User login

How to have a safer and more joyful holiday season

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

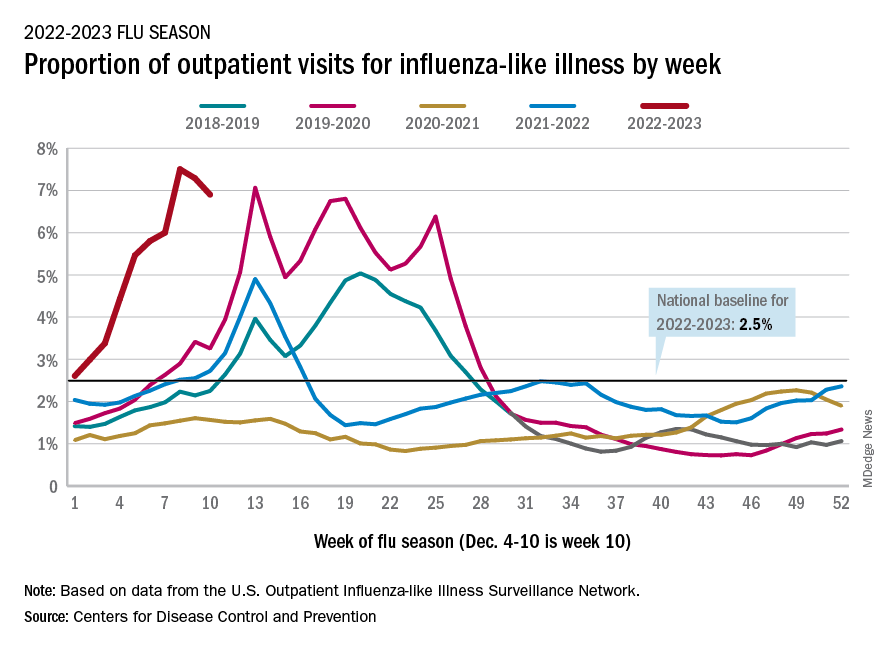

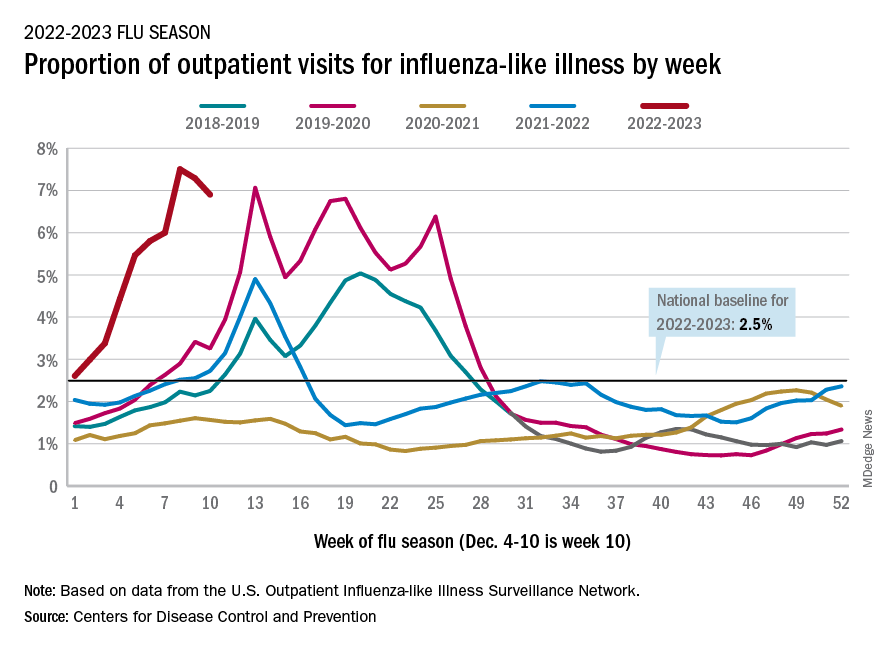

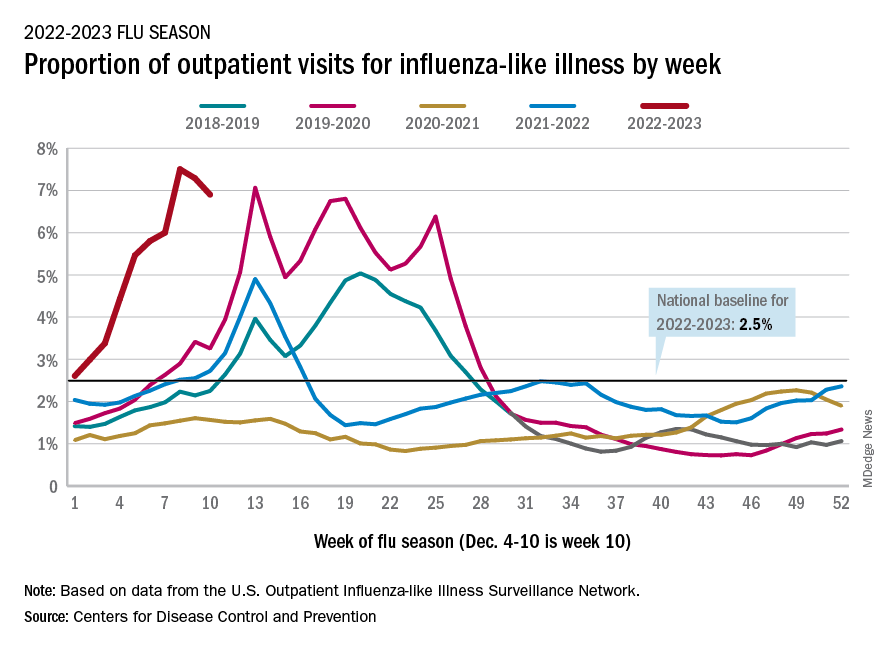

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

This holiday season, I am looking forward to spending some time with family, as I have in the past. As I have chatted with others, many friends are looking forward to events that are potentially larger and potentially returning to prepandemic type gatherings.

Gathering is important and can bring joy, sense of community, and love to the lives of many. Unfortunately, the risks associated with gathering are not over. as our country faces many cases of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), COVID-19, and influenza at the same time.

During the first week of December, cases of influenza were rising across the country1 and were rising faster than in previous years. Although getting the vaccine is an important method of influenza prevention and is recommended for everyone over the age of 6 months with rare exception, many have not gotten their vaccine this year.

Influenza

Thus far, “nearly 50% of reported flu-associated hospitalizations in women of childbearing age have been in women who are pregnant.” We are seeing this at a time with lower-than-average uptake of influenza vaccine leaving both the pregnant persons and their babies unprotected. In addition to utilizing vaccines as prevention, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and practicing good hand hygiene can all decrease transmission.

RSV

In addition to rises of influenza, there are currently high rates of RSV in various parts of the country. Prior to 2020, RSV typically started in the fall and peaked in the winter months. However, since the pandemic, the typical seasonal pattern has not returned, and it is unclear when it will. Although RSV hits the very young, the old, and the immunocompromised the most, RSV can infect anyone. Unfortunately, we do not currently have a vaccine for everyone against this virus. Prevention of transmission includes, as with flu, isolating when ill, cleaning surfaces, and washing hands.2

COVID-19

Of course, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also still here as well. During the first week of December, the CDC reported rising cases of COVID across the country. Within the past few months, there have been several developments, though, for protection. There are now bivalent vaccines available as either third doses or booster doses approved for all persons over 6 months of age. As of the first week of December, only 13.5% of those aged 5 and over had received an updated booster.

There is currently wider access to rapid testing, including at-home testing, which can allow individuals to identify if COVID positive. Additionally, there is access to medication to decrease the likelihood of severe disease – though this does not take the place of vaccinations.

If anyone does test positive for COVID, they should follow the most recent quarantine guidelines including wearing a well-fitted mask when they do begin returning to activities.3

With rising cases of all three of these viruses, some may be asking how we can safely gather. There are several things to consider and do to enjoy our events. The first thing everyone can do is to receive updated vaccinations for both influenza and COVID-19 if eligible. Although it may take some time to be effective, vaccination is still one of our most effective methods of disease prevention and is important this winter season. Vaccinations can also help decrease the risk of severe disease.

Although many have stopped masking, as cases rise, it is time to consider masking particularly when community levels of any of these viruses are high. Masks help with preventing and spreading more than just COVID-19. Using them can be especially important for those going places such as stores and to large public gatherings and when riding on buses, planes, or trains.

In summary

Preventing exposure by masking can help keep individuals healthy prior to celebrating the holidays with others. With access to rapid testing, it makes sense to consider testing prior to gathering with friends and family. Most importantly, although we all are looking forward to spending time with our loved ones, it is important to stay home if not feeling well. Following these recommendations will allow us to have a safer and more joyful holiday season.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center and program director of Northwestern University’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, both in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Influenza (flu). [Online] Dec. 1, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/flu/index.htm.

2. Respiratory syncytial virus. Respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV). [Online] Oct. 28, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/index.html.

3. COVID-19. [Online] Dec. 7, 2022. [Cited: 2022 Dec 10.] https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html.

Ohio measles outbreak grows, fueled by vaccine hesitancy

The Ohio measles outbreak continues to expand, with cases now totaling 81 – a 37% increase in the course of just 2 weeks.

. Most of the children infected were unvaccinated but were old enough to get the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) shot, which is 97% effective at preventing measles.

“I think these are individuals who are making a decision not to protect their children against vaccine-preventable diseases, and some of them are making a specific decision not to use the MMR vaccine,” Columbus Public Health Commissioner Mysheika W. Roberts, MD, told JAMA.

She said that parents’ refusal to vaccinate their children was due to a misconception that the vaccine causes autism.

“We’re sounding the alarm that if your child is of age and not vaccinated, they should get vaccinated ASAP,” Dr. Roberts said, noting that she hasn’t seen that happening more.

Health officials have predicted the outbreak, which started in November, will last at least several months. Measles is so contagious that 9 out of 10 unvaccinated people in a room will become infected if exposed.

All of the infections have been in children. According to the Columbus Public Health measles dashboard, of the 81 confirmed cases:

- 29 children have been hospitalized.

- 22 cases are among children under 1 year old.

- No deaths have been reported.

Dr. Roberts said the hospitalized children have had symptoms including dehydration, diarrhea, and pneumonia. Some have had to go to the intensive care unit.

Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, and even death, the CDC says.

One of the most recent cases was an infant too young to be vaccinated who lives 45 miles away from where the outbreak began, the Dayton Daily News reported. That’s the first case in Clark County in more than 20 years. At least 10% of kindergartners’ parents in the region’s elementary schools opted out of vaccines because of religious or moral objections.

“We knew this was coming. It was a matter of when, not if,” Yamini Teegala, MD, chief medical officer at Rocking Horse Community Health Center in Springfield, told the Dayton Daily News.

This is the second measles outbreak this year. Minnesota tallied 22 cases since June in an unrelated outbreak, JAMA reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Ohio measles outbreak continues to expand, with cases now totaling 81 – a 37% increase in the course of just 2 weeks.

. Most of the children infected were unvaccinated but were old enough to get the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) shot, which is 97% effective at preventing measles.

“I think these are individuals who are making a decision not to protect their children against vaccine-preventable diseases, and some of them are making a specific decision not to use the MMR vaccine,” Columbus Public Health Commissioner Mysheika W. Roberts, MD, told JAMA.

She said that parents’ refusal to vaccinate their children was due to a misconception that the vaccine causes autism.

“We’re sounding the alarm that if your child is of age and not vaccinated, they should get vaccinated ASAP,” Dr. Roberts said, noting that she hasn’t seen that happening more.

Health officials have predicted the outbreak, which started in November, will last at least several months. Measles is so contagious that 9 out of 10 unvaccinated people in a room will become infected if exposed.

All of the infections have been in children. According to the Columbus Public Health measles dashboard, of the 81 confirmed cases:

- 29 children have been hospitalized.

- 22 cases are among children under 1 year old.

- No deaths have been reported.

Dr. Roberts said the hospitalized children have had symptoms including dehydration, diarrhea, and pneumonia. Some have had to go to the intensive care unit.

Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, and even death, the CDC says.

One of the most recent cases was an infant too young to be vaccinated who lives 45 miles away from where the outbreak began, the Dayton Daily News reported. That’s the first case in Clark County in more than 20 years. At least 10% of kindergartners’ parents in the region’s elementary schools opted out of vaccines because of religious or moral objections.

“We knew this was coming. It was a matter of when, not if,” Yamini Teegala, MD, chief medical officer at Rocking Horse Community Health Center in Springfield, told the Dayton Daily News.

This is the second measles outbreak this year. Minnesota tallied 22 cases since June in an unrelated outbreak, JAMA reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Ohio measles outbreak continues to expand, with cases now totaling 81 – a 37% increase in the course of just 2 weeks.

. Most of the children infected were unvaccinated but were old enough to get the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) shot, which is 97% effective at preventing measles.

“I think these are individuals who are making a decision not to protect their children against vaccine-preventable diseases, and some of them are making a specific decision not to use the MMR vaccine,” Columbus Public Health Commissioner Mysheika W. Roberts, MD, told JAMA.

She said that parents’ refusal to vaccinate their children was due to a misconception that the vaccine causes autism.

“We’re sounding the alarm that if your child is of age and not vaccinated, they should get vaccinated ASAP,” Dr. Roberts said, noting that she hasn’t seen that happening more.

Health officials have predicted the outbreak, which started in November, will last at least several months. Measles is so contagious that 9 out of 10 unvaccinated people in a room will become infected if exposed.

All of the infections have been in children. According to the Columbus Public Health measles dashboard, of the 81 confirmed cases:

- 29 children have been hospitalized.

- 22 cases are among children under 1 year old.

- No deaths have been reported.

Dr. Roberts said the hospitalized children have had symptoms including dehydration, diarrhea, and pneumonia. Some have had to go to the intensive care unit.

Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, and even death, the CDC says.

One of the most recent cases was an infant too young to be vaccinated who lives 45 miles away from where the outbreak began, the Dayton Daily News reported. That’s the first case in Clark County in more than 20 years. At least 10% of kindergartners’ parents in the region’s elementary schools opted out of vaccines because of religious or moral objections.

“We knew this was coming. It was a matter of when, not if,” Yamini Teegala, MD, chief medical officer at Rocking Horse Community Health Center in Springfield, told the Dayton Daily News.

This is the second measles outbreak this year. Minnesota tallied 22 cases since June in an unrelated outbreak, JAMA reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA

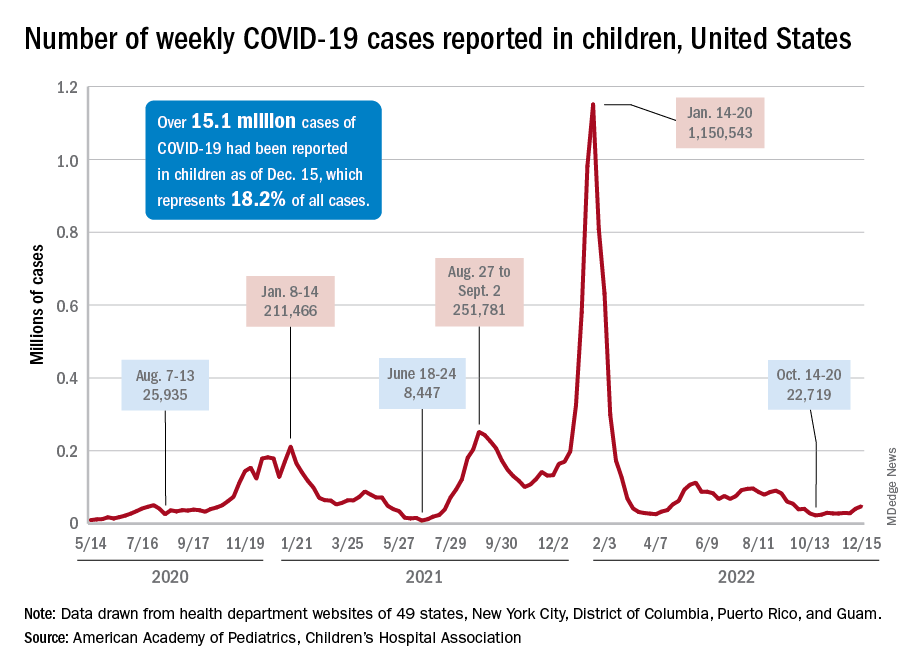

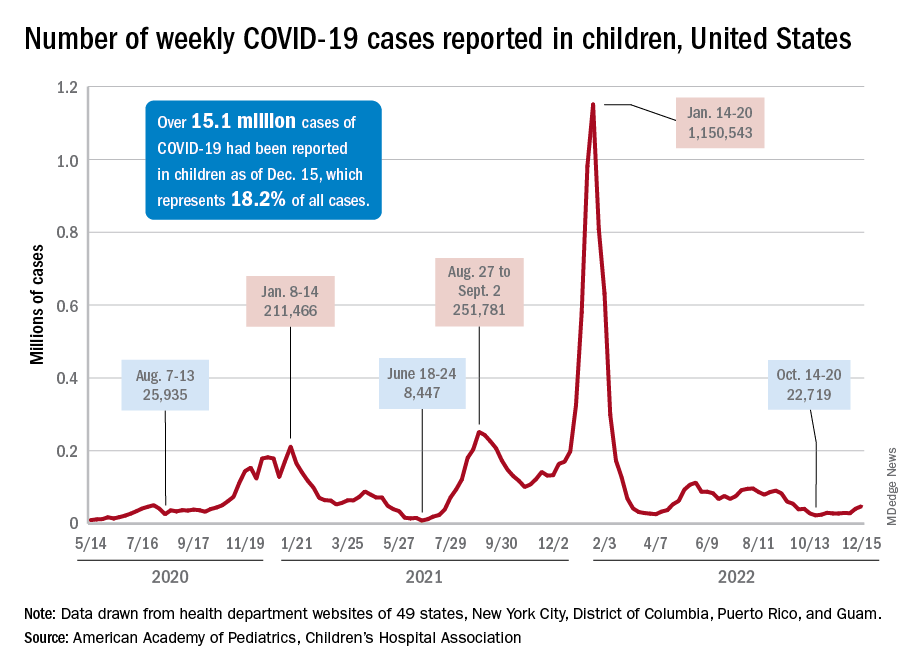

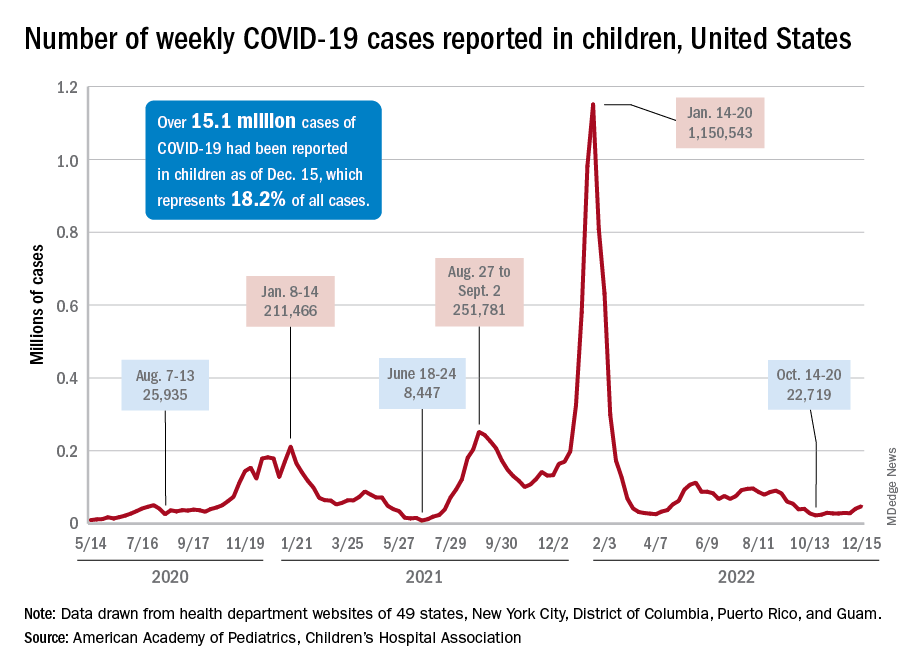

Children and COVID: New-case counts offer dueling narratives

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

Vaccinating pregnant women protects infants against severe RSV infection

An investigational vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in pregnant women has been shown to help protect infants against severe disease, according to the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Pfizer recently announced that in the course of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, the vaccine RSVpreF had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life, according to a company press release.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. A total of 7,400 women had received a single dose of 120 mcg RSVpreF in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Due to the good results, the enrollment in the study was halted on the recommendation of the study’s Data Monitoring Committee after achieving a primary endpoint. The company plans to apply for marketing authorization to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration by the end of 2022 and to other regulatory agencies in 2023.

“The directness of the strategy, to vaccinate expectant mothers during pregnancy so that their newborn is then later protected, is new and a very interesting approach,” commented Prof. Ortwin Adams, MD, head of virologic diagnostics at the Institute for Virology of the University Hospital of Düsseldorf (Germany) to the Science Media Centre (SMC).

In terms of the RSV vaccination strategy presented, “the unborn child has taken center stage from the outset.” Because the vaccination route is the placental transfer of antibodies from mother to child (“passive immunity”), “... the medical points of contact for this vaccination will be the gynecologists, not the pediatricians,” Dr. Adams said.

“This concept imitates the natural process, since the mother normally passes immune defenses she acquired through infections to the child via the umbilical cord and her breast milk before and after birth. This procedure is long-proven and practiced worldwide, especially in nonindustrialized countries, for a variety of diseases, including tetanus, whooping cough (pertussis), and viral flu (influenza),” explained Markus Rose, MD, PhD, head of Pediatric Pulmonology at the Olgahospital, Stuttgart, Germany.

The development of an RSV vaccine had ground to a halt for many decades: A tragedy in the 1960s set the whole field of research back. Using the model of the first polio vaccine, scientists had manufactured an experimental vaccine with inactivated viruses. However, tests showed that the vaccine did not protect the children vaccinated, but it actually infected them with RSV, they then fell ill, and two children died. Today, potential RSV vaccines are first tested on adults and not on children.

Few treatment options

RSV causes seasonal epidemics, can lead to bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants, and is one of the main causes of hospital stays in young children. Monoclonal antibodies are currently the only preventive option, since there is still no vaccine. Usually, 60%-70% of infants and nearly all children younger than 2 years are infected with RSV, but the virus can also trigger pneumonia in adults.

“RSV infections constitute a major public health challenge: It is the most dangerous respiratory virus for young infants, it is also a threat to the chronically ill and immunocompromised of all ages, and [it] is the second most common cause of death worldwide (after malaria) in young children,” stated Dr. Rose.

Recently, pandemic-related measures (face masks, more intense disinfection) meant that the “normal” RSV infections in healthy adults, which usually progress like a mild cold, were prevented, and mothers were unable to pass on as much RSV immune defense to their children. “This was presumably responsible in part for the massive wave of RSV infections in fall and winter of 2021/22,” explained Dr. Rose.

Thomas Mertens, MD, PhD, chair of the Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute (STIKO) and former director of the Institute for Virology at Ulm University Hospital, Germany, also noted: “It would be an important and potentially achievable goal to significantly reduce the incidence rate of hospitalizations. In this respect, RSV poses a significant problem for young children, their parents, and the burden on pediatric clinics.”

Final evaluation pending

“I am definitely finding the data interesting, but the original data are needed,” Dr. Mertens said. Once the data are published at a conference or published in a peer-reviewed journal, physicians will be able to better judge the data for themselves, he said.

Dr. Rose characterized the new vaccine as “novel,” including in terms of its composition. Earlier RSV vaccines used the so-called postfusion F protein as their starting point. But it has become known in the meantime that the key to immunogenicity is the continued prefusion state of the apical epitope: Prefusion F-specific memory B cells in adults naturally infected with RSV produce potent neutralizing antibodies.

The new vaccine is bivalent and protects against both RSV A and RSV B.

To date, RSV vaccination directly in young infants have had only had a weak efficacy and were sometimes poorly tolerated. The vaccine presented here is expected to be tested in young adults first, then in school children, then young children.

Through successful vaccination of the entire population, the transfer of RS viruses to young children could be prevented. “To what extent this, or any other RSV vaccine still to be developed on the same basis, will also be effective and well tolerated in young infants is still difficult to assess,” said Dr. Rose.

Dr. Mertens emphasized that all of the study data now needs to be seen as quickly as possible: “This is also a general requirement for transparency from the pharmaceutical companies, which is also rightly criticized.”

This article was originally published in Medscape’s German edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

An investigational vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in pregnant women has been shown to help protect infants against severe disease, according to the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Pfizer recently announced that in the course of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, the vaccine RSVpreF had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life, according to a company press release.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. A total of 7,400 women had received a single dose of 120 mcg RSVpreF in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Due to the good results, the enrollment in the study was halted on the recommendation of the study’s Data Monitoring Committee after achieving a primary endpoint. The company plans to apply for marketing authorization to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration by the end of 2022 and to other regulatory agencies in 2023.

“The directness of the strategy, to vaccinate expectant mothers during pregnancy so that their newborn is then later protected, is new and a very interesting approach,” commented Prof. Ortwin Adams, MD, head of virologic diagnostics at the Institute for Virology of the University Hospital of Düsseldorf (Germany) to the Science Media Centre (SMC).

In terms of the RSV vaccination strategy presented, “the unborn child has taken center stage from the outset.” Because the vaccination route is the placental transfer of antibodies from mother to child (“passive immunity”), “... the medical points of contact for this vaccination will be the gynecologists, not the pediatricians,” Dr. Adams said.

“This concept imitates the natural process, since the mother normally passes immune defenses she acquired through infections to the child via the umbilical cord and her breast milk before and after birth. This procedure is long-proven and practiced worldwide, especially in nonindustrialized countries, for a variety of diseases, including tetanus, whooping cough (pertussis), and viral flu (influenza),” explained Markus Rose, MD, PhD, head of Pediatric Pulmonology at the Olgahospital, Stuttgart, Germany.

The development of an RSV vaccine had ground to a halt for many decades: A tragedy in the 1960s set the whole field of research back. Using the model of the first polio vaccine, scientists had manufactured an experimental vaccine with inactivated viruses. However, tests showed that the vaccine did not protect the children vaccinated, but it actually infected them with RSV, they then fell ill, and two children died. Today, potential RSV vaccines are first tested on adults and not on children.

Few treatment options

RSV causes seasonal epidemics, can lead to bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants, and is one of the main causes of hospital stays in young children. Monoclonal antibodies are currently the only preventive option, since there is still no vaccine. Usually, 60%-70% of infants and nearly all children younger than 2 years are infected with RSV, but the virus can also trigger pneumonia in adults.

“RSV infections constitute a major public health challenge: It is the most dangerous respiratory virus for young infants, it is also a threat to the chronically ill and immunocompromised of all ages, and [it] is the second most common cause of death worldwide (after malaria) in young children,” stated Dr. Rose.

Recently, pandemic-related measures (face masks, more intense disinfection) meant that the “normal” RSV infections in healthy adults, which usually progress like a mild cold, were prevented, and mothers were unable to pass on as much RSV immune defense to their children. “This was presumably responsible in part for the massive wave of RSV infections in fall and winter of 2021/22,” explained Dr. Rose.

Thomas Mertens, MD, PhD, chair of the Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute (STIKO) and former director of the Institute for Virology at Ulm University Hospital, Germany, also noted: “It would be an important and potentially achievable goal to significantly reduce the incidence rate of hospitalizations. In this respect, RSV poses a significant problem for young children, their parents, and the burden on pediatric clinics.”

Final evaluation pending

“I am definitely finding the data interesting, but the original data are needed,” Dr. Mertens said. Once the data are published at a conference or published in a peer-reviewed journal, physicians will be able to better judge the data for themselves, he said.

Dr. Rose characterized the new vaccine as “novel,” including in terms of its composition. Earlier RSV vaccines used the so-called postfusion F protein as their starting point. But it has become known in the meantime that the key to immunogenicity is the continued prefusion state of the apical epitope: Prefusion F-specific memory B cells in adults naturally infected with RSV produce potent neutralizing antibodies.

The new vaccine is bivalent and protects against both RSV A and RSV B.

To date, RSV vaccination directly in young infants have had only had a weak efficacy and were sometimes poorly tolerated. The vaccine presented here is expected to be tested in young adults first, then in school children, then young children.

Through successful vaccination of the entire population, the transfer of RS viruses to young children could be prevented. “To what extent this, or any other RSV vaccine still to be developed on the same basis, will also be effective and well tolerated in young infants is still difficult to assess,” said Dr. Rose.

Dr. Mertens emphasized that all of the study data now needs to be seen as quickly as possible: “This is also a general requirement for transparency from the pharmaceutical companies, which is also rightly criticized.”

This article was originally published in Medscape’s German edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

An investigational vaccine against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in pregnant women has been shown to help protect infants against severe disease, according to the vaccine’s manufacturer.

Pfizer recently announced that in the course of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study, the vaccine RSVpreF had an almost 82% efficacy against severe RSV infection in infants from birth through the first 90 days of life, according to a company press release.

The vaccine also had a 69% efficacy against severe disease through the first 6 months of life. A total of 7,400 women had received a single dose of 120 mcg RSVpreF in the late second or third trimester of their pregnancy. There were no signs of safety issues for the mothers or infants.

Due to the good results, the enrollment in the study was halted on the recommendation of the study’s Data Monitoring Committee after achieving a primary endpoint. The company plans to apply for marketing authorization to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration by the end of 2022 and to other regulatory agencies in 2023.

“The directness of the strategy, to vaccinate expectant mothers during pregnancy so that their newborn is then later protected, is new and a very interesting approach,” commented Prof. Ortwin Adams, MD, head of virologic diagnostics at the Institute for Virology of the University Hospital of Düsseldorf (Germany) to the Science Media Centre (SMC).

In terms of the RSV vaccination strategy presented, “the unborn child has taken center stage from the outset.” Because the vaccination route is the placental transfer of antibodies from mother to child (“passive immunity”), “... the medical points of contact for this vaccination will be the gynecologists, not the pediatricians,” Dr. Adams said.

“This concept imitates the natural process, since the mother normally passes immune defenses she acquired through infections to the child via the umbilical cord and her breast milk before and after birth. This procedure is long-proven and practiced worldwide, especially in nonindustrialized countries, for a variety of diseases, including tetanus, whooping cough (pertussis), and viral flu (influenza),” explained Markus Rose, MD, PhD, head of Pediatric Pulmonology at the Olgahospital, Stuttgart, Germany.

The development of an RSV vaccine had ground to a halt for many decades: A tragedy in the 1960s set the whole field of research back. Using the model of the first polio vaccine, scientists had manufactured an experimental vaccine with inactivated viruses. However, tests showed that the vaccine did not protect the children vaccinated, but it actually infected them with RSV, they then fell ill, and two children died. Today, potential RSV vaccines are first tested on adults and not on children.

Few treatment options

RSV causes seasonal epidemics, can lead to bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants, and is one of the main causes of hospital stays in young children. Monoclonal antibodies are currently the only preventive option, since there is still no vaccine. Usually, 60%-70% of infants and nearly all children younger than 2 years are infected with RSV, but the virus can also trigger pneumonia in adults.

“RSV infections constitute a major public health challenge: It is the most dangerous respiratory virus for young infants, it is also a threat to the chronically ill and immunocompromised of all ages, and [it] is the second most common cause of death worldwide (after malaria) in young children,” stated Dr. Rose.

Recently, pandemic-related measures (face masks, more intense disinfection) meant that the “normal” RSV infections in healthy adults, which usually progress like a mild cold, were prevented, and mothers were unable to pass on as much RSV immune defense to their children. “This was presumably responsible in part for the massive wave of RSV infections in fall and winter of 2021/22,” explained Dr. Rose.

Thomas Mertens, MD, PhD, chair of the Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute (STIKO) and former director of the Institute for Virology at Ulm University Hospital, Germany, also noted: “It would be an important and potentially achievable goal to significantly reduce the incidence rate of hospitalizations. In this respect, RSV poses a significant problem for young children, their parents, and the burden on pediatric clinics.”

Final evaluation pending

“I am definitely finding the data interesting, but the original data are needed,” Dr. Mertens said. Once the data are published at a conference or published in a peer-reviewed journal, physicians will be able to better judge the data for themselves, he said.

Dr. Rose characterized the new vaccine as “novel,” including in terms of its composition. Earlier RSV vaccines used the so-called postfusion F protein as their starting point. But it has become known in the meantime that the key to immunogenicity is the continued prefusion state of the apical epitope: Prefusion F-specific memory B cells in adults naturally infected with RSV produce potent neutralizing antibodies.

The new vaccine is bivalent and protects against both RSV A and RSV B.

To date, RSV vaccination directly in young infants have had only had a weak efficacy and were sometimes poorly tolerated. The vaccine presented here is expected to be tested in young adults first, then in school children, then young children.

Through successful vaccination of the entire population, the transfer of RS viruses to young children could be prevented. “To what extent this, or any other RSV vaccine still to be developed on the same basis, will also be effective and well tolerated in young infants is still difficult to assess,” said Dr. Rose.

Dr. Mertens emphasized that all of the study data now needs to be seen as quickly as possible: “This is also a general requirement for transparency from the pharmaceutical companies, which is also rightly criticized.”

This article was originally published in Medscape’s German edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

Systematic review supports preferred drugs for HIV in youths

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL AIDS SOCIETY

Scientists use mRNA technology for universal flu vaccine

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

COVID booster shot poll: People ‘don’t think they need one’

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Now, a new poll shows why so few people are willing to roll up their sleeves again.

The most common reasons people give for not getting the latest booster shot is that they “don’t think they need one” (44%) and they “don’t think the benefits are worth it” (37%), according to poll results from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The data comes amid announcements by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that boosters reduced COVID-19 hospitalizations by up to 57% for U.S. adults and by up to 84% for people age 65 and older. Those figures are just the latest in a mountain of research reporting the public health benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

Despite all of the statistical data, health officials’ recent vaccination campaigns have proven far from compelling.

So far, just 15% of people age 12 and older have gotten the latest booster, and 36% of people age 65 and older have gotten it, the CDC’s vaccination trackershows.

Since the start of the pandemic, 1.1 million people in the U.S. have died from COVID-19, with the number of deaths currently rising by 400 per day, The New York Times COVID tracker shows.

Many experts continue to note the need for everyone to get booster shots regularly, but some advocate that perhaps a change in strategy is in order.

“What the administration should do is push for vaccinating people in high-risk groups, including those who are older, those who are immunocompromised and those who have comorbidities,” Paul Offitt, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told CNN.

Federal regulators have announced they will meet Jan. 26 with a panel of vaccine advisors to examine the current recommended vaccination schedule as well as look at the effectiveness and composition of current vaccines and boosters, with an eye toward the make-up of next-generation shots.

Vaccines are the “best available protection” against hospitalization and death caused by COVID-19, said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement announcing the planned meeting.

“Since the initial authorizations of these vaccines, we have learned that protection wanes over time, especially as the virus rapidly mutates and new variants and subvariants emerge,” he said. “Therefore, it’s important to continue discussions about the optimal composition of COVID-19 vaccines for primary and booster vaccination, as well as the optimal interval for booster vaccination.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

40-year-old woman • fever • rash • arthralgia • Dx?

THE CASE