User login

FDA approves congenital CMV diagnostic test

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

Acute flaccid myelitis has unique MRI features

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) initially presents subtly, complicating its diagnosis. Children present with a rapid onset of weakness that is associated with a febrile illness, which can be respiratory, gastrointestinal, or with symptoms of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Given the lack of effective treatments, early diagnosis and monitoring are essential for mitigating the risk of respiratory decline and long-term complications.

While patient history and physical examination can provide clues to the presence of AFM, confirming the diagnosis requires lumbar puncture and MRI of the spinal cord. On MRI, diagnostic confirmation will come from findings of longitudinal, butterfly-shaped, anterior horn–predominant T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities of the central gray matter.

Patients with suspected AFM should be hospitalized because they can rapidly deteriorate to the point of respiratory compromise, particularly those with upper extremity and bulbar weakness.

Sarah E. Hopkins, MD, is from the division of neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, is from the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Kevin Messacar, MD, is from the department of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital Colorado. These comments are taken from an accompanying viewpoint (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4896). Dr. Messacar reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious and Dr. Hopkins reported support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

Acute flaccid myelitis appears to present most commonly as asymmetric weakness after respiratory viral infection and has distinctive MRI features that could help with early diagnosis.

In a paper published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers presented the results of a retrospective case series of 45 children who were diagnosed between 2012 and 2016 with acute flaccid myelitis, or “pseudo polio,” using the Centers for Disease Control’s case definition.

Matthew J. Elrick, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his coauthors came up with a set of reproducible and distinctive features of acute flaccid myelitis. These were the presence of a prodromal fever or viral syndrome; weakness in a lower motor neuron pattern involving one or more limbs, neck, face, and/or bulbar muscles; supportive evidence either from MRI, nerve conduction studies, or cerebrospinal fluid; and the absence of objective sensory deficits, supratentorial white matter, cortical lesions greater than 1 cm in size, encephalopathy, elevated cerebrospinal fluid without pleocytosis, or any other alternative diagnosis.

The researchers commented that, while the CDC case definition has helped with epidemiologic surveillance of acute flaccid myelitis, it may also pick up children with acute weakness caused by other conditions such as transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, ischemic myelopathy, and other myelopathies.

To identify clinical features that might help differentiate patients with acute flaccid myelitis, the researchers attempted to see how many alternative diagnoses were captured in the CDC case definition.

The patients in their study all presented with acute flaccid paralysis in at least one limb and with either an MRI showing a spinal cord lesion spanning one or more spinal segments but largely restricted to gray matter or pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid. The researchers divided the cases into those who also met a well-defined alternative diagnosis – who they categorized as “acute flaccid myelitis with possible alternative diagnosis” (AFM-ad) – and those who were categorized as “restrictively defined AFM” (rAFM). Overall, 34 patients were classified as rAFM and 11 as AFM-ad.

Those in the rAFD group nearly all had asymmetric onset of symptoms, while those in the AFM-ad group were more likely to experience bilateral onset in their lower extremities, “reflecting the pattern of symptoms often seen in other causes of myelopathy such as transverse myelitis and ischemic injury,” the authors noted.

While both groups often presented with decreased muscle tone and reflexes, this was more likely to evolve to increased tone or hyperreflexia in the AFM-ad group. Patients with AFM-ad were also more likely to experience impaired bowel or bladder function.

On MRI, lesions were mostly or completely restricted to the spinal cord gray matter in patients with rAFM or to involve the dorsal pons. These patients did not have any supratentorial brain lesions.

Patients in the rAFM category also had lower cerebrospinal fluid protein values than those in the AFM-ad category, but this was the only cerebrospinal fluid difference between the two groups.

All patients categorized as having rAFM had an infectious prodrome – such as viral syndrome, fever, congestion, and cough – compared with 63.6% of the patients categorized as AFM-ad. The pathogen was identified in only 13 of the rAFM patients, and included 5 patients with enterovirus D68, 2 with unspecified enterovirus, 2 with rhinovirus, 2 with adenovirus, and 2 with mycoplasma. Of the three patients in the AFM-ad group whose pathogen was identified, one had an untyped rhinovirus/enterovirus and mycoplasma, one had a rhinovirus B, and one had enterovirus D68.

“These results highlight that the CDC case definition, while appropriately sensitive for epidemiologic ascertainment of possible AFM cases, also encompasses other neurologic diseases that can cause acute weakness,” the authors wrote. However, they acknowledged that acute flaccid myelitis was still poorly understood and their own definition of the disease may change as more children are diagnosed.

“We propose that the definition of rAFM presented here be used as a starting point for developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for future research studies of AFM,” they wrote.

The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

SOURCE: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Acute flaccid myelitis has distinct features that can distinguish it from other similar conditions.

Major finding: Asymmetric onset of symptoms and MRI signature can help distinguish acute flaccid myelitis from alternative diagnoses.

Study details: A retrospective case series in 45 children diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Johns Hopkins University, the Bart McLean Fund for Neuroimmunology Research, and Project Restore. Two authors reported funding from private industry outside the submitted work and five reported support from or involvement with research and funding bodies.

Source: Elrick MJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 30. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4890.

DRESS Syndrome Induced by Telaprevir: A Potentially Fatal Adverse Event in Chronic Hepatitis C Therapy

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

Practice Points

- DRESS syndrome is characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests.

- Severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages; in the third and fourth stages, adequate patient monitoring is necessary.

- Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. Its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

Eumycetoma Pedis in an Albanian Farmer

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

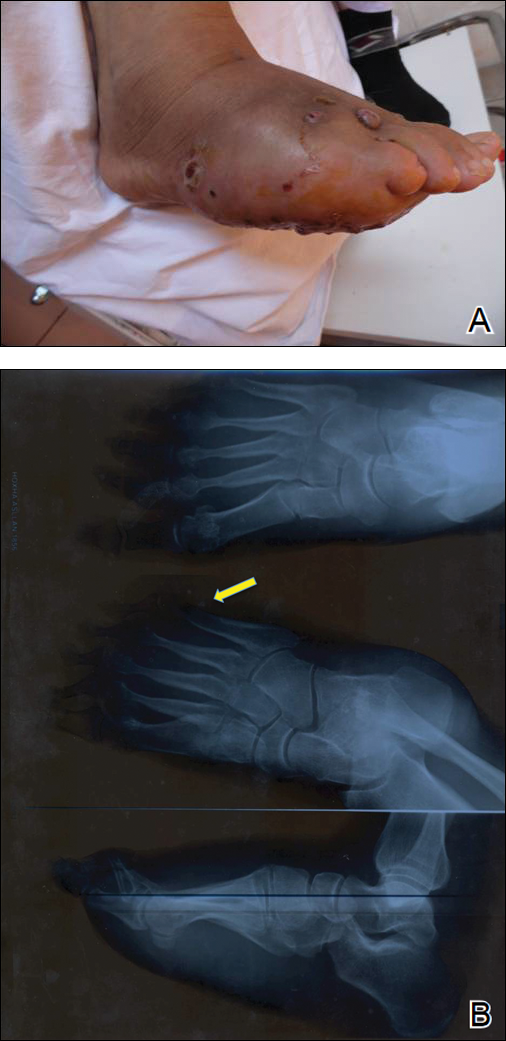

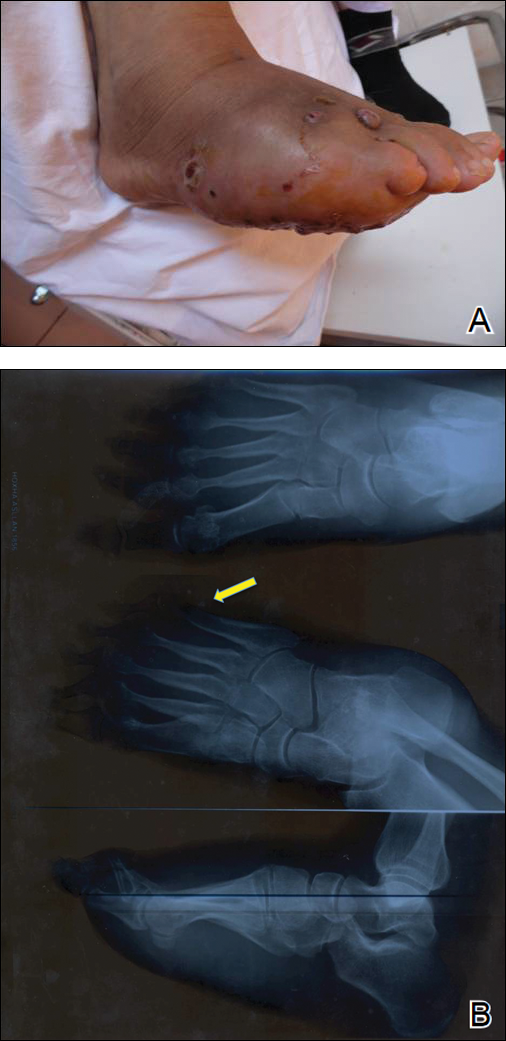

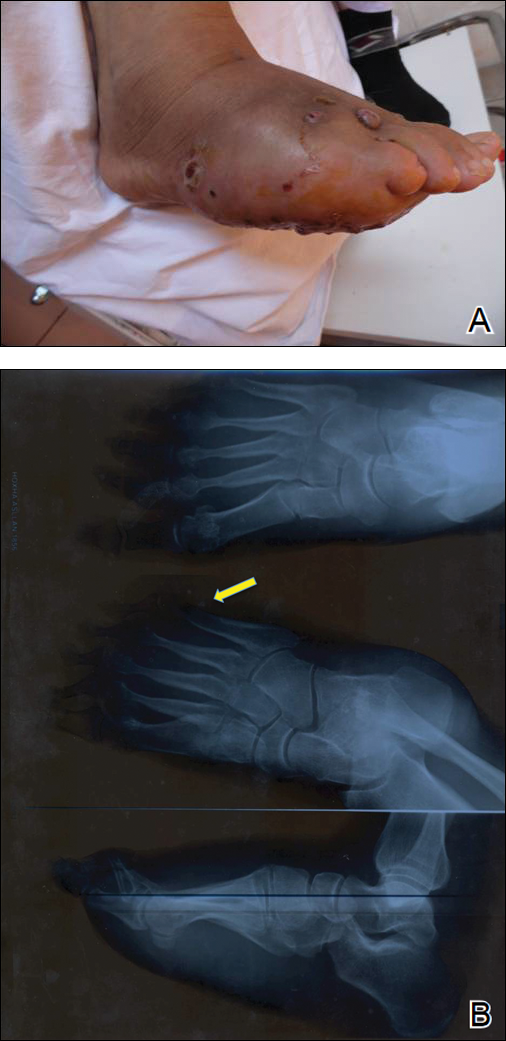

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

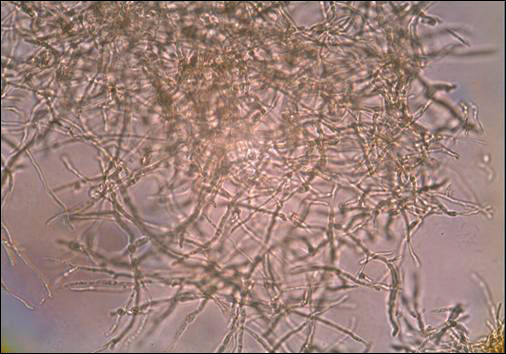

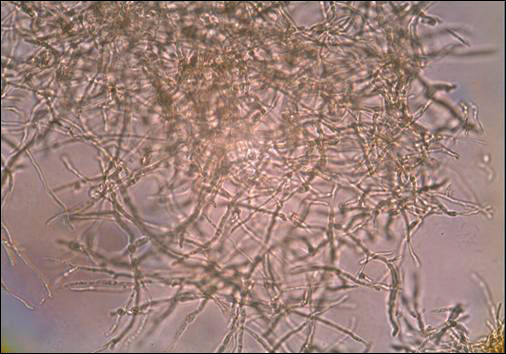

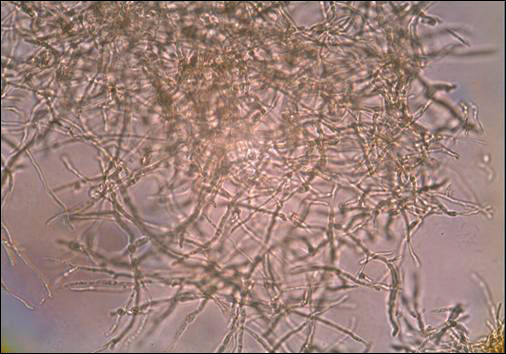

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

Practice Points

- A critical step in the diagnosis of mycetomas is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma.

- Potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify fungal infection.

- Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat and require a combined strategy including systemic treatment and surgical therapy.

HIV prevention: Mandating insurance coverage of PrEP

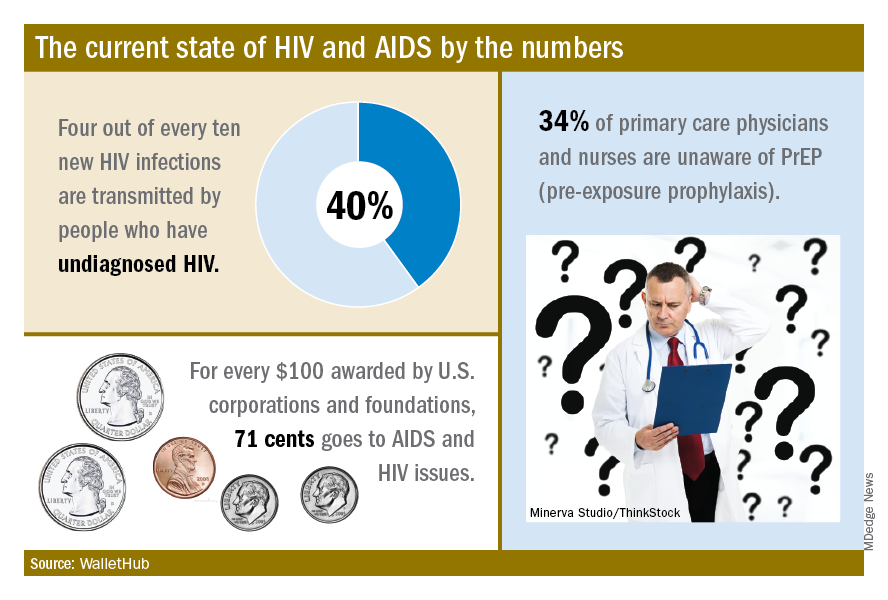

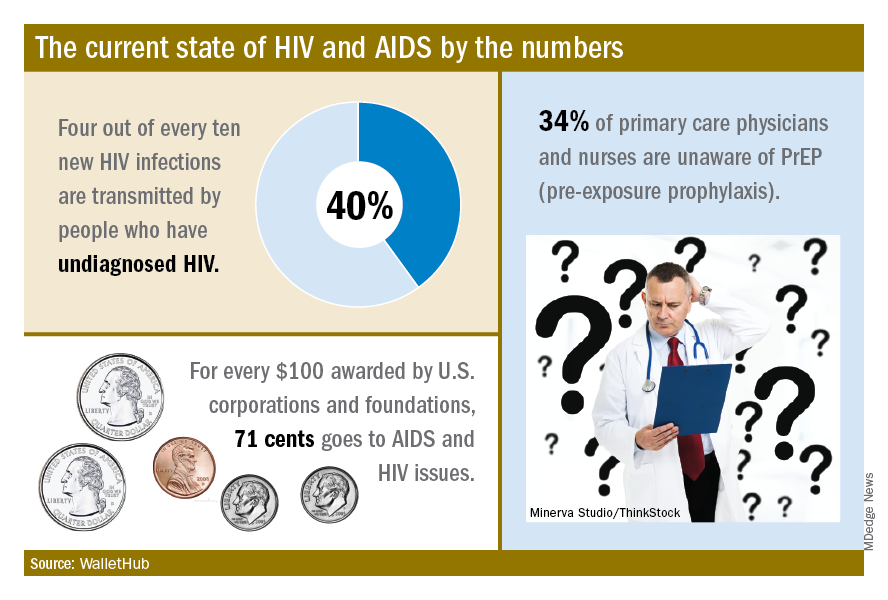

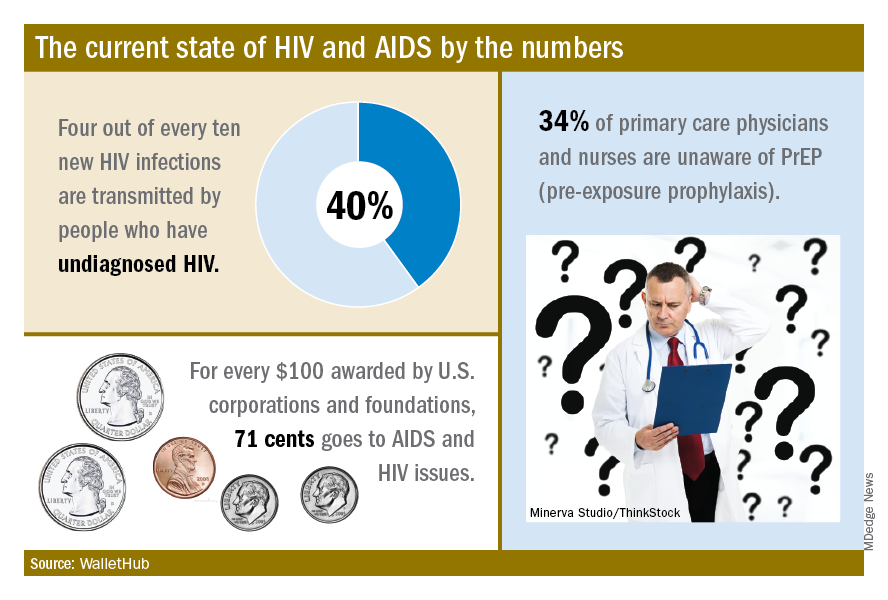

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is valuable enough for the federal government to mandate insurance coverage, a group of experts told the personal finance website WalletHub, but individuals who are at risk for infection may be missing out for other reasons.

The effectiveness of PrEP is clear, those experts said, but 34% of primary care physicians and nurses in the United States are unaware of the preventive regimen, according to the WalletHub report, which also noted that the majority of Americans with AIDS (61%) are not seeing a specialist.

“Even among [men who have sex with men] in the U.S., coverage is only about 10%, which is abysmal. We can and need to do better. If we don’t pay now, we’ll pay later,” Steffanie Strathdee, PhD, associate dean of global health sciences and Harold Simon Professor at the University of California, San Diego, told WalletHub.

Those taking PrEP have a 90% chance of avoiding HIV infection, the report noted.

“Making PrEP available to all is a giant step forward in the fight against HIV. Mandating this critical prevention be covered by all insurance plans makes it part of mainstream medicine and will only increase its use and help prevent HIV acquisition in exposed populations. I can’t think of other low-risk, high-reward prophylaxis for a lifelong disease,” said Sharon Nachman, MD, professor of pediatrics and associate dean for research at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

To get PrEP covered, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force needs to act, explained Gerald M. Oppenheimer, PhD, MPH, of the department of health policy and management at the City University of New York.

“Under the Affordable Care Act, if the [USPSTF] finds that PrEP serves as an effective prevention to disease and gives it a grade of A or B, all insurers must offer it free. That, of course, may lead to an increase in premiums. This is another example of pharmaceutical companies charging high prices in the U.S., compared to what other countries pay, and cries out for an amendment to Medicare Part D, allowing the federal government to negotiate lower drug prices,” he said.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is valuable enough for the federal government to mandate insurance coverage, a group of experts told the personal finance website WalletHub, but individuals who are at risk for infection may be missing out for other reasons.

The effectiveness of PrEP is clear, those experts said, but 34% of primary care physicians and nurses in the United States are unaware of the preventive regimen, according to the WalletHub report, which also noted that the majority of Americans with AIDS (61%) are not seeing a specialist.

“Even among [men who have sex with men] in the U.S., coverage is only about 10%, which is abysmal. We can and need to do better. If we don’t pay now, we’ll pay later,” Steffanie Strathdee, PhD, associate dean of global health sciences and Harold Simon Professor at the University of California, San Diego, told WalletHub.

Those taking PrEP have a 90% chance of avoiding HIV infection, the report noted.

“Making PrEP available to all is a giant step forward in the fight against HIV. Mandating this critical prevention be covered by all insurance plans makes it part of mainstream medicine and will only increase its use and help prevent HIV acquisition in exposed populations. I can’t think of other low-risk, high-reward prophylaxis for a lifelong disease,” said Sharon Nachman, MD, professor of pediatrics and associate dean for research at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

To get PrEP covered, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force needs to act, explained Gerald M. Oppenheimer, PhD, MPH, of the department of health policy and management at the City University of New York.

“Under the Affordable Care Act, if the [USPSTF] finds that PrEP serves as an effective prevention to disease and gives it a grade of A or B, all insurers must offer it free. That, of course, may lead to an increase in premiums. This is another example of pharmaceutical companies charging high prices in the U.S., compared to what other countries pay, and cries out for an amendment to Medicare Part D, allowing the federal government to negotiate lower drug prices,” he said.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is valuable enough for the federal government to mandate insurance coverage, a group of experts told the personal finance website WalletHub, but individuals who are at risk for infection may be missing out for other reasons.

The effectiveness of PrEP is clear, those experts said, but 34% of primary care physicians and nurses in the United States are unaware of the preventive regimen, according to the WalletHub report, which also noted that the majority of Americans with AIDS (61%) are not seeing a specialist.

“Even among [men who have sex with men] in the U.S., coverage is only about 10%, which is abysmal. We can and need to do better. If we don’t pay now, we’ll pay later,” Steffanie Strathdee, PhD, associate dean of global health sciences and Harold Simon Professor at the University of California, San Diego, told WalletHub.

Those taking PrEP have a 90% chance of avoiding HIV infection, the report noted.

“Making PrEP available to all is a giant step forward in the fight against HIV. Mandating this critical prevention be covered by all insurance plans makes it part of mainstream medicine and will only increase its use and help prevent HIV acquisition in exposed populations. I can’t think of other low-risk, high-reward prophylaxis for a lifelong disease,” said Sharon Nachman, MD, professor of pediatrics and associate dean for research at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.