User login

Purpura Fulminans in an Asplenic Intravenous Drug User

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man with a history of opioid abuse and splenectomy decades prior due to a motor vehicle accident was brought to an outside emergency department with confusion, slurred speech, and difficulty breathing. Over the next few days, he became febrile and hypotensive, requiring vasopressors. Clinical laboratory testing revealed a urine drug screen positive for opioids and a low platelet count in the setting of a rapidly evolving retiform purpuric rash.

The patient was transferred to our institution 6 days after initial presentation with primary diagnoses of septic shock with multiorgan failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods. After several days of broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care, cultures were reported as positive for Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Upon further questioning, the patient’s wife reported that the couple had a new puppy and that the patient often allowed the dog to bite him playfully and lick abrasions on his hands and legs. He had not received medical treatment for any of the dog’s bites.

On initial examination at the time of transfer, the patient’s skin was remarkable for diffuse areas of stellate and retiform purpura with dusky centers and necrosis of the nasal tip and earlobes. Both hands were purpuric, with necrosis of the fingertips (Figure 1A). The flank was marked by large areas of full-thickness sloughing of the skin (Figure 1B). The lower extremities were edematous, with some areas of stellate purpura and numerous large bullae that drained straw-colored fluid (Figure 1C). Lower extremity pulses were found with Doppler ultrasonography.

Given the presence of rapidly developing retiform purpura in the clinical context of severe sepsis, purpura fulminans (PF) was the primary consideration in the differential diagnosis. Levamisole-induced necrosis syndrome also was considered because of necrosis of the ears and nose as well as the history of substance use; however, the patient was not known to have a history of cocaine abuse, and a test of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative.

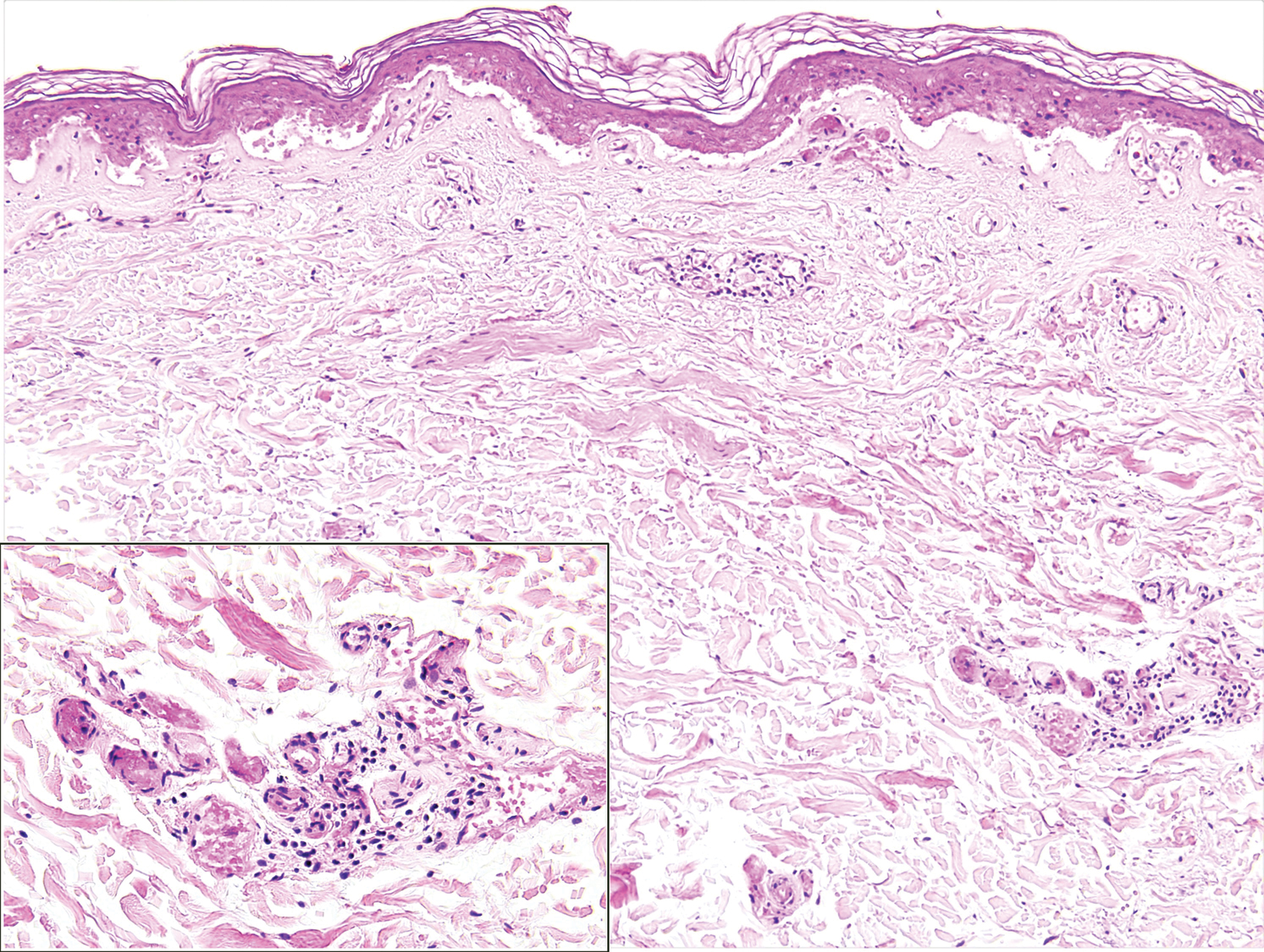

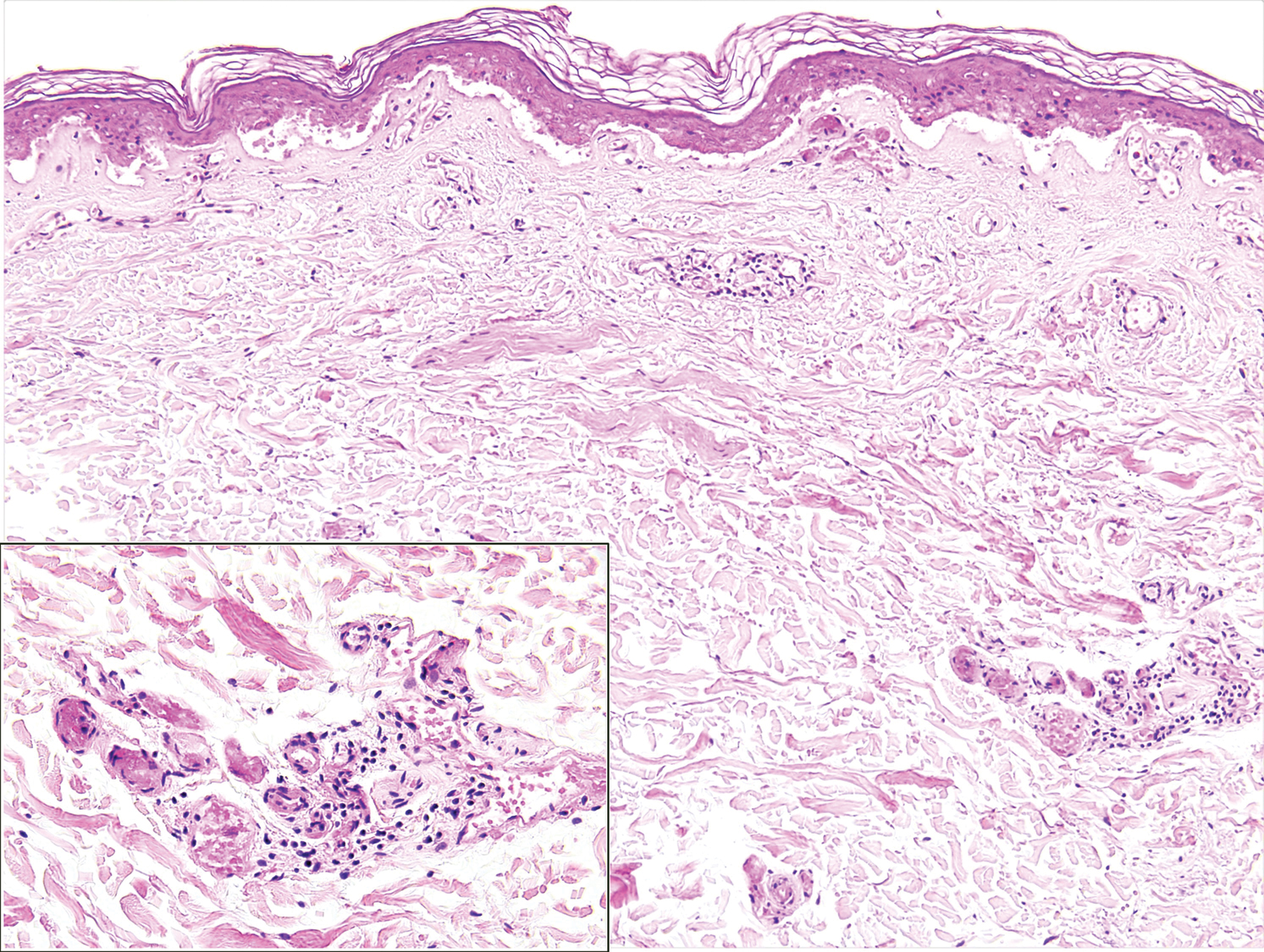

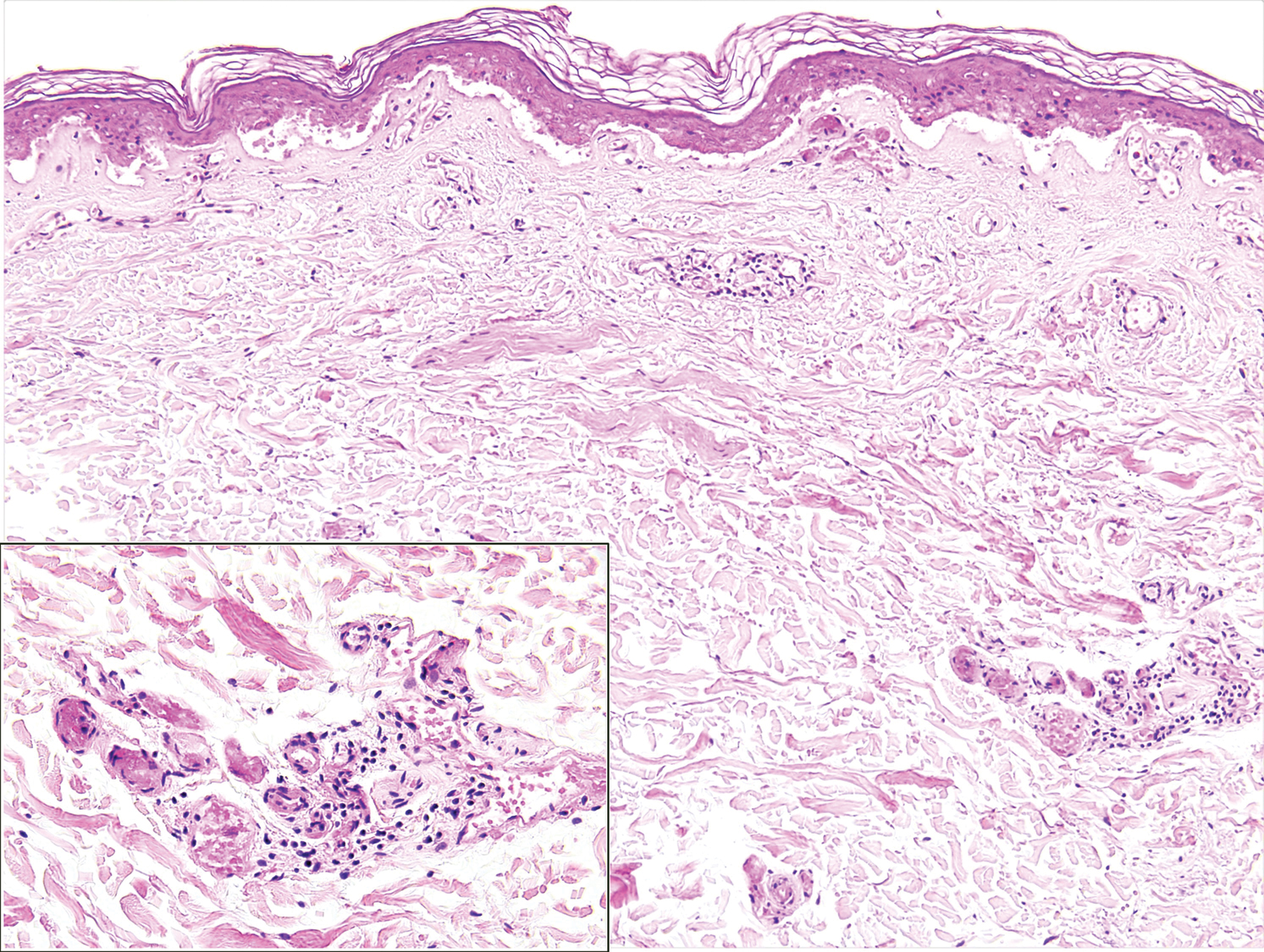

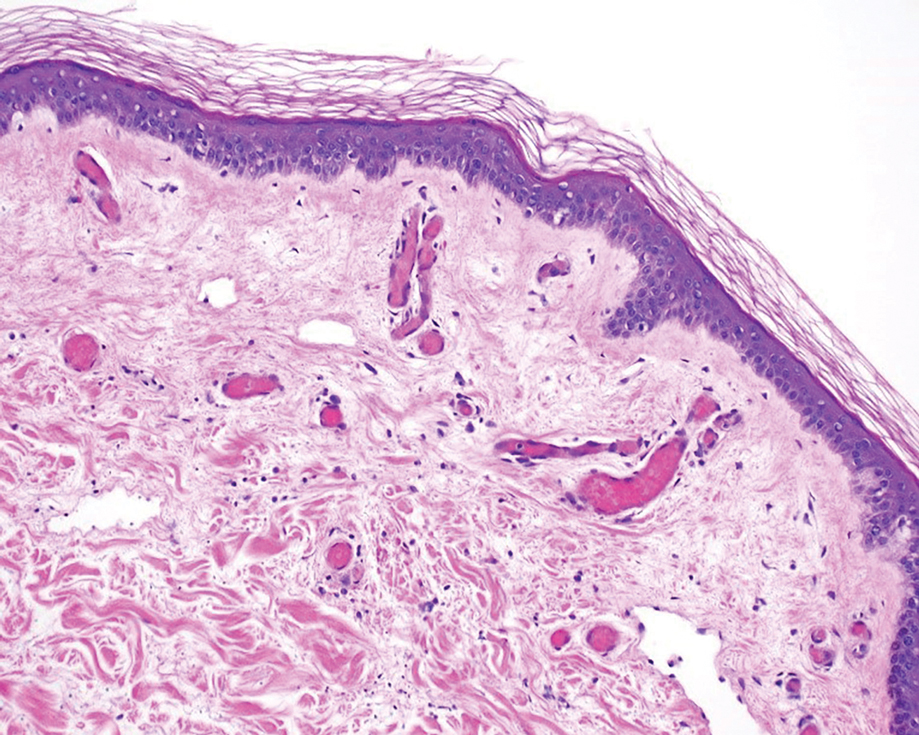

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed intravascular thrombi with epidermal and sweat gland necrosis, consistent with PF (Figure 2). Gram, Giemsa, and Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for organisms. Tissue culture remained negative. Repeat blood cultures demonstrated Candida parapsilosis fungemia. Respiratory culture was positive for budding yeast.

The patient was treated with antimicrobials, intravenous argatroban, and subcutaneous heparin. Purpura and bullae on the trunk slowly resolved with systemic therapy and wound care with petrolatum and nonadherent dressings. However, lesions on the nasal tip, all fingers of both hands, and several toes evolved into dry gangrene. The hospital course was complicated by renal failure requiring continuous renal replacement therapy; respiratory failure requiring ventilator support; and elevated levels of liver enzymes, consistent with involvement of the hepatic microvasculature.

The patient was in the medical intensive care unit at our institution for 2 weeks and was transferred to a burn center for specialized wound care. At transfer, he was still on a ventilator and receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Subsequently, the patient required a left above-the-knee amputation, right below-the-knee amputation, and amputation of several digits of the upper extremities. In the months after the amputations, he required multiple stump revisions and experienced surgical site infections that complicated healing.

Purpura fulminans is an uncommon syndrome characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarction of the skin. The condition commonly is associated with septic shock, causing vascular collapse and DIC. It often develops rapidly.

Because of associated high mortality, it is important to differentiate PF from other causes of cutaneous retiform purpura, including other causes of thrombosis and large vessel vasculitis. Leading causes of PF include infection and hereditary or acquired deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III. Regardless of cause, biopsy results demonstrate vascular thrombosis out of proportion to vasculitis. The mortality rate is 42% to 50%. The incidence of postinfectious sepsis sequelae in PF is higher than in survivors of sepsis only, especially amputation.1-3 Most patients do not die from complications of sepsis but from sequelae of the hypercoagulable and prothrombotic state associated with PF.4 Hemorrhagic infarction can affect the kidneys, brain, lungs, heart, eyes, and adrenal glands (ie, necrosis, namely Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome).5

The most common infectious cause of PF is sepsis secondary to Neisseria meningitidis, with as many as 25% of infected patients developing PF.6Streptococcus pneumoniae is another common cause. Other important causative organisms include Streptococcus pyogenes; Staphylococcus aureus (in the setting of intravenous substance use); Klebsiella oxytoca; Klebsiella aerogenes; rickettsial organisms; and viruses, including cytomegalovirus and varicella-zoster virus.2,7-13 Two earlier cases associated with Capnocytophaga were characterized by concomitant renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hemolytic anemia, and DIC.14

It is estimated that Capnocytophaga causes 11% to 46% of all cases of sepsis15; sepsis resulting from Capnocytophaga has extremely poor outcomes, with mortality reaching as high as 60%. The organism is part of the normal oral flora of cats and dogs, and a bite (less often, a scratch) is the cause of most Capnocytophaga infections. The clinical spectrum of C canimorsus infection associated with dog saliva exposure more commonly includes cellulitis at or around the site of inoculation, meningitis, and endocarditis.16

Although patients affected by PF can be young and healthy, several risk factors for PF have been identified2,6,16: asplenia, an immunocompromised state, systemic corticosteroid use, cirrhosis, and alcoholism. Asplenic patients have been shown to be particularly susceptible to systemic Capnocytophaga infection; when bitten by a dog, they should be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to cover Capnocytophaga.17 Immunocompetent patients rarely develop severe infection with Capnocytophaga.16,18,19 The complement system in particular is critically important in defending against C canimorsus.20

The underlying pathophysiology of acute infectious PF is multifactorial, encompassing increased expression of procoagulant tissue factor by monocytes and endothelial cells in the presence of bacterial pathogens. Dysfunction of protein C, an anticoagulant component of the coagulation cascade, often is cited as a crucial derangement leading to the development of a prothrombotic state in acute infectious PF.21 Serum protein S and antithrombin deficiency also can play a role.22 Specific in vitro examination of C canimorsus has revealed a protease that catalyzes N-terminal cleavage of procoagulant factor X, resulting in loss of function.15

Retiform purpura is a hallmark feature of PF, often beginning as nonblanching erythema with localized edema and petechiae before evolving into the characteristic stellate lesions with hemorrhagic bullae and subsequent necrosis.23 Pathologic examination reveals microthrombi involving arterioles and smaller vessels.24 There typically is laboratory evidence of DIC in PF, including elevated prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer, and a decreased fibrinogen level.6,23

Capnocytophaga bacteria are challenging to grow on standard culture media. Optimal media for growth include 5% sheep’s blood and chocolate agar.16 Polymerase chain reaction can identify Capnocytophaga; in cases in which blood culture does not produce growth, 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of tissue from skin biopsy has identified the pathogen.25

Some Capnocytophaga isolates have been shown to produce beta-lactamase; individual strains can be resistant to penicillins, cephalosporins, and imipenem.26 Factors associated with an increased risk for death include decreased leukocyte and platelet counts and an increased level of arterial lactate.27

Empiric antibiotic therapy for Capnocytophaga sepsis should include a beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitor, such as piperacillin-tazobactam. Management of DIC can include therapeutic heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin and prophylactic platelet transfusion to maintain a pre-established value.28-30 Debridement should be conservative; it is important to wait for definite delineation between viable and necrotic tissue,31 which might take several months.32 Human skin allografts, in addition to artificial skin, are utilized as supplemental therapy for more rapid wound closure after removal of necrotic tissue.33,34 Hyperoxygenated fatty acids have been noted to aid in more rapid wound healing in infants with PF.35

Fresh frozen plasma is one method to replace missing factors, but it contains little protein C.36 Outcomes with recombinant human activated protein C (drotrecogin alfa) are mixed, and studies have shown no benefit in reducing the risk for death.37,38 Protein C concentrate has shown therapeutic benefit in some case reports and small retrospective studies.4 In one case report, protein C concentrate and heparin were utilized in combination with antithrombin III.21

Hyperbaric O2 might be of benefit when initiated within 5 days after onset of PF. However, hyperbaric O2 does carry risk; O2 toxicity, barotrauma, and barriers to timely resuscitation when the patient is inside the pressurized chamber can occur.2

There is a single report of successful use of the vasodilator iloprost for meningococcal PF without need for surgical intervention; the team also utilized topical nitroglycerin patches on the fingers to avoid digital amputation.39 Epoprostenol, tissue plasminogen activator, and antithrombin have been utilized in cases of extensive PF. Fibrinolytic therapy might have some utility, but only in a setting of malignancy-associated DIC.40

Treatment of acute infectious PF lacks a high level of evidence. Options include replacement of anticoagulant factors, anticoagulant therapy, hyperbaric O2, topical and systemic vasodilators, and, in the setting of underlying cancer, fibrinolytics. Even with therapy, prognosis is guarded.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Dutta A. Purpura fulminans: a cutaneous marker of disseminated intravascular coagulation. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:41.

- Ursin Rein P, Jacobsen D, Ormaasen V, et al. Pneumococcal sepsis requiring mechanical ventilation: cohort study in 38 patients with rapid progression to septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:1428-1435. doi:10.1111/aas

- Contou D, Canoui-Poitrine F, Coudroy R, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Long-term quality of life in adult patients surviving purpura fulminans: an exposed-unexposed multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:332-340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy901

- Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.199919

- Karimi K, Odhav A, Kollipara R, et al. Acute cutaneous necrosis: a guide to early diagnosis and treatment. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:425-437. doi:10.1177/1203475417708164

- Colling ME, Bendapudi PK. Purpura fulminans: mechanism and management of dysregulated hemostasis. Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:69-76. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2017.10.001

- Kankeu Fonkoua L, Zhang S, Canty E, et al. Purpura fulminans from reduced protein S following cytomegalovirus and varicella infection. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:491-495. doi:10.1002/ajh.25386

- Okuzono S, Ishimura M, Kanno S, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-purpura fulminans as an invasive form of group A streptococcal infection. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12941-018-0282-9

- Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, Srinivas BH, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus: an uncommon organism. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:132-133. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178093

- Saini S, Duncan RA. Sloughing skin in intravenous drug user. IDCases. 2018;12:74-75. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.03.007

- Tsubouchi N, Tsurukiri J, Numata J, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by Klebsiella oxytoca. Intern Med. 2019;58:1801-1802. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.2350-18

- Yamamoto S, Ito R. Acute infectious purpura fulminans with Enterobacter aerogenes post-neurosurgery. IDCases. 2019;15:e00514. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00514

- Dalugama C, Gawarammana IB. Rare presentation of rickettsial infection as purpura fulminans: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:145. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1672-5

- Kazandjieva J, Antonov D, Kamarashev J, et al. Acrally distributed dermatoses: vascular dermatoses (purpura and vasculitis). Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:68-80. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.013

- Hack K, Renzi F, Hess E, et al. Inactivation of human coagulation factor X by a protease of the pathogen Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:487-499. doi:10.1111/jth.13605

- Zajkowska J, M, Falkowski D, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus—an underestimated danger after dog or cat bite - review of literature. Przegl Epidemiol. 2016;70:289-295.

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet. 2011;378:86-97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6

- Behrend Christiansen C, Berg RMG, Plovsing RR, et al. Two cases of infectious purpura fulminans and septic shock caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus transmitted from dogs. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:635-639. doi:10.3109/00365548.2012.672765

- Ruddock TL, Rindler JM, Bergfeld WF. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia in an asplenic patient. Cutis. 1997;60:95-97.

- Mantovani E, Busani S, Biagioni E, et al. Purpura fulminans and septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus after dog bite: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Crit Care. 2018;2018:7090268. doi:10.1155/2018/7090268

- Bendapudi PK, Robbins A, LeBoeuf N, et al. Persistence of endothelial thrombomodulin in a patient with infectious purpura fulminans treated with protein C concentrate. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2917-2921. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024430

- Lerolle N, Carlotti A, Melican K, et al. Assessment of the interplay between blood and skin vascular abnormalities in adult purpura fulminans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:684-692. doi:10.1164/rccm.201302-0228OC.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC III. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.043

- Adcock DM, Hicks MJ. Dermatopathology of skin necrosis associated with purpura fulminans. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1990;16:283-292. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1002681

- Dautzenberg KHW, Polderman FN, van Suylen RJ, et al. Purpura fulminans mimicking toxic epidermal necrolysis—additional value of 16S rRNA sequencing and skin biopsy. Neth J Med. 2017;75:165-168.

- Zangenah S, Andersson AF, V, et al. Genomic analysis reveals the presence of a class D beta-lactamase with broad substrate specificity in animal bite associated Capnocytophaga species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:657-662. doi:10.1007/s10096-016-2842-2

- Contou D, Sonneville R, Canoui-Poitrine F, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Clinical spectrum and short-term outcome of adult patients with purpura fulminans: a French multicenter retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1502-1511. doi:10.1007/s00134-018-5341-3

- Zenz W, Zoehrer B, Levin M, et al; . Use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in children with meningococcal purpura fulminans: a retrospective study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1777-1780. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000133667.86429.5d

- Wallace JS, Hall JC. Use of drug therapy to manage acute cutaneous necrosis of the skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:341-349.

- Squizzato A, Hunt BJ, Kinasewitz GT, et al. Supportive management strategies for disseminated intravascular coagulation. an international consensus. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:896-904. doi:10.1160/TH15-09-0740

- Herrera R, Hobar PC, Ginsburg CM. Surgical intervention for the complications of meningococcal-induced purpura fulminans. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:734-737. doi:10.1097/00006454-199408000-00011

- Pino PA, JA, F. Delayed surgical debridement and use of semiocclusive dressings for salvage of fingers after purpura fulminans. Hand (N Y). 2016;11:NP34-NP37. doi:10.1177/1558944716661996

- Gaucher S, J, Jarraya M. Human skin allografts as a useful adjunct in the treatment of purpura fulminans. J Wound Care. 2010;19:355-358. doi:10.12968/jowc.2010.19.8.77714

- Mazzone L, Schiestl C. Management of septic skin necroses. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:349-358. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1352530

- G, Torra-Bou JE, Manzano-Canillas ML, et al. Management of purpura fulminans skin lesions in a premature neonate with sepsis: a case study. J Wound Care. 2019;28:198-203. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.4.198

- Kizilocak H, Ozdemir N, Dikme G, et al. Homozygous protein C deficiency presenting as neonatal purpura fulminans: management with fresh frozen plasma, low molecular weight heparin and protein C concentrate. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45:315-318. doi:10.1007/s11239-017-1606-x

- Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al; . Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1202290

- Bernard GR, Vincent J-L, Laterre P-F, et al; . Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699-709. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103083441001

- Hage-Sleiman M, Derre N, Verdet C, et al. Meningococcal purpura fulminans and severe myocarditis with clinical meningitis but no meningeal inflammation: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:252. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3866-x

- Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24-33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man with a history of opioid abuse and splenectomy decades prior due to a motor vehicle accident was brought to an outside emergency department with confusion, slurred speech, and difficulty breathing. Over the next few days, he became febrile and hypotensive, requiring vasopressors. Clinical laboratory testing revealed a urine drug screen positive for opioids and a low platelet count in the setting of a rapidly evolving retiform purpuric rash.

The patient was transferred to our institution 6 days after initial presentation with primary diagnoses of septic shock with multiorgan failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods. After several days of broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care, cultures were reported as positive for Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Upon further questioning, the patient’s wife reported that the couple had a new puppy and that the patient often allowed the dog to bite him playfully and lick abrasions on his hands and legs. He had not received medical treatment for any of the dog’s bites.

On initial examination at the time of transfer, the patient’s skin was remarkable for diffuse areas of stellate and retiform purpura with dusky centers and necrosis of the nasal tip and earlobes. Both hands were purpuric, with necrosis of the fingertips (Figure 1A). The flank was marked by large areas of full-thickness sloughing of the skin (Figure 1B). The lower extremities were edematous, with some areas of stellate purpura and numerous large bullae that drained straw-colored fluid (Figure 1C). Lower extremity pulses were found with Doppler ultrasonography.

Given the presence of rapidly developing retiform purpura in the clinical context of severe sepsis, purpura fulminans (PF) was the primary consideration in the differential diagnosis. Levamisole-induced necrosis syndrome also was considered because of necrosis of the ears and nose as well as the history of substance use; however, the patient was not known to have a history of cocaine abuse, and a test of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative.

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed intravascular thrombi with epidermal and sweat gland necrosis, consistent with PF (Figure 2). Gram, Giemsa, and Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for organisms. Tissue culture remained negative. Repeat blood cultures demonstrated Candida parapsilosis fungemia. Respiratory culture was positive for budding yeast.

The patient was treated with antimicrobials, intravenous argatroban, and subcutaneous heparin. Purpura and bullae on the trunk slowly resolved with systemic therapy and wound care with petrolatum and nonadherent dressings. However, lesions on the nasal tip, all fingers of both hands, and several toes evolved into dry gangrene. The hospital course was complicated by renal failure requiring continuous renal replacement therapy; respiratory failure requiring ventilator support; and elevated levels of liver enzymes, consistent with involvement of the hepatic microvasculature.

The patient was in the medical intensive care unit at our institution for 2 weeks and was transferred to a burn center for specialized wound care. At transfer, he was still on a ventilator and receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Subsequently, the patient required a left above-the-knee amputation, right below-the-knee amputation, and amputation of several digits of the upper extremities. In the months after the amputations, he required multiple stump revisions and experienced surgical site infections that complicated healing.

Purpura fulminans is an uncommon syndrome characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarction of the skin. The condition commonly is associated with septic shock, causing vascular collapse and DIC. It often develops rapidly.

Because of associated high mortality, it is important to differentiate PF from other causes of cutaneous retiform purpura, including other causes of thrombosis and large vessel vasculitis. Leading causes of PF include infection and hereditary or acquired deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III. Regardless of cause, biopsy results demonstrate vascular thrombosis out of proportion to vasculitis. The mortality rate is 42% to 50%. The incidence of postinfectious sepsis sequelae in PF is higher than in survivors of sepsis only, especially amputation.1-3 Most patients do not die from complications of sepsis but from sequelae of the hypercoagulable and prothrombotic state associated with PF.4 Hemorrhagic infarction can affect the kidneys, brain, lungs, heart, eyes, and adrenal glands (ie, necrosis, namely Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome).5

The most common infectious cause of PF is sepsis secondary to Neisseria meningitidis, with as many as 25% of infected patients developing PF.6Streptococcus pneumoniae is another common cause. Other important causative organisms include Streptococcus pyogenes; Staphylococcus aureus (in the setting of intravenous substance use); Klebsiella oxytoca; Klebsiella aerogenes; rickettsial organisms; and viruses, including cytomegalovirus and varicella-zoster virus.2,7-13 Two earlier cases associated with Capnocytophaga were characterized by concomitant renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hemolytic anemia, and DIC.14

It is estimated that Capnocytophaga causes 11% to 46% of all cases of sepsis15; sepsis resulting from Capnocytophaga has extremely poor outcomes, with mortality reaching as high as 60%. The organism is part of the normal oral flora of cats and dogs, and a bite (less often, a scratch) is the cause of most Capnocytophaga infections. The clinical spectrum of C canimorsus infection associated with dog saliva exposure more commonly includes cellulitis at or around the site of inoculation, meningitis, and endocarditis.16

Although patients affected by PF can be young and healthy, several risk factors for PF have been identified2,6,16: asplenia, an immunocompromised state, systemic corticosteroid use, cirrhosis, and alcoholism. Asplenic patients have been shown to be particularly susceptible to systemic Capnocytophaga infection; when bitten by a dog, they should be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to cover Capnocytophaga.17 Immunocompetent patients rarely develop severe infection with Capnocytophaga.16,18,19 The complement system in particular is critically important in defending against C canimorsus.20

The underlying pathophysiology of acute infectious PF is multifactorial, encompassing increased expression of procoagulant tissue factor by monocytes and endothelial cells in the presence of bacterial pathogens. Dysfunction of protein C, an anticoagulant component of the coagulation cascade, often is cited as a crucial derangement leading to the development of a prothrombotic state in acute infectious PF.21 Serum protein S and antithrombin deficiency also can play a role.22 Specific in vitro examination of C canimorsus has revealed a protease that catalyzes N-terminal cleavage of procoagulant factor X, resulting in loss of function.15

Retiform purpura is a hallmark feature of PF, often beginning as nonblanching erythema with localized edema and petechiae before evolving into the characteristic stellate lesions with hemorrhagic bullae and subsequent necrosis.23 Pathologic examination reveals microthrombi involving arterioles and smaller vessels.24 There typically is laboratory evidence of DIC in PF, including elevated prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer, and a decreased fibrinogen level.6,23

Capnocytophaga bacteria are challenging to grow on standard culture media. Optimal media for growth include 5% sheep’s blood and chocolate agar.16 Polymerase chain reaction can identify Capnocytophaga; in cases in which blood culture does not produce growth, 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of tissue from skin biopsy has identified the pathogen.25

Some Capnocytophaga isolates have been shown to produce beta-lactamase; individual strains can be resistant to penicillins, cephalosporins, and imipenem.26 Factors associated with an increased risk for death include decreased leukocyte and platelet counts and an increased level of arterial lactate.27

Empiric antibiotic therapy for Capnocytophaga sepsis should include a beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitor, such as piperacillin-tazobactam. Management of DIC can include therapeutic heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin and prophylactic platelet transfusion to maintain a pre-established value.28-30 Debridement should be conservative; it is important to wait for definite delineation between viable and necrotic tissue,31 which might take several months.32 Human skin allografts, in addition to artificial skin, are utilized as supplemental therapy for more rapid wound closure after removal of necrotic tissue.33,34 Hyperoxygenated fatty acids have been noted to aid in more rapid wound healing in infants with PF.35

Fresh frozen plasma is one method to replace missing factors, but it contains little protein C.36 Outcomes with recombinant human activated protein C (drotrecogin alfa) are mixed, and studies have shown no benefit in reducing the risk for death.37,38 Protein C concentrate has shown therapeutic benefit in some case reports and small retrospective studies.4 In one case report, protein C concentrate and heparin were utilized in combination with antithrombin III.21

Hyperbaric O2 might be of benefit when initiated within 5 days after onset of PF. However, hyperbaric O2 does carry risk; O2 toxicity, barotrauma, and barriers to timely resuscitation when the patient is inside the pressurized chamber can occur.2

There is a single report of successful use of the vasodilator iloprost for meningococcal PF without need for surgical intervention; the team also utilized topical nitroglycerin patches on the fingers to avoid digital amputation.39 Epoprostenol, tissue plasminogen activator, and antithrombin have been utilized in cases of extensive PF. Fibrinolytic therapy might have some utility, but only in a setting of malignancy-associated DIC.40

Treatment of acute infectious PF lacks a high level of evidence. Options include replacement of anticoagulant factors, anticoagulant therapy, hyperbaric O2, topical and systemic vasodilators, and, in the setting of underlying cancer, fibrinolytics. Even with therapy, prognosis is guarded.

To the Editor:

A 56-year-old man with a history of opioid abuse and splenectomy decades prior due to a motor vehicle accident was brought to an outside emergency department with confusion, slurred speech, and difficulty breathing. Over the next few days, he became febrile and hypotensive, requiring vasopressors. Clinical laboratory testing revealed a urine drug screen positive for opioids and a low platelet count in the setting of a rapidly evolving retiform purpuric rash.

The patient was transferred to our institution 6 days after initial presentation with primary diagnoses of septic shock with multiorgan failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Blood cultures were positive for gram-negative rods. After several days of broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care, cultures were reported as positive for Capnocytophaga canimorsus. Upon further questioning, the patient’s wife reported that the couple had a new puppy and that the patient often allowed the dog to bite him playfully and lick abrasions on his hands and legs. He had not received medical treatment for any of the dog’s bites.

On initial examination at the time of transfer, the patient’s skin was remarkable for diffuse areas of stellate and retiform purpura with dusky centers and necrosis of the nasal tip and earlobes. Both hands were purpuric, with necrosis of the fingertips (Figure 1A). The flank was marked by large areas of full-thickness sloughing of the skin (Figure 1B). The lower extremities were edematous, with some areas of stellate purpura and numerous large bullae that drained straw-colored fluid (Figure 1C). Lower extremity pulses were found with Doppler ultrasonography.

Given the presence of rapidly developing retiform purpura in the clinical context of severe sepsis, purpura fulminans (PF) was the primary consideration in the differential diagnosis. Levamisole-induced necrosis syndrome also was considered because of necrosis of the ears and nose as well as the history of substance use; however, the patient was not known to have a history of cocaine abuse, and a test of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative.

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed intravascular thrombi with epidermal and sweat gland necrosis, consistent with PF (Figure 2). Gram, Giemsa, and Gomori methenamine-silver stains were negative for organisms. Tissue culture remained negative. Repeat blood cultures demonstrated Candida parapsilosis fungemia. Respiratory culture was positive for budding yeast.

The patient was treated with antimicrobials, intravenous argatroban, and subcutaneous heparin. Purpura and bullae on the trunk slowly resolved with systemic therapy and wound care with petrolatum and nonadherent dressings. However, lesions on the nasal tip, all fingers of both hands, and several toes evolved into dry gangrene. The hospital course was complicated by renal failure requiring continuous renal replacement therapy; respiratory failure requiring ventilator support; and elevated levels of liver enzymes, consistent with involvement of the hepatic microvasculature.

The patient was in the medical intensive care unit at our institution for 2 weeks and was transferred to a burn center for specialized wound care. At transfer, he was still on a ventilator and receiving continuous renal replacement therapy. Subsequently, the patient required a left above-the-knee amputation, right below-the-knee amputation, and amputation of several digits of the upper extremities. In the months after the amputations, he required multiple stump revisions and experienced surgical site infections that complicated healing.

Purpura fulminans is an uncommon syndrome characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarction of the skin. The condition commonly is associated with septic shock, causing vascular collapse and DIC. It often develops rapidly.

Because of associated high mortality, it is important to differentiate PF from other causes of cutaneous retiform purpura, including other causes of thrombosis and large vessel vasculitis. Leading causes of PF include infection and hereditary or acquired deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III. Regardless of cause, biopsy results demonstrate vascular thrombosis out of proportion to vasculitis. The mortality rate is 42% to 50%. The incidence of postinfectious sepsis sequelae in PF is higher than in survivors of sepsis only, especially amputation.1-3 Most patients do not die from complications of sepsis but from sequelae of the hypercoagulable and prothrombotic state associated with PF.4 Hemorrhagic infarction can affect the kidneys, brain, lungs, heart, eyes, and adrenal glands (ie, necrosis, namely Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome).5

The most common infectious cause of PF is sepsis secondary to Neisseria meningitidis, with as many as 25% of infected patients developing PF.6Streptococcus pneumoniae is another common cause. Other important causative organisms include Streptococcus pyogenes; Staphylococcus aureus (in the setting of intravenous substance use); Klebsiella oxytoca; Klebsiella aerogenes; rickettsial organisms; and viruses, including cytomegalovirus and varicella-zoster virus.2,7-13 Two earlier cases associated with Capnocytophaga were characterized by concomitant renal failure, metabolic acidosis, hemolytic anemia, and DIC.14

It is estimated that Capnocytophaga causes 11% to 46% of all cases of sepsis15; sepsis resulting from Capnocytophaga has extremely poor outcomes, with mortality reaching as high as 60%. The organism is part of the normal oral flora of cats and dogs, and a bite (less often, a scratch) is the cause of most Capnocytophaga infections. The clinical spectrum of C canimorsus infection associated with dog saliva exposure more commonly includes cellulitis at or around the site of inoculation, meningitis, and endocarditis.16

Although patients affected by PF can be young and healthy, several risk factors for PF have been identified2,6,16: asplenia, an immunocompromised state, systemic corticosteroid use, cirrhosis, and alcoholism. Asplenic patients have been shown to be particularly susceptible to systemic Capnocytophaga infection; when bitten by a dog, they should be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to cover Capnocytophaga.17 Immunocompetent patients rarely develop severe infection with Capnocytophaga.16,18,19 The complement system in particular is critically important in defending against C canimorsus.20

The underlying pathophysiology of acute infectious PF is multifactorial, encompassing increased expression of procoagulant tissue factor by monocytes and endothelial cells in the presence of bacterial pathogens. Dysfunction of protein C, an anticoagulant component of the coagulation cascade, often is cited as a crucial derangement leading to the development of a prothrombotic state in acute infectious PF.21 Serum protein S and antithrombin deficiency also can play a role.22 Specific in vitro examination of C canimorsus has revealed a protease that catalyzes N-terminal cleavage of procoagulant factor X, resulting in loss of function.15

Retiform purpura is a hallmark feature of PF, often beginning as nonblanching erythema with localized edema and petechiae before evolving into the characteristic stellate lesions with hemorrhagic bullae and subsequent necrosis.23 Pathologic examination reveals microthrombi involving arterioles and smaller vessels.24 There typically is laboratory evidence of DIC in PF, including elevated prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, thrombocytopenia, elevated D-dimer, and a decreased fibrinogen level.6,23

Capnocytophaga bacteria are challenging to grow on standard culture media. Optimal media for growth include 5% sheep’s blood and chocolate agar.16 Polymerase chain reaction can identify Capnocytophaga; in cases in which blood culture does not produce growth, 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of tissue from skin biopsy has identified the pathogen.25

Some Capnocytophaga isolates have been shown to produce beta-lactamase; individual strains can be resistant to penicillins, cephalosporins, and imipenem.26 Factors associated with an increased risk for death include decreased leukocyte and platelet counts and an increased level of arterial lactate.27

Empiric antibiotic therapy for Capnocytophaga sepsis should include a beta-lactam and beta-lactamase inhibitor, such as piperacillin-tazobactam. Management of DIC can include therapeutic heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin and prophylactic platelet transfusion to maintain a pre-established value.28-30 Debridement should be conservative; it is important to wait for definite delineation between viable and necrotic tissue,31 which might take several months.32 Human skin allografts, in addition to artificial skin, are utilized as supplemental therapy for more rapid wound closure after removal of necrotic tissue.33,34 Hyperoxygenated fatty acids have been noted to aid in more rapid wound healing in infants with PF.35

Fresh frozen plasma is one method to replace missing factors, but it contains little protein C.36 Outcomes with recombinant human activated protein C (drotrecogin alfa) are mixed, and studies have shown no benefit in reducing the risk for death.37,38 Protein C concentrate has shown therapeutic benefit in some case reports and small retrospective studies.4 In one case report, protein C concentrate and heparin were utilized in combination with antithrombin III.21

Hyperbaric O2 might be of benefit when initiated within 5 days after onset of PF. However, hyperbaric O2 does carry risk; O2 toxicity, barotrauma, and barriers to timely resuscitation when the patient is inside the pressurized chamber can occur.2

There is a single report of successful use of the vasodilator iloprost for meningococcal PF without need for surgical intervention; the team also utilized topical nitroglycerin patches on the fingers to avoid digital amputation.39 Epoprostenol, tissue plasminogen activator, and antithrombin have been utilized in cases of extensive PF. Fibrinolytic therapy might have some utility, but only in a setting of malignancy-associated DIC.40

Treatment of acute infectious PF lacks a high level of evidence. Options include replacement of anticoagulant factors, anticoagulant therapy, hyperbaric O2, topical and systemic vasodilators, and, in the setting of underlying cancer, fibrinolytics. Even with therapy, prognosis is guarded.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Dutta A. Purpura fulminans: a cutaneous marker of disseminated intravascular coagulation. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:41.

- Ursin Rein P, Jacobsen D, Ormaasen V, et al. Pneumococcal sepsis requiring mechanical ventilation: cohort study in 38 patients with rapid progression to septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:1428-1435. doi:10.1111/aas

- Contou D, Canoui-Poitrine F, Coudroy R, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Long-term quality of life in adult patients surviving purpura fulminans: an exposed-unexposed multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:332-340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy901

- Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.199919

- Karimi K, Odhav A, Kollipara R, et al. Acute cutaneous necrosis: a guide to early diagnosis and treatment. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:425-437. doi:10.1177/1203475417708164

- Colling ME, Bendapudi PK. Purpura fulminans: mechanism and management of dysregulated hemostasis. Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:69-76. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2017.10.001

- Kankeu Fonkoua L, Zhang S, Canty E, et al. Purpura fulminans from reduced protein S following cytomegalovirus and varicella infection. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:491-495. doi:10.1002/ajh.25386

- Okuzono S, Ishimura M, Kanno S, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-purpura fulminans as an invasive form of group A streptococcal infection. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12941-018-0282-9

- Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, Srinivas BH, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus: an uncommon organism. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:132-133. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178093

- Saini S, Duncan RA. Sloughing skin in intravenous drug user. IDCases. 2018;12:74-75. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.03.007

- Tsubouchi N, Tsurukiri J, Numata J, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by Klebsiella oxytoca. Intern Med. 2019;58:1801-1802. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.2350-18

- Yamamoto S, Ito R. Acute infectious purpura fulminans with Enterobacter aerogenes post-neurosurgery. IDCases. 2019;15:e00514. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00514

- Dalugama C, Gawarammana IB. Rare presentation of rickettsial infection as purpura fulminans: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:145. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1672-5

- Kazandjieva J, Antonov D, Kamarashev J, et al. Acrally distributed dermatoses: vascular dermatoses (purpura and vasculitis). Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:68-80. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.013

- Hack K, Renzi F, Hess E, et al. Inactivation of human coagulation factor X by a protease of the pathogen Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:487-499. doi:10.1111/jth.13605

- Zajkowska J, M, Falkowski D, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus—an underestimated danger after dog or cat bite - review of literature. Przegl Epidemiol. 2016;70:289-295.

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet. 2011;378:86-97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6

- Behrend Christiansen C, Berg RMG, Plovsing RR, et al. Two cases of infectious purpura fulminans and septic shock caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus transmitted from dogs. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:635-639. doi:10.3109/00365548.2012.672765

- Ruddock TL, Rindler JM, Bergfeld WF. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia in an asplenic patient. Cutis. 1997;60:95-97.

- Mantovani E, Busani S, Biagioni E, et al. Purpura fulminans and septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus after dog bite: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Crit Care. 2018;2018:7090268. doi:10.1155/2018/7090268

- Bendapudi PK, Robbins A, LeBoeuf N, et al. Persistence of endothelial thrombomodulin in a patient with infectious purpura fulminans treated with protein C concentrate. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2917-2921. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024430

- Lerolle N, Carlotti A, Melican K, et al. Assessment of the interplay between blood and skin vascular abnormalities in adult purpura fulminans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:684-692. doi:10.1164/rccm.201302-0228OC.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC III. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.043

- Adcock DM, Hicks MJ. Dermatopathology of skin necrosis associated with purpura fulminans. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1990;16:283-292. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1002681

- Dautzenberg KHW, Polderman FN, van Suylen RJ, et al. Purpura fulminans mimicking toxic epidermal necrolysis—additional value of 16S rRNA sequencing and skin biopsy. Neth J Med. 2017;75:165-168.

- Zangenah S, Andersson AF, V, et al. Genomic analysis reveals the presence of a class D beta-lactamase with broad substrate specificity in animal bite associated Capnocytophaga species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:657-662. doi:10.1007/s10096-016-2842-2

- Contou D, Sonneville R, Canoui-Poitrine F, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Clinical spectrum and short-term outcome of adult patients with purpura fulminans: a French multicenter retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1502-1511. doi:10.1007/s00134-018-5341-3

- Zenz W, Zoehrer B, Levin M, et al; . Use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in children with meningococcal purpura fulminans: a retrospective study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1777-1780. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000133667.86429.5d

- Wallace JS, Hall JC. Use of drug therapy to manage acute cutaneous necrosis of the skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:341-349.

- Squizzato A, Hunt BJ, Kinasewitz GT, et al. Supportive management strategies for disseminated intravascular coagulation. an international consensus. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:896-904. doi:10.1160/TH15-09-0740

- Herrera R, Hobar PC, Ginsburg CM. Surgical intervention for the complications of meningococcal-induced purpura fulminans. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:734-737. doi:10.1097/00006454-199408000-00011

- Pino PA, JA, F. Delayed surgical debridement and use of semiocclusive dressings for salvage of fingers after purpura fulminans. Hand (N Y). 2016;11:NP34-NP37. doi:10.1177/1558944716661996

- Gaucher S, J, Jarraya M. Human skin allografts as a useful adjunct in the treatment of purpura fulminans. J Wound Care. 2010;19:355-358. doi:10.12968/jowc.2010.19.8.77714

- Mazzone L, Schiestl C. Management of septic skin necroses. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:349-358. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1352530

- G, Torra-Bou JE, Manzano-Canillas ML, et al. Management of purpura fulminans skin lesions in a premature neonate with sepsis: a case study. J Wound Care. 2019;28:198-203. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.4.198

- Kizilocak H, Ozdemir N, Dikme G, et al. Homozygous protein C deficiency presenting as neonatal purpura fulminans: management with fresh frozen plasma, low molecular weight heparin and protein C concentrate. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45:315-318. doi:10.1007/s11239-017-1606-x

- Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al; . Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1202290

- Bernard GR, Vincent J-L, Laterre P-F, et al; . Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699-709. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103083441001

- Hage-Sleiman M, Derre N, Verdet C, et al. Meningococcal purpura fulminans and severe myocarditis with clinical meningitis but no meningeal inflammation: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:252. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3866-x

- Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24-33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Dutta A. Purpura fulminans: a cutaneous marker of disseminated intravascular coagulation. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:41.

- Ursin Rein P, Jacobsen D, Ormaasen V, et al. Pneumococcal sepsis requiring mechanical ventilation: cohort study in 38 patients with rapid progression to septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:1428-1435. doi:10.1111/aas

- Contou D, Canoui-Poitrine F, Coudroy R, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Long-term quality of life in adult patients surviving purpura fulminans: an exposed-unexposed multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:332-340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy901

- Chalmers E, Cooper P, Forman K, et al. Purpura fulminans: recognition, diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:1066-1071. doi:10.1136/adc.2010.199919

- Karimi K, Odhav A, Kollipara R, et al. Acute cutaneous necrosis: a guide to early diagnosis and treatment. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:425-437. doi:10.1177/1203475417708164

- Colling ME, Bendapudi PK. Purpura fulminans: mechanism and management of dysregulated hemostasis. Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:69-76. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2017.10.001

- Kankeu Fonkoua L, Zhang S, Canty E, et al. Purpura fulminans from reduced protein S following cytomegalovirus and varicella infection. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:491-495. doi:10.1002/ajh.25386

- Okuzono S, Ishimura M, Kanno S, et al. Streptococcus pyogenes-purpura fulminans as an invasive form of group A streptococcal infection. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12941-018-0282-9

- Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, Srinivas BH, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus: an uncommon organism. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:132-133. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.178093

- Saini S, Duncan RA. Sloughing skin in intravenous drug user. IDCases. 2018;12:74-75. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.03.007

- Tsubouchi N, Tsurukiri J, Numata J, et al. Acute infectious purpura fulminans caused by Klebsiella oxytoca. Intern Med. 2019;58:1801-1802. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.2350-18

- Yamamoto S, Ito R. Acute infectious purpura fulminans with Enterobacter aerogenes post-neurosurgery. IDCases. 2019;15:e00514. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2019.e00514

- Dalugama C, Gawarammana IB. Rare presentation of rickettsial infection as purpura fulminans: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:145. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1672-5

- Kazandjieva J, Antonov D, Kamarashev J, et al. Acrally distributed dermatoses: vascular dermatoses (purpura and vasculitis). Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:68-80. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.013

- Hack K, Renzi F, Hess E, et al. Inactivation of human coagulation factor X by a protease of the pathogen Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:487-499. doi:10.1111/jth.13605

- Zajkowska J, M, Falkowski D, et al. Capnocytophaga canimorsus—an underestimated danger after dog or cat bite - review of literature. Przegl Epidemiol. 2016;70:289-295.

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet. 2011;378:86-97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6

- Behrend Christiansen C, Berg RMG, Plovsing RR, et al. Two cases of infectious purpura fulminans and septic shock caused by Capnocytophaga canimorsus transmitted from dogs. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:635-639. doi:10.3109/00365548.2012.672765

- Ruddock TL, Rindler JM, Bergfeld WF. Capnocytophaga canimorsus septicemia in an asplenic patient. Cutis. 1997;60:95-97.

- Mantovani E, Busani S, Biagioni E, et al. Purpura fulminans and septic shock due to Capnocytophaga canimorsus after dog bite: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Crit Care. 2018;2018:7090268. doi:10.1155/2018/7090268

- Bendapudi PK, Robbins A, LeBoeuf N, et al. Persistence of endothelial thrombomodulin in a patient with infectious purpura fulminans treated with protein C concentrate. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2917-2921. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024430

- Lerolle N, Carlotti A, Melican K, et al. Assessment of the interplay between blood and skin vascular abnormalities in adult purpura fulminans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:684-692. doi:10.1164/rccm.201302-0228OC.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC III. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.01.043

- Adcock DM, Hicks MJ. Dermatopathology of skin necrosis associated with purpura fulminans. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1990;16:283-292. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1002681

- Dautzenberg KHW, Polderman FN, van Suylen RJ, et al. Purpura fulminans mimicking toxic epidermal necrolysis—additional value of 16S rRNA sequencing and skin biopsy. Neth J Med. 2017;75:165-168.

- Zangenah S, Andersson AF, V, et al. Genomic analysis reveals the presence of a class D beta-lactamase with broad substrate specificity in animal bite associated Capnocytophaga species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:657-662. doi:10.1007/s10096-016-2842-2

- Contou D, Sonneville R, Canoui-Poitrine F, et al; Hopeful Study Group. Clinical spectrum and short-term outcome of adult patients with purpura fulminans: a French multicenter retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1502-1511. doi:10.1007/s00134-018-5341-3

- Zenz W, Zoehrer B, Levin M, et al; . Use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in children with meningococcal purpura fulminans: a retrospective study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1777-1780. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000133667.86429.5d

- Wallace JS, Hall JC. Use of drug therapy to manage acute cutaneous necrosis of the skin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:341-349.

- Squizzato A, Hunt BJ, Kinasewitz GT, et al. Supportive management strategies for disseminated intravascular coagulation. an international consensus. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:896-904. doi:10.1160/TH15-09-0740

- Herrera R, Hobar PC, Ginsburg CM. Surgical intervention for the complications of meningococcal-induced purpura fulminans. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:734-737. doi:10.1097/00006454-199408000-00011

- Pino PA, JA, F. Delayed surgical debridement and use of semiocclusive dressings for salvage of fingers after purpura fulminans. Hand (N Y). 2016;11:NP34-NP37. doi:10.1177/1558944716661996

- Gaucher S, J, Jarraya M. Human skin allografts as a useful adjunct in the treatment of purpura fulminans. J Wound Care. 2010;19:355-358. doi:10.12968/jowc.2010.19.8.77714

- Mazzone L, Schiestl C. Management of septic skin necroses. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:349-358. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1352530

- G, Torra-Bou JE, Manzano-Canillas ML, et al. Management of purpura fulminans skin lesions in a premature neonate with sepsis: a case study. J Wound Care. 2019;28:198-203. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.4.198

- Kizilocak H, Ozdemir N, Dikme G, et al. Homozygous protein C deficiency presenting as neonatal purpura fulminans: management with fresh frozen plasma, low molecular weight heparin and protein C concentrate. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2018;45:315-318. doi:10.1007/s11239-017-1606-x

- Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al; . Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1202290

- Bernard GR, Vincent J-L, Laterre P-F, et al; . Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699-709. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103083441001

- Hage-Sleiman M, Derre N, Verdet C, et al. Meningococcal purpura fulminans and severe myocarditis with clinical meningitis but no meningeal inflammation: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:252. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3866-x

- Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24-33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x

Practice Points

- Capnocytophaga species are fastidious, slow-growing microorganisms. It is important, therefore, to maintain a high degree of suspicion and alertthe microbiology laboratory to increase the likelihood of isolation.

- Patients should be cautioned regarding the need for prophylactic antibiotics in the event of an animal bite; asplenic patients are at particular risk for infection.

- In patients with severe purpura fulminans and a gangrenous limb, it is important to allow adequate time for demarcation of gangrene and not rush to amputation.

Purpura Fulminans Induced by Vibrio vulnificus

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans (PF) is an acute, life-threatening condition characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic necrosis of the skin. It classically presents as retiform purpura with branched or angular purpuric lesions. Purpura fulminans often occurs in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation, secondary to sepsis, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune disease, and congenital or acquired protein C or S deficiency, among other abnormalities.1 Rapid identification and treatment of the underlying cause are mainstays of management. We report a case of PF secondary to Vibrio vulnificus infection and highlight the importance of timely consideration of this etiologic agent due to the high mortality rate and specific treatment required.

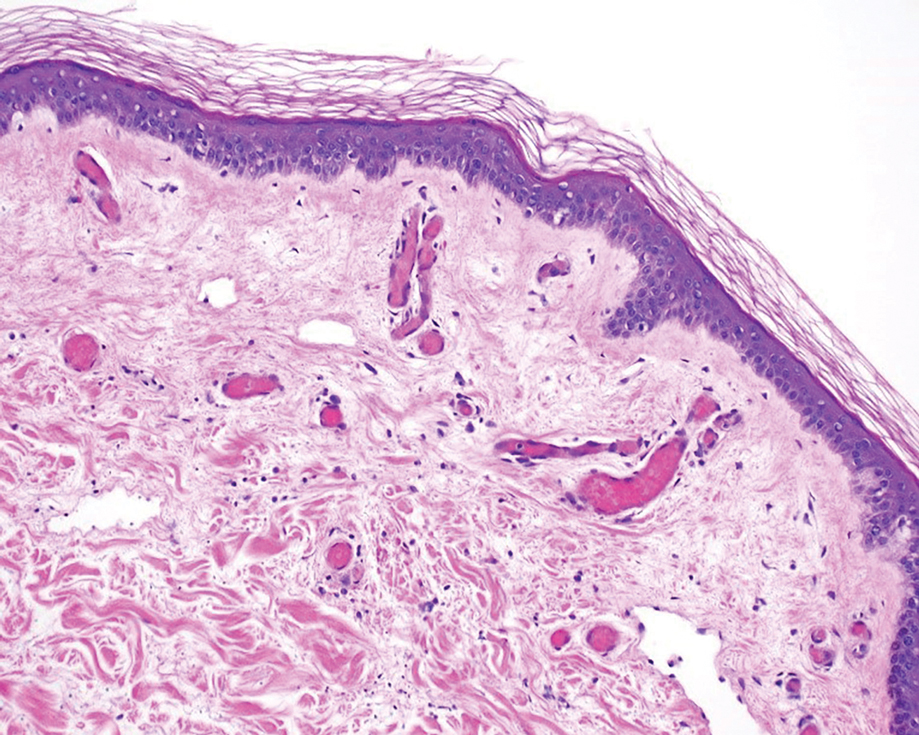

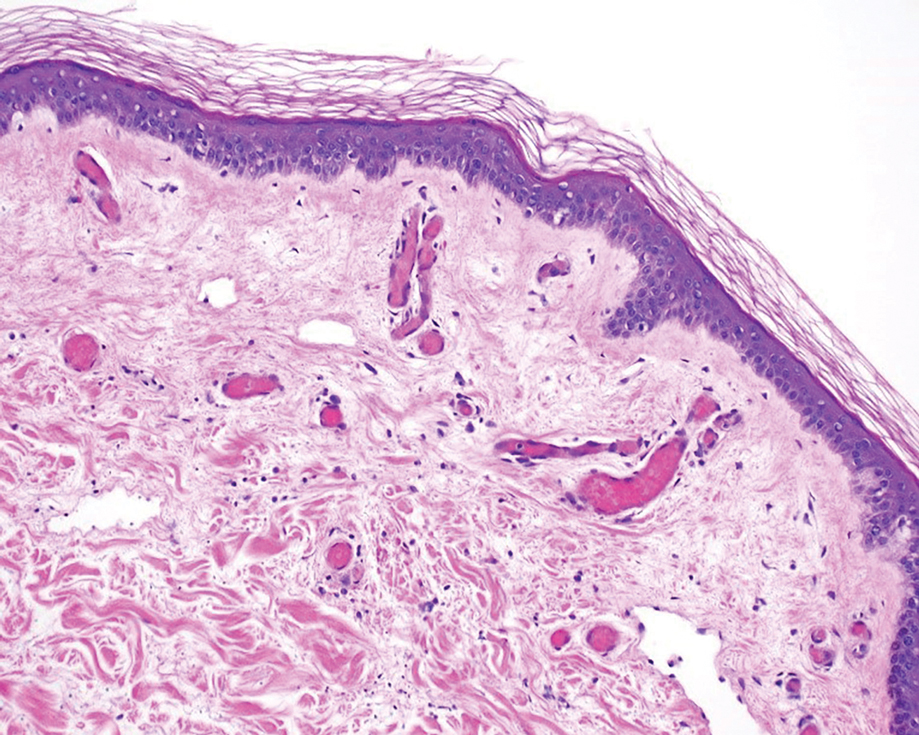

A 58-year-old man with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B virus presented with pain, swelling, and localized erythema affecting both legs as well as a fever. He reported vomiting blood and an episode of bloody diarrhea over the preceding 24 hours. He denied exposure to sick contacts or a history of autoimmune disease. At initial presentation to the emergency department, physical examination revealed few scattered, sharply demarcated, erythematous to violaceous patches that rapidly progressed overnight to hemorrhagic bullae and widespread retiform purpuric patches on both legs (Figure 1). As the patient’s skin condition worsened, he had a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg and a pulse rate of 110/min. Serum analysis was notable for mild leukocytosis (10.74×109/L [reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L), thrombocytopenia (39×109/L [reference range, 150–450×109/L]), and decreased C3 (25 mg/dL [reference range, 81–157 mg/dL]) and C4 (8 mg/dL [reference range, 13–39 mg/dL]). Laboratory findings also were remarkable for prothrombin time (23.3 seconds [reference range, 8.8–12.3 seconds]), partial thromboplastin time (52.5 seconds [reference range, 23.6–35.8 seconds]), and international normalized ratio (2.01 [reference range, 0.8–1.13]). Aspartate transaminase (237 U/L [reference range, 11–39 U/L]) and alanine transaminase (80 U/L [reference range, 11–35 U/L]) were elevated, while antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, serum immunoglobulin, and cryoglobulins were unremarkable. Punch biopsies of the left thigh were performed, and histopathology revealed small vessel thrombosis and ischemic changes consistent with PF (Figure 2). Vancomycin, clindamycin, cefepime injection, and piperacillin-tazobactam were administered intravenously for empiric broad-spectrum sepsis coverage. Within hours, the patient experienced refractory septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation and died from pulmonary embolism and subsequent cardiac arrest. Tissue and blood cultures grew V vulnificus.

Vibrio vulnificus is a gram-negative bacillus and a rare cause of primary septicemia following consumption of shellfish, especially oysters. Wounds exposed to saltwater or brackish water contaminated with the microorganism can produce soft-tissue infections. Individuals with chronic liver disease are at greater risk for V vulnificus infection.2 The clinical presentation of V vulnificus includes early cellulitislike patches, late purpura with hemorrhagic bullae, and rapidly progressing shock.3

Mortality rates from V vulnificus infection are high.4 Therefore, it is recommended to presumptively diagnose V vulnificus septicemia in any individual at risk for infection who presents with the characteristic history in the setting of hypotension, fever, or septic shock. It is crucial for providers to be aware that broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used for sepsis are inadequate for the treatment of V vulnificus. Immediate treatment with tetracycline (minocycline or doxycycline) and a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone injection) or in combination with ciprofloxacin has been proven effective.4,5

Vibrio vulnificus rarely is described in the literature as inducing PF. In one previously reported case, the patient was otherwise healthy and managed to recover following antibiotic therapy and wound debridement,6 whereas in another case the patient had undiagnosed liver cirrhosis and died from the infection.6,7 In the latter case, the patient presented to the emergency department in a coma. Our patient did not have the clinical signs of sepsis upon initial presentation to the emergency department. It is possible the infection rapidly progressed because of his underlying liver disease. Genotyping analysis of V vulnificus has shown that strains with low pathogenicity can cause primary septicemia in humans.7

Our case reinforces the need to quickly recognize V vulnificus as a rare underlying cause of PF and administer the appropriate treatment.

- Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:586-592.

- Tacket CO, Brenner F, Blake PA. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:558-561.

- Blake PA, Merson MH, Weaver RE et al. Disease caused by a marine Vibrio: clinical characteristics and epidemiology. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1-5.

- Liu JW, Lee IK, Tang HJ, et al. Prognostic factors and antibiotics in Vibrio vulnificus septicemia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2117-2123.

- Chen SC, Lee YT, Tsai SJ, et al. Antibiotic therapy for necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus: retrospective analysis of an 8 year period.J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:488-493.

- Choi HJ, Lee DK, Lee MW et al. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia presenting as purpura fulminans. J Dermatol. 2005;32:48-51.

- Hori M, Nakayama A, Kitagawa D et al. A case of Vibrio vulnificus infection complicated with fulminant purpura: gene and biotype analysis of the pathogen. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005096.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans (PF) is an acute, life-threatening condition characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic necrosis of the skin. It classically presents as retiform purpura with branched or angular purpuric lesions. Purpura fulminans often occurs in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation, secondary to sepsis, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune disease, and congenital or acquired protein C or S deficiency, among other abnormalities.1 Rapid identification and treatment of the underlying cause are mainstays of management. We report a case of PF secondary to Vibrio vulnificus infection and highlight the importance of timely consideration of this etiologic agent due to the high mortality rate and specific treatment required.

A 58-year-old man with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B virus presented with pain, swelling, and localized erythema affecting both legs as well as a fever. He reported vomiting blood and an episode of bloody diarrhea over the preceding 24 hours. He denied exposure to sick contacts or a history of autoimmune disease. At initial presentation to the emergency department, physical examination revealed few scattered, sharply demarcated, erythematous to violaceous patches that rapidly progressed overnight to hemorrhagic bullae and widespread retiform purpuric patches on both legs (Figure 1). As the patient’s skin condition worsened, he had a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg and a pulse rate of 110/min. Serum analysis was notable for mild leukocytosis (10.74×109/L [reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L), thrombocytopenia (39×109/L [reference range, 150–450×109/L]), and decreased C3 (25 mg/dL [reference range, 81–157 mg/dL]) and C4 (8 mg/dL [reference range, 13–39 mg/dL]). Laboratory findings also were remarkable for prothrombin time (23.3 seconds [reference range, 8.8–12.3 seconds]), partial thromboplastin time (52.5 seconds [reference range, 23.6–35.8 seconds]), and international normalized ratio (2.01 [reference range, 0.8–1.13]). Aspartate transaminase (237 U/L [reference range, 11–39 U/L]) and alanine transaminase (80 U/L [reference range, 11–35 U/L]) were elevated, while antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, serum immunoglobulin, and cryoglobulins were unremarkable. Punch biopsies of the left thigh were performed, and histopathology revealed small vessel thrombosis and ischemic changes consistent with PF (Figure 2). Vancomycin, clindamycin, cefepime injection, and piperacillin-tazobactam were administered intravenously for empiric broad-spectrum sepsis coverage. Within hours, the patient experienced refractory septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation and died from pulmonary embolism and subsequent cardiac arrest. Tissue and blood cultures grew V vulnificus.

Vibrio vulnificus is a gram-negative bacillus and a rare cause of primary septicemia following consumption of shellfish, especially oysters. Wounds exposed to saltwater or brackish water contaminated with the microorganism can produce soft-tissue infections. Individuals with chronic liver disease are at greater risk for V vulnificus infection.2 The clinical presentation of V vulnificus includes early cellulitislike patches, late purpura with hemorrhagic bullae, and rapidly progressing shock.3

Mortality rates from V vulnificus infection are high.4 Therefore, it is recommended to presumptively diagnose V vulnificus septicemia in any individual at risk for infection who presents with the characteristic history in the setting of hypotension, fever, or septic shock. It is crucial for providers to be aware that broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used for sepsis are inadequate for the treatment of V vulnificus. Immediate treatment with tetracycline (minocycline or doxycycline) and a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone injection) or in combination with ciprofloxacin has been proven effective.4,5

Vibrio vulnificus rarely is described in the literature as inducing PF. In one previously reported case, the patient was otherwise healthy and managed to recover following antibiotic therapy and wound debridement,6 whereas in another case the patient had undiagnosed liver cirrhosis and died from the infection.6,7 In the latter case, the patient presented to the emergency department in a coma. Our patient did not have the clinical signs of sepsis upon initial presentation to the emergency department. It is possible the infection rapidly progressed because of his underlying liver disease. Genotyping analysis of V vulnificus has shown that strains with low pathogenicity can cause primary septicemia in humans.7

Our case reinforces the need to quickly recognize V vulnificus as a rare underlying cause of PF and administer the appropriate treatment.

To the Editor:

Purpura fulminans (PF) is an acute, life-threatening condition characterized by intravascular thrombosis and hemorrhagic necrosis of the skin. It classically presents as retiform purpura with branched or angular purpuric lesions. Purpura fulminans often occurs in the setting of disseminated intravascular coagulation, secondary to sepsis, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune disease, and congenital or acquired protein C or S deficiency, among other abnormalities.1 Rapid identification and treatment of the underlying cause are mainstays of management. We report a case of PF secondary to Vibrio vulnificus infection and highlight the importance of timely consideration of this etiologic agent due to the high mortality rate and specific treatment required.

A 58-year-old man with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis B virus presented with pain, swelling, and localized erythema affecting both legs as well as a fever. He reported vomiting blood and an episode of bloody diarrhea over the preceding 24 hours. He denied exposure to sick contacts or a history of autoimmune disease. At initial presentation to the emergency department, physical examination revealed few scattered, sharply demarcated, erythematous to violaceous patches that rapidly progressed overnight to hemorrhagic bullae and widespread retiform purpuric patches on both legs (Figure 1). As the patient’s skin condition worsened, he had a blood pressure of 80/50 mm Hg and a pulse rate of 110/min. Serum analysis was notable for mild leukocytosis (10.74×109/L [reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L), thrombocytopenia (39×109/L [reference range, 150–450×109/L]), and decreased C3 (25 mg/dL [reference range, 81–157 mg/dL]) and C4 (8 mg/dL [reference range, 13–39 mg/dL]). Laboratory findings also were remarkable for prothrombin time (23.3 seconds [reference range, 8.8–12.3 seconds]), partial thromboplastin time (52.5 seconds [reference range, 23.6–35.8 seconds]), and international normalized ratio (2.01 [reference range, 0.8–1.13]). Aspartate transaminase (237 U/L [reference range, 11–39 U/L]) and alanine transaminase (80 U/L [reference range, 11–35 U/L]) were elevated, while antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, serum immunoglobulin, and cryoglobulins were unremarkable. Punch biopsies of the left thigh were performed, and histopathology revealed small vessel thrombosis and ischemic changes consistent with PF (Figure 2). Vancomycin, clindamycin, cefepime injection, and piperacillin-tazobactam were administered intravenously for empiric broad-spectrum sepsis coverage. Within hours, the patient experienced refractory septic shock with disseminated intravascular coagulation and died from pulmonary embolism and subsequent cardiac arrest. Tissue and blood cultures grew V vulnificus.

Vibrio vulnificus is a gram-negative bacillus and a rare cause of primary septicemia following consumption of shellfish, especially oysters. Wounds exposed to saltwater or brackish water contaminated with the microorganism can produce soft-tissue infections. Individuals with chronic liver disease are at greater risk for V vulnificus infection.2 The clinical presentation of V vulnificus includes early cellulitislike patches, late purpura with hemorrhagic bullae, and rapidly progressing shock.3

Mortality rates from V vulnificus infection are high.4 Therefore, it is recommended to presumptively diagnose V vulnificus septicemia in any individual at risk for infection who presents with the characteristic history in the setting of hypotension, fever, or septic shock. It is crucial for providers to be aware that broad-spectrum antibiotics commonly used for sepsis are inadequate for the treatment of V vulnificus. Immediate treatment with tetracycline (minocycline or doxycycline) and a third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone injection) or in combination with ciprofloxacin has been proven effective.4,5

Vibrio vulnificus rarely is described in the literature as inducing PF. In one previously reported case, the patient was otherwise healthy and managed to recover following antibiotic therapy and wound debridement,6 whereas in another case the patient had undiagnosed liver cirrhosis and died from the infection.6,7 In the latter case, the patient presented to the emergency department in a coma. Our patient did not have the clinical signs of sepsis upon initial presentation to the emergency department. It is possible the infection rapidly progressed because of his underlying liver disease. Genotyping analysis of V vulnificus has shown that strains with low pathogenicity can cause primary septicemia in humans.7

Our case reinforces the need to quickly recognize V vulnificus as a rare underlying cause of PF and administer the appropriate treatment.

- Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:586-592.

- Tacket CO, Brenner F, Blake PA. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:558-561.

- Blake PA, Merson MH, Weaver RE et al. Disease caused by a marine Vibrio: clinical characteristics and epidemiology. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1-5.

- Liu JW, Lee IK, Tang HJ, et al. Prognostic factors and antibiotics in Vibrio vulnificus septicemia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2117-2123.

- Chen SC, Lee YT, Tsai SJ, et al. Antibiotic therapy for necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus: retrospective analysis of an 8 year period.J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:488-493.

- Choi HJ, Lee DK, Lee MW et al. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia presenting as purpura fulminans. J Dermatol. 2005;32:48-51.

- Hori M, Nakayama A, Kitagawa D et al. A case of Vibrio vulnificus infection complicated with fulminant purpura: gene and biotype analysis of the pathogen. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005096.

- Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:586-592.

- Tacket CO, Brenner F, Blake PA. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:558-561.

- Blake PA, Merson MH, Weaver RE et al. Disease caused by a marine Vibrio: clinical characteristics and epidemiology. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1-5.

- Liu JW, Lee IK, Tang HJ, et al. Prognostic factors and antibiotics in Vibrio vulnificus septicemia. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2117-2123.

- Chen SC, Lee YT, Tsai SJ, et al. Antibiotic therapy for necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus: retrospective analysis of an 8 year period.J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:488-493.

- Choi HJ, Lee DK, Lee MW et al. Vibrio vulnificus septicemia presenting as purpura fulminans. J Dermatol. 2005;32:48-51.

- Hori M, Nakayama A, Kitagawa D et al. A case of Vibrio vulnificus infection complicated with fulminant purpura: gene and biotype analysis of the pathogen. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005096.

Practice Points

- Purpura fulminans (PF) is a life-threatening condition characterized by intravascular coagulation and skin necrosis.

- Patients with underlying liver disease are at greater risk for PF secondary to Vibrio vulnificus infection.

- Given the high mortality rate, rapid identification of the etiologic agent and timely antibiotic treatment are necessary.

Second woman spontaneously clears HIV: ‘We think more are out there’

It sounds like a fairy tale steeped in HIV stigma: A woman wakes up one morning and, poof, the HIV she’s been living with for 8 years is gone. But for a 30-year-old Argentinian woman from the aptly named village of Esperanza, that’s close to the truth, according to an article published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The woman, the so-called Esperanza Patient, appears to be the second person whose immune system cleared the virus without the use of stem cell transplantation. The first was Loreen Willenberg, a California woman who, after living with HIV for 27 years, no longer had replicating HIV in her system. That case was reported last year.

“That’s the beauty of this name, right? Esperanza,” said Xu Yu, MD, principal investigator of the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard University, Boston, referring to the Spanish word for “hope.” “This makes us hopeful that a natural cure of HIV is actually possible.”

Two other people appear to have cleared HIV, but only after full replacement of the immune system via stem cell transplantation – the Berlin Patient, Timothy Ray Brown, and the London Patient. Another man, from Brazil, appeared to have an undetectable viral load after receiving intensified antiretroviral treatment plus supplemental vitamin B3.

The rarest of the rare

The Esperanza Patient is among a rare group of people living with HIV called elite controllers. These people’s immune systems can control HIV without antiretrovirals. Most elite controllers’ immune systems, however, can’t mount the immune attack necessary to eliminate all replicating HIV from their systems. Instead, their immune systems control the virus without affecting the reservoirs where HIV continues to make copies of itself and can spread.

The Esperanza Patient and Ms. Willenberg, however, appear to be the rarest of the rare. Their own immune systems seem not only to have stopped HIV replication outside of reservoirs but also to have stormed those reservoirs and killed all virus that might have continued to replicate.

The two women are connected in another way: At an HIV conference in 2019, Dr. Yu was presenting data on Ms. Willenberg’s case. At that conference, she met Natalia Laufer, MD, PhD, associate researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas en Retrovirs y SIDA at the University of Buenos Aires. Dr. Laufer had been studying the Esperanza Patient at the time and asked Dr. Yu whether she and her team at the Ragon Institute could help her sequence the patient’s HIV genome to see whether, indeed, the virus had been spontaneously cleared from the patient’s system.

So that’s what the pair did, in collaboration with several other researchers into cures for HIV. The Esperanza Patient first acquired HIV in 2013, but in the 8 years that followed, results of 10 conventional viral load tests indicated the virus was undetectable (that is, below the level of quantification for standard technology). During that time, the woman’s boyfriend, from whom she had acquired HIV, died of AIDS-defining illnesses. She subsequently married and had a baby. Both her partner and baby are HIV negative. She only received HIV treatment for 6 months while she was pregnant.

A fossil record of HIV

Yet, there was still HIV in the woman’s system. Dr. Laufer and Dr. Yu wanted to know whether that HIV was transmissible or whether it was a relic from when HIV was still replicating and was now defective and incapable of replicating. They performed extensive genome sequencing on nearly 1.2 billion cells that Dr. Laufer had taken from the patient’s blood in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, an additional 503 million cells that were from the placenta of the baby she gave birth to in 2020, and 150 million resting CD4 T cells. Proviral sequencing was undertaken of the full DNA of the HIV to detect whether the virus was still intact. The DNA was then analyzed by use of an algorithm and was tested for mutations. The investigators tested the patient’s CD4 cells to determine whether the cells still harbored any latent HIV.

In this way, they conducted a full viral workup using tests that are far more sensitive than the viral load tests the woman had undergone in the clinic. The investigators then assessed the patient’s immune system to see what the various cells of the immune system could tell them about how well her natural immune system could identify and kill HIV. They isolated the Esperanza Patient’s immune cells and subjected those cells to HIV in the lab to see whether the cells could detect and eliminate the virus.

And just to be safe, they checked to make sure there were no antiretroviral drugs in the patient’s system.

What they found was that without treatment, her CD4 count hovered around 1,000 cells – a sign of a functioning immune system. DNA sequences revealed large chunks of missing DNA, and one sequence had an immune-induced hypermutation. In total, seven proviruses were found, but none were capable of replicating. The CD4 cells they evaluated showed no evidence of latent HIV.

In other words, they had uncovered a fossil record.

“These HIV-1 DNA products clearly indicate that this person was infected with HIV-1 in the past and that active cycles of viral replication had occurred at one point,” Dr. Yu and colleagues write in their recent article.