User login

Patient With Severe Headache After IV Immunoglobulin

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

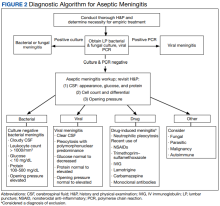

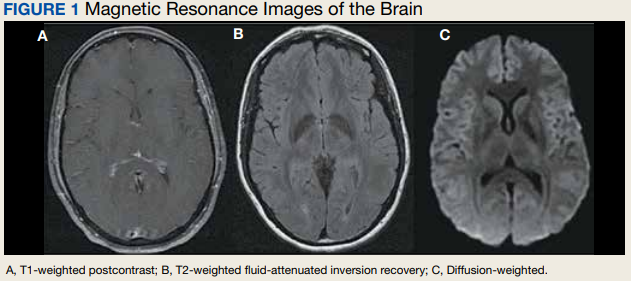

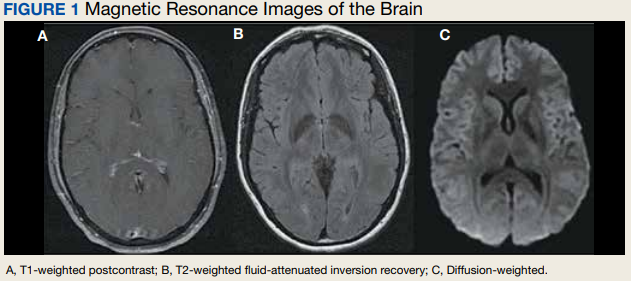

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

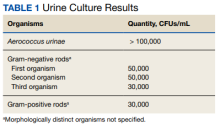

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

Oral Therapy for Aerococcus urinae Bacteremia and Thoracic Spondylodiscitis of Presumed Urinary Origin

Aerococcus urinae (A urinae), a gram-positive coccus readily mistaken for a Staphylococcus species, was first identified in 1992.1-3 It now reportedly accounts for 0.2% to 0.8% of clinical urine isolates.4-6 A urinae bacteriuria is typically asymptomatic and mainly occurs in women.7-9 Symptomatic A urinae urinary tract infection (UTI) occurs predominantly in older men with underlying urologic abnormalities.4-10

Serious A urinae infections are rare. The first 2 reported cases involved men with A urinae endocarditis, one of whom died.11,12 To date, only 8 cases of spondylodiscitis due to A urinae have been reported.13-20 Optimal treatment for invasive A urinae infection is undefined; however, the reported cases were treated successfully with diverse antibiotic regimen combinations; all including a β-lactam and beginning with at least 2 weeks of IV antibiotics.13-20 We describe a man with A urinae bacteremia and spondylodiscitis, presumably arising from a urinary source in the setting of bladder outlet obstruction, who was treated successfully.

Case Presentation

A 74-year-old man with morbid obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, stage 2 chronic kidney disease, and tobacco use presented to the emergency department after 2 weeks of progressive, nonradiating, midthoracic back pain, lower extremity weakness, gait imbalance, fatigue, anorexia, rigors, and subjective fevers. On presentation, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. A physical examination revealed point tenderness of the midthoracic vertebrae, nontender costovertebral angles, diffusely decreased strength, nonsustained clonus in both lower extremities, inguinal intertrigo, and a buried penis with purulent meatal discharge.

Laboratory results indicated a white blood cell (WBC) count of 13.5 K/μL (reference range, 4.0-11.0), absolute neutrophil count of 11.48 K/μL (reference range, 2.0-7.7), C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 225.3 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 5.0), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 85 mm/h (reference range, 5-15), serum blood urea nitrogen of 76 mg/dL (reference range, 8-26), and serum creatinine (SCr) of 1.9 mg/dL (reference range, 1.1-1.4). A urinalysis showed positive leukocyte esterase, WBC clumps, and little bacteria. Abdominal/pelvic computed tomography showed spondylodiscitis-like changes at T7-T8, bilateral perinephric fat stranding, bladder distension, and bladder wall thickening.

The patient was presumed to have discitis secondary to a UTI, with possible pyelonephritis, and was given empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging with contrast supported spondylodiscitis at T7-T8, extending to T8-T9. Preliminary results from the admission blood and urine cultures showed gram-positive cocci in clusters, which were presumed initially to be Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus).

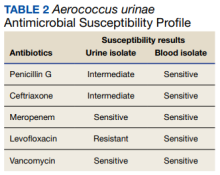

The final urine culture report listed multiple organisms, predominantly A urinae (Table 1);

On hospital day 6, the patient’s back pain had resolved, micturition was normal, appetite had normalized, and SCr was minimally above baseline (1.4 mg/dL). He insisted on completing antibiotic treatment at home and had no other medical indication for continued hospitalization. Thus, antibiotic therapy was changed to an all-oral regimen of amoxicillin 1 g 3 times daily for 10 days and levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 6 weeks, and the patient was discharged to home.

The patient returned 5 days postdischarge due to anuria. Investigation showed severe acute kidney injury (SCr, 6.8 mg/dL) and bladder outlet obstruction due to phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis. Urinalysis was unremarkable. His CRP had declined from 225 mg/L (initial admission) to 154 mg/L. A urinae culture and 2 sets of blood cultures were finalized as no growth. He was diagnosed with postrenal acute kidney injury and underwent meatal dilation and Foley catheterization but declined surgical correction. When seen in the clinic 2 months postantimicrobial therapy, the patient had normal micturition, no symptoms or signs of infection, and steadily down-trending inflammatory markers.

Discussion

A urinae, historically considered a rare pathogen, has been identified with increasing frequency in urine cultures due to improved microbiologic diagnostic techniques. However, there are only 8 reported cases of A urinae spondylodiscitis. Urinary pathology is an accepted risk factor for A urinae infections; consequently, we suspect that our patient’s urinary outflow obstruction and poor genitourinary hygiene were related to his invasive A urinae infection.10,21,22 We surmise that he had a chronic urinary outflow obstruction contributing to his infection, as evidenced by imaging findings, while the phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis were most likely infectious sequelae considering his anuria and acute kidney injury 5 days postdischarge. Indeed, the correlation between A urinae and urinary tract pathology may justify an evaluation for urinary pathology in any man with A urinae infection, regardless of the presence of symptoms.

By contrast, the implications of A urinae bacteriuria remain unclear. From a public health perspective, A urinae bacteriuria is rare, but the infectious mechanism remains undetermined with a case report suggesting the possibility of sexual transmission.4-6,23 In our case, the patient was not sexually active and had no clear origin of infection. Considering the potential severity of infection, more studies are needed to determine the infectious mechanism of A urinae.

In terms of infectious morbidity, the results seem to vary by sex. In a retrospective study of about 30,000 clinical urine samples, 62 (58 from women, 4 from men) yielded A urinae. The 62 corresponding patients lacked systemic infectious complications, leading the authors to conclude that A urinae is a relatively avirulent organism.24 Although possibly true in women, we are wary of drawing conclusions, especially regarding men, from a study that included only 62 urine samples were A urinae–positive, with only 4 from men. More evidence is needed to define the prognostic implications of A urinae bacteriuria in men.

As illustrated by the present case and previous reports, severe A urinae infections can occur, and the contributory factors deserve consideration. In our patient, the actual mechanism for bacteremia remains unclear. The initial concern for acute pyelonephritis was prompted by a computed tomography finding of bilateral perinephric fat stranding. This finding was questioned because it is common in older patients without infection, hence, is highly nonspecific. A correlation with urinary outflow obstruction may be an important clue in cases like this one.25,26

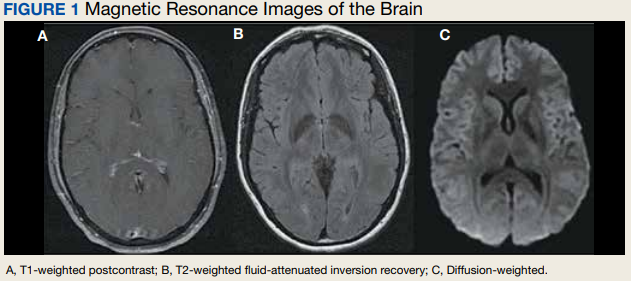

Furthermore, whether the urinary tract truly was the source of the patient’s bacteremia is clouded by the differing antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the A urinae blood and urine isolates. The simplest explanation for this discordance may be that all the isolates shared a common initial origin but adapted to different environments in the host (perhaps over time) or laboratory, producing phenotypic variation. Alternatively, the infection could have been polyclonal from the onset, with sampling error leading to the differing detected susceptibility patterns, or the blood and urine isolates may have represented independent acquisition events, involving distinct A urinae strains. Unfortunately (from an academic perspective), given patient preferences and recommendations from the infectious disease consultant, no bone biopsy was done for histology and culture to confirm infection and to allow comparative strain identification if A urinae was isolated.

Optimal treatment for A urinae spondylodiscitis has yet to be established. β-lactams have shown good clinical efficacy despite being bacteriostatic in vitro.27 Early in vitro studies showed synergistic bactericidal synergistic activity with penicillin plus aminoglycoside combination therapies.27-30 Cases of endocarditis have been successfully treated mainly with the combination of a β-lactam plus aminoglycoside combination therapy.30,31 Previous cases of spondylodiscitis have been treated successfully with diverse antimicrobial agents, including clindamycin, β-lactams, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides.14

Our patient improved rapidly while receiving empiric therapy with vancomycin and ceftriaxone and tolerated a rapid transition to oral amoxicillin and levofloxacin. This is the shortest IV treatment course for A urinae spondylodiscitis reported to date. We suspect that such rapid IV-to-oral transitions will suffice in most stable patients with A urinae spondylodiscitis or other invasive A urinae infections in line with the results of the OVIVA and POET trials.32,33

Conclusions

We believe A urinae UTI in the absence of obvious predisposing factors should prompt evaluation for urinary outflow obstruction. Despite improved laboratory diagnostic techniques, spondylodiscitis related to A urinae remains a rare entity and thus definitive treatment recommendations are difficult to make. However, we suspect that in many cases it is reasonable to extrapolate from the results of the POET and OVIVA trials and rapidly transition therapy of A urinae spondylodiscitis from IV to oral antibiotics. We suspect a review of the US Department of Veterans Affairs population might uncover a higher incidence of A urinae infection than previously estimated due to the population demographics and the epidemiology of A urinae.

1. Christensen JJ, Korner B, Kjaergaard H. Aerococcus-like organism—an unnoticed urinary tract pathogen. APMIS. 1989;97(6):539-546. doi:10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00828.x

2. Aguirre M, Collins MD. Phylogenetic analysis of some Aerococcus-like organisms from urinary tract infections: description of Aerococcus urinae sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138(2):401-405. doi:10.1099/00221287-138-2-401

3. Williams RE, Hirch A, Cowan ST. Aerococcus, a new bacterial genus. J Gen Microbiol. 1953;8(3):475-480. doi:10.1099/00221287-8-3-475

4. Kline KA, Lewis AL. Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012

5. Schuur PM, Kasteren ME, Sabbe L, Vos MC, Janssens MM, Buiting AG. Urinary tract infections with Aerococcus urinae in the south of The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16(12):871-875. doi:10.1007/BF01700552

6. Grude N, Tveten Y. Aerococcus urinae og urinveisinfeksjon [Aerococcus urinae and urinary tract infection]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122(2):174-175.

7. Narayanasamy S, King K, Dennison A, Spelman DW, Aung AK. Clinical characteristics and laboratory identification of Aerococcus infections: an Australian tertiary centre perspective. Int J Microbiol. 2017;2017. doi:10.1155/2017/5684614

8. Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):871-876. doi:10.1128/JCM.02876-13

9. Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio. 2014;5(4):e01283-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01283-14

10. Sahu KK, Lal A, Mishra AK, Abraham GM. Aerococcus-related infections and their significance: a 9-year retrospective study. J Microsc Ultrastruct. 2021;9(1):18-25. doi:10.4103/JMAU.JMAU_61_19

11. Skov RL, Klarlund M, Thorsen S. Fatal endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;21(4):219-221. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(95)00037-b

12. Kristensen B, Nielsen G. Endocarditis caused by Aerococcus urinae, a newly recognized pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14(1):49-51. doi:10.1007/BF02112619

13. Astudillo L, Sailler L, Porte L, Lefevre JC, Massip P, Arlet-Suau E. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae: a first report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(11-12):890-891. doi:10.1080/00365540310016664

14. Lyagoubi A, Souffi C, Baroiller V, Vallee E. Spondylodiscitis: an increasingly described localization. EJIFCC. 2020;31(2):169-173.

15. Jerome M, Slim J, Sison R, Marton R. A case of Aerococcus urinae vertebral osteomyelitis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2015;7(2):85-86. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.157246

16. Tekin A, Tekin G, Turunç T, Demiroğlu Z, Kizilkiliç O. Infective endocarditis and spondylodiscitis in a patient due to Aerococcus urinae: first report. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115(3):402-403. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.046

17. Rougier E, Braud A, Argemi X, et al. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae and literature review. Infection. 2018;46(3):419-421. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1106-0

18. Degroote E, Yildiz H, Lecouvet F, Verroken A, Belkhir L. Aerococcus urinae: an underestimated cause of spine infection? Case report and review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 2018;73(6):444-447. doi:10.1080/17843286.2018.1443003

19. Torres-Martos E, Pérez-Cortés S, Sánchez-Calvo JM, López-Prieto MD. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae infection in an elderly immunocompetent patient. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(10):682-684. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2017.02.005

20. Senneby E, Petersson AC, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of bacteraemia with Aerococcus urinae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(6):546-550. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03609.x

21. Sunnerhagen T, Nilson B, Olaison L, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of infective endocarditis caused by aerococci. Infection. 2016;44(2):167-173. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0812-8

22. de Jong MF, Soetekouw R, ten Kate RW, Veenendaal D. Aerococcus urinae: severe and fatal bloodstream infections and endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(9):3445-3447. doi:10.1128/JCM.00835-10

23. Babaeer AA, Nader C, Iacoviello V, Tomera K. Necrotizing urethritis due to Aerococcus urinae. Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:136147. doi:10.1155/2015/136147

24. Sierra-Hoffman M, Watkins K, Jinadatha C, Fader R, Carpenter JL. Clinical significance of Aerococcus urinae: a retrospective review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53(4):289-292. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.021

25. Fukami H, Takeuchi Y, Kagaya S, et al. Perirenal fat stranding is not a powerful diagnostic tool for acute pyelonephritis. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:137-144. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133685

26. Han NY, Sung DJ, Kim MJ, Park BJ, Sim KC, Cho SB. Perirenal fat stranding on CT: is there an association with bladder outlet obstruction? Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1063):20160195. doi:10.1259/bjr.20160195

27. Hirzel C, Hirzberger L, Furrer H, Endimiani A. Bactericidal activity of penicillin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin and daptomycin alone and in combination against Aerococcus urinae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):271-276. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.007

28. Zbinden R, Santanam P, Hunziker L, Leuzinger B, von Graevenitz A. Endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae: diagnostic tests, fatty acid composition and killing kinetics. Infection. 1999;27(2):122-124. doi:10.1007/BF02560511

29. Skov R, Christensen JJ, Korner B, Frimodt-Møller N, Espersen F. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Aerococcus urinae to 14 antibiotics, and time-kill curves for penicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(5):653-658. doi:10.1093/jac/48.5.653

30. Ebnöther C, Altwegg M, Gottschalk J, Seebach JD, Kronenberg A. Aerococcus urinae endocarditis: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2002;30(5):310-313. doi:10.1007/s15010-002-3106-x

31. Tai DBG, Go JR, Fida M, Saleh OA. Management and treatment of Aerococcus bacteremia and endocarditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:584-589. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.096

32. Li H-K, Rombach I, Zambellas R, et al; OVIVA Trial Collaborators. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):425-436. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710926

33. Iversen K, Ihlemann N, Gill SU, et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):415-424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808312

Aerococcus urinae (A urinae), a gram-positive coccus readily mistaken for a Staphylococcus species, was first identified in 1992.1-3 It now reportedly accounts for 0.2% to 0.8% of clinical urine isolates.4-6 A urinae bacteriuria is typically asymptomatic and mainly occurs in women.7-9 Symptomatic A urinae urinary tract infection (UTI) occurs predominantly in older men with underlying urologic abnormalities.4-10

Serious A urinae infections are rare. The first 2 reported cases involved men with A urinae endocarditis, one of whom died.11,12 To date, only 8 cases of spondylodiscitis due to A urinae have been reported.13-20 Optimal treatment for invasive A urinae infection is undefined; however, the reported cases were treated successfully with diverse antibiotic regimen combinations; all including a β-lactam and beginning with at least 2 weeks of IV antibiotics.13-20 We describe a man with A urinae bacteremia and spondylodiscitis, presumably arising from a urinary source in the setting of bladder outlet obstruction, who was treated successfully.

Case Presentation

A 74-year-old man with morbid obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, stage 2 chronic kidney disease, and tobacco use presented to the emergency department after 2 weeks of progressive, nonradiating, midthoracic back pain, lower extremity weakness, gait imbalance, fatigue, anorexia, rigors, and subjective fevers. On presentation, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. A physical examination revealed point tenderness of the midthoracic vertebrae, nontender costovertebral angles, diffusely decreased strength, nonsustained clonus in both lower extremities, inguinal intertrigo, and a buried penis with purulent meatal discharge.

Laboratory results indicated a white blood cell (WBC) count of 13.5 K/μL (reference range, 4.0-11.0), absolute neutrophil count of 11.48 K/μL (reference range, 2.0-7.7), C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 225.3 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 5.0), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 85 mm/h (reference range, 5-15), serum blood urea nitrogen of 76 mg/dL (reference range, 8-26), and serum creatinine (SCr) of 1.9 mg/dL (reference range, 1.1-1.4). A urinalysis showed positive leukocyte esterase, WBC clumps, and little bacteria. Abdominal/pelvic computed tomography showed spondylodiscitis-like changes at T7-T8, bilateral perinephric fat stranding, bladder distension, and bladder wall thickening.

The patient was presumed to have discitis secondary to a UTI, with possible pyelonephritis, and was given empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging with contrast supported spondylodiscitis at T7-T8, extending to T8-T9. Preliminary results from the admission blood and urine cultures showed gram-positive cocci in clusters, which were presumed initially to be Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus).

The final urine culture report listed multiple organisms, predominantly A urinae (Table 1);

On hospital day 6, the patient’s back pain had resolved, micturition was normal, appetite had normalized, and SCr was minimally above baseline (1.4 mg/dL). He insisted on completing antibiotic treatment at home and had no other medical indication for continued hospitalization. Thus, antibiotic therapy was changed to an all-oral regimen of amoxicillin 1 g 3 times daily for 10 days and levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 6 weeks, and the patient was discharged to home.

The patient returned 5 days postdischarge due to anuria. Investigation showed severe acute kidney injury (SCr, 6.8 mg/dL) and bladder outlet obstruction due to phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis. Urinalysis was unremarkable. His CRP had declined from 225 mg/L (initial admission) to 154 mg/L. A urinae culture and 2 sets of blood cultures were finalized as no growth. He was diagnosed with postrenal acute kidney injury and underwent meatal dilation and Foley catheterization but declined surgical correction. When seen in the clinic 2 months postantimicrobial therapy, the patient had normal micturition, no symptoms or signs of infection, and steadily down-trending inflammatory markers.

Discussion

A urinae, historically considered a rare pathogen, has been identified with increasing frequency in urine cultures due to improved microbiologic diagnostic techniques. However, there are only 8 reported cases of A urinae spondylodiscitis. Urinary pathology is an accepted risk factor for A urinae infections; consequently, we suspect that our patient’s urinary outflow obstruction and poor genitourinary hygiene were related to his invasive A urinae infection.10,21,22 We surmise that he had a chronic urinary outflow obstruction contributing to his infection, as evidenced by imaging findings, while the phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis were most likely infectious sequelae considering his anuria and acute kidney injury 5 days postdischarge. Indeed, the correlation between A urinae and urinary tract pathology may justify an evaluation for urinary pathology in any man with A urinae infection, regardless of the presence of symptoms.

By contrast, the implications of A urinae bacteriuria remain unclear. From a public health perspective, A urinae bacteriuria is rare, but the infectious mechanism remains undetermined with a case report suggesting the possibility of sexual transmission.4-6,23 In our case, the patient was not sexually active and had no clear origin of infection. Considering the potential severity of infection, more studies are needed to determine the infectious mechanism of A urinae.

In terms of infectious morbidity, the results seem to vary by sex. In a retrospective study of about 30,000 clinical urine samples, 62 (58 from women, 4 from men) yielded A urinae. The 62 corresponding patients lacked systemic infectious complications, leading the authors to conclude that A urinae is a relatively avirulent organism.24 Although possibly true in women, we are wary of drawing conclusions, especially regarding men, from a study that included only 62 urine samples were A urinae–positive, with only 4 from men. More evidence is needed to define the prognostic implications of A urinae bacteriuria in men.

As illustrated by the present case and previous reports, severe A urinae infections can occur, and the contributory factors deserve consideration. In our patient, the actual mechanism for bacteremia remains unclear. The initial concern for acute pyelonephritis was prompted by a computed tomography finding of bilateral perinephric fat stranding. This finding was questioned because it is common in older patients without infection, hence, is highly nonspecific. A correlation with urinary outflow obstruction may be an important clue in cases like this one.25,26

Furthermore, whether the urinary tract truly was the source of the patient’s bacteremia is clouded by the differing antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the A urinae blood and urine isolates. The simplest explanation for this discordance may be that all the isolates shared a common initial origin but adapted to different environments in the host (perhaps over time) or laboratory, producing phenotypic variation. Alternatively, the infection could have been polyclonal from the onset, with sampling error leading to the differing detected susceptibility patterns, or the blood and urine isolates may have represented independent acquisition events, involving distinct A urinae strains. Unfortunately (from an academic perspective), given patient preferences and recommendations from the infectious disease consultant, no bone biopsy was done for histology and culture to confirm infection and to allow comparative strain identification if A urinae was isolated.

Optimal treatment for A urinae spondylodiscitis has yet to be established. β-lactams have shown good clinical efficacy despite being bacteriostatic in vitro.27 Early in vitro studies showed synergistic bactericidal synergistic activity with penicillin plus aminoglycoside combination therapies.27-30 Cases of endocarditis have been successfully treated mainly with the combination of a β-lactam plus aminoglycoside combination therapy.30,31 Previous cases of spondylodiscitis have been treated successfully with diverse antimicrobial agents, including clindamycin, β-lactams, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides.14

Our patient improved rapidly while receiving empiric therapy with vancomycin and ceftriaxone and tolerated a rapid transition to oral amoxicillin and levofloxacin. This is the shortest IV treatment course for A urinae spondylodiscitis reported to date. We suspect that such rapid IV-to-oral transitions will suffice in most stable patients with A urinae spondylodiscitis or other invasive A urinae infections in line with the results of the OVIVA and POET trials.32,33

Conclusions

We believe A urinae UTI in the absence of obvious predisposing factors should prompt evaluation for urinary outflow obstruction. Despite improved laboratory diagnostic techniques, spondylodiscitis related to A urinae remains a rare entity and thus definitive treatment recommendations are difficult to make. However, we suspect that in many cases it is reasonable to extrapolate from the results of the POET and OVIVA trials and rapidly transition therapy of A urinae spondylodiscitis from IV to oral antibiotics. We suspect a review of the US Department of Veterans Affairs population might uncover a higher incidence of A urinae infection than previously estimated due to the population demographics and the epidemiology of A urinae.

Aerococcus urinae (A urinae), a gram-positive coccus readily mistaken for a Staphylococcus species, was first identified in 1992.1-3 It now reportedly accounts for 0.2% to 0.8% of clinical urine isolates.4-6 A urinae bacteriuria is typically asymptomatic and mainly occurs in women.7-9 Symptomatic A urinae urinary tract infection (UTI) occurs predominantly in older men with underlying urologic abnormalities.4-10

Serious A urinae infections are rare. The first 2 reported cases involved men with A urinae endocarditis, one of whom died.11,12 To date, only 8 cases of spondylodiscitis due to A urinae have been reported.13-20 Optimal treatment for invasive A urinae infection is undefined; however, the reported cases were treated successfully with diverse antibiotic regimen combinations; all including a β-lactam and beginning with at least 2 weeks of IV antibiotics.13-20 We describe a man with A urinae bacteremia and spondylodiscitis, presumably arising from a urinary source in the setting of bladder outlet obstruction, who was treated successfully.

Case Presentation

A 74-year-old man with morbid obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, stage 2 chronic kidney disease, and tobacco use presented to the emergency department after 2 weeks of progressive, nonradiating, midthoracic back pain, lower extremity weakness, gait imbalance, fatigue, anorexia, rigors, and subjective fevers. On presentation, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. A physical examination revealed point tenderness of the midthoracic vertebrae, nontender costovertebral angles, diffusely decreased strength, nonsustained clonus in both lower extremities, inguinal intertrigo, and a buried penis with purulent meatal discharge.

Laboratory results indicated a white blood cell (WBC) count of 13.5 K/μL (reference range, 4.0-11.0), absolute neutrophil count of 11.48 K/μL (reference range, 2.0-7.7), C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 225.3 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 5.0), erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 85 mm/h (reference range, 5-15), serum blood urea nitrogen of 76 mg/dL (reference range, 8-26), and serum creatinine (SCr) of 1.9 mg/dL (reference range, 1.1-1.4). A urinalysis showed positive leukocyte esterase, WBC clumps, and little bacteria. Abdominal/pelvic computed tomography showed spondylodiscitis-like changes at T7-T8, bilateral perinephric fat stranding, bladder distension, and bladder wall thickening.

The patient was presumed to have discitis secondary to a UTI, with possible pyelonephritis, and was given empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging with contrast supported spondylodiscitis at T7-T8, extending to T8-T9. Preliminary results from the admission blood and urine cultures showed gram-positive cocci in clusters, which were presumed initially to be Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus).

The final urine culture report listed multiple organisms, predominantly A urinae (Table 1);

On hospital day 6, the patient’s back pain had resolved, micturition was normal, appetite had normalized, and SCr was minimally above baseline (1.4 mg/dL). He insisted on completing antibiotic treatment at home and had no other medical indication for continued hospitalization. Thus, antibiotic therapy was changed to an all-oral regimen of amoxicillin 1 g 3 times daily for 10 days and levofloxacin 750 mg daily for 6 weeks, and the patient was discharged to home.

The patient returned 5 days postdischarge due to anuria. Investigation showed severe acute kidney injury (SCr, 6.8 mg/dL) and bladder outlet obstruction due to phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis. Urinalysis was unremarkable. His CRP had declined from 225 mg/L (initial admission) to 154 mg/L. A urinae culture and 2 sets of blood cultures were finalized as no growth. He was diagnosed with postrenal acute kidney injury and underwent meatal dilation and Foley catheterization but declined surgical correction. When seen in the clinic 2 months postantimicrobial therapy, the patient had normal micturition, no symptoms or signs of infection, and steadily down-trending inflammatory markers.

Discussion

A urinae, historically considered a rare pathogen, has been identified with increasing frequency in urine cultures due to improved microbiologic diagnostic techniques. However, there are only 8 reported cases of A urinae spondylodiscitis. Urinary pathology is an accepted risk factor for A urinae infections; consequently, we suspect that our patient’s urinary outflow obstruction and poor genitourinary hygiene were related to his invasive A urinae infection.10,21,22 We surmise that he had a chronic urinary outflow obstruction contributing to his infection, as evidenced by imaging findings, while the phimosis and urethral meatal stenosis were most likely infectious sequelae considering his anuria and acute kidney injury 5 days postdischarge. Indeed, the correlation between A urinae and urinary tract pathology may justify an evaluation for urinary pathology in any man with A urinae infection, regardless of the presence of symptoms.

By contrast, the implications of A urinae bacteriuria remain unclear. From a public health perspective, A urinae bacteriuria is rare, but the infectious mechanism remains undetermined with a case report suggesting the possibility of sexual transmission.4-6,23 In our case, the patient was not sexually active and had no clear origin of infection. Considering the potential severity of infection, more studies are needed to determine the infectious mechanism of A urinae.

In terms of infectious morbidity, the results seem to vary by sex. In a retrospective study of about 30,000 clinical urine samples, 62 (58 from women, 4 from men) yielded A urinae. The 62 corresponding patients lacked systemic infectious complications, leading the authors to conclude that A urinae is a relatively avirulent organism.24 Although possibly true in women, we are wary of drawing conclusions, especially regarding men, from a study that included only 62 urine samples were A urinae–positive, with only 4 from men. More evidence is needed to define the prognostic implications of A urinae bacteriuria in men.

As illustrated by the present case and previous reports, severe A urinae infections can occur, and the contributory factors deserve consideration. In our patient, the actual mechanism for bacteremia remains unclear. The initial concern for acute pyelonephritis was prompted by a computed tomography finding of bilateral perinephric fat stranding. This finding was questioned because it is common in older patients without infection, hence, is highly nonspecific. A correlation with urinary outflow obstruction may be an important clue in cases like this one.25,26

Furthermore, whether the urinary tract truly was the source of the patient’s bacteremia is clouded by the differing antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the A urinae blood and urine isolates. The simplest explanation for this discordance may be that all the isolates shared a common initial origin but adapted to different environments in the host (perhaps over time) or laboratory, producing phenotypic variation. Alternatively, the infection could have been polyclonal from the onset, with sampling error leading to the differing detected susceptibility patterns, or the blood and urine isolates may have represented independent acquisition events, involving distinct A urinae strains. Unfortunately (from an academic perspective), given patient preferences and recommendations from the infectious disease consultant, no bone biopsy was done for histology and culture to confirm infection and to allow comparative strain identification if A urinae was isolated.

Optimal treatment for A urinae spondylodiscitis has yet to be established. β-lactams have shown good clinical efficacy despite being bacteriostatic in vitro.27 Early in vitro studies showed synergistic bactericidal synergistic activity with penicillin plus aminoglycoside combination therapies.27-30 Cases of endocarditis have been successfully treated mainly with the combination of a β-lactam plus aminoglycoside combination therapy.30,31 Previous cases of spondylodiscitis have been treated successfully with diverse antimicrobial agents, including clindamycin, β-lactams, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and aminoglycosides.14

Our patient improved rapidly while receiving empiric therapy with vancomycin and ceftriaxone and tolerated a rapid transition to oral amoxicillin and levofloxacin. This is the shortest IV treatment course for A urinae spondylodiscitis reported to date. We suspect that such rapid IV-to-oral transitions will suffice in most stable patients with A urinae spondylodiscitis or other invasive A urinae infections in line with the results of the OVIVA and POET trials.32,33

Conclusions

We believe A urinae UTI in the absence of obvious predisposing factors should prompt evaluation for urinary outflow obstruction. Despite improved laboratory diagnostic techniques, spondylodiscitis related to A urinae remains a rare entity and thus definitive treatment recommendations are difficult to make. However, we suspect that in many cases it is reasonable to extrapolate from the results of the POET and OVIVA trials and rapidly transition therapy of A urinae spondylodiscitis from IV to oral antibiotics. We suspect a review of the US Department of Veterans Affairs population might uncover a higher incidence of A urinae infection than previously estimated due to the population demographics and the epidemiology of A urinae.

1. Christensen JJ, Korner B, Kjaergaard H. Aerococcus-like organism—an unnoticed urinary tract pathogen. APMIS. 1989;97(6):539-546. doi:10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00828.x

2. Aguirre M, Collins MD. Phylogenetic analysis of some Aerococcus-like organisms from urinary tract infections: description of Aerococcus urinae sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138(2):401-405. doi:10.1099/00221287-138-2-401

3. Williams RE, Hirch A, Cowan ST. Aerococcus, a new bacterial genus. J Gen Microbiol. 1953;8(3):475-480. doi:10.1099/00221287-8-3-475

4. Kline KA, Lewis AL. Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012

5. Schuur PM, Kasteren ME, Sabbe L, Vos MC, Janssens MM, Buiting AG. Urinary tract infections with Aerococcus urinae in the south of The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16(12):871-875. doi:10.1007/BF01700552

6. Grude N, Tveten Y. Aerococcus urinae og urinveisinfeksjon [Aerococcus urinae and urinary tract infection]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122(2):174-175.

7. Narayanasamy S, King K, Dennison A, Spelman DW, Aung AK. Clinical characteristics and laboratory identification of Aerococcus infections: an Australian tertiary centre perspective. Int J Microbiol. 2017;2017. doi:10.1155/2017/5684614

8. Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):871-876. doi:10.1128/JCM.02876-13

9. Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio. 2014;5(4):e01283-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01283-14

10. Sahu KK, Lal A, Mishra AK, Abraham GM. Aerococcus-related infections and their significance: a 9-year retrospective study. J Microsc Ultrastruct. 2021;9(1):18-25. doi:10.4103/JMAU.JMAU_61_19

11. Skov RL, Klarlund M, Thorsen S. Fatal endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;21(4):219-221. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(95)00037-b

12. Kristensen B, Nielsen G. Endocarditis caused by Aerococcus urinae, a newly recognized pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14(1):49-51. doi:10.1007/BF02112619

13. Astudillo L, Sailler L, Porte L, Lefevre JC, Massip P, Arlet-Suau E. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae: a first report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(11-12):890-891. doi:10.1080/00365540310016664

14. Lyagoubi A, Souffi C, Baroiller V, Vallee E. Spondylodiscitis: an increasingly described localization. EJIFCC. 2020;31(2):169-173.

15. Jerome M, Slim J, Sison R, Marton R. A case of Aerococcus urinae vertebral osteomyelitis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2015;7(2):85-86. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.157246

16. Tekin A, Tekin G, Turunç T, Demiroğlu Z, Kizilkiliç O. Infective endocarditis and spondylodiscitis in a patient due to Aerococcus urinae: first report. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115(3):402-403. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.046

17. Rougier E, Braud A, Argemi X, et al. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae and literature review. Infection. 2018;46(3):419-421. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1106-0

18. Degroote E, Yildiz H, Lecouvet F, Verroken A, Belkhir L. Aerococcus urinae: an underestimated cause of spine infection? Case report and review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 2018;73(6):444-447. doi:10.1080/17843286.2018.1443003

19. Torres-Martos E, Pérez-Cortés S, Sánchez-Calvo JM, López-Prieto MD. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae infection in an elderly immunocompetent patient. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(10):682-684. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2017.02.005

20. Senneby E, Petersson AC, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of bacteraemia with Aerococcus urinae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(6):546-550. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03609.x

21. Sunnerhagen T, Nilson B, Olaison L, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of infective endocarditis caused by aerococci. Infection. 2016;44(2):167-173. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0812-8

22. de Jong MF, Soetekouw R, ten Kate RW, Veenendaal D. Aerococcus urinae: severe and fatal bloodstream infections and endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(9):3445-3447. doi:10.1128/JCM.00835-10

23. Babaeer AA, Nader C, Iacoviello V, Tomera K. Necrotizing urethritis due to Aerococcus urinae. Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:136147. doi:10.1155/2015/136147

24. Sierra-Hoffman M, Watkins K, Jinadatha C, Fader R, Carpenter JL. Clinical significance of Aerococcus urinae: a retrospective review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53(4):289-292. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.021

25. Fukami H, Takeuchi Y, Kagaya S, et al. Perirenal fat stranding is not a powerful diagnostic tool for acute pyelonephritis. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:137-144. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133685

26. Han NY, Sung DJ, Kim MJ, Park BJ, Sim KC, Cho SB. Perirenal fat stranding on CT: is there an association with bladder outlet obstruction? Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1063):20160195. doi:10.1259/bjr.20160195

27. Hirzel C, Hirzberger L, Furrer H, Endimiani A. Bactericidal activity of penicillin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin and daptomycin alone and in combination against Aerococcus urinae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):271-276. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.007

28. Zbinden R, Santanam P, Hunziker L, Leuzinger B, von Graevenitz A. Endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae: diagnostic tests, fatty acid composition and killing kinetics. Infection. 1999;27(2):122-124. doi:10.1007/BF02560511

29. Skov R, Christensen JJ, Korner B, Frimodt-Møller N, Espersen F. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Aerococcus urinae to 14 antibiotics, and time-kill curves for penicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(5):653-658. doi:10.1093/jac/48.5.653

30. Ebnöther C, Altwegg M, Gottschalk J, Seebach JD, Kronenberg A. Aerococcus urinae endocarditis: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2002;30(5):310-313. doi:10.1007/s15010-002-3106-x

31. Tai DBG, Go JR, Fida M, Saleh OA. Management and treatment of Aerococcus bacteremia and endocarditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:584-589. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.096

32. Li H-K, Rombach I, Zambellas R, et al; OVIVA Trial Collaborators. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):425-436. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710926

33. Iversen K, Ihlemann N, Gill SU, et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):415-424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808312

1. Christensen JJ, Korner B, Kjaergaard H. Aerococcus-like organism—an unnoticed urinary tract pathogen. APMIS. 1989;97(6):539-546. doi:10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00828.x

2. Aguirre M, Collins MD. Phylogenetic analysis of some Aerococcus-like organisms from urinary tract infections: description of Aerococcus urinae sp. nov. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138(2):401-405. doi:10.1099/00221287-138-2-401

3. Williams RE, Hirch A, Cowan ST. Aerococcus, a new bacterial genus. J Gen Microbiol. 1953;8(3):475-480. doi:10.1099/00221287-8-3-475

4. Kline KA, Lewis AL. Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012

5. Schuur PM, Kasteren ME, Sabbe L, Vos MC, Janssens MM, Buiting AG. Urinary tract infections with Aerococcus urinae in the south of The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16(12):871-875. doi:10.1007/BF01700552

6. Grude N, Tveten Y. Aerococcus urinae og urinveisinfeksjon [Aerococcus urinae and urinary tract infection]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122(2):174-175.

7. Narayanasamy S, King K, Dennison A, Spelman DW, Aung AK. Clinical characteristics and laboratory identification of Aerococcus infections: an Australian tertiary centre perspective. Int J Microbiol. 2017;2017. doi:10.1155/2017/5684614

8. Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, et al. Urine is not sterile: use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):871-876. doi:10.1128/JCM.02876-13

9. Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio. 2014;5(4):e01283-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01283-14

10. Sahu KK, Lal A, Mishra AK, Abraham GM. Aerococcus-related infections and their significance: a 9-year retrospective study. J Microsc Ultrastruct. 2021;9(1):18-25. doi:10.4103/JMAU.JMAU_61_19

11. Skov RL, Klarlund M, Thorsen S. Fatal endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;21(4):219-221. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(95)00037-b

12. Kristensen B, Nielsen G. Endocarditis caused by Aerococcus urinae, a newly recognized pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14(1):49-51. doi:10.1007/BF02112619

13. Astudillo L, Sailler L, Porte L, Lefevre JC, Massip P, Arlet-Suau E. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae: a first report. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(11-12):890-891. doi:10.1080/00365540310016664

14. Lyagoubi A, Souffi C, Baroiller V, Vallee E. Spondylodiscitis: an increasingly described localization. EJIFCC. 2020;31(2):169-173.

15. Jerome M, Slim J, Sison R, Marton R. A case of Aerococcus urinae vertebral osteomyelitis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2015;7(2):85-86. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.157246

16. Tekin A, Tekin G, Turunç T, Demiroğlu Z, Kizilkiliç O. Infective endocarditis and spondylodiscitis in a patient due to Aerococcus urinae: first report. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115(3):402-403. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.01.046

17. Rougier E, Braud A, Argemi X, et al. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae and literature review. Infection. 2018;46(3):419-421. doi:10.1007/s15010-017-1106-0

18. Degroote E, Yildiz H, Lecouvet F, Verroken A, Belkhir L. Aerococcus urinae: an underestimated cause of spine infection? Case report and review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 2018;73(6):444-447. doi:10.1080/17843286.2018.1443003

19. Torres-Martos E, Pérez-Cortés S, Sánchez-Calvo JM, López-Prieto MD. Spondylodiscitis due to Aerococcus urinae infection in an elderly immunocompetent patient. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35(10):682-684. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2017.02.005

20. Senneby E, Petersson AC, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of bacteraemia with Aerococcus urinae. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(6):546-550. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03609.x

21. Sunnerhagen T, Nilson B, Olaison L, Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of infective endocarditis caused by aerococci. Infection. 2016;44(2):167-173. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0812-8

22. de Jong MF, Soetekouw R, ten Kate RW, Veenendaal D. Aerococcus urinae: severe and fatal bloodstream infections and endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(9):3445-3447. doi:10.1128/JCM.00835-10

23. Babaeer AA, Nader C, Iacoviello V, Tomera K. Necrotizing urethritis due to Aerococcus urinae. Case Rep Urol. 2015;2015:136147. doi:10.1155/2015/136147

24. Sierra-Hoffman M, Watkins K, Jinadatha C, Fader R, Carpenter JL. Clinical significance of Aerococcus urinae: a retrospective review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;53(4):289-292. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.021

25. Fukami H, Takeuchi Y, Kagaya S, et al. Perirenal fat stranding is not a powerful diagnostic tool for acute pyelonephritis. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:137-144. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S133685

26. Han NY, Sung DJ, Kim MJ, Park BJ, Sim KC, Cho SB. Perirenal fat stranding on CT: is there an association with bladder outlet obstruction? Br J Radiol. 2016;89(1063):20160195. doi:10.1259/bjr.20160195

27. Hirzel C, Hirzberger L, Furrer H, Endimiani A. Bactericidal activity of penicillin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin and daptomycin alone and in combination against Aerococcus urinae. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48(3):271-276. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.007

28. Zbinden R, Santanam P, Hunziker L, Leuzinger B, von Graevenitz A. Endocarditis due to Aerococcus urinae: diagnostic tests, fatty acid composition and killing kinetics. Infection. 1999;27(2):122-124. doi:10.1007/BF02560511

29. Skov R, Christensen JJ, Korner B, Frimodt-Møller N, Espersen F. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Aerococcus urinae to 14 antibiotics, and time-kill curves for penicillin, gentamicin and vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(5):653-658. doi:10.1093/jac/48.5.653

30. Ebnöther C, Altwegg M, Gottschalk J, Seebach JD, Kronenberg A. Aerococcus urinae endocarditis: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2002;30(5):310-313. doi:10.1007/s15010-002-3106-x

31. Tai DBG, Go JR, Fida M, Saleh OA. Management and treatment of Aerococcus bacteremia and endocarditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:584-589. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.096

32. Li H-K, Rombach I, Zambellas R, et al; OVIVA Trial Collaborators. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):425-436. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710926

33. Iversen K, Ihlemann N, Gill SU, et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):415-424. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808312

HIV vaccine trial makes pivotal leap toward making ‘super antibodies’

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The announcement comes from the journal Science, which published phase 1 results of a small clinical trial for a vaccine technology that aims to cause the body to create a rare kind of cell.

“At the most general level, the trial results show that one can design vaccines that induce antibodies with prespecified genetic features, and this may herald a new era of precision vaccines,” William Schief, PhD, a researcher at the Scripps Research Institute and study coauthor, told the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The study was the first to test the approach in humans and was effective in 97% – or 35 of 36 – participants. The vaccine technology is called “germline targeting.” Trial results show that “one can design a vaccine that elicits made-to-order antibodies in humans,” Dr. Schief said in a news release.

In addition to possibly being a breakthrough for the treatment of HIV, the vaccine technology could also impact the development of treatments for flu, hepatitis C, and coronaviruses, study authors wrote.

There is no cure for HIV, but there are treatments to manage how the disease progresses. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, destroys white blood cells, and increases susceptibility to other infections, AAAS summarized. More than 1 million people in the United States and 38 million people worldwide have HIV.

Previous HIV vaccine attempts were not able to cause the production of specialized cells known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies,” CNN reported.

“Call them super antibodies, if you want,” University of Minnesota HIV researcher Timothy Schacker, MD, who was not involved in the research, told CNN. “The hope is that if you can induce this kind of immunity in people, you can protect them from some of these viruses that we’ve had a very hard time designing vaccines for that are effective. So this is an important step forward.”

Study authors said this is just the first step in the multiphase vaccine design, which so far is a theory. Further study is needed to see if the next steps also work in humans, and then if all the steps can be linked together and can be effective against HIV.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

CAB-LA’s full potential for HIV prevention hits snags

, say authors of a new review article.

CAB-LA “represents the most important breakthrough in HIV prevention in recent years,” write Geoffroy Liegeon, MD, and Jade Ghosn, MD, PhD, with Université Paris Cité, in this month’s HIV Medicine.

It has been found to be safe, and more effective in phase 3 trials than oral PrEP, and is well-accepted in men who have sex with men, and transgender and cisgender women.

Reductions in stigma

Surveys show patients at high risk for HIV – especially those who see PrEP as burdensome – are highly interested in long-acting injectable drugs. Reduced stigma with the injections also appears to steer the choice toward a long-acting agent and may attract more people to HIV prevention programs.

The first two injections are given 4 weeks apart, followed by an injection every 8 weeks.

Models designed to increase uptake, adherence, and persistence when on and after discontinuing CAB-LA will be important for wider rollout, as will better patient education and demonstrated efficacy and safety in populations not included in clinical trials, Dr. Liegeon and Dr. Ghosn note.

Still, they point out that its broader integration into clinical routine is held back by factors including breakthrough infections despite timely injections, complexity of follow-up, logistical considerations, and its cost-effectiveness compared with oral PrEP.

A hefty price tag

“[T]he cost effectiveness compared with TDF-FTC [tenofovir/emtricitabine] generics may not support its use at the current price in many settings,” the authors write.

For low- and middle-income countries, the TDF/FTC price is about $55, according to the World Health Organization’s Global Price Reporting, while the current price of CAB-LA in the United States is about $22,000, according to Dr. Ghosn. He said in an interview that because the cost of generics can reach $400-$500 per year in the United States, depending on the pharmaceutical companies, the price for CAB-LA is almost 60 times higher than TDF/FTC in the Untied States.

The biggest hope for the price reduction, at least in lower-income countries, he said, is a new licensing agreement.

ViiV Healthcare signed a new voluntary licensing agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool in July to help access in low-income, lower-middle-income, and sub-Saharan African countries, he explained.

The authors summarize: “[E]stablishing the effectiveness of CAB-LA does not guarantee its uptake into clinical routine.”

Because of the combined issues, the WHO recommended CAB-LA as an additional prevention choice for PrEP in its recent guidelines, pending further studies.

Barriers frustrate providers

Lauren Fontana, DO, assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and infectious disease physician at M Health Fairview, said in an interview that “as a health care provider, cost and insurance barriers can be frustrating, especially when CAB-LA is identified as the best option for a patient.”

Lack of nonphysician-led initiatives, such as nurse- or pharmacy-led services for CAB-LA, may limit availability to marginalized and at-risk populations, she said.

“If a clinic can acquire CAB-LA, clinic protocols need to be developed and considerations of missed visits and doses must be thought about when implementing a program,” Dr. Fontana said.

Clinics need resources to engage with patients to promote retention in the program with case management and pharmacy support, she added.

“Simplification processes need to be developed to make CAB-LA an option for more clinics and patients,” she continued. “We are still learning about the incidence of breakthrough HIV infections, patterns of HIV seroconversion, and how to optimize testing so that HIV infections are detected early.”

Dr. Liegeon, Dr. Ghosn, and Dr. Fontana report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, say authors of a new review article.

CAB-LA “represents the most important breakthrough in HIV prevention in recent years,” write Geoffroy Liegeon, MD, and Jade Ghosn, MD, PhD, with Université Paris Cité, in this month’s HIV Medicine.