User login

Embedding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice in hospital medicine

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

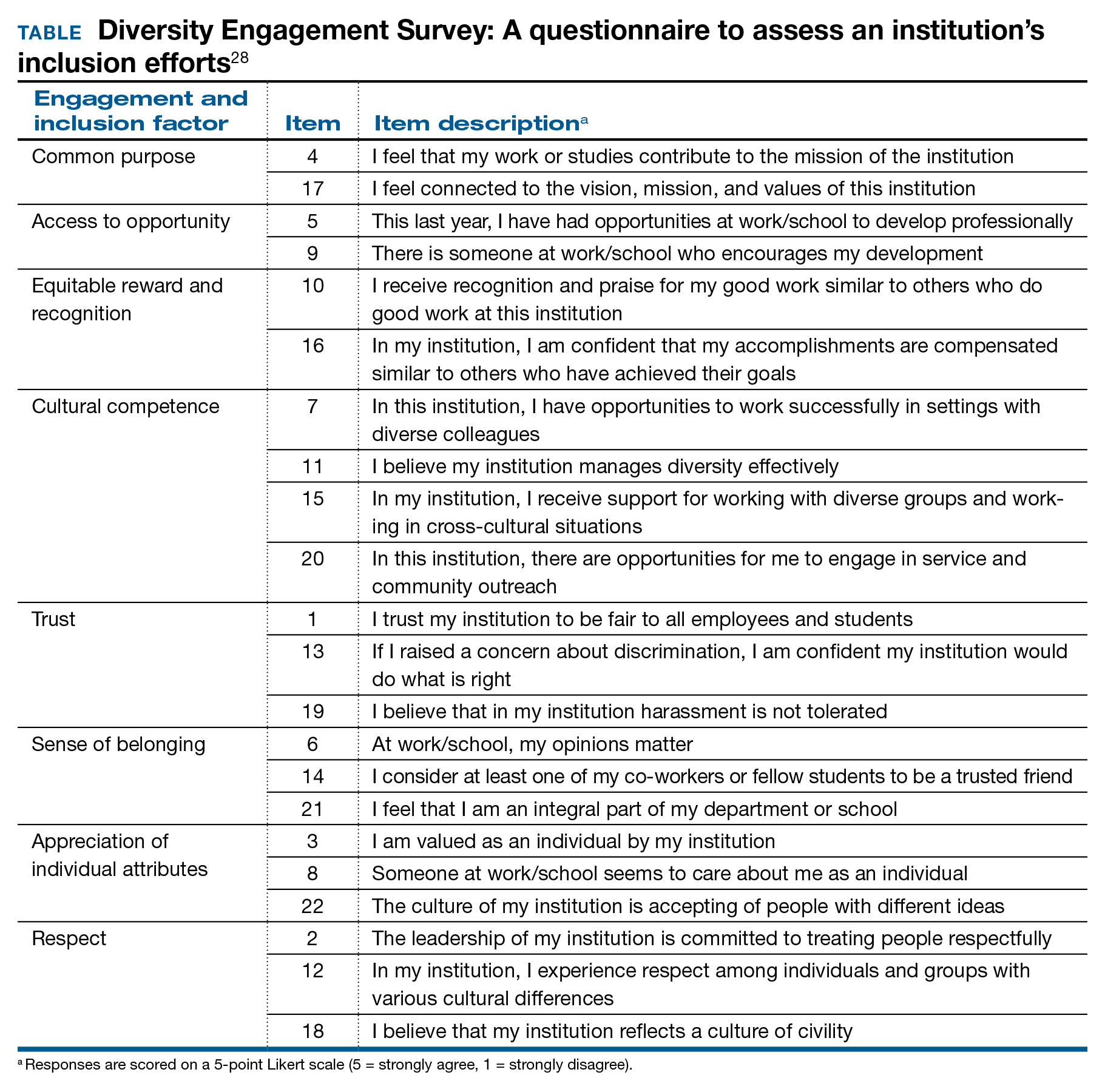

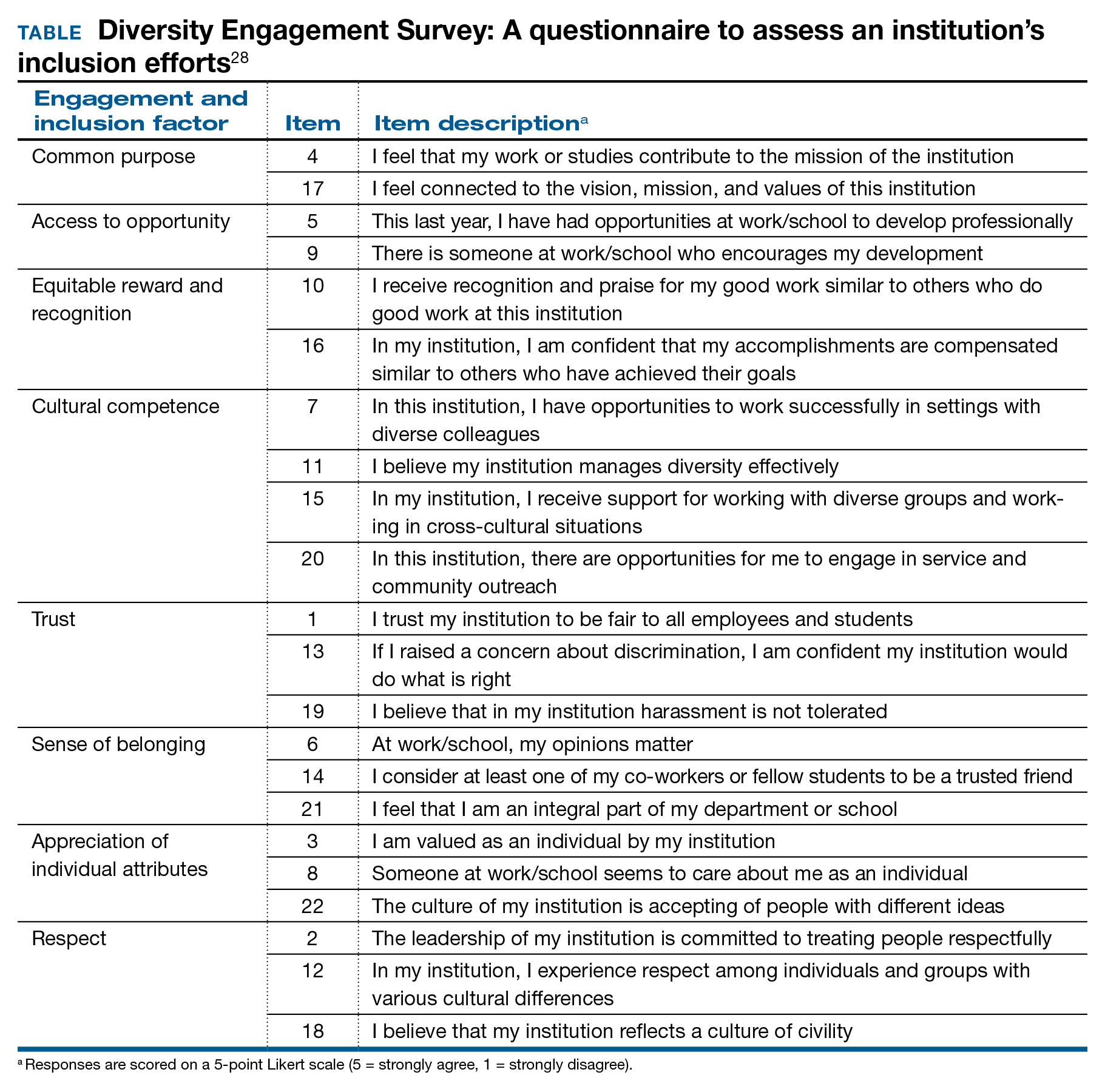

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

A road map for success

A road map for success

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

The language of equality in America’s founding was never truly embraced, resulting in a painful legacy of slavery, racial injustice, and gender inequality inherited by all generations. However, for as long as America has fallen short of this unfulfilled promise, individuals have dedicated their lives to the tireless work of correcting injustice. Although the process has been painstakingly slow, our nation has incrementally inched toward the promised vision of equality, and these efforts continue today. With increased attention to social justice movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, our collective social consciousness may be finally waking up to the systemic injustices embedded into our fundamental institutions.

Medicine is not immune to these injustices. Persistent underrepresentation of women and minorities remains in medical school faculty and the broader physician workforce, and the same inequities exist in hospital medicine.1-6 The report by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) on diversity in medicine highlights the impact widespread implicit and explicit bias has on creating exclusionary environments, exemplified by research demonstrating lower promotion rates in non-White faculty.7-8 The report calls us, as physicians, to a broader mission: “Focusing solely on increasing compositional diversity along the academic continuum is insufficient. To effectively enact institutional change at academic medical centers ... leaders must focus their efforts on developing inclusive, equity-minded environments.”7

We have a clear moral imperative to correct these shortcomings for our profession and our patients. It is incumbent on our institutions and hospital medicine groups (HMGs) to embark on the necessary process of systemic institutional change to address inequality and justice within our field.

A road map for DEI and justice in hospital medicine

The policies and biases allowing these inequities to persist have existed for decades, and superficial efforts will not bring sufficient change. Our institutions require new building blocks from which the foundation of a wholly inclusive and equal system of practice can be constructed. Encouragingly, some institutions and HMGs have taken steps to modernize their practices. We offer examples and suggestions of concrete practices to begin this journey, organizing these efforts into three broad categories:

1. Recruitment and retention

2. Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

3. Community engagement and partnership.

Recruitment and retention

Improving equity and inclusion begins with recruitment. Search and hiring committees should be assembled intentionally, with gender balance, and ideally with diversity or equity experts invited to join. All members should receive unconscious bias training. For example, the University of Colorado utilizes a toolkit to ensure appropriate steps are followed in the recruitment process, including predetermined candidate selection criteria that are ranked in advance.

Job descriptions should be reviewed by a diversity expert, ensuring unbiased and ungendered language within written text. Advertisements should be wide-reaching, and the committee should consider asking applicants for a diversity statement. Interviews should include a variety of interviewers and interview types (e.g., 1:1, group, etc.). Letters of recommendation deserve special scrutiny; letters for women and minorities may be at risk of being shorter and less record focused, and may be subject to less professional respect, such as use of first names over honorifics or titles.

Once candidates are hired, institutions and HMGs should prioritize developing strategies to improve retention of a diverse workforce. This includes special attention to workplace culture, and thoughtfully striving for cultural intelligence within the group. Some examples may include developing affinity groups, such as underrepresented in medicine (UIM), women in medicine (WIM), or LGBTQ+ groups. Affinity groups provide a safe space for members and allies to support and uplift each other. Institutional and HMG leaders must educate themselves and their members on the importance of language (see table), and the more insidious forms of bias and discrimination that adversely affect workplace culture. Microinsults and microinvalidations, for example, can hurt and result in failure to recruit or turnover.

Conducting exit interviews when any hospitalist leaves is important to learn how to improve, but holding ‘stay’ interviews is mission critical. Stay interviews are an opportunity for HMG leaders to proactively understand why hospitalists stay, and what can be done to create more inclusive and equitable environments to retain them. This process creates psychological safety that brings challenges to the fore to be addressed, and spotlights best practices to be maintained and scaled.

Scholarship, mentorship, and sponsorship

Women and minorities are known to be over-mentored and under-sponsored. Sponsorship is defined by Ayyala et al. as “active support by someone appropriately placed in the organization who has significant influence on decision making processes or structures and who is advocating for the career advancement of an individual and recommends them for leadership roles, awards, or high-profile speaking opportunities.”9 While the goal of mentorship is professional development, sponsorship emphasizes professional advancement. Deliberate steps to both mentor and then sponsor diverse hospitalists and future hospitalists (including trainees) are important to ensure equity.

More inclusive HMGs can be bolstered by prioritizing peer education on the professional imperative that we have a diverse workforce and equitable, just workplaces. Academic institutions may use existing structures such as grand rounds to provide education on these crucial topics, and all HMGs can host journal clubs and professional development sessions on leadership competencies that foster inclusion and equity. Sessions coordinated by women and minorities are also a form of justice, by helping overcome barriers to career advancement. Diverse faculty presenting in educational venues will result in content that is relevant to more audience members and will exemplify that leaders and experts are of all races, ethnicities, genders, ages, and abilities.

Groups should prioritize mentoring trainees and early-career hospitalists on scholarly projects that examine equity in opportunities of care, which signals that this science is valued as much as basic research. When used to demonstrate areas needing improvement, these projects can drive meaningful change. Even projects as straightforward as studying diversity in conference presenters, disparities in adherence to guidelines, or QI projects on how race is portrayed in the medical record can be powerful tools in advancing equity.

A key part of mentoring is training hospitalists and future hospitalists in how to be an upstander, as in how to intervene when a peer or patient is affected by bias, harassment, or discrimination. Receiving such training can prepare hospitalists for these nearly inevitable experiences and receiving training during usual work hours communicates that this is a valuable and necessary professional competency.

Community engagement and partnership

Institutions and HMGs should deliberately work to promote community engagement and partnership within their groups. Beyond promoting health equity, community engagement also fosters inclusivity by allowing community members to share their ideas and give recommendations to the institutions that serve them.

There is a growing body of literature that demonstrates how disadvantages by individual and neighborhood-level socioeconomic status (SES) contribute to disparities in specific disease conditions.10-11 Strategies to narrow the gap in SES disadvantages may help reduce race-related health disparities. Institutions that engage the community and develop programs to promote health equity can do so through bidirectional exchange of knowledge and mutual benefit.

An institution-specific example is Medicine for the Greater Good at Johns Hopkins. The founders of this program wrote, “health is not synonymous with medicine. To truly care for our patients and their communities, health care professionals must understand how to deliver equitable health care that meets the needs of the diverse populations we care for. The mission of Medicine for the Greater Good is to promote health and wellness beyond the confines of the hospital through an interactive and engaging partnership with the community ...” Community engagement also provides an opportunity for growing the cultural intelligence of institutions and HMGs.

Tools for advancing comprehensive change – Repurposing PDSA cycles

Whether institutions and HMGs are at the beginning of their journey or further along in the work of reducing disparities, having a systematic approach for implementing and refining policies and procedures can cultivate more inclusive and equitable environments. Thankfully, hospitalists are already equipped with the fundamental tools needed to advance change across their institutions – QI processes in the form of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.

They allow a continuous cycle of successful incremental change based on direct evidence and experience. Any efforts to deconstruct systematic bias within our organizations must also be a continual process. Our female colleagues and colleagues of color need our institutions to engage unceasingly to bring about the equality they deserve. To that end, PDSA cycles are an apt tool to utilize in this work as they can naturally function in a never-ending process of improvement.

With PDSA as a model, we envision a cycle with steps that are intentionally purposed to fit the needs of equitable institutional change: Target-Engage-Assess-Modify. As highlighted (see graphic), these modifications ensure that stakeholders (i.e., those that unequal practices and policies affect the most) are engaged early and remain involved throughout the cycle.

As hospitalists, we have significant work ahead to ensure that we develop and maintain a diverse, equitable and inclusive workforce. This work to bring change will not be easy and will require a considerable investment of time and resources. However, with the strategies and tools that we have outlined, our institutions and HMGs can start the change needed in our profession for our patients and the workforce. In doing so, we can all be accomplices in the fight to achieve racial and gender equity, and social justice.

Dr. Delapenha and Dr. Kisuule are based in the department of internal medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. Dr. Martin is based in the department of medicine, section of hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. Dr. Barrett is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

References

1. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019: Figure 19. Percentage of physicians by sex, 2018. AAMC website.

2. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 16. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by sex and race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

3. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 15. Percentage of full-time U.S. medical school faculty by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

4. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 6. Percentage of acceptees to U.S. medical schools by race/ethnicity (alone), academic year 2018-2019. AAMC website.

5. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019 Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. AAMC website.

6. Herzke C et al. Gender issues in academic hospital medicine: A national survey of hospitalist leaders. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1641-6.

7. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Fostering diversity and inclusion. AAMC website.

8. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Executive summary. AAMC website.

9. Ayyala MS et al. Mentorship is not enough: Exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

10. Ejike OC et al. Contribution of individual and neighborhood factors to racial disparities in respiratory outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 Apr 15;203(8):987-97.

11. Galiatsatos P et al. The effect of community socioeconomic status on sepsis-attributable mortality. J Crit Care. 2018 Aug;46:129-33.

Acne Vulgaris

THE COMPARISON

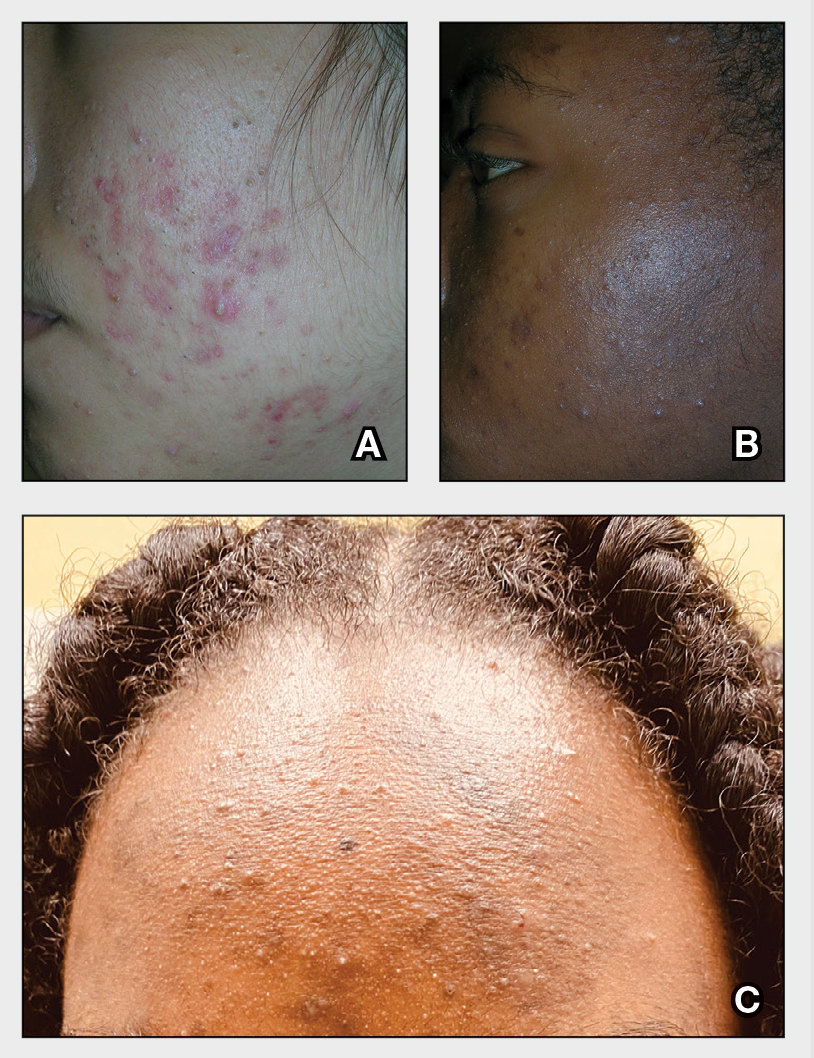

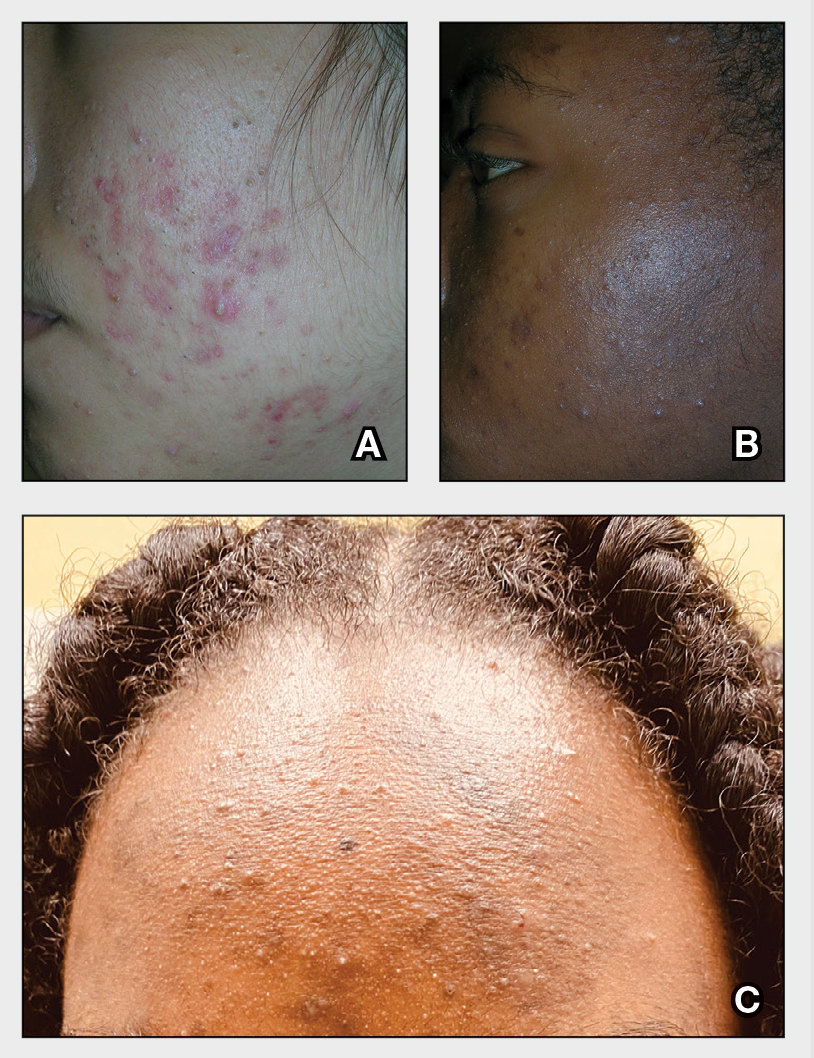

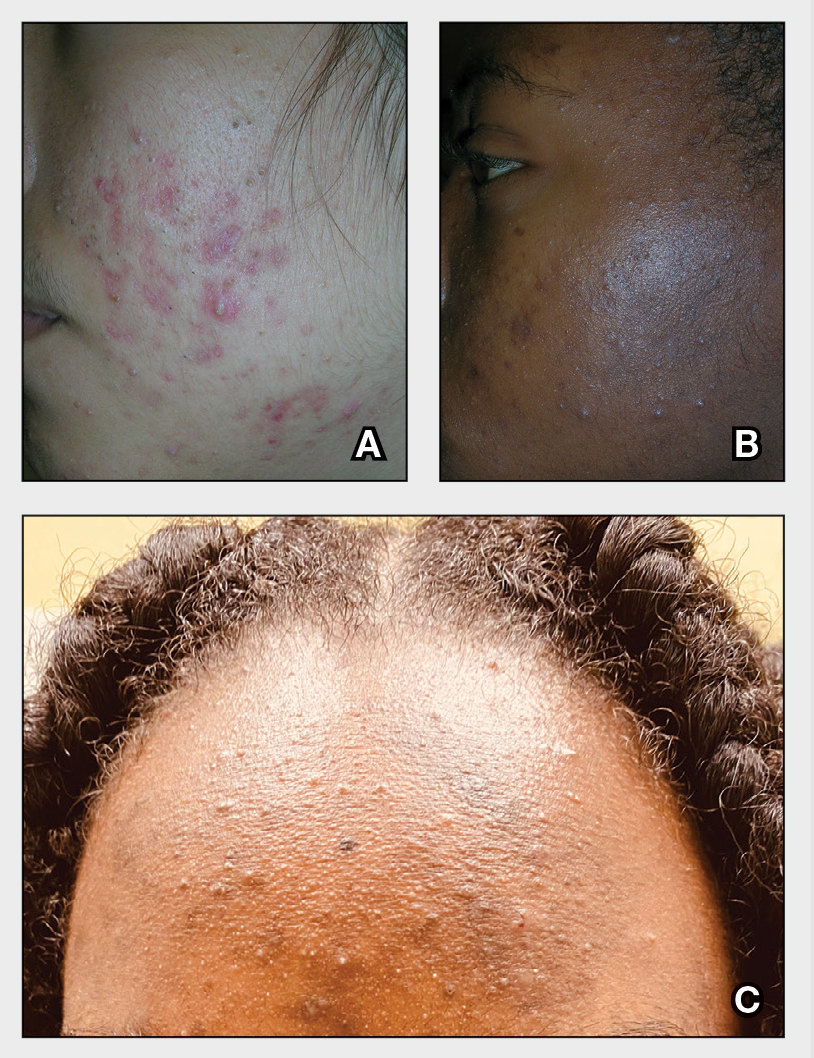

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

Eurocentric standards of beauty are no longer dominant, experts agree

Addressing current standards of beauty at the Skin of Color Update 2021, dermatologists speaking about attitudes within four ethnic groups recounted a similar story: .

This change is relevant to dermatologists consulting with patients for cosmetic procedures. Four dermatologists who recounted the types of procedures their patients are requesting each reported that more patients are seeking cosmetic enhancements that accentuate rather than modify ethnic features.

Lips in Black, Asian, and Arab ethnic groups are just one example.

“Where several years ago, the conversation was really about lip reductions – how we can deemphasize the lip – I am now seeing lots of women of color coming in to ask about lip augmentation, looking to highlight their lips as a point of beauty,” reported Michelle Henry, MD, a dermatologist who practices in New York City.

She is not alone. Others participating on the same panel spoke of a growing interest among their patients to maintain or even emphasize the same ethnic features – including but not limited to lip shape and size that they were once anxious to modify.

In Asian patients, “the goal is not to Westernize,” agreed Annie Chiu, MD, a dermatologist who practices in North Redondo Beach, Calif. For lips, she spoke of the “50-50 ratio” of upper and lower lip symmetry that is consistent with a traditional Asian characteristic.

Like Dr. Henry, Dr. Chiu said that many requests for cosmetic work now involve accentuating Asian features, such as the oval shape of the face, rather than steps to modify this shape. This is a relatively recent change.

“I am finding that more of my patients want to improve the esthetic balance to optimize the appearance within their own ethnicity,” she said.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Hassan Galadari, MD, an American-trained physician who is assistant professor of dermatology at the UAE University in Dubai, recently conducted a poll of his patients. In order of importance, full lips came after wide eyes, a straight nose, and a sharp jaw line. Full cheeks and a round face completed a list that diverges from the California-blond prototype.

Although Angelina Jolie was selected over several Lebanese actresses as a first choice for an icon of beauty in this same poll, Dr. Galadari pointed out that this actress has many of the features, including wide eyes, a straight nose, and full lips, that are consistent with traditional features of Arab beauty.

Perceptions of beauty are not just changing within ethnic groups but reflected in mass culture. Dr. Henry pointed to a published comparison of the “World’s Most Beautiful” list from People magazine in 2017 relative to 1990. Of the 50 celebrities on the list in 1990, 88% were Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. Only 12% were types IV-VI, which increased to almost 30% of the 135 celebrities on the list in 2017 (P = .01). In 1990, just one celebrity (2%) was of mixed race, which increased to 10.4% in 2017.

Among Hispanic women, the changes in attitude are perhaps best captured among younger relative to older patients requesting cosmetic work, according to Maritza I. Perez, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Connecticut, Farmington. She said that her younger patients are less likely to seek rhinoplasty and blepharoplasty relative to her older patients, a reflection perhaps of comfort with their natural looks.

However, “the celebration of Latinas as beautiful, seductive, and sexual is hardly new,” she said, indicating that younger Hispanic patients are probably not driven to modify their ethnic features because they are already widely admired. “Six of the 10 women crowned Miss Universe in the last decade were from Latin American countries,” she noted.

The general willingness of patients within ethnic groups and society as a whole to see ethnic features as admirable and attractive was generally regarded by all the panelists as a positive development.

Dr. Henry, who said she was “encouraged” by such trends as “the natural hair movement” and diminishing interest among her darker patients in lightening skin pigment, said, “I definitely see a change among my patients in regard to their goals.”

For clinicians offering consults to patients seeking cosmetic work, Dr. Henry recommended being aware and sensitive to this evolution in order to offer appropriate care.

Dr. Chiu, emphasizing the pride that many of her patients take in their Asian features, made the same recommendation. She credited globalization and social media for attitudes that have allowed an embrace of what are now far more inclusive standards of beauty.

Dr. Henry reports financial relationships with Allergan and Merz. Dr. Chiu has financial relationships with AbbVie, Cynosure, Merz, Revance, and Solta. Dr. Galadari reports financial relationships with nine pharmaceutical companies, including Allergan, Merz, Revance, and Fillmed Laboratories. Dr. Perez reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Addressing current standards of beauty at the Skin of Color Update 2021, dermatologists speaking about attitudes within four ethnic groups recounted a similar story: .

This change is relevant to dermatologists consulting with patients for cosmetic procedures. Four dermatologists who recounted the types of procedures their patients are requesting each reported that more patients are seeking cosmetic enhancements that accentuate rather than modify ethnic features.

Lips in Black, Asian, and Arab ethnic groups are just one example.

“Where several years ago, the conversation was really about lip reductions – how we can deemphasize the lip – I am now seeing lots of women of color coming in to ask about lip augmentation, looking to highlight their lips as a point of beauty,” reported Michelle Henry, MD, a dermatologist who practices in New York City.

She is not alone. Others participating on the same panel spoke of a growing interest among their patients to maintain or even emphasize the same ethnic features – including but not limited to lip shape and size that they were once anxious to modify.

In Asian patients, “the goal is not to Westernize,” agreed Annie Chiu, MD, a dermatologist who practices in North Redondo Beach, Calif. For lips, she spoke of the “50-50 ratio” of upper and lower lip symmetry that is consistent with a traditional Asian characteristic.

Like Dr. Henry, Dr. Chiu said that many requests for cosmetic work now involve accentuating Asian features, such as the oval shape of the face, rather than steps to modify this shape. This is a relatively recent change.

“I am finding that more of my patients want to improve the esthetic balance to optimize the appearance within their own ethnicity,” she said.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Hassan Galadari, MD, an American-trained physician who is assistant professor of dermatology at the UAE University in Dubai, recently conducted a poll of his patients. In order of importance, full lips came after wide eyes, a straight nose, and a sharp jaw line. Full cheeks and a round face completed a list that diverges from the California-blond prototype.

Although Angelina Jolie was selected over several Lebanese actresses as a first choice for an icon of beauty in this same poll, Dr. Galadari pointed out that this actress has many of the features, including wide eyes, a straight nose, and full lips, that are consistent with traditional features of Arab beauty.

Perceptions of beauty are not just changing within ethnic groups but reflected in mass culture. Dr. Henry pointed to a published comparison of the “World’s Most Beautiful” list from People magazine in 2017 relative to 1990. Of the 50 celebrities on the list in 1990, 88% were Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. Only 12% were types IV-VI, which increased to almost 30% of the 135 celebrities on the list in 2017 (P = .01). In 1990, just one celebrity (2%) was of mixed race, which increased to 10.4% in 2017.

Among Hispanic women, the changes in attitude are perhaps best captured among younger relative to older patients requesting cosmetic work, according to Maritza I. Perez, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Connecticut, Farmington. She said that her younger patients are less likely to seek rhinoplasty and blepharoplasty relative to her older patients, a reflection perhaps of comfort with their natural looks.

However, “the celebration of Latinas as beautiful, seductive, and sexual is hardly new,” she said, indicating that younger Hispanic patients are probably not driven to modify their ethnic features because they are already widely admired. “Six of the 10 women crowned Miss Universe in the last decade were from Latin American countries,” she noted.

The general willingness of patients within ethnic groups and society as a whole to see ethnic features as admirable and attractive was generally regarded by all the panelists as a positive development.

Dr. Henry, who said she was “encouraged” by such trends as “the natural hair movement” and diminishing interest among her darker patients in lightening skin pigment, said, “I definitely see a change among my patients in regard to their goals.”

For clinicians offering consults to patients seeking cosmetic work, Dr. Henry recommended being aware and sensitive to this evolution in order to offer appropriate care.

Dr. Chiu, emphasizing the pride that many of her patients take in their Asian features, made the same recommendation. She credited globalization and social media for attitudes that have allowed an embrace of what are now far more inclusive standards of beauty.

Dr. Henry reports financial relationships with Allergan and Merz. Dr. Chiu has financial relationships with AbbVie, Cynosure, Merz, Revance, and Solta. Dr. Galadari reports financial relationships with nine pharmaceutical companies, including Allergan, Merz, Revance, and Fillmed Laboratories. Dr. Perez reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Addressing current standards of beauty at the Skin of Color Update 2021, dermatologists speaking about attitudes within four ethnic groups recounted a similar story: .

This change is relevant to dermatologists consulting with patients for cosmetic procedures. Four dermatologists who recounted the types of procedures their patients are requesting each reported that more patients are seeking cosmetic enhancements that accentuate rather than modify ethnic features.

Lips in Black, Asian, and Arab ethnic groups are just one example.

“Where several years ago, the conversation was really about lip reductions – how we can deemphasize the lip – I am now seeing lots of women of color coming in to ask about lip augmentation, looking to highlight their lips as a point of beauty,” reported Michelle Henry, MD, a dermatologist who practices in New York City.

She is not alone. Others participating on the same panel spoke of a growing interest among their patients to maintain or even emphasize the same ethnic features – including but not limited to lip shape and size that they were once anxious to modify.

In Asian patients, “the goal is not to Westernize,” agreed Annie Chiu, MD, a dermatologist who practices in North Redondo Beach, Calif. For lips, she spoke of the “50-50 ratio” of upper and lower lip symmetry that is consistent with a traditional Asian characteristic.

Like Dr. Henry, Dr. Chiu said that many requests for cosmetic work now involve accentuating Asian features, such as the oval shape of the face, rather than steps to modify this shape. This is a relatively recent change.

“I am finding that more of my patients want to improve the esthetic balance to optimize the appearance within their own ethnicity,” she said.

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Hassan Galadari, MD, an American-trained physician who is assistant professor of dermatology at the UAE University in Dubai, recently conducted a poll of his patients. In order of importance, full lips came after wide eyes, a straight nose, and a sharp jaw line. Full cheeks and a round face completed a list that diverges from the California-blond prototype.

Although Angelina Jolie was selected over several Lebanese actresses as a first choice for an icon of beauty in this same poll, Dr. Galadari pointed out that this actress has many of the features, including wide eyes, a straight nose, and full lips, that are consistent with traditional features of Arab beauty.

Perceptions of beauty are not just changing within ethnic groups but reflected in mass culture. Dr. Henry pointed to a published comparison of the “World’s Most Beautiful” list from People magazine in 2017 relative to 1990. Of the 50 celebrities on the list in 1990, 88% were Fitzpatrick skin types I-III. Only 12% were types IV-VI, which increased to almost 30% of the 135 celebrities on the list in 2017 (P = .01). In 1990, just one celebrity (2%) was of mixed race, which increased to 10.4% in 2017.

Among Hispanic women, the changes in attitude are perhaps best captured among younger relative to older patients requesting cosmetic work, according to Maritza I. Perez, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Connecticut, Farmington. She said that her younger patients are less likely to seek rhinoplasty and blepharoplasty relative to her older patients, a reflection perhaps of comfort with their natural looks.

However, “the celebration of Latinas as beautiful, seductive, and sexual is hardly new,” she said, indicating that younger Hispanic patients are probably not driven to modify their ethnic features because they are already widely admired. “Six of the 10 women crowned Miss Universe in the last decade were from Latin American countries,” she noted.

The general willingness of patients within ethnic groups and society as a whole to see ethnic features as admirable and attractive was generally regarded by all the panelists as a positive development.

Dr. Henry, who said she was “encouraged” by such trends as “the natural hair movement” and diminishing interest among her darker patients in lightening skin pigment, said, “I definitely see a change among my patients in regard to their goals.”

For clinicians offering consults to patients seeking cosmetic work, Dr. Henry recommended being aware and sensitive to this evolution in order to offer appropriate care.

Dr. Chiu, emphasizing the pride that many of her patients take in their Asian features, made the same recommendation. She credited globalization and social media for attitudes that have allowed an embrace of what are now far more inclusive standards of beauty.

Dr. Henry reports financial relationships with Allergan and Merz. Dr. Chiu has financial relationships with AbbVie, Cynosure, Merz, Revance, and Solta. Dr. Galadari reports financial relationships with nine pharmaceutical companies, including Allergan, Merz, Revance, and Fillmed Laboratories. Dr. Perez reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM SOC 2021

Workplace mistreatment common among emergency medicine residents

published online Aug. 19 in JAMA Network Open.

The survey of more than 6,000 residents found that almost 1 in 2 respondents had been exposed to some form of workplace mistreatment in the previous year, including gender and racial discrimination, physical abuse, or sexual harassment.

“The last study on mistreatment in EM residency training in the United States occurred more than 25 years ago,” said Michelle D. Lall, MD, associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “These findings provide a current look. Mistreatment occurs frequently in EM residency training nationally, and it occurs more frequently in women, racial/ethnic minorities, and those who identify as LGBTQ+,” Dr. Lall added. “Additionally, we found an association between experiencing mistreatment at least a few times per month and having suicidal thoughts.”

Negative sequelae from workplace mistreatment

Dr. Lall explained that workplace mistreatment and institutional responses to such behaviors have been linked to hostile work environments for physicians. In previous research, workplace mistreatment has been found to negatively affect individuals’ sense of self, a phenomenon that not only hindered professional productivity but also increased a variety of other negative factors, such as stress, job dissatisfaction, negative workplace behaviors, and turnover. Perhaps not surprisingly, workplace discrimination has also been shown to have negative effects on physical and mental health.

Despite such findings, little is known about the current state of workplace mistreatment among EM residents. This led the investigators to examine the prevalence, types, and sources of such perceived treatment during their training. In addition, the researchers assessed the association between mistreatment and suicidal ideation. Insights into these problems, they say, may spur leaders in the field to develop and implement strategies to help new physicians maintain their well-being throughout their careers.

“A 2019 study by Yue-Yung Hu and associates looked at discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residents, and they found that mistreatment occurs frequently among general surgery residents, especially women,” Dr. Lall said. “Our study group felt it was important to look at the rates of mistreatment among EM residents nationally in order to obtain baseline data and to use this data to identify and promote educational interventions to reduce workplace mistreatment.”

Emergency residents surveyed

To achieve these ends, Dr. Lall and colleagues sent a survey to all individuals enrolled in EM residencies accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education who had participated in the 2020 American Board of Emergency Medicine in-training examination. The 35-item multiple-choice survey asked residents to self-report the frequency, sources, and types of mistreatment they had experienced during their training. Suicidal thoughts were assessed by asking residents whether they had considered taking their own life.

Respondents categorized the frequency of mistreatment as never having occurred, having occurred a few times a year, a few times a month, a few times a week, or every day. The investigators created a composite indicator for the study’s primary comparisons that represented the maximum reported frequency of any single exposure. Responses were categorized according to the frequency of mistreatment exposure as either no exposure, exposures a few times per year, or exposures a few times or more per month (including a few times per week or every day).

Almost half report mistreatment

The survey was sent to 8,162 eligible residents in EM. Of those, 6,503 (79.7%) completed the entire survey. Respondents were primarily male (62.1%) and non-Hispanic White (64.0%); 2,620 residents (34.1%) were from other racial/ethnic groups. Of the respondents, 483 residents (6.6%) identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other (LGBTQ+); 5,951 residents (77.5%) were married or in a relationship.

It was found that 3,463 (45.1%) of participants reported having been exposed to some sort of workplace mistreatment during the most recent academic year. A common source of mistreatment was patients and/or their families. These caused a total of 1,234 events.

Gender discrimination was reported by 2,104 residents (29.5%), 1,635 of whom were women. The most common source of such discrimination was patients or patients’ family members (1,027 women; 184 men). Other sources included nurses or staff (331 women; 59 men).

Racial discrimination was common. It was reported by 1,284 residents; 907 residents were from racial/ethnic groups other than White. Among non-White racial/ethnic groups, 248 residents reported being exposed to racial discrimination at least a few times per month. The most common source of racial discrimination was patients or their family members.

Discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity was reported by 220 residents. Once again, the majority of LGBTQ+ residents indicated that patients or their families were the primary source. More than 1,000 residents (n = 1047) reported sexual harassment; among these residents, 721 were women. Patients and/or patients’ family members were the most common source of such discrimination, followed by nurses and staff.

A total of 2,069 residents reported verbal or emotional abuse, including 806 women and 1,212 men. Patients/patients’ family members were the most common source, followed by attending physicians. Physical abuse was reported by 331 respondents. Physical abuse was primarily attributed to patients/patients’ families.

Suicidal thoughts were reported by 178 residents; the prevalence was comparable with respect to gender (2.4% men; 2.4% women) and race/ethnicity (2.4% non-Hispanic White; 2.7% other racial/ethnic groups). Adjusted models revealed that the prevalence for suicidal thoughts was greater among residents who identified as LGBTQ+ (odds ratio [OR], 2.04; 99% confidence interval, 1.04-3.99). An association was found between suicidal thoughts and having experienced mistreatment at least a few times each month (OR, 5.83; 99% CI, 3.70-9.20).

Identifying sources key to stemming mistreatment

These findings, the researchers say, demonstrate the alarming frequency with which workplace mistreatment occurs for EM residents. The survey also found that such mistreatment was more common among residents from racial/ethnic minority populations, women, and residents who identify as LGBTQ+. Perhaps most disturbingly, the occurrence of workplace mistreatment was found to be associated with suicidal thoughts.

The researchers say that although it is likely that residents in many medical specialties experience similar mistreatment to some degree, such treatment should never be considered acceptable. Indeed, Dr. Lall said that identifying sources of mistreatment may help both institutions and individuals determine interventions necessary for improving the well-being of EM residents.

“The first step is recognizing, based on our data, that mistreatment is experienced frequently in EM training in the United States,” she said. “Future qualitative studies of residents and program leaders may help identify which systems, programs, or cultural factors were associated with lower rates of mistreatment in some institutions and higher rates in others.

“Identifying these factors and developing and promoting best practices to minimize workplace mistreatment during residency may help optimize the professional career experience and improve the personal and professional well-being of physicians throughout their lives,” Dr. Lall added.

Commenting on the findings for this article, Karl Y. Bilimoria, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, noted that these surveys clearly lay out actionable opportunities to improve trainee mistreatment. “Given that much of the mistreatment of EM residents comes from patients and families, the solutions must be appropriately tailored to address those sources,” Dr. Bilimoria noted.

“Programs need to actively work even more to protect their trainees and faculty from this mistreatment, as it has severe effects and often leads to, or worsens, burnout,” he added.

Funding for statistical analysis was provided by the American Board of Emergency Medicine. Dr. Lall and Dr. Bilimoria reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published online Aug. 19 in JAMA Network Open.

The survey of more than 6,000 residents found that almost 1 in 2 respondents had been exposed to some form of workplace mistreatment in the previous year, including gender and racial discrimination, physical abuse, or sexual harassment.

“The last study on mistreatment in EM residency training in the United States occurred more than 25 years ago,” said Michelle D. Lall, MD, associate professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta. “These findings provide a current look. Mistreatment occurs frequently in EM residency training nationally, and it occurs more frequently in women, racial/ethnic minorities, and those who identify as LGBTQ+,” Dr. Lall added. “Additionally, we found an association between experiencing mistreatment at least a few times per month and having suicidal thoughts.”

Negative sequelae from workplace mistreatment

Dr. Lall explained that workplace mistreatment and institutional responses to such behaviors have been linked to hostile work environments for physicians. In previous research, workplace mistreatment has been found to negatively affect individuals’ sense of self, a phenomenon that not only hindered professional productivity but also increased a variety of other negative factors, such as stress, job dissatisfaction, negative workplace behaviors, and turnover. Perhaps not surprisingly, workplace discrimination has also been shown to have negative effects on physical and mental health.

Despite such findings, little is known about the current state of workplace mistreatment among EM residents. This led the investigators to examine the prevalence, types, and sources of such perceived treatment during their training. In addition, the researchers assessed the association between mistreatment and suicidal ideation. Insights into these problems, they say, may spur leaders in the field to develop and implement strategies to help new physicians maintain their well-being throughout their careers.

“A 2019 study by Yue-Yung Hu and associates looked at discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residents, and they found that mistreatment occurs frequently among general surgery residents, especially women,” Dr. Lall said. “Our study group felt it was important to look at the rates of mistreatment among EM residents nationally in order to obtain baseline data and to use this data to identify and promote educational interventions to reduce workplace mistreatment.”

Emergency residents surveyed

To achieve these ends, Dr. Lall and colleagues sent a survey to all individuals enrolled in EM residencies accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education who had participated in the 2020 American Board of Emergency Medicine in-training examination. The 35-item multiple-choice survey asked residents to self-report the frequency, sources, and types of mistreatment they had experienced during their training. Suicidal thoughts were assessed by asking residents whether they had considered taking their own life.

Respondents categorized the frequency of mistreatment as never having occurred, having occurred a few times a year, a few times a month, a few times a week, or every day. The investigators created a composite indicator for the study’s primary comparisons that represented the maximum reported frequency of any single exposure. Responses were categorized according to the frequency of mistreatment exposure as either no exposure, exposures a few times per year, or exposures a few times or more per month (including a few times per week or every day).

Almost half report mistreatment

The survey was sent to 8,162 eligible residents in EM. Of those, 6,503 (79.7%) completed the entire survey. Respondents were primarily male (62.1%) and non-Hispanic White (64.0%); 2,620 residents (34.1%) were from other racial/ethnic groups. Of the respondents, 483 residents (6.6%) identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or other (LGBTQ+); 5,951 residents (77.5%) were married or in a relationship.

It was found that 3,463 (45.1%) of participants reported having been exposed to some sort of workplace mistreatment during the most recent academic year. A common source of mistreatment was patients and/or their families. These caused a total of 1,234 events.

Gender discrimination was reported by 2,104 residents (29.5%), 1,635 of whom were women. The most common source of such discrimination was patients or patients’ family members (1,027 women; 184 men). Other sources included nurses or staff (331 women; 59 men).

Racial discrimination was common. It was reported by 1,284 residents; 907 residents were from racial/ethnic groups other than White. Among non-White racial/ethnic groups, 248 residents reported being exposed to racial discrimination at least a few times per month. The most common source of racial discrimination was patients or their family members.

Discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity was reported by 220 residents. Once again, the majority of LGBTQ+ residents indicated that patients or their families were the primary source. More than 1,000 residents (n = 1047) reported sexual harassment; among these residents, 721 were women. Patients and/or patients’ family members were the most common source of such discrimination, followed by nurses and staff.

A total of 2,069 residents reported verbal or emotional abuse, including 806 women and 1,212 men. Patients/patients’ family members were the most common source, followed by attending physicians. Physical abuse was reported by 331 respondents. Physical abuse was primarily attributed to patients/patients’ families.

Suicidal thoughts were reported by 178 residents; the prevalence was comparable with respect to gender (2.4% men; 2.4% women) and race/ethnicity (2.4% non-Hispanic White; 2.7% other racial/ethnic groups). Adjusted models revealed that the prevalence for suicidal thoughts was greater among residents who identified as LGBTQ+ (odds ratio [OR], 2.04; 99% confidence interval, 1.04-3.99). An association was found between suicidal thoughts and having experienced mistreatment at least a few times each month (OR, 5.83; 99% CI, 3.70-9.20).

Identifying sources key to stemming mistreatment

These findings, the researchers say, demonstrate the alarming frequency with which workplace mistreatment occurs for EM residents. The survey also found that such mistreatment was more common among residents from racial/ethnic minority populations, women, and residents who identify as LGBTQ+. Perhaps most disturbingly, the occurrence of workplace mistreatment was found to be associated with suicidal thoughts.