doppler testing at baseline and after 3 months, caffeine users were instructed to discontinue caffeine in the interim. Doppler testing looked for differences in BHI (breath holding index) of the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries (PCA), which is a standard at their institution. Subjects were only investigated if they were headache-free and had not used a migraine abortive medication in the previous 48 hours. Preventive medications were not controlled for.

Although the investigators recommended discontinuation of caffeine for the caffeine users, only 28% of that subgroup did discontinue. They then subdivided the group of caffeine users into those whose caffeine intake increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Transcranial Doppler testing was performed in all subgroups.

The investigators found a lower BHI-PCA, or decrease in vasodilatory function, in the subgroups that remained on caffeine. Those who stopped caffeine had improvement in this metric, showing the possible reversibility that discontinuation of caffeine can have. It remains unclear precisely how caffeine is vasoactive, and the effects may be via adenosine receptors, endothelial function, neurotransmitter production, or regulation of the autonomic nervous system. The long-term vascular effects of caffeine are unknown, but they do appear to be reversible after a 3 month period.

Migraine, and especially migraine with aura, is well known as a vascular risk factor. The presence of migraine increases the odds ratio of stroke, myocardial ischemia, deep vein thrombosis and other vascular events significantly. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends avoiding the use of any estrogen containing medication in the presence of migraine, due to estrogen itself being a pro-thrombotic hormone. The precise mechanism that leads to this increased risk is unknown.

This study investigated the connection between migraine and large artery atherosclerosis (LAA). This group observed 415 consecutive patients aged 18-54 who presented for a first time ischemic stroke (other neurovascular events, such as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage with secondary ischemia and transient ischemic attacks, were excluded). Data regarding these patient’s risks factors was collected and analyzed including elevated body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia.

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as either magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA), and duplex ultrasound confirmed the images. Atherosclerosis was classified using a standardized system (ASCOD: atherosclerosis, small-vessel disease, cardiac pathology, other causes, and dissection) that grades atheroslerotic lesions on a 0-3 scale.

The results may be considered counterintuitive. The presence of migraine was negatively associated with the presence of LAA: a history of migraine did not increase the risk of atherosclerosis. This was even the case when controlling for the traditional vascular risk factors. The authors theorize that likely the association between migraine and stroke and other vascular events is not related to atherosclerosis and may be due to other causes.

A genome-wide association study recently identified a specific polymorphism that was shared by migraine and coronary artery disease. But just like this study, the people with migraine had a negative association with coronary artery disease. If people with migraine do develop stroke or other vascular phenomena they typically present younger and healthier, and this may be why this negative correlation exists.

References

- Sherafat M et al. The preventive effect of the combination of atorvastatin and nortriptyline in migraine-type headache: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2022 (Jan 17).

- Gil Y-E et al. Effect of caffeine and caffeine cessation on cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with migraine. Headache. 2022;62(2):169-75 (Feb 3).

- Gollion C et al. Migraine and large artery atherosclerosis in young adults with ischemic stroke. Headache. 2022;62(2):191-7 (Feb 5).

The theme of the articles this month is migraine and blood vessels. Migraine is a known risk factor for vascular events, it is a known vasodilatory phenomenon, and it is commonly treated with vasoconstrictive medications. Genetic studies are further elucidating the connection between migraine and vascular risk factors. The following studies take this vascular connection to clinical relevance in different ways.

Previous studies have investigated the combination of simvastatin and vitamin D for migraine prevention. Statins have anti-inflammatory properties and migraine can partially be understood as an inflammatory vascular phenomenon. Vitamin D and simvastatin were previously shown to be effective in a randomized trial; this study1 investigated the combination of atorvastatin with nortriptyline for migraine prevention. Patients were excluded if they had a vitamin D deficiency.

This was a triple-blinded study with one control group, one placebo plus notriptyline group, and one atorvastatin plus nortiptyline group. The nortiptyline dosage was 25mg nightly, and the interventions were given for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was decrease in headache day frequency; secondary outcomes were severity and quality of life as measured by the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ).

Migraine frequency was seen to be significantly improved after 24 weeks in the statin group; however severity was not significantly affected. Adverse effects were mild and overall no subjects discontinued due to the intervention. Quality of life was also seen to be better in the combination statin/nortriptyline group.

The results of this study are compelling enough to consider the addition of a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) for a patient already on a statin or to start a statin (in the appropriate clinical setting) on a patient already on a TCA. The main limiting factor may be the hesitation to use a TCA medication in an older patient, where the anticholinergic effects may be less predictable.

Caffeine has a controversial place in the headache world. Many patients either use caffeine as a way to treat their migraine attacks, or avoid it completely as they are told it is a migraine trigger. Most headache specialists recommend the avoidance of excessive caffeine use (typically considered >150 mg daily) and tell their patients to be consistent about when they consume caffeine. The effect of caffeine on migraine likely is due to its vasoactive property, specifically that it is vasoconstrictive in nature. These vasoactive properties may also be why many studies investigating cerebrovascular reactivity have been inconclusive in the past.

The authors in this study2 recruited patients with episodic migraine and divided them based on caffeine use. All subjects underwent transcranial Doppler testing at baseline and after 3 months, caffeine users were instructed to discontinue caffeine in the interim. Doppler testing looked for differences in BHI (breath holding index) of the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries (PCA), which is a standard at their institution. Subjects were only investigated if they were headache-free and had not used a migraine abortive medication in the previous 48 hours. Preventive medications were not controlled for.

Although the investigators recommended discontinuation of caffeine for the caffeine users, only 28% of that subgroup did discontinue. They then subdivided the group of caffeine users into those whose caffeine intake increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Transcranial Doppler testing was performed in all subgroups.

The investigators found a lower BHI-PCA, or decrease in vasodilatory function, in the subgroups that remained on caffeine. Those who stopped caffeine had improvement in this metric, showing the possible reversibility that discontinuation of caffeine can have. It remains unclear precisely how caffeine is vasoactive, and the effects may be via adenosine receptors, endothelial function, neurotransmitter production, or regulation of the autonomic nervous system. The long-term vascular effects of caffeine are unknown, but they do appear to be reversible after a 3 month period.

Migraine, and especially migraine with aura, is well known as a vascular risk factor. The presence of migraine increases the odds ratio of stroke, myocardial ischemia, deep vein thrombosis and other vascular events significantly. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends avoiding the use of any estrogen containing medication in the presence of migraine, due to estrogen itself being a pro-thrombotic hormone. The precise mechanism that leads to this increased risk is unknown.

This study investigated the connection between migraine and large artery atherosclerosis (LAA). This group observed 415 consecutive patients aged 18-54 who presented for a first time ischemic stroke (other neurovascular events, such as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage with secondary ischemia and transient ischemic attacks, were excluded). Data regarding these patient’s risks factors was collected and analyzed including elevated body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia.

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as either magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA), and duplex ultrasound confirmed the images. Atherosclerosis was classified using a standardized system (ASCOD: atherosclerosis, small-vessel disease, cardiac pathology, other causes, and dissection) that grades atheroslerotic lesions on a 0-3 scale.

The results may be considered counterintuitive. The presence of migraine was negatively associated with the presence of LAA: a history of migraine did not increase the risk of atherosclerosis. This was even the case when controlling for the traditional vascular risk factors. The authors theorize that likely the association between migraine and stroke and other vascular events is not related to atherosclerosis and may be due to other causes.

A genome-wide association study recently identified a specific polymorphism that was shared by migraine and coronary artery disease. But just like this study, the people with migraine had a negative association with coronary artery disease. If people with migraine do develop stroke or other vascular phenomena they typically present younger and healthier, and this may be why this negative correlation exists.

References

- Sherafat M et al. The preventive effect of the combination of atorvastatin and nortriptyline in migraine-type headache: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2022 (Jan 17).

- Gil Y-E et al. Effect of caffeine and caffeine cessation on cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with migraine. Headache. 2022;62(2):169-75 (Feb 3).

- Gollion C et al. Migraine and large artery atherosclerosis in young adults with ischemic stroke. Headache. 2022;62(2):191-7 (Feb 5).

The theme of the articles this month is migraine and blood vessels. Migraine is a known risk factor for vascular events, it is a known vasodilatory phenomenon, and it is commonly treated with vasoconstrictive medications. Genetic studies are further elucidating the connection between migraine and vascular risk factors. The following studies take this vascular connection to clinical relevance in different ways.

Previous studies have investigated the combination of simvastatin and vitamin D for migraine prevention. Statins have anti-inflammatory properties and migraine can partially be understood as an inflammatory vascular phenomenon. Vitamin D and simvastatin were previously shown to be effective in a randomized trial; this study1 investigated the combination of atorvastatin with nortriptyline for migraine prevention. Patients were excluded if they had a vitamin D deficiency.

This was a triple-blinded study with one control group, one placebo plus notriptyline group, and one atorvastatin plus nortiptyline group. The nortiptyline dosage was 25mg nightly, and the interventions were given for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was decrease in headache day frequency; secondary outcomes were severity and quality of life as measured by the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ).

Migraine frequency was seen to be significantly improved after 24 weeks in the statin group; however severity was not significantly affected. Adverse effects were mild and overall no subjects discontinued due to the intervention. Quality of life was also seen to be better in the combination statin/nortriptyline group.

The results of this study are compelling enough to consider the addition of a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) for a patient already on a statin or to start a statin (in the appropriate clinical setting) on a patient already on a TCA. The main limiting factor may be the hesitation to use a TCA medication in an older patient, where the anticholinergic effects may be less predictable.

Caffeine has a controversial place in the headache world. Many patients either use caffeine as a way to treat their migraine attacks, or avoid it completely as they are told it is a migraine trigger. Most headache specialists recommend the avoidance of excessive caffeine use (typically considered >150 mg daily) and tell their patients to be consistent about when they consume caffeine. The effect of caffeine on migraine likely is due to its vasoactive property, specifically that it is vasoconstrictive in nature. These vasoactive properties may also be why many studies investigating cerebrovascular reactivity have been inconclusive in the past.

The authors in this study2 recruited patients with episodic migraine and divided them based on caffeine use. All subjects underwent transcranial Doppler testing at baseline and after 3 months, caffeine users were instructed to discontinue caffeine in the interim. Doppler testing looked for differences in BHI (breath holding index) of the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries (PCA), which is a standard at their institution. Subjects were only investigated if they were headache-free and had not used a migraine abortive medication in the previous 48 hours. Preventive medications were not controlled for.

Although the investigators recommended discontinuation of caffeine for the caffeine users, only 28% of that subgroup did discontinue. They then subdivided the group of caffeine users into those whose caffeine intake increased, decreased, or stayed the same. Transcranial Doppler testing was performed in all subgroups.

The investigators found a lower BHI-PCA, or decrease in vasodilatory function, in the subgroups that remained on caffeine. Those who stopped caffeine had improvement in this metric, showing the possible reversibility that discontinuation of caffeine can have. It remains unclear precisely how caffeine is vasoactive, and the effects may be via adenosine receptors, endothelial function, neurotransmitter production, or regulation of the autonomic nervous system. The long-term vascular effects of caffeine are unknown, but they do appear to be reversible after a 3 month period.

Migraine, and especially migraine with aura, is well known as a vascular risk factor. The presence of migraine increases the odds ratio of stroke, myocardial ischemia, deep vein thrombosis and other vascular events significantly. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends avoiding the use of any estrogen containing medication in the presence of migraine, due to estrogen itself being a pro-thrombotic hormone. The precise mechanism that leads to this increased risk is unknown.

This study investigated the connection between migraine and large artery atherosclerosis (LAA). This group observed 415 consecutive patients aged 18-54 who presented for a first time ischemic stroke (other neurovascular events, such as cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage with secondary ischemia and transient ischemic attacks, were excluded). Data regarding these patient’s risks factors was collected and analyzed including elevated body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia.

All patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as either magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA), and duplex ultrasound confirmed the images. Atherosclerosis was classified using a standardized system (ASCOD: atherosclerosis, small-vessel disease, cardiac pathology, other causes, and dissection) that grades atheroslerotic lesions on a 0-3 scale.

The results may be considered counterintuitive. The presence of migraine was negatively associated with the presence of LAA: a history of migraine did not increase the risk of atherosclerosis. This was even the case when controlling for the traditional vascular risk factors. The authors theorize that likely the association between migraine and stroke and other vascular events is not related to atherosclerosis and may be due to other causes.

A genome-wide association study recently identified a specific polymorphism that was shared by migraine and coronary artery disease. But just like this study, the people with migraine had a negative association with coronary artery disease. If people with migraine do develop stroke or other vascular phenomena they typically present younger and healthier, and this may be why this negative correlation exists.

References

- Sherafat M et al. The preventive effect of the combination of atorvastatin and nortriptyline in migraine-type headache: a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2022 (Jan 17).

- Gil Y-E et al. Effect of caffeine and caffeine cessation on cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with migraine. Headache. 2022;62(2):169-75 (Feb 3).

- Gollion C et al. Migraine and large artery atherosclerosis in young adults with ischemic stroke. Headache. 2022;62(2):191-7 (Feb 5).

What's your diagnosis?

Mucous membrane pemphigoid with esophageal web stricture.

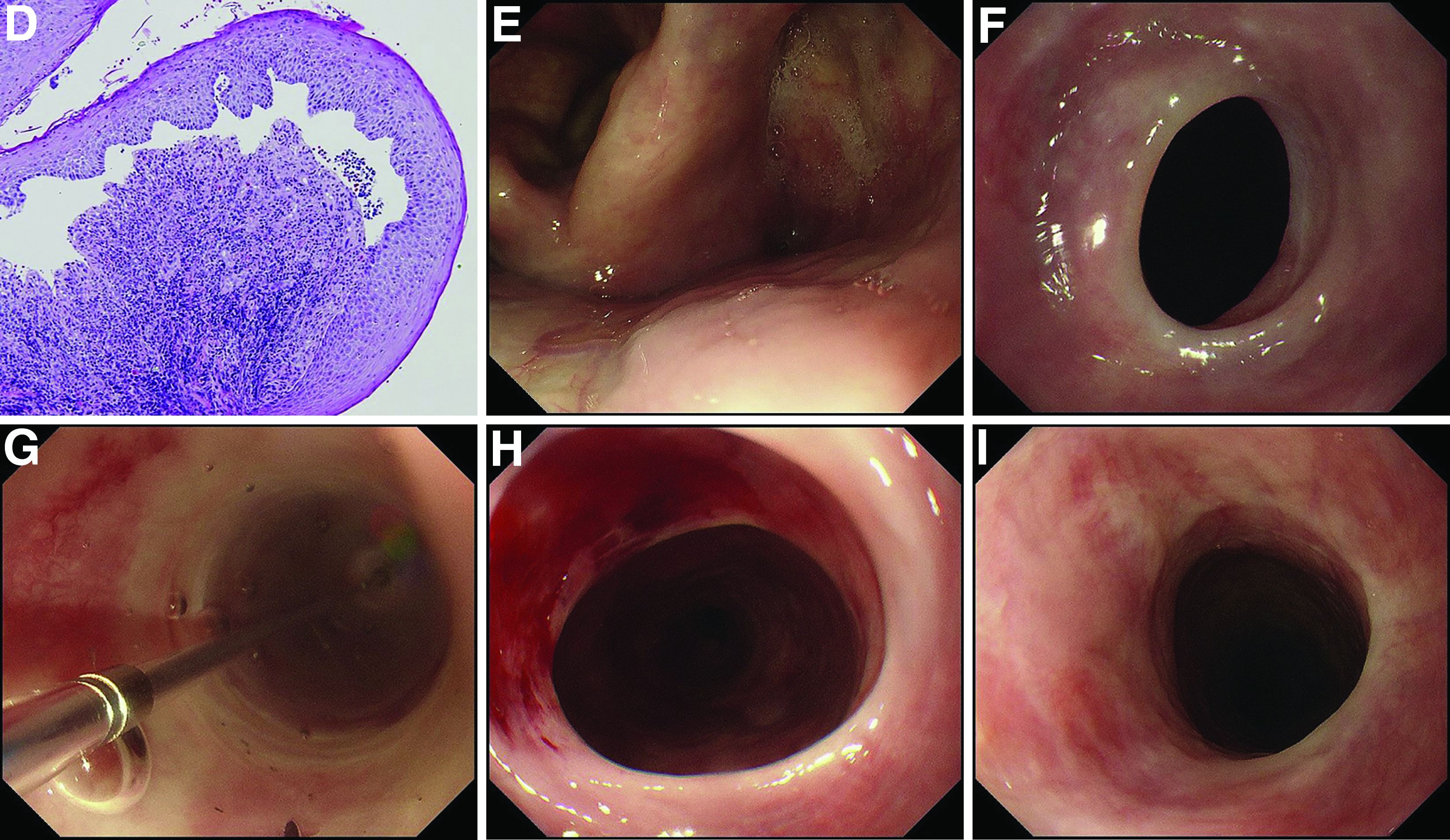

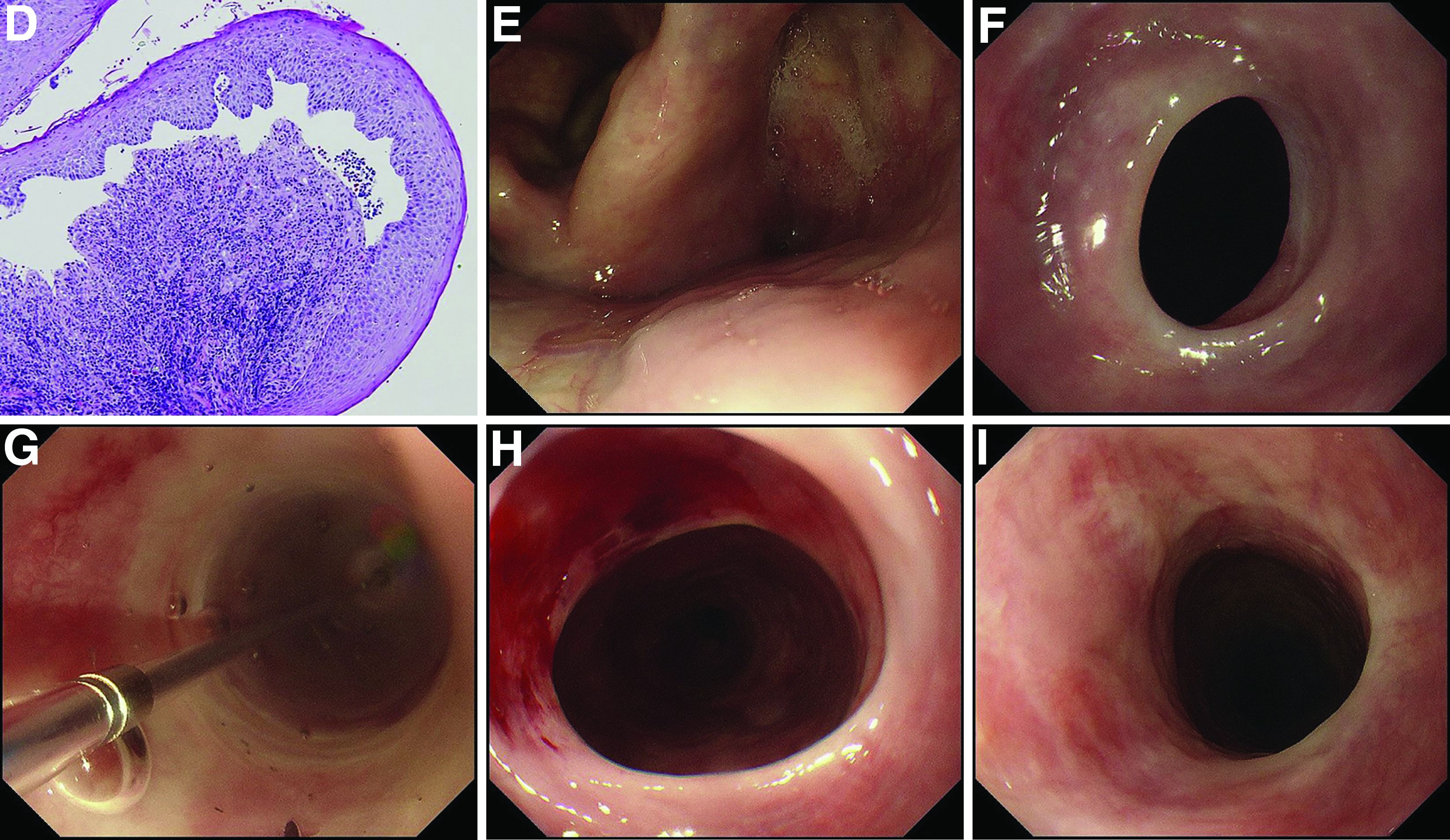

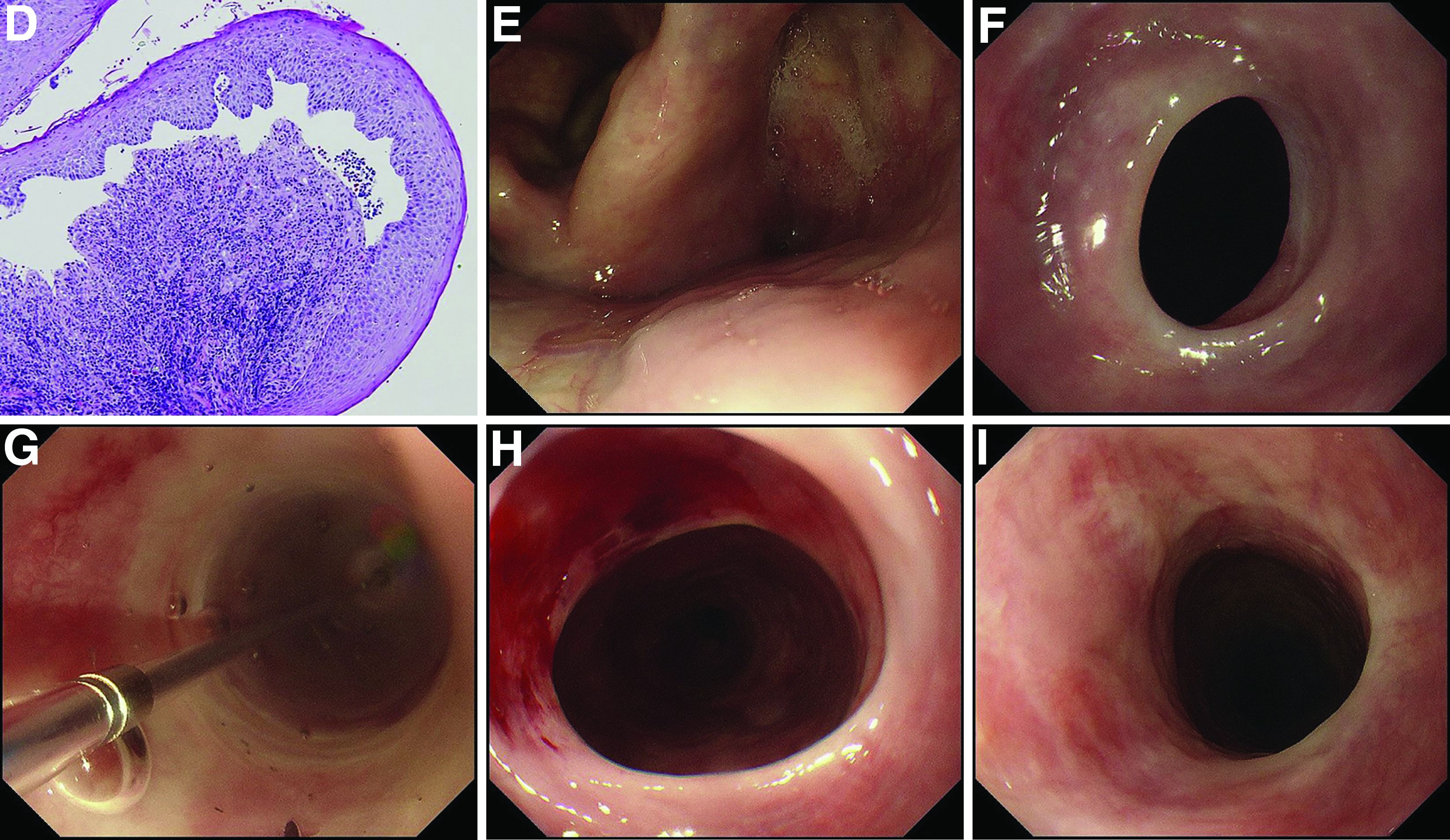

Additional laboratory examination showed that his serum anti-BP180 antibody level was high (11.7 U/mL; normal range, <9.0 U/mL). Biopsy specimens taken from the laryngopharyngeal erosion showed subepithelial blister formation and it was consistent with pemphigoid pathologically (Figure D). He did not have cutaneous lesions and was diagnosed with mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP). After performing endoscopic dilation, prednisolone (20 mg/d) was administered orally. Three months after starting the prednisolone treatment, follow-up endoscopy showed improvements of the laryngopharyngeal erosions (Figure E) and esophageal blister on the web. However, esophageal narrowing remained, and thus endoscopic balloon dilation was performed (Figure F-H). Three months after the dilation, the narrowing improved (Figure I).

MMP is an autoimmune blistering disease that induces the formation of mucous membrane subepithelial bullae. Basement membrane zone components such as collagen XVII (also known as BP180) are targets of autoantibodies in MMP. Symptomatic esophageal involvement affects 5.4% of patients with MMP and dysphagia is the most frequent symptom.1 Endoscopic findings include erosion, web stricture, subepithelial hematomas, and scars.2,3 Endoscopic dilation is sometimes necessary for the treatment of severe esophageal strictures.1

References

1. Zehou O et al. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177(4):1074-85.

2. Sallout H et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Sep;52(3):429-33.

3. Gaspar R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Aug;86(2):400-2.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid with esophageal web stricture.

Additional laboratory examination showed that his serum anti-BP180 antibody level was high (11.7 U/mL; normal range, <9.0 U/mL). Biopsy specimens taken from the laryngopharyngeal erosion showed subepithelial blister formation and it was consistent with pemphigoid pathologically (Figure D). He did not have cutaneous lesions and was diagnosed with mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP). After performing endoscopic dilation, prednisolone (20 mg/d) was administered orally. Three months after starting the prednisolone treatment, follow-up endoscopy showed improvements of the laryngopharyngeal erosions (Figure E) and esophageal blister on the web. However, esophageal narrowing remained, and thus endoscopic balloon dilation was performed (Figure F-H). Three months after the dilation, the narrowing improved (Figure I).

MMP is an autoimmune blistering disease that induces the formation of mucous membrane subepithelial bullae. Basement membrane zone components such as collagen XVII (also known as BP180) are targets of autoantibodies in MMP. Symptomatic esophageal involvement affects 5.4% of patients with MMP and dysphagia is the most frequent symptom.1 Endoscopic findings include erosion, web stricture, subepithelial hematomas, and scars.2,3 Endoscopic dilation is sometimes necessary for the treatment of severe esophageal strictures.1

References

1. Zehou O et al. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177(4):1074-85.

2. Sallout H et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Sep;52(3):429-33.

3. Gaspar R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Aug;86(2):400-2.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid with esophageal web stricture.

Additional laboratory examination showed that his serum anti-BP180 antibody level was high (11.7 U/mL; normal range, <9.0 U/mL). Biopsy specimens taken from the laryngopharyngeal erosion showed subepithelial blister formation and it was consistent with pemphigoid pathologically (Figure D). He did not have cutaneous lesions and was diagnosed with mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP). After performing endoscopic dilation, prednisolone (20 mg/d) was administered orally. Three months after starting the prednisolone treatment, follow-up endoscopy showed improvements of the laryngopharyngeal erosions (Figure E) and esophageal blister on the web. However, esophageal narrowing remained, and thus endoscopic balloon dilation was performed (Figure F-H). Three months after the dilation, the narrowing improved (Figure I).

MMP is an autoimmune blistering disease that induces the formation of mucous membrane subepithelial bullae. Basement membrane zone components such as collagen XVII (also known as BP180) are targets of autoantibodies in MMP. Symptomatic esophageal involvement affects 5.4% of patients with MMP and dysphagia is the most frequent symptom.1 Endoscopic findings include erosion, web stricture, subepithelial hematomas, and scars.2,3 Endoscopic dilation is sometimes necessary for the treatment of severe esophageal strictures.1

References

1. Zehou O et al. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Oct;177(4):1074-85.

2. Sallout H et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Sep;52(3):429-33.

3. Gaspar R et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 Aug;86(2):400-2.

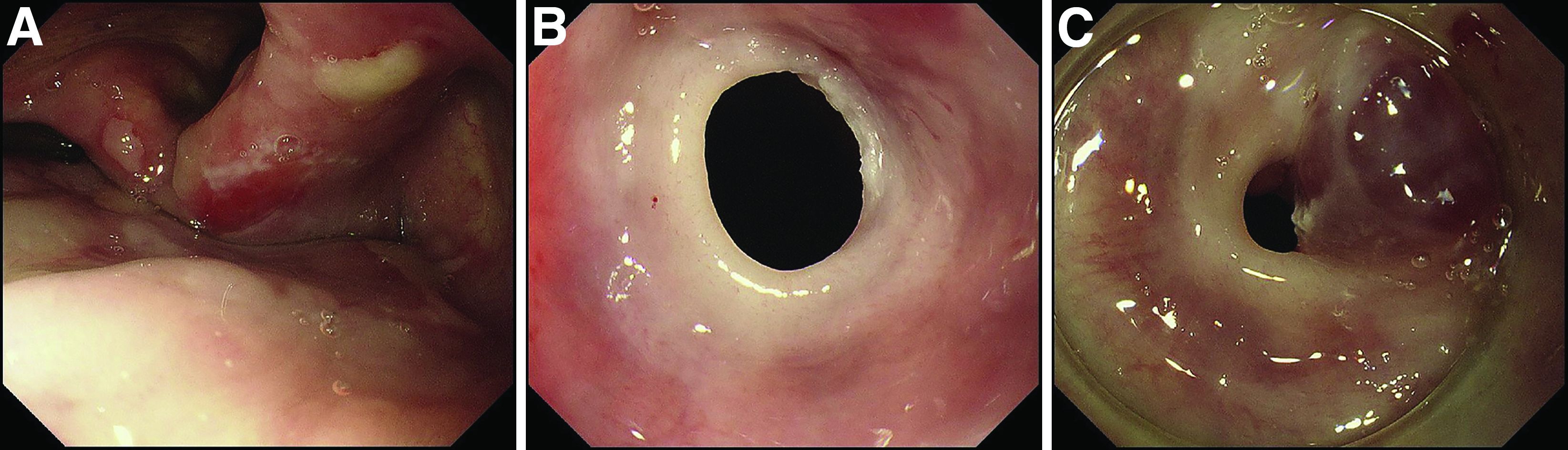

A 70-year-old man with a history of rectal cancer was referred to our clinic for chronic dysphagia and odynophagia. He did not have fevers or an allergic history. Physical examination was unremarkable except for multiple erosions in the oral cavity. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed multiple erosions in the palate and laryngopharynx (Figure A), a web stricture in the cervical esophagus (Figure B), and multiple scars in the thoracic esophagus.

Laboratory examination showed normal results including a normal white blood cell count (8010/mcL; eosinophils 360/mcL), hemoglobin level (14.0 g/dL), mean corpuscular volume (97.8 fL), serum iron level (140 mcg/dL), and ferritin level (50.5 mg/L). His dysphagia gradually worsened and he finally could not take pills nor solid food. Two weeks after the first endoscopy, a second endoscopic examination was performed and it showed exacerbation of esophageal stricture and appearance of a bloody blister (Figure C).

What is the diagnosis?

Previously published in Gastroenterology

Safe abdominal laparoscopic entry

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

Nasal microbiota show promise as polyp predictor

A study of the nasal microbiome helped researchers predict recurrent polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis patients with more than 90% accuracy, based on data from 85 individuals.

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has a significant impact on patient quality of life, but the underlying mechanism of the disease has not been well studied, and treatment options remain limited, wrote Yan Zhao, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and study coauthors.

Previous research has shown that nasal microbiome composition differs in patients with and without asthma, and some studies suggest that changes in microbiota could contribute to CRSwNP, the authors wrote. The researchers wondered if features of the nasal microbiome can predict the recurrence of nasal polyps after endoscopic sinus surgery and serve as a potential treatment target.

In a study in Allergy, the researchers examined nasal swab samples from 85 adults with CRSwNP who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery between August 2014 and March 2016 at a single center in China. The researchers performed bacterial analysis and gene sequencing on all samples.

The patients ranged in age from 18-73 years, with a mean age of 46 years, and included 64 men and 21 women. The primary outcome was recurrence of polyps. Of the total, 39 individuals had recurrence, and 46 did not.

When the researchers compared microbiota from swab samples of recurrent and nonrecurrent patients, they found differences in composition based on bacterial genus abundance. “Campylobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aggregatibacter, among others, were more abundant in swabs from CRSwNP recurrence samples, whereas Actinobacillus, Gemella, and Moraxella were more abundant in non-recurrence samples,” they wrote.

The researchers then tested their theory that distinct nasal microbiota could be a predictive marker of risk for future nasal polyp recurrence. They used a training set of 48 samples and constructed models from nasal microbiota alone, clinical features alone, and both together.

The regression model identified Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Moryella, Aggregatibacter, Butyrivibrio, Shewanella, Pseudoxanthomonas, Friedmanniella, Limnobacter, and Curvibacter as the most important taxa that distinguished recurrence from nonrecurrence in the specimens. When the model was validated, the area under the curve was 0.914, yielding a predictor of nasal polyp recurrence with 91.4% accuracy.

“It is highly likely that proteins, nucleic acids, and other small molecules produced by nasal microbiota are associated with the progression of CRSwNP,” the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Further, the nasal microbiota could maintain a stable community environment through the secretion of various chemical compounds and/or inflammatory factors, thus playing a central role in the development of CRSwNP.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the analysis of nasal flora only at the genus level in the screening phase, the use only of bioinformatic analysis for recurrence prediction, and the inclusion only of subjects from a single center, the researchers noted. Future studies should combine predictors to increase accuracy and include deeper sequencing, they said. However, the results support data from previous studies and suggest a strategy to meet the need for predictors of recurrence in CRSwNP, they concluded.

“There is a critical need to understand the role of the upper airway microbiome in different phenotypes of CRS,” said Emily K. Cope, PhD, assistant director at the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in an interview. “This was one of the first studies to evaluate the predictive power of the microbiome in recurrence of a common CRS phenotype – CRS with nasal polyps,” she said. “Importantly, the researchers were able to predict recurrence of polyps prior to the disease manifestation,” she noted.

“Given the nascent state of current upper airway microbiome research, I was surprised that they were able to predict polyp recurrence prior to disease manifestation,” Dr. Cope said. “This is exciting, and I can imagine a future where we use microbiome data to understand risk for disease.”

What is the take-home message for clinicians? Although the immediate clinical implications are limited, Dr. Cope expressed enthusiasm for additional research. “At this point, there’s not a lot we can do without validation studies, but this study is promising. I hope we can understand the mechanism that an altered microbiome might drive (or be a result of) polyposis,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the program for the Changjiang scholars and innovative research team, the Beijing Bai-Qian-Wan talent project, the Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project, the National Science and Technology Major Project, and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Cope disclosed no financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of the nasal microbiome helped researchers predict recurrent polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis patients with more than 90% accuracy, based on data from 85 individuals.

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has a significant impact on patient quality of life, but the underlying mechanism of the disease has not been well studied, and treatment options remain limited, wrote Yan Zhao, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and study coauthors.

Previous research has shown that nasal microbiome composition differs in patients with and without asthma, and some studies suggest that changes in microbiota could contribute to CRSwNP, the authors wrote. The researchers wondered if features of the nasal microbiome can predict the recurrence of nasal polyps after endoscopic sinus surgery and serve as a potential treatment target.

In a study in Allergy, the researchers examined nasal swab samples from 85 adults with CRSwNP who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery between August 2014 and March 2016 at a single center in China. The researchers performed bacterial analysis and gene sequencing on all samples.

The patients ranged in age from 18-73 years, with a mean age of 46 years, and included 64 men and 21 women. The primary outcome was recurrence of polyps. Of the total, 39 individuals had recurrence, and 46 did not.

When the researchers compared microbiota from swab samples of recurrent and nonrecurrent patients, they found differences in composition based on bacterial genus abundance. “Campylobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aggregatibacter, among others, were more abundant in swabs from CRSwNP recurrence samples, whereas Actinobacillus, Gemella, and Moraxella were more abundant in non-recurrence samples,” they wrote.

The researchers then tested their theory that distinct nasal microbiota could be a predictive marker of risk for future nasal polyp recurrence. They used a training set of 48 samples and constructed models from nasal microbiota alone, clinical features alone, and both together.

The regression model identified Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Moryella, Aggregatibacter, Butyrivibrio, Shewanella, Pseudoxanthomonas, Friedmanniella, Limnobacter, and Curvibacter as the most important taxa that distinguished recurrence from nonrecurrence in the specimens. When the model was validated, the area under the curve was 0.914, yielding a predictor of nasal polyp recurrence with 91.4% accuracy.

“It is highly likely that proteins, nucleic acids, and other small molecules produced by nasal microbiota are associated with the progression of CRSwNP,” the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Further, the nasal microbiota could maintain a stable community environment through the secretion of various chemical compounds and/or inflammatory factors, thus playing a central role in the development of CRSwNP.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the analysis of nasal flora only at the genus level in the screening phase, the use only of bioinformatic analysis for recurrence prediction, and the inclusion only of subjects from a single center, the researchers noted. Future studies should combine predictors to increase accuracy and include deeper sequencing, they said. However, the results support data from previous studies and suggest a strategy to meet the need for predictors of recurrence in CRSwNP, they concluded.

“There is a critical need to understand the role of the upper airway microbiome in different phenotypes of CRS,” said Emily K. Cope, PhD, assistant director at the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in an interview. “This was one of the first studies to evaluate the predictive power of the microbiome in recurrence of a common CRS phenotype – CRS with nasal polyps,” she said. “Importantly, the researchers were able to predict recurrence of polyps prior to the disease manifestation,” she noted.

“Given the nascent state of current upper airway microbiome research, I was surprised that they were able to predict polyp recurrence prior to disease manifestation,” Dr. Cope said. “This is exciting, and I can imagine a future where we use microbiome data to understand risk for disease.”

What is the take-home message for clinicians? Although the immediate clinical implications are limited, Dr. Cope expressed enthusiasm for additional research. “At this point, there’s not a lot we can do without validation studies, but this study is promising. I hope we can understand the mechanism that an altered microbiome might drive (or be a result of) polyposis,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the program for the Changjiang scholars and innovative research team, the Beijing Bai-Qian-Wan talent project, the Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project, the National Science and Technology Major Project, and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Cope disclosed no financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of the nasal microbiome helped researchers predict recurrent polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis patients with more than 90% accuracy, based on data from 85 individuals.

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) has a significant impact on patient quality of life, but the underlying mechanism of the disease has not been well studied, and treatment options remain limited, wrote Yan Zhao, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and study coauthors.

Previous research has shown that nasal microbiome composition differs in patients with and without asthma, and some studies suggest that changes in microbiota could contribute to CRSwNP, the authors wrote. The researchers wondered if features of the nasal microbiome can predict the recurrence of nasal polyps after endoscopic sinus surgery and serve as a potential treatment target.

In a study in Allergy, the researchers examined nasal swab samples from 85 adults with CRSwNP who underwent endoscopic sinus surgery between August 2014 and March 2016 at a single center in China. The researchers performed bacterial analysis and gene sequencing on all samples.

The patients ranged in age from 18-73 years, with a mean age of 46 years, and included 64 men and 21 women. The primary outcome was recurrence of polyps. Of the total, 39 individuals had recurrence, and 46 did not.

When the researchers compared microbiota from swab samples of recurrent and nonrecurrent patients, they found differences in composition based on bacterial genus abundance. “Campylobacter, Bdellovibrio, and Aggregatibacter, among others, were more abundant in swabs from CRSwNP recurrence samples, whereas Actinobacillus, Gemella, and Moraxella were more abundant in non-recurrence samples,” they wrote.

The researchers then tested their theory that distinct nasal microbiota could be a predictive marker of risk for future nasal polyp recurrence. They used a training set of 48 samples and constructed models from nasal microbiota alone, clinical features alone, and both together.

The regression model identified Porphyromonas, Bacteroides, Moryella, Aggregatibacter, Butyrivibrio, Shewanella, Pseudoxanthomonas, Friedmanniella, Limnobacter, and Curvibacter as the most important taxa that distinguished recurrence from nonrecurrence in the specimens. When the model was validated, the area under the curve was 0.914, yielding a predictor of nasal polyp recurrence with 91.4% accuracy.

“It is highly likely that proteins, nucleic acids, and other small molecules produced by nasal microbiota are associated with the progression of CRSwNP,” the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Further, the nasal microbiota could maintain a stable community environment through the secretion of various chemical compounds and/or inflammatory factors, thus playing a central role in the development of CRSwNP.”

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the analysis of nasal flora only at the genus level in the screening phase, the use only of bioinformatic analysis for recurrence prediction, and the inclusion only of subjects from a single center, the researchers noted. Future studies should combine predictors to increase accuracy and include deeper sequencing, they said. However, the results support data from previous studies and suggest a strategy to meet the need for predictors of recurrence in CRSwNP, they concluded.

“There is a critical need to understand the role of the upper airway microbiome in different phenotypes of CRS,” said Emily K. Cope, PhD, assistant director at the Pathogen and Microbiome Institute, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, in an interview. “This was one of the first studies to evaluate the predictive power of the microbiome in recurrence of a common CRS phenotype – CRS with nasal polyps,” she said. “Importantly, the researchers were able to predict recurrence of polyps prior to the disease manifestation,” she noted.

“Given the nascent state of current upper airway microbiome research, I was surprised that they were able to predict polyp recurrence prior to disease manifestation,” Dr. Cope said. “This is exciting, and I can imagine a future where we use microbiome data to understand risk for disease.”

What is the take-home message for clinicians? Although the immediate clinical implications are limited, Dr. Cope expressed enthusiasm for additional research. “At this point, there’s not a lot we can do without validation studies, but this study is promising. I hope we can understand the mechanism that an altered microbiome might drive (or be a result of) polyposis,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the program for the Changjiang scholars and innovative research team, the Beijing Bai-Qian-Wan talent project, the Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project, the National Science and Technology Major Project, and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Cope disclosed no financial conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Legionnaires’ disease shows steady increase in U.S. over 15+ years

Legionnaires’ disease (LD) in the United States appears to be on an upswing that started in 2003, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The reasons for this increased incidence are unclear, the researchers write in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“The findings revealed a rising national trend in cases, widening racial disparities between Black or African American persons and White persons, and an increasing geographic focus in the Middle Atlantic, the East North Central, and New England,” lead author Albert E. Barskey, MPH, an epidemiologist in CDC’s Division of Bacterial Diseases, Atlanta, said in an email.

“Legionnaires’ disease cannot be diagnosed based on clinical features alone, and studies estimate that it is underdiagnosed, perhaps by 50%,” he added. “Our findings may serve to heighten clinicians’ awareness of this severe pneumonia’s etiology, so with an earlier correct diagnosis, appropriate treatment can be rendered sooner.”

Mr. Barskey and his coauthors at CDC – mathematical statistician Gordana Derado, PhD, and epidemiologist Chris Edens, PhD – used surveillance data to investigate the incidence of LD in the U.S. over time. They compared LD incidence in 2018 with average incidence between 1992 and 2002. The incidence data, from over 80,000 LD cases, were age-standardized using the 2005 U.S. standard population as the reference.

The researchers analyzed LD data reported to CDC by the 50 states, New York City, and Washington, D.C., through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. They performed regression analysis to identify the optimal year when population parameters changed, and for most analyses, they compared 1992-2002 data with 2003-2018 data.

Legionnaires’ disease up in various groups

- The overall age-standardized average incidence grew from 0.48 per 100,000 people during 1992-2002 to 2.71 per 100,000 in 2018 (incidence risk ratio, 5.67; 95% confidence interval, 5.52-5.83).

- LD incidence more than quintupled for people over 34 years of age, with the largest relative increase in those over 85 (RR, 6.50; 95% CI, 5.82-7.27).

- Incidence in men increased slightly more (RR, 5.86; 95% CI, 5.67-6.05) than in women (RR, 5.29; 95% CI, 5.06-5.53).

- Over the years, the racial disparity in incidence grew markedly. Incidence in Black persons increased from 0.47 to 5.21 per 100,000 (RR, 11.04; 95% CI, 10.39-11.73), compared with an increase from 0.37 to 1.99 per 100,000 in White persons (RR, 5.30; 95% CI, 5.12-5.49).

- The relative increase in incidence was highest in the Northeast (RR, 7.04; 95% CI, 6.70-7.40), followed by the Midwest (RR, 6.13; 95% CI, 5.85-6.42), the South (RR, 5.97; 95% CI, 5.67-6.29), and the West (RR, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.11-3.68).

Most LD cases occurred in summer or fall, and the seasonal pattern became more pronounced over time. The average of 57.8% of cases between June and November during 1992-2002 grew to 68.9% in 2003-2018.

Although the study “was hindered by incomplete race and ethnicity data,” Mr. Barskey said, “its breadth was a strength.”

Consider legionella in your diagnosis

In an interview, Paul G. Auwaerter, MD, a professor of medicine and the clinical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said he was not surprised by the results. “CDC has been reporting increased incidence of Legionnaires’ disease from water source outbreaks over the years. As a clinician, I very much depend on epidemiologic trends to help me understand the patient in front of me.

“The key point is that there’s more of it around, so consider it in your diagnosis,” he advised.

“Physicians are increasingly beginning to consider Legionella. Because LD is difficult to diagnose by traditional methods such as culture, they may use a PCR test,” said Dr. Auwaerter, who was not involved in the study. “Legionella needs antibiotics that differ a bit from traditional antibiotics used to treat bacterial pneumonia, so a correct diagnosis can inform a more directed therapy.”

“Why the incidence is increasing is the big question, and the authors nicely outline a litany of things,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Auwaerter proposed a number of possible contributing factors to the increased incidence:

- an aging population

- aging municipal and residential water sources that may harbor more organisms

- racial disparities and poverty

- underlying conditions, including diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and some cancers

- occupations in transportation, repair, cleaning services, and construction

- weather patterns

- improved surveillance and reporting

“Why Legionella appears in some locations more than others has not been explained,” Dr. Auwaerter added. “For example, Pittsburgh always seemed to have much more Legionella than Baltimore.”

Mr. Barskey and his team are planning further research into racial disparities and links between weather and climate and Legionnaires’ disease.

The authors are employees of CDC. Dr. Auwaerter has disclosed no relevant financial realtionships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Legionnaires’ disease (LD) in the United States appears to be on an upswing that started in 2003, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The reasons for this increased incidence are unclear, the researchers write in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“The findings revealed a rising national trend in cases, widening racial disparities between Black or African American persons and White persons, and an increasing geographic focus in the Middle Atlantic, the East North Central, and New England,” lead author Albert E. Barskey, MPH, an epidemiologist in CDC’s Division of Bacterial Diseases, Atlanta, said in an email.

“Legionnaires’ disease cannot be diagnosed based on clinical features alone, and studies estimate that it is underdiagnosed, perhaps by 50%,” he added. “Our findings may serve to heighten clinicians’ awareness of this severe pneumonia’s etiology, so with an earlier correct diagnosis, appropriate treatment can be rendered sooner.”

Mr. Barskey and his coauthors at CDC – mathematical statistician Gordana Derado, PhD, and epidemiologist Chris Edens, PhD – used surveillance data to investigate the incidence of LD in the U.S. over time. They compared LD incidence in 2018 with average incidence between 1992 and 2002. The incidence data, from over 80,000 LD cases, were age-standardized using the 2005 U.S. standard population as the reference.

The researchers analyzed LD data reported to CDC by the 50 states, New York City, and Washington, D.C., through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. They performed regression analysis to identify the optimal year when population parameters changed, and for most analyses, they compared 1992-2002 data with 2003-2018 data.

Legionnaires’ disease up in various groups

- The overall age-standardized average incidence grew from 0.48 per 100,000 people during 1992-2002 to 2.71 per 100,000 in 2018 (incidence risk ratio, 5.67; 95% confidence interval, 5.52-5.83).

- LD incidence more than quintupled for people over 34 years of age, with the largest relative increase in those over 85 (RR, 6.50; 95% CI, 5.82-7.27).

- Incidence in men increased slightly more (RR, 5.86; 95% CI, 5.67-6.05) than in women (RR, 5.29; 95% CI, 5.06-5.53).

- Over the years, the racial disparity in incidence grew markedly. Incidence in Black persons increased from 0.47 to 5.21 per 100,000 (RR, 11.04; 95% CI, 10.39-11.73), compared with an increase from 0.37 to 1.99 per 100,000 in White persons (RR, 5.30; 95% CI, 5.12-5.49).

- The relative increase in incidence was highest in the Northeast (RR, 7.04; 95% CI, 6.70-7.40), followed by the Midwest (RR, 6.13; 95% CI, 5.85-6.42), the South (RR, 5.97; 95% CI, 5.67-6.29), and the West (RR, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.11-3.68).

Most LD cases occurred in summer or fall, and the seasonal pattern became more pronounced over time. The average of 57.8% of cases between June and November during 1992-2002 grew to 68.9% in 2003-2018.

Although the study “was hindered by incomplete race and ethnicity data,” Mr. Barskey said, “its breadth was a strength.”

Consider legionella in your diagnosis

In an interview, Paul G. Auwaerter, MD, a professor of medicine and the clinical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said he was not surprised by the results. “CDC has been reporting increased incidence of Legionnaires’ disease from water source outbreaks over the years. As a clinician, I very much depend on epidemiologic trends to help me understand the patient in front of me.

“The key point is that there’s more of it around, so consider it in your diagnosis,” he advised.

“Physicians are increasingly beginning to consider Legionella. Because LD is difficult to diagnose by traditional methods such as culture, they may use a PCR test,” said Dr. Auwaerter, who was not involved in the study. “Legionella needs antibiotics that differ a bit from traditional antibiotics used to treat bacterial pneumonia, so a correct diagnosis can inform a more directed therapy.”

“Why the incidence is increasing is the big question, and the authors nicely outline a litany of things,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Auwaerter proposed a number of possible contributing factors to the increased incidence:

- an aging population

- aging municipal and residential water sources that may harbor more organisms

- racial disparities and poverty

- underlying conditions, including diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and some cancers

- occupations in transportation, repair, cleaning services, and construction

- weather patterns

- improved surveillance and reporting

“Why Legionella appears in some locations more than others has not been explained,” Dr. Auwaerter added. “For example, Pittsburgh always seemed to have much more Legionella than Baltimore.”

Mr. Barskey and his team are planning further research into racial disparities and links between weather and climate and Legionnaires’ disease.

The authors are employees of CDC. Dr. Auwaerter has disclosed no relevant financial realtionships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Legionnaires’ disease (LD) in the United States appears to be on an upswing that started in 2003, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The reasons for this increased incidence are unclear, the researchers write in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“The findings revealed a rising national trend in cases, widening racial disparities between Black or African American persons and White persons, and an increasing geographic focus in the Middle Atlantic, the East North Central, and New England,” lead author Albert E. Barskey, MPH, an epidemiologist in CDC’s Division of Bacterial Diseases, Atlanta, said in an email.

“Legionnaires’ disease cannot be diagnosed based on clinical features alone, and studies estimate that it is underdiagnosed, perhaps by 50%,” he added. “Our findings may serve to heighten clinicians’ awareness of this severe pneumonia’s etiology, so with an earlier correct diagnosis, appropriate treatment can be rendered sooner.”

Mr. Barskey and his coauthors at CDC – mathematical statistician Gordana Derado, PhD, and epidemiologist Chris Edens, PhD – used surveillance data to investigate the incidence of LD in the U.S. over time. They compared LD incidence in 2018 with average incidence between 1992 and 2002. The incidence data, from over 80,000 LD cases, were age-standardized using the 2005 U.S. standard population as the reference.

The researchers analyzed LD data reported to CDC by the 50 states, New York City, and Washington, D.C., through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. They performed regression analysis to identify the optimal year when population parameters changed, and for most analyses, they compared 1992-2002 data with 2003-2018 data.

Legionnaires’ disease up in various groups

- The overall age-standardized average incidence grew from 0.48 per 100,000 people during 1992-2002 to 2.71 per 100,000 in 2018 (incidence risk ratio, 5.67; 95% confidence interval, 5.52-5.83).

- LD incidence more than quintupled for people over 34 years of age, with the largest relative increase in those over 85 (RR, 6.50; 95% CI, 5.82-7.27).

- Incidence in men increased slightly more (RR, 5.86; 95% CI, 5.67-6.05) than in women (RR, 5.29; 95% CI, 5.06-5.53).

- Over the years, the racial disparity in incidence grew markedly. Incidence in Black persons increased from 0.47 to 5.21 per 100,000 (RR, 11.04; 95% CI, 10.39-11.73), compared with an increase from 0.37 to 1.99 per 100,000 in White persons (RR, 5.30; 95% CI, 5.12-5.49).

- The relative increase in incidence was highest in the Northeast (RR, 7.04; 95% CI, 6.70-7.40), followed by the Midwest (RR, 6.13; 95% CI, 5.85-6.42), the South (RR, 5.97; 95% CI, 5.67-6.29), and the West (RR, 3.39; 95% CI, 3.11-3.68).

Most LD cases occurred in summer or fall, and the seasonal pattern became more pronounced over time. The average of 57.8% of cases between June and November during 1992-2002 grew to 68.9% in 2003-2018.

Although the study “was hindered by incomplete race and ethnicity data,” Mr. Barskey said, “its breadth was a strength.”

Consider legionella in your diagnosis

In an interview, Paul G. Auwaerter, MD, a professor of medicine and the clinical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, said he was not surprised by the results. “CDC has been reporting increased incidence of Legionnaires’ disease from water source outbreaks over the years. As a clinician, I very much depend on epidemiologic trends to help me understand the patient in front of me.

“The key point is that there’s more of it around, so consider it in your diagnosis,” he advised.

“Physicians are increasingly beginning to consider Legionella. Because LD is difficult to diagnose by traditional methods such as culture, they may use a PCR test,” said Dr. Auwaerter, who was not involved in the study. “Legionella needs antibiotics that differ a bit from traditional antibiotics used to treat bacterial pneumonia, so a correct diagnosis can inform a more directed therapy.”

“Why the incidence is increasing is the big question, and the authors nicely outline a litany of things,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Auwaerter proposed a number of possible contributing factors to the increased incidence:

- an aging population

- aging municipal and residential water sources that may harbor more organisms

- racial disparities and poverty

- underlying conditions, including diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and some cancers

- occupations in transportation, repair, cleaning services, and construction

- weather patterns

- improved surveillance and reporting

“Why Legionella appears in some locations more than others has not been explained,” Dr. Auwaerter added. “For example, Pittsburgh always seemed to have much more Legionella than Baltimore.”

Mr. Barskey and his team are planning further research into racial disparities and links between weather and climate and Legionnaires’ disease.

The authors are employees of CDC. Dr. Auwaerter has disclosed no relevant financial realtionships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Oil spill cleanup work tied to hypertension risk years later

Workers who had the highest exposure to hydrocarbons during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster had a higher risk of having a hypertension diagnosis in the years following the event, a new study suggests.

Results showed that the highest exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons during the cleanup operation was associated with a 31% higher risk of new hypertension 1-3 years later.

“What is remarkable is that we still found an increased risk of hypertension a couple of years after the cleanup had been completed. This suggests working in this environment even for a short period could have long-term health consequences,” lead author Richard Kwok, PhD, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, Dr. Kwok, a scientist at the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and colleagues estimated the levels of exposure to toxic hydrocarbons in 6,846 adults who had worked on the oil spill cleanup after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010, during which 200 million gallons of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico. They then investigated whether there was an association with the development of hypertension 1-3 years later.

“Clean-up efforts started almost immediately and lasted over a year,” Dr. Kwok noted. “In the first few months, oil flowed freely into the Gulf of Mexico which released high levels of volatile organic compounds into the air that the workers could have been exposed to. The exposures change over time because the oil becomes weathered and starts to decompose and harden. This is associated with a lower level of volatile organic compounds but can still cause damage.”

Workers involved in the cleanup may have been there for just a few days or could have spent many months at the site and would have had different exposures depending on what types of jobs they were doing, Dr. Kwok reported.

“The highest levels of exposure to total hydrocarbons would have been to those involved in the early months of the oil spill response and cleanup when the oil was flowing freely, and those who were skimming oil off the water, burning oil, handling dispersants, or involved in the decontamination of the vessels. Others who were involved in the cleanup on land or support functions would have had lower exposures,” he said.

Each worker was interviewed and asked about their activities during the cleanup operation, the location of work, and period of work. Their level of exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons (THCs) was estimated based on their self-reported activities, and when and where they worked.

Two measures of estimated cumulative THC were calculated: cumulative maximum daily exposure, which summed the maximum daily THC exposure level, and cumulative mean exposure, which summed the mean daily exposure levels. These THC values were categorized into quintiles based on the exposure distribution among workers.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were collected for the workers during home exams from 2011 to 2013 using automated oscillometric monitors. Newly detected hypertension was defined as either antihypertensive medication use or elevated blood pressure since the spill.

Results showed a clear dose relationship between the level of THC exposure and the development of hypertension at follow-up.

Similar results were seen for the relationship between cumulative mean THC exposure levels and the development of hypertension.

Despite the limitations of accurately estimating THC exposure, Dr. Kwok believes the results are real. “We looked at many different covariates including smoking, education, gender, race, ethnicity, and body mass index, but even after controlling for all these we still saw an association between the amount of exposure to THC and risk of hypertension.”

But the risk of developing hypertension did appear to be greater in those individuals with other risk factors for hypertension such as high body mass index or smokers. “There seems to be a combined effect,” Dr. Kwok said.

He pointed out that, while previous studies have shown possible health effects related to THC exposure on an acute basis, in this study, the effect on blood pressure was still evident years after the exposure had ended.

Other occupational studies have looked at people in jobs that have had longer exposures to volatile organic compounds such as taxi drivers, but this is one of the first to look at the long-term effect of a more limited period of exposure, he added.

“Our results suggest that the damage caused by THCs is not just an acute effect, but is still there several years later,” Dr. Kwok commented.

He says he hoped this study will raise awareness of the health hazards to workers involved in future oil spills. “Our results suggest that we need better protective equipment and monitoring of workers and the local community with longer-term follow up for health outcomes.”

Another analysis showed no clear differences in hypertension risk between individuals who worked on the oil spill cleanup (workers) and others who had completed required safety training but did not participate in the clean-up operation (nonworkers). Dr. Kwok suggested this may have been a result of the “healthy worker effect,” which is based on the premise that individuals able to work are healthier than those unable to work.

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The authors reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Workers who had the highest exposure to hydrocarbons during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster had a higher risk of having a hypertension diagnosis in the years following the event, a new study suggests.

Results showed that the highest exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons during the cleanup operation was associated with a 31% higher risk of new hypertension 1-3 years later.

“What is remarkable is that we still found an increased risk of hypertension a couple of years after the cleanup had been completed. This suggests working in this environment even for a short period could have long-term health consequences,” lead author Richard Kwok, PhD, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, Dr. Kwok, a scientist at the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and colleagues estimated the levels of exposure to toxic hydrocarbons in 6,846 adults who had worked on the oil spill cleanup after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010, during which 200 million gallons of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico. They then investigated whether there was an association with the development of hypertension 1-3 years later.

“Clean-up efforts started almost immediately and lasted over a year,” Dr. Kwok noted. “In the first few months, oil flowed freely into the Gulf of Mexico which released high levels of volatile organic compounds into the air that the workers could have been exposed to. The exposures change over time because the oil becomes weathered and starts to decompose and harden. This is associated with a lower level of volatile organic compounds but can still cause damage.”

Workers involved in the cleanup may have been there for just a few days or could have spent many months at the site and would have had different exposures depending on what types of jobs they were doing, Dr. Kwok reported.

“The highest levels of exposure to total hydrocarbons would have been to those involved in the early months of the oil spill response and cleanup when the oil was flowing freely, and those who were skimming oil off the water, burning oil, handling dispersants, or involved in the decontamination of the vessels. Others who were involved in the cleanup on land or support functions would have had lower exposures,” he said.

Each worker was interviewed and asked about their activities during the cleanup operation, the location of work, and period of work. Their level of exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons (THCs) was estimated based on their self-reported activities, and when and where they worked.

Two measures of estimated cumulative THC were calculated: cumulative maximum daily exposure, which summed the maximum daily THC exposure level, and cumulative mean exposure, which summed the mean daily exposure levels. These THC values were categorized into quintiles based on the exposure distribution among workers.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were collected for the workers during home exams from 2011 to 2013 using automated oscillometric monitors. Newly detected hypertension was defined as either antihypertensive medication use or elevated blood pressure since the spill.

Results showed a clear dose relationship between the level of THC exposure and the development of hypertension at follow-up.

Similar results were seen for the relationship between cumulative mean THC exposure levels and the development of hypertension.

Despite the limitations of accurately estimating THC exposure, Dr. Kwok believes the results are real. “We looked at many different covariates including smoking, education, gender, race, ethnicity, and body mass index, but even after controlling for all these we still saw an association between the amount of exposure to THC and risk of hypertension.”

But the risk of developing hypertension did appear to be greater in those individuals with other risk factors for hypertension such as high body mass index or smokers. “There seems to be a combined effect,” Dr. Kwok said.

He pointed out that, while previous studies have shown possible health effects related to THC exposure on an acute basis, in this study, the effect on blood pressure was still evident years after the exposure had ended.

Other occupational studies have looked at people in jobs that have had longer exposures to volatile organic compounds such as taxi drivers, but this is one of the first to look at the long-term effect of a more limited period of exposure, he added.

“Our results suggest that the damage caused by THCs is not just an acute effect, but is still there several years later,” Dr. Kwok commented.

He says he hoped this study will raise awareness of the health hazards to workers involved in future oil spills. “Our results suggest that we need better protective equipment and monitoring of workers and the local community with longer-term follow up for health outcomes.”

Another analysis showed no clear differences in hypertension risk between individuals who worked on the oil spill cleanup (workers) and others who had completed required safety training but did not participate in the clean-up operation (nonworkers). Dr. Kwok suggested this may have been a result of the “healthy worker effect,” which is based on the premise that individuals able to work are healthier than those unable to work.

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. The authors reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Workers who had the highest exposure to hydrocarbons during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster had a higher risk of having a hypertension diagnosis in the years following the event, a new study suggests.

Results showed that the highest exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons during the cleanup operation was associated with a 31% higher risk of new hypertension 1-3 years later.

“What is remarkable is that we still found an increased risk of hypertension a couple of years after the cleanup had been completed. This suggests working in this environment even for a short period could have long-term health consequences,” lead author Richard Kwok, PhD, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, Dr. Kwok, a scientist at the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and colleagues estimated the levels of exposure to toxic hydrocarbons in 6,846 adults who had worked on the oil spill cleanup after the Deepwater Horizon disaster in 2010, during which 200 million gallons of oil spilled into the Gulf of Mexico. They then investigated whether there was an association with the development of hypertension 1-3 years later.

“Clean-up efforts started almost immediately and lasted over a year,” Dr. Kwok noted. “In the first few months, oil flowed freely into the Gulf of Mexico which released high levels of volatile organic compounds into the air that the workers could have been exposed to. The exposures change over time because the oil becomes weathered and starts to decompose and harden. This is associated with a lower level of volatile organic compounds but can still cause damage.”

Workers involved in the cleanup may have been there for just a few days or could have spent many months at the site and would have had different exposures depending on what types of jobs they were doing, Dr. Kwok reported.

“The highest levels of exposure to total hydrocarbons would have been to those involved in the early months of the oil spill response and cleanup when the oil was flowing freely, and those who were skimming oil off the water, burning oil, handling dispersants, or involved in the decontamination of the vessels. Others who were involved in the cleanup on land or support functions would have had lower exposures,” he said.

Each worker was interviewed and asked about their activities during the cleanup operation, the location of work, and period of work. Their level of exposure to total petroleum hydrocarbons (THCs) was estimated based on their self-reported activities, and when and where they worked.

Two measures of estimated cumulative THC were calculated: cumulative maximum daily exposure, which summed the maximum daily THC exposure level, and cumulative mean exposure, which summed the mean daily exposure levels. These THC values were categorized into quintiles based on the exposure distribution among workers.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were collected for the workers during home exams from 2011 to 2013 using automated oscillometric monitors. Newly detected hypertension was defined as either antihypertensive medication use or elevated blood pressure since the spill.

Results showed a clear dose relationship between the level of THC exposure and the development of hypertension at follow-up.

Similar results were seen for the relationship between cumulative mean THC exposure levels and the development of hypertension.