User login

Melanoma in US Hispanics: Recommended Strategies to Reduce Disparities in Outcomes

Cutaneous melanoma is a considerable public health concern. In the United States, an estimated 87,110 cases were diagnosed in 2017, and more than 9000 deaths are expected as result of this disease in 2018.1 Early diagnosis of melanoma is associated with favorable survival rates (5-year overall survival rates for melanoma in situ and stage IA melanoma, 99% and 97%, respectively).2 In contrast, the prognosis for advanced-stage melanoma is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 16% for patients with stage IV disease. Therefore, early detection is critical to reducing mortality in melanoma patients.3

The term Hispanic refers to a panethnic category primarily encompassing Mexican-Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans, as well as individuals from the Caribbean and Central and South America. These populations are diverse in birth origin, primary language, acculturation, distinct ethnic traditions, education level, and occupation. Hispanics in the United States are heterogeneous in many dimensions related to health risks, health care use, and health outcomes.4 Genetic predisposition, lifestyle risks, and access to and use of health care services can shape melanoma diagnosis, treatment, and progression across Hispanic populations differently than in other populations.

In this review, the epidemiology and clinical presentation of melanoma in US Hispanics is summarized, and recommendations for a research agenda to advance understanding of this disease in the most rapidly growing segment of the US population is provided.

In the period from 2008 to 2012, the age-adjusted incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics (4.6 per 100,00 men and 4.2 per 100,00 women) was lower than in NHWs.5 Garnett et al5 reported a decline in melanoma incidence in US Hispanics between 2003 and 2012—an observation that stands in contrast to state-level studies in California and Florida, in which small but substantial increases in melanoma incidence among Hispanics were reported.6,7 The rising incidence of melanomas thicker than 1.5 mm at presentation among Hispanic men living in California is particularly worrisome.6 Discrepancies in incidence trends might reflect changes in incidence over time or differences in state-level registry reporting of melanoma.5

Despite a lower overall incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics, those who do develop the disease are 2.4 times more likely (age-adjusted odds ratio) to present with stage III disease (confidence interval, 1.89-3.05)8 and are 3.64 times more likely to develop distant metastases (confidence interval, 2.65-5.0) than NHWs.3,7,9-13 Disparities also exist in the diagnosis of childhood melanoma: Hispanic children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of melanoma are 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than NHW counterparts.14 Survival analyses by age and stage show considerably lower survival among Hispanic patients compared to NHW patients with stage I and II disease. In part, worse survival outcomes among Hispanics are the result of the pattern of more advanced disease at presentation.8,14,15

Late presentation for evaluation of melanomas in Hispanics has been attributed to a number of variables, including a lack of skin cancer awareness and knowledge,9,16 a lower rate of self- and physician-performed skin examinations,10 differences in tumor biology,9 and socioeconomic forces.7,17

In a previous study investigating the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis in Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, several key findings emerged.17 First, residency in a census tract with a high density of immigrants (California, Texas) and a high composition of Hispanics (California, Florida) was an important predictor of a late-stage melanoma diagnosis in fully adjusted models. Additionally, the strength of association between measures of socioeconomic status (ie, poverty and education) and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis was attenuated in multivariate models when enclaves and availability of primary care resources were taken into account. Hispanic melanoma cases in areas with a low density of primary care physicians had an increased likelihood of late-stage diagnosis in California and Texas. The probability of late-stage diagnosis was concentrated in specific regions along the United States–Mexico border, in south central California, and along the southeastern coast of Florida. Lastly, in Texas, Hispanic men aged 18 to 34 years and 35 to 49 years were at an increased risk of late-stage melanoma diagnosis compared to men 65 years and older.17

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Melanoma in Hispanic Patients

Among Hispanics, white Hispanics comprise the majority of melanoma cases.5 Median age at diagnosis is younger in Hispanics compared to whites.5,6 Hispanic men typically are older (median age, 61 years) than Hispanic women (median age, 52 years) at diagnosis.5 Similar to what is seen in NHWs, young Hispanic women experience a higher melanoma incidence than young Hispanic men.5 Among older Hispanics, melanoma is more common in men.5,8

Melanomas located on the lower extremities and hips are more prevalent in Hispanics than in NHWs.5,8,18 Among Hispanics, there are age- and sex-based variations in the anatomic location of primary tumors: in Hispanic men, truncal tumors predominate, and in Hispanic women, tumors of the lower extremities are most common across all age groups.5 The incidence of melanomas located in the head and neck region increases with age for both Hispanic men and women.

For melanomas in which the histologic type is known, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common subtype among Hispanics.5,17,19 Acral lentiginous melanomas and nodular melanomas are more common among Hispanics than among NHWs.5,17,19

The observation that Hispanics with melanoma are more prone to lower-extremity tumors and nodular and acral lentiginous melanoma subtypes than NHWs suggests that UV exposure history may be of less importance in this population. Although numerous studies have explored melanoma risk factors in NHWs, there is a striking paucity of such studies in Hispanics. For example, there are conflicting data regarding the role of UV exposure in melanoma risk among Hispanics. Hu et al20 found that UV index and latitude correlated with melanoma risk in this population, whereas Eide et al21 found no association between UV exposure and melanoma incidence in Hispanics. A prospective study involving a multiethnic cohort (of whom 40 of the 107 participants were Hispanic) found no clear association between a history of sunburn and melanoma risk in Hispanics.18

Strategies for Reducing Disparities in Outcomes

Our knowledge of melanoma epidemiology in Hispanics derives mainly from secondary analyses of state-level and national cancer registry data sets.5-8,13-15,17,19,20 These administrative data sources often are limited by missing data (eg, tumor thickness, histologic subtype) or lack important patient-level information (eg, self-identified race and ethnicity, health insurance status). Additionally, the manner in which data are collected and integrated into research varies; for example, socioeconomic measures often are reported as either area-based or composite measures.

The host phenotypic characteristics of melanoma in NHWs are well understood, but the biological and environmental determinants of melanoma risk in Hispanics and other minorities are unknown. For example, fair complexion, red hair, blue eyes, increased freckling density, and the presence of numerous dysplastic and common melanocytic nevi indicate a propensity toward cutaneous melanoma.23,24 However, the relevance of such risk factors in Hispanics is unknown and has not been widely investigated in this patient population. Park et al18 found that a person’s sunburn susceptibility phenotype (defined as hair and eye color, ability to tan, and skin reaction to sunlight) was associated with an increased risk of melanoma among nonwhite, multiracial individuals. However, this study was limited by a small number of minority cases, which included only 40 Hispanic participants with melanoma.18 There is a need for rigorous observational studies to clearly define the phenotypic characteristics, sun-exposure behavior patterns, and genetic contributors to melanoma genesis in Hispanics.

The biologic determinants of postdiagnosis survival in Hispanics with melanoma are not well understood. It is unknown if genetic predisposition modifies melanoma risk in Hispanics. For example, the frequency of BRAF gene mutation or other driver mutations in US Hispanics has been understudied. It is important to know if mutation frequency patterns differ in Hispanics patients compared to NHWs because this knowledge could have considerable implications for treatment. Several recommendations should be considered to address these knowledge gaps. First, there is a need for development or enhancement of melanoma biorepositories, which should include tumor and nontumor specimens from a diverse sample of melanoma patients.

Conclusion

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 13, 2018.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

- Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives? Cancer. 2012;118:5395-5402.

- Bergad LW, Klein HS. Hispanics in the United States: A Demographic, Social, and Economic History, 1980-2005. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Swetter SM, et al. The expanding melanoma burden in California Hispanics: importance of socioeconomic distribution, histologic subtype, and anatomic location. Cancer. 2011;117:152-161.

- Hu S, Parmet, Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites,Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. JAMA Dermatology. 2010;145:1369-1374.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Pollitt RA, Swetter SM, Johnson TM, et al. Examining the pathways linking lower socioeconomic status and advanced melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4004-4013.

- Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA163-RA172.

- Singh SD, Ajani UA, Johnson CJ, et al. Association of cutaneous melanoma incidence with area-based socioeconomic indicators-United States, 2004-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S58-S68.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, et al. California Medicaid enrollment and melanoma stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:7-13.

- Clairwood M, Ricketts J, Grant-Kels J, et al. Melanoma in skin of color in Connecticut: an analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis in non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:425-433.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Harvey VM, Enos CW, Chen JT, et al. The role of neighborhood characteristics in late stage melanoma diagnosis among Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, 1996-2012 [published online June 18, 2017]. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;2017:8418904.

- Park SL, Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, et al. Risk factors for malignant melanoma in white and non-white/non-African American populations: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:423-434.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37.

- Hu S, Ma F, Collado-Mesa F, et al. UV radiation, latitude, and melanoma in US Hispanics and blacks. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:819-824.

- Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Association of UV index, latitude, and melanoma incidence in nonwhite populations—US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, 1992 to 2001. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:477-481.

- Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, et al. Charting the future of cancer health disparities research: a position statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4548-4555.

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2040-2059.

- Chang YM, Newton-Bishop JA, Bishop DT, et al. A pooled analysis of melanocytic nevus phenotype and the risk of cutaneous melanoma at different latitudes. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:420-428.

- Palmer JR, Ambrosone CB, Olshan AF. A collaborative study of the etiology of breast cancer subtypes in African American women: the AMBER consortium. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:309-319.

- Rapkin BD, Weiss E, Lounsbury D, et al. Reducing disparities in cancer screening and prevention through community-based participatory research partnerships with local libraries: a comprehensive dynamic trial. Am J Community Psychol. 2017;60:145-159.

Cutaneous melanoma is a considerable public health concern. In the United States, an estimated 87,110 cases were diagnosed in 2017, and more than 9000 deaths are expected as result of this disease in 2018.1 Early diagnosis of melanoma is associated with favorable survival rates (5-year overall survival rates for melanoma in situ and stage IA melanoma, 99% and 97%, respectively).2 In contrast, the prognosis for advanced-stage melanoma is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 16% for patients with stage IV disease. Therefore, early detection is critical to reducing mortality in melanoma patients.3

The term Hispanic refers to a panethnic category primarily encompassing Mexican-Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans, as well as individuals from the Caribbean and Central and South America. These populations are diverse in birth origin, primary language, acculturation, distinct ethnic traditions, education level, and occupation. Hispanics in the United States are heterogeneous in many dimensions related to health risks, health care use, and health outcomes.4 Genetic predisposition, lifestyle risks, and access to and use of health care services can shape melanoma diagnosis, treatment, and progression across Hispanic populations differently than in other populations.

In this review, the epidemiology and clinical presentation of melanoma in US Hispanics is summarized, and recommendations for a research agenda to advance understanding of this disease in the most rapidly growing segment of the US population is provided.

In the period from 2008 to 2012, the age-adjusted incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics (4.6 per 100,00 men and 4.2 per 100,00 women) was lower than in NHWs.5 Garnett et al5 reported a decline in melanoma incidence in US Hispanics between 2003 and 2012—an observation that stands in contrast to state-level studies in California and Florida, in which small but substantial increases in melanoma incidence among Hispanics were reported.6,7 The rising incidence of melanomas thicker than 1.5 mm at presentation among Hispanic men living in California is particularly worrisome.6 Discrepancies in incidence trends might reflect changes in incidence over time or differences in state-level registry reporting of melanoma.5

Despite a lower overall incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics, those who do develop the disease are 2.4 times more likely (age-adjusted odds ratio) to present with stage III disease (confidence interval, 1.89-3.05)8 and are 3.64 times more likely to develop distant metastases (confidence interval, 2.65-5.0) than NHWs.3,7,9-13 Disparities also exist in the diagnosis of childhood melanoma: Hispanic children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of melanoma are 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than NHW counterparts.14 Survival analyses by age and stage show considerably lower survival among Hispanic patients compared to NHW patients with stage I and II disease. In part, worse survival outcomes among Hispanics are the result of the pattern of more advanced disease at presentation.8,14,15

Late presentation for evaluation of melanomas in Hispanics has been attributed to a number of variables, including a lack of skin cancer awareness and knowledge,9,16 a lower rate of self- and physician-performed skin examinations,10 differences in tumor biology,9 and socioeconomic forces.7,17

In a previous study investigating the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis in Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, several key findings emerged.17 First, residency in a census tract with a high density of immigrants (California, Texas) and a high composition of Hispanics (California, Florida) was an important predictor of a late-stage melanoma diagnosis in fully adjusted models. Additionally, the strength of association between measures of socioeconomic status (ie, poverty and education) and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis was attenuated in multivariate models when enclaves and availability of primary care resources were taken into account. Hispanic melanoma cases in areas with a low density of primary care physicians had an increased likelihood of late-stage diagnosis in California and Texas. The probability of late-stage diagnosis was concentrated in specific regions along the United States–Mexico border, in south central California, and along the southeastern coast of Florida. Lastly, in Texas, Hispanic men aged 18 to 34 years and 35 to 49 years were at an increased risk of late-stage melanoma diagnosis compared to men 65 years and older.17

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Melanoma in Hispanic Patients

Among Hispanics, white Hispanics comprise the majority of melanoma cases.5 Median age at diagnosis is younger in Hispanics compared to whites.5,6 Hispanic men typically are older (median age, 61 years) than Hispanic women (median age, 52 years) at diagnosis.5 Similar to what is seen in NHWs, young Hispanic women experience a higher melanoma incidence than young Hispanic men.5 Among older Hispanics, melanoma is more common in men.5,8

Melanomas located on the lower extremities and hips are more prevalent in Hispanics than in NHWs.5,8,18 Among Hispanics, there are age- and sex-based variations in the anatomic location of primary tumors: in Hispanic men, truncal tumors predominate, and in Hispanic women, tumors of the lower extremities are most common across all age groups.5 The incidence of melanomas located in the head and neck region increases with age for both Hispanic men and women.

For melanomas in which the histologic type is known, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common subtype among Hispanics.5,17,19 Acral lentiginous melanomas and nodular melanomas are more common among Hispanics than among NHWs.5,17,19

The observation that Hispanics with melanoma are more prone to lower-extremity tumors and nodular and acral lentiginous melanoma subtypes than NHWs suggests that UV exposure history may be of less importance in this population. Although numerous studies have explored melanoma risk factors in NHWs, there is a striking paucity of such studies in Hispanics. For example, there are conflicting data regarding the role of UV exposure in melanoma risk among Hispanics. Hu et al20 found that UV index and latitude correlated with melanoma risk in this population, whereas Eide et al21 found no association between UV exposure and melanoma incidence in Hispanics. A prospective study involving a multiethnic cohort (of whom 40 of the 107 participants were Hispanic) found no clear association between a history of sunburn and melanoma risk in Hispanics.18

Strategies for Reducing Disparities in Outcomes

Our knowledge of melanoma epidemiology in Hispanics derives mainly from secondary analyses of state-level and national cancer registry data sets.5-8,13-15,17,19,20 These administrative data sources often are limited by missing data (eg, tumor thickness, histologic subtype) or lack important patient-level information (eg, self-identified race and ethnicity, health insurance status). Additionally, the manner in which data are collected and integrated into research varies; for example, socioeconomic measures often are reported as either area-based or composite measures.

The host phenotypic characteristics of melanoma in NHWs are well understood, but the biological and environmental determinants of melanoma risk in Hispanics and other minorities are unknown. For example, fair complexion, red hair, blue eyes, increased freckling density, and the presence of numerous dysplastic and common melanocytic nevi indicate a propensity toward cutaneous melanoma.23,24 However, the relevance of such risk factors in Hispanics is unknown and has not been widely investigated in this patient population. Park et al18 found that a person’s sunburn susceptibility phenotype (defined as hair and eye color, ability to tan, and skin reaction to sunlight) was associated with an increased risk of melanoma among nonwhite, multiracial individuals. However, this study was limited by a small number of minority cases, which included only 40 Hispanic participants with melanoma.18 There is a need for rigorous observational studies to clearly define the phenotypic characteristics, sun-exposure behavior patterns, and genetic contributors to melanoma genesis in Hispanics.

The biologic determinants of postdiagnosis survival in Hispanics with melanoma are not well understood. It is unknown if genetic predisposition modifies melanoma risk in Hispanics. For example, the frequency of BRAF gene mutation or other driver mutations in US Hispanics has been understudied. It is important to know if mutation frequency patterns differ in Hispanics patients compared to NHWs because this knowledge could have considerable implications for treatment. Several recommendations should be considered to address these knowledge gaps. First, there is a need for development or enhancement of melanoma biorepositories, which should include tumor and nontumor specimens from a diverse sample of melanoma patients.

Conclusion

Cutaneous melanoma is a considerable public health concern. In the United States, an estimated 87,110 cases were diagnosed in 2017, and more than 9000 deaths are expected as result of this disease in 2018.1 Early diagnosis of melanoma is associated with favorable survival rates (5-year overall survival rates for melanoma in situ and stage IA melanoma, 99% and 97%, respectively).2 In contrast, the prognosis for advanced-stage melanoma is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 16% for patients with stage IV disease. Therefore, early detection is critical to reducing mortality in melanoma patients.3

The term Hispanic refers to a panethnic category primarily encompassing Mexican-Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans, as well as individuals from the Caribbean and Central and South America. These populations are diverse in birth origin, primary language, acculturation, distinct ethnic traditions, education level, and occupation. Hispanics in the United States are heterogeneous in many dimensions related to health risks, health care use, and health outcomes.4 Genetic predisposition, lifestyle risks, and access to and use of health care services can shape melanoma diagnosis, treatment, and progression across Hispanic populations differently than in other populations.

In this review, the epidemiology and clinical presentation of melanoma in US Hispanics is summarized, and recommendations for a research agenda to advance understanding of this disease in the most rapidly growing segment of the US population is provided.

In the period from 2008 to 2012, the age-adjusted incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics (4.6 per 100,00 men and 4.2 per 100,00 women) was lower than in NHWs.5 Garnett et al5 reported a decline in melanoma incidence in US Hispanics between 2003 and 2012—an observation that stands in contrast to state-level studies in California and Florida, in which small but substantial increases in melanoma incidence among Hispanics were reported.6,7 The rising incidence of melanomas thicker than 1.5 mm at presentation among Hispanic men living in California is particularly worrisome.6 Discrepancies in incidence trends might reflect changes in incidence over time or differences in state-level registry reporting of melanoma.5

Despite a lower overall incidence of melanoma in US Hispanics, those who do develop the disease are 2.4 times more likely (age-adjusted odds ratio) to present with stage III disease (confidence interval, 1.89-3.05)8 and are 3.64 times more likely to develop distant metastases (confidence interval, 2.65-5.0) than NHWs.3,7,9-13 Disparities also exist in the diagnosis of childhood melanoma: Hispanic children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of melanoma are 3 times more likely to present with advanced disease than NHW counterparts.14 Survival analyses by age and stage show considerably lower survival among Hispanic patients compared to NHW patients with stage I and II disease. In part, worse survival outcomes among Hispanics are the result of the pattern of more advanced disease at presentation.8,14,15

Late presentation for evaluation of melanomas in Hispanics has been attributed to a number of variables, including a lack of skin cancer awareness and knowledge,9,16 a lower rate of self- and physician-performed skin examinations,10 differences in tumor biology,9 and socioeconomic forces.7,17

In a previous study investigating the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis in Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, several key findings emerged.17 First, residency in a census tract with a high density of immigrants (California, Texas) and a high composition of Hispanics (California, Florida) was an important predictor of a late-stage melanoma diagnosis in fully adjusted models. Additionally, the strength of association between measures of socioeconomic status (ie, poverty and education) and tumor stage at melanoma diagnosis was attenuated in multivariate models when enclaves and availability of primary care resources were taken into account. Hispanic melanoma cases in areas with a low density of primary care physicians had an increased likelihood of late-stage diagnosis in California and Texas. The probability of late-stage diagnosis was concentrated in specific regions along the United States–Mexico border, in south central California, and along the southeastern coast of Florida. Lastly, in Texas, Hispanic men aged 18 to 34 years and 35 to 49 years were at an increased risk of late-stage melanoma diagnosis compared to men 65 years and older.17

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Melanoma in Hispanic Patients

Among Hispanics, white Hispanics comprise the majority of melanoma cases.5 Median age at diagnosis is younger in Hispanics compared to whites.5,6 Hispanic men typically are older (median age, 61 years) than Hispanic women (median age, 52 years) at diagnosis.5 Similar to what is seen in NHWs, young Hispanic women experience a higher melanoma incidence than young Hispanic men.5 Among older Hispanics, melanoma is more common in men.5,8

Melanomas located on the lower extremities and hips are more prevalent in Hispanics than in NHWs.5,8,18 Among Hispanics, there are age- and sex-based variations in the anatomic location of primary tumors: in Hispanic men, truncal tumors predominate, and in Hispanic women, tumors of the lower extremities are most common across all age groups.5 The incidence of melanomas located in the head and neck region increases with age for both Hispanic men and women.

For melanomas in which the histologic type is known, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common subtype among Hispanics.5,17,19 Acral lentiginous melanomas and nodular melanomas are more common among Hispanics than among NHWs.5,17,19

The observation that Hispanics with melanoma are more prone to lower-extremity tumors and nodular and acral lentiginous melanoma subtypes than NHWs suggests that UV exposure history may be of less importance in this population. Although numerous studies have explored melanoma risk factors in NHWs, there is a striking paucity of such studies in Hispanics. For example, there are conflicting data regarding the role of UV exposure in melanoma risk among Hispanics. Hu et al20 found that UV index and latitude correlated with melanoma risk in this population, whereas Eide et al21 found no association between UV exposure and melanoma incidence in Hispanics. A prospective study involving a multiethnic cohort (of whom 40 of the 107 participants were Hispanic) found no clear association between a history of sunburn and melanoma risk in Hispanics.18

Strategies for Reducing Disparities in Outcomes

Our knowledge of melanoma epidemiology in Hispanics derives mainly from secondary analyses of state-level and national cancer registry data sets.5-8,13-15,17,19,20 These administrative data sources often are limited by missing data (eg, tumor thickness, histologic subtype) or lack important patient-level information (eg, self-identified race and ethnicity, health insurance status). Additionally, the manner in which data are collected and integrated into research varies; for example, socioeconomic measures often are reported as either area-based or composite measures.

The host phenotypic characteristics of melanoma in NHWs are well understood, but the biological and environmental determinants of melanoma risk in Hispanics and other minorities are unknown. For example, fair complexion, red hair, blue eyes, increased freckling density, and the presence of numerous dysplastic and common melanocytic nevi indicate a propensity toward cutaneous melanoma.23,24 However, the relevance of such risk factors in Hispanics is unknown and has not been widely investigated in this patient population. Park et al18 found that a person’s sunburn susceptibility phenotype (defined as hair and eye color, ability to tan, and skin reaction to sunlight) was associated with an increased risk of melanoma among nonwhite, multiracial individuals. However, this study was limited by a small number of minority cases, which included only 40 Hispanic participants with melanoma.18 There is a need for rigorous observational studies to clearly define the phenotypic characteristics, sun-exposure behavior patterns, and genetic contributors to melanoma genesis in Hispanics.

The biologic determinants of postdiagnosis survival in Hispanics with melanoma are not well understood. It is unknown if genetic predisposition modifies melanoma risk in Hispanics. For example, the frequency of BRAF gene mutation or other driver mutations in US Hispanics has been understudied. It is important to know if mutation frequency patterns differ in Hispanics patients compared to NHWs because this knowledge could have considerable implications for treatment. Several recommendations should be considered to address these knowledge gaps. First, there is a need for development or enhancement of melanoma biorepositories, which should include tumor and nontumor specimens from a diverse sample of melanoma patients.

Conclusion

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 13, 2018.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

- Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives? Cancer. 2012;118:5395-5402.

- Bergad LW, Klein HS. Hispanics in the United States: A Demographic, Social, and Economic History, 1980-2005. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Swetter SM, et al. The expanding melanoma burden in California Hispanics: importance of socioeconomic distribution, histologic subtype, and anatomic location. Cancer. 2011;117:152-161.

- Hu S, Parmet, Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites,Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. JAMA Dermatology. 2010;145:1369-1374.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Pollitt RA, Swetter SM, Johnson TM, et al. Examining the pathways linking lower socioeconomic status and advanced melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4004-4013.

- Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA163-RA172.

- Singh SD, Ajani UA, Johnson CJ, et al. Association of cutaneous melanoma incidence with area-based socioeconomic indicators-United States, 2004-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S58-S68.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, et al. California Medicaid enrollment and melanoma stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:7-13.

- Clairwood M, Ricketts J, Grant-Kels J, et al. Melanoma in skin of color in Connecticut: an analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis in non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:425-433.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Harvey VM, Enos CW, Chen JT, et al. The role of neighborhood characteristics in late stage melanoma diagnosis among Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, 1996-2012 [published online June 18, 2017]. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;2017:8418904.

- Park SL, Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, et al. Risk factors for malignant melanoma in white and non-white/non-African American populations: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:423-434.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37.

- Hu S, Ma F, Collado-Mesa F, et al. UV radiation, latitude, and melanoma in US Hispanics and blacks. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:819-824.

- Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Association of UV index, latitude, and melanoma incidence in nonwhite populations—US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, 1992 to 2001. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:477-481.

- Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, et al. Charting the future of cancer health disparities research: a position statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4548-4555.

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2040-2059.

- Chang YM, Newton-Bishop JA, Bishop DT, et al. A pooled analysis of melanocytic nevus phenotype and the risk of cutaneous melanoma at different latitudes. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:420-428.

- Palmer JR, Ambrosone CB, Olshan AF. A collaborative study of the etiology of breast cancer subtypes in African American women: the AMBER consortium. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:309-319.

- Rapkin BD, Weiss E, Lounsbury D, et al. Reducing disparities in cancer screening and prevention through community-based participatory research partnerships with local libraries: a comprehensive dynamic trial. Am J Community Psychol. 2017;60:145-159.

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed January 13, 2018.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

- Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives? Cancer. 2012;118:5395-5402.

- Bergad LW, Klein HS. Hispanics in the United States: A Demographic, Social, and Economic History, 1980-2005. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Garnett E, Townsend J, Steele B, et al. Characteristics, rates, and trends of melanoma incidence among Hispanics in the USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:647-659.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Swetter SM, et al. The expanding melanoma burden in California Hispanics: importance of socioeconomic distribution, histologic subtype, and anatomic location. Cancer. 2011;117:152-161.

- Hu S, Parmet, Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites,Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. JAMA Dermatology. 2010;145:1369-1374.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Pollitt RA, Swetter SM, Johnson TM, et al. Examining the pathways linking lower socioeconomic status and advanced melanoma. Cancer. 2012;118:4004-4013.

- Ortiz CA, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. The effect of socioeconomic factors on incidence, stage at diagnosis and survival of cutaneous melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA163-RA172.

- Singh SD, Ajani UA, Johnson CJ, et al. Association of cutaneous melanoma incidence with area-based socioeconomic indicators-United States, 2004-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S58-S68.

- Pollitt RA, Clarke CA, Shema SJ, et al. California Medicaid enrollment and melanoma stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:7-13.

- Clairwood M, Ricketts J, Grant-Kels J, et al. Melanoma in skin of color in Connecticut: an analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis in non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:425-433.

- Hamilton EC, Nguyen HT, Chang YC, et al. Health disparities influence childhood melanoma stage at diagnosis and outcome. J Pediatr. 2016;175:182-187.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991.

- Imahiyerobo-Ip J, Ip I, Jamal S, et al. Skin cancer awareness in communities of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:198-200.

- Harvey VM, Enos CW, Chen JT, et al. The role of neighborhood characteristics in late stage melanoma diagnosis among Hispanic men in California, Texas, and Florida, 1996-2012 [published online June 18, 2017]. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;2017:8418904.

- Park SL, Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, et al. Risk factors for malignant melanoma in white and non-white/non-African American populations: the multiethnic cohort. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:423-434.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37.

- Hu S, Ma F, Collado-Mesa F, et al. UV radiation, latitude, and melanoma in US Hispanics and blacks. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:819-824.

- Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Association of UV index, latitude, and melanoma incidence in nonwhite populations—US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, 1992 to 2001. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:477-481.

- Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, et al. Charting the future of cancer health disparities research: a position statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4548-4555.

- Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2040-2059.

- Chang YM, Newton-Bishop JA, Bishop DT, et al. A pooled analysis of melanocytic nevus phenotype and the risk of cutaneous melanoma at different latitudes. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:420-428.

- Palmer JR, Ambrosone CB, Olshan AF. A collaborative study of the etiology of breast cancer subtypes in African American women: the AMBER consortium. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:309-319.

- Rapkin BD, Weiss E, Lounsbury D, et al. Reducing disparities in cancer screening and prevention through community-based participatory research partnerships with local libraries: a comprehensive dynamic trial. Am J Community Psychol. 2017;60:145-159.

Practice Points

- Although the age-adjusted incidence of melanoma among US Hispanics is lower than among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics with melanoma are more likely to present with stage III disease and have distant metastases.

- Late presentation of melanoma in Hispanics is not completely understood but may be attributed to socioeconomic factors, lack of skin cancer awareness and knowledge, lower rate of self- and physician-performed skin examinations, and differences in tumor biology, among other variables.

- Research is needed to address gaps in knowledge about the risk of melanoma and comparatively poor outcomes among Hispanics so interventional efforts for prevention, early detection, and treatment can be implemented.

Factors critical to reducing US maternal mortality and morbidity

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

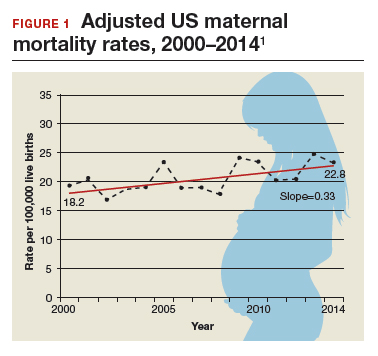

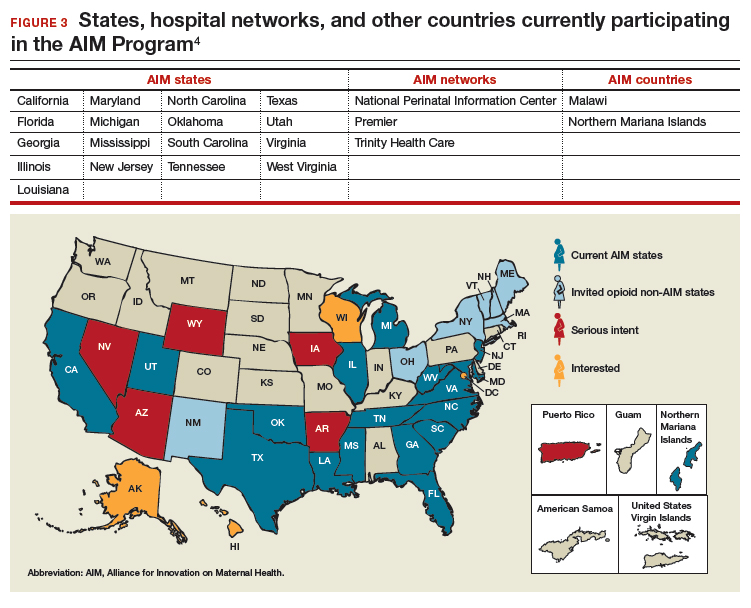

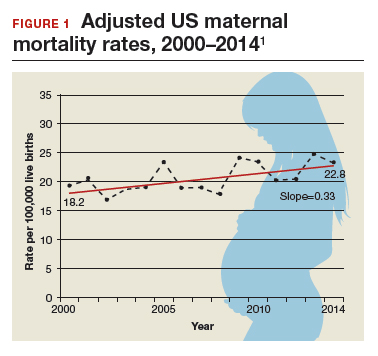

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

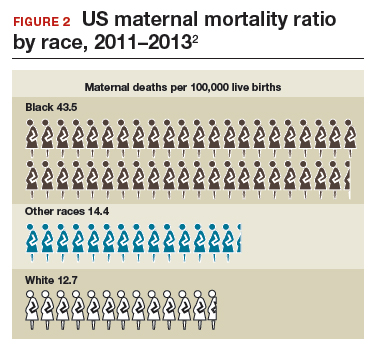

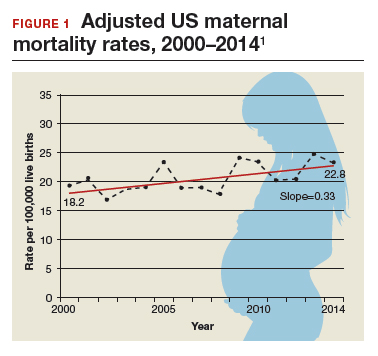

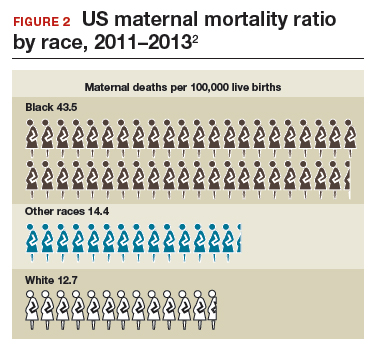

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

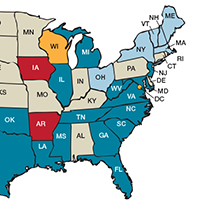

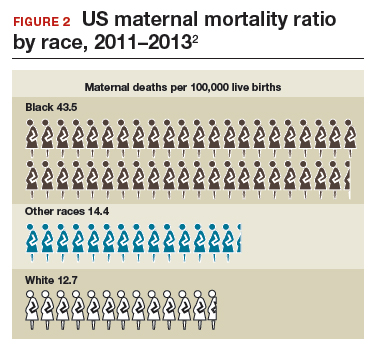

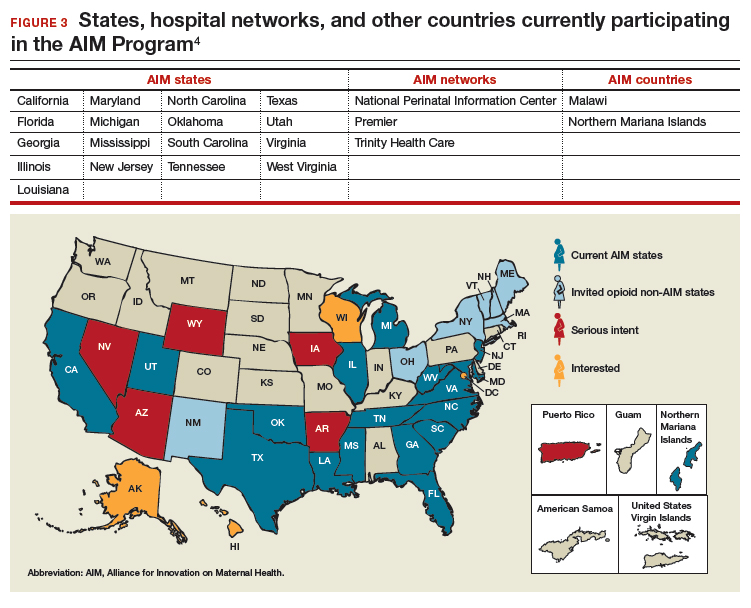

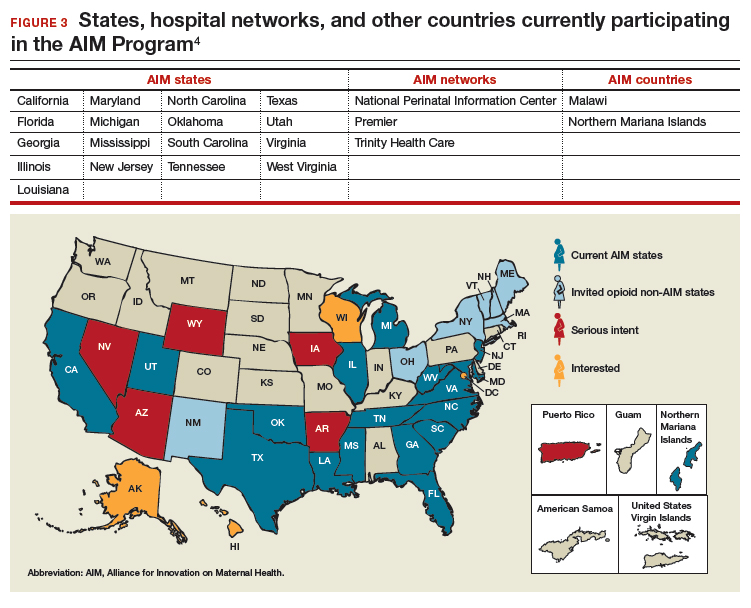

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

No Sulfates, No Parabens, and the “No-Poo” Method: A New Patient Perspective on Common Shampoo Ingredients

Shampoo is a staple in hair grooming that is ever-evolving along with cultural trends. The global shampoo market is expected to reach an estimated value of $25.73 billion by 2019. A major driver of this upward trend in market growth is the increasing demand for natural and organic hair shampoos.1 Society today has a growing fixation on healthy living practices, and as of late, the ingredients in shampoos and other cosmetic products have become one of the latest targets in the health-consciousness craze. In the age of the Internet where information—and misinformation—is widely accessible and dispersed, the general public often strives to self-educate on specialized matters that are out of their expertise. As a result, individuals have developed an aversion to using certain shampoos out of fear that the ingredients, often referred to as “chemicals” by patients due to their complex names, are unnatural and therefore unhealthy.1,2 Product developers are working to meet the demand by reformulating shampoos with labels that indicate sulfate free or paraben free, despite the lack of proof that these formulations are an improvement over traditional approaches to hair health. Additionally, alternative methods of cleansing the hair and scalp, also known as the no-shampoo or “no-poo” method, have begun to gain popularity.2,3

It is essential that dermatologists acknowledge the concerns that their patients have about common shampoo ingredients to dispel the myths that may misinform patient decision-making. This article reviews the controversy surrounding the use of sulfates and parabens in shampoos as well as commonly used shampoo alternatives. Due to the increased prevalence of dry hair shafts in the skin of color population, especially black women, this group is particularly interested in products that will minimize breakage and dryness of the hair. To that end, this population has great interest in the removal of chemical ingredients that may cause damage to the hair shafts, despite the lack of data to support sulfates and paraben damage to hair shafts or scalp skin. Blogs and uninformed hairstylists may propagate these beliefs in a group of consumers who are desperate for new approaches to hair fragility and breakage.

Surfactants and Sulfates

The cleansing ability of a shampoo depends on the surface activity of its detergents. Surface-active ingredients, or surfactants, reduce the surface tension between water and dirt, thus facilitating the removal of environmental dirt from the hair and scalp,4 which is achieved by a molecular structure containing both a hydrophilic and a lipophilic group. Sebum and dirt are bound by the lipophilic ends of the surfactant, becoming the center of a micelle structure with the hydrophilic molecule ends pointing outward. Dirt particles become water soluble and are removed from the scalp and hair shaft upon rinsing with water.4

Surfactants are classified according to the electric charge of the hydrophilic polar group as either anionic, cationic, amphoteric (zwitterionic), or nonionic.5 Each possesses different hair conditioning and cleansing qualities, and multiple surfactants are used in shampoos in differing ratios to accommodate different hair types. In most shampoos, the base consists of anionic and amphoteric surfactants. Depending on individual product requirements, nonionic and cationic surfactants are used to either modify the effects of the surfactants or as conditioning agents.4,5

One subcategory of surfactants that receives much attention is the group of anionic surfactants known as sulfates. Sulfates, particularly sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), recently have developed a negative reputation as cosmetic ingredients, as reports from various unscientific sources have labeled them as hazardous to one’s health; SLS has been described as a skin and scalp irritant, has been linked to cataract formation, and has even been wrongly labeled as carcinogenic.6 The origins of some of these claims are not clear, though they likely arose from the misinterpretation of complex scientific studies that are easily accessible to laypeople. The link between SLS and ocular irritation or cataract formation is a good illustration of this unsubstantiated fear. A study by Green et al7 showed that corneal exposure to extremely high concentrations of SLS following physical or chemical damage to the eye can result in a slowed healing process. The results of this study have since been wrongly quoted to state that SLS-containing products lead to blindness or severe corneal damage.8 A different study tested for possible ocular irritation in vivo by submerging the lens of an eye into a 20% SLS solution, which accurately approximates the concentration of SLS in rinse-off consumer products.9 However, to achieve ocular irritation, the eyes of laboratory animals were exposed to SLS constantly for 14 days, which would not occur in practical use.9 Similarly, a third study achieved cataract formation in a laboratory only by immersing the lens of an eye into a highly concentrated solution of SLS.10 Such studies are not appropriate representations of how SLS-containing products are used by consumers and have unfortunately been vulnerable to misinterpretation by the general public.

There is no known study that has shown SLS to be carcinogenic. One possible origin of this idea may be from the wrongful interpretation of studies that used SLS as a vehicle substance to test agents that were deemed to be carcinogenic.11 Another possible source of the idea that SLS is carcinogenic comes from its association with 1,4-dioxane, a by-product of the synthesis of certain sulfates such as sodium laureth sulfate due to a process known as ethoxylation.6,12 Although SLS does not undergo this process in its formation and is not linked to 1,4-dioxane, there is potential for cross-contamination of SLS with 1,4-dioxane, which cannot be overlooked. 1,4-Dioxane is classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B)” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer,13 but screening of SLS for this substance prior to its use in commercial products is standard.

Sulfates are inexpensive detergents that are responsible for lather formation in shampoos as well as in many household cleaning agents.5 Sulfates, similar to all anionic surfactants, are characterized by a negatively charged hydrophilic polar group. The best-known and most commonly used anionic surfactants are sulfated fatty alcohols, alkyl sulfates, and their polyethoxylated analogues alkyl ether sulfates.5,6 Sodium lauryl sulfate (also known as sodium laurilsulfate or sodium dodecyl sulfate) is the most common of them all, found in shampoo and conditioner formulations. Ammonium lauryl sulfate and sodium laureth sulfate are other sulfates commonly used in shampoos and household cleansing products. Sodium lauryl sulfate is a nonvolatile, water-soluble compound. Its partition coefficient (P0), a measure of a substance’s hydrophilic or lipophilic nature, is low at 1.6, making it a rather hydrophilic substance.6 Hydrophilic substances tend to have low bioaccumulation profiles in the body. Additionally, SLS is readily biodegradable. It can be derived from both synthetic and naturally occurring sources; for example, palm kernel oil, petrolatum, and coconut oil are all sources of lauric acid, the starting ingredient used to synthesize SLS. Sodium lauryl sulfate is created by reacting lauryl alcohol with sulfur trioxide gas, followed by neutralization with sodium carbonate (also a naturally occurring compound).6 Sodium lauryl sulfate and other sulfate-containing shampoos widely replaced the usage of traditional soaps formulated from animal or vegetable fats, as these latter formations created a film of insoluble calcium salts on the hair strands upon contact with water, resulting in tangled, dull-appearing hair.5 Additionally, sulfates were preferred to the alkaline pH of traditional soap, which can be harsh on hair strands and cause irritation of the skin and mucous membranes.14 Because they are highly water soluble, sulfates enable the formulation of clear shampoos. They exhibit remarkable cleaning properties and lather formation.5,14