User login

Very early ART may benefit infants with HIV

SEATTLE – Antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the earliest weeks of life is associated with reduced time to suppression, according to a new study. Each week that treatment was delayed, patients had a 35% reduction in odds of achieving earlier viral load (VL) suppression.

Previous research had already shown that patients treated in the first year of life have better outcomes, including shortened time to viral suppression, and a lower reservoir size. Those studies looked at median age of ART start by month, and a review of the literature revealed that no research had been done on the first month.

The research was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections by Sara Domínguez Rodríguez, biostatistician and data manager in the pediatric infectious disease service at Hospital 12 Octubre, Madrid.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 44 patients who were treated in the first 28 days of life, who had uninterrupted ART for at least 2 years, and who had VL measured at least twice during follow-up. Among these, 25 patients received ART in the first week, 19 in weeks 2-4. Patients treated prophylactically with AZT + 3TC (lamivudine) + NVP (nevirapine) any time in the first 15 days of life were considered treated at day 1.

Five of the patients were from the United Kingdom, 23 from Spain, 3 from Italy, and 13 from Thailand. Fifty-seven percent were girls; 35% were preterm. Patients treated in the first week had a higher log10 HIV viral load at ART initiation (P = .02). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to CD4 count at ART initiation.

The time to suppression was not significantly different between the two groups, nor was the percentage of patients suppressed at various time points. Patients treated in the first week had reached suppression more often at 3 months and 6 months, but neither result reached statistical significance.

The small sample size of the study produced a challenge, and that led the team to consider suppression time and age as continuous variables. That revealed a curve that favored treatment in the first week of life: Each week of delay reduced the probability of achieving early viral suppression by 35% (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.92). “This means that if you delay the age at ART in terms of weeks, the probability of achieving suppression (over) time decreases, and this effect is particularly seen in the first year of follow-up,” Dr. Domínguez Rodríguez said in an interview.

Some might have concerns that treating children too early could have adverse effects. This study, though small, showed promising results. “You might think if you treat very early, maybe the child will not tolerate the medicine or keep on with the treatment, and we saw no difference. So that supports treating early,” senior author Pablo Rojo Conejo, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at Hospital 12 de Octubre, said in an interview.

Others in attendance found the results encouraging. “It’s very good news to see that early starting impacts the life of these children,” Filipe de Barros Perini, MD, head of care and treatment of the HIV program at the Brazilian Ministry of Health, said in an interview.

SOURCE: Domínguez Rodríguez S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 44.

SEATTLE – Antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the earliest weeks of life is associated with reduced time to suppression, according to a new study. Each week that treatment was delayed, patients had a 35% reduction in odds of achieving earlier viral load (VL) suppression.

Previous research had already shown that patients treated in the first year of life have better outcomes, including shortened time to viral suppression, and a lower reservoir size. Those studies looked at median age of ART start by month, and a review of the literature revealed that no research had been done on the first month.

The research was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections by Sara Domínguez Rodríguez, biostatistician and data manager in the pediatric infectious disease service at Hospital 12 Octubre, Madrid.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 44 patients who were treated in the first 28 days of life, who had uninterrupted ART for at least 2 years, and who had VL measured at least twice during follow-up. Among these, 25 patients received ART in the first week, 19 in weeks 2-4. Patients treated prophylactically with AZT + 3TC (lamivudine) + NVP (nevirapine) any time in the first 15 days of life were considered treated at day 1.

Five of the patients were from the United Kingdom, 23 from Spain, 3 from Italy, and 13 from Thailand. Fifty-seven percent were girls; 35% were preterm. Patients treated in the first week had a higher log10 HIV viral load at ART initiation (P = .02). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to CD4 count at ART initiation.

The time to suppression was not significantly different between the two groups, nor was the percentage of patients suppressed at various time points. Patients treated in the first week had reached suppression more often at 3 months and 6 months, but neither result reached statistical significance.

The small sample size of the study produced a challenge, and that led the team to consider suppression time and age as continuous variables. That revealed a curve that favored treatment in the first week of life: Each week of delay reduced the probability of achieving early viral suppression by 35% (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.92). “This means that if you delay the age at ART in terms of weeks, the probability of achieving suppression (over) time decreases, and this effect is particularly seen in the first year of follow-up,” Dr. Domínguez Rodríguez said in an interview.

Some might have concerns that treating children too early could have adverse effects. This study, though small, showed promising results. “You might think if you treat very early, maybe the child will not tolerate the medicine or keep on with the treatment, and we saw no difference. So that supports treating early,” senior author Pablo Rojo Conejo, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at Hospital 12 de Octubre, said in an interview.

Others in attendance found the results encouraging. “It’s very good news to see that early starting impacts the life of these children,” Filipe de Barros Perini, MD, head of care and treatment of the HIV program at the Brazilian Ministry of Health, said in an interview.

SOURCE: Domínguez Rodríguez S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 44.

SEATTLE – Antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the earliest weeks of life is associated with reduced time to suppression, according to a new study. Each week that treatment was delayed, patients had a 35% reduction in odds of achieving earlier viral load (VL) suppression.

Previous research had already shown that patients treated in the first year of life have better outcomes, including shortened time to viral suppression, and a lower reservoir size. Those studies looked at median age of ART start by month, and a review of the literature revealed that no research had been done on the first month.

The research was presented at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections by Sara Domínguez Rodríguez, biostatistician and data manager in the pediatric infectious disease service at Hospital 12 Octubre, Madrid.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 44 patients who were treated in the first 28 days of life, who had uninterrupted ART for at least 2 years, and who had VL measured at least twice during follow-up. Among these, 25 patients received ART in the first week, 19 in weeks 2-4. Patients treated prophylactically with AZT + 3TC (lamivudine) + NVP (nevirapine) any time in the first 15 days of life were considered treated at day 1.

Five of the patients were from the United Kingdom, 23 from Spain, 3 from Italy, and 13 from Thailand. Fifty-seven percent were girls; 35% were preterm. Patients treated in the first week had a higher log10 HIV viral load at ART initiation (P = .02). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to CD4 count at ART initiation.

The time to suppression was not significantly different between the two groups, nor was the percentage of patients suppressed at various time points. Patients treated in the first week had reached suppression more often at 3 months and 6 months, but neither result reached statistical significance.

The small sample size of the study produced a challenge, and that led the team to consider suppression time and age as continuous variables. That revealed a curve that favored treatment in the first week of life: Each week of delay reduced the probability of achieving early viral suppression by 35% (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.46-0.92). “This means that if you delay the age at ART in terms of weeks, the probability of achieving suppression (over) time decreases, and this effect is particularly seen in the first year of follow-up,” Dr. Domínguez Rodríguez said in an interview.

Some might have concerns that treating children too early could have adverse effects. This study, though small, showed promising results. “You might think if you treat very early, maybe the child will not tolerate the medicine or keep on with the treatment, and we saw no difference. So that supports treating early,” senior author Pablo Rojo Conejo, PhD, an infectious disease specialist at Hospital 12 de Octubre, said in an interview.

Others in attendance found the results encouraging. “It’s very good news to see that early starting impacts the life of these children,” Filipe de Barros Perini, MD, head of care and treatment of the HIV program at the Brazilian Ministry of Health, said in an interview.

SOURCE: Domínguez Rodríguez S et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 44.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

For now, HIV cure is worse than infection

SEATTLE – The most important thing to know about the apparent HIV cure widely reported in the press recently is that the treatment was worse than the infection, according to John Mellors, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Mellors moderated a presentation at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections about what the cure involved.

An HIV-positive man with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma had an allogeneic bone marrow transplant in 2016 after failing first-line chemotherapy and multiple salvage regimens. His donor was homozygous for a gene mutation that prevents HIV from entering new cells. The transplant took; the man’s hematopoietic system was replaced by one with the anti-HIV mutation; and there’s been no trace of active virus in his system since. He’s been off of antiretrovirals for a year and a half. The cancer hasn’t returned.

He’s been dubbed the “London patient.” He joins the “Berlin patient” as the second person who appears to have been freed of infection following a stem cell transplant with the anti-HIV mutation. The Berlin patient recently identified himself as Timothy Ray Brown; he was in the audience at CROI and was applauded for coming forward and sharing his story.

Mr. Brown received a transplant for acute myeloid leukemia and has been off antiretrovirals now for about a decade with no evidence of viral rebound.

Although it didn’t get much attention at CROI, there was a poster of a similar approach seeming to work in a third patient, also with leukemia. It’s been tried – but failed – in two others: one patient died of their lymphoma and the transplant failed in the other, said lead investigator on the London patient case, Ravindra Gupta, MD, a professor in the division of infection & immunity at University College London.

Dr. Mellors pointed out that “the two people who have been cured had lethal malignancies that were unresponsive to conventional therapy and had the extreme measure of an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not a walk in the park. It has a mortality of 10%-25%, which is completely unacceptable” when “patients feel great on one pill a day” for HIV remission and pretty much have a normal life span.

The transplant reactivated both cytomegalovirus and Epstein Barr virus in the London patient, and he developed graft-versus-host colitis. He survived all three complications.

The take-home message is that “these cases are inspirational. The work ahead is to find out how to deliver the same results with less-extreme measures,” Dr. Mellors said.

The donors for both the London and Berlin patients were homozygous for a delta 32 deletion in the receptor most commonly used by HIV-1 to enter host cells, CCR5. Cells that carry the mutation don’t express the receptor, preventing infection. The mutation prevalence is about 1% among Europeans.

Of the two failed cases, the person who died of lymphoma had a strain of HIV-1 that used a different receptor – CXCR4 – so it’s doubtful the transplant would have worked even if he had survived his cancer.

The London patient wasn’t what’s called an “elite controller,” one of those rare people who suppress HIV without antiretrovirals. His viral loads bounced right back when we was taken off them prior to transplant.

He’s not interested in an active sex life at the moment, Dr. Gupta said, but he might be soon, so Dr. Gupta plans a discussion with him in the near future. Although the London patient could well be immune to HIV that uses the CCR5 receptor, he might not be immune to CXCR4 virus, and he might still be able to produce infectious CCR5 particles. Time will tell.

There was no industry funding for the work. Dr. Gupta is a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and a speaker for Gilead.

SOURCE: Gupta RK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 29.

SEATTLE – The most important thing to know about the apparent HIV cure widely reported in the press recently is that the treatment was worse than the infection, according to John Mellors, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Mellors moderated a presentation at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections about what the cure involved.

An HIV-positive man with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma had an allogeneic bone marrow transplant in 2016 after failing first-line chemotherapy and multiple salvage regimens. His donor was homozygous for a gene mutation that prevents HIV from entering new cells. The transplant took; the man’s hematopoietic system was replaced by one with the anti-HIV mutation; and there’s been no trace of active virus in his system since. He’s been off of antiretrovirals for a year and a half. The cancer hasn’t returned.

He’s been dubbed the “London patient.” He joins the “Berlin patient” as the second person who appears to have been freed of infection following a stem cell transplant with the anti-HIV mutation. The Berlin patient recently identified himself as Timothy Ray Brown; he was in the audience at CROI and was applauded for coming forward and sharing his story.

Mr. Brown received a transplant for acute myeloid leukemia and has been off antiretrovirals now for about a decade with no evidence of viral rebound.

Although it didn’t get much attention at CROI, there was a poster of a similar approach seeming to work in a third patient, also with leukemia. It’s been tried – but failed – in two others: one patient died of their lymphoma and the transplant failed in the other, said lead investigator on the London patient case, Ravindra Gupta, MD, a professor in the division of infection & immunity at University College London.

Dr. Mellors pointed out that “the two people who have been cured had lethal malignancies that were unresponsive to conventional therapy and had the extreme measure of an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not a walk in the park. It has a mortality of 10%-25%, which is completely unacceptable” when “patients feel great on one pill a day” for HIV remission and pretty much have a normal life span.

The transplant reactivated both cytomegalovirus and Epstein Barr virus in the London patient, and he developed graft-versus-host colitis. He survived all three complications.

The take-home message is that “these cases are inspirational. The work ahead is to find out how to deliver the same results with less-extreme measures,” Dr. Mellors said.

The donors for both the London and Berlin patients were homozygous for a delta 32 deletion in the receptor most commonly used by HIV-1 to enter host cells, CCR5. Cells that carry the mutation don’t express the receptor, preventing infection. The mutation prevalence is about 1% among Europeans.

Of the two failed cases, the person who died of lymphoma had a strain of HIV-1 that used a different receptor – CXCR4 – so it’s doubtful the transplant would have worked even if he had survived his cancer.

The London patient wasn’t what’s called an “elite controller,” one of those rare people who suppress HIV without antiretrovirals. His viral loads bounced right back when we was taken off them prior to transplant.

He’s not interested in an active sex life at the moment, Dr. Gupta said, but he might be soon, so Dr. Gupta plans a discussion with him in the near future. Although the London patient could well be immune to HIV that uses the CCR5 receptor, he might not be immune to CXCR4 virus, and he might still be able to produce infectious CCR5 particles. Time will tell.

There was no industry funding for the work. Dr. Gupta is a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and a speaker for Gilead.

SOURCE: Gupta RK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 29.

SEATTLE – The most important thing to know about the apparent HIV cure widely reported in the press recently is that the treatment was worse than the infection, according to John Mellors, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Pittsburgh.

Dr. Mellors moderated a presentation at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections about what the cure involved.

An HIV-positive man with advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma had an allogeneic bone marrow transplant in 2016 after failing first-line chemotherapy and multiple salvage regimens. His donor was homozygous for a gene mutation that prevents HIV from entering new cells. The transplant took; the man’s hematopoietic system was replaced by one with the anti-HIV mutation; and there’s been no trace of active virus in his system since. He’s been off of antiretrovirals for a year and a half. The cancer hasn’t returned.

He’s been dubbed the “London patient.” He joins the “Berlin patient” as the second person who appears to have been freed of infection following a stem cell transplant with the anti-HIV mutation. The Berlin patient recently identified himself as Timothy Ray Brown; he was in the audience at CROI and was applauded for coming forward and sharing his story.

Mr. Brown received a transplant for acute myeloid leukemia and has been off antiretrovirals now for about a decade with no evidence of viral rebound.

Although it didn’t get much attention at CROI, there was a poster of a similar approach seeming to work in a third patient, also with leukemia. It’s been tried – but failed – in two others: one patient died of their lymphoma and the transplant failed in the other, said lead investigator on the London patient case, Ravindra Gupta, MD, a professor in the division of infection & immunity at University College London.

Dr. Mellors pointed out that “the two people who have been cured had lethal malignancies that were unresponsive to conventional therapy and had the extreme measure of an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. Allogeneic bone marrow transplant is not a walk in the park. It has a mortality of 10%-25%, which is completely unacceptable” when “patients feel great on one pill a day” for HIV remission and pretty much have a normal life span.

The transplant reactivated both cytomegalovirus and Epstein Barr virus in the London patient, and he developed graft-versus-host colitis. He survived all three complications.

The take-home message is that “these cases are inspirational. The work ahead is to find out how to deliver the same results with less-extreme measures,” Dr. Mellors said.

The donors for both the London and Berlin patients were homozygous for a delta 32 deletion in the receptor most commonly used by HIV-1 to enter host cells, CCR5. Cells that carry the mutation don’t express the receptor, preventing infection. The mutation prevalence is about 1% among Europeans.

Of the two failed cases, the person who died of lymphoma had a strain of HIV-1 that used a different receptor – CXCR4 – so it’s doubtful the transplant would have worked even if he had survived his cancer.

The London patient wasn’t what’s called an “elite controller,” one of those rare people who suppress HIV without antiretrovirals. His viral loads bounced right back when we was taken off them prior to transplant.

He’s not interested in an active sex life at the moment, Dr. Gupta said, but he might be soon, so Dr. Gupta plans a discussion with him in the near future. Although the London patient could well be immune to HIV that uses the CCR5 receptor, he might not be immune to CXCR4 virus, and he might still be able to produce infectious CCR5 particles. Time will tell.

There was no industry funding for the work. Dr. Gupta is a consultant for ViiV Healthcare and a speaker for Gilead.

SOURCE: Gupta RK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 29.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

New cantharidin formulation alleviates molluscum contagiosum in pivotal trials

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

WASHINGTON – compared with placebo, according to the results of two trials presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

VP-102, a drug-device combination, was well tolerated and was not associated with serious adverse events.

No Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment is available for treating molluscum contagiosum, which is routinely treated with cantharidin, a naturally occurring vesicant.

VP-102 is a novel formulation of 0.7% cantharidin solution, provided in a single-use applicator, to provide consistent delivery and long-term drug stability.

To test the efficacy and safety of VP-102, Lawrence Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego, and his associates conducted the CAMP-1 (Cantharidin Application in Molluscum Patients) and CAMP-2 phase 3 studies, which had similar designs. The studies enrolled patients with molluscum contagiosum aged 2 years and older who had not received any treatment in the 2 weeks before enrollment. Patients were randomized to VP-102 or vehicle for 12 weeks. Treatment was administered topically to each lesion every 3 weeks for a maximum of four applications, and washed off with soap and warm water 24 hours after application.

The trials’ primary endpoint was the percentage of patients with complete clearance of their lesions. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with complete clearance at 3, 6, and 9 weeks, and decrease in lesions over time. The researchers also assessed safety and tolerability.

In the two studies, 528 patients aged 2-60 years (mean age, approximately 7 years) were randomized to treatment or vehicle. About 30% of participants had prior treatment. The baseline lesion count ranged from 1 to 184.

At day 84, the proportion of patients in the VP-102 arm who achieved complete clearance of lesions was 46% in CAMP-1 and 54% in CAMP-2, compared with 18% and 13%, respectively, among controls (P less than .0001). By day 84, among treated patients, the lesion count had decreased by a mean of 69% in CAMP-1 and 83% in CAMP-2, compared with 20% and 19%, respectively, among controls. Results among controls were “probably consistent with natural history,” Dr. Eichenfield observed.

The researchers observed a high incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events among patients receiving VP-102. “Any crust or vesiculation was considered to be a treatment-emergent adverse event,” Dr. Eichenfield said. Most adverse events were mild, although five patients discontinued the studies because of treatment-emergent adverse events. Vesiculation was a common adverse event in the VP-102 group; pruritus and application-site pain were reported as well.

Verrica Pharmaceuticals developed VP-102 and funded the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica, which plans to submit for FDA approval in the second half of 2019.

SOURCE: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

REPORTING FROM AAD 2019

Key clinical point: VP-102 is an effective treatment for molluscum contagiosum.

Major finding: In two studies, 46% and 54% of actively treated patients had complete resolution, compared with 13% and 18% of controls, respectively.

Study details: Two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of 528 patients with molluscum contagiosum.

Disclosures: Verrica Pharmaceuticals sponsored the study. Dr. Eichenfield reported receiving no funding from the company; several other investigators are employees of Verrica Pharmaceuticals.Source: Eichenfield L et al. AAD 19, Abstract 11251.

Hospital-onset sepsis twice as lethal as community-onset disease

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

SAN DIEGO – Patients who develop sepsis in the hospital appear to be in greater risk for mortality than those who bring it with them, a new study suggests. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis were twice as likely to die as those infected in the outside world.

“There could be some differences in quality of care that explains the difference in mortality,” said study lead author Chanu Rhee, MD, assistant professor of population medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, in a presentation about the findings at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

In an interview, Dr. Rhee said researchers launched the study to gain a greater understanding of the epidemiology of sepsis in the hospital. They relied on a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of sepsis that is “enhancing the consistency of surveillance across hospitals and allowing more precise differentiation between hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis.”

The study authors retrospectively tracked more than 2.2 million patients who were treated at 136 U.S. hospitals from 2009 to 2015. In general, hospital-onset sepsis was defined as patients who had a blood culture, initial antibiotic therapy, and organ dysfunction on their third day in the hospital or later.*

Of the patients, 83,600 had community-onset sepsis and 11,500 had hospital-onset sepsis. Those with sepsis were more likely to be men and have comorbidities such as cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and renal disease.

Patients with hospital-onset sepsis had longer median lengths of stay (19 days) than the community-onset group (8 days) and the no-sepsis group (4 days). The hospital-onset group also had a greater likelihood of ICU admission (61%) than the community-onset (44%) and no-sepsis (9%) groups.

About 34% of those with hospital-onset sepsis died, compared with 17% of the community-onset group and 2% of the patients who didn’t have sepsis. After adjustment, those with hospital-onset sepsis were still more likely to have died (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-2.2).

“Other studies have suggested that there may be delays in the recognition and care of patients who develop sepsis in the hospital as opposed to presenting to the hospital with sepsis,” Dr. Rhee said. “It is also possible that hospital-onset sepsis tends to be caused by organisms that are more virulent and resistant to antibiotics.”

Overall, he said, “our findings underscore the importance of targeting hospital-onset sepsis with surveillance, prevention, and quality improvement efforts.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Rhee C et al. CCC48, Abstract 29.

*Correction, 3/19/19: An earlier version of this article misstated the definition of sepsis.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

ICYMI: Noninferior tuberculosis prevention in HIV has shorter duration

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Descovy noninferior to Truvada for PrEP

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Opioid overdose risk greater among HIV patients

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

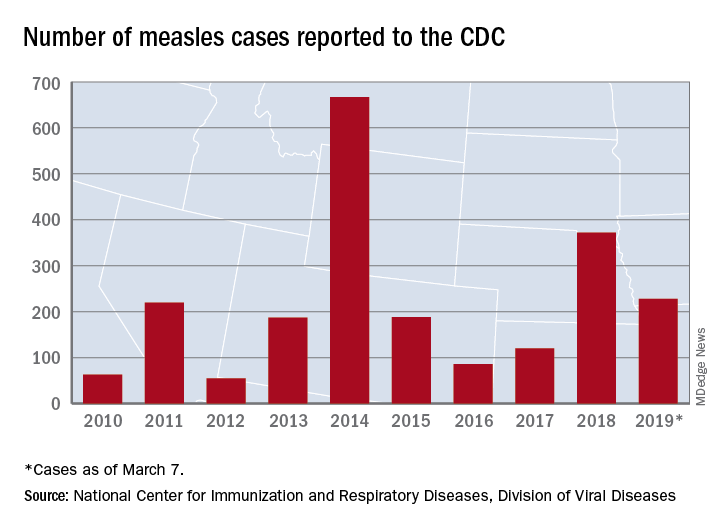

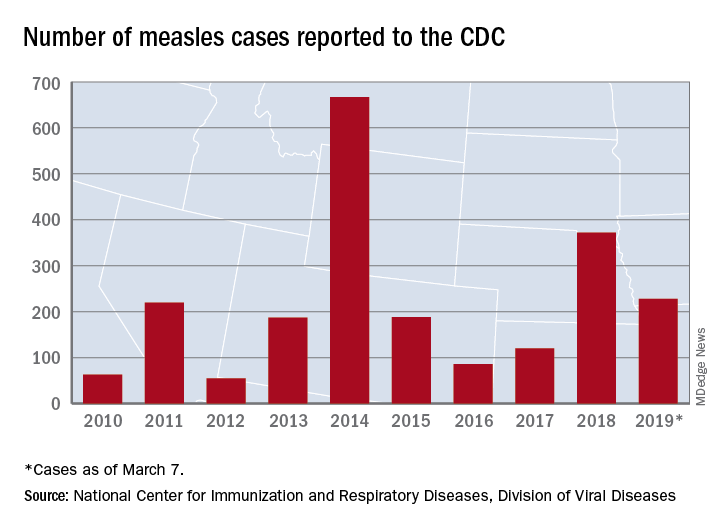

Measles now confirmed in 12 states

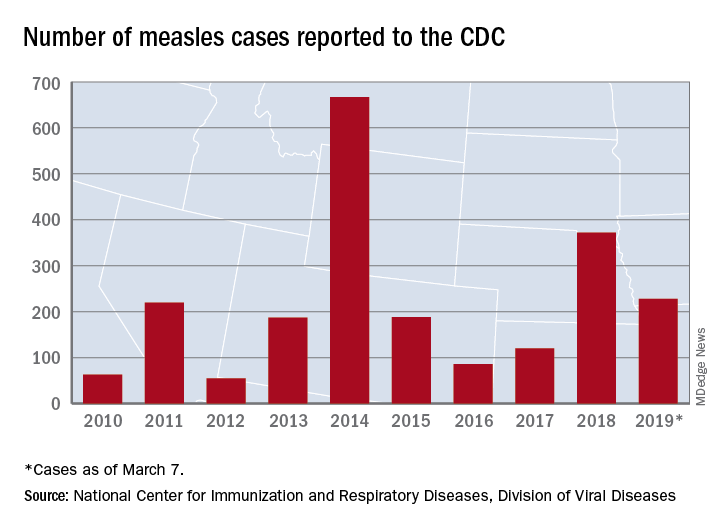

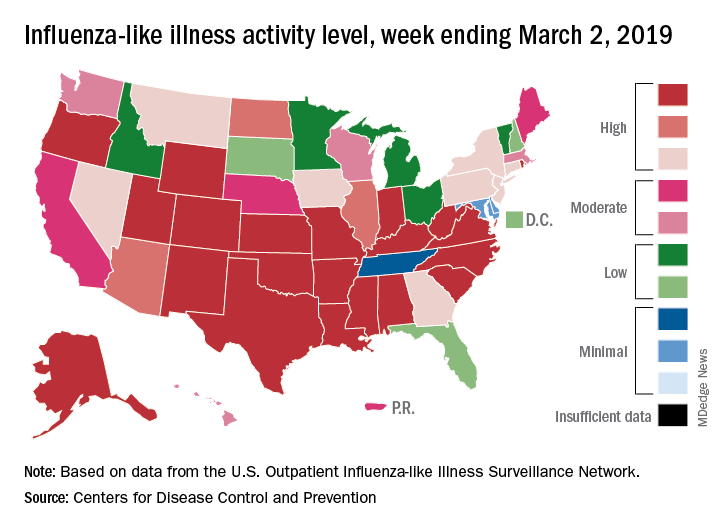

The number of new measles cases was down by more than half last week, but another state has been added to the list of those with reported cases in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total for the year is 228 cases, which moves 2019 ahead of 2011 for third place over the last decade, the CDC reported March 11. Going back even further in time, the 206 measles cases reported through January and February is the highest 2-month total in a quarter of a century, the Washington Post said.

New Hampshire became the 12th and latest state to report a case of measles this year, joining California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. California’s situation is now considered an outbreak (defined as three or more cases), but one of the three outbreaks in New York has been taken off the list, so total outbreaks for 2019 remain at six, the CDC said.

For the third consecutive week, New York City produced the most measles cases, with Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood recording 11 of the U.S. total of 21. The outbreak in King County, Wash., – totaling 70 cases this year – may be winding down as only one new case was reported last week, and no new cases are being investigated, the county’s public health service reported.

The number of new measles cases was down by more than half last week, but another state has been added to the list of those with reported cases in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total for the year is 228 cases, which moves 2019 ahead of 2011 for third place over the last decade, the CDC reported March 11. Going back even further in time, the 206 measles cases reported through January and February is the highest 2-month total in a quarter of a century, the Washington Post said.

New Hampshire became the 12th and latest state to report a case of measles this year, joining California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. California’s situation is now considered an outbreak (defined as three or more cases), but one of the three outbreaks in New York has been taken off the list, so total outbreaks for 2019 remain at six, the CDC said.

For the third consecutive week, New York City produced the most measles cases, with Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood recording 11 of the U.S. total of 21. The outbreak in King County, Wash., – totaling 70 cases this year – may be winding down as only one new case was reported last week, and no new cases are being investigated, the county’s public health service reported.

The number of new measles cases was down by more than half last week, but another state has been added to the list of those with reported cases in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The total for the year is 228 cases, which moves 2019 ahead of 2011 for third place over the last decade, the CDC reported March 11. Going back even further in time, the 206 measles cases reported through January and February is the highest 2-month total in a quarter of a century, the Washington Post said.

New Hampshire became the 12th and latest state to report a case of measles this year, joining California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. California’s situation is now considered an outbreak (defined as three or more cases), but one of the three outbreaks in New York has been taken off the list, so total outbreaks for 2019 remain at six, the CDC said.

For the third consecutive week, New York City produced the most measles cases, with Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood recording 11 of the U.S. total of 21. The outbreak in King County, Wash., – totaling 70 cases this year – may be winding down as only one new case was reported last week, and no new cases are being investigated, the county’s public health service reported.

To avoid Hep B reactivation, screen before immunosuppression

CASE A 53-year-old woman you are seeing for the first time has been taking 10 mg of prednisone daily for a month, prescribed by another practitioner for polymyalgia rheumatica. Testing is negative for hepatitis B surface antigen but is positive for hepatitis B core antibody total, indicating a resolved hepatitis B infection. The absence of hepatitis B DNA is confirmed.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Patients with resolved hepatitis B virus (HBV) or chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infections are at risk for HBV reactivation (HBVr) if they undergo immunosuppressive therapy for a condition such as cancer. HBVr can in turn lead to delays in treatment and increased morbidity and mortality.

HBVr is a well-documented adverse outcome in patients treated with rituximab and in those undergoing stem cell transplantation. Current oncology guidelines recommend screening for HBV prior to initiating these treatments.1,2 More recent evidence shows that many other immunosuppressive therapies can also lead to HBVr.3 Such treatments are now used across a multitude of specialties and conditions. For many of these conditions, there are no consistent guidelines regarding HBV screening.

In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced the requirement of a Boxed Warning for the immunosuppressive drugs ofatumumab and rituximab. In 2016, the FDA announced the same requirement for certain direct-acting antiviral medicines for hepatitis C virus.

Among patients who are positive for hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBsAg) and who are treated with immunosuppression, the frequency of HBVr has ranged from 0% to 39%.4,5

As the list of immunosuppressive therapies that can cause HBVr grows, specialty guidelines are evolving to address the risk that HBVr poses.

Continue to: An underrecognized problem

An underrecognized problem. CHB affects an estimated 350 million people worldwide6 but remains underrecognized and underdiagnosed. An estimated 1.4 million Americans6 have CHB, but only a minority of them are aware of their positive status and are followed by a hepatologist or receive medical care for their disease.7 Compared with the natural-born US population, a higher prevalence of CHB exists among immigrants to this country from the Asian Pacific and Eastern Mediterranean regions, sub-Saharan Africa, and certain parts of South America.8-10 In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its recommendations on screening for HBV to include immigrants to the United States from intermediate and high endemic areas.6 Unfortunately, data published on physicians’ adherence to the CDC guidelines for screening show that only 60% correctly screened at-risk patients.11

Individuals with CHB are at risk and rely on a robust immune system to keep their disease from becoming active. During infection, the virus gains entry into the hepatocytes and the double-stranded viral genome is imported into the nucleus of the cell, where it is repaired into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Research has demonstrated the stability of cccDNA and its persistence as a latent reservoir for HBV reactivation, even decades after recovery from infection.12

Also at risk are individuals who have unrecovered from HBV infection and are HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive. To avert reverse seroconversion, they also rely on a robust immune system.13 Reverse seroconversion is defined as a reappearance of HBV DNA and HBsAg positivity in individuals who were previously negative.13 In these individuals, HBV DNA may not be quantifiable in circulation, but trace amounts of viral DNA found in the liver are enough to pose a reactivation risk in the setting of immune suppression.14

Moreover, often overlooked is the fact that reactivation or reverse seroconversion can necessitate disruptions and delays in immunosuppressive treatment for other life-threatening disease processes.14,15

Universal screening reduces risk for HBVr. Patients with CHB are at risk for reactivation, as are patients with resolved HBV infection. Many patients, however, do not know their status. By screening all patients before beginning immunosuppressive therapy, physicians can provide effective prophylaxis, which has been shown to significantly reduce the risk for HBVr.8.15

Continue to: Recognizing the onset of HBVr

Recognizing the onset of HBVr

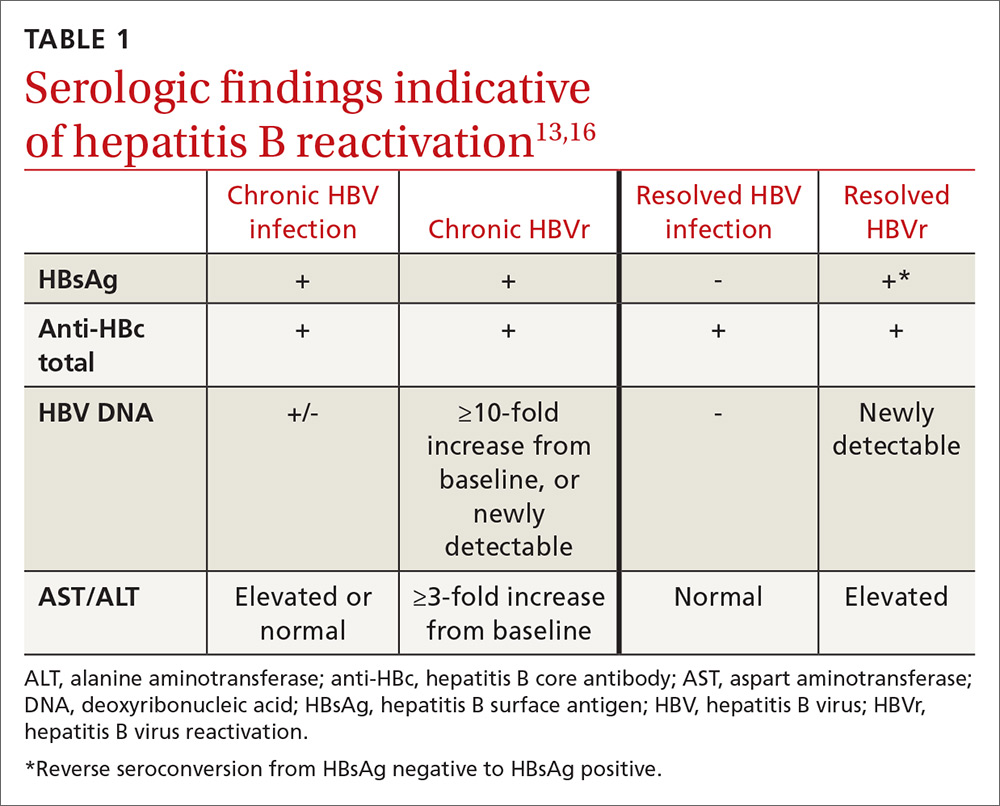

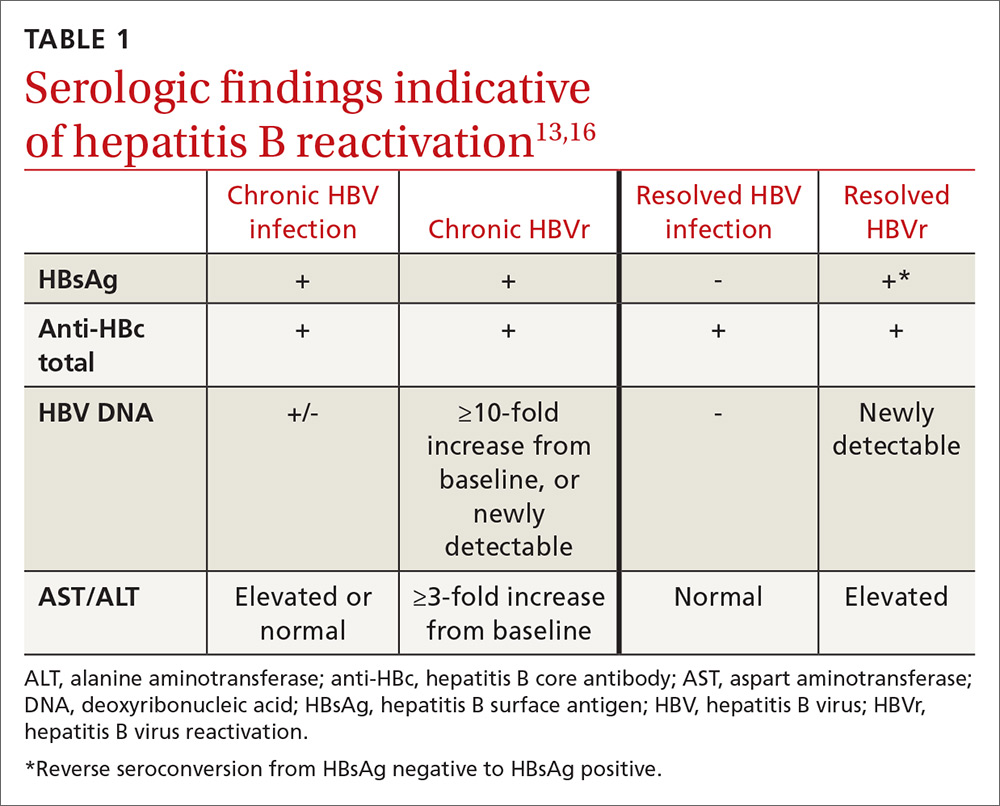

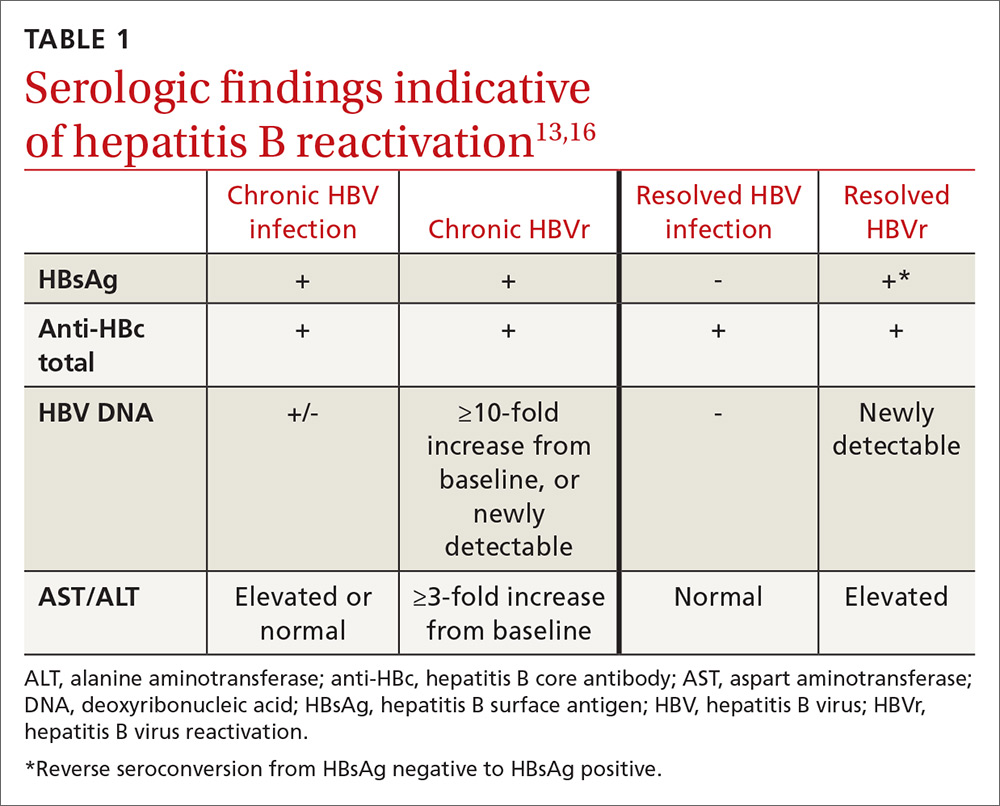

In patients with CHB, HBVr is defined as at least a 3-fold increase in aspart aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and at least a 10-fold increase from baseline in HBV DNA. In patients with resolved HBV infection, there may be reverse seroconversion from HbsAg-negative to HBsAg-positive status (TABLE 113,16).

Not all elevations in AST/ALT in patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy indicate HBVr. Very often, derangements in AST/ALT may be related to the toxic effects of therapy or to the underlying disease process. However, as immunosuppressive therapy is now used for a wide array of medical conditions, consider HBVr as a potential cause of abnormal liver function in all patients receiving such therapy

A patient is at risk for HBVr when starting immunosuppression and up to a year following the completion of therapy. With suppression of the immune system, HBV replication increases and serum AST/ALT concentrations may rise. HBVr may also present with the appearance of HBV DNA in patients with previously undetectable levels.12,17

Most patients remain asymptomatic, and abnormal AST/ALT levels eventually resolve after completion of immunosuppression. However, some patients' liver enzymes may rise, indicating a more severe hepatic flare. These patients may present with right upper-quadrant tenderness, jaundice, or fatigue. In these cases, recognizing HBVr and starting antivirals may reduce hepatitis flare.

Unfortunately, despite early recognition of HBVr and initiation of appropriate therapy, some patients can progress to hepatic decompensation and even fulminant hepatic failure that may have been prevented with prophylaxis.

Continue to: The justification for universal screening

The justification for universal screening

Although nongastroenterology societies differ in their recommendations on screening for HBV, universal screening before implementing prolonged immunosuppressive treatment is recommended by the CDC,6 the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases,18 the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver,19 the European Association for the Study of the Liver,20 and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA).21

Older guidelines recommended screening only high-risk populations. But such screening has downfalls. It requires that patients or their physicians recognize that they are at high risk. In one study, nearly 65% of an infected Asian-American population was unaware of their positive HBV status.22 Risk-based screening also requires that physicians ask the appropriate questions and that patients admit to high-risk behavior. Screening patients based only on risk factors may easily overlook patients who need prophylaxis against HBVr.

Common arguments against universal screening include the cost of testing, the possibility of false-positive results, and the implications of a new diagnosis of hepatitis B. However, the potential benefits of screening are significant, and HBV screening in the general population has been shown to be cost effective when the prevalence of HBV is 0.3%.21 In the United States, conservative estimates are a prevalence of HBsAg positivity of 0.4% and past infection of 3%, making screening a cost-effective recommendation.16 It is therefore prudent to screen all patients before starting immunosuppressive therapy.

How to screen

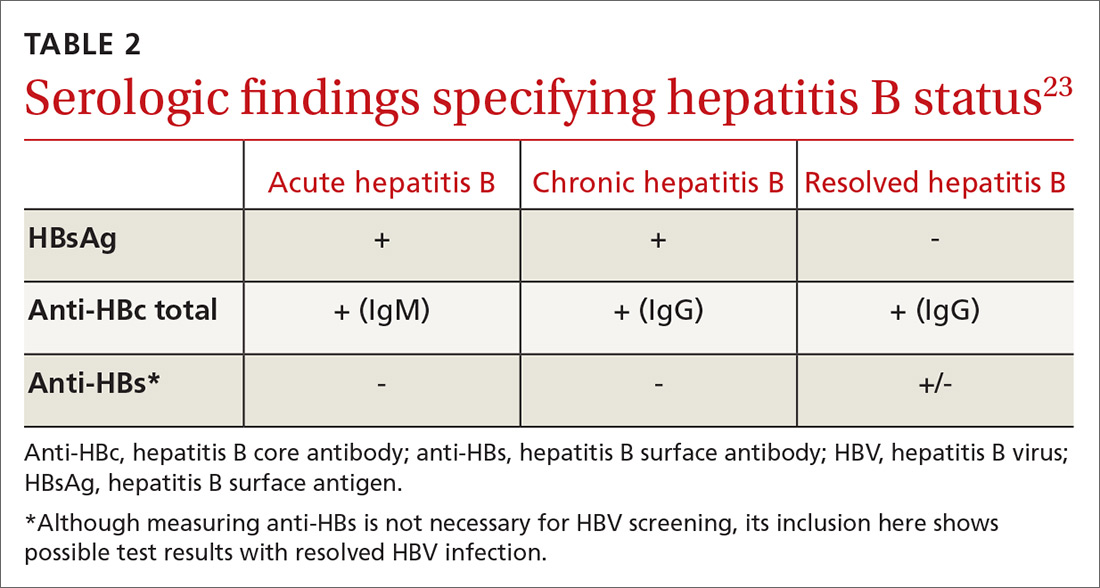

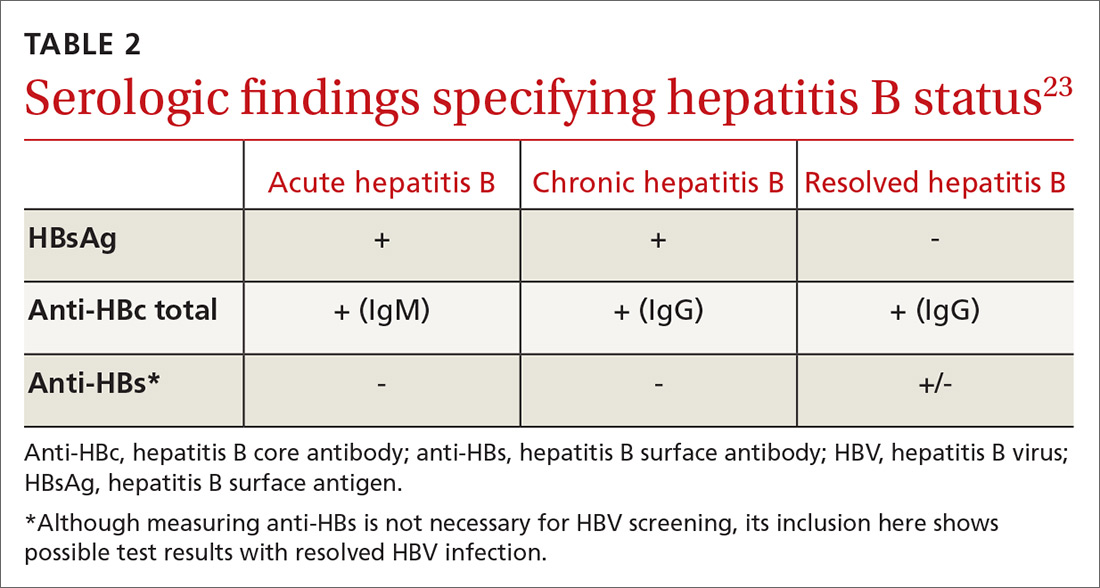

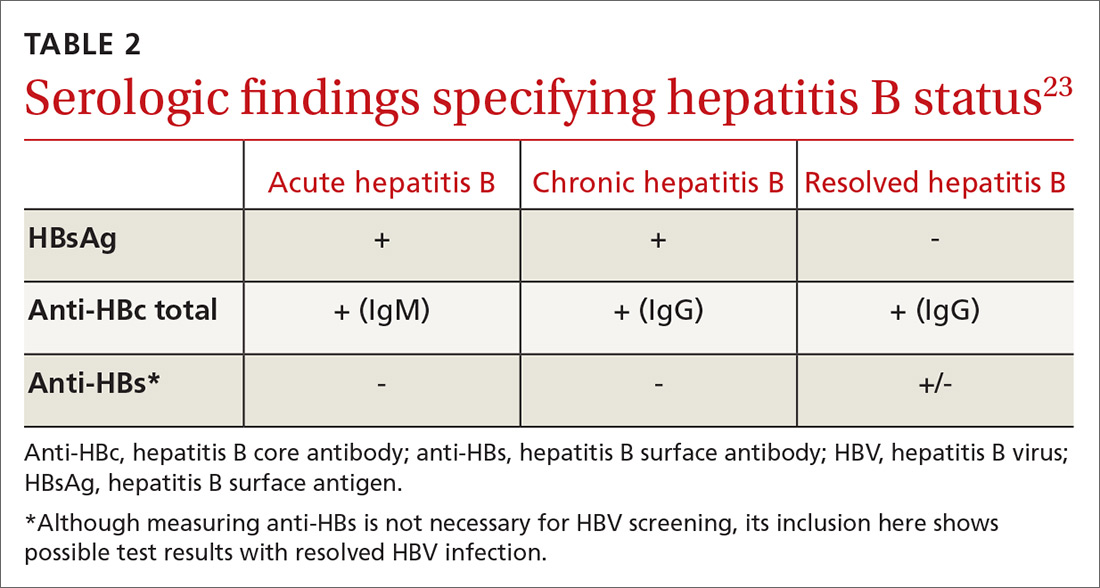

All guidelines agree on how to test for HBV. Measuring levels of HBsAg and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc total) allows the clinician to ascertain whether the patient’s HBV infection status is acute, chronic, or resolved (TABLE 223) and to perform HBVr risk stratification (discussed later).

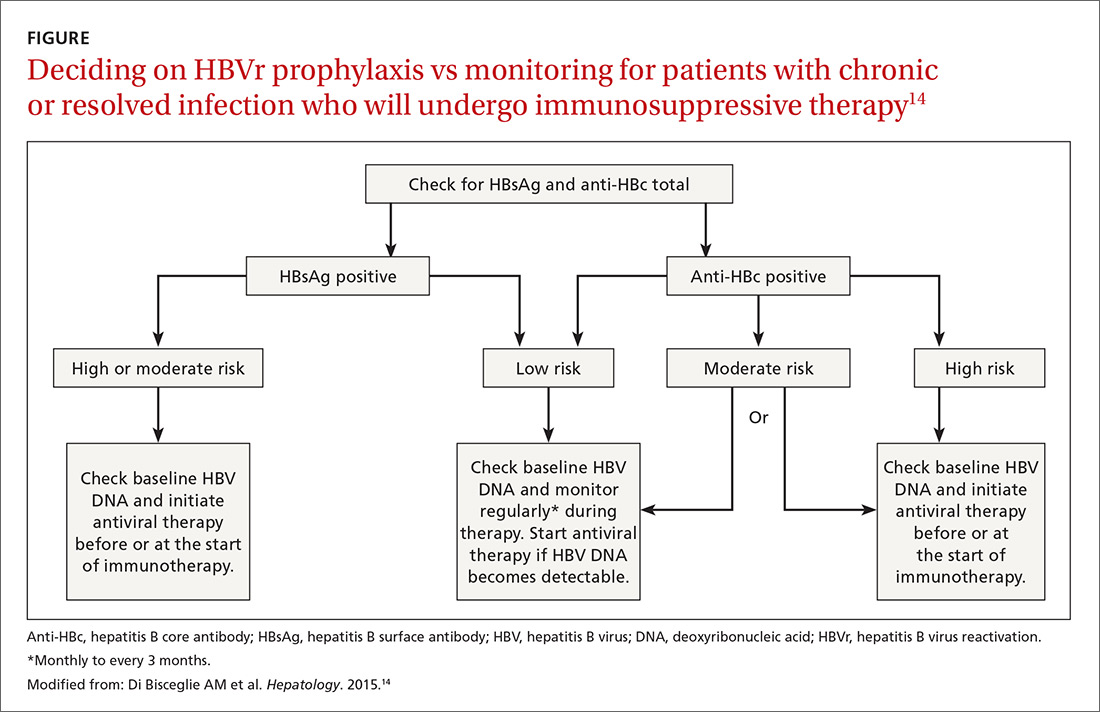

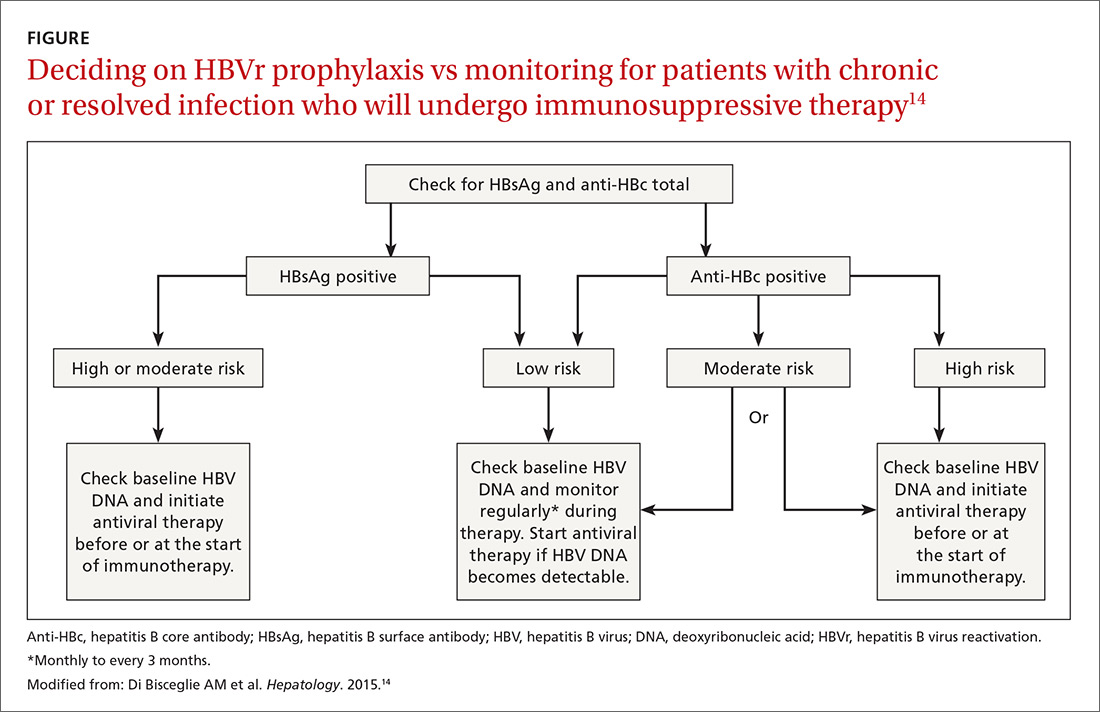

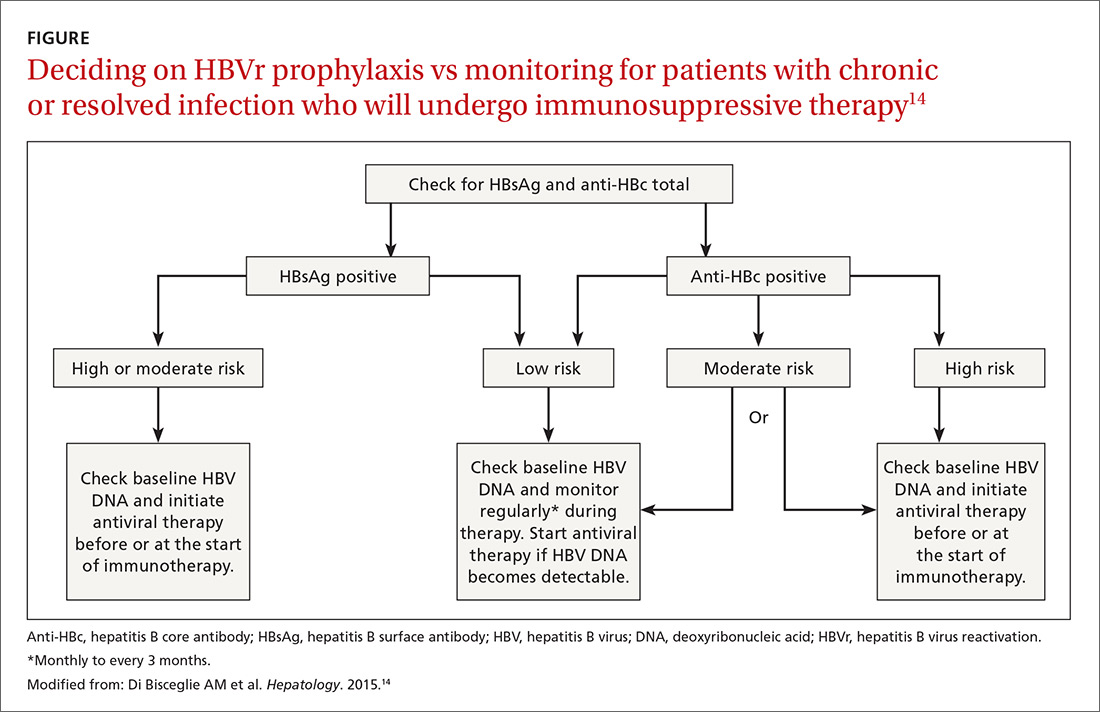

Patients with acute infections should be referred to a hepatologist. With chronic or resolved HBV, stratify patients into a prophylaxis group or monitoring group (FIGURE14). Stratification involves identifying HBV status (chronic or resolved) and selecting a type of immunosuppressive therapy. Whether the patient falls into prophylaxis or monitoring, obtain a baseline level of viral DNA, as this has proven to be the best predictor of HBV reactivation.16

Continue to: In screening, be sure the appropriate...

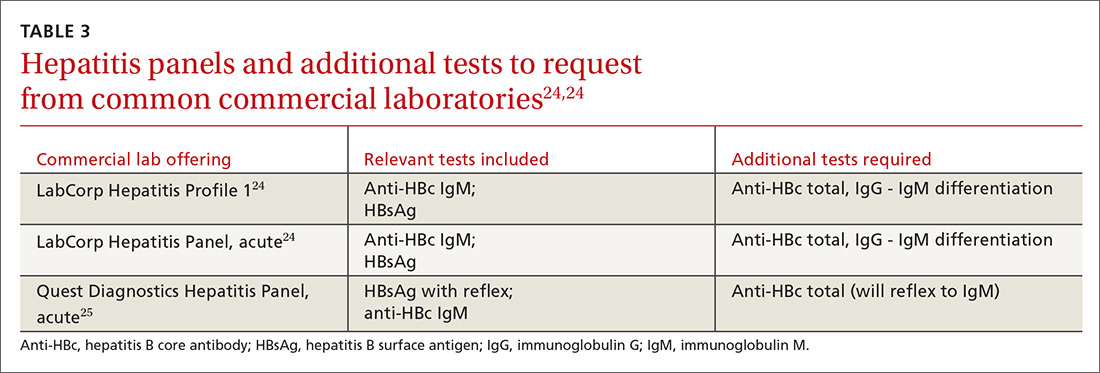

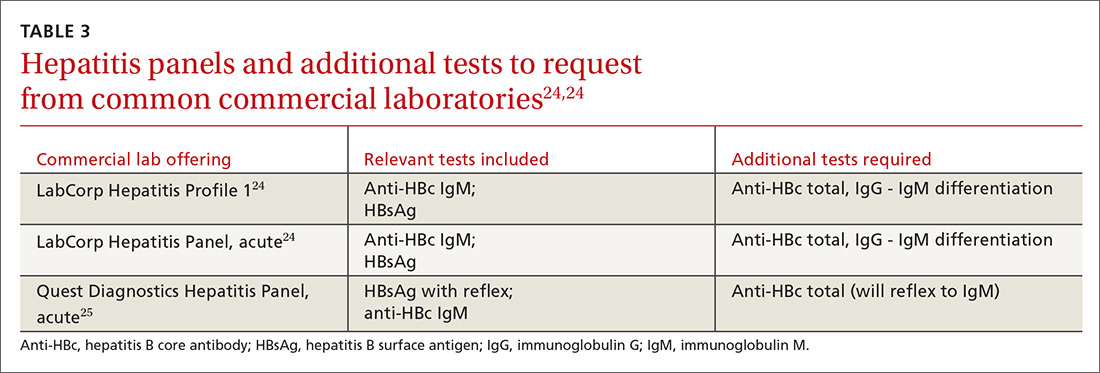

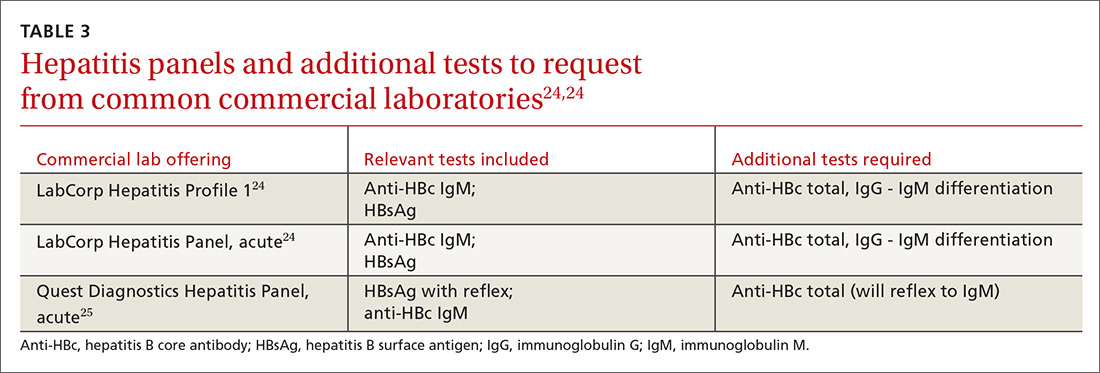

In screening, be sure the appropriate anti-HBc testing is covered. Common usage of the term anti-HBc may refer to immunoglobulin G (IgG) or immunoglobulin M (IgM)or total core antibody, containing both IgG and IgM. But in this context, accurate screening requires either total core antibody or anti-HBc IgG. Anti-IgM alone is inadequate. Many commercial laboratories offer acute hepatitis panels or hepatitis profiles (TABLE 324,25), and it is important to confirm that such order sets contain the tests necessary to allow for risk stratification.

Testing for hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) is not useful in screening. Although it was hypothesized that the presence of this antibody lowered risk, recent studies have proven no change in risk based on this value.21

How to assess HBVr risk

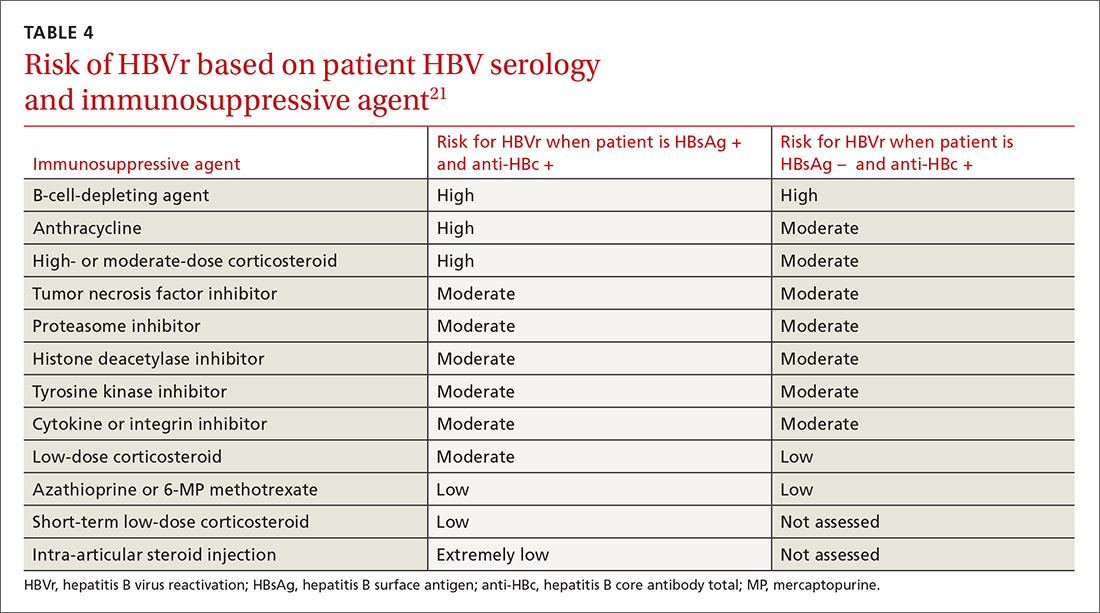

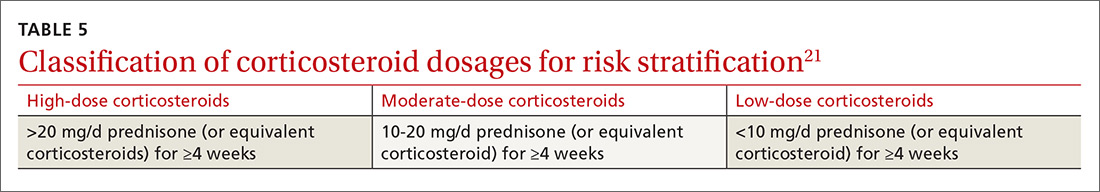

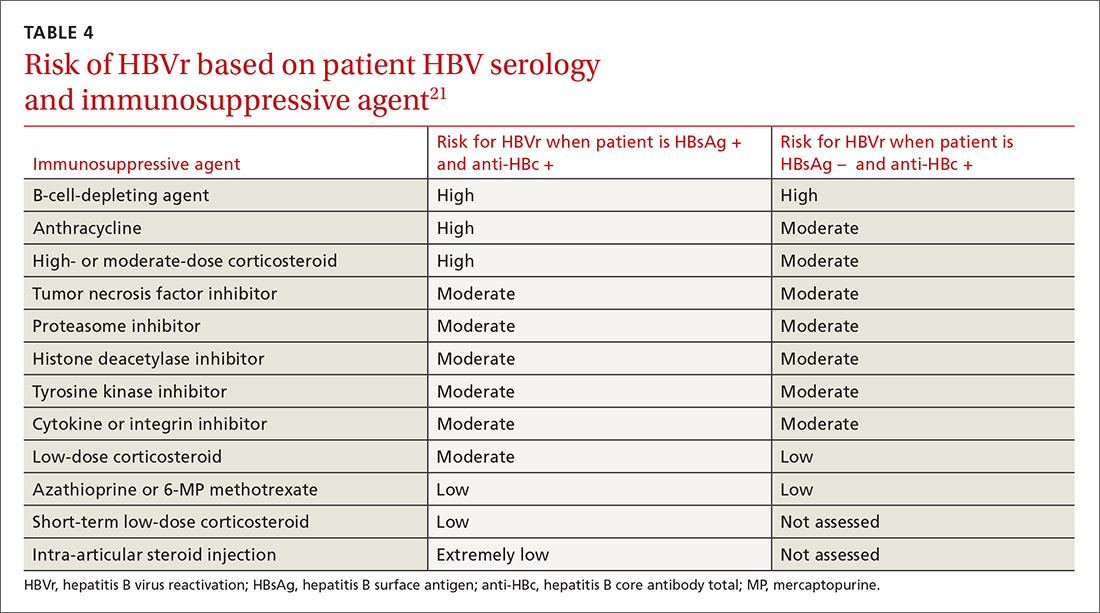

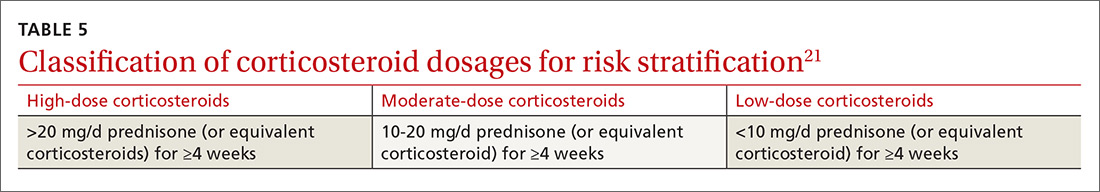

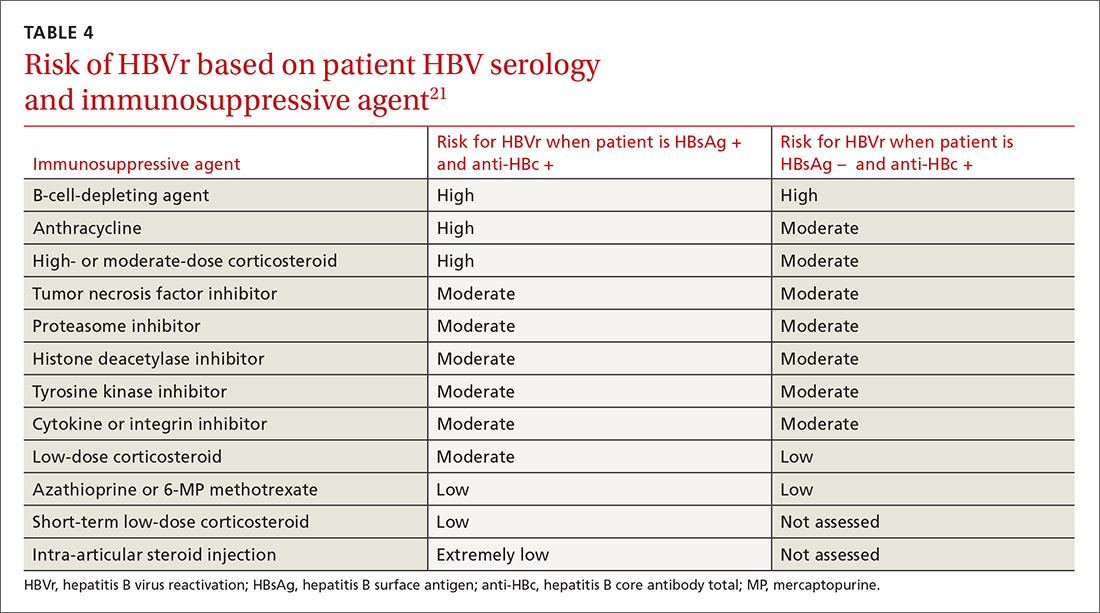

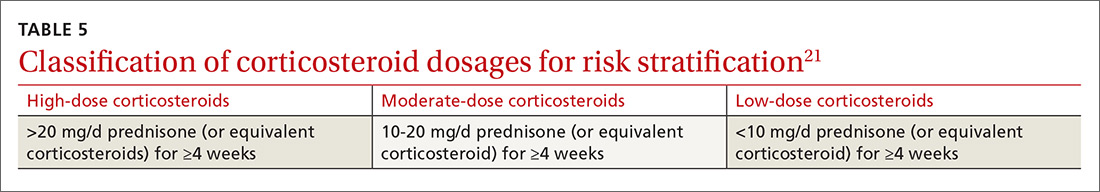

Assessing risk for HBVr takes into account both the patient’s serology and intended treatment. Reddy et al delineated patient groups into high, moderate, and low risk (TABLES 4 and 5).21 The high-risk group was defined by anticipated incidence of HBVr in > 10% of cases; the moderate-risk group had an anticipated incidence of 1% to 10%; and the low-risk group had an anticipated incidence of <1%.21 Evidence was strongest in the high-risk group.

Patients with CHB (HBsAg positive and anti-HBc positive) are considered high risk for reactivation with a wide variety of immunosuppressive therapies. Such patients are 5 to 8 times more likely to develop HBVr than patients with an HBsAg-negative status signifying a resolved infection.16