User login

‘Down to my last diaper’: The anxiety of parenting in poverty

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Major increase seen in cosmeceutical alternatives to topical hydroquinone

along with new strategies to improve their efficacy, according to a report at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ten or 15 years ago, I was showing a slide with five [alternatives to hydroquinone]. Now there are dozens,” reported Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the department of dermatology at the University of Miami.

The growth in alternatives to hydroquinone is timely. After threats to do so for more than a decade, the Food and Drug Administration finally banned hydroquinone from OTC products in 2020. The ban was folded into the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act passed in March of 2020 and then implemented the following September.

Until the ban of hydroquinone, OTC products with this compound were widely sought by many individuals with darker skin tones to self-treat melasma and other forms of hyperpigmentation, according to Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. Hydroquinone is still available in prescription products, but she is often asked for OTC alternatives, and she says the list is long and getting longer.

Niacinamide

Detailing the products she has been recommending most frequently as substitutes, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reported that several are supported by high quality studies. One example is niacinamide.

Of the several controlled studies she cited, one double-blind randomized trial found niacinamide to be equivalent to hydroquinone for melasma on the basis of colorimetric measures. The study compared 4% niacinamide cream applied on one side of the face with 4% hydroquinone cream applied on the other side in 27 patients with melasma. Although the proportion of responses rated good or excellent on a subjective basis was lower with niacinamide (44% vs. 55%), the difference was not statistically significant and niacinamide cream was clearly active, producing objective improvements in mast cell infiltrate and solar elastosis in melasma skin as well. Both were well tolerated.

In other studies, niacinamide has been shown to be effective in the treatment of melasma when combined with other active agents such as tranexamic acid, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who added that OTC products containing niacinamide are now “among my favorites” when directing patients to cosmeceuticals for hyperpigmentation.

Topical vitamin C

Topical vitamin C or ascorbic acid is another. Like niacinamide, topical vitamin C has also been compared with hydroquinone in a double-blind, randomized trial. Although the niacinamide trial and this study were performed 10 or more years ago, these data have new relevance with the ban of OTC hydroquinone.

In the study, 5% ascorbic acid cream on one side of the face was compared with 4% hydroquinone cream, applied on the other side, in 16 women with melasma. Again, there were no statistical differences in colorimetric measures, but good to excellent results were reported for 93% of the sides of the face treated with hydroquinone versus 62.5% of the sides treated with vitamin C (P < .05). “Hydroquinone performed better, but the vitamin C was active and very well tolerated,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said.

However, the ascorbic acid cream was better tolerated, with a far lower rate of adverse events (6.2% vs. 68.7%), an advantage that makes it easy to recommend to patients, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who now uses it frequently in her own practice.

Liquiritin, a licorice extract, is another lightening agent increasingly included in OTC products that she also recommends. In two older studies in medical journals published in Pakistan, both the 2% and 4% strengths of liquiritin cream outperformed hydroquinone on the basis of a Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) rating. The liquiritin cream was well tolerated in both studies.

Azelaic acid, tranexamic acid

OTC products containing azelaic acid are also effective for hyperpigmentation based on published trials in which they were compared with hydroquinone for treating melasma. In one study of 29 women with melasma cited by Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, 20% azelaic acid cream was more effective than hydroquinone 4% cream after 2 months of treatment on the basis of the mean MASI score (6.2 vs. 3.8).

The list also includes cysteamine, silymarin, and tranexamic acid.

In the case of tranexamic acid, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd cited a relatively recent study of 60 patients with melasma, comparing two strategies for applying tranexamic acid to treatment with hydroquinone over 12 weeks. Compared with 2% hydroquinone (applied nightly) or 1.8% liposomal tranexamic acid (applied twice a day), 5% tranexamic acid solution with microneedling (weekly) had a slightly greater rate of success defined as more than a 50% improvement in hyperpigmentation in an Asian population (30%, 27.8%, and 33.3%, respectively).

“Microneedling is a newer technology that appears to be effective at improving absorption,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. She predicts that microneedling will be used with increasing frequency in combination with topical cosmeceuticals.

She also predicted that these topical agents will be increasingly employed in combinations as the field of cosmeceuticals becomes increasingly more sophisticated. “When it comes to skin quality, cosmeceuticals remain our first-line therapy, especially in skin of color,” she said.

The rapid growth and utility of OTC cosmeceuticals is an area that dermatologists need to be following, according to Darius Mehregan, MD, chair of the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Detroit, who was senior author of an article published last year that reviewed the ingredients of popular OTC cosmeceuticals.

“Our patients have a great interest in cosmeceuticals and are looking to us for guidance. I think we have a responsibility to help them identify products supported by evidence and to warn them about potential side effects,” Dr. Mehregan, who was not at the meeting, said in an interview.

He agreed that the removal of hydroquinone from OTC products will create a specific need in the area of cosmeceuticals.

“Hydroquinone has for a long time been one of the most effective agents in OTC products for melasma, so patients are going to be looking for alternatives. Identifying which drugs have shown efficacy in controlled studies will be very helpful,” he said.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reports financial relationships with Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oréal, Galderma, Allergan, and Somabella Laboratories. Dr. Mehregan reports no potential conflicts of interest.

along with new strategies to improve their efficacy, according to a report at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ten or 15 years ago, I was showing a slide with five [alternatives to hydroquinone]. Now there are dozens,” reported Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the department of dermatology at the University of Miami.

The growth in alternatives to hydroquinone is timely. After threats to do so for more than a decade, the Food and Drug Administration finally banned hydroquinone from OTC products in 2020. The ban was folded into the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act passed in March of 2020 and then implemented the following September.

Until the ban of hydroquinone, OTC products with this compound were widely sought by many individuals with darker skin tones to self-treat melasma and other forms of hyperpigmentation, according to Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. Hydroquinone is still available in prescription products, but she is often asked for OTC alternatives, and she says the list is long and getting longer.

Niacinamide

Detailing the products she has been recommending most frequently as substitutes, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reported that several are supported by high quality studies. One example is niacinamide.

Of the several controlled studies she cited, one double-blind randomized trial found niacinamide to be equivalent to hydroquinone for melasma on the basis of colorimetric measures. The study compared 4% niacinamide cream applied on one side of the face with 4% hydroquinone cream applied on the other side in 27 patients with melasma. Although the proportion of responses rated good or excellent on a subjective basis was lower with niacinamide (44% vs. 55%), the difference was not statistically significant and niacinamide cream was clearly active, producing objective improvements in mast cell infiltrate and solar elastosis in melasma skin as well. Both were well tolerated.

In other studies, niacinamide has been shown to be effective in the treatment of melasma when combined with other active agents such as tranexamic acid, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who added that OTC products containing niacinamide are now “among my favorites” when directing patients to cosmeceuticals for hyperpigmentation.

Topical vitamin C

Topical vitamin C or ascorbic acid is another. Like niacinamide, topical vitamin C has also been compared with hydroquinone in a double-blind, randomized trial. Although the niacinamide trial and this study were performed 10 or more years ago, these data have new relevance with the ban of OTC hydroquinone.

In the study, 5% ascorbic acid cream on one side of the face was compared with 4% hydroquinone cream, applied on the other side, in 16 women with melasma. Again, there were no statistical differences in colorimetric measures, but good to excellent results were reported for 93% of the sides of the face treated with hydroquinone versus 62.5% of the sides treated with vitamin C (P < .05). “Hydroquinone performed better, but the vitamin C was active and very well tolerated,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said.

However, the ascorbic acid cream was better tolerated, with a far lower rate of adverse events (6.2% vs. 68.7%), an advantage that makes it easy to recommend to patients, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who now uses it frequently in her own practice.

Liquiritin, a licorice extract, is another lightening agent increasingly included in OTC products that she also recommends. In two older studies in medical journals published in Pakistan, both the 2% and 4% strengths of liquiritin cream outperformed hydroquinone on the basis of a Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) rating. The liquiritin cream was well tolerated in both studies.

Azelaic acid, tranexamic acid

OTC products containing azelaic acid are also effective for hyperpigmentation based on published trials in which they were compared with hydroquinone for treating melasma. In one study of 29 women with melasma cited by Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, 20% azelaic acid cream was more effective than hydroquinone 4% cream after 2 months of treatment on the basis of the mean MASI score (6.2 vs. 3.8).

The list also includes cysteamine, silymarin, and tranexamic acid.

In the case of tranexamic acid, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd cited a relatively recent study of 60 patients with melasma, comparing two strategies for applying tranexamic acid to treatment with hydroquinone over 12 weeks. Compared with 2% hydroquinone (applied nightly) or 1.8% liposomal tranexamic acid (applied twice a day), 5% tranexamic acid solution with microneedling (weekly) had a slightly greater rate of success defined as more than a 50% improvement in hyperpigmentation in an Asian population (30%, 27.8%, and 33.3%, respectively).

“Microneedling is a newer technology that appears to be effective at improving absorption,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. She predicts that microneedling will be used with increasing frequency in combination with topical cosmeceuticals.

She also predicted that these topical agents will be increasingly employed in combinations as the field of cosmeceuticals becomes increasingly more sophisticated. “When it comes to skin quality, cosmeceuticals remain our first-line therapy, especially in skin of color,” she said.

The rapid growth and utility of OTC cosmeceuticals is an area that dermatologists need to be following, according to Darius Mehregan, MD, chair of the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Detroit, who was senior author of an article published last year that reviewed the ingredients of popular OTC cosmeceuticals.

“Our patients have a great interest in cosmeceuticals and are looking to us for guidance. I think we have a responsibility to help them identify products supported by evidence and to warn them about potential side effects,” Dr. Mehregan, who was not at the meeting, said in an interview.

He agreed that the removal of hydroquinone from OTC products will create a specific need in the area of cosmeceuticals.

“Hydroquinone has for a long time been one of the most effective agents in OTC products for melasma, so patients are going to be looking for alternatives. Identifying which drugs have shown efficacy in controlled studies will be very helpful,” he said.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reports financial relationships with Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oréal, Galderma, Allergan, and Somabella Laboratories. Dr. Mehregan reports no potential conflicts of interest.

along with new strategies to improve their efficacy, according to a report at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ten or 15 years ago, I was showing a slide with five [alternatives to hydroquinone]. Now there are dozens,” reported Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, director of the skin of color division in the department of dermatology at the University of Miami.

The growth in alternatives to hydroquinone is timely. After threats to do so for more than a decade, the Food and Drug Administration finally banned hydroquinone from OTC products in 2020. The ban was folded into the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act passed in March of 2020 and then implemented the following September.

Until the ban of hydroquinone, OTC products with this compound were widely sought by many individuals with darker skin tones to self-treat melasma and other forms of hyperpigmentation, according to Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. Hydroquinone is still available in prescription products, but she is often asked for OTC alternatives, and she says the list is long and getting longer.

Niacinamide

Detailing the products she has been recommending most frequently as substitutes, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reported that several are supported by high quality studies. One example is niacinamide.

Of the several controlled studies she cited, one double-blind randomized trial found niacinamide to be equivalent to hydroquinone for melasma on the basis of colorimetric measures. The study compared 4% niacinamide cream applied on one side of the face with 4% hydroquinone cream applied on the other side in 27 patients with melasma. Although the proportion of responses rated good or excellent on a subjective basis was lower with niacinamide (44% vs. 55%), the difference was not statistically significant and niacinamide cream was clearly active, producing objective improvements in mast cell infiltrate and solar elastosis in melasma skin as well. Both were well tolerated.

In other studies, niacinamide has been shown to be effective in the treatment of melasma when combined with other active agents such as tranexamic acid, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who added that OTC products containing niacinamide are now “among my favorites” when directing patients to cosmeceuticals for hyperpigmentation.

Topical vitamin C

Topical vitamin C or ascorbic acid is another. Like niacinamide, topical vitamin C has also been compared with hydroquinone in a double-blind, randomized trial. Although the niacinamide trial and this study were performed 10 or more years ago, these data have new relevance with the ban of OTC hydroquinone.

In the study, 5% ascorbic acid cream on one side of the face was compared with 4% hydroquinone cream, applied on the other side, in 16 women with melasma. Again, there were no statistical differences in colorimetric measures, but good to excellent results were reported for 93% of the sides of the face treated with hydroquinone versus 62.5% of the sides treated with vitamin C (P < .05). “Hydroquinone performed better, but the vitamin C was active and very well tolerated,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said.

However, the ascorbic acid cream was better tolerated, with a far lower rate of adverse events (6.2% vs. 68.7%), an advantage that makes it easy to recommend to patients, said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, who now uses it frequently in her own practice.

Liquiritin, a licorice extract, is another lightening agent increasingly included in OTC products that she also recommends. In two older studies in medical journals published in Pakistan, both the 2% and 4% strengths of liquiritin cream outperformed hydroquinone on the basis of a Melasma Area and Severity Index (MASI) rating. The liquiritin cream was well tolerated in both studies.

Azelaic acid, tranexamic acid

OTC products containing azelaic acid are also effective for hyperpigmentation based on published trials in which they were compared with hydroquinone for treating melasma. In one study of 29 women with melasma cited by Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, 20% azelaic acid cream was more effective than hydroquinone 4% cream after 2 months of treatment on the basis of the mean MASI score (6.2 vs. 3.8).

The list also includes cysteamine, silymarin, and tranexamic acid.

In the case of tranexamic acid, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd cited a relatively recent study of 60 patients with melasma, comparing two strategies for applying tranexamic acid to treatment with hydroquinone over 12 weeks. Compared with 2% hydroquinone (applied nightly) or 1.8% liposomal tranexamic acid (applied twice a day), 5% tranexamic acid solution with microneedling (weekly) had a slightly greater rate of success defined as more than a 50% improvement in hyperpigmentation in an Asian population (30%, 27.8%, and 33.3%, respectively).

“Microneedling is a newer technology that appears to be effective at improving absorption,” said Dr. Woolery-Lloyd. She predicts that microneedling will be used with increasing frequency in combination with topical cosmeceuticals.

She also predicted that these topical agents will be increasingly employed in combinations as the field of cosmeceuticals becomes increasingly more sophisticated. “When it comes to skin quality, cosmeceuticals remain our first-line therapy, especially in skin of color,” she said.

The rapid growth and utility of OTC cosmeceuticals is an area that dermatologists need to be following, according to Darius Mehregan, MD, chair of the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Detroit, who was senior author of an article published last year that reviewed the ingredients of popular OTC cosmeceuticals.

“Our patients have a great interest in cosmeceuticals and are looking to us for guidance. I think we have a responsibility to help them identify products supported by evidence and to warn them about potential side effects,” Dr. Mehregan, who was not at the meeting, said in an interview.

He agreed that the removal of hydroquinone from OTC products will create a specific need in the area of cosmeceuticals.

“Hydroquinone has for a long time been one of the most effective agents in OTC products for melasma, so patients are going to be looking for alternatives. Identifying which drugs have shown efficacy in controlled studies will be very helpful,” he said.

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd reports financial relationships with Ortho Dermatologics, L’Oréal, Galderma, Allergan, and Somabella Laboratories. Dr. Mehregan reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM SOC 2021

Identify patient and hospital factors to reduce maternal mortality

Maternal mortality is a public health crisis for all women, said Elizabeth A. Howell, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in a presentation at the virtual Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

The maternal mortality rate in the United States in 2018 was 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Howell said. Maternal mortality is defined as death during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery; pregnancy-related mortality includes death during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy, from pregnancy or as a result of any cause related to, or aggravated by, pregnancy, according to the CDC.

However, “Black women are two to three times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause,” Dr. Howell said. These disparities are even more marked in some cities; data show that Black women in New York City are eight times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause, she noted.

Pregnancy-related mortality persists regardless of education level, and remains significantly higher in Black women, compared with White women with at least a college degree, Dr. Howell added.

In her presentation, Dr. Howell reviewed some top causes of maternal mortality overall, and potential factors driving disparities. Data from the CDC show cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular conditions, and preeclampsia/eclampsia as the top three underlying causes of pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic Black women, compared with mental health conditions, cardiovascular conditions, and hemorrhage in non-Hispanic White women, Dr. Howell said.

To help prevent maternal mortality across all populations, “It is important for us to think about the timing of deaths so we can better understand the causes,” said Dr. Howell.

CDC Vital Signs data show that approximately one-third of pregnancy-related deaths occur during pregnancy, but approximately 20% occur between 43 and 365 days postpartum, she said.

Although cardiovascular conditions top the list of clinical causes of pregnancy-related maternal mortality, maternal self-harm should not be discounted, and is likely underreported, Dr. Howell said. Data show that the peak incidence of maternal suicide occurs between 9 and 12 months’ postpartum, and risk factors include major depression, substance use disorder, and intimate partner violence, she noted.

Dr. Howell then shared the results of studies she conducted in 2020 and 2016 on racial disparities, hospital quality, and maternal mortality. One of her key findings in the 2020 study, presented at this year’s virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed that women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity, and an accompanying simulation/thought exercise showed that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately half of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women. An earlier study she published in 2016 of between-hospital differences in New York City showed that Black and Latina women were significantly more likely than White women to deliver in hospitals with higher rates of severe maternal mortality.

These findings illustrate that “racial segregation in neighborhoods is also part of the story,” of maternal mortality, Dr. Howell said.

Dr. Howell outlined ways the health care community can reduce severe maternal morbidity and mortality for all women, including promoting contraception and preconception health, improving postpartum management, eliminating bias, and using patient navigators as needed to enhance communication among the care team,

“Think about ways to engage the community,” in support of women’s pregnancy health, Dr. Howell said. She also emphasized the need to enroll more pregnant women in clinical trials.

Don’t exclude pregnant women from trials

In a follow-up session, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, expanded on opportunities to include pregnant women in clinical research.

Clinical trials for pregnant people fall into two categories, she noted; those studying interventions to improve pregnancy outcomes and those studying interventions for common medical conditions that coexist with pregnancy. These trials are either initiated by the investigators, conducted under contract, or federally funded, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Currently, the only obstetric clinical trials research network is the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, established in 1986 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The MFMU has conducted significant and life-saving research, but “we need more networks to focus on researching pregnancy complications,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Once the infrastructure exists in multiple settings, the ability to conduct trials will improve, she said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman stressed the need to engage and involve community-based physicians in clinical trials; using those relationships to enroll a more diverse population for whom working with their local physician would be more feasible than traveling to a larger clinical trial center.

She also commented on the need to include pregnant women in nonobstetric clinical trials. The exclusion of pregnant women from COVID-19 vaccine trials left clinicians with no information for guiding pregnant patients, she said. “It is important to think about why we are excluding pregnant women,” she said.

Finally, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman recommended a national effort to coordinate and leverage EHR data, which could have an effect on reducing maternal morbidity by facilitating the study of nonobstetric interventions in pregnancy, such as behavior interventions and mental health care.

Dr. Howell and Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Maternal mortality is a public health crisis for all women, said Elizabeth A. Howell, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in a presentation at the virtual Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

The maternal mortality rate in the United States in 2018 was 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Howell said. Maternal mortality is defined as death during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery; pregnancy-related mortality includes death during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy, from pregnancy or as a result of any cause related to, or aggravated by, pregnancy, according to the CDC.

However, “Black women are two to three times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause,” Dr. Howell said. These disparities are even more marked in some cities; data show that Black women in New York City are eight times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause, she noted.

Pregnancy-related mortality persists regardless of education level, and remains significantly higher in Black women, compared with White women with at least a college degree, Dr. Howell added.

In her presentation, Dr. Howell reviewed some top causes of maternal mortality overall, and potential factors driving disparities. Data from the CDC show cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular conditions, and preeclampsia/eclampsia as the top three underlying causes of pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic Black women, compared with mental health conditions, cardiovascular conditions, and hemorrhage in non-Hispanic White women, Dr. Howell said.

To help prevent maternal mortality across all populations, “It is important for us to think about the timing of deaths so we can better understand the causes,” said Dr. Howell.

CDC Vital Signs data show that approximately one-third of pregnancy-related deaths occur during pregnancy, but approximately 20% occur between 43 and 365 days postpartum, she said.

Although cardiovascular conditions top the list of clinical causes of pregnancy-related maternal mortality, maternal self-harm should not be discounted, and is likely underreported, Dr. Howell said. Data show that the peak incidence of maternal suicide occurs between 9 and 12 months’ postpartum, and risk factors include major depression, substance use disorder, and intimate partner violence, she noted.

Dr. Howell then shared the results of studies she conducted in 2020 and 2016 on racial disparities, hospital quality, and maternal mortality. One of her key findings in the 2020 study, presented at this year’s virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed that women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity, and an accompanying simulation/thought exercise showed that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately half of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women. An earlier study she published in 2016 of between-hospital differences in New York City showed that Black and Latina women were significantly more likely than White women to deliver in hospitals with higher rates of severe maternal mortality.

These findings illustrate that “racial segregation in neighborhoods is also part of the story,” of maternal mortality, Dr. Howell said.

Dr. Howell outlined ways the health care community can reduce severe maternal morbidity and mortality for all women, including promoting contraception and preconception health, improving postpartum management, eliminating bias, and using patient navigators as needed to enhance communication among the care team,

“Think about ways to engage the community,” in support of women’s pregnancy health, Dr. Howell said. She also emphasized the need to enroll more pregnant women in clinical trials.

Don’t exclude pregnant women from trials

In a follow-up session, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, expanded on opportunities to include pregnant women in clinical research.

Clinical trials for pregnant people fall into two categories, she noted; those studying interventions to improve pregnancy outcomes and those studying interventions for common medical conditions that coexist with pregnancy. These trials are either initiated by the investigators, conducted under contract, or federally funded, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Currently, the only obstetric clinical trials research network is the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, established in 1986 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The MFMU has conducted significant and life-saving research, but “we need more networks to focus on researching pregnancy complications,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Once the infrastructure exists in multiple settings, the ability to conduct trials will improve, she said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman stressed the need to engage and involve community-based physicians in clinical trials; using those relationships to enroll a more diverse population for whom working with their local physician would be more feasible than traveling to a larger clinical trial center.

She also commented on the need to include pregnant women in nonobstetric clinical trials. The exclusion of pregnant women from COVID-19 vaccine trials left clinicians with no information for guiding pregnant patients, she said. “It is important to think about why we are excluding pregnant women,” she said.

Finally, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman recommended a national effort to coordinate and leverage EHR data, which could have an effect on reducing maternal morbidity by facilitating the study of nonobstetric interventions in pregnancy, such as behavior interventions and mental health care.

Dr. Howell and Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Maternal mortality is a public health crisis for all women, said Elizabeth A. Howell, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in a presentation at the virtual Advancing NIH Research on the Health of Women conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.

The maternal mortality rate in the United States in 2018 was 17.4 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Howell said. Maternal mortality is defined as death during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery; pregnancy-related mortality includes death during pregnancy or within 1 year of pregnancy, from pregnancy or as a result of any cause related to, or aggravated by, pregnancy, according to the CDC.

However, “Black women are two to three times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause,” Dr. Howell said. These disparities are even more marked in some cities; data show that Black women in New York City are eight times more likely than White women to die from a pregnancy-related cause, she noted.

Pregnancy-related mortality persists regardless of education level, and remains significantly higher in Black women, compared with White women with at least a college degree, Dr. Howell added.

In her presentation, Dr. Howell reviewed some top causes of maternal mortality overall, and potential factors driving disparities. Data from the CDC show cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular conditions, and preeclampsia/eclampsia as the top three underlying causes of pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic Black women, compared with mental health conditions, cardiovascular conditions, and hemorrhage in non-Hispanic White women, Dr. Howell said.

To help prevent maternal mortality across all populations, “It is important for us to think about the timing of deaths so we can better understand the causes,” said Dr. Howell.

CDC Vital Signs data show that approximately one-third of pregnancy-related deaths occur during pregnancy, but approximately 20% occur between 43 and 365 days postpartum, she said.

Although cardiovascular conditions top the list of clinical causes of pregnancy-related maternal mortality, maternal self-harm should not be discounted, and is likely underreported, Dr. Howell said. Data show that the peak incidence of maternal suicide occurs between 9 and 12 months’ postpartum, and risk factors include major depression, substance use disorder, and intimate partner violence, she noted.

Dr. Howell then shared the results of studies she conducted in 2020 and 2016 on racial disparities, hospital quality, and maternal mortality. One of her key findings in the 2020 study, presented at this year’s virtual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, showed that women delivering in the lowest-ranked hospitals had six times the rate of severe maternal morbidity, and an accompanying simulation/thought exercise showed that the hospital of delivery accounted for approximately half of the disparity in severe maternal morbidity between Black and White women. An earlier study she published in 2016 of between-hospital differences in New York City showed that Black and Latina women were significantly more likely than White women to deliver in hospitals with higher rates of severe maternal mortality.

These findings illustrate that “racial segregation in neighborhoods is also part of the story,” of maternal mortality, Dr. Howell said.

Dr. Howell outlined ways the health care community can reduce severe maternal morbidity and mortality for all women, including promoting contraception and preconception health, improving postpartum management, eliminating bias, and using patient navigators as needed to enhance communication among the care team,

“Think about ways to engage the community,” in support of women’s pregnancy health, Dr. Howell said. She also emphasized the need to enroll more pregnant women in clinical trials.

Don’t exclude pregnant women from trials

In a follow-up session, Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of the University of California, San Diego, expanded on opportunities to include pregnant women in clinical research.

Clinical trials for pregnant people fall into two categories, she noted; those studying interventions to improve pregnancy outcomes and those studying interventions for common medical conditions that coexist with pregnancy. These trials are either initiated by the investigators, conducted under contract, or federally funded, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Currently, the only obstetric clinical trials research network is the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, established in 1986 by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The MFMU has conducted significant and life-saving research, but “we need more networks to focus on researching pregnancy complications,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Once the infrastructure exists in multiple settings, the ability to conduct trials will improve, she said.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman stressed the need to engage and involve community-based physicians in clinical trials; using those relationships to enroll a more diverse population for whom working with their local physician would be more feasible than traveling to a larger clinical trial center.

She also commented on the need to include pregnant women in nonobstetric clinical trials. The exclusion of pregnant women from COVID-19 vaccine trials left clinicians with no information for guiding pregnant patients, she said. “It is important to think about why we are excluding pregnant women,” she said.

Finally, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman recommended a national effort to coordinate and leverage EHR data, which could have an effect on reducing maternal morbidity by facilitating the study of nonobstetric interventions in pregnancy, such as behavior interventions and mental health care.

Dr. Howell and Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ADVANCING NIH RESEARCH ON THE HEALTH OF WOMEN

Transgender use of dermatologic procedures has strong gender tilt

, according to the results of a recent survey.

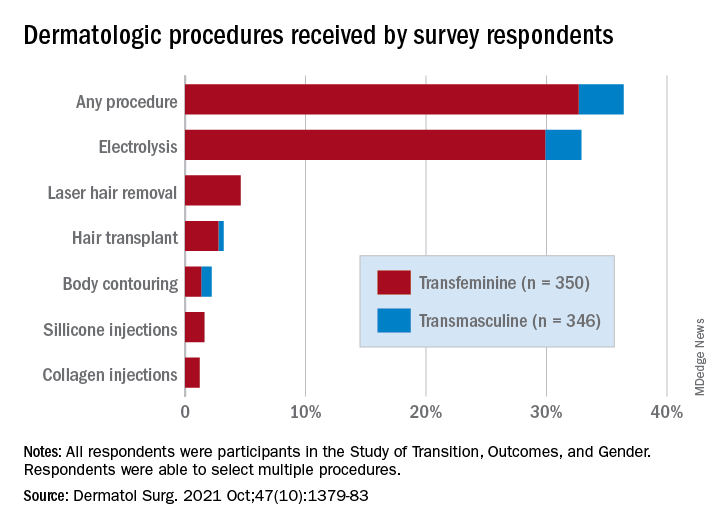

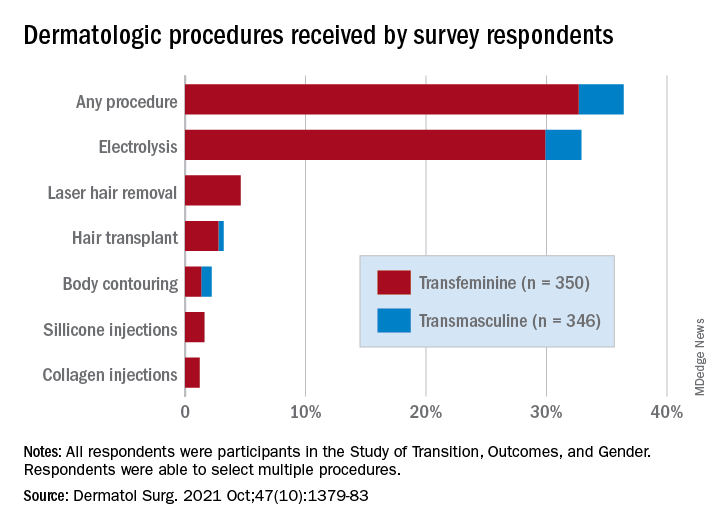

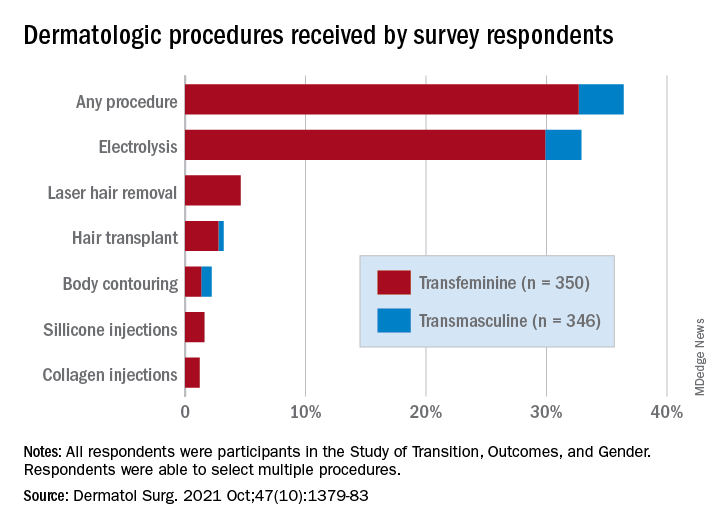

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

, according to the results of a recent survey.

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

, according to the results of a recent survey.

Transfeminine persons – those assigned male at birth – were much more likely to report a previous dermatologic procedure, compared with transmasculine respondents, by a margin of 64.9%-7.5%, Laura Ragmanauskaite, MD, and associates reported.

“Hair removal was the most frequently reported procedure type, with electrolysis being more common than laser hair removal,” they said, noting that “previous research on hair removal treatments among gender minority persons did not detect differences in the use of electrolysis and laser hair removal.”

Just under one-third of all respondents (32.9%) said that they had undergone electrolysis and 4.6% reported previous laser hair removal. For electrolysis, that works out to 59.4% of transfeminine and 6.1% of transmasculine respondents, while 9.1% of all transfeminine and no transmasculine persons had received laser hair removal, Dr. Ragmanauskaite of the department of dermatology, Emory University, Atlanta, and her coauthors said.

Those who had undergone gender-affirming surgery were significantly more likely to report electrolysis (78.6%) than were persons who had received no gender-affirming surgery or hormone therapy alone (47.4%), a statistically significant difference (P < .01). All of the other, less common procedures included in the online survey – 696 responses were received from 350 transfeminine and 346 transmasculine persons participating in the Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender – were reported more often by the transfeminine respondents. The procedure with the closest gender distribution was body contouring, reported by nine transfeminine and six transmasculine persons, the researchers said.

Use of dermal fillers was even less common (2.8% among all respondents, all transfeminine persons), with just 11 reporting having received silicone and 8 reporting having received collagen, although the survey did not ask about how the injections were obtained. In a previous study, the prevalence of illicit filler injection in transgender women was 16.9%, they pointed out.

These types of noninvasive, gender-affirming procedures “may contribute to higher levels of self-confidence and [reduce] gender dysphoria. Future studies should examine motivations, barriers, and optimal timing” for such procedures in transgender persons, Dr. Ragmanauskaite and associates wrote.

The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Social determinants of health may drive CVD risk in Black Americans

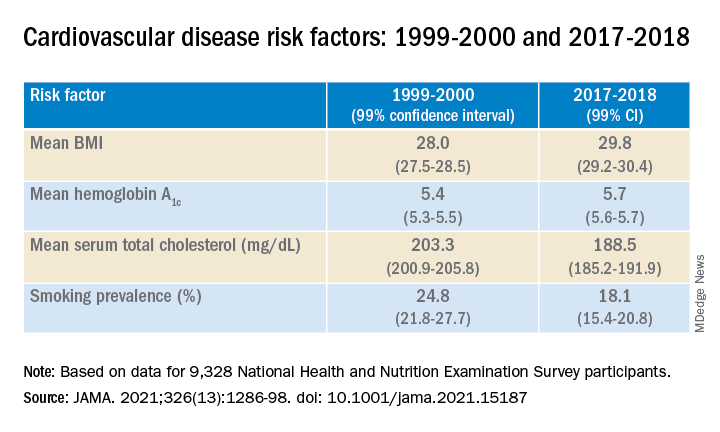

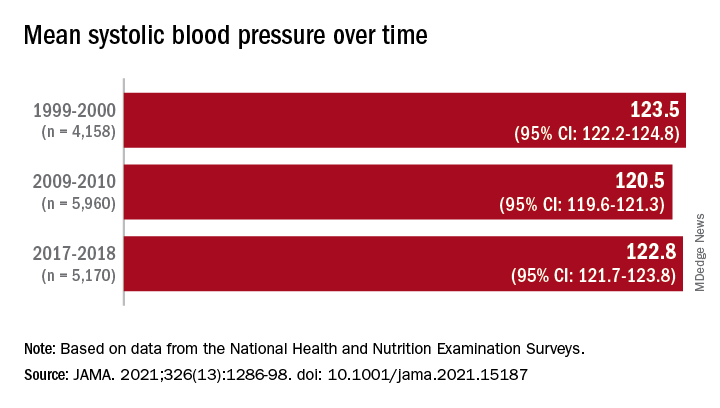

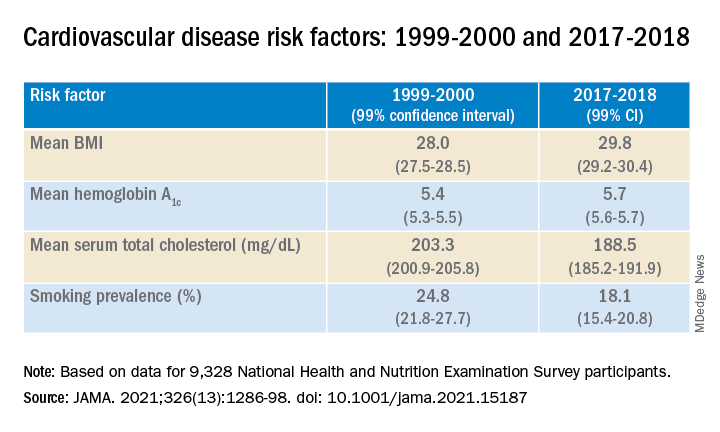

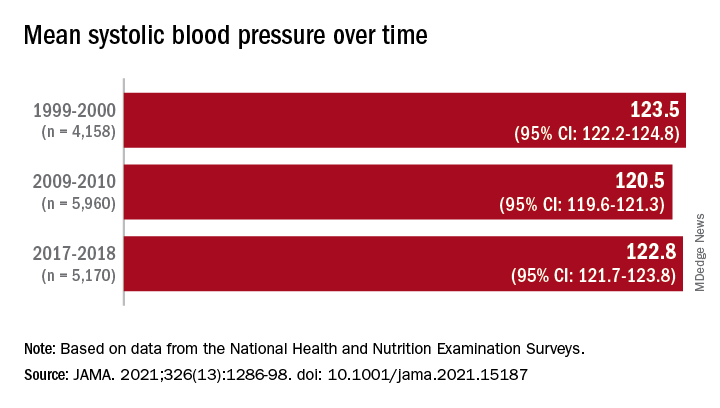

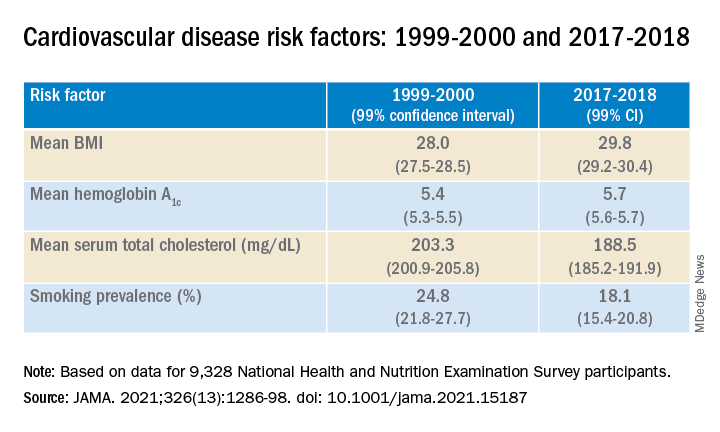

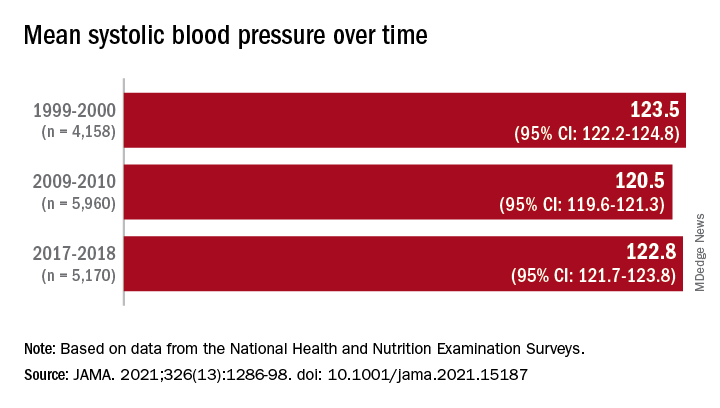

Investigators analyzed 20 years of data on over 50,500 U.S. adults drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) and found that, in the overall population, body mass index and hemoglobin A1c were significantly increased between 1999 and 2018, while serum total cholesterol and cigarette smoking were significantly decreased. Mean systolic blood pressure decreased between 1999 and 2010, but then increased after 2010.

The mean age- and sex-adjusted estimated 10-year risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was consistently higher in Black participants vs. White participants, but the difference was attenuated after further adjusting for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

“These findings are helpful to guide the development of national public health policies for targeted interventions aimed at eliminating health disparities,” Jiang He, MD, PhD, Joseph S. Copes Chair and professor of epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, said in an interview.

“Interventions on social determinants of cardiovascular health should be tested in rigorous designed intervention trials,” said Dr. He, director of the Tulane University Translational Science Institute.

The study was published online Oct. 5 in JAMA.

‘Flattened’ CVD mortality?

Recent data show that the CVD mortality rate flattened, while the total number of cardiovascular deaths increased in the U.S. general population from 2010 to 2018, “but the reasons for this deceleration in the decline of CVD mortality are not entirely understood,” Dr. He said.

Moreover, “racial and ethnic differences in CVD mortality persist in the U.S. general population [but] the secular trends of cardiovascular risk factors among U.S. subpopulations with various racial and ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic status are [also] not well understood,” he added. The effects of social determinants of health, such as education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care on racial/ethnic differences in CVD risk, “are not well documented.”

To investigate these questions, the researchers drew on data from NHANES, a series of cross-sectional surveys in nationally representative samples of the U.S. population aged 20 years and older. The surveys are conducted in 2-year cycles and include data from 10 cycles conducted from 1999-2000 to 2017-2018 (n = 50,571, mean age 49.0-51.8 years; 48.2%-51.3% female).

Every 2 years, participants provided sociodemographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, income, employment, housing, health insurance, and access to health care, as well as medical history and medication use. They underwent a physical examination that included weight and height, blood pressure, lipid levels, plasma glucose, and hemoglobin A1c.

Social determinants of health

Between 1999-2000 and 2017-2018, age- and sex-adjusted mean BMI and hemoglobin A1c increased, while mean serum total cholesterol and prevalence of smoking decreased (all P < .001).

Age- and sex-adjusted 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk decreased from 7.6% (6.9%-8.2%) in 1999-2000 to 6.5% (6.1%-6.8%) in 2011-2012, with no significant changes thereafter.

When the researchers looked at specific racial and ethnic groups, they found that age- and sex-adjusted BMI, systolic BP, and hemoglobin A1c were “consistently higher” in non-Hispanic Black participants compared with non-Hispanic White participants, but total cholesterol was lower (all P < .001).

Participants with at least a college education or high family income had “consistently lower levels” of cardiovascular risk factors. And although the mean age- and sex-adjusted 10-year risk for ASCVD was significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black vs. non-Hispanic White participants (difference, 1.4% [1.0%-1.7%] in 1999-2008 and 2.0% [1.7%-2.4%] in 2009-2018), the difference was attenuated (by –0.3% in 1999-2008 and 0.7% in 2009-2018) after the researchers further adjusted for education, income, home ownership, employment, health insurance, and access to health care.

The differences in cardiovascular risk factors between Black and White participants “may have been moderated by social determinants of health,” the authors noted.

Provide appropriate education

Commenting on the study in an interview, Mary Ann McLaughlin, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine, cardiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, pointed out that two important cardiovascular risk factors associated with being overweight – hypertension and diabetes – remained higher in the Black population compared with the White population in this analysis.

“Physicians and health care systems should provide appropriate education and resources regarding risk factor modification regarding diet, exercise, and blood pressure control,” advised Dr. McLaughlin, who was not involved with the study.

“Importantly, smoking rates and cholesterol levels are lower in the Black population, compared to the White population, when adjusted for many important socioeconomic factors,” she pointed out.

Dr. McLaughlin added that other “important social determinants of health, such as neighborhood and access to healthy food, were not measured and should be addressed by physicians when optimizing cardiovascular risk.”