User login

Temixys plus other antiretrovirals approved for HIV-1

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the combination of lamivudine (3TC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) known as Temixys for treatment of HIV-1 when used with other antiretrovirals. The approval is for adult and pediatric patients with HIV-1 who weigh at least 35 kg.

The approval is based on data through 144 weeks in a double-blind, active-controlled, multicenter trial in 600 antiretroviral-naive patients. The trial compared TDF/3TC plus efavirenz (EFV) with 3TC/EFV plus stavudine (d4T). The results showed similar responses at 144 weeks between both groups: 62% of patients taking TDF/3TC/EFV and 58% of patients taking d4T/3TC/EFV achieved and maintained fewer than 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA.

The most common adverse events include headache, pain, depression, rash, and diarrhea. Prior to initiating treatment, patients should be tested for hepatitis B virus because there have been reports of 3TC-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus associated with treatment of HIV-1 with 3TC-containing regimens in coinfected patients. Patients should also be tested for estimated creatinine clearance, urine glucose, and urine protein because TDF/3TC is not recommended for patients with renal impairment.

The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the combination of lamivudine (3TC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) known as Temixys for treatment of HIV-1 when used with other antiretrovirals. The approval is for adult and pediatric patients with HIV-1 who weigh at least 35 kg.

The approval is based on data through 144 weeks in a double-blind, active-controlled, multicenter trial in 600 antiretroviral-naive patients. The trial compared TDF/3TC plus efavirenz (EFV) with 3TC/EFV plus stavudine (d4T). The results showed similar responses at 144 weeks between both groups: 62% of patients taking TDF/3TC/EFV and 58% of patients taking d4T/3TC/EFV achieved and maintained fewer than 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA.

The most common adverse events include headache, pain, depression, rash, and diarrhea. Prior to initiating treatment, patients should be tested for hepatitis B virus because there have been reports of 3TC-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus associated with treatment of HIV-1 with 3TC-containing regimens in coinfected patients. Patients should also be tested for estimated creatinine clearance, urine glucose, and urine protein because TDF/3TC is not recommended for patients with renal impairment.

The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the combination of lamivudine (3TC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) known as Temixys for treatment of HIV-1 when used with other antiretrovirals. The approval is for adult and pediatric patients with HIV-1 who weigh at least 35 kg.

The approval is based on data through 144 weeks in a double-blind, active-controlled, multicenter trial in 600 antiretroviral-naive patients. The trial compared TDF/3TC plus efavirenz (EFV) with 3TC/EFV plus stavudine (d4T). The results showed similar responses at 144 weeks between both groups: 62% of patients taking TDF/3TC/EFV and 58% of patients taking d4T/3TC/EFV achieved and maintained fewer than 50 copies/mL of HIV-1 RNA.

The most common adverse events include headache, pain, depression, rash, and diarrhea. Prior to initiating treatment, patients should be tested for hepatitis B virus because there have been reports of 3TC-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus associated with treatment of HIV-1 with 3TC-containing regimens in coinfected patients. Patients should also be tested for estimated creatinine clearance, urine glucose, and urine protein because TDF/3TC is not recommended for patients with renal impairment.

The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

The powerful virus inflammatory response

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at [email protected].

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at [email protected].

Inflammation is a double-edged sword. Controlled and modest proinflammatory responses can enhance host immunity against viruses and decrease bacterial colonization and infection, whereas excessive uncontrolled proinflammatory responses may increase the susceptibility to bacterial colonization and secondary infection to facilitate disease pathogenesis. The immune system produces both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. It is a balanced response that is key to maintaining good health.

Viral upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) are caused by rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, enteroviruses, respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza A and B viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and human metapneumoviruses. Viruses are powerful. In the nose, they induce hypersecretion of mucus, slow cilia beating, up-regulate nasal epithelial cell receptors to facilitate bacterial attachment, suppress neutrophil function, and cause increased release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. All these actions by respiratory viruses promote bacterial overgrowth in the nasopharynx and thereby facilitate bacterial superinfections. In fact, progression in pathogenesis of the common bacterial respiratory infections – acute otitis media, acute sinusitis, acute conjunctivitis, and pneumonia – almost always is preceded by a viral URI. Viruses activate multiple target cells in the upper respiratory tract to produce an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The symptoms of a viral URI resolve coinciding with an anti-inflammatory response and adaptive immunity.

In recent work, we found a higher frequency of viral URIs in children who experienced more frequent acute otitis media (AOM). We sought to understand why this might occur by comparing levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the nose during viral URI that did not precipitate AOM versus when a viral URI precipitated an AOM episode. When a child had a viral URI but did not go on to experience an AOM, the child had higher proinflammatory responses than when the viral URI precipitated an AOM. When differences of levels of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines were compared in otitis-prone and non–otitis-prone children, lower nasal responses were associated with higher otitis-prone classification frequency (Clin Infect Dis. 2018. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy750).

The powerful virus and the inflammatory response it can induce also play a major role in allergy and asthma. Viral URIs enhance allergic sensitization to respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, cause cytopathic damage to airway epithelium, promote excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production, and increase the exposure of allergens and irritants to antigen-presenting cells. Viral infections also may induce the release of epithelial mediators and cytokines that may propagate eosinophilia. Viral URIs, particularly with respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus, are the most common causes of wheezing in children, and they have important influences on the development of asthma. Studies have shown that viral infections trigger up to 85% of asthma exacerbations in school-aged children.

Because this column is being published during the winter, a brief discussion of influenza as a powerful virus is appropriate. Influenza occurs in winter outbreaks of varying extent every year. The severity of the influenza season reflects the changing nature of the antigenic properties of influenza viruses, and their spread depends on susceptibility of the population. Influenza outbreaks typically peak over a 2-3 week period and last for 2-3 months. Most outbreaks have attack rates of 10%-20% in children. There may be variations in disease severity caused by different influenza virus types. The symptoms are caused by excessive proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine production in the nose and lung.

Influenza and other viruses can precipitate the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), a manifestation of extreme immune dysregulation resulting in organ dysfunction that clinically resembles bacterial sepsis. In this syndrome, tissues remote from the original insult display the cardinal signs of inflammation, including vasodilation, increased microvascular permeability, and leukocyte accumulation. SIRS is another example of the double-edged sword of inflammation.

The onset and progression of SIRS occurs because of dysregulation of the normal inflammatory response, usually with an increase in both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, initiating a chain of events that leads to organ failure.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He reported having no conflicts of interest. Email him at [email protected].

CDC: No medical therapy can yet be recommended for acute flaccid myelitis

The updated guidance on managing acute flaccid myelitis is unlikely to relieve the frustrations of physicians struggling to treat the condition.

After reviewing the extant data on the baffling disorder, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found no evidence that corticosteroids, interferon, antivirals, or any other immunologic or biologic therapy is an effective treatment.

All of the treatments mentioned in the guidance have been used anecdotally, and often for cases proven to be associated with enterovirus-related cases. However, there are no well validated studies confirming benefit for any of these approaches, the agency said in its clinical management document.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) has stricken 90 patients in the United States this year and another 252 cases are being investigated, according to new data from the CDC. The number of confirmed cases is triple that seen in 2017. Whether the disease is an infectious or autoimmune process, or something else entirely, remains unknown.

In response to the outbreak – the largest since 2014 – an expert panel of 4 CDC staff physicians reviewed the literature to find what, if any, treatments were effective; another 14 external experts provided input on the recommendations. At this point, nothing can be officially recommended, the agency said.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should not be administered to most patients with AFM. In addition to “a theoretical concern” about the potential adverse effects of these drugs in acute infections, there is some hard evidence that they are associated with worse outcomes in enteroviral neuroinvasive diseases, particularly those caused by EV-71.

This observation, following a 2012 outbreak in Cambodia, led a World Health Organization commission to conclude that corticosteroids were contraindicated in the management of EV-71–associated neuroinvasive disease. This year, there has been an uptick in EV-A71-associated neurologic disease.

The CDC did hedge its advice on corticosteroids a bit in the setting of AFM, however. “There may be theoretical benefit for steroids in the setting of severe cord swelling or long tract signs suggesting white matter involvement, where steroids may salvage tissue that may be harmed due to an ongoing immune/inflammatory response. While AFM is clinically and radiographically defined by the predominance of gray matter damage in the spinal cord, some patients may have some white matter involvement. It is not clear if these different patterns are important relative to therapeutic considerations.”

Nevertheless, the agency does not recommend corticosteroid use for these patients. “The possible benefits of the use of corticosteroids to manage spinal cord edema or white matter involvement in AFM should be balanced with the possible harm due to immunosuppression in the setting of possible viral infection.”

IVIG

While IVIG holds some theoretical benefit for AFM, there are no high-level human data, the guidelines state. The treatment is generally safe and well tolerated, but the few reports of its use in AFM did not show clear benefit. These include two case series. One suggested an acute improvement of neurologic status, but no long-term resolution of deficits. The other indicated neither significant improvement nor deterioration.

However, current practice at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is to initiate IVIG therapy at AFM diagnosis in hopes of boosting humoral immunity.

Nevertheless, the CDC said, “For IVIG to modify disease in an active viral infectious process, early administration is likely required, and possibly prior to exposure,” and the treatment cannot be recommended.

Plasma exchange

Plasma exchange in combination with IVIG and corticosteroids was ineffective in a case series of four Argentinian children, although a single case published last year found that the combination was associated with significant improvement. However, there are not enough data to recommend this approach.

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine’s antiviral potential turned up in a high-throughput screening project to identify novel compounds with antiviral efficacy against enteroviruses. In 2012, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, tested more than 1,000 compounds and found that the SSRI is a potent inhibitor of coxsackievirus. A later project at the National Institutes of Health replicated this finding, and determined that fluoxetine inhibited several enteroviruses, including the AFM suspect, EV-D68.

Fluoxetine concentrates more highly in the central nervous system than it does in plasma, but its antiviral properties have nothing to do with neurotransmitter activity. Rather, it appears to inhibit protein 2C, a highly conserved nonstructural protein that’s crucial to the assembly of RNA into virion particles.

In early November, a retrospective study examined fluoxetine’s use in 30 AFM patients, compared with 26 who did not receive it. The primary outcome was change in summative limb strength score. The study did little to clarify any benefit, however. The authors concluded that fluoxetine was preferentially given to patients with EDV-68 infections. They had more severe impairment at nadir, and at the last follow-up of about 1 year, they had worse outcomes.

“There is no clear human evidence for efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of AFM based on a single retrospective evaluation conducted in patients with AFM, and data from a mouse model also did not support efficacy,” the CDC said.

Antiviral medications

The CDC is quite clear on its recommendation that these drugs are not indicated in AFM, since it is not yet proven to be an infectious process.

“Any guidance regarding antiviral medications should be interpreted with great caution, given the unknowns about the pathogenesis of this illness at present ... Testing has been conducted at CDC for antiviral activity of compounds pleconaril, pocapavir, and vapendavir and none have significant activity against currently circulating strains of EV-D68 at clinically relevant concentrations.”

Interferon

There is some anecdotal evidence that interferon alpha-2b was beneficial in treating a polio-like syndrome associated with West Nile virus and Saint Louis encephalitis. “Although there are limited in vitro, animal, and anecdotal human data suggesting activity of some interferons against viral infections, sufficient data are lacking in the setting of AFM,” the agency said. “There is no indication that interferon should be used for the treatment of AFM, and there is concern about the potential for harm from the use of interferon given the immunomodulatory effects in the setting of possible ongoing viral replication.”

SOURCE: CDC Acute Flaccid Myelitis: Interim Considerations for Clinical Management

The updated guidance on managing acute flaccid myelitis is unlikely to relieve the frustrations of physicians struggling to treat the condition.

After reviewing the extant data on the baffling disorder, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found no evidence that corticosteroids, interferon, antivirals, or any other immunologic or biologic therapy is an effective treatment.

All of the treatments mentioned in the guidance have been used anecdotally, and often for cases proven to be associated with enterovirus-related cases. However, there are no well validated studies confirming benefit for any of these approaches, the agency said in its clinical management document.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) has stricken 90 patients in the United States this year and another 252 cases are being investigated, according to new data from the CDC. The number of confirmed cases is triple that seen in 2017. Whether the disease is an infectious or autoimmune process, or something else entirely, remains unknown.

In response to the outbreak – the largest since 2014 – an expert panel of 4 CDC staff physicians reviewed the literature to find what, if any, treatments were effective; another 14 external experts provided input on the recommendations. At this point, nothing can be officially recommended, the agency said.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should not be administered to most patients with AFM. In addition to “a theoretical concern” about the potential adverse effects of these drugs in acute infections, there is some hard evidence that they are associated with worse outcomes in enteroviral neuroinvasive diseases, particularly those caused by EV-71.

This observation, following a 2012 outbreak in Cambodia, led a World Health Organization commission to conclude that corticosteroids were contraindicated in the management of EV-71–associated neuroinvasive disease. This year, there has been an uptick in EV-A71-associated neurologic disease.

The CDC did hedge its advice on corticosteroids a bit in the setting of AFM, however. “There may be theoretical benefit for steroids in the setting of severe cord swelling or long tract signs suggesting white matter involvement, where steroids may salvage tissue that may be harmed due to an ongoing immune/inflammatory response. While AFM is clinically and radiographically defined by the predominance of gray matter damage in the spinal cord, some patients may have some white matter involvement. It is not clear if these different patterns are important relative to therapeutic considerations.”

Nevertheless, the agency does not recommend corticosteroid use for these patients. “The possible benefits of the use of corticosteroids to manage spinal cord edema or white matter involvement in AFM should be balanced with the possible harm due to immunosuppression in the setting of possible viral infection.”

IVIG

While IVIG holds some theoretical benefit for AFM, there are no high-level human data, the guidelines state. The treatment is generally safe and well tolerated, but the few reports of its use in AFM did not show clear benefit. These include two case series. One suggested an acute improvement of neurologic status, but no long-term resolution of deficits. The other indicated neither significant improvement nor deterioration.

However, current practice at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is to initiate IVIG therapy at AFM diagnosis in hopes of boosting humoral immunity.

Nevertheless, the CDC said, “For IVIG to modify disease in an active viral infectious process, early administration is likely required, and possibly prior to exposure,” and the treatment cannot be recommended.

Plasma exchange

Plasma exchange in combination with IVIG and corticosteroids was ineffective in a case series of four Argentinian children, although a single case published last year found that the combination was associated with significant improvement. However, there are not enough data to recommend this approach.

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine’s antiviral potential turned up in a high-throughput screening project to identify novel compounds with antiviral efficacy against enteroviruses. In 2012, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, tested more than 1,000 compounds and found that the SSRI is a potent inhibitor of coxsackievirus. A later project at the National Institutes of Health replicated this finding, and determined that fluoxetine inhibited several enteroviruses, including the AFM suspect, EV-D68.

Fluoxetine concentrates more highly in the central nervous system than it does in plasma, but its antiviral properties have nothing to do with neurotransmitter activity. Rather, it appears to inhibit protein 2C, a highly conserved nonstructural protein that’s crucial to the assembly of RNA into virion particles.

In early November, a retrospective study examined fluoxetine’s use in 30 AFM patients, compared with 26 who did not receive it. The primary outcome was change in summative limb strength score. The study did little to clarify any benefit, however. The authors concluded that fluoxetine was preferentially given to patients with EDV-68 infections. They had more severe impairment at nadir, and at the last follow-up of about 1 year, they had worse outcomes.

“There is no clear human evidence for efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of AFM based on a single retrospective evaluation conducted in patients with AFM, and data from a mouse model also did not support efficacy,” the CDC said.

Antiviral medications

The CDC is quite clear on its recommendation that these drugs are not indicated in AFM, since it is not yet proven to be an infectious process.

“Any guidance regarding antiviral medications should be interpreted with great caution, given the unknowns about the pathogenesis of this illness at present ... Testing has been conducted at CDC for antiviral activity of compounds pleconaril, pocapavir, and vapendavir and none have significant activity against currently circulating strains of EV-D68 at clinically relevant concentrations.”

Interferon

There is some anecdotal evidence that interferon alpha-2b was beneficial in treating a polio-like syndrome associated with West Nile virus and Saint Louis encephalitis. “Although there are limited in vitro, animal, and anecdotal human data suggesting activity of some interferons against viral infections, sufficient data are lacking in the setting of AFM,” the agency said. “There is no indication that interferon should be used for the treatment of AFM, and there is concern about the potential for harm from the use of interferon given the immunomodulatory effects in the setting of possible ongoing viral replication.”

SOURCE: CDC Acute Flaccid Myelitis: Interim Considerations for Clinical Management

The updated guidance on managing acute flaccid myelitis is unlikely to relieve the frustrations of physicians struggling to treat the condition.

After reviewing the extant data on the baffling disorder, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found no evidence that corticosteroids, interferon, antivirals, or any other immunologic or biologic therapy is an effective treatment.

All of the treatments mentioned in the guidance have been used anecdotally, and often for cases proven to be associated with enterovirus-related cases. However, there are no well validated studies confirming benefit for any of these approaches, the agency said in its clinical management document.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) has stricken 90 patients in the United States this year and another 252 cases are being investigated, according to new data from the CDC. The number of confirmed cases is triple that seen in 2017. Whether the disease is an infectious or autoimmune process, or something else entirely, remains unknown.

In response to the outbreak – the largest since 2014 – an expert panel of 4 CDC staff physicians reviewed the literature to find what, if any, treatments were effective; another 14 external experts provided input on the recommendations. At this point, nothing can be officially recommended, the agency said.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should not be administered to most patients with AFM. In addition to “a theoretical concern” about the potential adverse effects of these drugs in acute infections, there is some hard evidence that they are associated with worse outcomes in enteroviral neuroinvasive diseases, particularly those caused by EV-71.

This observation, following a 2012 outbreak in Cambodia, led a World Health Organization commission to conclude that corticosteroids were contraindicated in the management of EV-71–associated neuroinvasive disease. This year, there has been an uptick in EV-A71-associated neurologic disease.

The CDC did hedge its advice on corticosteroids a bit in the setting of AFM, however. “There may be theoretical benefit for steroids in the setting of severe cord swelling or long tract signs suggesting white matter involvement, where steroids may salvage tissue that may be harmed due to an ongoing immune/inflammatory response. While AFM is clinically and radiographically defined by the predominance of gray matter damage in the spinal cord, some patients may have some white matter involvement. It is not clear if these different patterns are important relative to therapeutic considerations.”

Nevertheless, the agency does not recommend corticosteroid use for these patients. “The possible benefits of the use of corticosteroids to manage spinal cord edema or white matter involvement in AFM should be balanced with the possible harm due to immunosuppression in the setting of possible viral infection.”

IVIG

While IVIG holds some theoretical benefit for AFM, there are no high-level human data, the guidelines state. The treatment is generally safe and well tolerated, but the few reports of its use in AFM did not show clear benefit. These include two case series. One suggested an acute improvement of neurologic status, but no long-term resolution of deficits. The other indicated neither significant improvement nor deterioration.

However, current practice at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is to initiate IVIG therapy at AFM diagnosis in hopes of boosting humoral immunity.

Nevertheless, the CDC said, “For IVIG to modify disease in an active viral infectious process, early administration is likely required, and possibly prior to exposure,” and the treatment cannot be recommended.

Plasma exchange

Plasma exchange in combination with IVIG and corticosteroids was ineffective in a case series of four Argentinian children, although a single case published last year found that the combination was associated with significant improvement. However, there are not enough data to recommend this approach.

Fluoxetine

Fluoxetine’s antiviral potential turned up in a high-throughput screening project to identify novel compounds with antiviral efficacy against enteroviruses. In 2012, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, tested more than 1,000 compounds and found that the SSRI is a potent inhibitor of coxsackievirus. A later project at the National Institutes of Health replicated this finding, and determined that fluoxetine inhibited several enteroviruses, including the AFM suspect, EV-D68.

Fluoxetine concentrates more highly in the central nervous system than it does in plasma, but its antiviral properties have nothing to do with neurotransmitter activity. Rather, it appears to inhibit protein 2C, a highly conserved nonstructural protein that’s crucial to the assembly of RNA into virion particles.

In early November, a retrospective study examined fluoxetine’s use in 30 AFM patients, compared with 26 who did not receive it. The primary outcome was change in summative limb strength score. The study did little to clarify any benefit, however. The authors concluded that fluoxetine was preferentially given to patients with EDV-68 infections. They had more severe impairment at nadir, and at the last follow-up of about 1 year, they had worse outcomes.

“There is no clear human evidence for efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of AFM based on a single retrospective evaluation conducted in patients with AFM, and data from a mouse model also did not support efficacy,” the CDC said.

Antiviral medications

The CDC is quite clear on its recommendation that these drugs are not indicated in AFM, since it is not yet proven to be an infectious process.

“Any guidance regarding antiviral medications should be interpreted with great caution, given the unknowns about the pathogenesis of this illness at present ... Testing has been conducted at CDC for antiviral activity of compounds pleconaril, pocapavir, and vapendavir and none have significant activity against currently circulating strains of EV-D68 at clinically relevant concentrations.”

Interferon

There is some anecdotal evidence that interferon alpha-2b was beneficial in treating a polio-like syndrome associated with West Nile virus and Saint Louis encephalitis. “Although there are limited in vitro, animal, and anecdotal human data suggesting activity of some interferons against viral infections, sufficient data are lacking in the setting of AFM,” the agency said. “There is no indication that interferon should be used for the treatment of AFM, and there is concern about the potential for harm from the use of interferon given the immunomodulatory effects in the setting of possible ongoing viral replication.”

SOURCE: CDC Acute Flaccid Myelitis: Interim Considerations for Clinical Management

Immunotherapy may hold the key to defeating virally associated cancers

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

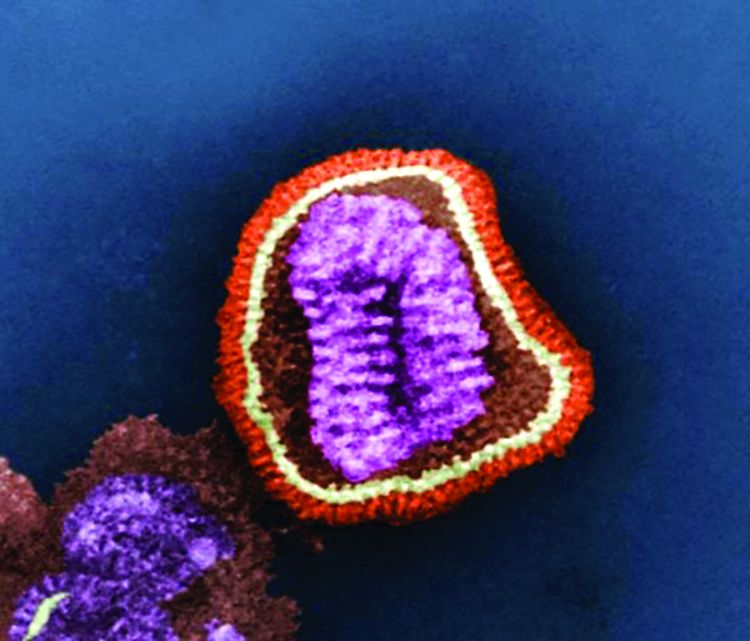

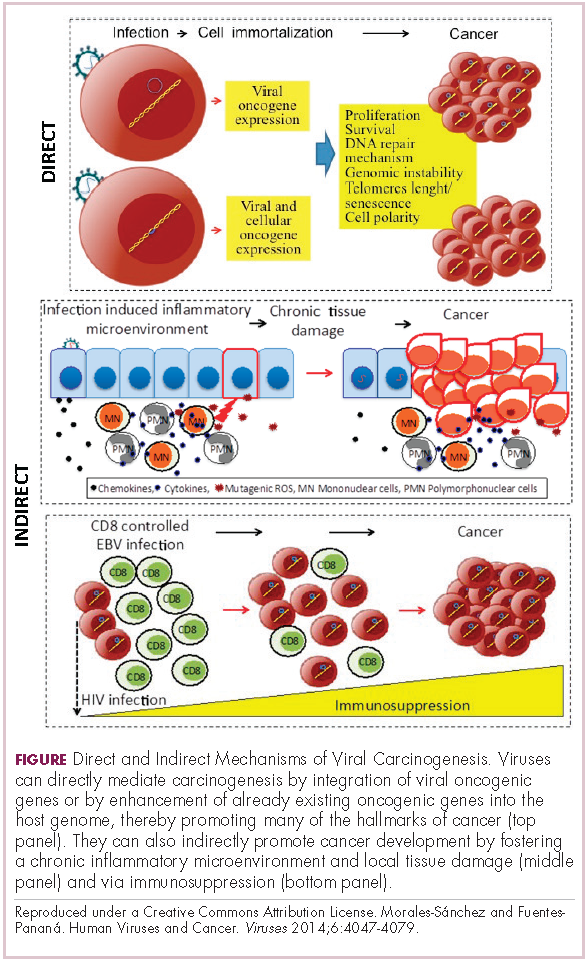

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

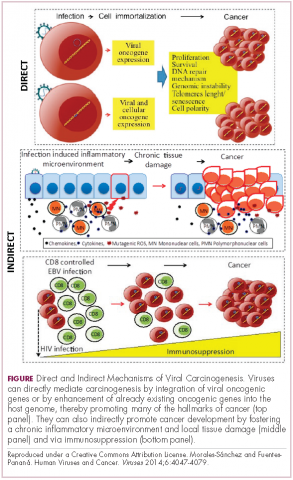

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

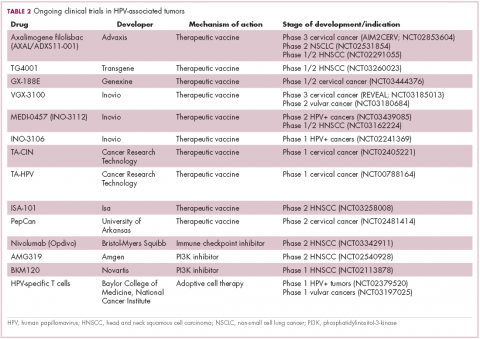

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

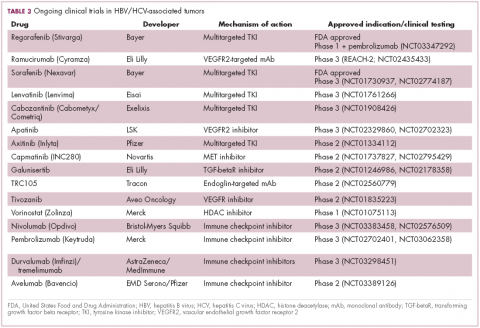

Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

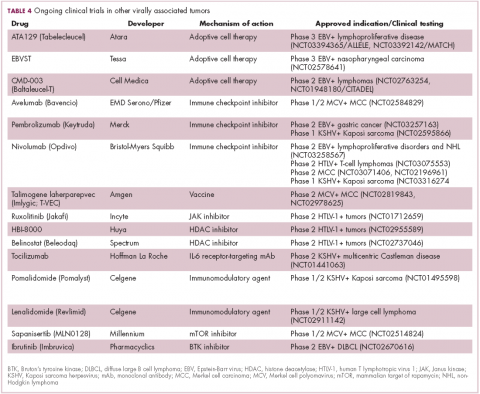

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31

Newest oncovirus on the block

The most recently discovered cancer-associated virus is Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), a DNA virus that was identified in 2008. Like EBV, virtually the whole global adult population is infected with MCV. It is linked to the development of a highly aggressive and lethal, though rare, form of skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma.

MCV is found in around 80% of MCC cases and in fewer than 10% of melanomas and other skin cancers. Thus far, several direct mechanisms of oncogenesis have been described, including integration of MCV into the host genome and the production of viral oncogenes, though their precise function is as yet unclear.32-34

The American Cancer Society estimates that only 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year in the United States.35 Its rarity makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials with sufficient power, yet some headway has still been made.

Around half of MCCs express the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, making them a logical candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. In 2017, avelumab became the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of MCC. Approval was based on the JAVELIN Merkel 200 study in which 88 patients received avelumab. After 1 year of follow-up the ORR was 31.8%, with a CR rate of 9%.36

Genome sequencing studies suggest that the mutational profile of MCV-positive tumors is quite different to those that are MCV-negative, which could have therapeutic implications. To date, these implications have not been delineated, given the challenge of small patient numbers, however an ongoing phase 1/2 trial is evaluating the combination of avelumab and radiation therapy or recombinant interferon beta, with or without MCV-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with MCC and MCV infection.

The 2 other known cancer-causing viruses are human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). The latter is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a rare skin tumor that became renowned in the 1980s as an AIDS-defining illness.

The incidence of HTLV-1- and KSHV-positive tumors is substantially lower than the other virally associated cancers and, like MCC, this makes studying them and conducting clinical trials of novel therapeutic options a challenge. Nonetheless, several trials of targeted therapies and immunotherapies are underway.

1. Rous PA. Transmissible avain neoplasm. (Sarcoma of the common fowl). J Exp Med. 1910;12(5):696-705.

2. Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet. 1964;1(7335):702-703.

3. Mesri Enrique A, Feitelson MA, Munger K. Human viral oncogenesis: a cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014;15(3):266-282.

4. Santana-Davila R, Bhatia S, Chow LQ. Harnessing the immune system as a therapeutic tool in virus-associated cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):106-112.

5. Tashiro H, Brenner MK. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017;27(1):59-73.

6. Brianti P, De Flammineis E, Mercuri SR. Review of HPV-related diseases and cancers. New Microbiol. 2017;40(2):80-85.

7. Tulay P, Serakinci N. The route to HPV-associated neoplastic transformation: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26(1):27-39.

8. Smola S. Immunopathogenesis of HPV-associated cancers and prospects for immunotherapy. Viruses. 2017;9(9).

9. Rosales R, Rosales C. Immune therapy for human papillomaviruses-related cancers. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(5):1002-1019.

10. Miles B, Safran HP, Monk BJ. Therapeutic options for treatment of human papillomavirus-associated cancers - novel immunologic vaccines: ADXS11-001. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:10.

11. Miles BA, Monk BJ, Safran HP. Mechanistic insights into ADXS11-001 human papillomavirus-associated cancer immunotherapy. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:9.

12. Huh W, Dizon D, Powell M, Landrum L, Leath C. A prospective phase II trial of the listeria-based human papillomavirus immunotherapy axalimogene filolisbac in second and third-line metastatic cervical cancer: A NRG oncology group trial. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting on Women's Cancer; March 12-15, 2017, 2017; National Harbor, MD.

13. Petit RG, Mehta A, Jain M, et al. ADXS11-001 immunotherapy targeting HPV-E7: final results from a Phase II study in Indian women with recurrent cervical cancer. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer. 2014;2(Suppl 3):P92-P92.

14. Glisson B, Massarelli E, William W, et al. Nivolumab and ISA 101 HPV vaccine in incurable HPV-16+ cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):v403-v427.

15. Ding X-X, Zhu Q-G, Zhang S-M, et al. Precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma: driver mutations and targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(33):55715-55730.

16. Ringehan M, McKeating JA, Protzer U. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;372(1732):20160274.

17. Abou-Alfa G, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;36(Suppl 4S):abstr 207.

18. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018.

19. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Cattan S, et al. KEYNOTE-224: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(Suppl 4S):Abstr 209.

20. Kelley RK, Abou-Alfa GK, Bendell JC, et al. Phase I/II study of durvalumab and tremelimumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Phase I safety and efficacy analyses. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(15_suppl):4073-4073.

21. Jackson R, Psarelli E-E, Berhane S, Khan H, Johnson P. Impact of Viral Status on Survival in Patients Receiving Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Phase III Trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(6):622-628.

22. Kudo M. Molecular Targeted Agents for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(2):101-112.

23. zur Hausen H, Meinhof W, Scheiber W, Bornkamm GW. Attempts to detect virus-secific DNA in human tumors. I. Nucleic acid hybridizations with complementary RNA of human wart virus. Int J Cancer. 1974;13(5):650-656.

24. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56-66.

25. Bruix J, Tak WY, Gasbarrini A, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(16):3412-3419.

26. Neparidze N, Lacy J. Malignancies associated with epstein-barr virus: pathobiology, clinical features, and evolving treatments. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12(6):358-371.

27. Ozoya OO, Sokol L, Dalia S. EBV-Related Malignancies, Outcomes and Novel Prevention Strategies. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2016;16(1):4-21.

28. Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, et al. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):81-88.

29. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202.

30. Prockop S, Li A, Baiocchi R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ATA129, partially matched allogeneic third-party Epstein-Barr virus-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a multicenter study for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

31. Kim W, Ardeshna K, Lin Y, et al. Autologous EBV-specific T cells (CMD-003): Early results from a multicenter, multinational Phase 2 trial for treatment of EBV-associated NK/T-cell lymphoma. Paper presented at: 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; December 9-12, 2017, 2017; Atlanta, GA.

32. Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, zur Hausen A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. European Journal of Cancer. 2017;71:53-69.

33. Spurgeon ME, Lambert PF. Merkel cell polyomavirus: a newly discovered human virus with oncogenic potential. Virology. 2013;435(1):118-130.

34. Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, Yu SS. Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):445-454.

35. American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 2015; https://www.cancer.org/cancer/merkel-cell-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#written_by. Accessed March 7th, 2017.

36. Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology.17(10):1374-1385.

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7

The largest investment in therapeutic development for HPV-positive cancers has been in the realm of immunotherapy in an effort to boost the anti-tumor immune response. In particular, there has been a focus on the development of therapeutic vaccines, designed to prime the anti-tumor immune response to recognize viral antigens. A variety of different types of vaccines are being developed, including live, attenuated and inactivated vaccines that are protein, DNA, or peptide based. Most developed to date target the E6/E7 proteins from the HPV16/18 strains (Table 2).8,9

Other immunotherapies are also being evaluated, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, antibodies designed to target one of the principal mechanisms of immune evasion exploited by cancer cells. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with vaccines is a particularly promising strategy in HPV-associated cancers. At the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in 2017, the results of a phase 2 trial of nivolumab in combination with ISA-101 were presented.

Among 24 patients with HPV-positive tumors, the majority oropharyngeal cancers, the combination elicited an overall response rate (ORR) of 33%, including 2 complete responses (CRs). Most adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate in severity and included fever, injection site reactions, fatigue and nausea.14

Hepatocellular carcinoma: a tale of two viruses

The hepatitis viruses are a group of 5 unrelated viruses that causes inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B (HBV), a DNA virus, and hepatitis C (HCV), an RNA virus, are also oncoviruses; HBV in particular is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer.

The highly inflammatory environment fostered by HBV and HCV infection causes liver damage that often leads to cirrhosis. Continued infection can drive permanent damage to the hepatocytes, leading to genetic and epigenetic damage and driving oncogenesis. As an RNA virus, HCV doesn’t integrate into the genome and no confirmed viral oncoproteins have been identified to date, therefore it mostly drives cancer through these indirect mechanisms, which is also reflected in the fact that HCV-associated HCC predominantly occurs against a backdrop of liver cirrhosis.

HBV does integrate into the host genome. Genome sequencing studies revealed hundreds of integration sites, but most commonly they disrupted host genes involved in telomere stability and cell cycle regulation, providing some insight into the mechanisms by which HBV-associated HCC develops. In addition, HBV produces several oncoproteins, including HBx, which disrupts gene transcription, cell signaling pathways, cell cycle progress, apoptosis and other cellular processes.15,16

Multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been the focal point of therapeutic development in HCC. However, following the approval of sorafenib in 2008, there was a dearth of effective new treatment options despite substantial efforts and numerous phase 3 trials. More recently, immunotherapy has also come to the forefront, especially immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Last year marked the first new drug approvals in nearly a decade – the TKI regorafenib (Stivarga) and immune checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo), both in the second-line setting after failure of sorafenib. Treatment options in this setting may continue to expand, with the TKIs cabozantinib and lenvatinib and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab and the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab hot on their heels.17-20 Many of these drugs are also being evaluated in the front-line setting in comparison with sorafenib (Table 3).

At the current time, the treatment strategy for patients with HCC is independent of etiology, however, there are significant ongoing efforts to try to tease out the implications of infection for treatment efficacy. A recent meta-analysis of patients treated with sorafenib in 3 randomized phase 3 trials (n = 3,526) suggested that it improved overall survival (OS) among patients who were HCV-positive, but HBV-negative.21

Studies of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-targeting monoclonal antibody ramucirumab, on the other hand, suggested that it may have a greater OS benefit in patients with HBV, while regorafenib seemed to have a comparable OS benefit in both subgroups.22-25 The immune checkpoint inhibitors studied thus far seem to elicit responses irrespective of infection status.

A phase 2 trial of the immune checkpoint inhibitor tremelimumab was conducted specifically in patients with advanced HCC and chronic HCV infection. The disease control rate (DCR) was 76.4%, with 17.6% partial response (PR) rate. There was also a significant drop in viral load, suggesting that tremelimumab may have antiviral effects.26,27,28

Adoptive cell therapy promising in EBV-positive cancers

More than 90% of the global population is infected with EBV, making it one of the most common human viruses. It is a member of the herpesvirus family that is probably best known as the cause of infectious mononucleosis. On rare occasions, however, EBV can cause tumor development, though our understanding of its exact pathogenic role in cancer is still incomplete.

EBV is a DNA virus that doesn’t tend to integrate into the host genome, but instead remains in the nucleus in the form of episomes and produces several oncoproteins, including latent membrane protein-1. It is associated with a range of different cancer types, including Burkitt lymphoma and other B-cell malignancies. It also infects epithelial cells and can cause nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric cancer, however, much less is known about the molecular underpinnings of these EBV-positive cancer types.26,27Gastric cancers actually comprise the largest group of EBV-associated tumors because of the global incidence of this cancer type. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network recently characterized gastric cancer on a molecular level and identified an EBV-positive subgroup as a distinct clinical entity with unique molecular characteristics.29

The focus of therapeutic development has again been on immunotherapy, however in this case the idea of collecting the patients T cells, engineering them to recognize EBV, and then reinfusing them into the patient – adoptive cell therapy – has gained the most traction (Table 4).

Two presentations at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in 2017 detailed ongoing clinical trials of Atara Biotherapeutics’ ATA129 and Cell Medica’s CMD-003. ATA129 was associated with a high response rate and a low rate of serious AEs in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder; ORR was 80% in 6 patients treated after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and 83% in 6 patients after solid organ transplant.30

CMD-003, meanwhile, demonstrated preliminary signs of activity and safety in patients with relapsed extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, according to early results from the phase 2 CITADEL trial. Among 6 evaluable patients, the ORR was 50% and the DCR was 67%.31

Newest oncovirus on the block

The most recently discovered cancer-associated virus is Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), a DNA virus that was identified in 2008. Like EBV, virtually the whole global adult population is infected with MCV. It is linked to the development of a highly aggressive and lethal, though rare, form of skin cancer – Merkel cell carcinoma.

MCV is found in around 80% of MCC cases and in fewer than 10% of melanomas and other skin cancers. Thus far, several direct mechanisms of oncogenesis have been described, including integration of MCV into the host genome and the production of viral oncogenes, though their precise function is as yet unclear.32-34

The American Cancer Society estimates that only 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year in the United States.35 Its rarity makes it difficult to conduct clinical trials with sufficient power, yet some headway has still been made.

Around half of MCCs express the programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface, making them a logical candidate for immune checkpoint inhibition. In 2017, avelumab became the first FDA-approved drug for the treatment of MCC. Approval was based on the JAVELIN Merkel 200 study in which 88 patients received avelumab. After 1 year of follow-up the ORR was 31.8%, with a CR rate of 9%.36

Genome sequencing studies suggest that the mutational profile of MCV-positive tumors is quite different to those that are MCV-negative, which could have therapeutic implications. To date, these implications have not been delineated, given the challenge of small patient numbers, however an ongoing phase 1/2 trial is evaluating the combination of avelumab and radiation therapy or recombinant interferon beta, with or without MCV-specific cytotoxic T cells in patients with MCC and MCV infection.

The 2 other known cancer-causing viruses are human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1), a retrovirus associated with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) and Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). The latter is the causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a rare skin tumor that became renowned in the 1980s as an AIDS-defining illness.

The incidence of HTLV-1- and KSHV-positive tumors is substantially lower than the other virally associated cancers and, like MCC, this makes studying them and conducting clinical trials of novel therapeutic options a challenge. Nonetheless, several trials of targeted therapies and immunotherapies are underway.

Infection with certain viruses has been causally linked to the development of cancer. In recent years, an improved understanding of the unique pathology and molecular underpinnings of these virally associated cancers has prompted the development of more personalized treatment strategies, with a particular focus on immunotherapy. Here, we describe some of the latest developments.

The link between viruses and cancer

Suspicions about a possible role of viral infections in the development of cancer were first aroused in the early 1900s. The seminal discovery is traced back to Peyton Rous, who showed that a malignant tumor growing in a chicken could be transferred to a healthy bird by injecting it with tumor extracts that contained no actual tumor cells.1

The infectious etiology of human cancer, however, remained controversial until many years later when the first cancer-causing virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), was identified in cell cultures from patients with Burkitt lymphoma. Shortly afterward, the Rous sarcoma virus was unveiled as the oncogenic agent behind Rous’ observations.2Seven viruses have now been linked to the development of cancers and are thought to be responsible for around 12% of all cancer cases worldwide. The burden is likely to increase as technological advancements make it easier to establish a causal link between viruses and cancer development.3

In addition to making these links, researchers have also made significant headway in understanding how viruses cause cancer. Cancerous transformation of host cells occurs in only a minority of those who are infected with oncogenic viruses and often occurs in the setting of chronic infection.

Viruses can mediate carcinogenesis by direct and/or indirect mechanisms (Figure 1). Many of the hallmarks of cancer, the key attributes that drive the transformation from a normal cell to a malignant one, are compatible with the virus’s needs, such as needing to avoid cell death, increasing cell proliferation, and avoiding detection by the immune system.

Viruses hijack the cellular machinery to meet those needs and they can do this either by producing viral proteins that have an oncogenic effect or by integrating their genetic material into the host cell genome. When the latter occurs, the process of integration can also cause damage to the DNA, which further increases the risk of cancer-promoting changes occurring in the host genome.

Viruses can indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis by fostering a microenvironment of chronic inflammation, causing oxidative stress and local tissue damage, and by suppressing the antitumor immune response.4,5

Screening and prevention efforts have helped to reduce the burden of several different virally associated cancers. However, for the substantial proportion of patients who are still affected by these cancers, there is a pressing need for new therapeutic options, particularly since genome sequencing studies have revealed that these cancers can often have distinct underlying molecular mechanisms.

Vaccines lead the charge in HPV-driven cancers

German virologist Harald zur Hausen received the Nobel Prize in 2008 for his discovery of the oncogenic role of human papillomaviruses (HPVs), a large family of more than 100 DNA viruses that infect the epithelial cells of the skin and mucous membranes. They are responsible for the largest number of virally associated cancer cases globally – around 5% (Table 1).

A number of different cancer types are linked to HPV infection, but it is best known as the cause of cervical cancer. The development of diagnostic blood tests and prophylactic vaccines for prevention and early intervention in HPV infection has helped to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer. Conversely, another type of HPV-associated cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), has seen increased incidence in recent years.

HPVs are categorized according to their oncogenic potential as high, intermediate, or low risk. The high-risk HPV16 and HPV18 strains are most commonly associated with cancer. They are thought to cause cancer predominantly through integration into the host genome. The HPV genome is composed of 8 genes encoding proteins that regulate viral replication and assembly. The E6 and E7 genes are the most highly oncogenic; as the HPV DNA is inserted into the host genome, the transcriptional regulator of E6/E7 is lost, leading to their increased expression. These genes have significant oncogenic potential because of their interaction with 2 tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and pRb.6,7