User login

A 17-year-old male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a year-long rash

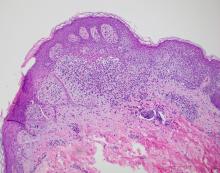

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A 17-year-old healthy male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on the skin which has been present on and off for a year. During the initial presentation, the lesions were clustered on the back, were slightly itchy, and resolved after 3 months. Several new lesions have developed on the neck, torso, and extremities, leaving hypopigmented marks on the skin. He has previously been treated with topical antifungal creams, oral fluconazole, and triamcinolone ointment without resolution of the lesions.

He is not involved in any contact sports, he has not traveled outside the country, and is not taking any other medications. He is not sexually active. He also has a diagnosis of mild acne that he is currently treating with over-the-counter medications.

On physical exam he had several annular plaques with central atrophic centers and no scale. He also had some hypo- and hyperpigmented macules at the sites of prior skin lesions

Does paying people to lose weight work?

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians and your staffs: Be nice

Several years ago I visited my primary care provider in her new office. She had just left the practice where we had been coworkers for over a decade. I was “roomed” by Louise (not her real name) whom I had never met before. I assumed she had come with the new waiting room furniture. She took my vital signs, asked a few boilerplate questions, and told me that my PCP would be in shortly.

After our initial ping-pong match of how-are-things-going I mentioned to my old friend/PCP that I thought Louise needed to work on her person-to-person skills. She thanked me and said there were so many challenges in the new practice setting she hadn’t had a chance to work on staff training.

When I returned 6 months later Louise was a different person. She appeared and sounded interested in who I was and left me in the room to wait feeling glad I had spoken up. I wasn’t surprised at the change, knowing my former coworker’s past history. I was confident that in time she would coach her new staff and continue to reinforce her message by setting an example by being a caring and concerned physician.

The old Louise certainly wasn’t a rude or unpleasant person but good customer service just didn’t come naturally to her. She thought she was doing a good job, at least as far as she understood what her job was supposed to be. On the whole spectrum of professional misbehavior she would barely warrant a pixel of color. Unfortunately, we are seeing and suffering through a surge of rude behavior and incivility not just in the medical community but across all segments of our society.

It is particularly troubling in health care, which has an organizational nonsystem that was initially paternalistic and male dominated but continues to be hierarchical even as gender stereotypes are becoming less rigid. Rudeness within a team, whether it is a medical office or a factory assembly line, can create a toxic work environment that can affect the quality of the product. In this case the end product is the health and wellness of our patients. While incivility within a team can occasionally be hidden from the patients, eventually it will surface and take its toll on the customer service component of the practice.

One wonders why so many of us are behaving rudely. Is it examples we see in the media, is it our political leaders, or is the pandemic a contributor? Has democracy run its course? Are we victims of our departure from organized religion? Do we need to reorganize our medical training to be less hierarchical? I don’t think there is any single cause nor do I believe we need to restructure our medical training system to remedy the situation. We will always need to transfer information and skills from people who have them to people who need to learn them. If there is a low-hanging fruit in the customer service orchard it is one person at a time deciding to behave in a civil manner toward fellow citizens.

While a colorful crop of political signs arrived in the run-up to the November election, recently, here on the midcoast of Maine, simple white-on-black signs have appeared saying “BE NICE.”

The good news is that being nice can be contagious. Simply think of that golden rule. Treat your patients/customers/coworkers as you would like to be treated yourself.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Several years ago I visited my primary care provider in her new office. She had just left the practice where we had been coworkers for over a decade. I was “roomed” by Louise (not her real name) whom I had never met before. I assumed she had come with the new waiting room furniture. She took my vital signs, asked a few boilerplate questions, and told me that my PCP would be in shortly.

After our initial ping-pong match of how-are-things-going I mentioned to my old friend/PCP that I thought Louise needed to work on her person-to-person skills. She thanked me and said there were so many challenges in the new practice setting she hadn’t had a chance to work on staff training.

When I returned 6 months later Louise was a different person. She appeared and sounded interested in who I was and left me in the room to wait feeling glad I had spoken up. I wasn’t surprised at the change, knowing my former coworker’s past history. I was confident that in time she would coach her new staff and continue to reinforce her message by setting an example by being a caring and concerned physician.

The old Louise certainly wasn’t a rude or unpleasant person but good customer service just didn’t come naturally to her. She thought she was doing a good job, at least as far as she understood what her job was supposed to be. On the whole spectrum of professional misbehavior she would barely warrant a pixel of color. Unfortunately, we are seeing and suffering through a surge of rude behavior and incivility not just in the medical community but across all segments of our society.

It is particularly troubling in health care, which has an organizational nonsystem that was initially paternalistic and male dominated but continues to be hierarchical even as gender stereotypes are becoming less rigid. Rudeness within a team, whether it is a medical office or a factory assembly line, can create a toxic work environment that can affect the quality of the product. In this case the end product is the health and wellness of our patients. While incivility within a team can occasionally be hidden from the patients, eventually it will surface and take its toll on the customer service component of the practice.

One wonders why so many of us are behaving rudely. Is it examples we see in the media, is it our political leaders, or is the pandemic a contributor? Has democracy run its course? Are we victims of our departure from organized religion? Do we need to reorganize our medical training to be less hierarchical? I don’t think there is any single cause nor do I believe we need to restructure our medical training system to remedy the situation. We will always need to transfer information and skills from people who have them to people who need to learn them. If there is a low-hanging fruit in the customer service orchard it is one person at a time deciding to behave in a civil manner toward fellow citizens.

While a colorful crop of political signs arrived in the run-up to the November election, recently, here on the midcoast of Maine, simple white-on-black signs have appeared saying “BE NICE.”

The good news is that being nice can be contagious. Simply think of that golden rule. Treat your patients/customers/coworkers as you would like to be treated yourself.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Several years ago I visited my primary care provider in her new office. She had just left the practice where we had been coworkers for over a decade. I was “roomed” by Louise (not her real name) whom I had never met before. I assumed she had come with the new waiting room furniture. She took my vital signs, asked a few boilerplate questions, and told me that my PCP would be in shortly.

After our initial ping-pong match of how-are-things-going I mentioned to my old friend/PCP that I thought Louise needed to work on her person-to-person skills. She thanked me and said there were so many challenges in the new practice setting she hadn’t had a chance to work on staff training.

When I returned 6 months later Louise was a different person. She appeared and sounded interested in who I was and left me in the room to wait feeling glad I had spoken up. I wasn’t surprised at the change, knowing my former coworker’s past history. I was confident that in time she would coach her new staff and continue to reinforce her message by setting an example by being a caring and concerned physician.

The old Louise certainly wasn’t a rude or unpleasant person but good customer service just didn’t come naturally to her. She thought she was doing a good job, at least as far as she understood what her job was supposed to be. On the whole spectrum of professional misbehavior she would barely warrant a pixel of color. Unfortunately, we are seeing and suffering through a surge of rude behavior and incivility not just in the medical community but across all segments of our society.

It is particularly troubling in health care, which has an organizational nonsystem that was initially paternalistic and male dominated but continues to be hierarchical even as gender stereotypes are becoming less rigid. Rudeness within a team, whether it is a medical office or a factory assembly line, can create a toxic work environment that can affect the quality of the product. In this case the end product is the health and wellness of our patients. While incivility within a team can occasionally be hidden from the patients, eventually it will surface and take its toll on the customer service component of the practice.

One wonders why so many of us are behaving rudely. Is it examples we see in the media, is it our political leaders, or is the pandemic a contributor? Has democracy run its course? Are we victims of our departure from organized religion? Do we need to reorganize our medical training to be less hierarchical? I don’t think there is any single cause nor do I believe we need to restructure our medical training system to remedy the situation. We will always need to transfer information and skills from people who have them to people who need to learn them. If there is a low-hanging fruit in the customer service orchard it is one person at a time deciding to behave in a civil manner toward fellow citizens.

While a colorful crop of political signs arrived in the run-up to the November election, recently, here on the midcoast of Maine, simple white-on-black signs have appeared saying “BE NICE.”

The good news is that being nice can be contagious. Simply think of that golden rule. Treat your patients/customers/coworkers as you would like to be treated yourself.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Taking our own advice

Like many Americans, I’m overweight. Working 70-80 hours a week doesn’t leave much time for exercise. I try to do what I can, such as using stairs instead of the elevator, but in a two-story office building that doesn’t get you very far. And when I get home there are still tests to read, dictations to do, finances to catch up on ... which leaves little time for anything else other than eating and sleeping.

Eating better? Easier said than done. When I was single, back in residency, that was easy. I only had one person to shop for and feed, but in a family you need to find something that will keep everyone happy, and with three teenagers that ain’t easy. Everyone wants this, that, or the other, and none of it seems to be particularly good for you.

In the modern era convenience generally beats pretty much everything else. Our lives are hurried. At some point it’s just easier to pick something up or order out than to go to the effort of preparing your own meals. Of course, it’s possible to get something healthy for takeout, but the unhealthy menu items sound so much better, and by that time of day I’m tired, hungry, and stressed, and the will power I had in the morning is pretty much gone.

It’s kind of a medical paradox. Those of us taking care of others often don’t do the same for ourselves. Part of this, as noted in a recent Medscape article, is that we live on schedules that are unrelated to the typical 9-to-5 jobs that most other professionals have, not to mention a very different set of stressors.

At least I haven’t started smoking.

As the article points out, I’m not alone. In fact, it’s reassuring to know other physicians are dealing with the same situation. We often assume we’re alone in our struggles, when the actual truth is the opposite.

All of our medical training doesn’t mean we’re not human. It would be nice if the job made us better able to practice what we preach, but human nature is older than medicine, and we’re susceptible to the same faults and temptations as those of our patients.

And always will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like many Americans, I’m overweight. Working 70-80 hours a week doesn’t leave much time for exercise. I try to do what I can, such as using stairs instead of the elevator, but in a two-story office building that doesn’t get you very far. And when I get home there are still tests to read, dictations to do, finances to catch up on ... which leaves little time for anything else other than eating and sleeping.

Eating better? Easier said than done. When I was single, back in residency, that was easy. I only had one person to shop for and feed, but in a family you need to find something that will keep everyone happy, and with three teenagers that ain’t easy. Everyone wants this, that, or the other, and none of it seems to be particularly good for you.

In the modern era convenience generally beats pretty much everything else. Our lives are hurried. At some point it’s just easier to pick something up or order out than to go to the effort of preparing your own meals. Of course, it’s possible to get something healthy for takeout, but the unhealthy menu items sound so much better, and by that time of day I’m tired, hungry, and stressed, and the will power I had in the morning is pretty much gone.

It’s kind of a medical paradox. Those of us taking care of others often don’t do the same for ourselves. Part of this, as noted in a recent Medscape article, is that we live on schedules that are unrelated to the typical 9-to-5 jobs that most other professionals have, not to mention a very different set of stressors.

At least I haven’t started smoking.

As the article points out, I’m not alone. In fact, it’s reassuring to know other physicians are dealing with the same situation. We often assume we’re alone in our struggles, when the actual truth is the opposite.

All of our medical training doesn’t mean we’re not human. It would be nice if the job made us better able to practice what we preach, but human nature is older than medicine, and we’re susceptible to the same faults and temptations as those of our patients.

And always will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like many Americans, I’m overweight. Working 70-80 hours a week doesn’t leave much time for exercise. I try to do what I can, such as using stairs instead of the elevator, but in a two-story office building that doesn’t get you very far. And when I get home there are still tests to read, dictations to do, finances to catch up on ... which leaves little time for anything else other than eating and sleeping.

Eating better? Easier said than done. When I was single, back in residency, that was easy. I only had one person to shop for and feed, but in a family you need to find something that will keep everyone happy, and with three teenagers that ain’t easy. Everyone wants this, that, or the other, and none of it seems to be particularly good for you.

In the modern era convenience generally beats pretty much everything else. Our lives are hurried. At some point it’s just easier to pick something up or order out than to go to the effort of preparing your own meals. Of course, it’s possible to get something healthy for takeout, but the unhealthy menu items sound so much better, and by that time of day I’m tired, hungry, and stressed, and the will power I had in the morning is pretty much gone.

It’s kind of a medical paradox. Those of us taking care of others often don’t do the same for ourselves. Part of this, as noted in a recent Medscape article, is that we live on schedules that are unrelated to the typical 9-to-5 jobs that most other professionals have, not to mention a very different set of stressors.

At least I haven’t started smoking.

As the article points out, I’m not alone. In fact, it’s reassuring to know other physicians are dealing with the same situation. We often assume we’re alone in our struggles, when the actual truth is the opposite.

All of our medical training doesn’t mean we’re not human. It would be nice if the job made us better able to practice what we preach, but human nature is older than medicine, and we’re susceptible to the same faults and temptations as those of our patients.

And always will be.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Let people take illegal drugs under medical supervision?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why doctors are losing trust in patients; what should be done?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No, you can’t see a different doctor: We need zero tolerance of patient bias

It was 1970. I was in my second year of medical school. I can remember the hurt and embarrassment as if it were yesterday.

Coming from the Deep South, I was very familiar with racial bias, but I did not expect it at that level and in that environment. From that point on, I was anxious at each patient encounter, concerned that this might happen again. And it did several times during my residency and fellowship.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines workplace violence as “any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults.”

There is considerable media focus on incidents of physical violence against health care workers, but when patients, their families, or visitors openly display bias and request a different doctor, nurse, or technician for nonmedical reasons, the impact is profound. This is extremely hurtful to a professional who has worked long and hard to acquire skills and expertise. And, while speech may not constitute violence in the strictest sense of the word, there is growing evidence that it can be physically harmful through its effect on the nervous system, even if no physical contact is involved.

Incidents of bias occur regularly and are clearly on the rise. In most cases the request for a different health care worker is granted to honor the rights of the patient. The healthcare worker is left alone and emotionally wounded; the healthcare institutions are complicit.

This bias is mostly racial but can also be based on religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, body size, accent, or gender.

An entire issue of the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics was devoted to this topic. From recognizing that there are limits to what clinicians should be expected to tolerate when patients’ preferences express unjust bias, the issue also explored where those limits should be placed, why, and who is obliged to enforce them.

The newly adopted Mass General Patient Code of Conduct is evidence that health care systems are beginning to recognize this problem and that such behavior will not be tolerated.

But having a zero-tolerance policy is not enough. We must have procedures in place to discourage and mitigate the impact of patient bias.

A clear definition of what constitutes a bias incident is essential. All team members must be made aware of the procedures for reporting such incidents and the chain of command for escalation. Reporting should be encouraged, and resources must be made available to impacted team members. Surveillance, monitoring, and review are also essential as is clarification on when patient preferences should be honored.

The Mayo Clinic 5 Step Plan is an excellent example of a protocol to deal with patient bias against health care workers and is based on a thoughtful analysis of what constitutes an unreasonable request for a different clinician. I’m pleased to report that my health care system (Inova Health) is developing a similar protocol.

The health care setting should be a bias-free zone for both patients and health care workers. I have been a strong advocate of patients’ rights and worked hard to guard against bias and eliminate disparities in care, but health care workers have rights as well.

We should expect to be treated with respect.

The views expressed by the author are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the Inova Health System. Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was 1970. I was in my second year of medical school. I can remember the hurt and embarrassment as if it were yesterday.

Coming from the Deep South, I was very familiar with racial bias, but I did not expect it at that level and in that environment. From that point on, I was anxious at each patient encounter, concerned that this might happen again. And it did several times during my residency and fellowship.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines workplace violence as “any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults.”

There is considerable media focus on incidents of physical violence against health care workers, but when patients, their families, or visitors openly display bias and request a different doctor, nurse, or technician for nonmedical reasons, the impact is profound. This is extremely hurtful to a professional who has worked long and hard to acquire skills and expertise. And, while speech may not constitute violence in the strictest sense of the word, there is growing evidence that it can be physically harmful through its effect on the nervous system, even if no physical contact is involved.

Incidents of bias occur regularly and are clearly on the rise. In most cases the request for a different health care worker is granted to honor the rights of the patient. The healthcare worker is left alone and emotionally wounded; the healthcare institutions are complicit.

This bias is mostly racial but can also be based on religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, body size, accent, or gender.

An entire issue of the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics was devoted to this topic. From recognizing that there are limits to what clinicians should be expected to tolerate when patients’ preferences express unjust bias, the issue also explored where those limits should be placed, why, and who is obliged to enforce them.

The newly adopted Mass General Patient Code of Conduct is evidence that health care systems are beginning to recognize this problem and that such behavior will not be tolerated.

But having a zero-tolerance policy is not enough. We must have procedures in place to discourage and mitigate the impact of patient bias.

A clear definition of what constitutes a bias incident is essential. All team members must be made aware of the procedures for reporting such incidents and the chain of command for escalation. Reporting should be encouraged, and resources must be made available to impacted team members. Surveillance, monitoring, and review are also essential as is clarification on when patient preferences should be honored.

The Mayo Clinic 5 Step Plan is an excellent example of a protocol to deal with patient bias against health care workers and is based on a thoughtful analysis of what constitutes an unreasonable request for a different clinician. I’m pleased to report that my health care system (Inova Health) is developing a similar protocol.

The health care setting should be a bias-free zone for both patients and health care workers. I have been a strong advocate of patients’ rights and worked hard to guard against bias and eliminate disparities in care, but health care workers have rights as well.

We should expect to be treated with respect.

The views expressed by the author are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the Inova Health System. Dr. Francis is a cardiologist at Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, McLean, Va. He disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was 1970. I was in my second year of medical school. I can remember the hurt and embarrassment as if it were yesterday.

Coming from the Deep South, I was very familiar with racial bias, but I did not expect it at that level and in that environment. From that point on, I was anxious at each patient encounter, concerned that this might happen again. And it did several times during my residency and fellowship.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines workplace violence as “any act or threat of physical violence, harassment, intimidation, or other threatening disruptive behavior that occurs at the work site. It ranges from threats and verbal abuse to physical assaults.”

There is considerable media focus on incidents of physical violence against health care workers, but when patients, their families, or visitors openly display bias and request a different doctor, nurse, or technician for nonmedical reasons, the impact is profound. This is extremely hurtful to a professional who has worked long and hard to acquire skills and expertise. And, while speech may not constitute violence in the strictest sense of the word, there is growing evidence that it can be physically harmful through its effect on the nervous system, even if no physical contact is involved.

Incidents of bias occur regularly and are clearly on the rise. In most cases the request for a different health care worker is granted to honor the rights of the patient. The healthcare worker is left alone and emotionally wounded; the healthcare institutions are complicit.

This bias is mostly racial but can also be based on religion, sexual orientation, age, disability, body size, accent, or gender.

An entire issue of the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics was devoted to this topic. From recognizing that there are limits to what clinicians should be expected to tolerate when patients’ preferences express unjust bias, the issue also explored where those limits should be placed, why, and who is obliged to enforce them.

The newly adopted Mass General Patient Code of Conduct is evidence that health care systems are beginning to recognize this problem and that such behavior will not be tolerated.

But having a zero-tolerance policy is not enough. We must have procedures in place to discourage and mitigate the impact of patient bias.

A clear definition of what constitutes a bias incident is essential. All team members must be made aware of the procedures for reporting such incidents and the chain of command for escalation. Reporting should be encouraged, and resources must be made available to impacted team members. Surveillance, monitoring, and review are also essential as is clarification on when patient preferences should be honored.

The Mayo Clinic 5 Step Plan is an excellent example of a protocol to deal with patient bias against health care workers and is based on a thoughtful analysis of what constitutes an unreasonable request for a different clinician. I’m pleased to report that my health care system (Inova Health) is developing a similar protocol.