User login

Cutaneous Manifestations and Clinical Disparities in Patients Without Housing

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

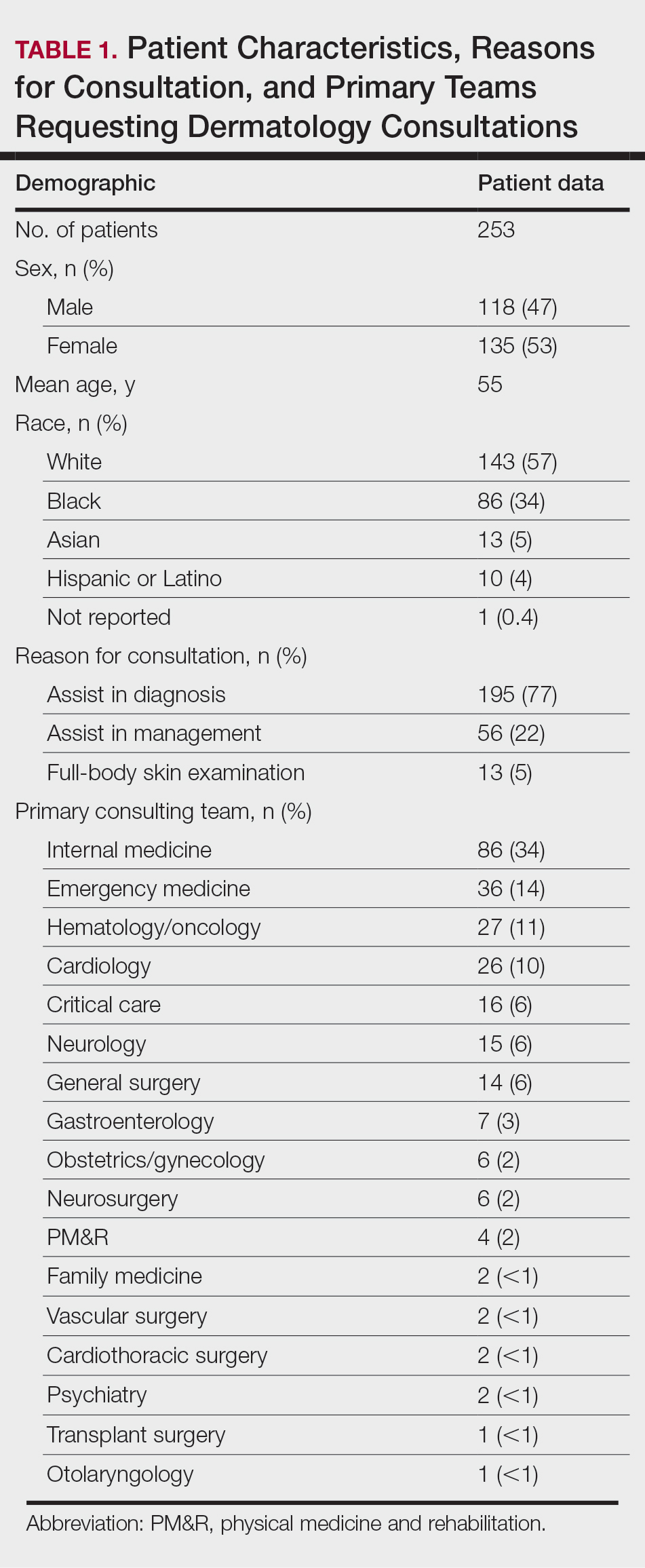

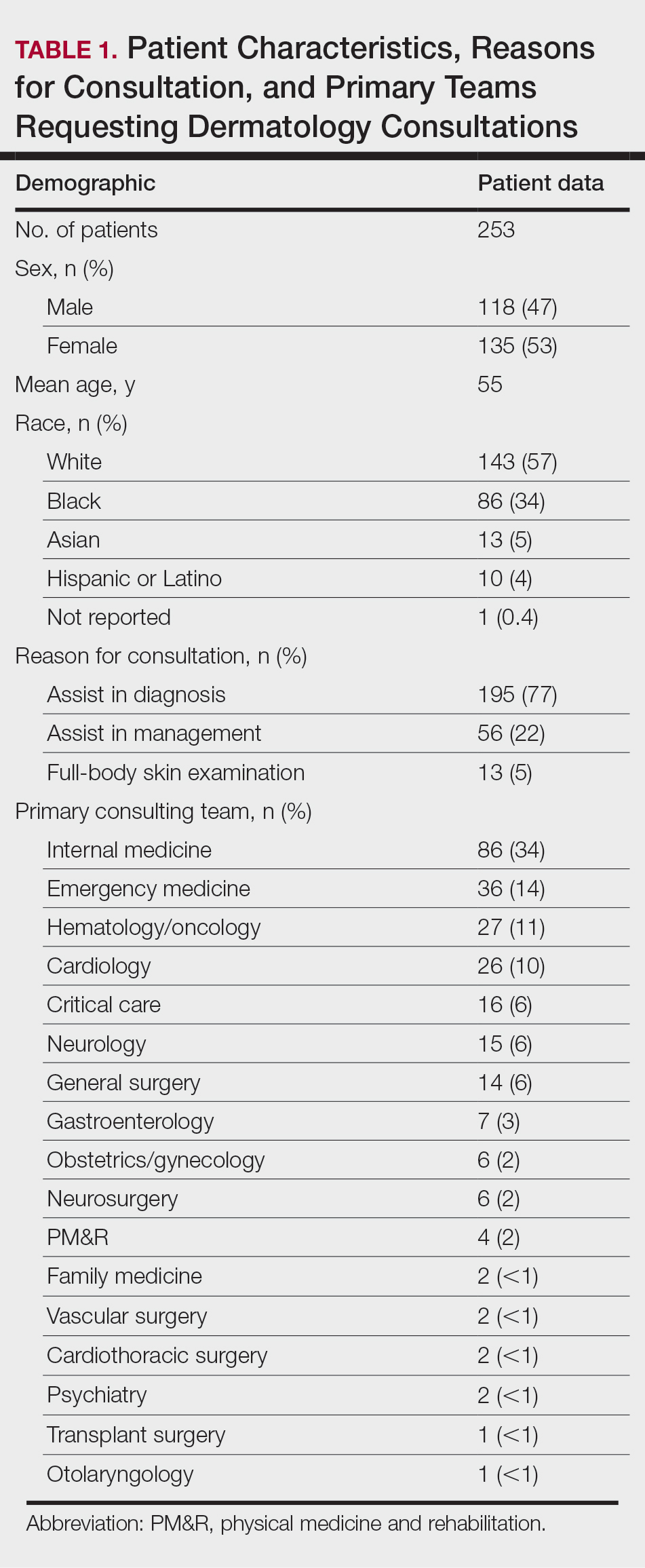

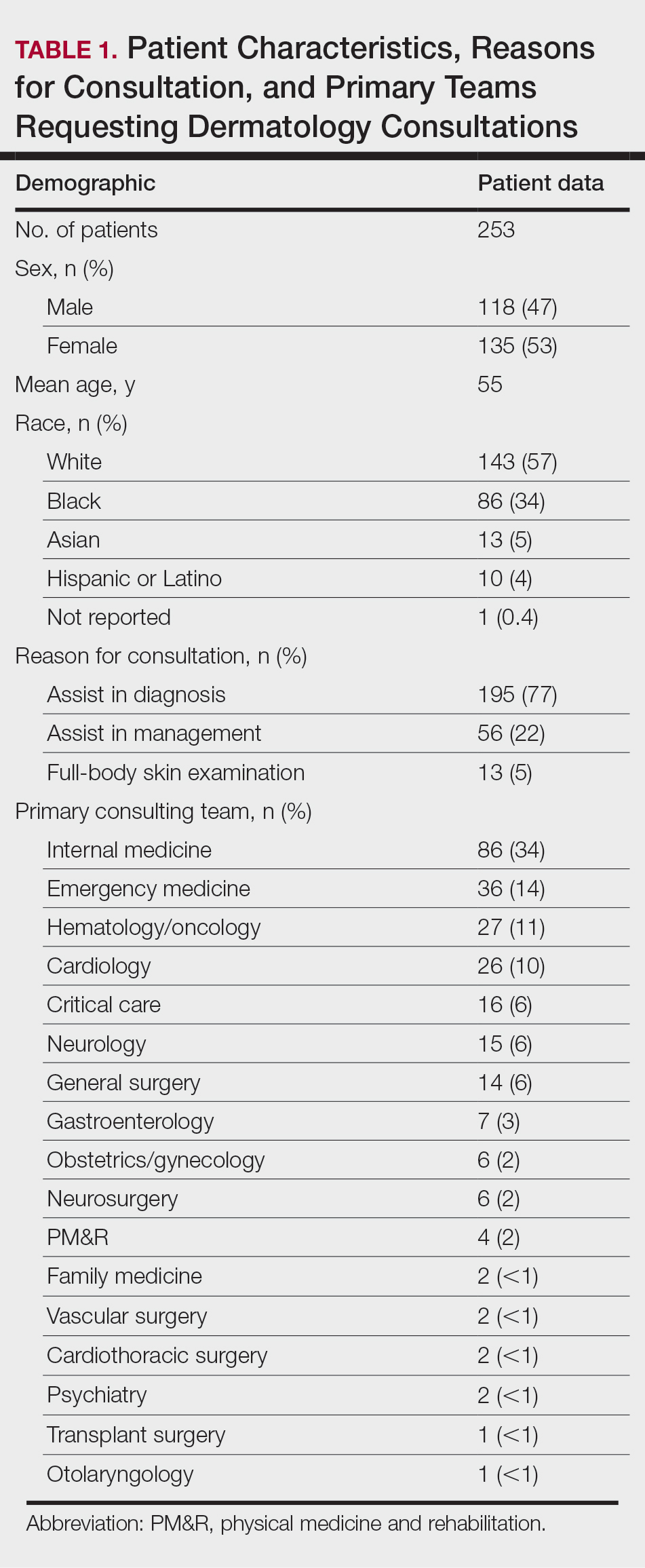

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

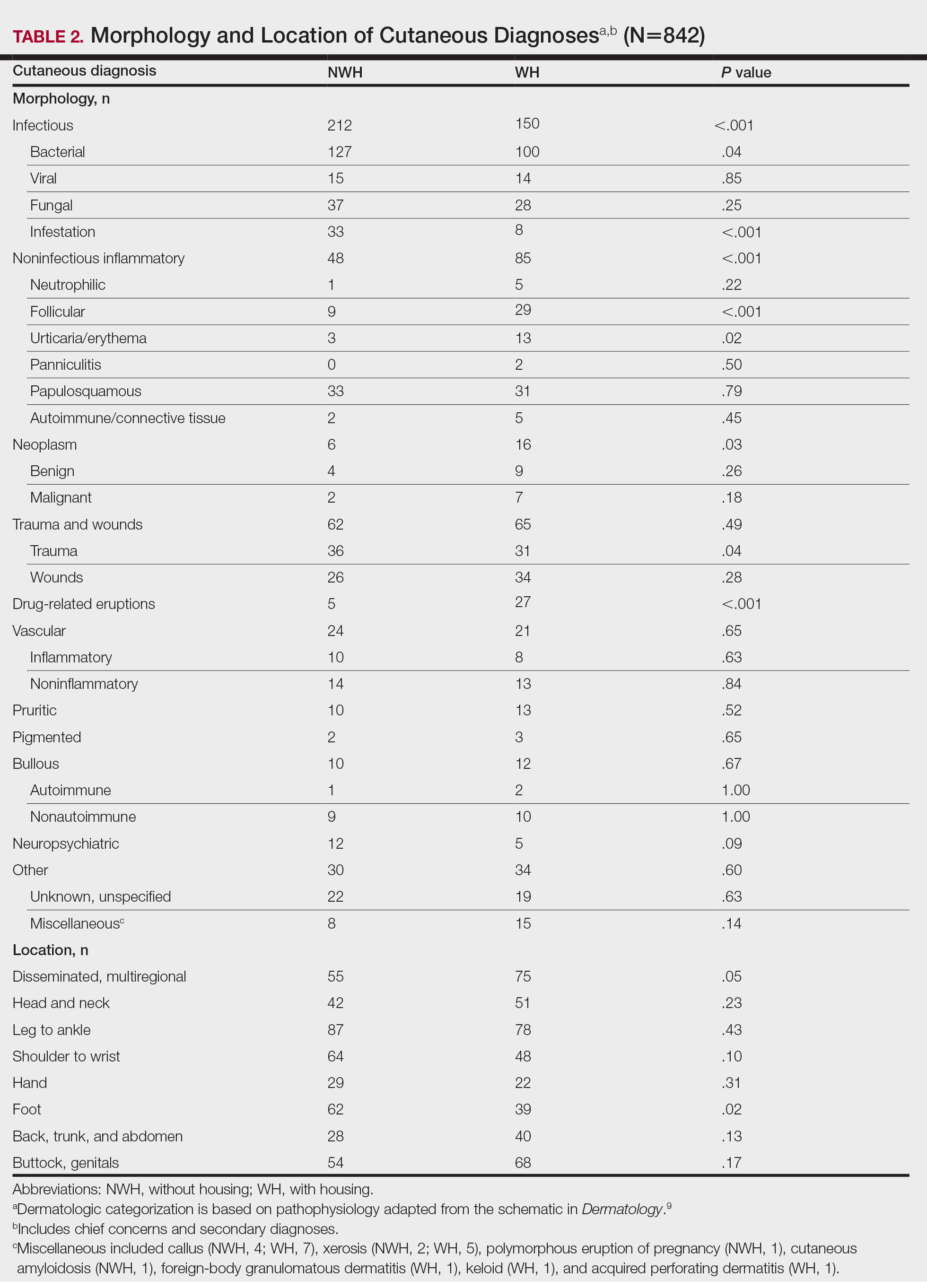

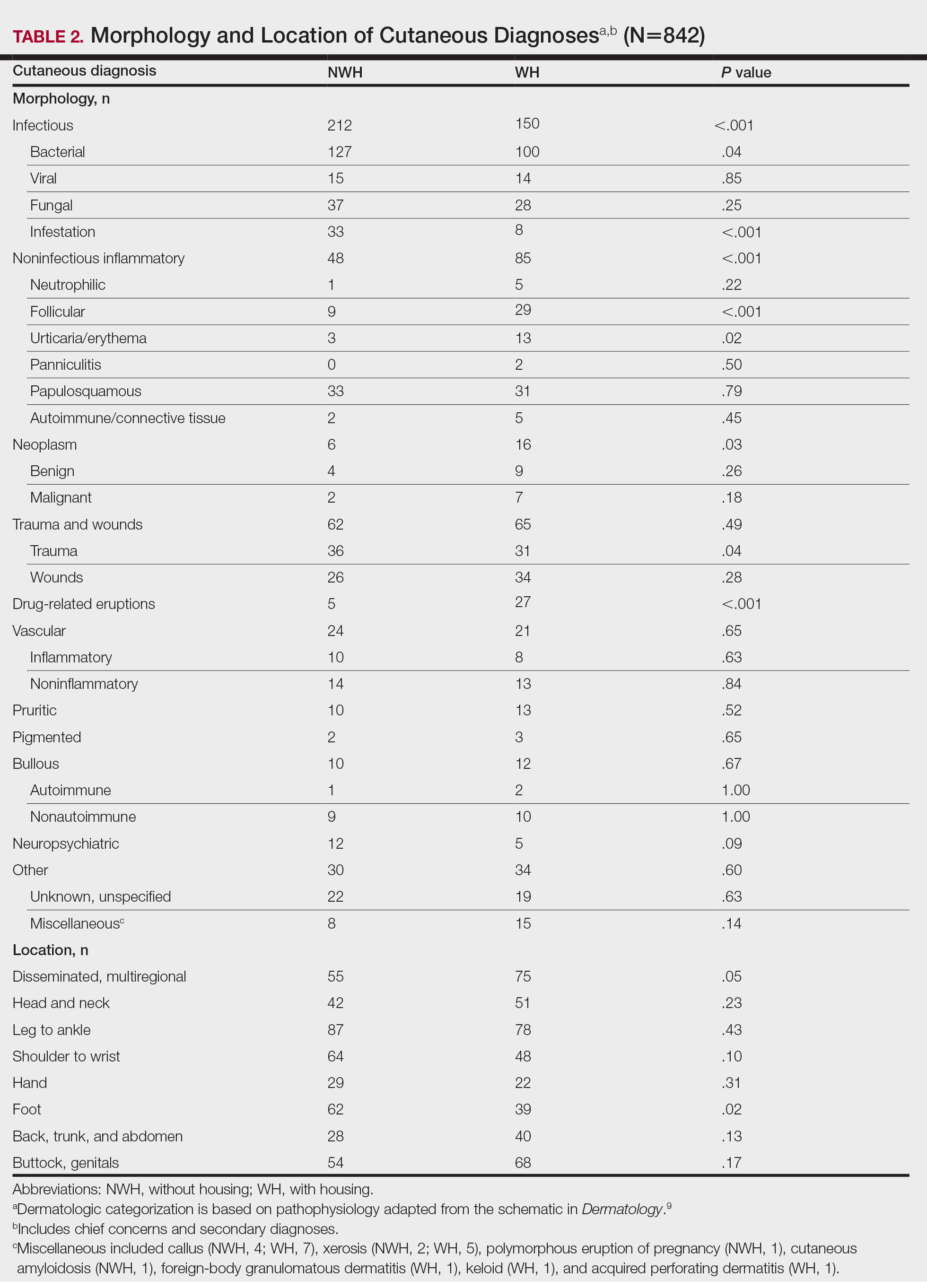

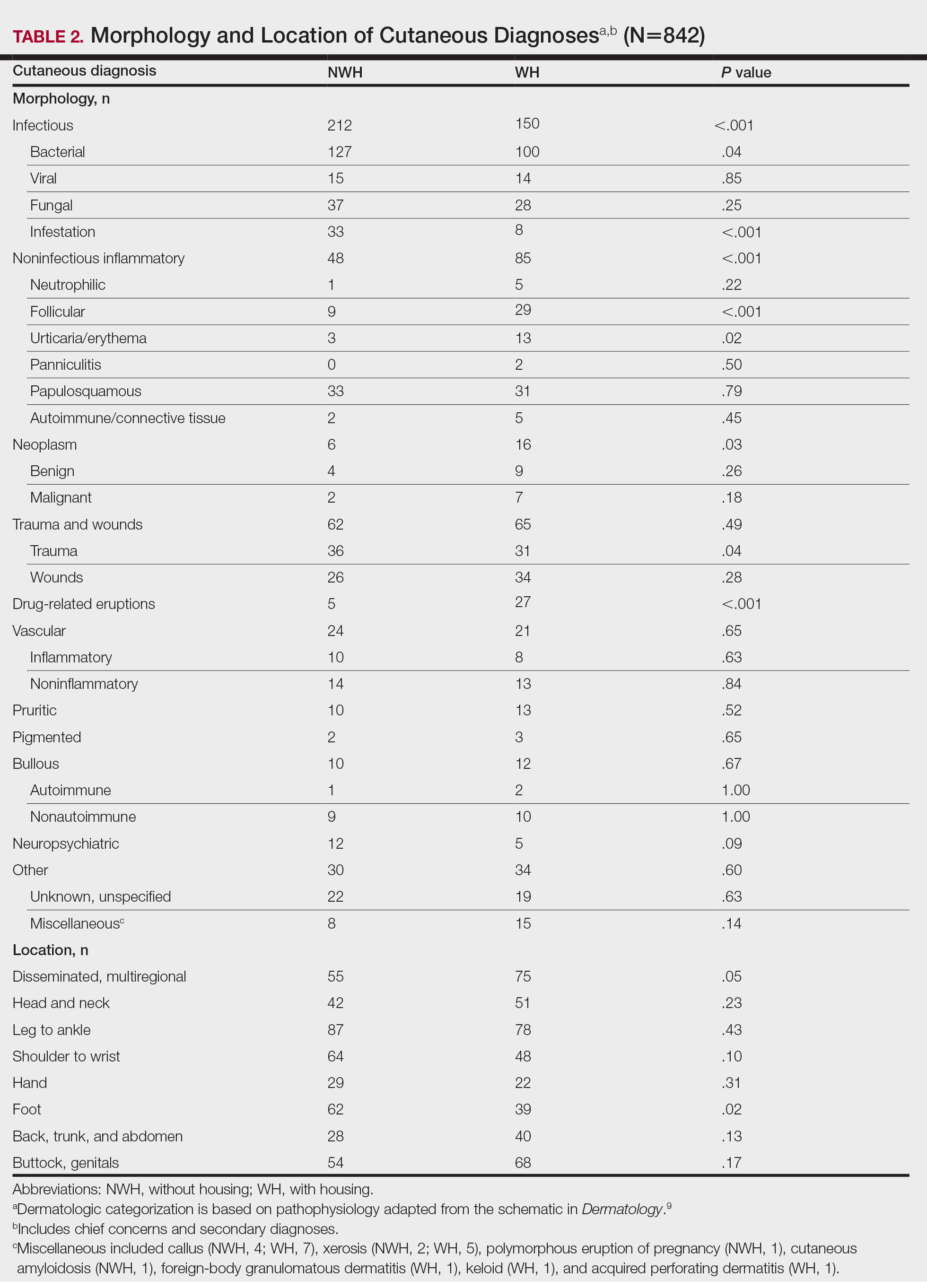

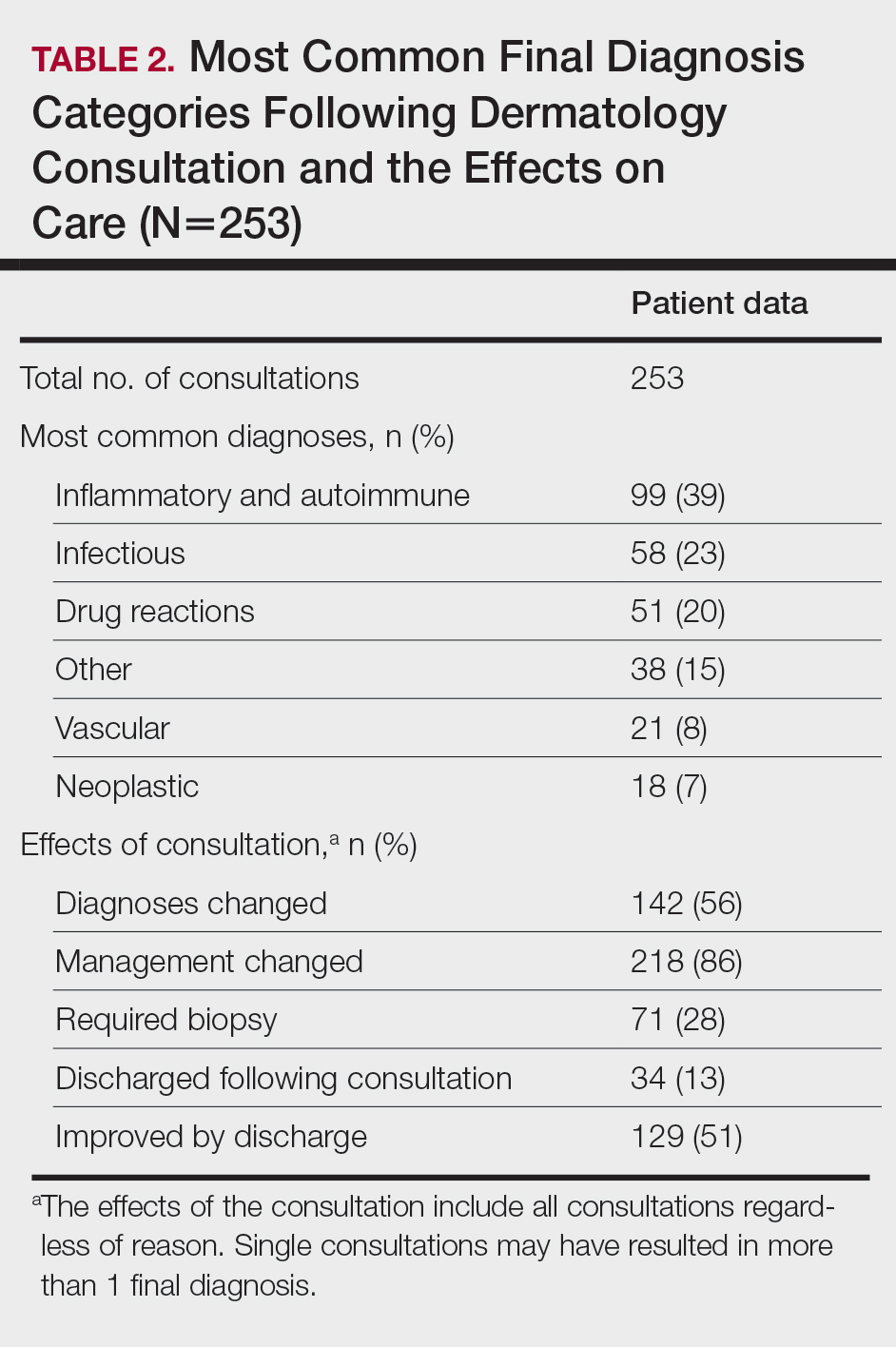

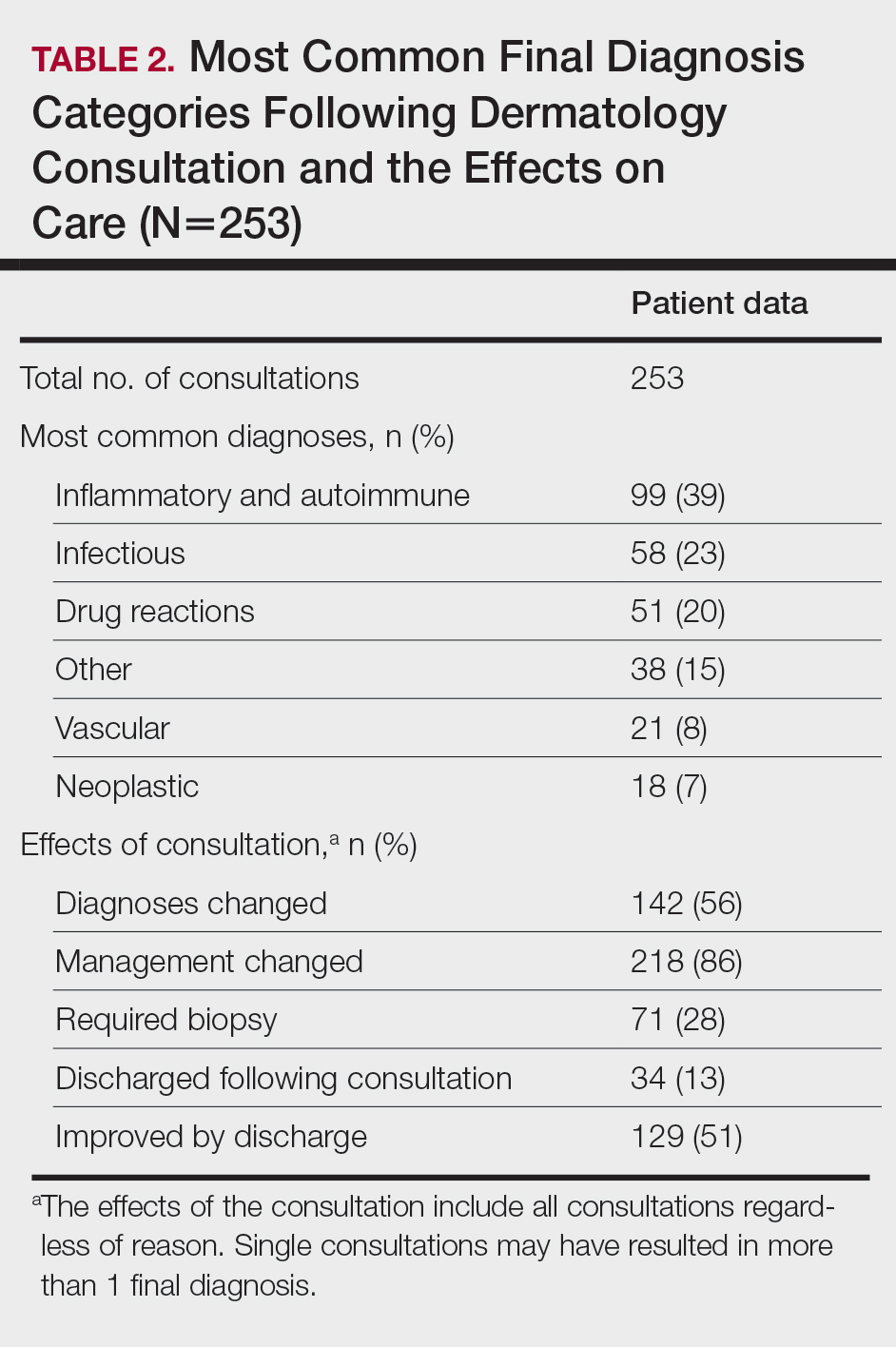

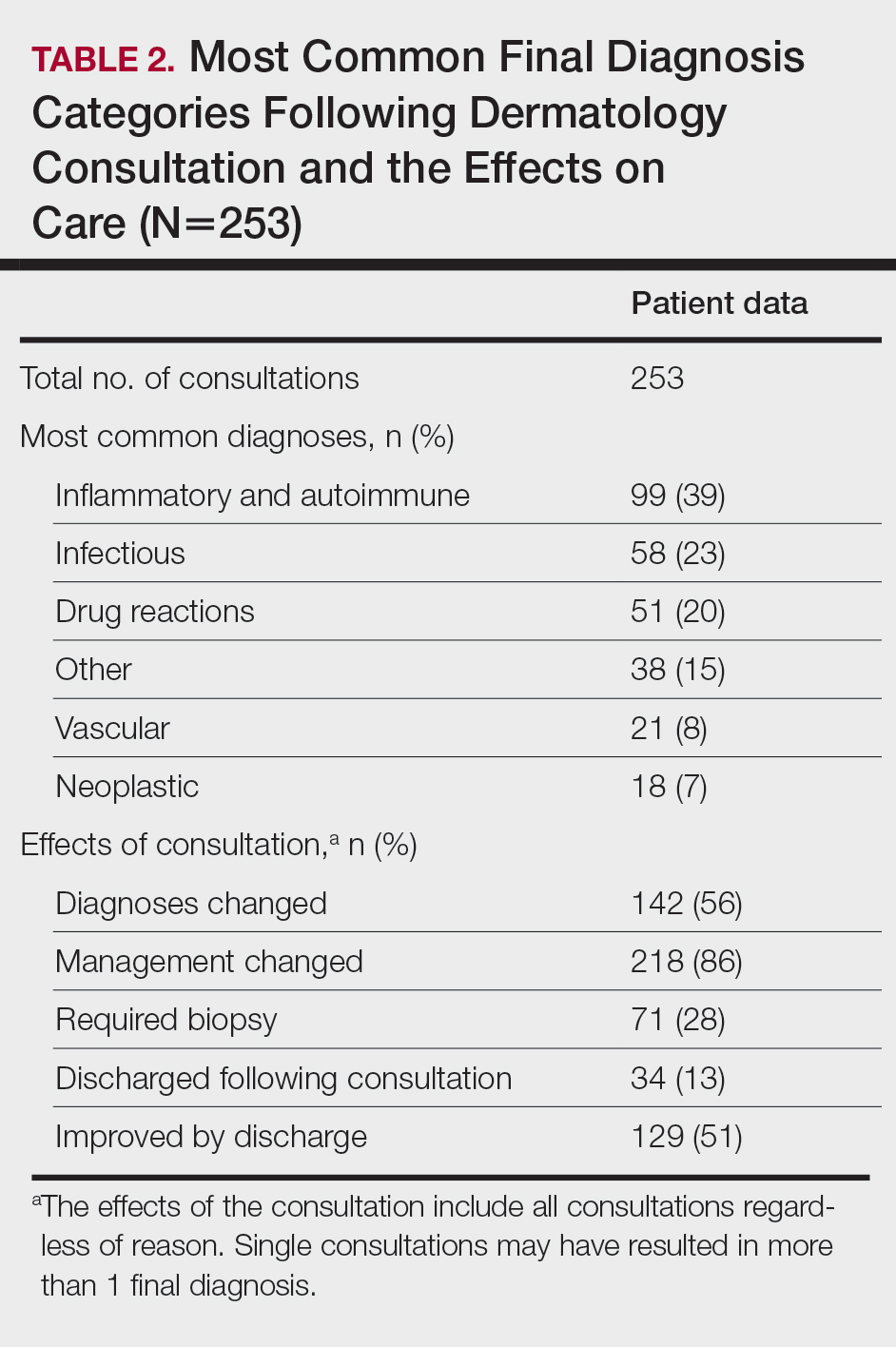

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

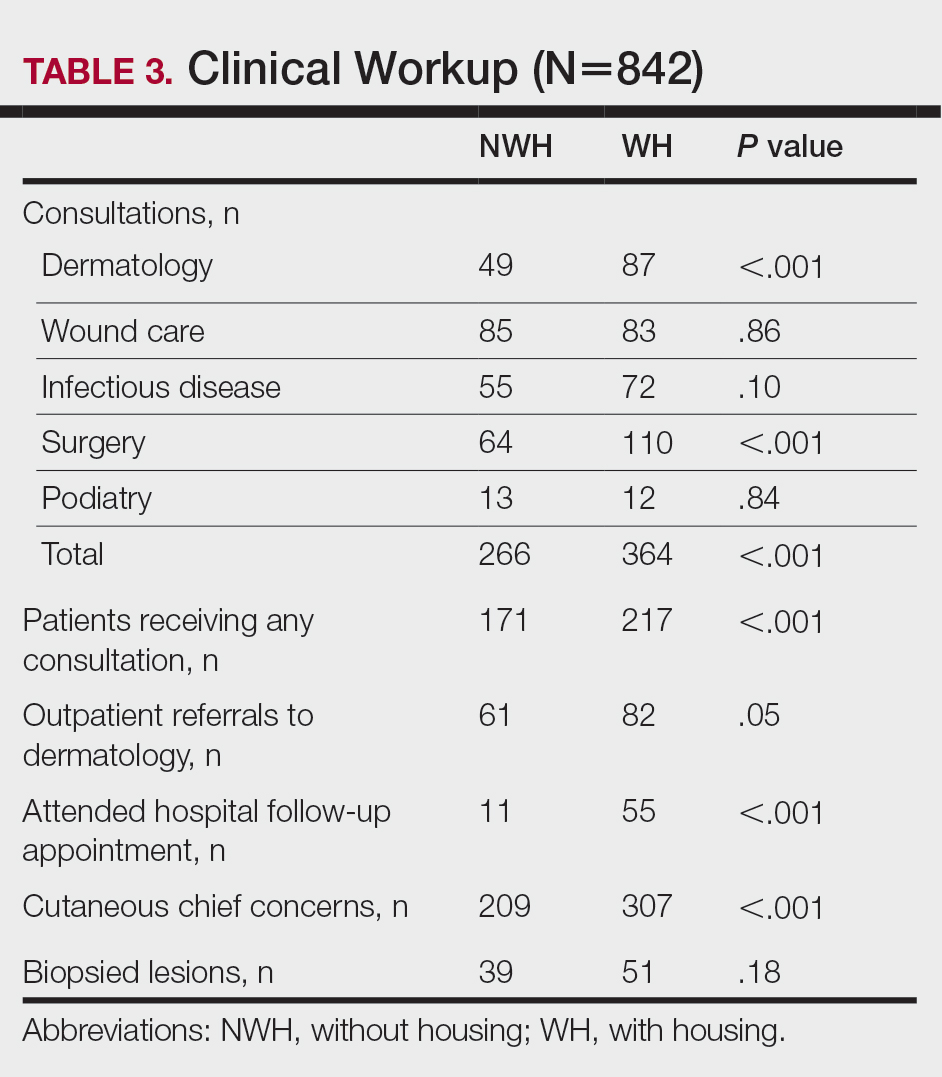

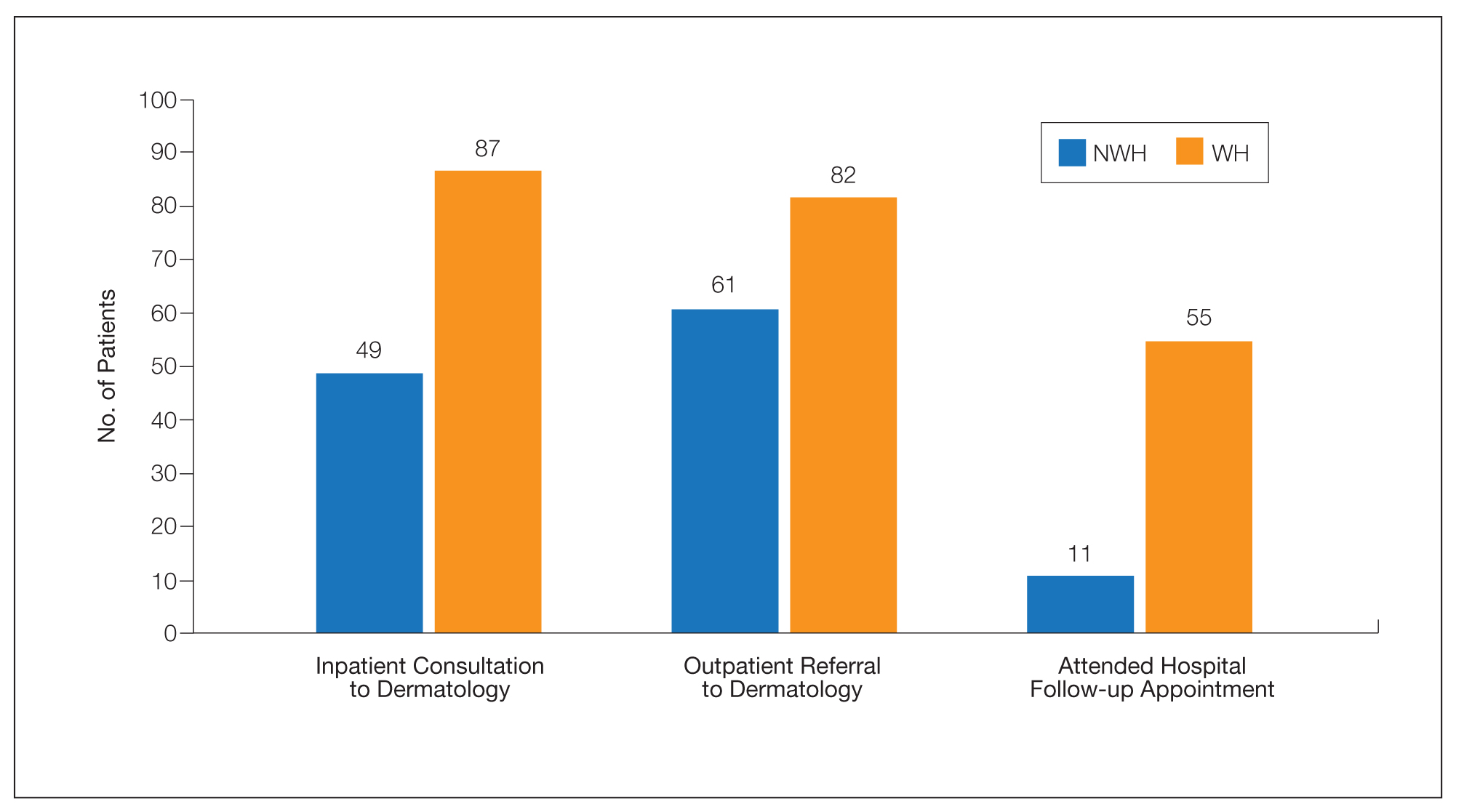

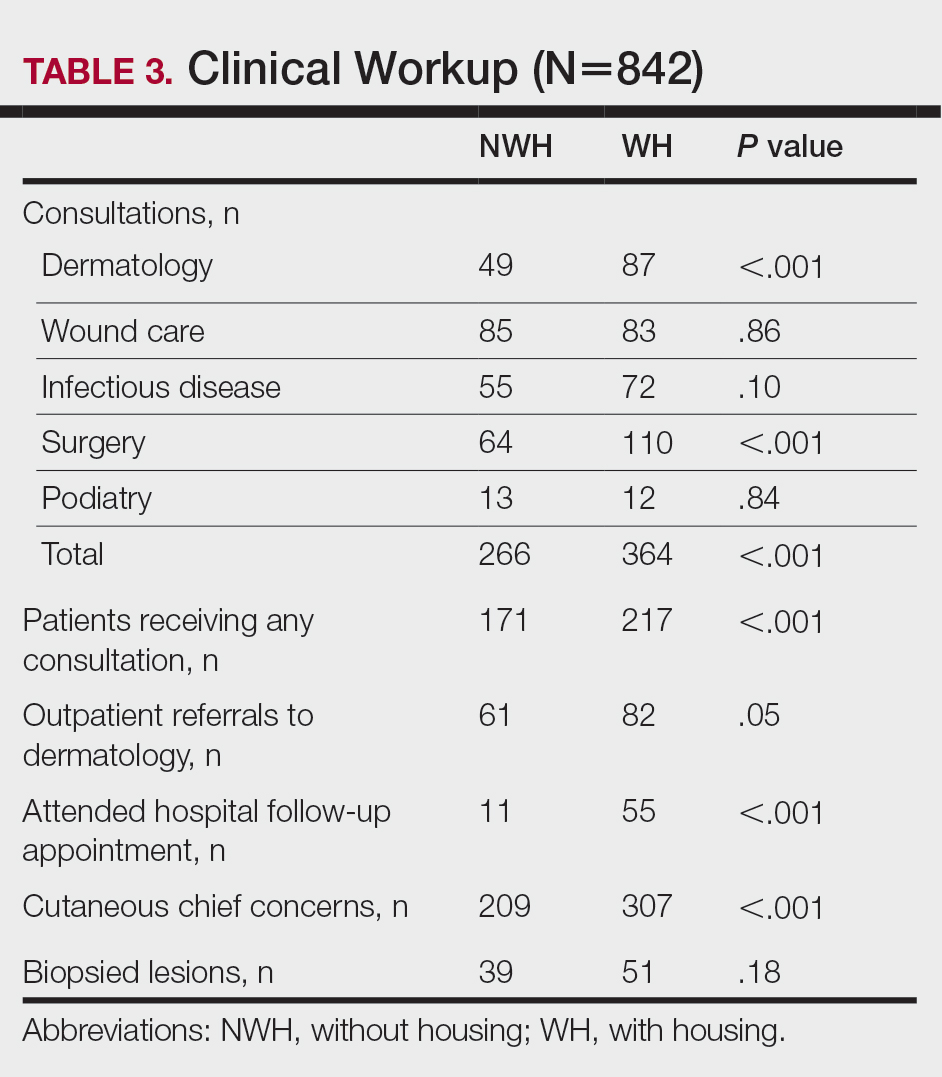

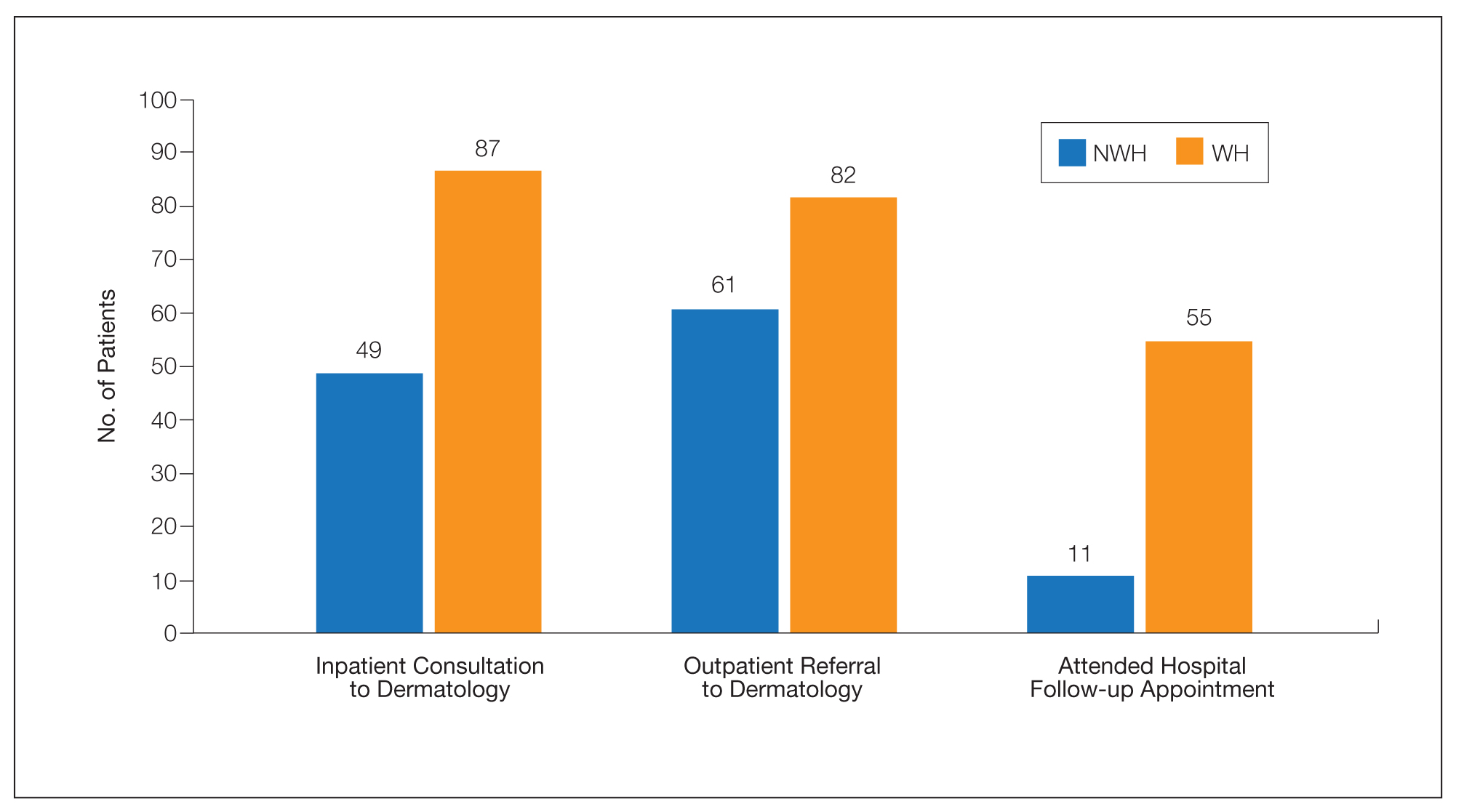

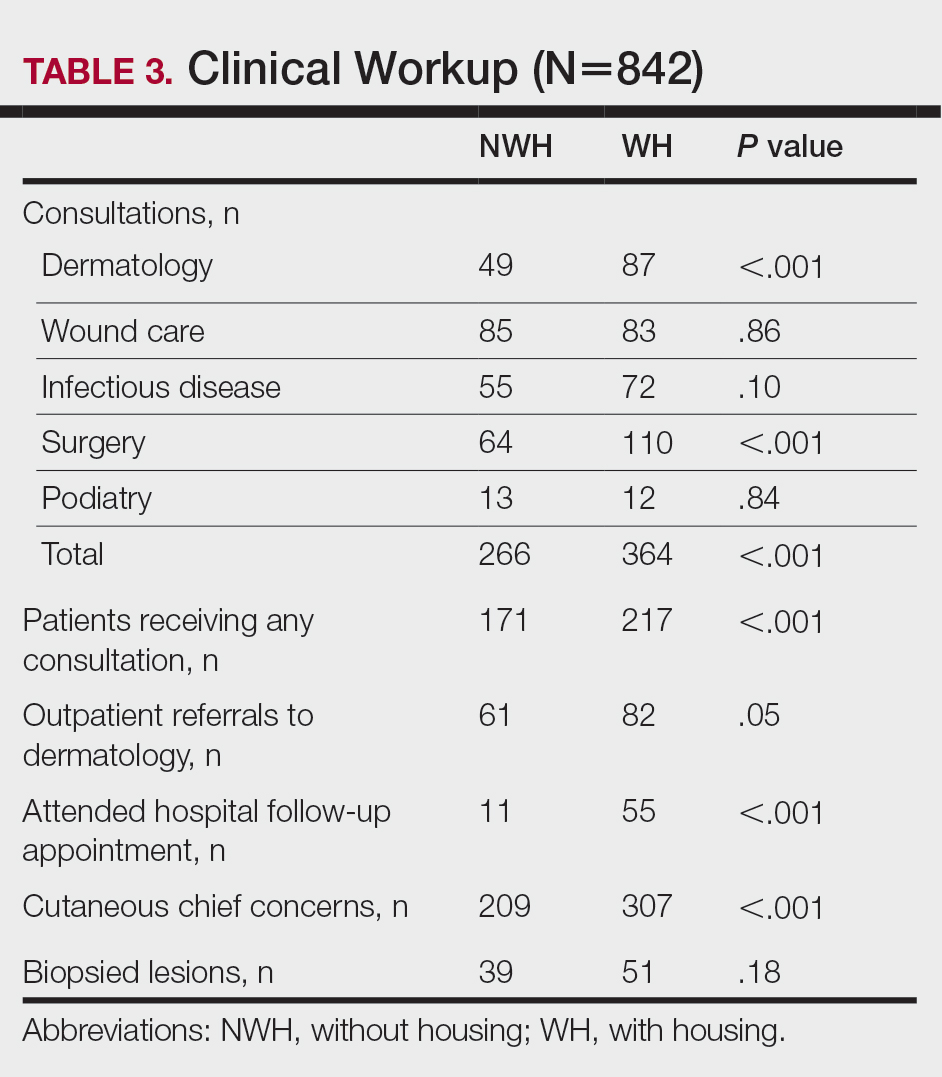

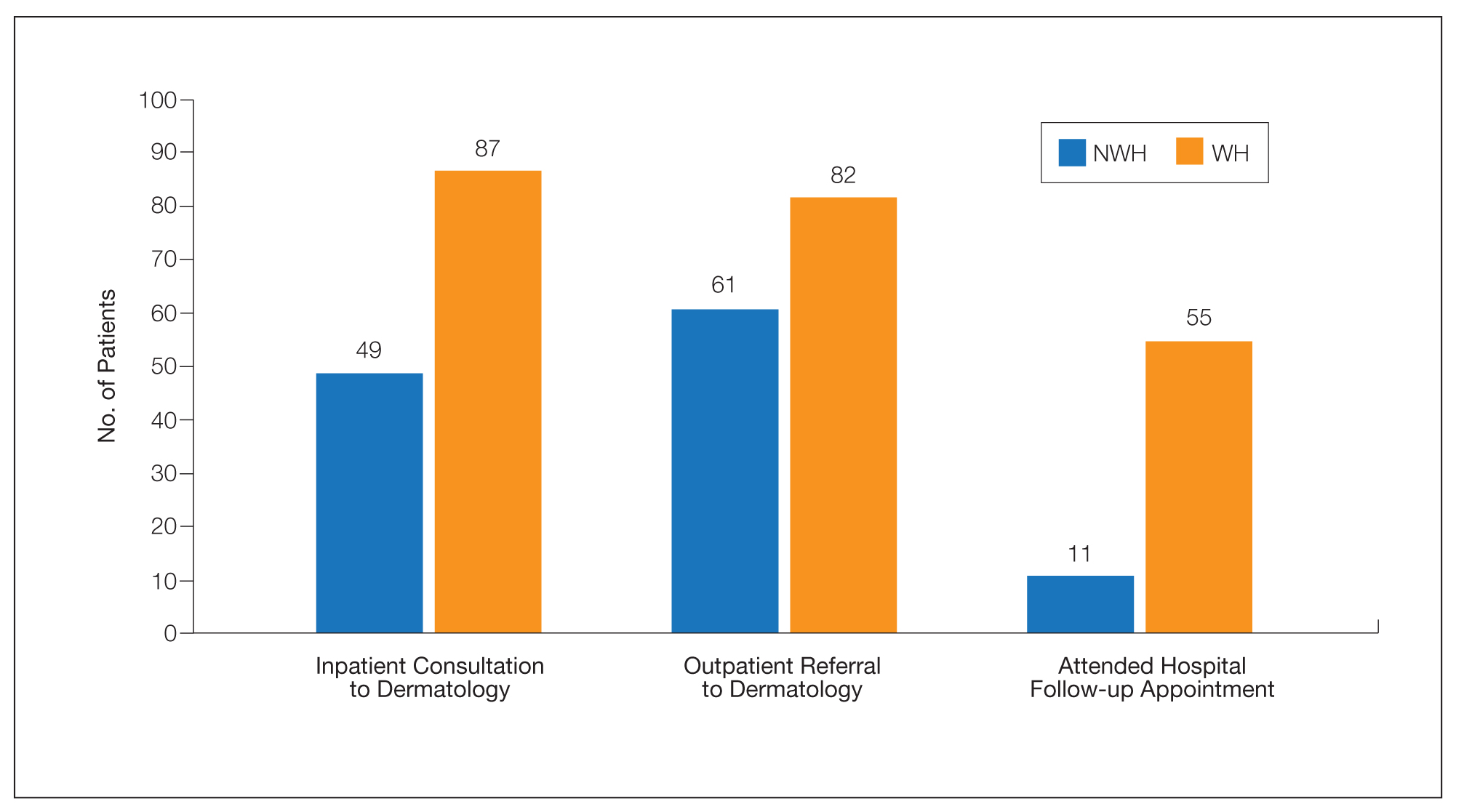

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

Practice Points

- Dermatologic disease in patients without housing (NWH) is characterized by more infectious concerns and fewer follicular and urticarial noninfectious inflammatory eruptions compared with matched controls of those with housing.

- Patients with housing more frequently presented with cutaneous chief concerns and received more consultations while in the hospital.

- This study uncovered notable pathological and clinical differences in treating dermatologic conditions in NWH patients.

Acyclovir-Resistant Cutaneous Herpes Simplex Virus in DOCK8 Deficiency

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

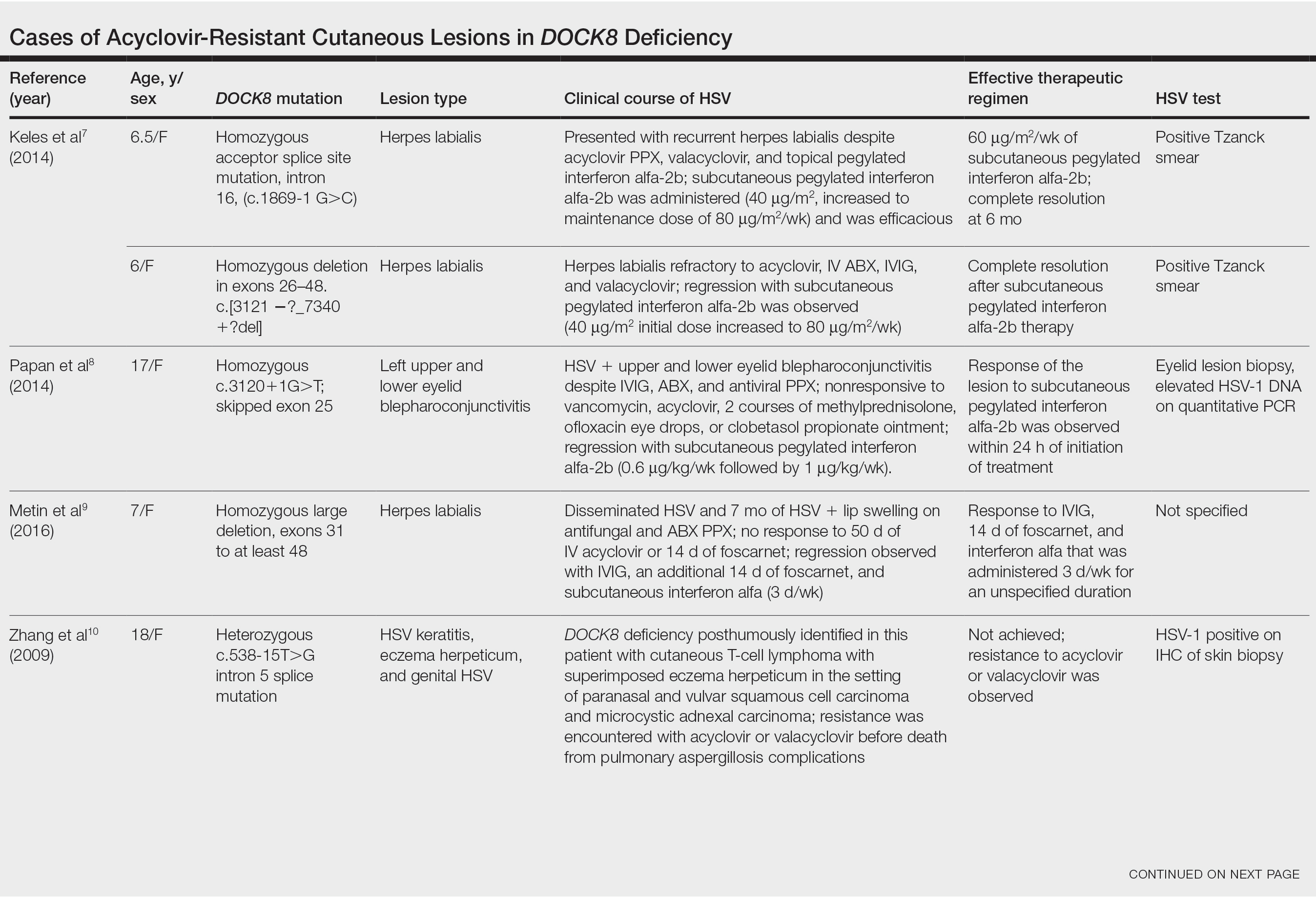

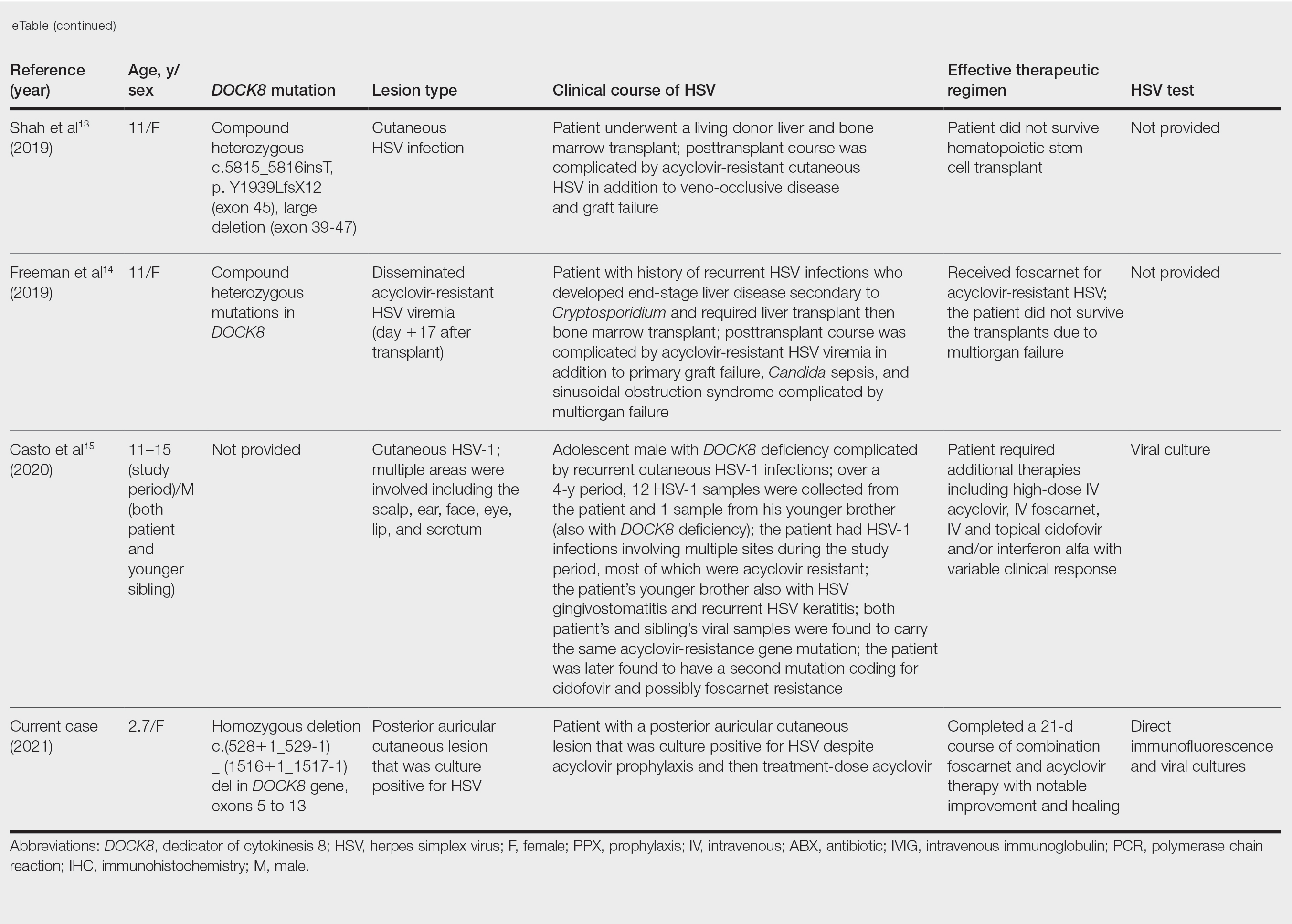

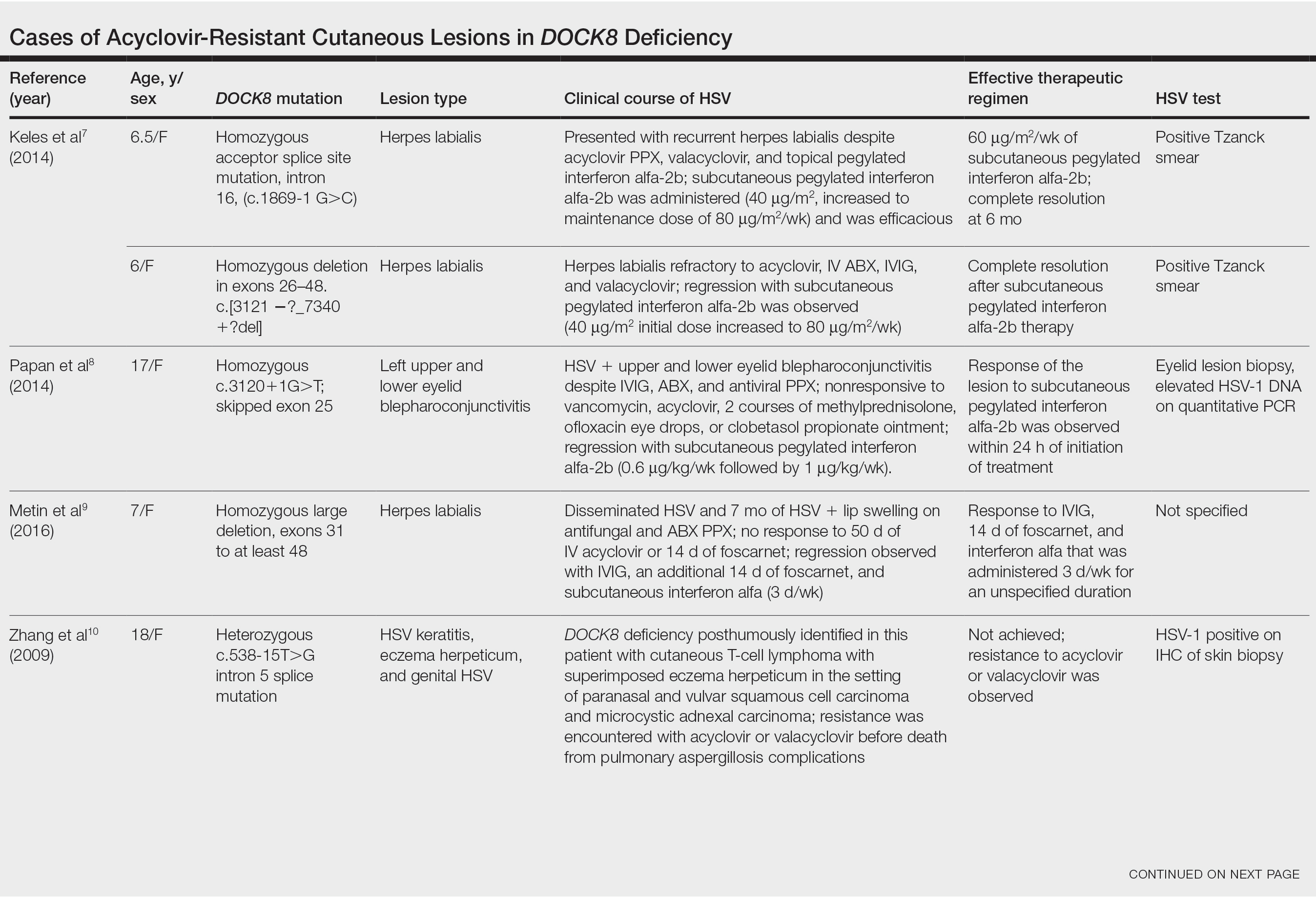

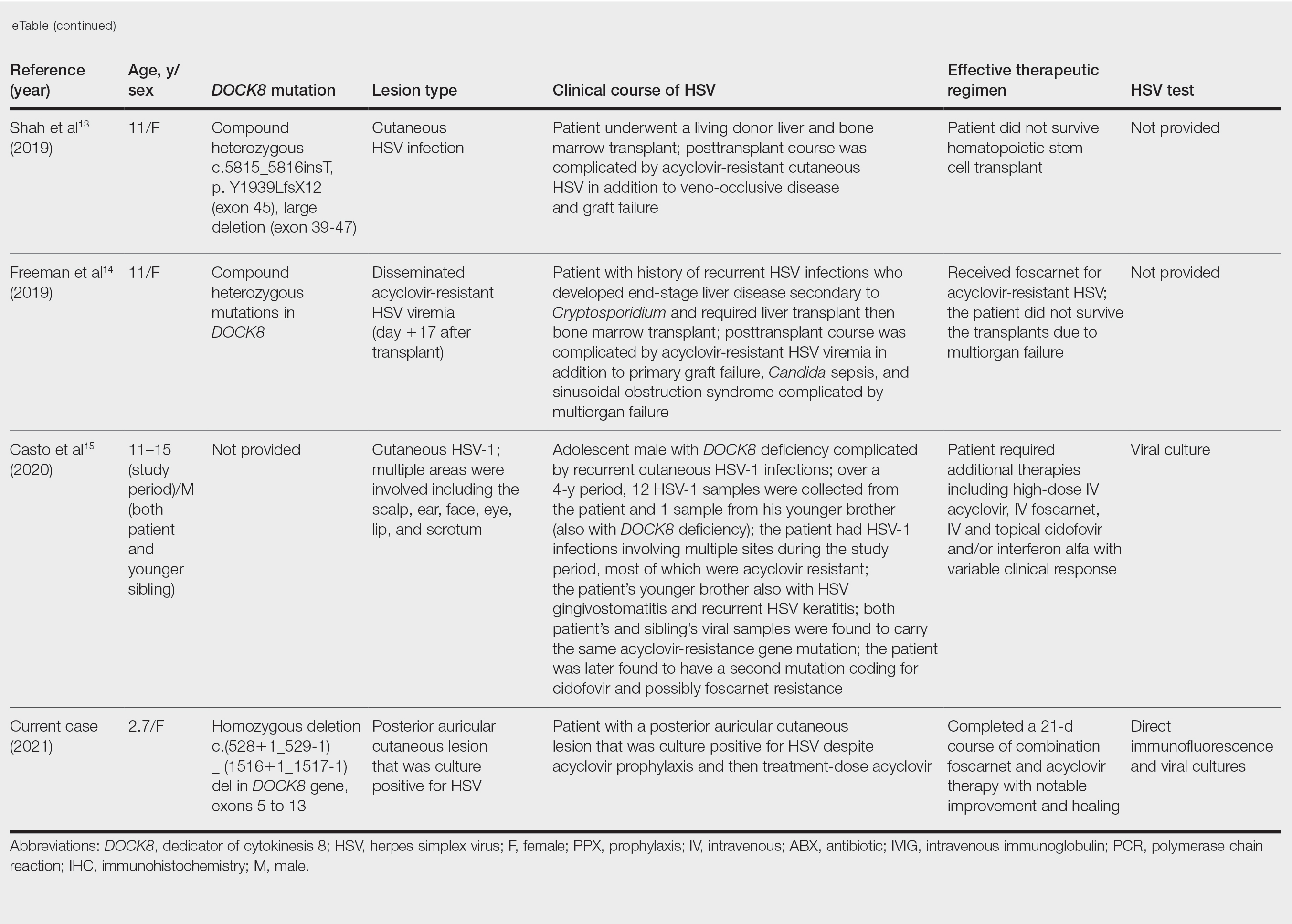

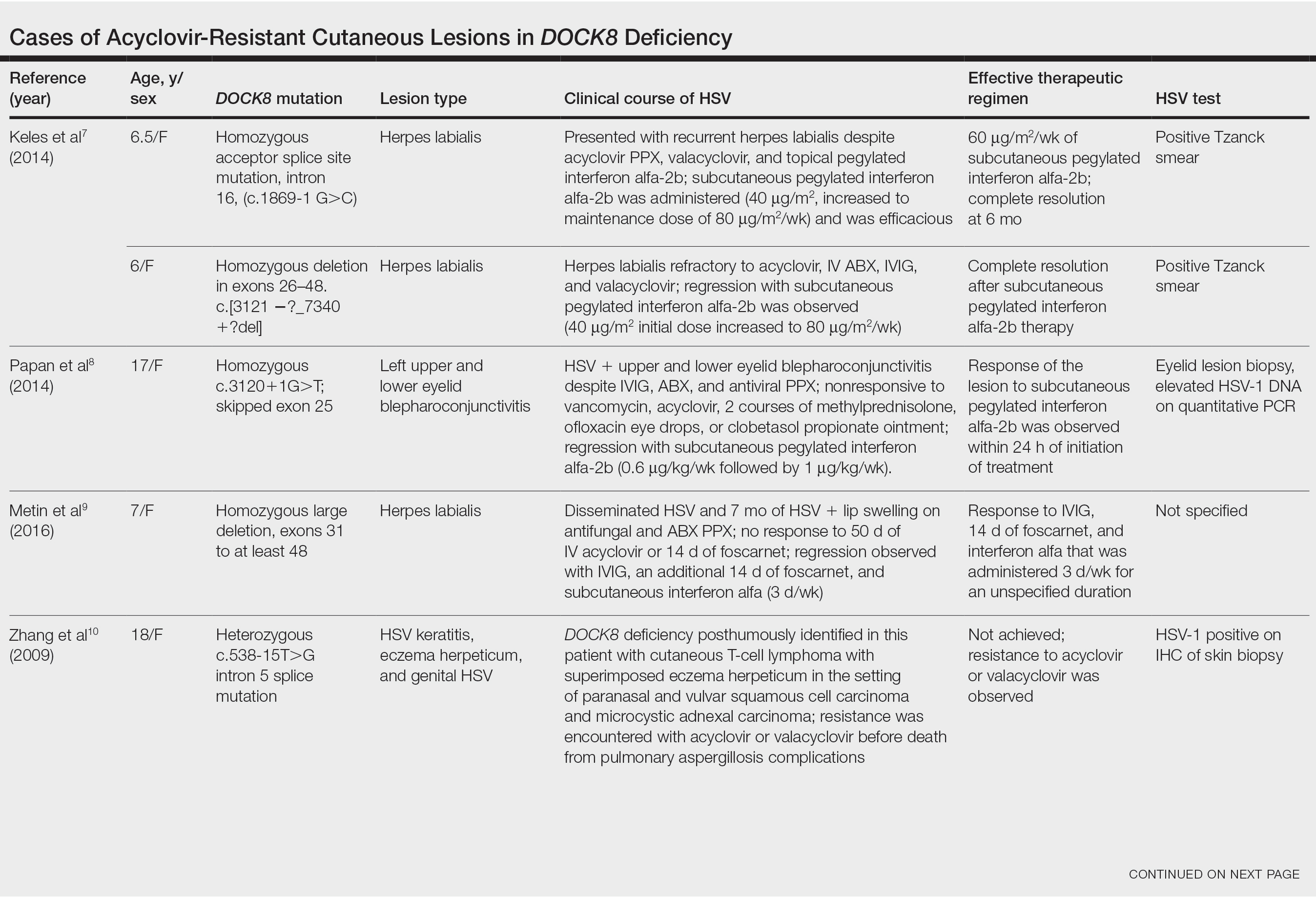

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8 ) deficiency is the major cause of autosomal-recessive hyper-IgEsyndrome. 1 Characteristic clinical features including eosinophilia, eczema, and recurrent Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous and respiratory tract infections are common in DOCK8 deficiency, similar to the autosomal-dominant form of hyper-IgE syndrome that is due to defi c iency of signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT-3 ). 1 In addition, patients with DOCK8 deficiency are particularly susceptible to asthma; food allergies; lymphomas; and severe cutaneous viral infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), molluscum contagiosum, varicella-zoster virus, and human papillomavirus. Since the discovery of the DOCK8 gene in 2009, various studies have sought to elucidate the mechanistic contribution of DOCK8 to the dermatologic immune environment. 2 Although cutaneous viral infections such as those caused by HSV typically are short lived and self-limiting in immunocompetent hosts, they have proven to be severe and recalcitrant in the setting of DOCK8 deficiency. 1 Herein, we report the case of a 32-month-old girl with homozygous DOCK8 deficiency who developed acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV.

Case Report

A 32-month-old girl presented with an approximately 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus at month 9 of a hospital stay for recurrent infections. Her medical history was notable for multiple upper respiratory tract infections, diffuse eczema, and food allergies. She had presented to an outside hospital at 14 months of age with herpetic gingivostomatitis and eczema herpeticum that was successfully treated with acyclovir. She was readmitted at 20 months of age due to Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, pancytopenia, and disseminated histoplasmosis. Prophylactic oral acyclovir (20 mg/kg twice daily) was started, given her history of HSV infection. Because of recurrent infections, she underwent an immunodeficiency workup. Whole exome sequencing analysis revealed a homozygous deletion c.(528+1_529−1)_(1516+1_1517−1)del in DOCK8 gene–affecting exons 5 to 13. The patient was transferred to our hospital for continued care and as a potential candidate for bone marrow transplant following resolution of the disseminated histoplasmosis infection.

During her hospitalization at the current presentation, she was noted to have a 2-cm linear erosion along the left posterior auricular sulcus. Initial wound care with bacitracin ointment was applied to the area while specimens were obtained and empiric oral acyclovir therapy was initiated (20 mg/kg 4 times daily [QID]), given a clinical impression consistent with cutaneous HSV infection despite acyclovir prophylaxis. Direct immunofluorescence and viral cultures were positive for HSV-1, while bacterial cultures grew methicillin-susceptible S aureus. Cephalexin and mupirocin ointment were started, and acyclovir was continued. After 2 weeks of therapy, there was no visible change in the wound; cultures were repeated, again showing the wound contained HSV. Bacterial cultures this time grew Pseudomonas putida, and the antibiotic regimen was transitioned to cefepime.

After no response to the continued course of therapeutic acyclovir, HSV cultures were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for resistance testing, and biopsy of the lesion was performed by the otolaryngology service to rule out malignancy and potential alternative diagnoses. Histopathology showed only reactive inflammation without visible microorganisms on tissue HSV-1/HSV-2 immunostain; however, tissue viral culture was positive for HSV-1. The patient was transitioned back to acyclovir (intravenous [IV] 20 mg/kg QID) with the addition of empiric foscarnet (IV 40 mg/kg 3 times daily) given the worsening appearance of the lesion. The HSV acyclovir resistance test results from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention returned soon after and were positive for resistance (median infectious dose, 3.29 µg/L [reference interval, sensitive <2.00 µg/L; resistant >1.90 µg/L]). The patient completed a 21-day course of combination foscarnet and acyclovir therapy, during which time the lesion showed notable improvement and healing. The patient was continued on prophylactic acyclovir (IV 20 mg/kg QID). Unfortunately, the patient eventually died due to complications related to pneumonia.

Comment

Infection in Patients With DOCK8 Deficiency—The gene DOCK8 has emerged as playing a central role in both innate and adaptive immunity, as it is expressed primarily in immune cells and serves as a mediator of numerous processes, including immune synapse formation, cell signaling and trafficking, antibody and cytokine production, and lymphocyte memory.3 Cells that are critical for combating cutaneous viral infections, including skin-resident memory T cells and natural killer cells, are defective, which leads to a severely immunocompromised state in DOCK8-deficient patients with a particular susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory dermatologic disease.4

Herpes simplex virus infection commonly is seen in DOCK8 deficiency, with retrospective analysis of a DOCK8-deficient cohort revealing HSV infection in approximately 38% of patients.5 Prophylactic acyclovir is essential for DOCK8-deficient individuals with a history of HSV infection given the tendency of the virus to reactivate.6 However, despite prophylaxis, our patient developed an HSV-positive posterior auricular erosion that continued to progress even after increase of the acyclovir dose. Acyclovir resistance testing of the HSV isolated from the wound was positive, confirming the clinical suspicion of the presence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.

Acyclovir-Resistant HSV—Acyclovir-resistant HSV in immunosuppressed individuals was first noted in 1982, and most cases since then have occurred in the setting of AIDS and in organ transplant recipients.6 Few reports of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8 deficiency exist, and to our knowledge, our patient is the youngest DOCK8-deficient individual to be documented with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection.1,7-15 We identified relevant cases from the PubMed and EMBASE databases using the search terms DOCK8 deficiency and acyclovir and DOCK8 deficiency and herpes. The eTable lists other reported cases of acyclovir-resistant HSV in DOCK8-deficient patients. The majority of cases involved school-aged females. Lesion types varied and included herpes labialis, eczema herpeticum, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Escalation of therapy and resolution of the lesion was seen in some cases with administration of subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b.

Treatment Alternatives—Acyclovir competitively inhibits viral DNA polymerase by incorporating into elongating viral DNA strands and halting chain synthesis. Acyclovir requires triphosphorylation for activation, and viral thymidine kinase is responsible for the first phosphorylation event. Ninety-five percent of cases of acyclovir resistance are secondary to mutations in viral thymidine kinase. Foscarnet also inhibits viral DNA polymerase but does so directly without the need to be phosphorylated first.6 For this reason, foscarnet often is the drug of choice in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV, as evidenced in our patient. However, foscarnet-resistant HSV strains may develop from mutations in the DNA polymerase gene.

Cidofovir is a nucleotide analogue that requires phosphorylation by host, as opposed to viral, kinases for antiviral activity. Intravenous and topical formulations of cidofovir have proven effective in the treatment of acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant HSV lesions.6 Cidofovir also can be applied intralesionally, a method that provides targeted therapy and minimizes cidofovir-associated nephrotoxicity.12 Reports of systemic interferon alfa therapy for acyclovir-resistant HSV also exist. A study found IFN-⍺ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in DOCK8-deficient individuals to be significantly reduced relative to controls (P<.05).7 There has been complete resolution of acyclovir-resistant HSV lesions with subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b injections in several DOCK8-deficient patients.7-9

The need for escalating therapy in DOCK8-deficient individuals with acyclovir-resistant HSV infection underscores the essential role of DOCK8 in dermatologic immunity. Our case demonstrates that a high degree of suspicion for cutaneous HSV infection should be adopted in DOCK8-deficient patients of any age, regardless of acyclovir prophylaxis. Viral culture in addition to bacterial cultures should be performed early in patients with cutaneous erosions, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low to minimize morbidity associated with these infections. Early resistance testing in our case could have prevented prolongation of infection and likely eliminated the need for a biopsy.

Conclusion

DOCK8 deficiency presents a unique challenge to dermatologists and other health care providers given the susceptibility of affected individuals to developing a reservoir of severe and potentially resistant viral cutaneous infections. Prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression, even in the youngest of patients, and suspicion for resistance should be high to avoid delays in adequate treatment.

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

- Chu EY, Freeman AF, Jing H, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:79-84. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.262

- Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options—a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:189-198. doi:10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0

- Kearney CJ, Randall KL, Oliaro J. DOCK8 regulates signal transduction events to control immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2017;14:406-411. doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.9

- Zhang Q, Dove CG, Hor JL, et al. DOCK8 regulates lymphocyte shape integrity for skin antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2549-2566. doi:10.1084/jem.20141307

- Engelhardt KR, Gertz EM, Keles S, et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with DOCK8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945

- Chilukuri S, Rosen T. Management of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:311-320. doi:10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00093-1

- Keles S, Jabara HH, Reisli I, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell depletion in DOCK8 deficiency: rescue of severe herpetic infections with interferon alpha-2b therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1753-1755.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.032

- Papan C, Hagl B, Heinz V, et al Beneficial IFN-α treatment of tumorous herpes simplex blepharoconjunctivitis in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1456-1458. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.008

- Metin A, Kanik-Yuksek S, Ozkaya-Parlakay A, et al. Giant herpes labialis in a child with DOCK8-deficient hyper-IgE syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:79-80. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.04.011

- Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046-2055. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0905506

- Lei JY, Wang Y, Jaffe ES, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma associated with primary immunodeficiency, recurrent diffuse herpes simplex virus infection, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:524-529. doi:10.1097/00000372-200012000-00008

- Castelo-Soccio L, Bernardin R, Stern J, et al. Successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus with intralesional cidofovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:124-126. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.363

- Shah NN, Freeman AF, Hickstein DD. Addendum to: haploidentical related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:E65-E67. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.11.014

- Freeman AF, Yazigi N, Shah NN, et al. Tandem orthotopic living donor liver transplantation followed by same donor haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for DOCK8 deficiency. Transplantation. 2019;103:2144-2149. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000002649

- Casto AM, Stout SC, Selvarangan R, et al. Evaluation of genotypic antiviral resistance testing as an alternative to phenotypic testing in a patient with DOCK8 deficiency and severe HSV-1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:2035-2042. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa020

Practice Points

- Patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 ( DOCK 8 ) deficiency are susceptible to development of severe recalcitrant viral cutaneous infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Dermatologists should be aware that prophylactic acyclovir may not be sufficient for HSV suppression in the setting of severe immunodeficiency.

- Acyclovir-resistant cutaneous HSV lesions require escalation of therapy, which may include addition of foscarnet, cidofovir, or subcutaneous pegylated interferon alfa-2b to the therapeutic regimen.

- Viral culture should be performed on suspicious lesions in DOCK 8 -deficient patients despite acyclovir prophylaxis, and the threshold for HSV resistance testing should be low.

Women with recurrent UTIs express fear, frustration

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.