User login

Third COVID-19 vaccine dose helped some transplant recipients

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

All of those with low titers before the third dose had high titers after receiving the additional shot, but only about 33% of those with negative initial responses had detectable antibodies after the third dose, according to the paper, published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, who keep a COVID-19 vaccine registry, perform antibody tests on all registry subjects and inform them of their results. Registry participants were asked to inform the research team if they received a third dose, and, the research team tracked the immune responses of those who did.

The participants in this case series had low antibody levels and received a third dose of the vaccine on their own between March 20 and May 10 of 2021.

Third dose results

In this cases series – thought to be the first to look at third vaccine shots in this type of patient group – all six of those who had low antibody titers before the third dose had high-positive titers after the third dose.

Of the 24 individuals who had negative antibody titers before the third dose, just 6 had high titers after the third dose.

Two of the participants had low-positive titers, and 16 were negative.

“Several of those boosted very nicely into ranges seen, using these assays, in healthy persons,” said William Werbel, MD, a fellow in infectious disease at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, who helped lead the study. Those with negative levels, even if they responded, tended to have lower titers, he said.

“The benefits at least from an antibody perspective were not the same for everybody and so this is obviously something that needs to be considered when thinking about selecting patients” for a COVID-19 prevention strategy, he said.

Reactions to the vaccine were low to moderate, such as some arm pain and fatigue.

“Showing that something is safe in that special, vulnerable population is important,” Dr. Werbel said. “We’re all wanting to make sure that we’re doing no harm.”

Dr. Werbel noted that there was no pattern in the small series based on the organ transplanted or in the vaccines used. As their third shot, 15 of the patients received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine; 9 received Moderna; and 6 received Pfizer-BioNTech.

Welcome news, but larger studies needed

“To think that a third dose could confer protection for a significant number of people is of course extremely welcome news,” said Christian Larsen, MD, DPhil, professor of surgery in the transplantation division at Emory University, Atlanta, who was not involved in the study. “It’s the easiest conceivable next intervention.”

He added, “We just want studies to confirm that – larger studies.”

Dr. Werbel stressed the importance of looking at third doses in these patients in a more controlled fashion in a randomized trial, to more carefully monitor safety and how patients fare when starting with one type of vaccine and switching to another, for example.

Richard Wender, MD, chair of family medicine and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the findings are a reminder that there is still a lot that is unknown about COVID-19 and vaccination.

“We still don’t know who will or will not benefit from a third dose,” he said. “And our knowledge is evolving. For example, a recent study suggested that people with previous infection and who are vaccinated may have better and longer protection than people with vaccination alone. We’re still learning.”

He added that specialists, not primary care clinicians, should be relied upon to respond to this emerging vaccination data. Primary care doctors are very busy in other ways – such as in getting children caught up on vaccinations and helping adults return to managing their chronic diseases, Dr. Wender noted.

“Their focus needs to be on helping to overcome hesitancy, mistrust, lack of information, or antivaccination sentiment to help more people feel comfortable being vaccinated – this is a lot of work and needs constant focus. In short, primary care clinicians need to focus chiefly on the unvaccinated,” he said.

“Monitoring immunization recommendations for unique at-risk populations should be the chief responsibility of teams providing subspecialty care, [such as for] transplant patients, people with chronic kidney disease, cancer patients, and people with other chronic illnesses. This will allow primary care clinicians to tackle their many complex jobs.”

Possible solutions for those with low antibody responses

Dr. Larsen said that those with ongoing low antibody responses might still have other immune responses, such as a T-cell response. Such patients also could consider changing their vaccine type, he said.

“At the more significant intervention level, there may be circumstances where one could change the immunosuppressive drugs in a controlled way that might allow a better response,” suggested Dr. Larsen. “That’s obviously going to be something that requires a lot more thought and careful study.”

Dr. Werbel said that other options might need to be considered for those having no response following a third dose. One possibility is trying a vaccine with an adjuvant, such as the Novavax version, which might be more widely available soon.

“If you’re given a third dose of a very immunogenic vaccine – something that should work – and you just have no antibody development, it seems relatively unlikely that doing the same thing again is going to help you from that perspective, and for all we know might expose you to more risk,” Dr. Werbel noted.

Participant details

None of the 30 patients were thought to have ever had COVID-19. On average, patients had received their transplant 4.5 years before their original vaccination. In 25 patients, maintenance immunosuppression included tacrolimus or cyclosporine along with mycophenolate. Corticosteroids were also used for 24 patients, sirolimus was used for one patient, and belatacept was used for another patient.

Fifty-seven percent of patients had received the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine originally, and 43% the Moderna vaccine. Most of the patients were kidney recipients, with two heart, three liver, one lung, one pancreas and one kidney-pancreas.

Dr. Werbel, Dr. Wender, and Dr. Larsen reported no relevant disclosures.

Infections in infants: An update

Converge 2021 session

Febrile Infant Update

Presenter

Russell J. McCulloh, MD

Session summary

Infections in infants aged younger than 90 days have been the subject of intense study in pediatric hospital medicine for many years. With the guidance of our talented presenter Dr. Russell McCulloh of Children’s Hospital & Medical Center in Omaha, Neb., the audience explored the historical perspective and evolution of this scientific question, including successes, special situations, newer screening tests, and description of cutting-edge scoring tools and platforms.

The challenge – Tens of thousands of infants present for care in the setting of fever each year. We know that our physical exam and history-taking skills are unlikely to be helpful in risk stratification. We have been guided by the desire to separate serious bacterial infection (SBI: bone infection, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, enteritis) from invasive bacterial infection (IBI: meningitis and bacteremia). Data has shown that no test is 100% sensitive or specific, therefore we have to balance risk of disease to cost and invasiveness of tests. Important questions include whether to test and how to stratify by age, who to admit, and who to provide antibiotics.

The wins and exceptions – Fortunately, the early Boston, Philadelphia, and Rochester criteria set the stage for safely reducing testing. The current American College of Emergency Physicians guidelines for infants aged 29-90 days allows for lumbar puncture to be optional knowing that a look back using prior criteria identified no cases of meningitis in the low risk group. Similarly, in low-risk infants aged less that 29 days in nearly 4,000 cases there were just 2 infants with meningitis. Universal screening of moms for Group B Streptococcus with delivery of antibiotics in appropriate cases has dramatically decreased incidence of SBI. The Hib and pneumovax vaccines have likewise decreased incidence of SBI. Exceptions persist, including knowledge that infants with herpes simplex virus disease will not have fever in 50% of cases and that risk of HSV transmission is highest (25%-60% transmission) in mothers with primary disease. Given risk of HSV CNS disease after 1 week of age, in any high-risk infant less than 21 days, the mantra remains to test and treat.

The cutting edge – Thanks to ongoing research, we now have the PECARN and REVISE study groups to further aid decision-making. With PECARN we know that SBI in infants is extremely unlikely (negative predictive value, 99.7%) with a negative urinalysis , absolute neutrophil count less than 4,090, and procalcitonin less than 1.71. REVISE has revealed that infants with positive viral testing are unlikely to have SBI (7%-12%), particularly with influenza and RSV disease. Procalcitonin has also recently been shown to be an effective tool to rule out disease with the highest negative predictive value among available inflammatory markers. The just-published Aronson rule identifies a scoring system for IBI (using age less than 21 days/1pt; temp 38-38.4° C/2pt; >38.5° C/4pt; abnormal urinalysis/3pt; and absolute neutrophil count >5185/2pt) where any score greater than2 provides a sensitivity of 98.8% and NPV in validation studies of 99.4%. Likewise, multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of spinal fluid has allowed for additional insight in pretreated cases and has helped us to remove antibiotic treatment from cases where parechovirus and enterovirus are positive because of the low risk for concomitant bacterial meningitis. As we await the release of revised national American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, it is safe to say great progress has been made in the care of young febrile infants with shorter length of stay and fewer tests for all.

Key takeaways

- Numerous screening tests, rules, and scoring tools have been created to improve identification of infants with IBI, a low-frequency, high-morbidity event. The most recent with negative predictive values of 99.7% and 99.4% are the PECARN and Aronson scoring tools.

- Recent studies of the febrile infant population indicate that the odds of UTI or bacteremia in infants with respiratory symptoms is low, particularly for RSV and influenza.

- Among newer tests developed, a negative procalcitonin has the highest negative predictive value.

- Viral pathogens identified on cerebrospinal fluid molecular testing can be helpful in pretreated cases and indicative of low likelihood of bacterial meningitis allowing for observation off of antibiotics.

Dr. King is a hospitalist, associate director for medical education and associate program director for the pediatrics residency program at Children’s Minnesota in Minneapolis. She has shared some of her resident teaching, presentation skills, and peer-coaching work on a national level.

Converge 2021 session

Febrile Infant Update

Presenter

Russell J. McCulloh, MD

Session summary

Infections in infants aged younger than 90 days have been the subject of intense study in pediatric hospital medicine for many years. With the guidance of our talented presenter Dr. Russell McCulloh of Children’s Hospital & Medical Center in Omaha, Neb., the audience explored the historical perspective and evolution of this scientific question, including successes, special situations, newer screening tests, and description of cutting-edge scoring tools and platforms.

The challenge – Tens of thousands of infants present for care in the setting of fever each year. We know that our physical exam and history-taking skills are unlikely to be helpful in risk stratification. We have been guided by the desire to separate serious bacterial infection (SBI: bone infection, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, enteritis) from invasive bacterial infection (IBI: meningitis and bacteremia). Data has shown that no test is 100% sensitive or specific, therefore we have to balance risk of disease to cost and invasiveness of tests. Important questions include whether to test and how to stratify by age, who to admit, and who to provide antibiotics.

The wins and exceptions – Fortunately, the early Boston, Philadelphia, and Rochester criteria set the stage for safely reducing testing. The current American College of Emergency Physicians guidelines for infants aged 29-90 days allows for lumbar puncture to be optional knowing that a look back using prior criteria identified no cases of meningitis in the low risk group. Similarly, in low-risk infants aged less that 29 days in nearly 4,000 cases there were just 2 infants with meningitis. Universal screening of moms for Group B Streptococcus with delivery of antibiotics in appropriate cases has dramatically decreased incidence of SBI. The Hib and pneumovax vaccines have likewise decreased incidence of SBI. Exceptions persist, including knowledge that infants with herpes simplex virus disease will not have fever in 50% of cases and that risk of HSV transmission is highest (25%-60% transmission) in mothers with primary disease. Given risk of HSV CNS disease after 1 week of age, in any high-risk infant less than 21 days, the mantra remains to test and treat.

The cutting edge – Thanks to ongoing research, we now have the PECARN and REVISE study groups to further aid decision-making. With PECARN we know that SBI in infants is extremely unlikely (negative predictive value, 99.7%) with a negative urinalysis , absolute neutrophil count less than 4,090, and procalcitonin less than 1.71. REVISE has revealed that infants with positive viral testing are unlikely to have SBI (7%-12%), particularly with influenza and RSV disease. Procalcitonin has also recently been shown to be an effective tool to rule out disease with the highest negative predictive value among available inflammatory markers. The just-published Aronson rule identifies a scoring system for IBI (using age less than 21 days/1pt; temp 38-38.4° C/2pt; >38.5° C/4pt; abnormal urinalysis/3pt; and absolute neutrophil count >5185/2pt) where any score greater than2 provides a sensitivity of 98.8% and NPV in validation studies of 99.4%. Likewise, multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of spinal fluid has allowed for additional insight in pretreated cases and has helped us to remove antibiotic treatment from cases where parechovirus and enterovirus are positive because of the low risk for concomitant bacterial meningitis. As we await the release of revised national American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, it is safe to say great progress has been made in the care of young febrile infants with shorter length of stay and fewer tests for all.

Key takeaways

- Numerous screening tests, rules, and scoring tools have been created to improve identification of infants with IBI, a low-frequency, high-morbidity event. The most recent with negative predictive values of 99.7% and 99.4% are the PECARN and Aronson scoring tools.

- Recent studies of the febrile infant population indicate that the odds of UTI or bacteremia in infants with respiratory symptoms is low, particularly for RSV and influenza.

- Among newer tests developed, a negative procalcitonin has the highest negative predictive value.

- Viral pathogens identified on cerebrospinal fluid molecular testing can be helpful in pretreated cases and indicative of low likelihood of bacterial meningitis allowing for observation off of antibiotics.

Dr. King is a hospitalist, associate director for medical education and associate program director for the pediatrics residency program at Children’s Minnesota in Minneapolis. She has shared some of her resident teaching, presentation skills, and peer-coaching work on a national level.

Converge 2021 session

Febrile Infant Update

Presenter

Russell J. McCulloh, MD

Session summary

Infections in infants aged younger than 90 days have been the subject of intense study in pediatric hospital medicine for many years. With the guidance of our talented presenter Dr. Russell McCulloh of Children’s Hospital & Medical Center in Omaha, Neb., the audience explored the historical perspective and evolution of this scientific question, including successes, special situations, newer screening tests, and description of cutting-edge scoring tools and platforms.

The challenge – Tens of thousands of infants present for care in the setting of fever each year. We know that our physical exam and history-taking skills are unlikely to be helpful in risk stratification. We have been guided by the desire to separate serious bacterial infection (SBI: bone infection, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, enteritis) from invasive bacterial infection (IBI: meningitis and bacteremia). Data has shown that no test is 100% sensitive or specific, therefore we have to balance risk of disease to cost and invasiveness of tests. Important questions include whether to test and how to stratify by age, who to admit, and who to provide antibiotics.

The wins and exceptions – Fortunately, the early Boston, Philadelphia, and Rochester criteria set the stage for safely reducing testing. The current American College of Emergency Physicians guidelines for infants aged 29-90 days allows for lumbar puncture to be optional knowing that a look back using prior criteria identified no cases of meningitis in the low risk group. Similarly, in low-risk infants aged less that 29 days in nearly 4,000 cases there were just 2 infants with meningitis. Universal screening of moms for Group B Streptococcus with delivery of antibiotics in appropriate cases has dramatically decreased incidence of SBI. The Hib and pneumovax vaccines have likewise decreased incidence of SBI. Exceptions persist, including knowledge that infants with herpes simplex virus disease will not have fever in 50% of cases and that risk of HSV transmission is highest (25%-60% transmission) in mothers with primary disease. Given risk of HSV CNS disease after 1 week of age, in any high-risk infant less than 21 days, the mantra remains to test and treat.

The cutting edge – Thanks to ongoing research, we now have the PECARN and REVISE study groups to further aid decision-making. With PECARN we know that SBI in infants is extremely unlikely (negative predictive value, 99.7%) with a negative urinalysis , absolute neutrophil count less than 4,090, and procalcitonin less than 1.71. REVISE has revealed that infants with positive viral testing are unlikely to have SBI (7%-12%), particularly with influenza and RSV disease. Procalcitonin has also recently been shown to be an effective tool to rule out disease with the highest negative predictive value among available inflammatory markers. The just-published Aronson rule identifies a scoring system for IBI (using age less than 21 days/1pt; temp 38-38.4° C/2pt; >38.5° C/4pt; abnormal urinalysis/3pt; and absolute neutrophil count >5185/2pt) where any score greater than2 provides a sensitivity of 98.8% and NPV in validation studies of 99.4%. Likewise, multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing of spinal fluid has allowed for additional insight in pretreated cases and has helped us to remove antibiotic treatment from cases where parechovirus and enterovirus are positive because of the low risk for concomitant bacterial meningitis. As we await the release of revised national American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines, it is safe to say great progress has been made in the care of young febrile infants with shorter length of stay and fewer tests for all.

Key takeaways

- Numerous screening tests, rules, and scoring tools have been created to improve identification of infants with IBI, a low-frequency, high-morbidity event. The most recent with negative predictive values of 99.7% and 99.4% are the PECARN and Aronson scoring tools.

- Recent studies of the febrile infant population indicate that the odds of UTI or bacteremia in infants with respiratory symptoms is low, particularly for RSV and influenza.

- Among newer tests developed, a negative procalcitonin has the highest negative predictive value.

- Viral pathogens identified on cerebrospinal fluid molecular testing can be helpful in pretreated cases and indicative of low likelihood of bacterial meningitis allowing for observation off of antibiotics.

Dr. King is a hospitalist, associate director for medical education and associate program director for the pediatrics residency program at Children’s Minnesota in Minneapolis. She has shared some of her resident teaching, presentation skills, and peer-coaching work on a national level.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

COVID-19 death toll higher for international medical graduates

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.

To see whether their vulnerability affected their risk for death, Dr. Dinakarpandian and colleagues collected data from Nov. 23, 2020, from three sources of information regarding deaths among physicians: MedPage Today, which used investigative and voluntary reporting; Medscape, which used voluntary reporting of verifiable information; and a collaboration of The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, which used investigative reporting.

The Medscape project was launched on April 1, 2020. The MedPage Today and The Guardian/Kaiser Health News projects were launched on April 8, 2020.

Dr. Verghese and colleagues researched obituaries and news articles referenced by the three projects to verify their data. They used DocInfo to ascertain the deceased physicians’ medical schools.

After eliminating duplications from the lists, the researchers counted 132 physician deaths in 28 states. Of these, 59 physicians had graduated from medical schools outside the United States, a death toll 1.8 times higher than the proportion of IMGs among U.S. physicians (95% confidence interval, 1.52-2.21; P < .001).

New York, New Jersey, and Florida accounted for 66% of the deaths among IMGs but for only 45% of the deaths among U.S. medical school graduates.

Within each state, the proportion of IMGs among deceased physicians was not statistically different from their proportion among physicians in those states, with the exception of New York.

Two-thirds of the physicians’ deaths occurred in states where IMGs make up a larger proportion of physicians than in the nation as a whole. In these states, the incidence of COVID-19 was high at the start of the pandemic.

In New York, IMGs accounted for 60% of physician deaths, which was 1.62 times higher (95% CI, 1.26-2.09; P = .005) than the 37% among New York physicians overall.

Physicians who were trained abroad frequently can’t get into the most prestigious residency programs or into the highest paid specialties and are more likely to serve in primary care, Dr. Verghese said. Overall, 60% of the physicians who died of COVID-19 worked in primary care.

IMGs often staff hospitals serving low-income communities and communities of color, which were hardest hit by the pandemic and where personal protective equipment was hard to obtain, said Dr. Verghese.

In addition to these risks, IMGs sometimes endure racism, said Dr. Verghese, who obtained his medical degree at Madras Medical College, Chennai, India. “We’ve actually seen in the COVID era, in keeping with the sort of political tone that was set in Washington, that there’s been a lot more abuses of both foreign physicians and foreign looking physicians – even if they’re not foreign trained – and nurses by patients who have been given license. And I want to acknowledge the heroism of all these physicians.”

The study was partially funded by the Presence Center at Stanford. Dr. Verghese is a regular contributor to Medscape. He served on the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, serves as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Leigh Bureau, and receives royalties from Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.

To see whether their vulnerability affected their risk for death, Dr. Dinakarpandian and colleagues collected data from Nov. 23, 2020, from three sources of information regarding deaths among physicians: MedPage Today, which used investigative and voluntary reporting; Medscape, which used voluntary reporting of verifiable information; and a collaboration of The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, which used investigative reporting.

The Medscape project was launched on April 1, 2020. The MedPage Today and The Guardian/Kaiser Health News projects were launched on April 8, 2020.

Dr. Verghese and colleagues researched obituaries and news articles referenced by the three projects to verify their data. They used DocInfo to ascertain the deceased physicians’ medical schools.

After eliminating duplications from the lists, the researchers counted 132 physician deaths in 28 states. Of these, 59 physicians had graduated from medical schools outside the United States, a death toll 1.8 times higher than the proportion of IMGs among U.S. physicians (95% confidence interval, 1.52-2.21; P < .001).

New York, New Jersey, and Florida accounted for 66% of the deaths among IMGs but for only 45% of the deaths among U.S. medical school graduates.

Within each state, the proportion of IMGs among deceased physicians was not statistically different from their proportion among physicians in those states, with the exception of New York.

Two-thirds of the physicians’ deaths occurred in states where IMGs make up a larger proportion of physicians than in the nation as a whole. In these states, the incidence of COVID-19 was high at the start of the pandemic.

In New York, IMGs accounted for 60% of physician deaths, which was 1.62 times higher (95% CI, 1.26-2.09; P = .005) than the 37% among New York physicians overall.

Physicians who were trained abroad frequently can’t get into the most prestigious residency programs or into the highest paid specialties and are more likely to serve in primary care, Dr. Verghese said. Overall, 60% of the physicians who died of COVID-19 worked in primary care.

IMGs often staff hospitals serving low-income communities and communities of color, which were hardest hit by the pandemic and where personal protective equipment was hard to obtain, said Dr. Verghese.

In addition to these risks, IMGs sometimes endure racism, said Dr. Verghese, who obtained his medical degree at Madras Medical College, Chennai, India. “We’ve actually seen in the COVID era, in keeping with the sort of political tone that was set in Washington, that there’s been a lot more abuses of both foreign physicians and foreign looking physicians – even if they’re not foreign trained – and nurses by patients who have been given license. And I want to acknowledge the heroism of all these physicians.”

The study was partially funded by the Presence Center at Stanford. Dr. Verghese is a regular contributor to Medscape. He served on the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, serves as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Leigh Bureau, and receives royalties from Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers report.

“I’ve always felt that international medical graduates [IMGs] in America are largely invisible,” said senior author Abraham Verghese, MD, MFA, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. “Everyone is aware that there are foreign doctors, but very few are aware of how many there are and also how vital they are to providing health care in America.”

IMGs made up 25% of all U.S. physicians in 2020 but accounted for 45% of those whose deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 through Nov. 23, 2020, Deendayal Dinakarpandian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues report in JAMA Network Open.

IMGs are more likely to work in places where the incidence of COVID-19 is high and in facilities with fewer resources, Dr. Verghese said in an interview. “So, it’s not surprising that they were on the front lines when this thing came along,” he said.

To see whether their vulnerability affected their risk for death, Dr. Dinakarpandian and colleagues collected data from Nov. 23, 2020, from three sources of information regarding deaths among physicians: MedPage Today, which used investigative and voluntary reporting; Medscape, which used voluntary reporting of verifiable information; and a collaboration of The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, which used investigative reporting.

The Medscape project was launched on April 1, 2020. The MedPage Today and The Guardian/Kaiser Health News projects were launched on April 8, 2020.

Dr. Verghese and colleagues researched obituaries and news articles referenced by the three projects to verify their data. They used DocInfo to ascertain the deceased physicians’ medical schools.

After eliminating duplications from the lists, the researchers counted 132 physician deaths in 28 states. Of these, 59 physicians had graduated from medical schools outside the United States, a death toll 1.8 times higher than the proportion of IMGs among U.S. physicians (95% confidence interval, 1.52-2.21; P < .001).

New York, New Jersey, and Florida accounted for 66% of the deaths among IMGs but for only 45% of the deaths among U.S. medical school graduates.

Within each state, the proportion of IMGs among deceased physicians was not statistically different from their proportion among physicians in those states, with the exception of New York.

Two-thirds of the physicians’ deaths occurred in states where IMGs make up a larger proportion of physicians than in the nation as a whole. In these states, the incidence of COVID-19 was high at the start of the pandemic.

In New York, IMGs accounted for 60% of physician deaths, which was 1.62 times higher (95% CI, 1.26-2.09; P = .005) than the 37% among New York physicians overall.

Physicians who were trained abroad frequently can’t get into the most prestigious residency programs or into the highest paid specialties and are more likely to serve in primary care, Dr. Verghese said. Overall, 60% of the physicians who died of COVID-19 worked in primary care.

IMGs often staff hospitals serving low-income communities and communities of color, which were hardest hit by the pandemic and where personal protective equipment was hard to obtain, said Dr. Verghese.

In addition to these risks, IMGs sometimes endure racism, said Dr. Verghese, who obtained his medical degree at Madras Medical College, Chennai, India. “We’ve actually seen in the COVID era, in keeping with the sort of political tone that was set in Washington, that there’s been a lot more abuses of both foreign physicians and foreign looking physicians – even if they’re not foreign trained – and nurses by patients who have been given license. And I want to acknowledge the heroism of all these physicians.”

The study was partially funded by the Presence Center at Stanford. Dr. Verghese is a regular contributor to Medscape. He served on the advisory board for Gilead Sciences, serves as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Leigh Bureau, and receives royalties from Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More evidence links COVID vaccines to rare cases of myocarditis in youth

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert reported on June 10, detailing data on cases of myocarditis and pericarditis detected through a government safety system.

The side effect seems to be more common in teen boys and young men than in older adults and women and may occur in 16 cases for every 1 million people who got a second dose, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, deputy director of the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office, who presented information on the cases at a meeting of an expert panel that advises the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Telltale symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, and fever.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious diseases specialist from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., thinks certain characteristics are pointing toward a “rare, but real” signal. First, the events are clustering, occurring within days of vaccination. Second, they tend to be more common in males and younger people. Third, he says, the number of events is above the so-called “background rate” – the cases that could be expected in this age group even without vaccination.

“I don’t think we’re quite there yet. We haven’t tied a ribbon around it, but I think the data are trending in that direction,” he said.

The issue of myocarditis weighed heavily on the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee’s considerations of what kind and how much data might be needed to green light use of a vaccine for COVID in children.

Because the rates of hospitalization for COVID are low in kids, some felt that the FDA should require at least a year of study of the vaccines in clinical trials, the amount of data typically required for full approval, instead of the 2 months currently required for emergency use authorization. Others wondered whether the risks of vaccination – as low as they are – might outweigh the benefits in this age group.

“I don’t really see this as an emergency in children,” said committee member Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, the director of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kurilla, however, did say he thought having an expanded access program for children at high risk might make sense.

Most of the young adults who experienced myocarditis recovered quickly, though three needed intensive care and rehabilitation after their episodes. Among cases with known outcomes, 81% got better and 19% still have ongoing symptoms.

Adverse events reports

The data on myocarditis come from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, or VAERS, a database of health problems reported after vaccination. This reporting system, open to anyone, has benefits and limits. It gives the CDC and FDA the ability to rapidly detect potential safety issues, and it is large enough that it can detect rare events, something that’s beyond the power of even large clinical trials.

But it is observational, so that there’s no way to know if problems reported were caused by the vaccines or a coincidence.

But because VAERS works on an honor system, it can also be spammed, and it carries the bias of the person who’s doing the reporting, from clinicians to average patients. For that reason, Dr. Shimabukuro said they are actively investigating and confirming each report they get.

Out of more than 12 million doses administered to youth ages 16-24, the CDC says it has 275 reports of heart inflammation following vaccination in this age group. The CDC has analyzed a total 475 cases of myocarditis after vaccination in people under age 30 that were reported to VAERS.

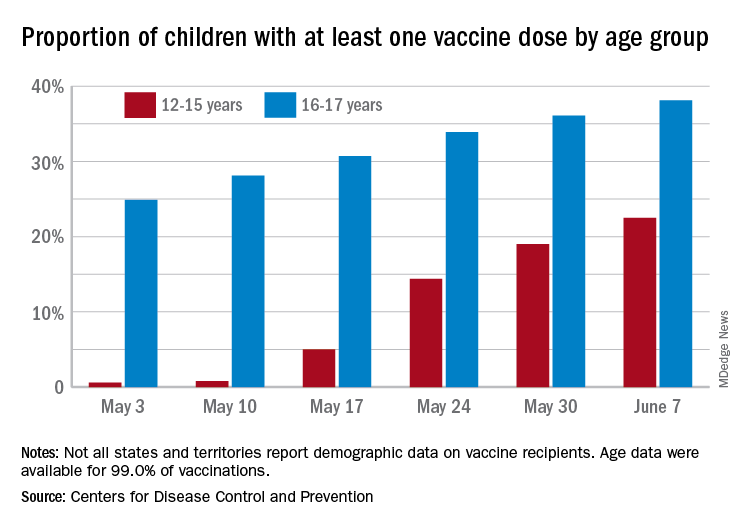

The vaccines linked to the events are the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna. The only vaccines currently authorized for use in adolescents are made by Pfizer. Because the Pfizer vaccine was authorized for use in kids as young as 12 last month, there’s not yet enough data to draw conclusions about the risk of myocarditis in kids ages 12-15.

Younger age groups have only received about 9% of the total doses of the vaccine so far, but they represent about 50% of the myocarditis cases reported after vaccination. “We clearly have an imbalance there,” Dr. Shimabukuro said.

The number of events in this age group appears to be above the rate that would be expected for these age groups without vaccines in the picture, he said, explaining that the number of events are in line with similar adverse events seen in young people in Israel and reported by the Department of Defense. Israel found the incidence of myocarditis after vaccination was 50 cases per million for men ages 18-30.

More study needed

Another system tracking adverse events through hospitals, the Vaccine Safety Datalink, didn’t show reports of heart inflammation above numbers that are normally seen in the population, but it did show that inflammation was more likely after a second dose of the vaccine.

“Should this be included in informed consent?” asked Cody Meissner, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Tufts University, Boston, and a member of the FDA committee.

“I think it’s hard to deny there seem to be some [events that seem] to be occurring in terms of myocarditis,” he said.

Dr. Meissner said later in the committee’s discussion that his own hospital had recently admitted a 12-year-old boy who developed heart swelling 2 days after the second dose of vaccine with a high level of troponin, an enzyme that indicates damage to the heart. His level was over 9. “A very high level,” Dr. Meissner said.

“Will there be scarring to the myocardium? Will there be a predisposition to arrhythmias later on? Will there be an early onset of heart failure? We think that’s unlikely, but [we] don’t know that,” he said.

The CDC has scheduled an emergency meeting next week to convene an expert panel on immunization practices to further review the events.

In addition to the information presented at the FDA’s meeting, doctors at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, recently described seven cases in teens – all boys – who developed heart inflammation within 4 days of getting the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine.

The study was published June 10 in Pediatrics. All the boys were hospitalized and treated with anti-inflammatory medications including NSAIDs and steroids. Most were discharged within a few days and all recovered from their symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert reported on June 10, detailing data on cases of myocarditis and pericarditis detected through a government safety system.

The side effect seems to be more common in teen boys and young men than in older adults and women and may occur in 16 cases for every 1 million people who got a second dose, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, deputy director of the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office, who presented information on the cases at a meeting of an expert panel that advises the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Telltale symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, and fever.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious diseases specialist from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., thinks certain characteristics are pointing toward a “rare, but real” signal. First, the events are clustering, occurring within days of vaccination. Second, they tend to be more common in males and younger people. Third, he says, the number of events is above the so-called “background rate” – the cases that could be expected in this age group even without vaccination.

“I don’t think we’re quite there yet. We haven’t tied a ribbon around it, but I think the data are trending in that direction,” he said.

The issue of myocarditis weighed heavily on the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee’s considerations of what kind and how much data might be needed to green light use of a vaccine for COVID in children.

Because the rates of hospitalization for COVID are low in kids, some felt that the FDA should require at least a year of study of the vaccines in clinical trials, the amount of data typically required for full approval, instead of the 2 months currently required for emergency use authorization. Others wondered whether the risks of vaccination – as low as they are – might outweigh the benefits in this age group.

“I don’t really see this as an emergency in children,” said committee member Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, the director of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kurilla, however, did say he thought having an expanded access program for children at high risk might make sense.

Most of the young adults who experienced myocarditis recovered quickly, though three needed intensive care and rehabilitation after their episodes. Among cases with known outcomes, 81% got better and 19% still have ongoing symptoms.

Adverse events reports

The data on myocarditis come from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, or VAERS, a database of health problems reported after vaccination. This reporting system, open to anyone, has benefits and limits. It gives the CDC and FDA the ability to rapidly detect potential safety issues, and it is large enough that it can detect rare events, something that’s beyond the power of even large clinical trials.

But it is observational, so that there’s no way to know if problems reported were caused by the vaccines or a coincidence.

But because VAERS works on an honor system, it can also be spammed, and it carries the bias of the person who’s doing the reporting, from clinicians to average patients. For that reason, Dr. Shimabukuro said they are actively investigating and confirming each report they get.

Out of more than 12 million doses administered to youth ages 16-24, the CDC says it has 275 reports of heart inflammation following vaccination in this age group. The CDC has analyzed a total 475 cases of myocarditis after vaccination in people under age 30 that were reported to VAERS.

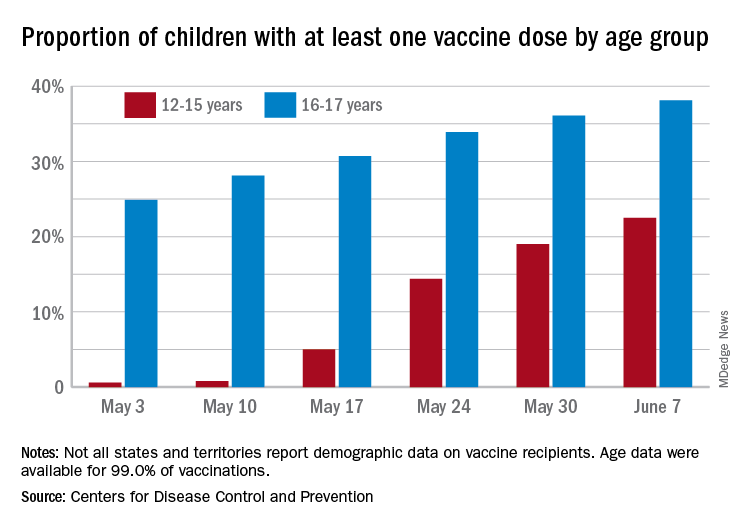

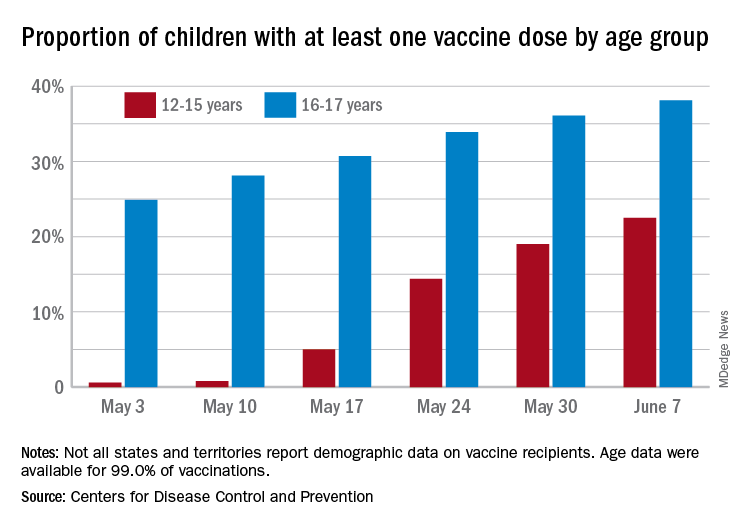

The vaccines linked to the events are the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna. The only vaccines currently authorized for use in adolescents are made by Pfizer. Because the Pfizer vaccine was authorized for use in kids as young as 12 last month, there’s not yet enough data to draw conclusions about the risk of myocarditis in kids ages 12-15.

Younger age groups have only received about 9% of the total doses of the vaccine so far, but they represent about 50% of the myocarditis cases reported after vaccination. “We clearly have an imbalance there,” Dr. Shimabukuro said.

The number of events in this age group appears to be above the rate that would be expected for these age groups without vaccines in the picture, he said, explaining that the number of events are in line with similar adverse events seen in young people in Israel and reported by the Department of Defense. Israel found the incidence of myocarditis after vaccination was 50 cases per million for men ages 18-30.

More study needed

Another system tracking adverse events through hospitals, the Vaccine Safety Datalink, didn’t show reports of heart inflammation above numbers that are normally seen in the population, but it did show that inflammation was more likely after a second dose of the vaccine.

“Should this be included in informed consent?” asked Cody Meissner, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Tufts University, Boston, and a member of the FDA committee.

“I think it’s hard to deny there seem to be some [events that seem] to be occurring in terms of myocarditis,” he said.

Dr. Meissner said later in the committee’s discussion that his own hospital had recently admitted a 12-year-old boy who developed heart swelling 2 days after the second dose of vaccine with a high level of troponin, an enzyme that indicates damage to the heart. His level was over 9. “A very high level,” Dr. Meissner said.

“Will there be scarring to the myocardium? Will there be a predisposition to arrhythmias later on? Will there be an early onset of heart failure? We think that’s unlikely, but [we] don’t know that,” he said.

The CDC has scheduled an emergency meeting next week to convene an expert panel on immunization practices to further review the events.

In addition to the information presented at the FDA’s meeting, doctors at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, recently described seven cases in teens – all boys – who developed heart inflammation within 4 days of getting the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine.

The study was published June 10 in Pediatrics. All the boys were hospitalized and treated with anti-inflammatory medications including NSAIDs and steroids. Most were discharged within a few days and all recovered from their symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert reported on June 10, detailing data on cases of myocarditis and pericarditis detected through a government safety system.

The side effect seems to be more common in teen boys and young men than in older adults and women and may occur in 16 cases for every 1 million people who got a second dose, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, deputy director of the CDC’s Immunization Safety Office, who presented information on the cases at a meeting of an expert panel that advises the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on vaccines.

Telltale symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, and fever.

William Schaffner, MD, an infectious diseases specialist from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., thinks certain characteristics are pointing toward a “rare, but real” signal. First, the events are clustering, occurring within days of vaccination. Second, they tend to be more common in males and younger people. Third, he says, the number of events is above the so-called “background rate” – the cases that could be expected in this age group even without vaccination.

“I don’t think we’re quite there yet. We haven’t tied a ribbon around it, but I think the data are trending in that direction,” he said.

The issue of myocarditis weighed heavily on the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee’s considerations of what kind and how much data might be needed to green light use of a vaccine for COVID in children.

Because the rates of hospitalization for COVID are low in kids, some felt that the FDA should require at least a year of study of the vaccines in clinical trials, the amount of data typically required for full approval, instead of the 2 months currently required for emergency use authorization. Others wondered whether the risks of vaccination – as low as they are – might outweigh the benefits in this age group.

“I don’t really see this as an emergency in children,” said committee member Michael Kurilla, MD, PhD, the director of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kurilla, however, did say he thought having an expanded access program for children at high risk might make sense.

Most of the young adults who experienced myocarditis recovered quickly, though three needed intensive care and rehabilitation after their episodes. Among cases with known outcomes, 81% got better and 19% still have ongoing symptoms.

Adverse events reports

The data on myocarditis come from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System, or VAERS, a database of health problems reported after vaccination. This reporting system, open to anyone, has benefits and limits. It gives the CDC and FDA the ability to rapidly detect potential safety issues, and it is large enough that it can detect rare events, something that’s beyond the power of even large clinical trials.

But it is observational, so that there’s no way to know if problems reported were caused by the vaccines or a coincidence.

But because VAERS works on an honor system, it can also be spammed, and it carries the bias of the person who’s doing the reporting, from clinicians to average patients. For that reason, Dr. Shimabukuro said they are actively investigating and confirming each report they get.

Out of more than 12 million doses administered to youth ages 16-24, the CDC says it has 275 reports of heart inflammation following vaccination in this age group. The CDC has analyzed a total 475 cases of myocarditis after vaccination in people under age 30 that were reported to VAERS.

The vaccines linked to the events are the mRNA vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna. The only vaccines currently authorized for use in adolescents are made by Pfizer. Because the Pfizer vaccine was authorized for use in kids as young as 12 last month, there’s not yet enough data to draw conclusions about the risk of myocarditis in kids ages 12-15.

Younger age groups have only received about 9% of the total doses of the vaccine so far, but they represent about 50% of the myocarditis cases reported after vaccination. “We clearly have an imbalance there,” Dr. Shimabukuro said.

The number of events in this age group appears to be above the rate that would be expected for these age groups without vaccines in the picture, he said, explaining that the number of events are in line with similar adverse events seen in young people in Israel and reported by the Department of Defense. Israel found the incidence of myocarditis after vaccination was 50 cases per million for men ages 18-30.

More study needed

Another system tracking adverse events through hospitals, the Vaccine Safety Datalink, didn’t show reports of heart inflammation above numbers that are normally seen in the population, but it did show that inflammation was more likely after a second dose of the vaccine.

“Should this be included in informed consent?” asked Cody Meissner, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Tufts University, Boston, and a member of the FDA committee.

“I think it’s hard to deny there seem to be some [events that seem] to be occurring in terms of myocarditis,” he said.

Dr. Meissner said later in the committee’s discussion that his own hospital had recently admitted a 12-year-old boy who developed heart swelling 2 days after the second dose of vaccine with a high level of troponin, an enzyme that indicates damage to the heart. His level was over 9. “A very high level,” Dr. Meissner said.

“Will there be scarring to the myocardium? Will there be a predisposition to arrhythmias later on? Will there be an early onset of heart failure? We think that’s unlikely, but [we] don’t know that,” he said.

The CDC has scheduled an emergency meeting next week to convene an expert panel on immunization practices to further review the events.

In addition to the information presented at the FDA’s meeting, doctors at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, recently described seven cases in teens – all boys – who developed heart inflammation within 4 days of getting the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine.

The study was published June 10 in Pediatrics. All the boys were hospitalized and treated with anti-inflammatory medications including NSAIDs and steroids. Most were discharged within a few days and all recovered from their symptoms.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is HIV criminalization the No. 1 barrier to ending the epidemic?

For many people, being told that they are HIV positive is no longer a death sentence. But for Robert Suttle, a Black gay man and social justice educator, it is a life sentence.

Unexpectedly caught up in the HIV criminalization web at the age of 30, Mr. Suttle spent 6 months in a Louisiana state prison for a consensual sexual relationship with an adult partner. The crime? Not disclosing his HIV-positive status, a charge that Mr. Suttle says is untrue.

“I did disclose my status to my partner; however, I can’t really answer how they might have received it,” he said.

Today, at the age of 42, Mr. Suttle still carries the indelible stain of a conviction and of being a registered sex offender. “After their diagnosis, criminal charge, and/or conviction, many people think they’re done – either ‘I’ve gotten out of prison’ or ‘I’m still on probation’ – whatever the case may be,” he explained. “But we’re still living out these collateral consequences, be it with housing, moving to another state, or finding a job.”

The same is true for HIV-positive people who are charged and tried but manage to dodge prison for one reason or another. Monique Howell, a straight, 40-year-old former army soldier and single mother of five children, said that she was afraid to disclose her HIV status to a sexual partner but did advise him to wear a condom.* She points to her DD14 discharge papers (i.e., forms that verify that someone served in the military) that were issued when her military duty was rescinded following the dismissal of her court case.

“I was going to reenlist, but I got in trouble,” she said. She explained that although a DD14 separation helps to ensure that she can receive benefits and care, the papers were issued with a caveat stating “serious offense,” an indelible stain that, like Mr. Suttle’s, will follow her for the rest of her life.

Laws criminalize myths and misconceptions

HIV criminalization laws subject persons whose behaviors may expose others to HIV to felony or misdemeanor charges. Depending on the state, they can carry prison terms ranging from less than 10 years to life, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Originally enacted at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1986, when fear was rampant and hundreds were dying, the laws were intended to reduce HIV transmission. But they’ve had unintended consequences: Amplifying stigmatization and discrimination and perpetuating HIV myths and misconceptions, including how HIV is transmitted.

Decades of scientific advances challenge the most basic reasoning behind laws (for example, that transmission is possible via biting or spitting or through a single sexual act, which studies have shown poses a risk as low as 0%-1.4%). In addition, few laws reflect one of the most important HIV research findings of the past decade: undetectable equals untransmittable, meaning that the virus cannot be sexually transmitted by people who are taking antiretroviral therapy and whose viral loads are undetectable.

In most of these cases, individuals who are positive for HIV are charged and punished for unintentional exposure, not deliberate intent to harm. Moreover, for the charge to stick, sexual partners don’t need to have acquired the virus or prove the transmission source if they do become HIV positive.

Ms. Howell noted that it was the Army that brought the charges against her, not her sexual partner at that time (who, incidentally, tested negative). He even testified on her behalf at the trial. “I’ll never forget it,” she said. “He said, ‘I don’t want anything to happen to Monique; even if you put her behind bars, she’s still HIV-positive and she’s still got those children. She told me to get a condom, and I chose not to.’ ”

Criminal vs. clinical fallout

In 2018, 20 scientists across the world issued a consensus statement underscoring the fact that HIV criminalization laws are based on fallacies and faulty science. The statement (which remains one of the most accessed in the Journal of the International AIDS Society) also points out that 33 countries (including the United States) use general criminal statutes such as attempted murder or reckless endangerment to lengthen sentences when people with HIV commit crimes.

When the laws were created, “many were the equivalent [to general criminal laws], because HIV was seen as a death sentence,” explained Chris Beyrer MD, MPH, professor of public health and human rights at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore. “So, failure to disclose your status, to wear a condom was seen as risking someone else’s life, which is no longer the case,” he added.

In fact, “from the perspective of the kinds of impact that these laws have had on transmission, or risk, or behavior, what you find is that they really have no public health benefit and they have real public harms,” said Dr. Beyrer.

Claire Farel, MD, assistant professor and medical director of the UNC Infectious Diseases Clinic at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, concurs. “Because of the criminalization undercurrent, there are people who don’t get tested, meaning that they are at risk for worse health outcomes, such as cancer, vascular disease, and of course HIV-related poor outcomes, including progression to AIDS.”

Farel also points to the residual stigma associated with HIV. “Much of this is inextricable from that surrounding homophobia, especially among young men of color who have sex with men. It opens up a larger conversation that a lot of people don’t want to engage in,” she said.

Laws broaden existing disparities even further

The CDC released a study June 4 showing substantial declines in the overall incidence of HIV in the United States, with an important caveat: There’s been a worsening disparity in cases. Access to care and engagement with care remain poor among certain populations. For example, Black individuals accounted for 41% of new HIV infections in 2019, but they represent only 12% of the U.S. population; Hispanic/Latinx persons accounted for 29% of new infections, although they represent only 17% of the entire population.

The same is true for HIV criminalization: In 2020, more than 50% of defendants were people of color, according to U.S. case data collated by the HIV Justice Network.

Still, the momentum to change these antiquated laws is gaining speed. In May, the Illinois State Senate passed a bill repealing HIV criminalization, and this past March, Virginia’s Governor Ralph Northam signed a bill lowering HIV-related criminalization charges from a felony to a misdemeanor and changing the wording of its law to include both intent and transmission.** California, Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, and North Carolina have also modernized or repealed their laws.

Ending the U.S. HIV epidemic: Patients first

Without true HIV criminalization reform, efforts to change the public and clinical mindset regarding HIV from its being a highly stigmatized disease to a preventable, treatable infection are likely to fall short. Dr. Beyrer emphasized that the onus lies with the scientific and activist communities working together. “I don’t know how you can end the epidemic if you are still stigmatizing the people who are actually acquiring these infections,” he said.

There are steps that patients can take while these forces push for change.

“As people first process their diagnosis, they need to learn as much about HIV and the science behind it as possible,” advised Mr. Suttle. He said that to protect oneself, it’s essential to learn about HIV criminalization and the laws in one’s state.

“Find someone you can trust, starting with your medical provider if possible, and if you have a significant other, bring that person to your appointments so they can see that you are in care and doing all that you can do to lower viral loads and protect others,” he added.

Ms. Howell said that although people should be in treatment and care, attitudes also need to change on the clinician side. “We’re just given these meds, told to take them, and are sent on our merry ways, but they don’t tell us how to live our lives properly; nobody grabs us and says, hey, these are the laws and you need to know this or that.”

When a person who is HIV positive does get caught up in the system, if possible, that person should consult an attorney who understands these laws. Mr. Suttle suggested reaching out to organizations in the movement to end HIV criminalization (e.g., the Sero Project, the Center for HIV Law and Policy, or the Positive Women’s Network) for further support, help with cases (including providing experts to testify), social services, and other resources. Mr. Suttle also encourages people who need help and direction to reach out to him directly at [email protected].

Forty years ago, the CDC published its first report of an illness in five healthy gay men living in Los Angeles. The first cases in women were reported shortly thereafter. Over the years, there have been many scientific advances in prevention and treatment. But as Dr. Beyrer aptly noted in an editorial published January 2021 in The Lancet HIV, “time has not lessened the sting of the early decades of AIDS.”

“We should not have to be afraid of who we are because we are HIV positive,” said Ms. Howell.

Dr. Farel, Mr. Suttle, and Ms. Howell report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Beyrer has a consulting agreement with Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 6/14/2021: An earlier version of this story misstated Ms. Howell's age. She is 40.

**Correction, 6/14/2021: An earlier version of this story misspelled Gov. Northam's name.

For many people, being told that they are HIV positive is no longer a death sentence. But for Robert Suttle, a Black gay man and social justice educator, it is a life sentence.

Unexpectedly caught up in the HIV criminalization web at the age of 30, Mr. Suttle spent 6 months in a Louisiana state prison for a consensual sexual relationship with an adult partner. The crime? Not disclosing his HIV-positive status, a charge that Mr. Suttle says is untrue.

“I did disclose my status to my partner; however, I can’t really answer how they might have received it,” he said.

Today, at the age of 42, Mr. Suttle still carries the indelible stain of a conviction and of being a registered sex offender. “After their diagnosis, criminal charge, and/or conviction, many people think they’re done – either ‘I’ve gotten out of prison’ or ‘I’m still on probation’ – whatever the case may be,” he explained. “But we’re still living out these collateral consequences, be it with housing, moving to another state, or finding a job.”

The same is true for HIV-positive people who are charged and tried but manage to dodge prison for one reason or another. Monique Howell, a straight, 40-year-old former army soldier and single mother of five children, said that she was afraid to disclose her HIV status to a sexual partner but did advise him to wear a condom.* She points to her DD14 discharge papers (i.e., forms that verify that someone served in the military) that were issued when her military duty was rescinded following the dismissal of her court case.

“I was going to reenlist, but I got in trouble,” she said. She explained that although a DD14 separation helps to ensure that she can receive benefits and care, the papers were issued with a caveat stating “serious offense,” an indelible stain that, like Mr. Suttle’s, will follow her for the rest of her life.

Laws criminalize myths and misconceptions

HIV criminalization laws subject persons whose behaviors may expose others to HIV to felony or misdemeanor charges. Depending on the state, they can carry prison terms ranging from less than 10 years to life, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Originally enacted at the height of the AIDS epidemic in 1986, when fear was rampant and hundreds were dying, the laws were intended to reduce HIV transmission. But they’ve had unintended consequences: Amplifying stigmatization and discrimination and perpetuating HIV myths and misconceptions, including how HIV is transmitted.

Decades of scientific advances challenge the most basic reasoning behind laws (for example, that transmission is possible via biting or spitting or through a single sexual act, which studies have shown poses a risk as low as 0%-1.4%). In addition, few laws reflect one of the most important HIV research findings of the past decade: undetectable equals untransmittable, meaning that the virus cannot be sexually transmitted by people who are taking antiretroviral therapy and whose viral loads are undetectable.

In most of these cases, individuals who are positive for HIV are charged and punished for unintentional exposure, not deliberate intent to harm. Moreover, for the charge to stick, sexual partners don’t need to have acquired the virus or prove the transmission source if they do become HIV positive.