User login

Compulsively checking social media linked with altered brain patterns in teens

Teens who compulsively checked social media networks showed different development patterns in parts of the brain that involve reward and punishment than did those who didn’t check their platforms as often, new research suggests.

Results were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Researchers, led by Maria T. Maza, of the department of psychology and neuroscience at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, included 169 6th- and 7th-grade students recruited from three public middle schools in rural North Carolina in a 3-year longitudinal cohort.

Participants reported how frequently they checked Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. Answers were grouped into eight score groups depending on their per-day check times: less than 1; 1; 2-3; 4-5; 6-10; 11-15; 16-20; or more than 20 times. Those groups were then broken into three categories: low (nonhabitual); moderate; and high (habitual).

Imaging shows reactions

Researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to see how different areas of the brain react when participants looked at a series of indicators, such as happy and angry faces, which mimic social media rewards, punishments, or neutral feedback.

The research team focused on adolescents, for whom social media participation and neural sensitivity to social feedback from peers are high.

They found that participants who frequently checked social media showed distinct brain patterns when anticipating social feedback compared with those who had moderate or low use, “suggesting that habitual social media checking early in adolescence is associated with divergent brain development over time.”

The affected regions of the brain included the networks that respond to motivation and cognitive control.

However, the study was not able to determine whether the differences are a good or bad thing.

“While for some individuals with habitual checking behaviors, an initial hyposensitivity to potential social rewards and punishments followed by hypersensitivity may contribute to checking behaviors on social media becoming compulsive and problematic, for others, this change in sensitivity may reflect an adaptive behavior that allows them to better navigate their increasingly digital environment,” the authors wrote.

Chicken-and-egg questions

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of this research, said in an interview that it’s not clear from this study which came first – different brain development in the teens prior to this study that caused compulsive checking, or checking behaviors that caused different brain development. The authors acknowledge this is a limitation of the study.

“Hopefully, someday researchers will look at some of these brain activation patterns before kids have been exposed to social media to help us sort some of these questions out,” Dr. Rettew said.

“It wasn’t as though the groups looked the same at baseline and then diverged as they used more and more social media,” Dr. Rettew said. “It looked like there were some baseline differences that could be traced back maybe years before the study even started.”

People hear “divergent brain development” associated with social media and naturally get alarmed, he acknowledged.

“I get that, but the study isn’t really equipped to tell us what should be happening in the brain and what changes may have implications for other parts of an adolescent’s life,” Dr. Rettew said, “In the end, what we have is an association between heavy social media use and certain brain activation patterns which is cool to see and measure.”

He agrees with the authors, however, that overuse of social media is concerning and studying its effects is important.

Seventy-eight percent of early adolescents check every hour

According to the paper, 78% of 13- to 17-year-olds report checking their devices at least every hour and 46% check “almost constantly.”

“Regardless of which brain regions light up when looking at various emoji responses to their Instagram post, I think it is valid already to have some concerns about youth who can’t stay off their phone for more than 10 minutes,” Dr. Rettew said. “Technology is here to stay, but how we can learn to use it rather than have it use us is probably the more pressing question at this point.”

One coauthor reports grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) during the conduct of the study and grants from NIDA and the National Science Foundation outside the submitted work; a coauthor reports grants from the Winston Family Foundation; and a coauthor reports a grant from NIDA and funds from the Winston Family Foundation – both during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Rettew is author of the book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.”

Teens who compulsively checked social media networks showed different development patterns in parts of the brain that involve reward and punishment than did those who didn’t check their platforms as often, new research suggests.

Results were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Researchers, led by Maria T. Maza, of the department of psychology and neuroscience at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, included 169 6th- and 7th-grade students recruited from three public middle schools in rural North Carolina in a 3-year longitudinal cohort.

Participants reported how frequently they checked Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. Answers were grouped into eight score groups depending on their per-day check times: less than 1; 1; 2-3; 4-5; 6-10; 11-15; 16-20; or more than 20 times. Those groups were then broken into three categories: low (nonhabitual); moderate; and high (habitual).

Imaging shows reactions

Researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to see how different areas of the brain react when participants looked at a series of indicators, such as happy and angry faces, which mimic social media rewards, punishments, or neutral feedback.

The research team focused on adolescents, for whom social media participation and neural sensitivity to social feedback from peers are high.

They found that participants who frequently checked social media showed distinct brain patterns when anticipating social feedback compared with those who had moderate or low use, “suggesting that habitual social media checking early in adolescence is associated with divergent brain development over time.”

The affected regions of the brain included the networks that respond to motivation and cognitive control.

However, the study was not able to determine whether the differences are a good or bad thing.

“While for some individuals with habitual checking behaviors, an initial hyposensitivity to potential social rewards and punishments followed by hypersensitivity may contribute to checking behaviors on social media becoming compulsive and problematic, for others, this change in sensitivity may reflect an adaptive behavior that allows them to better navigate their increasingly digital environment,” the authors wrote.

Chicken-and-egg questions

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of this research, said in an interview that it’s not clear from this study which came first – different brain development in the teens prior to this study that caused compulsive checking, or checking behaviors that caused different brain development. The authors acknowledge this is a limitation of the study.

“Hopefully, someday researchers will look at some of these brain activation patterns before kids have been exposed to social media to help us sort some of these questions out,” Dr. Rettew said.

“It wasn’t as though the groups looked the same at baseline and then diverged as they used more and more social media,” Dr. Rettew said. “It looked like there were some baseline differences that could be traced back maybe years before the study even started.”

People hear “divergent brain development” associated with social media and naturally get alarmed, he acknowledged.

“I get that, but the study isn’t really equipped to tell us what should be happening in the brain and what changes may have implications for other parts of an adolescent’s life,” Dr. Rettew said, “In the end, what we have is an association between heavy social media use and certain brain activation patterns which is cool to see and measure.”

He agrees with the authors, however, that overuse of social media is concerning and studying its effects is important.

Seventy-eight percent of early adolescents check every hour

According to the paper, 78% of 13- to 17-year-olds report checking their devices at least every hour and 46% check “almost constantly.”

“Regardless of which brain regions light up when looking at various emoji responses to their Instagram post, I think it is valid already to have some concerns about youth who can’t stay off their phone for more than 10 minutes,” Dr. Rettew said. “Technology is here to stay, but how we can learn to use it rather than have it use us is probably the more pressing question at this point.”

One coauthor reports grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) during the conduct of the study and grants from NIDA and the National Science Foundation outside the submitted work; a coauthor reports grants from the Winston Family Foundation; and a coauthor reports a grant from NIDA and funds from the Winston Family Foundation – both during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Rettew is author of the book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.”

Teens who compulsively checked social media networks showed different development patterns in parts of the brain that involve reward and punishment than did those who didn’t check their platforms as often, new research suggests.

Results were published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

Researchers, led by Maria T. Maza, of the department of psychology and neuroscience at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, included 169 6th- and 7th-grade students recruited from three public middle schools in rural North Carolina in a 3-year longitudinal cohort.

Participants reported how frequently they checked Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. Answers were grouped into eight score groups depending on their per-day check times: less than 1; 1; 2-3; 4-5; 6-10; 11-15; 16-20; or more than 20 times. Those groups were then broken into three categories: low (nonhabitual); moderate; and high (habitual).

Imaging shows reactions

Researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to see how different areas of the brain react when participants looked at a series of indicators, such as happy and angry faces, which mimic social media rewards, punishments, or neutral feedback.

The research team focused on adolescents, for whom social media participation and neural sensitivity to social feedback from peers are high.

They found that participants who frequently checked social media showed distinct brain patterns when anticipating social feedback compared with those who had moderate or low use, “suggesting that habitual social media checking early in adolescence is associated with divergent brain development over time.”

The affected regions of the brain included the networks that respond to motivation and cognitive control.

However, the study was not able to determine whether the differences are a good or bad thing.

“While for some individuals with habitual checking behaviors, an initial hyposensitivity to potential social rewards and punishments followed by hypersensitivity may contribute to checking behaviors on social media becoming compulsive and problematic, for others, this change in sensitivity may reflect an adaptive behavior that allows them to better navigate their increasingly digital environment,” the authors wrote.

Chicken-and-egg questions

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, who was not part of this research, said in an interview that it’s not clear from this study which came first – different brain development in the teens prior to this study that caused compulsive checking, or checking behaviors that caused different brain development. The authors acknowledge this is a limitation of the study.

“Hopefully, someday researchers will look at some of these brain activation patterns before kids have been exposed to social media to help us sort some of these questions out,” Dr. Rettew said.

“It wasn’t as though the groups looked the same at baseline and then diverged as they used more and more social media,” Dr. Rettew said. “It looked like there were some baseline differences that could be traced back maybe years before the study even started.”

People hear “divergent brain development” associated with social media and naturally get alarmed, he acknowledged.

“I get that, but the study isn’t really equipped to tell us what should be happening in the brain and what changes may have implications for other parts of an adolescent’s life,” Dr. Rettew said, “In the end, what we have is an association between heavy social media use and certain brain activation patterns which is cool to see and measure.”

He agrees with the authors, however, that overuse of social media is concerning and studying its effects is important.

Seventy-eight percent of early adolescents check every hour

According to the paper, 78% of 13- to 17-year-olds report checking their devices at least every hour and 46% check “almost constantly.”

“Regardless of which brain regions light up when looking at various emoji responses to their Instagram post, I think it is valid already to have some concerns about youth who can’t stay off their phone for more than 10 minutes,” Dr. Rettew said. “Technology is here to stay, but how we can learn to use it rather than have it use us is probably the more pressing question at this point.”

One coauthor reports grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) during the conduct of the study and grants from NIDA and the National Science Foundation outside the submitted work; a coauthor reports grants from the Winston Family Foundation; and a coauthor reports a grant from NIDA and funds from the Winston Family Foundation – both during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Rettew is author of the book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.”

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

The anecdote as antidote: Psychiatric paradigms in Disney films

A common refrain in psychiatry is that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, (DSM-5-TR), published in 2022, is the best we can do.

Since the DSM-III was released in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the manual, has espoused the position that we should list symptoms, in a manner that is reminiscent of a checklist. For example, having a depressed mood on most days for a 2-week period, or a loss of interest in pleasurable things, as well as 4 additional symptoms – among them changes in appetite, changes in sleep, changes in psychomotor activity, fatigue, worthlessness, poor concentration, or thoughts of death – can lead to a diagnosis of a major depressive episode as part of a major depressive disorder.

Criticisms of this approach can be apparent. Patients subjected to such checklists, including being repeatedly asked to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), which closely follows those criteria, can feel lost and even alienated by their providers. After all, one can ask all those questions and make a diagnosis of depression without even knowing about the patient’s stressors, their history, or their social context.

The DSM permits the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders without an understanding of the narrative of the patient. In its defense, the DSM is not a textbook of psychiatry, it is a guide on how to diagnose individuals. The DSM does not demand that psychiatrists only ask about the symptoms on the checklists; it is the providers who can choose to dismiss asking about the important facets of one’s life.

Yet every time we attend a lecture that starts by enumerating the DSM symptoms of the disorder being discussed, we are left with the dissatisfying impression that a specialist of this disorder should have a more nuanced and interesting description of their disorder of study. This feeling of discontent is compounded when we see a movie that encompasses so much of what is missing in today’s psychiatric parlance, and even more so if that movie is ostensibly made for children. Movies, by design, are particularly adept at encapsulating the narrative of someone’s life in a way that psychiatry can learn from.

Other than the embarrassment of not knowing a patient outside the checklist, the importance of narrative cannot be understated. Dr. Erik Erikson rightfully suggested that the point of life is “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle”1 or rather to know it was okay to have been oneself without additions or substitutions. Therefore, one must know what it has meant to be themselves to reconcile this question and achieve Ego Integrity rather than disgust and despair. Narrative is the way in which we understand who we are and what it has meant to be ourselves. An understanding of our personal narrative presents a unique opportunity in expressing what is missing in the DSM. Below, we provide two of our favorite examples in Disney films, among many.

‘Ratatouille’ (2007)

One of the missing features of the DSM is its inability to explain to patients the intrapsychic processes that guide us. One of these processes is how our values can lead us to a deep sense of guilt, shame, and the resulting feelings of alienation. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling shackled by beliefs that they should accomplish more and be more than they are.

The animated film “Ratatouille” does an excellent job at addressing this feeling. The film follows Remy, the protagonist rat, and his adventures as he explores his passion for cooking. Remy teams up with the inept but good-natured human Alfredo Linguini and guides him through cooking while hiding under his chef’s hat. The primary antagonist, Anton Ego, is a particularly harsh food critic. His presence and appearance are somber. He exudes disdain. His trim physique and scarf suggest a man that will break and react to anything, and his skull-shaped typewriter in his coffin-shaped office informs the viewer that he is out to kill with his cruel words. Anton Ego serves as our projected super-ego. He is not an external judge but the judgment deep inside ourselves, goading us to be better with such severity that we are ultimately left feeling condemned.

Remy is the younger of two siblings. He is less physically adept but more intellectual than his older brother, who does not understand why Remy isn’t content eating scraps from the garbage like the rest of their rat clan. Remy is the creative part within us that wants to challenge the status quo and try something new. Remy also represents our shame and guilt for leaving our home. On one hand, we want to dare greatly, in this case at being an extraordinary chef, but on the other we are shy and cook in secret, hiding within the hat of another person. Remy struggles with the deep feeling that we do not deserve our success, that our family will leave us for being who we are, and that we are better off isolating and segregating from our challenges.

The movie concludes that through talent and hard work, our critics will accept us. Furthermore, once accepted for what we do, we can be further accepted for who we are. The movie ends with Remy cooking the eponymous dish ratatouille. He prepares it so remarkably well, the dish transports Anton Ego back to a sublime experience of eating ratatouille as a child, a touching moment which not only underscores food’s evocative link to memory but gives a glimpse at Anton Ego’s own narrative.

Ego is first won over by the dish, and only afterward learns of Remy’s true identity. Remy’s talent is undeniable though, and even the stuffy Ego must accept the film’s theme that “Anyone can cook,” even a rat – the rat that we all sometimes feel we are deep inside, rotten to the core but trying so hard to be accepted by others, and ultimately by ourselves. In the end, we overcome the disgust inherent in the imagery of a rat in a kitchen and instead embrace our hero’s achievement of ego integrity as he combines his identities as a member of a clan of rats, and one of Paris’s finest chefs.

While modern psychiatry can favor looking at people through the lens of biology rather than narrative, “Ratatouille” can serve as a reminder of the powerful unconscious forces that guide our lives. “Ratatouille” is not a successful movie only because of the compelling narrative, but also because the narrative matches the important psychic paradigms that psychiatry once embraced.

‘Inside Out’ (2015)

Another missing feature of the DSM is its inability to explain how symptoms feel and manifest psychologically. One such feeling is that of control – whether one is in control of one’s life, feelings, and action or rather a victim of external forces. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling traumatized by the life they’ve lived and powerless to produce any change. Part of our role is to guide them through this journey from the object of their lives to the subject of their lives.

In the animated feature “Inside Out,” Riley, a preteen girl, goes through the tribulation of growing up and learning about herself. This seemingly happy child, content playing hockey with her best friend, Meg, on the picturesque frozen lakes of Minnesota, reaches her inevitable conflict. Her parents uproot her life, moving the family to San Francisco. By doing so, they disconnect her from her school, her friends, and her hobbies. While all this is happening, we spend time inside Riley’s psyche with the personified characters of Riley’s emotions as they affect her decisions and daily actions amidst the backdrop of her core memories and islands of personality.

During the move, her parents seemingly change and ultimately destroy every facet of Riley’s sense of self, which is animated as the collapse of her personality islands. Her best friend engages Riley in a video call just to inform her that she has a new friend who plays hockey equally well. Her parents do not hear Riley’s concerns and are portrayed as distracted by their adult problems. Riley feels ridiculed in her new school and unable to share her feelings with her parents, who ask her to still be their “happy girl” and indirectly ask her to fake pleasure to alleviate their own anxiety.

The climax of the movie is when Riley decides to run away from San Francisco and her parents, to return to her perceived true home, Minnesota. The climax is resolved when Riley realizes that her parents’ love, representing the connection we have to others, transcends her need for control. To some degree, we are all powerless in the face of the tremendous forces of life and share the difficult task of accepting the cards we were dealt, thus making the story of Riley so compelling.

Additionally, the climax is further resolved by another argument that psychiatry (and the DSM) should consider embracing. Emotions are not all symptoms and living without negative emotion is not the goal of life. Riley grows from preteen to teenager, and from object to subject of her life, by realizing that her symptoms/feelings are not just nuisances to avoid and hide, but the key to meaning. Our anger drives us to try hard. Our fear protects us from harm. Our sadness attracts the warmth and care of others. Our disgust protects us physically from noxious material (symbolized as a dreaded broccoli floret for preteen Riley) and socially by encouraging us to share societal norms. Similarly, patients and people in general would benefit by being taught that, while symptoms may permit the better assessment of psychiatric conditions using the DSM, life is much more than that.

It is unfair to blame the DSM for things it was not designed to do. The DSM doesn’t advertise itself as a guidebook of all behaviors, at all times. However, for a variety of reasons, it has become the main way psychiatry describes people. While we commend the APA for its effort and do not know that we could make it any better, we are frequently happily reminded that in about 90 minutes, filmmakers are able to display an empathic understanding of personal narratives that biologic psychiatry can miss.

Dr. Pulido is a psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She is interested in women’s mental health, medical education, and outpatient psychiatry. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Erikson, EH. Childhood and society (New York: WW Norton, 1950).

A common refrain in psychiatry is that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, (DSM-5-TR), published in 2022, is the best we can do.

Since the DSM-III was released in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the manual, has espoused the position that we should list symptoms, in a manner that is reminiscent of a checklist. For example, having a depressed mood on most days for a 2-week period, or a loss of interest in pleasurable things, as well as 4 additional symptoms – among them changes in appetite, changes in sleep, changes in psychomotor activity, fatigue, worthlessness, poor concentration, or thoughts of death – can lead to a diagnosis of a major depressive episode as part of a major depressive disorder.

Criticisms of this approach can be apparent. Patients subjected to such checklists, including being repeatedly asked to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), which closely follows those criteria, can feel lost and even alienated by their providers. After all, one can ask all those questions and make a diagnosis of depression without even knowing about the patient’s stressors, their history, or their social context.

The DSM permits the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders without an understanding of the narrative of the patient. In its defense, the DSM is not a textbook of psychiatry, it is a guide on how to diagnose individuals. The DSM does not demand that psychiatrists only ask about the symptoms on the checklists; it is the providers who can choose to dismiss asking about the important facets of one’s life.

Yet every time we attend a lecture that starts by enumerating the DSM symptoms of the disorder being discussed, we are left with the dissatisfying impression that a specialist of this disorder should have a more nuanced and interesting description of their disorder of study. This feeling of discontent is compounded when we see a movie that encompasses so much of what is missing in today’s psychiatric parlance, and even more so if that movie is ostensibly made for children. Movies, by design, are particularly adept at encapsulating the narrative of someone’s life in a way that psychiatry can learn from.

Other than the embarrassment of not knowing a patient outside the checklist, the importance of narrative cannot be understated. Dr. Erik Erikson rightfully suggested that the point of life is “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle”1 or rather to know it was okay to have been oneself without additions or substitutions. Therefore, one must know what it has meant to be themselves to reconcile this question and achieve Ego Integrity rather than disgust and despair. Narrative is the way in which we understand who we are and what it has meant to be ourselves. An understanding of our personal narrative presents a unique opportunity in expressing what is missing in the DSM. Below, we provide two of our favorite examples in Disney films, among many.

‘Ratatouille’ (2007)

One of the missing features of the DSM is its inability to explain to patients the intrapsychic processes that guide us. One of these processes is how our values can lead us to a deep sense of guilt, shame, and the resulting feelings of alienation. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling shackled by beliefs that they should accomplish more and be more than they are.

The animated film “Ratatouille” does an excellent job at addressing this feeling. The film follows Remy, the protagonist rat, and his adventures as he explores his passion for cooking. Remy teams up with the inept but good-natured human Alfredo Linguini and guides him through cooking while hiding under his chef’s hat. The primary antagonist, Anton Ego, is a particularly harsh food critic. His presence and appearance are somber. He exudes disdain. His trim physique and scarf suggest a man that will break and react to anything, and his skull-shaped typewriter in his coffin-shaped office informs the viewer that he is out to kill with his cruel words. Anton Ego serves as our projected super-ego. He is not an external judge but the judgment deep inside ourselves, goading us to be better with such severity that we are ultimately left feeling condemned.

Remy is the younger of two siblings. He is less physically adept but more intellectual than his older brother, who does not understand why Remy isn’t content eating scraps from the garbage like the rest of their rat clan. Remy is the creative part within us that wants to challenge the status quo and try something new. Remy also represents our shame and guilt for leaving our home. On one hand, we want to dare greatly, in this case at being an extraordinary chef, but on the other we are shy and cook in secret, hiding within the hat of another person. Remy struggles with the deep feeling that we do not deserve our success, that our family will leave us for being who we are, and that we are better off isolating and segregating from our challenges.

The movie concludes that through talent and hard work, our critics will accept us. Furthermore, once accepted for what we do, we can be further accepted for who we are. The movie ends with Remy cooking the eponymous dish ratatouille. He prepares it so remarkably well, the dish transports Anton Ego back to a sublime experience of eating ratatouille as a child, a touching moment which not only underscores food’s evocative link to memory but gives a glimpse at Anton Ego’s own narrative.

Ego is first won over by the dish, and only afterward learns of Remy’s true identity. Remy’s talent is undeniable though, and even the stuffy Ego must accept the film’s theme that “Anyone can cook,” even a rat – the rat that we all sometimes feel we are deep inside, rotten to the core but trying so hard to be accepted by others, and ultimately by ourselves. In the end, we overcome the disgust inherent in the imagery of a rat in a kitchen and instead embrace our hero’s achievement of ego integrity as he combines his identities as a member of a clan of rats, and one of Paris’s finest chefs.

While modern psychiatry can favor looking at people through the lens of biology rather than narrative, “Ratatouille” can serve as a reminder of the powerful unconscious forces that guide our lives. “Ratatouille” is not a successful movie only because of the compelling narrative, but also because the narrative matches the important psychic paradigms that psychiatry once embraced.

‘Inside Out’ (2015)

Another missing feature of the DSM is its inability to explain how symptoms feel and manifest psychologically. One such feeling is that of control – whether one is in control of one’s life, feelings, and action or rather a victim of external forces. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling traumatized by the life they’ve lived and powerless to produce any change. Part of our role is to guide them through this journey from the object of their lives to the subject of their lives.

In the animated feature “Inside Out,” Riley, a preteen girl, goes through the tribulation of growing up and learning about herself. This seemingly happy child, content playing hockey with her best friend, Meg, on the picturesque frozen lakes of Minnesota, reaches her inevitable conflict. Her parents uproot her life, moving the family to San Francisco. By doing so, they disconnect her from her school, her friends, and her hobbies. While all this is happening, we spend time inside Riley’s psyche with the personified characters of Riley’s emotions as they affect her decisions and daily actions amidst the backdrop of her core memories and islands of personality.

During the move, her parents seemingly change and ultimately destroy every facet of Riley’s sense of self, which is animated as the collapse of her personality islands. Her best friend engages Riley in a video call just to inform her that she has a new friend who plays hockey equally well. Her parents do not hear Riley’s concerns and are portrayed as distracted by their adult problems. Riley feels ridiculed in her new school and unable to share her feelings with her parents, who ask her to still be their “happy girl” and indirectly ask her to fake pleasure to alleviate their own anxiety.

The climax of the movie is when Riley decides to run away from San Francisco and her parents, to return to her perceived true home, Minnesota. The climax is resolved when Riley realizes that her parents’ love, representing the connection we have to others, transcends her need for control. To some degree, we are all powerless in the face of the tremendous forces of life and share the difficult task of accepting the cards we were dealt, thus making the story of Riley so compelling.

Additionally, the climax is further resolved by another argument that psychiatry (and the DSM) should consider embracing. Emotions are not all symptoms and living without negative emotion is not the goal of life. Riley grows from preteen to teenager, and from object to subject of her life, by realizing that her symptoms/feelings are not just nuisances to avoid and hide, but the key to meaning. Our anger drives us to try hard. Our fear protects us from harm. Our sadness attracts the warmth and care of others. Our disgust protects us physically from noxious material (symbolized as a dreaded broccoli floret for preteen Riley) and socially by encouraging us to share societal norms. Similarly, patients and people in general would benefit by being taught that, while symptoms may permit the better assessment of psychiatric conditions using the DSM, life is much more than that.

It is unfair to blame the DSM for things it was not designed to do. The DSM doesn’t advertise itself as a guidebook of all behaviors, at all times. However, for a variety of reasons, it has become the main way psychiatry describes people. While we commend the APA for its effort and do not know that we could make it any better, we are frequently happily reminded that in about 90 minutes, filmmakers are able to display an empathic understanding of personal narratives that biologic psychiatry can miss.

Dr. Pulido is a psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She is interested in women’s mental health, medical education, and outpatient psychiatry. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Erikson, EH. Childhood and society (New York: WW Norton, 1950).

A common refrain in psychiatry is that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, (DSM-5-TR), published in 2022, is the best we can do.

Since the DSM-III was released in 1980, the American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the manual, has espoused the position that we should list symptoms, in a manner that is reminiscent of a checklist. For example, having a depressed mood on most days for a 2-week period, or a loss of interest in pleasurable things, as well as 4 additional symptoms – among them changes in appetite, changes in sleep, changes in psychomotor activity, fatigue, worthlessness, poor concentration, or thoughts of death – can lead to a diagnosis of a major depressive episode as part of a major depressive disorder.

Criticisms of this approach can be apparent. Patients subjected to such checklists, including being repeatedly asked to complete the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), which closely follows those criteria, can feel lost and even alienated by their providers. After all, one can ask all those questions and make a diagnosis of depression without even knowing about the patient’s stressors, their history, or their social context.

The DSM permits the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders without an understanding of the narrative of the patient. In its defense, the DSM is not a textbook of psychiatry, it is a guide on how to diagnose individuals. The DSM does not demand that psychiatrists only ask about the symptoms on the checklists; it is the providers who can choose to dismiss asking about the important facets of one’s life.

Yet every time we attend a lecture that starts by enumerating the DSM symptoms of the disorder being discussed, we are left with the dissatisfying impression that a specialist of this disorder should have a more nuanced and interesting description of their disorder of study. This feeling of discontent is compounded when we see a movie that encompasses so much of what is missing in today’s psychiatric parlance, and even more so if that movie is ostensibly made for children. Movies, by design, are particularly adept at encapsulating the narrative of someone’s life in a way that psychiatry can learn from.

Other than the embarrassment of not knowing a patient outside the checklist, the importance of narrative cannot be understated. Dr. Erik Erikson rightfully suggested that the point of life is “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle”1 or rather to know it was okay to have been oneself without additions or substitutions. Therefore, one must know what it has meant to be themselves to reconcile this question and achieve Ego Integrity rather than disgust and despair. Narrative is the way in which we understand who we are and what it has meant to be ourselves. An understanding of our personal narrative presents a unique opportunity in expressing what is missing in the DSM. Below, we provide two of our favorite examples in Disney films, among many.

‘Ratatouille’ (2007)

One of the missing features of the DSM is its inability to explain to patients the intrapsychic processes that guide us. One of these processes is how our values can lead us to a deep sense of guilt, shame, and the resulting feelings of alienation. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling shackled by beliefs that they should accomplish more and be more than they are.

The animated film “Ratatouille” does an excellent job at addressing this feeling. The film follows Remy, the protagonist rat, and his adventures as he explores his passion for cooking. Remy teams up with the inept but good-natured human Alfredo Linguini and guides him through cooking while hiding under his chef’s hat. The primary antagonist, Anton Ego, is a particularly harsh food critic. His presence and appearance are somber. He exudes disdain. His trim physique and scarf suggest a man that will break and react to anything, and his skull-shaped typewriter in his coffin-shaped office informs the viewer that he is out to kill with his cruel words. Anton Ego serves as our projected super-ego. He is not an external judge but the judgment deep inside ourselves, goading us to be better with such severity that we are ultimately left feeling condemned.

Remy is the younger of two siblings. He is less physically adept but more intellectual than his older brother, who does not understand why Remy isn’t content eating scraps from the garbage like the rest of their rat clan. Remy is the creative part within us that wants to challenge the status quo and try something new. Remy also represents our shame and guilt for leaving our home. On one hand, we want to dare greatly, in this case at being an extraordinary chef, but on the other we are shy and cook in secret, hiding within the hat of another person. Remy struggles with the deep feeling that we do not deserve our success, that our family will leave us for being who we are, and that we are better off isolating and segregating from our challenges.

The movie concludes that through talent and hard work, our critics will accept us. Furthermore, once accepted for what we do, we can be further accepted for who we are. The movie ends with Remy cooking the eponymous dish ratatouille. He prepares it so remarkably well, the dish transports Anton Ego back to a sublime experience of eating ratatouille as a child, a touching moment which not only underscores food’s evocative link to memory but gives a glimpse at Anton Ego’s own narrative.

Ego is first won over by the dish, and only afterward learns of Remy’s true identity. Remy’s talent is undeniable though, and even the stuffy Ego must accept the film’s theme that “Anyone can cook,” even a rat – the rat that we all sometimes feel we are deep inside, rotten to the core but trying so hard to be accepted by others, and ultimately by ourselves. In the end, we overcome the disgust inherent in the imagery of a rat in a kitchen and instead embrace our hero’s achievement of ego integrity as he combines his identities as a member of a clan of rats, and one of Paris’s finest chefs.

While modern psychiatry can favor looking at people through the lens of biology rather than narrative, “Ratatouille” can serve as a reminder of the powerful unconscious forces that guide our lives. “Ratatouille” is not a successful movie only because of the compelling narrative, but also because the narrative matches the important psychic paradigms that psychiatry once embraced.

‘Inside Out’ (2015)

Another missing feature of the DSM is its inability to explain how symptoms feel and manifest psychologically. One such feeling is that of control – whether one is in control of one’s life, feelings, and action or rather a victim of external forces. It is extremely common for patients to enter our clinical practice feeling traumatized by the life they’ve lived and powerless to produce any change. Part of our role is to guide them through this journey from the object of their lives to the subject of their lives.

In the animated feature “Inside Out,” Riley, a preteen girl, goes through the tribulation of growing up and learning about herself. This seemingly happy child, content playing hockey with her best friend, Meg, on the picturesque frozen lakes of Minnesota, reaches her inevitable conflict. Her parents uproot her life, moving the family to San Francisco. By doing so, they disconnect her from her school, her friends, and her hobbies. While all this is happening, we spend time inside Riley’s psyche with the personified characters of Riley’s emotions as they affect her decisions and daily actions amidst the backdrop of her core memories and islands of personality.

During the move, her parents seemingly change and ultimately destroy every facet of Riley’s sense of self, which is animated as the collapse of her personality islands. Her best friend engages Riley in a video call just to inform her that she has a new friend who plays hockey equally well. Her parents do not hear Riley’s concerns and are portrayed as distracted by their adult problems. Riley feels ridiculed in her new school and unable to share her feelings with her parents, who ask her to still be their “happy girl” and indirectly ask her to fake pleasure to alleviate their own anxiety.

The climax of the movie is when Riley decides to run away from San Francisco and her parents, to return to her perceived true home, Minnesota. The climax is resolved when Riley realizes that her parents’ love, representing the connection we have to others, transcends her need for control. To some degree, we are all powerless in the face of the tremendous forces of life and share the difficult task of accepting the cards we were dealt, thus making the story of Riley so compelling.

Additionally, the climax is further resolved by another argument that psychiatry (and the DSM) should consider embracing. Emotions are not all symptoms and living without negative emotion is not the goal of life. Riley grows from preteen to teenager, and from object to subject of her life, by realizing that her symptoms/feelings are not just nuisances to avoid and hide, but the key to meaning. Our anger drives us to try hard. Our fear protects us from harm. Our sadness attracts the warmth and care of others. Our disgust protects us physically from noxious material (symbolized as a dreaded broccoli floret for preteen Riley) and socially by encouraging us to share societal norms. Similarly, patients and people in general would benefit by being taught that, while symptoms may permit the better assessment of psychiatric conditions using the DSM, life is much more than that.

It is unfair to blame the DSM for things it was not designed to do. The DSM doesn’t advertise itself as a guidebook of all behaviors, at all times. However, for a variety of reasons, it has become the main way psychiatry describes people. While we commend the APA for its effort and do not know that we could make it any better, we are frequently happily reminded that in about 90 minutes, filmmakers are able to display an empathic understanding of personal narratives that biologic psychiatry can miss.

Dr. Pulido is a psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She is interested in women’s mental health, medical education, and outpatient psychiatry. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Erikson, EH. Childhood and society (New York: WW Norton, 1950).

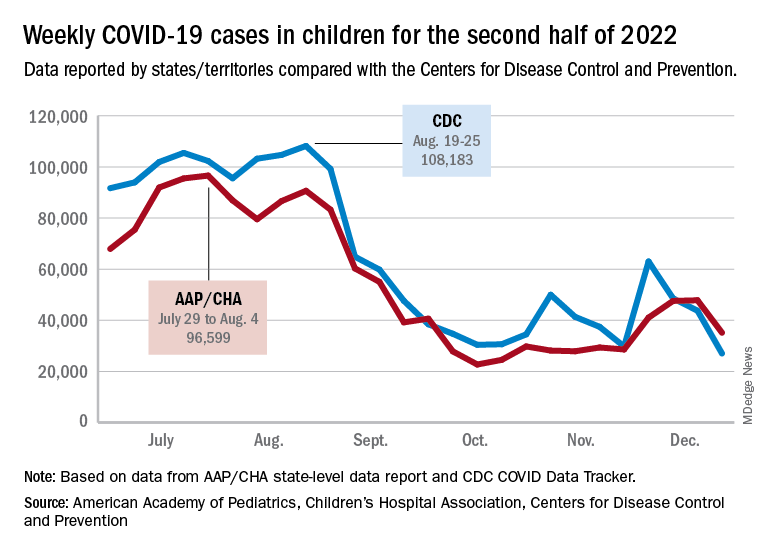

Children and COVID: New cases fell as the old year ended

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

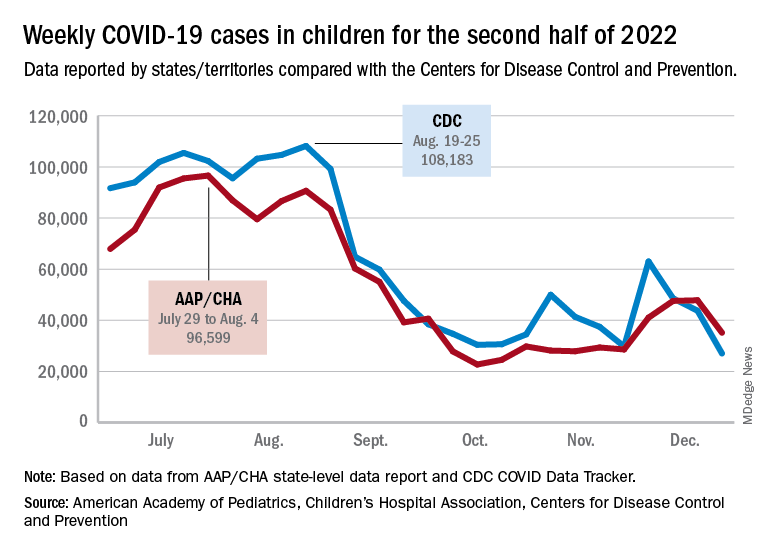

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

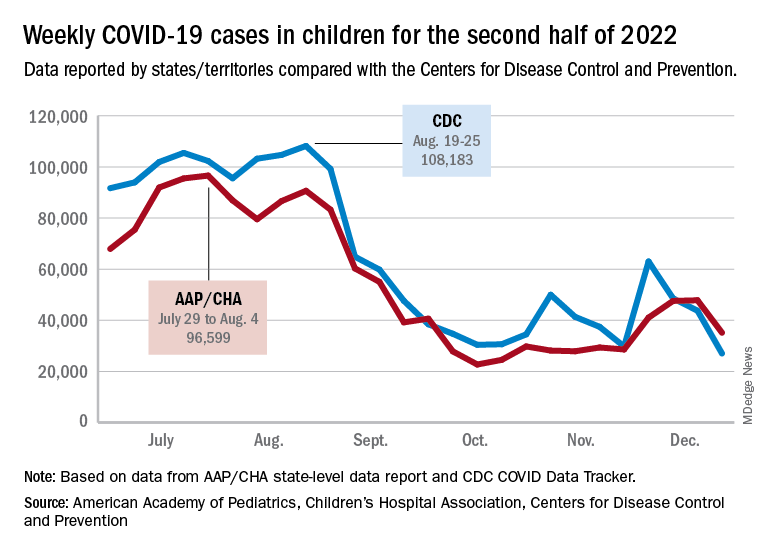

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

Nearly 1,400% rise in young children ingesting cannabis edibles

according to a new analysis of data from poison control centers.

In 2017, centers received 207 reports of children aged 5 years and younger who ingested edible cannabis. In 2021, 3,054 such cases were reported, according to the study, which was published online in Pediatrics.

Many of the children experienced clinical effects, such as depression of the central nervous system, impaired coordination, confusion, agitation, an increase in heart rate, or dilated pupils. No deaths were reported.

“These exposures can cause significant toxicity and are responsible for an increasing number of hospitalizations,” study coauthor Marit S. Tweet, MD, of Southern Illinois University, Springfield, and colleagues wrote.

About 97% of the exposures occurred in residences – 90% at the child’s own home – and about half of the cases involved 2- and 3-year-olds, they noted.

Examining national trends

Twenty-one states have approved recreational cannabis for people aged 21 years and older.

Prior research has shown that calls to poison centers and visits to emergency departments for pediatric cannabis consumption increased in certain states after the drug became legal in those jurisdictions.

To assess national trends, Dr. Tweet’s group analyzed cases in the National Poison Data System, which tracks potentially toxic exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States.

During the 5-year period, they identified 7,043 exposures to edible cannabis by children younger than age 6. In 2.2% of the cases, the drug had a major effect, defined as being either life-threatening or causing residual disability. In 21.9% of cases, the effect was considered to be moderate, with symptoms that were more pronounced, prolonged, or systemic than minor effects.

About 8% of the children were admitted to critical care units; 14.6% were admitted to non–critical care units.

Of 4,827 cases for which there was information about the clinical effects of the exposure and therapies used, 70% involved CNS depression, including 1.9% with “more severe CNS effects, including major CNS depression or coma,” according to the report.

Patients also experienced ataxia (7.4%), agitation (7.1%), confusion (6.1%), tremor (2%), and seizures (1.6%). Other common symptoms included tachycardia (11.4%), vomiting (9.5%), mydriasis (5.9%), and respiratory depression (3.1%).

Treatments for the exposures included intravenous fluids (20.7%), food or snacks (10.3%), and oxygen therapy (4%). Some patients also received naloxone (1.4%) or charcoal (2.1%).

“The total number of children requiring intubation during the study period was 35, or approximately 1 in 140,” the researchers reported. “Although this was a relatively rare occurrence, it is important for clinicians to be aware that life-threatening sequelae can develop and may necessitate invasive supportive care measures.”

Tempting and toxic

For toddlers, edible cannabis may be especially tempting and toxic. Edibles can “resemble common treats such as candies, chocolates, cookies, or other baked goods,” the researchers wrote. Children would not recognize, for example, that one chocolate bar might contain multiple 10-mg servings of tetrahydrocannabinol intended for adults.

Poison centers have been fielding more calls about edible cannabis use by older children, as well.

Adrienne Hughes, MD, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, recently found that many cases of intentional misuse and abuse by adolescents involve edible forms of cannabis.

“While marijuana carries a low risk for severe toxicity, it can be inebriating to the point of poor judgment, risk of falls or other injury, and occasionally a panic reaction in the novice user and unsuspecting children who accidentally ingest these products,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

Measures to keep edibles away from children could include changing how the products are packaged, limiting the maximum dose of drug per package, and educating the public about the risks to children, Dr. Tweet’s group wrote. They highlighted a 2019 position statement from the American College of Medical Toxicology that includes recommendations for responsible storage habits.

Dr. Hughes echoed one suggestion that is mentioned in the position statement: Parents should consider keeping their cannabis products locked up.

The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new analysis of data from poison control centers.

In 2017, centers received 207 reports of children aged 5 years and younger who ingested edible cannabis. In 2021, 3,054 such cases were reported, according to the study, which was published online in Pediatrics.

Many of the children experienced clinical effects, such as depression of the central nervous system, impaired coordination, confusion, agitation, an increase in heart rate, or dilated pupils. No deaths were reported.

“These exposures can cause significant toxicity and are responsible for an increasing number of hospitalizations,” study coauthor Marit S. Tweet, MD, of Southern Illinois University, Springfield, and colleagues wrote.

About 97% of the exposures occurred in residences – 90% at the child’s own home – and about half of the cases involved 2- and 3-year-olds, they noted.

Examining national trends

Twenty-one states have approved recreational cannabis for people aged 21 years and older.

Prior research has shown that calls to poison centers and visits to emergency departments for pediatric cannabis consumption increased in certain states after the drug became legal in those jurisdictions.

To assess national trends, Dr. Tweet’s group analyzed cases in the National Poison Data System, which tracks potentially toxic exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States.

During the 5-year period, they identified 7,043 exposures to edible cannabis by children younger than age 6. In 2.2% of the cases, the drug had a major effect, defined as being either life-threatening or causing residual disability. In 21.9% of cases, the effect was considered to be moderate, with symptoms that were more pronounced, prolonged, or systemic than minor effects.

About 8% of the children were admitted to critical care units; 14.6% were admitted to non–critical care units.

Of 4,827 cases for which there was information about the clinical effects of the exposure and therapies used, 70% involved CNS depression, including 1.9% with “more severe CNS effects, including major CNS depression or coma,” according to the report.

Patients also experienced ataxia (7.4%), agitation (7.1%), confusion (6.1%), tremor (2%), and seizures (1.6%). Other common symptoms included tachycardia (11.4%), vomiting (9.5%), mydriasis (5.9%), and respiratory depression (3.1%).

Treatments for the exposures included intravenous fluids (20.7%), food or snacks (10.3%), and oxygen therapy (4%). Some patients also received naloxone (1.4%) or charcoal (2.1%).

“The total number of children requiring intubation during the study period was 35, or approximately 1 in 140,” the researchers reported. “Although this was a relatively rare occurrence, it is important for clinicians to be aware that life-threatening sequelae can develop and may necessitate invasive supportive care measures.”

Tempting and toxic

For toddlers, edible cannabis may be especially tempting and toxic. Edibles can “resemble common treats such as candies, chocolates, cookies, or other baked goods,” the researchers wrote. Children would not recognize, for example, that one chocolate bar might contain multiple 10-mg servings of tetrahydrocannabinol intended for adults.

Poison centers have been fielding more calls about edible cannabis use by older children, as well.

Adrienne Hughes, MD, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, recently found that many cases of intentional misuse and abuse by adolescents involve edible forms of cannabis.

“While marijuana carries a low risk for severe toxicity, it can be inebriating to the point of poor judgment, risk of falls or other injury, and occasionally a panic reaction in the novice user and unsuspecting children who accidentally ingest these products,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

Measures to keep edibles away from children could include changing how the products are packaged, limiting the maximum dose of drug per package, and educating the public about the risks to children, Dr. Tweet’s group wrote. They highlighted a 2019 position statement from the American College of Medical Toxicology that includes recommendations for responsible storage habits.

Dr. Hughes echoed one suggestion that is mentioned in the position statement: Parents should consider keeping their cannabis products locked up.

The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new analysis of data from poison control centers.

In 2017, centers received 207 reports of children aged 5 years and younger who ingested edible cannabis. In 2021, 3,054 such cases were reported, according to the study, which was published online in Pediatrics.

Many of the children experienced clinical effects, such as depression of the central nervous system, impaired coordination, confusion, agitation, an increase in heart rate, or dilated pupils. No deaths were reported.

“These exposures can cause significant toxicity and are responsible for an increasing number of hospitalizations,” study coauthor Marit S. Tweet, MD, of Southern Illinois University, Springfield, and colleagues wrote.

About 97% of the exposures occurred in residences – 90% at the child’s own home – and about half of the cases involved 2- and 3-year-olds, they noted.

Examining national trends

Twenty-one states have approved recreational cannabis for people aged 21 years and older.

Prior research has shown that calls to poison centers and visits to emergency departments for pediatric cannabis consumption increased in certain states after the drug became legal in those jurisdictions.

To assess national trends, Dr. Tweet’s group analyzed cases in the National Poison Data System, which tracks potentially toxic exposures reported to poison control centers in the United States.

During the 5-year period, they identified 7,043 exposures to edible cannabis by children younger than age 6. In 2.2% of the cases, the drug had a major effect, defined as being either life-threatening or causing residual disability. In 21.9% of cases, the effect was considered to be moderate, with symptoms that were more pronounced, prolonged, or systemic than minor effects.

About 8% of the children were admitted to critical care units; 14.6% were admitted to non–critical care units.

Of 4,827 cases for which there was information about the clinical effects of the exposure and therapies used, 70% involved CNS depression, including 1.9% with “more severe CNS effects, including major CNS depression or coma,” according to the report.

Patients also experienced ataxia (7.4%), agitation (7.1%), confusion (6.1%), tremor (2%), and seizures (1.6%). Other common symptoms included tachycardia (11.4%), vomiting (9.5%), mydriasis (5.9%), and respiratory depression (3.1%).

Treatments for the exposures included intravenous fluids (20.7%), food or snacks (10.3%), and oxygen therapy (4%). Some patients also received naloxone (1.4%) or charcoal (2.1%).

“The total number of children requiring intubation during the study period was 35, or approximately 1 in 140,” the researchers reported. “Although this was a relatively rare occurrence, it is important for clinicians to be aware that life-threatening sequelae can develop and may necessitate invasive supportive care measures.”

Tempting and toxic

For toddlers, edible cannabis may be especially tempting and toxic. Edibles can “resemble common treats such as candies, chocolates, cookies, or other baked goods,” the researchers wrote. Children would not recognize, for example, that one chocolate bar might contain multiple 10-mg servings of tetrahydrocannabinol intended for adults.

Poison centers have been fielding more calls about edible cannabis use by older children, as well.

Adrienne Hughes, MD, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, recently found that many cases of intentional misuse and abuse by adolescents involve edible forms of cannabis.

“While marijuana carries a low risk for severe toxicity, it can be inebriating to the point of poor judgment, risk of falls or other injury, and occasionally a panic reaction in the novice user and unsuspecting children who accidentally ingest these products,” Dr. Hughes said in an interview.

Measures to keep edibles away from children could include changing how the products are packaged, limiting the maximum dose of drug per package, and educating the public about the risks to children, Dr. Tweet’s group wrote. They highlighted a 2019 position statement from the American College of Medical Toxicology that includes recommendations for responsible storage habits.

Dr. Hughes echoed one suggestion that is mentioned in the position statement: Parents should consider keeping their cannabis products locked up.

The researchers disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PEDIATRICS

FDA approves Wegovy (semaglutide) for obesity in teens 12 and up

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy), a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, for the additional indication of treating obesity in adolescents aged 12 years and older.

This is defined as those with an initial body mass index at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex (based on CDC growth charts). Semaglutide must be administered along with lifestyle intervention of a reduced calorie meal plan and increased physical activity.

When Wegovy was approved for use in adults with obesity in June 2021, it was labeled a “game changer.”

The new approval is based on the results of the STEP TEENS phase 3 trial of once-weekly 2.4 mg of semaglutide in adolescents 12- to <18 years old with obesity, the drug’s manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, announced in a press release.

In STEP TEENS, reported at Obesity Week 2022 in November, and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, adolescents with obesity treated with semaglutide for 68 weeks had a 16.1% reduction in BMI compared with a 0.6% increase in BMI in those receiving placebo. Both groups also received lifestyle intervention. Mean weight loss was 15.3 kg (33.7 pounds) among teens on semaglutide, while those on placebo gained 2.4 kg (5.3 pounds).

At the time, Claudia K. Fox, MD, MPH, codirector of the Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine at the University of Minnesota – who was not involved with the research – told this news organization the results were “mind-blowing ... we are getting close to bariatric surgery results” in these adolescent patients with obesity.

Semaglutide is a GLP-1 agonist, as is a related agent, also from Novo Nordisk, liraglutide (Saxenda), a daily subcutaneous injection, which was approved for use in adolescents aged 12 and older in December 2020. Wegovy is the first weekly subcutaneous injection approved for use in adolescents.

Other agents approved for obesity in those older than 12 in the United States include the combination phentermine and topiramate extended-release capsules (Qsymia) in June 2022, and orlistat (Alli). Phentermine is approved for those aged 16 and older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy), a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, for the additional indication of treating obesity in adolescents aged 12 years and older.

This is defined as those with an initial body mass index at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex (based on CDC growth charts). Semaglutide must be administered along with lifestyle intervention of a reduced calorie meal plan and increased physical activity.

When Wegovy was approved for use in adults with obesity in June 2021, it was labeled a “game changer.”

The new approval is based on the results of the STEP TEENS phase 3 trial of once-weekly 2.4 mg of semaglutide in adolescents 12- to <18 years old with obesity, the drug’s manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, announced in a press release.

In STEP TEENS, reported at Obesity Week 2022 in November, and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, adolescents with obesity treated with semaglutide for 68 weeks had a 16.1% reduction in BMI compared with a 0.6% increase in BMI in those receiving placebo. Both groups also received lifestyle intervention. Mean weight loss was 15.3 kg (33.7 pounds) among teens on semaglutide, while those on placebo gained 2.4 kg (5.3 pounds).

At the time, Claudia K. Fox, MD, MPH, codirector of the Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine at the University of Minnesota – who was not involved with the research – told this news organization the results were “mind-blowing ... we are getting close to bariatric surgery results” in these adolescent patients with obesity.

Semaglutide is a GLP-1 agonist, as is a related agent, also from Novo Nordisk, liraglutide (Saxenda), a daily subcutaneous injection, which was approved for use in adolescents aged 12 and older in December 2020. Wegovy is the first weekly subcutaneous injection approved for use in adolescents.

Other agents approved for obesity in those older than 12 in the United States include the combination phentermine and topiramate extended-release capsules (Qsymia) in June 2022, and orlistat (Alli). Phentermine is approved for those aged 16 and older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide 2.4 mg (Wegovy), a once-weekly subcutaneous injection, for the additional indication of treating obesity in adolescents aged 12 years and older.

This is defined as those with an initial body mass index at or above the 95th percentile for age and sex (based on CDC growth charts). Semaglutide must be administered along with lifestyle intervention of a reduced calorie meal plan and increased physical activity.

When Wegovy was approved for use in adults with obesity in June 2021, it was labeled a “game changer.”

The new approval is based on the results of the STEP TEENS phase 3 trial of once-weekly 2.4 mg of semaglutide in adolescents 12- to <18 years old with obesity, the drug’s manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, announced in a press release.

In STEP TEENS, reported at Obesity Week 2022 in November, and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine, adolescents with obesity treated with semaglutide for 68 weeks had a 16.1% reduction in BMI compared with a 0.6% increase in BMI in those receiving placebo. Both groups also received lifestyle intervention. Mean weight loss was 15.3 kg (33.7 pounds) among teens on semaglutide, while those on placebo gained 2.4 kg (5.3 pounds).

At the time, Claudia K. Fox, MD, MPH, codirector of the Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine at the University of Minnesota – who was not involved with the research – told this news organization the results were “mind-blowing ... we are getting close to bariatric surgery results” in these adolescent patients with obesity.

Semaglutide is a GLP-1 agonist, as is a related agent, also from Novo Nordisk, liraglutide (Saxenda), a daily subcutaneous injection, which was approved for use in adolescents aged 12 and older in December 2020. Wegovy is the first weekly subcutaneous injection approved for use in adolescents.

Other agents approved for obesity in those older than 12 in the United States include the combination phentermine and topiramate extended-release capsules (Qsymia) in June 2022, and orlistat (Alli). Phentermine is approved for those aged 16 and older.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hyperpigmented Papules on the Tongue of a Child

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13