User login

The family physician’s role in long COVID management

Several years into the pandemic, COVID-19 continues to deeply impact our society; at the time of publication of this review, 98.8 million cases in the United States have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 Although many people recover well from infection, there is mounting concern regarding long-term sequelae of COVID-19. These long-term symptoms have been termed long COVID, among other names.

What exactly is long COVID?

The CDC and National Institutes of Health define long COVID as new or ongoing health problems experienced ≥ 4 weeks after initial infection.2 Evidence suggests that even people who have mild initial COVID-19 symptoms are at risk for long COVID.

Available data about long COVID are imperfect, however; much about the condition remains poorly understood. For example, there is little evidence regarding the effect of vaccination and viral variants on the prevalence of long COVID. A recent study of more than 13 million people from the US Department of Veterans Affairs database did demonstrate that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 lowered the risk for long COVID by only about 15%.3

Persistent symptoms associated with long COVID often lead to disability and decreased quality of life. Furthermore, long COVID is a challenge to treat because there is a paucity of evidence to guide COVID-19 treatment beyond initial infection.

Because many patients who have ongoing COVID-19 symptoms will be seen in primary care, it is important to understand how to manage and support them. In this article, we discuss current understanding of long COVID epidemiology, symptoms that can persist 4 weeks after initial infection, and potential treatment options.

Prevalence and diagnosis

The prevalence of long COVID is not well defined because many epidemiologic studies rely on self-reporting. The CDC reports that 20% to 25% of COVID-19 survivors experience a new condition that might be attributable to their initial infection.4 Other studies variously cite 5% to 85% of people who have had a diagnosis of COVID-19 as experiencing long COVID, although that rate more consistently appears to be 10% to 30%.5

A study of adult patients in France found that self-reported symptoms of long COVID, 10 to 12 months after the first wave of the pandemic (May through November 2020), were associated with the belief of having had COVID-19 but not necessarily with having tested positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies,6 which indicates prior COVID-19. This complicates research on long COVID because, first, there is no specific test to confirm a diagnosis of long COVID and, second, studies often rely on self-reporting of earlier COVID-19.

Continue to: As such, long COVID...

As such, long COVID is diagnosed primarily through a medical history and physical examination. The medical history provides a guide as to whether additional testing is warranted to evaluate for known complications of COVID-19, such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, and pulmonary fibrosis. As of October 1, 2021, a new International Classification of Disease (10th Revision) code went into effect for post COVID condition, unspecified (U09.9).7

The prevalence of long COVID symptoms appears to increase with age. Among patients whose disease was diagnosed using code U09.9, most were 36 to 64 years of age; children and adults ages 22 years or younger constituted only 10.5% of diagnoses.7 Long COVID symptoms might also be more prevalent among women and in people with a preexisting chronic comorbidity.2,7

Symptoms can be numerous, severe or mild, and lasting

Initially, there was no widely accepted definition of long COVID; follow-up in early studies ranged from 21 days to 2 years after initial infection (or from discharge, for hospitalized patients).8 Differences in descriptions that have been used on surveys to self-report symptoms make it a challenge to clearly summarize the frequency of each aspect of long COVID.

Long COVID can be mild or debilitating; severity can fluctuate. Common symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea or other breathing difficulties, headache, and cognitive dysfunction, but as many as 203 lasting symptoms have been reported.2,8-12 From October 1, 2021, through January 31, 2022, the most common accompanying manifestations of long COVID were difficulty breathing, cough, and fatigue.7 Long COVID can affect multiple organ systems,13,14 with symptoms varying by organ system affected. Regardless of the need for hospitalization initially, having had COVID-19 significantly increases the risk for subsequent death at 30 days and at 6 months after initial infection.15

Symptoms of long COVID have been reported as long as 2 years after initial infection.8 When Davis and colleagues studied the onset and progression of reported symptoms of long COVID,9 they determined that, among patients who reported recovery from COVID-19 in < 90 days, symptoms peaked at approximately Week 2 of infection. In comparison, patients who reported not having recovered in < 90 days had (1) symptoms that peaked later (2 months) and (2) on average, more symptoms (mean, 17 reported symptoms, compared to 11 in recovered patients).9

Continue to: Fatigue

Fatigue, including postexertion malaise and impaired daily function and mobility, is the most common symptom of long COVID,8-10,14 reported in 28% to 98%14 of patients after initial COVID-19. This fatigue is more than simply being tired: Patients describe profound exhaustion, in which fatigue is out of proportion to exertion. Fatigue and myalgia are commonly reported among patients with impaired hepatic and pulmonary function as a consequence of long COVID.13 Patients often report that even minor activities result in decreased attention, focus, and energy, for many hours or days afterward. Fatigue has been reported to persist from 2.5 months to as long as 6 months after initial infection or hospitalization.9,16

Postviral fatigue has been seen in other viral outbreaks and seems to share characteristics with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, which itself has historically been stigmatized and poorly understood.17 Long COVID fatigue might be more common among women and patients who have an existing diagnosis of depression and antidepressant use,10,11,16,18 although the mechanism of this relationship is unclear. Potential mechanisms include damage from systemic inflammation to metabolism in the frontal lobe and cerebellum19 and direct infection by SARS-CoV-2 in skeletal muscle.20 Townsend and colleagues16 found no relationship between long COVID fatigue and markers of inflammation (leukocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts; the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; lactate dehydrogenase; C-reactive protein; serum interleukin-6; and soluble CD25).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are also common in long COVID and can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Studies have reported poor sleep quality or insomnia (38% to 90%), headache (17% to 91.2%), speech and language problems (48% to 50%), confusion (20%), dementia (28.6%), difficulty concentrating (1.9% to 27%), and memory loss or cognitive impairment (5.4% to 73%).9,10,14,15 For some patients, these symptoms persisted for ≥ 6 months, making it difficult for those affected to return to work.9

Isolation and loneliness, a common situation for patients with COVID-19, can have long-term effects on mental health.21 The COVID-19 pandemic itself has had a negative effect on behavioral health, including depression (4.3% to 25% of patients), anxiety (1.9% to 46%), obsessive compulsive disorder (4.9% to 20%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (29%).22 The persistence of symptoms of long COVID has resulted in a great deal of frustration, fear, and confusion for those affected—some of whom report a loss of trust in their community health care providers to address their ongoing struggles.23 Such loss can be accompanied by a reported increase in feelings of anxiety and changes to perceptions of self (ie, “how I used to be” in contrast to “how I am now”).23 These neuropsychiatric symptoms, including mental health conditions, appear to be more common among older adults.4

Other neurologic deficits found in long COVID include olfactory disorders (9% to 27% of patients), altered taste (5% to 18%), numbness or tingling sensations (6%), blurred vision (17.1%), and tinnitus (16.%).14 Dizziness (2.6% to 6%) and lightheadedness or presyncope (7%) have also been reported, although these symptoms appear to be less common than other neurocognitive effects.14

Continue to: The mechanism of action...

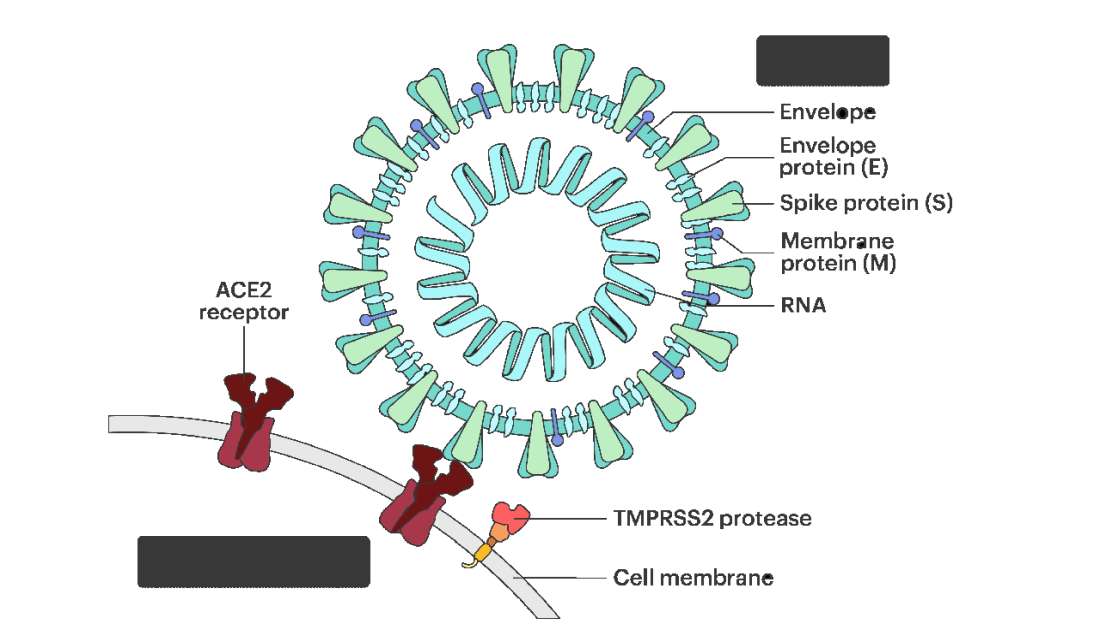

The mechanism of action of damage to the nervous system in long COVID is likely multifactorial. COVID-19 can directly infect the central nervous system through a hematogenous route, which can result in direct cytolytic damage to neurons. Infection can also affect the blood–brain barrier.24 Additionally, COVID-19 can invade the central nervous system through peripheral nerves, including the olfactory and vagus nerves.25 Many human respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, result in an increase in pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines; this so-called cytokine storm is an exaggerated response to infection and can trigger neurodegenerative and psychiatric syndromes.26 It is unclear whether the cytokine storm is different for people with COVID-19, compared to other respiratory viruses.

Respiratory symptoms are very common after COVID-1915: In studies, as many as 87.1% of patients continued to have shortness of breath ≥ 140 days after initial symptom onset, including breathlessness (48% to 60%), wheezing (5.3%), cough (10.5% to 46%), and congestion (32%),14,18 any of which can persist for as long as 6 months.9 Among a sample of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, 22% to 56% displayed a pulmonary diffusion abnormality 6 months later, with those who required supplemental oxygen during initial COVID-19 having a greater risk for these abnormalities at follow-up, compared to those who did not require supplemental oxygen (odds ratio = 2.42; 95% CI, 1.15-5.08).11

Cardiovascular symptoms. New-onset autonomic dysfunction has been described in multiple case reports and in some larger cohort studies of patients post COVID-19.27 Many common long COVID symptoms, including fatigue and orthostatic intolerance, are commonly seen in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Emerging evidence indicates that there are likely similar underlying mechanisms and a significant amount of overlap between long COVID and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.27

A study of patients within the US Department of Veterans Affairs population found that, regardless of disease severity, patients who had a positive COVID-19 test had a higher rate of cardiac disease 30 days after diagnosis,28 including stroke, transient ischemic attack, dysrhythmia, inflammatory heart disease, acute coronary disease, myocardial infarction, ischemic cardiopathy, angina, heart failure, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and cardiac arrest. Patients with COVID-19 were at increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality).28 Demographics of the VA population (ie, most are White men) might limit the generalizability of these data, but similar findings have been found elsewhere.5,10,15Given that, in general, chest pain is common after the acute phase of an infection and the causes of chest pain are broad, the high rate of cardiac complications post COVID-19 nevertheless highlights the importance of a thorough evaluation and work-up of chest pain in patients who have had COVID-19.

Other symptoms. Body aches and generalized joint pain are another common symptom group of long COVID.9 These include body aches (20%), joint pain (78%), and muscle aches (87.7%).14,18

Continue to: Commonly reported...

Commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, and abdominal pain.9,15

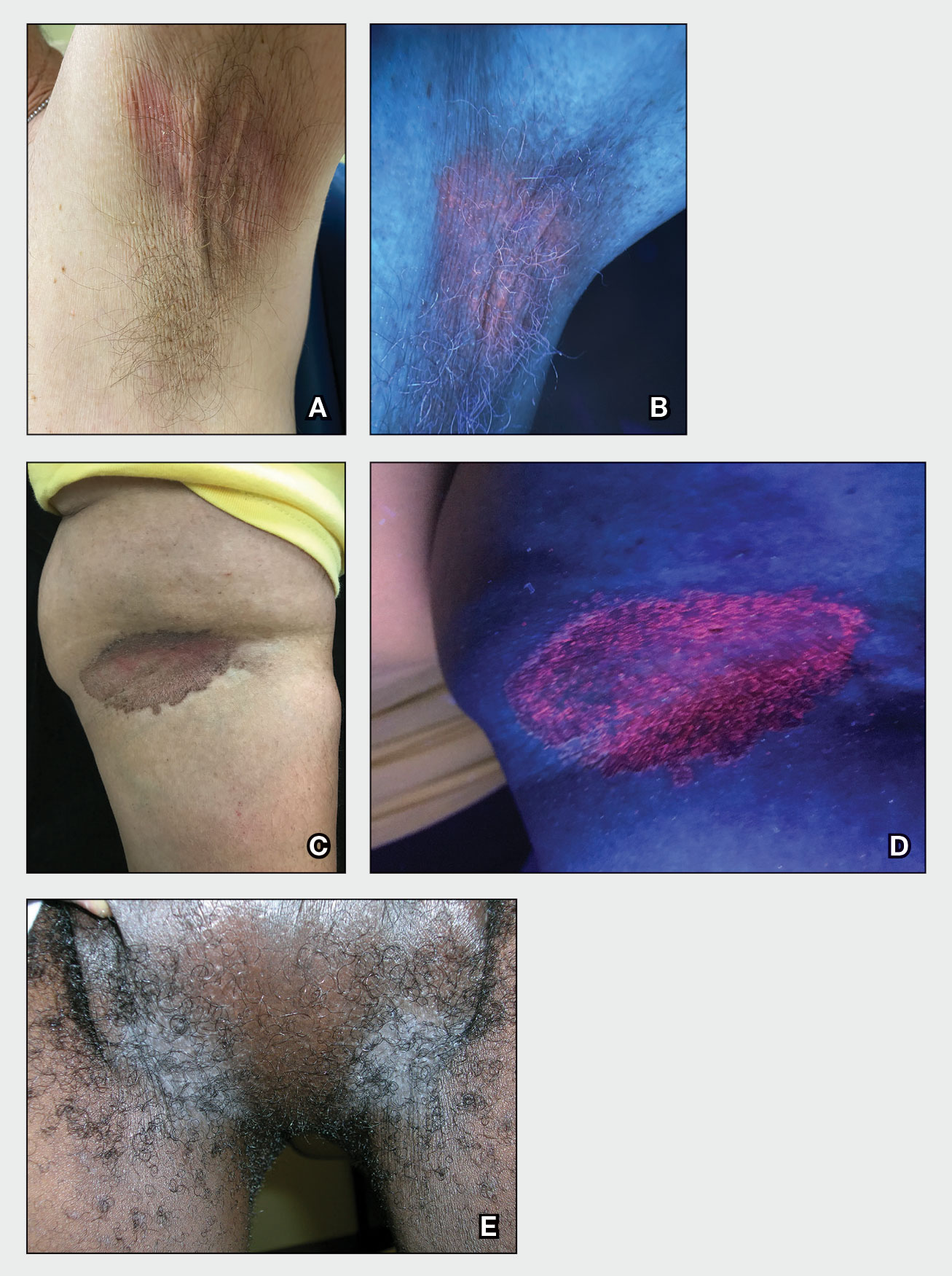

Other symptoms reported less commonly include dermatologic conditions, such as pruritus and rash; reproductive and endocrine symptoms, including extreme thirst, irregular menstruation, and sexual dysfunction; and new or exacerbated allergic response.9

Does severity of initial disease play a role?

Keep in mind that long COVID is not specific to patients who were hospitalized or had severe initial infection. In fact, 75% of patients who have a diagnosis of a post–COVID-19 condition were not hospitalized for their initial infection.7 However, the severity of initial COVID-19 infection might contribute to the presence or severity of long COVID symptoms2—although findings in current literature are mixed. For example:

- In reporting from Wuhan, China, higher position on a disease severity scale during a hospital stay for COVID-19 was associated with:

- greater likelihood of reporting ≥ 1 symptoms at a 6-month follow-up

- increased risk for pulmonary diffusion abnormalities, fatigue, and mood disorders.11

- After 2 years’ follow-up of the same cohort, 55% of patients continued to report ≥ 1 symptoms of long COVID, and those who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 continued to report reduced health-related quality of life, compared to the control group.8

- Similarly, patients initially hospitalized with COVID-19 were more likely to experience impairment of ≥ 2 organs—in particular, the liver and pancreas—compared to nonhospitalized patients after a median 5 months post initial infection, among a sample in the United Kingdom.13

- In an international cohort, patients who reported a greater number of symptoms during initial COVID-19 were more likely to experience long COVID.12

- Last, long COVID fatigue did not vary by severity of initial COVID-19 infection among a sample of hospitalized and nonhospitalized participants in Dublin, Ireland.16

No specific treatments yet available

There are no specific treatments for long COVID; overall, the emphasis is on providing supportive care and managing preexisting chronic conditions.5 This is where expertise in primary care, relationships with patients and the community, and psychosocial knowledge can help patients recover from ongoing COVID-19 symptoms.

Clinicians should continue to perform a thorough physical assessment of patients with previous or ongoing COVID-19 to identify and monitor new or recurring symptoms after hospital discharge or initial resolution of symptoms.29 This approach includes developing an individualized plan for care and rehabilitation that is specific to presenting symptoms, including psychological support. We encourage family physicians to familiarize themselves with the work of Vance and colleagues,30 who have created a comprehensive tablea to guide treatment and referral for the gamut of long COVID symptoms, including cardiovascular issues (eg, palpitations, edema), chronic cough, headache, pain, and insomnia.

Continue to: This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

Long COVID is a new condition that requires comprehensive evaluation to understand the full, often long-term, effects of COVID-19. Our review of this condition substantiated that symptoms of long COVID often affect a variety of organs13,14 and have been observed to persist for ≥ 2 years.8

Some studies that have examined the long-term effects of COVID-19 included only participants who were not hospitalized; others include hospitalized patients exclusively. The literature is mixed in regard to including severity of initial infection as it relates to long COVID. Available research demonstrates that it is common for people with COVID-19 to experience persistent symptoms that can significantly impact daily life and well-being.

Likely, it will be several years before we even begin to understand the full extent of COVID-19. Until research elucidates the relationship between the disease and short- and long-term health outcomes, clinicians should:

- acknowledge and address the reality of long COVID when meeting with persistently symptomatic patients,

- provide support, therapeutic listening, and referral to rehabilitation as appropriate, and

- offer information on the potential for long-term effects of COVID-19 to vaccine-hesitant patients.

a “Systems, symptoms, and treatments for post-COVID patients,” pages 1231-1234 in the source article (www.jabfm.org/content/jabfp/34/6/1229.full.pdf).30

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 46 Prince Street, Rochester, NY 14607; [email protected]

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. December 6, 2022. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated September 1, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

3. Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28:1461-1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0

4. Bull-Otterson L, Baca S, Saydah S, et al. Post-COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18-64 and ≥ 65 years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:713-717. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1

5. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026

6. Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, et al; . Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:19-25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454

7. FAIR Health. Patients diagnosed with post-COVID conditions: an analysis of private healthcare claims using the official ICD-10 diagnostic code. May 18, 2022. Accessed October 15, 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Patients%20Diagnosed%20with%20Post-COVID%20Con ditions%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

8. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:863-876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00126-6

9. Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

10. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

11. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220-232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

12. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626-631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

13. Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al; . Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048391. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391

14. Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, et al.. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648

15. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

16. Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PloS One. 2020;15:e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784

17. Wong TL, Weitzer DJ. Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—a systematic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:418. doi: 10.3390/ medicina57050418

18. Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199:113-119. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z

19. Guedj E, Million M, Dudouet P, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in post-SARS-CoV-2 infection: substrate for persistent/delayed disorders? Euro J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:592-595. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04973-x

20. Ferrandi PJ, Alway SE, Mohamed JS. The interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 may have consequences for skeletal muscle viral susceptibility and myopathies. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020;129:864-867. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00321.2020

21. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public health. 2017;152:157-171.

22. Kathirvel N. Post COVID-19 pandemic mental health challenges. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102430. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102430

23. Macpherson K, Cooper K, Harbour J, et al. Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e050979. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050979

24. Yachou Y, El Idrissi A, Belapasov V, et al. Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neuro Sci. 2020;41:2657-2669. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04575-3

25. Gialluisi A, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. New challenges from Covid-19 pandemic: an unexpected opportunity to enlighten the link between viral infections and brain disorders? Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1349-1350. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04444-z

26. Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027

27. Bisaccia G, Ricci F, Recce V, et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction: what do we know? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8:156. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8110156

28. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

29. Gorna R, MacDermott N, Rayner C, et al. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet. 2021;397:455-457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7

30. Vance H, Maslach A, Stoneman E, et al. Addressing post-COVID symptoms: a guide for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:1229-1242. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210254

Several years into the pandemic, COVID-19 continues to deeply impact our society; at the time of publication of this review, 98.8 million cases in the United States have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 Although many people recover well from infection, there is mounting concern regarding long-term sequelae of COVID-19. These long-term symptoms have been termed long COVID, among other names.

What exactly is long COVID?

The CDC and National Institutes of Health define long COVID as new or ongoing health problems experienced ≥ 4 weeks after initial infection.2 Evidence suggests that even people who have mild initial COVID-19 symptoms are at risk for long COVID.

Available data about long COVID are imperfect, however; much about the condition remains poorly understood. For example, there is little evidence regarding the effect of vaccination and viral variants on the prevalence of long COVID. A recent study of more than 13 million people from the US Department of Veterans Affairs database did demonstrate that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 lowered the risk for long COVID by only about 15%.3

Persistent symptoms associated with long COVID often lead to disability and decreased quality of life. Furthermore, long COVID is a challenge to treat because there is a paucity of evidence to guide COVID-19 treatment beyond initial infection.

Because many patients who have ongoing COVID-19 symptoms will be seen in primary care, it is important to understand how to manage and support them. In this article, we discuss current understanding of long COVID epidemiology, symptoms that can persist 4 weeks after initial infection, and potential treatment options.

Prevalence and diagnosis

The prevalence of long COVID is not well defined because many epidemiologic studies rely on self-reporting. The CDC reports that 20% to 25% of COVID-19 survivors experience a new condition that might be attributable to their initial infection.4 Other studies variously cite 5% to 85% of people who have had a diagnosis of COVID-19 as experiencing long COVID, although that rate more consistently appears to be 10% to 30%.5

A study of adult patients in France found that self-reported symptoms of long COVID, 10 to 12 months after the first wave of the pandemic (May through November 2020), were associated with the belief of having had COVID-19 but not necessarily with having tested positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies,6 which indicates prior COVID-19. This complicates research on long COVID because, first, there is no specific test to confirm a diagnosis of long COVID and, second, studies often rely on self-reporting of earlier COVID-19.

Continue to: As such, long COVID...

As such, long COVID is diagnosed primarily through a medical history and physical examination. The medical history provides a guide as to whether additional testing is warranted to evaluate for known complications of COVID-19, such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, and pulmonary fibrosis. As of October 1, 2021, a new International Classification of Disease (10th Revision) code went into effect for post COVID condition, unspecified (U09.9).7

The prevalence of long COVID symptoms appears to increase with age. Among patients whose disease was diagnosed using code U09.9, most were 36 to 64 years of age; children and adults ages 22 years or younger constituted only 10.5% of diagnoses.7 Long COVID symptoms might also be more prevalent among women and in people with a preexisting chronic comorbidity.2,7

Symptoms can be numerous, severe or mild, and lasting

Initially, there was no widely accepted definition of long COVID; follow-up in early studies ranged from 21 days to 2 years after initial infection (or from discharge, for hospitalized patients).8 Differences in descriptions that have been used on surveys to self-report symptoms make it a challenge to clearly summarize the frequency of each aspect of long COVID.

Long COVID can be mild or debilitating; severity can fluctuate. Common symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea or other breathing difficulties, headache, and cognitive dysfunction, but as many as 203 lasting symptoms have been reported.2,8-12 From October 1, 2021, through January 31, 2022, the most common accompanying manifestations of long COVID were difficulty breathing, cough, and fatigue.7 Long COVID can affect multiple organ systems,13,14 with symptoms varying by organ system affected. Regardless of the need for hospitalization initially, having had COVID-19 significantly increases the risk for subsequent death at 30 days and at 6 months after initial infection.15

Symptoms of long COVID have been reported as long as 2 years after initial infection.8 When Davis and colleagues studied the onset and progression of reported symptoms of long COVID,9 they determined that, among patients who reported recovery from COVID-19 in < 90 days, symptoms peaked at approximately Week 2 of infection. In comparison, patients who reported not having recovered in < 90 days had (1) symptoms that peaked later (2 months) and (2) on average, more symptoms (mean, 17 reported symptoms, compared to 11 in recovered patients).9

Continue to: Fatigue

Fatigue, including postexertion malaise and impaired daily function and mobility, is the most common symptom of long COVID,8-10,14 reported in 28% to 98%14 of patients after initial COVID-19. This fatigue is more than simply being tired: Patients describe profound exhaustion, in which fatigue is out of proportion to exertion. Fatigue and myalgia are commonly reported among patients with impaired hepatic and pulmonary function as a consequence of long COVID.13 Patients often report that even minor activities result in decreased attention, focus, and energy, for many hours or days afterward. Fatigue has been reported to persist from 2.5 months to as long as 6 months after initial infection or hospitalization.9,16

Postviral fatigue has been seen in other viral outbreaks and seems to share characteristics with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, which itself has historically been stigmatized and poorly understood.17 Long COVID fatigue might be more common among women and patients who have an existing diagnosis of depression and antidepressant use,10,11,16,18 although the mechanism of this relationship is unclear. Potential mechanisms include damage from systemic inflammation to metabolism in the frontal lobe and cerebellum19 and direct infection by SARS-CoV-2 in skeletal muscle.20 Townsend and colleagues16 found no relationship between long COVID fatigue and markers of inflammation (leukocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts; the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; lactate dehydrogenase; C-reactive protein; serum interleukin-6; and soluble CD25).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are also common in long COVID and can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Studies have reported poor sleep quality or insomnia (38% to 90%), headache (17% to 91.2%), speech and language problems (48% to 50%), confusion (20%), dementia (28.6%), difficulty concentrating (1.9% to 27%), and memory loss or cognitive impairment (5.4% to 73%).9,10,14,15 For some patients, these symptoms persisted for ≥ 6 months, making it difficult for those affected to return to work.9

Isolation and loneliness, a common situation for patients with COVID-19, can have long-term effects on mental health.21 The COVID-19 pandemic itself has had a negative effect on behavioral health, including depression (4.3% to 25% of patients), anxiety (1.9% to 46%), obsessive compulsive disorder (4.9% to 20%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (29%).22 The persistence of symptoms of long COVID has resulted in a great deal of frustration, fear, and confusion for those affected—some of whom report a loss of trust in their community health care providers to address their ongoing struggles.23 Such loss can be accompanied by a reported increase in feelings of anxiety and changes to perceptions of self (ie, “how I used to be” in contrast to “how I am now”).23 These neuropsychiatric symptoms, including mental health conditions, appear to be more common among older adults.4

Other neurologic deficits found in long COVID include olfactory disorders (9% to 27% of patients), altered taste (5% to 18%), numbness or tingling sensations (6%), blurred vision (17.1%), and tinnitus (16.%).14 Dizziness (2.6% to 6%) and lightheadedness or presyncope (7%) have also been reported, although these symptoms appear to be less common than other neurocognitive effects.14

Continue to: The mechanism of action...

The mechanism of action of damage to the nervous system in long COVID is likely multifactorial. COVID-19 can directly infect the central nervous system through a hematogenous route, which can result in direct cytolytic damage to neurons. Infection can also affect the blood–brain barrier.24 Additionally, COVID-19 can invade the central nervous system through peripheral nerves, including the olfactory and vagus nerves.25 Many human respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, result in an increase in pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines; this so-called cytokine storm is an exaggerated response to infection and can trigger neurodegenerative and psychiatric syndromes.26 It is unclear whether the cytokine storm is different for people with COVID-19, compared to other respiratory viruses.

Respiratory symptoms are very common after COVID-1915: In studies, as many as 87.1% of patients continued to have shortness of breath ≥ 140 days after initial symptom onset, including breathlessness (48% to 60%), wheezing (5.3%), cough (10.5% to 46%), and congestion (32%),14,18 any of which can persist for as long as 6 months.9 Among a sample of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, 22% to 56% displayed a pulmonary diffusion abnormality 6 months later, with those who required supplemental oxygen during initial COVID-19 having a greater risk for these abnormalities at follow-up, compared to those who did not require supplemental oxygen (odds ratio = 2.42; 95% CI, 1.15-5.08).11

Cardiovascular symptoms. New-onset autonomic dysfunction has been described in multiple case reports and in some larger cohort studies of patients post COVID-19.27 Many common long COVID symptoms, including fatigue and orthostatic intolerance, are commonly seen in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Emerging evidence indicates that there are likely similar underlying mechanisms and a significant amount of overlap between long COVID and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.27

A study of patients within the US Department of Veterans Affairs population found that, regardless of disease severity, patients who had a positive COVID-19 test had a higher rate of cardiac disease 30 days after diagnosis,28 including stroke, transient ischemic attack, dysrhythmia, inflammatory heart disease, acute coronary disease, myocardial infarction, ischemic cardiopathy, angina, heart failure, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and cardiac arrest. Patients with COVID-19 were at increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality).28 Demographics of the VA population (ie, most are White men) might limit the generalizability of these data, but similar findings have been found elsewhere.5,10,15Given that, in general, chest pain is common after the acute phase of an infection and the causes of chest pain are broad, the high rate of cardiac complications post COVID-19 nevertheless highlights the importance of a thorough evaluation and work-up of chest pain in patients who have had COVID-19.

Other symptoms. Body aches and generalized joint pain are another common symptom group of long COVID.9 These include body aches (20%), joint pain (78%), and muscle aches (87.7%).14,18

Continue to: Commonly reported...

Commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, and abdominal pain.9,15

Other symptoms reported less commonly include dermatologic conditions, such as pruritus and rash; reproductive and endocrine symptoms, including extreme thirst, irregular menstruation, and sexual dysfunction; and new or exacerbated allergic response.9

Does severity of initial disease play a role?

Keep in mind that long COVID is not specific to patients who were hospitalized or had severe initial infection. In fact, 75% of patients who have a diagnosis of a post–COVID-19 condition were not hospitalized for their initial infection.7 However, the severity of initial COVID-19 infection might contribute to the presence or severity of long COVID symptoms2—although findings in current literature are mixed. For example:

- In reporting from Wuhan, China, higher position on a disease severity scale during a hospital stay for COVID-19 was associated with:

- greater likelihood of reporting ≥ 1 symptoms at a 6-month follow-up

- increased risk for pulmonary diffusion abnormalities, fatigue, and mood disorders.11

- After 2 years’ follow-up of the same cohort, 55% of patients continued to report ≥ 1 symptoms of long COVID, and those who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 continued to report reduced health-related quality of life, compared to the control group.8

- Similarly, patients initially hospitalized with COVID-19 were more likely to experience impairment of ≥ 2 organs—in particular, the liver and pancreas—compared to nonhospitalized patients after a median 5 months post initial infection, among a sample in the United Kingdom.13

- In an international cohort, patients who reported a greater number of symptoms during initial COVID-19 were more likely to experience long COVID.12

- Last, long COVID fatigue did not vary by severity of initial COVID-19 infection among a sample of hospitalized and nonhospitalized participants in Dublin, Ireland.16

No specific treatments yet available

There are no specific treatments for long COVID; overall, the emphasis is on providing supportive care and managing preexisting chronic conditions.5 This is where expertise in primary care, relationships with patients and the community, and psychosocial knowledge can help patients recover from ongoing COVID-19 symptoms.

Clinicians should continue to perform a thorough physical assessment of patients with previous or ongoing COVID-19 to identify and monitor new or recurring symptoms after hospital discharge or initial resolution of symptoms.29 This approach includes developing an individualized plan for care and rehabilitation that is specific to presenting symptoms, including psychological support. We encourage family physicians to familiarize themselves with the work of Vance and colleagues,30 who have created a comprehensive tablea to guide treatment and referral for the gamut of long COVID symptoms, including cardiovascular issues (eg, palpitations, edema), chronic cough, headache, pain, and insomnia.

Continue to: This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

Long COVID is a new condition that requires comprehensive evaluation to understand the full, often long-term, effects of COVID-19. Our review of this condition substantiated that symptoms of long COVID often affect a variety of organs13,14 and have been observed to persist for ≥ 2 years.8

Some studies that have examined the long-term effects of COVID-19 included only participants who were not hospitalized; others include hospitalized patients exclusively. The literature is mixed in regard to including severity of initial infection as it relates to long COVID. Available research demonstrates that it is common for people with COVID-19 to experience persistent symptoms that can significantly impact daily life and well-being.

Likely, it will be several years before we even begin to understand the full extent of COVID-19. Until research elucidates the relationship between the disease and short- and long-term health outcomes, clinicians should:

- acknowledge and address the reality of long COVID when meeting with persistently symptomatic patients,

- provide support, therapeutic listening, and referral to rehabilitation as appropriate, and

- offer information on the potential for long-term effects of COVID-19 to vaccine-hesitant patients.

a “Systems, symptoms, and treatments for post-COVID patients,” pages 1231-1234 in the source article (www.jabfm.org/content/jabfp/34/6/1229.full.pdf).30

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 46 Prince Street, Rochester, NY 14607; [email protected]

Several years into the pandemic, COVID-19 continues to deeply impact our society; at the time of publication of this review, 98.8 million cases in the United States have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).1 Although many people recover well from infection, there is mounting concern regarding long-term sequelae of COVID-19. These long-term symptoms have been termed long COVID, among other names.

What exactly is long COVID?

The CDC and National Institutes of Health define long COVID as new or ongoing health problems experienced ≥ 4 weeks after initial infection.2 Evidence suggests that even people who have mild initial COVID-19 symptoms are at risk for long COVID.

Available data about long COVID are imperfect, however; much about the condition remains poorly understood. For example, there is little evidence regarding the effect of vaccination and viral variants on the prevalence of long COVID. A recent study of more than 13 million people from the US Department of Veterans Affairs database did demonstrate that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 lowered the risk for long COVID by only about 15%.3

Persistent symptoms associated with long COVID often lead to disability and decreased quality of life. Furthermore, long COVID is a challenge to treat because there is a paucity of evidence to guide COVID-19 treatment beyond initial infection.

Because many patients who have ongoing COVID-19 symptoms will be seen in primary care, it is important to understand how to manage and support them. In this article, we discuss current understanding of long COVID epidemiology, symptoms that can persist 4 weeks after initial infection, and potential treatment options.

Prevalence and diagnosis

The prevalence of long COVID is not well defined because many epidemiologic studies rely on self-reporting. The CDC reports that 20% to 25% of COVID-19 survivors experience a new condition that might be attributable to their initial infection.4 Other studies variously cite 5% to 85% of people who have had a diagnosis of COVID-19 as experiencing long COVID, although that rate more consistently appears to be 10% to 30%.5

A study of adult patients in France found that self-reported symptoms of long COVID, 10 to 12 months after the first wave of the pandemic (May through November 2020), were associated with the belief of having had COVID-19 but not necessarily with having tested positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies,6 which indicates prior COVID-19. This complicates research on long COVID because, first, there is no specific test to confirm a diagnosis of long COVID and, second, studies often rely on self-reporting of earlier COVID-19.

Continue to: As such, long COVID...

As such, long COVID is diagnosed primarily through a medical history and physical examination. The medical history provides a guide as to whether additional testing is warranted to evaluate for known complications of COVID-19, such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, and pulmonary fibrosis. As of October 1, 2021, a new International Classification of Disease (10th Revision) code went into effect for post COVID condition, unspecified (U09.9).7

The prevalence of long COVID symptoms appears to increase with age. Among patients whose disease was diagnosed using code U09.9, most were 36 to 64 years of age; children and adults ages 22 years or younger constituted only 10.5% of diagnoses.7 Long COVID symptoms might also be more prevalent among women and in people with a preexisting chronic comorbidity.2,7

Symptoms can be numerous, severe or mild, and lasting

Initially, there was no widely accepted definition of long COVID; follow-up in early studies ranged from 21 days to 2 years after initial infection (or from discharge, for hospitalized patients).8 Differences in descriptions that have been used on surveys to self-report symptoms make it a challenge to clearly summarize the frequency of each aspect of long COVID.

Long COVID can be mild or debilitating; severity can fluctuate. Common symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea or other breathing difficulties, headache, and cognitive dysfunction, but as many as 203 lasting symptoms have been reported.2,8-12 From October 1, 2021, through January 31, 2022, the most common accompanying manifestations of long COVID were difficulty breathing, cough, and fatigue.7 Long COVID can affect multiple organ systems,13,14 with symptoms varying by organ system affected. Regardless of the need for hospitalization initially, having had COVID-19 significantly increases the risk for subsequent death at 30 days and at 6 months after initial infection.15

Symptoms of long COVID have been reported as long as 2 years after initial infection.8 When Davis and colleagues studied the onset and progression of reported symptoms of long COVID,9 they determined that, among patients who reported recovery from COVID-19 in < 90 days, symptoms peaked at approximately Week 2 of infection. In comparison, patients who reported not having recovered in < 90 days had (1) symptoms that peaked later (2 months) and (2) on average, more symptoms (mean, 17 reported symptoms, compared to 11 in recovered patients).9

Continue to: Fatigue

Fatigue, including postexertion malaise and impaired daily function and mobility, is the most common symptom of long COVID,8-10,14 reported in 28% to 98%14 of patients after initial COVID-19. This fatigue is more than simply being tired: Patients describe profound exhaustion, in which fatigue is out of proportion to exertion. Fatigue and myalgia are commonly reported among patients with impaired hepatic and pulmonary function as a consequence of long COVID.13 Patients often report that even minor activities result in decreased attention, focus, and energy, for many hours or days afterward. Fatigue has been reported to persist from 2.5 months to as long as 6 months after initial infection or hospitalization.9,16

Postviral fatigue has been seen in other viral outbreaks and seems to share characteristics with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, or ME/CFS, which itself has historically been stigmatized and poorly understood.17 Long COVID fatigue might be more common among women and patients who have an existing diagnosis of depression and antidepressant use,10,11,16,18 although the mechanism of this relationship is unclear. Potential mechanisms include damage from systemic inflammation to metabolism in the frontal lobe and cerebellum19 and direct infection by SARS-CoV-2 in skeletal muscle.20 Townsend and colleagues16 found no relationship between long COVID fatigue and markers of inflammation (leukocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts; the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; lactate dehydrogenase; C-reactive protein; serum interleukin-6; and soluble CD25).

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are also common in long COVID and can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Studies have reported poor sleep quality or insomnia (38% to 90%), headache (17% to 91.2%), speech and language problems (48% to 50%), confusion (20%), dementia (28.6%), difficulty concentrating (1.9% to 27%), and memory loss or cognitive impairment (5.4% to 73%).9,10,14,15 For some patients, these symptoms persisted for ≥ 6 months, making it difficult for those affected to return to work.9

Isolation and loneliness, a common situation for patients with COVID-19, can have long-term effects on mental health.21 The COVID-19 pandemic itself has had a negative effect on behavioral health, including depression (4.3% to 25% of patients), anxiety (1.9% to 46%), obsessive compulsive disorder (4.9% to 20%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (29%).22 The persistence of symptoms of long COVID has resulted in a great deal of frustration, fear, and confusion for those affected—some of whom report a loss of trust in their community health care providers to address their ongoing struggles.23 Such loss can be accompanied by a reported increase in feelings of anxiety and changes to perceptions of self (ie, “how I used to be” in contrast to “how I am now”).23 These neuropsychiatric symptoms, including mental health conditions, appear to be more common among older adults.4

Other neurologic deficits found in long COVID include olfactory disorders (9% to 27% of patients), altered taste (5% to 18%), numbness or tingling sensations (6%), blurred vision (17.1%), and tinnitus (16.%).14 Dizziness (2.6% to 6%) and lightheadedness or presyncope (7%) have also been reported, although these symptoms appear to be less common than other neurocognitive effects.14

Continue to: The mechanism of action...

The mechanism of action of damage to the nervous system in long COVID is likely multifactorial. COVID-19 can directly infect the central nervous system through a hematogenous route, which can result in direct cytolytic damage to neurons. Infection can also affect the blood–brain barrier.24 Additionally, COVID-19 can invade the central nervous system through peripheral nerves, including the olfactory and vagus nerves.25 Many human respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, result in an increase in pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines; this so-called cytokine storm is an exaggerated response to infection and can trigger neurodegenerative and psychiatric syndromes.26 It is unclear whether the cytokine storm is different for people with COVID-19, compared to other respiratory viruses.

Respiratory symptoms are very common after COVID-1915: In studies, as many as 87.1% of patients continued to have shortness of breath ≥ 140 days after initial symptom onset, including breathlessness (48% to 60%), wheezing (5.3%), cough (10.5% to 46%), and congestion (32%),14,18 any of which can persist for as long as 6 months.9 Among a sample of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, 22% to 56% displayed a pulmonary diffusion abnormality 6 months later, with those who required supplemental oxygen during initial COVID-19 having a greater risk for these abnormalities at follow-up, compared to those who did not require supplemental oxygen (odds ratio = 2.42; 95% CI, 1.15-5.08).11

Cardiovascular symptoms. New-onset autonomic dysfunction has been described in multiple case reports and in some larger cohort studies of patients post COVID-19.27 Many common long COVID symptoms, including fatigue and orthostatic intolerance, are commonly seen in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Emerging evidence indicates that there are likely similar underlying mechanisms and a significant amount of overlap between long COVID and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.27

A study of patients within the US Department of Veterans Affairs population found that, regardless of disease severity, patients who had a positive COVID-19 test had a higher rate of cardiac disease 30 days after diagnosis,28 including stroke, transient ischemic attack, dysrhythmia, inflammatory heart disease, acute coronary disease, myocardial infarction, ischemic cardiopathy, angina, heart failure, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and cardiac arrest. Patients with COVID-19 were at increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality).28 Demographics of the VA population (ie, most are White men) might limit the generalizability of these data, but similar findings have been found elsewhere.5,10,15Given that, in general, chest pain is common after the acute phase of an infection and the causes of chest pain are broad, the high rate of cardiac complications post COVID-19 nevertheless highlights the importance of a thorough evaluation and work-up of chest pain in patients who have had COVID-19.

Other symptoms. Body aches and generalized joint pain are another common symptom group of long COVID.9 These include body aches (20%), joint pain (78%), and muscle aches (87.7%).14,18

Continue to: Commonly reported...

Commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, and abdominal pain.9,15

Other symptoms reported less commonly include dermatologic conditions, such as pruritus and rash; reproductive and endocrine symptoms, including extreme thirst, irregular menstruation, and sexual dysfunction; and new or exacerbated allergic response.9

Does severity of initial disease play a role?

Keep in mind that long COVID is not specific to patients who were hospitalized or had severe initial infection. In fact, 75% of patients who have a diagnosis of a post–COVID-19 condition were not hospitalized for their initial infection.7 However, the severity of initial COVID-19 infection might contribute to the presence or severity of long COVID symptoms2—although findings in current literature are mixed. For example:

- In reporting from Wuhan, China, higher position on a disease severity scale during a hospital stay for COVID-19 was associated with:

- greater likelihood of reporting ≥ 1 symptoms at a 6-month follow-up

- increased risk for pulmonary diffusion abnormalities, fatigue, and mood disorders.11

- After 2 years’ follow-up of the same cohort, 55% of patients continued to report ≥ 1 symptoms of long COVID, and those who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 continued to report reduced health-related quality of life, compared to the control group.8

- Similarly, patients initially hospitalized with COVID-19 were more likely to experience impairment of ≥ 2 organs—in particular, the liver and pancreas—compared to nonhospitalized patients after a median 5 months post initial infection, among a sample in the United Kingdom.13

- In an international cohort, patients who reported a greater number of symptoms during initial COVID-19 were more likely to experience long COVID.12

- Last, long COVID fatigue did not vary by severity of initial COVID-19 infection among a sample of hospitalized and nonhospitalized participants in Dublin, Ireland.16

No specific treatments yet available

There are no specific treatments for long COVID; overall, the emphasis is on providing supportive care and managing preexisting chronic conditions.5 This is where expertise in primary care, relationships with patients and the community, and psychosocial knowledge can help patients recover from ongoing COVID-19 symptoms.

Clinicians should continue to perform a thorough physical assessment of patients with previous or ongoing COVID-19 to identify and monitor new or recurring symptoms after hospital discharge or initial resolution of symptoms.29 This approach includes developing an individualized plan for care and rehabilitation that is specific to presenting symptoms, including psychological support. We encourage family physicians to familiarize themselves with the work of Vance and colleagues,30 who have created a comprehensive tablea to guide treatment and referral for the gamut of long COVID symptoms, including cardiovascular issues (eg, palpitations, edema), chronic cough, headache, pain, and insomnia.

Continue to: This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

This new clinical entity is a formidable challenge

Long COVID is a new condition that requires comprehensive evaluation to understand the full, often long-term, effects of COVID-19. Our review of this condition substantiated that symptoms of long COVID often affect a variety of organs13,14 and have been observed to persist for ≥ 2 years.8

Some studies that have examined the long-term effects of COVID-19 included only participants who were not hospitalized; others include hospitalized patients exclusively. The literature is mixed in regard to including severity of initial infection as it relates to long COVID. Available research demonstrates that it is common for people with COVID-19 to experience persistent symptoms that can significantly impact daily life and well-being.

Likely, it will be several years before we even begin to understand the full extent of COVID-19. Until research elucidates the relationship between the disease and short- and long-term health outcomes, clinicians should:

- acknowledge and address the reality of long COVID when meeting with persistently symptomatic patients,

- provide support, therapeutic listening, and referral to rehabilitation as appropriate, and

- offer information on the potential for long-term effects of COVID-19 to vaccine-hesitant patients.

a “Systems, symptoms, and treatments for post-COVID patients,” pages 1231-1234 in the source article (www.jabfm.org/content/jabfp/34/6/1229.full.pdf).30

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicole Mayo, PhD, 46 Prince Street, Rochester, NY 14607; [email protected]

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. December 6, 2022. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated September 1, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

3. Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28:1461-1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0

4. Bull-Otterson L, Baca S, Saydah S, et al. Post-COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18-64 and ≥ 65 years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:713-717. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1

5. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026

6. Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, et al; . Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:19-25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454

7. FAIR Health. Patients diagnosed with post-COVID conditions: an analysis of private healthcare claims using the official ICD-10 diagnostic code. May 18, 2022. Accessed October 15, 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Patients%20Diagnosed%20with%20Post-COVID%20Con ditions%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

8. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:863-876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00126-6

9. Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

10. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

11. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220-232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

12. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626-631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

13. Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al; . Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048391. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391

14. Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, et al.. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648

15. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

16. Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PloS One. 2020;15:e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784

17. Wong TL, Weitzer DJ. Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—a systematic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:418. doi: 10.3390/ medicina57050418

18. Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199:113-119. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z

19. Guedj E, Million M, Dudouet P, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in post-SARS-CoV-2 infection: substrate for persistent/delayed disorders? Euro J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:592-595. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04973-x

20. Ferrandi PJ, Alway SE, Mohamed JS. The interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 may have consequences for skeletal muscle viral susceptibility and myopathies. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020;129:864-867. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00321.2020

21. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public health. 2017;152:157-171.

22. Kathirvel N. Post COVID-19 pandemic mental health challenges. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102430. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102430

23. Macpherson K, Cooper K, Harbour J, et al. Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e050979. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050979

24. Yachou Y, El Idrissi A, Belapasov V, et al. Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neuro Sci. 2020;41:2657-2669. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04575-3

25. Gialluisi A, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. New challenges from Covid-19 pandemic: an unexpected opportunity to enlighten the link between viral infections and brain disorders? Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1349-1350. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04444-z

26. Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027

27. Bisaccia G, Ricci F, Recce V, et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction: what do we know? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8:156. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8110156

28. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

29. Gorna R, MacDermott N, Rayner C, et al. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet. 2021;397:455-457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7

30. Vance H, Maslach A, Stoneman E, et al. Addressing post-COVID symptoms: a guide for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:1229-1242. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210254

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. December 6, 2022. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions. Updated September 1, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html

3. Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022;28:1461-1467. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0

4. Bull-Otterson L, Baca S, Saydah S, et al. Post-COVID conditions among adult COVID-19 survivors aged 18-64 and ≥ 65 years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:713-717. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7121e1

5. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. 2020;370:m3026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026

6. Matta J, Wiernik E, Robineau O, et al; . Association of self-reported COVID-19 infection and SARS-CoV-2 serology test results with persistent physical symptoms among French adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:19-25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.6454

7. FAIR Health. Patients diagnosed with post-COVID conditions: an analysis of private healthcare claims using the official ICD-10 diagnostic code. May 18, 2022. Accessed October 15, 2022. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/whitepaper/asset/Patients%20Diagnosed%20with%20Post-COVID%20Con ditions%20-%20A%20FAIR%20Health%20White%20Paper.pdf

8. Huang L, Li X, Gu X, et al. Health outcomes in people 2 years after surviving hospitalisation with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:863-876. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00126-6

9. Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38:101019. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019

10. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16144. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95565-8

11. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220-232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

12. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;27:626-631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y

13. Dennis A, Wamil M, Alberts J, et al; . Multiorgan impairment in low-risk individuals with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a prospective, community-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048391. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048391

14. Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, et al.. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648

15. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

16. Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PloS One. 2020;15:e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784

17. Wong TL, Weitzer DJ. Long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—a systematic review and comparison of clinical presentation and symptomatology. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:418. doi: 10.3390/ medicina57050418

18. Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N, et al. Post-COVID-19 symptom burden: what is long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung. 2021;199:113-119. doi: 10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z

19. Guedj E, Million M, Dudouet P, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in post-SARS-CoV-2 infection: substrate for persistent/delayed disorders? Euro J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:592-595. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04973-x

20. Ferrandi PJ, Alway SE, Mohamed JS. The interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 may have consequences for skeletal muscle viral susceptibility and myopathies. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020;129:864-867. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00321.2020

21. Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public health. 2017;152:157-171.

22. Kathirvel N. Post COVID-19 pandemic mental health challenges. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102430. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102430

23. Macpherson K, Cooper K, Harbour J, et al. Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e050979. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050979

24. Yachou Y, El Idrissi A, Belapasov V, et al. Neuroinvasion, neurotropic, and neuroinflammatory events of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the neurological manifestations in COVID-19 patients. Neuro Sci. 2020;41:2657-2669. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04575-3

25. Gialluisi A, de Gaetano G, Iacoviello L. New challenges from Covid-19 pandemic: an unexpected opportunity to enlighten the link between viral infections and brain disorders? Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1349-1350. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04444-z

26. Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.027

27. Bisaccia G, Ricci F, Recce V, et al. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 and cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction: what do we know? J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8:156. doi: 10.3390/jcdd8110156

28. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

29. Gorna R, MacDermott N, Rayner C, et al. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet. 2021;397:455-457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7

30. Vance H, Maslach A, Stoneman E, et al. Addressing post-COVID symptoms: a guide for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34:1229-1242. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210254

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Acknowledge and address the persistence of COVID-19 symptoms when meeting with patients. C

› Continue to monitor persistent, fluctuating symptoms of COVID-19 well after hospital discharge or apparent resolution of initial symptoms. C

› Provide psychological support and resources for mental health care to patients regarding their ongoing fears and frustrations with persistent COVID-19 symptoms. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections treatable with newer antibiotics, but guidance is needed

Multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections (MDRGNIs) are an emerging and deadly threat worldwide. Some of these infections are now resistant to nearly all antibiotics, and very few treatment options exist. Some of the remaining antibiotics for these MDRGNIs can cause acute kidney injury and have other toxic effects and can worsen antibiotic resistance. When deciding which drugs to use, clinicians need to juggle the possible lethality of the infection with the dangers of its treatment.

Samuel Windham, MD, and Marin H. Kollef, MD, authors of a recent article in Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, express this urgency. They offer recommendations based on current guidelines and recently published research for treating MDRGNIs with some of the newer antibiotics.

Dr. Kollef, professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an email, “Our recommendations differ in that they offer an approach that is based on disease severity, local resistance prevalence in MDRGNIs, and patient risk factors for infection with MDRGNIs. For patients with severe infection and risk factors for infection with MDRGNIs, we suggest empiric coverage for MDRGNIs until susceptibility data are available or based on rapid molecular testing. Selection of antibiotic therapy would be based on which MDRGNIs predominate locally.”

In their article, the authors discuss how to best utilize the newer antibiotics of ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA), cefiderocol, ceftolozane-tazobactam (C/T), meropenem-vaborbactam (MVB), imipenem-relebactam (I-R), aztreonam-avibactam (ATM-AVI), eravacycline, and plazomicin.

The scope of the problem

Bacterial infections are deadly and are becoming less treatable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2022 that the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed years of decreases in health care–associated infections. Much of the increase has been caused by multidrug-resistant organisms.

In November 2022, authors of an article published in The Lancet estimated worldwide deaths from 33 bacterial genera across 11 infectious syndromes. They found that these infections were the second leading cause of death worldwide in 2019 (ischemic heart disease was the first). Furthermore, they discovered that 54.9% of these deaths were attributable to just five pathogens – Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Three of those five bacterial species – E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa – are gram-negative and are highly prone to drug resistance.

The CDC classified each of those three pathogens as an “urgent threat” in its 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States report. Of particular concern are gram-negative infections that have become resistant to carbapenems, a heavy-hitting class of antibiotics.

Regarding organisms that cause MDRGNIs, known as serine-beta-lactamases (OXA, KPC, and CTX-M) and metallo-beta-lactamases (NDM, VIM, and IMP). Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii also produce carbapenemases, rendering them invulnerable to carbapenem antibiotics.

Traditionally, a common alternative used for carbapenem-resistant infections has been colistin, an older and very toxic antibiotic. The authors cite recent research demonstrating that CZA yields significantly better outcomes with regard to patient mortality and acute kidney injury than colistin and that CZA plus aztreonam can even decrease mortality and length of hospital stay for patients who have bloodstream infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales, which are some of the hardest infections to treat.

“CZA has been demonstrated to have excellent activity against MDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa and KPC Enterobacterales. It should be the preferred agent for use, compared with colistin, for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria susceptible to CZA. Moreover, CZA combined with aztreonam has been shown to be an effective treatment for metallo-beta-lactamase MDRGNIs,” Dr. Kollef said.

Four key recommendations for treating MDRGNIs

The authors base their recommendations, in addition to the recent studies they cite concerning CZA, upon two major guidelines on the treatment of MDRGNIs: the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases’ Guidelines for the Treatment of Infections Caused by Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s (IDSA’s) Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections (multiple documents, found here and here).

Dr. Windham and Dr. Kollef present a table showing the spectrum of activity of the newer antibiotics, as well as an algorithm for decision-making. They summarize their treatment recommendations, which are based upon the bacterial infection cultures or on historical risk (previous infection or colonization history). They encourage empiric treatment if there is an increased risk of death or the presence of shock. By pathogen, they recommend the following:

- For carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, clinicians should treat patients with cefiderocol, ceftazidime-avibactam, imipenem-cilastatin-relabactam, or meropenem-vaborbactam.

- For carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, clinicians should treat patients with cefiderocol, ceftazidime-avibactam, imipenem-cilastatin-relabactam, or ceftolozane-tazobactam.

- For carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii, clinicians should treat patients with a cefiderocol backbone with or without the addition of plazomicin, eravacycline, or other older antibacterials.

- For metallo-beta-lactamase-producing organisms, clinicians should treat patients with cefiderocol, ceftazidime-avibactam, aztreonam, imipenem-cilastatin-relabactam, aztreonam, or aztreonam-avibactam. The authors acknowledge that evidence is limited on treating these infections.

“In general, ceftazidime-avibactam works pretty well in patients with MDRGNIs, and there is no evidence that any of the other new agents is conclusively better in treatment responses. CZA and ceftolozane-tazobactam were the first of the new antibiotics active against highly MDRGN to get approved, and they have been most widely used,” Cornelius “Neil” J. Clancy, MD, chief of the Infectious Diseases Section at the VA Pittsburgh Health Care System, explained. Dr. Clancy was not involved in the Windham-Kollef review article.

“As such, it is not surprising that resistance has emerged and that it has been reported more commonly than for some other agents. The issue of resistance will be considered again as IDSA puts together their update,” Dr. Clancy said.

“The IDSA guidelines are regularly updated. The next updated iteration will be online in early 2023,” said Dr. Clancy, who is also affiliated with IDSA. “Clinical and resistance data that have appeared since the last update in 2022 will be considered as the guidance is put together.”

In general, Dr. Kollef also recommends using a facility’s antibiogram. “They are useful in determining which MDRGN’s predominate locally,” he said.

Dr. Kollef is a consultant for Pfizer, Merck, and Shionogi. Dr. Clancy has received research funding from Merck and from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections (MDRGNIs) are an emerging and deadly threat worldwide. Some of these infections are now resistant to nearly all antibiotics, and very few treatment options exist. Some of the remaining antibiotics for these MDRGNIs can cause acute kidney injury and have other toxic effects and can worsen antibiotic resistance. When deciding which drugs to use, clinicians need to juggle the possible lethality of the infection with the dangers of its treatment.

Samuel Windham, MD, and Marin H. Kollef, MD, authors of a recent article in Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, express this urgency. They offer recommendations based on current guidelines and recently published research for treating MDRGNIs with some of the newer antibiotics.

Dr. Kollef, professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, said in an email, “Our recommendations differ in that they offer an approach that is based on disease severity, local resistance prevalence in MDRGNIs, and patient risk factors for infection with MDRGNIs. For patients with severe infection and risk factors for infection with MDRGNIs, we suggest empiric coverage for MDRGNIs until susceptibility data are available or based on rapid molecular testing. Selection of antibiotic therapy would be based on which MDRGNIs predominate locally.”

In their article, the authors discuss how to best utilize the newer antibiotics of ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA), cefiderocol, ceftolozane-tazobactam (C/T), meropenem-vaborbactam (MVB), imipenem-relebactam (I-R), aztreonam-avibactam (ATM-AVI), eravacycline, and plazomicin.

The scope of the problem

Bacterial infections are deadly and are becoming less treatable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in 2022 that the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed years of decreases in health care–associated infections. Much of the increase has been caused by multidrug-resistant organisms.

In November 2022, authors of an article published in The Lancet estimated worldwide deaths from 33 bacterial genera across 11 infectious syndromes. They found that these infections were the second leading cause of death worldwide in 2019 (ischemic heart disease was the first). Furthermore, they discovered that 54.9% of these deaths were attributable to just five pathogens – Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Three of those five bacterial species – E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa – are gram-negative and are highly prone to drug resistance.