User login

Expected spike in acute flaccid myelitis did not occur in 2020

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

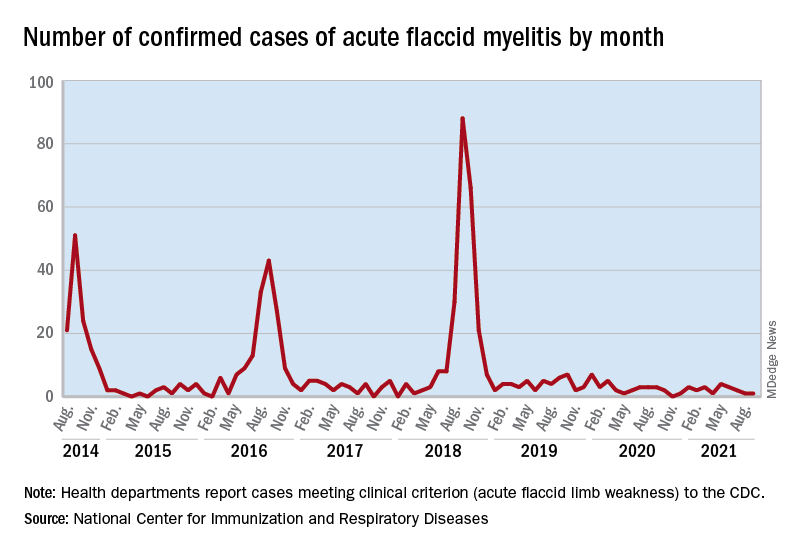

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

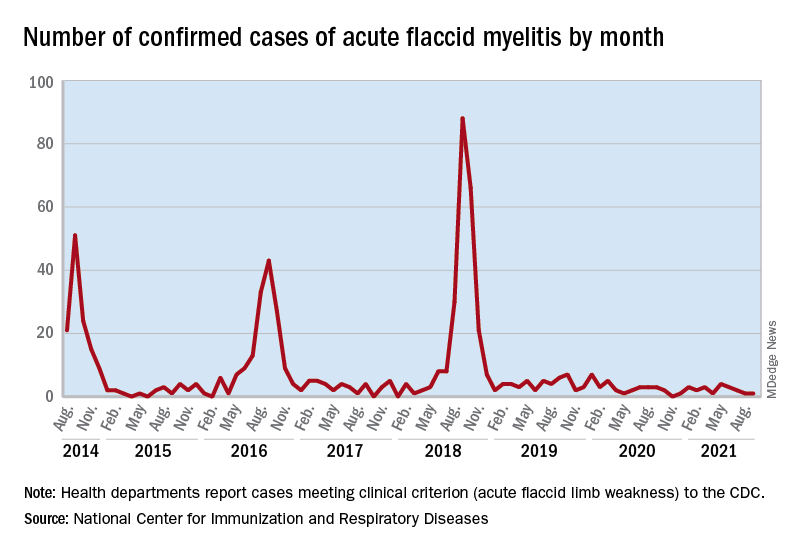

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

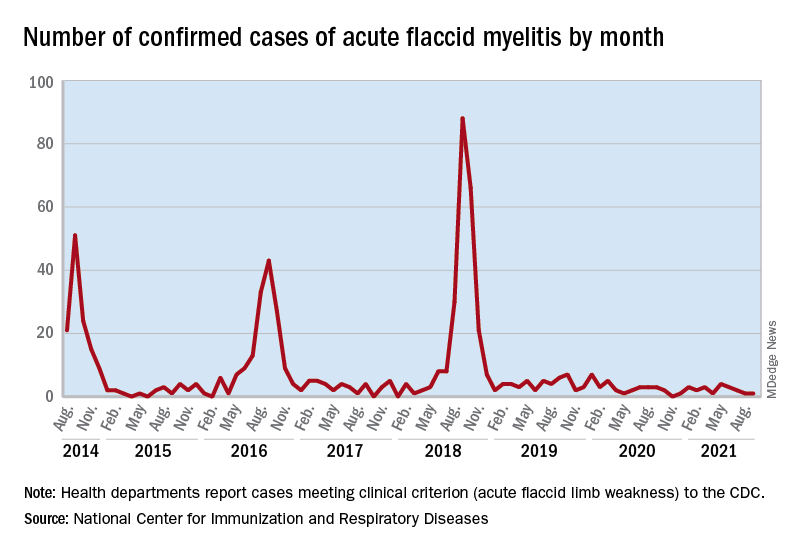

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

Does zinc really help treat colds?

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Maraviroc, metformin fail to control NAFLD in people with HIV

The MAVMET study, the first randomized controlled trial of – and in some cases, prolonged use actually increased liver fat.

And that means clinicians like Yvonne Gilleece, MB BCh, who was not involved in the study but does run a liver clinic in England for people living with HIV, are returning to the one intervention proven to work. “As yet, the only thing that is proven to have a very positive effect that is published is weight loss,” said Dr. Gilleece, who runs the clinic at Brighton and Sussex University Hospital. “You don’t put someone on these particular drugs, particularly this combination, easily. MAVMET has really demonstrated that, actually, it’s not effective, and it’s not particularly beneficial to patients.”

The MAVMET trial data was presented at the 18th European AIDS Conference,

There was good reason to think maraviroc might work. A 2018 study in the journal Hepatology found that one of maraviroc’s molecular cousins, cenicriviroc, significantly reduced fibrosis in people with NAFLD. Dr. Gilleece is co-investigator of another study of maraviroc in NAFLD, the HEPMARC trial, which is wrapping up now. In addition to those studies, there are other potential treatments in ongoing trials, including semaglutide, which is being studied in the United States under the study name SLIM LIVER.

MAVMET enrolled 90 people living with HIV from six clinical sites in London who were 35 or older and who had at least one marker for NAFLD, such as abnormal liver lab results. But 70% qualified via imaging- and/or biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. Almost all participants (93%) were men and 81% were White. The trial excluded people who were pregnant or breastfeeding. The median age was 52, and the participants met the criteria for overweight but not obesity, with a median BMI of 28.

In other words, participants generally had fatty livers without the inflammation that characterizes the more aggressive nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Clinicians can’t yet differentiate between those who will continue to have asymptomatic fatty liver and those who will progress to NASH and potentially need a liver transplant.

All people living with HIV in the trial had undetectable viral loads and were on HIV treatment. Nearly 1 in 5 (19%) were using a treatment regimen containing tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), which has been associated with weight gain. Nearly half were on integrase strand inhibitors.

Investigators divided the participants up into four groups: 24 people stayed on their HIV treatment and added nothing else; 23 people took maraviroc only; 21 took metformin only; and the final group took both maraviroc and metformin. Across groups, liver fat at baseline was 8.9%, and 78% had mild hepatic steatosis.

After taking the medications for 48 weeks, participants returned to clinic to be scanned via MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), which has been found to successfully measure liver fat. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 20 of the 83 people who returned to the clinic came later than 48 weeks after the trial began.

When investigators looked at the results, they didn’t see what they hypothesized, said Sarah Pett, professor of infectious diseases at University College, London: The scatter plot graph of change in weight looked, well, scattershot: People who didn’t take any additional treatment sometimes lost more liver fat than those on treatment. In fact, the mean liver fat percentage rose by 2.2% in the maraviroc group, 1.3% in the metformin group, and 0.8% in the combination group. The control group saw an increase of 1.4% – meaning that there was no difference between the change in fat between those on treatment and those not.

What’s more, those who had delayed scans – and stayed on their treatment for a median of an additional 16 weeks – saw their liver fat increase even more.

In an interview, Dr. Pett called the results “disappointing.” “The numbers are quite small, but we still didn’t expect this,” she said. “It’s not explained by lockdown weight gain, although we still have to look in detail at how alcohol consumption could have contributed.”

There were also some limits to what the design of this particular trial could tell the researchers. For instance, nearly half of the participants in the maraviroc group, a third of the people in the metformin group, and 36% of those in the combination group had hepatic steatosis grades of 0, meaning that their livers were healthy. And MRI-PDFF becomes less reliable at that level.

“One of the regrets is that perhaps we should have done FibroScan [ultrasound], as well,” Dr. Pett said. The consequence is that the study may have undercounted the fat level by using MRI-PFDD.

“This suggests that the surrogate markers of NAFLD used in MAVMET were not very sensitive to those with a higher percentage of fat,” Dr. Pett said during her presentation. “We were really trying to be pragmatic and not require an MRI at screening.”

Whatever the case, she said that the failure of this particular treatment just highlights the growing need to look more seriously, and more collaboratively, at fat and liver health in people living with HIV.

“We need to really focus on setting up large cohorts of people living with HIV to look in a rigorous way at weight gain, changes in waist circumference, ectopic fat, capture fatty liver disease index scores, and cardiovascular risk, to acquire some longitudinal data,” she said. “And [we need to] join with our fellow researchers in overweight and obesity medicine and hepatology to make sure that people living with HIV are included in new treatments for NASH, as several large RCTs have excluded [people living with HIV].”

From Dr. Gilleece’s perspective, it also just speaks to how far the field has to go in identifying those with asymptomatic fatty livers from those who will progress to fibrosis and potentially need liver transplants.

“MAVMET shows the difficulty in managing NAFLD,” she said. “It seems quite an innocuous disease, because for the majority of people it’s not going to cause a problem in their lifetime. But the reality is, for some it will, and we don’t really know how to treat it.”

Dr. Gilleece has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pett reported receiving funding for trials from Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag. ViiV Healthcare funded the MAVMET trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The MAVMET study, the first randomized controlled trial of – and in some cases, prolonged use actually increased liver fat.

And that means clinicians like Yvonne Gilleece, MB BCh, who was not involved in the study but does run a liver clinic in England for people living with HIV, are returning to the one intervention proven to work. “As yet, the only thing that is proven to have a very positive effect that is published is weight loss,” said Dr. Gilleece, who runs the clinic at Brighton and Sussex University Hospital. “You don’t put someone on these particular drugs, particularly this combination, easily. MAVMET has really demonstrated that, actually, it’s not effective, and it’s not particularly beneficial to patients.”

The MAVMET trial data was presented at the 18th European AIDS Conference,

There was good reason to think maraviroc might work. A 2018 study in the journal Hepatology found that one of maraviroc’s molecular cousins, cenicriviroc, significantly reduced fibrosis in people with NAFLD. Dr. Gilleece is co-investigator of another study of maraviroc in NAFLD, the HEPMARC trial, which is wrapping up now. In addition to those studies, there are other potential treatments in ongoing trials, including semaglutide, which is being studied in the United States under the study name SLIM LIVER.

MAVMET enrolled 90 people living with HIV from six clinical sites in London who were 35 or older and who had at least one marker for NAFLD, such as abnormal liver lab results. But 70% qualified via imaging- and/or biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. Almost all participants (93%) were men and 81% were White. The trial excluded people who were pregnant or breastfeeding. The median age was 52, and the participants met the criteria for overweight but not obesity, with a median BMI of 28.

In other words, participants generally had fatty livers without the inflammation that characterizes the more aggressive nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Clinicians can’t yet differentiate between those who will continue to have asymptomatic fatty liver and those who will progress to NASH and potentially need a liver transplant.

All people living with HIV in the trial had undetectable viral loads and were on HIV treatment. Nearly 1 in 5 (19%) were using a treatment regimen containing tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), which has been associated with weight gain. Nearly half were on integrase strand inhibitors.

Investigators divided the participants up into four groups: 24 people stayed on their HIV treatment and added nothing else; 23 people took maraviroc only; 21 took metformin only; and the final group took both maraviroc and metformin. Across groups, liver fat at baseline was 8.9%, and 78% had mild hepatic steatosis.

After taking the medications for 48 weeks, participants returned to clinic to be scanned via MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), which has been found to successfully measure liver fat. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 20 of the 83 people who returned to the clinic came later than 48 weeks after the trial began.

When investigators looked at the results, they didn’t see what they hypothesized, said Sarah Pett, professor of infectious diseases at University College, London: The scatter plot graph of change in weight looked, well, scattershot: People who didn’t take any additional treatment sometimes lost more liver fat than those on treatment. In fact, the mean liver fat percentage rose by 2.2% in the maraviroc group, 1.3% in the metformin group, and 0.8% in the combination group. The control group saw an increase of 1.4% – meaning that there was no difference between the change in fat between those on treatment and those not.

What’s more, those who had delayed scans – and stayed on their treatment for a median of an additional 16 weeks – saw their liver fat increase even more.

In an interview, Dr. Pett called the results “disappointing.” “The numbers are quite small, but we still didn’t expect this,” she said. “It’s not explained by lockdown weight gain, although we still have to look in detail at how alcohol consumption could have contributed.”

There were also some limits to what the design of this particular trial could tell the researchers. For instance, nearly half of the participants in the maraviroc group, a third of the people in the metformin group, and 36% of those in the combination group had hepatic steatosis grades of 0, meaning that their livers were healthy. And MRI-PDFF becomes less reliable at that level.

“One of the regrets is that perhaps we should have done FibroScan [ultrasound], as well,” Dr. Pett said. The consequence is that the study may have undercounted the fat level by using MRI-PFDD.

“This suggests that the surrogate markers of NAFLD used in MAVMET were not very sensitive to those with a higher percentage of fat,” Dr. Pett said during her presentation. “We were really trying to be pragmatic and not require an MRI at screening.”

Whatever the case, she said that the failure of this particular treatment just highlights the growing need to look more seriously, and more collaboratively, at fat and liver health in people living with HIV.

“We need to really focus on setting up large cohorts of people living with HIV to look in a rigorous way at weight gain, changes in waist circumference, ectopic fat, capture fatty liver disease index scores, and cardiovascular risk, to acquire some longitudinal data,” she said. “And [we need to] join with our fellow researchers in overweight and obesity medicine and hepatology to make sure that people living with HIV are included in new treatments for NASH, as several large RCTs have excluded [people living with HIV].”

From Dr. Gilleece’s perspective, it also just speaks to how far the field has to go in identifying those with asymptomatic fatty livers from those who will progress to fibrosis and potentially need liver transplants.

“MAVMET shows the difficulty in managing NAFLD,” she said. “It seems quite an innocuous disease, because for the majority of people it’s not going to cause a problem in their lifetime. But the reality is, for some it will, and we don’t really know how to treat it.”

Dr. Gilleece has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pett reported receiving funding for trials from Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag. ViiV Healthcare funded the MAVMET trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The MAVMET study, the first randomized controlled trial of – and in some cases, prolonged use actually increased liver fat.

And that means clinicians like Yvonne Gilleece, MB BCh, who was not involved in the study but does run a liver clinic in England for people living with HIV, are returning to the one intervention proven to work. “As yet, the only thing that is proven to have a very positive effect that is published is weight loss,” said Dr. Gilleece, who runs the clinic at Brighton and Sussex University Hospital. “You don’t put someone on these particular drugs, particularly this combination, easily. MAVMET has really demonstrated that, actually, it’s not effective, and it’s not particularly beneficial to patients.”

The MAVMET trial data was presented at the 18th European AIDS Conference,

There was good reason to think maraviroc might work. A 2018 study in the journal Hepatology found that one of maraviroc’s molecular cousins, cenicriviroc, significantly reduced fibrosis in people with NAFLD. Dr. Gilleece is co-investigator of another study of maraviroc in NAFLD, the HEPMARC trial, which is wrapping up now. In addition to those studies, there are other potential treatments in ongoing trials, including semaglutide, which is being studied in the United States under the study name SLIM LIVER.

MAVMET enrolled 90 people living with HIV from six clinical sites in London who were 35 or older and who had at least one marker for NAFLD, such as abnormal liver lab results. But 70% qualified via imaging- and/or biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. Almost all participants (93%) were men and 81% were White. The trial excluded people who were pregnant or breastfeeding. The median age was 52, and the participants met the criteria for overweight but not obesity, with a median BMI of 28.

In other words, participants generally had fatty livers without the inflammation that characterizes the more aggressive nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Clinicians can’t yet differentiate between those who will continue to have asymptomatic fatty liver and those who will progress to NASH and potentially need a liver transplant.

All people living with HIV in the trial had undetectable viral loads and were on HIV treatment. Nearly 1 in 5 (19%) were using a treatment regimen containing tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), which has been associated with weight gain. Nearly half were on integrase strand inhibitors.

Investigators divided the participants up into four groups: 24 people stayed on their HIV treatment and added nothing else; 23 people took maraviroc only; 21 took metformin only; and the final group took both maraviroc and metformin. Across groups, liver fat at baseline was 8.9%, and 78% had mild hepatic steatosis.

After taking the medications for 48 weeks, participants returned to clinic to be scanned via MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), which has been found to successfully measure liver fat. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 20 of the 83 people who returned to the clinic came later than 48 weeks after the trial began.

When investigators looked at the results, they didn’t see what they hypothesized, said Sarah Pett, professor of infectious diseases at University College, London: The scatter plot graph of change in weight looked, well, scattershot: People who didn’t take any additional treatment sometimes lost more liver fat than those on treatment. In fact, the mean liver fat percentage rose by 2.2% in the maraviroc group, 1.3% in the metformin group, and 0.8% in the combination group. The control group saw an increase of 1.4% – meaning that there was no difference between the change in fat between those on treatment and those not.

What’s more, those who had delayed scans – and stayed on their treatment for a median of an additional 16 weeks – saw their liver fat increase even more.

In an interview, Dr. Pett called the results “disappointing.” “The numbers are quite small, but we still didn’t expect this,” she said. “It’s not explained by lockdown weight gain, although we still have to look in detail at how alcohol consumption could have contributed.”

There were also some limits to what the design of this particular trial could tell the researchers. For instance, nearly half of the participants in the maraviroc group, a third of the people in the metformin group, and 36% of those in the combination group had hepatic steatosis grades of 0, meaning that their livers were healthy. And MRI-PDFF becomes less reliable at that level.

“One of the regrets is that perhaps we should have done FibroScan [ultrasound], as well,” Dr. Pett said. The consequence is that the study may have undercounted the fat level by using MRI-PFDD.

“This suggests that the surrogate markers of NAFLD used in MAVMET were not very sensitive to those with a higher percentage of fat,” Dr. Pett said during her presentation. “We were really trying to be pragmatic and not require an MRI at screening.”

Whatever the case, she said that the failure of this particular treatment just highlights the growing need to look more seriously, and more collaboratively, at fat and liver health in people living with HIV.

“We need to really focus on setting up large cohorts of people living with HIV to look in a rigorous way at weight gain, changes in waist circumference, ectopic fat, capture fatty liver disease index scores, and cardiovascular risk, to acquire some longitudinal data,” she said. “And [we need to] join with our fellow researchers in overweight and obesity medicine and hepatology to make sure that people living with HIV are included in new treatments for NASH, as several large RCTs have excluded [people living with HIV].”

From Dr. Gilleece’s perspective, it also just speaks to how far the field has to go in identifying those with asymptomatic fatty livers from those who will progress to fibrosis and potentially need liver transplants.

“MAVMET shows the difficulty in managing NAFLD,” she said. “It seems quite an innocuous disease, because for the majority of people it’s not going to cause a problem in their lifetime. But the reality is, for some it will, and we don’t really know how to treat it.”

Dr. Gilleece has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pett reported receiving funding for trials from Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag. ViiV Healthcare funded the MAVMET trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ACIP recommends universal HBV vaccination for adults under 60, expands recommendations for vaccines against orthopoxviruses and Ebola

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group also voted to expand recommendations for vaccinating people at risk for occupational exposure to Ebola and to recommend Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, for at-risk populations.

The recommendations were approved Nov. 3.

Previously, ACIP recommended HBV vaccination for unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection because of sexual exposure, percutaneous or mucosal exposure to blood, hepatitis C infection, chronic liver disease, end-stage renal disease, HIV infection, and travel to areas with high to intermediate levels of HBV infection. But experts agreed a new strategy was needed, as previously falling rates of HBV have plateaued. “The past decade has illustrated that risk-based screening has got us as far as it can take us,” Mark Weng, MD, a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Public Health Service and lead of the ACIP Hepatitis Vaccine Working Group, said during the meeting.

There are 1.9 million people living with chronic HBV in the United States, with over 20,000 new acute infections every year. Rates are highest among those in their 40s and 50s, Dr. Weng noted.

The group debated whether to apply the universal recommendation to all ages, but in a close vote (eight yes, seven no), ACIP included an age cutoff of 59. The majority argued that adults 60 and older are at lower risk for infection and vaccination efforts targeting younger adults would be more effective. Those 60 and older would continue to follow the risk-based guidelines, but anyone, regardless of age, can receive the vaccine if they wish to be protected, the group added.

The CDC director as well as several professional societies need to approve the recommendation before it becomes public policy.

ACIP also voted to recommend the following:

- Adding updated recommendations to the 2022 immunization schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, including dengue vaccination for children aged 9-16 years in endemic areas and in adults over 65 and those aged 19-64 with certain chronic conditions.

- The use of Jynneos, a smallpox and monkeypox vaccine, as an alternative to ACAM2000 for those at risk for occupational exposure.

- Pre-exposure vaccination of health care personnel involved in the transport and treatment of suspected Ebola patients at special treatment centers, or lab and support staff working with or handling specimens that may contain the Ebola virus.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HIV prescription mandate controversy reaches the Supreme Court

A firestorm of controversy over access to HIV medications and protection against discriminatory insurance practices has been making its way through U.S. district courts for the past 3 years, pitting HIV patients against pharmacy benefits managers and, ostensibly, the healthcare industry itself.

.

At odds are whether or not mandatory mail-order requirements for specialty medications violate specific provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, both of which prohibit discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

An amicus brief submitted on October 29 by the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI) of Harvard Law School on behalf of five John Does and a number of medical practitioners and practitioner organizations underscores the degree to which advances in HIV treatment, viral suppression, and care linkage — not to mention the national mandate to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 — might ultimately be affected.

“We decided to file the brief at the Supreme Court level because we wanted to make sure that the perspectives of people living with HIV, their providers, and advocates were in the record,” Maryanne Tomazic, a clinical instructor at CHLPI, toldthis news organization.

“It’s important for the court to consider why robust access to prescription drug coverage and pharmacy services are so important for people living with HIV, and why it’s not appropriate to compromise access to antiretroviral therapy,” she explained.

A bitter pill, regardless of who swallows it

CVS Pharmacy Inc. v. Doe focuses on a legal concept known as “disparate impact discrimination,” which refers to a policy that appears neutral but unintentionally discriminates against a protected class of people (eg, on the basis of sex, age, or ethnicity).

The Supreme Court’s decision in the case will address a central question: did CVS Pharmacy, Caremark, and Caremark Specialty Pharmacy (“CVS”) discriminate against the respondents by requiring that they obtain specialty medications (including those for HIV) by mail order or drop shipment for pickup, or, alternatively, pay out-of-network prices for these medications at non-CVS pharmacies?

The decision will also address whether the ACA’s inclusion of clause 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits protected class discrimination, allows patients to challenge terms and conditions of their healthcare plans, a decision that has broad and far-reaching implications for insurers’ abilities to set plan restrictions and pricing.

A spokesperson for CVS declined to comment when contacted by this news organization but provided a link to an April 9, 2021 SCOTUS blog post about the filing. In its court filing, CVS contended that the program applies to all specialty medications (not just HIV) and simply reflects the cost/complexity of specialty medications.

Not everyone agrees that cost is the most important issue at play. Indeed, a critical take-away for practitioners is how mandated mail-order pharmacy programs can disrupt coordination of care.

“In the traditional model, the physician is talking to the pharmacists [or] talking with the patient, and you have kind of triangular communication model that helps not only the patient stay engaged in care but [also] allows the healthcare provider team to adjust the medication quickly without delay,” said Ms. Tomazic.

The John Doe statements in the original case highlight these concerns. They focus on how mandatory mail orders restrict highly personable relationships with local specialty pharmacists who are familiar with their patients’ medical histories as well as their medication dosing and adjustments and who regularly communicate with the complete care team on the patients’ behalf.

“JOHN DOE THREE and others depend on these types of long standing relationships with local pharmacists to maximize the benefits of HIV/AIDS medications and treat the complex and ever-changing needs of the HIV/AIDS patients,” wrote attorneys in the 2018 class action filing.

Other issues raised by the suit involve the following: privacy with respect to medication pickup; specialty care customer representatives’ lack of understanding and knowledge of HIV medications; incomplete prescription fills; late medication deliveries; exposure of medications to the elements; work and employment interruptions; and restrictions on early fills and reorders, which increase the risk for missed doses and potentially serious health problems, including interruptions in viral suppression and resistance.

Discrimination issues also raised

CHLPI’s amicus joins several others in support of the unique needs of persons with HIV, especially in Black and Hispanic/Latino communities, which are disproportionately affected by HIV.

A press release distributed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) reinforces the idea that not only are Black people more likely to have a disability other groups, owing to the country’s legacy of racial inequality, but also that they are likely to encounter unique forms of discrimination and specific barriers to full participation in society, further underscoring the need for disparate impact liability to address unfair policies and practices.

“Inequity in access to resources, including healthcare, further amplifies the instance and persistence of disabilities among Black people,” LDF attorneys wrote in the brief.

“We saw with COVID-19 that [mail-order prescription] programs can serve in a supportive role in access to care,” said Ms. Tomazic. “But we don’t want those programs to be mandated, and we don’t want to forget about communities where these kinds of programs are simply not a viable option,” she said.

Oral arguments in the case begin on December 7. A decision is expected some months later.

No relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A firestorm of controversy over access to HIV medications and protection against discriminatory insurance practices has been making its way through U.S. district courts for the past 3 years, pitting HIV patients against pharmacy benefits managers and, ostensibly, the healthcare industry itself.

.

At odds are whether or not mandatory mail-order requirements for specialty medications violate specific provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, both of which prohibit discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

An amicus brief submitted on October 29 by the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI) of Harvard Law School on behalf of five John Does and a number of medical practitioners and practitioner organizations underscores the degree to which advances in HIV treatment, viral suppression, and care linkage — not to mention the national mandate to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 — might ultimately be affected.

“We decided to file the brief at the Supreme Court level because we wanted to make sure that the perspectives of people living with HIV, their providers, and advocates were in the record,” Maryanne Tomazic, a clinical instructor at CHLPI, toldthis news organization.

“It’s important for the court to consider why robust access to prescription drug coverage and pharmacy services are so important for people living with HIV, and why it’s not appropriate to compromise access to antiretroviral therapy,” she explained.

A bitter pill, regardless of who swallows it

CVS Pharmacy Inc. v. Doe focuses on a legal concept known as “disparate impact discrimination,” which refers to a policy that appears neutral but unintentionally discriminates against a protected class of people (eg, on the basis of sex, age, or ethnicity).

The Supreme Court’s decision in the case will address a central question: did CVS Pharmacy, Caremark, and Caremark Specialty Pharmacy (“CVS”) discriminate against the respondents by requiring that they obtain specialty medications (including those for HIV) by mail order or drop shipment for pickup, or, alternatively, pay out-of-network prices for these medications at non-CVS pharmacies?

The decision will also address whether the ACA’s inclusion of clause 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits protected class discrimination, allows patients to challenge terms and conditions of their healthcare plans, a decision that has broad and far-reaching implications for insurers’ abilities to set plan restrictions and pricing.

A spokesperson for CVS declined to comment when contacted by this news organization but provided a link to an April 9, 2021 SCOTUS blog post about the filing. In its court filing, CVS contended that the program applies to all specialty medications (not just HIV) and simply reflects the cost/complexity of specialty medications.

Not everyone agrees that cost is the most important issue at play. Indeed, a critical take-away for practitioners is how mandated mail-order pharmacy programs can disrupt coordination of care.

“In the traditional model, the physician is talking to the pharmacists [or] talking with the patient, and you have kind of triangular communication model that helps not only the patient stay engaged in care but [also] allows the healthcare provider team to adjust the medication quickly without delay,” said Ms. Tomazic.

The John Doe statements in the original case highlight these concerns. They focus on how mandatory mail orders restrict highly personable relationships with local specialty pharmacists who are familiar with their patients’ medical histories as well as their medication dosing and adjustments and who regularly communicate with the complete care team on the patients’ behalf.

“JOHN DOE THREE and others depend on these types of long standing relationships with local pharmacists to maximize the benefits of HIV/AIDS medications and treat the complex and ever-changing needs of the HIV/AIDS patients,” wrote attorneys in the 2018 class action filing.

Other issues raised by the suit involve the following: privacy with respect to medication pickup; specialty care customer representatives’ lack of understanding and knowledge of HIV medications; incomplete prescription fills; late medication deliveries; exposure of medications to the elements; work and employment interruptions; and restrictions on early fills and reorders, which increase the risk for missed doses and potentially serious health problems, including interruptions in viral suppression and resistance.

Discrimination issues also raised

CHLPI’s amicus joins several others in support of the unique needs of persons with HIV, especially in Black and Hispanic/Latino communities, which are disproportionately affected by HIV.

A press release distributed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) reinforces the idea that not only are Black people more likely to have a disability other groups, owing to the country’s legacy of racial inequality, but also that they are likely to encounter unique forms of discrimination and specific barriers to full participation in society, further underscoring the need for disparate impact liability to address unfair policies and practices.

“Inequity in access to resources, including healthcare, further amplifies the instance and persistence of disabilities among Black people,” LDF attorneys wrote in the brief.

“We saw with COVID-19 that [mail-order prescription] programs can serve in a supportive role in access to care,” said Ms. Tomazic. “But we don’t want those programs to be mandated, and we don’t want to forget about communities where these kinds of programs are simply not a viable option,” she said.

Oral arguments in the case begin on December 7. A decision is expected some months later.

No relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A firestorm of controversy over access to HIV medications and protection against discriminatory insurance practices has been making its way through U.S. district courts for the past 3 years, pitting HIV patients against pharmacy benefits managers and, ostensibly, the healthcare industry itself.

.

At odds are whether or not mandatory mail-order requirements for specialty medications violate specific provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, both of which prohibit discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

An amicus brief submitted on October 29 by the Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI) of Harvard Law School on behalf of five John Does and a number of medical practitioners and practitioner organizations underscores the degree to which advances in HIV treatment, viral suppression, and care linkage — not to mention the national mandate to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 — might ultimately be affected.

“We decided to file the brief at the Supreme Court level because we wanted to make sure that the perspectives of people living with HIV, their providers, and advocates were in the record,” Maryanne Tomazic, a clinical instructor at CHLPI, toldthis news organization.

“It’s important for the court to consider why robust access to prescription drug coverage and pharmacy services are so important for people living with HIV, and why it’s not appropriate to compromise access to antiretroviral therapy,” she explained.

A bitter pill, regardless of who swallows it

CVS Pharmacy Inc. v. Doe focuses on a legal concept known as “disparate impact discrimination,” which refers to a policy that appears neutral but unintentionally discriminates against a protected class of people (eg, on the basis of sex, age, or ethnicity).

The Supreme Court’s decision in the case will address a central question: did CVS Pharmacy, Caremark, and Caremark Specialty Pharmacy (“CVS”) discriminate against the respondents by requiring that they obtain specialty medications (including those for HIV) by mail order or drop shipment for pickup, or, alternatively, pay out-of-network prices for these medications at non-CVS pharmacies?

The decision will also address whether the ACA’s inclusion of clause 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which prohibits protected class discrimination, allows patients to challenge terms and conditions of their healthcare plans, a decision that has broad and far-reaching implications for insurers’ abilities to set plan restrictions and pricing.

A spokesperson for CVS declined to comment when contacted by this news organization but provided a link to an April 9, 2021 SCOTUS blog post about the filing. In its court filing, CVS contended that the program applies to all specialty medications (not just HIV) and simply reflects the cost/complexity of specialty medications.

Not everyone agrees that cost is the most important issue at play. Indeed, a critical take-away for practitioners is how mandated mail-order pharmacy programs can disrupt coordination of care.

“In the traditional model, the physician is talking to the pharmacists [or] talking with the patient, and you have kind of triangular communication model that helps not only the patient stay engaged in care but [also] allows the healthcare provider team to adjust the medication quickly without delay,” said Ms. Tomazic.

The John Doe statements in the original case highlight these concerns. They focus on how mandatory mail orders restrict highly personable relationships with local specialty pharmacists who are familiar with their patients’ medical histories as well as their medication dosing and adjustments and who regularly communicate with the complete care team on the patients’ behalf.

“JOHN DOE THREE and others depend on these types of long standing relationships with local pharmacists to maximize the benefits of HIV/AIDS medications and treat the complex and ever-changing needs of the HIV/AIDS patients,” wrote attorneys in the 2018 class action filing.

Other issues raised by the suit involve the following: privacy with respect to medication pickup; specialty care customer representatives’ lack of understanding and knowledge of HIV medications; incomplete prescription fills; late medication deliveries; exposure of medications to the elements; work and employment interruptions; and restrictions on early fills and reorders, which increase the risk for missed doses and potentially serious health problems, including interruptions in viral suppression and resistance.

Discrimination issues also raised

CHLPI’s amicus joins several others in support of the unique needs of persons with HIV, especially in Black and Hispanic/Latino communities, which are disproportionately affected by HIV.

A press release distributed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) reinforces the idea that not only are Black people more likely to have a disability other groups, owing to the country’s legacy of racial inequality, but also that they are likely to encounter unique forms of discrimination and specific barriers to full participation in society, further underscoring the need for disparate impact liability to address unfair policies and practices.

“Inequity in access to resources, including healthcare, further amplifies the instance and persistence of disabilities among Black people,” LDF attorneys wrote in the brief.

“We saw with COVID-19 that [mail-order prescription] programs can serve in a supportive role in access to care,” said Ms. Tomazic. “But we don’t want those programs to be mandated, and we don’t want to forget about communities where these kinds of programs are simply not a viable option,” she said.

Oral arguments in the case begin on December 7. A decision is expected some months later.

No relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 has brought more complex, longer office visits

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.