User login

Developing an HCV vaccine faces significant challenges

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Possible biomarkers found for progression to liver cancer in chronic HCV infection

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

FROM VIROLOGY

Take stronger steps to prevent staph infections and sepsis

according to data from a Vital Signs report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data include both methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

Although MRSA infections in health care settings declined by approximately 17% during 2005-2012, rates plateaued during 2012-2017, Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference March 5 to present the findings. The report emphasizes the potential for serious illness and death with any staph infection and the need for ongoing vigilance on the part of clinicians, she said.

In addition, community-onset MSSA infections increased by 3.9%/year during 2012-2017. Data from previous studies suggest that this increase may be connected to the opioid epidemic, said Dr. Schuchat.

“People who inject drugs are 16% more likely to develop a staph infection” than are those who don’t inject drugs, she said.

Community-onset MRSA declined by 6.9% during 2001-2016, attributed to declines in health care–associated infections, according to Vital Signs author Athena P. Kourtis, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues. Rates of hospital-associated MSSA infection remained essentially unchanged (P = .11). The overall unadjusted in-hospital mortality among patients with S. aureus bloodstream infections over the study period was 18%.

The data for the report were collected from electronic health records at more than 400 acute care hospitals, as well as population-based surveillance data from the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Most people carry staph on their skin with no ill effects, but the bacteria become dangerous when they enter the bloodstream, Dr. Schuchat emphasized. “We hope the new data today will refocus the nation’s efforts to protect patients from staph infections,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat advised clinicians and hospital administrators to review their data and step up their safety protocols to prevent staph infections. Precautions include wearing gowns and gloves, following proper hand washing protocols, cautious use of antibiotics, and treating infections rapidly when they occur, she said. Dr. Schuchat noted that lack of adherence to these recommendations may have declined in recent years if clinicians and hospital administrators were wondering whether their protocols have an effect and have value. However, “this is a very serious infection, and we think it is very much worth preventing,” she emphasized.

Other strategies to prevent staph infections in health care settings include reviewing infection data regularly, exploring new approaches to prevent infections, and educating patients about when they may be at increased risk for infection, such as when invasive devices are in place or during surgical procedures. Also, clinicians should be aware of the increased risk for patients who inject drugs, Dr. Schuchat said.

Dr. Schuchat commended the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMC), which overall reduced their rate of staph infections by 43% during the period from 2005 through 2017 in contrast to the national trend. These findings also appeared in the MMWR on March 5. The VAMC implemented additional interventions and increased their adherence to CDC recommendations during this period, she noted.

The Vital Signs data were published March 5 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; read the full report here.

The CDC researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kourtis AP et al. MMWR. 2019 Mar 5; 68:1-6.

according to data from a Vital Signs report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data include both methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

Although MRSA infections in health care settings declined by approximately 17% during 2005-2012, rates plateaued during 2012-2017, Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference March 5 to present the findings. The report emphasizes the potential for serious illness and death with any staph infection and the need for ongoing vigilance on the part of clinicians, she said.

In addition, community-onset MSSA infections increased by 3.9%/year during 2012-2017. Data from previous studies suggest that this increase may be connected to the opioid epidemic, said Dr. Schuchat.

“People who inject drugs are 16% more likely to develop a staph infection” than are those who don’t inject drugs, she said.

Community-onset MRSA declined by 6.9% during 2001-2016, attributed to declines in health care–associated infections, according to Vital Signs author Athena P. Kourtis, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues. Rates of hospital-associated MSSA infection remained essentially unchanged (P = .11). The overall unadjusted in-hospital mortality among patients with S. aureus bloodstream infections over the study period was 18%.

The data for the report were collected from electronic health records at more than 400 acute care hospitals, as well as population-based surveillance data from the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Most people carry staph on their skin with no ill effects, but the bacteria become dangerous when they enter the bloodstream, Dr. Schuchat emphasized. “We hope the new data today will refocus the nation’s efforts to protect patients from staph infections,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat advised clinicians and hospital administrators to review their data and step up their safety protocols to prevent staph infections. Precautions include wearing gowns and gloves, following proper hand washing protocols, cautious use of antibiotics, and treating infections rapidly when they occur, she said. Dr. Schuchat noted that lack of adherence to these recommendations may have declined in recent years if clinicians and hospital administrators were wondering whether their protocols have an effect and have value. However, “this is a very serious infection, and we think it is very much worth preventing,” she emphasized.

Other strategies to prevent staph infections in health care settings include reviewing infection data regularly, exploring new approaches to prevent infections, and educating patients about when they may be at increased risk for infection, such as when invasive devices are in place or during surgical procedures. Also, clinicians should be aware of the increased risk for patients who inject drugs, Dr. Schuchat said.

Dr. Schuchat commended the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMC), which overall reduced their rate of staph infections by 43% during the period from 2005 through 2017 in contrast to the national trend. These findings also appeared in the MMWR on March 5. The VAMC implemented additional interventions and increased their adherence to CDC recommendations during this period, she noted.

The Vital Signs data were published March 5 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; read the full report here.

The CDC researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kourtis AP et al. MMWR. 2019 Mar 5; 68:1-6.

according to data from a Vital Signs report issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data include both methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

Although MRSA infections in health care settings declined by approximately 17% during 2005-2012, rates plateaued during 2012-2017, Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, said in a teleconference March 5 to present the findings. The report emphasizes the potential for serious illness and death with any staph infection and the need for ongoing vigilance on the part of clinicians, she said.

In addition, community-onset MSSA infections increased by 3.9%/year during 2012-2017. Data from previous studies suggest that this increase may be connected to the opioid epidemic, said Dr. Schuchat.

“People who inject drugs are 16% more likely to develop a staph infection” than are those who don’t inject drugs, she said.

Community-onset MRSA declined by 6.9% during 2001-2016, attributed to declines in health care–associated infections, according to Vital Signs author Athena P. Kourtis, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, and her colleagues. Rates of hospital-associated MSSA infection remained essentially unchanged (P = .11). The overall unadjusted in-hospital mortality among patients with S. aureus bloodstream infections over the study period was 18%.

The data for the report were collected from electronic health records at more than 400 acute care hospitals, as well as population-based surveillance data from the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program.

Most people carry staph on their skin with no ill effects, but the bacteria become dangerous when they enter the bloodstream, Dr. Schuchat emphasized. “We hope the new data today will refocus the nation’s efforts to protect patients from staph infections,” she said.

Dr. Schuchat advised clinicians and hospital administrators to review their data and step up their safety protocols to prevent staph infections. Precautions include wearing gowns and gloves, following proper hand washing protocols, cautious use of antibiotics, and treating infections rapidly when they occur, she said. Dr. Schuchat noted that lack of adherence to these recommendations may have declined in recent years if clinicians and hospital administrators were wondering whether their protocols have an effect and have value. However, “this is a very serious infection, and we think it is very much worth preventing,” she emphasized.

Other strategies to prevent staph infections in health care settings include reviewing infection data regularly, exploring new approaches to prevent infections, and educating patients about when they may be at increased risk for infection, such as when invasive devices are in place or during surgical procedures. Also, clinicians should be aware of the increased risk for patients who inject drugs, Dr. Schuchat said.

Dr. Schuchat commended the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMC), which overall reduced their rate of staph infections by 43% during the period from 2005 through 2017 in contrast to the national trend. These findings also appeared in the MMWR on March 5. The VAMC implemented additional interventions and increased their adherence to CDC recommendations during this period, she noted.

The Vital Signs data were published March 5 in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; read the full report here.

The CDC researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kourtis AP et al. MMWR. 2019 Mar 5; 68:1-6.

FROM THE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Don’t overlook this step in combatting the rise in STIs

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Resources

1. Kuehn BM. A proactive approach needed to combat rising STIs. JAMA. 2019;321:330-332.

2. Screening Recommendations and Considerations Referenced in Treatment Guidelines and Original Sources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/screening-recommendations.htm. Updated June 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2019.

3. STD Clinical Consultation Network. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/page/site/clinical-consultation. Accessed February 27, 2019.

4. National STD Curriculum. https://www.std.uw.edu/. Accessed February 27, 2019.

5. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Syphilis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/syphilis.htm. Reviewed July 24, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2019.

Measles cases jumped 30% last week

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those new cases represent a 30% increase in measles cases for the year, bringing the total to 206 reported to the CDC through Feb. 28. After just 2 months, 2019 has had more cases than all but 3 other years over the last decade, CDC data show.

The 11th state to report a case of measles this year is New Jersey, which joins California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois (one outbreak), Kentucky, New York (three outbreaks), Oregon, Texas (one outbreak), and Washington (one outbreak), the CDC said.

The outbreak in Washington (4 new cases/70 for the year) had been the largest, but the majority of the new cases over the last 2 weeks have occurred in New York City, specifically Brooklyn, which reported 30 cases last week and 17 of the 32 new U.S. cases the week before.

Most of the 120 cases reported in the borough since the beginning of its outbreak in October of 2018 “have involved members of the Jewish Orthodox community. The initial child with measles was unvaccinated and acquired measles on a visit to Israel, where a large outbreak of the disease is occurring. Since then, there have been additional people from Brooklyn and Queens who were unvaccinated and acquired measles while in Israel. People who did not travel were also infected in Brooklyn or Rockland County,” the CDC said.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those new cases represent a 30% increase in measles cases for the year, bringing the total to 206 reported to the CDC through Feb. 28. After just 2 months, 2019 has had more cases than all but 3 other years over the last decade, CDC data show.

The 11th state to report a case of measles this year is New Jersey, which joins California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois (one outbreak), Kentucky, New York (three outbreaks), Oregon, Texas (one outbreak), and Washington (one outbreak), the CDC said.

The outbreak in Washington (4 new cases/70 for the year) had been the largest, but the majority of the new cases over the last 2 weeks have occurred in New York City, specifically Brooklyn, which reported 30 cases last week and 17 of the 32 new U.S. cases the week before.

Most of the 120 cases reported in the borough since the beginning of its outbreak in October of 2018 “have involved members of the Jewish Orthodox community. The initial child with measles was unvaccinated and acquired measles on a visit to Israel, where a large outbreak of the disease is occurring. Since then, there have been additional people from Brooklyn and Queens who were unvaccinated and acquired measles while in Israel. People who did not travel were also infected in Brooklyn or Rockland County,” the CDC said.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those new cases represent a 30% increase in measles cases for the year, bringing the total to 206 reported to the CDC through Feb. 28. After just 2 months, 2019 has had more cases than all but 3 other years over the last decade, CDC data show.

The 11th state to report a case of measles this year is New Jersey, which joins California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois (one outbreak), Kentucky, New York (three outbreaks), Oregon, Texas (one outbreak), and Washington (one outbreak), the CDC said.

The outbreak in Washington (4 new cases/70 for the year) had been the largest, but the majority of the new cases over the last 2 weeks have occurred in New York City, specifically Brooklyn, which reported 30 cases last week and 17 of the 32 new U.S. cases the week before.

Most of the 120 cases reported in the borough since the beginning of its outbreak in October of 2018 “have involved members of the Jewish Orthodox community. The initial child with measles was unvaccinated and acquired measles on a visit to Israel, where a large outbreak of the disease is occurring. Since then, there have been additional people from Brooklyn and Queens who were unvaccinated and acquired measles while in Israel. People who did not travel were also infected in Brooklyn or Rockland County,” the CDC said.

Point-of-care VL testing improves HIV suppression

SEATTLE – Point-of-care viral load testing improves HIV viral suppression and retention in care, according to a randomized trial of 390 subjects in South Africa.

Point-of-care (POC) testing delivers viral load results in about 2-3 hours, as opposed to the month or so patients wait to get results from a laboratory. The nearly instant turnaround gives clinicians the ability to identify patients who aren’t doing well – as indicated by high viral loads despite antiretroviral therapy (ART) – before they walk out the door, so immediate steps can be taken to address adherence or resistance problems.

However, POC viral load testing hasn’t really caught on in the United States, at least not yet, according to study leader Paul Drain, MD, assistant professor of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle.

To see if it would help, the team turned to a large public clinic in the city of Durban, and focused on adults who had been on ART for 6 months following HIV diagnosis. They randomized 195 to standard laboratory testing at study entrance, with a repeat at 6 months, at which point subjects had been on ART for 12 months; 195 others were randomized to POC testing with the Xpert HIV-1 Viral Load machine, from Cepheid, on the same schedule and with same-day counseling for those with high loads.

Treatment was otherwise similar between the groups, with clinic visits every 2 months and other measures as per South African HIV treatment guidelines.

POC testing made a difference. At study month 12,175 participants (89.7%) in the POC arm, but only 148 (75.9%) in the laboratory testing group, had reached the study’s primary endpoint: viral suppression with less than 200 copies/mL plus retention in care, meaning that subjects were still picking up their ART prescriptions.

Overall, POC testing increased viral load suppression by 10.3%, from 83.1% to 93.3% (P = .003) and retention by 7.7% from 84.6% to 92.3% (P = .03).

The investigators would like to evaluate the approach in the United States. Potentially, “POC testing will have a very important role in U.S. health care,” Dr. Drain said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

It “helps us identify those who are having problems right away, before they leave the clinic, because whether it’s in South Africa or Seattle, as soon as they leave, it’s very hard to get them back. The more you can do POC testing, the better we can intervene and help these people,” he said.

“You don’t need POC testing for everybody; a lot of people do just fine. They take their medications reliably. They don’t need to get their results back right away ... But there are people who have challenges and would benefit from additional adherence counseling” or who might need help overcoming drug resistance. “We want to identify” them quickly; POC testing may be the answer, he said.

The mean age in the study was 33 years, and 60% of the subjects were women. The median CD4 count at baseline was 468 cells/mm3. POC was $22 per test, versus $25 for lab testing.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Drain had no disclosures. Cepheid donated the POC testing machines.

SOURCE: Drain PK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 53LB.

SEATTLE – Point-of-care viral load testing improves HIV viral suppression and retention in care, according to a randomized trial of 390 subjects in South Africa.

Point-of-care (POC) testing delivers viral load results in about 2-3 hours, as opposed to the month or so patients wait to get results from a laboratory. The nearly instant turnaround gives clinicians the ability to identify patients who aren’t doing well – as indicated by high viral loads despite antiretroviral therapy (ART) – before they walk out the door, so immediate steps can be taken to address adherence or resistance problems.

However, POC viral load testing hasn’t really caught on in the United States, at least not yet, according to study leader Paul Drain, MD, assistant professor of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle.

To see if it would help, the team turned to a large public clinic in the city of Durban, and focused on adults who had been on ART for 6 months following HIV diagnosis. They randomized 195 to standard laboratory testing at study entrance, with a repeat at 6 months, at which point subjects had been on ART for 12 months; 195 others were randomized to POC testing with the Xpert HIV-1 Viral Load machine, from Cepheid, on the same schedule and with same-day counseling for those with high loads.

Treatment was otherwise similar between the groups, with clinic visits every 2 months and other measures as per South African HIV treatment guidelines.

POC testing made a difference. At study month 12,175 participants (89.7%) in the POC arm, but only 148 (75.9%) in the laboratory testing group, had reached the study’s primary endpoint: viral suppression with less than 200 copies/mL plus retention in care, meaning that subjects were still picking up their ART prescriptions.

Overall, POC testing increased viral load suppression by 10.3%, from 83.1% to 93.3% (P = .003) and retention by 7.7% from 84.6% to 92.3% (P = .03).

The investigators would like to evaluate the approach in the United States. Potentially, “POC testing will have a very important role in U.S. health care,” Dr. Drain said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

It “helps us identify those who are having problems right away, before they leave the clinic, because whether it’s in South Africa or Seattle, as soon as they leave, it’s very hard to get them back. The more you can do POC testing, the better we can intervene and help these people,” he said.

“You don’t need POC testing for everybody; a lot of people do just fine. They take their medications reliably. They don’t need to get their results back right away ... But there are people who have challenges and would benefit from additional adherence counseling” or who might need help overcoming drug resistance. “We want to identify” them quickly; POC testing may be the answer, he said.

The mean age in the study was 33 years, and 60% of the subjects were women. The median CD4 count at baseline was 468 cells/mm3. POC was $22 per test, versus $25 for lab testing.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Drain had no disclosures. Cepheid donated the POC testing machines.

SOURCE: Drain PK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 53LB.

SEATTLE – Point-of-care viral load testing improves HIV viral suppression and retention in care, according to a randomized trial of 390 subjects in South Africa.

Point-of-care (POC) testing delivers viral load results in about 2-3 hours, as opposed to the month or so patients wait to get results from a laboratory. The nearly instant turnaround gives clinicians the ability to identify patients who aren’t doing well – as indicated by high viral loads despite antiretroviral therapy (ART) – before they walk out the door, so immediate steps can be taken to address adherence or resistance problems.

However, POC viral load testing hasn’t really caught on in the United States, at least not yet, according to study leader Paul Drain, MD, assistant professor of global health at the University of Washington, Seattle.

To see if it would help, the team turned to a large public clinic in the city of Durban, and focused on adults who had been on ART for 6 months following HIV diagnosis. They randomized 195 to standard laboratory testing at study entrance, with a repeat at 6 months, at which point subjects had been on ART for 12 months; 195 others were randomized to POC testing with the Xpert HIV-1 Viral Load machine, from Cepheid, on the same schedule and with same-day counseling for those with high loads.

Treatment was otherwise similar between the groups, with clinic visits every 2 months and other measures as per South African HIV treatment guidelines.

POC testing made a difference. At study month 12,175 participants (89.7%) in the POC arm, but only 148 (75.9%) in the laboratory testing group, had reached the study’s primary endpoint: viral suppression with less than 200 copies/mL plus retention in care, meaning that subjects were still picking up their ART prescriptions.

Overall, POC testing increased viral load suppression by 10.3%, from 83.1% to 93.3% (P = .003) and retention by 7.7% from 84.6% to 92.3% (P = .03).

The investigators would like to evaluate the approach in the United States. Potentially, “POC testing will have a very important role in U.S. health care,” Dr. Drain said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

It “helps us identify those who are having problems right away, before they leave the clinic, because whether it’s in South Africa or Seattle, as soon as they leave, it’s very hard to get them back. The more you can do POC testing, the better we can intervene and help these people,” he said.

“You don’t need POC testing for everybody; a lot of people do just fine. They take their medications reliably. They don’t need to get their results back right away ... But there are people who have challenges and would benefit from additional adherence counseling” or who might need help overcoming drug resistance. “We want to identify” them quickly; POC testing may be the answer, he said.

The mean age in the study was 33 years, and 60% of the subjects were women. The median CD4 count at baseline was 468 cells/mm3. POC was $22 per test, versus $25 for lab testing.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. Dr. Drain had no disclosures. Cepheid donated the POC testing machines.

SOURCE: Drain PK et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 53LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Aquatic Antagonists: Stingray Injury Update

Incidence and Characteristics

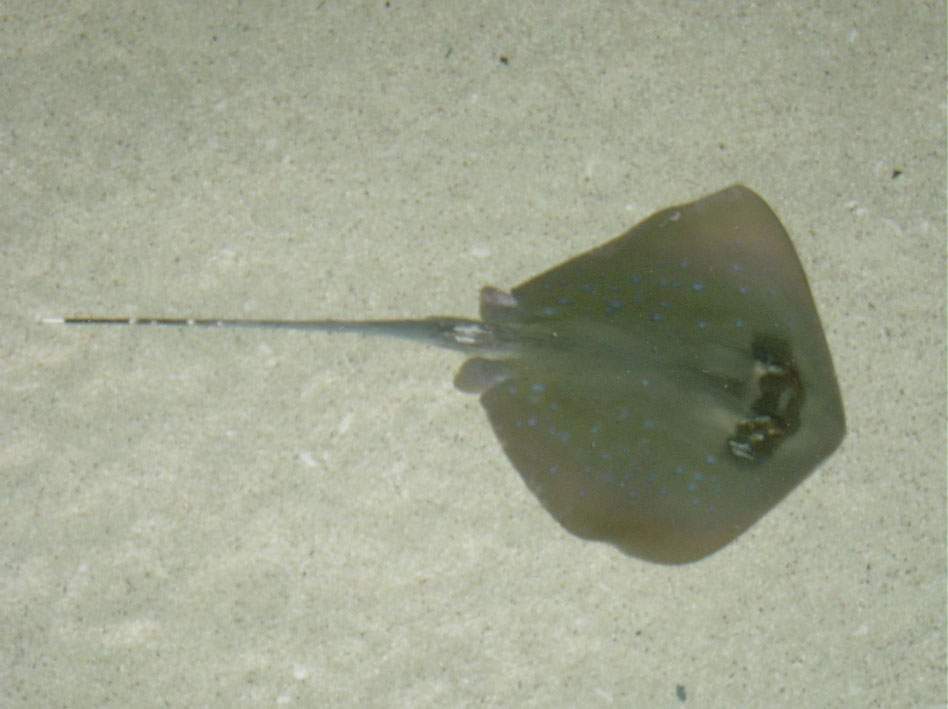

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

Incidence and Characteristics

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15

Infection

One major complication of stingray injuries is infection.8,9 Many bacterial species reside in stingray mucus, the marine environment, or on human skin that may be introduced during a single injury. Marine envenomations can involve organisms such as Vibrio, Aeromonas, and Mycobacterium species, which often are resistant to antibiotic prophylaxis covering common causes of soft-tissue infection such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.8,9,16,17 Additionally, physicians should cover for Clostridium species and ensure patients are up-to-date on vaccinations because severe cases of tetanus following stingray injuries have been reported.18 Lastly, fungal infections including fusariosis have been reported following stingray injuries and should be considered if a patient develops an infection.19

Several authors support the use of prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics in all but mild stingray injuries.8,9,20,21 Although no standardized definition exists, mild injuries generally represent patients with superficial lacerations or less, while deeper lacerations and puncture wounds require prophylaxis. Several authors agree on the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (eg, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily) for 5 to 7 days following severe stingray injuries.1,9,13,22 Other proposed antibiotic regimens include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) or tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily) for 7 days.13 Failure of ciprofloxacin therapy after 7 days has been reported, with resolution of infection after treatment with an intravenous cephalosporin for 7 days.20 Failure of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole therapy also has been reported, with one case requiring levofloxacin for a much longer course.21 Clinical follow-up remains essential after prescribing prophylactic antibiotics, as resistance is common.

Foreign Bodies

Stingray injuries also are often complicated by foreign bodies or retained spines.3,8 Although these complications are less severe than infection, all wounds should be explored for material under local anesthesia. Furthermore, there has been support for thorough debridement of necrotic tissue with referral to a hand specialist for deeper injuries to the hands as well as referral to a foot and ankle specialist for deeper injuries of the lower extremities.23,24 More serious injuries with penetration of vital structures, such as through the chest or abdomen, require immediate exploration in an operating room.1,24

Imaging

Routine imaging of stingray injuries remains controversial. In a case series of 119 patients presenting to a California emergency department with stingray injuries, Clark et al9 found that radiographs were not helpful. This finding likely is due in part to an inability to detect hypodense material such as integumentary or glandular tissue via radiography.3 However, radiographs have been used to identify retained stingray barbs in select cases in which retained barbs are suspected.2,25 Lastly, ultrasonography potentially may offer a better first choice when a barb is not readily apparent; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for more involved areas and for further visualization of suspected hypodense material, though at a higher expense.2,9

Biopsy

Biopsies of stingray injuries are rarely performed, and the findings are not well characterized. One case biopsied 2 months after injury showed a large zone of paucicellular necrosis with superficial ulceration and granulomatous inflammation. The stingray venom was most likely responsible for the pattern of necrosis noted in the biopsy.21

Avoidance and Prevention

Patients traveling to areas of the world inhabited by stingrays should receive counseling on how to avoid injury. Prior to entry, individuals can throw stones or use a long stick to clear their walking or swimming areas of venomous fish.26 Polarized sunglasses may help spot stingrays in shallow water. Furthermore, wading through water with a shuffling gait can help individuals avoid stepping directly on a stingray and also warns stingrays that someone is in the area. Individuals who spend more time in coastal waters or river systems inhabited by stingrays may invest in protective stingray gear such as leg guards or specialized wading boots.26 Lastly, fishermen should be advised to avoid handling stingrays with their hands and instead cut their fishing line to release the fish.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

- Aurbach PS. Envenomations by aquatic vertebrates. In: Auerbach PS. Wilderness Medicine. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007:1730-1749.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1986.

- Diaz JH. The evaluation, management, and prevention of stingray injuries in travelers. J Travel Med. 2008;15:102-109.

- Haddad V Jr, Neto DG, de Paula Neto JB, et al. Freshwater stingrays: study of epidemiologic, clinical and therapeutic aspects based on 84 envenomings in humans and some enzymatic activities of the venom. Toxicon. 2004;43:287-294.

- Marinkelle CJ. Accidents by venomous animals in Colombia. Ind Med Surg. 1966;35:988-992.

- Last PR, White WT, Caire JN, et al. Sharks and Rays of Borneo. Collingwood VIC, Australia: CSIRO Publishing; 2010.

- Mebs D. Venomous and Poisonous Animals: A Handbook for Biologists, Toxicologists and Toxinologists, Physicians and Pharmacists. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002.

- Clark AT, Clark RF, Cantrell FL. A retrospective review of the presentation and treatment of stingray stings reported to a poison control system. Am J Ther. 2017;24:E177-E180.

- Clark RF, Girard RH, Rao D, et al. Stingray envenomation: a retrospective review of clinical presentation and treatment in 119 cases. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:33-37.

- Mahjoubi L, Joyeux A, Delambre JF, et al. Near-death thoracic trauma caused by a stingray in the Indian Ocean. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29:262-263.

- Parra MW, Constantini EN, Rodas EB. Surviving a transfixing cardiac injury caused by a stingray barb. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:E115-E116.

- Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, et al. Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7912.

- Auerbach PS, Norris RL. Marine envenomation. In: Longo DL, Kasper SL, Jameson JL, et al, eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012:144-148.

- Cook MD, Matteucci MJ, Lall R, et al. Stingray envenomation. J Emerg Med. 2006;30:345-347.

- Bowers RC, Mustain MV. Disorders due to physical & environmental agents. In: Humphries RL, Stone C, eds. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment Emergency Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:835-861.

- Domingos MO, Franzolin MR, dos Anjos MT, et al. The influence of environmental bacteria in freshwater stingray wound-healing. Toxicon. 2011;58:147-153.

- Auerbach PS, Yajko DM, Nassos PS, et al. Bacteriology of the marine environment: implications for clinical therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:643-649.

- Torrez PP, Quiroga MM, Said R, et al. Tetanus after envenomations caused by freshwater stingrays. Toxicon. 2015;97:32-35.

- Hiemenz JW, Kennedy B, Kwon-Chung KJ. Invasive fusariosis associated with an injury by a stingray barb. J Med Vet Mycol. 1990;28:209-213.

- da Silva NJ Jr, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, et al. A severe accident caused by an ocellate river stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in central Brazil: how well do we really understand stingray venom chemistry, envenomation, and therapeutics? Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:2272-2288.

- Tartar D, Limova M, North J. Clinical and histopathologic findings in cutaneous sting ray wounds: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19261.

- Jarvis HC, Matheny LM, Clanton TO. Stingray injury to the webspace of the foot. Orthopedics. 2012;35:E762-E765.

- Trickett R, Whitaker IS, Boyce DE. Sting-ray injuries to the hand: case report, literature review and a suggested algorithm for management. J Plast Reconstruct Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:E270-E273.

- Fernandez I, Valladolid G, Varon J, et al. Encounters with venomous sea-life. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:103-112.

- O’Malley GF, O’Malley RN, Pham O, et al. Retained stingray barb and the importance of imaging. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:375-379.

- How to protect yourself from stingrays. Howcast website. https://www.howcast.com/videos/228034-how-to-protect-yourself-from-stingrays/. Accessed July 12, 2018.

Practice Points

- Acute pain associated with stingray injuries can be treated with hot water immersion.

- Stingray injuries are prone to secondary infection and poor wound healing.

Flu season shows signs of peaking

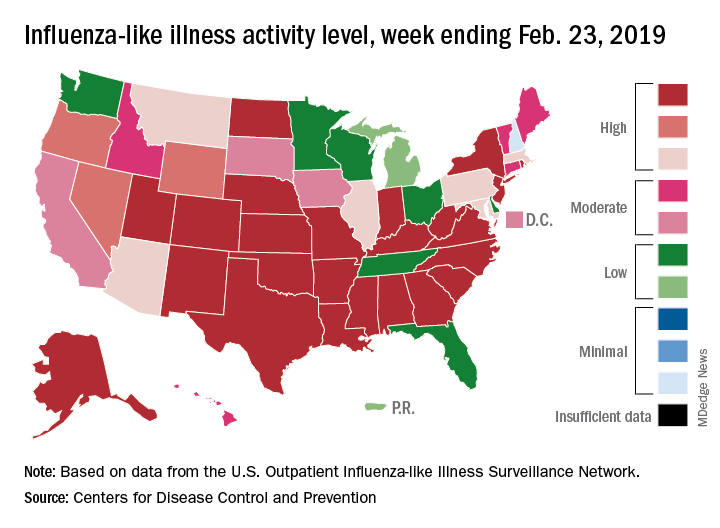

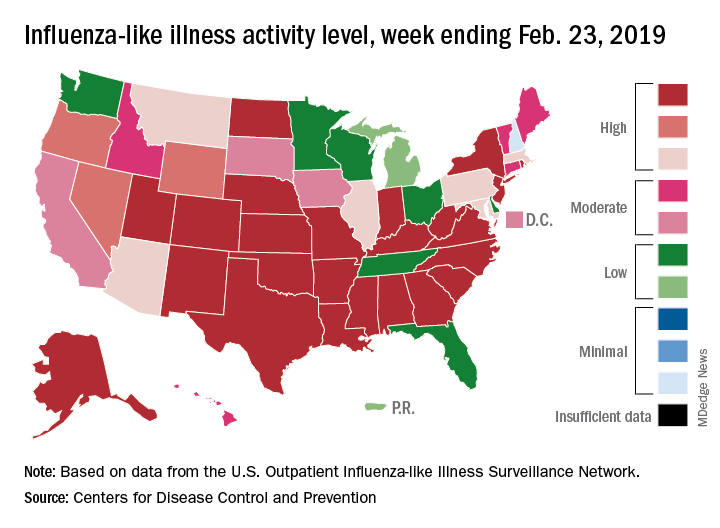

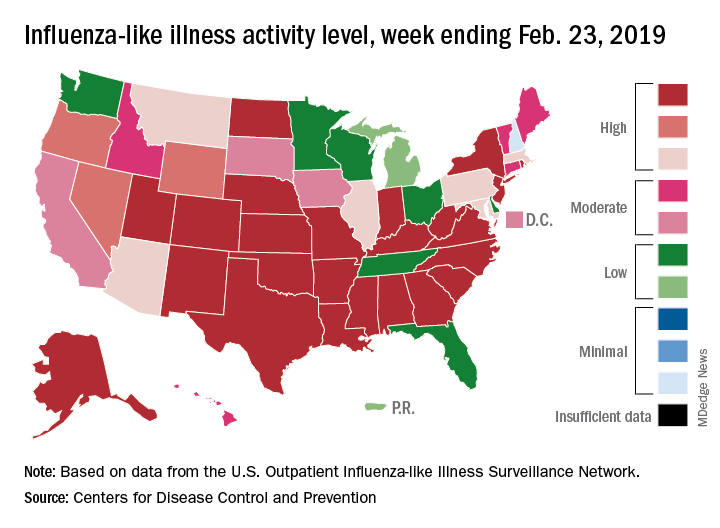

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as the major nationwide measure of influenza activity held steady for the week ending Feb. 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 5.0% for the most recent reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division said in its March 1 report. The previous week’s outpatient visit rate, originally reported as 5.1%, was revised this week to 5.0% as well, suggesting that flu activity is no longer increasing.

Activity at the state level was more mixed. The number of states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity stayed at 24 as Indiana and North Dakota replaced Tennessee and Wyoming, but the number of states in the high range (8-10) of the activity scale increased from 30 to 33, CDC data show.

The signs of plateauing ILI activity did not, however, extend to flu-related deaths, with 15 reported among children – the highest weekly number for the 2018-2019 season, although 11 actually occurred in previous weeks – during the week ending Feb. 23 and 289 deaths among all ages for the week ending Feb. 16, which is already more than the 268 listed the week before despite less complete reporting (82% vs. 97%), the CDC reported. Total flu-related deaths in children are now up to 56, compared with 138 at the corresponding point in the 2017-2018 season.

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as the major nationwide measure of influenza activity held steady for the week ending Feb. 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 5.0% for the most recent reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division said in its March 1 report. The previous week’s outpatient visit rate, originally reported as 5.1%, was revised this week to 5.0% as well, suggesting that flu activity is no longer increasing.

Activity at the state level was more mixed. The number of states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity stayed at 24 as Indiana and North Dakota replaced Tennessee and Wyoming, but the number of states in the high range (8-10) of the activity scale increased from 30 to 33, CDC data show.

The signs of plateauing ILI activity did not, however, extend to flu-related deaths, with 15 reported among children – the highest weekly number for the 2018-2019 season, although 11 actually occurred in previous weeks – during the week ending Feb. 23 and 289 deaths among all ages for the week ending Feb. 16, which is already more than the 268 listed the week before despite less complete reporting (82% vs. 97%), the CDC reported. Total flu-related deaths in children are now up to 56, compared with 138 at the corresponding point in the 2017-2018 season.

The 2018-2019 flu season may have peaked as the major nationwide measure of influenza activity held steady for the week ending Feb. 23, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 5.0% for the most recent reporting week, the CDC’s influenza division said in its March 1 report. The previous week’s outpatient visit rate, originally reported as 5.1%, was revised this week to 5.0% as well, suggesting that flu activity is no longer increasing.

Activity at the state level was more mixed. The number of states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity stayed at 24 as Indiana and North Dakota replaced Tennessee and Wyoming, but the number of states in the high range (8-10) of the activity scale increased from 30 to 33, CDC data show.

The signs of plateauing ILI activity did not, however, extend to flu-related deaths, with 15 reported among children – the highest weekly number for the 2018-2019 season, although 11 actually occurred in previous weeks – during the week ending Feb. 23 and 289 deaths among all ages for the week ending Feb. 16, which is already more than the 268 listed the week before despite less complete reporting (82% vs. 97%), the CDC reported. Total flu-related deaths in children are now up to 56, compared with 138 at the corresponding point in the 2017-2018 season.

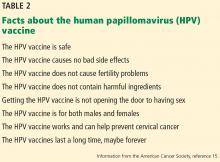

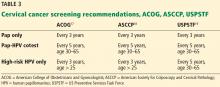

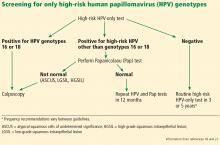

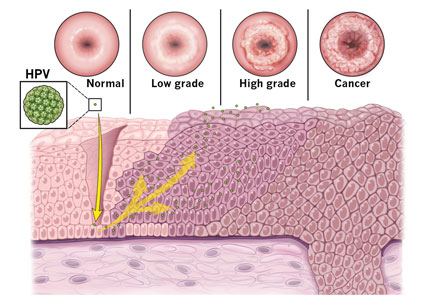

Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines

About 12% of women worldwide are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV).1 Persistent HPV infection with high-risk strains such as HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 cause nearly all cases of cervical cancer and some anal, vaginal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.2 An estimated 13,000 cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year in the United States alone.3

Up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. A number of changes have been made to the vaccination schedule within the past few years—patients younger than 15 need only 2 rather than 3 doses, and the vaccine itself can be used in adults up to age 45.

Vaccination and routine cervical cancer screening are both necessary to prevent this disease3 along with effective family and patient counseling. Here, we discuss the most up-to-date HPV vaccination recommendations, current cervical cancer screening guidelines, counseling techniques that increase vaccination acceptance rates, and follow-up protocols for abnormal cervical cancer screening results.

TYPES OF HPV VACCINES

HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts.4 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 HPV vaccines: