User login

For MD-IQ use only

Impact of Initial Specimen Diversion Technique on Blood Culture Contamination Rates

Impact of Initial Specimen Diversion Technique on Blood Culture Contamination Rates

Blood cultures provide crucial evidence for diagnostic medicine, specifically aimed at identifying the presence of microbial infections in the bloodstream. Blood culturing is instrumental in diagnosing conditions such as sepsis, bacteremia, or fungemia, where the identification of the causative agent is necessary for targeted and effective treatment.1

The process involves aseptically drawing blood into sterile culture bottles, minimizing the risk of contamination with well-established guidelines. These culture bottles contain specific growth media that support the replication of microorganisms if they are present. Once the blood specimen is collected, it incubates, allowing any potential pathogens to grow. Subsequent analysis and identification of these microorganisms enable health care professionals (HCPs) to prescribe appropriate antimicrobial therapies to treat specific infections, contributing to more effective and targeted patient care.2

The reliability of blood culture results depends on minimizing contamination risk, a challenge inherent in the procedure. Contamination can lead to false-positive results, potentially misguiding treatment.3 HCPs must adhere to strict aseptic techniques during blood draws, ensuring proper skin preparation with antiseptic solutions. The use of sterile equipment and avoiding prolonged tourniquet application helps maintain the integrity of the blood specimen. Timely inoculation of blood into culture bottles and careful handling are essential to mitigate contamination risk.2 Regular training and reinforcement of proper techniques is important to uphold the accuracy of blood culture results and enhance the reliability of diagnoses and treatment decisions.3 Despite diligent contamination prevention efforts, health care systems struggle to maintain contamination rates below the 3.0% national benchmark set by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).4

Blood culture contamination is a critical concern in clinical practice; it can lead to misdiagnosis, prolonged hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and increased health care costs.5 Monitoring blood culture contamination is integral to patient safety, avoiding inappropriate and potentially harmful treatment, providing efficient care, contributing to antibiotic stewardship, supporting cost efficiency, and maintaining quality assurance and clinical research practices for public health.6

The initial specimen diversion technique (ISDT) recently emerged as a potential strategy to reduce blood culture contamination rates. This technique involves diverting a small portion of the initial blood plus the skin plug from the hollow needle away from the primary collection site before filling the culture bottles. This process minimizes skin surface contaminants, providing a cleaner blood specimen for culturing.7

The ISDT was introduced as a result of historically elevated contamination rates.8 Despite implementing various mitigation methods, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Central Texas Healthcare System (VACTHCS) has struggled to meet the national benchmark of maintaining blood culture contamination < 3.0%. The VACTHCS is a 146-bed teaching hospital with about 30,000 annual visits at the Olin E. Teague Veterans Affairs Medical Center (OETVMC) emergency department (ED). VACTHCS conducted a 16-month pilot study using 2 commercially available ISDT devices and published the findings.8

The Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022 (MilCon-VA Act) committee report prioritized the reduction of blood culture contamination to < 1% to prevent health risks and harm to veterans undergoing blood testing for the diagnosis of sepsis.9 Because it had been 5 years since OETVMC began using an ISDT in the ED, the ISDT adaptation strategy for mitigating blood culture contamination was revisited per institution policy.

The objective of this quality improvement project was to analyze retrospective data to understand the long-term impact of ISDT use on blood culture contamination rates. We hypothesized that ISDT use would contribute to efforts to maintain OETVMC ED blood culture contamination rate below the national (3.0%) and VACTHCS (2.5%) thresholds. This project assessed the progress for reducing blood culture contamination compared with the pre-ISDT era.8

METHODS

This retrospective analysis compared the blood culture contamination rates 36 months before and after the introduction of the ISDT device at the OETVMC ED. The preimplementation period was from December 2014 through November 2017 (36 months) and the postimplementation period was December 2017 through November 2020 (36 months). Data were collected from the Department of Pathology and Microbiology blood culture records of all adult patients admitted to the hospital through the ED and required blood cultures for suspicion of infection. Protected health information and VA sensitive information were not collected: all data were deidentified. A total of 18,541 blood cultures were collected 36 months preimplementation and 14,865 blood cultures were collected up to 36 months postimplementation. For comparison purposes, a similar dataset was collected from patients’ blood samples drawn by phlebotomists in the laboratory, where there had been no previous issues with overcontamination; no ISDT devices were used in the collection of these samples.

Blood Culture Contamination Variable

Blood cultures were monitored using the BACT/ALERT 3D (bioMérieux) and subsequently BACT/ALERT VIRTUO (bioMérieux), with positive bottles characterized by VITEK MS Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight technology (bioMérieux) and automated susceptibility testing (VITEK 2 [bioMérieux]).10 In an updated review of blood culture contamination, the American Society for Microbiology used the College of American Pathologists' Q-Probes quality improvement studies as a guideline for classifying contamination. A sample was determined to be contaminated if ≥ 1 of the following organisms were found in only 1 bottle in a series of blood culture sets: coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus species, α-hemolytic viridans group streptococci, Corynebacterium species, Propionibacterium acnes, and Bacillus species.11 The contamination assessment criteria remained unchanged, except for use of an ISDT device in blood culture collection at the ED.

The VACTHCS Infection Prevention Department ensured that the ISDT device was available and that ED nurses were trained annually on its use to collect blood cultures. Monthly reports of contamination were sent to the nursing supervisor for corrective action and retraining. The initial performance improvement project was slated for 16 months but was expanded to a 6-year period of retrospective data to obtain strong correlation.

Statistical Analysis

Contamination rates were recorded monthly from the hospital laboratory information management system for 36 months both before and after ISDT adoption. Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed unpaired t-test to compare monthly contamination rates for the 2 periods with GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

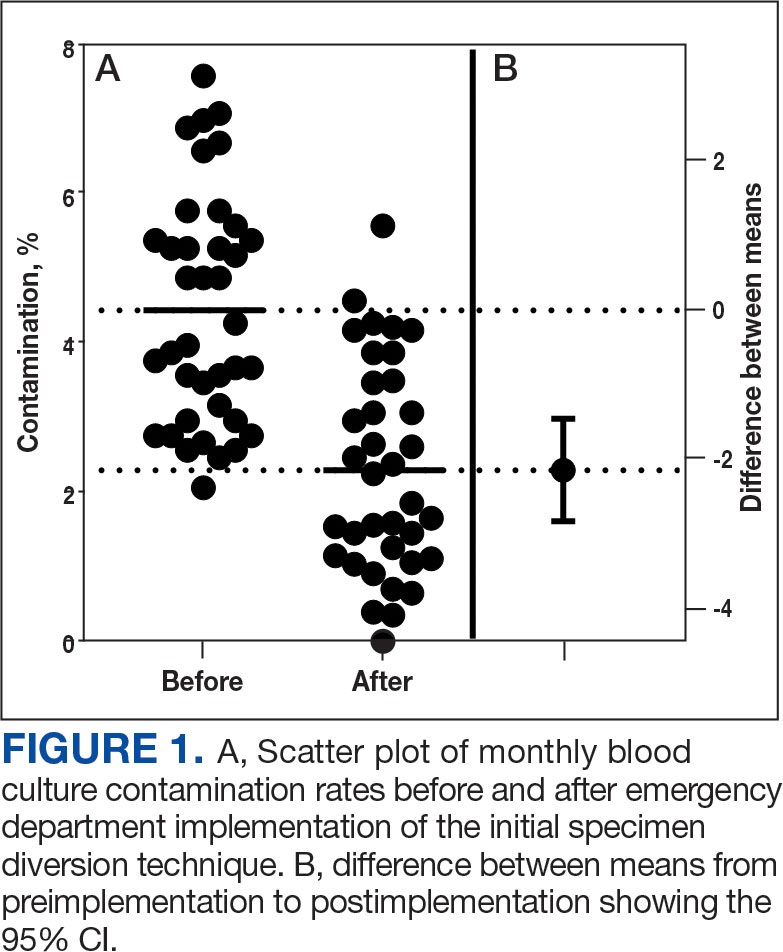

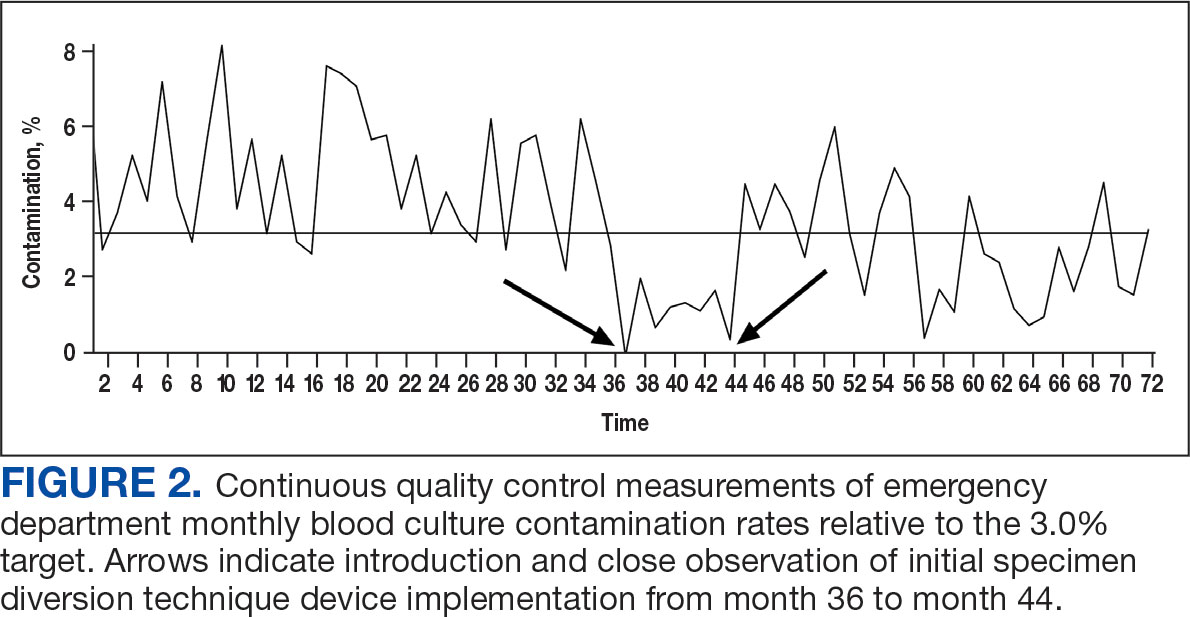

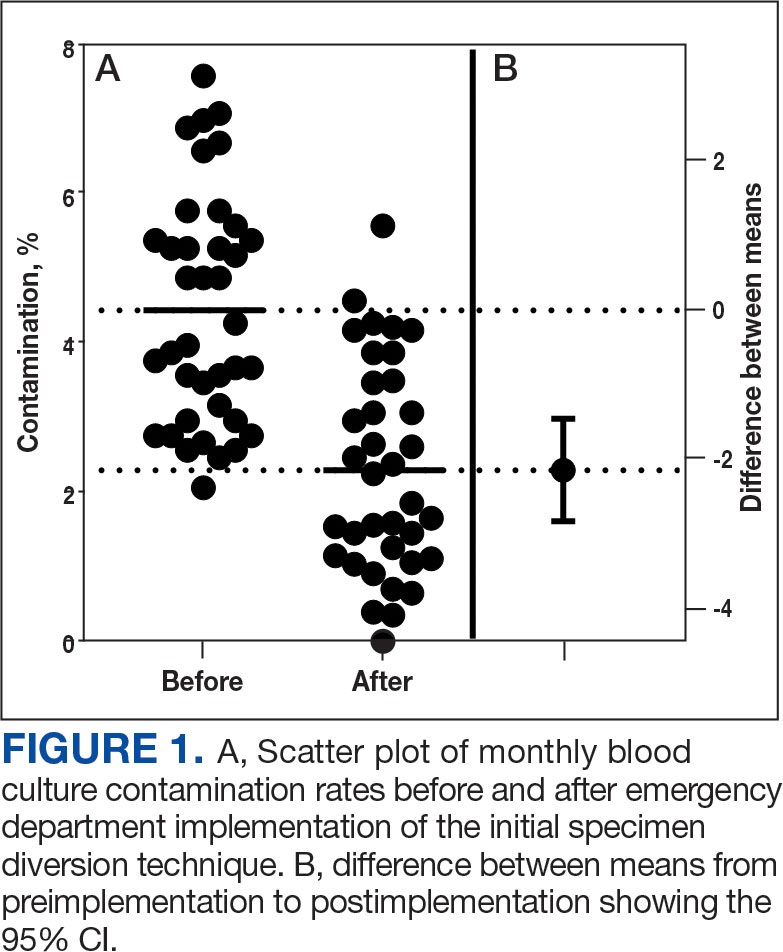

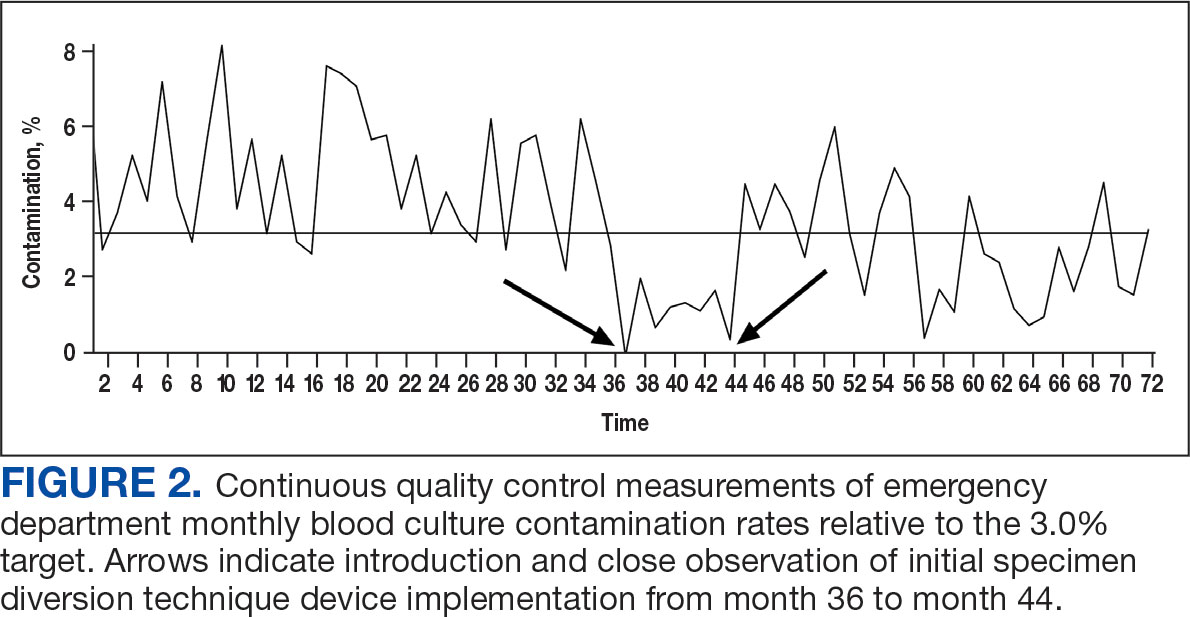

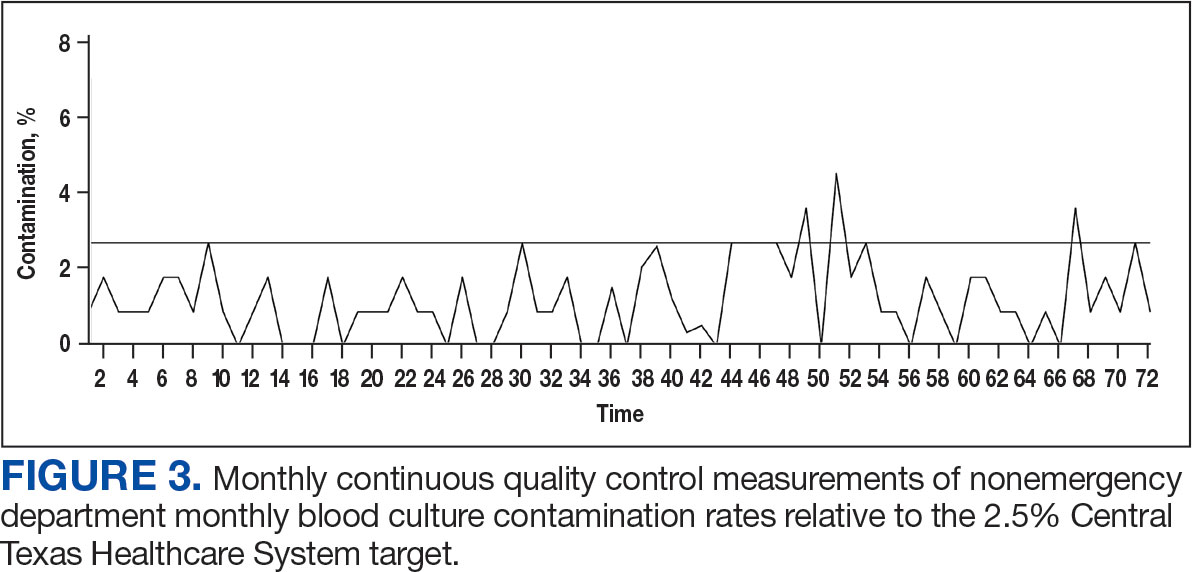

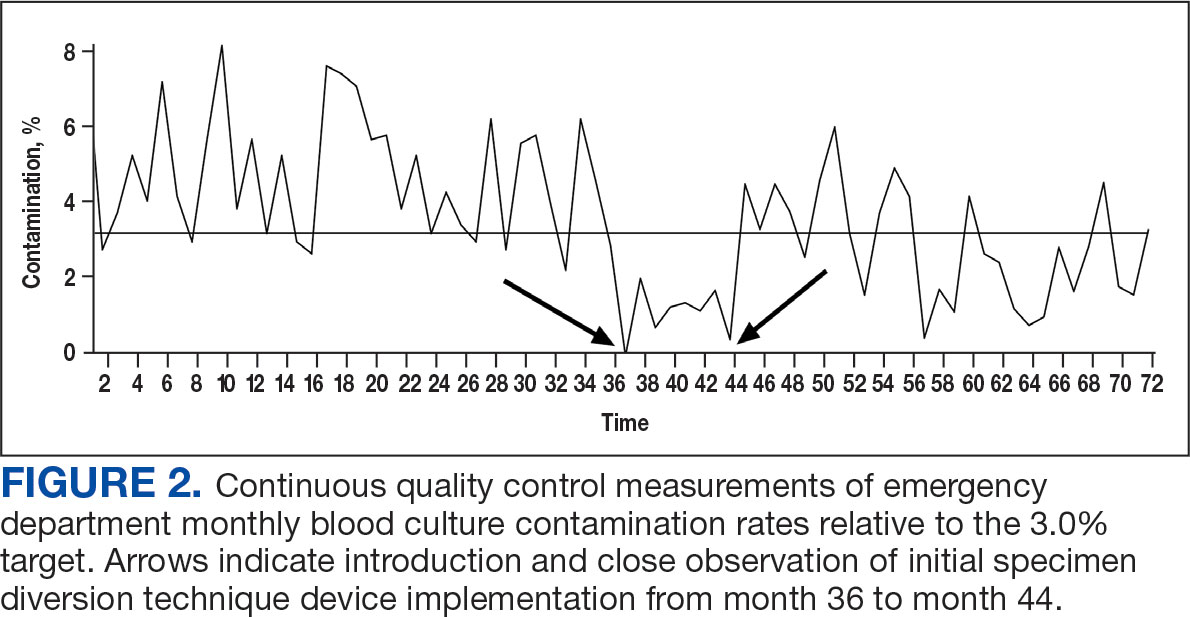

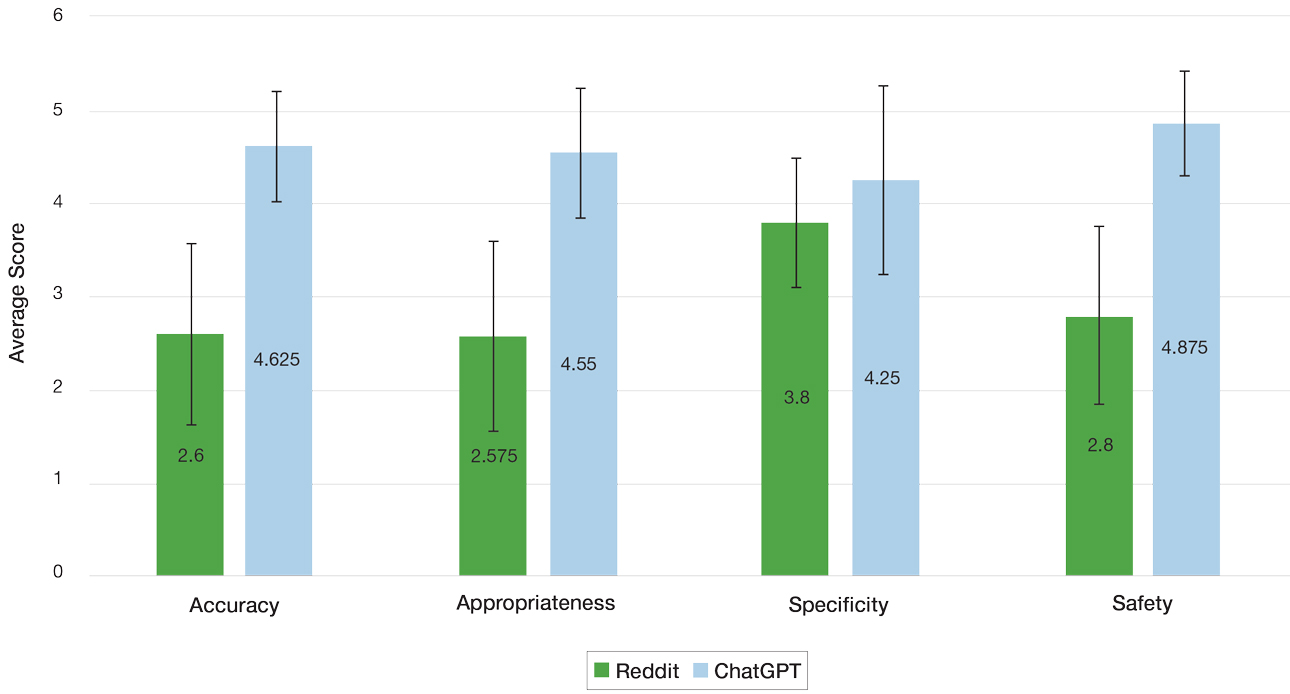

Prior to 2017, the ED reported contamination rates above the national (3.0%) and OETVMC thresholds (2.5%), with a mean of 4.5% (95% CI, 3.90-4.90).8 After ISDT implementation, the ED showed significant improvement with a reduction to mean 2.6% (95% CI, 2.10-3.20) (P < .001) (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows monthly blood culture contamination rates at the ED from December 2014 through November 2020. Month 36 (November 2017) shows a clear dip in contamination rate when the ISDT was introduced and month 37 to month 44 show remarkably low contamination rates. During this time, the institute experimented with 2 ISDT devices, and closer scrutiny may reveal this period as an outlier due to the monitoring of ISDT application, as previously reported.8

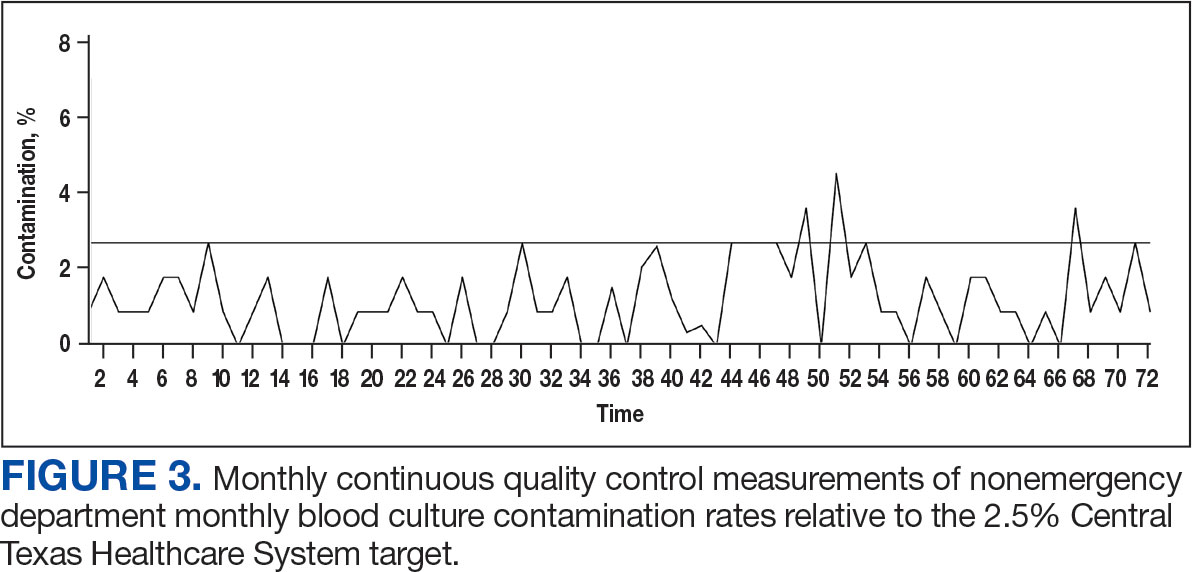

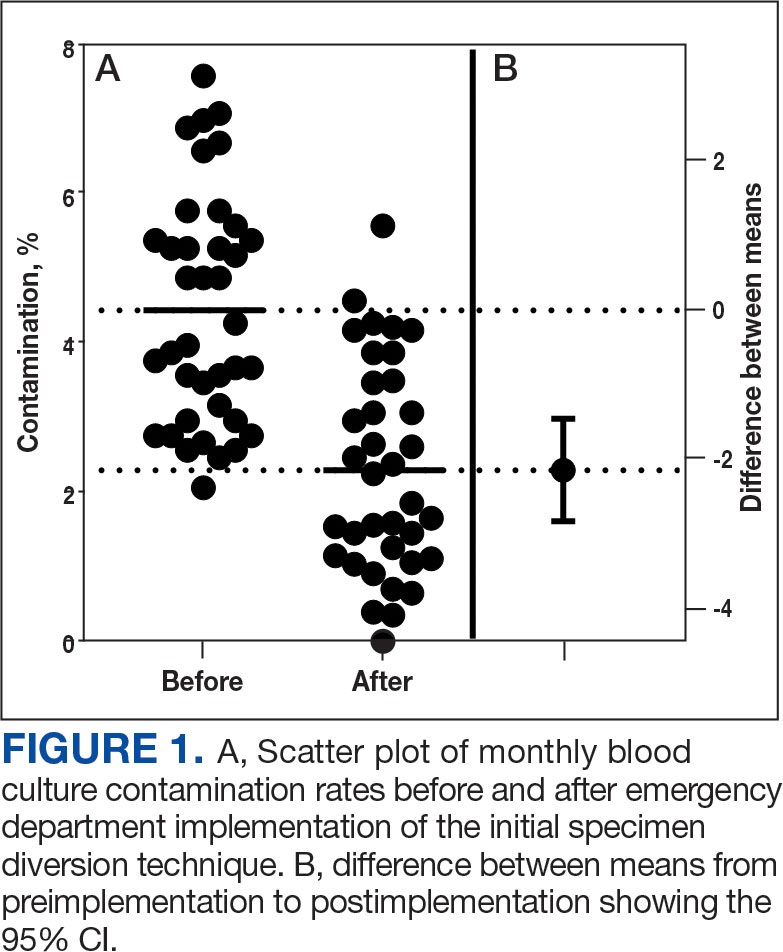

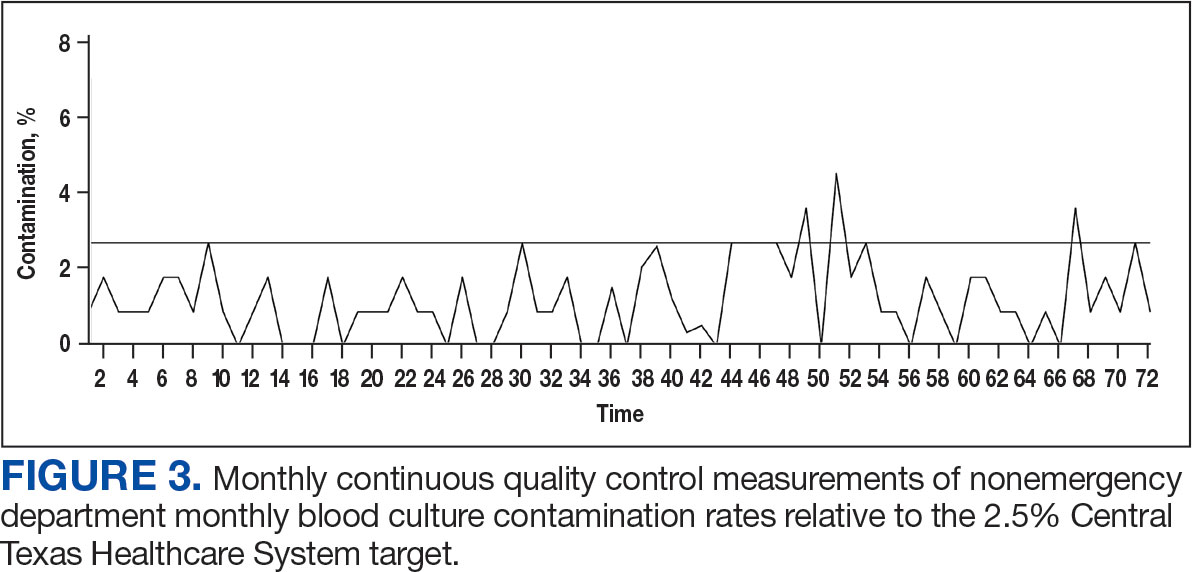

The blood culture contamination rate for samples drawn by the phlebotomists in the laboratory (excluding the ED) was calculated during the same time period (Figure 3). Non-ED contamination rates remained below 2.5% for 69 of 72 months.

DISCUSSION

The blood culture contamination rate in the OETVMC ED dropped following ISDT implementation and continued to show long-term benefits. For the 36-month period following ISDT implementation, the mean contamination rate was 2.6%, which was below the national target threshold of 3.0% and close to the OETVMC target of 2.5%. These results suggest that ISDT can have a positive impact on patient care and laboratory efficiency. Improvements in the blood contamination rates in the ED can have a positive impact on the overall hospital contamination rates.

Blood drawn by phlebotomists in the hospital laboratory infrequently had contamination rates that exceeded the 2.5% target threshold. Because the non-ED contamination rates did not change throughout the comparison period, other factors were likely not involved in the improvements seen in the ED. The decision to implement ISDT exclusively in the ED was based on its historically elevated contamination rate.8 Issues with blood culture contamination in EDs across various hospital systems are well documented and not unique to VACTHCS.12

Contamination in blood cultures can be a significant issue in the hospital. It occurs when microorganisms from the skin or environment enter the blood culture sample during collection. Moreover, it can contribute to antibiotic resistance when patients are prescribed inappropriate antibiotics. It is also important to ensure HCPs are well-trained and consistently follow standardized protocols and understand the implications of false-positive results.13

ISDT helps reduce false-positive results and is a significant advancement in the field of blood culture collection.8,14 By discarding the initial blood, it ensures that only the true bloodstream sample is cultured, leading to more accurate results.15 It also may minimize the risk of contamination-related delays in diagnosis and treatment and benefits patients and health care institutions by potentially reducing hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and health care costs.

One of the ISDT device manufacturers estimated the financial impact on OETVMC based on the pilot project.8 While this study did not calculate the direct and indirect cost savings associated with this process improvement, the manufacturer’s website suggests that VACTHCS could annually save about $486,000.16 Furthermore, implementation of ISDT may improve laboratory efficiency, as they reduce the workload associated with identifying and reporting false-positive cultures. 6 ISDT devices represent a valuable tool in the efforts to reduce blood culture contamination and its wide-ranging implications in clinical settings. While ISDT alone will not be sufficient in achieving a lower threshold (< 1%) of blood culture contamination, it can be part of a multiprong effort that optimizes best practices in the collection, handling, and management of blood cultures.

Continuous quality improvement efforts and monitoring of blood culture contamination rates can help health care institutions identify problem areas and implement necessary changes. Addressing blood culture contamination can improve patient care, reduce costs, and address antibiotic resistance.

Limitations

This study was limited by its study design, which did not use a side-by-side comparison of blood cultures from groups with and without ISDT. All blood cultures from patients in the region were processed at OETVMC, which may not be representative of non-VA EDs. Part of this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have skewed data. Additionally, hospital data were collected from a veteran population in Central Texas, and the lack of demographic diversity may not be generalizable to the greater population.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study suggest ISDT may be effective in reducing blood culture contamination rates in the high-risk ED environment, which aligns with previous research. 5,14 The ISDT may help reduce blood culture contamination rates, improving the quality of patient care and reducing health care costs. MilCon-VA mandated that all VA facilities have blood culture contamination as a metric with a goal of blood culture contamination rates < 1%.8 However, achieving this goal remains a challenge. Further research and continuous quality improvement efforts are necessary to achieve it. Consistently achieving a contamination threshold of < 1% may require minimizing human error. An automated robotic venipuncture device, as recently designed and reported, may be necessary to reduce human error in blood draw and contamination.16

- Chela HK, Vasudevan A, Rojas-Moreno C, Naqvi SH. Approach to positive blood cultures in the hospitalized patient: a review. Mo Med. 2019;116(4):313-317.

- Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, Parienti JJ, Tattevin P. How to optimize the use of blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? A state-of-the art. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:697. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00697

- Doern GV, Carroll KC, Diekema DJ, et al. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: a comprehensive update on the problem of blood culture contamination and a discussion of methods for addressing the problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00009-19. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-19

- Wilson ML, Kirn Jr TJ, Antonara S, et al. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guideline M47—Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. April 22, 2022. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m47/

- Hancock JA, Campbell S, Jones MM, Wang-Rodriguez J, VHA Microbiology SME Workgroup, Klutts JS. Development and validation of a standardized blood culture contamination definition and metric dashboard for a large health care system. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023;160(3):255-260. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqad044

- Shinozaki T, Deane RS, Mazuzan JE Jr, Hamel AJ, Hazelton D. Bacterial contamination of arterial lines. A prospective study. JAMA. 1983;249(2):223-225.

- Al Mohajer M, Lasco T. The impact of initial specimen diversion systems on blood culture contamination. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad182. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad182

- Arenas M, Boseman GM, Coppin JD, Lukey J, Jinadatha C, Navarathna DH. Asynchronous testing of 2 specimen-diversion devices to reduce blood culture contamination: a single-site product supply quality improvement project. J Emerg Nurs. 2021;47(2):256-264. e6. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2020.11.008

- Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022, HR 4355, 117th Cong (2021-2022). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4355?

- Altun O, Almuhayawi M, Lüthje P, Taha R, Ullberg M, Özenci V. Controlled evaluation of the New BacT/ Alert Virtuo blood culture system for detection and time to detection of bacteria and yeasts. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(4):1148-1151. doi:10.1128/JCM.03362-15

- Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788-802. doi:10.1128/CMR.00062-05

- Gander RM, Byrd L, DeCrescenzo M, Hirany S, Bowen M, Baughman J. Impact of blood cultures drawn by phlebotomy on contamination rates and health care costs in a hospital emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1021-1024. doi:10.1128/JCM.02162-08

- Garcia RA, Spitzer ED, Beaudry J, et al. Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremias, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central lineassociated bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1222-1237. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.030

- Callado GY, Lin V, Thottacherry E, et al. Diagnostic stewardship: a systematic review and meta-analysis of blood collection diversion devices used to reduce blood culture contamination and improve the accuracy of diagnosis in clinical settings. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(9):ofad433. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad433

- Patton RG, Schmitt T. Innovation for reducing blood culture contamination: initial specimen diversion technique. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4501-4503. doi:10.1128/JCM.00910-10

- Kurin. Clinical evidence: published Kurin studies. 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.kurin.com/studies

- Leipheimer JM, Balter ML, Chen AI, et al. First-in-human evaluation of a hand-held automated venipuncture device for rapid venous blood draws. Technology (Singap World Sci). 2019;7(3-4):98-107. doi:10.1142/S2339547819500067?

Blood cultures provide crucial evidence for diagnostic medicine, specifically aimed at identifying the presence of microbial infections in the bloodstream. Blood culturing is instrumental in diagnosing conditions such as sepsis, bacteremia, or fungemia, where the identification of the causative agent is necessary for targeted and effective treatment.1

The process involves aseptically drawing blood into sterile culture bottles, minimizing the risk of contamination with well-established guidelines. These culture bottles contain specific growth media that support the replication of microorganisms if they are present. Once the blood specimen is collected, it incubates, allowing any potential pathogens to grow. Subsequent analysis and identification of these microorganisms enable health care professionals (HCPs) to prescribe appropriate antimicrobial therapies to treat specific infections, contributing to more effective and targeted patient care.2

The reliability of blood culture results depends on minimizing contamination risk, a challenge inherent in the procedure. Contamination can lead to false-positive results, potentially misguiding treatment.3 HCPs must adhere to strict aseptic techniques during blood draws, ensuring proper skin preparation with antiseptic solutions. The use of sterile equipment and avoiding prolonged tourniquet application helps maintain the integrity of the blood specimen. Timely inoculation of blood into culture bottles and careful handling are essential to mitigate contamination risk.2 Regular training and reinforcement of proper techniques is important to uphold the accuracy of blood culture results and enhance the reliability of diagnoses and treatment decisions.3 Despite diligent contamination prevention efforts, health care systems struggle to maintain contamination rates below the 3.0% national benchmark set by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).4

Blood culture contamination is a critical concern in clinical practice; it can lead to misdiagnosis, prolonged hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and increased health care costs.5 Monitoring blood culture contamination is integral to patient safety, avoiding inappropriate and potentially harmful treatment, providing efficient care, contributing to antibiotic stewardship, supporting cost efficiency, and maintaining quality assurance and clinical research practices for public health.6

The initial specimen diversion technique (ISDT) recently emerged as a potential strategy to reduce blood culture contamination rates. This technique involves diverting a small portion of the initial blood plus the skin plug from the hollow needle away from the primary collection site before filling the culture bottles. This process minimizes skin surface contaminants, providing a cleaner blood specimen for culturing.7

The ISDT was introduced as a result of historically elevated contamination rates.8 Despite implementing various mitigation methods, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Central Texas Healthcare System (VACTHCS) has struggled to meet the national benchmark of maintaining blood culture contamination < 3.0%. The VACTHCS is a 146-bed teaching hospital with about 30,000 annual visits at the Olin E. Teague Veterans Affairs Medical Center (OETVMC) emergency department (ED). VACTHCS conducted a 16-month pilot study using 2 commercially available ISDT devices and published the findings.8

The Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022 (MilCon-VA Act) committee report prioritized the reduction of blood culture contamination to < 1% to prevent health risks and harm to veterans undergoing blood testing for the diagnosis of sepsis.9 Because it had been 5 years since OETVMC began using an ISDT in the ED, the ISDT adaptation strategy for mitigating blood culture contamination was revisited per institution policy.

The objective of this quality improvement project was to analyze retrospective data to understand the long-term impact of ISDT use on blood culture contamination rates. We hypothesized that ISDT use would contribute to efforts to maintain OETVMC ED blood culture contamination rate below the national (3.0%) and VACTHCS (2.5%) thresholds. This project assessed the progress for reducing blood culture contamination compared with the pre-ISDT era.8

METHODS

This retrospective analysis compared the blood culture contamination rates 36 months before and after the introduction of the ISDT device at the OETVMC ED. The preimplementation period was from December 2014 through November 2017 (36 months) and the postimplementation period was December 2017 through November 2020 (36 months). Data were collected from the Department of Pathology and Microbiology blood culture records of all adult patients admitted to the hospital through the ED and required blood cultures for suspicion of infection. Protected health information and VA sensitive information were not collected: all data were deidentified. A total of 18,541 blood cultures were collected 36 months preimplementation and 14,865 blood cultures were collected up to 36 months postimplementation. For comparison purposes, a similar dataset was collected from patients’ blood samples drawn by phlebotomists in the laboratory, where there had been no previous issues with overcontamination; no ISDT devices were used in the collection of these samples.

Blood Culture Contamination Variable

Blood cultures were monitored using the BACT/ALERT 3D (bioMérieux) and subsequently BACT/ALERT VIRTUO (bioMérieux), with positive bottles characterized by VITEK MS Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight technology (bioMérieux) and automated susceptibility testing (VITEK 2 [bioMérieux]).10 In an updated review of blood culture contamination, the American Society for Microbiology used the College of American Pathologists' Q-Probes quality improvement studies as a guideline for classifying contamination. A sample was determined to be contaminated if ≥ 1 of the following organisms were found in only 1 bottle in a series of blood culture sets: coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus species, α-hemolytic viridans group streptococci, Corynebacterium species, Propionibacterium acnes, and Bacillus species.11 The contamination assessment criteria remained unchanged, except for use of an ISDT device in blood culture collection at the ED.

The VACTHCS Infection Prevention Department ensured that the ISDT device was available and that ED nurses were trained annually on its use to collect blood cultures. Monthly reports of contamination were sent to the nursing supervisor for corrective action and retraining. The initial performance improvement project was slated for 16 months but was expanded to a 6-year period of retrospective data to obtain strong correlation.

Statistical Analysis

Contamination rates were recorded monthly from the hospital laboratory information management system for 36 months both before and after ISDT adoption. Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed unpaired t-test to compare monthly contamination rates for the 2 periods with GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

Prior to 2017, the ED reported contamination rates above the national (3.0%) and OETVMC thresholds (2.5%), with a mean of 4.5% (95% CI, 3.90-4.90).8 After ISDT implementation, the ED showed significant improvement with a reduction to mean 2.6% (95% CI, 2.10-3.20) (P < .001) (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows monthly blood culture contamination rates at the ED from December 2014 through November 2020. Month 36 (November 2017) shows a clear dip in contamination rate when the ISDT was introduced and month 37 to month 44 show remarkably low contamination rates. During this time, the institute experimented with 2 ISDT devices, and closer scrutiny may reveal this period as an outlier due to the monitoring of ISDT application, as previously reported.8

The blood culture contamination rate for samples drawn by the phlebotomists in the laboratory (excluding the ED) was calculated during the same time period (Figure 3). Non-ED contamination rates remained below 2.5% for 69 of 72 months.

DISCUSSION

The blood culture contamination rate in the OETVMC ED dropped following ISDT implementation and continued to show long-term benefits. For the 36-month period following ISDT implementation, the mean contamination rate was 2.6%, which was below the national target threshold of 3.0% and close to the OETVMC target of 2.5%. These results suggest that ISDT can have a positive impact on patient care and laboratory efficiency. Improvements in the blood contamination rates in the ED can have a positive impact on the overall hospital contamination rates.

Blood drawn by phlebotomists in the hospital laboratory infrequently had contamination rates that exceeded the 2.5% target threshold. Because the non-ED contamination rates did not change throughout the comparison period, other factors were likely not involved in the improvements seen in the ED. The decision to implement ISDT exclusively in the ED was based on its historically elevated contamination rate.8 Issues with blood culture contamination in EDs across various hospital systems are well documented and not unique to VACTHCS.12

Contamination in blood cultures can be a significant issue in the hospital. It occurs when microorganisms from the skin or environment enter the blood culture sample during collection. Moreover, it can contribute to antibiotic resistance when patients are prescribed inappropriate antibiotics. It is also important to ensure HCPs are well-trained and consistently follow standardized protocols and understand the implications of false-positive results.13

ISDT helps reduce false-positive results and is a significant advancement in the field of blood culture collection.8,14 By discarding the initial blood, it ensures that only the true bloodstream sample is cultured, leading to more accurate results.15 It also may minimize the risk of contamination-related delays in diagnosis and treatment and benefits patients and health care institutions by potentially reducing hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and health care costs.

One of the ISDT device manufacturers estimated the financial impact on OETVMC based on the pilot project.8 While this study did not calculate the direct and indirect cost savings associated with this process improvement, the manufacturer’s website suggests that VACTHCS could annually save about $486,000.16 Furthermore, implementation of ISDT may improve laboratory efficiency, as they reduce the workload associated with identifying and reporting false-positive cultures. 6 ISDT devices represent a valuable tool in the efforts to reduce blood culture contamination and its wide-ranging implications in clinical settings. While ISDT alone will not be sufficient in achieving a lower threshold (< 1%) of blood culture contamination, it can be part of a multiprong effort that optimizes best practices in the collection, handling, and management of blood cultures.

Continuous quality improvement efforts and monitoring of blood culture contamination rates can help health care institutions identify problem areas and implement necessary changes. Addressing blood culture contamination can improve patient care, reduce costs, and address antibiotic resistance.

Limitations

This study was limited by its study design, which did not use a side-by-side comparison of blood cultures from groups with and without ISDT. All blood cultures from patients in the region were processed at OETVMC, which may not be representative of non-VA EDs. Part of this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have skewed data. Additionally, hospital data were collected from a veteran population in Central Texas, and the lack of demographic diversity may not be generalizable to the greater population.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study suggest ISDT may be effective in reducing blood culture contamination rates in the high-risk ED environment, which aligns with previous research. 5,14 The ISDT may help reduce blood culture contamination rates, improving the quality of patient care and reducing health care costs. MilCon-VA mandated that all VA facilities have blood culture contamination as a metric with a goal of blood culture contamination rates < 1%.8 However, achieving this goal remains a challenge. Further research and continuous quality improvement efforts are necessary to achieve it. Consistently achieving a contamination threshold of < 1% may require minimizing human error. An automated robotic venipuncture device, as recently designed and reported, may be necessary to reduce human error in blood draw and contamination.16

Blood cultures provide crucial evidence for diagnostic medicine, specifically aimed at identifying the presence of microbial infections in the bloodstream. Blood culturing is instrumental in diagnosing conditions such as sepsis, bacteremia, or fungemia, where the identification of the causative agent is necessary for targeted and effective treatment.1

The process involves aseptically drawing blood into sterile culture bottles, minimizing the risk of contamination with well-established guidelines. These culture bottles contain specific growth media that support the replication of microorganisms if they are present. Once the blood specimen is collected, it incubates, allowing any potential pathogens to grow. Subsequent analysis and identification of these microorganisms enable health care professionals (HCPs) to prescribe appropriate antimicrobial therapies to treat specific infections, contributing to more effective and targeted patient care.2

The reliability of blood culture results depends on minimizing contamination risk, a challenge inherent in the procedure. Contamination can lead to false-positive results, potentially misguiding treatment.3 HCPs must adhere to strict aseptic techniques during blood draws, ensuring proper skin preparation with antiseptic solutions. The use of sterile equipment and avoiding prolonged tourniquet application helps maintain the integrity of the blood specimen. Timely inoculation of blood into culture bottles and careful handling are essential to mitigate contamination risk.2 Regular training and reinforcement of proper techniques is important to uphold the accuracy of blood culture results and enhance the reliability of diagnoses and treatment decisions.3 Despite diligent contamination prevention efforts, health care systems struggle to maintain contamination rates below the 3.0% national benchmark set by the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).4

Blood culture contamination is a critical concern in clinical practice; it can lead to misdiagnosis, prolonged hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and increased health care costs.5 Monitoring blood culture contamination is integral to patient safety, avoiding inappropriate and potentially harmful treatment, providing efficient care, contributing to antibiotic stewardship, supporting cost efficiency, and maintaining quality assurance and clinical research practices for public health.6

The initial specimen diversion technique (ISDT) recently emerged as a potential strategy to reduce blood culture contamination rates. This technique involves diverting a small portion of the initial blood plus the skin plug from the hollow needle away from the primary collection site before filling the culture bottles. This process minimizes skin surface contaminants, providing a cleaner blood specimen for culturing.7

The ISDT was introduced as a result of historically elevated contamination rates.8 Despite implementing various mitigation methods, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Central Texas Healthcare System (VACTHCS) has struggled to meet the national benchmark of maintaining blood culture contamination < 3.0%. The VACTHCS is a 146-bed teaching hospital with about 30,000 annual visits at the Olin E. Teague Veterans Affairs Medical Center (OETVMC) emergency department (ED). VACTHCS conducted a 16-month pilot study using 2 commercially available ISDT devices and published the findings.8

The Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022 (MilCon-VA Act) committee report prioritized the reduction of blood culture contamination to < 1% to prevent health risks and harm to veterans undergoing blood testing for the diagnosis of sepsis.9 Because it had been 5 years since OETVMC began using an ISDT in the ED, the ISDT adaptation strategy for mitigating blood culture contamination was revisited per institution policy.

The objective of this quality improvement project was to analyze retrospective data to understand the long-term impact of ISDT use on blood culture contamination rates. We hypothesized that ISDT use would contribute to efforts to maintain OETVMC ED blood culture contamination rate below the national (3.0%) and VACTHCS (2.5%) thresholds. This project assessed the progress for reducing blood culture contamination compared with the pre-ISDT era.8

METHODS

This retrospective analysis compared the blood culture contamination rates 36 months before and after the introduction of the ISDT device at the OETVMC ED. The preimplementation period was from December 2014 through November 2017 (36 months) and the postimplementation period was December 2017 through November 2020 (36 months). Data were collected from the Department of Pathology and Microbiology blood culture records of all adult patients admitted to the hospital through the ED and required blood cultures for suspicion of infection. Protected health information and VA sensitive information were not collected: all data were deidentified. A total of 18,541 blood cultures were collected 36 months preimplementation and 14,865 blood cultures were collected up to 36 months postimplementation. For comparison purposes, a similar dataset was collected from patients’ blood samples drawn by phlebotomists in the laboratory, where there had been no previous issues with overcontamination; no ISDT devices were used in the collection of these samples.

Blood Culture Contamination Variable

Blood cultures were monitored using the BACT/ALERT 3D (bioMérieux) and subsequently BACT/ALERT VIRTUO (bioMérieux), with positive bottles characterized by VITEK MS Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-of-Flight technology (bioMérieux) and automated susceptibility testing (VITEK 2 [bioMérieux]).10 In an updated review of blood culture contamination, the American Society for Microbiology used the College of American Pathologists' Q-Probes quality improvement studies as a guideline for classifying contamination. A sample was determined to be contaminated if ≥ 1 of the following organisms were found in only 1 bottle in a series of blood culture sets: coagulase-negative staphylococci, Micrococcus species, α-hemolytic viridans group streptococci, Corynebacterium species, Propionibacterium acnes, and Bacillus species.11 The contamination assessment criteria remained unchanged, except for use of an ISDT device in blood culture collection at the ED.

The VACTHCS Infection Prevention Department ensured that the ISDT device was available and that ED nurses were trained annually on its use to collect blood cultures. Monthly reports of contamination were sent to the nursing supervisor for corrective action and retraining. The initial performance improvement project was slated for 16 months but was expanded to a 6-year period of retrospective data to obtain strong correlation.

Statistical Analysis

Contamination rates were recorded monthly from the hospital laboratory information management system for 36 months both before and after ISDT adoption. Statistical analysis was performed using a 2-tailed unpaired t-test to compare monthly contamination rates for the 2 periods with GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

Prior to 2017, the ED reported contamination rates above the national (3.0%) and OETVMC thresholds (2.5%), with a mean of 4.5% (95% CI, 3.90-4.90).8 After ISDT implementation, the ED showed significant improvement with a reduction to mean 2.6% (95% CI, 2.10-3.20) (P < .001) (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows monthly blood culture contamination rates at the ED from December 2014 through November 2020. Month 36 (November 2017) shows a clear dip in contamination rate when the ISDT was introduced and month 37 to month 44 show remarkably low contamination rates. During this time, the institute experimented with 2 ISDT devices, and closer scrutiny may reveal this period as an outlier due to the monitoring of ISDT application, as previously reported.8

The blood culture contamination rate for samples drawn by the phlebotomists in the laboratory (excluding the ED) was calculated during the same time period (Figure 3). Non-ED contamination rates remained below 2.5% for 69 of 72 months.

DISCUSSION

The blood culture contamination rate in the OETVMC ED dropped following ISDT implementation and continued to show long-term benefits. For the 36-month period following ISDT implementation, the mean contamination rate was 2.6%, which was below the national target threshold of 3.0% and close to the OETVMC target of 2.5%. These results suggest that ISDT can have a positive impact on patient care and laboratory efficiency. Improvements in the blood contamination rates in the ED can have a positive impact on the overall hospital contamination rates.

Blood drawn by phlebotomists in the hospital laboratory infrequently had contamination rates that exceeded the 2.5% target threshold. Because the non-ED contamination rates did not change throughout the comparison period, other factors were likely not involved in the improvements seen in the ED. The decision to implement ISDT exclusively in the ED was based on its historically elevated contamination rate.8 Issues with blood culture contamination in EDs across various hospital systems are well documented and not unique to VACTHCS.12

Contamination in blood cultures can be a significant issue in the hospital. It occurs when microorganisms from the skin or environment enter the blood culture sample during collection. Moreover, it can contribute to antibiotic resistance when patients are prescribed inappropriate antibiotics. It is also important to ensure HCPs are well-trained and consistently follow standardized protocols and understand the implications of false-positive results.13

ISDT helps reduce false-positive results and is a significant advancement in the field of blood culture collection.8,14 By discarding the initial blood, it ensures that only the true bloodstream sample is cultured, leading to more accurate results.15 It also may minimize the risk of contamination-related delays in diagnosis and treatment and benefits patients and health care institutions by potentially reducing hospital stays, unnecessary antibiotic use, and health care costs.

One of the ISDT device manufacturers estimated the financial impact on OETVMC based on the pilot project.8 While this study did not calculate the direct and indirect cost savings associated with this process improvement, the manufacturer’s website suggests that VACTHCS could annually save about $486,000.16 Furthermore, implementation of ISDT may improve laboratory efficiency, as they reduce the workload associated with identifying and reporting false-positive cultures. 6 ISDT devices represent a valuable tool in the efforts to reduce blood culture contamination and its wide-ranging implications in clinical settings. While ISDT alone will not be sufficient in achieving a lower threshold (< 1%) of blood culture contamination, it can be part of a multiprong effort that optimizes best practices in the collection, handling, and management of blood cultures.

Continuous quality improvement efforts and monitoring of blood culture contamination rates can help health care institutions identify problem areas and implement necessary changes. Addressing blood culture contamination can improve patient care, reduce costs, and address antibiotic resistance.

Limitations

This study was limited by its study design, which did not use a side-by-side comparison of blood cultures from groups with and without ISDT. All blood cultures from patients in the region were processed at OETVMC, which may not be representative of non-VA EDs. Part of this study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have skewed data. Additionally, hospital data were collected from a veteran population in Central Texas, and the lack of demographic diversity may not be generalizable to the greater population.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study suggest ISDT may be effective in reducing blood culture contamination rates in the high-risk ED environment, which aligns with previous research. 5,14 The ISDT may help reduce blood culture contamination rates, improving the quality of patient care and reducing health care costs. MilCon-VA mandated that all VA facilities have blood culture contamination as a metric with a goal of blood culture contamination rates < 1%.8 However, achieving this goal remains a challenge. Further research and continuous quality improvement efforts are necessary to achieve it. Consistently achieving a contamination threshold of < 1% may require minimizing human error. An automated robotic venipuncture device, as recently designed and reported, may be necessary to reduce human error in blood draw and contamination.16

- Chela HK, Vasudevan A, Rojas-Moreno C, Naqvi SH. Approach to positive blood cultures in the hospitalized patient: a review. Mo Med. 2019;116(4):313-317.

- Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, Parienti JJ, Tattevin P. How to optimize the use of blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? A state-of-the art. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:697. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00697

- Doern GV, Carroll KC, Diekema DJ, et al. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: a comprehensive update on the problem of blood culture contamination and a discussion of methods for addressing the problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00009-19. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-19

- Wilson ML, Kirn Jr TJ, Antonara S, et al. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guideline M47—Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. April 22, 2022. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m47/

- Hancock JA, Campbell S, Jones MM, Wang-Rodriguez J, VHA Microbiology SME Workgroup, Klutts JS. Development and validation of a standardized blood culture contamination definition and metric dashboard for a large health care system. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023;160(3):255-260. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqad044

- Shinozaki T, Deane RS, Mazuzan JE Jr, Hamel AJ, Hazelton D. Bacterial contamination of arterial lines. A prospective study. JAMA. 1983;249(2):223-225.

- Al Mohajer M, Lasco T. The impact of initial specimen diversion systems on blood culture contamination. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad182. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad182

- Arenas M, Boseman GM, Coppin JD, Lukey J, Jinadatha C, Navarathna DH. Asynchronous testing of 2 specimen-diversion devices to reduce blood culture contamination: a single-site product supply quality improvement project. J Emerg Nurs. 2021;47(2):256-264. e6. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2020.11.008

- Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022, HR 4355, 117th Cong (2021-2022). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4355?

- Altun O, Almuhayawi M, Lüthje P, Taha R, Ullberg M, Özenci V. Controlled evaluation of the New BacT/ Alert Virtuo blood culture system for detection and time to detection of bacteria and yeasts. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(4):1148-1151. doi:10.1128/JCM.03362-15

- Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788-802. doi:10.1128/CMR.00062-05

- Gander RM, Byrd L, DeCrescenzo M, Hirany S, Bowen M, Baughman J. Impact of blood cultures drawn by phlebotomy on contamination rates and health care costs in a hospital emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1021-1024. doi:10.1128/JCM.02162-08

- Garcia RA, Spitzer ED, Beaudry J, et al. Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremias, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central lineassociated bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1222-1237. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.030

- Callado GY, Lin V, Thottacherry E, et al. Diagnostic stewardship: a systematic review and meta-analysis of blood collection diversion devices used to reduce blood culture contamination and improve the accuracy of diagnosis in clinical settings. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(9):ofad433. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad433

- Patton RG, Schmitt T. Innovation for reducing blood culture contamination: initial specimen diversion technique. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4501-4503. doi:10.1128/JCM.00910-10

- Kurin. Clinical evidence: published Kurin studies. 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.kurin.com/studies

- Leipheimer JM, Balter ML, Chen AI, et al. First-in-human evaluation of a hand-held automated venipuncture device for rapid venous blood draws. Technology (Singap World Sci). 2019;7(3-4):98-107. doi:10.1142/S2339547819500067?

- Chela HK, Vasudevan A, Rojas-Moreno C, Naqvi SH. Approach to positive blood cultures in the hospitalized patient: a review. Mo Med. 2019;116(4):313-317.

- Lamy B, Dargère S, Arendrup MC, Parienti JJ, Tattevin P. How to optimize the use of blood cultures for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections? A state-of-the art. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:697. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00697

- Doern GV, Carroll KC, Diekema DJ, et al. Practical guidance for clinical microbiology laboratories: a comprehensive update on the problem of blood culture contamination and a discussion of methods for addressing the problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00009-19. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-19

- Wilson ML, Kirn Jr TJ, Antonara S, et al. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guideline M47—Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. April 22, 2022. Accessed May 21, 2025. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m47/

- Hancock JA, Campbell S, Jones MM, Wang-Rodriguez J, VHA Microbiology SME Workgroup, Klutts JS. Development and validation of a standardized blood culture contamination definition and metric dashboard for a large health care system. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023;160(3):255-260. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqad044

- Shinozaki T, Deane RS, Mazuzan JE Jr, Hamel AJ, Hazelton D. Bacterial contamination of arterial lines. A prospective study. JAMA. 1983;249(2):223-225.

- Al Mohajer M, Lasco T. The impact of initial specimen diversion systems on blood culture contamination. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10:ofad182. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad182

- Arenas M, Boseman GM, Coppin JD, Lukey J, Jinadatha C, Navarathna DH. Asynchronous testing of 2 specimen-diversion devices to reduce blood culture contamination: a single-site product supply quality improvement project. J Emerg Nurs. 2021;47(2):256-264. e6. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2020.11.008

- Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2022, HR 4355, 117th Cong (2021-2022). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4355?

- Altun O, Almuhayawi M, Lüthje P, Taha R, Ullberg M, Özenci V. Controlled evaluation of the New BacT/ Alert Virtuo blood culture system for detection and time to detection of bacteria and yeasts. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(4):1148-1151. doi:10.1128/JCM.03362-15

- Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788-802. doi:10.1128/CMR.00062-05

- Gander RM, Byrd L, DeCrescenzo M, Hirany S, Bowen M, Baughman J. Impact of blood cultures drawn by phlebotomy on contamination rates and health care costs in a hospital emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1021-1024. doi:10.1128/JCM.02162-08

- Garcia RA, Spitzer ED, Beaudry J, et al. Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremias, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central lineassociated bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1222-1237. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.030

- Callado GY, Lin V, Thottacherry E, et al. Diagnostic stewardship: a systematic review and meta-analysis of blood collection diversion devices used to reduce blood culture contamination and improve the accuracy of diagnosis in clinical settings. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(9):ofad433. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofad433

- Patton RG, Schmitt T. Innovation for reducing blood culture contamination: initial specimen diversion technique. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4501-4503. doi:10.1128/JCM.00910-10

- Kurin. Clinical evidence: published Kurin studies. 2024. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.kurin.com/studies

- Leipheimer JM, Balter ML, Chen AI, et al. First-in-human evaluation of a hand-held automated venipuncture device for rapid venous blood draws. Technology (Singap World Sci). 2019;7(3-4):98-107. doi:10.1142/S2339547819500067?

Impact of Initial Specimen Diversion Technique on Blood Culture Contamination Rates

Impact of Initial Specimen Diversion Technique on Blood Culture Contamination Rates

What About Stolen Valor is Actually Illegal?

What About Stolen Valor is Actually Illegal?

Memorial Day is the most solemn of all American military commemorations. It is the day when we honor those who sacrificed their lives so that their fellow citizens could flourish in freedom. At 3 PM, a grateful nation is called to observe 2 minutes of silence in remembrance of the heroes who died in battle or of the wounds they sustained in combat. Communities across the country will carry out ceremonies, lining national cemeteries with flags, holding patriotic parades, and conducting spiritual observances.1

Sadly, almost as long as there has been a United States, there has been a parallel practice dishonoring the uniform and deceiving veterans and the public alike known as stolen valor. Stolen valor is a persistent, yet strange, psychological behavior: individuals who never served in the US Armed Forces claim they have done heroic deeds for which they often sustained serious injuries in the line of duty and almost always won medals for their heroism.2 This editorial will trace the US legal history of stolen valor cases to provide the background for next month’s editorial examining its clinical and ethical aspects.

While many cases of stolen valor do not receive media attention, the experience of Sarah Cavanaugh, a former VA social worker who claimed to be a marine veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, was the subject of the Deep Cover podcast series.3 Cavanaugh had claimed that an improvised explosive device blew up her Humvee, crushing her hip. Still she somehow was able to help her fellow Marines and earned the Bronze Star among other decorations for her heroism. That was not the only lie Cavanaugh told: she also told her friends and wife that she had advanced lung cancer due to burn pit exposure. In line with the best-worst of those who have stolen valor, her mastery of manipulation enabled her to become the commander of a local Veterans of Foreign Wars post. Using stolen identities and fraudulent documents, Cavanaugh was able to purloin veteran benefits, donated leave from other VA employees and money, and stole goods and services from various charitable organizations whose mission was to help wounded veterans and those struggling to adjust to civilian life. Before law enforcement unraveled her sordid tale, she misappropriated hundreds of thousands of dollars in VA benefits and donations and exploited dozens of generous veterans and compassionate civilians.4

Cavanaugh’s story was so sordidly compelling that I kept saying out loud to myself (and my spouse), “This has to be illegal.” The truth about stolen valor law is far more ambivalent and frustrating than I had anticipated or wanted. The first insult to my sense of justice was that lying about military service is not in itself illegal: you can pad your military resume with unearned decorations or impress a future partner or employer with your combat exploits without much fear of legal repercussions. The legal history of attempting to make stealing valor a crime has almost as many twists and turns as the fallacious narratives of military imposters and illustrates the uniquely American experiment in balancing freedom and fairness.

The Stolen Valor Act of 2005 made it a federal misdemeanor to wear, manufacture, or sell military decorations, or medals (Cavanaugh bought her medals online) without legal authorization. It also made it a crime to falsely represent oneself as having been the recipient of a decoration, medical, or service badge that Congress or the Armed Forces authorized. There were even stiffer penalties if the medal was a Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, US Air Force or US Navy Cross, or Purple Heart. Punishments include fines and imprisonment. The stated legislative purpose was to prohibit fraud that devalued military awards and the dignity of those who legitimately earned them.5

Next comes a distinctly American reaction to the initial Congressional attempt to protect the legacy of those who served—a lawsuit. Xavier Alvarez was an official on a California district water board claimed to be a 25-year veteran of the US Marine Corps wounded in combat and received the Congressional Medal of Honor. The Federal Bureau of Investigation exposed the lie and instead of the nation’s highest honor, Alvarez was the first to be convicted under the Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Alvarez appealed the decision, ironically claiming the law violated his free speech rights. The case landed in the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Stolen Valor Act did indeed violate the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. The majority opinion found the Act as passed was too encompassing of all speech and needed to target only cases in which false statements resulted in actual harm.6

The Stolen Valor Act of 2013 amends the criminal code regarding fraudulent claims about military service to include those who don’t only lie but also profit from it, as Cavanaugh did. The revised act specifically focuses on individuals who claim to have earned military honors for the intended purpose of obtaining money, property, or any other tangible benefit.7

Despite the complicated nature of Stolen Valor Law, it did prevail in Cavanaugh’s case. A US District Court Judge in Rhode Island found her guilty of stolen valor in all its permutations, along with identity theft of other veterans’ military and medical records and fraud in obtaining benefits and services intended for real veterans. Cavanaugh was sentenced to 70 months in federal prison, 3 years of supervised release, ordered to pay $284,796.82 in restitution, and to restore 261 hours of donated leave to the federal government, charitable organizations, and good Samaritans she duped and swindled.8

The revised law under which Cavanaugh was punished lasted 10 years until another classically American ethical concern—privacy—motivated additional legislative effort. A 2023/2024 US House of Representatives proposal to amend the Stolen Valor Act would have strengthened the privacy protections afforded military records. It would have required the information to only be accessed with the permission of the individual who served or their family or through a Freedom of Information Act request. This would make the kind of journalistic and law enforcement investigations that eventually caught Cavanaugh in her lies far more laborious for false valor hunters while at the same time preventing unscrupulous inquiries into service members’ personal information. Advocates for free speech and defenders of military honor are both lobbying Congress; as of this writing the legislation has not been passed.9

As we close part 1 of this review of stolen valor, we return to Memorial Day. This day provides the somber recognition that without the brave men and women of integrity who died in defense of a democracy that promotes the political activity of its citizens, we would not even be able to have this debate over justice, freedom, and truth.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The difference between Veterans Day and Memorial Day. October 30, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/125549/difference-between-veterans-day-memorial-day/

- Home of Heroes. Stolen valor. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://homeofheroes.com/stolen-valor

- Halpern J. Deep cover: the truth about Sarah. May 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/deep-cover

- Stillwell B. The latest season of the ‘deep cover’ podcast dives into one of the biggest stolen valor cases ever. Military. com. May 22, 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https:// www.military.com/off-duty/2025/05/22/latest-season-of-deep-cover-podcast-dives-one-of-biggest-stolen-valor-cases-ever.html

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Pub L No: 109-437. 120 Stat 3266

- Alvarez v United States. 567 US 2012.

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2013. 18 USC § 704(b)

- US Attorney’s Office, District of Rhode Island. Rhode Island woman sentenced to federal prison for falsifying military service; false use of military medals; identify theft, and fraudulently collecting more than $250,000, in veteran benefits and charitable contributions. March 14, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.justice.gov/usao-ri/pr/rhode-island-woman-sentenced-federal-prison-falsifying-military-service-false-use

- Armed Forces Benefit Association. Stolen Valor Act: all you need to know. February 21, 2024. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.afba.com/military-life/active-duty-and-veterans/stolen-valor-act-all-you-need-to-know/

Memorial Day is the most solemn of all American military commemorations. It is the day when we honor those who sacrificed their lives so that their fellow citizens could flourish in freedom. At 3 PM, a grateful nation is called to observe 2 minutes of silence in remembrance of the heroes who died in battle or of the wounds they sustained in combat. Communities across the country will carry out ceremonies, lining national cemeteries with flags, holding patriotic parades, and conducting spiritual observances.1

Sadly, almost as long as there has been a United States, there has been a parallel practice dishonoring the uniform and deceiving veterans and the public alike known as stolen valor. Stolen valor is a persistent, yet strange, psychological behavior: individuals who never served in the US Armed Forces claim they have done heroic deeds for which they often sustained serious injuries in the line of duty and almost always won medals for their heroism.2 This editorial will trace the US legal history of stolen valor cases to provide the background for next month’s editorial examining its clinical and ethical aspects.

While many cases of stolen valor do not receive media attention, the experience of Sarah Cavanaugh, a former VA social worker who claimed to be a marine veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, was the subject of the Deep Cover podcast series.3 Cavanaugh had claimed that an improvised explosive device blew up her Humvee, crushing her hip. Still she somehow was able to help her fellow Marines and earned the Bronze Star among other decorations for her heroism. That was not the only lie Cavanaugh told: she also told her friends and wife that she had advanced lung cancer due to burn pit exposure. In line with the best-worst of those who have stolen valor, her mastery of manipulation enabled her to become the commander of a local Veterans of Foreign Wars post. Using stolen identities and fraudulent documents, Cavanaugh was able to purloin veteran benefits, donated leave from other VA employees and money, and stole goods and services from various charitable organizations whose mission was to help wounded veterans and those struggling to adjust to civilian life. Before law enforcement unraveled her sordid tale, she misappropriated hundreds of thousands of dollars in VA benefits and donations and exploited dozens of generous veterans and compassionate civilians.4

Cavanaugh’s story was so sordidly compelling that I kept saying out loud to myself (and my spouse), “This has to be illegal.” The truth about stolen valor law is far more ambivalent and frustrating than I had anticipated or wanted. The first insult to my sense of justice was that lying about military service is not in itself illegal: you can pad your military resume with unearned decorations or impress a future partner or employer with your combat exploits without much fear of legal repercussions. The legal history of attempting to make stealing valor a crime has almost as many twists and turns as the fallacious narratives of military imposters and illustrates the uniquely American experiment in balancing freedom and fairness.

The Stolen Valor Act of 2005 made it a federal misdemeanor to wear, manufacture, or sell military decorations, or medals (Cavanaugh bought her medals online) without legal authorization. It also made it a crime to falsely represent oneself as having been the recipient of a decoration, medical, or service badge that Congress or the Armed Forces authorized. There were even stiffer penalties if the medal was a Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, US Air Force or US Navy Cross, or Purple Heart. Punishments include fines and imprisonment. The stated legislative purpose was to prohibit fraud that devalued military awards and the dignity of those who legitimately earned them.5

Next comes a distinctly American reaction to the initial Congressional attempt to protect the legacy of those who served—a lawsuit. Xavier Alvarez was an official on a California district water board claimed to be a 25-year veteran of the US Marine Corps wounded in combat and received the Congressional Medal of Honor. The Federal Bureau of Investigation exposed the lie and instead of the nation’s highest honor, Alvarez was the first to be convicted under the Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Alvarez appealed the decision, ironically claiming the law violated his free speech rights. The case landed in the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Stolen Valor Act did indeed violate the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. The majority opinion found the Act as passed was too encompassing of all speech and needed to target only cases in which false statements resulted in actual harm.6

The Stolen Valor Act of 2013 amends the criminal code regarding fraudulent claims about military service to include those who don’t only lie but also profit from it, as Cavanaugh did. The revised act specifically focuses on individuals who claim to have earned military honors for the intended purpose of obtaining money, property, or any other tangible benefit.7

Despite the complicated nature of Stolen Valor Law, it did prevail in Cavanaugh’s case. A US District Court Judge in Rhode Island found her guilty of stolen valor in all its permutations, along with identity theft of other veterans’ military and medical records and fraud in obtaining benefits and services intended for real veterans. Cavanaugh was sentenced to 70 months in federal prison, 3 years of supervised release, ordered to pay $284,796.82 in restitution, and to restore 261 hours of donated leave to the federal government, charitable organizations, and good Samaritans she duped and swindled.8

The revised law under which Cavanaugh was punished lasted 10 years until another classically American ethical concern—privacy—motivated additional legislative effort. A 2023/2024 US House of Representatives proposal to amend the Stolen Valor Act would have strengthened the privacy protections afforded military records. It would have required the information to only be accessed with the permission of the individual who served or their family or through a Freedom of Information Act request. This would make the kind of journalistic and law enforcement investigations that eventually caught Cavanaugh in her lies far more laborious for false valor hunters while at the same time preventing unscrupulous inquiries into service members’ personal information. Advocates for free speech and defenders of military honor are both lobbying Congress; as of this writing the legislation has not been passed.9

As we close part 1 of this review of stolen valor, we return to Memorial Day. This day provides the somber recognition that without the brave men and women of integrity who died in defense of a democracy that promotes the political activity of its citizens, we would not even be able to have this debate over justice, freedom, and truth.

Memorial Day is the most solemn of all American military commemorations. It is the day when we honor those who sacrificed their lives so that their fellow citizens could flourish in freedom. At 3 PM, a grateful nation is called to observe 2 minutes of silence in remembrance of the heroes who died in battle or of the wounds they sustained in combat. Communities across the country will carry out ceremonies, lining national cemeteries with flags, holding patriotic parades, and conducting spiritual observances.1

Sadly, almost as long as there has been a United States, there has been a parallel practice dishonoring the uniform and deceiving veterans and the public alike known as stolen valor. Stolen valor is a persistent, yet strange, psychological behavior: individuals who never served in the US Armed Forces claim they have done heroic deeds for which they often sustained serious injuries in the line of duty and almost always won medals for their heroism.2 This editorial will trace the US legal history of stolen valor cases to provide the background for next month’s editorial examining its clinical and ethical aspects.

While many cases of stolen valor do not receive media attention, the experience of Sarah Cavanaugh, a former VA social worker who claimed to be a marine veteran who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, was the subject of the Deep Cover podcast series.3 Cavanaugh had claimed that an improvised explosive device blew up her Humvee, crushing her hip. Still she somehow was able to help her fellow Marines and earned the Bronze Star among other decorations for her heroism. That was not the only lie Cavanaugh told: she also told her friends and wife that she had advanced lung cancer due to burn pit exposure. In line with the best-worst of those who have stolen valor, her mastery of manipulation enabled her to become the commander of a local Veterans of Foreign Wars post. Using stolen identities and fraudulent documents, Cavanaugh was able to purloin veteran benefits, donated leave from other VA employees and money, and stole goods and services from various charitable organizations whose mission was to help wounded veterans and those struggling to adjust to civilian life. Before law enforcement unraveled her sordid tale, she misappropriated hundreds of thousands of dollars in VA benefits and donations and exploited dozens of generous veterans and compassionate civilians.4

Cavanaugh’s story was so sordidly compelling that I kept saying out loud to myself (and my spouse), “This has to be illegal.” The truth about stolen valor law is far more ambivalent and frustrating than I had anticipated or wanted. The first insult to my sense of justice was that lying about military service is not in itself illegal: you can pad your military resume with unearned decorations or impress a future partner or employer with your combat exploits without much fear of legal repercussions. The legal history of attempting to make stealing valor a crime has almost as many twists and turns as the fallacious narratives of military imposters and illustrates the uniquely American experiment in balancing freedom and fairness.

The Stolen Valor Act of 2005 made it a federal misdemeanor to wear, manufacture, or sell military decorations, or medals (Cavanaugh bought her medals online) without legal authorization. It also made it a crime to falsely represent oneself as having been the recipient of a decoration, medical, or service badge that Congress or the Armed Forces authorized. There were even stiffer penalties if the medal was a Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, US Air Force or US Navy Cross, or Purple Heart. Punishments include fines and imprisonment. The stated legislative purpose was to prohibit fraud that devalued military awards and the dignity of those who legitimately earned them.5

Next comes a distinctly American reaction to the initial Congressional attempt to protect the legacy of those who served—a lawsuit. Xavier Alvarez was an official on a California district water board claimed to be a 25-year veteran of the US Marine Corps wounded in combat and received the Congressional Medal of Honor. The Federal Bureau of Investigation exposed the lie and instead of the nation’s highest honor, Alvarez was the first to be convicted under the Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Alvarez appealed the decision, ironically claiming the law violated his free speech rights. The case landed in the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Stolen Valor Act did indeed violate the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment. The majority opinion found the Act as passed was too encompassing of all speech and needed to target only cases in which false statements resulted in actual harm.6

The Stolen Valor Act of 2013 amends the criminal code regarding fraudulent claims about military service to include those who don’t only lie but also profit from it, as Cavanaugh did. The revised act specifically focuses on individuals who claim to have earned military honors for the intended purpose of obtaining money, property, or any other tangible benefit.7

Despite the complicated nature of Stolen Valor Law, it did prevail in Cavanaugh’s case. A US District Court Judge in Rhode Island found her guilty of stolen valor in all its permutations, along with identity theft of other veterans’ military and medical records and fraud in obtaining benefits and services intended for real veterans. Cavanaugh was sentenced to 70 months in federal prison, 3 years of supervised release, ordered to pay $284,796.82 in restitution, and to restore 261 hours of donated leave to the federal government, charitable organizations, and good Samaritans she duped and swindled.8

The revised law under which Cavanaugh was punished lasted 10 years until another classically American ethical concern—privacy—motivated additional legislative effort. A 2023/2024 US House of Representatives proposal to amend the Stolen Valor Act would have strengthened the privacy protections afforded military records. It would have required the information to only be accessed with the permission of the individual who served or their family or through a Freedom of Information Act request. This would make the kind of journalistic and law enforcement investigations that eventually caught Cavanaugh in her lies far more laborious for false valor hunters while at the same time preventing unscrupulous inquiries into service members’ personal information. Advocates for free speech and defenders of military honor are both lobbying Congress; as of this writing the legislation has not been passed.9

As we close part 1 of this review of stolen valor, we return to Memorial Day. This day provides the somber recognition that without the brave men and women of integrity who died in defense of a democracy that promotes the political activity of its citizens, we would not even be able to have this debate over justice, freedom, and truth.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The difference between Veterans Day and Memorial Day. October 30, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/125549/difference-between-veterans-day-memorial-day/

- Home of Heroes. Stolen valor. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://homeofheroes.com/stolen-valor

- Halpern J. Deep cover: the truth about Sarah. May 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/deep-cover

- Stillwell B. The latest season of the ‘deep cover’ podcast dives into one of the biggest stolen valor cases ever. Military. com. May 22, 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https:// www.military.com/off-duty/2025/05/22/latest-season-of-deep-cover-podcast-dives-one-of-biggest-stolen-valor-cases-ever.html

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Pub L No: 109-437. 120 Stat 3266

- Alvarez v United States. 567 US 2012.

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2013. 18 USC § 704(b)

- US Attorney’s Office, District of Rhode Island. Rhode Island woman sentenced to federal prison for falsifying military service; false use of military medals; identify theft, and fraudulently collecting more than $250,000, in veteran benefits and charitable contributions. March 14, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.justice.gov/usao-ri/pr/rhode-island-woman-sentenced-federal-prison-falsifying-military-service-false-use

- Armed Forces Benefit Association. Stolen Valor Act: all you need to know. February 21, 2024. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.afba.com/military-life/active-duty-and-veterans/stolen-valor-act-all-you-need-to-know/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. The difference between Veterans Day and Memorial Day. October 30, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/125549/difference-between-veterans-day-memorial-day/

- Home of Heroes. Stolen valor. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://homeofheroes.com/stolen-valor

- Halpern J. Deep cover: the truth about Sarah. May 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/deep-cover

- Stillwell B. The latest season of the ‘deep cover’ podcast dives into one of the biggest stolen valor cases ever. Military. com. May 22, 2025. Accessed May 27, 2025. https:// www.military.com/off-duty/2025/05/22/latest-season-of-deep-cover-podcast-dives-one-of-biggest-stolen-valor-cases-ever.html

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2005. Pub L No: 109-437. 120 Stat 3266

- Alvarez v United States. 567 US 2012.

- The Stolen Valor Act of 2013. 18 USC § 704(b)

- US Attorney’s Office, District of Rhode Island. Rhode Island woman sentenced to federal prison for falsifying military service; false use of military medals; identify theft, and fraudulently collecting more than $250,000, in veteran benefits and charitable contributions. March 14, 2023. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.justice.gov/usao-ri/pr/rhode-island-woman-sentenced-federal-prison-falsifying-military-service-false-use

- Armed Forces Benefit Association. Stolen Valor Act: all you need to know. February 21, 2024. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://www.afba.com/military-life/active-duty-and-veterans/stolen-valor-act-all-you-need-to-know/

What About Stolen Valor is Actually Illegal?

What About Stolen Valor is Actually Illegal?

Immune Responses and Health Disparities Warrant Scabies Vaccine Development

Immune Responses and Health Disparities Warrant Scabies Vaccine Development

The scabies mite, originally known as Acarus scabiei,1 now is considered an arthropod of the class Arachnida, order Astigmata, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Scabies mites are able to adhere to the surface of human skin.3 The mites burrow and lay eggs in the top layer of the epidermis; most patients have 10 to 15 mites.3 The patient’s immune system incites an allergic reaction to the mite protein and feces in the skin, causing itching and rash.4

Scabies is common in indigenous populations and in low-income areas of developing countries.5 It is most prevalent in Africa, South America, Australia, and Southeast Asia, in part due to poverty, poor nutritional status, homelessness, and inadequate hygiene.2 In 2009, the World Health Organization declared scabies a neglected skin disease2; however, in 2010, 1.5 million disability adjusted life-years were attributed to scabies,6 and it is estimated that 200 million people worldwide have scabies at any given time. Children and elderly individuals in resource-poor communities are the most at risk. In fact, 5% to 50% of children in low-income areas have scabies.4

The purpose of this article is to provide background on scabies and its effect on the human immune system. We also discuss manipulation of the immune response for the purposes of creating a potential scabies vaccine.

Life Cycle and Transmission

The life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei consists of 4 stages. The first is the egg. As female scabies mites burrow under the skin, they lay 2 to 3 ovular eggs per day.3 The second stage is the larva. When the egg hatches, the larva has 3 pairs of legs and travels to the surface of the skin where it burrows into the stratum corneum, creating short, nearly invisible burrows called molting pouches. After 3 to 4 days, the larva molts into a nymph, which is the third stage. The nymph has 4 pairs of legs and will continue to grow before molting into an adult, which is the fourth stage. Both the larva and nymph may be found in hair follicles or molting pouches. The fourth stage is the adult, which is round and saclike and does not have eyes. Adult females are 0.30 mm to 0.45 mm long and 0.25 mm to 0.35 mm wide, which is half the size of adult males.3 On warm skin, the female mite can crawl at a rate of 2.5 cm per minute.7