User login

AGA helps break down barriers to CRC screening

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

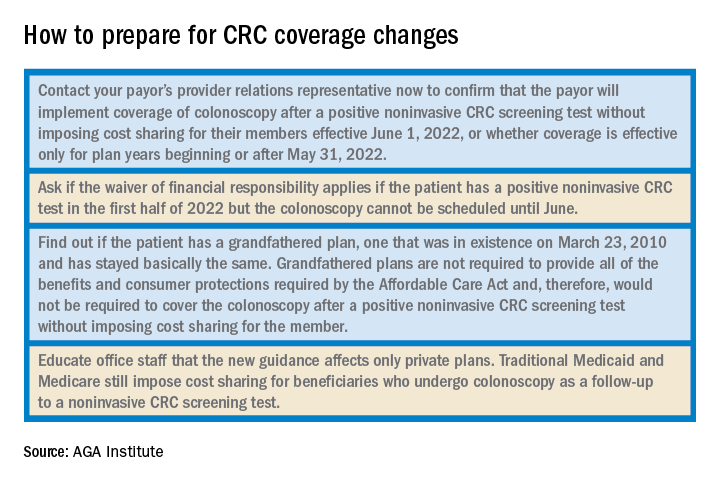

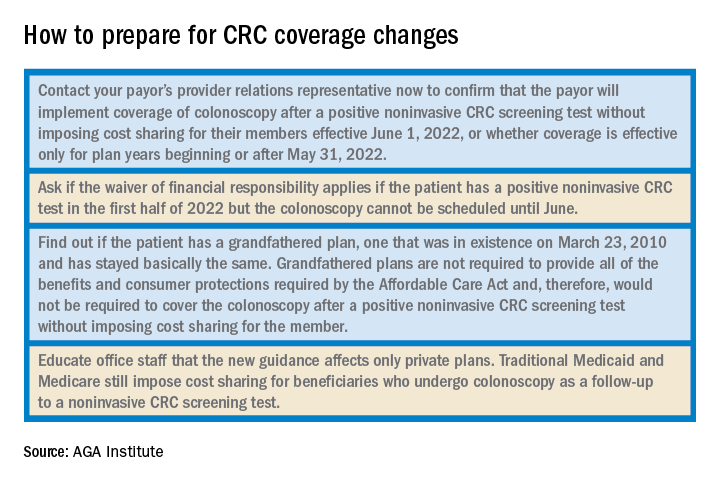

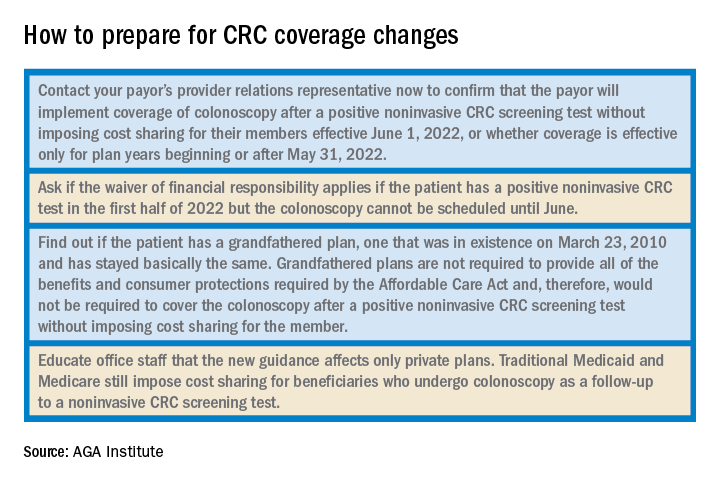

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

The new year has already marked major progress for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening with the implementation of the Removing Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Act by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which will protect Medicare beneficiaries from an unexpected bill if a polyp is detected and removed during a screening colonoscopy, as well as new guidance from the federal government requiring private insurers to cover colonoscopy as a follow-up to a noninvasive CRC screening test without imposing cost sharing for patients.

The American Gastroenterological Association is strongly committed to reducing the incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer. There is strong evidence that CRC screening is effective, but only 65% of eligible individuals have been screened. A. Mark Fendrick, MD, and colleagues recently found that cost sharing for CRC screening occurred in 48.2% of patients with commercial insurance and 77.9% of patients with Medicare coverage. The elimination of these barriers to CRC screening should improve adherence and reduce the burden of CRC.

As one of AGA President John M. Inadomi’s initiatives, the AGA created the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee in 2021 to develop AGA Position Statements that highlight the continuum of CRC screening and identify barriers, as well as work with stakeholders to eliminate known barriers. Chaired by former AGA President, David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, and with public policy guidance from Kathleen Teixeira, AGA Vice President of Public Policy and Government Affairs at the AGA, the committee identified that, at that time, colonoscopies after positive stool tests had often been considered “diagnostic” and, therefore, were not covered in full the way a preventive screening is required to be covered by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The committee recognized that copays and deductibles are barriers to CRC screening and contribute to health inequity and socio-economic disparities. Noninvasive screening should be considered a part of programs with multiple steps, all of which – including follow-up colonoscopy if the test is positive – should be covered by payers without cost sharing as part of the screening continuum. Further, screening with high-quality colonoscopy should be covered by payers without cost sharing, consistent with the aims of the ACA. The committee recommended that the full cost of screening, including the bowel prep, facility and professional fees, anesthesia, and pathology, should be covered by payers without cost sharing.

Over the past decade, the AGA and other organizations have spent countless hours advocating for closing the gap. In September 2021, Dr. Inadomi and Dr. Lieberman, along with the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and Fight CRC, met with Assistant Secretary of Labor, Ali Khawar, and representatives from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services and U.S. Department of Treasury to request they direct private health plans to cover colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive CRC screening. In January 2022, guidance from the United States Department of Labor, HHS, and the USDT clarified that private insurance plans must cover follow-up colonoscopies after a positive noninvasive stool test. In the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Affordable Care Act Implementation, Part 51, the departments affirmed that a plan or issuer must cover and may not impose cost sharing with respect to a colonoscopy conducted after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test for colorectal cancer for individuals described in a U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation from May 18, 2021. As stated in that USPSTF recommendation, the follow-up colonoscopy is an integral part of the preventive screening without which the screening would not be complete . The follow-up colonoscopy after a positive noninvasive stool-based screening test or direct visualization screening test is therefore required to be covered without cost sharing in accordance with the requirements of Public Health Service Act section 2713 and its implementing regulations.

Plans and issuers must provide coverage without cost sharing for plan or policy years beginning on or after May 31, 2022. While this new guidance will expand coverage of follow-up colonoscopies to many more individuals nationwide, including individuals who have coverage through Medicaid expansion, it does not apply to traditional Medicaid and Medicare plans.

The members of the CRC Screening Continuum Executive Committee includes Dr. Brill and Lieberman, as well as Uri Ladabaum, MD; Larry Kim, MD; Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil; Caitlin Murphy, MD; and Richard Wender, MD. Disclosures are on file with the AGA National Office.

Dr. Brill is chief medical officer, Predictive Health, Phoenix. Dr. Lieberman is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as well as a past president of the AGA. Dr. Brill discloses consulting for Accomplish Health, Alimetry, Allara Health, AnX Robotica, Arch Therapeutics, Biotax, Boomerang Medical, Brightline, Calyx, Capsovision, Check Cap, Clexio, Curology, Docbot, Echosens, Endogastric Solutions, evoEndo, Family First, FDNA, Food Marble, Freespira, Gala Therapeutics, Glaukos, gTech Medical, Gynesonics, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Innovative Health Solutions, IronRod Health, Johnson & Johnson, Lantheus, LeMinou, Lumen, Mainstay Medical, MaternaMed, Medtronic, Mightier, Motus GI, OncoSil Medical, Palette Life Sciences, Perry Health, Perspectum, Red Ventures, Reflexion, Respira Labs, Salaso, Smith+Nephew, SonarMD, Stage Zero Life Sciences, Steris, Sword Health, Tabula Rosa Health Care, Ultrasight, Vertos Medical, WL Gore, and holds options/warrants in Accomplish Health, AnX Robotica, Capsovision, Donsini Health, Hbox, Hello Heart, HyGIeaCare, Restech, Perry Health, StageZero Life Sciences, SonarMD. Dr. Lieberman is a consultant to Geneoscopy.

USPSTF releases updated guidance on asymptomatic A-fib

In January 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its 2018 statement on screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) in older adults (≥ 50 years).1,2 The supporting evidence review sought to include data on newer screening methods, such as automated blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters, and consumer-facing devices (eg, smartphone apps). However, ultimately, the recommendation did not change; it remains an “I” statement, meaning the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AF in asymptomatic adults with no signs or symptoms.1,2

Atrial fibrillation and stroke. AF is common, and the prevalence increases with age: from < 0.2% in those younger than 55 years to about 10% for those ages 85 and older.1,2 AF is a strong risk factor for stroke, and when detected, stroke prevention measures—either restoration of normal rhythm or use of anticoagulants—can be implemented as appropriate.

The available evidence for the effectiveness of stroke prevention comes from patients with AF that was detected because of symptoms or pulse palpation during routine care. It is not known if screening asymptomatic adults using electrocardiography, or newer electronic devices that detect irregular heartbeats, achieves these same benefits—and there is the potential for harm from the use of anticoagulants.

How does this compare to other recommendations? The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association recommend active screening for AF, by pulse assessment, in those ages 65 years and older.3 This does not differ as much as it appears to from the USPSTF statement. The difference is in terminology: The USPSTF considers pulse assessment part of routine care; the other organizations call it “screening.”

What you should—and shouldn’t—do. The USPSTF states that “Clinicians should use their clinical judgement regarding whether to screen and how to screen for AF.” Any patient with signs or symptoms of AF or who is discovered to have an irregular pulse should be assessed for AF. Those found to have AF should be assessed for their risk of stroke and treated accordingly. However, attempting to find “silent” AF in those who do not have an irregular pulse on exam, by way of any screening devices, has no proven benefit.

1. USPSTF; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:360-365.

2. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation: final recommendation statement. Published January 25, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/atrial-fibrillation-screening

3. Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Hypertension. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:3754-3832. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000046

In January 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its 2018 statement on screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) in older adults (≥ 50 years).1,2 The supporting evidence review sought to include data on newer screening methods, such as automated blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters, and consumer-facing devices (eg, smartphone apps). However, ultimately, the recommendation did not change; it remains an “I” statement, meaning the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AF in asymptomatic adults with no signs or symptoms.1,2

Atrial fibrillation and stroke. AF is common, and the prevalence increases with age: from < 0.2% in those younger than 55 years to about 10% for those ages 85 and older.1,2 AF is a strong risk factor for stroke, and when detected, stroke prevention measures—either restoration of normal rhythm or use of anticoagulants—can be implemented as appropriate.

The available evidence for the effectiveness of stroke prevention comes from patients with AF that was detected because of symptoms or pulse palpation during routine care. It is not known if screening asymptomatic adults using electrocardiography, or newer electronic devices that detect irregular heartbeats, achieves these same benefits—and there is the potential for harm from the use of anticoagulants.

How does this compare to other recommendations? The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association recommend active screening for AF, by pulse assessment, in those ages 65 years and older.3 This does not differ as much as it appears to from the USPSTF statement. The difference is in terminology: The USPSTF considers pulse assessment part of routine care; the other organizations call it “screening.”

What you should—and shouldn’t—do. The USPSTF states that “Clinicians should use their clinical judgement regarding whether to screen and how to screen for AF.” Any patient with signs or symptoms of AF or who is discovered to have an irregular pulse should be assessed for AF. Those found to have AF should be assessed for their risk of stroke and treated accordingly. However, attempting to find “silent” AF in those who do not have an irregular pulse on exam, by way of any screening devices, has no proven benefit.

In January 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force updated its 2018 statement on screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) in older adults (≥ 50 years).1,2 The supporting evidence review sought to include data on newer screening methods, such as automated blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximeters, and consumer-facing devices (eg, smartphone apps). However, ultimately, the recommendation did not change; it remains an “I” statement, meaning the evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AF in asymptomatic adults with no signs or symptoms.1,2

Atrial fibrillation and stroke. AF is common, and the prevalence increases with age: from < 0.2% in those younger than 55 years to about 10% for those ages 85 and older.1,2 AF is a strong risk factor for stroke, and when detected, stroke prevention measures—either restoration of normal rhythm or use of anticoagulants—can be implemented as appropriate.

The available evidence for the effectiveness of stroke prevention comes from patients with AF that was detected because of symptoms or pulse palpation during routine care. It is not known if screening asymptomatic adults using electrocardiography, or newer electronic devices that detect irregular heartbeats, achieves these same benefits—and there is the potential for harm from the use of anticoagulants.

How does this compare to other recommendations? The American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association recommend active screening for AF, by pulse assessment, in those ages 65 years and older.3 This does not differ as much as it appears to from the USPSTF statement. The difference is in terminology: The USPSTF considers pulse assessment part of routine care; the other organizations call it “screening.”

What you should—and shouldn’t—do. The USPSTF states that “Clinicians should use their clinical judgement regarding whether to screen and how to screen for AF.” Any patient with signs or symptoms of AF or who is discovered to have an irregular pulse should be assessed for AF. Those found to have AF should be assessed for their risk of stroke and treated accordingly. However, attempting to find “silent” AF in those who do not have an irregular pulse on exam, by way of any screening devices, has no proven benefit.

1. USPSTF; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:360-365.

2. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation: final recommendation statement. Published January 25, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/atrial-fibrillation-screening

3. Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Hypertension. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:3754-3832. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000046

1. USPSTF; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327:360-365.

2. USPSTF. Screening for atrial fibrillation: final recommendation statement. Published January 25, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/atrial-fibrillation-screening

3. Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; Council on Hypertension. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:3754-3832. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000046

Dressing in blue

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

On the first Friday in March, it has become an annual tradition to dress in blue to promote colorectal cancer awareness. Twitter feeds are filled with photos of members of our gastroenterology community (sometimes entire endoscopy units!) swathed in various shades of blue. This tradition was started in the mid-2000’s by a patient diagnosed with early-onset colorectal cancer who planned a fund raiser at her daughter’s elementary school where students were encouraged to wear a blue outfit and make a $1 donation to support awareness of this deadly but preventable cancer. What was once a local effort has now grown into a national phenomenon, and a powerful opportunity for the medical community to educate patients, friends, and family regarding risk factors for colorectal cancer and the importance of timely and effective screening. But while raising awareness is vital, it is only an initial step in the complex process of optimizing delivery of screening services and improving cancer outcomes through prevention and early detection.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we report on a study from Cancer demonstrating the effectiveness of Spanish-speaking patient navigators in boosting colorectal cancer screening rates among Hispanic patients. We also highlight a quality improvement initiative at a large academic medical center demonstrating the impact of an electronic “primer” message delivered through the patient portal on screening completion rates in a mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach program. Finally, in this month’s Practice Management Toolbox column, Dr. Brill and Dr. Lieberman advise us on how to prepare for upcoming coverage changes impacting screening colonoscopy – a result of AGA’s tireless efforts to eliminate financial barriers impeding access to colorectal cancer screening.

As always, thank you for being a dedicated reader and please stay safe out there. Better days are ahead.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor in Chief

FDA approves new CAR T-cell treatment for multiple myeloma

A new treatment option for patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma who have already tried four or more therapies has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

There are already two other therapies on the market that target BCMA – another CAR T cell, idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma), which was approved by the FDA in March 2021, and a drug conjugate, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep), which was approved in August 2020.

The approval of cilta-cel was based on clinical data from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which were initially presented in December 2020 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, as reported at the time by this news organization.

The trial involved 97 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had already received a median of six previous treatments (range, three to 18), including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

“The treatment journey for the majority of patients living with multiple myeloma is a relentless cycle of remission and relapse, with fewer patients achieving a deep response as they progress through later lines of therapy,” commented Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at Mount Sinai, who was a principal investigator on the pivotal study.

“That is why I have been really excited about the results from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which has demonstrated that cilta-cel can provide deep and durable responses and long-term treatment-free intervals, even in this heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patient population,” he said.

“Today’s approval of Carvykti helps address a great unmet need for these patients,” he commented in a press release from the manufacturer.

Like other CAR T-cell therapies, ciltacabtagene autoleucel is a one-time treatment. It involves collecting blood from the patient, extracting T cells, genetically engineering them, then transfusing them back to the patient, who in the meantime has undergone conditioning.

The results from CARTITUDE-1 show that this one-time treatment resulted in deep and durable responses.

The overall response rate was 98%, and the majority of patients (78%) achieved a stringent complete response, in which physicians are unable to observe any signs or symptoms of disease via imaging or other tests after treatment.

At a median of 18 months’ follow-up, the median duration of response was 21.8 months.

“The responses in the CARTITUDE-1 study showed durability over time and resulted in the majority of heavily pretreated patients achieving deep responses after 18-month follow-up,” commented Mr. Jagannath.

“The approval of cilta-cel provides physicians an immunotherapy treatment option that offers patients an opportunity to be free from anti-myeloma therapies for a period of time,” he added.

As with other CAR T-cell therapies, there were serious side effects, and these products are available only through restricted programs under a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy.

The product information for Cartykti includes a boxed warning that mentions cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome, parkinsonism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, and prolonged and/or recurrent cytopenias.

The most common adverse reactions (reported in greater than or equal to 20% of patients) are pyrexia, CRS, hypogammaglobulinemia, hypotension, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, infections–pathogens unspecified, cough, chills, diarrhea, nausea, encephalopathy, decreased appetite, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, tachycardia, dizziness, dyspnea, edema, viral infections, coagulopathy, constipation, and vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new treatment option for patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma who have already tried four or more therapies has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

There are already two other therapies on the market that target BCMA – another CAR T cell, idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma), which was approved by the FDA in March 2021, and a drug conjugate, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep), which was approved in August 2020.

The approval of cilta-cel was based on clinical data from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which were initially presented in December 2020 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, as reported at the time by this news organization.

The trial involved 97 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had already received a median of six previous treatments (range, three to 18), including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

“The treatment journey for the majority of patients living with multiple myeloma is a relentless cycle of remission and relapse, with fewer patients achieving a deep response as they progress through later lines of therapy,” commented Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at Mount Sinai, who was a principal investigator on the pivotal study.

“That is why I have been really excited about the results from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which has demonstrated that cilta-cel can provide deep and durable responses and long-term treatment-free intervals, even in this heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patient population,” he said.

“Today’s approval of Carvykti helps address a great unmet need for these patients,” he commented in a press release from the manufacturer.

Like other CAR T-cell therapies, ciltacabtagene autoleucel is a one-time treatment. It involves collecting blood from the patient, extracting T cells, genetically engineering them, then transfusing them back to the patient, who in the meantime has undergone conditioning.

The results from CARTITUDE-1 show that this one-time treatment resulted in deep and durable responses.

The overall response rate was 98%, and the majority of patients (78%) achieved a stringent complete response, in which physicians are unable to observe any signs or symptoms of disease via imaging or other tests after treatment.

At a median of 18 months’ follow-up, the median duration of response was 21.8 months.

“The responses in the CARTITUDE-1 study showed durability over time and resulted in the majority of heavily pretreated patients achieving deep responses after 18-month follow-up,” commented Mr. Jagannath.

“The approval of cilta-cel provides physicians an immunotherapy treatment option that offers patients an opportunity to be free from anti-myeloma therapies for a period of time,” he added.

As with other CAR T-cell therapies, there were serious side effects, and these products are available only through restricted programs under a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy.

The product information for Cartykti includes a boxed warning that mentions cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome, parkinsonism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, and prolonged and/or recurrent cytopenias.

The most common adverse reactions (reported in greater than or equal to 20% of patients) are pyrexia, CRS, hypogammaglobulinemia, hypotension, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, infections–pathogens unspecified, cough, chills, diarrhea, nausea, encephalopathy, decreased appetite, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, tachycardia, dizziness, dyspnea, edema, viral infections, coagulopathy, constipation, and vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new treatment option for patients with refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma who have already tried four or more therapies has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

There are already two other therapies on the market that target BCMA – another CAR T cell, idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma), which was approved by the FDA in March 2021, and a drug conjugate, belantamab mafodotin (Blenrep), which was approved in August 2020.

The approval of cilta-cel was based on clinical data from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which were initially presented in December 2020 at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, as reported at the time by this news organization.

The trial involved 97 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma who had already received a median of six previous treatments (range, three to 18), including a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody.

“The treatment journey for the majority of patients living with multiple myeloma is a relentless cycle of remission and relapse, with fewer patients achieving a deep response as they progress through later lines of therapy,” commented Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology at Mount Sinai, who was a principal investigator on the pivotal study.

“That is why I have been really excited about the results from the CARTITUDE-1 study, which has demonstrated that cilta-cel can provide deep and durable responses and long-term treatment-free intervals, even in this heavily pretreated multiple myeloma patient population,” he said.

“Today’s approval of Carvykti helps address a great unmet need for these patients,” he commented in a press release from the manufacturer.

Like other CAR T-cell therapies, ciltacabtagene autoleucel is a one-time treatment. It involves collecting blood from the patient, extracting T cells, genetically engineering them, then transfusing them back to the patient, who in the meantime has undergone conditioning.

The results from CARTITUDE-1 show that this one-time treatment resulted in deep and durable responses.

The overall response rate was 98%, and the majority of patients (78%) achieved a stringent complete response, in which physicians are unable to observe any signs or symptoms of disease via imaging or other tests after treatment.

At a median of 18 months’ follow-up, the median duration of response was 21.8 months.

“The responses in the CARTITUDE-1 study showed durability over time and resulted in the majority of heavily pretreated patients achieving deep responses after 18-month follow-up,” commented Mr. Jagannath.

“The approval of cilta-cel provides physicians an immunotherapy treatment option that offers patients an opportunity to be free from anti-myeloma therapies for a period of time,” he added.

As with other CAR T-cell therapies, there were serious side effects, and these products are available only through restricted programs under a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy.

The product information for Cartykti includes a boxed warning that mentions cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome, parkinsonism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome, and prolonged and/or recurrent cytopenias.

The most common adverse reactions (reported in greater than or equal to 20% of patients) are pyrexia, CRS, hypogammaglobulinemia, hypotension, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, infections–pathogens unspecified, cough, chills, diarrhea, nausea, encephalopathy, decreased appetite, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, tachycardia, dizziness, dyspnea, edema, viral infections, coagulopathy, constipation, and vomiting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What is the healthiest salt for you?

When we refer to “regular table salt,” it is most commonly in the form of sodium chloride, which is also a major constituent of packaged and ultraprocessed foods.

The best approach to finding the “healthiest salt” – which really means the lowest in sodium – is to look for the amount on the label. “Sodium-free” usually indicates less than 5 mg of sodium per serving, and “low-sodium” usually means 140 mg or less per serving. In contrast, regular table salt can contain as much as 560 mg of sodium in one serving.

Other en vogue salts, such as pink Himalayan salt, sea salt, and kosher salt, are high in sodium content – like regular table salt – but because of their larger crystal size, less sodium is delivered per serving.

Most salt substitutes are reduced in sodium, with the addition of potassium chloride instead.

FDA issues guidance on reducing salt

Currently, the U.S. sodium dietary guidelines for persons older than 14 stipulate 2,300 mg/d, which is equivalent to 1 teaspoon a day. However it is estimated that the average person in the United States consumes more than this – around 3,400 mg of sodium daily.

In October 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published guidance on voluntary sodium limitations in commercially processed, packaged, and prepared food. The FDA’s short-term approach is to slowly reduce exposure to sodium in processed and restaurant food by 2025, on the basis that people will eventually get used to less salt, as has happened in the United Kingdom and other countries.

Such strategies to reduce salt intake are now being used in national programs in several countries. Many of these successful initiatives include active engagement with the food industry to reduce the amount of sodium added to processed food, as well as public awareness campaigns to alert consumers to the dangers of eating too much salt. This includes increasing potassium in manufactured foods, primarily to target hypertension and heart disease, as described by Clare Farrand, MSc, BSc, and colleagues, in the Journal of Clinical Hypertension. The authors also make several recommendations regarding salt reduction policies:

- Food manufacturers should gradually reduce sodium in food to the lowest possible levels and explore the use of potassium-based sodium replacers to reduce sodium levels even further.

- Governments should continue to monitor sodium and potassium levels in processed foods.

- Further consideration may need to be given to how best to label salt substitutes (namely potassium) in processed foods to ensure that people who may be adversely affected are aware.

- Governments should systematically monitor potassium intake at the population level, including for specific susceptible groups.

- Governments should continue to systematically monitor sodium (salt) intake and iodine intake at the population level to adjust salt iodization over time as necessary, depending on observed salt intake in specific targeted groups, to ensure that they have sufficient but not excessive iodine intakes as salt intakes are reduced.

- Governments should consider opportunities for promoting and subsidizing salt substitutes, particularly in countries where salt added during cooking or at the table is the major source of salt in the diet.

The new FDA document includes 163 subcategories of foods in its voluntary salt reduction strategy.

Salt substitutes, high blood pressure, and mortality

Lowering sodium intake is almost certainly beneficial for persons with high blood pressure. In 2020, a review in Hypertension highlighted the benefit of salt substitutes in reducing hypertension, reporting that they lower systolic blood pressure by 5.58 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.88 mm Hg.

And changes to dietary sodium intake can potentially reduce or obviate the need for medications for essential hypertension in some individuals. Although there are only a few studies on this topic, a study by Bruce Neal, MB, ChB, PhD, and colleagues, revealed a reduction in stroke, cardiovascular events, and deaths with the use of potassium-based salt substitutes.

Salt substitutes and sodium and potassium handling in the kidneys

Many studies have shown that potassium-rich salt substitutes are safe in individuals with normal kidney function, but are they safe and beneficial for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD)?

For anyone who is on a renal diet, potassium and sodium intake goals are limited according to their absolute level of kidney function.

There have been case reports of life-threatening blood potassium levels (hyperkalemia) due to potassium-rich salt substitutes in people with CKD, but no larger published studies on this topic can be found.

A diet modeling study by Rebecca Morrison and colleagues evaluated varying degrees of potassium-enriched salt substituted bread products and their impact on dietary intake in persons with CKD. They used dietary data from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011-2012 in Australia for 12,152 participants, 154 of whom had CKD. Replacing the sodium in bread with varying amounts of potassium chloride (20%, 30%, and 40%) would result in one-third of people with CKD exceeding the safe limits for dietary potassium consumption (31.8%, 32.6%, and 33%, respectively), they found.

“Potassium chloride substitution in staple foods such as bread and bread products have serious and potentially fatal consequences for people who need to restrict dietary potassium. Improved food labelling is required for consumers to avoid excessive consumption,” Ms. Morrison and colleagues concluded. They added that more studies are needed to further understand the risks of potassium dietary intake and hyperkalemia in CKD from potassium-based salt substitutes.

The American Heart Association recommends no more than 1,500 mg of sodium intake daily for persons with CKD, diabetes, or high blood pressure; those older than 51; and African American persons of any age.

The recommended daily intake of potassium in persons with CKD can range from 2,000 mg to 4,000 mg, depending on the individual and their degree of CKD. The potassium content in some salt substitutes varies from 440 mg to 2,800 mg per teaspoon.

The best recommendation for individuals with CKD and a goal to reduce their sodium intake is to use herbs and lower-sodium seasonings as a substitute, but these should always be reviewed with their physician and renal nutritionist.

Dr. Brookins is a board-certified nephrologist and internist practicing in Georgia. She is the founder and owner of Remote Renal Care, a telehealth kidney practice. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When we refer to “regular table salt,” it is most commonly in the form of sodium chloride, which is also a major constituent of packaged and ultraprocessed foods.

The best approach to finding the “healthiest salt” – which really means the lowest in sodium – is to look for the amount on the label. “Sodium-free” usually indicates less than 5 mg of sodium per serving, and “low-sodium” usually means 140 mg or less per serving. In contrast, regular table salt can contain as much as 560 mg of sodium in one serving.

Other en vogue salts, such as pink Himalayan salt, sea salt, and kosher salt, are high in sodium content – like regular table salt – but because of their larger crystal size, less sodium is delivered per serving.

Most salt substitutes are reduced in sodium, with the addition of potassium chloride instead.

FDA issues guidance on reducing salt

Currently, the U.S. sodium dietary guidelines for persons older than 14 stipulate 2,300 mg/d, which is equivalent to 1 teaspoon a day. However it is estimated that the average person in the United States consumes more than this – around 3,400 mg of sodium daily.

In October 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published guidance on voluntary sodium limitations in commercially processed, packaged, and prepared food. The FDA’s short-term approach is to slowly reduce exposure to sodium in processed and restaurant food by 2025, on the basis that people will eventually get used to less salt, as has happened in the United Kingdom and other countries.

Such strategies to reduce salt intake are now being used in national programs in several countries. Many of these successful initiatives include active engagement with the food industry to reduce the amount of sodium added to processed food, as well as public awareness campaigns to alert consumers to the dangers of eating too much salt. This includes increasing potassium in manufactured foods, primarily to target hypertension and heart disease, as described by Clare Farrand, MSc, BSc, and colleagues, in the Journal of Clinical Hypertension. The authors also make several recommendations regarding salt reduction policies:

- Food manufacturers should gradually reduce sodium in food to the lowest possible levels and explore the use of potassium-based sodium replacers to reduce sodium levels even further.

- Governments should continue to monitor sodium and potassium levels in processed foods.

- Further consideration may need to be given to how best to label salt substitutes (namely potassium) in processed foods to ensure that people who may be adversely affected are aware.

- Governments should systematically monitor potassium intake at the population level, including for specific susceptible groups.

- Governments should continue to systematically monitor sodium (salt) intake and iodine intake at the population level to adjust salt iodization over time as necessary, depending on observed salt intake in specific targeted groups, to ensure that they have sufficient but not excessive iodine intakes as salt intakes are reduced.

- Governments should consider opportunities for promoting and subsidizing salt substitutes, particularly in countries where salt added during cooking or at the table is the major source of salt in the diet.

The new FDA document includes 163 subcategories of foods in its voluntary salt reduction strategy.

Salt substitutes, high blood pressure, and mortality

Lowering sodium intake is almost certainly beneficial for persons with high blood pressure. In 2020, a review in Hypertension highlighted the benefit of salt substitutes in reducing hypertension, reporting that they lower systolic blood pressure by 5.58 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.88 mm Hg.

And changes to dietary sodium intake can potentially reduce or obviate the need for medications for essential hypertension in some individuals. Although there are only a few studies on this topic, a study by Bruce Neal, MB, ChB, PhD, and colleagues, revealed a reduction in stroke, cardiovascular events, and deaths with the use of potassium-based salt substitutes.

Salt substitutes and sodium and potassium handling in the kidneys

Many studies have shown that potassium-rich salt substitutes are safe in individuals with normal kidney function, but are they safe and beneficial for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD)?

For anyone who is on a renal diet, potassium and sodium intake goals are limited according to their absolute level of kidney function.

There have been case reports of life-threatening blood potassium levels (hyperkalemia) due to potassium-rich salt substitutes in people with CKD, but no larger published studies on this topic can be found.

A diet modeling study by Rebecca Morrison and colleagues evaluated varying degrees of potassium-enriched salt substituted bread products and their impact on dietary intake in persons with CKD. They used dietary data from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011-2012 in Australia for 12,152 participants, 154 of whom had CKD. Replacing the sodium in bread with varying amounts of potassium chloride (20%, 30%, and 40%) would result in one-third of people with CKD exceeding the safe limits for dietary potassium consumption (31.8%, 32.6%, and 33%, respectively), they found.

“Potassium chloride substitution in staple foods such as bread and bread products have serious and potentially fatal consequences for people who need to restrict dietary potassium. Improved food labelling is required for consumers to avoid excessive consumption,” Ms. Morrison and colleagues concluded. They added that more studies are needed to further understand the risks of potassium dietary intake and hyperkalemia in CKD from potassium-based salt substitutes.

The American Heart Association recommends no more than 1,500 mg of sodium intake daily for persons with CKD, diabetes, or high blood pressure; those older than 51; and African American persons of any age.

The recommended daily intake of potassium in persons with CKD can range from 2,000 mg to 4,000 mg, depending on the individual and their degree of CKD. The potassium content in some salt substitutes varies from 440 mg to 2,800 mg per teaspoon.

The best recommendation for individuals with CKD and a goal to reduce their sodium intake is to use herbs and lower-sodium seasonings as a substitute, but these should always be reviewed with their physician and renal nutritionist.

Dr. Brookins is a board-certified nephrologist and internist practicing in Georgia. She is the founder and owner of Remote Renal Care, a telehealth kidney practice. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When we refer to “regular table salt,” it is most commonly in the form of sodium chloride, which is also a major constituent of packaged and ultraprocessed foods.

The best approach to finding the “healthiest salt” – which really means the lowest in sodium – is to look for the amount on the label. “Sodium-free” usually indicates less than 5 mg of sodium per serving, and “low-sodium” usually means 140 mg or less per serving. In contrast, regular table salt can contain as much as 560 mg of sodium in one serving.

Other en vogue salts, such as pink Himalayan salt, sea salt, and kosher salt, are high in sodium content – like regular table salt – but because of their larger crystal size, less sodium is delivered per serving.

Most salt substitutes are reduced in sodium, with the addition of potassium chloride instead.

FDA issues guidance on reducing salt

Currently, the U.S. sodium dietary guidelines for persons older than 14 stipulate 2,300 mg/d, which is equivalent to 1 teaspoon a day. However it is estimated that the average person in the United States consumes more than this – around 3,400 mg of sodium daily.

In October 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published guidance on voluntary sodium limitations in commercially processed, packaged, and prepared food. The FDA’s short-term approach is to slowly reduce exposure to sodium in processed and restaurant food by 2025, on the basis that people will eventually get used to less salt, as has happened in the United Kingdom and other countries.

Such strategies to reduce salt intake are now being used in national programs in several countries. Many of these successful initiatives include active engagement with the food industry to reduce the amount of sodium added to processed food, as well as public awareness campaigns to alert consumers to the dangers of eating too much salt. This includes increasing potassium in manufactured foods, primarily to target hypertension and heart disease, as described by Clare Farrand, MSc, BSc, and colleagues, in the Journal of Clinical Hypertension. The authors also make several recommendations regarding salt reduction policies:

- Food manufacturers should gradually reduce sodium in food to the lowest possible levels and explore the use of potassium-based sodium replacers to reduce sodium levels even further.

- Governments should continue to monitor sodium and potassium levels in processed foods.

- Further consideration may need to be given to how best to label salt substitutes (namely potassium) in processed foods to ensure that people who may be adversely affected are aware.

- Governments should systematically monitor potassium intake at the population level, including for specific susceptible groups.

- Governments should continue to systematically monitor sodium (salt) intake and iodine intake at the population level to adjust salt iodization over time as necessary, depending on observed salt intake in specific targeted groups, to ensure that they have sufficient but not excessive iodine intakes as salt intakes are reduced.

- Governments should consider opportunities for promoting and subsidizing salt substitutes, particularly in countries where salt added during cooking or at the table is the major source of salt in the diet.

The new FDA document includes 163 subcategories of foods in its voluntary salt reduction strategy.

Salt substitutes, high blood pressure, and mortality

Lowering sodium intake is almost certainly beneficial for persons with high blood pressure. In 2020, a review in Hypertension highlighted the benefit of salt substitutes in reducing hypertension, reporting that they lower systolic blood pressure by 5.58 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 2.88 mm Hg.

And changes to dietary sodium intake can potentially reduce or obviate the need for medications for essential hypertension in some individuals. Although there are only a few studies on this topic, a study by Bruce Neal, MB, ChB, PhD, and colleagues, revealed a reduction in stroke, cardiovascular events, and deaths with the use of potassium-based salt substitutes.

Salt substitutes and sodium and potassium handling in the kidneys

Many studies have shown that potassium-rich salt substitutes are safe in individuals with normal kidney function, but are they safe and beneficial for people with chronic kidney disease (CKD)?

For anyone who is on a renal diet, potassium and sodium intake goals are limited according to their absolute level of kidney function.

There have been case reports of life-threatening blood potassium levels (hyperkalemia) due to potassium-rich salt substitutes in people with CKD, but no larger published studies on this topic can be found.

A diet modeling study by Rebecca Morrison and colleagues evaluated varying degrees of potassium-enriched salt substituted bread products and their impact on dietary intake in persons with CKD. They used dietary data from the National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2011-2012 in Australia for 12,152 participants, 154 of whom had CKD. Replacing the sodium in bread with varying amounts of potassium chloride (20%, 30%, and 40%) would result in one-third of people with CKD exceeding the safe limits for dietary potassium consumption (31.8%, 32.6%, and 33%, respectively), they found.

“Potassium chloride substitution in staple foods such as bread and bread products have serious and potentially fatal consequences for people who need to restrict dietary potassium. Improved food labelling is required for consumers to avoid excessive consumption,” Ms. Morrison and colleagues concluded. They added that more studies are needed to further understand the risks of potassium dietary intake and hyperkalemia in CKD from potassium-based salt substitutes.

The American Heart Association recommends no more than 1,500 mg of sodium intake daily for persons with CKD, diabetes, or high blood pressure; those older than 51; and African American persons of any age.

The recommended daily intake of potassium in persons with CKD can range from 2,000 mg to 4,000 mg, depending on the individual and their degree of CKD. The potassium content in some salt substitutes varies from 440 mg to 2,800 mg per teaspoon.

The best recommendation for individuals with CKD and a goal to reduce their sodium intake is to use herbs and lower-sodium seasonings as a substitute, but these should always be reviewed with their physician and renal nutritionist.

Dr. Brookins is a board-certified nephrologist and internist practicing in Georgia. She is the founder and owner of Remote Renal Care, a telehealth kidney practice. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mycoplasma genitalium: The Smallest Pathogen Becoming a Big Concern

This supplement reviews key aspects of Mycoplasma genitalium and further testing and treatment options for the STI. To read more about this click the link below.

Click Here to Read More

This supplement reviews key aspects of Mycoplasma genitalium and further testing and treatment options for the STI. To read more about this click the link below.

Click Here to Read More

This supplement reviews key aspects of Mycoplasma genitalium and further testing and treatment options for the STI. To read more about this click the link below.

Click Here to Read More

New data explore risk of magnetic interference with implantable devices

Building on several previous reports that the newest models of mobile telephones and other electronics that use magnets pose a threat to the function of defibrillators and other implantable cardiovascular devices, a new study implicates any device that emits a 10-gauss (G) magnetic field more than a couple of inches.

“Beside the devices described in our manuscript, this can be any portable consumer product [with magnets] like electric cigarettes or smart watches,” explained study author Sven Knecht, DSc, a research electrophysiologist associated with the department of cardiology, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland).

In the newly published article, the investigators evaluated earphones, earphone charging cases, and two electronic pens used to draw on electronic tablets. These particular devices are of interest because, like mobile phones, they are of a size and shape to fit in a breast pocket adjacent to where many cardiovascular devices are implanted.

The study joins several previous studies that have shown the same risk, but this study used three-dimensional (3D) mapping of the magnetic field rather than a one-axis sensor, which is a standard adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to the investigators.

3D mapping assessment used

Because of the 3D nature of magnetic fields, 3D mapping serves as a better tool to assess the risk of the magnetic force as the intensity gradient diminishes with distance from the source, the authors contended. The 3D maps used in this study have a resolution to 2 mm.

The ex vivo measurements of the magnetic field, which could be displayed in a configurable 3D volume in relation to the electronic products were performed on five different explanted cardioverter defibrillators from two manufacturers.

In the ex vivo setting, the ability of the earphones, earphone charging cases, and electronic pens to interfere with defibrillator function was compared to that of the Apple iPhone 12 Max, which was the subject of a small in vivo study published in 2021. When the iPhone 12 Max was placed on the skin over a cardiac implantable device in that study, clinically identifiable interference could be detected in all 3 patients evaluated.

Based on previous work, the International Organization for Standardization has established that a minimal field strength of 10 G is needed to interfere with an implantable device, but the actual risk from any specific device is determined by the distance at which this strength of magnetic field is projected.

In the 3D analysis, the 10-G intensity was found to project 20 mm from the surface of the ear phones, ear phone charging case, and one of the electronic pens and to project 29 mm from the other electronic pen. When tested against the five defibrillators, magnetic reversion mode was triggered by the portable electronics at distances ranging from 8 to 18 mm.

In an interview, Dr. Knecht explained that this study adds more devices to the list of those associated with potential for interfering with implantable cardiovascular devices, but added that the more important point is that any device that contains magnets emitting a force of 10 G or greater for more than a few inches can be expected to be associated with clinically meaningful interference. The devices tested in this study were produced by Apple and Microsoft, but a focus on specific devices obscures the main message.

“All portable electronics with an embedded permanent magnet creating a 10-G magnetic field have a theoretical capability of triggering implantable devices,” he said.

For pacemakers, the interference is likely to trigger constant pacing, which would not be expected to pose a significant health threat if detected with a reasonable period, according to Dr. Knecht. Interference is potentially more serious for defibrillators, which might fail during magnetic interference to provide the shock needed to terminate a serious arrhythmia.

The combination of events – interference at the time of an arrhythmia – make this risk “very low,” but Dr. Knecht said it is sufficient to mean that patients receiving an implantable cardiovascular device should be made aware of the risk and the need to avoid placing portable electronic products near the implanted device.

When in vivo evidence of a disturbance with the iPhone 12 was reported in 2021, it amplified existing concern. The American Heart Association maintains a list of electronic products with the potential to interfere with implantable devices on its website. But, again, understanding the potential for risk and the need to keep electronic products with magnets at a safe distance from cardiovascular implantable devices is more important than trying to memorize the ever-growing list of devices with this capability.

“Prudent education of patients receiving an implantable device is important,” said N.A. Mark Estes III, MD, professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh. However, in an interview, he warned that the growing list of implicated devices makes a complete survey impractical, and, even if achievable, likely to leave patients “feeling overwhelmed.”

In Dr. Estes’s practice, he does provide printed information about the risks of electronics to interfere with implantable devices as well as a list of dos and don’ts. He agreed that the absolute risk of interference from a device causing significant clinical complications is low, but the goal is to “bring it as close to zero as possible.”

“No clinical case of a meaningful interaction of an electronic product and dysfunction of an implantable device has ever been documented,” he said. Given the widespread use of the new generation of cellphones that contain magnets powerful enough to induce dysfunction in an implantable device, “this speaks to the fact that the risk continues to be very low.”

Dr. Knecht and coinvestigators, along with Dr. Estes, reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Building on several previous reports that the newest models of mobile telephones and other electronics that use magnets pose a threat to the function of defibrillators and other implantable cardiovascular devices, a new study implicates any device that emits a 10-gauss (G) magnetic field more than a couple of inches.

“Beside the devices described in our manuscript, this can be any portable consumer product [with magnets] like electric cigarettes or smart watches,” explained study author Sven Knecht, DSc, a research electrophysiologist associated with the department of cardiology, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland).

In the newly published article, the investigators evaluated earphones, earphone charging cases, and two electronic pens used to draw on electronic tablets. These particular devices are of interest because, like mobile phones, they are of a size and shape to fit in a breast pocket adjacent to where many cardiovascular devices are implanted.

The study joins several previous studies that have shown the same risk, but this study used three-dimensional (3D) mapping of the magnetic field rather than a one-axis sensor, which is a standard adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, according to the investigators.

3D mapping assessment used

Because of the 3D nature of magnetic fields, 3D mapping serves as a better tool to assess the risk of the magnetic force as the intensity gradient diminishes with distance from the source, the authors contended. The 3D maps used in this study have a resolution to 2 mm.

The ex vivo measurements of the magnetic field, which could be displayed in a configurable 3D volume in relation to the electronic products were performed on five different explanted cardioverter defibrillators from two manufacturers.

In the ex vivo setting, the ability of the earphones, earphone charging cases, and electronic pens to interfere with defibrillator function was compared to that of the Apple iPhone 12 Max, which was the subject of a small in vivo study published in 2021. When the iPhone 12 Max was placed on the skin over a cardiac implantable device in that study, clinically identifiable interference could be detected in all 3 patients evaluated.

Based on previous work, the International Organization for Standardization has established that a minimal field strength of 10 G is needed to interfere with an implantable device, but the actual risk from any specific device is determined by the distance at which this strength of magnetic field is projected.

In the 3D analysis, the 10-G intensity was found to project 20 mm from the surface of the ear phones, ear phone charging case, and one of the electronic pens and to project 29 mm from the other electronic pen. When tested against the five defibrillators, magnetic reversion mode was triggered by the portable electronics at distances ranging from 8 to 18 mm.

In an interview, Dr. Knecht explained that this study adds more devices to the list of those associated with potential for interfering with implantable cardiovascular devices, but added that the more important point is that any device that contains magnets emitting a force of 10 G or greater for more than a few inches can be expected to be associated with clinically meaningful interference. The devices tested in this study were produced by Apple and Microsoft, but a focus on specific devices obscures the main message.

“All portable electronics with an embedded permanent magnet creating a 10-G magnetic field have a theoretical capability of triggering implantable devices,” he said.

For pacemakers, the interference is likely to trigger constant pacing, which would not be expected to pose a significant health threat if detected with a reasonable period, according to Dr. Knecht. Interference is potentially more serious for defibrillators, which might fail during magnetic interference to provide the shock needed to terminate a serious arrhythmia.

The combination of events – interference at the time of an arrhythmia – make this risk “very low,” but Dr. Knecht said it is sufficient to mean that patients receiving an implantable cardiovascular device should be made aware of the risk and the need to avoid placing portable electronic products near the implanted device.

When in vivo evidence of a disturbance with the iPhone 12 was reported in 2021, it amplified existing concern. The American Heart Association maintains a list of electronic products with the potential to interfere with implantable devices on its website. But, again, understanding the potential for risk and the need to keep electronic products with magnets at a safe distance from cardiovascular implantable devices is more important than trying to memorize the ever-growing list of devices with this capability.

“Prudent education of patients receiving an implantable device is important,” said N.A. Mark Estes III, MD, professor of medicine in the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh. However, in an interview, he warned that the growing list of implicated devices makes a complete survey impractical, and, even if achievable, likely to leave patients “feeling overwhelmed.”

In Dr. Estes’s practice, he does provide printed information about the risks of electronics to interfere with implantable devices as well as a list of dos and don’ts. He agreed that the absolute risk of interference from a device causing significant clinical complications is low, but the goal is to “bring it as close to zero as possible.”

“No clinical case of a meaningful interaction of an electronic product and dysfunction of an implantable device has ever been documented,” he said. Given the widespread use of the new generation of cellphones that contain magnets powerful enough to induce dysfunction in an implantable device, “this speaks to the fact that the risk continues to be very low.”

Dr. Knecht and coinvestigators, along with Dr. Estes, reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Building on several previous reports that the newest models of mobile telephones and other electronics that use magnets pose a threat to the function of defibrillators and other implantable cardiovascular devices, a new study implicates any device that emits a 10-gauss (G) magnetic field more than a couple of inches.

“Beside the devices described in our manuscript, this can be any portable consumer product [with magnets] like electric cigarettes or smart watches,” explained study author Sven Knecht, DSc, a research electrophysiologist associated with the department of cardiology, University Hospital Basel (Switzerland).