User login

Q&A: Meeting the challenge of giving COVID vaccines to younger kids

This news organization spoke to several pediatric experts to get answers.

More than 6 million children and adolescents (up to age 18 years) in the United States have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Children represent about 17% of all cases, and an estimated 0.1%-2% of infected children end up hospitalized, according to Oct. 28 data from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Physicians and other health care practitioners are gearing up for what could be an influx of patients. “Pediatricians are standing by to talk with families about the vaccine and to administer the vaccine to children as soon as possible,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, FAAP, president of the AAP, said in a statement.

In this Q&A, this news organization asked for additional advice from Sara “Sally” Goza, MD, a pediatrician in Fayetteville, Georgia, and immediate past president of the AAP; Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and codirector of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, both in Houston; and Danielle M. Zerr, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at the University of Washington, Seattle, and medical director of infection prevention at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Q: How are smaller pediatric practices and solo practitioners going to handle the additional vaccinations?

Dr. Goza: It’s a scheduling challenge with this rollout and all the people who want it and want it right now. They’re going to want it this week.

I’ve actually had some children asking their moms: “When can I get it? When can I get it?” It’s been very interesting – they are chomping at the bit.

If I give the vaccine to a patient this week, in 3 weeks the second dose will be right around Thanksgiving. No one in my office is going to want to be here to give the shot on Thanksgiving, and no patient is going to want to come in on Thanksgiving weekend. So I’m trying to delay those parents – saying, let’s do it next week. That way we’re not messing up a holiday.

Children are going to need two doses, and they won’t be fully protected until 2 weeks after their second dose. So they won’t get full protection for Thanksgiving, but they will have full protection for Christmas.

I know there are a lot of pediatricians who have preordered the vaccine. I know in our office they sent us an email ... to let us know our vaccines are being shipped. So I think a lot of pediatricians are going to have the vaccine.

Q: How should pediatricians counsel parents who are fearful or hesitant?

Dr. Hotez: It’s important to emphasize the severity of the 2021 summer Delta epidemic in children. We need to get beyond this false narrative that COVID only produces a mild disease in children. It’s caused thousands of pediatric hospitalizations, not to mention long COVID.

Dr. Zerr: It is key to find out what concerns parents have and then focus on answering their specific questions. It is helpful to emphasize the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and to explain the rigorous processes that the vaccine went through to receive Food and Drug Administration approval.

Q: How should pediatricians counter any misinformation/disinformation out there about the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: The most important thing is not to discount what they are saying. Don’t say: “That’s crazy” or “That’s not true.” Don’t roll your eyes and say: “Really, you’re going to believe all that?”

Instead, have a conversation with them about why we think that is not true, or why we know that’s not true. We really have to have that relationship and ask: “Well, what are your concerns?” And then really counter (any misinformation) with facts, with science, and based on your experience.

Q: Do the data presented to the FDA and the CDC about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds seem robust to you?

Dr. Zerr: Yes, and data collection will be ongoing.

Dr. Hotez: I’ve only seen what’s publicly available so far, and it seems to support moving forward with emergency use authorization. The only shortfall is the size, roughly 2,200 children, which would not be of sufficient size to detect a rare safety signal.

Q: Do previous controversies around pediatric vaccines (for example, the MMR vaccine and autism) give pediatricians some background and experience so they can address any pushback on the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: Pediatricians have been dealing with vaccine hesitancy for a while now, ever since the MMR and autism controversy started. Even before then, there were certain groups of people who didn’t want vaccines.

We’ve really worked hard at helping teach pediatricians how to deal with the misinformation, how to counter it, and how to help parents understand the vaccines are safe and effective – and that they save lives.

That (experience) will help us in some ways. Unfortunately, there is more misinformation out there – there is almost a concerted effort on misinformation. It’s big.

Pediatricians will do everything we can, but we need help countering it. We need the misinformation to quit getting spread on social media. We can talk one on one with patients and families, but if all they are hearing on social media is the misinformation, it’s really hard.

Q: Are pediatricians, especially solo practitioners or pediatricians at smaller practices, going to face challenges with multidose vials and not wasting vaccine product?

Dr. Goza: I’m at a small practice. We have 3.5 FTEs (full-time equivalents) of MDs and three FTEs of nurse practitioners. So we’re not that big – about six providers.

You know, it is a challenge. We’re not going to buy the super-duper freezer, and we’re not going to be able to store these vaccines for a long period of time.

So when we order, we need smaller amounts. For the 12- to 18-year-olds, [maximum storage] was 45 days. Now for the 5- to 11-year-olds, we’re going to be able to store the vaccine in the refrigerator for 10 weeks, which gives us more leeway there.

We try to do all of vaccinations on 1 day, so we know how many people are coming in, and we are not going to waste too many doses.

Our Department of Public Health in Georgia has said: “We want these vaccines in the arms of kids, and if you have to waste some doses, don’t worry about it.” But it’s a 10-dose vial. It’s going to be hard for me to open it up for one child. I just don’t like wasting anything like this.

Our main goal is to get this vaccine in to the arms of children whose parents want it.

Q: What are some additional sources of information for pediatricians?

Dr. Zerr: There are a lot of great resources on vaccine hesitancy from reputable sources, including these from the CDC and from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:

- Building Confidence With OVID-19 Vaccines

- How to Talk With Parents About COVID-19 Vaccination

- Strategies for Building Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines

- Communication Strategies for Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines: Addressing Variants and Childhood Vaccinations

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This news organization spoke to several pediatric experts to get answers.

More than 6 million children and adolescents (up to age 18 years) in the United States have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Children represent about 17% of all cases, and an estimated 0.1%-2% of infected children end up hospitalized, according to Oct. 28 data from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Physicians and other health care practitioners are gearing up for what could be an influx of patients. “Pediatricians are standing by to talk with families about the vaccine and to administer the vaccine to children as soon as possible,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, FAAP, president of the AAP, said in a statement.

In this Q&A, this news organization asked for additional advice from Sara “Sally” Goza, MD, a pediatrician in Fayetteville, Georgia, and immediate past president of the AAP; Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and codirector of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, both in Houston; and Danielle M. Zerr, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at the University of Washington, Seattle, and medical director of infection prevention at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Q: How are smaller pediatric practices and solo practitioners going to handle the additional vaccinations?

Dr. Goza: It’s a scheduling challenge with this rollout and all the people who want it and want it right now. They’re going to want it this week.

I’ve actually had some children asking their moms: “When can I get it? When can I get it?” It’s been very interesting – they are chomping at the bit.

If I give the vaccine to a patient this week, in 3 weeks the second dose will be right around Thanksgiving. No one in my office is going to want to be here to give the shot on Thanksgiving, and no patient is going to want to come in on Thanksgiving weekend. So I’m trying to delay those parents – saying, let’s do it next week. That way we’re not messing up a holiday.

Children are going to need two doses, and they won’t be fully protected until 2 weeks after their second dose. So they won’t get full protection for Thanksgiving, but they will have full protection for Christmas.

I know there are a lot of pediatricians who have preordered the vaccine. I know in our office they sent us an email ... to let us know our vaccines are being shipped. So I think a lot of pediatricians are going to have the vaccine.

Q: How should pediatricians counsel parents who are fearful or hesitant?

Dr. Hotez: It’s important to emphasize the severity of the 2021 summer Delta epidemic in children. We need to get beyond this false narrative that COVID only produces a mild disease in children. It’s caused thousands of pediatric hospitalizations, not to mention long COVID.

Dr. Zerr: It is key to find out what concerns parents have and then focus on answering their specific questions. It is helpful to emphasize the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and to explain the rigorous processes that the vaccine went through to receive Food and Drug Administration approval.

Q: How should pediatricians counter any misinformation/disinformation out there about the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: The most important thing is not to discount what they are saying. Don’t say: “That’s crazy” or “That’s not true.” Don’t roll your eyes and say: “Really, you’re going to believe all that?”

Instead, have a conversation with them about why we think that is not true, or why we know that’s not true. We really have to have that relationship and ask: “Well, what are your concerns?” And then really counter (any misinformation) with facts, with science, and based on your experience.

Q: Do the data presented to the FDA and the CDC about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds seem robust to you?

Dr. Zerr: Yes, and data collection will be ongoing.

Dr. Hotez: I’ve only seen what’s publicly available so far, and it seems to support moving forward with emergency use authorization. The only shortfall is the size, roughly 2,200 children, which would not be of sufficient size to detect a rare safety signal.

Q: Do previous controversies around pediatric vaccines (for example, the MMR vaccine and autism) give pediatricians some background and experience so they can address any pushback on the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: Pediatricians have been dealing with vaccine hesitancy for a while now, ever since the MMR and autism controversy started. Even before then, there were certain groups of people who didn’t want vaccines.

We’ve really worked hard at helping teach pediatricians how to deal with the misinformation, how to counter it, and how to help parents understand the vaccines are safe and effective – and that they save lives.

That (experience) will help us in some ways. Unfortunately, there is more misinformation out there – there is almost a concerted effort on misinformation. It’s big.

Pediatricians will do everything we can, but we need help countering it. We need the misinformation to quit getting spread on social media. We can talk one on one with patients and families, but if all they are hearing on social media is the misinformation, it’s really hard.

Q: Are pediatricians, especially solo practitioners or pediatricians at smaller practices, going to face challenges with multidose vials and not wasting vaccine product?

Dr. Goza: I’m at a small practice. We have 3.5 FTEs (full-time equivalents) of MDs and three FTEs of nurse practitioners. So we’re not that big – about six providers.

You know, it is a challenge. We’re not going to buy the super-duper freezer, and we’re not going to be able to store these vaccines for a long period of time.

So when we order, we need smaller amounts. For the 12- to 18-year-olds, [maximum storage] was 45 days. Now for the 5- to 11-year-olds, we’re going to be able to store the vaccine in the refrigerator for 10 weeks, which gives us more leeway there.

We try to do all of vaccinations on 1 day, so we know how many people are coming in, and we are not going to waste too many doses.

Our Department of Public Health in Georgia has said: “We want these vaccines in the arms of kids, and if you have to waste some doses, don’t worry about it.” But it’s a 10-dose vial. It’s going to be hard for me to open it up for one child. I just don’t like wasting anything like this.

Our main goal is to get this vaccine in to the arms of children whose parents want it.

Q: What are some additional sources of information for pediatricians?

Dr. Zerr: There are a lot of great resources on vaccine hesitancy from reputable sources, including these from the CDC and from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:

- Building Confidence With OVID-19 Vaccines

- How to Talk With Parents About COVID-19 Vaccination

- Strategies for Building Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines

- Communication Strategies for Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines: Addressing Variants and Childhood Vaccinations

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This news organization spoke to several pediatric experts to get answers.

More than 6 million children and adolescents (up to age 18 years) in the United States have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Children represent about 17% of all cases, and an estimated 0.1%-2% of infected children end up hospitalized, according to Oct. 28 data from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Physicians and other health care practitioners are gearing up for what could be an influx of patients. “Pediatricians are standing by to talk with families about the vaccine and to administer the vaccine to children as soon as possible,” Lee Savio Beers, MD, FAAP, president of the AAP, said in a statement.

In this Q&A, this news organization asked for additional advice from Sara “Sally” Goza, MD, a pediatrician in Fayetteville, Georgia, and immediate past president of the AAP; Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and codirector of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, both in Houston; and Danielle M. Zerr, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious disease at the University of Washington, Seattle, and medical director of infection prevention at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Q: How are smaller pediatric practices and solo practitioners going to handle the additional vaccinations?

Dr. Goza: It’s a scheduling challenge with this rollout and all the people who want it and want it right now. They’re going to want it this week.

I’ve actually had some children asking their moms: “When can I get it? When can I get it?” It’s been very interesting – they are chomping at the bit.

If I give the vaccine to a patient this week, in 3 weeks the second dose will be right around Thanksgiving. No one in my office is going to want to be here to give the shot on Thanksgiving, and no patient is going to want to come in on Thanksgiving weekend. So I’m trying to delay those parents – saying, let’s do it next week. That way we’re not messing up a holiday.

Children are going to need two doses, and they won’t be fully protected until 2 weeks after their second dose. So they won’t get full protection for Thanksgiving, but they will have full protection for Christmas.

I know there are a lot of pediatricians who have preordered the vaccine. I know in our office they sent us an email ... to let us know our vaccines are being shipped. So I think a lot of pediatricians are going to have the vaccine.

Q: How should pediatricians counsel parents who are fearful or hesitant?

Dr. Hotez: It’s important to emphasize the severity of the 2021 summer Delta epidemic in children. We need to get beyond this false narrative that COVID only produces a mild disease in children. It’s caused thousands of pediatric hospitalizations, not to mention long COVID.

Dr. Zerr: It is key to find out what concerns parents have and then focus on answering their specific questions. It is helpful to emphasize the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and to explain the rigorous processes that the vaccine went through to receive Food and Drug Administration approval.

Q: How should pediatricians counter any misinformation/disinformation out there about the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: The most important thing is not to discount what they are saying. Don’t say: “That’s crazy” or “That’s not true.” Don’t roll your eyes and say: “Really, you’re going to believe all that?”

Instead, have a conversation with them about why we think that is not true, or why we know that’s not true. We really have to have that relationship and ask: “Well, what are your concerns?” And then really counter (any misinformation) with facts, with science, and based on your experience.

Q: Do the data presented to the FDA and the CDC about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds seem robust to you?

Dr. Zerr: Yes, and data collection will be ongoing.

Dr. Hotez: I’ve only seen what’s publicly available so far, and it seems to support moving forward with emergency use authorization. The only shortfall is the size, roughly 2,200 children, which would not be of sufficient size to detect a rare safety signal.

Q: Do previous controversies around pediatric vaccines (for example, the MMR vaccine and autism) give pediatricians some background and experience so they can address any pushback on the COVID-19 vaccines?

Dr. Goza: Pediatricians have been dealing with vaccine hesitancy for a while now, ever since the MMR and autism controversy started. Even before then, there were certain groups of people who didn’t want vaccines.

We’ve really worked hard at helping teach pediatricians how to deal with the misinformation, how to counter it, and how to help parents understand the vaccines are safe and effective – and that they save lives.

That (experience) will help us in some ways. Unfortunately, there is more misinformation out there – there is almost a concerted effort on misinformation. It’s big.

Pediatricians will do everything we can, but we need help countering it. We need the misinformation to quit getting spread on social media. We can talk one on one with patients and families, but if all they are hearing on social media is the misinformation, it’s really hard.

Q: Are pediatricians, especially solo practitioners or pediatricians at smaller practices, going to face challenges with multidose vials and not wasting vaccine product?

Dr. Goza: I’m at a small practice. We have 3.5 FTEs (full-time equivalents) of MDs and three FTEs of nurse practitioners. So we’re not that big – about six providers.

You know, it is a challenge. We’re not going to buy the super-duper freezer, and we’re not going to be able to store these vaccines for a long period of time.

So when we order, we need smaller amounts. For the 12- to 18-year-olds, [maximum storage] was 45 days. Now for the 5- to 11-year-olds, we’re going to be able to store the vaccine in the refrigerator for 10 weeks, which gives us more leeway there.

We try to do all of vaccinations on 1 day, so we know how many people are coming in, and we are not going to waste too many doses.

Our Department of Public Health in Georgia has said: “We want these vaccines in the arms of kids, and if you have to waste some doses, don’t worry about it.” But it’s a 10-dose vial. It’s going to be hard for me to open it up for one child. I just don’t like wasting anything like this.

Our main goal is to get this vaccine in to the arms of children whose parents want it.

Q: What are some additional sources of information for pediatricians?

Dr. Zerr: There are a lot of great resources on vaccine hesitancy from reputable sources, including these from the CDC and from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine:

- Building Confidence With OVID-19 Vaccines

- How to Talk With Parents About COVID-19 Vaccination

- Strategies for Building Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccines

- Communication Strategies for Building Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines: Addressing Variants and Childhood Vaccinations

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can adjunct corticosteroids help in childrens’ eye and throat infections?

Adding anti-inflammatory corticosteroids to antibiotics for certain pediatric throat and ocular infections may have some benefit, according to results from two recent database studies, but their benefit remains unclear.

Using steroids in this setting is a practice many pediatricians consider, although no clear guidance exists.

Drawing on data from a registry of 51 free-standing children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), and published online in Pediatrics, the analyses looked, respectively, at retro- and parapharyngeal abscesses (RPAs/PPAs) and acute orbital cellulitis.

Throat abscesses

In the first study, pediatrician Pratichi K. Goenka, MD, of Cohen Children’s Medical Center–Northwell Health and an assistant professor at Hofstra University, both in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues reported on the effect of systemic corticosteroids on several outcomes in RPAs/PPAs in 2,259 well-matched patients. The patients, aged 2 months to 8 years, were treated at 46 hospitals during the period from January 2016 to December 2019.

The data revealed that the 582 (25.8%) who received steroids had a significantly lower rate of surgical drainage, the study’s primary endpoint (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36). There was no difference, however, in length of hospital stay (rate ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92-1.02).

Those in the steroid group also had lower overall hospital costs and were less likely to be given opioid medications for pain. They were, however, more likely to undergo repeat CT imaging and also had a higher 7-day ED revisit rate but no increase in readmission 30 days after discharge: 4% versus 3% in the nonsteroid group (P = .29).

“As hospitalists, we share the care of young children with RPAs and PPAs with our otolaryngology colleagues. The primary therapy is antibiotics but there was no clear guidance on the next step, and the current literature had no answers as to how systemic corticosteroids might impact the care of these children,” Dr. Goenka said in an interview. “So we wanted to leverage the PHIS data to better understand the association with the need for surgery and length of stay. Surgery is painful and often involves IV administration of opioid painkillers. It’s something we may be able to avoid if we can optimize medical treatment.”

Pending results from randomized trials, what immediate impact could these registry findings have? “We hope that physicians will think about the best initial medical treatment plan for these children,” Dr. Goenka said. ”Given these data, I would be more likely to incorporate steroids early on in medical treatment.”

She emphasized, however, that before routine adoption prospective studies are needed to clearly identify which patients will have a strong benefit and which will not benefit. “That is the nuanced discussion that will happen with more prospective work.”

Dr. Goenka and associates explained that the rising incidence of RPAs and PPAs over the past 20 years has been attributed to more cases of tonsillitis because of a shift away from tonsillectomies, as well as the changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

In an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, and Jens C. Eickhoff, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, stated that the use of corticosteroids in bacterial meningitis is often cited as an example of the benefits of steroids in infection. “The specific rationale for use of corticosteroids is [their] anti-inflammatory effects, which may result in decreases of swelling and/ or edema to facilitate drainage, perfusion, reduction in pain, and healing.”

They cautioned, however, that the pharmacologic effects of steroids are myriad and complicated, and include potential masking of the clinical course of disease, thereby delaying appropriate therapy for unrecognized deterioration, as well potential immunosuppression.

Acute orbital cellulitis

In the second retrospective analysis, a group led by pediatrician Maria Anna Leszczynska, MD, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in Baltimore, analyzed a retrospective PHIS cohort of 5,645 children younger than 18 years with a primary diagnosis of orbital cellulitis treated at 51 hospitals from January 2007 to December 2018.

Of these, 1,347 (24%) received steroids, but, contrary to earlier reports, the data showed no reduction in length of stay associated with these drugs after adjustment for age, meningitis, abscess, or vision issues (ebeta, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06). Corticosteroid exposure was, however, associated with operative episodes after 2 days’ hospitalization (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.29-3.27) and 30-day readmission (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.52-3.78).

“Among children hospitalized for orbital cellulitis, we did not observe the reduction in LOS [length of stay] for patients prescribed systemic corticosteroids as described previously in the literature,” the authors wrote.

In terms of surgical procedures, 52.0% of corticosteroid recipients versus 14.0% of nonrecipients underwent surgery (P < .001), and more were hospitalized in the pediatric ICU (4.4% vs 2.6%; P < .001).

According to the editorialists: “Both observations suggest that children who received steroids may have been a sicker group of patients.”

Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff pointed out that the effect of steroids is ultimately unclear because of the retrospective study’s inherent potential for bias because of unobserved confounders. Were steroids prescribed more often when children were perceived to be sicker with more severe disease, or did these medications cause worse outcomes?

The authors agreed that the study could not determine causality. “Although we used all available markers of disease severity, there does not exist a validated disease severity clinical score for pediatric orbital cellulitis,” they wrote.

According to Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics and division and service chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, “orbital cellulitis is a not very common thing in children so we don’t treat many patients with this. But having said that, there is usually some debate among providers about whether to use steroids.”

Some centers use them routinely for central nervous system and eye infections or extensions of sinusitis, he said, but there is variability in the prescribing of corticosteroids. “There’s ongoing discussion as to whether they‘re as helpful in orbital cellulitis as they are in similar conditions,” Dr. Quinonez said in an interview. “At our institution we don’t typically prescribe them – not never but not routinely. Children who are sicker tend to get steroids, as they do in other conditions.”

In the context of PPA as in the first study, he added, “I think the evidence favoring the use of steroids in infections that affect the airway is stronger, and their use is definitely more prevalent in those instances.”

While both PHIS analyses suggested some benefit from steroids, he continued, some children may not benefit and there may be harms. “The evidence is still mostly retrospective and observational with no multicenter randomized controlled data. Without those data the evidence is difficult to interpret and subject to all the biases that observational and retrospective data is subject to and the current evidence should not lead physicians to change their practice until controlled, randomized evidence is available.”

The editorialists concurred with the study authors and Dr. Quinonez that large, controlled, prospective clinical trials are needed to ascertain the effect of steroids and to standardize the approach to diagnosis and management. “Use of administrative databases are not optimal to answer questions related to outcome,” they wrote.

The study by Dr. Goenka and associates received no external funding; the study by Dr. Leszczynska and associates also received no external funding. None of the authors declared potential competing interests. Dr. Quinonez had no competing interests to declare. Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff disclosed no competing interests with regard to their editorial.

Adding anti-inflammatory corticosteroids to antibiotics for certain pediatric throat and ocular infections may have some benefit, according to results from two recent database studies, but their benefit remains unclear.

Using steroids in this setting is a practice many pediatricians consider, although no clear guidance exists.

Drawing on data from a registry of 51 free-standing children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), and published online in Pediatrics, the analyses looked, respectively, at retro- and parapharyngeal abscesses (RPAs/PPAs) and acute orbital cellulitis.

Throat abscesses

In the first study, pediatrician Pratichi K. Goenka, MD, of Cohen Children’s Medical Center–Northwell Health and an assistant professor at Hofstra University, both in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues reported on the effect of systemic corticosteroids on several outcomes in RPAs/PPAs in 2,259 well-matched patients. The patients, aged 2 months to 8 years, were treated at 46 hospitals during the period from January 2016 to December 2019.

The data revealed that the 582 (25.8%) who received steroids had a significantly lower rate of surgical drainage, the study’s primary endpoint (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36). There was no difference, however, in length of hospital stay (rate ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92-1.02).

Those in the steroid group also had lower overall hospital costs and were less likely to be given opioid medications for pain. They were, however, more likely to undergo repeat CT imaging and also had a higher 7-day ED revisit rate but no increase in readmission 30 days after discharge: 4% versus 3% in the nonsteroid group (P = .29).

“As hospitalists, we share the care of young children with RPAs and PPAs with our otolaryngology colleagues. The primary therapy is antibiotics but there was no clear guidance on the next step, and the current literature had no answers as to how systemic corticosteroids might impact the care of these children,” Dr. Goenka said in an interview. “So we wanted to leverage the PHIS data to better understand the association with the need for surgery and length of stay. Surgery is painful and often involves IV administration of opioid painkillers. It’s something we may be able to avoid if we can optimize medical treatment.”

Pending results from randomized trials, what immediate impact could these registry findings have? “We hope that physicians will think about the best initial medical treatment plan for these children,” Dr. Goenka said. ”Given these data, I would be more likely to incorporate steroids early on in medical treatment.”

She emphasized, however, that before routine adoption prospective studies are needed to clearly identify which patients will have a strong benefit and which will not benefit. “That is the nuanced discussion that will happen with more prospective work.”

Dr. Goenka and associates explained that the rising incidence of RPAs and PPAs over the past 20 years has been attributed to more cases of tonsillitis because of a shift away from tonsillectomies, as well as the changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

In an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, and Jens C. Eickhoff, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, stated that the use of corticosteroids in bacterial meningitis is often cited as an example of the benefits of steroids in infection. “The specific rationale for use of corticosteroids is [their] anti-inflammatory effects, which may result in decreases of swelling and/ or edema to facilitate drainage, perfusion, reduction in pain, and healing.”

They cautioned, however, that the pharmacologic effects of steroids are myriad and complicated, and include potential masking of the clinical course of disease, thereby delaying appropriate therapy for unrecognized deterioration, as well potential immunosuppression.

Acute orbital cellulitis

In the second retrospective analysis, a group led by pediatrician Maria Anna Leszczynska, MD, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in Baltimore, analyzed a retrospective PHIS cohort of 5,645 children younger than 18 years with a primary diagnosis of orbital cellulitis treated at 51 hospitals from January 2007 to December 2018.

Of these, 1,347 (24%) received steroids, but, contrary to earlier reports, the data showed no reduction in length of stay associated with these drugs after adjustment for age, meningitis, abscess, or vision issues (ebeta, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06). Corticosteroid exposure was, however, associated with operative episodes after 2 days’ hospitalization (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.29-3.27) and 30-day readmission (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.52-3.78).

“Among children hospitalized for orbital cellulitis, we did not observe the reduction in LOS [length of stay] for patients prescribed systemic corticosteroids as described previously in the literature,” the authors wrote.

In terms of surgical procedures, 52.0% of corticosteroid recipients versus 14.0% of nonrecipients underwent surgery (P < .001), and more were hospitalized in the pediatric ICU (4.4% vs 2.6%; P < .001).

According to the editorialists: “Both observations suggest that children who received steroids may have been a sicker group of patients.”

Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff pointed out that the effect of steroids is ultimately unclear because of the retrospective study’s inherent potential for bias because of unobserved confounders. Were steroids prescribed more often when children were perceived to be sicker with more severe disease, or did these medications cause worse outcomes?

The authors agreed that the study could not determine causality. “Although we used all available markers of disease severity, there does not exist a validated disease severity clinical score for pediatric orbital cellulitis,” they wrote.

According to Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics and division and service chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, “orbital cellulitis is a not very common thing in children so we don’t treat many patients with this. But having said that, there is usually some debate among providers about whether to use steroids.”

Some centers use them routinely for central nervous system and eye infections or extensions of sinusitis, he said, but there is variability in the prescribing of corticosteroids. “There’s ongoing discussion as to whether they‘re as helpful in orbital cellulitis as they are in similar conditions,” Dr. Quinonez said in an interview. “At our institution we don’t typically prescribe them – not never but not routinely. Children who are sicker tend to get steroids, as they do in other conditions.”

In the context of PPA as in the first study, he added, “I think the evidence favoring the use of steroids in infections that affect the airway is stronger, and their use is definitely more prevalent in those instances.”

While both PHIS analyses suggested some benefit from steroids, he continued, some children may not benefit and there may be harms. “The evidence is still mostly retrospective and observational with no multicenter randomized controlled data. Without those data the evidence is difficult to interpret and subject to all the biases that observational and retrospective data is subject to and the current evidence should not lead physicians to change their practice until controlled, randomized evidence is available.”

The editorialists concurred with the study authors and Dr. Quinonez that large, controlled, prospective clinical trials are needed to ascertain the effect of steroids and to standardize the approach to diagnosis and management. “Use of administrative databases are not optimal to answer questions related to outcome,” they wrote.

The study by Dr. Goenka and associates received no external funding; the study by Dr. Leszczynska and associates also received no external funding. None of the authors declared potential competing interests. Dr. Quinonez had no competing interests to declare. Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff disclosed no competing interests with regard to their editorial.

Adding anti-inflammatory corticosteroids to antibiotics for certain pediatric throat and ocular infections may have some benefit, according to results from two recent database studies, but their benefit remains unclear.

Using steroids in this setting is a practice many pediatricians consider, although no clear guidance exists.

Drawing on data from a registry of 51 free-standing children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), and published online in Pediatrics, the analyses looked, respectively, at retro- and parapharyngeal abscesses (RPAs/PPAs) and acute orbital cellulitis.

Throat abscesses

In the first study, pediatrician Pratichi K. Goenka, MD, of Cohen Children’s Medical Center–Northwell Health and an assistant professor at Hofstra University, both in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues reported on the effect of systemic corticosteroids on several outcomes in RPAs/PPAs in 2,259 well-matched patients. The patients, aged 2 months to 8 years, were treated at 46 hospitals during the period from January 2016 to December 2019.

The data revealed that the 582 (25.8%) who received steroids had a significantly lower rate of surgical drainage, the study’s primary endpoint (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.36). There was no difference, however, in length of hospital stay (rate ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92-1.02).

Those in the steroid group also had lower overall hospital costs and were less likely to be given opioid medications for pain. They were, however, more likely to undergo repeat CT imaging and also had a higher 7-day ED revisit rate but no increase in readmission 30 days after discharge: 4% versus 3% in the nonsteroid group (P = .29).

“As hospitalists, we share the care of young children with RPAs and PPAs with our otolaryngology colleagues. The primary therapy is antibiotics but there was no clear guidance on the next step, and the current literature had no answers as to how systemic corticosteroids might impact the care of these children,” Dr. Goenka said in an interview. “So we wanted to leverage the PHIS data to better understand the association with the need for surgery and length of stay. Surgery is painful and often involves IV administration of opioid painkillers. It’s something we may be able to avoid if we can optimize medical treatment.”

Pending results from randomized trials, what immediate impact could these registry findings have? “We hope that physicians will think about the best initial medical treatment plan for these children,” Dr. Goenka said. ”Given these data, I would be more likely to incorporate steroids early on in medical treatment.”

She emphasized, however, that before routine adoption prospective studies are needed to clearly identify which patients will have a strong benefit and which will not benefit. “That is the nuanced discussion that will happen with more prospective work.”

Dr. Goenka and associates explained that the rising incidence of RPAs and PPAs over the past 20 years has been attributed to more cases of tonsillitis because of a shift away from tonsillectomies, as well as the changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

In an accompanying editorial, Ellen R. Wald, MD, and Jens C. Eickhoff, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, stated that the use of corticosteroids in bacterial meningitis is often cited as an example of the benefits of steroids in infection. “The specific rationale for use of corticosteroids is [their] anti-inflammatory effects, which may result in decreases of swelling and/ or edema to facilitate drainage, perfusion, reduction in pain, and healing.”

They cautioned, however, that the pharmacologic effects of steroids are myriad and complicated, and include potential masking of the clinical course of disease, thereby delaying appropriate therapy for unrecognized deterioration, as well potential immunosuppression.

Acute orbital cellulitis

In the second retrospective analysis, a group led by pediatrician Maria Anna Leszczynska, MD, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in Baltimore, analyzed a retrospective PHIS cohort of 5,645 children younger than 18 years with a primary diagnosis of orbital cellulitis treated at 51 hospitals from January 2007 to December 2018.

Of these, 1,347 (24%) received steroids, but, contrary to earlier reports, the data showed no reduction in length of stay associated with these drugs after adjustment for age, meningitis, abscess, or vision issues (ebeta, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06). Corticosteroid exposure was, however, associated with operative episodes after 2 days’ hospitalization (OR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.29-3.27) and 30-day readmission (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.52-3.78).

“Among children hospitalized for orbital cellulitis, we did not observe the reduction in LOS [length of stay] for patients prescribed systemic corticosteroids as described previously in the literature,” the authors wrote.

In terms of surgical procedures, 52.0% of corticosteroid recipients versus 14.0% of nonrecipients underwent surgery (P < .001), and more were hospitalized in the pediatric ICU (4.4% vs 2.6%; P < .001).

According to the editorialists: “Both observations suggest that children who received steroids may have been a sicker group of patients.”

Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff pointed out that the effect of steroids is ultimately unclear because of the retrospective study’s inherent potential for bias because of unobserved confounders. Were steroids prescribed more often when children were perceived to be sicker with more severe disease, or did these medications cause worse outcomes?

The authors agreed that the study could not determine causality. “Although we used all available markers of disease severity, there does not exist a validated disease severity clinical score for pediatric orbital cellulitis,” they wrote.

According to Ricardo A. Quinonez, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics and division and service chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, “orbital cellulitis is a not very common thing in children so we don’t treat many patients with this. But having said that, there is usually some debate among providers about whether to use steroids.”

Some centers use them routinely for central nervous system and eye infections or extensions of sinusitis, he said, but there is variability in the prescribing of corticosteroids. “There’s ongoing discussion as to whether they‘re as helpful in orbital cellulitis as they are in similar conditions,” Dr. Quinonez said in an interview. “At our institution we don’t typically prescribe them – not never but not routinely. Children who are sicker tend to get steroids, as they do in other conditions.”

In the context of PPA as in the first study, he added, “I think the evidence favoring the use of steroids in infections that affect the airway is stronger, and their use is definitely more prevalent in those instances.”

While both PHIS analyses suggested some benefit from steroids, he continued, some children may not benefit and there may be harms. “The evidence is still mostly retrospective and observational with no multicenter randomized controlled data. Without those data the evidence is difficult to interpret and subject to all the biases that observational and retrospective data is subject to and the current evidence should not lead physicians to change their practice until controlled, randomized evidence is available.”

The editorialists concurred with the study authors and Dr. Quinonez that large, controlled, prospective clinical trials are needed to ascertain the effect of steroids and to standardize the approach to diagnosis and management. “Use of administrative databases are not optimal to answer questions related to outcome,” they wrote.

The study by Dr. Goenka and associates received no external funding; the study by Dr. Leszczynska and associates also received no external funding. None of the authors declared potential competing interests. Dr. Quinonez had no competing interests to declare. Dr. Wald and Dr. Eickhoff disclosed no competing interests with regard to their editorial.

FROM PEDIATRICS

HCV in pregnancy: One piece of a bigger problem

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

Mirroring the opioid crisis, maternal and newborn hepatitis C infections (HCV) more than doubled in the United States between 2009 and 2019, with disproportionate increases in people of White, American Indian, and Alaska Native race, especially those with less education, according to a cross-sectional study published in JAMA Health Forum. However, the level of risk within these populations was mitigated in counties with higher employment, reported Stephen W. Patrick, MD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., and coauthors.

“As we develop public health approaches to prevent HCV infections, connect to treatment, and monitor exposed infants, understanding these factors can be of critical importance to tailoring interventions,” Dr. Patrick said in an interview. “HCV is one more complication of the opioid crisis,” he added. “These data also enable us to step back a bit from HCV and look at the landscape of how the opioid crisis continues to grow in complexity and scope. Throughout the opioid crisis we have often failed to recognize and address the unique needs of pregnant people and infants.”

The study authors used data from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and from the Area Health Resource File to examine maternal-infant HCV infection among all U.S. births between 2009 and 2019. The researchers also examined community-level risk factors including rurality, employment, and access to medical care.

In counties reporting HCV, there were 39,380,122 people who had live births, of whom 138,343 (0.4%) were diagnosed with HCV. The overall rate of maternal HCV infection increased from 1.8 to 5.1 per 1,000 live births between 2009 and 2019.

Infection rates were highest in American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) and White people (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 7.94 and 7.37, respectively) compared with Black people. They were higher among individuals without a 4-year degree compared to those with higher education (aOR, 3.19).

Among these groups considered to be at higher risk for HCV infection, high employment rates somewhat mitigated the risk. Specifically, in counties in the 10th percentile of employment, the predicted probability of HCV increased from 0.16% to 1.37%, between 2009 and 2019, whereas in counties at the 90th percentile of employment, the predicted probability remained similar, at 0.36% in 2009 and 0.48% in 2019.

“With constrained national resources, understanding both individual and community-level factors associated with HCV infections in pregnant people could inform strategies to mitigate its spread, such as harm reduction efforts (e.g., syringe service programs), improving access to treatment for [opioid use disorder] or increasing the obstetrical workforce in high-risk communities, HCV testing strategies in pregnant people and people of childbearing age, and treatment with novel antiviral therapies,” wrote the authors.

In the time since the authors began the study, universal HCV screening for every pregnancy has been recommended by a number of groups, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). However, Dr. Patrick says even though such recommendations are now adopted, it will be some time before they are fully operational, making knowledge of HCV risk factors important for obstetricians as well as pediatricians and family physicians. “We don’t know how if hospitals and clinicians have started universal screening for HCV and even when it is completely adopted, understanding individual and community-level factors associated with HCV in pregnant people is still of critical importance,” he explained. “In some of our previous work we have found that non-White HCV-exposed infants are less likely to be tested for HCV than are White infants, even after accounting for multiple individual and hospital-level factors. The pattern we are seeing in our research and in research in other groups is one of unequal treatment of pregnant people with substance use disorder in terms of being given evidence-based treatments, being tested for HCV, and even in child welfare outcomes like foster placement. It is important to know these issues are occurring, but we need specific equitable approaches to ensuring optimal outcomes for all families.

Jeffrey A. Kuller, MD, one of the authors of the SMFM’s new recommendations for universal HCV screening in pregnancy, agreed that until universal screening is widely adopted, awareness of maternal HCV risk factors is important, “to better determine who is at highest risk for hep C, barriers to care, and patients to better target.” This information also affects procedure at the time of delivery, added Dr. Kuller, professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. “We do not perform C-sections for the presence of hep C,” he told this publication. However, in labor, “we try to avoid internal fetal monitoring when possible, and early artificial rupture of membranes when possible, and avoid the use of routine episiotomy,” he said. “Hep C–positive patients should also be assessed for other sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hep B. “Although we do not typically treat hep C pharmacologically during pregnancy, we try to get the patient placed with a hepatologist for long-term management.”

The study has important implications for pediatric patients, added Audrey R. Lloyd, MD, a med-peds infectious disease fellow who is studying HCV in pregnancy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “In the setting of maternal HCV viremia, maternal-fetal transmission occurs in around 6% of exposed infants and around 10% if there is maternal HIV-HCV coinfection,” she said in an interview. “With the increasing rates of HCV in pregnant women described by Dr. Patrick et al., HCV infections among infants will also rise. Even when maternal HCV infection is documented, we often do not do a good job screening the infants for infection and linking them to treatment. This new data makes me worried we may see more complications of pediatric HCV infection in the future,” she added. She explained that safe and effective treatments for HCV infection are approved down to 3 years of age, but patients must first be diagnosed to receive treatment.

From whichever angle you approach it, tackling both the opioid epidemic and HCV infection in pregnancy will inevitably end up helping both parts of the mother-infant dyad, said Dr. Patrick. “Not too long ago I was caring for an opioid-exposed infant at the hospital where I practice who had transferred in from another center hours away. The mother had not been tested for HCV, so I tested the infant for HCV antibodies which were positive. Imagine that, determining a mother is HCV positive by testing the infant. There are so many layers of systems that should be fixed to make this not happen. And what are the chances the mother, after she found out, was able to access treatment for HCV? What about the infant being tested? The systems are just fragmented and we need to do better.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health. Neither Dr. Patrick, Dr. Kuller, nor Dr. Lloyd reported any conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

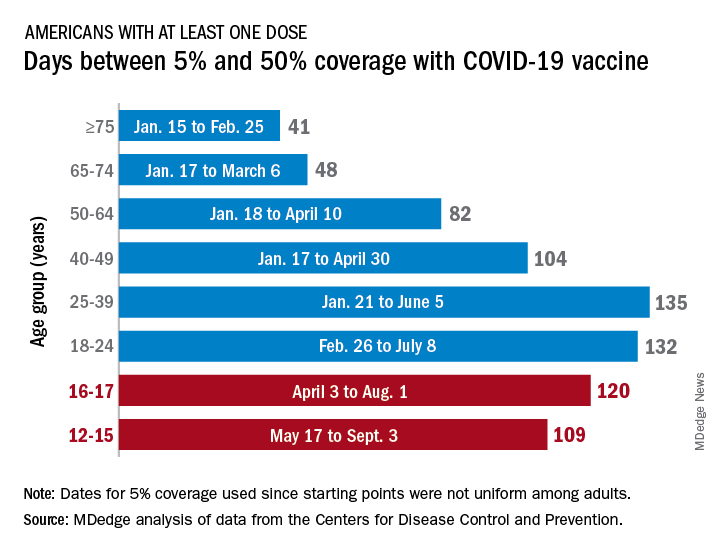

Children and COVID: A look at the pace of vaccination

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

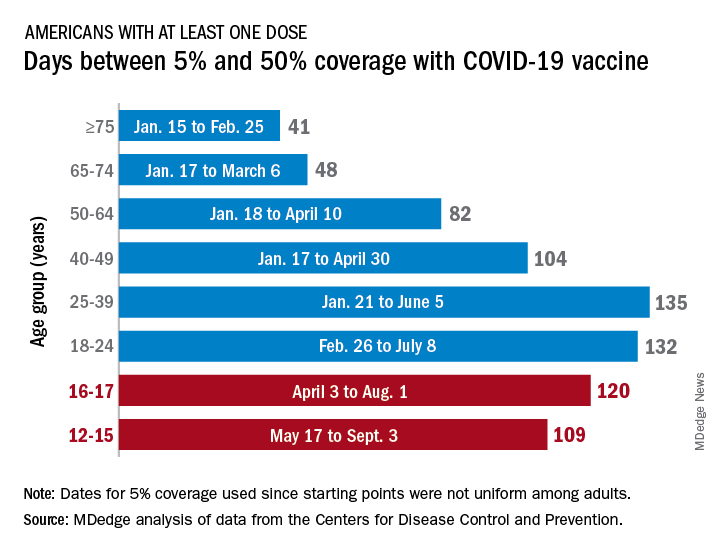

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

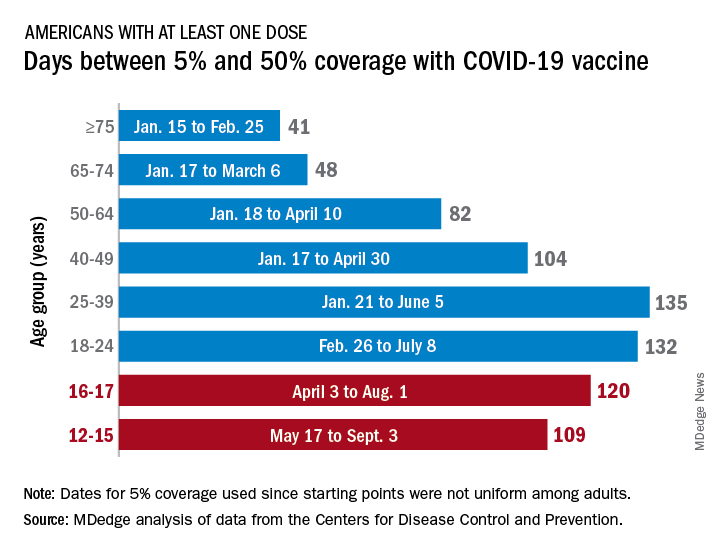

With children aged 5-11 years about to enter the battle-of-the-COVID-vaccine phase of the war on COVID, there are many questions. MDedge takes a look at one: How long will it take to get 5- to 11-year-olds vaccinated?

Previous experience may provide some guidance. The vaccine was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for the closest group in age, 12- to 15-year-olds, on May 12, 2021, and according to data from the CDC.

(Use of the 5% figure acknowledges the uneven start after approval – the vaccine became available to different age groups at different times, even though it had been approved for all adults aged 18 years and older.)

The 16- to 17-year-olds, despite being a smaller group of less than 7.6 million individuals, took 120 days to go from 5% to 50% coverage. For those aged 18-24 years, the corresponding time was 132 days, while the 24- to 36-year-olds took longer than any other age group, 135 days, to reach the 50%-with-at-least-one-dose milestone. The time, in turn, decreased for each group as age increased, with those aged 75 and older taking just 41 days to get at least one dose in 50% of individuals, the CDC data show.

That trend also applies to full vaccination, for the most part. The oldest group, 75 and older, had the shortest time to 50% being fully vaccinated at 69 days, and the 25- to 39-year-olds had the longest time at 206 days, with the length rising as age decreased and dropping for groups younger than 25-39. Except for the 12- to 15-year-olds. It has been 160 days (as of Nov. 2) since the 5% mark was reached on May 17, but only 47.4% of the group is fully vaccinated, making it unlikely that the 50% mark will be reached earlier than the 169 days it took the 16- to 17-year-olds.

So where does that put the 5- to 11-year-olds?

The White House said on Nov. 1 that vaccinations could start the first week of November, pending approval from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which meets on Nov. 2. “This is an important step forward in our nation’s fight against the virus,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a briefing. “As we await the CDC decision, we are not waiting on the operations and logistics. In fact, we’ve been preparing for weeks.”

Availability, of course, is not the only factor involved. In a survey conducted Oct. 14-24, the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 27% of parents of children aged 5-11 years are planning to have them vaccinated against COVID-19 “right away” once the vaccine is available, and that 33% would “wait and see” how the vaccine works.

“Parents of 5-11 year-olds cite a range of concerns when it comes to vaccinating their children for COVID-19, with safety issues topping off the list,” and “two-thirds say they are concerned the vaccine may negatively impact their child’s fertility in the future,” Kaiser said.

Influenza tied to long-term increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.