User login

Hospitals must identify and empower women leaders

Many potential leaders in academic medicine go unidentified, and finding those leaders is key to improving gender equity in academic medicine, said Nancy Spector, MD, in a presentation at the virtual Advance PHM Gender Equity Conference.

“I think it is important to reframe what it means to be a leader, and to empower yourself to think of yourself as a leader,” said Dr. Spector, executive director for executive leadership in academic medicine program at Drexel University, Philadelphia.

“Some of the best leaders I know do not have titles,” she emphasized.

Steps to stimulate the system changes needed to promote gender equity include building policies around the life cycle, revising departmental and division governance, and tracking metrics at the individual, departmental, and organizational level, Dr. Spector said.

Aligning gender-equity efforts with institutional priorities and navigating politics to effect changes in the gender equity landscape are ongoing objectives, she said.

Dr. Spector offered advice to men and women looking to shift the system and promote gender equity. She emphasized the challenge of overcoming psychological associations of men and women in leadership roles. “Men are more often associated with agentic qualities, which convey assertion and control,” she said. Men in leadership are more often described as aggressive, ambitious, dominant, self-confident, forceful, self-reliant, and individualistic.

By contrast, “women are associated with communal qualities, which convey a concern for compassionate treatment of others,” and are more often described as affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, sensitive, gentle, and well spoken, she noted.

Although agentic traits are most often associated with effective leadership, in fact, “the most effective contemporary leaders have both agentic and communal traits,” said Dr. Spector.

However, “if a woman leader is very communal, she may be viewed as not assertive enough, and it she is highly agentic, she is criticized for being too domineering or controlling,” she said.

To help get past these associations, changes are needed at the individual level, leader level, and institutional level, Dr. Spector said.

On the individual level, women seeking to improve the situation for gender equity should engage with male allies and build a pipeline of mentorship and sponsorship to help identify future leaders, she said.

Women and men should obtain leadership training, and “become a student of leadership,” she advised. “Be in a learning mode,” and then think how to apply what you have learned, which may include setting challenging learning goals, experimenting with alternative strategies, learning about different leadership styles, and learning about differences in leaders’ values and attitudes.

For women, being pulled in many directions is the norm. “Are you being strategic with how you serve on committees?” Dr. Spector asked.

Make the most of how you choose to share your time, and “garner the skill of graceful self-promotion, which is often a hard skill for women,” she noted. She also urged women to make the most of professional networking and social capital.

At the leader level, the advice Dr. Spector offered to leaders on building gender equity in their institutions include ensuring a critical mass of women in leadership track positions. “Avoid having a sole woman member of a team,” she said.

Dr. Spector also emphasized the importance of giving employees with family responsibilities more time for promotion, and welcoming back women who step away from the workforce and choose to return. Encourage men to participate in family-friendly benefits. “Standardize processes that support the life cycle of a faculty member or the person you’re hiring,” and ensure inclusive times and venues for major meetings, committee work, and social events, she added.

Dr. Spector’s strategies for institutions include quantifying disparities by using real time dashboards to show both leading and lagging indicators, setting goals, and measuring achievements.

“Create an infrastructure to support women’s leadership,” she said. Such an infrastructure could include not only robust committees for women in science and medicine, but also supporting women to attend leadership training both inside and outside their institutions.

Dr. Spector noted that professional organizations also have a role to play in support of women’s leadership.

“Make a public pledge to gender equity,” she said. She encouraged professional organizations to tie diversity and inclusion metrics to performance reviews, and to prioritize the examination and mitigation of disparities, and report challenges and successes.

When creating policies to promote gender equity, “get out of your silo,” Dr. Spector emphasized. Understand the drivers rather than simply judging the behaviors.

“Even if we disagree on something, we need to work together, and empower everyone to be thoughtful drivers of change,” she concluded.

Dr. Spector disclosed grant funding from the Department of Health & Human Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She also disclosed receiving monetary awards, honoraria, and travel reimbursement from multiple academic and professional organization for teaching and consulting programs. Dr. Spector also cofunded and holds equity interest in the I-PASS Patient Safety Institute, a company created to assist institutions in implementing the I-PASS Handoff Program.

Many potential leaders in academic medicine go unidentified, and finding those leaders is key to improving gender equity in academic medicine, said Nancy Spector, MD, in a presentation at the virtual Advance PHM Gender Equity Conference.

“I think it is important to reframe what it means to be a leader, and to empower yourself to think of yourself as a leader,” said Dr. Spector, executive director for executive leadership in academic medicine program at Drexel University, Philadelphia.

“Some of the best leaders I know do not have titles,” she emphasized.

Steps to stimulate the system changes needed to promote gender equity include building policies around the life cycle, revising departmental and division governance, and tracking metrics at the individual, departmental, and organizational level, Dr. Spector said.

Aligning gender-equity efforts with institutional priorities and navigating politics to effect changes in the gender equity landscape are ongoing objectives, she said.

Dr. Spector offered advice to men and women looking to shift the system and promote gender equity. She emphasized the challenge of overcoming psychological associations of men and women in leadership roles. “Men are more often associated with agentic qualities, which convey assertion and control,” she said. Men in leadership are more often described as aggressive, ambitious, dominant, self-confident, forceful, self-reliant, and individualistic.

By contrast, “women are associated with communal qualities, which convey a concern for compassionate treatment of others,” and are more often described as affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, sensitive, gentle, and well spoken, she noted.

Although agentic traits are most often associated with effective leadership, in fact, “the most effective contemporary leaders have both agentic and communal traits,” said Dr. Spector.

However, “if a woman leader is very communal, she may be viewed as not assertive enough, and it she is highly agentic, she is criticized for being too domineering or controlling,” she said.

To help get past these associations, changes are needed at the individual level, leader level, and institutional level, Dr. Spector said.

On the individual level, women seeking to improve the situation for gender equity should engage with male allies and build a pipeline of mentorship and sponsorship to help identify future leaders, she said.

Women and men should obtain leadership training, and “become a student of leadership,” she advised. “Be in a learning mode,” and then think how to apply what you have learned, which may include setting challenging learning goals, experimenting with alternative strategies, learning about different leadership styles, and learning about differences in leaders’ values and attitudes.

For women, being pulled in many directions is the norm. “Are you being strategic with how you serve on committees?” Dr. Spector asked.

Make the most of how you choose to share your time, and “garner the skill of graceful self-promotion, which is often a hard skill for women,” she noted. She also urged women to make the most of professional networking and social capital.

At the leader level, the advice Dr. Spector offered to leaders on building gender equity in their institutions include ensuring a critical mass of women in leadership track positions. “Avoid having a sole woman member of a team,” she said.

Dr. Spector also emphasized the importance of giving employees with family responsibilities more time for promotion, and welcoming back women who step away from the workforce and choose to return. Encourage men to participate in family-friendly benefits. “Standardize processes that support the life cycle of a faculty member or the person you’re hiring,” and ensure inclusive times and venues for major meetings, committee work, and social events, she added.

Dr. Spector’s strategies for institutions include quantifying disparities by using real time dashboards to show both leading and lagging indicators, setting goals, and measuring achievements.

“Create an infrastructure to support women’s leadership,” she said. Such an infrastructure could include not only robust committees for women in science and medicine, but also supporting women to attend leadership training both inside and outside their institutions.

Dr. Spector noted that professional organizations also have a role to play in support of women’s leadership.

“Make a public pledge to gender equity,” she said. She encouraged professional organizations to tie diversity and inclusion metrics to performance reviews, and to prioritize the examination and mitigation of disparities, and report challenges and successes.

When creating policies to promote gender equity, “get out of your silo,” Dr. Spector emphasized. Understand the drivers rather than simply judging the behaviors.

“Even if we disagree on something, we need to work together, and empower everyone to be thoughtful drivers of change,” she concluded.

Dr. Spector disclosed grant funding from the Department of Health & Human Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She also disclosed receiving monetary awards, honoraria, and travel reimbursement from multiple academic and professional organization for teaching and consulting programs. Dr. Spector also cofunded and holds equity interest in the I-PASS Patient Safety Institute, a company created to assist institutions in implementing the I-PASS Handoff Program.

Many potential leaders in academic medicine go unidentified, and finding those leaders is key to improving gender equity in academic medicine, said Nancy Spector, MD, in a presentation at the virtual Advance PHM Gender Equity Conference.

“I think it is important to reframe what it means to be a leader, and to empower yourself to think of yourself as a leader,” said Dr. Spector, executive director for executive leadership in academic medicine program at Drexel University, Philadelphia.

“Some of the best leaders I know do not have titles,” she emphasized.

Steps to stimulate the system changes needed to promote gender equity include building policies around the life cycle, revising departmental and division governance, and tracking metrics at the individual, departmental, and organizational level, Dr. Spector said.

Aligning gender-equity efforts with institutional priorities and navigating politics to effect changes in the gender equity landscape are ongoing objectives, she said.

Dr. Spector offered advice to men and women looking to shift the system and promote gender equity. She emphasized the challenge of overcoming psychological associations of men and women in leadership roles. “Men are more often associated with agentic qualities, which convey assertion and control,” she said. Men in leadership are more often described as aggressive, ambitious, dominant, self-confident, forceful, self-reliant, and individualistic.

By contrast, “women are associated with communal qualities, which convey a concern for compassionate treatment of others,” and are more often described as affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, sensitive, gentle, and well spoken, she noted.

Although agentic traits are most often associated with effective leadership, in fact, “the most effective contemporary leaders have both agentic and communal traits,” said Dr. Spector.

However, “if a woman leader is very communal, she may be viewed as not assertive enough, and it she is highly agentic, she is criticized for being too domineering or controlling,” she said.

To help get past these associations, changes are needed at the individual level, leader level, and institutional level, Dr. Spector said.

On the individual level, women seeking to improve the situation for gender equity should engage with male allies and build a pipeline of mentorship and sponsorship to help identify future leaders, she said.

Women and men should obtain leadership training, and “become a student of leadership,” she advised. “Be in a learning mode,” and then think how to apply what you have learned, which may include setting challenging learning goals, experimenting with alternative strategies, learning about different leadership styles, and learning about differences in leaders’ values and attitudes.

For women, being pulled in many directions is the norm. “Are you being strategic with how you serve on committees?” Dr. Spector asked.

Make the most of how you choose to share your time, and “garner the skill of graceful self-promotion, which is often a hard skill for women,” she noted. She also urged women to make the most of professional networking and social capital.

At the leader level, the advice Dr. Spector offered to leaders on building gender equity in their institutions include ensuring a critical mass of women in leadership track positions. “Avoid having a sole woman member of a team,” she said.

Dr. Spector also emphasized the importance of giving employees with family responsibilities more time for promotion, and welcoming back women who step away from the workforce and choose to return. Encourage men to participate in family-friendly benefits. “Standardize processes that support the life cycle of a faculty member or the person you’re hiring,” and ensure inclusive times and venues for major meetings, committee work, and social events, she added.

Dr. Spector’s strategies for institutions include quantifying disparities by using real time dashboards to show both leading and lagging indicators, setting goals, and measuring achievements.

“Create an infrastructure to support women’s leadership,” she said. Such an infrastructure could include not only robust committees for women in science and medicine, but also supporting women to attend leadership training both inside and outside their institutions.

Dr. Spector noted that professional organizations also have a role to play in support of women’s leadership.

“Make a public pledge to gender equity,” she said. She encouraged professional organizations to tie diversity and inclusion metrics to performance reviews, and to prioritize the examination and mitigation of disparities, and report challenges and successes.

When creating policies to promote gender equity, “get out of your silo,” Dr. Spector emphasized. Understand the drivers rather than simply judging the behaviors.

“Even if we disagree on something, we need to work together, and empower everyone to be thoughtful drivers of change,” she concluded.

Dr. Spector disclosed grant funding from the Department of Health & Human Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She also disclosed receiving monetary awards, honoraria, and travel reimbursement from multiple academic and professional organization for teaching and consulting programs. Dr. Spector also cofunded and holds equity interest in the I-PASS Patient Safety Institute, a company created to assist institutions in implementing the I-PASS Handoff Program.

FROM THE ADVANCE PHM GENDER EQUITY CONFERENCE

Racism a strong factor in Black women’s high rate of premature births, study finds

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Dr. Paula Braveman, director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, says her latest research revealed an “astounding” level of evidence that racism is a decisive “upstream” cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women.

The tipping point for Dr. Paula Braveman came when a longtime patient of hers at a community clinic in San Francisco’s Mission District slipped past the front desk and knocked on her office door to say goodbye. He wouldn’t be coming to the clinic anymore, he told her, because he could no longer afford it.

It was a decisive moment for Dr. Braveman, who decided she wanted not only to heal ailing patients but also to advocate for policies that would help them be healthier when they arrived at her clinic. In the nearly four decades since, Dr. Braveman has dedicated herself to studying the “social determinants of health” – how the spaces where we live, work, play and learn, and the relationships we have in those places influence how healthy we are.

As director of the Center on Social Disparities in Health at the University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Braveman has studied the link between neighborhood wealth and children’s health, and how access to insurance influences prenatal care. A longtime advocate of translating research into policy, she has collaborated on major health initiatives with the health department in San Francisco, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization.

Dr. Braveman has a particular interest in maternal and infant health. Her latest research reviews what’s known about the persistent gap in preterm birth rates between Black and White women in the United States. Black women are about 1.6 times as likely as White women to give birth more than three weeks before the due date. That statistic bears alarming and costly health consequences, as infants born prematurely are at higher risk for breathing, heart, and brain abnormalities, among other complications.

Dr. Braveman coauthored the review with a group of experts convened by the March of Dimes that included geneticists, clinicians, epidemiologists, biomedical experts, and neurologists. They examined more than two dozen suspected causes of preterm births – including quality of prenatal care, environmental toxics, chronic stress, poverty and obesity – and determined that racism, directly or indirectly, best explained the racial disparities in preterm birth rates.

(Note: In the review, the authors make extensive use of the terms “upstream” and “downstream” to describe what determines people’s health. A downstream risk is the condition or factor most directly responsible for a health outcome, while an upstream factor is what causes or fuels the downstream risk – and often what needs to change to prevent someone from becoming sick. For example, a person living near drinking water polluted with toxic chemicals might get sick from drinking the water. The downstream fix would be telling individuals to use filters. The upstream solution would be to stop the dumping of toxic chemicals.)

KHN spoke with Dr. Braveman about the study and its findings. The excerpts have been edited for length and style.

Q: You have been studying the issue of preterm birth and racial disparities for so long. Were there any findings from this review that surprised you?

The process of systematically going through all of the risk factors that are written about in the literature and then seeing how the story of racism was an upstream determinant for virtually all of them. That was kind of astounding.

The other thing that was very impressive: When we looked at the idea that genetic factors could be the cause of the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. The genetics experts in the group, and there were three or four of them, concluded from the evidence that genetic factors might influence the disparity in preterm birth, but at most the effect would be very small, very small indeed. This could not account for the greater rate of preterm birth among Black women compared to White women.

Q: You were looking to identify not just what causes preterm birth but also to explain racial differences in rates of preterm birth. Are there examples of factors that can influence preterm birth that don’t explain racial disparities?

It does look like there are genetic components to preterm birth, but they don’t explain the Black-White disparity in preterm birth. Another example is having an early elective C-section. That’s one of the problems contributing to avoidable preterm birth, but it doesn’t look like that’s really contributing to the Black-White disparity in preterm birth.

Q: You and your colleagues listed exactly one upstream cause of preterm birth: racism. How would you characterize the certainty that racism is a decisive upstream cause of higher rates of preterm birth among Black women?

It makes me think of this saying: A randomized clinical trial wouldn’t be necessary to give certainty about the importance of having a parachute on if you jump from a plane. To me, at this point, it is close to that.

Going through that paper – and we worked on that paper over a three- or four-year period, so there was a lot of time to think about it – I don’t see how the evidence that we have could be explained otherwise.

Q: What did you learn about how a mother’s broader lifetime experience of racism might affect birth outcomes versus what she experienced within the medical establishment during pregnancy?

There were many ways that experiencing racial discrimination would affect a woman’s pregnancy, but one major way would be through pathways and biological mechanisms involved in stress and stress physiology. In neuroscience, what’s been clear is that a chronic stressor seems to be more damaging to health than an acute stressor.

So it doesn’t make much sense to be looking only during pregnancy. But that’s where most of that research has been done: stress during pregnancy and racial discrimination, and its role in birth outcomes. Very few studies have looked at experiences of racial discrimination across the life course.

My colleagues and I have published a paper where we asked African American women about their experiences of racism, and we didn’t even define what we meant. Women did not talk a lot about the experiences of racism during pregnancy from their medical providers; they talked about the lifetime experience and particularly experiences going back to childhood. And they talked about having to worry, and constant vigilance, so that even if they’re not experiencing an incident, their antennae have to be out to be prepared in case an incident does occur.

Putting all of it together with what we know about stress physiology, I would put my money on the lifetime experiences being so much more important than experiences during pregnancy. There isn’t enough known about preterm birth, but from what is known, inflammation is involved, immune dysfunction, and that’s what stress leads to. The neuroscientists have shown us that chronic stress produces inflammation and immune system dysfunction.

Q: What policies do you think are most important at this stage for reducing preterm birth for Black women?

I wish I could just say one policy or two policies, but I think it does get back to the need to dismantle racism in our society. In all of its manifestations. That’s unfortunate, not to be able to say, “Oh, here, I have this magic bullet, and if you just go with that, that will solve the problem.”

If you take the conclusions of this study seriously, you say, well, policies to just go after these downstream factors are not going to work. It’s up to the upstream investment in trying to achieve a more equitable and less racist society. Ultimately, I think that’s the take-home, and it’s a tall, tall order.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Tolerance in medicine

There is a narrative being pushed now about health care professionals being “frustrated” and “tired” in the midst of this current delta COVID wave. This stems from the idea that this current wave was potentially preventable if everyone received the COVID vaccines when they were made available.

I certainly understand this frustration and am tired of dealing with COVID restrictions and wearing masks. Above all I’m tired of talking about it. But frustration and fatigue are nothing new for those in the health care profession. Part of our training is that we should care for everyone, no matter what. Compassion for the ill should not be restricted to patients with a certain financial status, immigration status, race, gender, sexual orientation, or education level. Socially and politically, we are having a reckoning with how we treat people and how we need to do better to create a more just society. A key virtue in all of this is tolerance.

If we are going to have a free society, tolerance is essential. This is because in a free society people are going to, well, be free. In medicine we tolerate people who are morbidly obese, drink alcohol excessively, smoke, refuse to take their medications, won’t exercise, won’t sleep, and do drugs. The overwhelming majority of these people know that what they are doing is bad for their health. Not only do we tolerate them, we are taught to treat them indiscriminately. When someone who is morbidly obese has a heart attack, we treat them, give them medicine, and tell them the importance of losing weight. We do not tell them, “you shouldn’t have eaten so much and gotten so fat,” or “don’t you wish you didn’t get so fat?”

What I am trying to circle back to here is that if you could force people into doing everything they could for their health and eliminate all “preventable” diseases, then the need for health care in this country – including doctors, nurses, hospitals, and pharmaceuticals, just to name a few – would be cut dramatically. While the frustration for the continued COVID surges is understandable, I urge people to remember that in the business of health care we deal with preventable diseases all the time, every day. We are taught to show compassion for everyone, and for good reason. We have no idea what many people’s backstories are, we just know that they are sick and need help.

I urge everyone to put the unvaccinated under the same umbrella you put other people with preventable diseases, which, sadly, is a lot of patients. Continue to educate those about the vaccine as you should about every other aspect of their health. Education is part of our job as health care professionals but judgment is not.

Dr. Matuszak works for Sound Physicians and is a nocturnist at a hospital in the San Francisco Bay Area.

There is a narrative being pushed now about health care professionals being “frustrated” and “tired” in the midst of this current delta COVID wave. This stems from the idea that this current wave was potentially preventable if everyone received the COVID vaccines when they were made available.

I certainly understand this frustration and am tired of dealing with COVID restrictions and wearing masks. Above all I’m tired of talking about it. But frustration and fatigue are nothing new for those in the health care profession. Part of our training is that we should care for everyone, no matter what. Compassion for the ill should not be restricted to patients with a certain financial status, immigration status, race, gender, sexual orientation, or education level. Socially and politically, we are having a reckoning with how we treat people and how we need to do better to create a more just society. A key virtue in all of this is tolerance.

If we are going to have a free society, tolerance is essential. This is because in a free society people are going to, well, be free. In medicine we tolerate people who are morbidly obese, drink alcohol excessively, smoke, refuse to take their medications, won’t exercise, won’t sleep, and do drugs. The overwhelming majority of these people know that what they are doing is bad for their health. Not only do we tolerate them, we are taught to treat them indiscriminately. When someone who is morbidly obese has a heart attack, we treat them, give them medicine, and tell them the importance of losing weight. We do not tell them, “you shouldn’t have eaten so much and gotten so fat,” or “don’t you wish you didn’t get so fat?”

What I am trying to circle back to here is that if you could force people into doing everything they could for their health and eliminate all “preventable” diseases, then the need for health care in this country – including doctors, nurses, hospitals, and pharmaceuticals, just to name a few – would be cut dramatically. While the frustration for the continued COVID surges is understandable, I urge people to remember that in the business of health care we deal with preventable diseases all the time, every day. We are taught to show compassion for everyone, and for good reason. We have no idea what many people’s backstories are, we just know that they are sick and need help.

I urge everyone to put the unvaccinated under the same umbrella you put other people with preventable diseases, which, sadly, is a lot of patients. Continue to educate those about the vaccine as you should about every other aspect of their health. Education is part of our job as health care professionals but judgment is not.

Dr. Matuszak works for Sound Physicians and is a nocturnist at a hospital in the San Francisco Bay Area.

There is a narrative being pushed now about health care professionals being “frustrated” and “tired” in the midst of this current delta COVID wave. This stems from the idea that this current wave was potentially preventable if everyone received the COVID vaccines when they were made available.

I certainly understand this frustration and am tired of dealing with COVID restrictions and wearing masks. Above all I’m tired of talking about it. But frustration and fatigue are nothing new for those in the health care profession. Part of our training is that we should care for everyone, no matter what. Compassion for the ill should not be restricted to patients with a certain financial status, immigration status, race, gender, sexual orientation, or education level. Socially and politically, we are having a reckoning with how we treat people and how we need to do better to create a more just society. A key virtue in all of this is tolerance.

If we are going to have a free society, tolerance is essential. This is because in a free society people are going to, well, be free. In medicine we tolerate people who are morbidly obese, drink alcohol excessively, smoke, refuse to take their medications, won’t exercise, won’t sleep, and do drugs. The overwhelming majority of these people know that what they are doing is bad for their health. Not only do we tolerate them, we are taught to treat them indiscriminately. When someone who is morbidly obese has a heart attack, we treat them, give them medicine, and tell them the importance of losing weight. We do not tell them, “you shouldn’t have eaten so much and gotten so fat,” or “don’t you wish you didn’t get so fat?”

What I am trying to circle back to here is that if you could force people into doing everything they could for their health and eliminate all “preventable” diseases, then the need for health care in this country – including doctors, nurses, hospitals, and pharmaceuticals, just to name a few – would be cut dramatically. While the frustration for the continued COVID surges is understandable, I urge people to remember that in the business of health care we deal with preventable diseases all the time, every day. We are taught to show compassion for everyone, and for good reason. We have no idea what many people’s backstories are, we just know that they are sick and need help.

I urge everyone to put the unvaccinated under the same umbrella you put other people with preventable diseases, which, sadly, is a lot of patients. Continue to educate those about the vaccine as you should about every other aspect of their health. Education is part of our job as health care professionals but judgment is not.

Dr. Matuszak works for Sound Physicians and is a nocturnist at a hospital in the San Francisco Bay Area.

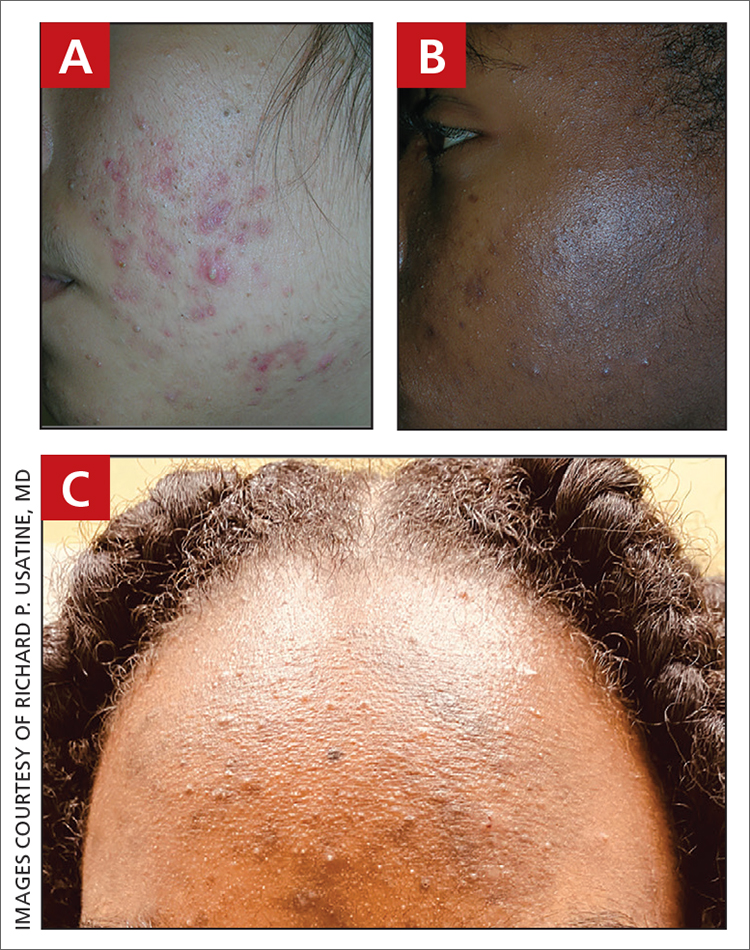

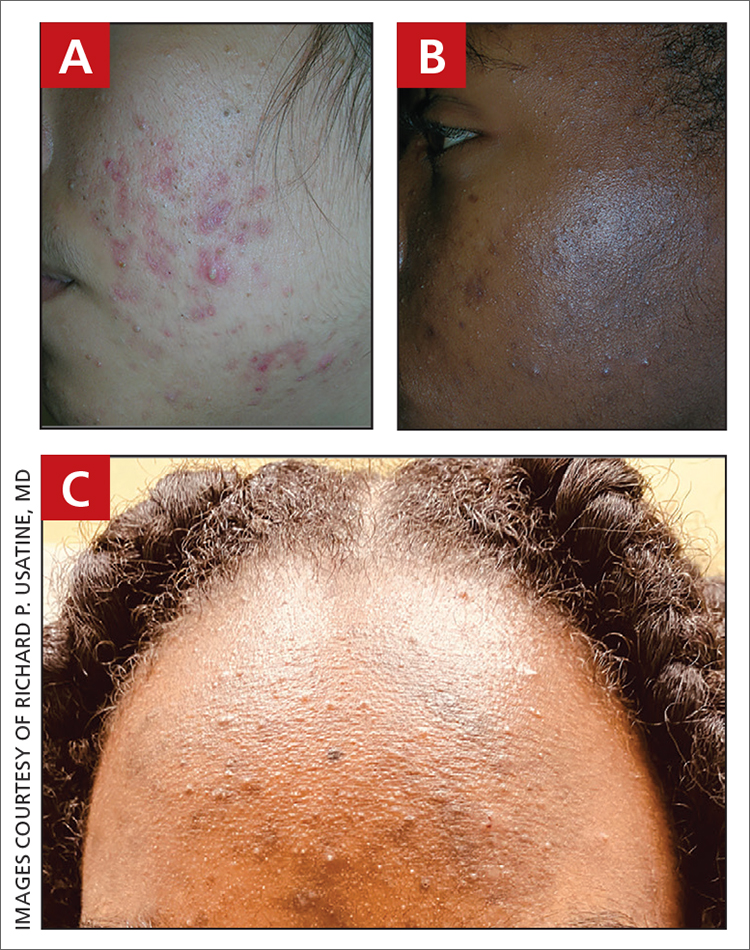

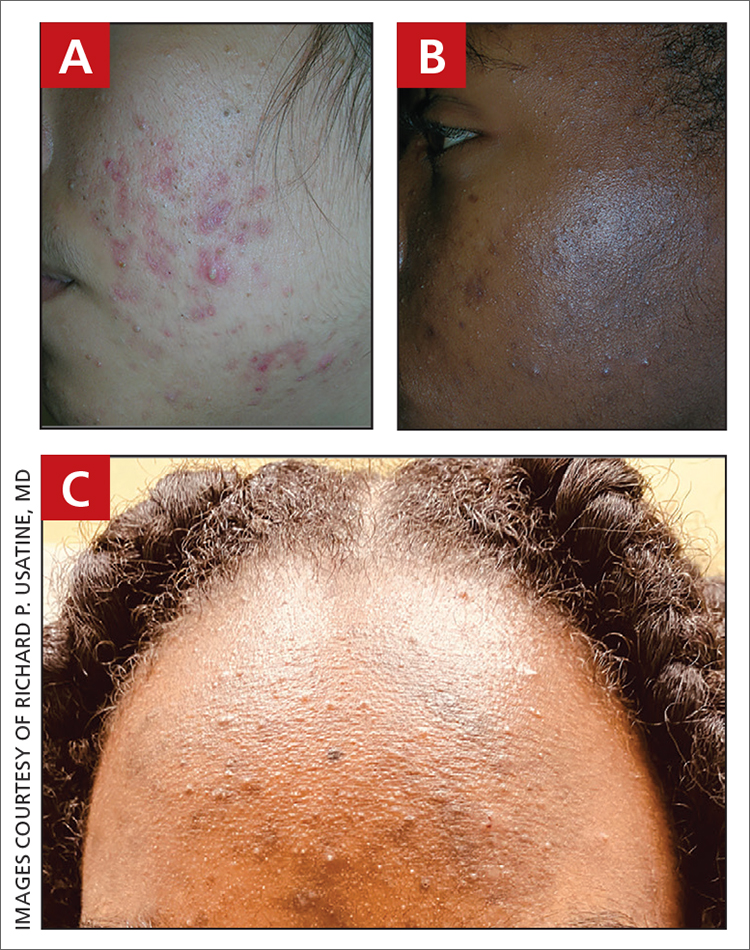

Ketosis, including ketogenic diets, implicated in prurigo pigmentosa

, according to a dermatologist, who reviewed skin conditions common to patients of Asian descent at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ketogenic diets are gaining popularity globally for weight loss. After 2-4 weeks [on a strict ketogenic diet], some patients start to notice very pruritic papules on their trunk, the so-called keto rash,” reported Hye Jin Chung, MD, director of the Asian Skin Clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. “Keto rash is actually prurigo pigmentosa.”

The exact pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa, a highly pruritic macular and papular rash with gross reticular pigmentation, is unclear, but Dr. Chung reported that the strong link with ketosis might explain why more cases are now being encountered outside of east Asia. Ketosis or conditions associated with a high risk for ketosis, such as anorexia nervosa, diabetes mellitus, or recent bariatric surgery, have been linked to prurigo pigmentosa in all skin types and ethnicities.

“I tell my residents that this is a disease you will never forget after your first case,” she said.

The differential diagnosis includes contact dermatitis and other inflammatory disorders, but Dr. Chung said that the reticular pattern of the lesions is a relatively unique feature. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) shares a pattern of reticulated lesions, but Dr. Chung said it lacks the inflammatory erythematous papules and the severe pruritus common to prurigo pigmentosa.

Histologically, the pattern evolves. It begins as a perivascular infiltration dominated by neutrophils and eosinophils with hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis. Over time, Dr. Chung said that the histologic picture shows an increasing degree of dyskeratosis as keratinocytes die.

Prurigo pigmentosa was first described 50 years ago by Masaji Nagashima, MD, who published a report on eight patients in Japan with a pruriginous truncal dermatosis featuring symmetrical pigmentation. Most subsequent reports were also from Japan or other east Asian countries, but it has since spread.

This global spread was captured in a recently published review of 115 published studies and case reports from 24 countries. In this review, the proportion of studies from Europe (36.5%) approached that of those from east Asia (38.2%), even if 76% of the patients for whom race was reported were of Asian ethnicity.

Of the 369 patients evaluated in these studies and case reports, 72.1% were female. The mean age was 25.6 years. In the studies originating outside of Asia, prurigo pigmentosa was reported in a spectrum of skin types and ethnicities, including Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The lowest reported incidence has been in the latter two groups, but the authors of the review speculated that this condition is likely being underdiagnosed in non-Asian individuals.

Dr. Chung agreed, and she cautioned that the consequences typically result in a significant delay for achieving disease control. In recounting a recent case of prurigo pigmentosa at her center, she said that the 59-year-old Asian patient had been initiated on topical steroids and oral antihistamines by her primary care physician before she was referred. This is a common and reasonable strategy for a highly pruritic rash potentially caused by contact dermatitis, but it is ineffective for this disorder.

“Prurigo pigmentosa requires anti-inflammatory agents,” she explained. She said that doxycycline and minocycline are the treatments of choice, but noted that there are also reports of efficacy with dapsone, macrolide antibiotics, and isotretinoin.

In her most recent case, she initiated the patient on 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily. There was significant improvement within 2 weeks, and the rash resolved within a month with no relapse in follow-up that now exceeds 12 months, Dr. Chung said.

According to Dr. Chung, Asian-Americans are the most rapidly growing ethnic group in the United States, making it increasingly important to be familiar with conditions common or unique to Asian skin, but prurigo pigmentosa is no longer confined to those of Asian descent. She encouraged clinicians to recognize this disorder to reduce the common delays to effective treatment.

The senior author of the recently published review of studies, Jensen Yeung, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Toronto, agreed. He, too, believes that dermatologists need to increase their awareness of the signs and symptoms of prurigo pigmentosa – and not just in Asian patients or patients of Asian descent.

“This diagnosis is often missed,” he contended in an interview. “This condition has become more common in the past 5 years in my clinical experience.” He added that the increasing incidence might not just be related to better diagnostic accuracy, although the most significant of other possible explanations “is not yet well understood.”

Dr. Chung reports that she has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Yeung reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical companies, some of which produce treatments employed in the control of prurigo pigmentosa.

, according to a dermatologist, who reviewed skin conditions common to patients of Asian descent at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ketogenic diets are gaining popularity globally for weight loss. After 2-4 weeks [on a strict ketogenic diet], some patients start to notice very pruritic papules on their trunk, the so-called keto rash,” reported Hye Jin Chung, MD, director of the Asian Skin Clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. “Keto rash is actually prurigo pigmentosa.”

The exact pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa, a highly pruritic macular and papular rash with gross reticular pigmentation, is unclear, but Dr. Chung reported that the strong link with ketosis might explain why more cases are now being encountered outside of east Asia. Ketosis or conditions associated with a high risk for ketosis, such as anorexia nervosa, diabetes mellitus, or recent bariatric surgery, have been linked to prurigo pigmentosa in all skin types and ethnicities.

“I tell my residents that this is a disease you will never forget after your first case,” she said.

The differential diagnosis includes contact dermatitis and other inflammatory disorders, but Dr. Chung said that the reticular pattern of the lesions is a relatively unique feature. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) shares a pattern of reticulated lesions, but Dr. Chung said it lacks the inflammatory erythematous papules and the severe pruritus common to prurigo pigmentosa.

Histologically, the pattern evolves. It begins as a perivascular infiltration dominated by neutrophils and eosinophils with hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis. Over time, Dr. Chung said that the histologic picture shows an increasing degree of dyskeratosis as keratinocytes die.

Prurigo pigmentosa was first described 50 years ago by Masaji Nagashima, MD, who published a report on eight patients in Japan with a pruriginous truncal dermatosis featuring symmetrical pigmentation. Most subsequent reports were also from Japan or other east Asian countries, but it has since spread.

This global spread was captured in a recently published review of 115 published studies and case reports from 24 countries. In this review, the proportion of studies from Europe (36.5%) approached that of those from east Asia (38.2%), even if 76% of the patients for whom race was reported were of Asian ethnicity.

Of the 369 patients evaluated in these studies and case reports, 72.1% were female. The mean age was 25.6 years. In the studies originating outside of Asia, prurigo pigmentosa was reported in a spectrum of skin types and ethnicities, including Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The lowest reported incidence has been in the latter two groups, but the authors of the review speculated that this condition is likely being underdiagnosed in non-Asian individuals.

Dr. Chung agreed, and she cautioned that the consequences typically result in a significant delay for achieving disease control. In recounting a recent case of prurigo pigmentosa at her center, she said that the 59-year-old Asian patient had been initiated on topical steroids and oral antihistamines by her primary care physician before she was referred. This is a common and reasonable strategy for a highly pruritic rash potentially caused by contact dermatitis, but it is ineffective for this disorder.

“Prurigo pigmentosa requires anti-inflammatory agents,” she explained. She said that doxycycline and minocycline are the treatments of choice, but noted that there are also reports of efficacy with dapsone, macrolide antibiotics, and isotretinoin.

In her most recent case, she initiated the patient on 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily. There was significant improvement within 2 weeks, and the rash resolved within a month with no relapse in follow-up that now exceeds 12 months, Dr. Chung said.

According to Dr. Chung, Asian-Americans are the most rapidly growing ethnic group in the United States, making it increasingly important to be familiar with conditions common or unique to Asian skin, but prurigo pigmentosa is no longer confined to those of Asian descent. She encouraged clinicians to recognize this disorder to reduce the common delays to effective treatment.

The senior author of the recently published review of studies, Jensen Yeung, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Toronto, agreed. He, too, believes that dermatologists need to increase their awareness of the signs and symptoms of prurigo pigmentosa – and not just in Asian patients or patients of Asian descent.

“This diagnosis is often missed,” he contended in an interview. “This condition has become more common in the past 5 years in my clinical experience.” He added that the increasing incidence might not just be related to better diagnostic accuracy, although the most significant of other possible explanations “is not yet well understood.”

Dr. Chung reports that she has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Yeung reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical companies, some of which produce treatments employed in the control of prurigo pigmentosa.

, according to a dermatologist, who reviewed skin conditions common to patients of Asian descent at the Skin of Color Update 2021.

“Ketogenic diets are gaining popularity globally for weight loss. After 2-4 weeks [on a strict ketogenic diet], some patients start to notice very pruritic papules on their trunk, the so-called keto rash,” reported Hye Jin Chung, MD, director of the Asian Skin Clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. “Keto rash is actually prurigo pigmentosa.”

The exact pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa, a highly pruritic macular and papular rash with gross reticular pigmentation, is unclear, but Dr. Chung reported that the strong link with ketosis might explain why more cases are now being encountered outside of east Asia. Ketosis or conditions associated with a high risk for ketosis, such as anorexia nervosa, diabetes mellitus, or recent bariatric surgery, have been linked to prurigo pigmentosa in all skin types and ethnicities.

“I tell my residents that this is a disease you will never forget after your first case,” she said.

The differential diagnosis includes contact dermatitis and other inflammatory disorders, but Dr. Chung said that the reticular pattern of the lesions is a relatively unique feature. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP) shares a pattern of reticulated lesions, but Dr. Chung said it lacks the inflammatory erythematous papules and the severe pruritus common to prurigo pigmentosa.

Histologically, the pattern evolves. It begins as a perivascular infiltration dominated by neutrophils and eosinophils with hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiosis. Over time, Dr. Chung said that the histologic picture shows an increasing degree of dyskeratosis as keratinocytes die.

Prurigo pigmentosa was first described 50 years ago by Masaji Nagashima, MD, who published a report on eight patients in Japan with a pruriginous truncal dermatosis featuring symmetrical pigmentation. Most subsequent reports were also from Japan or other east Asian countries, but it has since spread.

This global spread was captured in a recently published review of 115 published studies and case reports from 24 countries. In this review, the proportion of studies from Europe (36.5%) approached that of those from east Asia (38.2%), even if 76% of the patients for whom race was reported were of Asian ethnicity.

Of the 369 patients evaluated in these studies and case reports, 72.1% were female. The mean age was 25.6 years. In the studies originating outside of Asia, prurigo pigmentosa was reported in a spectrum of skin types and ethnicities, including Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. The lowest reported incidence has been in the latter two groups, but the authors of the review speculated that this condition is likely being underdiagnosed in non-Asian individuals.

Dr. Chung agreed, and she cautioned that the consequences typically result in a significant delay for achieving disease control. In recounting a recent case of prurigo pigmentosa at her center, she said that the 59-year-old Asian patient had been initiated on topical steroids and oral antihistamines by her primary care physician before she was referred. This is a common and reasonable strategy for a highly pruritic rash potentially caused by contact dermatitis, but it is ineffective for this disorder.

“Prurigo pigmentosa requires anti-inflammatory agents,” she explained. She said that doxycycline and minocycline are the treatments of choice, but noted that there are also reports of efficacy with dapsone, macrolide antibiotics, and isotretinoin.

In her most recent case, she initiated the patient on 100 mg of doxycycline twice daily. There was significant improvement within 2 weeks, and the rash resolved within a month with no relapse in follow-up that now exceeds 12 months, Dr. Chung said.

According to Dr. Chung, Asian-Americans are the most rapidly growing ethnic group in the United States, making it increasingly important to be familiar with conditions common or unique to Asian skin, but prurigo pigmentosa is no longer confined to those of Asian descent. She encouraged clinicians to recognize this disorder to reduce the common delays to effective treatment.

The senior author of the recently published review of studies, Jensen Yeung, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Toronto, agreed. He, too, believes that dermatologists need to increase their awareness of the signs and symptoms of prurigo pigmentosa – and not just in Asian patients or patients of Asian descent.

“This diagnosis is often missed,” he contended in an interview. “This condition has become more common in the past 5 years in my clinical experience.” He added that the increasing incidence might not just be related to better diagnostic accuracy, although the most significant of other possible explanations “is not yet well understood.”

Dr. Chung reports that she has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Yeung reports financial relationships with more than 25 pharmaceutical companies, some of which produce treatments employed in the control of prurigo pigmentosa.

FROM SOC 2021

U.S. study finds racial, gender differences in surgical treatment of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

.

Current guidelines recommend Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) as a first-line treatment for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, but the procedure may be inaccessible for certain populations and in some geographic areas, wrote Kevin J. Moore, MD, and Michael S. Chang, BA, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Wide local excision (WLE) is a less effective option; recurrence rates associated with this treatment are approximately 30% because of incomplete margin assessment, compared with about 3% with MMS, they noted.

In the study, published as a letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators identified 2,370 cases of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans using data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registry from 2000 to 2018. The mean age of the patients was 44 years; 55% were women. A total of 539 patients underwent MMS and 1,831 underwent WLE.

Overall, patients in the WLE group were more likely to be younger, male, Black, and single, the researchers noted. Those who had WLE, they added, were “more commonly deceased at study end date, recipients of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, and had truncal tumor locations.”

In a multivariate analysis, patients who were non-Hispanic, White, or other races (including American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander), were significantly more likely to undergo MMS compared with Black and Hispanic patients (adjusted odd ratio [aOR], 1.46, 1.66, and 2.42, respectively). Women were also significantly more likely than were men to undergo MMS (aOR, 1.24). Individuals living in the Western part of the United States were significantly more likely to undergo MMS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to control for insurance status, lack of data on re-excision, and the use of aggregate case data, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the disparities in use of MMS for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, they said.

“Because MMS is associated with significantly improved outcomes, identifying at-risk patient populations and barriers to accessing MMS is essential,” the researchers noted. The results suggest that disparities persist in accessing MMS for many patients, notably Black and Hispanic males, they said. “Further work is necessary to identify mechanisms for increasing access to MMS,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

Current guidelines recommend Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) as a first-line treatment for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, but the procedure may be inaccessible for certain populations and in some geographic areas, wrote Kevin J. Moore, MD, and Michael S. Chang, BA, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Wide local excision (WLE) is a less effective option; recurrence rates associated with this treatment are approximately 30% because of incomplete margin assessment, compared with about 3% with MMS, they noted.

In the study, published as a letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators identified 2,370 cases of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans using data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registry from 2000 to 2018. The mean age of the patients was 44 years; 55% were women. A total of 539 patients underwent MMS and 1,831 underwent WLE.

Overall, patients in the WLE group were more likely to be younger, male, Black, and single, the researchers noted. Those who had WLE, they added, were “more commonly deceased at study end date, recipients of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, and had truncal tumor locations.”

In a multivariate analysis, patients who were non-Hispanic, White, or other races (including American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander), were significantly more likely to undergo MMS compared with Black and Hispanic patients (adjusted odd ratio [aOR], 1.46, 1.66, and 2.42, respectively). Women were also significantly more likely than were men to undergo MMS (aOR, 1.24). Individuals living in the Western part of the United States were significantly more likely to undergo MMS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to control for insurance status, lack of data on re-excision, and the use of aggregate case data, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the disparities in use of MMS for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, they said.

“Because MMS is associated with significantly improved outcomes, identifying at-risk patient populations and barriers to accessing MMS is essential,” the researchers noted. The results suggest that disparities persist in accessing MMS for many patients, notably Black and Hispanic males, they said. “Further work is necessary to identify mechanisms for increasing access to MMS,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

Current guidelines recommend Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) as a first-line treatment for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, but the procedure may be inaccessible for certain populations and in some geographic areas, wrote Kevin J. Moore, MD, and Michael S. Chang, BA, of the department of dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Wide local excision (WLE) is a less effective option; recurrence rates associated with this treatment are approximately 30% because of incomplete margin assessment, compared with about 3% with MMS, they noted.

In the study, published as a letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the investigators identified 2,370 cases of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans using data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Registry from 2000 to 2018. The mean age of the patients was 44 years; 55% were women. A total of 539 patients underwent MMS and 1,831 underwent WLE.

Overall, patients in the WLE group were more likely to be younger, male, Black, and single, the researchers noted. Those who had WLE, they added, were “more commonly deceased at study end date, recipients of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, and had truncal tumor locations.”

In a multivariate analysis, patients who were non-Hispanic, White, or other races (including American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander), were significantly more likely to undergo MMS compared with Black and Hispanic patients (adjusted odd ratio [aOR], 1.46, 1.66, and 2.42, respectively). Women were also significantly more likely than were men to undergo MMS (aOR, 1.24). Individuals living in the Western part of the United States were significantly more likely to undergo MMS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to control for insurance status, lack of data on re-excision, and the use of aggregate case data, the researchers noted. However, the results highlight the disparities in use of MMS for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, they said.

“Because MMS is associated with significantly improved outcomes, identifying at-risk patient populations and barriers to accessing MMS is essential,” the researchers noted. The results suggest that disparities persist in accessing MMS for many patients, notably Black and Hispanic males, they said. “Further work is necessary to identify mechanisms for increasing access to MMS,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAAD

Dr. Judy C. Washington shows URM physicians how to lead

For URM physicians, she also imparts a shared experience of being a minority in the field and helps prepare them for the challenges of facing racism or feeling marginalized or not equitably supported in academic life – and for making change.

While family medicine’s demographics have become more diverse over time, and more so than other specialties, they are not yet representative of the U.S. population. Within academia, male physicians who are Black or African American, or Hispanic or Latino, comprised about 4% and 5% of family medicine faculty, respectively, at the end of 2019, according to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges. For women, these numbers were about 9% and 4%, respectively. (Only those with an MD degree exclusively were included in the report.)

“When you have the privilege to serve in leadership, you have the responsibility to reach back and identify and help others who would not otherwise have the opportunity to be recognized,” Dr. Washington said.

Her mentorship work stems in large part from her long-time involvement and leadership roles in the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) – roles she considers a pillar of her professional life. She currently serves as president of the STFM Foundation and is associate chief medical officer of the Atlantic Medical Group, a large multisite physician-led organization. She is also coordinator of women’s health for the Overlook Family Medicine Residency Program, which is affiliated with Atlantic Medical Group.

In Dr. Washington’s role as associate chief medical officer of Atlantic Medical Group in Summit, N.J., she focuses on physician engagement, satisfaction, and diversity. She also assists in areas such as population health. For the Overlook Family Medicine Residency Program also in Summit, she precepts residents in the obstetrics clinic and in the family medicine outpatient clinic.

Diana N. Carvajal, MD, MPH, one of Dr. Washington’s mentees, called her an “inspirational leader” for young academic faculty and said she is a familiar speaker at STFM meetings on topics of workforce diversity, equity, and leadership. She is “passionate” about mentorship, Dr. Carvajal said, and has understood “that URMs and women of color were not always getting [the mentorship they need to be successful].”

Guiding future leaders

Ivonne McLean, MD, assistant professor of family and community medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and an attending at a community health center in the Bronx, called Dr. Washington for advice a couple of years ago when she was considering her next career move.

“She took a genuine interest in me. She never said, this is what you should do. But the questions she asked and the examples she gave from her own life were incredibly helpful to me [in deciding to pursue a research fellowship] ... it was a pivotal conversation,” said Dr. McLean, associate director of a reproductive health fellowship and a research fellow in a New York State–funded program.

“From a lived experience angle, she also told me, here are some of the challenges you’ll have as a woman of color, and here are some of the ways you can approach that,” she said.

Dr. Carvajal, also a URM family physician, credits Dr. Washington’s mentorship with the development of a day-long workshop – held before the annual Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) meeting – on the low and declining rates of Black males in medicine. “We’d planned it as a presentation, and [she heard of it and] helped us expand it,” she said, calling Dr. Washington “warm, welcoming, and encouraging.

“That work and collaboration with her and the others she brought [into the process] have resulted in publications and more presentations and strategy building for diversifying the workforce,” said Dr. Carvajal, assistant professor, director of reproductive health education in family medicine, and codirector of the research section, all in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

STFM involvement

Dr. Washington, who says that all or almost all of her mentees are now leaders in their academic institutions and communities, has been instrumental in developing STFM’s mentoring programming and in facilitating the organization’s multifaceted URM Initiative.

She has been active in STFM since the start of her academic career, and in 2009, while serving as assistant program director for the residency program in which she’d trained, she joined two other African American women, Monique Y. Davis-Smith, MD, and Joedrecka Brown-Speights, MD, in cochairing the society’s Group on Minority and Multicultural Health.

It was in this space, that Dr. Washington said she “heard people’s stories of being in major academic institutions and not feeling supported, not being given roadmaps to success, not getting assistance with publishing, or just kind of feeling like an outsider ... of not being pulled in.” Hispanic and African American females, in particular, “were feeling marginalized,” she said.