User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

JAMA podcast on racism in medicine faces backlash

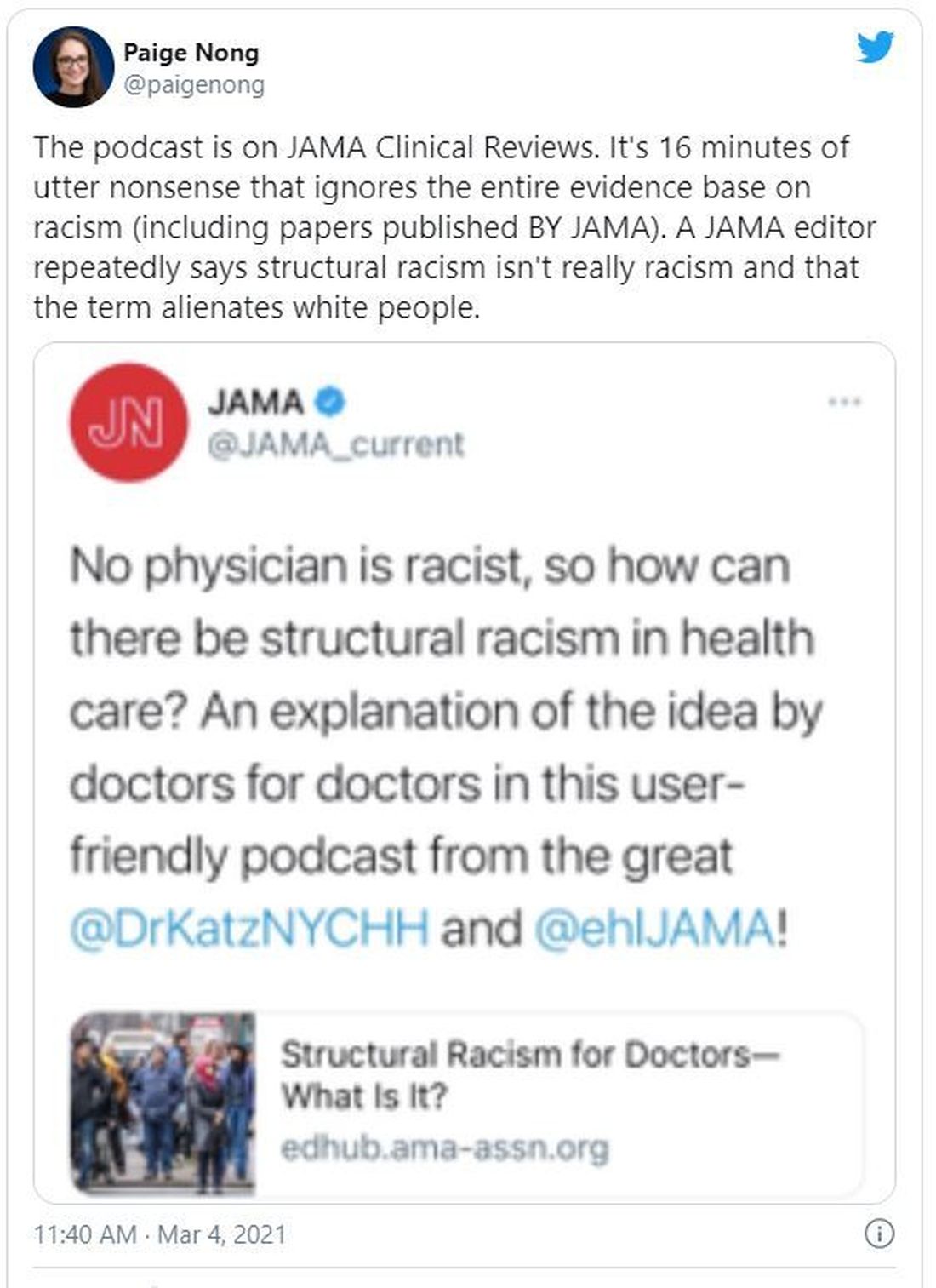

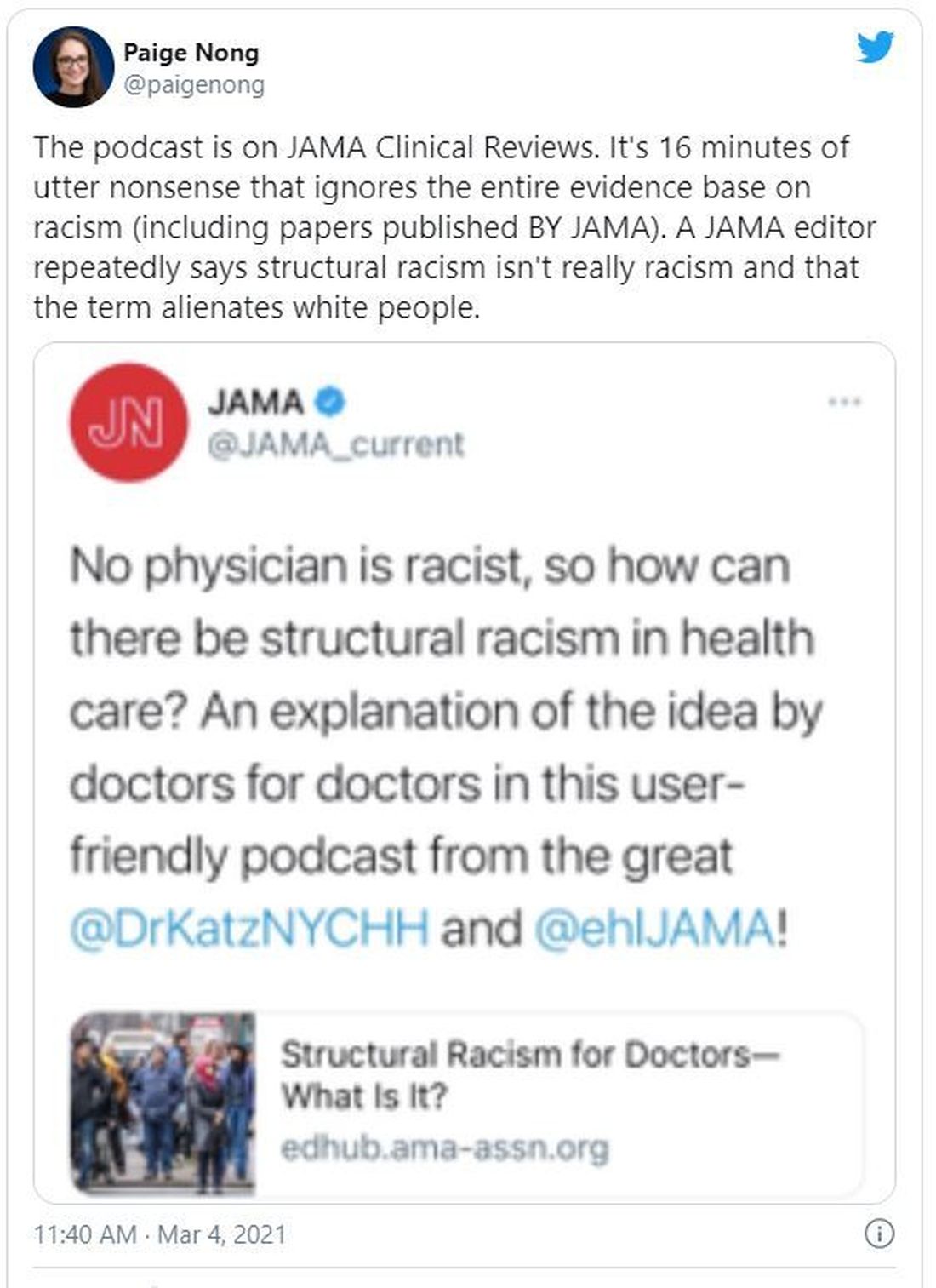

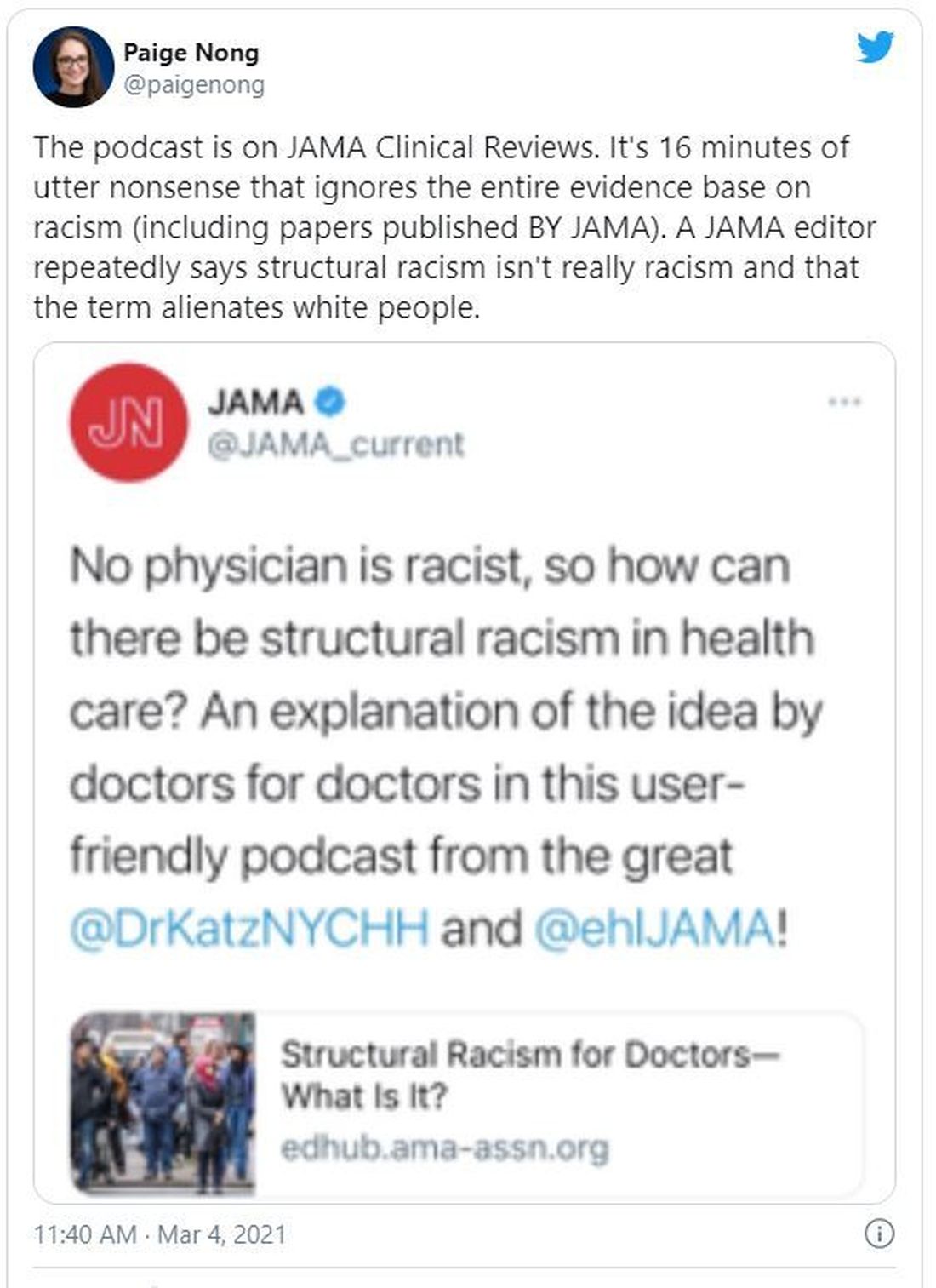

Published on Feb. 23, the episode is hosted on JAMA’s learning platform for doctors and is available for continuing medical education credits.

“No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast,” JAMA wrote in a Twitter post to promote the episode. That tweet has since been deleted.

The episode features host Ed Livingston, MD, deputy editor for clinical reviews and education at JAMA, and guest Mitchell Katz, MD, president and CEO for NYC Health + Hospitals and deputy editor for JAMA Internal Medicine. Dr. Livingston approaches the episode as “structural racism for skeptics,” and Dr. Katz tries to explain how structural racism deepens health disparities and what health systems can do about it.

“Many physicians are skeptical of structural racism, the idea that economic, educational, and other societal systems preferentially disadvantage Black Americans and other communities of color,” the episode description says.

In the podcast, Dr. Livingston and Dr. Katz speak about health care disparities and racial inequality. Dr. Livingston, who says he “didn’t understand the concept” going into the episode, suggests that racism was made illegal in the 1960s and that the discussion of “structural racism” should shift away from the term “racism” and focus on socioeconomic status instead.

“What you’re talking about isn’t so much racism ... it isn’t their race, it isn’t their color, it’s their socioeconomic status,” Dr. Livingston says. “Is that a fair statement?”

But Dr. Katz says that “acknowledging structural racism can be helpful to us. Structural racism refers to a system in which policies or practices or how we look at people perpetuates racial inequality.”

Dr. Katz points to the creation of a hospital in San Francisco in the 1880s to treat patients of Chinese ethnicity separately. Outside of health care, he talks about environmental racism between neighborhoods with inequalities in hospitals, schools, and social services.

“All of those things have an impact on that minority person,” Dr. Katz says. “The big thing we can all do is move away from trying to interrogate each other’s opinions and move to a place where we are looking at the policies of our institutions and making sure that they promote equality.”

Dr. Livingston concludes the episode by reemphasizing that “racism” should be taken out of the conversation and it should instead focus on the “structural” aspect of socioeconomics.

“Minorities ... aren’t [in those neighborhoods] because they’re not allowed to buy houses or they can’t get a job because they’re Black or Hispanic. That would be illegal,” Dr. Livingston says. “But disproportionality does exist.”

Efforts to reach Dr. Livingston were unsuccessful. Dr. Katz distanced himself from Dr. Livingston in a statement released on March 4.

“Systemic and interpersonal racism both still exist in our country — they must be rooted out. I do not share the JAMA host’s belief of doing away with the word ‘racism’ will help us be more successful in ending inequities that exists across racial and ethnic lines,” Dr. Katz said. “Further, I believe that we will only produce an equitable society when social and political structures do not continue to produce and perpetuate disparate results based on social race and ethnicity.”

Dr. Katz reiterated that both interpersonal and structural racism continue to exist in the United States, “and it is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it.”

He also recommended JAMA use this controversy “as a learning opportunity for continued dialogue and create another podcast series as an open conversation that invites diverse experts in the field to have an open discussion about structural racism in healthcare.”

The podcast and JAMA’s tweet promoting it were widely criticized on Twitter. In interviews with WebMD, many doctors expressed disbelief that such a respected journal would lend its name to this podcast episode.

B. Bobby Chiong, MD, a radiologist in New York, said although JAMA’s effort to engage with its audience about racism is laudable, it missed the mark.

“I think the backlash comes from how they tried to make a podcast about the subject and somehow made themselves an example of unconscious bias and unfamiliarity with just how embedded in our system is structural racism,” he said.

Perhaps the podcast’s worst offense was its failure to address the painful history of racial bias in this country that still permeates the medical community, says Tamara Saint-Surin, MD, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“For physicians in leadership to have the belief that structural racism does not exist in medicine, they don’t really appreciate what affects their patients and what their patients were dealing with,” Dr. Saint-Surin said in an interview. “It was a very harmful podcast and goes to show we still have so much work to do.”

Along with a flawed premise, she says, the podcast was not nearly long enough to address such a nuanced issue. And Dr. Livingston focused on interpersonal racism rather than structural racism, she said, failing to address widespread problems such as higher rates of asthma among Black populations living in areas with poor air quality.

The number of Black doctors remains low and the lack of representation adds to an environment already rife with racism, according to many medical professionals.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, an internal medicine doctor in Chicago, said JAMA failed to live up to its own standards by publishing material that lacked research and expertise.

“I can’t submit a clinical trial to JAMA without them combing through methods with a fine-tooth comb,” Dr. Obuobi said. “They didn’t uphold the standards they normally apply to anyone else.”

Both the editor of JAMA and the head of the American Medical Association issued statements criticizing the episode and the tweet that promoted it.

JAMA Editor-in-Chief Howard Bauchner, MD, said, “The language of the tweet, and some portions of the podcast, do not reflect my commitment as editorial leader of JAMA and JAMA Network to call out and discuss the adverse effects of injustice, inequity, and racism in society and medicine as JAMA has done for many years.” He said JAMA will schedule a future podcast to address the concerns raised about the recent episode.

AMA CEO James L. Madara, MD, said, “The AMA’s House of Delegates passed policy stating that racism is structural, systemic, cultural, and interpersonal, and we are deeply disturbed – and angered – by a recent JAMA podcast that questioned the existence of structural racism and the affiliated tweet that promoted the podcast and stated ‘no physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?’ ”

He continued: “JAMA has editorial independence from AMA, but this tweet and podcast are inconsistent with the policies and views of AMA, and I’m concerned about and acknowledge the harms they have caused. Structural racism in health care and our society exists, and it is incumbent on all of us to fix it.”

This article was updated 3/5/21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Published on Feb. 23, the episode is hosted on JAMA’s learning platform for doctors and is available for continuing medical education credits.

“No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast,” JAMA wrote in a Twitter post to promote the episode. That tweet has since been deleted.

The episode features host Ed Livingston, MD, deputy editor for clinical reviews and education at JAMA, and guest Mitchell Katz, MD, president and CEO for NYC Health + Hospitals and deputy editor for JAMA Internal Medicine. Dr. Livingston approaches the episode as “structural racism for skeptics,” and Dr. Katz tries to explain how structural racism deepens health disparities and what health systems can do about it.

“Many physicians are skeptical of structural racism, the idea that economic, educational, and other societal systems preferentially disadvantage Black Americans and other communities of color,” the episode description says.

In the podcast, Dr. Livingston and Dr. Katz speak about health care disparities and racial inequality. Dr. Livingston, who says he “didn’t understand the concept” going into the episode, suggests that racism was made illegal in the 1960s and that the discussion of “structural racism” should shift away from the term “racism” and focus on socioeconomic status instead.

“What you’re talking about isn’t so much racism ... it isn’t their race, it isn’t their color, it’s their socioeconomic status,” Dr. Livingston says. “Is that a fair statement?”

But Dr. Katz says that “acknowledging structural racism can be helpful to us. Structural racism refers to a system in which policies or practices or how we look at people perpetuates racial inequality.”

Dr. Katz points to the creation of a hospital in San Francisco in the 1880s to treat patients of Chinese ethnicity separately. Outside of health care, he talks about environmental racism between neighborhoods with inequalities in hospitals, schools, and social services.

“All of those things have an impact on that minority person,” Dr. Katz says. “The big thing we can all do is move away from trying to interrogate each other’s opinions and move to a place where we are looking at the policies of our institutions and making sure that they promote equality.”

Dr. Livingston concludes the episode by reemphasizing that “racism” should be taken out of the conversation and it should instead focus on the “structural” aspect of socioeconomics.

“Minorities ... aren’t [in those neighborhoods] because they’re not allowed to buy houses or they can’t get a job because they’re Black or Hispanic. That would be illegal,” Dr. Livingston says. “But disproportionality does exist.”

Efforts to reach Dr. Livingston were unsuccessful. Dr. Katz distanced himself from Dr. Livingston in a statement released on March 4.

“Systemic and interpersonal racism both still exist in our country — they must be rooted out. I do not share the JAMA host’s belief of doing away with the word ‘racism’ will help us be more successful in ending inequities that exists across racial and ethnic lines,” Dr. Katz said. “Further, I believe that we will only produce an equitable society when social and political structures do not continue to produce and perpetuate disparate results based on social race and ethnicity.”

Dr. Katz reiterated that both interpersonal and structural racism continue to exist in the United States, “and it is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it.”

He also recommended JAMA use this controversy “as a learning opportunity for continued dialogue and create another podcast series as an open conversation that invites diverse experts in the field to have an open discussion about structural racism in healthcare.”

The podcast and JAMA’s tweet promoting it were widely criticized on Twitter. In interviews with WebMD, many doctors expressed disbelief that such a respected journal would lend its name to this podcast episode.

B. Bobby Chiong, MD, a radiologist in New York, said although JAMA’s effort to engage with its audience about racism is laudable, it missed the mark.

“I think the backlash comes from how they tried to make a podcast about the subject and somehow made themselves an example of unconscious bias and unfamiliarity with just how embedded in our system is structural racism,” he said.

Perhaps the podcast’s worst offense was its failure to address the painful history of racial bias in this country that still permeates the medical community, says Tamara Saint-Surin, MD, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“For physicians in leadership to have the belief that structural racism does not exist in medicine, they don’t really appreciate what affects their patients and what their patients were dealing with,” Dr. Saint-Surin said in an interview. “It was a very harmful podcast and goes to show we still have so much work to do.”

Along with a flawed premise, she says, the podcast was not nearly long enough to address such a nuanced issue. And Dr. Livingston focused on interpersonal racism rather than structural racism, she said, failing to address widespread problems such as higher rates of asthma among Black populations living in areas with poor air quality.

The number of Black doctors remains low and the lack of representation adds to an environment already rife with racism, according to many medical professionals.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, an internal medicine doctor in Chicago, said JAMA failed to live up to its own standards by publishing material that lacked research and expertise.

“I can’t submit a clinical trial to JAMA without them combing through methods with a fine-tooth comb,” Dr. Obuobi said. “They didn’t uphold the standards they normally apply to anyone else.”

Both the editor of JAMA and the head of the American Medical Association issued statements criticizing the episode and the tweet that promoted it.

JAMA Editor-in-Chief Howard Bauchner, MD, said, “The language of the tweet, and some portions of the podcast, do not reflect my commitment as editorial leader of JAMA and JAMA Network to call out and discuss the adverse effects of injustice, inequity, and racism in society and medicine as JAMA has done for many years.” He said JAMA will schedule a future podcast to address the concerns raised about the recent episode.

AMA CEO James L. Madara, MD, said, “The AMA’s House of Delegates passed policy stating that racism is structural, systemic, cultural, and interpersonal, and we are deeply disturbed – and angered – by a recent JAMA podcast that questioned the existence of structural racism and the affiliated tweet that promoted the podcast and stated ‘no physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?’ ”

He continued: “JAMA has editorial independence from AMA, but this tweet and podcast are inconsistent with the policies and views of AMA, and I’m concerned about and acknowledge the harms they have caused. Structural racism in health care and our society exists, and it is incumbent on all of us to fix it.”

This article was updated 3/5/21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Published on Feb. 23, the episode is hosted on JAMA’s learning platform for doctors and is available for continuing medical education credits.

“No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast,” JAMA wrote in a Twitter post to promote the episode. That tweet has since been deleted.

The episode features host Ed Livingston, MD, deputy editor for clinical reviews and education at JAMA, and guest Mitchell Katz, MD, president and CEO for NYC Health + Hospitals and deputy editor for JAMA Internal Medicine. Dr. Livingston approaches the episode as “structural racism for skeptics,” and Dr. Katz tries to explain how structural racism deepens health disparities and what health systems can do about it.

“Many physicians are skeptical of structural racism, the idea that economic, educational, and other societal systems preferentially disadvantage Black Americans and other communities of color,” the episode description says.

In the podcast, Dr. Livingston and Dr. Katz speak about health care disparities and racial inequality. Dr. Livingston, who says he “didn’t understand the concept” going into the episode, suggests that racism was made illegal in the 1960s and that the discussion of “structural racism” should shift away from the term “racism” and focus on socioeconomic status instead.

“What you’re talking about isn’t so much racism ... it isn’t their race, it isn’t their color, it’s their socioeconomic status,” Dr. Livingston says. “Is that a fair statement?”

But Dr. Katz says that “acknowledging structural racism can be helpful to us. Structural racism refers to a system in which policies or practices or how we look at people perpetuates racial inequality.”

Dr. Katz points to the creation of a hospital in San Francisco in the 1880s to treat patients of Chinese ethnicity separately. Outside of health care, he talks about environmental racism between neighborhoods with inequalities in hospitals, schools, and social services.

“All of those things have an impact on that minority person,” Dr. Katz says. “The big thing we can all do is move away from trying to interrogate each other’s opinions and move to a place where we are looking at the policies of our institutions and making sure that they promote equality.”

Dr. Livingston concludes the episode by reemphasizing that “racism” should be taken out of the conversation and it should instead focus on the “structural” aspect of socioeconomics.

“Minorities ... aren’t [in those neighborhoods] because they’re not allowed to buy houses or they can’t get a job because they’re Black or Hispanic. That would be illegal,” Dr. Livingston says. “But disproportionality does exist.”

Efforts to reach Dr. Livingston were unsuccessful. Dr. Katz distanced himself from Dr. Livingston in a statement released on March 4.

“Systemic and interpersonal racism both still exist in our country — they must be rooted out. I do not share the JAMA host’s belief of doing away with the word ‘racism’ will help us be more successful in ending inequities that exists across racial and ethnic lines,” Dr. Katz said. “Further, I believe that we will only produce an equitable society when social and political structures do not continue to produce and perpetuate disparate results based on social race and ethnicity.”

Dr. Katz reiterated that both interpersonal and structural racism continue to exist in the United States, “and it is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it.”

He also recommended JAMA use this controversy “as a learning opportunity for continued dialogue and create another podcast series as an open conversation that invites diverse experts in the field to have an open discussion about structural racism in healthcare.”

The podcast and JAMA’s tweet promoting it were widely criticized on Twitter. In interviews with WebMD, many doctors expressed disbelief that such a respected journal would lend its name to this podcast episode.

B. Bobby Chiong, MD, a radiologist in New York, said although JAMA’s effort to engage with its audience about racism is laudable, it missed the mark.

“I think the backlash comes from how they tried to make a podcast about the subject and somehow made themselves an example of unconscious bias and unfamiliarity with just how embedded in our system is structural racism,” he said.

Perhaps the podcast’s worst offense was its failure to address the painful history of racial bias in this country that still permeates the medical community, says Tamara Saint-Surin, MD, assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“For physicians in leadership to have the belief that structural racism does not exist in medicine, they don’t really appreciate what affects their patients and what their patients were dealing with,” Dr. Saint-Surin said in an interview. “It was a very harmful podcast and goes to show we still have so much work to do.”

Along with a flawed premise, she says, the podcast was not nearly long enough to address such a nuanced issue. And Dr. Livingston focused on interpersonal racism rather than structural racism, she said, failing to address widespread problems such as higher rates of asthma among Black populations living in areas with poor air quality.

The number of Black doctors remains low and the lack of representation adds to an environment already rife with racism, according to many medical professionals.

Shirlene Obuobi, MD, an internal medicine doctor in Chicago, said JAMA failed to live up to its own standards by publishing material that lacked research and expertise.

“I can’t submit a clinical trial to JAMA without them combing through methods with a fine-tooth comb,” Dr. Obuobi said. “They didn’t uphold the standards they normally apply to anyone else.”

Both the editor of JAMA and the head of the American Medical Association issued statements criticizing the episode and the tweet that promoted it.

JAMA Editor-in-Chief Howard Bauchner, MD, said, “The language of the tweet, and some portions of the podcast, do not reflect my commitment as editorial leader of JAMA and JAMA Network to call out and discuss the adverse effects of injustice, inequity, and racism in society and medicine as JAMA has done for many years.” He said JAMA will schedule a future podcast to address the concerns raised about the recent episode.

AMA CEO James L. Madara, MD, said, “The AMA’s House of Delegates passed policy stating that racism is structural, systemic, cultural, and interpersonal, and we are deeply disturbed – and angered – by a recent JAMA podcast that questioned the existence of structural racism and the affiliated tweet that promoted the podcast and stated ‘no physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care?’ ”

He continued: “JAMA has editorial independence from AMA, but this tweet and podcast are inconsistent with the policies and views of AMA, and I’m concerned about and acknowledge the harms they have caused. Structural racism in health care and our society exists, and it is incumbent on all of us to fix it.”

This article was updated 3/5/21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

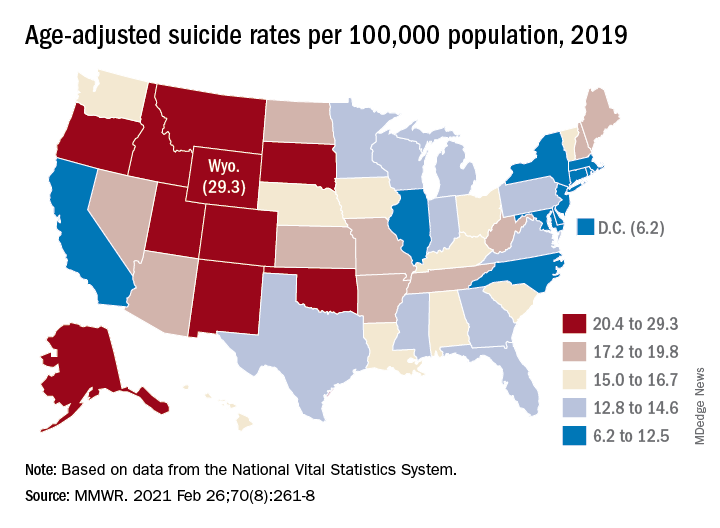

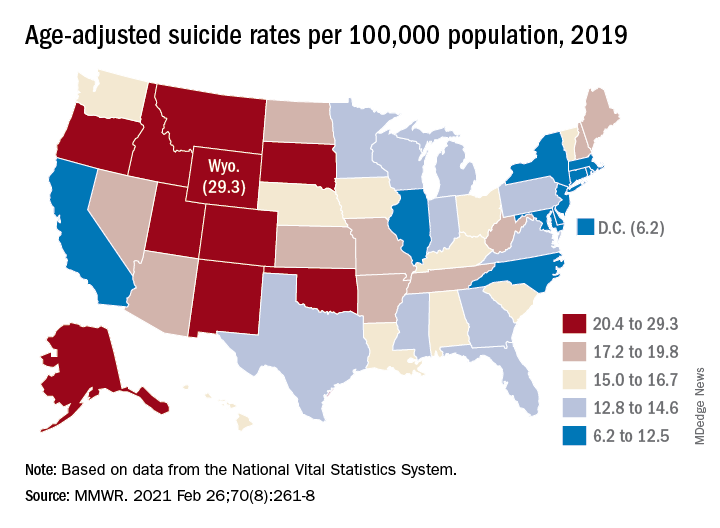

U.S. suicide rate in 2019 took first downturn in 14 years

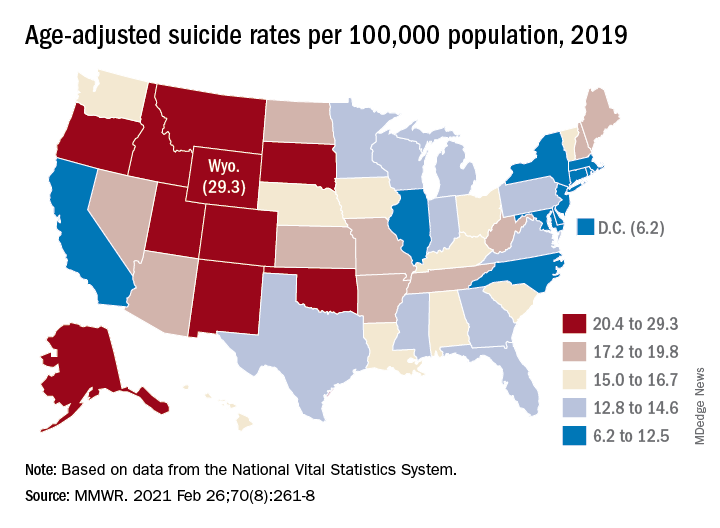

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

In 2019, the U.S. suicide rate dropped for the first time in 14 years, driven largely by a significant decline in firearm-related deaths, according to a new analysis of National Vital Statistics System data.

Since firearms are the “most common and most lethal” mechanism of suicide, the drop in deaths is “particularly encouraging,” Deborah M. Stone, ScD, MSW, MPH, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The national suicide rate decreased from 14.2 per 100,000 population in 2018 to 13.9 per 100,000 in 2019, a statistically significant drop of 2.1% that reversed a 20-year trend that saw the rate increase by 33% since 1999, they said.

The rate for firearm use, which is involved in half of all suicides, declined from 7.0 per 100,000 to 6.8, for a significant change of 2.9%, said Dr. Stone and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

The only other method with a drop in suicide rate from 2018 to 2019 was suffocation – the second most common mechanism of injury – but the relative change of 2.3% was not significant, they noted.

Significant declines also occurred in several subgroups: Whites; those aged 15-24, 55-64, and 65-74 years; and those living in counties classified as large fringe metropolitan or micropolitan (urban cluster of ≥ 10,000 but less than 50,000 population), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

the investigators wrote.

The states with significant increases were Hawaii (30.3%) and Nebraska (20.1%), while declines in the suicide rate were significant in five states – Idaho, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Virginia, Dr. Stone and associates reported. Altogether, the rate fell in 31 states, increased in 18, and did not change in 2.

The significance of those changes varied between males and females. Declines were significant for females in Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, and for males in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and West Virginia. Minnesota was the only state with a significant increase among females, with Hawaii and Wyoming posting increases for males, they said.

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the investigators pointed out, “prevention is more important than ever. Past research indicates that suicide rates remain stable or decline during infrastructure disruption (e.g., natural disasters), only to rise afterwards as the longer-term sequelae unfold in persons, families, and communities.”

FROM MMWR

Docs become dog groomers and warehouse workers after COVID-19 work loss

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the biggest conundrums of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the simultaneous panic-hiring of medical professionals in hot spots and significant downsizing of staff across the country. From huge hospital systems to private practices, the stoppage of breast reductions and knee replacements, not to mention the drops in motor vehicle accidents and bar fights, have quieted operating rooms and emergency departments and put doctors’ jobs on the chopping block. A widely cited survey suggests that 21% of doctors have had a work reduction due to COVID-19.

For many American doctors, this is their first extended period of unemployment. Unlike engineers or those with MBAs who might see their fortunes rise and fall with the whims of recessions and boom times, physicians are not exactly accustomed to being laid off. However, doctors were already smarting for years due to falling salaries and decreased autonomy, punctuated by endless clicks on electronic medical records software.

Stephanie Eschenbach Morgan, MD, a breast radiologist in North Carolina, trained for 10 years after college before earning a true physician’s salary.

“Being furloughed was awful. Initially, it was only going to be 2 weeks, and then it turned into 2 months with no pay,” she reflected.

Dr. Eschenbach Morgan and her surgeon husband, who lost a full quarter’s salary, had to ask for grace periods on their credit card and mortgage payments because they had paid a large tax bill right before the pandemic began. “We couldn’t get any stimulus help, so that added insult to injury,” she said.

With her time spent waiting in a holding pattern, Dr. Eschenbach Morgan homeschooled her two young children and started putting a home gym together. She went on a home organizing spree, started a garden, and, perhaps most impressively, caught up with 5 years of photo albums.

A bonus she noted: “I didn’t set an alarm for 2 months.”

Shella Farooki, MD, a radiologist in California, was also focused on homeschooling, itself a demanding job, and veered toward retirement. When one of her work contracts furloughed her (“at one point, I made $30K a month for [their business]”), she started saving money at home, teaching the kids, and applied for a Paycheck Protection Program loan. Her husband, a hospitalist, had had his shifts cut. Dr. Farooki tried a radiology artificial intelligence firm but backed out when she was asked to read 9,200 studies for them for $2,000 per month.

Now, she thinks about leaving medicine “every day.”

Some doctors are questioning whether they should be in medicine in the first place. Family medicine physician Jonathan Polak, MD, faced with his own pink slip, turned to pink T-shirts instead. His girlfriend manages an outlet of the teen fashion retailer Justice. Dr. Polak, who finished his residency just 2 years ago, didn’t hesitate to take a $10-an-hour gig as a stock doc, once even finding himself delivering a shelving unit from the shuttering store to a physician fleeing the city for rural New Hampshire to “escape.”

There’s no escape for him – yet. Saddled with “astronomical” student loans, he had considered grocery store work as well. Dr. Polak knows he can’t work part time or go into teaching long term, as he might like.

Even so, he’s doing everything he can to not be in patient care for the long haul – it’s just not what he thought it would be.

“The culture of medicine, bureaucracy, endless paperwork and charting, and threat of litigation sucks a lot of the joy out of it to the point that I don’t see myself doing it forever when imagining myself 5-10 years into it.”

Still, he recently took an 18-month hospital contract that will force him to move to Florida, but he’s also been turning himself into a veritable Renaissance man; composing music, training for an ultramarathon, studying the latest medical findings, roadtripping, and launching a podcast about dog grooming with a master groomer. “We found parallels between medicine and dog grooming,” he says, somewhat convincingly.

Also working the ruff life is Jen Tserng, MD, a former forensic pathologist who landed on news websites in recent years for becoming a professional dogwalker and housesitter without a permanent home. Dr. Tserng knows doctors were restless and unhappy before COVID-19, their thoughts wandering where the grass might be greener.

As her profile grew, she found her inbox gathering messages from disaffected medical minions: students with a fear of failing or staring down residency application season and employed doctors sick of the constant grind. As she recounted those de facto life coach conversations (“What do you really enjoy?” “Do you really like dogs?”) by phone from New York, she said matter-of-factly, “They don’t call because of COVID. They call because they hate their lives.”

Michelle Mudge-Riley, MD, a physician in Texas, has been seeing this shift for some time as well. She recently held a virtual version of her Physicians Helping Physicians conference, where doctors hear from their peers working successfully in fields like pharmaceuticals and real estate investing.

When COVID-19 hit, Dr. Mudge-Riley quickly pivoted to a virtual platform, where the MDs and DOs huddled in breakout rooms having honest chats about their fears and tentative hopes about their new careers.

“There has been increased interest in nonclinical exploration into full- and part-time careers, as well as side hustles, since COVID began,” she said. “Many physicians have had their hours or pay cut, and some have been laid off. Others are furloughed. Some just want out of an environment where they don’t feel safe.”

An ear, nose, and throat surgeon, Maansi Doshi, MD, from central California, didn’t feel safe – so she left. She had returned from India sick with a mystery virus right as the pandemic began (she said her COVID-19 tests were all negative) and was waiting to get well enough to go back to her private practice job. However, she said she clashed with Trump-supporting colleagues she feared might not be taking the pandemic seriously enough.

Finally getting over a relapse of her mystery virus, Dr. Doshi emailed her resignation in May. Her husband, family practice doctor Mark Mangiapane, MD, gave his job notice weeks later in solidarity because he worked in the same building. Together, they have embraced gardening, a Peloton splurge, and learning business skills to open private practices – solo primary care for him; ENT with a focus on her favorite surgery, rhinoplasty, for her.

Dr. Mangiapane had considered editing medical brochures and also tried to apply for a job as a county public health officer in rural California, but he received his own shock when he learned the county intended to open schools in the midst of the pandemic despite advisement to the contrary by the former health officer.

He retreated from job listings altogether after hearing his would-be peers were getting death threats – targeting their children.

Both doctors felt COVID-19 pushed them beyond their comfort zones. “If COVID hadn’t happened, I would be working. ... Be ‘owned.’ In a weird way, COVID made me more independent and take a risk with my career.”

Obstetrician Kwandaa Roberts, MD, certainly did; she took a budding interest in decorating dollhouses straight to Instagram and national news fame, and she is now a TV-show expert on “Sell This House.”

Like Dr. Doshi and Dr. Mangiapane, Dr. Polak wants to be more in control of his future – even if selling T-shirts at a mall means a certain loss of status along the way.

“Aside from my passion to learn and to have that connection with people, I went into medicine ... because of the job security I thought existed,” he said. “I would say that my getting furloughed has changed my view of the United States in a dramatic way. I do not feel as confident in the U.S. economy and general way of life as I did a year ago. And I am taking a number of steps to put myself in a more fluid, adaptable position in case another crisis like this occurs or if the current state of things worsens.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mepolizumab reduced exacerbations in patients with asthma and atopy, depression comorbidities

, according to research from the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“Mepolizumab has clearly been shown to improve severe asthma control in many clinical trials, but atopy, obesity, and depression/anxiety affect patients with asthma at an increased rate,” Thomas B. Casale, MD, former AAAAI president and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said in a presentation at the meeting. “Yet, few studies have examined whether asthma therapy with these comorbidities works.”

Dr. Casale and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of patients in the United States from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database between November 2014 and December 2018 who had atopy, obesity, or depression/anxiety in addition to asthma and were receiving mepolizumab. Atopy in the study was defined as allergic rhinitis, anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and food allergies. Patients were at least age 12 years, had at least one diagnosis for asthma, at least one diagnosis code for atopic disease, obesity, or depression/anxiety at baseline, and at least two administrations of mepolizumab within 180 days.

The researchers examined the number of exacerbations, oral corticosteroid (OCS) claims, and OCS bursts per year at 12-month follow-up, compared with baseline. They identified exacerbations by examining patients who had an emergency department or outpatient claim related to their asthma, and a claim for systemic corticosteroids made in the 4 days prior to or 5 days after a visit, or if their inpatient hospital admission contained a primary asthma diagnosis. Dr. Casale and colleagues measured OCS bursts as a pharmacy claim of at least 20 mg of prednisone per day for between 3 and 28 days plus a claim for an emergency department visit related to asthma in the 7 days prior or 6 days after the claim.

At baseline, patients across all groups were mean age 50.5-52.4 years with a Charleson Comorbidity Index score between 1.1 and 1.4, a majority were women (59.0%-72.0%) and nearly all were commercially insured (88.0%-90.0%). Patients who used biologics at baseline and/or used a biologic that wasn’t mepolizumab during the follow-up period were excluded.

Medication claims in the groups included inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (36.8%-48.6%), ICS/long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) (60.2%-63.0%), LABA/ long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (1.2%-3.5%), ICS/LABA/LAMA (21.2%-25.1%), short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) (83.2%-87.7%), LAMA alone (33.5%-42.1%), or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA).

In the non–mutually exclusive group of patients with atopy (468 patients), 28.0% had comorbid obesity and 26.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. For patients with obesity categorized in a non–mutually exclusive subgroup (171 patients), 79.0% had comorbid atopy and 32.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. Among patients with non–mutually exclusive depression/anxiety (173 patients), 70.0% had comorbid atopy, while 32.0% had comorbid obesity.

The results showed the mean number of overall exacerbations decreased by 48% at 12 months in the atopic group (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), 52% in the group with obesity (2.5 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and 38% in the depression/anxiety group (2.4 vs. 1.5; P < .001). The mean number of exacerbations leading to hospitalizations decreased by 64% in the atopic group (0.11 vs. 0.04; P < .001), 65% in the group with obesity (0.20 vs. 0.07; P < .001), and 68% in the group with depression/anxiety (0.22 vs. 0.07; P < .001).

The researchers also found the mean number of OCS claims and OCS bursts also significantly decreased over the 12-month follow-up period. Mean OCS claims decreased by 33% for patients in the atopic group (5.5 vs. 3.7; P < .001), by 38% in the group with obesity (6.1 vs. 3.8; P < .001), and by 31% in the group with depression/anxiety (6.2 vs. 4.3; P < .001).

The mean number of OCS bursts also significantly decreased by 40% in the atopic group (2.0 vs. 2.1; P < .001), 48% in the group with obesity (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and by 37% in the group with depression/anxiety (1.9 vs. 1.2; P < .001). In total, 69% of patients with comorbid atopy, 70.8% of patients with comorbid obesity, and 68.2% of patients with comorbid depression/anxiety experienced a mean decrease in their OCS dose over 12 months.

“These data demonstrate that patients with asthma and atopy, obesity, or depression and anxiety have significantly fewer exacerbations and reduced OCS use in a real-world setting with treatment of mepolizumab,” Dr. Casale said. “Thus, holistic patient care for severe asthma is critical, and mepolizumab provides tangible clinical benefit despite the complexities of medical comorbidities.”

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and the company also funded graphic design support of the poster. Dr. Casale reports he has received research funds from GlaxoSmithKline. Four authors report being current or former GlaxoSmithKline employees; three authors report holding stock and/or shares of GlaxoSmithKline. Three authors are IBM Watson Health employees, a company GlaxoSmithKline has provided research funding.

, according to research from the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“Mepolizumab has clearly been shown to improve severe asthma control in many clinical trials, but atopy, obesity, and depression/anxiety affect patients with asthma at an increased rate,” Thomas B. Casale, MD, former AAAAI president and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said in a presentation at the meeting. “Yet, few studies have examined whether asthma therapy with these comorbidities works.”

Dr. Casale and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of patients in the United States from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database between November 2014 and December 2018 who had atopy, obesity, or depression/anxiety in addition to asthma and were receiving mepolizumab. Atopy in the study was defined as allergic rhinitis, anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and food allergies. Patients were at least age 12 years, had at least one diagnosis for asthma, at least one diagnosis code for atopic disease, obesity, or depression/anxiety at baseline, and at least two administrations of mepolizumab within 180 days.

The researchers examined the number of exacerbations, oral corticosteroid (OCS) claims, and OCS bursts per year at 12-month follow-up, compared with baseline. They identified exacerbations by examining patients who had an emergency department or outpatient claim related to their asthma, and a claim for systemic corticosteroids made in the 4 days prior to or 5 days after a visit, or if their inpatient hospital admission contained a primary asthma diagnosis. Dr. Casale and colleagues measured OCS bursts as a pharmacy claim of at least 20 mg of prednisone per day for between 3 and 28 days plus a claim for an emergency department visit related to asthma in the 7 days prior or 6 days after the claim.

At baseline, patients across all groups were mean age 50.5-52.4 years with a Charleson Comorbidity Index score between 1.1 and 1.4, a majority were women (59.0%-72.0%) and nearly all were commercially insured (88.0%-90.0%). Patients who used biologics at baseline and/or used a biologic that wasn’t mepolizumab during the follow-up period were excluded.

Medication claims in the groups included inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (36.8%-48.6%), ICS/long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) (60.2%-63.0%), LABA/ long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (1.2%-3.5%), ICS/LABA/LAMA (21.2%-25.1%), short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) (83.2%-87.7%), LAMA alone (33.5%-42.1%), or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA).

In the non–mutually exclusive group of patients with atopy (468 patients), 28.0% had comorbid obesity and 26.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. For patients with obesity categorized in a non–mutually exclusive subgroup (171 patients), 79.0% had comorbid atopy and 32.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. Among patients with non–mutually exclusive depression/anxiety (173 patients), 70.0% had comorbid atopy, while 32.0% had comorbid obesity.

The results showed the mean number of overall exacerbations decreased by 48% at 12 months in the atopic group (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), 52% in the group with obesity (2.5 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and 38% in the depression/anxiety group (2.4 vs. 1.5; P < .001). The mean number of exacerbations leading to hospitalizations decreased by 64% in the atopic group (0.11 vs. 0.04; P < .001), 65% in the group with obesity (0.20 vs. 0.07; P < .001), and 68% in the group with depression/anxiety (0.22 vs. 0.07; P < .001).

The researchers also found the mean number of OCS claims and OCS bursts also significantly decreased over the 12-month follow-up period. Mean OCS claims decreased by 33% for patients in the atopic group (5.5 vs. 3.7; P < .001), by 38% in the group with obesity (6.1 vs. 3.8; P < .001), and by 31% in the group with depression/anxiety (6.2 vs. 4.3; P < .001).

The mean number of OCS bursts also significantly decreased by 40% in the atopic group (2.0 vs. 2.1; P < .001), 48% in the group with obesity (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and by 37% in the group with depression/anxiety (1.9 vs. 1.2; P < .001). In total, 69% of patients with comorbid atopy, 70.8% of patients with comorbid obesity, and 68.2% of patients with comorbid depression/anxiety experienced a mean decrease in their OCS dose over 12 months.

“These data demonstrate that patients with asthma and atopy, obesity, or depression and anxiety have significantly fewer exacerbations and reduced OCS use in a real-world setting with treatment of mepolizumab,” Dr. Casale said. “Thus, holistic patient care for severe asthma is critical, and mepolizumab provides tangible clinical benefit despite the complexities of medical comorbidities.”

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and the company also funded graphic design support of the poster. Dr. Casale reports he has received research funds from GlaxoSmithKline. Four authors report being current or former GlaxoSmithKline employees; three authors report holding stock and/or shares of GlaxoSmithKline. Three authors are IBM Watson Health employees, a company GlaxoSmithKline has provided research funding.

, according to research from the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

“Mepolizumab has clearly been shown to improve severe asthma control in many clinical trials, but atopy, obesity, and depression/anxiety affect patients with asthma at an increased rate,” Thomas B. Casale, MD, former AAAAI president and professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of South Florida in Tampa, said in a presentation at the meeting. “Yet, few studies have examined whether asthma therapy with these comorbidities works.”

Dr. Casale and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of patients in the United States from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database between November 2014 and December 2018 who had atopy, obesity, or depression/anxiety in addition to asthma and were receiving mepolizumab. Atopy in the study was defined as allergic rhinitis, anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, conjunctivitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and food allergies. Patients were at least age 12 years, had at least one diagnosis for asthma, at least one diagnosis code for atopic disease, obesity, or depression/anxiety at baseline, and at least two administrations of mepolizumab within 180 days.

The researchers examined the number of exacerbations, oral corticosteroid (OCS) claims, and OCS bursts per year at 12-month follow-up, compared with baseline. They identified exacerbations by examining patients who had an emergency department or outpatient claim related to their asthma, and a claim for systemic corticosteroids made in the 4 days prior to or 5 days after a visit, or if their inpatient hospital admission contained a primary asthma diagnosis. Dr. Casale and colleagues measured OCS bursts as a pharmacy claim of at least 20 mg of prednisone per day for between 3 and 28 days plus a claim for an emergency department visit related to asthma in the 7 days prior or 6 days after the claim.

At baseline, patients across all groups were mean age 50.5-52.4 years with a Charleson Comorbidity Index score between 1.1 and 1.4, a majority were women (59.0%-72.0%) and nearly all were commercially insured (88.0%-90.0%). Patients who used biologics at baseline and/or used a biologic that wasn’t mepolizumab during the follow-up period were excluded.

Medication claims in the groups included inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (36.8%-48.6%), ICS/long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) (60.2%-63.0%), LABA/ long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (1.2%-3.5%), ICS/LABA/LAMA (21.2%-25.1%), short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) (83.2%-87.7%), LAMA alone (33.5%-42.1%), or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA).

In the non–mutually exclusive group of patients with atopy (468 patients), 28.0% had comorbid obesity and 26.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. For patients with obesity categorized in a non–mutually exclusive subgroup (171 patients), 79.0% had comorbid atopy and 32.0% had comorbid depression/anxiety. Among patients with non–mutually exclusive depression/anxiety (173 patients), 70.0% had comorbid atopy, while 32.0% had comorbid obesity.

The results showed the mean number of overall exacerbations decreased by 48% at 12 months in the atopic group (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), 52% in the group with obesity (2.5 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and 38% in the depression/anxiety group (2.4 vs. 1.5; P < .001). The mean number of exacerbations leading to hospitalizations decreased by 64% in the atopic group (0.11 vs. 0.04; P < .001), 65% in the group with obesity (0.20 vs. 0.07; P < .001), and 68% in the group with depression/anxiety (0.22 vs. 0.07; P < .001).

The researchers also found the mean number of OCS claims and OCS bursts also significantly decreased over the 12-month follow-up period. Mean OCS claims decreased by 33% for patients in the atopic group (5.5 vs. 3.7; P < .001), by 38% in the group with obesity (6.1 vs. 3.8; P < .001), and by 31% in the group with depression/anxiety (6.2 vs. 4.3; P < .001).

The mean number of OCS bursts also significantly decreased by 40% in the atopic group (2.0 vs. 2.1; P < .001), 48% in the group with obesity (2.3 vs. 1.2; P < .001), and by 37% in the group with depression/anxiety (1.9 vs. 1.2; P < .001). In total, 69% of patients with comorbid atopy, 70.8% of patients with comorbid obesity, and 68.2% of patients with comorbid depression/anxiety experienced a mean decrease in their OCS dose over 12 months.

“These data demonstrate that patients with asthma and atopy, obesity, or depression and anxiety have significantly fewer exacerbations and reduced OCS use in a real-world setting with treatment of mepolizumab,” Dr. Casale said. “Thus, holistic patient care for severe asthma is critical, and mepolizumab provides tangible clinical benefit despite the complexities of medical comorbidities.”

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline, and the company also funded graphic design support of the poster. Dr. Casale reports he has received research funds from GlaxoSmithKline. Four authors report being current or former GlaxoSmithKline employees; three authors report holding stock and/or shares of GlaxoSmithKline. Three authors are IBM Watson Health employees, a company GlaxoSmithKline has provided research funding.

FROM AAAAI 2021

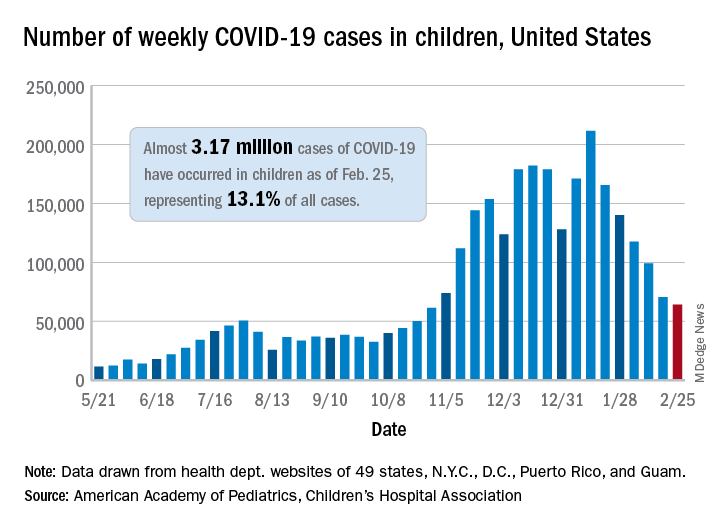

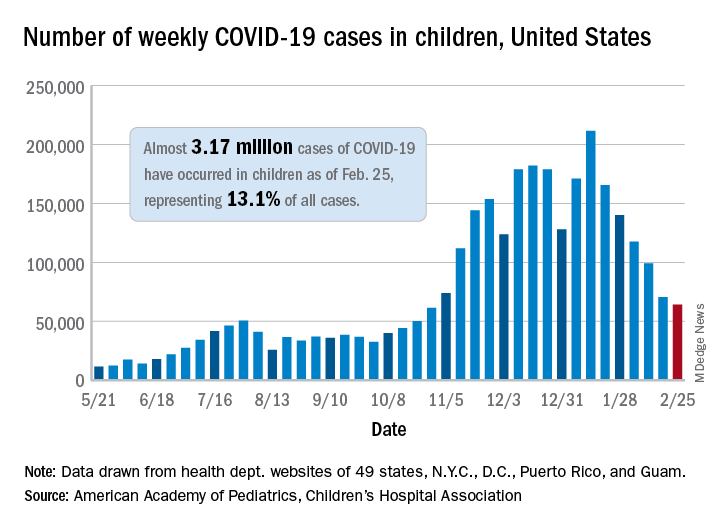

Decline in children’s COVID-19 cases slows

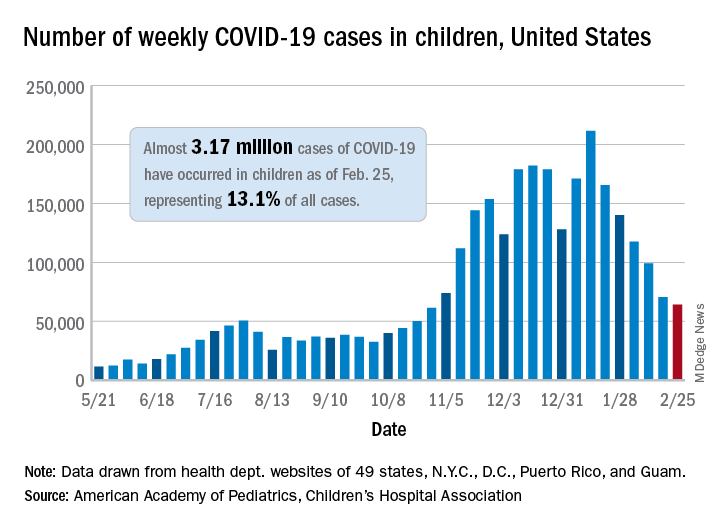

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children declined for the sixth consecutive week, but the drop was the smallest yet, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That drop of almost 6,400 cases, or 9.0%, falls short of the declines recorded in any the previous 5 weeks, which ranged from 18,000 to 46,000 cases and 15.3% to 28.7%, based on data from the heath departments of 49 states (excluding New York), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 is up to almost 3.17 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all age groups. That cumulative proportion was unchanged from the previous week, which has occurred only three other times over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Despite the 6-week decline in new cases, however, the cumulative rate continued to climb, rising from 4,124 cases per 100,000 children to 4,209 for the week of Feb. 19-25. The states, not surprisingly, fall on both sides of that national tally. The lowest rates can be found in Hawaii (1,040 per 100,000 children), Vermont (2,111 per 100,000), and Maine (2,394), while the highest rates were recorded in North Dakota (8,580), Tennessee (7,851), and Rhode Island (7,223), the AAP and CHA said.

The number of new child deaths, nine, stayed in single digits for a second consecutive week, although it was up from six deaths reported a week earlier. Total COVID-19–related deaths in children now number 256, which represents just 0.06% of coronavirus deaths for all ages among the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) reporting such data.

Among those jurisdictions, Texas (40), Arizona (27), and New York City (23) have reported the most deaths in children, while nine states and the District of Columbia have reported no deaths yet, the AAP and CHA noted.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children declined for the sixth consecutive week, but the drop was the smallest yet, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That drop of almost 6,400 cases, or 9.0%, falls short of the declines recorded in any the previous 5 weeks, which ranged from 18,000 to 46,000 cases and 15.3% to 28.7%, based on data from the heath departments of 49 states (excluding New York), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 is up to almost 3.17 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all age groups. That cumulative proportion was unchanged from the previous week, which has occurred only three other times over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Despite the 6-week decline in new cases, however, the cumulative rate continued to climb, rising from 4,124 cases per 100,000 children to 4,209 for the week of Feb. 19-25. The states, not surprisingly, fall on both sides of that national tally. The lowest rates can be found in Hawaii (1,040 per 100,000 children), Vermont (2,111 per 100,000), and Maine (2,394), while the highest rates were recorded in North Dakota (8,580), Tennessee (7,851), and Rhode Island (7,223), the AAP and CHA said.

The number of new child deaths, nine, stayed in single digits for a second consecutive week, although it was up from six deaths reported a week earlier. Total COVID-19–related deaths in children now number 256, which represents just 0.06% of coronavirus deaths for all ages among the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) reporting such data.

Among those jurisdictions, Texas (40), Arizona (27), and New York City (23) have reported the most deaths in children, while nine states and the District of Columbia have reported no deaths yet, the AAP and CHA noted.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in children declined for the sixth consecutive week, but the drop was the smallest yet, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That drop of almost 6,400 cases, or 9.0%, falls short of the declines recorded in any the previous 5 weeks, which ranged from 18,000 to 46,000 cases and 15.3% to 28.7%, based on data from the heath departments of 49 states (excluding New York), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 is up to almost 3.17 million, which represents 13.1% of cases among all age groups. That cumulative proportion was unchanged from the previous week, which has occurred only three other times over the course of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

Despite the 6-week decline in new cases, however, the cumulative rate continued to climb, rising from 4,124 cases per 100,000 children to 4,209 for the week of Feb. 19-25. The states, not surprisingly, fall on both sides of that national tally. The lowest rates can be found in Hawaii (1,040 per 100,000 children), Vermont (2,111 per 100,000), and Maine (2,394), while the highest rates were recorded in North Dakota (8,580), Tennessee (7,851), and Rhode Island (7,223), the AAP and CHA said.

The number of new child deaths, nine, stayed in single digits for a second consecutive week, although it was up from six deaths reported a week earlier. Total COVID-19–related deaths in children now number 256, which represents just 0.06% of coronavirus deaths for all ages among the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) reporting such data.

Among those jurisdictions, Texas (40), Arizona (27), and New York City (23) have reported the most deaths in children, while nine states and the District of Columbia have reported no deaths yet, the AAP and CHA noted.

Thirteen percent of patients with type 2 diabetes have major ECG abnormalities

Major ECG abnormalities were found in 13% of more than 8,000 unselected patients with type 2 diabetes, including a 9% prevalence in the subgroup of these patients without identified cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a community-based Dutch cohort. Minor ECG abnormalities were even more prevalent.

These prevalence rates were consistent with prior findings from patients with type 2 diabetes, but the current report is notable because “it provides the most thorough description of the prevalence of ECG abnormalities in people with type 2 diabetes,” and used an “unselected and large population with comprehensive measurements,” including many without a history of CVD, said Peter P. Harms, MSc, and associates noted in a recent report in the Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications.

The analysis also identified several parameters that significantly linked with the presence of a major ECG abnormality including hypertension, male sex, older age, and higher levels of hemoglobin A1c.

“Resting ECG abnormalities might be a useful tool for CVD screening in people with type 2 diabetes,” concluded Mr. Harms, a researcher at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, and coauthors.

Findings “not unexpected”

Patients with diabetes have a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities “because of their higher likelihood of having hypertension and other CVD risk factors,” as well as potentially having subclinical CVD, said Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, so these findings are “not unexpected. The more risk factors a patient has for structural heart disease, atrial fibrillation (AFib), or stroke from AFib, the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

But he cautioned against seeing these findings as a rationale to routinely run a resting ECG examination on every adult with diabetes.

“Patients with diabetes are very heterogeneous,” which makes it “difficult to come up with a ‘one size fits all’ recommendation” for ECG screening of patients with diabetes, he said.