User login

More on How to Decrease Dermatology Interview Costs

To the Editor:

Ongoing concern about the high costs of dermatology residency interviews has led to several cost-saving proposals, as presented by Hussain1 in the Cutis article, “Reducing the Cost of Dermatology Residency Applications: An Applicant’s Perspective.” Additional strategies to reduce applicant costs include eliminating travel costs through video or telephone interviews, interviewing students who are visiting during their away rotation, and developing and implementing a mechanism to exempt students from participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service (

First, because applicants would be limited to 1 application to participate in the early decision program, they must realistically consider the strength of their application and weigh their chances for acceptance to that program. Programs could facilitate the process by becoming more transparent about the type of applicants that have previously matched in their program.2 If an early-decision applicant successfully matches, that applicant would be prohibited from applying to additional dermatology residency programs through

Second, early-decision actions by programs—probably by August 1, a time when most third-year medical students have completed their academic year—would be determined before ERAS releases applications to residency programs. This timeline would remove successful applicants in the early decision program from going to additional interviews and incurring the associated travel costs.

Third, early decision could be potentially beneficial to applicants who are tied to a specific geographic region for training and to programs with specific program needs, such as expertise in specific areas of dermatology research or areas of clinical need (eg, adding a dermatopathologist, plastic surgeon, internist, or a pediatrician to the residency program who now wants dermatology training) or other program needs.

Fourth, application costs could potentially be lower for early-decision applicants than through the present application process if participating institutions waived application fees. Applicants would still be responsible for submitting requested academic transcripts, letters of recommendation, and travel expenses if an on-site interview is requested by the program.

Finally, highly desirable applicants who are offered a position through early decision would result in more opportunities for other applicants to interview for the remaining available residency positions through ERAS/NRMP.

Downsides to early decision for dermatology residency include the inability of applicants to compare programs to one another through their personal experiences, such as prior rotations or interviews, and for programs to compare applicants though the interview process and away rotations. In addition, US Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 scores and Alpha Omega Alpha honor medical society status and other academic honors may not be available to programs to consider at the time of early decision. Cooperation would be needed with ERAS and NRMP to create an early decision program for dermatology residency.

One other potential consequence of the early match could involve instances of strained relationships between research fellows and their sponsoring institution or dermatology program. Research fellows often match at their research institution, and failing to early match could potentially sour the relationship between the applicant and the program, thus leading to a less productive year. However, many programs participating in an early match will probably have additional residency positions remaining in the traditional match that would be still available to the fellows.

The concept of an early-binding residency match process has the potential to save both time and money for programs and applicants. Although an early-match process would have many positive effects, there also would be inherent downsides that accompany such a system. Nonetheless, an early-match process in dermatology has the prospect of efficiently pairing applicants and programs that feel strongly about each other while simplifying the match process and reducing costs for all parties involved.

References

1. Hussain AN.

2. Weisert E, Phan M. Thoughts on reducing the cost for dermatology residency applications. DIG@UTMB blog. http://digutmb.blogspot.com/2019/12/thoughts-on-reducing-cost-for.html. Published December 23, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

3. Early decision program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/early-decision-program/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Author’s Response

The early decision option for dermatology residency applications would be a welcomed addition to the process but may be complicated by 2 recent events: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the change of US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting to a pass/fail system.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused remarkable economic distress and likely affects medical students more acutely given their high levels of debt. As Ryan and Wagner observed, one advantage of the early-decision option would be financial relief for certain students. If applicants successfully match during the early-decision phase, they will not need to apply to any additional dermatology programs and also can target their preliminary-year applications to the geographic region where they have already matched.

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic may further reduce early applicants’ ability to visit programs in person. Various medical schools have curtailed away rotations, and programs may opt for virtual interviews in accordance with social distancing guidelines.1 Thus, early applicants will have even fewer opportunities to compare programs before they must make a binding decision about their residency placement. Although away rotations and interview travel are some of the largest drivers of application cost,2 reducing costs in this way might shortchange both students and programs.

Arguably, the change in USMLE Step 1 score reporting beginning in 2022 may impact residency selection for a longer period of time than the COVID-19 pandemic. Program directors cited USMLE Step 1 scores as one of the main factors determining which applicants may be invited to interview.3 The lack of numerical USMLE Step 1 scores may encourage programs to place more weight on other metrics such as USMLE Step 2 CK scores or Alpha Omega Alpha membership.4 However, as Ryan and Wagner point out, such metrics may not be available in time for early-decision applicants.

As such, future program directors will have precious little information to screen early-decision applicants and may need to conduct holistic application review. This would require increased time and manpower compared to screening based on traditional metrics but may lead to a better “fit” for an applicant with a residency.

In general, implementation of any early decision program would benefit dermatology applicants as a group by removing elite candidates from the applicant pool. According to National Resident Matching Program data, just 3% of dermatology applicants account for more than 12% of overall interviews.5 In other words, a small group of the strongest applicants receives a lion’s share of interviews, crowding out many other candidates. Removing these top-tier applicants likely would provide remaining applicants with a higher return on investment per application, and students may choose to save money by applying to fewer programs.

Adopting early-decision options within the dermatology match may be complicated given the COVID-19 pandemic and USMLE score changes but may spur positive changes in the process while also reducing the financial burden on applicants.

Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP

From Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP ([email protected]).

References

1. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the VSLO program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/coronavirus-covid-19-and-vslo-program/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

2. Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

3. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed April 17, 2020.

4. Crane MA, Chang HA, Azamfirei R. Medical education takes a step in the right direction: where does that leave students? [published online March 6, 2020]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2950.

5. Lee AH, Young P, Liao R, et al. I dream of Gini: quantifying inequality in otolaryngology residency interviews. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:627-633.

To the Editor:

Ongoing concern about the high costs of dermatology residency interviews has led to several cost-saving proposals, as presented by Hussain1 in the Cutis article, “Reducing the Cost of Dermatology Residency Applications: An Applicant’s Perspective.” Additional strategies to reduce applicant costs include eliminating travel costs through video or telephone interviews, interviewing students who are visiting during their away rotation, and developing and implementing a mechanism to exempt students from participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service (

First, because applicants would be limited to 1 application to participate in the early decision program, they must realistically consider the strength of their application and weigh their chances for acceptance to that program. Programs could facilitate the process by becoming more transparent about the type of applicants that have previously matched in their program.2 If an early-decision applicant successfully matches, that applicant would be prohibited from applying to additional dermatology residency programs through

Second, early-decision actions by programs—probably by August 1, a time when most third-year medical students have completed their academic year—would be determined before ERAS releases applications to residency programs. This timeline would remove successful applicants in the early decision program from going to additional interviews and incurring the associated travel costs.

Third, early decision could be potentially beneficial to applicants who are tied to a specific geographic region for training and to programs with specific program needs, such as expertise in specific areas of dermatology research or areas of clinical need (eg, adding a dermatopathologist, plastic surgeon, internist, or a pediatrician to the residency program who now wants dermatology training) or other program needs.

Fourth, application costs could potentially be lower for early-decision applicants than through the present application process if participating institutions waived application fees. Applicants would still be responsible for submitting requested academic transcripts, letters of recommendation, and travel expenses if an on-site interview is requested by the program.

Finally, highly desirable applicants who are offered a position through early decision would result in more opportunities for other applicants to interview for the remaining available residency positions through ERAS/NRMP.

Downsides to early decision for dermatology residency include the inability of applicants to compare programs to one another through their personal experiences, such as prior rotations or interviews, and for programs to compare applicants though the interview process and away rotations. In addition, US Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 scores and Alpha Omega Alpha honor medical society status and other academic honors may not be available to programs to consider at the time of early decision. Cooperation would be needed with ERAS and NRMP to create an early decision program for dermatology residency.

One other potential consequence of the early match could involve instances of strained relationships between research fellows and their sponsoring institution or dermatology program. Research fellows often match at their research institution, and failing to early match could potentially sour the relationship between the applicant and the program, thus leading to a less productive year. However, many programs participating in an early match will probably have additional residency positions remaining in the traditional match that would be still available to the fellows.

The concept of an early-binding residency match process has the potential to save both time and money for programs and applicants. Although an early-match process would have many positive effects, there also would be inherent downsides that accompany such a system. Nonetheless, an early-match process in dermatology has the prospect of efficiently pairing applicants and programs that feel strongly about each other while simplifying the match process and reducing costs for all parties involved.

References

1. Hussain AN.

2. Weisert E, Phan M. Thoughts on reducing the cost for dermatology residency applications. DIG@UTMB blog. http://digutmb.blogspot.com/2019/12/thoughts-on-reducing-cost-for.html. Published December 23, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

3. Early decision program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/early-decision-program/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Author’s Response

The early decision option for dermatology residency applications would be a welcomed addition to the process but may be complicated by 2 recent events: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the change of US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting to a pass/fail system.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused remarkable economic distress and likely affects medical students more acutely given their high levels of debt. As Ryan and Wagner observed, one advantage of the early-decision option would be financial relief for certain students. If applicants successfully match during the early-decision phase, they will not need to apply to any additional dermatology programs and also can target their preliminary-year applications to the geographic region where they have already matched.

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic may further reduce early applicants’ ability to visit programs in person. Various medical schools have curtailed away rotations, and programs may opt for virtual interviews in accordance with social distancing guidelines.1 Thus, early applicants will have even fewer opportunities to compare programs before they must make a binding decision about their residency placement. Although away rotations and interview travel are some of the largest drivers of application cost,2 reducing costs in this way might shortchange both students and programs.

Arguably, the change in USMLE Step 1 score reporting beginning in 2022 may impact residency selection for a longer period of time than the COVID-19 pandemic. Program directors cited USMLE Step 1 scores as one of the main factors determining which applicants may be invited to interview.3 The lack of numerical USMLE Step 1 scores may encourage programs to place more weight on other metrics such as USMLE Step 2 CK scores or Alpha Omega Alpha membership.4 However, as Ryan and Wagner point out, such metrics may not be available in time for early-decision applicants.

As such, future program directors will have precious little information to screen early-decision applicants and may need to conduct holistic application review. This would require increased time and manpower compared to screening based on traditional metrics but may lead to a better “fit” for an applicant with a residency.

In general, implementation of any early decision program would benefit dermatology applicants as a group by removing elite candidates from the applicant pool. According to National Resident Matching Program data, just 3% of dermatology applicants account for more than 12% of overall interviews.5 In other words, a small group of the strongest applicants receives a lion’s share of interviews, crowding out many other candidates. Removing these top-tier applicants likely would provide remaining applicants with a higher return on investment per application, and students may choose to save money by applying to fewer programs.

Adopting early-decision options within the dermatology match may be complicated given the COVID-19 pandemic and USMLE score changes but may spur positive changes in the process while also reducing the financial burden on applicants.

Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP

From Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP ([email protected]).

References

1. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the VSLO program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/coronavirus-covid-19-and-vslo-program/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

2. Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

3. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed April 17, 2020.

4. Crane MA, Chang HA, Azamfirei R. Medical education takes a step in the right direction: where does that leave students? [published online March 6, 2020]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2950.

5. Lee AH, Young P, Liao R, et al. I dream of Gini: quantifying inequality in otolaryngology residency interviews. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:627-633.

To the Editor:

Ongoing concern about the high costs of dermatology residency interviews has led to several cost-saving proposals, as presented by Hussain1 in the Cutis article, “Reducing the Cost of Dermatology Residency Applications: An Applicant’s Perspective.” Additional strategies to reduce applicant costs include eliminating travel costs through video or telephone interviews, interviewing students who are visiting during their away rotation, and developing and implementing a mechanism to exempt students from participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service (

First, because applicants would be limited to 1 application to participate in the early decision program, they must realistically consider the strength of their application and weigh their chances for acceptance to that program. Programs could facilitate the process by becoming more transparent about the type of applicants that have previously matched in their program.2 If an early-decision applicant successfully matches, that applicant would be prohibited from applying to additional dermatology residency programs through

Second, early-decision actions by programs—probably by August 1, a time when most third-year medical students have completed their academic year—would be determined before ERAS releases applications to residency programs. This timeline would remove successful applicants in the early decision program from going to additional interviews and incurring the associated travel costs.

Third, early decision could be potentially beneficial to applicants who are tied to a specific geographic region for training and to programs with specific program needs, such as expertise in specific areas of dermatology research or areas of clinical need (eg, adding a dermatopathologist, plastic surgeon, internist, or a pediatrician to the residency program who now wants dermatology training) or other program needs.

Fourth, application costs could potentially be lower for early-decision applicants than through the present application process if participating institutions waived application fees. Applicants would still be responsible for submitting requested academic transcripts, letters of recommendation, and travel expenses if an on-site interview is requested by the program.

Finally, highly desirable applicants who are offered a position through early decision would result in more opportunities for other applicants to interview for the remaining available residency positions through ERAS/NRMP.

Downsides to early decision for dermatology residency include the inability of applicants to compare programs to one another through their personal experiences, such as prior rotations or interviews, and for programs to compare applicants though the interview process and away rotations. In addition, US Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 scores and Alpha Omega Alpha honor medical society status and other academic honors may not be available to programs to consider at the time of early decision. Cooperation would be needed with ERAS and NRMP to create an early decision program for dermatology residency.

One other potential consequence of the early match could involve instances of strained relationships between research fellows and their sponsoring institution or dermatology program. Research fellows often match at their research institution, and failing to early match could potentially sour the relationship between the applicant and the program, thus leading to a less productive year. However, many programs participating in an early match will probably have additional residency positions remaining in the traditional match that would be still available to the fellows.

The concept of an early-binding residency match process has the potential to save both time and money for programs and applicants. Although an early-match process would have many positive effects, there also would be inherent downsides that accompany such a system. Nonetheless, an early-match process in dermatology has the prospect of efficiently pairing applicants and programs that feel strongly about each other while simplifying the match process and reducing costs for all parties involved.

References

1. Hussain AN.

2. Weisert E, Phan M. Thoughts on reducing the cost for dermatology residency applications. DIG@UTMB blog. http://digutmb.blogspot.com/2019/12/thoughts-on-reducing-cost-for.html. Published December 23, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

3. Early decision program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/early-decision-program/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

Author’s Response

The early decision option for dermatology residency applications would be a welcomed addition to the process but may be complicated by 2 recent events: the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the change of US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score reporting to a pass/fail system.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused remarkable economic distress and likely affects medical students more acutely given their high levels of debt. As Ryan and Wagner observed, one advantage of the early-decision option would be financial relief for certain students. If applicants successfully match during the early-decision phase, they will not need to apply to any additional dermatology programs and also can target their preliminary-year applications to the geographic region where they have already matched.

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic may further reduce early applicants’ ability to visit programs in person. Various medical schools have curtailed away rotations, and programs may opt for virtual interviews in accordance with social distancing guidelines.1 Thus, early applicants will have even fewer opportunities to compare programs before they must make a binding decision about their residency placement. Although away rotations and interview travel are some of the largest drivers of application cost,2 reducing costs in this way might shortchange both students and programs.

Arguably, the change in USMLE Step 1 score reporting beginning in 2022 may impact residency selection for a longer period of time than the COVID-19 pandemic. Program directors cited USMLE Step 1 scores as one of the main factors determining which applicants may be invited to interview.3 The lack of numerical USMLE Step 1 scores may encourage programs to place more weight on other metrics such as USMLE Step 2 CK scores or Alpha Omega Alpha membership.4 However, as Ryan and Wagner point out, such metrics may not be available in time for early-decision applicants.

As such, future program directors will have precious little information to screen early-decision applicants and may need to conduct holistic application review. This would require increased time and manpower compared to screening based on traditional metrics but may lead to a better “fit” for an applicant with a residency.

In general, implementation of any early decision program would benefit dermatology applicants as a group by removing elite candidates from the applicant pool. According to National Resident Matching Program data, just 3% of dermatology applicants account for more than 12% of overall interviews.5 In other words, a small group of the strongest applicants receives a lion’s share of interviews, crowding out many other candidates. Removing these top-tier applicants likely would provide remaining applicants with a higher return on investment per application, and students may choose to save money by applying to fewer programs.

Adopting early-decision options within the dermatology match may be complicated given the COVID-19 pandemic and USMLE score changes but may spur positive changes in the process while also reducing the financial burden on applicants.

Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP

From Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Aamir N. Hussain, MD, MAPP ([email protected]).

References

1. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the VSLO program. Association of American Medical Colleges website. https://students-residents.aamc.org/attending-medical-school/article/coronavirus-covid-19-and-vslo-program/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

2. Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

3. National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee. Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf. Published June 2018. Accessed April 17, 2020.

4. Crane MA, Chang HA, Azamfirei R. Medical education takes a step in the right direction: where does that leave students? [published online March 6, 2020]. JAMA. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2950.

5. Lee AH, Young P, Liao R, et al. I dream of Gini: quantifying inequality in otolaryngology residency interviews. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:627-633.

The American maternal mortality crisis: The role of racism and bias

April 11-17 marked the third annual national Black Maternal Health Week, an event launched in 2017 by the Atlanta-based Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA), in part to “deepen the national conversation about black maternal health.”

Around the same time, emerging data showing higher mortality rates among black patients versus patients of other races with COVID-19 opened similar dialogue fraught with questions about what might explain the disturbing health disparities.

“It’s kind of surprising to me that people are shocked by these [COVID-19] disparities,” Rebekah Gee, MD, an ob.gyn. who is director of the Louisiana State University Health System in New Orleans and a driving force behind initiatives addressing racial disparities in maternal health, said in an interview. If this is it, great – and certainly every moment is a moment for learning – but these COVID-19 disparities should not be surprising to people who have been looking at data.”

Veronica Gillispie, MD, an ob.gyn. and medical director of the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review, was similarly baffled that the news was treated as a revelation.

That news includes outcomes data from New York showing that in March there were 92.3 and 74.3 deaths per 100,000 black and Hispanic COVID-19 patients, respectively, compared with 45.2 per 100,000 white patients.

“Now there’s a task force and all these initiatives to look at why this is happening, and I think those of us who work in maternal mortality are all saying, ‘We know why it’s happening,’ ” she said. “It’s the same thing we’ve been telling people why it’s been happening in maternal mortality.

“It’s implicit bias and structural racism.”

Facing hard numbers, harder conversations

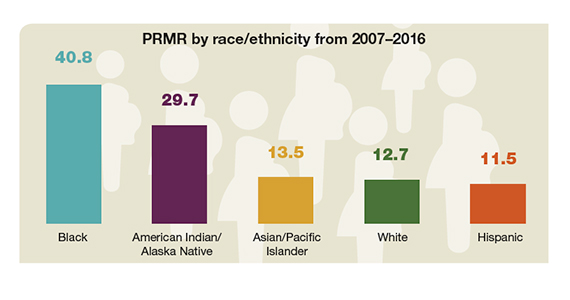

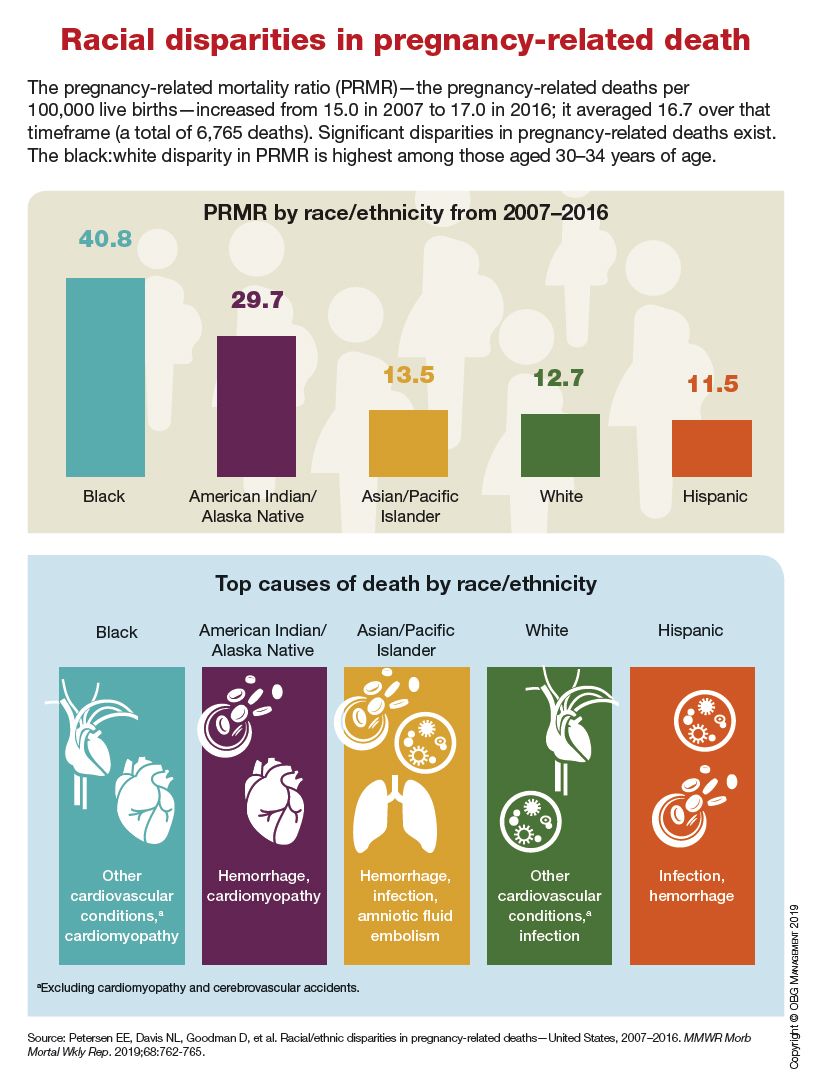

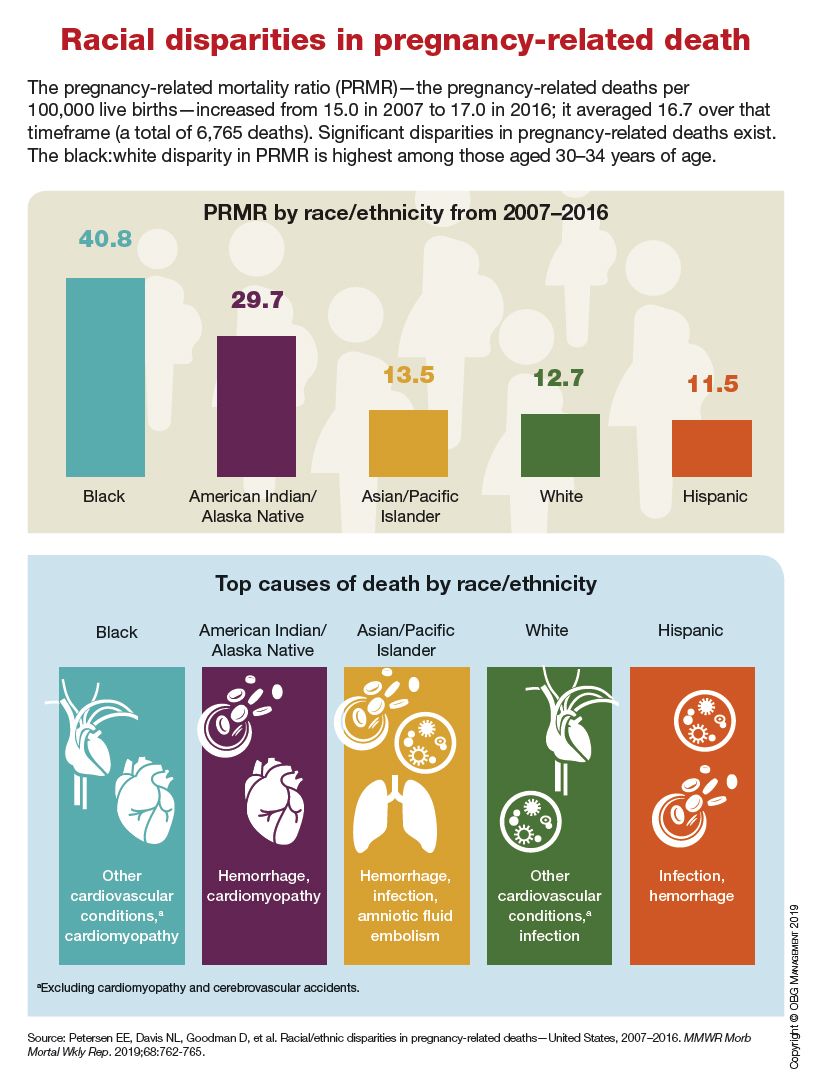

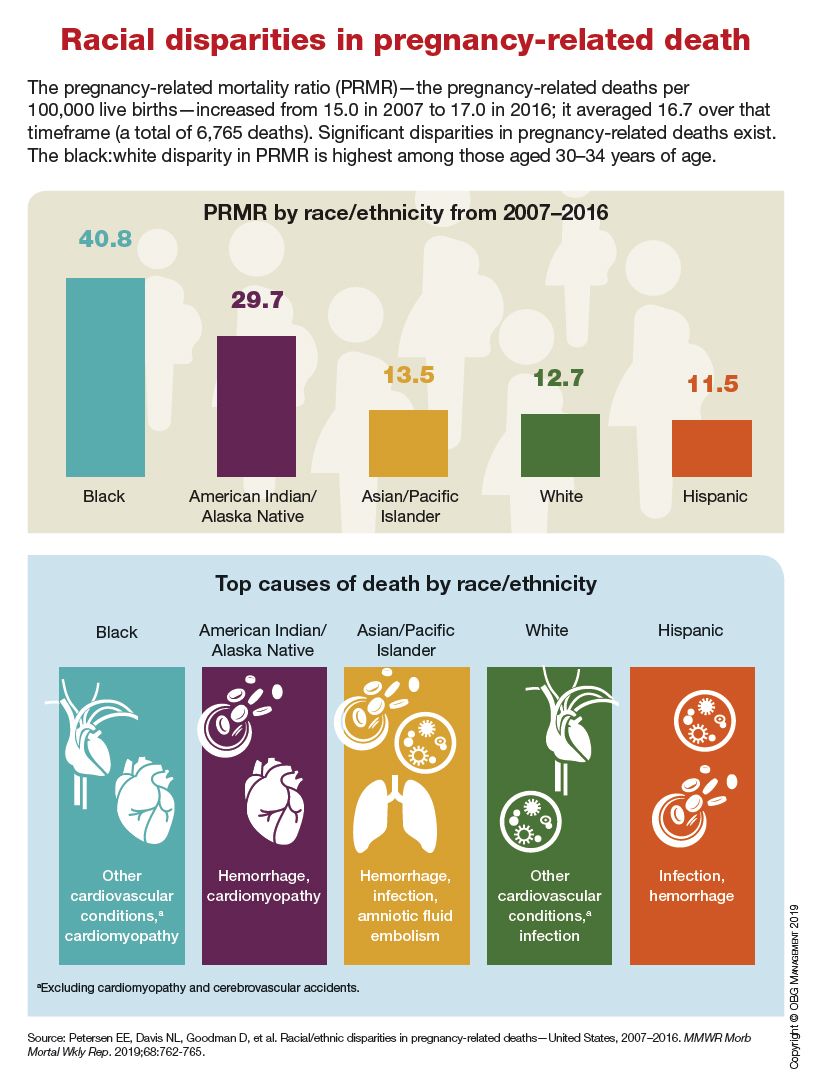

The U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2018 was 17 per 100,000 live births – the highest of any similarly wealthy industrialized nation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported in January. That’s a striking statistic in its own right. Perhaps more striking is the breakdown by race.

Hispanic women had the lowest maternal mortality rate at 12 per 100,000 live births, followed by non-Hispanic white women at 15.

The rate for non-Hispanic black women was 37 per 100,000 live births.

Numerous factors contribute to these disparities. Among those listed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ chief executive officer Maureen G. Phipps, MD, in a press statement on the NCHS data, are care access issues, lack of standardization of care, bias, and racism. All of these must be addressed if the disparities in maternal and other areas of care are to be eliminated, according to Dr. Phipps.

“The NCHS data confirmed what we have known from other data sources: The rate of maternal deaths for non-Hispanic black women is substantially higher than the rates for non-Hispanic white women,” she wrote. “Continued efforts to improve the standardization of data and review processes related to U.S. maternal mortality are a necessary step to achieving the goal of eliminating disparities and preventable maternal mortality.”

However, such efforts frequently encounter roadblocks constructed by the reluctance among “many academics, policy makers, scientists, elected officials, journalists, and others responsible for defining and responding to the public discourse” to identify racism as a root cause of health disparities, according to Zinzi D. Bailey, ScD, former director of research and evaluation for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and colleagues.

In the third of a three-part conceptual report in The Lancet, entitled America: Equity and Equality in Health, Dr. Bailey and colleagues argued that advancing health equity requires a focus on structural racism – which they defined as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination via mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (e.g., in housing, education, employment, earning, benefits, credit, media, healthcare, and criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.”

In their series, the authors peeled back layer upon layer of sociological and political contributors to structural racism throughout history, revealing how each laid a foundation for health inequity over time. They particularly home in on health care quality and access.

“Interpersonal racism, bias, and discrimination in healthcare settings can directly affect health through poor health care,” they wrote, noting that “almost 15 years ago, the Institute of Medicine report entitled Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, documented systematic and pervasive bias in the treatment of people of color resulting in substandard care.”

That report concluded that “bias, stereotyping, prejudice, and clinical uncertainty on the part of healthcare providers” likely play a role in the continuation of health disparities. More recent data – including the NCHS maternal mortality data – show an ongoing crisis.

A study of 210 experienced primary care providers and 190 community members in the Denver area, for example, found substantial evidence of implicit bias against both Latino and African American patients. The authors defined implicit bias as “unintentional and even unconscious” negative evaluation of one group and its members relative to another that is expressed implicitly, such as through negative nonverbal behavior.

“Activated by situational cues (e.g., a person’s skin color), implicit bias can quickly and unknowingly exert its influence on perception, memory, and behavior,” they wrote.

In their study, Implicit Association Test and self-report measures of bias showed similar rates of implicit bias among the providers and community members, with only a slight weakening of ethnic/racial bias among providers after adjustment for background characteristics, which suggests “a wider societal problem,” they said.

A specific example of how implicit bias can manifest was described in a 2016 report addressing the well-documented under-treatment of pain among black versus white patients. Kelly M. Hoffman, PhD, and colleagues demonstrated that a substantial number of individuals with at least some medical training endorse false beliefs regarding biological differences between black and white patients. For example, 25% of 28 white residents surveyed agreed black individuals have thicker skin, and 4% believed black individuals have faster blood coagulation and less sensitivity in their nerve endings.

Those who more strongly endorsed such erroneous beliefs were more likely to underestimate and undertreat pain among black patients, the authors found.

Another study, which underscored the insidiousness of structural racism, was reported in Science. The authors identified significant racial bias in an algorithm widely used by health systems, insurers, and practitioners to allocate health care resources for patients with complex health needs. The algorithm, which affects millions of patients, uses predictions of future health care costs rather than future illness to determine who should receive extra medical care.

The problem is that unequal care access for black patients skews lower the foundational cost data used for making those predictions. Correcting the algorithm would increase the percentage of black patients receiving additional medical help from 17.7% to 46.5%, the authors concluded.

This evidence of persistent racism and bias in medicine, however, doesn’t mean progress is lacking.

ACOG has partnered with numerous other organizations to promote awareness and change, including through legislation. A recent win was the enactment of the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, a bipartisan bill designed to promote and support maternal mortality review committees in every state. A major focus of BMMA’s Black Maternal Health Week was the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2020, a nine-bill package introduced in March to comprehensively address the crisis.

But efforts like these, whether they aim to elucidate the contributors to health disparities or to directly target structural and overt racism and root out implicit bias in medical care, are nothing new. As Dr. Bailey and colleagues noted, a challenge is getting the message across because efforts to avoid tough conversations around these topics are nothing new, either.

Dr. Gee attested to that during a maternal mortality panel discussion at the 2019 ACOG meeting where she spoke about the resistance she encountered in 2016 when she was appointed secretary of the Louisiana Health Department and worked to make racism and bias a foundational part of the discussion on improving maternal and fetal outcomes.

She established the first Office of Health Equity in the state – and the first in the nation to not only require measurement outcomes by race but also explicitly address racial bias at the outset. The goal wasn’t just to talk about it but to “plan for addressing equity in every single aspect of what we do with ... our case equity action teams.”

“At our first maternal mortality quality meetings we insisted on focusing on equity at the very outset, and we had people that left when we started talking about racism,” she said, noting that others said it was “too political” to discuss during an election year or that equity was something to address later.

“We said no. We insisted on it, and I think that was very important because all ships don’t rise with the tide, not with health disparities,” she said, recounting an earlier experience when she led the Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative: “I asked to have a brown-bag focused on racism at the department so we could talk about the impact of implicit bias on decision making, and I was told that I was a Yankee who didn’t understand the South and that racism didn’t really exist here, and what did I know about it – and I couldn’t have the brown-bag.”

That was in 2011.

Fast-forward to April 24, 2020. As Dr. Gee shared her perspective on addressing racism and bias in medicine, she was preparing for a call regarding the racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes – the first health equity action sanctioned by Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards (D).

“I think we really set the stage for these discussions,” she said.

Addressing equity to enact change

The efforts in Louisiana also set the stage for better maternal outcomes. At the 2019 ACOG meeting where she spoke as part of the President’s Panel, Dr. Gee said Louisiana had the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation. The NCHC data released in January, however, suggest that may no longer be the case.

Inconsistencies in how the latest and prior data were reported, including in how maternal mortality was defined, make direct comparison impossible. But in the latest report, Louisiana ranked seventh among states with available data.

“Ninety percent of the deliveries in the state happen at hospitals that we worked with,” Dr. Gee said, highlighting the reach of the efforts to improve outcomes there.

She also described a recent case involving an anemic patient whose bleeding risk was identified early thanks to the programs put in place. That enabled early preparation in the event of complications.

The patient experienced a massive hemorrhage, but the preparation, including having units of blood on hand in case of such an emergency, saved her life.

“So we clearly have not just data, but individual stories of people whose lives have been saved by this work,” she said.

More tangible data on maternal morbidity further show that the efforts in the state are making a difference, Dr. Gillispie said, citing preliminary outcomes data from the Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review launched in 2018.

“We started with an initial goal of reducing severe maternal morbidity related to hypertension and hemorrhage by 20%, as well as reducing the black/white disparity gap by Mother’s Day 2020,” she said.

Final analyses have been delayed because of COVID-19, but early assessments showed a reduction in the disparity gap, she said, again highlighting the importance of focusing on equity.

“Definitely from the standpoint of the Quality Collaborative side ... we’ve been working with our facilities to make them aware of what implicit bias is, helping them to also do the Harvard Implicit Bias Test so they can figure out what their own biases are, start working to acknowledge them and address them, and start working to fight against letting that bias change how they treat individuals,” Dr. Gillispie said.

The work started through these initiatives will continue because there is much left to be done, she said.

Indeed, the surprised reactions in recent weeks to the reports of disparities in COVID-19 outcomes further underscore that reality, and the maternal mortality statistics – with use of the voices of those directly affected by structural and overt racism and bias in maternal care as a megaphone – speak for themselves.

Hearing implicit bias from patients’ perspective

Just ask Timoria McQueen Saba, a black woman who nearly died from a postpartum hemorrhage in 2010. At ACOG 2019, she spoke about how she had to switch ob.gyns. three times during her first pregnancy because she felt she had not received quality care – one doctor neglected to tell her she had placenta previa. She also experienced excessive wait times at prenatal appointments and had been on the receiving end of microaggressions and degrading questions such as “Are you still married?” and “Is your husband your baby’s father?” – and these are all things her white friends who recommended those physicians never experienced, she said.

“The health care system has just sometimes beaten people down so much, just like the world has – people of color, especially – to where you’re dismissed, your concerns are invalidated,” she said. “Some doctors don’t even think black people feel pain [or that] our pain is less.”

Mrs. Saba also spoke about how her health care “improved a billion percent” when her white husband accompanied her to appointments.

Just ask Charles S. Johnson IV, whose wife Kira Dixon Johnson died in 2016 during surgery for postpartum bleeding complications – after he and other family members spent 10 hours pleading for help for her.

Speaking at the ACOG panel discussion with Mrs. Saba, Mr. Johnson described “a clear disconnect” between the medical staff at the hospital and the way they viewed and valued Kira. He shared his frustration in wanting to advocate for his wife, but knowing that, as an African American male, he risked being seen as a threat and removed from the hospital if he didn’t stay calm, if he “tapped into those natural instincts as a man and a husband who wants to just protect his family.”

He fought back emotions, struggling to get the words out, saying that’s what haunts him and keeps him up at night – wondering if he should have “fought harder, grabbed the doctor by the collar, raised his voice, slammed on the counter.

“Maybe they would have done something,” he said.

Such experiences cross all socioeconomic boundaries. Ask U.S. Track and Field Olympic gold medalist Allyson Felix, who testified at a U.S. House Ways and Means Committee hearing on May 16, 2019 after developing severe preeclampsia that threatened her life and that of her baby. Ask tennis champion Serena Williams, who demanded assessment for pulmonary embolism following the birth of her child; she knew the signs, but her health care providers initially dismissed her concerns.

Their experiences aren’t just anecdotal. Data consistently show how racism and bias affect patient treatment and outcomes. Dr. Gee, for example, shared findings from a retrospective assessment of 47 confirmed pregnancy-related deaths in Louisiana between 2011 and 2016 that looked specifically at whether the deaths could potentially have been prevented if blood was given sooner, cardiomyopathy was recognized sooner, hypertension was treated on time, or other changes were made to care.

The answer was “Yes” in 9% of cases involving white patients – and in 59% of cases involving black patients (odds ratio, 14.6).

The study, reported in February in Obstetrics & Gynecology, showed that 27 of the deaths (58%) occurred at level III or IV birth facilities and that those deaths were not less likely than those at level I or II facilities to be categorized as preventable (OR, 2.0).

Findings from the Giving Voice to Mothers study, published in Reproductive Health in 2019, showed how mistreatment during childbirth might contribute to such outcomes.

In an online cross-sectional survey of more than 2,100 U.S. women, one in six reported at least one type of mistreatment, such as loss of autonomy, being yelled at or threatened, being ignored or having requests for help ignored, Saraswathi Vedam, SciD, of the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues reported.

Race was among the factors associated with likelihood of mistreatment, and the rates of mistreatment for women of color were consistently higher – even when looking at interactions between race and other characteristics, such as socioeconomic status (SES). For example, 27.2% of women of color with low SES, compared with 18.7% of white women with low SES, reported mistreatment. Having a partner who was black, regardless of maternal race, was also associated with an increased rate of mistreatment, the authors found.

“I often get the question, ‘Do you think Kira would be alive if she was white,’ ” Mr. Johnson said. “The first way I respond to that question is [by saying that] the simple fact that you have to ask me is a problem.

“When this first happened, I was in so much pain that I couldn’t process the fact that something so egregious and outrageous happened to my wife because of the color of her skin, but as I began to process and really think about it and unpack this scenario, I have to be really frank ... do I think that she would have sat there for 10 hours while we begged and pleaded? Absolutely not.”

He stressed that his words aren’t “an indictment of the profession.”

“This is not an indictment saying that all people are racist or prejudiced,” he said. “But here’s the reality: If you are in this profession, if you are responsible for the well-being of patients and their families, and you are not able to see them in the same way that you see your mother, your wife, your sister, you have two options – you need to find something else to do or you need to take steps to get better.”

Fixing systems, finding solutions

Dr. Gee acknowledged the work that physicians need to do to help improve outcomes.

“The average time we give a patient to talk is 11 seconds before we interrupt them,” she said, as one example. “We have to recognize that.”

But efforts to improve outcomes shouldn’t just focus on changing physician behavior, she said.

“We really need to focus, as has the U.K. – very effectively – on using midwives, doulas, other health care professionals as complements to physicians to make sure that we have women-centered birth experiences.

“So, instead of just blaming the doctors, I think we need to change the system,” Dr. Gee emphasized.

The disruptions in health systems caused by COVID-19 present a unique opportunity to do that, she said. There is now an opportunity to build them back.

“We have a chance to build the systems back, and when we do so, we ought to build them back correcting for implicit bias and some of the systemic issues that lead to poor outcomes for people of color in our country,” she said.

Solutions proposed by Dr. Gee and others include more diversity in the workforce, more inclusion of patient advocates in maternal care, development of culturally appropriate literacy and numeracy communications, measurement by race (and action on the outcomes), standardization of care, and development of new ways to improve care access.

We will focus more specifically on these solutions in Part 2 of this article in our maternal mortality series. Previous articles in the series are available at mdedge.com/obgyn/maternal-mortality.

April 11-17 marked the third annual national Black Maternal Health Week, an event launched in 2017 by the Atlanta-based Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA), in part to “deepen the national conversation about black maternal health.”

Around the same time, emerging data showing higher mortality rates among black patients versus patients of other races with COVID-19 opened similar dialogue fraught with questions about what might explain the disturbing health disparities.

“It’s kind of surprising to me that people are shocked by these [COVID-19] disparities,” Rebekah Gee, MD, an ob.gyn. who is director of the Louisiana State University Health System in New Orleans and a driving force behind initiatives addressing racial disparities in maternal health, said in an interview. If this is it, great – and certainly every moment is a moment for learning – but these COVID-19 disparities should not be surprising to people who have been looking at data.”

Veronica Gillispie, MD, an ob.gyn. and medical director of the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review, was similarly baffled that the news was treated as a revelation.

That news includes outcomes data from New York showing that in March there were 92.3 and 74.3 deaths per 100,000 black and Hispanic COVID-19 patients, respectively, compared with 45.2 per 100,000 white patients.

“Now there’s a task force and all these initiatives to look at why this is happening, and I think those of us who work in maternal mortality are all saying, ‘We know why it’s happening,’ ” she said. “It’s the same thing we’ve been telling people why it’s been happening in maternal mortality.

“It’s implicit bias and structural racism.”

Facing hard numbers, harder conversations

The U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2018 was 17 per 100,000 live births – the highest of any similarly wealthy industrialized nation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported in January. That’s a striking statistic in its own right. Perhaps more striking is the breakdown by race.

Hispanic women had the lowest maternal mortality rate at 12 per 100,000 live births, followed by non-Hispanic white women at 15.

The rate for non-Hispanic black women was 37 per 100,000 live births.

Numerous factors contribute to these disparities. Among those listed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ chief executive officer Maureen G. Phipps, MD, in a press statement on the NCHS data, are care access issues, lack of standardization of care, bias, and racism. All of these must be addressed if the disparities in maternal and other areas of care are to be eliminated, according to Dr. Phipps.

“The NCHS data confirmed what we have known from other data sources: The rate of maternal deaths for non-Hispanic black women is substantially higher than the rates for non-Hispanic white women,” she wrote. “Continued efforts to improve the standardization of data and review processes related to U.S. maternal mortality are a necessary step to achieving the goal of eliminating disparities and preventable maternal mortality.”

However, such efforts frequently encounter roadblocks constructed by the reluctance among “many academics, policy makers, scientists, elected officials, journalists, and others responsible for defining and responding to the public discourse” to identify racism as a root cause of health disparities, according to Zinzi D. Bailey, ScD, former director of research and evaluation for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and colleagues.

In the third of a three-part conceptual report in The Lancet, entitled America: Equity and Equality in Health, Dr. Bailey and colleagues argued that advancing health equity requires a focus on structural racism – which they defined as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination via mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (e.g., in housing, education, employment, earning, benefits, credit, media, healthcare, and criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.”

In their series, the authors peeled back layer upon layer of sociological and political contributors to structural racism throughout history, revealing how each laid a foundation for health inequity over time. They particularly home in on health care quality and access.

“Interpersonal racism, bias, and discrimination in healthcare settings can directly affect health through poor health care,” they wrote, noting that “almost 15 years ago, the Institute of Medicine report entitled Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, documented systematic and pervasive bias in the treatment of people of color resulting in substandard care.”

That report concluded that “bias, stereotyping, prejudice, and clinical uncertainty on the part of healthcare providers” likely play a role in the continuation of health disparities. More recent data – including the NCHS maternal mortality data – show an ongoing crisis.

A study of 210 experienced primary care providers and 190 community members in the Denver area, for example, found substantial evidence of implicit bias against both Latino and African American patients. The authors defined implicit bias as “unintentional and even unconscious” negative evaluation of one group and its members relative to another that is expressed implicitly, such as through negative nonverbal behavior.

“Activated by situational cues (e.g., a person’s skin color), implicit bias can quickly and unknowingly exert its influence on perception, memory, and behavior,” they wrote.

In their study, Implicit Association Test and self-report measures of bias showed similar rates of implicit bias among the providers and community members, with only a slight weakening of ethnic/racial bias among providers after adjustment for background characteristics, which suggests “a wider societal problem,” they said.

A specific example of how implicit bias can manifest was described in a 2016 report addressing the well-documented under-treatment of pain among black versus white patients. Kelly M. Hoffman, PhD, and colleagues demonstrated that a substantial number of individuals with at least some medical training endorse false beliefs regarding biological differences between black and white patients. For example, 25% of 28 white residents surveyed agreed black individuals have thicker skin, and 4% believed black individuals have faster blood coagulation and less sensitivity in their nerve endings.

Those who more strongly endorsed such erroneous beliefs were more likely to underestimate and undertreat pain among black patients, the authors found.

Another study, which underscored the insidiousness of structural racism, was reported in Science. The authors identified significant racial bias in an algorithm widely used by health systems, insurers, and practitioners to allocate health care resources for patients with complex health needs. The algorithm, which affects millions of patients, uses predictions of future health care costs rather than future illness to determine who should receive extra medical care.

The problem is that unequal care access for black patients skews lower the foundational cost data used for making those predictions. Correcting the algorithm would increase the percentage of black patients receiving additional medical help from 17.7% to 46.5%, the authors concluded.

This evidence of persistent racism and bias in medicine, however, doesn’t mean progress is lacking.

ACOG has partnered with numerous other organizations to promote awareness and change, including through legislation. A recent win was the enactment of the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, a bipartisan bill designed to promote and support maternal mortality review committees in every state. A major focus of BMMA’s Black Maternal Health Week was the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2020, a nine-bill package introduced in March to comprehensively address the crisis.

But efforts like these, whether they aim to elucidate the contributors to health disparities or to directly target structural and overt racism and root out implicit bias in medical care, are nothing new. As Dr. Bailey and colleagues noted, a challenge is getting the message across because efforts to avoid tough conversations around these topics are nothing new, either.

Dr. Gee attested to that during a maternal mortality panel discussion at the 2019 ACOG meeting where she spoke about the resistance she encountered in 2016 when she was appointed secretary of the Louisiana Health Department and worked to make racism and bias a foundational part of the discussion on improving maternal and fetal outcomes.

She established the first Office of Health Equity in the state – and the first in the nation to not only require measurement outcomes by race but also explicitly address racial bias at the outset. The goal wasn’t just to talk about it but to “plan for addressing equity in every single aspect of what we do with ... our case equity action teams.”

“At our first maternal mortality quality meetings we insisted on focusing on equity at the very outset, and we had people that left when we started talking about racism,” she said, noting that others said it was “too political” to discuss during an election year or that equity was something to address later.

“We said no. We insisted on it, and I think that was very important because all ships don’t rise with the tide, not with health disparities,” she said, recounting an earlier experience when she led the Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative: “I asked to have a brown-bag focused on racism at the department so we could talk about the impact of implicit bias on decision making, and I was told that I was a Yankee who didn’t understand the South and that racism didn’t really exist here, and what did I know about it – and I couldn’t have the brown-bag.”

That was in 2011.

Fast-forward to April 24, 2020. As Dr. Gee shared her perspective on addressing racism and bias in medicine, she was preparing for a call regarding the racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes – the first health equity action sanctioned by Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards (D).

“I think we really set the stage for these discussions,” she said.

Addressing equity to enact change

The efforts in Louisiana also set the stage for better maternal outcomes. At the 2019 ACOG meeting where she spoke as part of the President’s Panel, Dr. Gee said Louisiana had the highest maternal mortality rates in the nation. The NCHC data released in January, however, suggest that may no longer be the case.

Inconsistencies in how the latest and prior data were reported, including in how maternal mortality was defined, make direct comparison impossible. But in the latest report, Louisiana ranked seventh among states with available data.

“Ninety percent of the deliveries in the state happen at hospitals that we worked with,” Dr. Gee said, highlighting the reach of the efforts to improve outcomes there.

She also described a recent case involving an anemic patient whose bleeding risk was identified early thanks to the programs put in place. That enabled early preparation in the event of complications.

The patient experienced a massive hemorrhage, but the preparation, including having units of blood on hand in case of such an emergency, saved her life.

“So we clearly have not just data, but individual stories of people whose lives have been saved by this work,” she said.

More tangible data on maternal morbidity further show that the efforts in the state are making a difference, Dr. Gillispie said, citing preliminary outcomes data from the Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review launched in 2018.

“We started with an initial goal of reducing severe maternal morbidity related to hypertension and hemorrhage by 20%, as well as reducing the black/white disparity gap by Mother’s Day 2020,” she said.

Final analyses have been delayed because of COVID-19, but early assessments showed a reduction in the disparity gap, she said, again highlighting the importance of focusing on equity.

“Definitely from the standpoint of the Quality Collaborative side ... we’ve been working with our facilities to make them aware of what implicit bias is, helping them to also do the Harvard Implicit Bias Test so they can figure out what their own biases are, start working to acknowledge them and address them, and start working to fight against letting that bias change how they treat individuals,” Dr. Gillispie said.

The work started through these initiatives will continue because there is much left to be done, she said.

Indeed, the surprised reactions in recent weeks to the reports of disparities in COVID-19 outcomes further underscore that reality, and the maternal mortality statistics – with use of the voices of those directly affected by structural and overt racism and bias in maternal care as a megaphone – speak for themselves.

Hearing implicit bias from patients’ perspective

Just ask Timoria McQueen Saba, a black woman who nearly died from a postpartum hemorrhage in 2010. At ACOG 2019, she spoke about how she had to switch ob.gyns. three times during her first pregnancy because she felt she had not received quality care – one doctor neglected to tell her she had placenta previa. She also experienced excessive wait times at prenatal appointments and had been on the receiving end of microaggressions and degrading questions such as “Are you still married?” and “Is your husband your baby’s father?” – and these are all things her white friends who recommended those physicians never experienced, she said.

“The health care system has just sometimes beaten people down so much, just like the world has – people of color, especially – to where you’re dismissed, your concerns are invalidated,” she said. “Some doctors don’t even think black people feel pain [or that] our pain is less.”

Mrs. Saba also spoke about how her health care “improved a billion percent” when her white husband accompanied her to appointments.

Just ask Charles S. Johnson IV, whose wife Kira Dixon Johnson died in 2016 during surgery for postpartum bleeding complications – after he and other family members spent 10 hours pleading for help for her.

Speaking at the ACOG panel discussion with Mrs. Saba, Mr. Johnson described “a clear disconnect” between the medical staff at the hospital and the way they viewed and valued Kira. He shared his frustration in wanting to advocate for his wife, but knowing that, as an African American male, he risked being seen as a threat and removed from the hospital if he didn’t stay calm, if he “tapped into those natural instincts as a man and a husband who wants to just protect his family.”

He fought back emotions, struggling to get the words out, saying that’s what haunts him and keeps him up at night – wondering if he should have “fought harder, grabbed the doctor by the collar, raised his voice, slammed on the counter.

“Maybe they would have done something,” he said.

Such experiences cross all socioeconomic boundaries. Ask U.S. Track and Field Olympic gold medalist Allyson Felix, who testified at a U.S. House Ways and Means Committee hearing on May 16, 2019 after developing severe preeclampsia that threatened her life and that of her baby. Ask tennis champion Serena Williams, who demanded assessment for pulmonary embolism following the birth of her child; she knew the signs, but her health care providers initially dismissed her concerns.

Their experiences aren’t just anecdotal. Data consistently show how racism and bias affect patient treatment and outcomes. Dr. Gee, for example, shared findings from a retrospective assessment of 47 confirmed pregnancy-related deaths in Louisiana between 2011 and 2016 that looked specifically at whether the deaths could potentially have been prevented if blood was given sooner, cardiomyopathy was recognized sooner, hypertension was treated on time, or other changes were made to care.

The answer was “Yes” in 9% of cases involving white patients – and in 59% of cases involving black patients (odds ratio, 14.6).

The study, reported in February in Obstetrics & Gynecology, showed that 27 of the deaths (58%) occurred at level III or IV birth facilities and that those deaths were not less likely than those at level I or II facilities to be categorized as preventable (OR, 2.0).

Findings from the Giving Voice to Mothers study, published in Reproductive Health in 2019, showed how mistreatment during childbirth might contribute to such outcomes.

In an online cross-sectional survey of more than 2,100 U.S. women, one in six reported at least one type of mistreatment, such as loss of autonomy, being yelled at or threatened, being ignored or having requests for help ignored, Saraswathi Vedam, SciD, of the Birth Place Lab at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and colleagues reported.

Race was among the factors associated with likelihood of mistreatment, and the rates of mistreatment for women of color were consistently higher – even when looking at interactions between race and other characteristics, such as socioeconomic status (SES). For example, 27.2% of women of color with low SES, compared with 18.7% of white women with low SES, reported mistreatment. Having a partner who was black, regardless of maternal race, was also associated with an increased rate of mistreatment, the authors found.

“I often get the question, ‘Do you think Kira would be alive if she was white,’ ” Mr. Johnson said. “The first way I respond to that question is [by saying that] the simple fact that you have to ask me is a problem.

“When this first happened, I was in so much pain that I couldn’t process the fact that something so egregious and outrageous happened to my wife because of the color of her skin, but as I began to process and really think about it and unpack this scenario, I have to be really frank ... do I think that she would have sat there for 10 hours while we begged and pleaded? Absolutely not.”

He stressed that his words aren’t “an indictment of the profession.”

“This is not an indictment saying that all people are racist or prejudiced,” he said. “But here’s the reality: If you are in this profession, if you are responsible for the well-being of patients and their families, and you are not able to see them in the same way that you see your mother, your wife, your sister, you have two options – you need to find something else to do or you need to take steps to get better.”

Fixing systems, finding solutions

Dr. Gee acknowledged the work that physicians need to do to help improve outcomes.

“The average time we give a patient to talk is 11 seconds before we interrupt them,” she said, as one example. “We have to recognize that.”

But efforts to improve outcomes shouldn’t just focus on changing physician behavior, she said.

“We really need to focus, as has the U.K. – very effectively – on using midwives, doulas, other health care professionals as complements to physicians to make sure that we have women-centered birth experiences.

“So, instead of just blaming the doctors, I think we need to change the system,” Dr. Gee emphasized.

The disruptions in health systems caused by COVID-19 present a unique opportunity to do that, she said. There is now an opportunity to build them back.

“We have a chance to build the systems back, and when we do so, we ought to build them back correcting for implicit bias and some of the systemic issues that lead to poor outcomes for people of color in our country,” she said.

Solutions proposed by Dr. Gee and others include more diversity in the workforce, more inclusion of patient advocates in maternal care, development of culturally appropriate literacy and numeracy communications, measurement by race (and action on the outcomes), standardization of care, and development of new ways to improve care access.

We will focus more specifically on these solutions in Part 2 of this article in our maternal mortality series. Previous articles in the series are available at mdedge.com/obgyn/maternal-mortality.

April 11-17 marked the third annual national Black Maternal Health Week, an event launched in 2017 by the Atlanta-based Black Mamas Matter Alliance (BMMA), in part to “deepen the national conversation about black maternal health.”

Around the same time, emerging data showing higher mortality rates among black patients versus patients of other races with COVID-19 opened similar dialogue fraught with questions about what might explain the disturbing health disparities.

“It’s kind of surprising to me that people are shocked by these [COVID-19] disparities,” Rebekah Gee, MD, an ob.gyn. who is director of the Louisiana State University Health System in New Orleans and a driving force behind initiatives addressing racial disparities in maternal health, said in an interview. If this is it, great – and certainly every moment is a moment for learning – but these COVID-19 disparities should not be surprising to people who have been looking at data.”

Veronica Gillispie, MD, an ob.gyn. and medical director of the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative and Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review, was similarly baffled that the news was treated as a revelation.

That news includes outcomes data from New York showing that in March there were 92.3 and 74.3 deaths per 100,000 black and Hispanic COVID-19 patients, respectively, compared with 45.2 per 100,000 white patients.

“Now there’s a task force and all these initiatives to look at why this is happening, and I think those of us who work in maternal mortality are all saying, ‘We know why it’s happening,’ ” she said. “It’s the same thing we’ve been telling people why it’s been happening in maternal mortality.

“It’s implicit bias and structural racism.”

Facing hard numbers, harder conversations

The U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2018 was 17 per 100,000 live births – the highest of any similarly wealthy industrialized nation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reported in January. That’s a striking statistic in its own right. Perhaps more striking is the breakdown by race.

Hispanic women had the lowest maternal mortality rate at 12 per 100,000 live births, followed by non-Hispanic white women at 15.

The rate for non-Hispanic black women was 37 per 100,000 live births.

Numerous factors contribute to these disparities. Among those listed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ chief executive officer Maureen G. Phipps, MD, in a press statement on the NCHS data, are care access issues, lack of standardization of care, bias, and racism. All of these must be addressed if the disparities in maternal and other areas of care are to be eliminated, according to Dr. Phipps.

“The NCHS data confirmed what we have known from other data sources: The rate of maternal deaths for non-Hispanic black women is substantially higher than the rates for non-Hispanic white women,” she wrote. “Continued efforts to improve the standardization of data and review processes related to U.S. maternal mortality are a necessary step to achieving the goal of eliminating disparities and preventable maternal mortality.”

However, such efforts frequently encounter roadblocks constructed by the reluctance among “many academics, policy makers, scientists, elected officials, journalists, and others responsible for defining and responding to the public discourse” to identify racism as a root cause of health disparities, according to Zinzi D. Bailey, ScD, former director of research and evaluation for the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and colleagues.

In the third of a three-part conceptual report in The Lancet, entitled America: Equity and Equality in Health, Dr. Bailey and colleagues argued that advancing health equity requires a focus on structural racism – which they defined as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination via mutually reinforcing inequitable systems (e.g., in housing, education, employment, earning, benefits, credit, media, healthcare, and criminal justice, etc.) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.”

In their series, the authors peeled back layer upon layer of sociological and political contributors to structural racism throughout history, revealing how each laid a foundation for health inequity over time. They particularly home in on health care quality and access.

“Interpersonal racism, bias, and discrimination in healthcare settings can directly affect health through poor health care,” they wrote, noting that “almost 15 years ago, the Institute of Medicine report entitled Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, documented systematic and pervasive bias in the treatment of people of color resulting in substandard care.”

That report concluded that “bias, stereotyping, prejudice, and clinical uncertainty on the part of healthcare providers” likely play a role in the continuation of health disparities. More recent data – including the NCHS maternal mortality data – show an ongoing crisis.

A study of 210 experienced primary care providers and 190 community members in the Denver area, for example, found substantial evidence of implicit bias against both Latino and African American patients. The authors defined implicit bias as “unintentional and even unconscious” negative evaluation of one group and its members relative to another that is expressed implicitly, such as through negative nonverbal behavior.

“Activated by situational cues (e.g., a person’s skin color), implicit bias can quickly and unknowingly exert its influence on perception, memory, and behavior,” they wrote.

In their study, Implicit Association Test and self-report measures of bias showed similar rates of implicit bias among the providers and community members, with only a slight weakening of ethnic/racial bias among providers after adjustment for background characteristics, which suggests “a wider societal problem,” they said.

A specific example of how implicit bias can manifest was described in a 2016 report addressing the well-documented under-treatment of pain among black versus white patients. Kelly M. Hoffman, PhD, and colleagues demonstrated that a substantial number of individuals with at least some medical training endorse false beliefs regarding biological differences between black and white patients. For example, 25% of 28 white residents surveyed agreed black individuals have thicker skin, and 4% believed black individuals have faster blood coagulation and less sensitivity in their nerve endings.

Those who more strongly endorsed such erroneous beliefs were more likely to underestimate and undertreat pain among black patients, the authors found.

Another study, which underscored the insidiousness of structural racism, was reported in Science. The authors identified significant racial bias in an algorithm widely used by health systems, insurers, and practitioners to allocate health care resources for patients with complex health needs. The algorithm, which affects millions of patients, uses predictions of future health care costs rather than future illness to determine who should receive extra medical care.

The problem is that unequal care access for black patients skews lower the foundational cost data used for making those predictions. Correcting the algorithm would increase the percentage of black patients receiving additional medical help from 17.7% to 46.5%, the authors concluded.

This evidence of persistent racism and bias in medicine, however, doesn’t mean progress is lacking.

ACOG has partnered with numerous other organizations to promote awareness and change, including through legislation. A recent win was the enactment of the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, a bipartisan bill designed to promote and support maternal mortality review committees in every state. A major focus of BMMA’s Black Maternal Health Week was the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2020, a nine-bill package introduced in March to comprehensively address the crisis.

But efforts like these, whether they aim to elucidate the contributors to health disparities or to directly target structural and overt racism and root out implicit bias in medical care, are nothing new. As Dr. Bailey and colleagues noted, a challenge is getting the message across because efforts to avoid tough conversations around these topics are nothing new, either.

Dr. Gee attested to that during a maternal mortality panel discussion at the 2019 ACOG meeting where she spoke about the resistance she encountered in 2016 when she was appointed secretary of the Louisiana Health Department and worked to make racism and bias a foundational part of the discussion on improving maternal and fetal outcomes.

She established the first Office of Health Equity in the state – and the first in the nation to not only require measurement outcomes by race but also explicitly address racial bias at the outset. The goal wasn’t just to talk about it but to “plan for addressing equity in every single aspect of what we do with ... our case equity action teams.”

“At our first maternal mortality quality meetings we insisted on focusing on equity at the very outset, and we had people that left when we started talking about racism,” she said, noting that others said it was “too political” to discuss during an election year or that equity was something to address later.

“We said no. We insisted on it, and I think that was very important because all ships don’t rise with the tide, not with health disparities,” she said, recounting an earlier experience when she led the Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative: “I asked to have a brown-bag focused on racism at the department so we could talk about the impact of implicit bias on decision making, and I was told that I was a Yankee who didn’t understand the South and that racism didn’t really exist here, and what did I know about it – and I couldn’t have the brown-bag.”

That was in 2011.

Fast-forward to April 24, 2020. As Dr. Gee shared her perspective on addressing racism and bias in medicine, she was preparing for a call regarding the racial disparities in COVID-19 outcomes – the first health equity action sanctioned by Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards (D).

“I think we really set the stage for these discussions,” she said.

Addressing equity to enact change