User login

Cutaneous Mycobacterium haemophilum Infection Involving the Upper Extremities: Diagnosis and Management Guidelines

Infection with Mycobacterium haemophilum, a rare, slow-growing organism, most commonly presents as ulcerating cutaneous lesions and subcutaneous nodules in immunocompromised adults.1 The most common clinical presentation in adults includes cutaneous lesions, nodules, cysts, and papules, with signs and symptoms of erythema, pain, pruritus, and drainage.2 Disseminated disease states of septic arthritis, pulmonary infiltration, and osteomyelitis, though life-threatening, are less common manifestations reported in highly immunocompromised persons.3

Infection with M haemophilum presents a challenge to the dermatology community because it is infrequently suspected and misidentified, resulting in delayed diagnosis. Additionally, M haemophilum is an extremely fastidious organism that requires heme-supplemented culture media and a carefully regulated low temperature for many consecutive weeks to yield valid culture results.1 These features contribute to complications and delays in diagnosis of an already overlooked source of infection.

We discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of 3 unusual cases of cutaneous M haemophilum infection involving the upper arms. The findings in these cases highlight the challenges inherent in diagnosis as well as the obstacles that arise in providing effective, long-term treatment of this infection.

Case Reports

Patient 1

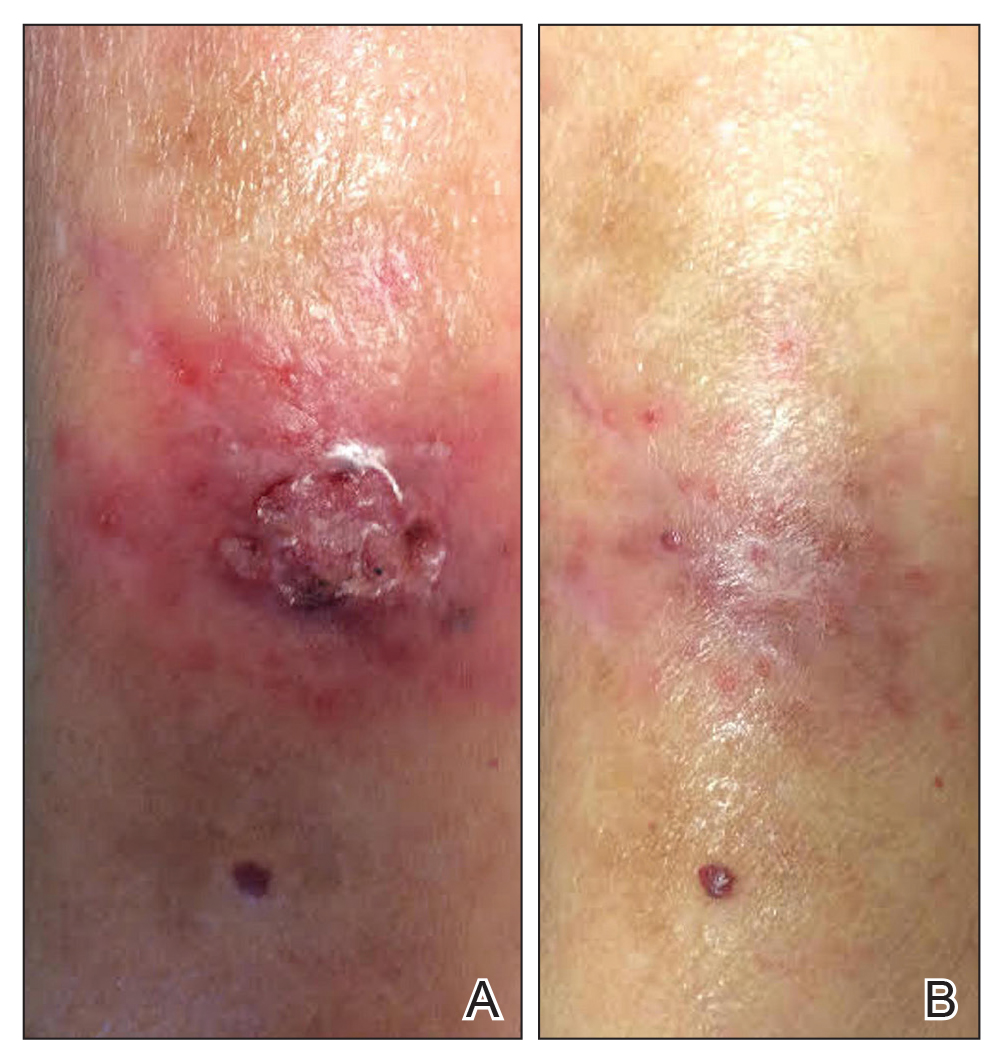

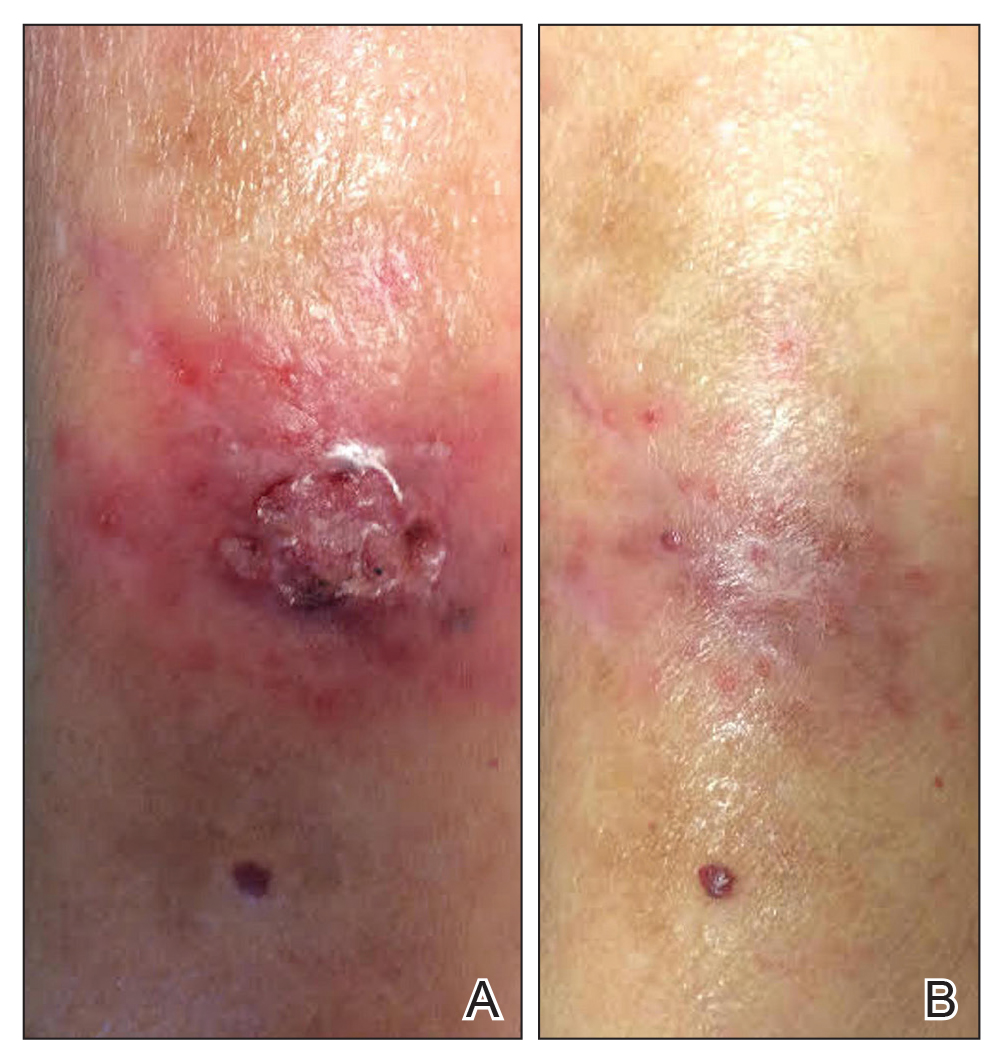

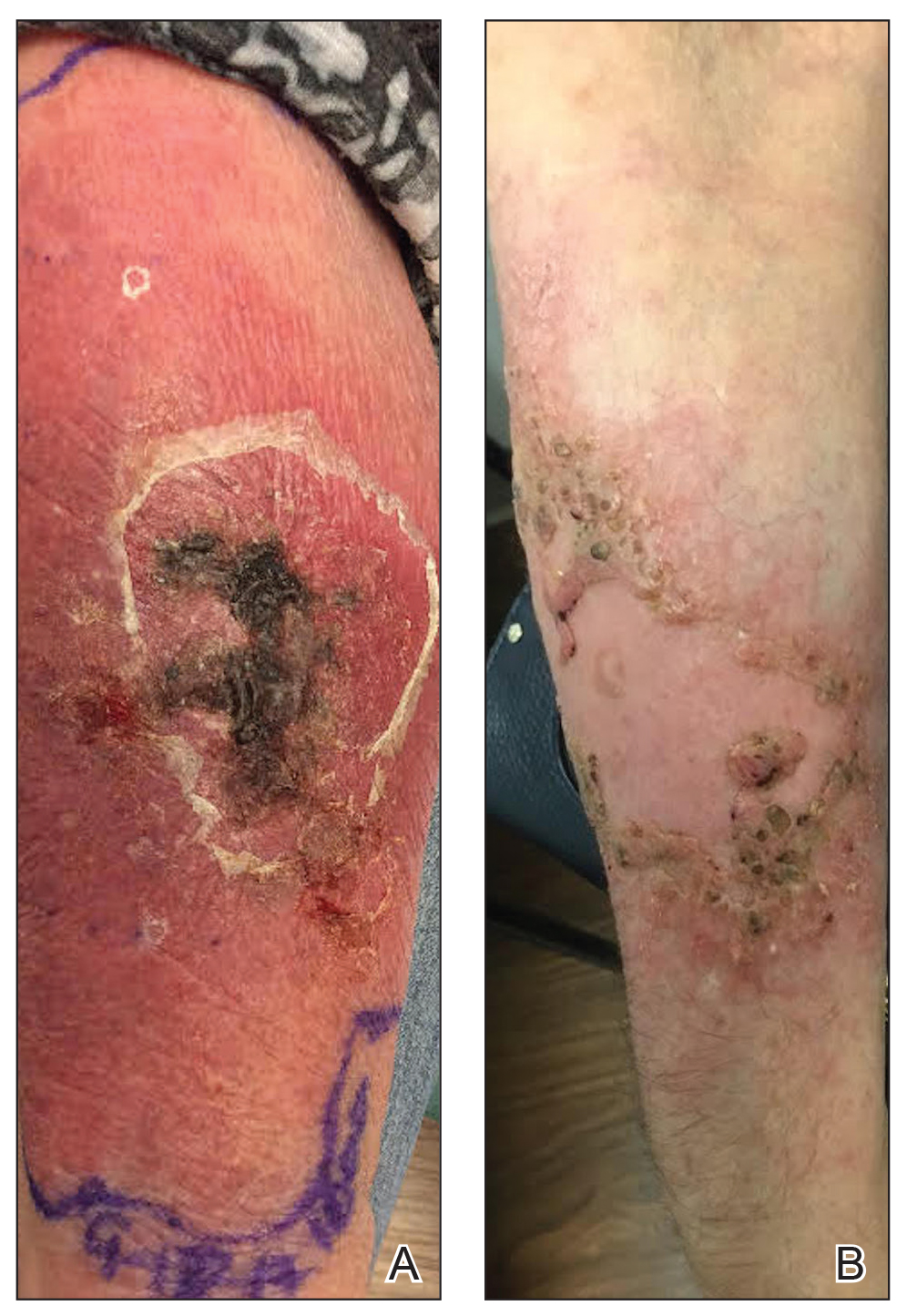

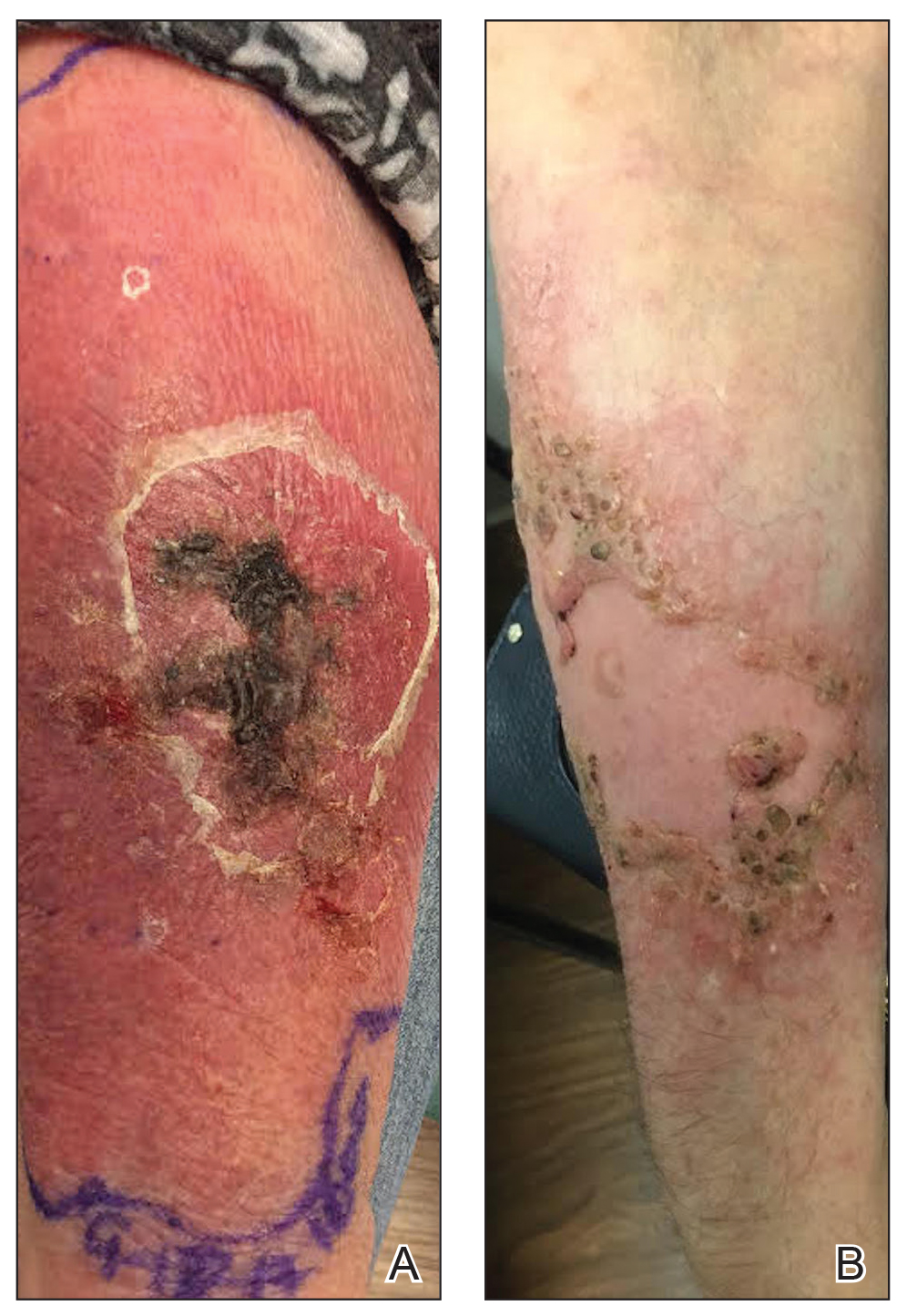

A 69-year-old woman with a medical history of a single functioning kidney and moderate psoriasis managed with low-dosage methotrexate presented with an erythematous nonhealing wound on the left forearm that developed after she was scratched by a dog. The pustules, appearing as bright red, tender, warm abscesses, had been present for 3 months and were distributed on the left proximal and distal dorsal forearm (Figure 1A). The patient reported no recent travel, sick contacts, allergies, or new medications.

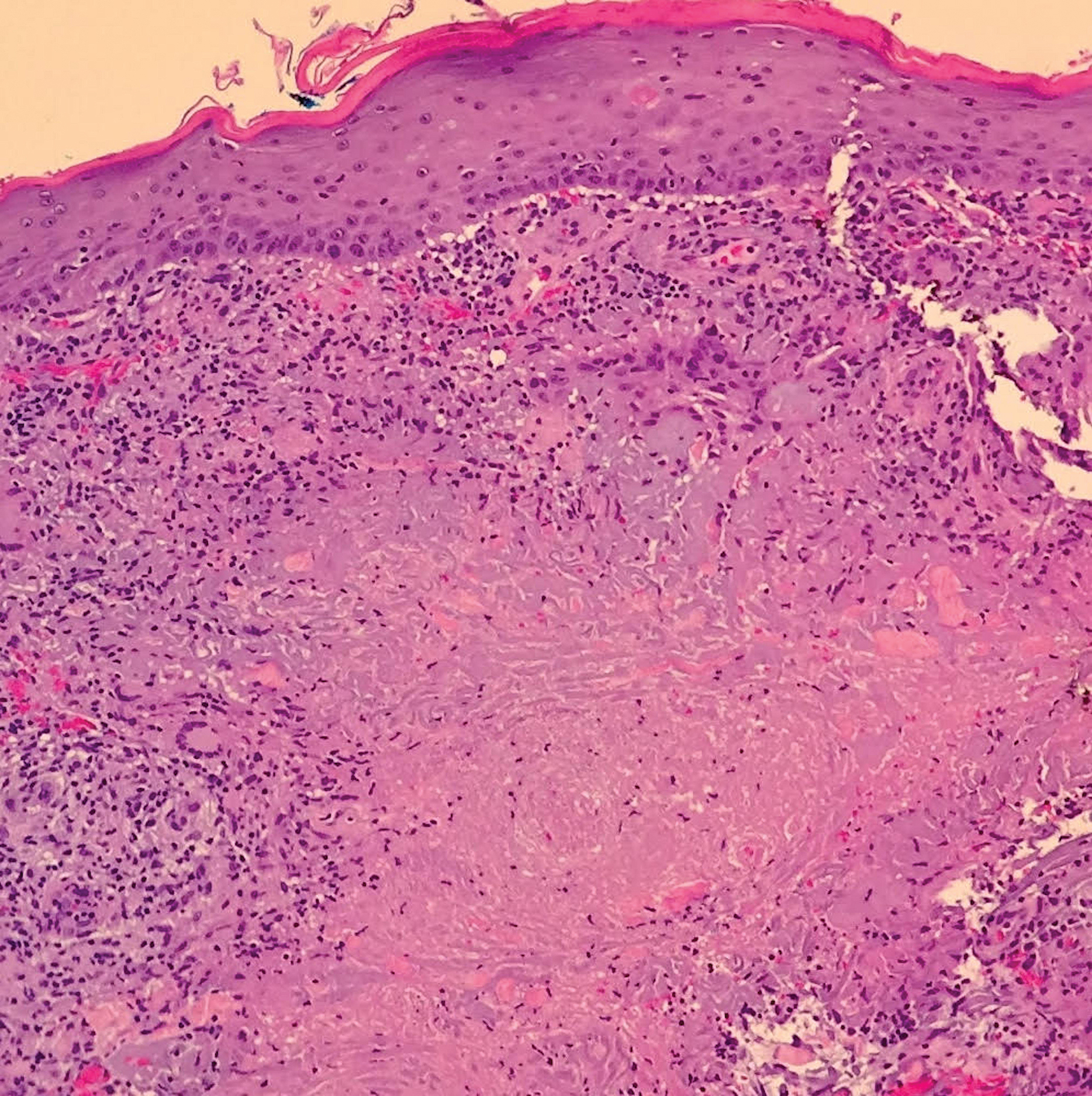

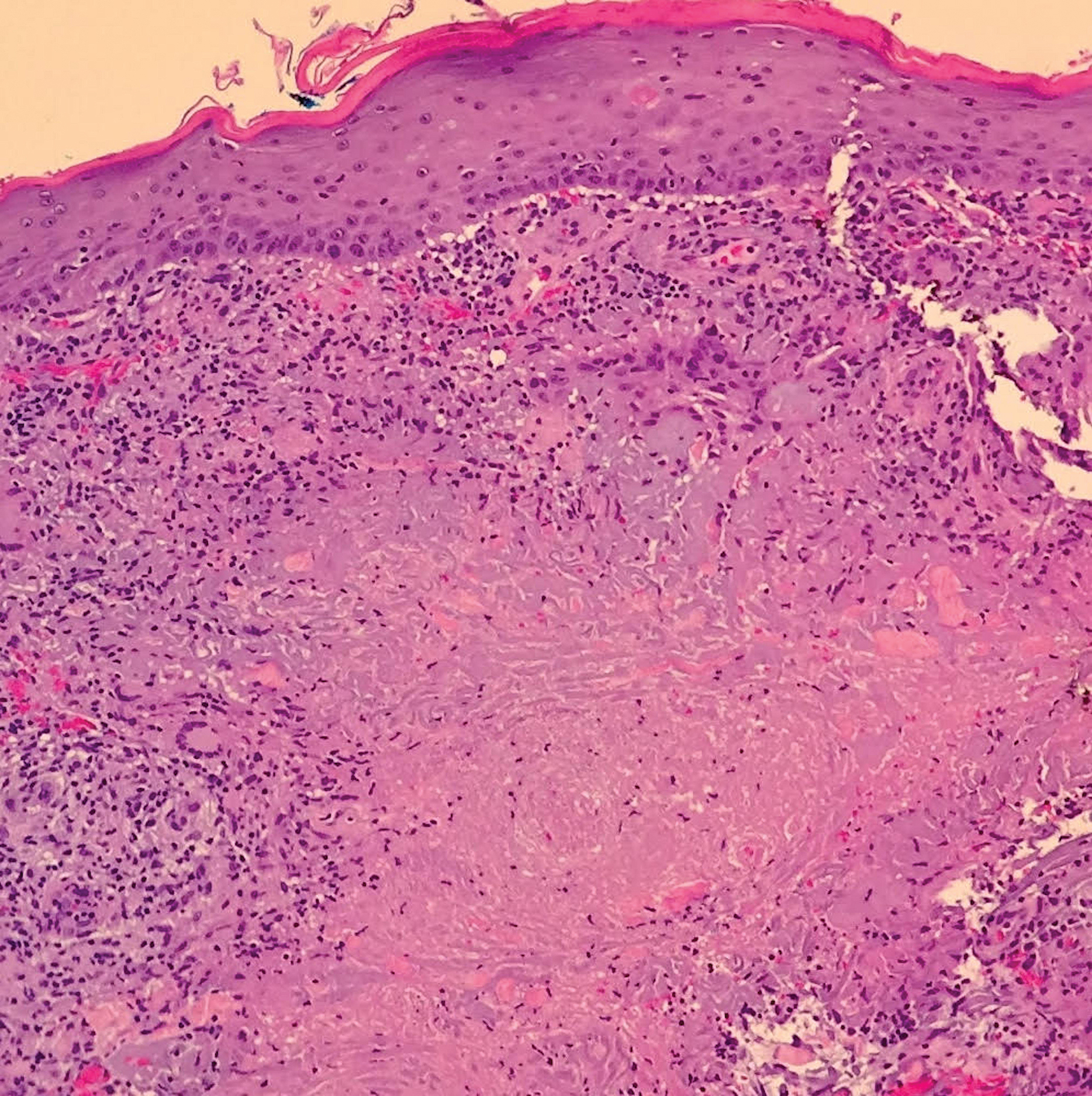

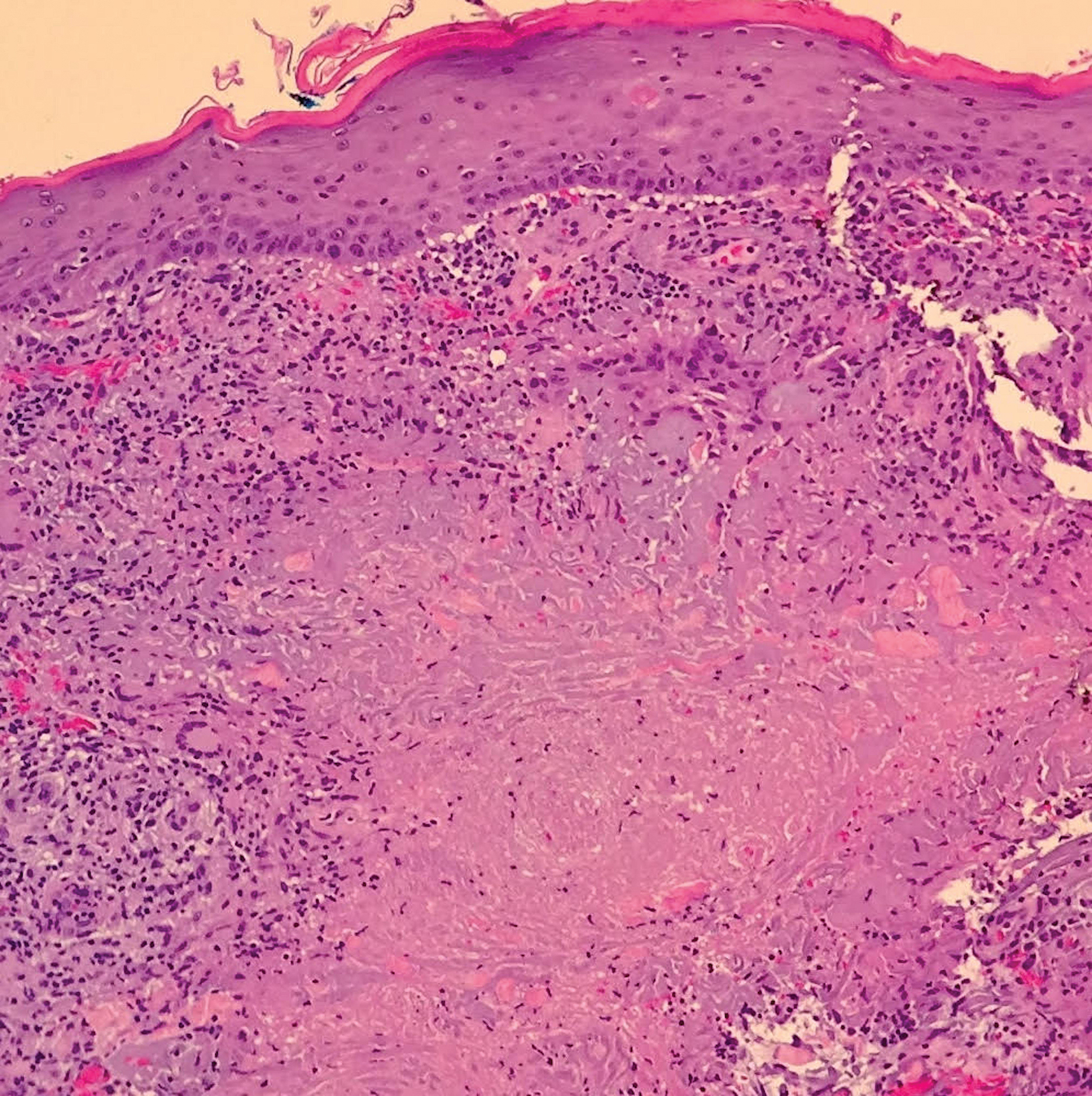

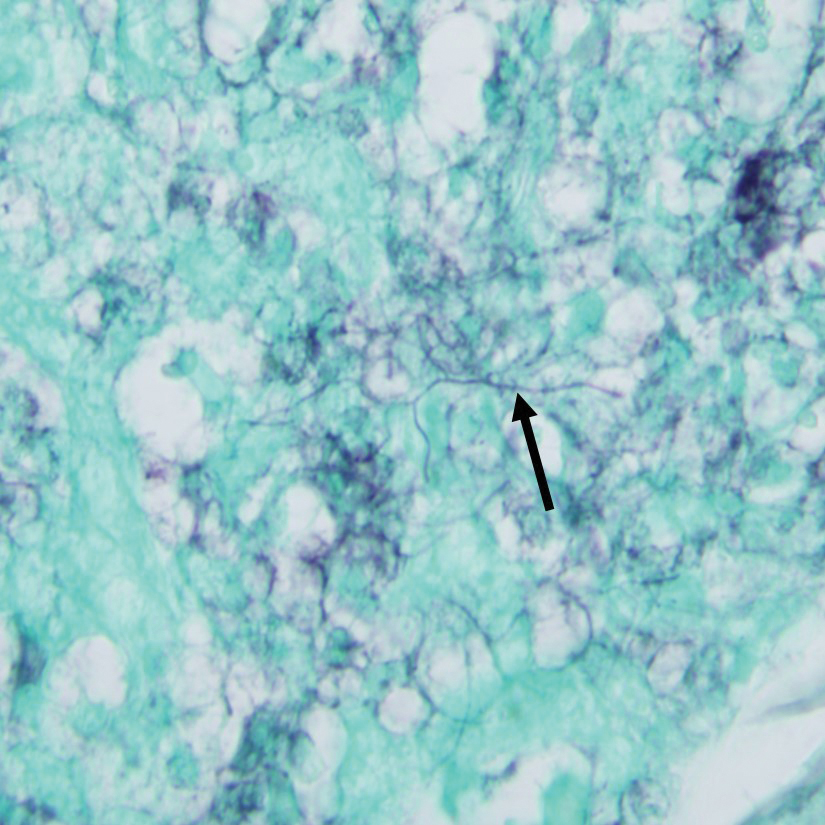

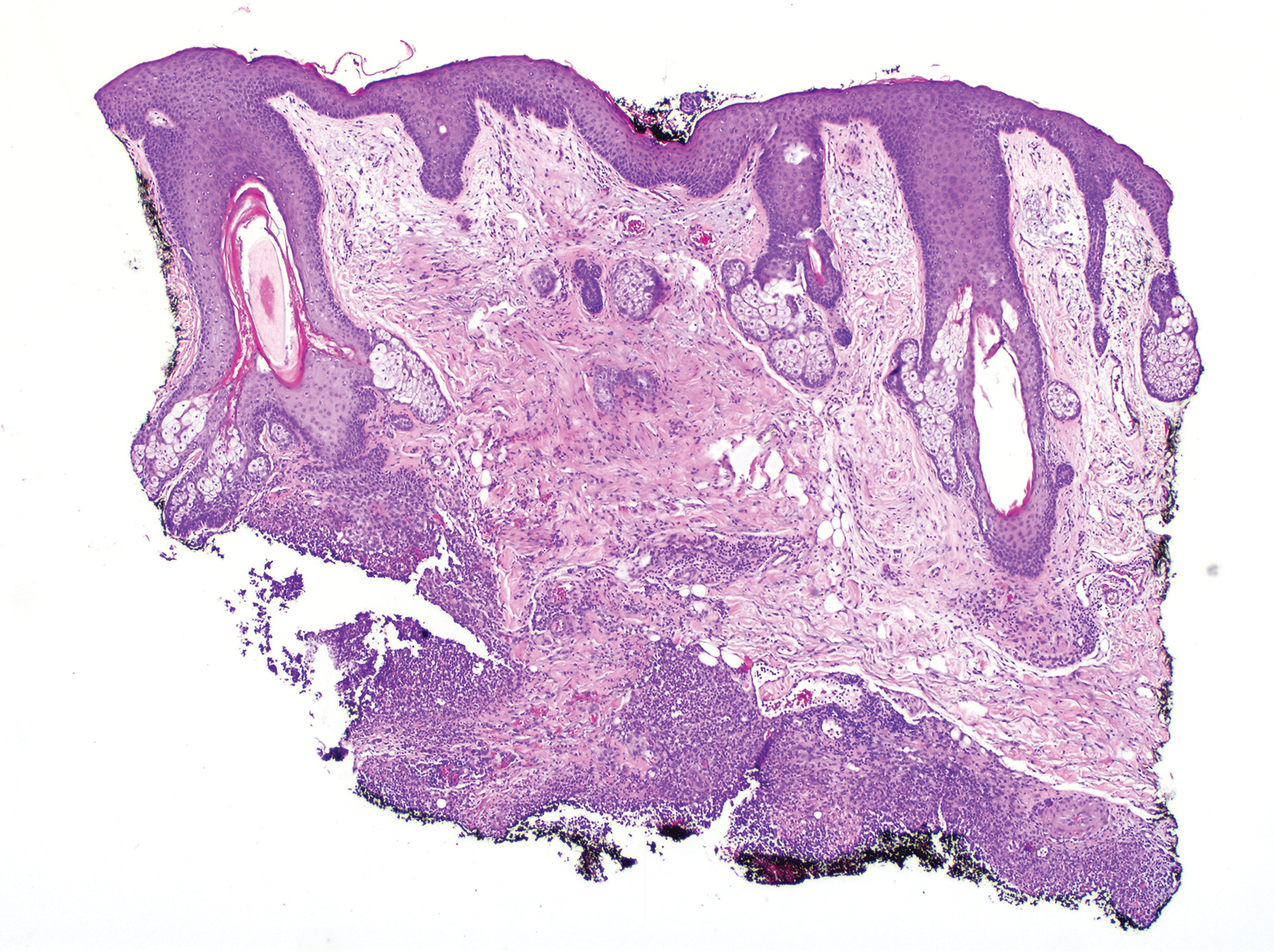

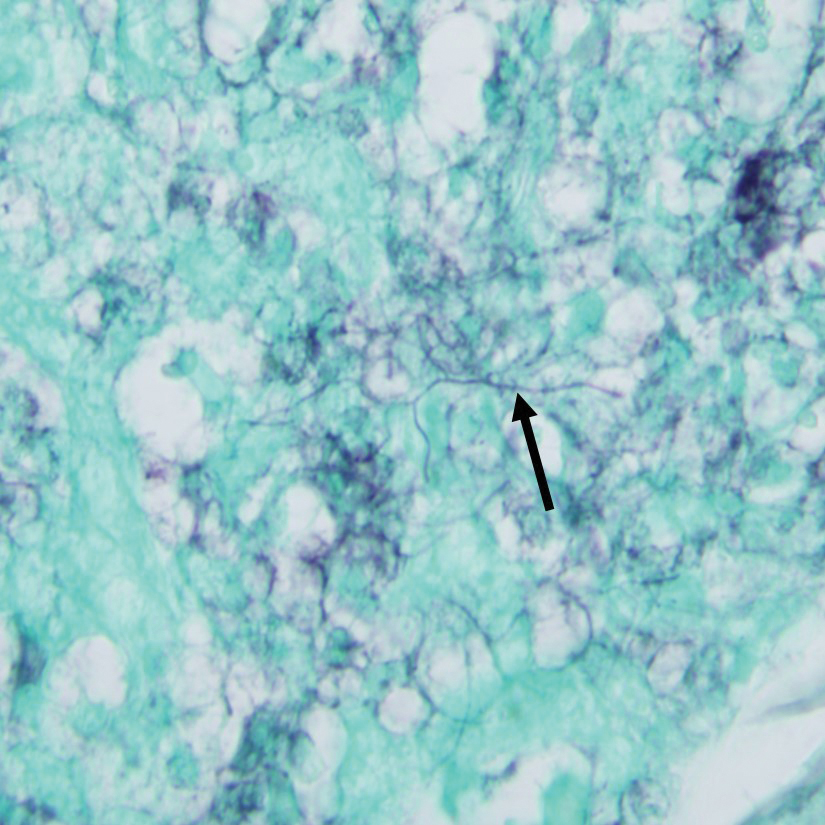

A shave biopsy was initially obtained. Swab specimens were sent for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial culture following discontinuation of methotrexate. Initial histopathologic analysis revealed aggregates of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells within the dermis, surrounded by infiltrates of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 2), consistent with a dermal noncaseating granulomatosis. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB), periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for pathogenic microorganisms. There was no evidence of vasculitis.

Despite negative special stains, an infectious cause was still suspected. Oral doxycycline monohydrate 100 mg twice daily, oral fluconazole 200 mg daily, and econazole cream 1% were prescribed because of concern for mycobacterial infection and initial growth of Candida parapsilosis in the swab culture.

A punch biopsy also was performed at this time for both repeat histopathologic analysis and tissue culture. Follow-up appointments were scheduled every 2 weeks. Staining by AFB of the repeat histopathologic specimen was negative.

The patient demonstrated symptomatic and aesthetic improvement (Figure 1B) during consecutive regular follow-up appointments while culture results were pending. No lesions appeared above the left elbow and she had no lymphadenopathy. Results of blood chemistry analyses and complete blood cell count throughout follow-up were normal.

The final tissue culture report obtained 7 weeks after initial presentation showed growth of M haemophilum despite a negative smear. The swab culture that initially was taken did not grow pathogenic organisms.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who confirmed that the atypical mycobacterial infection likely was the main source of the cutaneous lesions. She was instructed to continue econazole cream 1% and was given prescriptions for clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily, and rifampin 300 mg twice daily for a total duration of 12 to 18 months. The patient has remained on this triple-drug regimen and demonstrated improvement in the lesions. She has been off methotrexate while on antibiotic therapy.

Patient 2

A 79-year-old man with a medical history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma presented with a nonhealing, painful, red lesion on the left forearm of 1 week’s duration. Physical examination revealed a violaceous nontender plaque with erosions and desquamation that was initially diagnosed as a carbuncle. The patient reported a similar eruption on the right foot that was successfully treated with silver sulfadiazine by another physician.

Biopsy was performed by the shave method for histologic analysis and tissue culture. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed because of high suspicion of infection. Histologic findings revealed granulomatous inflammation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, reported as squamous cell carcinoma. A second opinion confirmed suspicion of an infectious process; the patient remained on doxycycline. During follow-up, the lesion progressed to a 5-cm plaque studded with pustules and satellite papules. Multiple additional tissue cultures were performed over 2 months until “light growth” of M haemophilum was reported.

The patient showed minimal improvement on tetracycline antibiotics. His condition was complicated by a photosensitivity reaction to doxycycline on the left and right forearms, hands, and nose. Consequently, triamcinolone was prescribed, doxycycline was discontinued, and minocycline 100 mg twice daily and ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily were prescribed.

Nine months after initial presentation, the lesions were still present but remarkably improved. The antibiotic regimen was discontinued after 11 months.

Patient 3

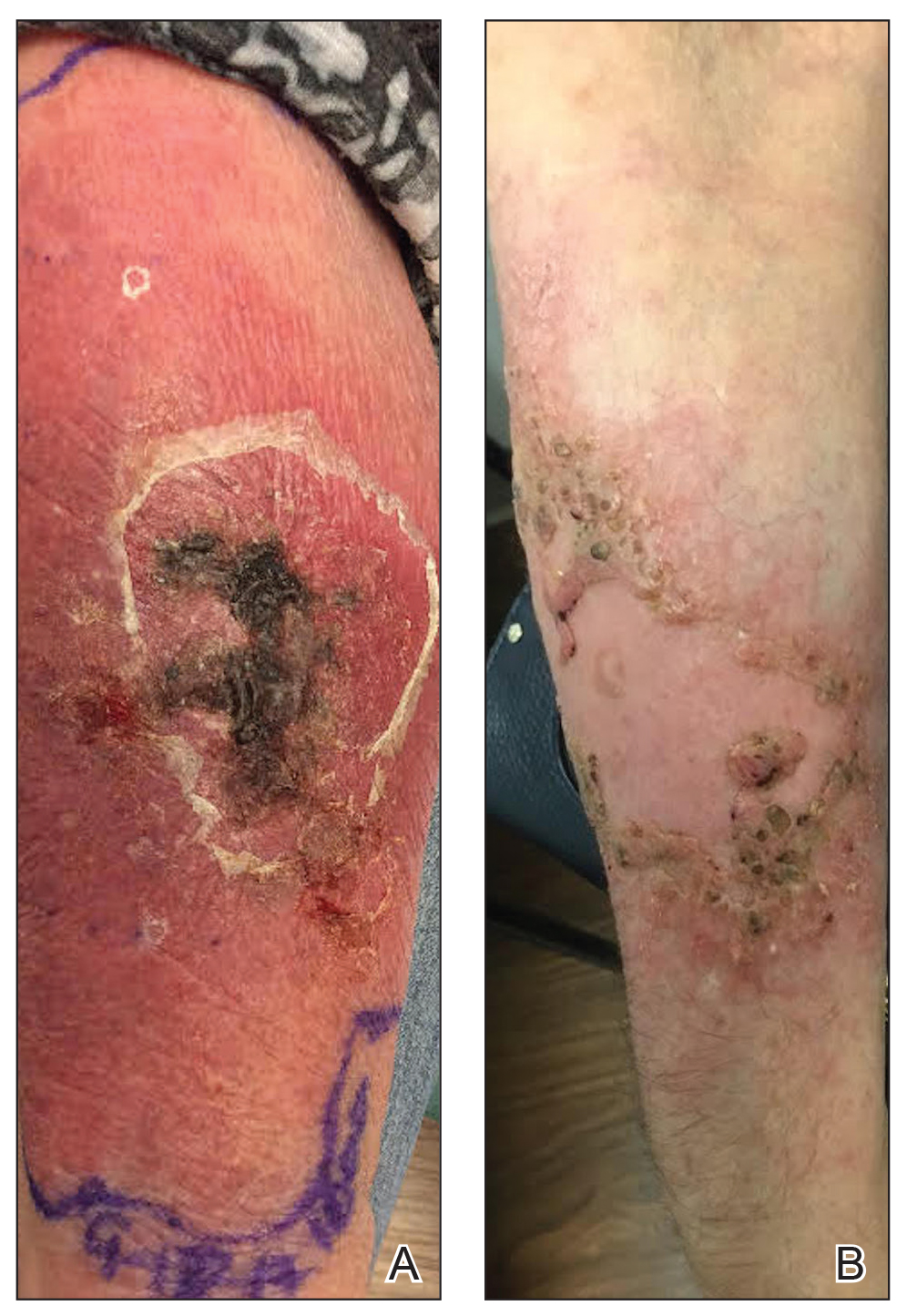

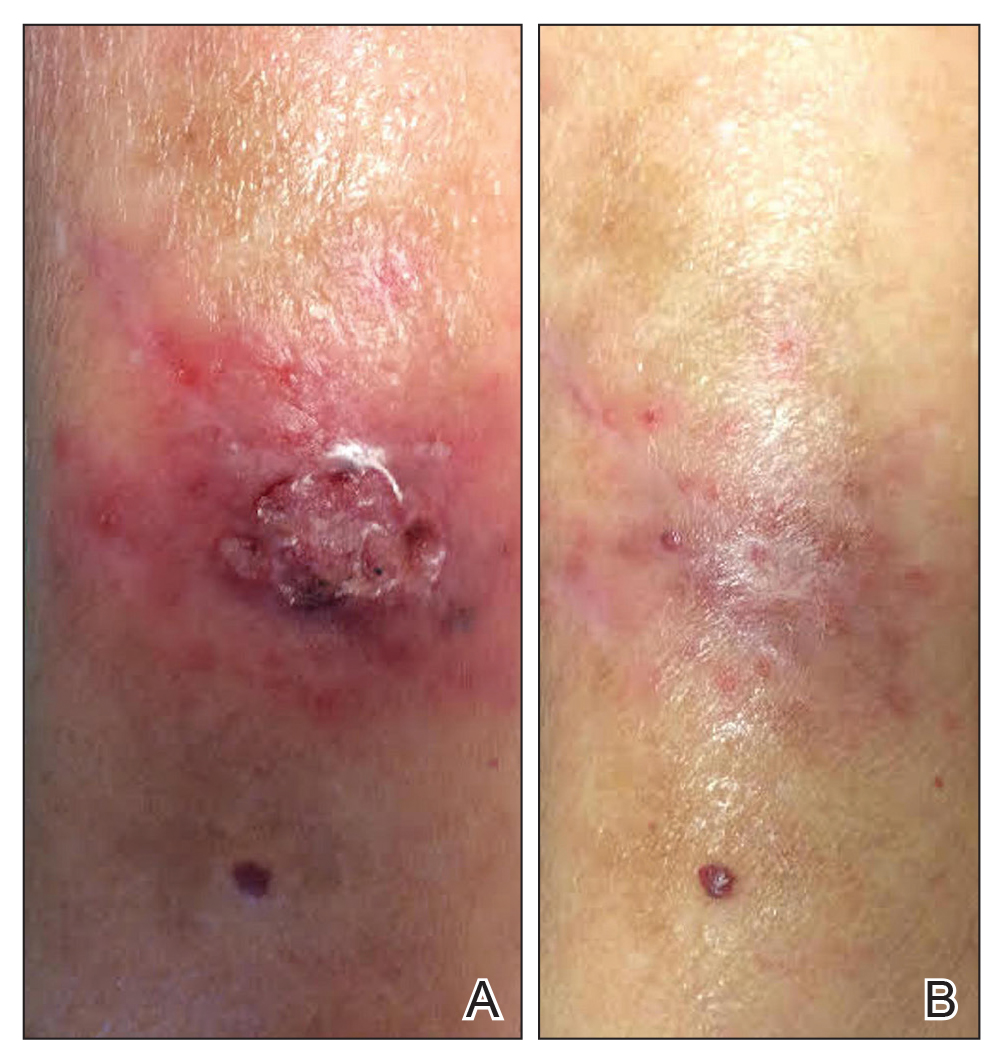

A 77-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate and abatacept as well as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with narrowband UVB radiation presented to the emergency department with fever and an inflamed right forearm (Figure 3A). Initial bacterial cultures of the wound and blood were negative.

The patient was treated with vancomycin and discharged on cephalexin once she became afebrile. She was seen at our office the next week for further evaluation. We recommended that she discontinue all immunosuppressant medications. A 4-mm tissue biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and a separate 4-mm punch biopsy for culture were performed while she was taking cephalexin. Histopathologic analysis revealed numerous neutrophilic abscesses; however, Gram, AFB, and fungal stains were negative.

Arm edema and pustules slowly resolved, but the eschar and verrucous plaques continued to slowly progress while the patient was off immunosuppression. She was kept off antibiotics until mycobacterial culture was positive at 4 weeks, at which time she was placed on doxycycline and clarithromycin. Final identification of M haemophilum was made at 6 weeks; consequently, doxycycline was discontinued and she was referred to infectious disease for multidrug therapy. She remained afebrile during the entire 6 weeks until cultures were final.

While immunosuppressants were discontinued and clarithromycin was administered, the plaque changed from an edematous pustular dermatitis to a verrucous crusted plaque. Neither epitrochlear nor axillary lymphadenopathy was noted during the treatment period. The infectious disease specialist prescribed azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin, which produced marked improvement (Figure 3B). The patient has remained off immunosuppressive therapy while on antibiotics.

Comment

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Mycobacterium haemophilum is a rare infectious organism that affects primarily immunocompromised adults but also has been identified in immunocompetent adults and pediatric patients.2 Commonly affected immunosuppressed groups include solid organ transplant recipients, bone marrow transplant recipients, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, and patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The infection typically presents as small violaceous papules and pustules that become painful and erythematous, with progression and draining ulceration in later stages.2 In our cases, all lesions tended to evolve into a verrucous plaque that slowly resolved with antibiotic therapy.

Due to the rarity of this infection, the initial differential diagnosis can include infection with other mycobacteria, Sporothrix, Staphylococcus aureus, and other fungal pathogens. Misdiagnosis is a common obstacle in the treatment of M haemophilum due to its rarity, often negative AFB stains, and slow growth on culture media; therefore, tissue culture is essential to successful diagnosis and management. The natural reservoir of M haemophilum is unknown, but infection has been associated with contaminated water sources.1 In one case (patient 1), symptoms developed after a dog scratch; the other 2 patients were unaware of injury to the skin.Laboratory diagnosis of M haemophilum is inherently difficult and protracted. The species is a highly fastidious and slow-growing Mycobacterium that requires cooler (30°C) incubation for many weeks on agar medium enriched with hemin or ferric ammonium citrate to obtain valid growth.1 To secure timely diagnosis, the organism’s slow agar growth warrants immediate tissue culture and biopsy when an immunocompromised patient presents with clinical features of atypical infection of an extremity. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection likely is underreported because of these difficulties in diagnosis.

Management

Although there are no standard guidelines for antibiotic treatment of M haemophilum, the current literature recommends triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifamycin for at least 12 to 24 months.2

Upon clinical suspicion of an atypical Mycobacterium, we recommend a macrolide antibiotic over doxycycline, however, because this class of agents maintains broad coverage while being more specific for atypical mycobacteria. Although an atypical Mycobacterium was suspected early in the presentation in our cases, we discourage immediate use of triple-agent antibiotic therapy until laboratory evidence is procured to minimize antibiotic overuse in patients who do not have a final diagnosis. Single-agent therapy for prolonged treatment is discouraged for atypical mycobacterial infections because of the high risk of antibiotic resistance. Therapy should be tailored to the needs of the individual based on the extent of dissemination of disease and the severity of immunosuppression.1,2

Additionally, underlying disease that results in immunosuppression might necessitate treatment reevaluation (as occurred in our cases) requiring cessation of immunosuppressive drugs, extended careful monitoring, and pharmacotherapeutic readjustment through the course of treatment. The degree to which antibiotics contribute to eradication of M haemophilum is unknown; therefore, it is recommended that long-term antibiotic use and treatment aimed at recovering the immunocompromised state (eg, highly active antiretroviral therapy in a patient with AIDS) be implemented.2

Conclusion

Our 3 cases of M haemophilum infection involved the upper extremities of immunosuppressed patients older than 65 years. This propensity to affect the upper extremities could possibly be due to the lower temperature required for growth of M haemophilum. Initial histopathologic study showed granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrates, yet histopathologic specimens from all 3 patients failed to display positive AFB staining, which delayed the initial antibiotic choice. In all cases, diagnosis was made by tissue culture after swab culture failed to grow the pathogen. Furthermore, the 3 cases took approximately 6 weeks to achieve final identification of the organism. Neither clinical lymphadenopathy nor systemic spread was noted in our patients; immunosuppression was discontinued when possible.

Mycobacterium haemophilum is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening infection that should be suspected in immunocompromised adults who present with atypical cellulitis of the extremities. The ultimate diagnosis often is delayed because the organism grows slowly (as long as 8 weeks) in tissue culture. For that reason, empiric antibiotic treatment, including a macrolide, should be considered in patients with disseminated or severe infection or critical immunosuppression and in those who do not demonstrate improvement in symptoms once immunosuppressants are withheld. A prolonged course of multiple-drug antibiotic therapy has proved to be effective for treating cutaneous infection with M haemophilum.

- Lindeboom JA, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LE, van Soolingen D, et al. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Mycobacterium haemophilum infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:701-717.

- Tangkosakul T, Hongmanee P, Malathum K. Cutaneous Mycobacterium haemophilum infections in immunocompromised patients in a tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand: under-reported/under-recognized infection. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:E002618.

- Sabeti S, Pourabdollah Tootkaboni M, Abdolahi M, et al. Mycobacterium haemophilum: a report of cutaneous infection in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5(suppl 1):S236.

Infection with Mycobacterium haemophilum, a rare, slow-growing organism, most commonly presents as ulcerating cutaneous lesions and subcutaneous nodules in immunocompromised adults.1 The most common clinical presentation in adults includes cutaneous lesions, nodules, cysts, and papules, with signs and symptoms of erythema, pain, pruritus, and drainage.2 Disseminated disease states of septic arthritis, pulmonary infiltration, and osteomyelitis, though life-threatening, are less common manifestations reported in highly immunocompromised persons.3

Infection with M haemophilum presents a challenge to the dermatology community because it is infrequently suspected and misidentified, resulting in delayed diagnosis. Additionally, M haemophilum is an extremely fastidious organism that requires heme-supplemented culture media and a carefully regulated low temperature for many consecutive weeks to yield valid culture results.1 These features contribute to complications and delays in diagnosis of an already overlooked source of infection.

We discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of 3 unusual cases of cutaneous M haemophilum infection involving the upper arms. The findings in these cases highlight the challenges inherent in diagnosis as well as the obstacles that arise in providing effective, long-term treatment of this infection.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 69-year-old woman with a medical history of a single functioning kidney and moderate psoriasis managed with low-dosage methotrexate presented with an erythematous nonhealing wound on the left forearm that developed after she was scratched by a dog. The pustules, appearing as bright red, tender, warm abscesses, had been present for 3 months and were distributed on the left proximal and distal dorsal forearm (Figure 1A). The patient reported no recent travel, sick contacts, allergies, or new medications.

A shave biopsy was initially obtained. Swab specimens were sent for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial culture following discontinuation of methotrexate. Initial histopathologic analysis revealed aggregates of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells within the dermis, surrounded by infiltrates of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 2), consistent with a dermal noncaseating granulomatosis. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB), periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for pathogenic microorganisms. There was no evidence of vasculitis.

Despite negative special stains, an infectious cause was still suspected. Oral doxycycline monohydrate 100 mg twice daily, oral fluconazole 200 mg daily, and econazole cream 1% were prescribed because of concern for mycobacterial infection and initial growth of Candida parapsilosis in the swab culture.

A punch biopsy also was performed at this time for both repeat histopathologic analysis and tissue culture. Follow-up appointments were scheduled every 2 weeks. Staining by AFB of the repeat histopathologic specimen was negative.

The patient demonstrated symptomatic and aesthetic improvement (Figure 1B) during consecutive regular follow-up appointments while culture results were pending. No lesions appeared above the left elbow and she had no lymphadenopathy. Results of blood chemistry analyses and complete blood cell count throughout follow-up were normal.

The final tissue culture report obtained 7 weeks after initial presentation showed growth of M haemophilum despite a negative smear. The swab culture that initially was taken did not grow pathogenic organisms.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who confirmed that the atypical mycobacterial infection likely was the main source of the cutaneous lesions. She was instructed to continue econazole cream 1% and was given prescriptions for clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily, and rifampin 300 mg twice daily for a total duration of 12 to 18 months. The patient has remained on this triple-drug regimen and demonstrated improvement in the lesions. She has been off methotrexate while on antibiotic therapy.

Patient 2

A 79-year-old man with a medical history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma presented with a nonhealing, painful, red lesion on the left forearm of 1 week’s duration. Physical examination revealed a violaceous nontender plaque with erosions and desquamation that was initially diagnosed as a carbuncle. The patient reported a similar eruption on the right foot that was successfully treated with silver sulfadiazine by another physician.

Biopsy was performed by the shave method for histologic analysis and tissue culture. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed because of high suspicion of infection. Histologic findings revealed granulomatous inflammation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, reported as squamous cell carcinoma. A second opinion confirmed suspicion of an infectious process; the patient remained on doxycycline. During follow-up, the lesion progressed to a 5-cm plaque studded with pustules and satellite papules. Multiple additional tissue cultures were performed over 2 months until “light growth” of M haemophilum was reported.

The patient showed minimal improvement on tetracycline antibiotics. His condition was complicated by a photosensitivity reaction to doxycycline on the left and right forearms, hands, and nose. Consequently, triamcinolone was prescribed, doxycycline was discontinued, and minocycline 100 mg twice daily and ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily were prescribed.

Nine months after initial presentation, the lesions were still present but remarkably improved. The antibiotic regimen was discontinued after 11 months.

Patient 3

A 77-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate and abatacept as well as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with narrowband UVB radiation presented to the emergency department with fever and an inflamed right forearm (Figure 3A). Initial bacterial cultures of the wound and blood were negative.

The patient was treated with vancomycin and discharged on cephalexin once she became afebrile. She was seen at our office the next week for further evaluation. We recommended that she discontinue all immunosuppressant medications. A 4-mm tissue biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and a separate 4-mm punch biopsy for culture were performed while she was taking cephalexin. Histopathologic analysis revealed numerous neutrophilic abscesses; however, Gram, AFB, and fungal stains were negative.

Arm edema and pustules slowly resolved, but the eschar and verrucous plaques continued to slowly progress while the patient was off immunosuppression. She was kept off antibiotics until mycobacterial culture was positive at 4 weeks, at which time she was placed on doxycycline and clarithromycin. Final identification of M haemophilum was made at 6 weeks; consequently, doxycycline was discontinued and she was referred to infectious disease for multidrug therapy. She remained afebrile during the entire 6 weeks until cultures were final.

While immunosuppressants were discontinued and clarithromycin was administered, the plaque changed from an edematous pustular dermatitis to a verrucous crusted plaque. Neither epitrochlear nor axillary lymphadenopathy was noted during the treatment period. The infectious disease specialist prescribed azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin, which produced marked improvement (Figure 3B). The patient has remained off immunosuppressive therapy while on antibiotics.

Comment

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Mycobacterium haemophilum is a rare infectious organism that affects primarily immunocompromised adults but also has been identified in immunocompetent adults and pediatric patients.2 Commonly affected immunosuppressed groups include solid organ transplant recipients, bone marrow transplant recipients, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, and patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The infection typically presents as small violaceous papules and pustules that become painful and erythematous, with progression and draining ulceration in later stages.2 In our cases, all lesions tended to evolve into a verrucous plaque that slowly resolved with antibiotic therapy.

Due to the rarity of this infection, the initial differential diagnosis can include infection with other mycobacteria, Sporothrix, Staphylococcus aureus, and other fungal pathogens. Misdiagnosis is a common obstacle in the treatment of M haemophilum due to its rarity, often negative AFB stains, and slow growth on culture media; therefore, tissue culture is essential to successful diagnosis and management. The natural reservoir of M haemophilum is unknown, but infection has been associated with contaminated water sources.1 In one case (patient 1), symptoms developed after a dog scratch; the other 2 patients were unaware of injury to the skin.Laboratory diagnosis of M haemophilum is inherently difficult and protracted. The species is a highly fastidious and slow-growing Mycobacterium that requires cooler (30°C) incubation for many weeks on agar medium enriched with hemin or ferric ammonium citrate to obtain valid growth.1 To secure timely diagnosis, the organism’s slow agar growth warrants immediate tissue culture and biopsy when an immunocompromised patient presents with clinical features of atypical infection of an extremity. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection likely is underreported because of these difficulties in diagnosis.

Management

Although there are no standard guidelines for antibiotic treatment of M haemophilum, the current literature recommends triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifamycin for at least 12 to 24 months.2

Upon clinical suspicion of an atypical Mycobacterium, we recommend a macrolide antibiotic over doxycycline, however, because this class of agents maintains broad coverage while being more specific for atypical mycobacteria. Although an atypical Mycobacterium was suspected early in the presentation in our cases, we discourage immediate use of triple-agent antibiotic therapy until laboratory evidence is procured to minimize antibiotic overuse in patients who do not have a final diagnosis. Single-agent therapy for prolonged treatment is discouraged for atypical mycobacterial infections because of the high risk of antibiotic resistance. Therapy should be tailored to the needs of the individual based on the extent of dissemination of disease and the severity of immunosuppression.1,2

Additionally, underlying disease that results in immunosuppression might necessitate treatment reevaluation (as occurred in our cases) requiring cessation of immunosuppressive drugs, extended careful monitoring, and pharmacotherapeutic readjustment through the course of treatment. The degree to which antibiotics contribute to eradication of M haemophilum is unknown; therefore, it is recommended that long-term antibiotic use and treatment aimed at recovering the immunocompromised state (eg, highly active antiretroviral therapy in a patient with AIDS) be implemented.2

Conclusion

Our 3 cases of M haemophilum infection involved the upper extremities of immunosuppressed patients older than 65 years. This propensity to affect the upper extremities could possibly be due to the lower temperature required for growth of M haemophilum. Initial histopathologic study showed granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrates, yet histopathologic specimens from all 3 patients failed to display positive AFB staining, which delayed the initial antibiotic choice. In all cases, diagnosis was made by tissue culture after swab culture failed to grow the pathogen. Furthermore, the 3 cases took approximately 6 weeks to achieve final identification of the organism. Neither clinical lymphadenopathy nor systemic spread was noted in our patients; immunosuppression was discontinued when possible.

Mycobacterium haemophilum is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening infection that should be suspected in immunocompromised adults who present with atypical cellulitis of the extremities. The ultimate diagnosis often is delayed because the organism grows slowly (as long as 8 weeks) in tissue culture. For that reason, empiric antibiotic treatment, including a macrolide, should be considered in patients with disseminated or severe infection or critical immunosuppression and in those who do not demonstrate improvement in symptoms once immunosuppressants are withheld. A prolonged course of multiple-drug antibiotic therapy has proved to be effective for treating cutaneous infection with M haemophilum.

Infection with Mycobacterium haemophilum, a rare, slow-growing organism, most commonly presents as ulcerating cutaneous lesions and subcutaneous nodules in immunocompromised adults.1 The most common clinical presentation in adults includes cutaneous lesions, nodules, cysts, and papules, with signs and symptoms of erythema, pain, pruritus, and drainage.2 Disseminated disease states of septic arthritis, pulmonary infiltration, and osteomyelitis, though life-threatening, are less common manifestations reported in highly immunocompromised persons.3

Infection with M haemophilum presents a challenge to the dermatology community because it is infrequently suspected and misidentified, resulting in delayed diagnosis. Additionally, M haemophilum is an extremely fastidious organism that requires heme-supplemented culture media and a carefully regulated low temperature for many consecutive weeks to yield valid culture results.1 These features contribute to complications and delays in diagnosis of an already overlooked source of infection.

We discuss the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of 3 unusual cases of cutaneous M haemophilum infection involving the upper arms. The findings in these cases highlight the challenges inherent in diagnosis as well as the obstacles that arise in providing effective, long-term treatment of this infection.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 69-year-old woman with a medical history of a single functioning kidney and moderate psoriasis managed with low-dosage methotrexate presented with an erythematous nonhealing wound on the left forearm that developed after she was scratched by a dog. The pustules, appearing as bright red, tender, warm abscesses, had been present for 3 months and were distributed on the left proximal and distal dorsal forearm (Figure 1A). The patient reported no recent travel, sick contacts, allergies, or new medications.

A shave biopsy was initially obtained. Swab specimens were sent for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial culture following discontinuation of methotrexate. Initial histopathologic analysis revealed aggregates of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells within the dermis, surrounded by infiltrates of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Figure 2), consistent with a dermal noncaseating granulomatosis. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB), periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for pathogenic microorganisms. There was no evidence of vasculitis.

Despite negative special stains, an infectious cause was still suspected. Oral doxycycline monohydrate 100 mg twice daily, oral fluconazole 200 mg daily, and econazole cream 1% were prescribed because of concern for mycobacterial infection and initial growth of Candida parapsilosis in the swab culture.

A punch biopsy also was performed at this time for both repeat histopathologic analysis and tissue culture. Follow-up appointments were scheduled every 2 weeks. Staining by AFB of the repeat histopathologic specimen was negative.

The patient demonstrated symptomatic and aesthetic improvement (Figure 1B) during consecutive regular follow-up appointments while culture results were pending. No lesions appeared above the left elbow and she had no lymphadenopathy. Results of blood chemistry analyses and complete blood cell count throughout follow-up were normal.

The final tissue culture report obtained 7 weeks after initial presentation showed growth of M haemophilum despite a negative smear. The swab culture that initially was taken did not grow pathogenic organisms.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who confirmed that the atypical mycobacterial infection likely was the main source of the cutaneous lesions. She was instructed to continue econazole cream 1% and was given prescriptions for clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily, and rifampin 300 mg twice daily for a total duration of 12 to 18 months. The patient has remained on this triple-drug regimen and demonstrated improvement in the lesions. She has been off methotrexate while on antibiotic therapy.

Patient 2

A 79-year-old man with a medical history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, basal cell carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma presented with a nonhealing, painful, red lesion on the left forearm of 1 week’s duration. Physical examination revealed a violaceous nontender plaque with erosions and desquamation that was initially diagnosed as a carbuncle. The patient reported a similar eruption on the right foot that was successfully treated with silver sulfadiazine by another physician.

Biopsy was performed by the shave method for histologic analysis and tissue culture. Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed because of high suspicion of infection. Histologic findings revealed granulomatous inflammation with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, reported as squamous cell carcinoma. A second opinion confirmed suspicion of an infectious process; the patient remained on doxycycline. During follow-up, the lesion progressed to a 5-cm plaque studded with pustules and satellite papules. Multiple additional tissue cultures were performed over 2 months until “light growth” of M haemophilum was reported.

The patient showed minimal improvement on tetracycline antibiotics. His condition was complicated by a photosensitivity reaction to doxycycline on the left and right forearms, hands, and nose. Consequently, triamcinolone was prescribed, doxycycline was discontinued, and minocycline 100 mg twice daily and ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily were prescribed.

Nine months after initial presentation, the lesions were still present but remarkably improved. The antibiotic regimen was discontinued after 11 months.

Patient 3

A 77-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate and abatacept as well as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with narrowband UVB radiation presented to the emergency department with fever and an inflamed right forearm (Figure 3A). Initial bacterial cultures of the wound and blood were negative.

The patient was treated with vancomycin and discharged on cephalexin once she became afebrile. She was seen at our office the next week for further evaluation. We recommended that she discontinue all immunosuppressant medications. A 4-mm tissue biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and a separate 4-mm punch biopsy for culture were performed while she was taking cephalexin. Histopathologic analysis revealed numerous neutrophilic abscesses; however, Gram, AFB, and fungal stains were negative.

Arm edema and pustules slowly resolved, but the eschar and verrucous plaques continued to slowly progress while the patient was off immunosuppression. She was kept off antibiotics until mycobacterial culture was positive at 4 weeks, at which time she was placed on doxycycline and clarithromycin. Final identification of M haemophilum was made at 6 weeks; consequently, doxycycline was discontinued and she was referred to infectious disease for multidrug therapy. She remained afebrile during the entire 6 weeks until cultures were final.

While immunosuppressants were discontinued and clarithromycin was administered, the plaque changed from an edematous pustular dermatitis to a verrucous crusted plaque. Neither epitrochlear nor axillary lymphadenopathy was noted during the treatment period. The infectious disease specialist prescribed azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin, which produced marked improvement (Figure 3B). The patient has remained off immunosuppressive therapy while on antibiotics.

Comment

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Mycobacterium haemophilum is a rare infectious organism that affects primarily immunocompromised adults but also has been identified in immunocompetent adults and pediatric patients.2 Commonly affected immunosuppressed groups include solid organ transplant recipients, bone marrow transplant recipients, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, and patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The infection typically presents as small violaceous papules and pustules that become painful and erythematous, with progression and draining ulceration in later stages.2 In our cases, all lesions tended to evolve into a verrucous plaque that slowly resolved with antibiotic therapy.

Due to the rarity of this infection, the initial differential diagnosis can include infection with other mycobacteria, Sporothrix, Staphylococcus aureus, and other fungal pathogens. Misdiagnosis is a common obstacle in the treatment of M haemophilum due to its rarity, often negative AFB stains, and slow growth on culture media; therefore, tissue culture is essential to successful diagnosis and management. The natural reservoir of M haemophilum is unknown, but infection has been associated with contaminated water sources.1 In one case (patient 1), symptoms developed after a dog scratch; the other 2 patients were unaware of injury to the skin.Laboratory diagnosis of M haemophilum is inherently difficult and protracted. The species is a highly fastidious and slow-growing Mycobacterium that requires cooler (30°C) incubation for many weeks on agar medium enriched with hemin or ferric ammonium citrate to obtain valid growth.1 To secure timely diagnosis, the organism’s slow agar growth warrants immediate tissue culture and biopsy when an immunocompromised patient presents with clinical features of atypical infection of an extremity. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection likely is underreported because of these difficulties in diagnosis.

Management

Although there are no standard guidelines for antibiotic treatment of M haemophilum, the current literature recommends triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and rifamycin for at least 12 to 24 months.2

Upon clinical suspicion of an atypical Mycobacterium, we recommend a macrolide antibiotic over doxycycline, however, because this class of agents maintains broad coverage while being more specific for atypical mycobacteria. Although an atypical Mycobacterium was suspected early in the presentation in our cases, we discourage immediate use of triple-agent antibiotic therapy until laboratory evidence is procured to minimize antibiotic overuse in patients who do not have a final diagnosis. Single-agent therapy for prolonged treatment is discouraged for atypical mycobacterial infections because of the high risk of antibiotic resistance. Therapy should be tailored to the needs of the individual based on the extent of dissemination of disease and the severity of immunosuppression.1,2

Additionally, underlying disease that results in immunosuppression might necessitate treatment reevaluation (as occurred in our cases) requiring cessation of immunosuppressive drugs, extended careful monitoring, and pharmacotherapeutic readjustment through the course of treatment. The degree to which antibiotics contribute to eradication of M haemophilum is unknown; therefore, it is recommended that long-term antibiotic use and treatment aimed at recovering the immunocompromised state (eg, highly active antiretroviral therapy in a patient with AIDS) be implemented.2

Conclusion

Our 3 cases of M haemophilum infection involved the upper extremities of immunosuppressed patients older than 65 years. This propensity to affect the upper extremities could possibly be due to the lower temperature required for growth of M haemophilum. Initial histopathologic study showed granulomatous and neutrophilic infiltrates, yet histopathologic specimens from all 3 patients failed to display positive AFB staining, which delayed the initial antibiotic choice. In all cases, diagnosis was made by tissue culture after swab culture failed to grow the pathogen. Furthermore, the 3 cases took approximately 6 weeks to achieve final identification of the organism. Neither clinical lymphadenopathy nor systemic spread was noted in our patients; immunosuppression was discontinued when possible.

Mycobacterium haemophilum is an uncommon but potentially life-threatening infection that should be suspected in immunocompromised adults who present with atypical cellulitis of the extremities. The ultimate diagnosis often is delayed because the organism grows slowly (as long as 8 weeks) in tissue culture. For that reason, empiric antibiotic treatment, including a macrolide, should be considered in patients with disseminated or severe infection or critical immunosuppression and in those who do not demonstrate improvement in symptoms once immunosuppressants are withheld. A prolonged course of multiple-drug antibiotic therapy has proved to be effective for treating cutaneous infection with M haemophilum.

- Lindeboom JA, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LE, van Soolingen D, et al. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Mycobacterium haemophilum infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:701-717.

- Tangkosakul T, Hongmanee P, Malathum K. Cutaneous Mycobacterium haemophilum infections in immunocompromised patients in a tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand: under-reported/under-recognized infection. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:E002618.

- Sabeti S, Pourabdollah Tootkaboni M, Abdolahi M, et al. Mycobacterium haemophilum: a report of cutaneous infection in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5(suppl 1):S236.

- Lindeboom JA, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LE, van Soolingen D, et al. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Mycobacterium haemophilum infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:701-717.

- Tangkosakul T, Hongmanee P, Malathum K. Cutaneous Mycobacterium haemophilum infections in immunocompromised patients in a tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand: under-reported/under-recognized infection. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1:E002618.

- Sabeti S, Pourabdollah Tootkaboni M, Abdolahi M, et al. Mycobacterium haemophilum: a report of cutaneous infection in a patient with end-stage renal disease. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5(suppl 1):S236.

Practice Points

- Mycobacterium haemophilum infections typically occur on the extremities of immunosuppressed patients.

- Acid-fast bacilli staining may be negative.

- Mycobacterial cultures may take up to 6 weeks for growth.

- Prolonged triple-antibiotic therapy and lowering of immunosuppression is ideal treatment.

Cutaneous Nocardiosis in an Immunocompromised Patient

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

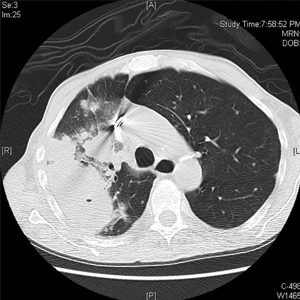

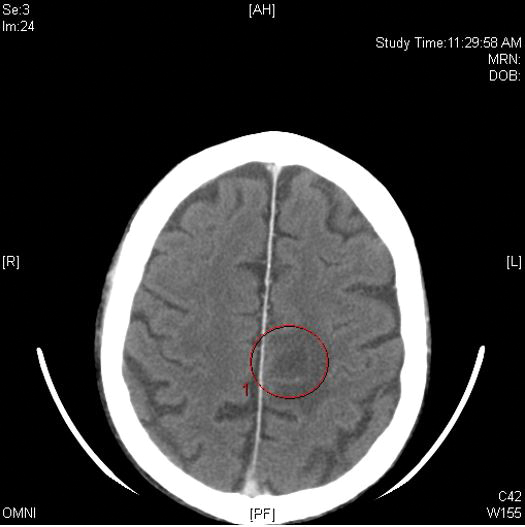

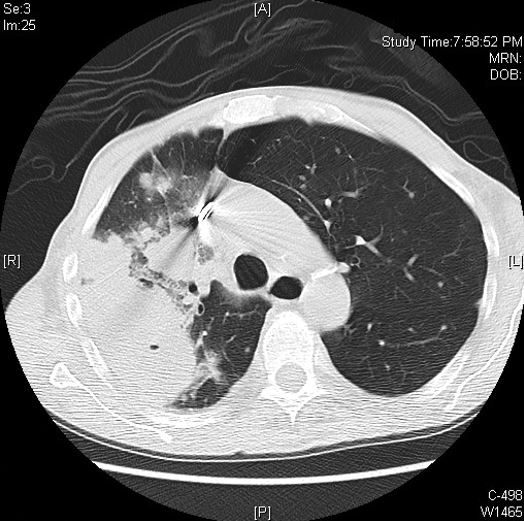

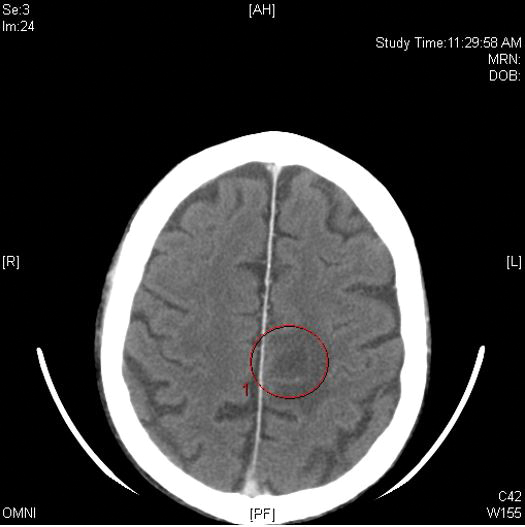

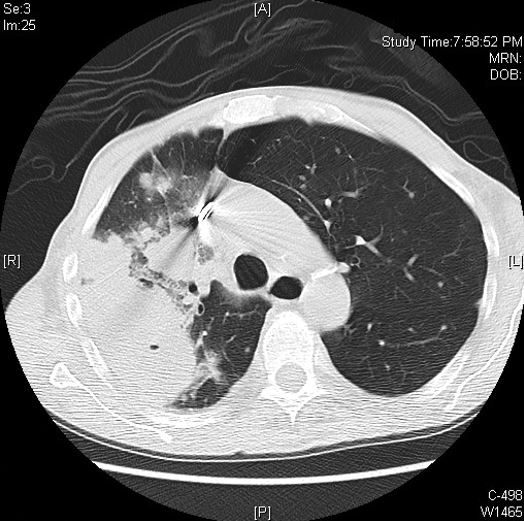

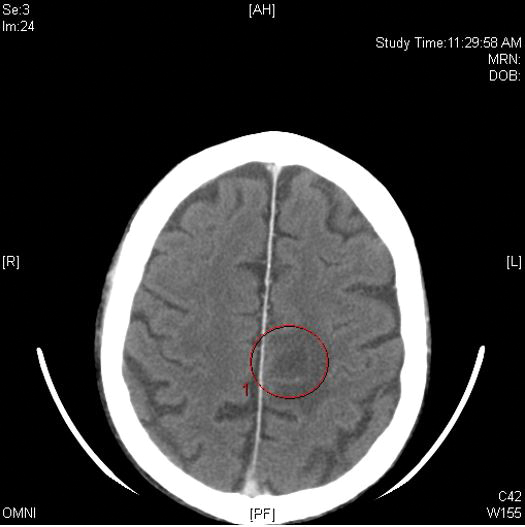

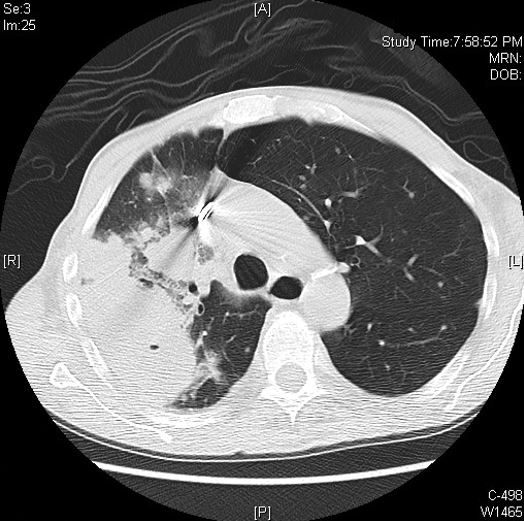

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

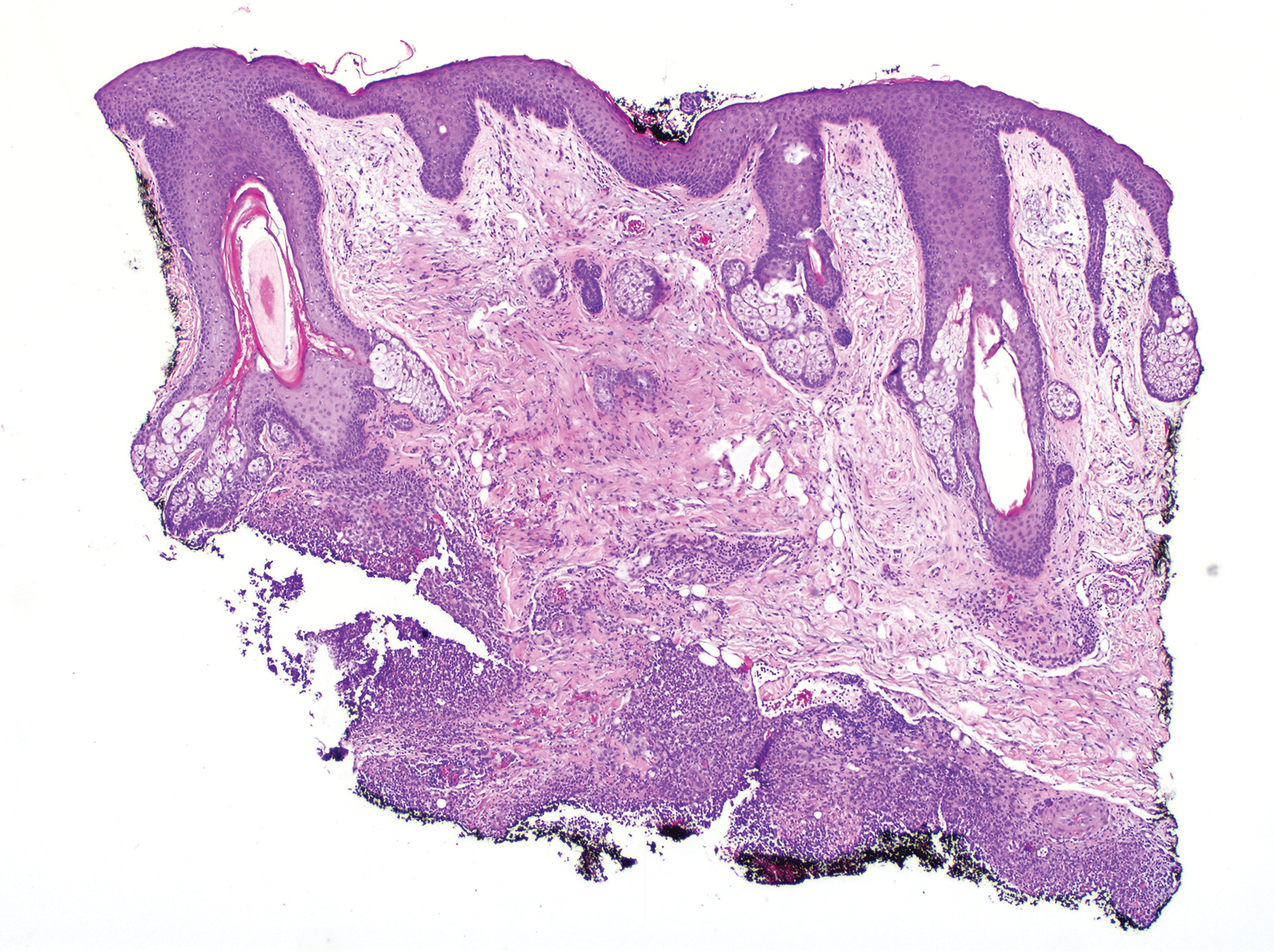

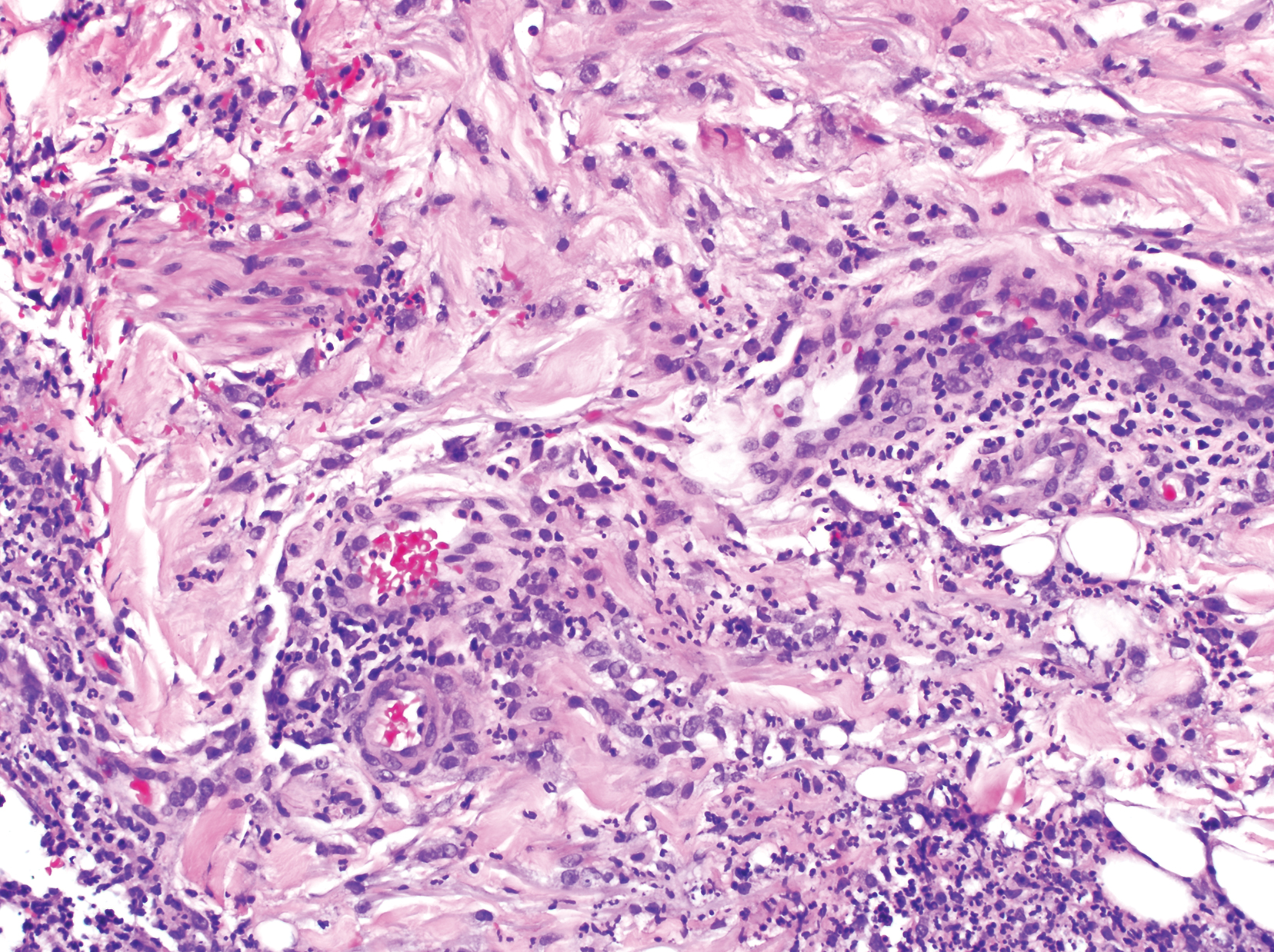

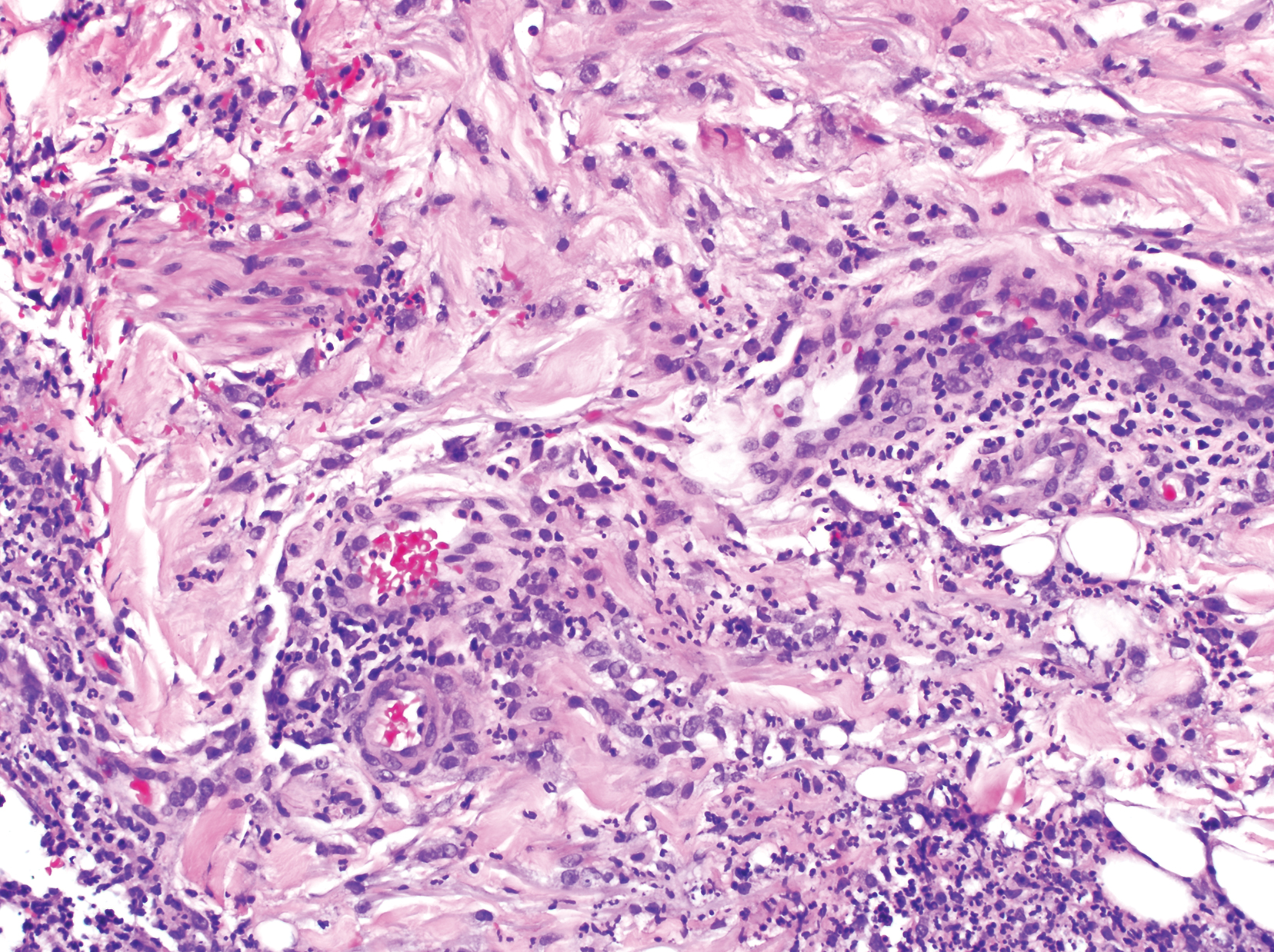

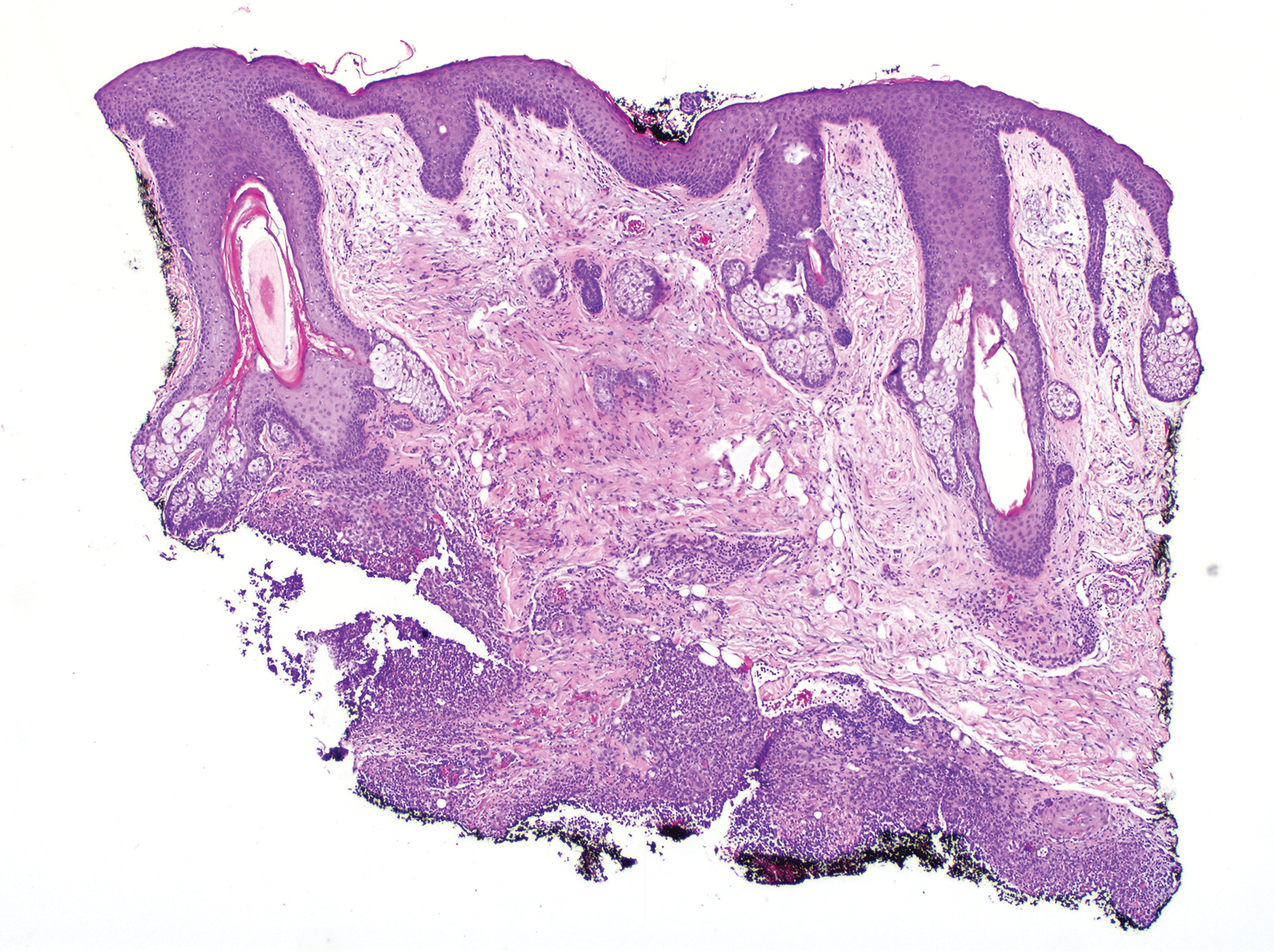

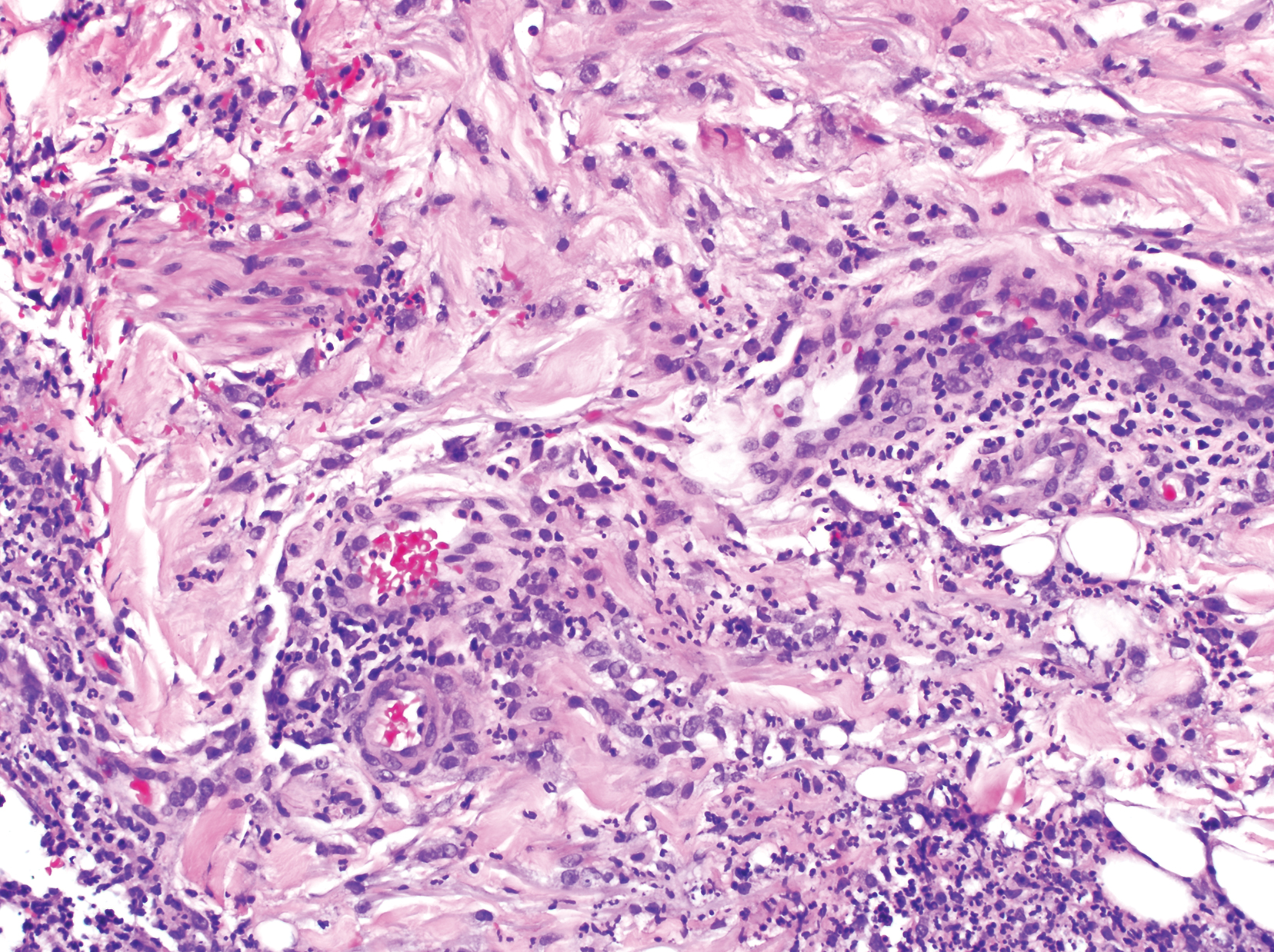

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

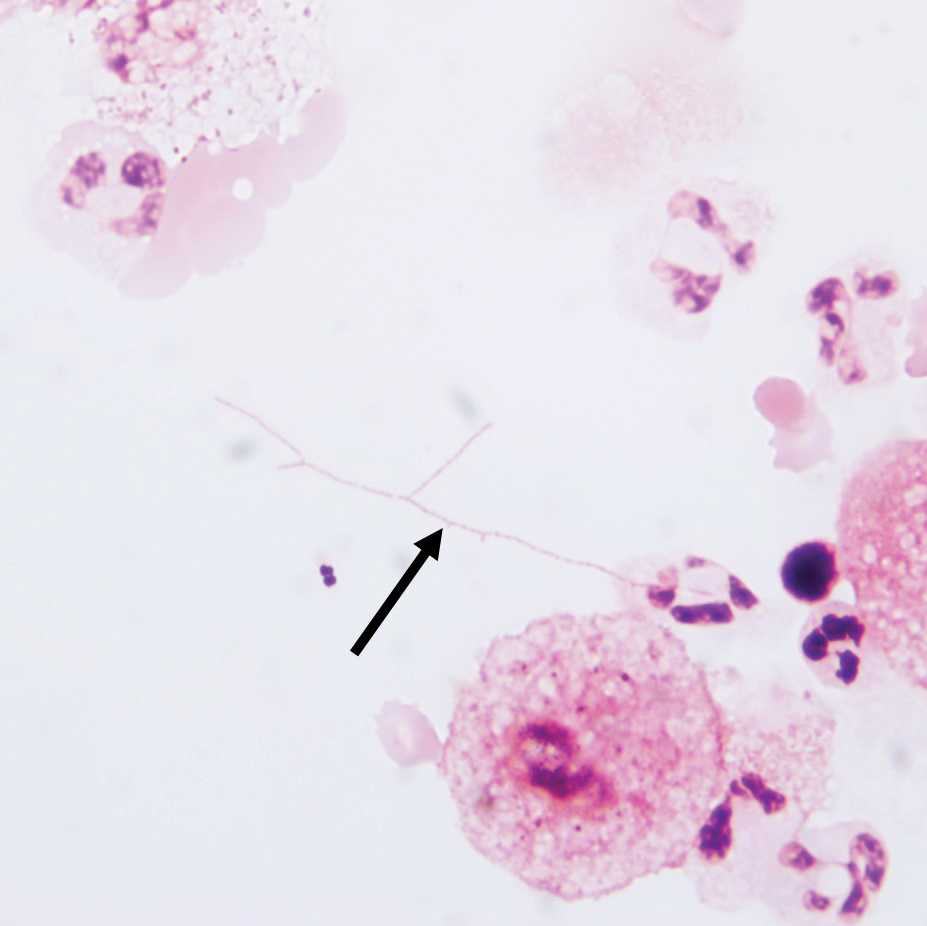

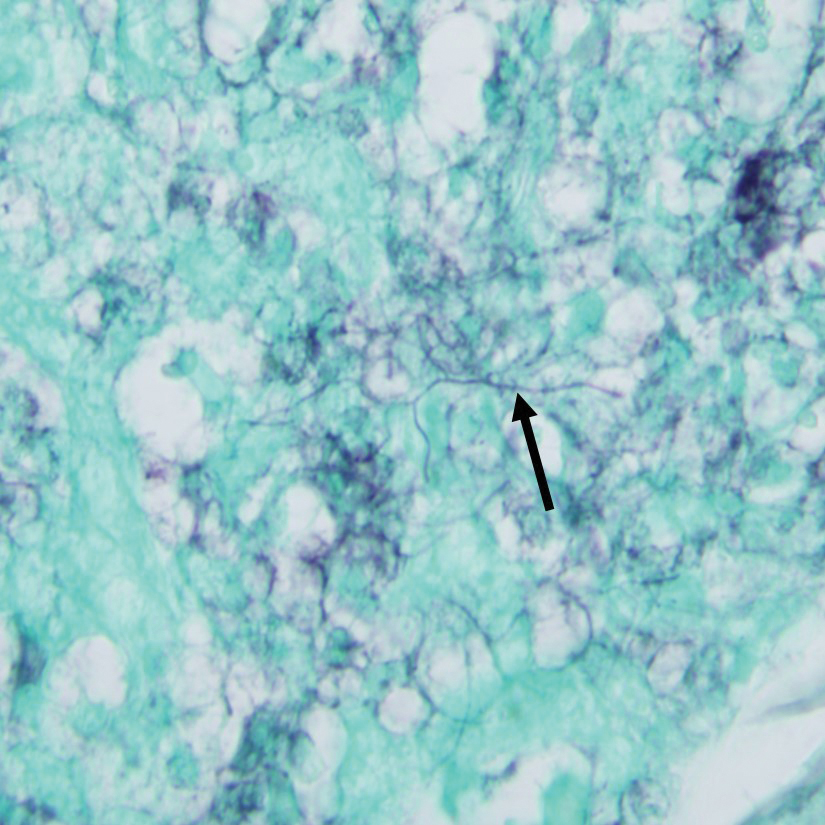

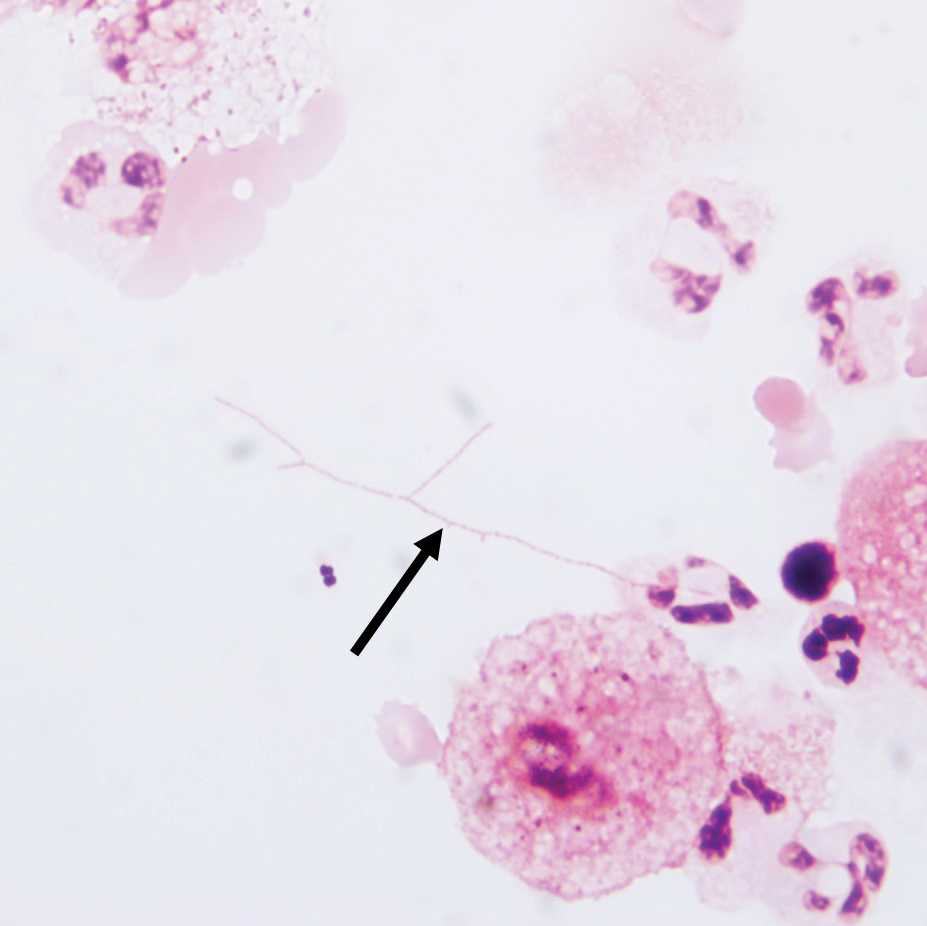

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

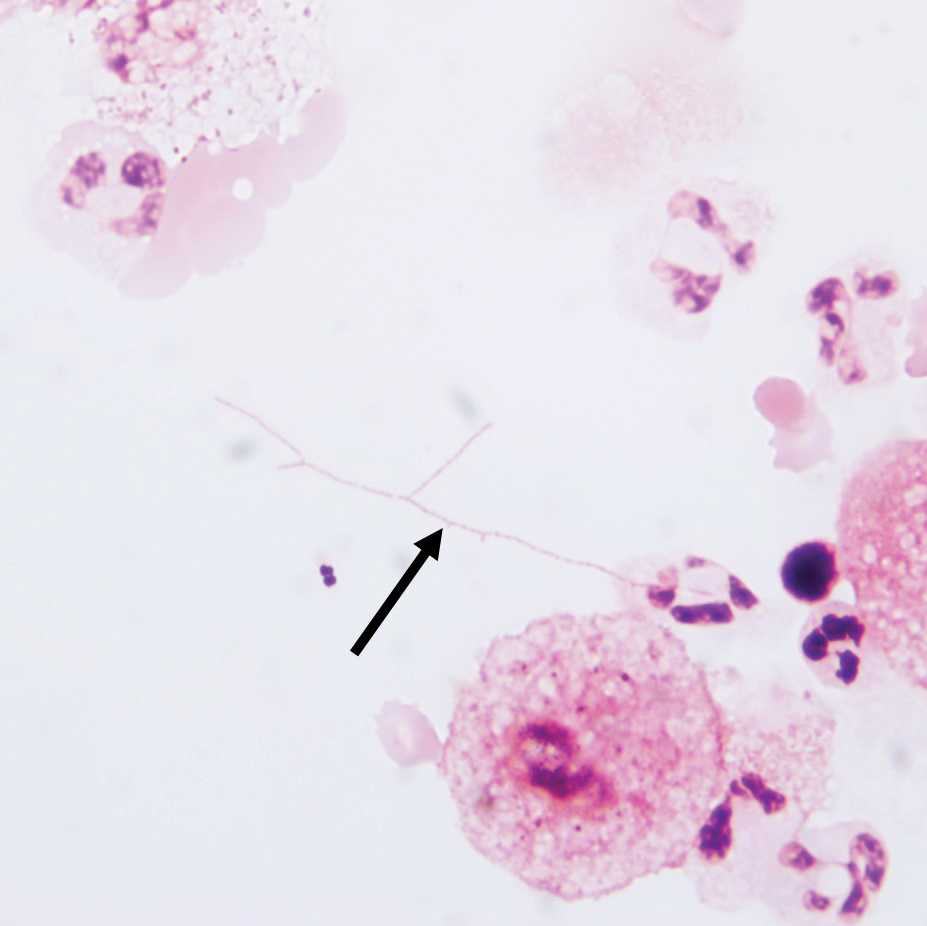

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126:573-581.

- Tadmor T, Welslau M, Hus I. A review of the infection pathogenesis and prophylaxis recommendations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:57-70.

- Williams AM, Baran AM, Meacham PJ, et al. Analysis of the risk of infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:625-632.

- Dias AL, Jain D. Ibrutinib: a new frontier in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2013;11:265-271.

- Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;126:2213-2219.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497-2506.

- Arthurs B, Wunderle K, Hsu M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis related to ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:27-29.

- Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, et al. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872.

- Farid S, AbuSaleh O, Liesman R, et al. Isolated cerebral mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus [published online October 4, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. pii:bcr-2017-221473.

- Okamoto K, Proia LA, Demarais PL. Disseminated cryptococcal disease in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on ibrutinib. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4642831.

- Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016;128:1940-1943.

- Roberts AL, Davidson RM, Freifeld AG, et al. Nocardia arthritidis as a cause of disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. IDCases. 2016;6:68-71.

- Rámila E, Martino R, Santamaría A, et al. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as the initial sign of central nervous system progression of nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1155-1156.

- Phillips WB, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Nocardia choroidal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:694-696.

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

Case Report

A 79-year-old man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who was being treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with a dry cough, ataxia and falls, and vision loss. Physical examination was remarkable for diffuse crackles heard throughout the right lung and bilateral lower extremity weakness. Additionally, he had 4 pink mobile nodules on the left side of the forehead, right side of the chin, left submental area, and left postauricular scalp, which arose approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. The left postauricular lesion had been tender at times and had developed a crust. The cutaneous lesions were all smaller than 2 cm.

The patient had a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin and was under the care of a dermatologist as an outpatient. His dermatologist had described him as an active gardener; he was noted to have healing abrasions on the forearms due to gardening raspberry bushes.

Computed tomography of the head revealed a 14-mm, ring-enhancing lesion in the left paramedian posterior frontal lobe with surrounding white matter vasogenic edema (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest revealed a peripheral mass on the right upper lobe measuring 6.3 cm at its greatest dimension (Figure 2).

Empiric antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam was initiated. A dermatology consultation was placed by the hospitalist service; the consulting dermatologist noted that the patient had subepidermal nodules on the anterior thigh and abdomen, of which the patient had not been aware.

Clinically, the constellation of symptoms was thought to represent an infectious process or less likely metastatic malignancy. Biopsies of the nodule on the right side of the chin were performed and sent for culture and histologic examination. Sections from the anterior right chin showed compact orthokeratosis overlying a slightly spongiotic epidermis (Figure 3). Within the deep dermis, there was a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprising predominantly neutrophils, with occasional eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 4).

Gram stain revealed gram-variable, branching, bacterial organisms morphologically consistent with Nocardia. Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains also highlighted the bacterial organisms (Figure 5). An auramine-O stain was negative for acid-fast microorganisms. After 3 days on a blood agar plate, cultures of a specimen of the chin nodule grew branching filamentous bacterial organisms consistent with Nocardia.

Additionally, morphologically similar microorganisms were identified on a specimen of bronchoalveolar lavage (Figure 6). Blood cultures also returned positive for Nocardia. The specimen was sent to the South Dakota Public Health Laboratory (Pierre, South Dakota), which identified the organism as Nocardia asteroides. Given the findings in skin and the lungs, it was thought that the ring-enhancing lesion in the brain was most likely the result of Nocardia infection.

Antibiotic therapy was switched to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The patient’s mental status deteriorated; vital signs became unstable. He was transferred to the intensive care unit and was found to be hyponatremic, most likely a result of the brain lesion causing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Mental status and clinical condition continued to deteriorate; the patient and his family decided to stop all aggressive care and move to a comfort-only approach. He was transferred to a hospice facility and died shortly thereafter.

Comment

Presentation and Diagnosis

Nocardiosis is an infrequently encountered opportunistic infection that typically targets skin, lungs, and the central nervous system (CNS). Nocardia species characteristically are gram-positive, thin rods that form beaded, right-angle, branching filaments.1 More than 50 Nocardia species have been clinically isolated.2

Definitive diagnosis requires culture. Nocardia grows well on nonselective media, such as blood or Löwenstein-Jensen agar; growth can be enhanced with 10% CO2. Growth can be slow, however, and takes from 48 hours to several weeks. Nocardia typically grows as buff or pigmented, waxy, cerebriform colonies at 3 to 5 days’ incubation.1

Cause of Infection

Nocardia species are commonly found in the environment—soil, plant matter, water, and decomposing organic material—as well as in the gastrointestinal tract and skin of animals. Infection has been reported in cattle, dogs, horses, swine, birds, cats, foxes, and a few other animals.2 A history of exposure, such as gardening or handling animals, should increase suspicion of Nocardia.3 Although infection is classically thought to affect immunocompromised patients, there are case reports of immunocompetent individuals developing disseminated infection.4-7 However, infected immunocompetent individuals typically have localized cutaneous infection, which often includes cellulitis, abscesses, or sporotrichoid patterns.2 Cutaneous infections typically are the result of direct inoculation of the skin through a penetrating injury.8

Disseminated nocardiosis can be caused by numerous species and generally is the result of primary pulmonary infection.9 In these cases, skin disease is present in approximately 10% of patients. Disseminated infection from cutaneous nocardiosis is uncommon; when it does occur, the most common site of dissemination is the CNS, resulting in abscess or cerebritis.10 Therefore, CNS involvement should always be ruled out on diagnosis in immunocompromised patients, even if neurologic symptoms are absent.9 Nearly 80% of patients with disseminated disease are, in fact, immunocompromised.8

Association With CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with profound immunodeficiency caused by quantitative and qualitative aberrations in both innate and adaptive immunity. This perturbation of the immune system predisposes the patient to infection.11,12 Early in the course of CLL, a patient develops neutropenia, which predisposes to bacterial infection; later, the patient develops a sustained B- and T-cell immunodeficiency that predisposes to opportunistic infection.13 Treatment-naïve patients with CLL are commonly diagnosed with respiratory and urinary tract infections.12 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients treated with alemtuzumab or purine analogs have been reported to have the highest risk for major infection.14

Ibrutinib is a commonly used treatment of CLL because it induces apoptosis in B cells, which are abnormal in CLL. Ibrutinib functions by inhibiting the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway, which is essential in B-cell production and maintenance.15 Studies have reported a high rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL patients14,16; salvage ibrutinib therapy has been associated with higher infection risk than primary ibrutinib therapy.16,17 Long-term follow-up studies have shown a decreased rate of infection in ibrutinib-treated CLL after 2 years or longer of treatment, suggesting a reconstitution of normal B cells and humoral immunity with longer ibrutinib therapy.16,17

Many infections have been identified in association with ibrutinib therapy, including invasive aspergillosis, disseminated fusariosis, cerebral mucormycosis, disseminated cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.18-22 Disseminated nocardiosis has been reported in a few patients with CLL, though the treatment they received for CLL varied from case to case.23-25

Identification and Treatment

Clinical and microscopic identification of Nocardia organisms can be exceedingly difficult. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis clinically presents as tumors or nodules that often have a sporotrichoid pattern along the lymphatics. In disease that disseminates to skin, nocardiosis presents as vesiculopustules or abscesses. The biopsy specimen most often shows a dense dermal and subcutaneous infiltrate of neutrophils with abscess formation. Long-standing lesions might show chronic inflammation and nonspecific granulomas.

The appearance of Nocardia organisms is quite subtle on hematoxylin and eosin staining and can be easily missed. Special stains, such as Gram and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains as well as stains for acid-fast organisms, can be invaluable in diagnosing this disease. Biopsy in immunocompromised patients when nocardiosis is part of the differential diagnosis requires extra attention because the organisms can be gram variable and only partially acid fast, as was the case in our patient. Organisms typically will be positive with silver stains.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole typically is the first-line treatment of nocardiosis. Although prognosis is excellent when disease is confined to skin, disseminated infection has 25% mortality.8 Diagnosticians should maintain a high index of suspicion for the disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, because clinical and imaging findings can be nonspecific.

Conclusion

Our patient’s primary risk factor for nocardiosis was his immunocompromised state. In addition, he was an avid gardener, which increased his risk for exposure to the microorganism. Given the timing of disease progression, our case most likely represents primary cutaneous nocardiosis with dissemination to brain, lungs, and other organs, leading to death, and serves as a reminder to dermatologists and pathologists to establish a broad differential diagnosis when dealing with an infectious process in immunocompromised patients.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.

- Forconi F, Moss P. Perturbation of the normal immune system in patients with CLL. Blood. 2015;126:573-581.

- Tadmor T, Welslau M, Hus I. A review of the infection pathogenesis and prophylaxis recommendations in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2018;11:57-70.

- Williams AM, Baran AM, Meacham PJ, et al. Analysis of the risk of infection in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of novel therapies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:625-632.

- Dias AL, Jain D. Ibrutinib: a new frontier in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2013;11:265-271.

- Sun C, Tian X, Lee YS, et al. Partial reconstitution of humoral immunity and fewer infections in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;126:2213-2219.

- Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naïve and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2015;125:2497-2506.

- Arthurs B, Wunderle K, Hsu M, et al. Invasive aspergillosis related to ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;21:27-29.

- Chan TS, Au-Yeung R, Chim CS, et al. Disseminated fusarium infection after ibrutinib therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:871-872.

- Farid S, AbuSaleh O, Liesman R, et al. Isolated cerebral mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus [published online October 4, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. pii:bcr-2017-221473.

- Okamoto K, Proia LA, Demarais PL. Disseminated cryptococcal disease in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia on ibrutinib. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:4642831.

- Ahn IE, Jerussi T, Farooqui M, et al. Atypical Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in previously untreated patients with CLL on single-agent ibrutinib. Blood. 2016;128:1940-1943.

- Roberts AL, Davidson RM, Freifeld AG, et al. Nocardia arthritidis as a cause of disseminated nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. IDCases. 2016;6:68-71.

- Rámila E, Martino R, Santamaría A, et al. Inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone as the initial sign of central nervous system progression of nocardiosis in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 1999;84:1155-1156.

- Phillips WB, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Nocardia choroidal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:694-696.

- Ferri F. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2016: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Grau Pérez M, Casabella Pernas A, de la Rosa Del Rey MDP, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: a pitfall in the diagnosis of skin infection. Infection. 2017;45:927-928.

- Oda R, Sekikawa Y, Hongo I. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient. Intern Med. 2017;56:469-470.

- Jiang Y, Huang A, Fang Q. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3339-3346.

- Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, et al. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- Kim MS, Choi H, Choi KC, et al. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia vinacea: first case in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:812-814.

- Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ. Diagnostic Pathology. Nonneoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

- Ambrosioni J, Lew D, Garbino J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- Bosamiya SS, Vaishnani JB, Momin AM. Sporotrichoid nocardiosis with cutaneous dissemination. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:535.

- Riches JC, Gribben JG. Understanding the immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: potential clinical implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27:207-235.