User login

Correction: Hypertension guidelines

In Aleyadeh W, Hutt-Centeno E, Ahmed HM, Shah NP. Hypertension guidelines: treat patients, not numbers. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(1):47–56. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18027, on page 50, the following statement was incorrect: “In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a relaxed systolic blood pressure target, ie, below 150 mm Hg, for adults over age 60, but a tighter goal of less than 130 mm Hg for the same age group if they have transient ischemic attack, stroke, or high cardiovascular risk.9” In fact, the ACP and AAFP recommended a tighter goal of less than 140 mm Hg for this higher-risk group. This has been corrected online.

In Aleyadeh W, Hutt-Centeno E, Ahmed HM, Shah NP. Hypertension guidelines: treat patients, not numbers. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(1):47–56. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18027, on page 50, the following statement was incorrect: “In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a relaxed systolic blood pressure target, ie, below 150 mm Hg, for adults over age 60, but a tighter goal of less than 130 mm Hg for the same age group if they have transient ischemic attack, stroke, or high cardiovascular risk.9” In fact, the ACP and AAFP recommended a tighter goal of less than 140 mm Hg for this higher-risk group. This has been corrected online.

In Aleyadeh W, Hutt-Centeno E, Ahmed HM, Shah NP. Hypertension guidelines: treat patients, not numbers. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(1):47–56. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18027, on page 50, the following statement was incorrect: “In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a relaxed systolic blood pressure target, ie, below 150 mm Hg, for adults over age 60, but a tighter goal of less than 130 mm Hg for the same age group if they have transient ischemic attack, stroke, or high cardiovascular risk.9” In fact, the ACP and AAFP recommended a tighter goal of less than 140 mm Hg for this higher-risk group. This has been corrected online.

Conservatism spreads in prostate cancer

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

, the United States now has more than 100 measles cases for the year, e-cigarette use reverses progress in reducing teens’ tobacco use, and consider adopting the MESA 10-year coronary heart disease risk calculator.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Watchful waiting up for low-risk prostate cancer

Conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer is up recently, in line with clinical practice guideline changes, while in high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy has increased despite a lack of new high-level evidence supporting the approach, according to researchers.

Active surveillance or watchful waiting surpassed both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy to become the most common management strategy in low-risk disease over the 2010-2015 time period, according to their analysis of a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Meanwhile, radical prostatectomy use declined in low-risk patients, but increased in those with higher-risk disease at the expense of radiotherapy, said authors of the analysis, led by Brandon A. Mahal, MD, and Paul L. Nguyen, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

“Although increasing use of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk disease has been supported by high-level evidence and guidelines since 2010, shifting management patterns toward more radical prostatectomy in higher-risk disease and away from radiotherapy does not coincide with any new level 1 evidence or guideline changes,” Dr. Mahal, Dr. Nguyen, and coauthors said in JAMA.

The analysis included 164,760 men with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer between 2010 and 2015 in the SEER Prostate Active Surveillance/Watchful Waiting database. Of that group, 12.7% were managed by active surveillance or watchful waiting, while 41.5% underwent radiotherapy and 45.8% had a radical prostatectomy.

For men with low-risk disease, active surveillance or watchful waiting increased from just 14.5% in 2010 to 42.1% in 2015, investigators found. Radical prostatectomy decreased from 47.4% to 31.3% over that 5-year period, while radiotherapy likewise decreased from 38.0% to 26.6% (P less than .001 for all three trends).

By contrast, in men with high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy increased from 38.0% to 42.8%, while radiotherapy decreased from 60.1% to 55.0% (P less than .001 for both trends), and use of active surveillance remained low and steady at 1.9% in 2010 to 2.2% in 2015.

Intermediate-risk disease saw a significant increase in active surveillance, from 5.8% to 9.6% over the time period, with commensurate decreases in both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, according to the report.

While low-risk prostate cancer was traditionally managed with radical prostatectomy, national clinical practice guidelines starting in 2010 began recommending conservative management with active surveillance or watchful waiting, researchers noted in their report.

These epidemiologic data don’t provide any insights on clinical outcomes related to the management changes, investigators acknowledged. They said further study is needed to determine the “downstream effects” of increased active surveillance or watchful waiting in low-risk prostate cancer.

Dr. Mahal reported no conflicts of interest, while Dr. Nguyen provided disclosures related to Ferring, Augmenix, Bayer, Janssen, Astellas, Dendreon, Genome DX, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Nanobiotix, Janssen, and Astellas. Coauthors had disclosures relate to Janssen, Blue Earth, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Mahal BA et al. JAMA. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19941.

Conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer is up recently, in line with clinical practice guideline changes, while in high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy has increased despite a lack of new high-level evidence supporting the approach, according to researchers.

Active surveillance or watchful waiting surpassed both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy to become the most common management strategy in low-risk disease over the 2010-2015 time period, according to their analysis of a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Meanwhile, radical prostatectomy use declined in low-risk patients, but increased in those with higher-risk disease at the expense of radiotherapy, said authors of the analysis, led by Brandon A. Mahal, MD, and Paul L. Nguyen, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

“Although increasing use of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk disease has been supported by high-level evidence and guidelines since 2010, shifting management patterns toward more radical prostatectomy in higher-risk disease and away from radiotherapy does not coincide with any new level 1 evidence or guideline changes,” Dr. Mahal, Dr. Nguyen, and coauthors said in JAMA.

The analysis included 164,760 men with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer between 2010 and 2015 in the SEER Prostate Active Surveillance/Watchful Waiting database. Of that group, 12.7% were managed by active surveillance or watchful waiting, while 41.5% underwent radiotherapy and 45.8% had a radical prostatectomy.

For men with low-risk disease, active surveillance or watchful waiting increased from just 14.5% in 2010 to 42.1% in 2015, investigators found. Radical prostatectomy decreased from 47.4% to 31.3% over that 5-year period, while radiotherapy likewise decreased from 38.0% to 26.6% (P less than .001 for all three trends).

By contrast, in men with high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy increased from 38.0% to 42.8%, while radiotherapy decreased from 60.1% to 55.0% (P less than .001 for both trends), and use of active surveillance remained low and steady at 1.9% in 2010 to 2.2% in 2015.

Intermediate-risk disease saw a significant increase in active surveillance, from 5.8% to 9.6% over the time period, with commensurate decreases in both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, according to the report.

While low-risk prostate cancer was traditionally managed with radical prostatectomy, national clinical practice guidelines starting in 2010 began recommending conservative management with active surveillance or watchful waiting, researchers noted in their report.

These epidemiologic data don’t provide any insights on clinical outcomes related to the management changes, investigators acknowledged. They said further study is needed to determine the “downstream effects” of increased active surveillance or watchful waiting in low-risk prostate cancer.

Dr. Mahal reported no conflicts of interest, while Dr. Nguyen provided disclosures related to Ferring, Augmenix, Bayer, Janssen, Astellas, Dendreon, Genome DX, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Nanobiotix, Janssen, and Astellas. Coauthors had disclosures relate to Janssen, Blue Earth, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Mahal BA et al. JAMA. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19941.

Conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer is up recently, in line with clinical practice guideline changes, while in high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy has increased despite a lack of new high-level evidence supporting the approach, according to researchers.

Active surveillance or watchful waiting surpassed both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy to become the most common management strategy in low-risk disease over the 2010-2015 time period, according to their analysis of a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database.

Meanwhile, radical prostatectomy use declined in low-risk patients, but increased in those with higher-risk disease at the expense of radiotherapy, said authors of the analysis, led by Brandon A. Mahal, MD, and Paul L. Nguyen, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston.

“Although increasing use of active surveillance or watchful waiting for low-risk disease has been supported by high-level evidence and guidelines since 2010, shifting management patterns toward more radical prostatectomy in higher-risk disease and away from radiotherapy does not coincide with any new level 1 evidence or guideline changes,” Dr. Mahal, Dr. Nguyen, and coauthors said in JAMA.

The analysis included 164,760 men with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer between 2010 and 2015 in the SEER Prostate Active Surveillance/Watchful Waiting database. Of that group, 12.7% were managed by active surveillance or watchful waiting, while 41.5% underwent radiotherapy and 45.8% had a radical prostatectomy.

For men with low-risk disease, active surveillance or watchful waiting increased from just 14.5% in 2010 to 42.1% in 2015, investigators found. Radical prostatectomy decreased from 47.4% to 31.3% over that 5-year period, while radiotherapy likewise decreased from 38.0% to 26.6% (P less than .001 for all three trends).

By contrast, in men with high-risk disease, use of radical prostatectomy increased from 38.0% to 42.8%, while radiotherapy decreased from 60.1% to 55.0% (P less than .001 for both trends), and use of active surveillance remained low and steady at 1.9% in 2010 to 2.2% in 2015.

Intermediate-risk disease saw a significant increase in active surveillance, from 5.8% to 9.6% over the time period, with commensurate decreases in both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, according to the report.

While low-risk prostate cancer was traditionally managed with radical prostatectomy, national clinical practice guidelines starting in 2010 began recommending conservative management with active surveillance or watchful waiting, researchers noted in their report.

These epidemiologic data don’t provide any insights on clinical outcomes related to the management changes, investigators acknowledged. They said further study is needed to determine the “downstream effects” of increased active surveillance or watchful waiting in low-risk prostate cancer.

Dr. Mahal reported no conflicts of interest, while Dr. Nguyen provided disclosures related to Ferring, Augmenix, Bayer, Janssen, Astellas, Dendreon, Genome DX, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Nanobiotix, Janssen, and Astellas. Coauthors had disclosures relate to Janssen, Blue Earth, and the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Mahal BA et al. JAMA. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19941.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Conservative management for low-risk localized prostate cancer is up, in line with guidelines, while radical prostatectomy use has increased in high-risk disease despite a lack of new high-level evidence to support that approach.

Major finding: In men with low-risk disease, active surveillance or watchful waiting increased from 14.5% in 2010 to 42.1% in 2015, while in high-risk disease, radical prostatectomy increased from 38.0% to 42.8%

Study details: Analysis including 164,760 men with a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer between 2010 and 2015 in the SEER Prostate Active Surveillance/Watchful Waiting database.

Disclosures: Study authors reported disclosures related to Ferring, Augmenix, Bayer, Janssen, Astellas, Dendreon, Genome DX, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Nanobiotix, Janssen, Astellas, and the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Mahal BA et al. JAMA. 2019 Feb 11. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19941.

ADT harms likely limited to men with CV comorbidities

WASHINGTON – The cardiovascular effects of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for men with advanced prostate cancer are less severe than once feared, but there is evidence to suggest that men with preexisting heart failure or a history of myocardial infarction could be at excess risk for death from cardiovascular causes when they receive ADT, according to a leading prostate cancer expert.

“I think there are concerns about potential cardiovascular harm of ADT, and I think this has reduced ADT use, despite the fact that we know for most men it improves overall survival,” said Paul Nguyen, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“In fact, when we looked recently at men with high-risk prostate cancer, this is a group where overall survival is improved by 50% if they get ADT – so it cuts the risk of death in half – but it turns out that nearly a quarter of those patients are not receiving ADT. I think that the concern about cardiovascular harm and the confusion as to where that data stands is a lot of what’s driving that right now,” he said at the American College of Cardiology’s Advancing the Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient meeting.

Randomized trial data

Dr. Nguyen noted that the evidence suggesting that ADT can increase the risk of death from cardiovascular causes came largely from three major studies:

- A 2006 study of 73,196 Medicare enrollees aged 66 or older, which found that ADT with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist was possibly associated with increased risk of incident diabetes and cardiovascular disease (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 20;24[27]:4448-56.).

- A 2007 analysis of data from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CAPSURE) database on 3,262 men treated with radical prostatectomy and 1,630 men treated with radiation or cryotherapy for localized prostate cancer, which found that among those 65 and older the 5-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death was 5.5% for patients who received ADT, vs. 2% for those who did not (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Oct 17;99[20]:1516-24).

- A 2007 study of 1,372 men in three randomized trials of radiation therapy with or without androgen suppression therapy up to 8 months in duration, which found that men 65 and older who received 6 months of androgen suppression had significantly shorter times to fatal MIs than did men who did not receive the therapy (J Clin Oncol. 2007;25[17]:2420-5).

These studies, combined with observational data, led to a 2010 consensus statement from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association, with endorsement from the American Society for Radiation Oncology, which stated that “there may be a relation between ADT and cardiovascular events and death.”

Also in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration required new labeling on GnRH agonists warning of “increased risk of diabetes and certain cardiovascular diseases (heart attack, sudden cardiac death, stroke).”

Not unanimous

Two other large randomized studies (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 1;26[4]:585-91 and J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27[1]:92-9) and two retrospective studies (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jul 20;27[21]:3452-8 and J Clin Oncol. 2011 Sep 10;29[26]3510-16) found no excess risk of cardiovascular disease from ADT, Dr. Nguyen said, prompting him and his colleagues to see whether they could get a better estimate of the actual risk.

They did so through a 2011 meta-analysis (JAMA. 2011;306[21]:2359-66) of data on 4,141 patients from eight randomized trials. They found that among patients with unfavorable-risk prostate cancer, ADT was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death, but was associated with lower risks for both prostate-specific and all-cause mortality.

Subpopulations may still be at risk

Dr. Nguyen said that the principal finding of the meta-analysis, while reassuring, “doesn’t let ADT off the hook for metabolic events, diabetes which we know happens, and the possibility of nonfatal cardiac events.”

He noted that while ADT was not associated with cardiovascular disease in clinical trials, observational studies showed significantly increased risk for fatal or non-fatal MI.

One possible explanation for the difference is that observational studies included nonfatal MI, while randomized trials looked only at cardiovascular deaths. It’s also possible that ADT causes harm primarily in men with preexisting comorbidities, who are often excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Evidence from a 2009 study (JAMA. 2009 Aug 26;302[8]:866-73) showed that among men with clinical stage T1 to T3 noninvasive, nonmetastatic prostate cancer, neoadjuvant hormonal therapy with both a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist and a nonsteroidal antiandrogen was associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality for those with a history of coronary artery disease–induced heart failure, but not for men with either no comorbidities or only a single comorbidity such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes.

Clinical considerations

The decision to treat men with prostate cancer with ADT is therefore a balancing act, Dr. Nguyen said.

“As the risk of prostate cancer death goes up, the benefit of ADT goes up. However, as the comorbidity level goes up, the potential cardiovascular harm of ADT goes up,” he said.

For patients at the extreme ends of each continuum, such as a patient with high-risk prostate cancer and no cardiovascular comorbidities or a patient with low-risk cancer but multiple CV risk factors, the decision to give or withhold ADT is relatively simple, he said.

But for patients in between, such as a man with intermediate-risk cancer and one risk factor or a man with high risk disease with multiple comorbidities, the decision is far more complex.

“This where I think the dialogue with the cardiologist really needs to come into this decision,” he said.

Evidence to support the decision comes from retrospective studies suggesting that even men with high-risk prostate cancer have poorer overall survival with ADT if they have a history of heart failure or MI.

For patients with low-risk cancer and diabetes, ADT is associated with worse overall survival, but ADT does not cause additional harm to men with intermediate- to high-risk prostate cancer who have concomitant diabetes, Dr. Nguyen said.

“My view is that ADT has not been shown to increase cardiovascular death in randomized trials, so I think that for the vast majority of patients it probably does not increase cardiovascular deaths. But I think there could very well be a vulnerable 5% of patients who might have an excess risk of cardiovascular death, and I think we have to be careful, but we still have to balance it out against their risks for prostate cancer death,” he said.

Dr. Nguyen reported consulting fees/honoraria from Astellas, Augmenix, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Dendreon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GenomeDx, Janssen, and Nanobiotix.

WASHINGTON – The cardiovascular effects of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for men with advanced prostate cancer are less severe than once feared, but there is evidence to suggest that men with preexisting heart failure or a history of myocardial infarction could be at excess risk for death from cardiovascular causes when they receive ADT, according to a leading prostate cancer expert.

“I think there are concerns about potential cardiovascular harm of ADT, and I think this has reduced ADT use, despite the fact that we know for most men it improves overall survival,” said Paul Nguyen, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“In fact, when we looked recently at men with high-risk prostate cancer, this is a group where overall survival is improved by 50% if they get ADT – so it cuts the risk of death in half – but it turns out that nearly a quarter of those patients are not receiving ADT. I think that the concern about cardiovascular harm and the confusion as to where that data stands is a lot of what’s driving that right now,” he said at the American College of Cardiology’s Advancing the Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient meeting.

Randomized trial data

Dr. Nguyen noted that the evidence suggesting that ADT can increase the risk of death from cardiovascular causes came largely from three major studies:

- A 2006 study of 73,196 Medicare enrollees aged 66 or older, which found that ADT with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist was possibly associated with increased risk of incident diabetes and cardiovascular disease (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 20;24[27]:4448-56.).

- A 2007 analysis of data from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CAPSURE) database on 3,262 men treated with radical prostatectomy and 1,630 men treated with radiation or cryotherapy for localized prostate cancer, which found that among those 65 and older the 5-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death was 5.5% for patients who received ADT, vs. 2% for those who did not (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Oct 17;99[20]:1516-24).

- A 2007 study of 1,372 men in three randomized trials of radiation therapy with or without androgen suppression therapy up to 8 months in duration, which found that men 65 and older who received 6 months of androgen suppression had significantly shorter times to fatal MIs than did men who did not receive the therapy (J Clin Oncol. 2007;25[17]:2420-5).

These studies, combined with observational data, led to a 2010 consensus statement from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association, with endorsement from the American Society for Radiation Oncology, which stated that “there may be a relation between ADT and cardiovascular events and death.”

Also in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration required new labeling on GnRH agonists warning of “increased risk of diabetes and certain cardiovascular diseases (heart attack, sudden cardiac death, stroke).”

Not unanimous

Two other large randomized studies (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 1;26[4]:585-91 and J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27[1]:92-9) and two retrospective studies (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jul 20;27[21]:3452-8 and J Clin Oncol. 2011 Sep 10;29[26]3510-16) found no excess risk of cardiovascular disease from ADT, Dr. Nguyen said, prompting him and his colleagues to see whether they could get a better estimate of the actual risk.

They did so through a 2011 meta-analysis (JAMA. 2011;306[21]:2359-66) of data on 4,141 patients from eight randomized trials. They found that among patients with unfavorable-risk prostate cancer, ADT was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death, but was associated with lower risks for both prostate-specific and all-cause mortality.

Subpopulations may still be at risk

Dr. Nguyen said that the principal finding of the meta-analysis, while reassuring, “doesn’t let ADT off the hook for metabolic events, diabetes which we know happens, and the possibility of nonfatal cardiac events.”

He noted that while ADT was not associated with cardiovascular disease in clinical trials, observational studies showed significantly increased risk for fatal or non-fatal MI.

One possible explanation for the difference is that observational studies included nonfatal MI, while randomized trials looked only at cardiovascular deaths. It’s also possible that ADT causes harm primarily in men with preexisting comorbidities, who are often excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Evidence from a 2009 study (JAMA. 2009 Aug 26;302[8]:866-73) showed that among men with clinical stage T1 to T3 noninvasive, nonmetastatic prostate cancer, neoadjuvant hormonal therapy with both a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist and a nonsteroidal antiandrogen was associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality for those with a history of coronary artery disease–induced heart failure, but not for men with either no comorbidities or only a single comorbidity such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes.

Clinical considerations

The decision to treat men with prostate cancer with ADT is therefore a balancing act, Dr. Nguyen said.

“As the risk of prostate cancer death goes up, the benefit of ADT goes up. However, as the comorbidity level goes up, the potential cardiovascular harm of ADT goes up,” he said.

For patients at the extreme ends of each continuum, such as a patient with high-risk prostate cancer and no cardiovascular comorbidities or a patient with low-risk cancer but multiple CV risk factors, the decision to give or withhold ADT is relatively simple, he said.

But for patients in between, such as a man with intermediate-risk cancer and one risk factor or a man with high risk disease with multiple comorbidities, the decision is far more complex.

“This where I think the dialogue with the cardiologist really needs to come into this decision,” he said.

Evidence to support the decision comes from retrospective studies suggesting that even men with high-risk prostate cancer have poorer overall survival with ADT if they have a history of heart failure or MI.

For patients with low-risk cancer and diabetes, ADT is associated with worse overall survival, but ADT does not cause additional harm to men with intermediate- to high-risk prostate cancer who have concomitant diabetes, Dr. Nguyen said.

“My view is that ADT has not been shown to increase cardiovascular death in randomized trials, so I think that for the vast majority of patients it probably does not increase cardiovascular deaths. But I think there could very well be a vulnerable 5% of patients who might have an excess risk of cardiovascular death, and I think we have to be careful, but we still have to balance it out against their risks for prostate cancer death,” he said.

Dr. Nguyen reported consulting fees/honoraria from Astellas, Augmenix, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Dendreon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GenomeDx, Janssen, and Nanobiotix.

WASHINGTON – The cardiovascular effects of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for men with advanced prostate cancer are less severe than once feared, but there is evidence to suggest that men with preexisting heart failure or a history of myocardial infarction could be at excess risk for death from cardiovascular causes when they receive ADT, according to a leading prostate cancer expert.

“I think there are concerns about potential cardiovascular harm of ADT, and I think this has reduced ADT use, despite the fact that we know for most men it improves overall survival,” said Paul Nguyen, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center in Boston.

“In fact, when we looked recently at men with high-risk prostate cancer, this is a group where overall survival is improved by 50% if they get ADT – so it cuts the risk of death in half – but it turns out that nearly a quarter of those patients are not receiving ADT. I think that the concern about cardiovascular harm and the confusion as to where that data stands is a lot of what’s driving that right now,” he said at the American College of Cardiology’s Advancing the Cardiovascular Care of the Oncology Patient meeting.

Randomized trial data

Dr. Nguyen noted that the evidence suggesting that ADT can increase the risk of death from cardiovascular causes came largely from three major studies:

- A 2006 study of 73,196 Medicare enrollees aged 66 or older, which found that ADT with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist was possibly associated with increased risk of incident diabetes and cardiovascular disease (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 20;24[27]:4448-56.).

- A 2007 analysis of data from the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CAPSURE) database on 3,262 men treated with radical prostatectomy and 1,630 men treated with radiation or cryotherapy for localized prostate cancer, which found that among those 65 and older the 5-year cumulative incidence of cardiovascular death was 5.5% for patients who received ADT, vs. 2% for those who did not (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Oct 17;99[20]:1516-24).

- A 2007 study of 1,372 men in three randomized trials of radiation therapy with or without androgen suppression therapy up to 8 months in duration, which found that men 65 and older who received 6 months of androgen suppression had significantly shorter times to fatal MIs than did men who did not receive the therapy (J Clin Oncol. 2007;25[17]:2420-5).

These studies, combined with observational data, led to a 2010 consensus statement from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association, with endorsement from the American Society for Radiation Oncology, which stated that “there may be a relation between ADT and cardiovascular events and death.”

Also in 2010, the Food and Drug Administration required new labeling on GnRH agonists warning of “increased risk of diabetes and certain cardiovascular diseases (heart attack, sudden cardiac death, stroke).”

Not unanimous

Two other large randomized studies (J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 1;26[4]:585-91 and J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jan 1;27[1]:92-9) and two retrospective studies (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Jul 20;27[21]:3452-8 and J Clin Oncol. 2011 Sep 10;29[26]3510-16) found no excess risk of cardiovascular disease from ADT, Dr. Nguyen said, prompting him and his colleagues to see whether they could get a better estimate of the actual risk.

They did so through a 2011 meta-analysis (JAMA. 2011;306[21]:2359-66) of data on 4,141 patients from eight randomized trials. They found that among patients with unfavorable-risk prostate cancer, ADT was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death, but was associated with lower risks for both prostate-specific and all-cause mortality.

Subpopulations may still be at risk

Dr. Nguyen said that the principal finding of the meta-analysis, while reassuring, “doesn’t let ADT off the hook for metabolic events, diabetes which we know happens, and the possibility of nonfatal cardiac events.”

He noted that while ADT was not associated with cardiovascular disease in clinical trials, observational studies showed significantly increased risk for fatal or non-fatal MI.

One possible explanation for the difference is that observational studies included nonfatal MI, while randomized trials looked only at cardiovascular deaths. It’s also possible that ADT causes harm primarily in men with preexisting comorbidities, who are often excluded from or underrepresented in clinical trials.

Evidence from a 2009 study (JAMA. 2009 Aug 26;302[8]:866-73) showed that among men with clinical stage T1 to T3 noninvasive, nonmetastatic prostate cancer, neoadjuvant hormonal therapy with both a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist and a nonsteroidal antiandrogen was associated with increased risk for all-cause mortality for those with a history of coronary artery disease–induced heart failure, but not for men with either no comorbidities or only a single comorbidity such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes.

Clinical considerations

The decision to treat men with prostate cancer with ADT is therefore a balancing act, Dr. Nguyen said.

“As the risk of prostate cancer death goes up, the benefit of ADT goes up. However, as the comorbidity level goes up, the potential cardiovascular harm of ADT goes up,” he said.

For patients at the extreme ends of each continuum, such as a patient with high-risk prostate cancer and no cardiovascular comorbidities or a patient with low-risk cancer but multiple CV risk factors, the decision to give or withhold ADT is relatively simple, he said.

But for patients in between, such as a man with intermediate-risk cancer and one risk factor or a man with high risk disease with multiple comorbidities, the decision is far more complex.

“This where I think the dialogue with the cardiologist really needs to come into this decision,” he said.

Evidence to support the decision comes from retrospective studies suggesting that even men with high-risk prostate cancer have poorer overall survival with ADT if they have a history of heart failure or MI.

For patients with low-risk cancer and diabetes, ADT is associated with worse overall survival, but ADT does not cause additional harm to men with intermediate- to high-risk prostate cancer who have concomitant diabetes, Dr. Nguyen said.

“My view is that ADT has not been shown to increase cardiovascular death in randomized trials, so I think that for the vast majority of patients it probably does not increase cardiovascular deaths. But I think there could very well be a vulnerable 5% of patients who might have an excess risk of cardiovascular death, and I think we have to be careful, but we still have to balance it out against their risks for prostate cancer death,” he said.

Dr. Nguyen reported consulting fees/honoraria from Astellas, Augmenix, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Dendreon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GenomeDx, Janssen, and Nanobiotix.

REPORTING FROM ACC CARDIO-ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Risk of cardiovascular death should be weighed against proven ADT benefits.

Major finding: ADT-related cardiovascular events appear limited to men with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

Study details: Review of clinical data on the cardiovascular consequences of ADT.

Disclosures: Dr. Nguyen reported consulting fees/honoraria from Astellas, Augmenix, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Cota, Dendreon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, GenomeDx, Janssen, and Nanobiotix.

FDA permits marketing of first M. genitalium diagnostic test

the first test for the diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) caused by the M. genitalium bacterium, the agency reported in a press release.

M. genitalium is associated with nongonococcal urethritis in men and cervicitis in women, causing 15%-30% of persistent or recurring urethritis cases and 10%-30% of cervicitis cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women. The assay is a nucleic acid amplification test, which can detect the bacterium in urine, as well as urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab samples.

In a clinical study of 11,774 samples, the Aptima assay correctly identified M. genitalium in about 90% of vaginal, male urethral, male urine, and penile samples. It also correctly identified the bacterium in female urine and endocervical samples 78% and 82% of the time, respectively. The test was even more accurate in identifying samples that did not have M. genitalium present, according to an FDA press release

“In the past, it has been hard to diagnose this organism. By being able to detect it more reliably, doctors may be able to more carefully tailor treatment and use medicines most likely to be effective,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in the press release. “Having accurate and reliable tests to identify the specific bacteria that’s causing an infection can assist doctors in choosing the right treatment for the right infection, which can reduce overuse of antibiotics and help in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.”

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

the first test for the diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) caused by the M. genitalium bacterium, the agency reported in a press release.

M. genitalium is associated with nongonococcal urethritis in men and cervicitis in women, causing 15%-30% of persistent or recurring urethritis cases and 10%-30% of cervicitis cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women. The assay is a nucleic acid amplification test, which can detect the bacterium in urine, as well as urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab samples.

In a clinical study of 11,774 samples, the Aptima assay correctly identified M. genitalium in about 90% of vaginal, male urethral, male urine, and penile samples. It also correctly identified the bacterium in female urine and endocervical samples 78% and 82% of the time, respectively. The test was even more accurate in identifying samples that did not have M. genitalium present, according to an FDA press release

“In the past, it has been hard to diagnose this organism. By being able to detect it more reliably, doctors may be able to more carefully tailor treatment and use medicines most likely to be effective,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in the press release. “Having accurate and reliable tests to identify the specific bacteria that’s causing an infection can assist doctors in choosing the right treatment for the right infection, which can reduce overuse of antibiotics and help in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.”

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

the first test for the diagnoses of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) caused by the M. genitalium bacterium, the agency reported in a press release.

M. genitalium is associated with nongonococcal urethritis in men and cervicitis in women, causing 15%-30% of persistent or recurring urethritis cases and 10%-30% of cervicitis cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It also can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in women. The assay is a nucleic acid amplification test, which can detect the bacterium in urine, as well as urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab samples.

In a clinical study of 11,774 samples, the Aptima assay correctly identified M. genitalium in about 90% of vaginal, male urethral, male urine, and penile samples. It also correctly identified the bacterium in female urine and endocervical samples 78% and 82% of the time, respectively. The test was even more accurate in identifying samples that did not have M. genitalium present, according to an FDA press release

“In the past, it has been hard to diagnose this organism. By being able to detect it more reliably, doctors may be able to more carefully tailor treatment and use medicines most likely to be effective,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, said in the press release. “Having accurate and reliable tests to identify the specific bacteria that’s causing an infection can assist doctors in choosing the right treatment for the right infection, which can reduce overuse of antibiotics and help in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.”

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

Stigma against gay fathers still common, especially in low-equality states

Gay men who become fathers still commonly experience barriers and stigma, but those living in states that offer legal protections experienced less stigma and fewer barriers, according to Ellen C. Perrin, MD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston and her associates.

A total of 732 fathers living in 47 states, with 1,316 children (average age, 13 years), responded to a survey, they wrote in Pediatrics. More than 80% had a male partner, 64% had earned a bachelor degree or higher, and 81% were white and non-Hispanic.

In 35% of cases, children entered a family through adoption and/or foster care, 14% through the assistance of a pregnancy carrier or surrogate, and 39% through a heterosexual relationship. Families in states with fewer legal protections were more likely to have been formed through heterosexual relationships (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.81), while families in states with a greater equality rating were more likely to have been formed through a pregnancy surrogate (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08-1.84). A total of 41% of fathers reported facing barriers to adoption, and 33% reported having difficulty arranging custody of children born in a heterosexual relationship.

Active stigma experienced by the fathers was most commonly experienced in a religious setting, reported by 35%, with other common sources including neighbors (28%), service providers (26%), family members (24%), gay friends (24%), the child’s school (18%), the workplace (16%), and in health care (11%). Children most often experienced active stigma by their friends (33%), followed by a religious setting (17%), school (16%), neighbors (15%), family (11%), and in health care settings (4%).

Active and avoidant stigma was more likely in states with a low equality rating, especially in religious settings and among family members and neighbors, the investigators noted.

“Given their important role as leaders in the community’s support for all families, pediatricians caring for children and their gay fathers should recognize the likelihood that stigma may be a part of the family’s experience and help both families and communities to counteract it. Pediatricians also have the opportunity to be leaders in opposing discrimination in religious and other community institutions,” Dr. Perrin and her associates wrote.

The study received funding from the Gil Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and private donations. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Perrin EC et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0683.

Gay men who become fathers still commonly experience barriers and stigma, but those living in states that offer legal protections experienced less stigma and fewer barriers, according to Ellen C. Perrin, MD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston and her associates.

A total of 732 fathers living in 47 states, with 1,316 children (average age, 13 years), responded to a survey, they wrote in Pediatrics. More than 80% had a male partner, 64% had earned a bachelor degree or higher, and 81% were white and non-Hispanic.

In 35% of cases, children entered a family through adoption and/or foster care, 14% through the assistance of a pregnancy carrier or surrogate, and 39% through a heterosexual relationship. Families in states with fewer legal protections were more likely to have been formed through heterosexual relationships (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.81), while families in states with a greater equality rating were more likely to have been formed through a pregnancy surrogate (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08-1.84). A total of 41% of fathers reported facing barriers to adoption, and 33% reported having difficulty arranging custody of children born in a heterosexual relationship.

Active stigma experienced by the fathers was most commonly experienced in a religious setting, reported by 35%, with other common sources including neighbors (28%), service providers (26%), family members (24%), gay friends (24%), the child’s school (18%), the workplace (16%), and in health care (11%). Children most often experienced active stigma by their friends (33%), followed by a religious setting (17%), school (16%), neighbors (15%), family (11%), and in health care settings (4%).

Active and avoidant stigma was more likely in states with a low equality rating, especially in religious settings and among family members and neighbors, the investigators noted.

“Given their important role as leaders in the community’s support for all families, pediatricians caring for children and their gay fathers should recognize the likelihood that stigma may be a part of the family’s experience and help both families and communities to counteract it. Pediatricians also have the opportunity to be leaders in opposing discrimination in religious and other community institutions,” Dr. Perrin and her associates wrote.

The study received funding from the Gil Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and private donations. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Perrin EC et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0683.

Gay men who become fathers still commonly experience barriers and stigma, but those living in states that offer legal protections experienced less stigma and fewer barriers, according to Ellen C. Perrin, MD, of Tufts Medical Center in Boston and her associates.

A total of 732 fathers living in 47 states, with 1,316 children (average age, 13 years), responded to a survey, they wrote in Pediatrics. More than 80% had a male partner, 64% had earned a bachelor degree or higher, and 81% were white and non-Hispanic.

In 35% of cases, children entered a family through adoption and/or foster care, 14% through the assistance of a pregnancy carrier or surrogate, and 39% through a heterosexual relationship. Families in states with fewer legal protections were more likely to have been formed through heterosexual relationships (odds ratio, 1.42; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-1.81), while families in states with a greater equality rating were more likely to have been formed through a pregnancy surrogate (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.08-1.84). A total of 41% of fathers reported facing barriers to adoption, and 33% reported having difficulty arranging custody of children born in a heterosexual relationship.

Active stigma experienced by the fathers was most commonly experienced in a religious setting, reported by 35%, with other common sources including neighbors (28%), service providers (26%), family members (24%), gay friends (24%), the child’s school (18%), the workplace (16%), and in health care (11%). Children most often experienced active stigma by their friends (33%), followed by a religious setting (17%), school (16%), neighbors (15%), family (11%), and in health care settings (4%).

Active and avoidant stigma was more likely in states with a low equality rating, especially in religious settings and among family members and neighbors, the investigators noted.

“Given their important role as leaders in the community’s support for all families, pediatricians caring for children and their gay fathers should recognize the likelihood that stigma may be a part of the family’s experience and help both families and communities to counteract it. Pediatricians also have the opportunity to be leaders in opposing discrimination in religious and other community institutions,” Dr. Perrin and her associates wrote.

The study received funding from the Gil Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and private donations. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Perrin EC et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0683.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Courts stop contraceptive mandate

Too much sleep and too little sleep are linked to atherosclerosis, there is no drop in gout prevalence, but there isn’t an increase either, and back pain persists in one in five patients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Too much sleep and too little sleep are linked to atherosclerosis, there is no drop in gout prevalence, but there isn’t an increase either, and back pain persists in one in five patients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Too much sleep and too little sleep are linked to atherosclerosis, there is no drop in gout prevalence, but there isn’t an increase either, and back pain persists in one in five patients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Deep sleep decreases, Alzheimer’s increases

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, physician groups are pushing back on Part B of the drug reimbursement proposal, dabigatran matches aspirin for second stroke prevention, and reassurance for pregnancy in atopic dermatitis.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Prenatal valproate and ADHD

Also today, one expert calls for better ways to preserve beta cell function in youth, synthetic opioids drive a spike in the number of fatal overdoses, and mothers may play a role in the link between depression in fathers and daughters.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, one expert calls for better ways to preserve beta cell function in youth, synthetic opioids drive a spike in the number of fatal overdoses, and mothers may play a role in the link between depression in fathers and daughters.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, one expert calls for better ways to preserve beta cell function in youth, synthetic opioids drive a spike in the number of fatal overdoses, and mothers may play a role in the link between depression in fathers and daughters.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Hypertension guidelines: Treat patients, not numbers

When treating high blood pressure, how low should we try to go? Debate continues about optimal blood pressure goals after publication of guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) in 2017 that set or permitted a treatment goal of less than 130 mm Hg, depending on the population.1

In this article, we summarize the evolution of hypertension guidelines and the evidence behind them.

HOW THE GOALS EVOLVED

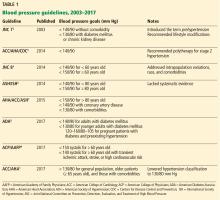

JNC 7, 2003: 140/90 or 130/80

The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7),2 published in 2003, specified treatment goals of:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for most patients

- < 130/80 mm Hg for those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

JNC 7 provided much-needed clarity and uniformity to managing hypertension. Since then, various scientific groups have published their own guidelines (Table 1).1–9

ACC/AHA/CDC 2014: 140/90

In 2014, the ACC, AHA, and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published an evidence-based algorithm for hypertension management.3 As in JNC 7, they suggested a blood pressure goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg, lifestyle modification, and polytherapy, eg, a thiazide diuretic for stage 1 hypertension (< 160/100 mm Hg) and combination therapy with a thiazide diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker for stage 2 hypertension (≥ 160/100 mm Hg).

JNC 8 2014: 140/90 or 150/90

Soon after, the much-anticipated report of the panel members appointed to the eighth JNC (JNC 8) was published.4 Previous JNC reports were written and published under the auspices of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, but while the JNC 8 report was being prepared, this government body announced it would no longer publish guidelines.

In contrast to JNC 7, the JNC 8 panel based its recommendations on a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. However, the process and methodology were controversial, especially as the panel excluded some important clinical trials from the analysis.

JNC 8 relaxed the targets in several subgroups, such as patients over age 60 and those with diabetes and chronic kidney disease, due to a lack of definitive evidence on the impact of blood pressure targets lower than 140/90 mm Hg in these groups. Thus, their goals were:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for patients under age 60

- < 150/90 mm Hg for patients age 60 and older.

Of note, a minority of the JNC 8 panel disagreed with the new targets and provided evidence for keeping the systolic blood pressure target below 140 mm Hg for patients 60 and older.5 Further, the JNC 8 report was not endorsed by several important societies, ie, the AHA, ACC, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and American Society of Hypertension (ASH). These issues compromised the acceptance and applicability of the guidelines.

ASH/ISH 2014: 140/90 or 150/90

Also in 2014, the ASH and the International Society of Hypertension released their own report.6 Their goals:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for most patients

- < 150/90 mm Hg for patients age 80 and older.

AHA/ACC/ASH 2015: Goals in subgroups

In 2015, the AHA, ACC, and ASH released a joint scientific statement outlining hypertension goals for specific patient populations7:

- < 150/90 mm Hg for those age 80 and older

- < 140/90 mm Hg for those with coronary artery disease

- < 130/80 mm Hg for those with comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

ADA 2016: Goals for patients with diabetes

In 2016, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) set the following blood pressure goals for patients with diabetes8:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for adults with diabetes

- < 130/80 mm Hg for younger adults with diabetes and adults with a high risk of cardiovascular disease

- 120–160/80–105 mm Hg for pregnant patients with diabetes and preexisting hypertension who are treated with antihypertensive therapy.

ACP/AAFP 2017: Systolic 150 or 130

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a relaxed systolic blood pressure target, ie, below 150 mm Hg, for adults over age 60, but a tighter goal of less than 140 mm Hg for the same age group if they have transient ischemic attack, stroke, or high cardiovascular risk.9

ACC/AHA 2017: 130/80

The 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines recommended a more aggressive goal of below 130/80 for all, including patients age 65 and older.1

This is a class I (strong) recommendation for patients with known cardiovascular disease or a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or higher, with a B-R level of evidence for the systolic goal (ie, moderate-quality, based on systematic review of randomized controlled trials) and a C-EO level of evidence for the diastolic goal (ie, based on expert opinion).

For patients who do not have cardiovascular disease and who are at lower risk of it, this is a class IIb (weak) recommendation, ie, it “may be reasonable,” with a B-NR level of evidence (moderate-quality, based on nonrandomized studies) for the systolic goal and C-EO (expert opinion) for the diastolic goal.

For many patients, this involves drug treatment. For those with known cardiovascular disease or a 10-year risk of an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease event of 10% or higher, the ACC/AHA guidelines say that drug treatment “is recommended” if their average blood pressure is 130/80 mm Hg or higher (class I recommendation, based on strong evidence for the systolic threshold and expert option for the diastolic). For those without cardiovascular disease and at lower risk, drug treatment is recommended if their average blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg or higher (also class I, but based on limited data).

EVERYONE AGREES ON LIFESTYLE

Although the guidelines differ in their blood pressure targets, they consistently recommend lifestyle modifications.

Lifestyle modifications, first described in JNC 7, included weight loss, sodium restriction, and the DASH diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, poultry, and fish, and low in red meat, sweets, cholesterol, and total and saturated fat.2

These recommendations were based on results from 3 large randomized controlled trials in patients with and without hypertension.10–12 In patients with no history of hypertension, interventions to promote weight loss and sodium restriction significantly reduced blood pressure and the incidence of hypertension (the latter by as much as 77%) compared with usual care.10,11

In patients with and without hypertension, lowering sodium intake in conjunction with the DASH diet was associated with substantially larger reductions in systolic blood pressure.12

The recommendation to lower sodium intake has not changed in the guideline revisions. Meanwhile, other modifications have been added, such as incorporating both aerobic and resistance exercise and moderating alcohol intake. These recommendations have a class I level of evidence (ie, strongest level) in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.1

HYPERTENSION BEGINS AT 130/80

The definition of hypertension changed in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines1: previously set at 140/90 mm Hg or higher, it is now 130/80 mm Hg or higher for all age groups. Adults with systolic blood pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 89 mm Hg are now classified as having stage 1 hypertension.

Under the new definition, the number of US adults who have hypertension expanded to 45.6% of the general population,13 up from 31.9% under the JNC 7 definition. Thus, overall, 103.3 million US adults now have hypertension, compared with 72.2 million under the JNC 7 criteria.

In addition, the new guidelines expanded the population of adults for whom antihypertensive drug treatment is recommended to 36.2% (81.9 million). However, this represents only a 1.9% absolute increase over the JNC 7 recommendations (34.3%) and a 5.1% absolute increase over the JNC 8 recommendations.14

SPRINT: INTENSIVE TREATMENT IS BENEFICIAL

The new ACC/AHA guidelines1 were based on evidence from several trials, including the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT).15

This multicenter trial investigated the effect of intensive blood pressure treatment on cardiovascular disease risk.16 The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and heart failure.

The trial enrolled 9,361 participants at least 50 years of age with systolic blood pressure 130 mm Hg or higher and at least 1 additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease. It excluded anyone with a history of diabetes mellitus, stroke, symptomatic heart failure, or end-stage renal disease.

Two interventions were compared:

- Intensive treatment, with a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 120 mm Hg: the protocol called for polytherapy, even for participants who were 75 or older if their blood pressure was 140 mm Hg or higher

- Standard treatment, with a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mm Hg: it used polytherapy for patients whose systolic blood pressure was 160 mm Hg or higher.

The trial was intended to last 5 years but was stopped early at a median of 3.26 years owing to a significantly lower rate of the primary composite outcome in the intensive-treatment group: 1.65% per year vs 2.19%, a 25% relative risk reduction (P < .001) or a 0.54% absolute risk reduction. We calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) for 1 year to prevent 1 event as 185, and over the 3.26 years of the trial, the investigators calculated the NNT as 61. Similarly, the rate of death from any cause was also lower with intensive treatment, 1.03% per year vs 1.40% per year, a 27% relative risk reduction (P = .003) or a 0.37% absolute risk reduction, NNT 270.

Using these findings, Bress et al16 estimated that implementing intensive blood pressure goals could prevent 107,500 deaths annually.

The downside is adverse effects. In SPRINT,15 the intensive-treatment group experienced significantly higher rates of serious adverse effects than the standard-treatment group, ie:

- Hypotension 2.4% vs 1.4%, P = .001

- Syncope 2.3% vs 1.7%, P = .05

- Electrolyte abnormalities 3.1% vs 2.3%, P = .02)

- Acute kidney injury or kidney failure 4.1% vs 2.5%, P < .001

- Any treatment-related adverse event 4.7% vs 2.5%, P = .001.

Thus, Bress et al16 estimated that fully implementing the intensive-treatment goals could cause an additional 56,100 episodes of hypotension per year, 34,400 cases of syncope, 43,400 serious electrolyte disorders, and 88,700 cases of acute kidney injury. All told, about 3 million Americans could suffer a serious adverse effect under the intensive-treatment goals.

SPRINT caveats and limitations

SPRINT15 was stopped early, after 3.26 years instead of the planned 5 years. The true risk-benefit ratio may have been different if the trial had been extended longer.

In addition, SPRINT used automated office blood pressure measurements in which patients were seated alone and a device (Model 907, Omron Healthcare) took 3 blood pressure measurements at 1-minute intervals after 5 minutes of quiet rest. This was designed to reduce elevated blood pressure readings in the presence of a healthcare professional in a medical setting (ie, “white coat” hypertension).

Many physicians are still taking blood pressure manually, which tends to give higher readings. Therefore, if they aim for a lower goal, they may risk overtreating the patient.

About 50% of patients did not achieve the target systolic blood pressure (< 120 mm Hg) despite receiving an average of 2.8 antihypertensive medications in the intensive-treatment group and 1.8 in the standard-treatment group. The use of antihypertensive medications, however, was not a controlled variable in the trial, and practitioners chose the appropriate drugs for their patients.

Diastolic pressure, which can be markedly lower in older hypertensive patients, was largely ignored, although lower diastolic pressure may have contributed to higher syncope rates in response to alpha blockers and calcium blockers.

Moreover, the trial excluded those with significant comorbidities and those younger than 50 (the mean age was 67.9), which limits the generalizability of the results.

JNC 8 VS SPRINT GOALS: WHAT'S THE EFFECT ON OUTCOMES?

JNC 84 recommended a relaxed target of less than 140/90 mm Hg for adults younger than 60, including those with chronic kidney disease or diabetes, and less than 150/90 mm Hg for adults 60 and older. The SPRINT findings upended those recommendations, showing that intensive treatment in adults age 75 or older significantly improved the composite cardiovascular disease outcome (2.59 vs 3.85 events per year; P < .001) and all-cause mortality (1.78 vs 2.63 events per year; P < .05) compared with standard treatment.17 Also, a subset review of SPRINT trial data found no difference in benefit based on chronic kidney disease status.18

A meta-analysis of 74 clinical trials (N = 306,273) offers a compromise between the SPRINT findings and the JNC 8 recommendations.19 It found that the beneficial effect of blood pressure treatment depended on the patient’s baseline systolic blood pressure. In those with a baseline systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher, treatment reduced cardiovascular mortality by about 15% (relative risk [RR] 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.95). In patients with systolic pressure below 140 mm Hg, treatment effects were neutral (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.87–1.20) and not associated with any benefit as primary prevention, although data suggest it may reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease.

OTHER TRIALS THAT INFLUENCED THE GUIDELINES

SHEP and HYVET (the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program20 and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial)21 supported intensive blood pressure treatment for older patients by reporting a reduction in fatal and nonfatal stroke risks for those with a systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg.

FEVER (the Felodipine Event Reduction study)22 found that treatment with a calcium channel blocker in even a low dose can significantly decrease cardiovascular events, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure compared with no treatment.

JATOS and VALISH (the Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients23 and the Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension study)24 found that outcomes were similar with intensive vs standard treatment.

Ettehad et al25 performed a meta-analysis of 123 studies with more than 600,000 participants that provided strong evidence supporting blood pressure treatment goals below 130/90 mm Hg, in line with the SPRINT trial results.

BLOOD PRESSURE ISN’T EVERYTHING

Other trials remind us that although blood pressure is important, it is not the only factor affecting cardiovascular risk.

HOPE (the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation)26 investigated the use of ramipril (an ACE inhibitor) in preventing myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events. The study included 9,297 participants over age 55 (mean age 66) with a baseline blood pressure 139/79 mm Hg. Follow-up was 4.5 years.

Ramipril was better than placebo, with significantly fewer patients experiencing adverse end points in the ramipril group compared with the placebo group:

- Myocardial infarction 9.9% vs 12.3%, RR 0.80, P < .001

- Cardiovascular death 6.1% vs 8.1%, RR 0.74, P < .001

- Stroke 3.4% vs 4.9%, RR = .68, P < .001

- The composite end point 14.0% vs 17.8%, RR 0.78, P < .001).

Results were even better in the subset of patients who had diabetes.27 However, the decrease in blood pressure attributable to antihypertensive therapy with ramipril was minimal (3–4 mm Hg systolic and 1–2 mm Hg diastolic). This slight change should not have been enough to produce significant differences in clinical outcomes, a major limitation of this trial. The investigators speculated that the positive results may be due to a class effect of ACE inhibitors.26

HOPE 328–30 explored the effect of blood pressure- and cholesterol-controlling drugs on the same primary end points but in patients at intermediate risk of major cardiovascular events. Investigators randomized the 12,705 patients to 4 treatment groups:

- Blood pressure control with candesartan (an ARB) plus hydrochlorothiazide (a thiazide diuretic)

- Cholesterol control with rosuvastatin (a statin)

- Blood pressure plus cholesterol control

- Placebo.

Therapy was started at a systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg.

Compared with placebo, the rate of composite events was significantly reduced in the rosuvastatin group (3.7% vs 4.8%, HR 0.76, P = .002)28 and the candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide-rosuvastatin group (3.6% vs 5.0%, HR 0.71; P = .005)29 but not in the candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide group (4.1% vs 4.4%; HR 0.93; P = .40).30

In addition, a subgroup analysis comparing active treatment vs placebo found a significant reduction in major cardiovascular events for treated patients whose baseline systolic blood pressure was in the upper third (> 143.5 mm Hg, mean 154.1 mm Hg), while treated patients in the lower middle and lower thirds had no significant reduction.30

These results suggest that intensive treatment to achieve a systolic blood pressure below 140 mm Hg in patients at intermediate risk may not be helpful. Nevertheless, there seems to be agreement that intensive treatment generally leads to a reduction in cardiovascular events. The results also show the benefit of lowering cholesterol.

Bundy et al31 performed a meta-analysis that provides support for intensive antihypertensive treatment. Reviewing 42 clinical trials in more than 144,000 patients, they found that treating to reach a target systolic blood pressure of 120 to 124 mm Hg can reduce cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

The trade-off is a minimal increase in the risk of adverse events. Also, the risk-benefit ratio of intensive treatment seems to vary in different patient subgroups.

WHAT ABOUT PATIENTS WITH COMORBIDITIES?

The debate over intensive vs standard treatment in blood pressure management extends beyond hypertension and includes important comorbidities such as diabetes, stroke, and renal disease. Patients with a history of stroke or end-stage renal disease have only a minimal mention in the AHA/ACC guidelines.

Diabetes

Emdin et al,32 in a meta-analysis of 40 trials that included more than 100,000 patients with diabetes, concluded that a 10-mm Hg lowering of systolic blood pressure significantly reduces the rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, albuminuria, and retinopathy. Stratifying the results according to the systolic blood pressure achieved (≥ 130 or < 130 mm Hg), the relative risks of mortality, coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and albuminuria were actually lower in the higher stratum than in the lower.

ACCORD (the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes)33 study provides contrary results. It examined intensive and standard blood pressure control targets in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular events, using primary outcome measures similar to those in SPRINT. It found no significant difference in fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events between the intensive and standard blood pressure target arms.

Despite those results, the ACC/AHA guidelines still advocate for more intensive treatment (goal < 130/80 mm Hg) in all patients, including those with diabetes.1

The ADA position statement (September 2017) recommended a target below 140/90 mm Hg in patients with diabetes and hypertension.8 However, they also noted that lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure targets, such as below 130/80 mm Hg, may be appropriate for patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease “if they can be achieved without undue treatment burden.”8 Thus, it is not clear which blood pressure targets in patients with diabetes are the best.

Stroke

In patients with stroke, AHA/ACC guidelines1 recommend treatment if the blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg or higher because antihypertensive therapy has been associated with a decrease in the recurrence of transient ischemic attack and stroke. The ideal target blood pressure is not known, but a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg may be reasonable.

In the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial, a retrospective open-label trial, a target blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg in patients with a history of lacunar stroke was associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage, but the difference was not statistically significant.34 For this reason, the ACC/AHA guidelines consider it reasonable to aim for a systolic blood pressure below 130 mm Hg in these patients.1

Renal disease

The ACC/AHA guidelines do not address how to manage hypertension in patients with end-stage renal disease, but for patients with chronic kidney disease they recommend a blood pressure target below 130/80 mm Hg.1 This recommendation is derived from the SPRINT trial,15 in which patients with stage 3 or 4 chronic kidney disease accounted for 28% of the study population. In that subgroup, intensive blood pressure control seemed to provide the same benefits for reduction in cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality.

TREAT PATIENTS, NOT NUMBERS

Blood pressure targets should be applied in the appropriate clinical context and on a patient-by-patient basis. In clinical practice, one size does not always fit all, as special cases exist.

For example, blood pressure can oscillate widely in patients with autonomic nerve disorders, making it difficult to strive for a specific target, especially an intensive one. Thus, it may be necessary to allow higher systolic blood pressure in these patients. Similarly, patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease may be at higher risk of kidney injury with more intensive blood pressure management.

Treating numbers rather than patients may result in unbalanced patient care. The optimal approach to blood pressure management relies on a comprehensive risk factor assessment and shared decision-making with the patient before setting specific blood pressure targets.

OUR APPROACH

We aim for a blood pressure goal below 130/80 mm Hg for all patients with cardiovascular disease, according to the AHA/ACC guidelines. We aim for that same target in patients without cardiovascular disease but who have an elevated estimated cardiovascular risk (> 10%) over the next 10 years.

We recognize, however, that the benefits of aggressive blood pressure reduction may not be as clear in all patients, such as those with diabetes. We also recognize that some patient subgroups are at high risk of adverse events, including those with low diastolic pressure, chronic kidney disease, a history of falls, and older age. In those patients, we are extremely judicious when titrating antihypertensive medications. We often make smaller titrations, at longer intervals, and with more frequent laboratory testing and in-office follow-up.

Our process of managing hypertension through intensive blood pressure control to achieve lower systolic blood pressure targets requires a concerted effort among healthcare providers at all levels. It especially requires more involvement and investment from primary care providers to individualize treatment in their patients. This process has helped us to reach our treatment goals while limiting adverse effects of lower blood pressure targets.

MOVING FORWARD

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and intensive blood pressure control has the potential to significantly reduce rates of morbidity and death associated with cardiovascular disease. Thus, a general consensus on the definition of hypertension and treatment goals is essential to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in this large patient population.

Intensive blood pressure treatment has shown efficacy, but it has a small accompanying risk of adverse events, which varies in patient subgroups and affects the benefit-risk ratio of this therapy. For example, the cardiovascular benefit of intensive treatment is less clear in diabetic patients, and the risk of adverse events may be higher in older patients with chronic kidney disease.

Moving forward, more research is needed into the effects of intensive and standard treatment on patients of all ages, those with common comorbid conditions, and those with other important factors such as diastolic hypertension.

Finally, the various medical societies should collaborate on hypertension guideline development. This would require considerable planning and coordination but would ultimately be useful in creating a generalizable approach to hypertension management.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71(19):e127–e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289(19):2560–2572. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560

- Go AS, Bauman MA, King SM, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension 2014; 63(4):878–885. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311(5):507–520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427

- Wright JT Jr, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160(7):499–503. doi:10.7326/M13-2981

- Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Notice of duplicate publication [duplicate publication of Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2014; 16(1):14–26. doi:10.1111/jch.12237] J Hypertens 2014; 32(1):3–15. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000065