User login

Endometriosis and infertility – Combining a chronic physical and emotional pain

Pain is classified as chronic when it lasts or recurs for more than 3-6 months (“Classification of chronic pain” 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994). This universally accepted definition does not distinguish between physical and emotional pain. Categorically, pain is pain. Two prevalent chronic gynecologic diseases are closely related medically and emotionally. Forty percent to 50% of women with endometriosis have infertility; 30%-50% of women with infertility are found to have coexisting endometriosis. The approach to both is, typically, symptomatic treatment. In this month’s column, I examine the relationship between these ailments and how we can advise women on management.

Endometriosis is simply defined as the displacement of normal endometrial glands and stroma from their natural anatomical location to elsewhere in the body. With the recent identification of the disease in the spleen, endometriosis has been found in every organ system. Endometriosis is identified in 6%-10% of the general female population. The prevalence ranges from 2% to 11% among asymptomatic women and from 5% to 21% in women hospitalized for pelvic pain (Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:1-15). Compared with fertile women, infertile women are six to eight times more likely to have endometriosis (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Retrograde menstruation is the presumed theory for the origins of endometriosis, that is, the reflux of menstrual debris containing active endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-69). Because of the varied etiologies of the most common symptoms of endometriosis, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, and infertility, women visit, on average, seven physicians before being diagnosed (Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366). The delay in promptly identifying endometriosis is further impaired by the lack of specific biomarkers, awareness, and inadequate evaluation (N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56).

The 2008 U.S. health care costs for endometriosis were approximately $4,000 per affected woman, analogous to the costs for other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis (Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1292-9). The management of symptoms further increases the financial burden because of the effect of the disease on physical, mental, sexual, and social well-being, as well as productivity (Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:123).

We have known the paradoxical relationship between the stage of endometriosis and symptoms: Women with low-stage disease may present with severe pain and/or infertility but those with advanced-stage disease may be asymptomatic. Endometriotic cells and tissue elicit a localized immune and inflammatory response with the production of cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins. Given the usual intra-abdominal location and the small size of implants, endometriosis requires a surgical diagnosis, ideally with histopathology for confirmation. However, imaging – transvaginal ultrasound or MRI – has more than 90% sensitivity and specificity for identifying endometriomas (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2[2]:CD009591).

The effect of endometriosis on fertility, particularly in women with minimal to mild stages, is not clear, and many studies have been retrospective. Tubal factor infertility can be a result of endometriosis. Per the 2020 Cochrane Database Systemic Reviews (2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031), “Compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis; no data were reported on live birth. There is moderate-quality evidence that laparoscopic surgery increases viable intrauterine pregnancy rates confirmed by ultrasound compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only.” In women undergoing IVF, more advanced stages of endometriosis have reduced pregnancy outcomes as shown in recent meta-analyses (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:79-88).

The revised ASRM (rASRM) surgical staging classification of endometriosis has been widely used to describe the degree, although it poorly correlates with fertility potential (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8). Women diagnosed with endometriosis may benefit from the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), published in 2010 as a useful scoring system to predict postoperative non-IVF pregnancy rates (both by natural means and intrauterine insemination) based on patient characteristics, rASRM staging and “least function” score of the adnexa (Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1609-15).

Compared with diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis. “Further research is needed considering the management of different subtypes of endometriosis and comparing laparoscopic interventions with lifestyle and medical interventions (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031).”

The treatment of endometriosis is directly related to the desire for and timing of fertility since therapy is often contraceptive, as opposed to surgery. Because endometriosis is exacerbated by estradiol, the mainstay of medical therapy is initially combined hormonal or progestin-only contraception as a means of reducing pelvic pain by reducing estradiol production and action, respectively. GnRH-agonist suppression of follicle stimulation hormone and luteinizing hormone remains the standard for inactivating endogenous estradiol. In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved elagolix for the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis – the first pill specifically approved for endometriosis pain relief. An off-label approach for women is letrozole, the aromatase inhibitor, to reduce circulating estradiol levels. Unfortunately, estradiol suppression cannot be used solely long term without add-back therapy, because of the risk of bone loss and vasomotor symptoms.

Excision of endometriomas adversely affects ovarian follicular reserve (as indicated by lower levels of anti-müllerian hormone and reduced ovarian antral follicle counts on ultrasound). For women who want to preserve their fertility, the potential benefits of surgery should be weighed against these negative effects. Surgical treatment of endometriosis in women without other identifiable infertility factors may improve rates of spontaneous pregnancy. In women with moderate to severe endometriosis, intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation may be of value, particularly with preceding GnRH-agonist therapy (J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018;10[3]:158-73).

Despite the reduction in IVF outcomes in women with moderate to severe endometriosis, it remains unclear whether surgery improves the likelihood of pregnancy with IVF as does the concurrent use of prolonged GnRH agonist during IVF stimulation. (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Summary

- Medical therapy alone does not appear to improve fertility in endometriosis.

- Surgical treatment of endometriosis improves natural fertility, particularly in lower-stage endometriosis.

- EFI is a useful tool to predict postoperative natural fertility and assess the need for IVF.

- Despite advanced endometriosis reducing IVF outcomes, surgery or medical pretreatment to increase IVF success remains unproven.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Pain is classified as chronic when it lasts or recurs for more than 3-6 months (“Classification of chronic pain” 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994). This universally accepted definition does not distinguish between physical and emotional pain. Categorically, pain is pain. Two prevalent chronic gynecologic diseases are closely related medically and emotionally. Forty percent to 50% of women with endometriosis have infertility; 30%-50% of women with infertility are found to have coexisting endometriosis. The approach to both is, typically, symptomatic treatment. In this month’s column, I examine the relationship between these ailments and how we can advise women on management.

Endometriosis is simply defined as the displacement of normal endometrial glands and stroma from their natural anatomical location to elsewhere in the body. With the recent identification of the disease in the spleen, endometriosis has been found in every organ system. Endometriosis is identified in 6%-10% of the general female population. The prevalence ranges from 2% to 11% among asymptomatic women and from 5% to 21% in women hospitalized for pelvic pain (Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:1-15). Compared with fertile women, infertile women are six to eight times more likely to have endometriosis (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Retrograde menstruation is the presumed theory for the origins of endometriosis, that is, the reflux of menstrual debris containing active endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-69). Because of the varied etiologies of the most common symptoms of endometriosis, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, and infertility, women visit, on average, seven physicians before being diagnosed (Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366). The delay in promptly identifying endometriosis is further impaired by the lack of specific biomarkers, awareness, and inadequate evaluation (N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56).

The 2008 U.S. health care costs for endometriosis were approximately $4,000 per affected woman, analogous to the costs for other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis (Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1292-9). The management of symptoms further increases the financial burden because of the effect of the disease on physical, mental, sexual, and social well-being, as well as productivity (Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:123).

We have known the paradoxical relationship between the stage of endometriosis and symptoms: Women with low-stage disease may present with severe pain and/or infertility but those with advanced-stage disease may be asymptomatic. Endometriotic cells and tissue elicit a localized immune and inflammatory response with the production of cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins. Given the usual intra-abdominal location and the small size of implants, endometriosis requires a surgical diagnosis, ideally with histopathology for confirmation. However, imaging – transvaginal ultrasound or MRI – has more than 90% sensitivity and specificity for identifying endometriomas (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2[2]:CD009591).

The effect of endometriosis on fertility, particularly in women with minimal to mild stages, is not clear, and many studies have been retrospective. Tubal factor infertility can be a result of endometriosis. Per the 2020 Cochrane Database Systemic Reviews (2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031), “Compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis; no data were reported on live birth. There is moderate-quality evidence that laparoscopic surgery increases viable intrauterine pregnancy rates confirmed by ultrasound compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only.” In women undergoing IVF, more advanced stages of endometriosis have reduced pregnancy outcomes as shown in recent meta-analyses (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:79-88).

The revised ASRM (rASRM) surgical staging classification of endometriosis has been widely used to describe the degree, although it poorly correlates with fertility potential (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8). Women diagnosed with endometriosis may benefit from the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), published in 2010 as a useful scoring system to predict postoperative non-IVF pregnancy rates (both by natural means and intrauterine insemination) based on patient characteristics, rASRM staging and “least function” score of the adnexa (Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1609-15).

Compared with diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis. “Further research is needed considering the management of different subtypes of endometriosis and comparing laparoscopic interventions with lifestyle and medical interventions (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031).”

The treatment of endometriosis is directly related to the desire for and timing of fertility since therapy is often contraceptive, as opposed to surgery. Because endometriosis is exacerbated by estradiol, the mainstay of medical therapy is initially combined hormonal or progestin-only contraception as a means of reducing pelvic pain by reducing estradiol production and action, respectively. GnRH-agonist suppression of follicle stimulation hormone and luteinizing hormone remains the standard for inactivating endogenous estradiol. In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved elagolix for the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis – the first pill specifically approved for endometriosis pain relief. An off-label approach for women is letrozole, the aromatase inhibitor, to reduce circulating estradiol levels. Unfortunately, estradiol suppression cannot be used solely long term without add-back therapy, because of the risk of bone loss and vasomotor symptoms.

Excision of endometriomas adversely affects ovarian follicular reserve (as indicated by lower levels of anti-müllerian hormone and reduced ovarian antral follicle counts on ultrasound). For women who want to preserve their fertility, the potential benefits of surgery should be weighed against these negative effects. Surgical treatment of endometriosis in women without other identifiable infertility factors may improve rates of spontaneous pregnancy. In women with moderate to severe endometriosis, intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation may be of value, particularly with preceding GnRH-agonist therapy (J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018;10[3]:158-73).

Despite the reduction in IVF outcomes in women with moderate to severe endometriosis, it remains unclear whether surgery improves the likelihood of pregnancy with IVF as does the concurrent use of prolonged GnRH agonist during IVF stimulation. (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Summary

- Medical therapy alone does not appear to improve fertility in endometriosis.

- Surgical treatment of endometriosis improves natural fertility, particularly in lower-stage endometriosis.

- EFI is a useful tool to predict postoperative natural fertility and assess the need for IVF.

- Despite advanced endometriosis reducing IVF outcomes, surgery or medical pretreatment to increase IVF success remains unproven.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Pain is classified as chronic when it lasts or recurs for more than 3-6 months (“Classification of chronic pain” 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994). This universally accepted definition does not distinguish between physical and emotional pain. Categorically, pain is pain. Two prevalent chronic gynecologic diseases are closely related medically and emotionally. Forty percent to 50% of women with endometriosis have infertility; 30%-50% of women with infertility are found to have coexisting endometriosis. The approach to both is, typically, symptomatic treatment. In this month’s column, I examine the relationship between these ailments and how we can advise women on management.

Endometriosis is simply defined as the displacement of normal endometrial glands and stroma from their natural anatomical location to elsewhere in the body. With the recent identification of the disease in the spleen, endometriosis has been found in every organ system. Endometriosis is identified in 6%-10% of the general female population. The prevalence ranges from 2% to 11% among asymptomatic women and from 5% to 21% in women hospitalized for pelvic pain (Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:1-15). Compared with fertile women, infertile women are six to eight times more likely to have endometriosis (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Retrograde menstruation is the presumed theory for the origins of endometriosis, that is, the reflux of menstrual debris containing active endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422-69). Because of the varied etiologies of the most common symptoms of endometriosis, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, and infertility, women visit, on average, seven physicians before being diagnosed (Fertil Steril. 2011;96:366). The delay in promptly identifying endometriosis is further impaired by the lack of specific biomarkers, awareness, and inadequate evaluation (N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1244-56).

The 2008 U.S. health care costs for endometriosis were approximately $4,000 per affected woman, analogous to the costs for other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis (Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1292-9). The management of symptoms further increases the financial burden because of the effect of the disease on physical, mental, sexual, and social well-being, as well as productivity (Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:123).

We have known the paradoxical relationship between the stage of endometriosis and symptoms: Women with low-stage disease may present with severe pain and/or infertility but those with advanced-stage disease may be asymptomatic. Endometriotic cells and tissue elicit a localized immune and inflammatory response with the production of cytokines, chemokines, and prostaglandins. Given the usual intra-abdominal location and the small size of implants, endometriosis requires a surgical diagnosis, ideally with histopathology for confirmation. However, imaging – transvaginal ultrasound or MRI – has more than 90% sensitivity and specificity for identifying endometriomas (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2[2]:CD009591).

The effect of endometriosis on fertility, particularly in women with minimal to mild stages, is not clear, and many studies have been retrospective. Tubal factor infertility can be a result of endometriosis. Per the 2020 Cochrane Database Systemic Reviews (2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031), “Compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis; no data were reported on live birth. There is moderate-quality evidence that laparoscopic surgery increases viable intrauterine pregnancy rates confirmed by ultrasound compared to diagnostic laparoscopy only.” In women undergoing IVF, more advanced stages of endometriosis have reduced pregnancy outcomes as shown in recent meta-analyses (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:79-88).

The revised ASRM (rASRM) surgical staging classification of endometriosis has been widely used to describe the degree, although it poorly correlates with fertility potential (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8). Women diagnosed with endometriosis may benefit from the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI), published in 2010 as a useful scoring system to predict postoperative non-IVF pregnancy rates (both by natural means and intrauterine insemination) based on patient characteristics, rASRM staging and “least function” score of the adnexa (Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1609-15).

Compared with diagnostic laparoscopy only, it is uncertain whether laparoscopic surgery reduces overall pain associated with minimal to severe endometriosis. “Further research is needed considering the management of different subtypes of endometriosis and comparing laparoscopic interventions with lifestyle and medical interventions (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Oct;2020[10]:CD011031).”

The treatment of endometriosis is directly related to the desire for and timing of fertility since therapy is often contraceptive, as opposed to surgery. Because endometriosis is exacerbated by estradiol, the mainstay of medical therapy is initially combined hormonal or progestin-only contraception as a means of reducing pelvic pain by reducing estradiol production and action, respectively. GnRH-agonist suppression of follicle stimulation hormone and luteinizing hormone remains the standard for inactivating endogenous estradiol. In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved elagolix for the treatment of pain associated with endometriosis – the first pill specifically approved for endometriosis pain relief. An off-label approach for women is letrozole, the aromatase inhibitor, to reduce circulating estradiol levels. Unfortunately, estradiol suppression cannot be used solely long term without add-back therapy, because of the risk of bone loss and vasomotor symptoms.

Excision of endometriomas adversely affects ovarian follicular reserve (as indicated by lower levels of anti-müllerian hormone and reduced ovarian antral follicle counts on ultrasound). For women who want to preserve their fertility, the potential benefits of surgery should be weighed against these negative effects. Surgical treatment of endometriosis in women without other identifiable infertility factors may improve rates of spontaneous pregnancy. In women with moderate to severe endometriosis, intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation may be of value, particularly with preceding GnRH-agonist therapy (J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2018;10[3]:158-73).

Despite the reduction in IVF outcomes in women with moderate to severe endometriosis, it remains unclear whether surgery improves the likelihood of pregnancy with IVF as does the concurrent use of prolonged GnRH agonist during IVF stimulation. (Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591-8).

Summary

- Medical therapy alone does not appear to improve fertility in endometriosis.

- Surgical treatment of endometriosis improves natural fertility, particularly in lower-stage endometriosis.

- EFI is a useful tool to predict postoperative natural fertility and assess the need for IVF.

- Despite advanced endometriosis reducing IVF outcomes, surgery or medical pretreatment to increase IVF success remains unproven.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

NAMS affirms value of hormone therapy for menopausal women

Hormone therapy remains a topic for debate, but a constant in the 2 decades since the Women’s Health Initiative has been the demonstrated effectiveness for relief of vasomotor symptoms and reduction of fracture risk in menopausal women, according to the latest hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society.

“Healthcare professionals caring for menopausal women should understand the basic concepts of relative risk and absolute risk,” wrote Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health and medical director of NAMS, and members of the NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel in Menopause.

The authors noted that the risks of hormone therapy vary considerably based on type, dose, duration, route of administration, timing of the start of therapy, and whether or not a progestogen is included.

The 2022 statement was commissioned to review new literature and identify the strength of recommendations and quality of evidence since the previous statement in 2017.

The current statement represents not so much a practice-changing update, “but rather that the literature has filled out in some areas,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “The recommendations overall haven’t changed,” she said. “The position statement reiterates that hormone therapy, which is significantly underutilized, remains a safe and effective treatment for menopause symptoms, which remain undertreated, with the benefits outweighing the risks for most healthy women who are within 10 years of menopause onset and under the age of 60 years,” she emphasized. “Individualizing therapy is key to maximizing benefits and minimizing risks,” she added.

Overall, the authors confirmed that hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of hormone therapy differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen is used.

Risks and benefits should be stratified by age and time since the start of menopause, according to the statement.

For women younger than 60 years or within 10 years of the onset of menopause who have no contraindications, the potential benefits outweigh the risks in most cases for use of hormone therapy to manage vasomotor symptoms and to help prevent bone loss and reduce fracture risk.

For women who begin hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from the start of menopause, or who are aged 60 years and older, the risk-benefit ratio may be less favorable because of the increased absolute risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and dementia. However, strategies such as lower doses and transdermal administration may reduce this risk, according to the statement.

The authors continue to recommend that longer durations of hormone therapy be for documented indications, such as VMS relief, and that patients on longer duration of therapy be reassessed periodically as part of a shared decision-making process. Women with persistent VMS or quality of life issues, or those at risk for osteoporosis, may continue hormone therapy beyond age 60 or 65 years after appropriate evaluation and risk-benefit counseling.

Women with ongoing GSM without indications for systemic therapy whose GSM persists after over-the-counter therapies may try low-dose vaginal estrogen or other nonestrogen therapies regardless of age and for an extended duration if needed, according to the statement.

Challenges, research gaps, and goals

“Barriers to the use of hormone therapy include lack of access to high quality care,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. The NAMS website, menopause.org, features an option to search for a NAMS-certified provider by ZIP code, she noted.

“Coverage of hormone therapy is highly variable and depends on the insurance company, but most women have access to one form or another with insurance coverage,” she said. “We need to continue to advocate for adequate coverage of menopause symptom treatments, including hormone therapy, so that women’s symptoms – which can significantly affect quality of life – are adequately managed.

“Additional research is needed on the thrombotic risk (venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke) of oral versus transdermal therapies (including different formulations, doses, and durations of therapy),” Dr. Faubion told this news organization. “More clinical trial data are needed to confirm or refute the potential beneficial effects of hormone therapy on coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality when initiated in perimenopause or early postmenopause,” she said.

Other areas for research include “the breast effects of different estrogen preparations, including the role for selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) and tissue selective estrogen complex therapies, optimal progestogen or SERM regimens to prevent endometrial hyperplasia, the relationship between vasomotor symptoms and the risk for heart disease and cognitive changes, and the risks of premature ovarian insufficiency,” Dr. Faubion emphasized.

Looking ahead, “Studies are needed on the effects of longer use of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy after breast or endometrial cancer, extended use of hormone therapy in women who are early initiators, improved tools to personalize or individualize benefits and risks of hormone therapy, and the role of aging and genetics,” said Dr. Faubion. Other areas for further research include “the long-term benefits and risks on women’s health of lifestyle modification or complementary or nonhormone therapies, if chosen in addition to or over hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms, bone health, and cardiovascular disease risk reduction,” she added.

The complete statement was published in Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society.

The position statement received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Hormone therapy remains a topic for debate, but a constant in the 2 decades since the Women’s Health Initiative has been the demonstrated effectiveness for relief of vasomotor symptoms and reduction of fracture risk in menopausal women, according to the latest hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society.

“Healthcare professionals caring for menopausal women should understand the basic concepts of relative risk and absolute risk,” wrote Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health and medical director of NAMS, and members of the NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel in Menopause.

The authors noted that the risks of hormone therapy vary considerably based on type, dose, duration, route of administration, timing of the start of therapy, and whether or not a progestogen is included.

The 2022 statement was commissioned to review new literature and identify the strength of recommendations and quality of evidence since the previous statement in 2017.

The current statement represents not so much a practice-changing update, “but rather that the literature has filled out in some areas,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “The recommendations overall haven’t changed,” she said. “The position statement reiterates that hormone therapy, which is significantly underutilized, remains a safe and effective treatment for menopause symptoms, which remain undertreated, with the benefits outweighing the risks for most healthy women who are within 10 years of menopause onset and under the age of 60 years,” she emphasized. “Individualizing therapy is key to maximizing benefits and minimizing risks,” she added.

Overall, the authors confirmed that hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of hormone therapy differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen is used.

Risks and benefits should be stratified by age and time since the start of menopause, according to the statement.

For women younger than 60 years or within 10 years of the onset of menopause who have no contraindications, the potential benefits outweigh the risks in most cases for use of hormone therapy to manage vasomotor symptoms and to help prevent bone loss and reduce fracture risk.

For women who begin hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from the start of menopause, or who are aged 60 years and older, the risk-benefit ratio may be less favorable because of the increased absolute risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and dementia. However, strategies such as lower doses and transdermal administration may reduce this risk, according to the statement.

The authors continue to recommend that longer durations of hormone therapy be for documented indications, such as VMS relief, and that patients on longer duration of therapy be reassessed periodically as part of a shared decision-making process. Women with persistent VMS or quality of life issues, or those at risk for osteoporosis, may continue hormone therapy beyond age 60 or 65 years after appropriate evaluation and risk-benefit counseling.

Women with ongoing GSM without indications for systemic therapy whose GSM persists after over-the-counter therapies may try low-dose vaginal estrogen or other nonestrogen therapies regardless of age and for an extended duration if needed, according to the statement.

Challenges, research gaps, and goals

“Barriers to the use of hormone therapy include lack of access to high quality care,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. The NAMS website, menopause.org, features an option to search for a NAMS-certified provider by ZIP code, she noted.

“Coverage of hormone therapy is highly variable and depends on the insurance company, but most women have access to one form or another with insurance coverage,” she said. “We need to continue to advocate for adequate coverage of menopause symptom treatments, including hormone therapy, so that women’s symptoms – which can significantly affect quality of life – are adequately managed.

“Additional research is needed on the thrombotic risk (venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke) of oral versus transdermal therapies (including different formulations, doses, and durations of therapy),” Dr. Faubion told this news organization. “More clinical trial data are needed to confirm or refute the potential beneficial effects of hormone therapy on coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality when initiated in perimenopause or early postmenopause,” she said.

Other areas for research include “the breast effects of different estrogen preparations, including the role for selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) and tissue selective estrogen complex therapies, optimal progestogen or SERM regimens to prevent endometrial hyperplasia, the relationship between vasomotor symptoms and the risk for heart disease and cognitive changes, and the risks of premature ovarian insufficiency,” Dr. Faubion emphasized.

Looking ahead, “Studies are needed on the effects of longer use of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy after breast or endometrial cancer, extended use of hormone therapy in women who are early initiators, improved tools to personalize or individualize benefits and risks of hormone therapy, and the role of aging and genetics,” said Dr. Faubion. Other areas for further research include “the long-term benefits and risks on women’s health of lifestyle modification or complementary or nonhormone therapies, if chosen in addition to or over hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms, bone health, and cardiovascular disease risk reduction,” she added.

The complete statement was published in Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society.

The position statement received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Hormone therapy remains a topic for debate, but a constant in the 2 decades since the Women’s Health Initiative has been the demonstrated effectiveness for relief of vasomotor symptoms and reduction of fracture risk in menopausal women, according to the latest hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society.

“Healthcare professionals caring for menopausal women should understand the basic concepts of relative risk and absolute risk,” wrote Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, director of the Mayo Clinic Center for Women’s Health and medical director of NAMS, and members of the NAMS 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel in Menopause.

The authors noted that the risks of hormone therapy vary considerably based on type, dose, duration, route of administration, timing of the start of therapy, and whether or not a progestogen is included.

The 2022 statement was commissioned to review new literature and identify the strength of recommendations and quality of evidence since the previous statement in 2017.

The current statement represents not so much a practice-changing update, “but rather that the literature has filled out in some areas,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “The recommendations overall haven’t changed,” she said. “The position statement reiterates that hormone therapy, which is significantly underutilized, remains a safe and effective treatment for menopause symptoms, which remain undertreated, with the benefits outweighing the risks for most healthy women who are within 10 years of menopause onset and under the age of 60 years,” she emphasized. “Individualizing therapy is key to maximizing benefits and minimizing risks,” she added.

Overall, the authors confirmed that hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of hormone therapy differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen is used.

Risks and benefits should be stratified by age and time since the start of menopause, according to the statement.

For women younger than 60 years or within 10 years of the onset of menopause who have no contraindications, the potential benefits outweigh the risks in most cases for use of hormone therapy to manage vasomotor symptoms and to help prevent bone loss and reduce fracture risk.

For women who begin hormone therapy more than 10 or 20 years from the start of menopause, or who are aged 60 years and older, the risk-benefit ratio may be less favorable because of the increased absolute risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and dementia. However, strategies such as lower doses and transdermal administration may reduce this risk, according to the statement.

The authors continue to recommend that longer durations of hormone therapy be for documented indications, such as VMS relief, and that patients on longer duration of therapy be reassessed periodically as part of a shared decision-making process. Women with persistent VMS or quality of life issues, or those at risk for osteoporosis, may continue hormone therapy beyond age 60 or 65 years after appropriate evaluation and risk-benefit counseling.

Women with ongoing GSM without indications for systemic therapy whose GSM persists after over-the-counter therapies may try low-dose vaginal estrogen or other nonestrogen therapies regardless of age and for an extended duration if needed, according to the statement.

Challenges, research gaps, and goals

“Barriers to the use of hormone therapy include lack of access to high quality care,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. The NAMS website, menopause.org, features an option to search for a NAMS-certified provider by ZIP code, she noted.

“Coverage of hormone therapy is highly variable and depends on the insurance company, but most women have access to one form or another with insurance coverage,” she said. “We need to continue to advocate for adequate coverage of menopause symptom treatments, including hormone therapy, so that women’s symptoms – which can significantly affect quality of life – are adequately managed.

“Additional research is needed on the thrombotic risk (venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and stroke) of oral versus transdermal therapies (including different formulations, doses, and durations of therapy),” Dr. Faubion told this news organization. “More clinical trial data are needed to confirm or refute the potential beneficial effects of hormone therapy on coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality when initiated in perimenopause or early postmenopause,” she said.

Other areas for research include “the breast effects of different estrogen preparations, including the role for selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) and tissue selective estrogen complex therapies, optimal progestogen or SERM regimens to prevent endometrial hyperplasia, the relationship between vasomotor symptoms and the risk for heart disease and cognitive changes, and the risks of premature ovarian insufficiency,” Dr. Faubion emphasized.

Looking ahead, “Studies are needed on the effects of longer use of low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy after breast or endometrial cancer, extended use of hormone therapy in women who are early initiators, improved tools to personalize or individualize benefits and risks of hormone therapy, and the role of aging and genetics,” said Dr. Faubion. Other areas for further research include “the long-term benefits and risks on women’s health of lifestyle modification or complementary or nonhormone therapies, if chosen in addition to or over hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms, bone health, and cardiovascular disease risk reduction,” she added.

The complete statement was published in Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society.

The position statement received no outside funding. The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Concerns that low LDL-C alters cognitive function challenged in novel analysis

PCSK9 inhibitors, which are among the most effective therapies for reducing LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), are associated with a neutral effect on cognitive function, according to a genetics-based Mendelian randomization study intended to sort out through the complexity of confounders.

The same study linked HMG-Co A reductase inhibitors (statins) with the potential for modest adverse neurocognitive effects, although these are likely to be outweighed by cardiovascular benefits, according to a collaborating team of investigators from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the University of Oxford (England).

For clinicians and patients who continue to harbor concerns that cognitive function is threatened by very low LDL-C, this novel approach to evaluating risk is “reassuring,” according to the authors.

Early in clinical testing of PCSK9 inhibitors, a potential signal for adverse effects on cognitive function was reported but unconfirmed. This signal raised concern that extremely low levels of LDL-C, such as < 25 mg/dL, achieved with PCSK9 inhibitors might pose a risk to neurocognitive function.

Of several factors that provided a basis for concern, the PCSK9 enzyme is known to participate in brain development, according to the authors of this newly published study.

Mendelian randomization addresses complex issue

The objective of this Mendelian randomization analysis was to evaluate the relationship of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on long-term neurocognitive function. Used previously to address other clinical issues, a drug-effect Mendelian randomization analysis evaluates genetic variants to determine whether there is a causal relationship between a risk, which in this case was lipid-lowering drugs, to a specific outcome, which was cognitive performance.

By looking directly at genetic variants that simulate the pharmacological inhibition of drug gene targets, the bias of confounders of clinical effects, such as baseline cognitive function, are avoided, according to the authors.

The message from this drug-effect Mendelian analysis was simple, according to the senior author of the study, Falk W. Lohoff, MD, chief of the section on clinical genomics and experimental therapeutics, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

“Based on our data, we do not see a significant cognitive risk profile with PCSK9 inhibition associated with low LDL-C,” Dr. Lohoff said in an interview. He cautioned that “future long-term clinical studies are needed to confirm the absence of this effect,” but he and his coauthors noted that these data concur with the clinical studies.

From genome-wide association studies, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in PCSK9 and HMG-Co A reductase were extracted from a sample of more than 700,000 individuals of predominantly European ancestry. In the analysis, the investigators evaluated whether inhibition of PCSK9 or HMG-Co A reductase had an effect on seven clinical outcomes that relate to neurocognitive function, including memory, verbal intelligence, and reaction time, as well as biomarkers of cognitive function, such as cortical surface area.

The genetic effect of PCSK9 inhibition was “null for every cognitive-related outcome evaluated,” the investigators reported. The genetic effect of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition had a statistically significant but modest effect on cognitive performance (P = .03) and cortical surface area (P = .03). While the impact of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition on reaction time was stronger on a statistical basis (P = .0002), the investigators reported that it translated into a decrease of only 0.067 milliseconds per 38.7 mg/dL. They characterized this as a “small impact” unlikely to outweigh clinical benefits.

In an editorial that accompanied publication of this study, Brian A. Ference, MD, MPhil, provided context for the suitability of a Mendelian randomization analysis to address this or other questions regarding the impact of lipid-lowering therapies on clinical outcomes, and he ultimately concurred with the major conclusions

Ultimately, this analysis is consistent with other evidence that PCSK9 inhibition does not pose a risk of impaired cognitive function, he wrote. For statins, he concluded that this study “does not provide compelling evidence” to challenge their current clinical use.

Data do not support low LDL-C as cognitive risk factor

Moreover, this study – as well as other evidence – argues strongly against very low levels of LDL-C, regardless of how they are achieved, as a risk factor for diminished cognitive function, Dr. Ference, director of research in the division of translational therapeutics, University of Cambridge (England), said in an interview.

“There is no evidence from Mendelian randomization studies that lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C increases the risk of cognitive impairment,” he said. “This is true when evaluating lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C due to genetic variants in a wide variety of different genes or the genes that encode the target PCKS9 inhibitors, statins, or other lipid-lowering therapies.”

In other words, this study “adds to the accumulating evidence” that LDL-C lowering by itself does not contribute to an adverse impact on cognitive function despite persistent concern. This should not be surprising. Dr. Ference emphasized that there has never been strong evidence for an association.

“As I point out in the editorial, there is no biologically plausible mechanism by which reducing peripheral LDL-C should impact neurological function in any way, because the therapies do not cross the blood brain barrier, and because the nervous system produces its own cholesterol to maintain the integrity of membranes in nervous system cells,” he explained.

Dr. Lohoff reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Ference has financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies including those that make lipid-lowering therapies.

PCSK9 inhibitors, which are among the most effective therapies for reducing LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), are associated with a neutral effect on cognitive function, according to a genetics-based Mendelian randomization study intended to sort out through the complexity of confounders.

The same study linked HMG-Co A reductase inhibitors (statins) with the potential for modest adverse neurocognitive effects, although these are likely to be outweighed by cardiovascular benefits, according to a collaborating team of investigators from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the University of Oxford (England).

For clinicians and patients who continue to harbor concerns that cognitive function is threatened by very low LDL-C, this novel approach to evaluating risk is “reassuring,” according to the authors.

Early in clinical testing of PCSK9 inhibitors, a potential signal for adverse effects on cognitive function was reported but unconfirmed. This signal raised concern that extremely low levels of LDL-C, such as < 25 mg/dL, achieved with PCSK9 inhibitors might pose a risk to neurocognitive function.

Of several factors that provided a basis for concern, the PCSK9 enzyme is known to participate in brain development, according to the authors of this newly published study.

Mendelian randomization addresses complex issue

The objective of this Mendelian randomization analysis was to evaluate the relationship of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on long-term neurocognitive function. Used previously to address other clinical issues, a drug-effect Mendelian randomization analysis evaluates genetic variants to determine whether there is a causal relationship between a risk, which in this case was lipid-lowering drugs, to a specific outcome, which was cognitive performance.

By looking directly at genetic variants that simulate the pharmacological inhibition of drug gene targets, the bias of confounders of clinical effects, such as baseline cognitive function, are avoided, according to the authors.

The message from this drug-effect Mendelian analysis was simple, according to the senior author of the study, Falk W. Lohoff, MD, chief of the section on clinical genomics and experimental therapeutics, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

“Based on our data, we do not see a significant cognitive risk profile with PCSK9 inhibition associated with low LDL-C,” Dr. Lohoff said in an interview. He cautioned that “future long-term clinical studies are needed to confirm the absence of this effect,” but he and his coauthors noted that these data concur with the clinical studies.

From genome-wide association studies, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in PCSK9 and HMG-Co A reductase were extracted from a sample of more than 700,000 individuals of predominantly European ancestry. In the analysis, the investigators evaluated whether inhibition of PCSK9 or HMG-Co A reductase had an effect on seven clinical outcomes that relate to neurocognitive function, including memory, verbal intelligence, and reaction time, as well as biomarkers of cognitive function, such as cortical surface area.

The genetic effect of PCSK9 inhibition was “null for every cognitive-related outcome evaluated,” the investigators reported. The genetic effect of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition had a statistically significant but modest effect on cognitive performance (P = .03) and cortical surface area (P = .03). While the impact of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition on reaction time was stronger on a statistical basis (P = .0002), the investigators reported that it translated into a decrease of only 0.067 milliseconds per 38.7 mg/dL. They characterized this as a “small impact” unlikely to outweigh clinical benefits.

In an editorial that accompanied publication of this study, Brian A. Ference, MD, MPhil, provided context for the suitability of a Mendelian randomization analysis to address this or other questions regarding the impact of lipid-lowering therapies on clinical outcomes, and he ultimately concurred with the major conclusions

Ultimately, this analysis is consistent with other evidence that PCSK9 inhibition does not pose a risk of impaired cognitive function, he wrote. For statins, he concluded that this study “does not provide compelling evidence” to challenge their current clinical use.

Data do not support low LDL-C as cognitive risk factor

Moreover, this study – as well as other evidence – argues strongly against very low levels of LDL-C, regardless of how they are achieved, as a risk factor for diminished cognitive function, Dr. Ference, director of research in the division of translational therapeutics, University of Cambridge (England), said in an interview.

“There is no evidence from Mendelian randomization studies that lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C increases the risk of cognitive impairment,” he said. “This is true when evaluating lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C due to genetic variants in a wide variety of different genes or the genes that encode the target PCKS9 inhibitors, statins, or other lipid-lowering therapies.”

In other words, this study “adds to the accumulating evidence” that LDL-C lowering by itself does not contribute to an adverse impact on cognitive function despite persistent concern. This should not be surprising. Dr. Ference emphasized that there has never been strong evidence for an association.

“As I point out in the editorial, there is no biologically plausible mechanism by which reducing peripheral LDL-C should impact neurological function in any way, because the therapies do not cross the blood brain barrier, and because the nervous system produces its own cholesterol to maintain the integrity of membranes in nervous system cells,” he explained.

Dr. Lohoff reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Ference has financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies including those that make lipid-lowering therapies.

PCSK9 inhibitors, which are among the most effective therapies for reducing LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), are associated with a neutral effect on cognitive function, according to a genetics-based Mendelian randomization study intended to sort out through the complexity of confounders.

The same study linked HMG-Co A reductase inhibitors (statins) with the potential for modest adverse neurocognitive effects, although these are likely to be outweighed by cardiovascular benefits, according to a collaborating team of investigators from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the University of Oxford (England).

For clinicians and patients who continue to harbor concerns that cognitive function is threatened by very low LDL-C, this novel approach to evaluating risk is “reassuring,” according to the authors.

Early in clinical testing of PCSK9 inhibitors, a potential signal for adverse effects on cognitive function was reported but unconfirmed. This signal raised concern that extremely low levels of LDL-C, such as < 25 mg/dL, achieved with PCSK9 inhibitors might pose a risk to neurocognitive function.

Of several factors that provided a basis for concern, the PCSK9 enzyme is known to participate in brain development, according to the authors of this newly published study.

Mendelian randomization addresses complex issue

The objective of this Mendelian randomization analysis was to evaluate the relationship of PCSK9 inhibitors and statins on long-term neurocognitive function. Used previously to address other clinical issues, a drug-effect Mendelian randomization analysis evaluates genetic variants to determine whether there is a causal relationship between a risk, which in this case was lipid-lowering drugs, to a specific outcome, which was cognitive performance.

By looking directly at genetic variants that simulate the pharmacological inhibition of drug gene targets, the bias of confounders of clinical effects, such as baseline cognitive function, are avoided, according to the authors.

The message from this drug-effect Mendelian analysis was simple, according to the senior author of the study, Falk W. Lohoff, MD, chief of the section on clinical genomics and experimental therapeutics, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

“Based on our data, we do not see a significant cognitive risk profile with PCSK9 inhibition associated with low LDL-C,” Dr. Lohoff said in an interview. He cautioned that “future long-term clinical studies are needed to confirm the absence of this effect,” but he and his coauthors noted that these data concur with the clinical studies.

From genome-wide association studies, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in PCSK9 and HMG-Co A reductase were extracted from a sample of more than 700,000 individuals of predominantly European ancestry. In the analysis, the investigators evaluated whether inhibition of PCSK9 or HMG-Co A reductase had an effect on seven clinical outcomes that relate to neurocognitive function, including memory, verbal intelligence, and reaction time, as well as biomarkers of cognitive function, such as cortical surface area.

The genetic effect of PCSK9 inhibition was “null for every cognitive-related outcome evaluated,” the investigators reported. The genetic effect of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition had a statistically significant but modest effect on cognitive performance (P = .03) and cortical surface area (P = .03). While the impact of HMG-Co A reductase inhibition on reaction time was stronger on a statistical basis (P = .0002), the investigators reported that it translated into a decrease of only 0.067 milliseconds per 38.7 mg/dL. They characterized this as a “small impact” unlikely to outweigh clinical benefits.

In an editorial that accompanied publication of this study, Brian A. Ference, MD, MPhil, provided context for the suitability of a Mendelian randomization analysis to address this or other questions regarding the impact of lipid-lowering therapies on clinical outcomes, and he ultimately concurred with the major conclusions

Ultimately, this analysis is consistent with other evidence that PCSK9 inhibition does not pose a risk of impaired cognitive function, he wrote. For statins, he concluded that this study “does not provide compelling evidence” to challenge their current clinical use.

Data do not support low LDL-C as cognitive risk factor

Moreover, this study – as well as other evidence – argues strongly against very low levels of LDL-C, regardless of how they are achieved, as a risk factor for diminished cognitive function, Dr. Ference, director of research in the division of translational therapeutics, University of Cambridge (England), said in an interview.

“There is no evidence from Mendelian randomization studies that lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C increases the risk of cognitive impairment,” he said. “This is true when evaluating lifelong exposure to lower LDL-C due to genetic variants in a wide variety of different genes or the genes that encode the target PCKS9 inhibitors, statins, or other lipid-lowering therapies.”

In other words, this study “adds to the accumulating evidence” that LDL-C lowering by itself does not contribute to an adverse impact on cognitive function despite persistent concern. This should not be surprising. Dr. Ference emphasized that there has never been strong evidence for an association.

“As I point out in the editorial, there is no biologically plausible mechanism by which reducing peripheral LDL-C should impact neurological function in any way, because the therapies do not cross the blood brain barrier, and because the nervous system produces its own cholesterol to maintain the integrity of membranes in nervous system cells,” he explained.

Dr. Lohoff reports no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Ference has financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies including those that make lipid-lowering therapies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Is prostasin a clue to diabetes/cancer link?

People with elevated levels of protein prostasin seem to have a higher risk of developing diabetes and dying from cancer, according to a large, prospective, population-based study. The finding may provide new insights into why people with diabetes have an increased risk of cancer.

The study claims to be the first to investigate the link between plasma prostasin levels and cancer mortality, the study authors wrote in Diabetologia. The study analyzed plasma prostasin samples from 4,297 older adults (average age, 57.5 years) from the Malmö (Sweden) Diet and Cancer Study Cardiovascular Cohort.

“This study from the general population shows that prostasin, a protein that could be measured in blood, is associated with increased risk of developing diabetes,” senior author Gunnar Engström, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Lund University in Malmö, Sweden, said in a comment. “Furthermore, it was associated with increased risk of death from cancer, especially in individuals with elevated glucose levels in the prediabetic range.

“The relationship between diabetes and cancer is poorly understood,” Dr. Engström said. “To our knowledge, this is the first big population study of prostasin and risk of diabetes.”

He noted previous studies have found a relationship between prostasin and cancer outcomes. “Prostasin could be a possible shared link between the two diseases and the results could help us understand why individuals with diabetes have increased risk of cancer.”

Patients in the study were assigned to quartiles based on prostasin levels. Those in the highest quartile had almost twice the risk of prevalent diabetes than did those in the lowest quartile (adjusted odds ratio, 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.39-2.76; P < .0001).

During the follow-up periods of 21.9 years for diabetes and 23.5 years for cancer, on average, 702 participants developed diabetes and 651 died from cancer. Again, the analysis found a significantly higher adjusted hazard ratio for participants in the fourth quartile: about 75% higher for diabetes (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.41-2.19; P < .0001), and, after multivariable analysis, about 40% higher for death from cancer (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.14-1.8; P = .0008).

Potential diabetes-cancer ‘interaction’

The study also identified what it called “a significant interaction” between prostasin and fasting blood glucose for cancer mortality risk (P = .022). In patients with impaired fasting blood glucose levels at baseline, the risk for cancer mortality was about 50% greater with each standard deviation increase in prostasin (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.07-2.16; P = .019). Those with normal fasting blood glucose at baseline had a significantly lower risk with each SD increase in prostasin (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21; P = .025).

Further research is needed to validate the potential of prostasin as a biomarker for diabetes and cancer risks, Dr. Engström said. “The results need to be replicated in other studies. A study of cancer mortality in a big cohort of diabetes patients would be of great interest. We also need to examine whether prostasin is causally related to cancer and/or diabetes, or whether prostasin could act as a valuable risk marker in clinical settings. If causal, there could a possible molecular target for treatment.”

He added: “Biomarkers of diabetes and cancer are of great interest in the era of personalized medicine, both for disease prevention and for treatment of those with established disease.”

Li-Mei Chen, MD, PhD, a research associate professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, has studied the role of prostasin in epidemiology. She noted that one of the challenges of using prostasin in clinical or research settings is the lack of a standardized assay, which the Malmö study acknowledged. Dr. Engström and colleagues wrote that “prostasin levels were measured in arbitrary units (NPX values), and thus could not be compared directly with absolute values.”

Dr. Chen pointed out that the study reported a lower range of 0.24 pg/mL and an upper range of 7,800 pg/mL.

This means that, “in different groups that measure prostasin, the absolute quantity could have a difference in the thousands or tens of thousands,” she said. “That makes the judgment difficult of whether for this person you have a high level of prostasin in the blood and the other one you don’t if the difference is over a thousandfold.”

The Malmö study used the Proseek Multiplex Oncology I panel to determine plasma prostasin concentration, but Dr. Chen noted that she couldn’t find any data validating the panel for measuring prostasin. “It’s really hard for me to say whether this is of value or not because if the method that generated the data is not verified by another method, you don’t really know what you’re measuring.

“If the data are questionable, it’s really hard to say whether it means whether it’s a marker for cancer or diabetes,” Dr. Chen added. “That’s the biggest question I have, but actually the authors realize that.”

Dr. Engström confirmed that, “if prostasin is used to identify patients with increased risk of diabetes and cancer mortality, we also need to develop standardized assays for clinical use.”

Dr. Engström and coauthors had no disclosures. The study received funding from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province. The Malmö Diet and Cancer study received grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Medical Research Council, AFA Insurance, the Albert Påhlsson and Gunnar Nilsson Foundations, Malmö City Council, and Lund University. Dr. Chen had no relevant disclosures.

People with elevated levels of protein prostasin seem to have a higher risk of developing diabetes and dying from cancer, according to a large, prospective, population-based study. The finding may provide new insights into why people with diabetes have an increased risk of cancer.

The study claims to be the first to investigate the link between plasma prostasin levels and cancer mortality, the study authors wrote in Diabetologia. The study analyzed plasma prostasin samples from 4,297 older adults (average age, 57.5 years) from the Malmö (Sweden) Diet and Cancer Study Cardiovascular Cohort.

“This study from the general population shows that prostasin, a protein that could be measured in blood, is associated with increased risk of developing diabetes,” senior author Gunnar Engström, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Lund University in Malmö, Sweden, said in a comment. “Furthermore, it was associated with increased risk of death from cancer, especially in individuals with elevated glucose levels in the prediabetic range.

“The relationship between diabetes and cancer is poorly understood,” Dr. Engström said. “To our knowledge, this is the first big population study of prostasin and risk of diabetes.”

He noted previous studies have found a relationship between prostasin and cancer outcomes. “Prostasin could be a possible shared link between the two diseases and the results could help us understand why individuals with diabetes have increased risk of cancer.”

Patients in the study were assigned to quartiles based on prostasin levels. Those in the highest quartile had almost twice the risk of prevalent diabetes than did those in the lowest quartile (adjusted odds ratio, 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.39-2.76; P < .0001).

During the follow-up periods of 21.9 years for diabetes and 23.5 years for cancer, on average, 702 participants developed diabetes and 651 died from cancer. Again, the analysis found a significantly higher adjusted hazard ratio for participants in the fourth quartile: about 75% higher for diabetes (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.41-2.19; P < .0001), and, after multivariable analysis, about 40% higher for death from cancer (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.14-1.8; P = .0008).

Potential diabetes-cancer ‘interaction’

The study also identified what it called “a significant interaction” between prostasin and fasting blood glucose for cancer mortality risk (P = .022). In patients with impaired fasting blood glucose levels at baseline, the risk for cancer mortality was about 50% greater with each standard deviation increase in prostasin (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.07-2.16; P = .019). Those with normal fasting blood glucose at baseline had a significantly lower risk with each SD increase in prostasin (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21; P = .025).

Further research is needed to validate the potential of prostasin as a biomarker for diabetes and cancer risks, Dr. Engström said. “The results need to be replicated in other studies. A study of cancer mortality in a big cohort of diabetes patients would be of great interest. We also need to examine whether prostasin is causally related to cancer and/or diabetes, or whether prostasin could act as a valuable risk marker in clinical settings. If causal, there could a possible molecular target for treatment.”

He added: “Biomarkers of diabetes and cancer are of great interest in the era of personalized medicine, both for disease prevention and for treatment of those with established disease.”

Li-Mei Chen, MD, PhD, a research associate professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, has studied the role of prostasin in epidemiology. She noted that one of the challenges of using prostasin in clinical or research settings is the lack of a standardized assay, which the Malmö study acknowledged. Dr. Engström and colleagues wrote that “prostasin levels were measured in arbitrary units (NPX values), and thus could not be compared directly with absolute values.”

Dr. Chen pointed out that the study reported a lower range of 0.24 pg/mL and an upper range of 7,800 pg/mL.

This means that, “in different groups that measure prostasin, the absolute quantity could have a difference in the thousands or tens of thousands,” she said. “That makes the judgment difficult of whether for this person you have a high level of prostasin in the blood and the other one you don’t if the difference is over a thousandfold.”

The Malmö study used the Proseek Multiplex Oncology I panel to determine plasma prostasin concentration, but Dr. Chen noted that she couldn’t find any data validating the panel for measuring prostasin. “It’s really hard for me to say whether this is of value or not because if the method that generated the data is not verified by another method, you don’t really know what you’re measuring.

“If the data are questionable, it’s really hard to say whether it means whether it’s a marker for cancer or diabetes,” Dr. Chen added. “That’s the biggest question I have, but actually the authors realize that.”

Dr. Engström confirmed that, “if prostasin is used to identify patients with increased risk of diabetes and cancer mortality, we also need to develop standardized assays for clinical use.”

Dr. Engström and coauthors had no disclosures. The study received funding from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province. The Malmö Diet and Cancer study received grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Medical Research Council, AFA Insurance, the Albert Påhlsson and Gunnar Nilsson Foundations, Malmö City Council, and Lund University. Dr. Chen had no relevant disclosures.

People with elevated levels of protein prostasin seem to have a higher risk of developing diabetes and dying from cancer, according to a large, prospective, population-based study. The finding may provide new insights into why people with diabetes have an increased risk of cancer.

The study claims to be the first to investigate the link between plasma prostasin levels and cancer mortality, the study authors wrote in Diabetologia. The study analyzed plasma prostasin samples from 4,297 older adults (average age, 57.5 years) from the Malmö (Sweden) Diet and Cancer Study Cardiovascular Cohort.

“This study from the general population shows that prostasin, a protein that could be measured in blood, is associated with increased risk of developing diabetes,” senior author Gunnar Engström, MD, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Lund University in Malmö, Sweden, said in a comment. “Furthermore, it was associated with increased risk of death from cancer, especially in individuals with elevated glucose levels in the prediabetic range.

“The relationship between diabetes and cancer is poorly understood,” Dr. Engström said. “To our knowledge, this is the first big population study of prostasin and risk of diabetes.”

He noted previous studies have found a relationship between prostasin and cancer outcomes. “Prostasin could be a possible shared link between the two diseases and the results could help us understand why individuals with diabetes have increased risk of cancer.”

Patients in the study were assigned to quartiles based on prostasin levels. Those in the highest quartile had almost twice the risk of prevalent diabetes than did those in the lowest quartile (adjusted odds ratio, 1.95; 95% confidence interval, 1.39-2.76; P < .0001).

During the follow-up periods of 21.9 years for diabetes and 23.5 years for cancer, on average, 702 participants developed diabetes and 651 died from cancer. Again, the analysis found a significantly higher adjusted hazard ratio for participants in the fourth quartile: about 75% higher for diabetes (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.41-2.19; P < .0001), and, after multivariable analysis, about 40% higher for death from cancer (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.14-1.8; P = .0008).

Potential diabetes-cancer ‘interaction’

The study also identified what it called “a significant interaction” between prostasin and fasting blood glucose for cancer mortality risk (P = .022). In patients with impaired fasting blood glucose levels at baseline, the risk for cancer mortality was about 50% greater with each standard deviation increase in prostasin (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.07-2.16; P = .019). Those with normal fasting blood glucose at baseline had a significantly lower risk with each SD increase in prostasin (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21; P = .025).

Further research is needed to validate the potential of prostasin as a biomarker for diabetes and cancer risks, Dr. Engström said. “The results need to be replicated in other studies. A study of cancer mortality in a big cohort of diabetes patients would be of great interest. We also need to examine whether prostasin is causally related to cancer and/or diabetes, or whether prostasin could act as a valuable risk marker in clinical settings. If causal, there could a possible molecular target for treatment.”

He added: “Biomarkers of diabetes and cancer are of great interest in the era of personalized medicine, both for disease prevention and for treatment of those with established disease.”

Li-Mei Chen, MD, PhD, a research associate professor at the University of Central Florida, Orlando, has studied the role of prostasin in epidemiology. She noted that one of the challenges of using prostasin in clinical or research settings is the lack of a standardized assay, which the Malmö study acknowledged. Dr. Engström and colleagues wrote that “prostasin levels were measured in arbitrary units (NPX values), and thus could not be compared directly with absolute values.”

Dr. Chen pointed out that the study reported a lower range of 0.24 pg/mL and an upper range of 7,800 pg/mL.

This means that, “in different groups that measure prostasin, the absolute quantity could have a difference in the thousands or tens of thousands,” she said. “That makes the judgment difficult of whether for this person you have a high level of prostasin in the blood and the other one you don’t if the difference is over a thousandfold.”

The Malmö study used the Proseek Multiplex Oncology I panel to determine plasma prostasin concentration, but Dr. Chen noted that she couldn’t find any data validating the panel for measuring prostasin. “It’s really hard for me to say whether this is of value or not because if the method that generated the data is not verified by another method, you don’t really know what you’re measuring.

“If the data are questionable, it’s really hard to say whether it means whether it’s a marker for cancer or diabetes,” Dr. Chen added. “That’s the biggest question I have, but actually the authors realize that.”

Dr. Engström confirmed that, “if prostasin is used to identify patients with increased risk of diabetes and cancer mortality, we also need to develop standardized assays for clinical use.”

Dr. Engström and coauthors had no disclosures. The study received funding from the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province. The Malmö Diet and Cancer study received grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Medical Research Council, AFA Insurance, the Albert Påhlsson and Gunnar Nilsson Foundations, Malmö City Council, and Lund University. Dr. Chen had no relevant disclosures.

FROM DIABETOLOGIA

Many patients with acute anterior uveitis may have undiagnosed spondyloarthritis

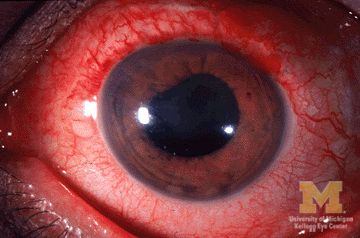

More than half of patients with noninfectious acute anterior uveitis seen in ophthalmology clinics in a new cross-sectional study were found by rheumatologists to have spondyloarthritis (SpA), prompting the researchers to recommend referring “all patients with AAU reporting musculoskeletal symptoms to rheumatologists.”

The results also suggest that “rheumatologists should consider that SpA in AAU patients might present ‘atypically’ with no or mild back pain starting after the age of 45 years and lasting shorter than 3 months,” according to first author Judith Rademacher, MD, and colleagues at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, who published their work online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

During July 2017–April 2021, the study team prospectively assessed 189 consecutive adult patients with noninfectious AAU at ophthalmology clinics in the Berlin area. The patients had rheumatologic examinations and underwent pelvic x-ray if they had back pain as well as MRI of sacroiliac joints regardless of back pain unless there was a contraindication. The patients had a mean age of nearly 41 years, and 54.5% were male.

Of the 189 patients with AAU, the researchers diagnosed SpA in 106, including 74 (70%) who had been previously undiagnosed. A total of 99 (93%) had predominately axial SpA, and 7 (7%) had peripheral SpA.

A multivariable logistic regression assessment found that male sex (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-4.2), HLA-B27 positivity (OR, 6.3; 95% CI, 2.4-16.4), elevated C-reactive protein (OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 1.9-12.4), and psoriasis (OR, 12.5; 95% CI, 1.3-120.2) were significantly associated with SpA in patients with AAU. No ophthalmologic factors were significantly associated with SpA.

Among all patients, an adaptation of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) referral tool demonstrated lower specificity for SpA recognition than did the Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool (28% vs. 42%). The ASAS referral took had a slightly greater sensitivity than the Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool (80% vs. 78%).

“Taking into account only AAU patients without prior diagnosis of SpA, a rheumatologist would have to see 2.1 patients fulfilling the ASAS tool or 1.9 patients fulfilling the DUET to diagnose one patient with SpA. However, with both referral strategies more than 20% of SpA patients would have been missed,” the researchers wrote. “This might be due to an ‘unusual presentation’ of SpA in those patients as their back pain started more often after the age of 45 years, lasted shorter than 3 months and thus, ASAS classification criteria were less frequently fulfilled.”