User login

HHS okays first U.S. pilot to mandate coverage of gender-affirming care

The approval means transgender-related care must be included as part of the essential benefits offered on the state’s Affordable Care Act marketplace, which includes private individual and small group insurance plans. The coverage will start Jan. 1, 2023. Colorado is the first state in the United States to require such coverage.

The HHS notes that gender-affirming treatments to be covered include eye and lid modifications, face tightening, facial bone remodeling for facial feminization, breast/chest construction and reductions, and laser hair removal.

“I am proud to stand with Colorado to remove barriers that have historically made it difficult for transgender people to access health coverage and medical care,” said HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra in a statement.

“Colorado’s expansion of their essential health benefits to include gender-affirming surgery and other treatments is a model for other states to follow, and we invite other states to follow suit,” said Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure in the statement.

Medicaid already covers comprehensive transgender care in Colorado.

The LGBTQ+ advocacy group One Colorado estimated that, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, only 5% of the state’s LGBTQ+ community was uninsured in 2019, compared to 10% in 2011.

However, 34% of transgender respondents to a One Colorado poll in 2018 said they had been denied coverage for an LGBTQ-specific medical service, such as gender-affirming care. Sixty-two percent said that a lack of insurance or limited insurance was a barrier to care; 84% said another barrier was the lack of adequately trained mental and behavioral health professionals.

Mental health also covered

The Colorado plan requires individual and small group plans to cover an annual 45- to 60-minute mental health wellness exam with a qualified mental health care practitioner. The visit can include behavioral health screening, education and consultation about healthy lifestyle changes, referrals to mental health treatment, and discussion of potential medication options.

The plans also must cover an additional 15 medications as alternatives to opioids and up to six acupuncture visits annually.

“This plan expands access to mental health services for Coloradans while helping those fighting substance abuse to overcome their addiction,” said Governor Jared Polis in a statement.

“This improves care for Coloradans and ensures that even more Coloradans have access to help when they need it,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval means transgender-related care must be included as part of the essential benefits offered on the state’s Affordable Care Act marketplace, which includes private individual and small group insurance plans. The coverage will start Jan. 1, 2023. Colorado is the first state in the United States to require such coverage.

The HHS notes that gender-affirming treatments to be covered include eye and lid modifications, face tightening, facial bone remodeling for facial feminization, breast/chest construction and reductions, and laser hair removal.

“I am proud to stand with Colorado to remove barriers that have historically made it difficult for transgender people to access health coverage and medical care,” said HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra in a statement.

“Colorado’s expansion of their essential health benefits to include gender-affirming surgery and other treatments is a model for other states to follow, and we invite other states to follow suit,” said Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure in the statement.

Medicaid already covers comprehensive transgender care in Colorado.

The LGBTQ+ advocacy group One Colorado estimated that, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, only 5% of the state’s LGBTQ+ community was uninsured in 2019, compared to 10% in 2011.

However, 34% of transgender respondents to a One Colorado poll in 2018 said they had been denied coverage for an LGBTQ-specific medical service, such as gender-affirming care. Sixty-two percent said that a lack of insurance or limited insurance was a barrier to care; 84% said another barrier was the lack of adequately trained mental and behavioral health professionals.

Mental health also covered

The Colorado plan requires individual and small group plans to cover an annual 45- to 60-minute mental health wellness exam with a qualified mental health care practitioner. The visit can include behavioral health screening, education and consultation about healthy lifestyle changes, referrals to mental health treatment, and discussion of potential medication options.

The plans also must cover an additional 15 medications as alternatives to opioids and up to six acupuncture visits annually.

“This plan expands access to mental health services for Coloradans while helping those fighting substance abuse to overcome their addiction,” said Governor Jared Polis in a statement.

“This improves care for Coloradans and ensures that even more Coloradans have access to help when they need it,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval means transgender-related care must be included as part of the essential benefits offered on the state’s Affordable Care Act marketplace, which includes private individual and small group insurance plans. The coverage will start Jan. 1, 2023. Colorado is the first state in the United States to require such coverage.

The HHS notes that gender-affirming treatments to be covered include eye and lid modifications, face tightening, facial bone remodeling for facial feminization, breast/chest construction and reductions, and laser hair removal.

“I am proud to stand with Colorado to remove barriers that have historically made it difficult for transgender people to access health coverage and medical care,” said HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra in a statement.

“Colorado’s expansion of their essential health benefits to include gender-affirming surgery and other treatments is a model for other states to follow, and we invite other states to follow suit,” said Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure in the statement.

Medicaid already covers comprehensive transgender care in Colorado.

The LGBTQ+ advocacy group One Colorado estimated that, thanks to the Affordable Care Act, only 5% of the state’s LGBTQ+ community was uninsured in 2019, compared to 10% in 2011.

However, 34% of transgender respondents to a One Colorado poll in 2018 said they had been denied coverage for an LGBTQ-specific medical service, such as gender-affirming care. Sixty-two percent said that a lack of insurance or limited insurance was a barrier to care; 84% said another barrier was the lack of adequately trained mental and behavioral health professionals.

Mental health also covered

The Colorado plan requires individual and small group plans to cover an annual 45- to 60-minute mental health wellness exam with a qualified mental health care practitioner. The visit can include behavioral health screening, education and consultation about healthy lifestyle changes, referrals to mental health treatment, and discussion of potential medication options.

The plans also must cover an additional 15 medications as alternatives to opioids and up to six acupuncture visits annually.

“This plan expands access to mental health services for Coloradans while helping those fighting substance abuse to overcome their addiction,” said Governor Jared Polis in a statement.

“This improves care for Coloradans and ensures that even more Coloradans have access to help when they need it,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Homicide remains a top cause of maternal mortality

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

The prevalence of homicide was 16% higher in pregnant women or postpartum women than nonpregnant or nonpostpartum women in the United States, according to 2018 and 2019 mortality data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Homicide has long been identified as a leading cause of death during pregnancy, but homicide is not counted in estimates of maternal mortality, nor is it emphasized as a target for prevention and intervention, wrote Maeve Wallace, PhD, of Tulane University, New Orleans, and colleagues.

Data on maternal mortality (defined as “death while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy from causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy”) were limited until the addition of pregnancy to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death in 2003; all 50 states had adopted it by 2018, the researchers noted.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers analyzed the first 2 years of nationally available data to identify pregnancy-associated mortality and characterize other risk factors such as age and race.

The researchers identified 4,705 female homicides in 2018 and 2019. Of these, 273 (5.8%) occurred in women who were pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy. Approximately half (50.2%) of the pregnant or postpartum victims were non-Hispanic Black, 30% were non-Hispanic white, 9.5% were Hispanic, and 10.3% were other races; approximately one-third (35.5%) were in the 20- to 24-year age group.

Overall, the ratio was 3.62 homicides per 100,000 live births among females who were either pregnant or within 1 year post partum, compared to 3.12 homicides per 100,000 live births in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum females aged 10-44 years (P = .05).

“Patterns were similar in further stratification by both race and age such that pregnancy was associated with more than a doubled risk of homicide among girls and women aged 10–24 in both the non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black populations,” the researchers wrote.

The findings are consistent with previous studies, which “implicates health and social system failures. Although we are unable to directly evaluate the involvement of intimate partner violence (IPV) in this report, we did find that a majority of pregnancy-associated homicides occurred in the home, implicating the likelihood of involvement by persons known to the victim,” they noted. In addition, the data showed that approximately 70% of the incidents of homicide in pregnant and postpartum women involved a firearm, an increase over previous estimates.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of circumstantial information and incomplete data on victim characteristics, the researchers noted. Other key limitations included the potential for false-positives and false-negatives when recording pregnancy status, which could lead to underestimates of pregnancy-associated homicides, and the lack of data on pregnancy outcomes for women who experienced live birth, abortion, or miscarriage within a year of death.

However, the results highlight the need for increased awareness and training of physicians in completing the pregnancy checkbox on death certificates, and the need for action on recommendations and interventions to prevent maternal deaths from homicide, they emphasized.

“Although encouraging, a commitment to the actual implementation of policies and investments known to be effective at protecting and the promoting the health and safety of girls and women must follow,” they concluded.

Data highlight disparities

“This study could not be done effectively prior to now, as the adoption of the pregnancy checkbox on the U.S. Standard Certificate of Death was only available in all 50 states as of 2018,” Sarah W. Prager, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview.

“This study also demonstrates what was already known, which is that pregnancy is a high-risk time period for intimate partner violence, including homicide. The differences in homicide rates based on race and ethnicity also highlight the clear disparities in maternal mortality in the U.S. that are attributable to racism. There is more attention being paid to maternal mortality and the differential experience based on race, and this demonstrates that simply addressing medical management during pregnancy is not enough – we need to address root causes of racism if we truly want to reduce maternal mortality,” Dr. Prager said.

“The primary take-home message for clinicians is to ascertain safety from every patient, and to try to reduce the impacts of racism on health care for patients, especially during pregnancy,” she said.

Although more detailed records would help with elucidating causes versus associations, “more research is not the answer,” Dr. Prager stated. “The real solution here is to have better gun safety laws, and to put significant resources toward reducing the impacts of racism on health care and our society.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Prager had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Underrepresented Minority Students Applying to Dermatology Residency in the COVID-19 Era: Challenges and Considerations

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

Practice Points

- Dermatology remains one of the least diverse medical specialties.

- Underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine residency applicants might be negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The implementation of holistic review, diversity and inclusion initiatives, and virtual opportunities might mitigate some of the barriers faced by URM applicants.

Cutaneous Manifestations and Clinical Disparities in Patients Without Housing

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

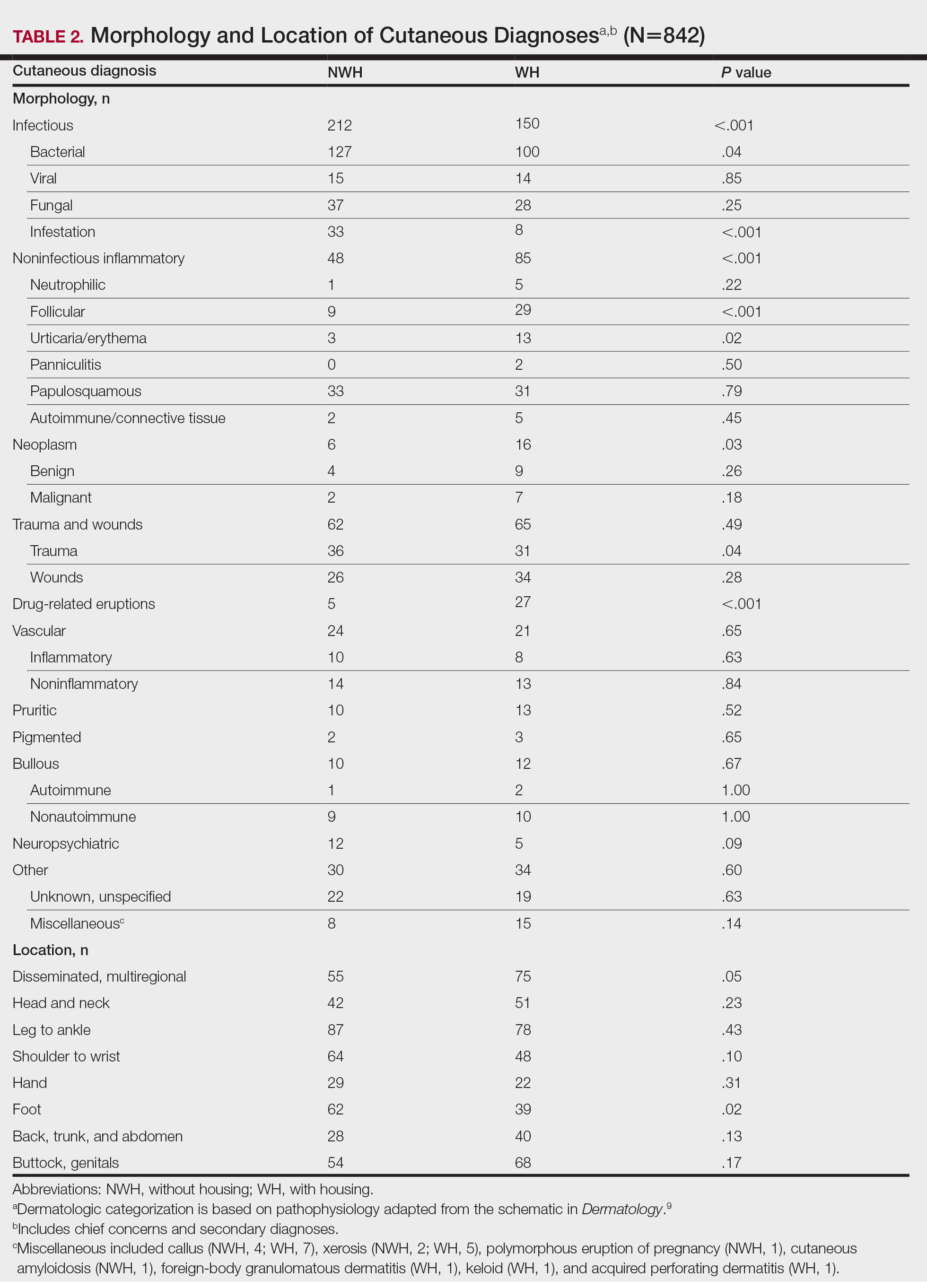

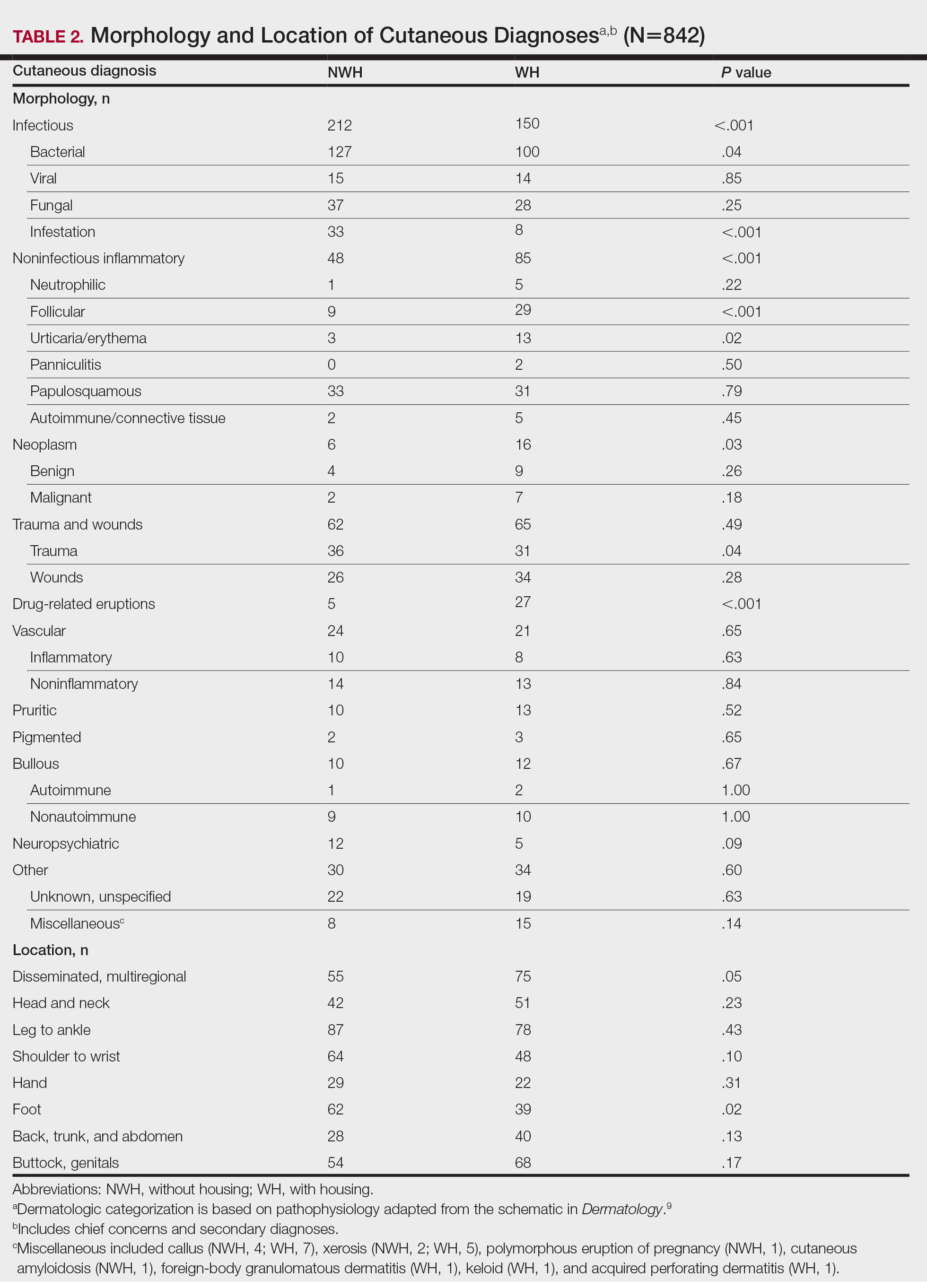

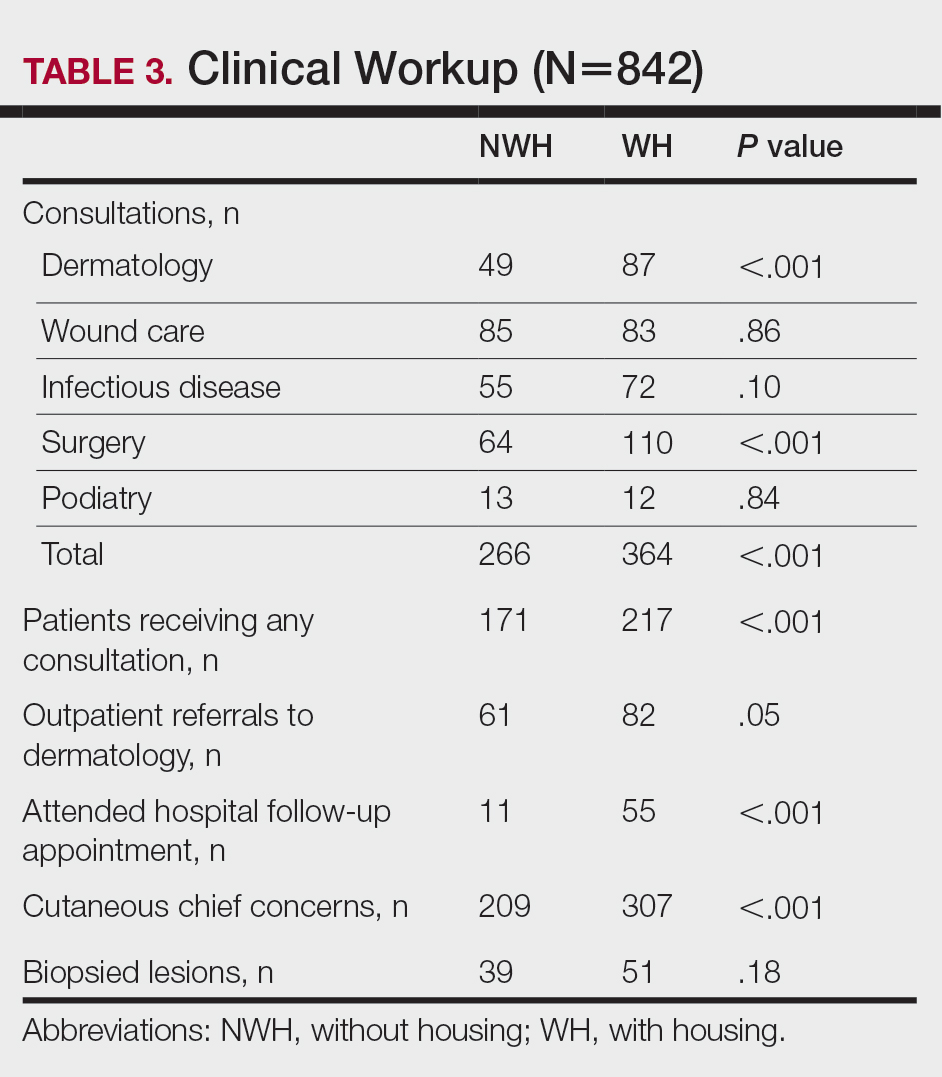

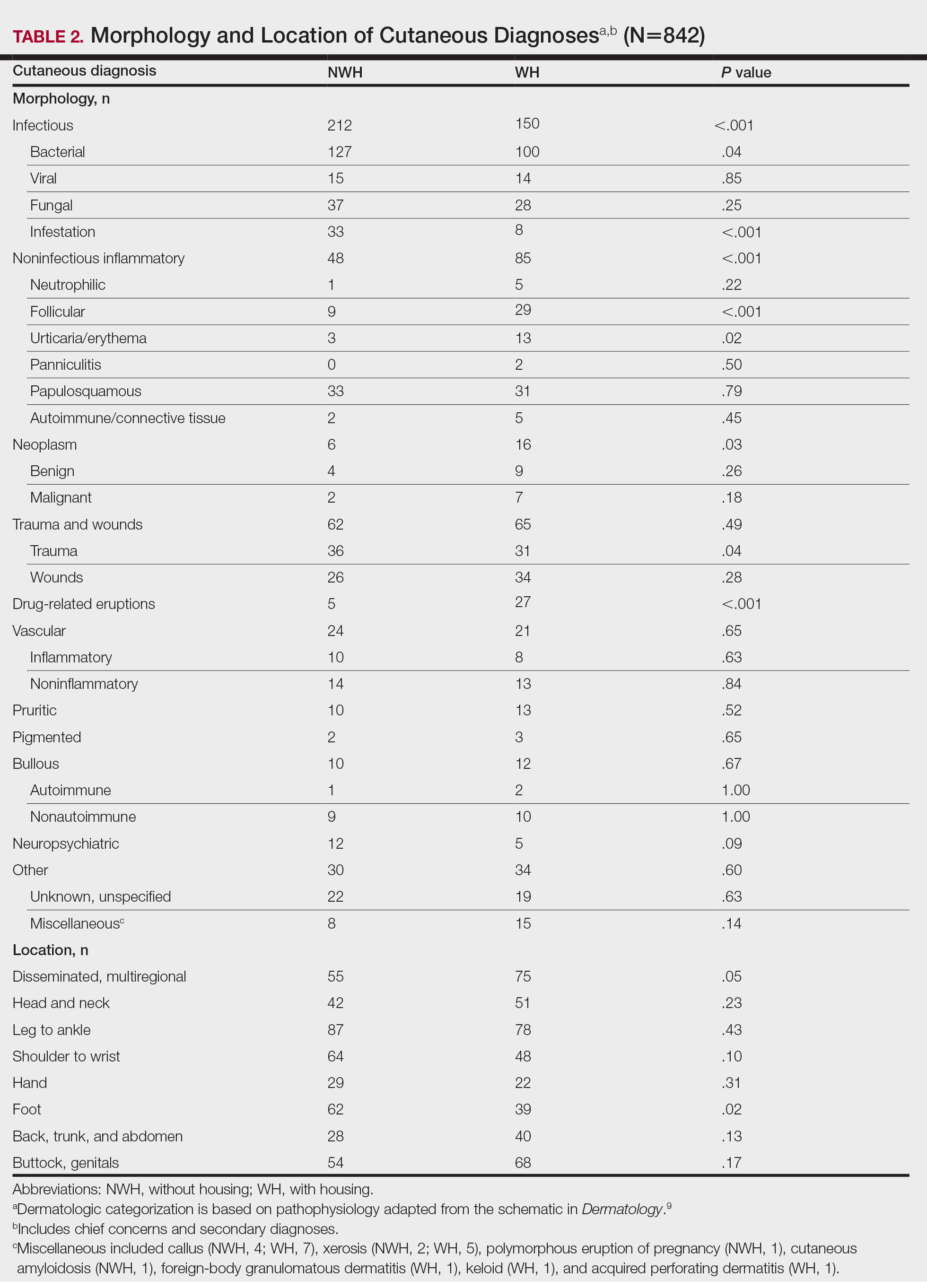

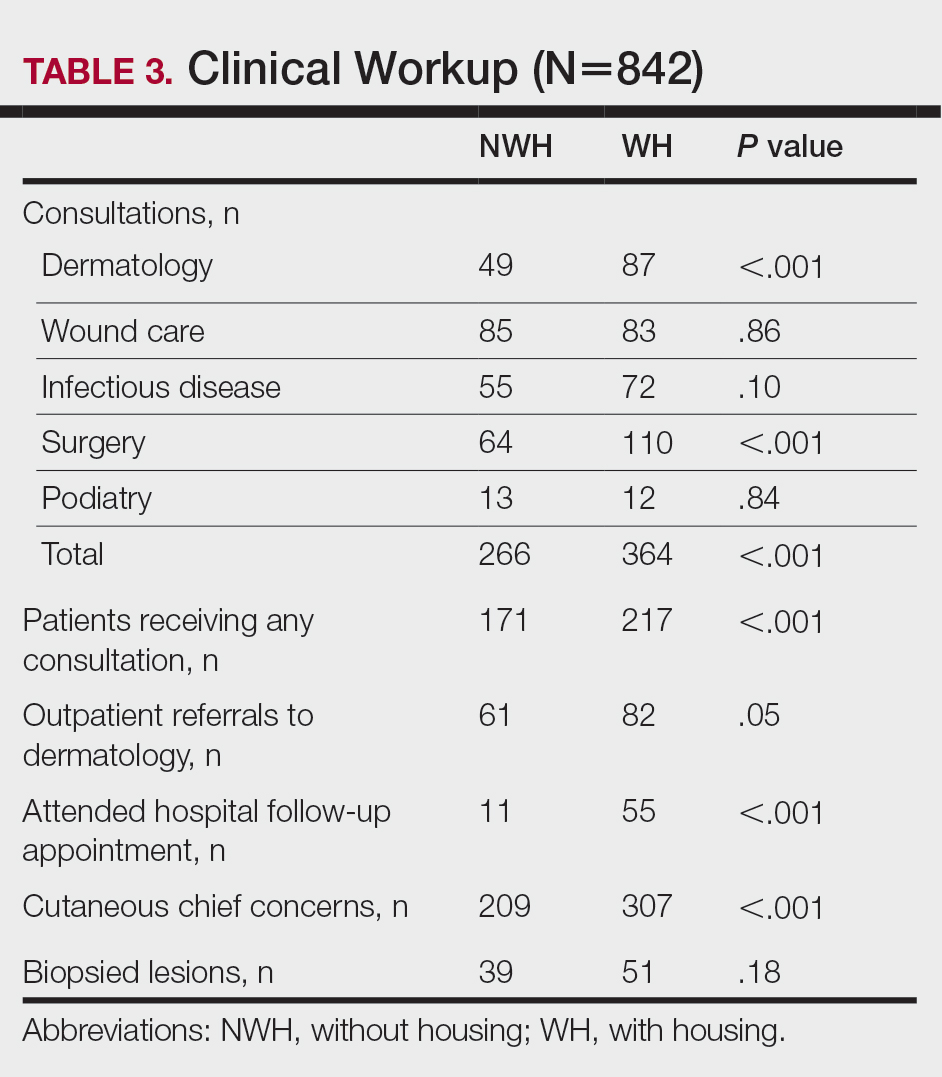

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

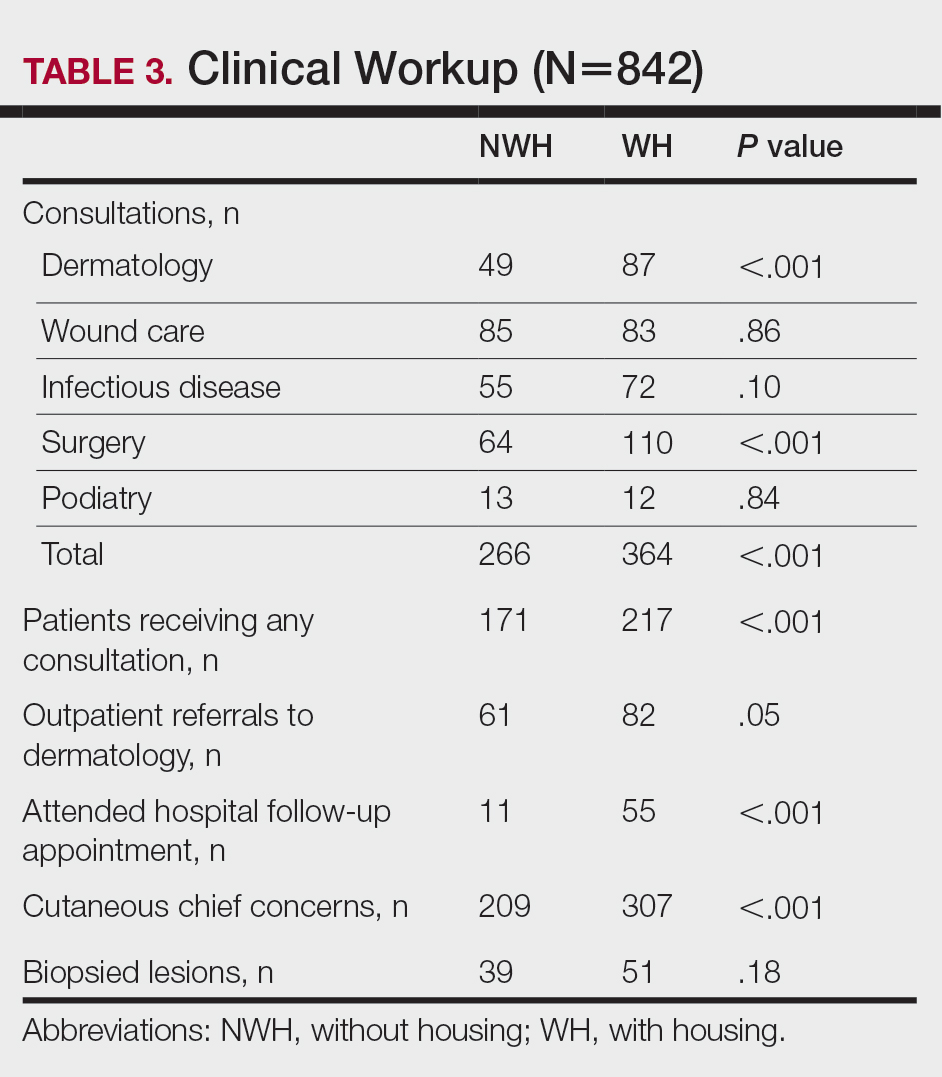

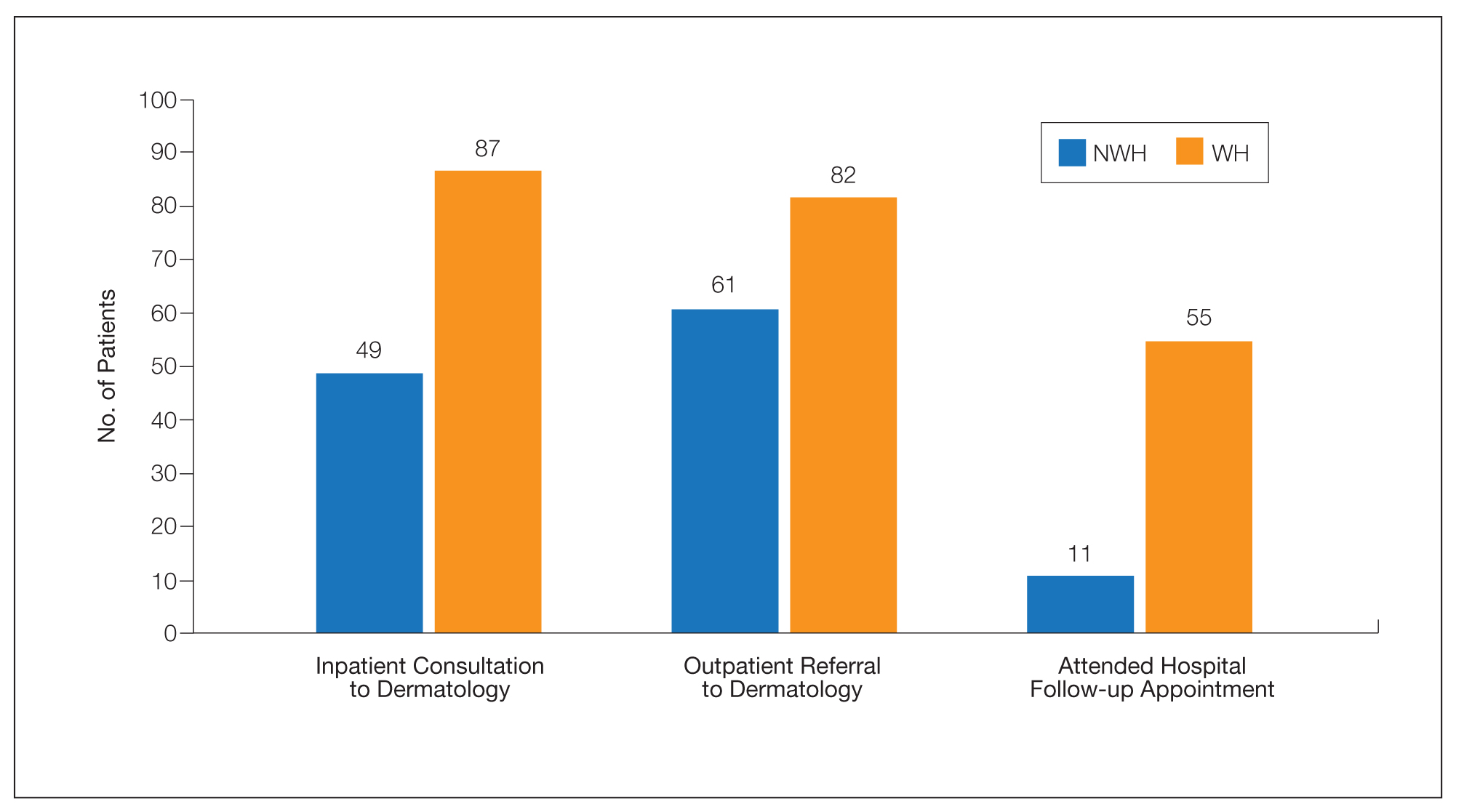

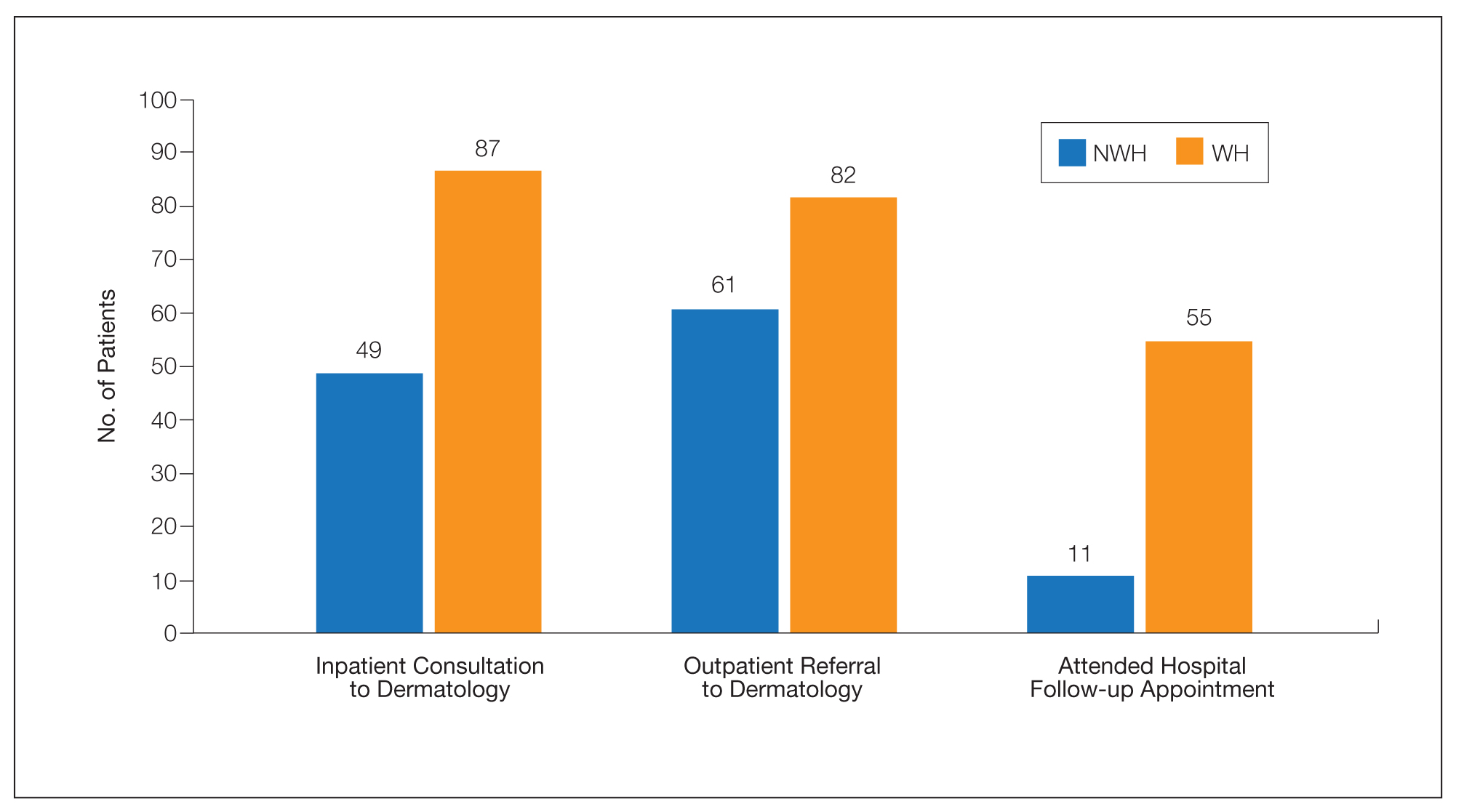

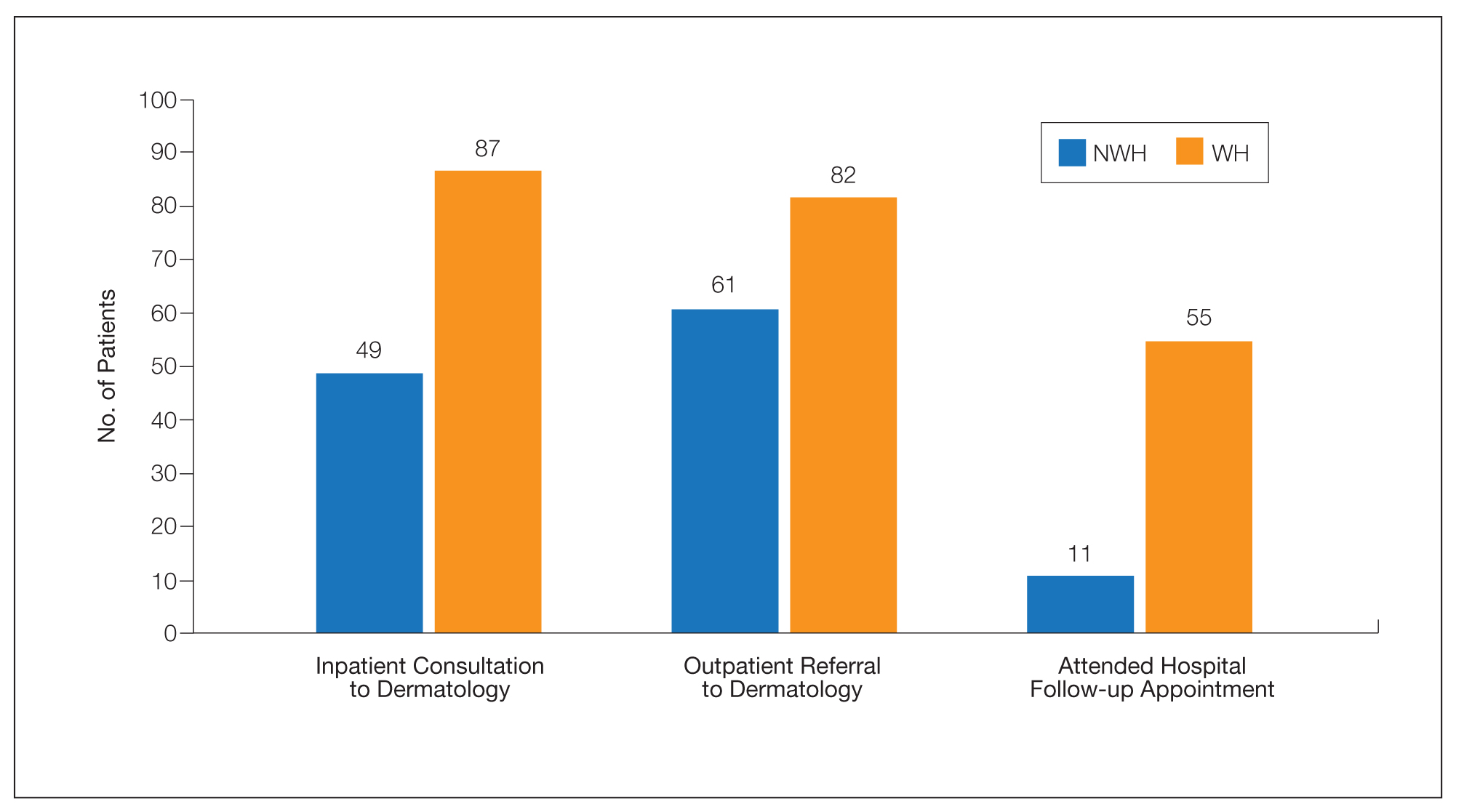

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.

Future Directions—Owing to limitations of a retrospective cohort study, we present several opportunities for further research on this vulnerable population. The severity of disease, especially infectious etiologies, should be graded to determine if NWH patients truly present later in the disease course. The duration and quality of housing for NWH patients could be categorized based on living conditions (eg, on the street vs in a shelter). Although the findings of our NWH cohort presenting to the ED at UMC provide helpful insight into dermatologic disease, these findings may be disparate from those conducted at other locations in the United States. University Medical Center provides care to mostly subsidized insurance plans in a racially diverse community. Improved outcomes for the NWH individuals living in New Orleans start with obtaining a greater understanding of their diseases and where disparities exist that can be bridged with better care.

Acknowledgment—The dataset generated during this study and used for analysis is not publicly available to protect public health information but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384:1529-1540. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Contag C, Lowenstein SE, Jain S, et al. Survey of symptomatic dermatologic disease in homeless patients at a shelter-based clinic. Our Dermatol Online. 2017;8:133-137. doi:10.7241/ourd.20172.37

- Hollestein LM, Nijsten T. An insight into the global burden of skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1499-1501. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.513

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Grossberg AL, Carranza D, Lamp K, et al. Dermatologic care in the homeless and underserved populations: observations from the Venice Family Clinic. Cutis. 2012;89:25-32.

- Mackelprang JL, Graves JM, Rivara FP. Homeless in America: injuries treated in US emergency departments, 2007-2011. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:289-297. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.371

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.013

- Stratigos AJ, Stern R, Gonzalez E, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a cohort of shelter-based homeless men. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:197-202. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70048-4

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Badiaga S, Menard A, Tissot Dupont H, et al. Prevalence of skin infections in sheltered homeless. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:382-386.

More than half a million individuals are without housing (NWH) on any given night in the United States, as estimated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 Lack of hygiene, increased risk of infection and infestation due to living conditions, and barriers to health care put these individuals at increased risk for disease. 2 Skin disease, including fungal infection and acne, are within the top 10 most prevalent diseases worldwide and can cause major psychologic impairment, yet dermatologic concerns and clinical outcomes in NWH patients have not been well characterized. 2-5 Further, because this vulnerable demographic tends to be underinsured, they frequently present to the emergency department (ED) for management of disease. 1,6 Survey of common concerns in NWH patients is of utility to consulting dermatologists and nondermatologist providers in the ED, who can familiarize themselves with management of diseases they are more likely to encounter. Few studies examine dermatologic conditions in the ED, and a thorough literature review indicates none have included homelessness as a variable. 6,7 Additionally, comparison with a matched control group of patients with housing (WH) is limited. 5,8 We present one of the largest comparisons of cutaneous disease in NWH vs WH patients in a single hospital system to elucidate the types of cutaneous disease that motivate patients to seek care, the location of skin disease, and differences in clinical care.

Methods

A retrospective medical record review of patients seen for an inclusive list of dermatologic diagnoses in the ED or while admitted at University Medical Center New Orleans, Louisiana (UMC), between January 1, 2018, and April 21, 2020, was conducted. This study was qualified as exempt from the institutional review board by Louisiana State University because it proposed zero risk to the patients and remained completely anonymous. Eight hundred forty-two total medical records were reviewed (NWH, 421; WH, 421)(Table 1). Patients with housing were matched based on self-identified race and ethnicity, sex, and age. Disease categories were constructed based on fundamental pathophysiology adapted from Dermatology9: infectious, noninfectious inflammatory, neoplasm, trauma and wounds, drug-related eruptions, vascular, pruritic, pigmented, bullous, neuropsychiatric, and other. Other included unspecified eruptions as well as miscellaneous lesions such as calluses. The current chief concern, anatomic location, and configuration were recorded, as well as biopsied lesions and outpatient referrals or inpatient consultations to dermatology or other specialties, including wound care, infectious disease, podiatry, and surgery. χ2 analysis was used to analyze significance of cutaneous categories, body location, and referrals. Groups smaller than 5 defaulted to the Fisher exact test.

Results

The total diagnoses (including both chief concerns and secondary diagnoses) are shown in Table 2. Chief concerns were more frequently cutaneous or dermatologic for WH (NWH, 209; WH, 307; P<.001). In both groups, cutaneous infectious etiologies were more likely to be a patient’s presenting chief concern (58% NWH, P=.002; 42% WH, P<.001). Noninfectious inflammatory etiologies and pigmented lesions were more likely to be secondary diagnoses with an unrelated noncutaneous concern; noninfectious inflammatory etiologies were only 16% of the total cutaneous chief concerns (11% NWH, P=.04; 20% WH, P=.03), and no pigmented lesions were chief concerns.

Infection was the most common chief concern, though NWH patients presented with significantly more infectious concerns (NWH, 212; WH, 150; P<.001), particularly infestations (NWH, 33; WH, 8; P<.001) and bacterial etiologies (NWH, 127; WH, 100; P=.04). The majority of bacterial etiologies were either an abscess or cellulitis (NWH, 106; WH, 83), though infected chronic wounds were categorized as bacterial infection when treated definitively as such (eg, in the case of sacral ulcers causing osteomyelitis)(NWH, 21; WH, 17). Of note, infectious etiology was associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) in both NWH and WH patients. Of 184 NWH who reported IVDU, 127 had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Similarly, 43 of 56 total WH patients who reported IVDU had an infectious diagnosis (P<.001). Infestation (within the infectious category) included scabies (NWH, 20; WH, 3) and insect or arthropod bites (NWH, 12; WH, 5). Two NWH patients also presented with swelling of the lower extremities and were subsequently diagnosed with maggot infestations. Fungal and viral etiologies were not significantly increased in either group; however, NWH did have a higher incidence of tinea pedis (NWH, 14; WH, 4; P=.03).

More neoplasms (NWH, 6; WH, 16; P=.03), noninfectious inflammatory eruptions (NWH, 48; WH, 85; P<.001), and cutaneous drug eruptions (NWH, 5; WH, 27; P<.001) were reported in WH patients. There was no significant difference in benign vs malignant neoplastic processes between groups. More noninfectious inflammatory eruptions in WH were specifically driven by a markedly increased incidence of follicular (NWH, 9; WH, 29; P<.001) and urticarial/erythematous (NWH, 3; WH, 13; P=.02) lesions. Follicular etiologies included acne (NWH, 1; WH, 6; P=.12), folliculitis (NWH, 5; WH, 2; P=.45), hidradenitis suppurativa (NWH, 2; WH, 11; P=.02), and pilonidal and sebaceous cysts (NWH, 1; WH, 10; P=.01). Allergic urticaria dominated the urticarial/erythematous category (NWH, 3; WH, 11; P=.06), though there were 2 WH presentations of diffuse erythema and skin peeling.

Another substantial proportion of cutaneous etiologies were due to trauma or chronic wounds. Significantly more traumatic injuries presented in NWH patients vs WH patients (36 vs 31; P=.04). Trauma included human or dog bites (NWH, 5; WH, 4), sunburns (NWH, 3; WH, 0), other burns (NWH, 11; WH, 13), abrasions and lacerations (NWH, 16; WH, 3; P=.004), and foreign bodies (NWH, 1; WH, 1). Wounds consisted of chronic wounds such as those due to diabetes mellitus (foot ulcers) or immobility (sacral ulcers); numbers were similar between groups.

Looking at location, NWH patients had more pathology on the feet (NWH, 62; WH, 39; P=.02), whereas WH patients had more disseminated multiregional concerns (NWH, 55; WH, 75; P=.05). No one body location was notably more likely to warrant a chief concern.

For clinical outcomes, more WH patients received a consultation of any kind (NWH, 171; WH, 217; P<.001), consultation to dermatology (NWH, 49; WH, 87; P<.001), and consultation to surgery (NWH, 64; WH, 110; P<.001)(Table 3 and Figure). More outpatient referrals to dermatology were made for WH patients (NWH, 61; WH, 82; P=.05). Notably, NWH patients presented for 80% fewer hospital follow-up appointments (NWH, 11; WH, 55; P<.001). It is essential to note that these findings were not affected by self-reported race or ethnicity. Results remained significant when broken into cohorts consisting of patients with and without skin of color.

Comment

Cutaneous Concerns in NWH Patients—Although cutaneous disease has been reported to disproportionately affect NWH patients,10 in our cohort, NWH patients had fewer cutaneous chief concerns than WH patients. However, without comparing with all patients entering the ED at UMC, we cannot make a statement on this claim. We do present a few reasons why NWH patients do not have more cutaneous concerns. First, they may wait to present with cutaneous disease until it becomes more severe (eg, until chronic wounds have progressed to infections). Second, as discussed in depth by Hollestein and Nijsten,3 dermatologic disease may be a major contributor to the overall count of disability-adjusted life years but may play a minor role in individual disability. Therefore, skin disease often is considered less important on an individual basis, despite substantial psychosocial burden, leading to further stigmatization of this vulnerable population and discouraged care-seeking behavior, particularly for noninfectious inflammatory eruptions, which were notably more present in WH individuals. Third, fewer dermatologic lesions were reported on NWH patients, which may explain why all 3 WH pigmented lesions were diagnosed after presentation with a noncutaneous concern (eg, headache, anemia, nausea).

Infectious Cutaneous Diagnoses—The increased presentation of infectious etiologies, especially bacterial, is linked to the increased numbers of IVDUs reported in NWH individuals as well as increased exposure and decreased access to basic hygienic supplies. Intravenous drug use acted as an effect modifier of infectious etiology diagnoses, playing a major role in both NWH and WH cohorts. Although Black and Hispanic individuals as well as individuals with low socioeconomic status have increased proportions of skin cancer, there are inadequate data on the prevalence in NWH individuals.4 We found no increase in malignant dermatologic processes in NWH individuals; however, this may be secondary to inadequate screening with a total body skin examination.

Clinical Workup of NWH Patients—Because most NWH individuals present to the ED to receive care, their care compared with WH patients should be considered. In this cohort, WH patients received a less extensive clinical workup. They received almost half as many dermatologic consultations and fewer outpatient referrals to dermatology. Major communication barriers may affect NWH presentation to follow-up, which was drastically lower than WH individuals, as scheduling typically occurs well after discharge from the ED or inpatient unit. We suggest a few alterations to improve dermatologic care for NWH individuals:

• Consider inpatient consultation for serious dermatologic conditions—even if chronic—to improve disease control, considering that many barriers inhibit follow-up in clinic.

• Involve outreach teams, such as the Assertive Community Treatment teams, that assist individuals by delivering medicine for psychiatric disorders, conducting total-body skin examinations, assisting with wound care, providing basic skin barrier creams or medicaments, and carrying information regarding outpatient follow-up.

• Educate ED providers on the most common skin concerns, especially those that fall within the noninfectious inflammatory category, such as hidradenitis suppurativa, which could easily be misdiagnosed as an abscess.