User login

Hepatitis vaccination update

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

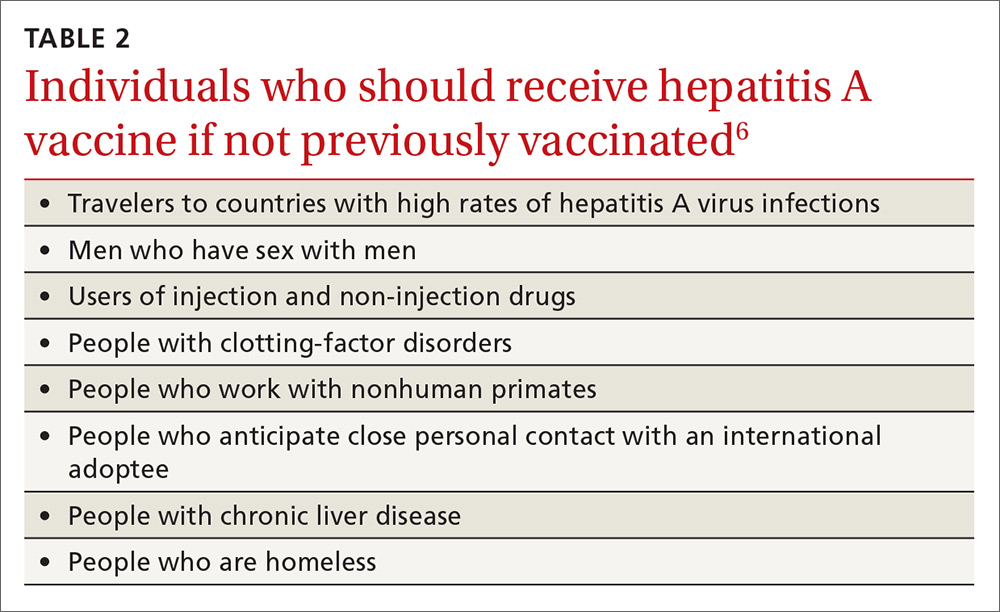

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

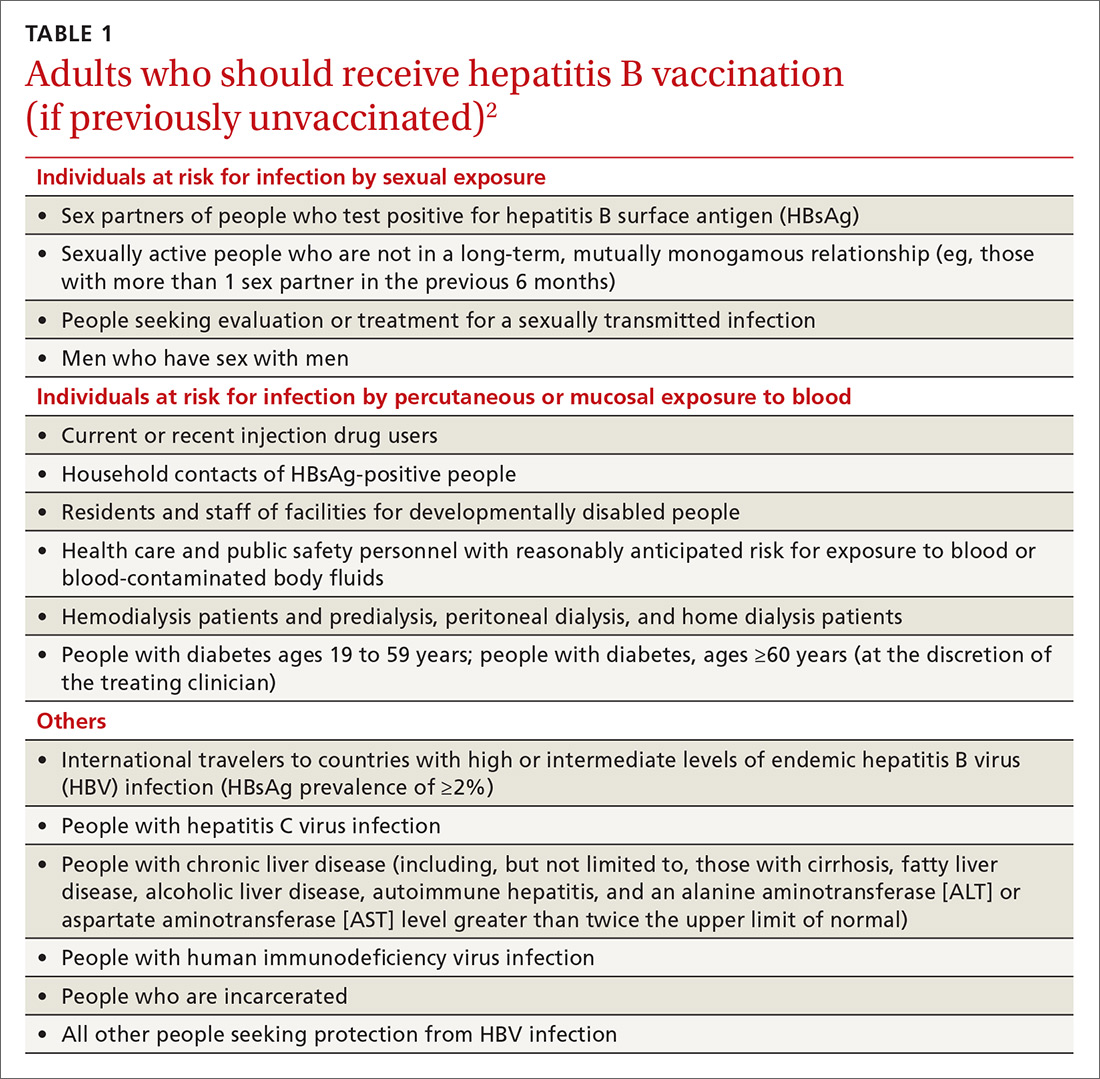

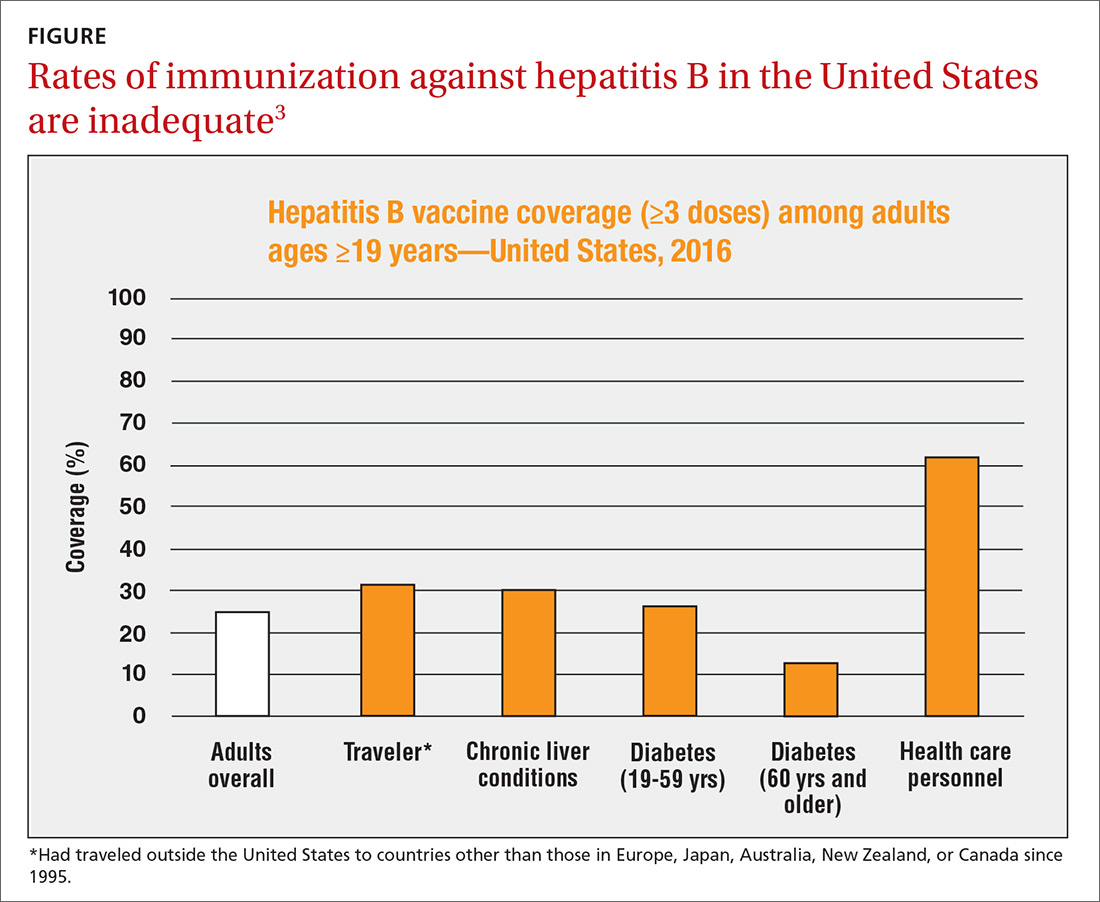

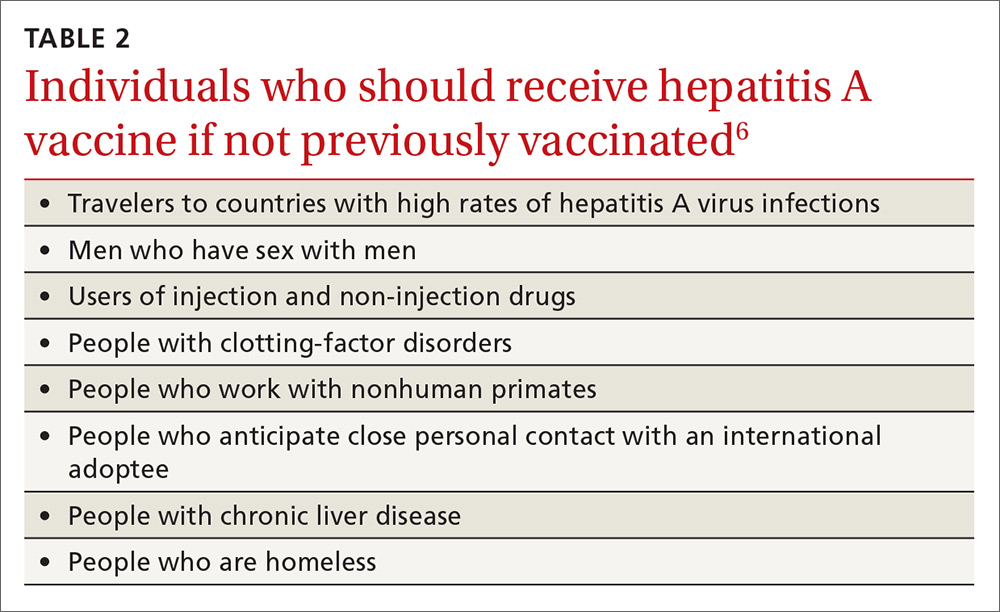

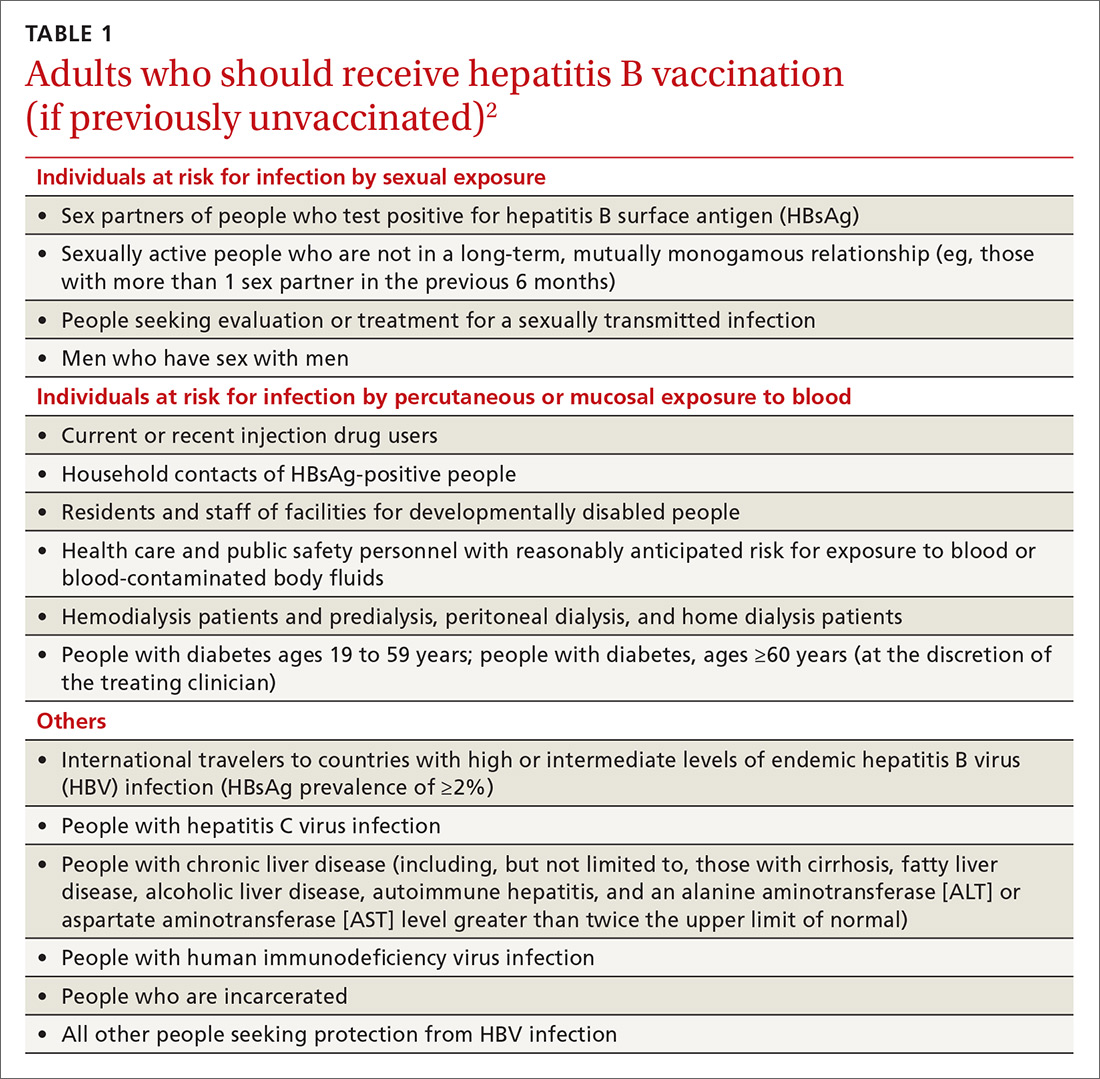

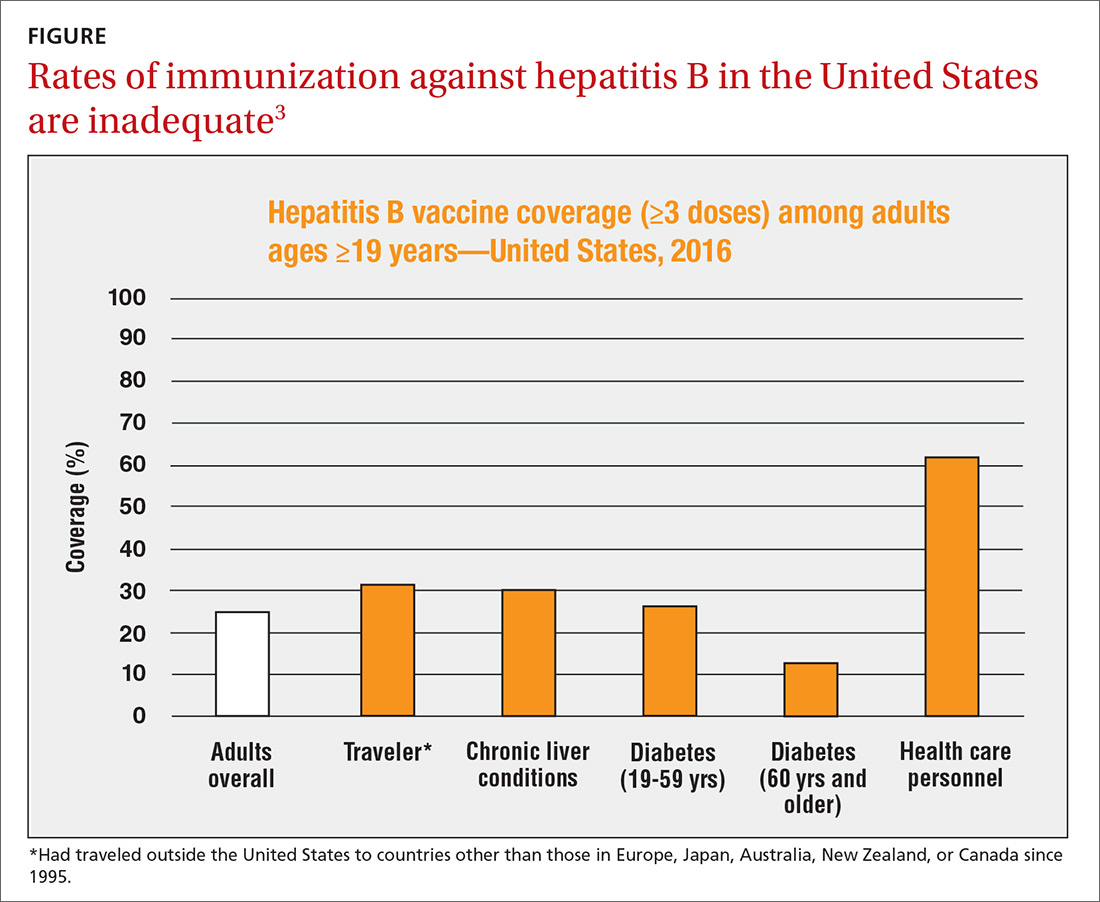

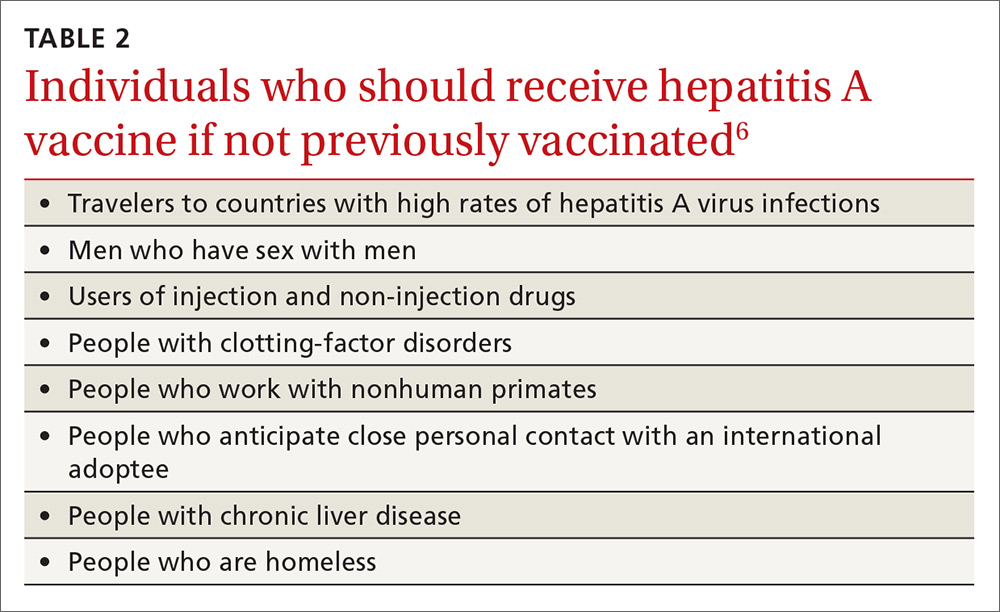

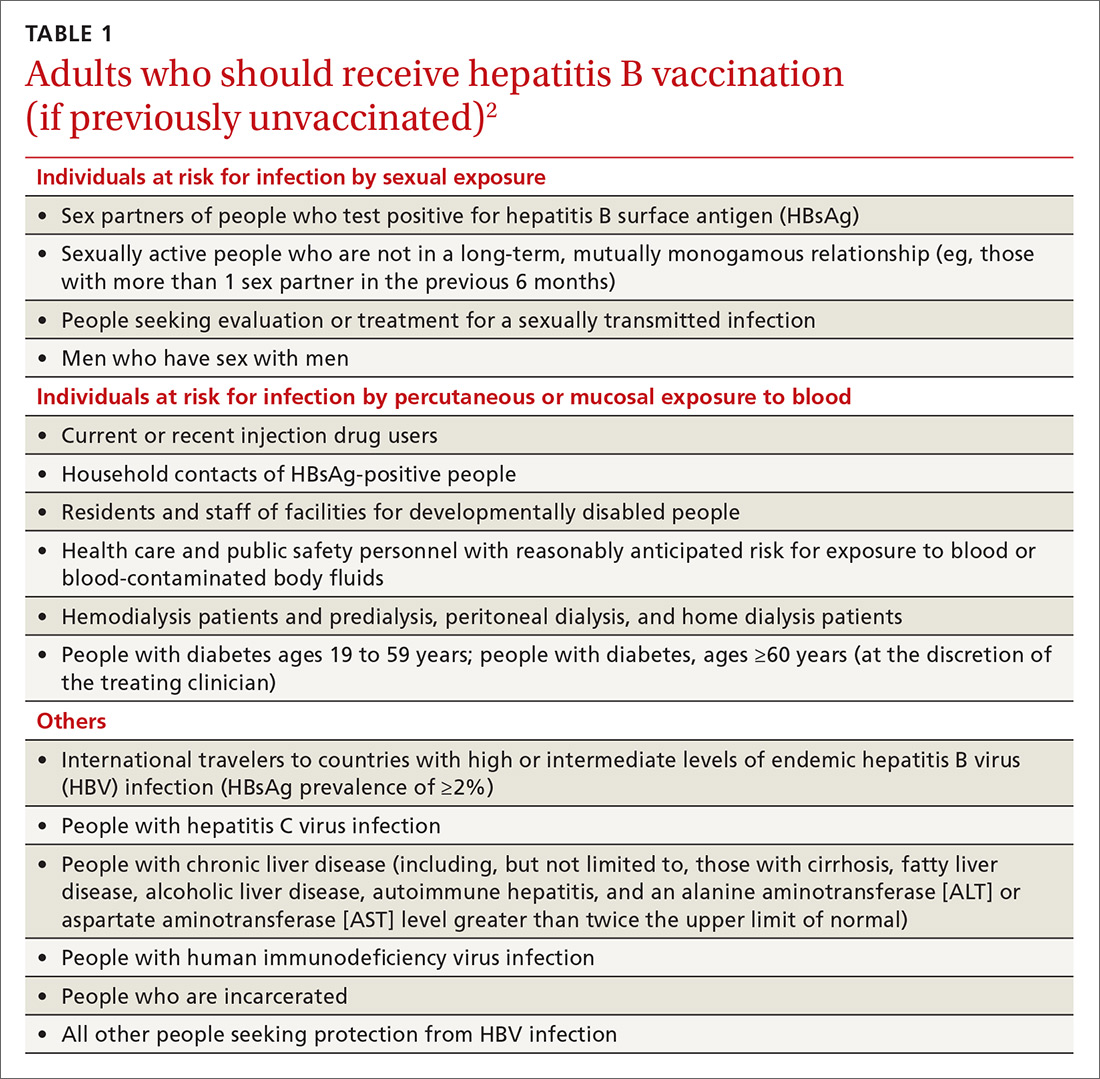

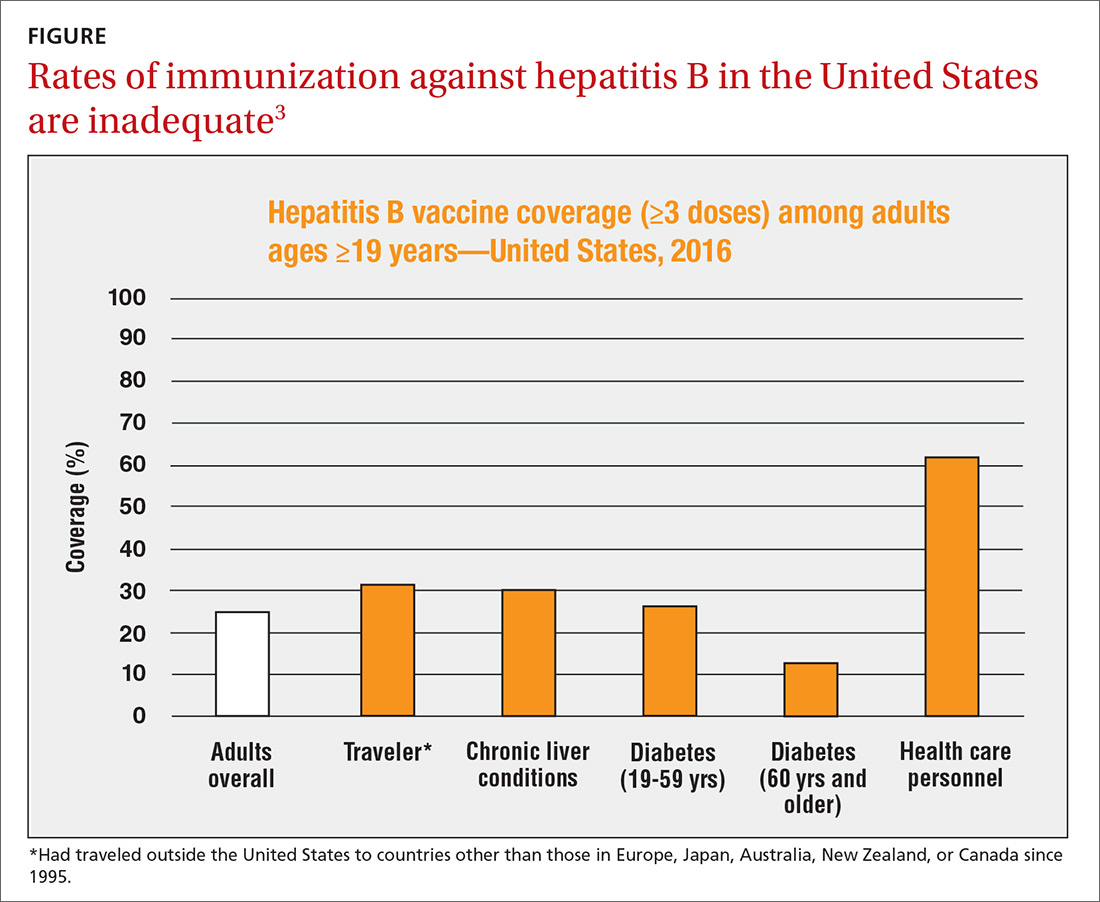

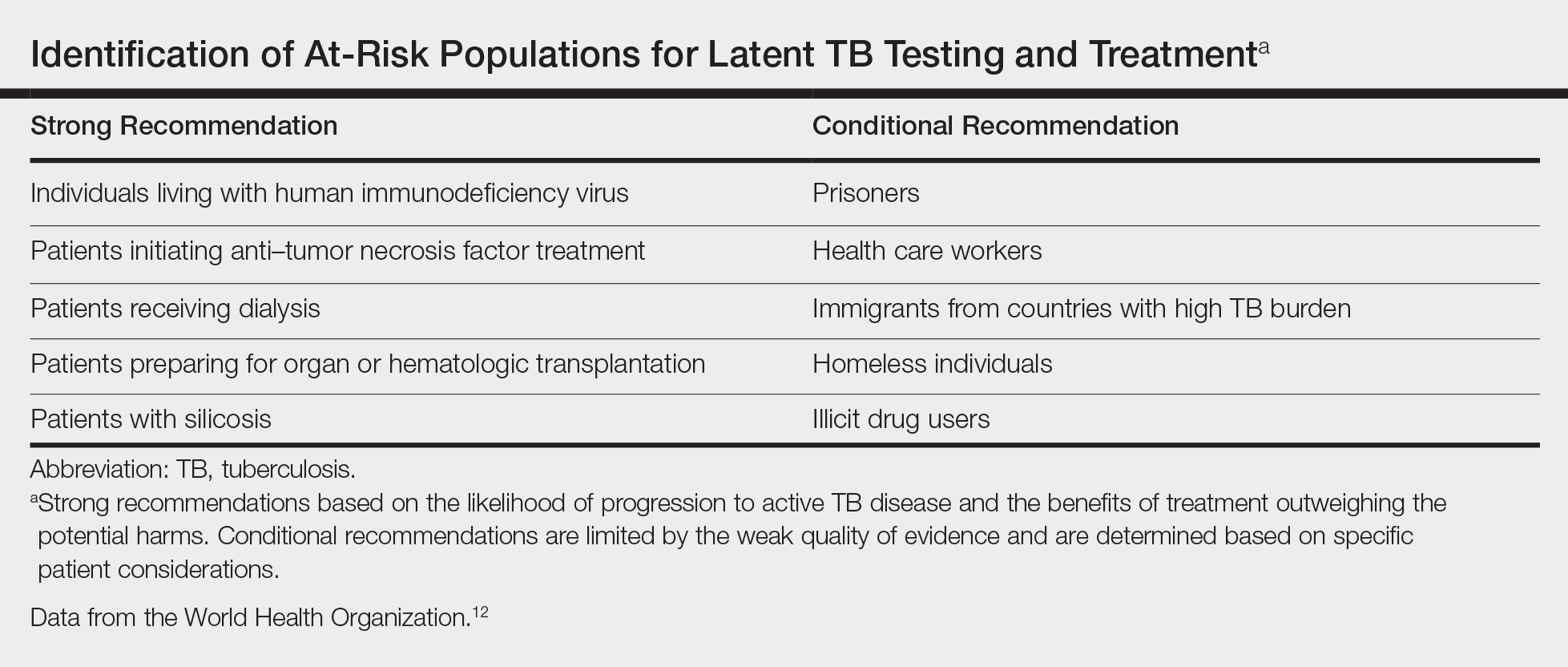

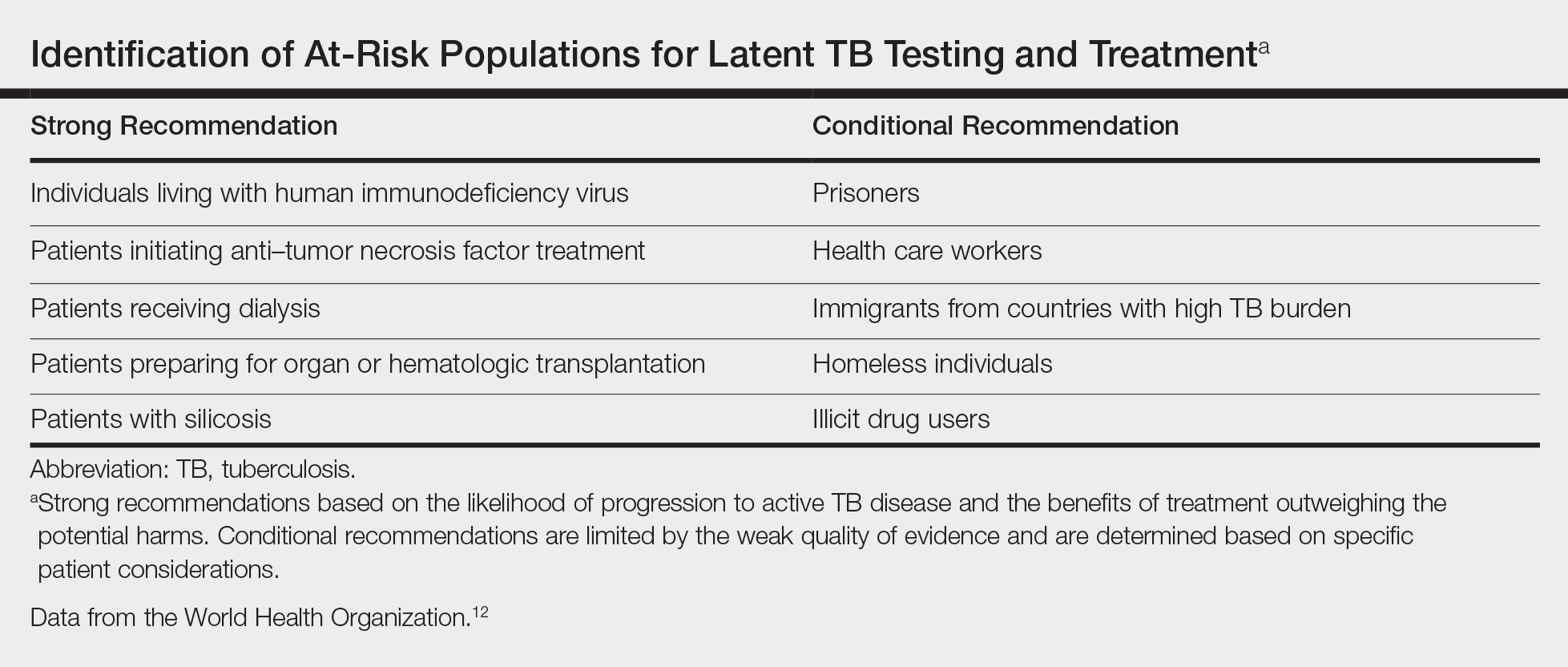

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

One of the most important commitments family physicians can undertake in protecting the health of their patients and communities is to ensure that their patients are fully vaccinated. This task is increasingly complicated as new vaccines are approved every year and recommendations change regarding new and established vaccines. To assist primary care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) annually updates 2 immunization schedules—one for children and adolescents, and one for adults. These schedules are available on the CDC Web site (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html).

These updates originate from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which meets 3 times a year to consider and adopt changes to the schedules. During 2018, relatively few new recommendations were adopted. The September 2018 Practice Alert1 in this journal covered the updated recommendations for influenza immunization, which included reinstating live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) to the active list of influenza vaccines.

This current Practice Alert reviews 3 additional updates: 1) a new hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine; 2) updated recommendations for the use of hepatitis A (HepA) vaccine for post-exposure prevention and before travel; and 3) inclusion of the homeless among those who should be routinely vaccinated with HepA vaccine.

Hepatitis B: New 2-dose product

As of 2015, the annual incidence of new hepatitis B cases had declined by 88.5% since the first HepB vaccine was licensed in 1981 and recommendations for its routine use were issued in 1982.2 The HepB vaccine products available in the United States are 2 single-antigen products, Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.). Both can be used in all age groups, starting at birth, in a 3-dose series. HepB vaccine is also available in 2 combination products: Pediarix, containing HepB, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis, and inactivated poliovirus (GlaxoSmithKline), approved for use in children 6 weeks to 6 years old; and Twinrix (GlaxoSmithKline), which contains both HepB and HepA and is approved for use in adults 18 years and older.

The HepB vaccine is recommended for all children and unvaccinated adolescents as part of the routine vaccination schedule. It is also recommended for unvaccinated adults with specific risks (TABLE 12). However, the rate of HepB vaccination in adults for whom it is recommended is suboptimal (FIGURE),3 and just a little more than half of adults who start a 3-dose series of HepB complete it.4A new vaccine against hepatitis B, HEPLISAV-B (Dynavax Technologies), was licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration in late 2017. ACIP now recommends it as an option along with other available HepB products. HEPLISAV-B is given in 2 doses separated by 1 month. It is hoped that this shortened 2-dose series will increase the number of adults who achieve full vaccination. In addition, it appears that HEPLISAV-B provides higher levels of protection in some high-risk groups—those with type 2 diabetes or chronic kidney disease.3 However, initial safety studies have shown a small absolute increase in cardiac events after vaccination with HEPLISAV-B. Post-marketing surveillance will be needed to show whether this is causal or coincidental.3

As with other HepB products, use of HEPLISAV-B should follow the latest CDC directives on who to test serologically for prior immunity, and on post-vaccination testing to ensure protective antibody levels were achieved.2 It is best to complete a HepB series with the same product, but, if necessary, a combination of products at different doses can be used to complete the HepB series. Any such combination should include 3 doses, even if one of the doses is HEPLISAV-B.

Hepatitis A: Vaccination assumes greater importance for more people

A Practice Alert in early 2018 described a series of outbreaks of hepatitis A around the country and the high rates of associated hospitalizations.5 These outbreaks have occurred primarily among the homeless and their contacts and those who use illicit drugs. This nationwide outbreak has now spread, resulting in more than 7500 cases since July 1, 2016.6 The progress of this epidemic can be viewed on the CDC Web site

Continue to: Remember that the current recommendation...

Remember that the current recommendation is to vaccinate all children 12 to 23 months old with HepA, in 2 separate doses. Two single-antigen HepA products are available: Havrix (GSK) and Vaqta (Merck). For the 2-dose sequence, Havrix is given at 0 and 6 to 12 months; Vaqta at 0 and 6 to 18 months. Even a single dose will provide protection for up to 11 years. In addition to these vaccines, there is the combination HepA and HepB vaccine (Twinrix) mentioned earlier.

Previous recommendations for preventing hepatitis A after exposure, made in 2007, stated that HepA vaccine was preferred for healthy individuals ages 12 months through 40 years, while immune globulin (IG) was preferred for adults older than 40, infants before their first birthday, immunocompromised individuals, those with chronic liver disease, and those for whom HepA vaccine is contraindicated.8 The 2007 recommendations also advised vaccinating individuals traveling to countries with intermediate to high hepatitis A endemicity.

A single dose of HepA vaccine was recommended for all those 12 months or older, although older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with chronic liver disease or other chronic medical conditions planning to visit an endemic area in ≤ 2 weeks were supposed to receive the initial dose of vaccine and could also receive IG (0.02 mL/kg) if their provider advised it. Travelers who declined vaccination, those younger than 12 months, or those allergic to a vaccine component could receive a single dose of IG (0.02 mL/kg), which provides protection up to 3 months.

Several factors influenced ACIP to reconsider both the pre- and post-exposure recommendations. Regarding IG, evidence of its decreased potency over time led the committee to increase the recommended dose (see below). IG also must be re-administered every 2 months, the supply of the product is questionable, and many health care facilities do not stock it. By comparison, HepA vaccine offers the advantages of easier administration, inducing active immunity, and providing longer protection. Another issue involved infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling to an area with endemic measles transmission and who must therefore receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. MMR and IG should not be co-administered, and, for infants, the health risk from measles outweighs that from hepatitis A.

Updated recommendations. After considering all this information, ACIP made the following changes to its hepatitis A virus (HAV) prevention recommendations (in addition to adding homeless people to the list of HepA vaccine recipients)9:

- Administer HepA vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis to all individuals 12 months and older.

- IG may be administered, in addition to HepA vaccine, to those older than 40 years, depending on the provider’s risk assessment (degree of exposure and medical conditions that might lead to severe complications from HAV infection). The recommended IG dose is now 0.1 mL/kg for post-exposure prevention; it is 0.1 to 0.2 mL/kg for pre-exposure prophylaxis for travelers, depending on the length of planned travel.

- Administer HepA vaccine alone to infants ages 6 to 11 months traveling outside the United States when protection against hepatitis A is recommended.

These recommendations have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.9

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC recommendations for the 2018-2019 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:550-553.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31.

3. CDC. Schillie S. HEPLISAV-B: considerations and proposed recommendations, vote. Presented at: meeting of the Hepatitis Work Group, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 21, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-02/Hepatitis-03-Schillie-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

4. Nelson JC, Bittner RC, Bounds L, et al. Compliance with multiple-dose vaccine schedules among older children, adolescents, and adults: results from a vaccine safety datalink study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S389-S397.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:30-32.

6. CDC. Nelson N. Background – hepatitis A among the homeless. Presented at: meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; October 24, 2018; Atlanta, Ga. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2018-10/Hepatitis-02-Nelson-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2019.

7. CDC. 2017 – Outbreaks of hepatitis A in multiple states among people who use drugs and/or people who are homeless. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/2017March-HepatitisA.htm. Accessed January 19, 2019.

8. CDC. Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1080-1084. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5641a3.htm. Accessed February 9, 2019.

9. Nelson NP, Link-Gelles R, Hofmeister MG, et al. Update: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of hepatitis A vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis and for preexposure prophylaxis for international travel. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1216-1220.

Best practices lower postsepsis risk, but only if implemented

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”

A 2017 report estimated that 1.7 million adults were hospitalized for sepsis in the United States in 2014, and 270,000 died (JAMA. 2017;318[13]:1241-9). Age-adjusted sepsis death rates in the United States are highest in states in the Eastern and Southern regions, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested; North Carolina has the 32nd-worst sepsis death rate in the country (12.4 deaths per 100,000 population).

Dr. Taylor said some recent news about sepsis is promising. “We’ve seen decreasing mortality rates from initiatives that improve the early detection of sepsis and rapid delivery of antibiotics, fluids, and other treatment. However, there is growing evidence that patients who survive an episode of sepsis face residual health deficits. Many sepsis survivors are left with new functional, cognitive, or mental health declines or worsening of their underlying comorbidities. Unfortunately, these patients have high rates of mortality and hospital readmission that persist for multiple years after hospitalization.”

Indeed, a 2013 report linked sepsis to significantly higher mortality risk over 5 years, after accounting for comorbidities. Postsepsis patients were 13 times more likely to die over the first year after hospitalization than counterparts who didn’t have sepsis (BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004283).

For the new study, Dr. Taylor said, “we aimed to evaluate current care practices with the hope to identify a postsepsis management strategy that could help nudge these patients towards a more meaningful recovery.”

The researchers retrospectively tracked a random sample of 100 patients (median age, 63 years), who were discharged following an admission for sepsis in 2017. They were treated at eight acute care hospitals in western and central North Carolina and hospitalized for a median of 5 days; 75 were discharged to home (17 received home health services there), 17 went to skilled nursing or long-term care facilities, and 8 went to hospice or another location.

The researchers analyzed whether the patients received four kinds of postsepsis care within 90 days, as recommended by a 2018 review: screening for common functional impairments (53/100 patients received this screening); adjustment of medications as needed following discharge (53/100 patients); monitoring for common and preventable causes for health deterioration, such as infection, chronic lung disease, or heart failure exacerbation (37/100); and assessment for palliative care (25/100 patients) (JAMA. 2018;319[1]:62-75).

Within 90 days of discharge, 34 patients were readmitted and 17 died. The 32 patients who received at least two recommended kinds of postsepsis care were less likely to be readmitted or die (9/32) than those who got zero or one recommended kind of care (34/68; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence ratio, 0.09-0.82).

In an interview, study coauthor Marc Kowalkowski, PhD, associate professor with Atrium Health’s Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, said he was hesitant to only allocate blame to hospitals or outpatient providers. “Transition out of the hospital is an extremely complex event, involving often fragmented care settings, and sepsis patients tend to be more complicated than other patients. It probably makes sense to provide an added layer of support during the transition out of the hospital for patients who are at high risk for poor outcomes.”

Overall, the findings are “a call for clinicians to realize sepsis is more than just an acute illness. The combination of a growing number of sepsis survivors and the increased health problems following an episode of sepsis creates an urgent public health challenge,” Dr. Taylor said.

Is more home health an important part of a solution? It may be helpful, Dr. Taylor said, but “our data suggest that there really needs to be better coordination to bridge between the inpatient and outpatient transition. We are currently conducting a randomized study to investigate whether these types of care processes can be delivered effectively through a nurse navigator to improve patient outcomes.”

Fortunately, she said, the findings suggest “we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to work on implementation of strategies for care processes that we are already familiar with.”

No funding was reported. None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Taylor SP et al. CCC48, Abstract 1320.

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”

A 2017 report estimated that 1.7 million adults were hospitalized for sepsis in the United States in 2014, and 270,000 died (JAMA. 2017;318[13]:1241-9). Age-adjusted sepsis death rates in the United States are highest in states in the Eastern and Southern regions, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested; North Carolina has the 32nd-worst sepsis death rate in the country (12.4 deaths per 100,000 population).

Dr. Taylor said some recent news about sepsis is promising. “We’ve seen decreasing mortality rates from initiatives that improve the early detection of sepsis and rapid delivery of antibiotics, fluids, and other treatment. However, there is growing evidence that patients who survive an episode of sepsis face residual health deficits. Many sepsis survivors are left with new functional, cognitive, or mental health declines or worsening of their underlying comorbidities. Unfortunately, these patients have high rates of mortality and hospital readmission that persist for multiple years after hospitalization.”

Indeed, a 2013 report linked sepsis to significantly higher mortality risk over 5 years, after accounting for comorbidities. Postsepsis patients were 13 times more likely to die over the first year after hospitalization than counterparts who didn’t have sepsis (BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004283).

For the new study, Dr. Taylor said, “we aimed to evaluate current care practices with the hope to identify a postsepsis management strategy that could help nudge these patients towards a more meaningful recovery.”

The researchers retrospectively tracked a random sample of 100 patients (median age, 63 years), who were discharged following an admission for sepsis in 2017. They were treated at eight acute care hospitals in western and central North Carolina and hospitalized for a median of 5 days; 75 were discharged to home (17 received home health services there), 17 went to skilled nursing or long-term care facilities, and 8 went to hospice or another location.

The researchers analyzed whether the patients received four kinds of postsepsis care within 90 days, as recommended by a 2018 review: screening for common functional impairments (53/100 patients received this screening); adjustment of medications as needed following discharge (53/100 patients); monitoring for common and preventable causes for health deterioration, such as infection, chronic lung disease, or heart failure exacerbation (37/100); and assessment for palliative care (25/100 patients) (JAMA. 2018;319[1]:62-75).

Within 90 days of discharge, 34 patients were readmitted and 17 died. The 32 patients who received at least two recommended kinds of postsepsis care were less likely to be readmitted or die (9/32) than those who got zero or one recommended kind of care (34/68; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence ratio, 0.09-0.82).

In an interview, study coauthor Marc Kowalkowski, PhD, associate professor with Atrium Health’s Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, said he was hesitant to only allocate blame to hospitals or outpatient providers. “Transition out of the hospital is an extremely complex event, involving often fragmented care settings, and sepsis patients tend to be more complicated than other patients. It probably makes sense to provide an added layer of support during the transition out of the hospital for patients who are at high risk for poor outcomes.”

Overall, the findings are “a call for clinicians to realize sepsis is more than just an acute illness. The combination of a growing number of sepsis survivors and the increased health problems following an episode of sepsis creates an urgent public health challenge,” Dr. Taylor said.

Is more home health an important part of a solution? It may be helpful, Dr. Taylor said, but “our data suggest that there really needs to be better coordination to bridge between the inpatient and outpatient transition. We are currently conducting a randomized study to investigate whether these types of care processes can be delivered effectively through a nurse navigator to improve patient outcomes.”

Fortunately, she said, the findings suggest “we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to work on implementation of strategies for care processes that we are already familiar with.”

No funding was reported. None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Taylor SP et al. CCC48, Abstract 1320.

SAN DIEGO – North Carolina health care workers often failed to provide best-practice follow-up to patients who were released after hospitalization for sepsis, a small study has found. There may be a cost to this gap:

“It’s disappointing to see that we are not providing these seemingly common-sense care processes to our sepsis patients at discharge,” said study lead author Stephanie Parks Taylor, MD, of Atrium Health’s Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, in an interview following the presentation of the study findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “We need to develop and implement strategies to improve outcomes for sepsis patients, not just while they are in the hospital, but after discharge as well.”

A 2017 report estimated that 1.7 million adults were hospitalized for sepsis in the United States in 2014, and 270,000 died (JAMA. 2017;318[13]:1241-9). Age-adjusted sepsis death rates in the United States are highest in states in the Eastern and Southern regions, a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested; North Carolina has the 32nd-worst sepsis death rate in the country (12.4 deaths per 100,000 population).

Dr. Taylor said some recent news about sepsis is promising. “We’ve seen decreasing mortality rates from initiatives that improve the early detection of sepsis and rapid delivery of antibiotics, fluids, and other treatment. However, there is growing evidence that patients who survive an episode of sepsis face residual health deficits. Many sepsis survivors are left with new functional, cognitive, or mental health declines or worsening of their underlying comorbidities. Unfortunately, these patients have high rates of mortality and hospital readmission that persist for multiple years after hospitalization.”

Indeed, a 2013 report linked sepsis to significantly higher mortality risk over 5 years, after accounting for comorbidities. Postsepsis patients were 13 times more likely to die over the first year after hospitalization than counterparts who didn’t have sepsis (BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004283).

For the new study, Dr. Taylor said, “we aimed to evaluate current care practices with the hope to identify a postsepsis management strategy that could help nudge these patients towards a more meaningful recovery.”

The researchers retrospectively tracked a random sample of 100 patients (median age, 63 years), who were discharged following an admission for sepsis in 2017. They were treated at eight acute care hospitals in western and central North Carolina and hospitalized for a median of 5 days; 75 were discharged to home (17 received home health services there), 17 went to skilled nursing or long-term care facilities, and 8 went to hospice or another location.

The researchers analyzed whether the patients received four kinds of postsepsis care within 90 days, as recommended by a 2018 review: screening for common functional impairments (53/100 patients received this screening); adjustment of medications as needed following discharge (53/100 patients); monitoring for common and preventable causes for health deterioration, such as infection, chronic lung disease, or heart failure exacerbation (37/100); and assessment for palliative care (25/100 patients) (JAMA. 2018;319[1]:62-75).

Within 90 days of discharge, 34 patients were readmitted and 17 died. The 32 patients who received at least two recommended kinds of postsepsis care were less likely to be readmitted or die (9/32) than those who got zero or one recommended kind of care (34/68; odds ratio, 0.26; 95% confidence ratio, 0.09-0.82).

In an interview, study coauthor Marc Kowalkowski, PhD, associate professor with Atrium Health’s Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation, said he was hesitant to only allocate blame to hospitals or outpatient providers. “Transition out of the hospital is an extremely complex event, involving often fragmented care settings, and sepsis patients tend to be more complicated than other patients. It probably makes sense to provide an added layer of support during the transition out of the hospital for patients who are at high risk for poor outcomes.”

Overall, the findings are “a call for clinicians to realize sepsis is more than just an acute illness. The combination of a growing number of sepsis survivors and the increased health problems following an episode of sepsis creates an urgent public health challenge,” Dr. Taylor said.

Is more home health an important part of a solution? It may be helpful, Dr. Taylor said, but “our data suggest that there really needs to be better coordination to bridge between the inpatient and outpatient transition. We are currently conducting a randomized study to investigate whether these types of care processes can be delivered effectively through a nurse navigator to improve patient outcomes.”

Fortunately, she said, the findings suggest “we don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to work on implementation of strategies for care processes that we are already familiar with.”

No funding was reported. None of the study authors reported relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Taylor SP et al. CCC48, Abstract 1320.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Rounding team boosts ICU liberation efforts

SAN DIEGO – A rounding team formed to oversee implementation of a bundle of ICU interventions reduced the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and the number of ventilation days, as well as the ICU and hospital length of stay, according to a new study conducted at a level 1 trauma center in California. The rounding team worked toward optimal implementation of the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s ABCDEF bundle, part of the society’s ICU liberation initiative.

ABCDEF stands for: Assessment, prevention, and management of pain; Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; Delirium assessment, prevention, and management; Early mobility and exercise; and Family engagement and empowerment.

The Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif., where the study was conducted, was chosen in 2015 to participate in the ICU liberation initiative. The facility serves a population of 3.2 million and sees just under 4,000 trauma patients per year.

After a 6-month retrospective analysis, the team members at the medical center realized they needed to improve ABCDEF implementation with respect to evaluating sedation practices and improving delirium assessment.

Before the start of the 17-month collaborative period, they formed an ICU liberation team called SMART, short for Sedation, Mobilization, Assessment Rounding Team, which included representatives from ICU nursing, pharmacy, respiratory therapy, physical therapy, physicians, and administration. They developed a daily rounding tool to help the team implement procedures, with the goal of reducing the continuous infusion of benzodiazepines and increasing intermittent dosing, the use of short-acting medications, and conducting spontaneous awakening and breathing trials. The SMART team made daily rounds to ensure that the ABCDEF bundle was being implemented.

The researchers then continued the analysis for another 12 months after the end of the initiative. During this last phase, the benefits of the SMART team became evident.

“Stick with it. Don’t let up. Don’t quit,” Wade Veneman, a respiratory therapist at the medical center, said in an interview. He presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “It can be particularly difficult in the face of critical care providers who may be skeptical of new initiatives. They think it’s something new, and they hope that it goes away. But this is something we feel we’re going to keep for a long time,” he added.

Mr. Veneman hopes to implement the SMART program in the neurological critical care ICU. The medical director of that unit did not participate in the initial collaborative, but Mr. Veneman hopes to change that. “The data is going to show that his VAP and ventilator days are going up, and everywhere else they’re going down,” he said.

The researchers analyzed data on 1,127 mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. At total of 197 patients were treated 6 months before the implementation of the collaborative, 519 during 17 months of collaborative implementation, and 411 in the 12 months after implementation. There were some differences between the populations: The before group was slightly younger than the after-implementation group (mean 41 vs. 44, P = .04), and the mean Injury Severity Score score was 24 in the before group, 22 during, and 20 after (P = .002). The researchers noted that the differences were clinically significant.

Benzodiazepine use declined, but the effect was statistically significant only in the after population. Continuous use declined from 87% before implementation to 83% during (P = .21) and 53% after (P less than .001). Intermittent use was 57% before implementation, increased to 61% during (P = .44), and fell to 44% after (P less than .001). Delirium assessment performance improved throughout, from 9% before implementation to 42% during (P less than .001) to 73% after implementation (P less than .001).

The VAP rate increased from 3.4% before the SMART program to 4.5% during implementation (P = .53), and then dropped to 0.9% afterward (P = .001). Ventilation days started at a mean of 10.5, then dropped to 9.5 during implementation (P = .30), and 8.2 after implementation (P = .027).

ICU length of stay improved from 10.7 before implementation to 9.3 afterward (P = .021), and overall hospital length of stay went from 17.3 days to 16.3 (P = .005).

The study was not funded. Mr. Veneman has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Veneman W et al. CCC48, Abstract 63.

SAN DIEGO – A rounding team formed to oversee implementation of a bundle of ICU interventions reduced the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and the number of ventilation days, as well as the ICU and hospital length of stay, according to a new study conducted at a level 1 trauma center in California. The rounding team worked toward optimal implementation of the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s ABCDEF bundle, part of the society’s ICU liberation initiative.

ABCDEF stands for: Assessment, prevention, and management of pain; Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; Delirium assessment, prevention, and management; Early mobility and exercise; and Family engagement and empowerment.

The Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif., where the study was conducted, was chosen in 2015 to participate in the ICU liberation initiative. The facility serves a population of 3.2 million and sees just under 4,000 trauma patients per year.

After a 6-month retrospective analysis, the team members at the medical center realized they needed to improve ABCDEF implementation with respect to evaluating sedation practices and improving delirium assessment.

Before the start of the 17-month collaborative period, they formed an ICU liberation team called SMART, short for Sedation, Mobilization, Assessment Rounding Team, which included representatives from ICU nursing, pharmacy, respiratory therapy, physical therapy, physicians, and administration. They developed a daily rounding tool to help the team implement procedures, with the goal of reducing the continuous infusion of benzodiazepines and increasing intermittent dosing, the use of short-acting medications, and conducting spontaneous awakening and breathing trials. The SMART team made daily rounds to ensure that the ABCDEF bundle was being implemented.

The researchers then continued the analysis for another 12 months after the end of the initiative. During this last phase, the benefits of the SMART team became evident.

“Stick with it. Don’t let up. Don’t quit,” Wade Veneman, a respiratory therapist at the medical center, said in an interview. He presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “It can be particularly difficult in the face of critical care providers who may be skeptical of new initiatives. They think it’s something new, and they hope that it goes away. But this is something we feel we’re going to keep for a long time,” he added.

Mr. Veneman hopes to implement the SMART program in the neurological critical care ICU. The medical director of that unit did not participate in the initial collaborative, but Mr. Veneman hopes to change that. “The data is going to show that his VAP and ventilator days are going up, and everywhere else they’re going down,” he said.

The researchers analyzed data on 1,127 mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. At total of 197 patients were treated 6 months before the implementation of the collaborative, 519 during 17 months of collaborative implementation, and 411 in the 12 months after implementation. There were some differences between the populations: The before group was slightly younger than the after-implementation group (mean 41 vs. 44, P = .04), and the mean Injury Severity Score score was 24 in the before group, 22 during, and 20 after (P = .002). The researchers noted that the differences were clinically significant.

Benzodiazepine use declined, but the effect was statistically significant only in the after population. Continuous use declined from 87% before implementation to 83% during (P = .21) and 53% after (P less than .001). Intermittent use was 57% before implementation, increased to 61% during (P = .44), and fell to 44% after (P less than .001). Delirium assessment performance improved throughout, from 9% before implementation to 42% during (P less than .001) to 73% after implementation (P less than .001).

The VAP rate increased from 3.4% before the SMART program to 4.5% during implementation (P = .53), and then dropped to 0.9% afterward (P = .001). Ventilation days started at a mean of 10.5, then dropped to 9.5 during implementation (P = .30), and 8.2 after implementation (P = .027).

ICU length of stay improved from 10.7 before implementation to 9.3 afterward (P = .021), and overall hospital length of stay went from 17.3 days to 16.3 (P = .005).

The study was not funded. Mr. Veneman has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Veneman W et al. CCC48, Abstract 63.

SAN DIEGO – A rounding team formed to oversee implementation of a bundle of ICU interventions reduced the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and the number of ventilation days, as well as the ICU and hospital length of stay, according to a new study conducted at a level 1 trauma center in California. The rounding team worked toward optimal implementation of the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s ABCDEF bundle, part of the society’s ICU liberation initiative.

ABCDEF stands for: Assessment, prevention, and management of pain; Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials; Choice of analgesia and sedation; Delirium assessment, prevention, and management; Early mobility and exercise; and Family engagement and empowerment.

The Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno, Calif., where the study was conducted, was chosen in 2015 to participate in the ICU liberation initiative. The facility serves a population of 3.2 million and sees just under 4,000 trauma patients per year.

After a 6-month retrospective analysis, the team members at the medical center realized they needed to improve ABCDEF implementation with respect to evaluating sedation practices and improving delirium assessment.

Before the start of the 17-month collaborative period, they formed an ICU liberation team called SMART, short for Sedation, Mobilization, Assessment Rounding Team, which included representatives from ICU nursing, pharmacy, respiratory therapy, physical therapy, physicians, and administration. They developed a daily rounding tool to help the team implement procedures, with the goal of reducing the continuous infusion of benzodiazepines and increasing intermittent dosing, the use of short-acting medications, and conducting spontaneous awakening and breathing trials. The SMART team made daily rounds to ensure that the ABCDEF bundle was being implemented.

The researchers then continued the analysis for another 12 months after the end of the initiative. During this last phase, the benefits of the SMART team became evident.

“Stick with it. Don’t let up. Don’t quit,” Wade Veneman, a respiratory therapist at the medical center, said in an interview. He presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “It can be particularly difficult in the face of critical care providers who may be skeptical of new initiatives. They think it’s something new, and they hope that it goes away. But this is something we feel we’re going to keep for a long time,” he added.

Mr. Veneman hopes to implement the SMART program in the neurological critical care ICU. The medical director of that unit did not participate in the initial collaborative, but Mr. Veneman hopes to change that. “The data is going to show that his VAP and ventilator days are going up, and everywhere else they’re going down,” he said.

The researchers analyzed data on 1,127 mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. At total of 197 patients were treated 6 months before the implementation of the collaborative, 519 during 17 months of collaborative implementation, and 411 in the 12 months after implementation. There were some differences between the populations: The before group was slightly younger than the after-implementation group (mean 41 vs. 44, P = .04), and the mean Injury Severity Score score was 24 in the before group, 22 during, and 20 after (P = .002). The researchers noted that the differences were clinically significant.

Benzodiazepine use declined, but the effect was statistically significant only in the after population. Continuous use declined from 87% before implementation to 83% during (P = .21) and 53% after (P less than .001). Intermittent use was 57% before implementation, increased to 61% during (P = .44), and fell to 44% after (P less than .001). Delirium assessment performance improved throughout, from 9% before implementation to 42% during (P less than .001) to 73% after implementation (P less than .001).

The VAP rate increased from 3.4% before the SMART program to 4.5% during implementation (P = .53), and then dropped to 0.9% afterward (P = .001). Ventilation days started at a mean of 10.5, then dropped to 9.5 during implementation (P = .30), and 8.2 after implementation (P = .027).

ICU length of stay improved from 10.7 before implementation to 9.3 afterward (P = .021), and overall hospital length of stay went from 17.3 days to 16.3 (P = .005).

The study was not funded. Mr. Veneman has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Veneman W et al. CCC48, Abstract 63.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

HCV treatment with DAA regimens linked to reduced diabetes risk

SEATTLE – Treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) with new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens is associated with improved glucose control and reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when compared to treatment with pegylated interferon/ribavirin (PEG/RBV ) and untreated controls, according to a new analysis of the Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans.

“Previously, people who had diabetes were considered slightly more difficult to treat because their virologic response was a little lower, but now this is not the case, and we have the added benefit of reducing the incidence of diabetes,” said Adeel Butt, MD, professor of medicine and health care policy and research at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York and Qatar, in an interview. Dr. Butt presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The incidence of diabetes dropped in the overall treated cohort, compared with untreated patients, but this benefit was driven by the effect of DAAs, as there was no significant difference between PEG/RBV–treated patients and controls. “It’s another reason to argue with people who make it difficult to treat. Our biggest barriers to treating everyone with hepatitis C has to do with reimbursement and the capacity of the health care system, and this is another reason that we need to overcome those barriers. It’s an important insight that provides one more reason to try to continue to eradicate hepatitis C in our population,” said Robert Schooley, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, in an interview.

Patients may also need some reassurance, given concerns that have arisen over the potential for older regimens to cause diabetes. Dr. Butt cited an example of a patient who has an acute myocardial infarction, has a high body mass, and wants to know if DAAs will help or hurt them. “We see [such patients] frequently. This is pretty reassuring not only that DAAs don’t increase risk, but they actually decrease the risk of diabetes as opposed to older treatments. There is a growing body of evidence that non–liver [related conditions] significantly improve with treatment,” he said.

The results could also help prioritize patients for treatment. “It may be important to the patients who are at elevated risk of developing diabetes. They may need to be monitored more closely and offered treatment earlier, perhaps, but that requires more study,” said Dr. Butt.

The researchers excluded patients with HIV or hepatitis B virus, and those who had prevalent diabetes. The cohort included 26,043 treated patients and 26,043 propensity score–matched untreated control patients. Treated patients underwent at least 8 weeks of DAA or 24 weeks of PEG/RBV. Demographically, 54% of patients were white, 29% were black, 3% were Hispanic, and 96% of the patients were male. About one-third had a body mass index of 30 or above.

The incidence of diabetes was 20.6 per 1,000 person-years of follow-up among untreated patients, compared with 15.5 among treated patients (P less than .0001). The incidence was 19.8 in patients treated with PEG/RBV (P =.39) and 9.9 in those treated with DAAs (P less than. 001; hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes in those with a sustained viral response (SVR) was 13.3 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 19.2 in patients with no SVR (P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes was lower in treated patients regardless of baseline FIB-4 (Fibrosis-4, a liver fibrosis score) levels.

The study was funded by Gilead. Dr. Butt has had research grants from Gilead and Dr. Schooley is on Gilead’s scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: A Butt et al. CROI 2019. Abstract 88.

SEATTLE – Treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) with new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens is associated with improved glucose control and reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when compared to treatment with pegylated interferon/ribavirin (PEG/RBV ) and untreated controls, according to a new analysis of the Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans.

“Previously, people who had diabetes were considered slightly more difficult to treat because their virologic response was a little lower, but now this is not the case, and we have the added benefit of reducing the incidence of diabetes,” said Adeel Butt, MD, professor of medicine and health care policy and research at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York and Qatar, in an interview. Dr. Butt presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The incidence of diabetes dropped in the overall treated cohort, compared with untreated patients, but this benefit was driven by the effect of DAAs, as there was no significant difference between PEG/RBV–treated patients and controls. “It’s another reason to argue with people who make it difficult to treat. Our biggest barriers to treating everyone with hepatitis C has to do with reimbursement and the capacity of the health care system, and this is another reason that we need to overcome those barriers. It’s an important insight that provides one more reason to try to continue to eradicate hepatitis C in our population,” said Robert Schooley, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, in an interview.

Patients may also need some reassurance, given concerns that have arisen over the potential for older regimens to cause diabetes. Dr. Butt cited an example of a patient who has an acute myocardial infarction, has a high body mass, and wants to know if DAAs will help or hurt them. “We see [such patients] frequently. This is pretty reassuring not only that DAAs don’t increase risk, but they actually decrease the risk of diabetes as opposed to older treatments. There is a growing body of evidence that non–liver [related conditions] significantly improve with treatment,” he said.

The results could also help prioritize patients for treatment. “It may be important to the patients who are at elevated risk of developing diabetes. They may need to be monitored more closely and offered treatment earlier, perhaps, but that requires more study,” said Dr. Butt.

The researchers excluded patients with HIV or hepatitis B virus, and those who had prevalent diabetes. The cohort included 26,043 treated patients and 26,043 propensity score–matched untreated control patients. Treated patients underwent at least 8 weeks of DAA or 24 weeks of PEG/RBV. Demographically, 54% of patients were white, 29% were black, 3% were Hispanic, and 96% of the patients were male. About one-third had a body mass index of 30 or above.

The incidence of diabetes was 20.6 per 1,000 person-years of follow-up among untreated patients, compared with 15.5 among treated patients (P less than .0001). The incidence was 19.8 in patients treated with PEG/RBV (P =.39) and 9.9 in those treated with DAAs (P less than. 001; hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes in those with a sustained viral response (SVR) was 13.3 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 19.2 in patients with no SVR (P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes was lower in treated patients regardless of baseline FIB-4 (Fibrosis-4, a liver fibrosis score) levels.

The study was funded by Gilead. Dr. Butt has had research grants from Gilead and Dr. Schooley is on Gilead’s scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: A Butt et al. CROI 2019. Abstract 88.

SEATTLE – Treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) with new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens is associated with improved glucose control and reduced incidence of type 2 diabetes when compared to treatment with pegylated interferon/ribavirin (PEG/RBV ) and untreated controls, according to a new analysis of the Electronically Retrieved Cohort of HCV Infected Veterans.

“Previously, people who had diabetes were considered slightly more difficult to treat because their virologic response was a little lower, but now this is not the case, and we have the added benefit of reducing the incidence of diabetes,” said Adeel Butt, MD, professor of medicine and health care policy and research at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York and Qatar, in an interview. Dr. Butt presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The incidence of diabetes dropped in the overall treated cohort, compared with untreated patients, but this benefit was driven by the effect of DAAs, as there was no significant difference between PEG/RBV–treated patients and controls. “It’s another reason to argue with people who make it difficult to treat. Our biggest barriers to treating everyone with hepatitis C has to do with reimbursement and the capacity of the health care system, and this is another reason that we need to overcome those barriers. It’s an important insight that provides one more reason to try to continue to eradicate hepatitis C in our population,” said Robert Schooley, MD, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, in an interview.

Patients may also need some reassurance, given concerns that have arisen over the potential for older regimens to cause diabetes. Dr. Butt cited an example of a patient who has an acute myocardial infarction, has a high body mass, and wants to know if DAAs will help or hurt them. “We see [such patients] frequently. This is pretty reassuring not only that DAAs don’t increase risk, but they actually decrease the risk of diabetes as opposed to older treatments. There is a growing body of evidence that non–liver [related conditions] significantly improve with treatment,” he said.

The results could also help prioritize patients for treatment. “It may be important to the patients who are at elevated risk of developing diabetes. They may need to be monitored more closely and offered treatment earlier, perhaps, but that requires more study,” said Dr. Butt.

The researchers excluded patients with HIV or hepatitis B virus, and those who had prevalent diabetes. The cohort included 26,043 treated patients and 26,043 propensity score–matched untreated control patients. Treated patients underwent at least 8 weeks of DAA or 24 weeks of PEG/RBV. Demographically, 54% of patients were white, 29% were black, 3% were Hispanic, and 96% of the patients were male. About one-third had a body mass index of 30 or above.

The incidence of diabetes was 20.6 per 1,000 person-years of follow-up among untreated patients, compared with 15.5 among treated patients (P less than .0001). The incidence was 19.8 in patients treated with PEG/RBV (P =.39) and 9.9 in those treated with DAAs (P less than. 001; hazard ratio, 0.48; P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes in those with a sustained viral response (SVR) was 13.3 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 19.2 in patients with no SVR (P less than .0001). The incidence of diabetes was lower in treated patients regardless of baseline FIB-4 (Fibrosis-4, a liver fibrosis score) levels.

The study was funded by Gilead. Dr. Butt has had research grants from Gilead and Dr. Schooley is on Gilead’s scientific advisory board.

SOURCE: A Butt et al. CROI 2019. Abstract 88.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

One-time, universal hepatitis C testing cost effective, researchers say

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.

Using a computer program called Decision Maker, they modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal one-time testing, birth cohort screening, and no screening based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS) and 2017 U.S. dollars. They assumed that all HCV-infected patients were treatment naive, treatment eligible, and asymptomatic (for example, had no decompensated cirrhosis). They used efficacy data from the ASTRAL trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir as well as the ENDURANCE, SURVEYOR, and EXPEDITION trials of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. In the model, patients who did not achieve a sustained viral response to treatment went on to complete a 12-week triple direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir).

Based on these assumptions, universal one-time screening and treatment of infected individuals cost less than $50,000 per QALY gained, making it highly cost effective, compared with no screening, the investigators wrote. Universal screening also was highly cost effective when compared with birth cohort screening, costing $11,378 for each QALY gained.

“Analyses performed during the era of first-generation DAAs and interferon-based treatment regimens found birth-cohort screening to be ‘cost effective,’ ” the researchers wrote. “However, the availability of a new generation of highly effective, non–interferon-based oral regimens, with fewer side effects and shorter treatment courses, has altered the dynamic around the question of screening.” They pointed to another recent study in which universal one-time HCV testing was more cost effective than birth cohort screening.

Such findings have spurred experts to revisit guidelines on HCV screening, but universal testing is controversial when some states, counties, and communities have a low HCV prevalence. In the model, universal one-time HCV screening was cost effective (less than $50,000 per QALY gained), compared with birth cohort screening as long as prevalence exceeded 0.07% among adults not born between 1945 and 1965. The current prevalence estimate in this group is 0.29%, which is probably low because it does not account for the rising incidence among younger adults, the researchers wrote. In an ideal world, all clinics and hospitals would implement an HCV testing program, but in the real world of scarce resources, “data regarding the cost-effectiveness threshold can guide local policy decisions by directing testing services to settings in which they generate sufficient benefit for the cost.”

Partial funding came from the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with funding provided through multiple donors to the CDC Foundation’s Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. Dr. Eckman reported grant support from Merck and one coinvestigator reported ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Eckman MH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080.

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.

Using a computer program called Decision Maker, they modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal one-time testing, birth cohort screening, and no screening based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS) and 2017 U.S. dollars. They assumed that all HCV-infected patients were treatment naive, treatment eligible, and asymptomatic (for example, had no decompensated cirrhosis). They used efficacy data from the ASTRAL trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir as well as the ENDURANCE, SURVEYOR, and EXPEDITION trials of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. In the model, patients who did not achieve a sustained viral response to treatment went on to complete a 12-week triple direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir).

Based on these assumptions, universal one-time screening and treatment of infected individuals cost less than $50,000 per QALY gained, making it highly cost effective, compared with no screening, the investigators wrote. Universal screening also was highly cost effective when compared with birth cohort screening, costing $11,378 for each QALY gained.

“Analyses performed during the era of first-generation DAAs and interferon-based treatment regimens found birth-cohort screening to be ‘cost effective,’ ” the researchers wrote. “However, the availability of a new generation of highly effective, non–interferon-based oral regimens, with fewer side effects and shorter treatment courses, has altered the dynamic around the question of screening.” They pointed to another recent study in which universal one-time HCV testing was more cost effective than birth cohort screening.

Such findings have spurred experts to revisit guidelines on HCV screening, but universal testing is controversial when some states, counties, and communities have a low HCV prevalence. In the model, universal one-time HCV screening was cost effective (less than $50,000 per QALY gained), compared with birth cohort screening as long as prevalence exceeded 0.07% among adults not born between 1945 and 1965. The current prevalence estimate in this group is 0.29%, which is probably low because it does not account for the rising incidence among younger adults, the researchers wrote. In an ideal world, all clinics and hospitals would implement an HCV testing program, but in the real world of scarce resources, “data regarding the cost-effectiveness threshold can guide local policy decisions by directing testing services to settings in which they generate sufficient benefit for the cost.”

Partial funding came from the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with funding provided through multiple donors to the CDC Foundation’s Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. Dr. Eckman reported grant support from Merck and one coinvestigator reported ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Eckman MH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080.

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.