User login

Atopic Dermatitis in Adolescents With Skin of Color

Data are limited on the management of atopic dermatitis (AD) in adolescents, particularly in patients with skin of color, making it important to identify factors that may improve AD management in this population. Comorbid conditions (eg, acne, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [PIH]), extracurricular activities (eg, athletics), and experimentation with cosmetics in adolescents, all of which can undermine treatment efficacy and medication adherence, make it particularly challenging to devise a therapeutic regimen in this patient population. We review the management of AD in black adolescents, with special consideration of concomitant treatment of acne vulgaris (AV) as well as lifestyle and social choices (Table).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Atopic dermatitis affects 13% to 25% of children and 2% to 10% of adults.1,2 Population‐based studies in the United States show a higher prevalence of AD in black children (19.3%) compared to European American (EA) children (16.1%).3,4

AD in Black Adolescents

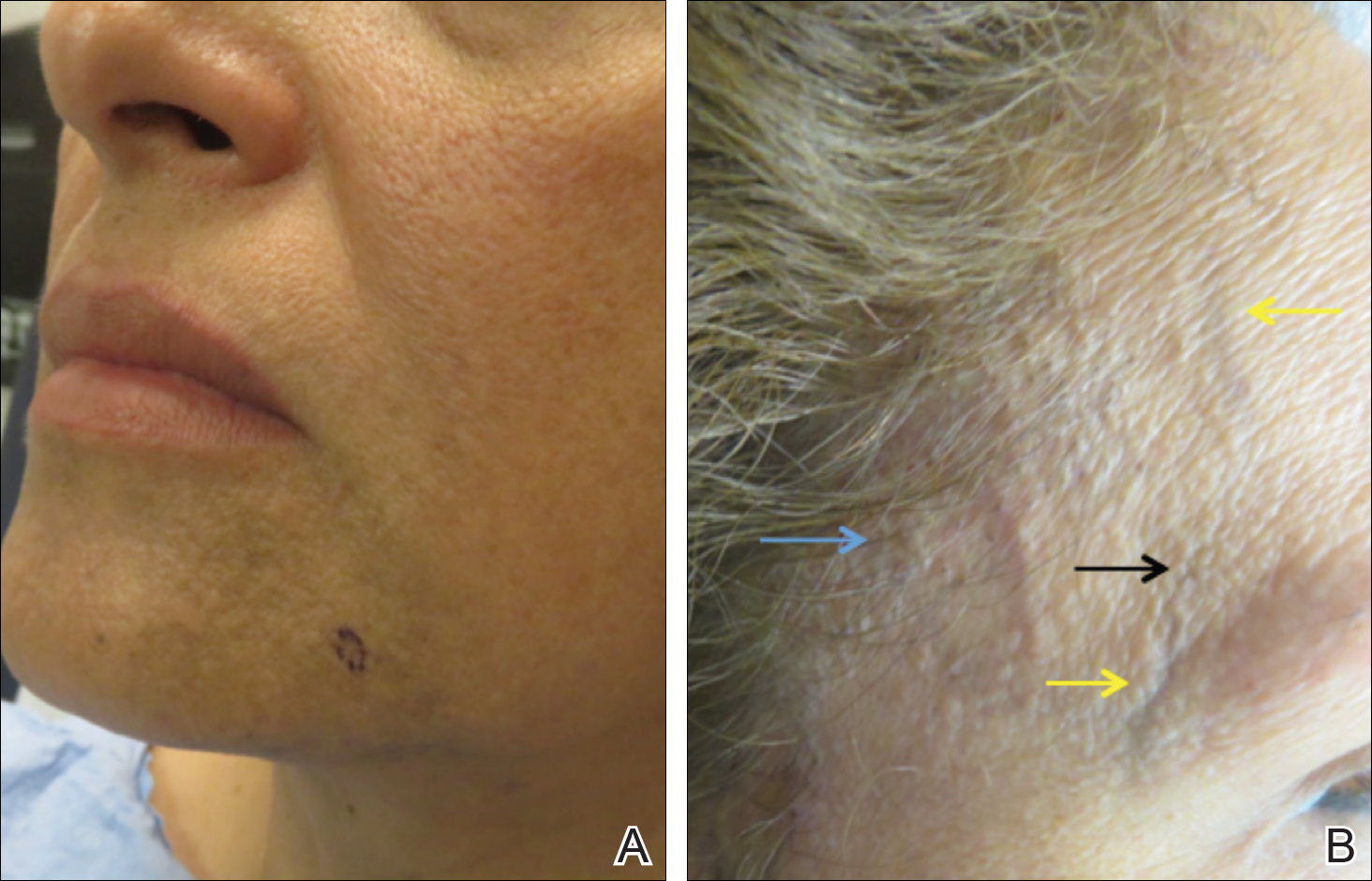

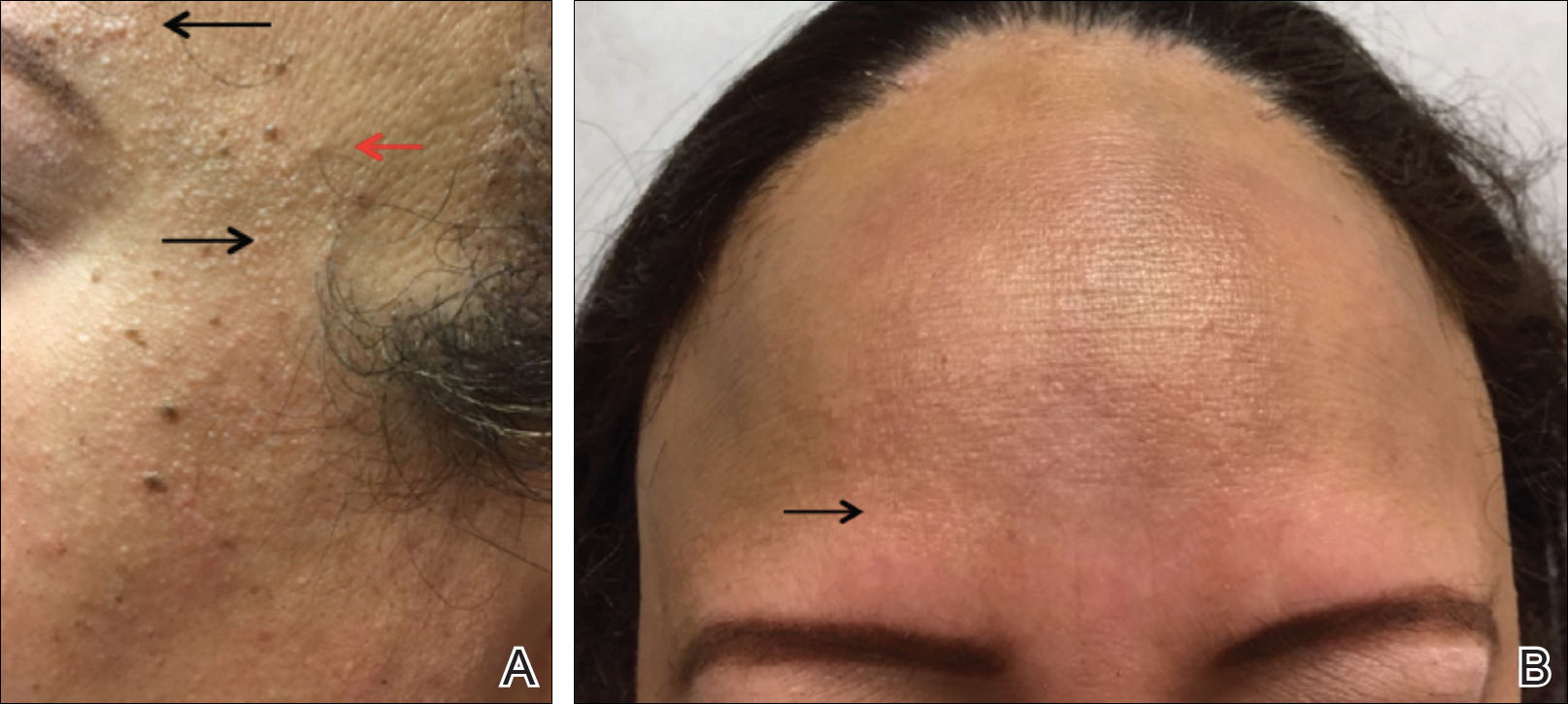

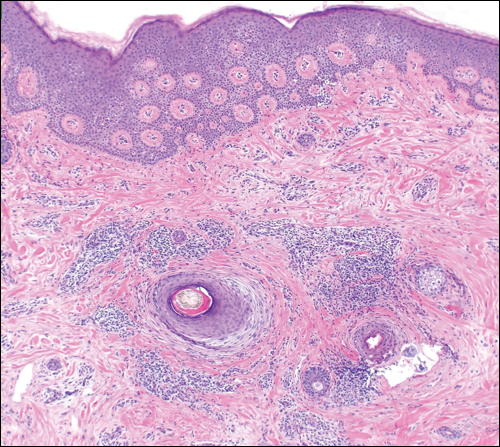

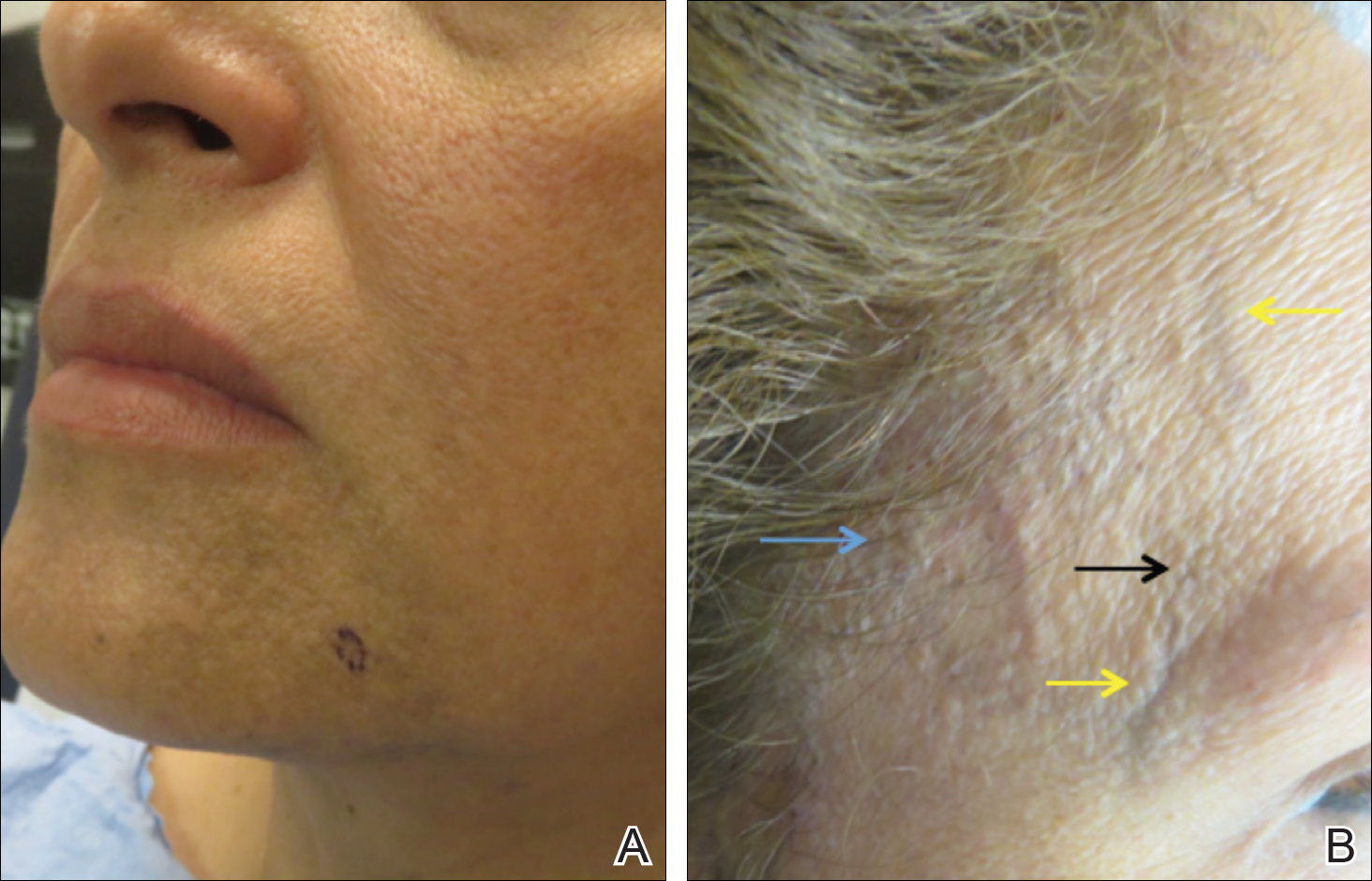

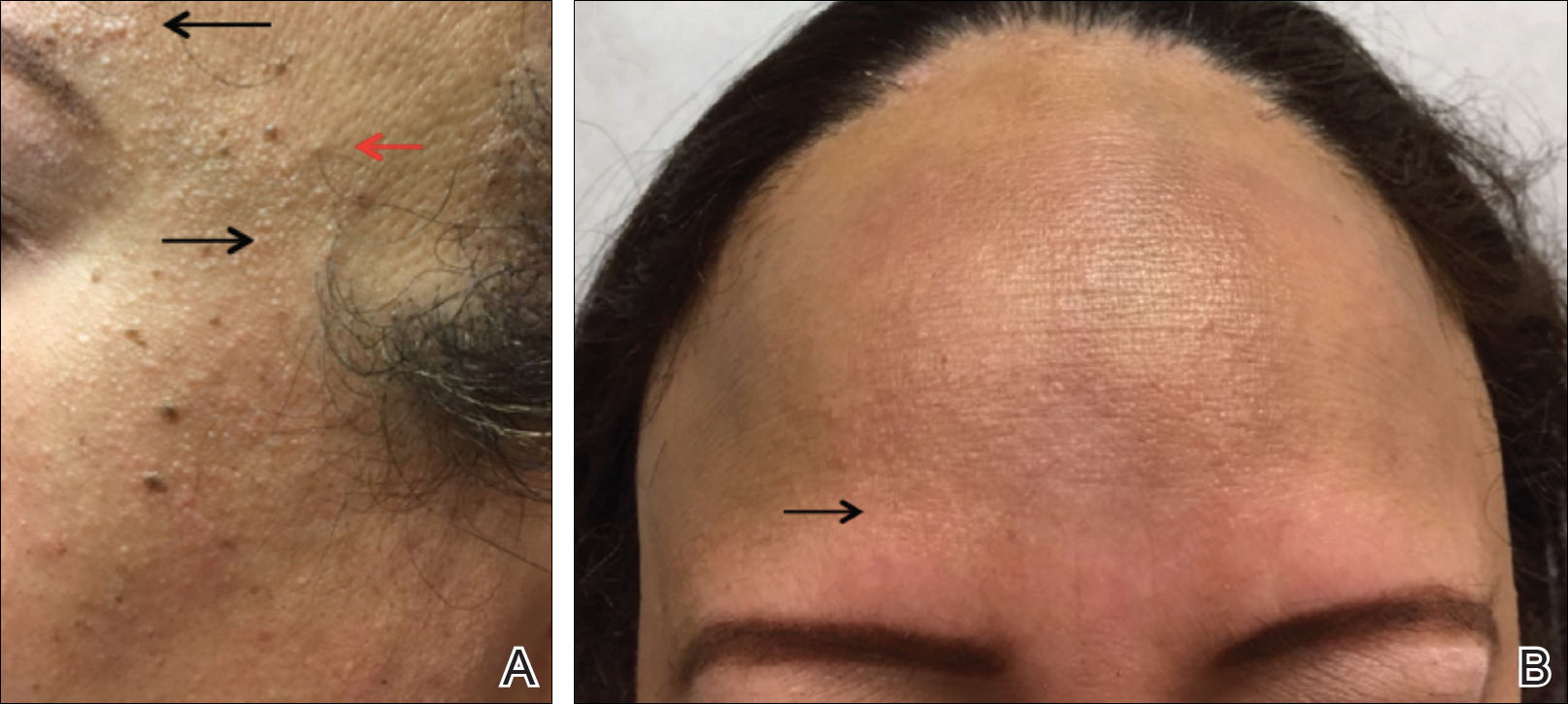

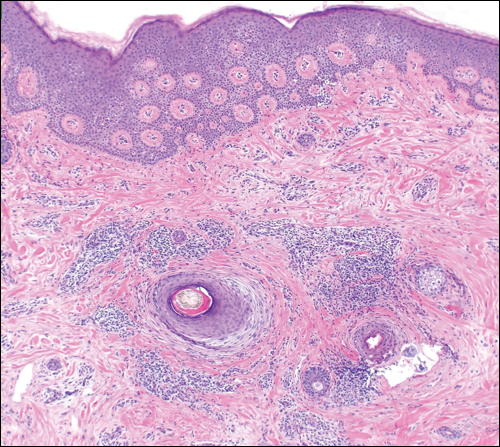

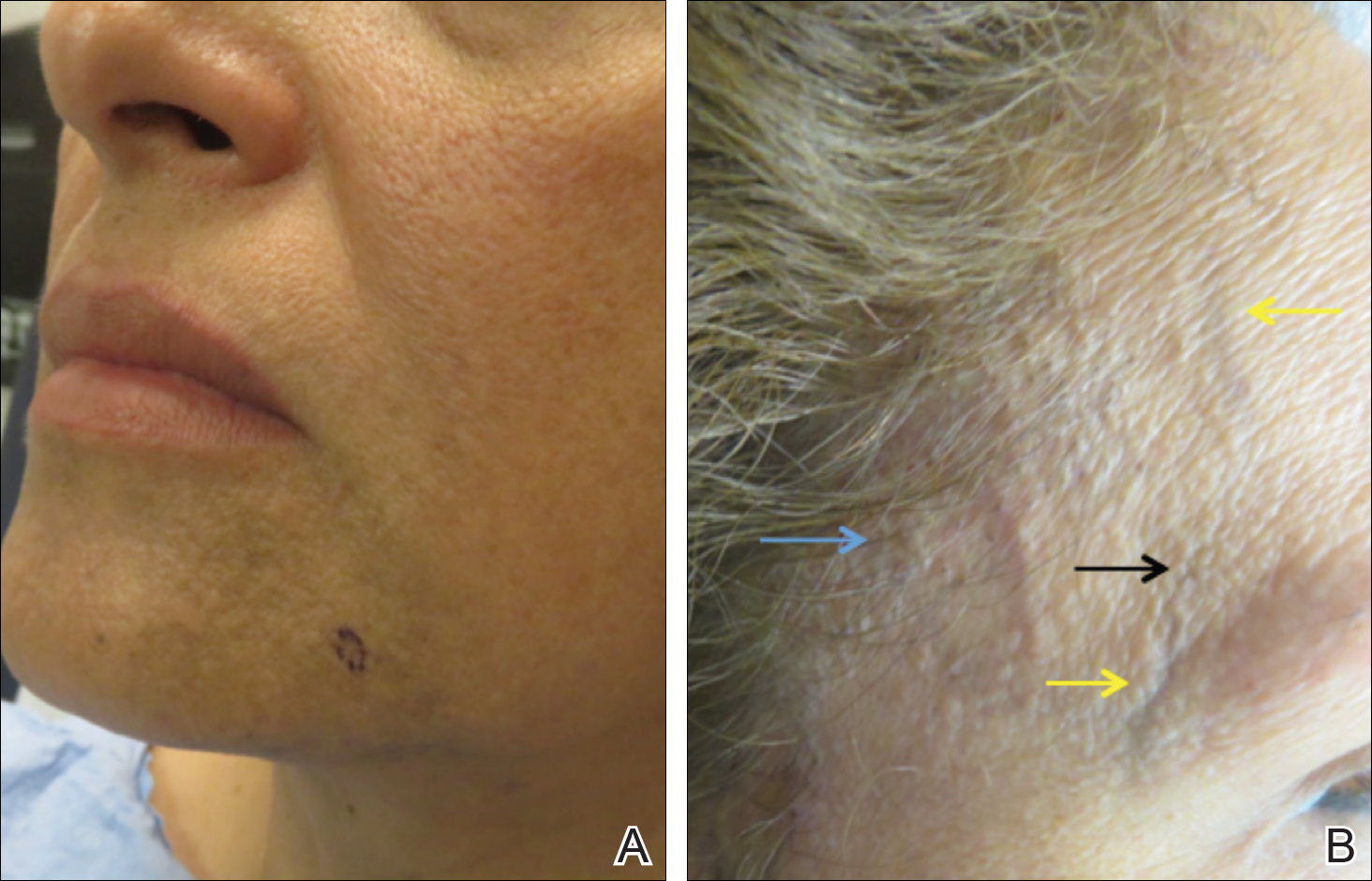

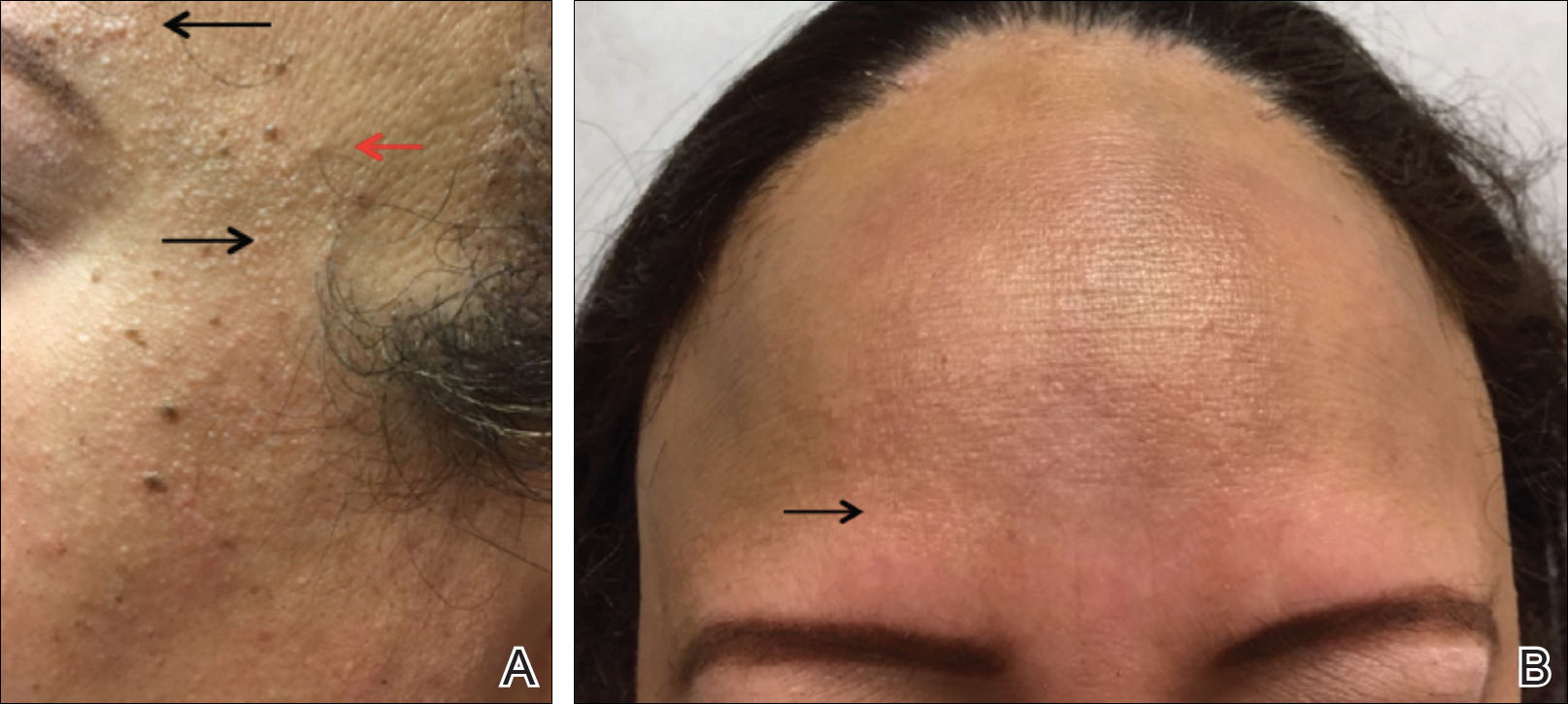

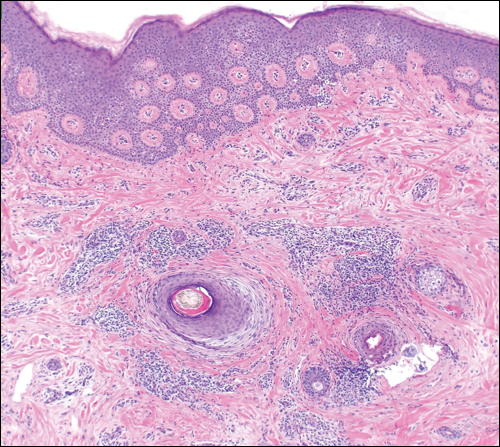

Atopic dermatitis is a common skin condition that is defined as a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory dermatosis with recurrent scaling, papules, and plaques (Figure) that usually develop during infancy and early childhood.3 Although AD severity improves for some patients in adolescence, it can be a lifelong issue affecting performance in academic and occupational settings.5 One US study of 8015 children found that there are racial and ethnic disparities in school absences among children (age range, 2–17 years) with AD, with children with skin of color being absent more often than white children.6 The same study noted that black children had a 1.5-fold higher chance of being absent 6 days over a 6-month school period compared to white children. It is postulated that AD has a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in children with skin of color, resulting in the increased number of school absences in this population.6

The origin of AD currently is thought to be complex and can involve skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors, microbiome effects, genetic predisposition, and immune dysregulation.1,4 Atopic dermatitis is a heterogeneous disease with variations in the prevalence, genetic background, and immune activation patterns across racial groups.4 It is now understood to be an immune-mediated disease with multiple inflammatory pathways, with type 2–associated inflammation being a primary pathway. Patients with AD have strong helper T cell (TH2) activation, and black patients with AD have higher IgE serum levels as well as absent TH17/TH1 activation.4

Atopic dermatitis currently is seen as a defect of the epidermal barrier, with variable clinical manifestations and expressivity.7 Filaggrin is an epidermal barrier protein, encoded by the FLG gene, and plays a major role in barrier function by regulating pH and promoting hydration of the skin.4 Loss of function of the FLG gene is the most well-studied genetic risk factor for developing AD, and this mutation is seen in patients with more severe and persistent AD in addition to patients with more skin infections and allergic sensitizations.3,4 However, in the skin of color population, FLG mutations are 6 times less common than in the EA population, despite the fact that AD is more prevalent in patients of African descent.4 Therefore, the role of the FLG loss-of-function mutation and AD is not as well defined in black patients, and some researchers have found no association.3 The FLG loss-of-function mutation seems to play a smaller role in black patients than in EA patients, and other genes may be involved in skin barrier dysfunction.3,4 In a small study of patients with mild AD compared to nonaffected patients, those with AD had lower total ceramide levels in the stratum corneum of affected sites than normal skin sites in healthy individuals.8

Particular disturbances in the gut microbiome have the possibility of impacting the development of AD.9 Additionally, the development of AD may be influenced by the skin microbiome, which can change depending on body site, with fungal organisms thought to make up a large proportion of the microbiome of patients with AD. In patients with AD, there is a lack of microbial diversity and an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus.9

Diagnosis

Clinicians diagnose AD based on clinical characteristics, and the lack of objective criteria can hinder diagnosis.1 Thus, diagnosing AD in children with dark skin can pose a particular challenge given the varied clinical presentation of AD across skin types. Severe cases of AD may not be diagnosed or treated adequately in deeply pigmented children because erythema, a defining characteristic of AD, may be hard to identify in darker skin types.10 Furthermore, clinical erythema scores among black children may be “strongly” underestimated using scoring systems such as Eczema Area and Severity Index and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis.4 It is estimated that the risk for severe AD may be 6 times higher in black children compared to white children.10 Additionally, patients with skin of color can present with more treatment-resistant AD.4

Treatment of AD

Current treatment is focused on restoring epidermal barrier function, often with topical agents, such as moisturizers containing different amounts of emollients, occlusives, and humectants; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and antimicrobials. Emollients such as glycol stearate, glyceryl stearate, and soy sterols function as lubricants, softening the skin. Occlusive agents include petrolatum, dimethicone, and mineral oil; they act by forming a layer to slow evaporation of water. Humectants including glycerol, lactic acid, and urea function by promoting water retention.11 For acute flares, mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are recommended. Also, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be used alone or in combination with topical steroids. Finally, bleach baths and topical mupirocin applied to the nares also have proved helpful in moderate to severe AD with secondary bacterial infections.11 Phototherapy can be used in adult and pediatric patients with acute and chronic AD if traditional treatments have failed.2

Systemic agents are indicated and recommended for the subset of adult and pediatric patients in whom optimized topical regimens and/or phototherapy do not adequately provide disease control or when QOL is substantially impacted. The systemic agents effective in the pediatric population include cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and possibly methotrexate.11 Dupilumab recently was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not well controlled with topical medications.

Patients with AD are predisposed to secondary bacterial and viral infections because of their dysfunctional skin barrier; these infections most commonly are caused by S aureus and herpes simplex virus, respectively.2 Systemic antibiotics are only recommended for patients with AD when there is clinical evidence of bacterial infection. In patients with evidence of eczema herpeticum, systemic antiviral agents should be used to treat the underlying herpes simplex virus infection.2 Atopic dermatitis typically has been studied in white patients; however, patients with skin of color have higher frequencies of treatment-resistant AD. Further research on treatment efficacy for AD in this patient population is needed, as data are limited.4

Treatment of AV in Patients With AD

Two of the most prevalent skin diseases affecting the pediatric population are AD and AV, and both can remarkably impact QOL.12 Acne is one of the most common reasons for adolescent patients to seek dermatologic care, including patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI).13 Thus, it is to be expected that many black adolescents with AD also will have AV. For mild to moderate acne in patients with skin of color, topical retinoids and benzoyl peroxide typically are first line.13 These medications can be problematic for patients with AD, as retinoids and many other acne treatments can cause dryness, which may exacerbate AD.

Moisturizers containing ceramide can be a helpful adjunctive therapy in treating acne,14 especially in patients with AD. Modifications to application of acne medications, such as using topical retinoids every other night or mixing them with moisturizers to minimize dryness, may be beneficial to these patients. Dapsone gel 7.5% used daily also may be an option for adolescents with AD and AV. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study demonstrated that dapsone is safe and effective for patients 12 years and older with moderate acne, and patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI rated local scaling, erythema, dryness, and stinging/burning as “none” in the study.15 Another potentially helpful topical agent in patients with AD and AV is sulfacetamide, as it is not likely to cause dryness of the skin. In a small study, sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% in an emollient foam vehicle showed no residual film or sulfur smell and resulted in acne reduction of 50%.16

Patients with skin of color often experience PIH in AD and acne or hypopigmentation from inflammatory dermatoses including AD.17,18 In addition to the dryness from AD and topical retinoid use, patients with skin of color may develop irritant contact dermatitis, thus leading to PIH.13 Dryness and irritant contact dermatitis also can be seen with the use of benzoyl peroxide in black patients. Because of these effects, gentle moisturizers are recommended, and both benzoyl peroxide and retinoids should be initiated at lower doses in patients with skin of color.13

For patients with severe nodulocystic acne, isotretinoin is the treatment of choice in patients with skin of color,13 but there is a dearth of clinical studies addressing complications seen in black adolescents on this treatment, especially with respect to those with AD. Of note, systemic antibiotics typically are initiated before isotretinoin; however, this strategy is falling out of favor due to concern for antibiotic resistance with long-term use.19

Impact of Athletics on AD in Black Adolescents

Because of the exacerbating effects of perspiration and heat causing itch and irritation in patients with AD, it is frequently advised that pediatric patients limit their participation in athletics because of the exacerbating effects of strenuous physical exercise on their disease.12 In one study, 429 pediatric patients or their parents/guardians completed QOL questionnaires; 89% of patients 15 years and younger with severe AD reported that their disease was impacted by athletics and outdoor activities, and 86% of these pediatric patients with severe AD responded that their social lives and leisure activities were impacted.20 Because adolescents often are involved in athletics or have mandatory physical education classes, AD may be isolating and may have a severe impact on self-esteem.

Aggressive treatment of AD with topical and systemic medications may be helpful in adolescents who may be reluctant to participate in sports because of teasing, bullying, or worsening of symptoms with heat or sweating.21 Now that dupilumab is available for adolescents, there is a chance that patients with severe and/or recalcitrant disease managed on this medication can achieve better control of their symptoms without the laboratory requirement of methotrexate and the difficulties of topical medication application, allowing them to engage in mandatory athletic classes as well as desired organized sports.

Use of Cosmetics for AD

Many adolescents experiment with cosmetics, and those with AD may use cosmetic products to cover hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions.18 In patients with active AD or increased sensitivity to allergens in cosmetic products, use of makeup can be a contributing factor for AD flares. Acne associated with cosmetics is especially important to consider in darker-skinned patients who may use makeup that is opaque and contains oil to conceal acne or PIH.

Allergens can be present in both cosmetics and pharmaceutical topical agents, and a Brazilian study found that approximately 89% of 813 prescription and nonprescription products (eg, topical drugs, sunscreens, moisturizers, soaps, cleansing lotions, shampoos, cosmeceuticals) contained allergens.22 Patients with AD have a higher prevalence of contact sensitization to fragrances, including balsam of Peru.23 Some AD treatments that contain fragrances have caused further skin issues in a few patients. In one case series, 3 pediatric patients developed allergic contact dermatitis to Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru) when using topical treatments for their AD, and their symptoms of scalp inflammation and alopecia resolved with discontinuation.23

In a Dutch study, sensitization to Fragrance Mix I and M pereirae as well as other ingredients (eg, lanolin alcohol, Amerchol™ L 101 [a lanolin product]) was notably more common in pediatric patients with AD than in patients without AD; however, no data on patients with skin of color were included in this study.24

Because of the increased risk of sensitization to fragrances and other ingredients in patients with AD as well as the high percentage of allergens in prescription and nonprescription products, it is important to discuss all personal care products that patients may be using, not just their cosmetic products. Also, patch testing may be helpful in determining true allergens in some patients. Patch testing is recommended for patients with treatment-resistant AD, and a recent study suggested it should be done prior to long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.25 Increased steroid phobia and a push toward alternative medicines are leading both patients with AD and guardians of children with AD to look for other forms of moisturization, such as olive oil, coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and shea butter, to decrease transepidermal water loss.26,27 An important factor in AD treatment efficacy is patient acceptability in using what is recommended.27 One study showed there was no difference in efficacy or acceptability in using a cream containing shea butter extract vs the ceramide-precursor product.27 Current data show olive oil may exacerbate dry skin and AD,26 and recommendation of any over-the-counter oils and butters in patients with AD should be made with great caution, as many of these products contain fragrances and other potential allergens.

Alternative Therapies for AD

Patients with AD often seek alternative or integrative treatment options, including dietary modifications and holistic remedies. Studies investigating the role of vitamins and supplements in treating AD are limited by sample size.28 However, there is some evidence that may support supplementation with vitamins D and E in addressing AD symptoms. The use of probiotics in treating AD is controversial, but there are studies suggesting that the use of probiotics may prove beneficial in preventing infantile AD.28 Additionally, findings from an ex vivo and in vitro study show that some conditions, including AD and acne, may benefit from the same probiotics, despite the differences in these two diseases. Both AD and acne have inflammatory and skin dysbiosis characteristics, which may be the common thread leading to both conditions potentially responding to treatment with probiotics.29

Preliminary evidence indicates that supplements containing fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid, sea buckthorn oil, and hemp seed oil may decrease the severity of AD.28 In a 20-week, randomized, single-blind, crossover study published in 2005, dietary hemp seed oil showed an improvement of clinical symptoms, including dry skin and itchiness, in patients with AD.30

In light of recent legalization in several states, patients may turn to use of cannabinoid products to manage AD. In a systematic review, cannabinoid use was reportedly a therapeutic option in the treatment of AD and AV; however, the data are based on preclinical work, and there are no randomized, placebo-controlled studies to support the use of cannabinoids.31 Furthermore, there is great concern that use of these products in adolescents is an even larger unknown.

Final Thoughts

Eighty percent of children diagnosed with AD experience symptom improvement before their early teens32; for those with AD during their preteen and teenage years, there can be psychological ramifications, as teenagers with AD report having fewer friends, are less socially involved, participate in fewer sports, and are absent from classes more often than their peers.5 In black patients with AD, school absences are even more common.6 Given the social and emotional impact of AD on patients with skin of color, it is imperative to treat the condition appropriately.33 There are areas of opportunity for further research on alternate dosing of existing treatments for AV in patients with AD, further recommendations for adolescent athletes with AD, and which cosmetic and alternative medicine products may be beneficial for this population to improve their QOL.

Providers should discuss medical management in a broader context considering patients’ extracurricular activities, treatment vehicle preferences, expectations, and personal care habits. It also is important to address the many possible factors that may influence treatment adherence early on, particularly in adolescents, as these could be barriers to treatment. This article highlights considerations for treating AD and comorbid conditions that may further complicate treatment in adolescent patients with skin of color. The information provided should serve as a guide in initial counseling and management of AD in adolescents with skin of color.

- Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12:83-93.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357.

- Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E. Racial differences in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:449-455.

- Vivar KL, Kruse L. The impact of pediatric skin disease on self-esteem. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:27-31.

- Wan J, Margolis DJ, Mitra N, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in atopic dermatitis–related school absences among US children [published online May 22, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0597.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Ishikawa J, Narita H, Kondo N, et al. Changes in the ceramide profile of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2511-2514.

- Chernikova D, Yuan I, Shaker M. Prevention of allergy with diverse and healthy microbiota: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31:418-425.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Nguyen CM, Koo J, Cordoro KM. Psychodermatologic effects of atopic dermatitis and acne: a review on self-esteem and identity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:129-135.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

- Lynde CW, Andriessen A, Barankin B, et al. Moisturizers and ceramide-containing moisturizers may offer concomitant therapy with benefits. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:18-26.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden FE, McMichael A, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of topical dapsone gel, 7.5% for treatment of acne vulgaris by Fitzpatrick skin phototype. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:160-167.

- Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-236.

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402.

- Heath CR. Managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2018;102:71-73.

- Nagler AR, Milam EC, Orlow SJ. The use of oral antibiotics before isotretinoin therapy in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:273-279.

- Paller AS, McAlister RO, Doyle JJ, et al. Perceptions of physicians and pediatric patients about atopic dermatitis, its impact, and its treatment. Clin Pediatr. 2002;41:323-332.

- Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:303-316.

- Rocha VB, Machado CJ, Bittencourt FV. Presence of allergens in the vehicles of Brazilian dermatological products. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:126-128.

- Admani S, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact alopecia: improvement of alopecia with discontinuation of fluocinolone oil in individuals allergic to balsam fragrance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:e57-e60.

- Uter W, Werfel T, White IR, et al. Contact allergy: a review of current problems from a clinical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:E1108.

- López-Jiménez EC, Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L. One-third of patients with therapy-resistant atopic dermatitis may benefit after patch testing [published online May 13, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15672.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15.

- Hon KL, Tsang YC, Pong NH, et al. Patient acceptability, efficacy, and skin biophysiology of a cream and cleanser containing lipid complex with shea butter extract versus a ceramide product for eczema. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:417-425.

- Reynolds KA, Juhasz MLW, Mesinkovska NA. The role of oral vitamins and supplements in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review [published online March 20, 2019]. Int J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ijd.14404.

- Mottin VHM, Suyenaga ES. An approach on the potential use of probiotics in the treatment of skin conditions: acne and atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1425-1432.

- Callaway J, Schwab U, Harvima I, et al. Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:87-94.

- Eagleston LRM, Kalani NK, Patel RR, et al. Cannabinoids in dermatology: a scoping review [published June 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24.

- Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, et al. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-687.e611.

- de María Díaz Granados L, Quijano MA, Ramírez PA, et al. Quality assessment of atopic dermatitis clinical practice guidelines in ≤ 18 years. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:29-37.

Data are limited on the management of atopic dermatitis (AD) in adolescents, particularly in patients with skin of color, making it important to identify factors that may improve AD management in this population. Comorbid conditions (eg, acne, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [PIH]), extracurricular activities (eg, athletics), and experimentation with cosmetics in adolescents, all of which can undermine treatment efficacy and medication adherence, make it particularly challenging to devise a therapeutic regimen in this patient population. We review the management of AD in black adolescents, with special consideration of concomitant treatment of acne vulgaris (AV) as well as lifestyle and social choices (Table).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Atopic dermatitis affects 13% to 25% of children and 2% to 10% of adults.1,2 Population‐based studies in the United States show a higher prevalence of AD in black children (19.3%) compared to European American (EA) children (16.1%).3,4

AD in Black Adolescents

Atopic dermatitis is a common skin condition that is defined as a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory dermatosis with recurrent scaling, papules, and plaques (Figure) that usually develop during infancy and early childhood.3 Although AD severity improves for some patients in adolescence, it can be a lifelong issue affecting performance in academic and occupational settings.5 One US study of 8015 children found that there are racial and ethnic disparities in school absences among children (age range, 2–17 years) with AD, with children with skin of color being absent more often than white children.6 The same study noted that black children had a 1.5-fold higher chance of being absent 6 days over a 6-month school period compared to white children. It is postulated that AD has a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in children with skin of color, resulting in the increased number of school absences in this population.6

The origin of AD currently is thought to be complex and can involve skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors, microbiome effects, genetic predisposition, and immune dysregulation.1,4 Atopic dermatitis is a heterogeneous disease with variations in the prevalence, genetic background, and immune activation patterns across racial groups.4 It is now understood to be an immune-mediated disease with multiple inflammatory pathways, with type 2–associated inflammation being a primary pathway. Patients with AD have strong helper T cell (TH2) activation, and black patients with AD have higher IgE serum levels as well as absent TH17/TH1 activation.4

Atopic dermatitis currently is seen as a defect of the epidermal barrier, with variable clinical manifestations and expressivity.7 Filaggrin is an epidermal barrier protein, encoded by the FLG gene, and plays a major role in barrier function by regulating pH and promoting hydration of the skin.4 Loss of function of the FLG gene is the most well-studied genetic risk factor for developing AD, and this mutation is seen in patients with more severe and persistent AD in addition to patients with more skin infections and allergic sensitizations.3,4 However, in the skin of color population, FLG mutations are 6 times less common than in the EA population, despite the fact that AD is more prevalent in patients of African descent.4 Therefore, the role of the FLG loss-of-function mutation and AD is not as well defined in black patients, and some researchers have found no association.3 The FLG loss-of-function mutation seems to play a smaller role in black patients than in EA patients, and other genes may be involved in skin barrier dysfunction.3,4 In a small study of patients with mild AD compared to nonaffected patients, those with AD had lower total ceramide levels in the stratum corneum of affected sites than normal skin sites in healthy individuals.8

Particular disturbances in the gut microbiome have the possibility of impacting the development of AD.9 Additionally, the development of AD may be influenced by the skin microbiome, which can change depending on body site, with fungal organisms thought to make up a large proportion of the microbiome of patients with AD. In patients with AD, there is a lack of microbial diversity and an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus.9

Diagnosis

Clinicians diagnose AD based on clinical characteristics, and the lack of objective criteria can hinder diagnosis.1 Thus, diagnosing AD in children with dark skin can pose a particular challenge given the varied clinical presentation of AD across skin types. Severe cases of AD may not be diagnosed or treated adequately in deeply pigmented children because erythema, a defining characteristic of AD, may be hard to identify in darker skin types.10 Furthermore, clinical erythema scores among black children may be “strongly” underestimated using scoring systems such as Eczema Area and Severity Index and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis.4 It is estimated that the risk for severe AD may be 6 times higher in black children compared to white children.10 Additionally, patients with skin of color can present with more treatment-resistant AD.4

Treatment of AD

Current treatment is focused on restoring epidermal barrier function, often with topical agents, such as moisturizers containing different amounts of emollients, occlusives, and humectants; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and antimicrobials. Emollients such as glycol stearate, glyceryl stearate, and soy sterols function as lubricants, softening the skin. Occlusive agents include petrolatum, dimethicone, and mineral oil; they act by forming a layer to slow evaporation of water. Humectants including glycerol, lactic acid, and urea function by promoting water retention.11 For acute flares, mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are recommended. Also, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be used alone or in combination with topical steroids. Finally, bleach baths and topical mupirocin applied to the nares also have proved helpful in moderate to severe AD with secondary bacterial infections.11 Phototherapy can be used in adult and pediatric patients with acute and chronic AD if traditional treatments have failed.2

Systemic agents are indicated and recommended for the subset of adult and pediatric patients in whom optimized topical regimens and/or phototherapy do not adequately provide disease control or when QOL is substantially impacted. The systemic agents effective in the pediatric population include cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and possibly methotrexate.11 Dupilumab recently was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not well controlled with topical medications.

Patients with AD are predisposed to secondary bacterial and viral infections because of their dysfunctional skin barrier; these infections most commonly are caused by S aureus and herpes simplex virus, respectively.2 Systemic antibiotics are only recommended for patients with AD when there is clinical evidence of bacterial infection. In patients with evidence of eczema herpeticum, systemic antiviral agents should be used to treat the underlying herpes simplex virus infection.2 Atopic dermatitis typically has been studied in white patients; however, patients with skin of color have higher frequencies of treatment-resistant AD. Further research on treatment efficacy for AD in this patient population is needed, as data are limited.4

Treatment of AV in Patients With AD

Two of the most prevalent skin diseases affecting the pediatric population are AD and AV, and both can remarkably impact QOL.12 Acne is one of the most common reasons for adolescent patients to seek dermatologic care, including patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI).13 Thus, it is to be expected that many black adolescents with AD also will have AV. For mild to moderate acne in patients with skin of color, topical retinoids and benzoyl peroxide typically are first line.13 These medications can be problematic for patients with AD, as retinoids and many other acne treatments can cause dryness, which may exacerbate AD.

Moisturizers containing ceramide can be a helpful adjunctive therapy in treating acne,14 especially in patients with AD. Modifications to application of acne medications, such as using topical retinoids every other night or mixing them with moisturizers to minimize dryness, may be beneficial to these patients. Dapsone gel 7.5% used daily also may be an option for adolescents with AD and AV. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study demonstrated that dapsone is safe and effective for patients 12 years and older with moderate acne, and patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI rated local scaling, erythema, dryness, and stinging/burning as “none” in the study.15 Another potentially helpful topical agent in patients with AD and AV is sulfacetamide, as it is not likely to cause dryness of the skin. In a small study, sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% in an emollient foam vehicle showed no residual film or sulfur smell and resulted in acne reduction of 50%.16

Patients with skin of color often experience PIH in AD and acne or hypopigmentation from inflammatory dermatoses including AD.17,18 In addition to the dryness from AD and topical retinoid use, patients with skin of color may develop irritant contact dermatitis, thus leading to PIH.13 Dryness and irritant contact dermatitis also can be seen with the use of benzoyl peroxide in black patients. Because of these effects, gentle moisturizers are recommended, and both benzoyl peroxide and retinoids should be initiated at lower doses in patients with skin of color.13

For patients with severe nodulocystic acne, isotretinoin is the treatment of choice in patients with skin of color,13 but there is a dearth of clinical studies addressing complications seen in black adolescents on this treatment, especially with respect to those with AD. Of note, systemic antibiotics typically are initiated before isotretinoin; however, this strategy is falling out of favor due to concern for antibiotic resistance with long-term use.19

Impact of Athletics on AD in Black Adolescents

Because of the exacerbating effects of perspiration and heat causing itch and irritation in patients with AD, it is frequently advised that pediatric patients limit their participation in athletics because of the exacerbating effects of strenuous physical exercise on their disease.12 In one study, 429 pediatric patients or their parents/guardians completed QOL questionnaires; 89% of patients 15 years and younger with severe AD reported that their disease was impacted by athletics and outdoor activities, and 86% of these pediatric patients with severe AD responded that their social lives and leisure activities were impacted.20 Because adolescents often are involved in athletics or have mandatory physical education classes, AD may be isolating and may have a severe impact on self-esteem.

Aggressive treatment of AD with topical and systemic medications may be helpful in adolescents who may be reluctant to participate in sports because of teasing, bullying, or worsening of symptoms with heat or sweating.21 Now that dupilumab is available for adolescents, there is a chance that patients with severe and/or recalcitrant disease managed on this medication can achieve better control of their symptoms without the laboratory requirement of methotrexate and the difficulties of topical medication application, allowing them to engage in mandatory athletic classes as well as desired organized sports.

Use of Cosmetics for AD

Many adolescents experiment with cosmetics, and those with AD may use cosmetic products to cover hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions.18 In patients with active AD or increased sensitivity to allergens in cosmetic products, use of makeup can be a contributing factor for AD flares. Acne associated with cosmetics is especially important to consider in darker-skinned patients who may use makeup that is opaque and contains oil to conceal acne or PIH.

Allergens can be present in both cosmetics and pharmaceutical topical agents, and a Brazilian study found that approximately 89% of 813 prescription and nonprescription products (eg, topical drugs, sunscreens, moisturizers, soaps, cleansing lotions, shampoos, cosmeceuticals) contained allergens.22 Patients with AD have a higher prevalence of contact sensitization to fragrances, including balsam of Peru.23 Some AD treatments that contain fragrances have caused further skin issues in a few patients. In one case series, 3 pediatric patients developed allergic contact dermatitis to Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru) when using topical treatments for their AD, and their symptoms of scalp inflammation and alopecia resolved with discontinuation.23

In a Dutch study, sensitization to Fragrance Mix I and M pereirae as well as other ingredients (eg, lanolin alcohol, Amerchol™ L 101 [a lanolin product]) was notably more common in pediatric patients with AD than in patients without AD; however, no data on patients with skin of color were included in this study.24

Because of the increased risk of sensitization to fragrances and other ingredients in patients with AD as well as the high percentage of allergens in prescription and nonprescription products, it is important to discuss all personal care products that patients may be using, not just their cosmetic products. Also, patch testing may be helpful in determining true allergens in some patients. Patch testing is recommended for patients with treatment-resistant AD, and a recent study suggested it should be done prior to long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.25 Increased steroid phobia and a push toward alternative medicines are leading both patients with AD and guardians of children with AD to look for other forms of moisturization, such as olive oil, coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and shea butter, to decrease transepidermal water loss.26,27 An important factor in AD treatment efficacy is patient acceptability in using what is recommended.27 One study showed there was no difference in efficacy or acceptability in using a cream containing shea butter extract vs the ceramide-precursor product.27 Current data show olive oil may exacerbate dry skin and AD,26 and recommendation of any over-the-counter oils and butters in patients with AD should be made with great caution, as many of these products contain fragrances and other potential allergens.

Alternative Therapies for AD

Patients with AD often seek alternative or integrative treatment options, including dietary modifications and holistic remedies. Studies investigating the role of vitamins and supplements in treating AD are limited by sample size.28 However, there is some evidence that may support supplementation with vitamins D and E in addressing AD symptoms. The use of probiotics in treating AD is controversial, but there are studies suggesting that the use of probiotics may prove beneficial in preventing infantile AD.28 Additionally, findings from an ex vivo and in vitro study show that some conditions, including AD and acne, may benefit from the same probiotics, despite the differences in these two diseases. Both AD and acne have inflammatory and skin dysbiosis characteristics, which may be the common thread leading to both conditions potentially responding to treatment with probiotics.29

Preliminary evidence indicates that supplements containing fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid, sea buckthorn oil, and hemp seed oil may decrease the severity of AD.28 In a 20-week, randomized, single-blind, crossover study published in 2005, dietary hemp seed oil showed an improvement of clinical symptoms, including dry skin and itchiness, in patients with AD.30

In light of recent legalization in several states, patients may turn to use of cannabinoid products to manage AD. In a systematic review, cannabinoid use was reportedly a therapeutic option in the treatment of AD and AV; however, the data are based on preclinical work, and there are no randomized, placebo-controlled studies to support the use of cannabinoids.31 Furthermore, there is great concern that use of these products in adolescents is an even larger unknown.

Final Thoughts

Eighty percent of children diagnosed with AD experience symptom improvement before their early teens32; for those with AD during their preteen and teenage years, there can be psychological ramifications, as teenagers with AD report having fewer friends, are less socially involved, participate in fewer sports, and are absent from classes more often than their peers.5 In black patients with AD, school absences are even more common.6 Given the social and emotional impact of AD on patients with skin of color, it is imperative to treat the condition appropriately.33 There are areas of opportunity for further research on alternate dosing of existing treatments for AV in patients with AD, further recommendations for adolescent athletes with AD, and which cosmetic and alternative medicine products may be beneficial for this population to improve their QOL.

Providers should discuss medical management in a broader context considering patients’ extracurricular activities, treatment vehicle preferences, expectations, and personal care habits. It also is important to address the many possible factors that may influence treatment adherence early on, particularly in adolescents, as these could be barriers to treatment. This article highlights considerations for treating AD and comorbid conditions that may further complicate treatment in adolescent patients with skin of color. The information provided should serve as a guide in initial counseling and management of AD in adolescents with skin of color.

Data are limited on the management of atopic dermatitis (AD) in adolescents, particularly in patients with skin of color, making it important to identify factors that may improve AD management in this population. Comorbid conditions (eg, acne, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [PIH]), extracurricular activities (eg, athletics), and experimentation with cosmetics in adolescents, all of which can undermine treatment efficacy and medication adherence, make it particularly challenging to devise a therapeutic regimen in this patient population. We review the management of AD in black adolescents, with special consideration of concomitant treatment of acne vulgaris (AV) as well as lifestyle and social choices (Table).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Atopic dermatitis affects 13% to 25% of children and 2% to 10% of adults.1,2 Population‐based studies in the United States show a higher prevalence of AD in black children (19.3%) compared to European American (EA) children (16.1%).3,4

AD in Black Adolescents

Atopic dermatitis is a common skin condition that is defined as a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory dermatosis with recurrent scaling, papules, and plaques (Figure) that usually develop during infancy and early childhood.3 Although AD severity improves for some patients in adolescence, it can be a lifelong issue affecting performance in academic and occupational settings.5 One US study of 8015 children found that there are racial and ethnic disparities in school absences among children (age range, 2–17 years) with AD, with children with skin of color being absent more often than white children.6 The same study noted that black children had a 1.5-fold higher chance of being absent 6 days over a 6-month school period compared to white children. It is postulated that AD has a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in children with skin of color, resulting in the increased number of school absences in this population.6

The origin of AD currently is thought to be complex and can involve skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors, microbiome effects, genetic predisposition, and immune dysregulation.1,4 Atopic dermatitis is a heterogeneous disease with variations in the prevalence, genetic background, and immune activation patterns across racial groups.4 It is now understood to be an immune-mediated disease with multiple inflammatory pathways, with type 2–associated inflammation being a primary pathway. Patients with AD have strong helper T cell (TH2) activation, and black patients with AD have higher IgE serum levels as well as absent TH17/TH1 activation.4

Atopic dermatitis currently is seen as a defect of the epidermal barrier, with variable clinical manifestations and expressivity.7 Filaggrin is an epidermal barrier protein, encoded by the FLG gene, and plays a major role in barrier function by regulating pH and promoting hydration of the skin.4 Loss of function of the FLG gene is the most well-studied genetic risk factor for developing AD, and this mutation is seen in patients with more severe and persistent AD in addition to patients with more skin infections and allergic sensitizations.3,4 However, in the skin of color population, FLG mutations are 6 times less common than in the EA population, despite the fact that AD is more prevalent in patients of African descent.4 Therefore, the role of the FLG loss-of-function mutation and AD is not as well defined in black patients, and some researchers have found no association.3 The FLG loss-of-function mutation seems to play a smaller role in black patients than in EA patients, and other genes may be involved in skin barrier dysfunction.3,4 In a small study of patients with mild AD compared to nonaffected patients, those with AD had lower total ceramide levels in the stratum corneum of affected sites than normal skin sites in healthy individuals.8

Particular disturbances in the gut microbiome have the possibility of impacting the development of AD.9 Additionally, the development of AD may be influenced by the skin microbiome, which can change depending on body site, with fungal organisms thought to make up a large proportion of the microbiome of patients with AD. In patients with AD, there is a lack of microbial diversity and an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus.9

Diagnosis

Clinicians diagnose AD based on clinical characteristics, and the lack of objective criteria can hinder diagnosis.1 Thus, diagnosing AD in children with dark skin can pose a particular challenge given the varied clinical presentation of AD across skin types. Severe cases of AD may not be diagnosed or treated adequately in deeply pigmented children because erythema, a defining characteristic of AD, may be hard to identify in darker skin types.10 Furthermore, clinical erythema scores among black children may be “strongly” underestimated using scoring systems such as Eczema Area and Severity Index and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis.4 It is estimated that the risk for severe AD may be 6 times higher in black children compared to white children.10 Additionally, patients with skin of color can present with more treatment-resistant AD.4

Treatment of AD

Current treatment is focused on restoring epidermal barrier function, often with topical agents, such as moisturizers containing different amounts of emollients, occlusives, and humectants; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and antimicrobials. Emollients such as glycol stearate, glyceryl stearate, and soy sterols function as lubricants, softening the skin. Occlusive agents include petrolatum, dimethicone, and mineral oil; they act by forming a layer to slow evaporation of water. Humectants including glycerol, lactic acid, and urea function by promoting water retention.11 For acute flares, mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are recommended. Also, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus may be used alone or in combination with topical steroids. Finally, bleach baths and topical mupirocin applied to the nares also have proved helpful in moderate to severe AD with secondary bacterial infections.11 Phototherapy can be used in adult and pediatric patients with acute and chronic AD if traditional treatments have failed.2

Systemic agents are indicated and recommended for the subset of adult and pediatric patients in whom optimized topical regimens and/or phototherapy do not adequately provide disease control or when QOL is substantially impacted. The systemic agents effective in the pediatric population include cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and possibly methotrexate.11 Dupilumab recently was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for patients 12 years and older with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not well controlled with topical medications.

Patients with AD are predisposed to secondary bacterial and viral infections because of their dysfunctional skin barrier; these infections most commonly are caused by S aureus and herpes simplex virus, respectively.2 Systemic antibiotics are only recommended for patients with AD when there is clinical evidence of bacterial infection. In patients with evidence of eczema herpeticum, systemic antiviral agents should be used to treat the underlying herpes simplex virus infection.2 Atopic dermatitis typically has been studied in white patients; however, patients with skin of color have higher frequencies of treatment-resistant AD. Further research on treatment efficacy for AD in this patient population is needed, as data are limited.4

Treatment of AV in Patients With AD

Two of the most prevalent skin diseases affecting the pediatric population are AD and AV, and both can remarkably impact QOL.12 Acne is one of the most common reasons for adolescent patients to seek dermatologic care, including patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI).13 Thus, it is to be expected that many black adolescents with AD also will have AV. For mild to moderate acne in patients with skin of color, topical retinoids and benzoyl peroxide typically are first line.13 These medications can be problematic for patients with AD, as retinoids and many other acne treatments can cause dryness, which may exacerbate AD.

Moisturizers containing ceramide can be a helpful adjunctive therapy in treating acne,14 especially in patients with AD. Modifications to application of acne medications, such as using topical retinoids every other night or mixing them with moisturizers to minimize dryness, may be beneficial to these patients. Dapsone gel 7.5% used daily also may be an option for adolescents with AD and AV. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study demonstrated that dapsone is safe and effective for patients 12 years and older with moderate acne, and patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI rated local scaling, erythema, dryness, and stinging/burning as “none” in the study.15 Another potentially helpful topical agent in patients with AD and AV is sulfacetamide, as it is not likely to cause dryness of the skin. In a small study, sodium sulfacetamide 10% and sulfur 5% in an emollient foam vehicle showed no residual film or sulfur smell and resulted in acne reduction of 50%.16

Patients with skin of color often experience PIH in AD and acne or hypopigmentation from inflammatory dermatoses including AD.17,18 In addition to the dryness from AD and topical retinoid use, patients with skin of color may develop irritant contact dermatitis, thus leading to PIH.13 Dryness and irritant contact dermatitis also can be seen with the use of benzoyl peroxide in black patients. Because of these effects, gentle moisturizers are recommended, and both benzoyl peroxide and retinoids should be initiated at lower doses in patients with skin of color.13

For patients with severe nodulocystic acne, isotretinoin is the treatment of choice in patients with skin of color,13 but there is a dearth of clinical studies addressing complications seen in black adolescents on this treatment, especially with respect to those with AD. Of note, systemic antibiotics typically are initiated before isotretinoin; however, this strategy is falling out of favor due to concern for antibiotic resistance with long-term use.19

Impact of Athletics on AD in Black Adolescents

Because of the exacerbating effects of perspiration and heat causing itch and irritation in patients with AD, it is frequently advised that pediatric patients limit their participation in athletics because of the exacerbating effects of strenuous physical exercise on their disease.12 In one study, 429 pediatric patients or their parents/guardians completed QOL questionnaires; 89% of patients 15 years and younger with severe AD reported that their disease was impacted by athletics and outdoor activities, and 86% of these pediatric patients with severe AD responded that their social lives and leisure activities were impacted.20 Because adolescents often are involved in athletics or have mandatory physical education classes, AD may be isolating and may have a severe impact on self-esteem.

Aggressive treatment of AD with topical and systemic medications may be helpful in adolescents who may be reluctant to participate in sports because of teasing, bullying, or worsening of symptoms with heat or sweating.21 Now that dupilumab is available for adolescents, there is a chance that patients with severe and/or recalcitrant disease managed on this medication can achieve better control of their symptoms without the laboratory requirement of methotrexate and the difficulties of topical medication application, allowing them to engage in mandatory athletic classes as well as desired organized sports.

Use of Cosmetics for AD

Many adolescents experiment with cosmetics, and those with AD may use cosmetic products to cover hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions.18 In patients with active AD or increased sensitivity to allergens in cosmetic products, use of makeup can be a contributing factor for AD flares. Acne associated with cosmetics is especially important to consider in darker-skinned patients who may use makeup that is opaque and contains oil to conceal acne or PIH.

Allergens can be present in both cosmetics and pharmaceutical topical agents, and a Brazilian study found that approximately 89% of 813 prescription and nonprescription products (eg, topical drugs, sunscreens, moisturizers, soaps, cleansing lotions, shampoos, cosmeceuticals) contained allergens.22 Patients with AD have a higher prevalence of contact sensitization to fragrances, including balsam of Peru.23 Some AD treatments that contain fragrances have caused further skin issues in a few patients. In one case series, 3 pediatric patients developed allergic contact dermatitis to Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru) when using topical treatments for their AD, and their symptoms of scalp inflammation and alopecia resolved with discontinuation.23

In a Dutch study, sensitization to Fragrance Mix I and M pereirae as well as other ingredients (eg, lanolin alcohol, Amerchol™ L 101 [a lanolin product]) was notably more common in pediatric patients with AD than in patients without AD; however, no data on patients with skin of color were included in this study.24

Because of the increased risk of sensitization to fragrances and other ingredients in patients with AD as well as the high percentage of allergens in prescription and nonprescription products, it is important to discuss all personal care products that patients may be using, not just their cosmetic products. Also, patch testing may be helpful in determining true allergens in some patients. Patch testing is recommended for patients with treatment-resistant AD, and a recent study suggested it should be done prior to long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.25 Increased steroid phobia and a push toward alternative medicines are leading both patients with AD and guardians of children with AD to look for other forms of moisturization, such as olive oil, coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and shea butter, to decrease transepidermal water loss.26,27 An important factor in AD treatment efficacy is patient acceptability in using what is recommended.27 One study showed there was no difference in efficacy or acceptability in using a cream containing shea butter extract vs the ceramide-precursor product.27 Current data show olive oil may exacerbate dry skin and AD,26 and recommendation of any over-the-counter oils and butters in patients with AD should be made with great caution, as many of these products contain fragrances and other potential allergens.

Alternative Therapies for AD

Patients with AD often seek alternative or integrative treatment options, including dietary modifications and holistic remedies. Studies investigating the role of vitamins and supplements in treating AD are limited by sample size.28 However, there is some evidence that may support supplementation with vitamins D and E in addressing AD symptoms. The use of probiotics in treating AD is controversial, but there are studies suggesting that the use of probiotics may prove beneficial in preventing infantile AD.28 Additionally, findings from an ex vivo and in vitro study show that some conditions, including AD and acne, may benefit from the same probiotics, despite the differences in these two diseases. Both AD and acne have inflammatory and skin dysbiosis characteristics, which may be the common thread leading to both conditions potentially responding to treatment with probiotics.29

Preliminary evidence indicates that supplements containing fatty acids such as docosahexaenoic acid, sea buckthorn oil, and hemp seed oil may decrease the severity of AD.28 In a 20-week, randomized, single-blind, crossover study published in 2005, dietary hemp seed oil showed an improvement of clinical symptoms, including dry skin and itchiness, in patients with AD.30

In light of recent legalization in several states, patients may turn to use of cannabinoid products to manage AD. In a systematic review, cannabinoid use was reportedly a therapeutic option in the treatment of AD and AV; however, the data are based on preclinical work, and there are no randomized, placebo-controlled studies to support the use of cannabinoids.31 Furthermore, there is great concern that use of these products in adolescents is an even larger unknown.

Final Thoughts

Eighty percent of children diagnosed with AD experience symptom improvement before their early teens32; for those with AD during their preteen and teenage years, there can be psychological ramifications, as teenagers with AD report having fewer friends, are less socially involved, participate in fewer sports, and are absent from classes more often than their peers.5 In black patients with AD, school absences are even more common.6 Given the social and emotional impact of AD on patients with skin of color, it is imperative to treat the condition appropriately.33 There are areas of opportunity for further research on alternate dosing of existing treatments for AV in patients with AD, further recommendations for adolescent athletes with AD, and which cosmetic and alternative medicine products may be beneficial for this population to improve their QOL.

Providers should discuss medical management in a broader context considering patients’ extracurricular activities, treatment vehicle preferences, expectations, and personal care habits. It also is important to address the many possible factors that may influence treatment adherence early on, particularly in adolescents, as these could be barriers to treatment. This article highlights considerations for treating AD and comorbid conditions that may further complicate treatment in adolescent patients with skin of color. The information provided should serve as a guide in initial counseling and management of AD in adolescents with skin of color.

- Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12:83-93.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357.

- Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E. Racial differences in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:449-455.

- Vivar KL, Kruse L. The impact of pediatric skin disease on self-esteem. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:27-31.

- Wan J, Margolis DJ, Mitra N, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in atopic dermatitis–related school absences among US children [published online May 22, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0597.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Ishikawa J, Narita H, Kondo N, et al. Changes in the ceramide profile of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2511-2514.

- Chernikova D, Yuan I, Shaker M. Prevention of allergy with diverse and healthy microbiota: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31:418-425.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Nguyen CM, Koo J, Cordoro KM. Psychodermatologic effects of atopic dermatitis and acne: a review on self-esteem and identity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:129-135.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

- Lynde CW, Andriessen A, Barankin B, et al. Moisturizers and ceramide-containing moisturizers may offer concomitant therapy with benefits. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:18-26.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden FE, McMichael A, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of topical dapsone gel, 7.5% for treatment of acne vulgaris by Fitzpatrick skin phototype. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:160-167.

- Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-236.

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402.

- Heath CR. Managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2018;102:71-73.

- Nagler AR, Milam EC, Orlow SJ. The use of oral antibiotics before isotretinoin therapy in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:273-279.

- Paller AS, McAlister RO, Doyle JJ, et al. Perceptions of physicians and pediatric patients about atopic dermatitis, its impact, and its treatment. Clin Pediatr. 2002;41:323-332.

- Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:303-316.

- Rocha VB, Machado CJ, Bittencourt FV. Presence of allergens in the vehicles of Brazilian dermatological products. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:126-128.

- Admani S, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact alopecia: improvement of alopecia with discontinuation of fluocinolone oil in individuals allergic to balsam fragrance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:e57-e60.

- Uter W, Werfel T, White IR, et al. Contact allergy: a review of current problems from a clinical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:E1108.

- López-Jiménez EC, Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L. One-third of patients with therapy-resistant atopic dermatitis may benefit after patch testing [published online May 13, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15672.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15.

- Hon KL, Tsang YC, Pong NH, et al. Patient acceptability, efficacy, and skin biophysiology of a cream and cleanser containing lipid complex with shea butter extract versus a ceramide product for eczema. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:417-425.

- Reynolds KA, Juhasz MLW, Mesinkovska NA. The role of oral vitamins and supplements in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review [published online March 20, 2019]. Int J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ijd.14404.

- Mottin VHM, Suyenaga ES. An approach on the potential use of probiotics in the treatment of skin conditions: acne and atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1425-1432.

- Callaway J, Schwab U, Harvima I, et al. Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:87-94.

- Eagleston LRM, Kalani NK, Patel RR, et al. Cannabinoids in dermatology: a scoping review [published June 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24.

- Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, et al. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-687.e611.

- de María Díaz Granados L, Quijano MA, Ramírez PA, et al. Quality assessment of atopic dermatitis clinical practice guidelines in ≤ 18 years. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:29-37.

- Feldman SR, Cox LS, Strowd LC, et al. The challenge of managing atopic dermatitis in the United States. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12:83-93.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman-Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357.

- Brunner PM, Guttman-Yassky E. Racial differences in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:449-455.

- Vivar KL, Kruse L. The impact of pediatric skin disease on self-esteem. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:27-31.

- Wan J, Margolis DJ, Mitra N, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in atopic dermatitis–related school absences among US children [published online May 22, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0597.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109-1122.

- Ishikawa J, Narita H, Kondo N, et al. Changes in the ceramide profile of atopic dermatitis patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2511-2514.

- Chernikova D, Yuan I, Shaker M. Prevention of allergy with diverse and healthy microbiota: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2019;31:418-425.

- Ben-Gashir MA, Hay RJ. Reliance on erythema scores may mask severe atopic dermatitis in black children compared with their white counterparts. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:920-925.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Nguyen CM, Koo J, Cordoro KM. Psychodermatologic effects of atopic dermatitis and acne: a review on self-esteem and identity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:129-135.

- Davis EC, Callender VD. A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:24-38.

- Lynde CW, Andriessen A, Barankin B, et al. Moisturizers and ceramide-containing moisturizers may offer concomitant therapy with benefits. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:18-26.

- Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden FE, McMichael A, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of topical dapsone gel, 7.5% for treatment of acne vulgaris by Fitzpatrick skin phototype. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:160-167.

- Draelos ZD. The multifunctionality of 10% sodium sulfacetamide, 5% sulfur emollient foam in the treatment of inflammatory facial dermatoses. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:234-236.

- Vachiramon V, Tey HL, Thompson AE, et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American children: addressing unmet needs of a common disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:395-402.

- Heath CR. Managing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2018;102:71-73.

- Nagler AR, Milam EC, Orlow SJ. The use of oral antibiotics before isotretinoin therapy in patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:273-279.

- Paller AS, McAlister RO, Doyle JJ, et al. Perceptions of physicians and pediatric patients about atopic dermatitis, its impact, and its treatment. Clin Pediatr. 2002;41:323-332.

- Sibbald C, Drucker AM. Patient burden of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:303-316.

- Rocha VB, Machado CJ, Bittencourt FV. Presence of allergens in the vehicles of Brazilian dermatological products. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:126-128.

- Admani S, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact alopecia: improvement of alopecia with discontinuation of fluocinolone oil in individuals allergic to balsam fragrance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:e57-e60.

- Uter W, Werfel T, White IR, et al. Contact allergy: a review of current problems from a clinical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:E1108.

- López-Jiménez EC, Marrero-Alemán G, Borrego L. One-third of patients with therapy-resistant atopic dermatitis may benefit after patch testing [published online May 13, 2019]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.15672.

- Karagounis TK, Gittler JK, Rotemberg V, et al. Use of “natural” oils for moisturization: review of olive, coconut, and sunflower seed oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:9-15.

- Hon KL, Tsang YC, Pong NH, et al. Patient acceptability, efficacy, and skin biophysiology of a cream and cleanser containing lipid complex with shea butter extract versus a ceramide product for eczema. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:417-425.

- Reynolds KA, Juhasz MLW, Mesinkovska NA. The role of oral vitamins and supplements in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review [published online March 20, 2019]. Int J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ijd.14404.

- Mottin VHM, Suyenaga ES. An approach on the potential use of probiotics in the treatment of skin conditions: acne and atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1425-1432.

- Callaway J, Schwab U, Harvima I, et al. Efficacy of dietary hempseed oil in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Treat. 2005;16:87-94.

- Eagleston LRM, Kalani NK, Patel RR, et al. Cannabinoids in dermatology: a scoping review [published June 15, 2018]. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24.

- Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, et al. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681-687.e611.

- de María Díaz Granados L, Quijano MA, Ramírez PA, et al. Quality assessment of atopic dermatitis clinical practice guidelines in ≤ 18 years. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:29-37.

Practice Points

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) can be a lifelong issue that affects academic and occupational performance, with higher rates of absenteeism seen in black patients.

- The FLG loss-of-function mutation seems to play a smaller role in black patients, and other genes may be involved in skin barrier dysfunction, which could be why there is a higher rate of skin of color patients with treatment-resistant AD.

- Diagnosing AD in skin of color patients can pose a particular challenge, and severe cases of AD may not be diagnosed or treated adequately in deeply pigmented children because erythema, a defining characteristic of AD, may be hard to identify in darker skin tones.

- There are several areas of opportunity for further research to better treat AD in this patient population and improve

quality of life.

Diversity and Inclusivity Are Essential to the Future of Dermatology

Over the last 5 years, there has been an important dialogue among dermatologists about diversity in our specialty that has shifted the mind-set of the dermatology community and highlighted an intent to build a diverse workforce. It is important to reflect on this effort and acknowledge the progress that has been made. Additionally, it also is important to envision what our ideal specialty will look like 10 years from now and to discuss specific ways that we can achieve that vision for the future of dermatology.

At the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), Bruce E. Wintroub, MD, highlighted the importance of diversity in dermatology when he presented the Clarence S. Livingood lecture.1 His discussion was followed by a call to action from Pandya et al2 in 2016, which described the lack of diversity in our specialty (the second least diverse specialty in medicine) and proposed specific steps that can be taken by individuals and organizations to address the issue. In line with this effort, the AAD’s Diversity Task Force, Diversity Mentorship Program,3 and Diversity Champion Initiative were created. The latter program enlisted dermatology residency programs across the country to select a diversity champion who would lead efforts to increase diversity in each participating department, including mentorship of underrepresented-in-medicine college and medical students. The AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop4 (September 12–13, 2019) will be held for the first time prior to the Association of Professors of Dermatology Annual Meeting (September 13–14, 2019) in an attempt to scale up the Diversity Champion Initiative. This workshop has galvanized widespread support and will be collaboratively hosted by the AAD, Association of Professors of Dermatology, Skin of Color Society, Society for Investigative Dermatology, and Women’s Dermatologic Society.

Current diversity efforts have largely focused on increasing representation in the dermatology workforce. A publication in 2017 challenged the tenets of dermatology resident selection and advocated for holistic review of residency program applicants as one way to address the lack of diversity in dermatology.5 This viewpoint highlighted that dermatology’s traditional focus on US Medical Licensing Examination scores and Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership leads to bias6-8; the viewpoint proposed several ways to change the resident selection process to enhance diversity.5 A recent proposal to eliminate numerical scores on the US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and move to a pass/fail grading system aligns well with this viewpoint.9 Defining best practices to perform holistic reviews is an ongoing effort and challenge for many programs, one that will be discussed at the AAD’s 2019 Diversity Champion Workshop. Implementing best practices will require individual residency programs to develop review processes tailored to departmental resources and strengths. Achieving increased representation must be an active process starting with an explicit commitment to improving diversity.

Through these efforts, we are poised to improve our specialty; however, it is critical to recognize that simply increasing the number of underrepresented dermatologists is not enough to improve diversity in dermatology. What does meaningful change look like? In 10 years, we hope that, in addition to a more inclusive workforce, we will see expanded diversity efforts beyond race and ethnicity; improved cultural competence within dermatology departments and organizations that creates more inclusive places to work, learn, and practice medicine; intentional broader representation in dermatology leadership; high-quality, evidence-based, inclusive, and culturally competent education, patient care, and research; and equal and improved outcomes for all of our patients, particularly those who traditionally experience health care disparities. To this end, ensuring diversity in research and publications is paramount. Academic journals should be actively working to include articles in the literature that help us better understand health care differences, including research that examines the presentations of skin disease in a broad spectrum of study populations, as well as to spotlight and solicit content from diverse voices. Inclusion of a diverse range of participants in research based on human subjects should be a requirement for publication, which would ensure more generalizable data. Diversity in clinical trials is improving,10 but more effort should be devoted to further increasing diversity in medical research. In particular, we need to broaden the inclusivity of dermatology research efforts and outcomes data to include more patients with skin of color as well as other underrepresented groups, thus helping to improve our understanding of the differential effects of certain interventions.

We also must educate trainees and practicing dermatologists to better understand the diagnosis and management of skin diseases in all populations; to this end, it is essential to develop a culturally competent curriculum and continuing medical education on diseases of the skin and hair that affect patients with skin of color as well as cutaneous conditions that present in groups such as sexual and gender minorities.11,12 All dermatologists—not just the experts in academic skin of color and other specialty clinics—should have expertise in the dermatologic care of diverse patients.

We have made notable and important strides with regard to diversity in dermatology by beginning this conversation, identifying problems, coming up with solutions, and implementing them.13 This progress has been made relatively quickly and is commendable; however, we have more work to do before our specialty is inclusive of underrepresented-in-medicine physicians and provides excellent care to all patients.

- Wintroub BE. Dermatology: insuring the future for the patients we serve. Presented at: 73rd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 20-24, 2015; San Francisco, California.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Diversity Mentorship Program: current mentors. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/members/leadership-institute/mentoring/diversity-mentorship-program-current-mentors. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Diversity Champion Workshop. American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/meetings/diversity-champion-workshop. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants—turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Wayne DB. Are United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 and 2 scores valid measures for postgraduate medical residency selection decisions? Acad Med. 2011;86:48-52.

- Edmond MB, Deschenes JL, Eckler M, et al. Racial bias in using USMLE step 1 scores to grant internal medicine residency interviews. Acad Med. 2001;76:1253-1256.

- Boatright D, Ross D, O’Connor P, et al. Racial disparities in medical student membership in the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Society. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:659-665.

- The conversation continues: exploring possible changes to USMLE score reporting. US Medical Licensing Examination website. https://www.usmle.org/usmlescoring/. Accessed July 17, 2019.

- Charrow A, Xia FD, Joyce C, et al. Diversity in dermatology clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:193-198.