User login

Spanish-speaking navigators show Hispanic patients path to CRC screening

A Spanish-speaking patient navigator dramatically increased the percentage of Hispanics undergoing colorectal screening with colonoscopies in Providence, R.I.

Screening colonoscopies are a well-established approach to reducing colorectal cancer mortality by identifying and removing polyps. However, Hispanics in the United States lag behind the general population in completion rates for screening colonoscopies.

“Starting colorectal cancer colonoscopy screening at age 45 saves lives. But this life-saving procedure is underutilized by certain populations, not only because of limited access to care but because of cultural, language, and educational barriers that exist,” Abdul Saied Calvino, MD, MPH, program director of the Complex General Surgical Oncology Fellowship at Roger Williams Medical Center, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

Tailored patient navigation is effective but has not been widely adopted. The new study is one of the first to look at the ‘real-life’ impact of these types of programs in the Hispanic population, Dr. Calvino and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States overall and the third-most diagnosed cancer site, according to the American Cancer Society. Among Hispanics, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality and the second-most diagnosed site of malignancy.

Dr. Calvino and his colleagues sought to learn if a culturally tailored patient navigation program could improve rates of screening colonoscopies among Hispanic residents in Providence.

The hospital hired a dedicated Spanish-speaking navigator/coordinator and enrolled 698 men and women into the program.

The navigator sent introductory letters in Spanish to study participants, made phone calls to educate patients about the importance of cancer screening, and called again to ensure that all potential barriers to colonoscopy were overcome, Dr. Calvino said. Colonoscopy completion, cancellations, and no-shows were recorded. Participants were followed for 28 months.

The program proved highly successful, according to the researchers. At the end of the study period, 85% of patients – exceeding the national goal of 80% set by the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable – had completed testing, with no differences between men and women; the cancellation rate was 9% and only 6% of patients failed to show up for endoscopy.*

Among the group that underwent colonoscopy, 254 (43%) had polyps removed and eight (1.3%) required colectomy, the researchers reported. Five patients (0.8%) were diagnosed with malignancy.

Dr. Calvino attributed the 15% combined rate of no-shows and cancellations to the cost of the procedure (copayment, out-of-pocket expense, and loss of wages) and the inability to follow-up with those patients. He added that 90% of those who completed the procedure said that without the patient navigation program they would not have completed the screening colonoscopies.

Aimee Afable, PhD, MPH, an expert on health disparities and immigrant health at Downstate Health Science University, New York, called the new study small but “important.”

Dr. Afable said strong evidence supports the ability of patient navigation programs to improve the reach and impact of screening programs aimed at the underserved. However, hospitals typically do not adequately fund such initiatives. (Dr. Calvino said the program at Roger Williams started with a grant from the OLDCO Foundation and is now supported by his institution.)

“In 2022, post-COVID, it is common to see health care support staff leaving institutions, hospitals because they’re not being paid well, and they are overburdened,” Dr. Afable told this news organization. “Patient navigation is not, unfortunately, a routine part of health care in the U.S. despite its central role in ensuring continuity of care.”

Funding for the study was provided by a grant from the OLDCO Foundation. Coauthor John C. Hardaway, MD, PhD, reports being a cancer liaison physician for the American College of Surgeons. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Afable has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 2/9/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the group that set the national screening goal.

This article was updated 2/18/22.

A Spanish-speaking patient navigator dramatically increased the percentage of Hispanics undergoing colorectal screening with colonoscopies in Providence, R.I.

Screening colonoscopies are a well-established approach to reducing colorectal cancer mortality by identifying and removing polyps. However, Hispanics in the United States lag behind the general population in completion rates for screening colonoscopies.

“Starting colorectal cancer colonoscopy screening at age 45 saves lives. But this life-saving procedure is underutilized by certain populations, not only because of limited access to care but because of cultural, language, and educational barriers that exist,” Abdul Saied Calvino, MD, MPH, program director of the Complex General Surgical Oncology Fellowship at Roger Williams Medical Center, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

Tailored patient navigation is effective but has not been widely adopted. The new study is one of the first to look at the ‘real-life’ impact of these types of programs in the Hispanic population, Dr. Calvino and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States overall and the third-most diagnosed cancer site, according to the American Cancer Society. Among Hispanics, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality and the second-most diagnosed site of malignancy.

Dr. Calvino and his colleagues sought to learn if a culturally tailored patient navigation program could improve rates of screening colonoscopies among Hispanic residents in Providence.

The hospital hired a dedicated Spanish-speaking navigator/coordinator and enrolled 698 men and women into the program.

The navigator sent introductory letters in Spanish to study participants, made phone calls to educate patients about the importance of cancer screening, and called again to ensure that all potential barriers to colonoscopy were overcome, Dr. Calvino said. Colonoscopy completion, cancellations, and no-shows were recorded. Participants were followed for 28 months.

The program proved highly successful, according to the researchers. At the end of the study period, 85% of patients – exceeding the national goal of 80% set by the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable – had completed testing, with no differences between men and women; the cancellation rate was 9% and only 6% of patients failed to show up for endoscopy.*

Among the group that underwent colonoscopy, 254 (43%) had polyps removed and eight (1.3%) required colectomy, the researchers reported. Five patients (0.8%) were diagnosed with malignancy.

Dr. Calvino attributed the 15% combined rate of no-shows and cancellations to the cost of the procedure (copayment, out-of-pocket expense, and loss of wages) and the inability to follow-up with those patients. He added that 90% of those who completed the procedure said that without the patient navigation program they would not have completed the screening colonoscopies.

Aimee Afable, PhD, MPH, an expert on health disparities and immigrant health at Downstate Health Science University, New York, called the new study small but “important.”

Dr. Afable said strong evidence supports the ability of patient navigation programs to improve the reach and impact of screening programs aimed at the underserved. However, hospitals typically do not adequately fund such initiatives. (Dr. Calvino said the program at Roger Williams started with a grant from the OLDCO Foundation and is now supported by his institution.)

“In 2022, post-COVID, it is common to see health care support staff leaving institutions, hospitals because they’re not being paid well, and they are overburdened,” Dr. Afable told this news organization. “Patient navigation is not, unfortunately, a routine part of health care in the U.S. despite its central role in ensuring continuity of care.”

Funding for the study was provided by a grant from the OLDCO Foundation. Coauthor John C. Hardaway, MD, PhD, reports being a cancer liaison physician for the American College of Surgeons. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Afable has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 2/9/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the group that set the national screening goal.

This article was updated 2/18/22.

A Spanish-speaking patient navigator dramatically increased the percentage of Hispanics undergoing colorectal screening with colonoscopies in Providence, R.I.

Screening colonoscopies are a well-established approach to reducing colorectal cancer mortality by identifying and removing polyps. However, Hispanics in the United States lag behind the general population in completion rates for screening colonoscopies.

“Starting colorectal cancer colonoscopy screening at age 45 saves lives. But this life-saving procedure is underutilized by certain populations, not only because of limited access to care but because of cultural, language, and educational barriers that exist,” Abdul Saied Calvino, MD, MPH, program director of the Complex General Surgical Oncology Fellowship at Roger Williams Medical Center, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

Tailored patient navigation is effective but has not been widely adopted. The new study is one of the first to look at the ‘real-life’ impact of these types of programs in the Hispanic population, Dr. Calvino and his colleagues reported in the journal Cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States overall and the third-most diagnosed cancer site, according to the American Cancer Society. Among Hispanics, colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer mortality and the second-most diagnosed site of malignancy.

Dr. Calvino and his colleagues sought to learn if a culturally tailored patient navigation program could improve rates of screening colonoscopies among Hispanic residents in Providence.

The hospital hired a dedicated Spanish-speaking navigator/coordinator and enrolled 698 men and women into the program.

The navigator sent introductory letters in Spanish to study participants, made phone calls to educate patients about the importance of cancer screening, and called again to ensure that all potential barriers to colonoscopy were overcome, Dr. Calvino said. Colonoscopy completion, cancellations, and no-shows were recorded. Participants were followed for 28 months.

The program proved highly successful, according to the researchers. At the end of the study period, 85% of patients – exceeding the national goal of 80% set by the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable – had completed testing, with no differences between men and women; the cancellation rate was 9% and only 6% of patients failed to show up for endoscopy.*

Among the group that underwent colonoscopy, 254 (43%) had polyps removed and eight (1.3%) required colectomy, the researchers reported. Five patients (0.8%) were diagnosed with malignancy.

Dr. Calvino attributed the 15% combined rate of no-shows and cancellations to the cost of the procedure (copayment, out-of-pocket expense, and loss of wages) and the inability to follow-up with those patients. He added that 90% of those who completed the procedure said that without the patient navigation program they would not have completed the screening colonoscopies.

Aimee Afable, PhD, MPH, an expert on health disparities and immigrant health at Downstate Health Science University, New York, called the new study small but “important.”

Dr. Afable said strong evidence supports the ability of patient navigation programs to improve the reach and impact of screening programs aimed at the underserved. However, hospitals typically do not adequately fund such initiatives. (Dr. Calvino said the program at Roger Williams started with a grant from the OLDCO Foundation and is now supported by his institution.)

“In 2022, post-COVID, it is common to see health care support staff leaving institutions, hospitals because they’re not being paid well, and they are overburdened,” Dr. Afable told this news organization. “Patient navigation is not, unfortunately, a routine part of health care in the U.S. despite its central role in ensuring continuity of care.”

Funding for the study was provided by a grant from the OLDCO Foundation. Coauthor John C. Hardaway, MD, PhD, reports being a cancer liaison physician for the American College of Surgeons. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Afable has no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 2/9/22: An earlier version of this article misidentified the group that set the national screening goal.

This article was updated 2/18/22.

LGBTQ parents fare worse giving birth

Members of the LGBTQ community who give birth appear to have a greater risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and postpartum hemorrhage, according to new research presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“Our study found that birthing patients in likely sexual and gender minority partnerships experienced disparities in clinical outcomes,” Stephanie Leonard, PhD, an epidemiology and biostatistics instructor at the Stanford (Calif.) University division of maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics, told attendees at the meeting. The disparities are likely because of various social determinants and possibly higher use of assisted reproductive technology (ART). The findings establish “how these are significant disparities that have been largely overlooked and set the groundwork for doing further research on maybe ways that we can improve the inclusivity of obstetric care.”

Jenny Mei, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the research, said the findings were “overall unfortunate but not surprising given the existing studies looking at LGBTQ patients and their poorer health outcomes, largely due to lack of access to health care and discrimination in the health care setting.”

Dr. Leonard described the societal, interpersonal, and individual factors that can contribute to health disparities among gender and sexual minority patients.

“At the societal level, there are expectations of what it means to be pregnant, to give birth, and to be a parent. At the community level, there’s the clinical care environment, and at the interpersonal level, there’s an obstetrician’s relationship with the patient,” Dr. Leonard said. “At the individual level, most notably is minority stress, the biological effects of the chronic experience of discrimination.”

It has historically been difficult to collect data on this patient population, but a change in the design of the California birth certificate made it possible to gather more data than previously possible. The updated California birth certificate, issued in 2016, allows the parent not giving birth to check off whether they are the child’s mother, father, parent, or “not specified” instead of defaulting to “father.” In addition, the parent giving birth can select mother, father, parent or not specified instead of being “mother” by default.

The researchers classified sexual and gender minority (SGM) partnerships as those in which the parent giving birth was identified as the father and those where both parents were identified as mothers. Non-SGM minority partnerships were those in which the birthing parent was identified as the mother and the nonbirthing parent was identified as the father.

The population-based cohort study included data from all live birth hospitalizations from 2016-2019 in California, whose annual births represent one in eight babies born each year in the United States. The population of SGM patients different significantly from the non-SGM population in nearly every demographic and clinical factor except rates of pre-existing diabetes. For example, 42% of the SGM birthing patients were age 35 or older, compared with 23% of the non-SGM patients.

SGM patients were more likely to be born in the United States, were more likely to be White, and were less likely to be Asian or Hispanic. SGM patients had higher education levels and were more likely to have private insurance. They were also more likely to be nulliparous and have chronic hypertension. Average body mass index for SGM patients was 33 kg/m2, compared with 30 for non-SGM patients. SGM patients were also much more likely to have multifetal gestation: 7.1% of SGM patients versus 1.5% of non-SGM patients.

In terms of clinical outcomes, 14% of SGM patients had hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, compared with 8% of non-SGM patients. Before adjustment for potential confounders, SGM patients were also twice as likely to have postpartum hemorrhage (8% vs. 4% in non-SGM patients) and postterm birth at 42-44 weeks (0.6% vs 0.3% in non-SGM patients).

“Having increased postterm birth is a matter of declining induction of labor, as it is recommended to have an induction by 41 weeks of gestation in general,” Dr. Mei said in an interview. “It is also possible this patient cohort faces more barriers in access to care and possible discrimination as sexual/gender minority patients.”

Rates of severe preeclampsia, induction of labor, cesarean delivery, preterm birth, low birth weight, and a low Apgar score were also higher among SGM patients, but these associations were no longer significant after adjustment for age, education, payment method, parity, prepregnancy weight, comorbidities, and multifetal gestation. The difference in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, postpartum hemorrhage, and postterm birth remained statistically significant after adjustment.

Past research has shown that only about a third of cisgender female same-sex marriages used ART, so the disparities cannot be completely explained by ART use, Dr. Leonard said.

“I think the main drivers are structural disparities,” Dr. Leonard said. “Every obstetric clinic is focused in a way that’s about mother-father, and many people who don’t feel like they fit into that paradigm feel excluded and disengage with health care.”

Elliott Main, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University and coauthor of the study noted that discrimination and stigma likely play a substantial role in the disparities.

“Sexual and/or gender minority people face this discrimination at structural and interpersonal levels on a regular basis, which can lead to chronic stress and its harmful physical effects as well as lower-quality health care,” Dr. Main said in an interview.

Another coauthor, Juno Obedin-Maliver, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford, emphasized how much room for improvement exists in care for SGM obstetric patients.

“We hope that this study brings needed attention to the disparities in perinatal health experienced by sexual and/or gender minority people,” Dr. Obedin-Maliver said. “There is much we can do to better understand the family building goals of sexual and/or gender minority people and help those to be achieved with healthy outcomes for parents and their children.”

One limitation of the study is that it’s possible to misclassify individuals using the birth certificate data, and not everyone may be comfortable selecting the box that accurately represents their identity, particularly if they aren’t “out” or fear discrimination or stigma, so the population may underrepresent the actual numbers of sexual and gender minority individuals giving birth. Dr. Mei added that it would be helpful to see data on neonatal ICU admissions and use of ART.

It’s difficult to say how generalizable the findings are, Dr. Mei said. “It is possible the findings would be more exaggerated in the rest of the country outside of California, if we assume there is potentially lower health access and more stigma.” The fact that California offers different gender options for the birthing and nonbirthing parent is, by itself, an indication of a potentially more accepting social environment than might be found in other states.

”The take-home message is that this patient population is higher risk, likely partially due to baseline increased risk factors, such as older maternal age and likely use of ART, and partially due to possible lack of health access and stigma,” Dr. Mei said. “Health care providers should be notably cognizant of these increased risks, particularly in the psychosocial context and make efforts to reduce those burdens as much as possible.”

The research was funded by the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. Dr. Obedin-Maliver has consulted for Sage Therapeutics, Ibis Reproductive Health, and Hims. Dr. Mei and the other authors had no disclosures.

Members of the LGBTQ community who give birth appear to have a greater risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and postpartum hemorrhage, according to new research presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“Our study found that birthing patients in likely sexual and gender minority partnerships experienced disparities in clinical outcomes,” Stephanie Leonard, PhD, an epidemiology and biostatistics instructor at the Stanford (Calif.) University division of maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics, told attendees at the meeting. The disparities are likely because of various social determinants and possibly higher use of assisted reproductive technology (ART). The findings establish “how these are significant disparities that have been largely overlooked and set the groundwork for doing further research on maybe ways that we can improve the inclusivity of obstetric care.”

Jenny Mei, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the research, said the findings were “overall unfortunate but not surprising given the existing studies looking at LGBTQ patients and their poorer health outcomes, largely due to lack of access to health care and discrimination in the health care setting.”

Dr. Leonard described the societal, interpersonal, and individual factors that can contribute to health disparities among gender and sexual minority patients.

“At the societal level, there are expectations of what it means to be pregnant, to give birth, and to be a parent. At the community level, there’s the clinical care environment, and at the interpersonal level, there’s an obstetrician’s relationship with the patient,” Dr. Leonard said. “At the individual level, most notably is minority stress, the biological effects of the chronic experience of discrimination.”

It has historically been difficult to collect data on this patient population, but a change in the design of the California birth certificate made it possible to gather more data than previously possible. The updated California birth certificate, issued in 2016, allows the parent not giving birth to check off whether they are the child’s mother, father, parent, or “not specified” instead of defaulting to “father.” In addition, the parent giving birth can select mother, father, parent or not specified instead of being “mother” by default.

The researchers classified sexual and gender minority (SGM) partnerships as those in which the parent giving birth was identified as the father and those where both parents were identified as mothers. Non-SGM minority partnerships were those in which the birthing parent was identified as the mother and the nonbirthing parent was identified as the father.

The population-based cohort study included data from all live birth hospitalizations from 2016-2019 in California, whose annual births represent one in eight babies born each year in the United States. The population of SGM patients different significantly from the non-SGM population in nearly every demographic and clinical factor except rates of pre-existing diabetes. For example, 42% of the SGM birthing patients were age 35 or older, compared with 23% of the non-SGM patients.

SGM patients were more likely to be born in the United States, were more likely to be White, and were less likely to be Asian or Hispanic. SGM patients had higher education levels and were more likely to have private insurance. They were also more likely to be nulliparous and have chronic hypertension. Average body mass index for SGM patients was 33 kg/m2, compared with 30 for non-SGM patients. SGM patients were also much more likely to have multifetal gestation: 7.1% of SGM patients versus 1.5% of non-SGM patients.

In terms of clinical outcomes, 14% of SGM patients had hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, compared with 8% of non-SGM patients. Before adjustment for potential confounders, SGM patients were also twice as likely to have postpartum hemorrhage (8% vs. 4% in non-SGM patients) and postterm birth at 42-44 weeks (0.6% vs 0.3% in non-SGM patients).

“Having increased postterm birth is a matter of declining induction of labor, as it is recommended to have an induction by 41 weeks of gestation in general,” Dr. Mei said in an interview. “It is also possible this patient cohort faces more barriers in access to care and possible discrimination as sexual/gender minority patients.”

Rates of severe preeclampsia, induction of labor, cesarean delivery, preterm birth, low birth weight, and a low Apgar score were also higher among SGM patients, but these associations were no longer significant after adjustment for age, education, payment method, parity, prepregnancy weight, comorbidities, and multifetal gestation. The difference in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, postpartum hemorrhage, and postterm birth remained statistically significant after adjustment.

Past research has shown that only about a third of cisgender female same-sex marriages used ART, so the disparities cannot be completely explained by ART use, Dr. Leonard said.

“I think the main drivers are structural disparities,” Dr. Leonard said. “Every obstetric clinic is focused in a way that’s about mother-father, and many people who don’t feel like they fit into that paradigm feel excluded and disengage with health care.”

Elliott Main, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University and coauthor of the study noted that discrimination and stigma likely play a substantial role in the disparities.

“Sexual and/or gender minority people face this discrimination at structural and interpersonal levels on a regular basis, which can lead to chronic stress and its harmful physical effects as well as lower-quality health care,” Dr. Main said in an interview.

Another coauthor, Juno Obedin-Maliver, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford, emphasized how much room for improvement exists in care for SGM obstetric patients.

“We hope that this study brings needed attention to the disparities in perinatal health experienced by sexual and/or gender minority people,” Dr. Obedin-Maliver said. “There is much we can do to better understand the family building goals of sexual and/or gender minority people and help those to be achieved with healthy outcomes for parents and their children.”

One limitation of the study is that it’s possible to misclassify individuals using the birth certificate data, and not everyone may be comfortable selecting the box that accurately represents their identity, particularly if they aren’t “out” or fear discrimination or stigma, so the population may underrepresent the actual numbers of sexual and gender minority individuals giving birth. Dr. Mei added that it would be helpful to see data on neonatal ICU admissions and use of ART.

It’s difficult to say how generalizable the findings are, Dr. Mei said. “It is possible the findings would be more exaggerated in the rest of the country outside of California, if we assume there is potentially lower health access and more stigma.” The fact that California offers different gender options for the birthing and nonbirthing parent is, by itself, an indication of a potentially more accepting social environment than might be found in other states.

”The take-home message is that this patient population is higher risk, likely partially due to baseline increased risk factors, such as older maternal age and likely use of ART, and partially due to possible lack of health access and stigma,” Dr. Mei said. “Health care providers should be notably cognizant of these increased risks, particularly in the psychosocial context and make efforts to reduce those burdens as much as possible.”

The research was funded by the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. Dr. Obedin-Maliver has consulted for Sage Therapeutics, Ibis Reproductive Health, and Hims. Dr. Mei and the other authors had no disclosures.

Members of the LGBTQ community who give birth appear to have a greater risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and postpartum hemorrhage, according to new research presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“Our study found that birthing patients in likely sexual and gender minority partnerships experienced disparities in clinical outcomes,” Stephanie Leonard, PhD, an epidemiology and biostatistics instructor at the Stanford (Calif.) University division of maternal-fetal medicine and obstetrics, told attendees at the meeting. The disparities are likely because of various social determinants and possibly higher use of assisted reproductive technology (ART). The findings establish “how these are significant disparities that have been largely overlooked and set the groundwork for doing further research on maybe ways that we can improve the inclusivity of obstetric care.”

Jenny Mei, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation but was not involved in the research, said the findings were “overall unfortunate but not surprising given the existing studies looking at LGBTQ patients and their poorer health outcomes, largely due to lack of access to health care and discrimination in the health care setting.”

Dr. Leonard described the societal, interpersonal, and individual factors that can contribute to health disparities among gender and sexual minority patients.

“At the societal level, there are expectations of what it means to be pregnant, to give birth, and to be a parent. At the community level, there’s the clinical care environment, and at the interpersonal level, there’s an obstetrician’s relationship with the patient,” Dr. Leonard said. “At the individual level, most notably is minority stress, the biological effects of the chronic experience of discrimination.”

It has historically been difficult to collect data on this patient population, but a change in the design of the California birth certificate made it possible to gather more data than previously possible. The updated California birth certificate, issued in 2016, allows the parent not giving birth to check off whether they are the child’s mother, father, parent, or “not specified” instead of defaulting to “father.” In addition, the parent giving birth can select mother, father, parent or not specified instead of being “mother” by default.

The researchers classified sexual and gender minority (SGM) partnerships as those in which the parent giving birth was identified as the father and those where both parents were identified as mothers. Non-SGM minority partnerships were those in which the birthing parent was identified as the mother and the nonbirthing parent was identified as the father.

The population-based cohort study included data from all live birth hospitalizations from 2016-2019 in California, whose annual births represent one in eight babies born each year in the United States. The population of SGM patients different significantly from the non-SGM population in nearly every demographic and clinical factor except rates of pre-existing diabetes. For example, 42% of the SGM birthing patients were age 35 or older, compared with 23% of the non-SGM patients.

SGM patients were more likely to be born in the United States, were more likely to be White, and were less likely to be Asian or Hispanic. SGM patients had higher education levels and were more likely to have private insurance. They were also more likely to be nulliparous and have chronic hypertension. Average body mass index for SGM patients was 33 kg/m2, compared with 30 for non-SGM patients. SGM patients were also much more likely to have multifetal gestation: 7.1% of SGM patients versus 1.5% of non-SGM patients.

In terms of clinical outcomes, 14% of SGM patients had hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, compared with 8% of non-SGM patients. Before adjustment for potential confounders, SGM patients were also twice as likely to have postpartum hemorrhage (8% vs. 4% in non-SGM patients) and postterm birth at 42-44 weeks (0.6% vs 0.3% in non-SGM patients).

“Having increased postterm birth is a matter of declining induction of labor, as it is recommended to have an induction by 41 weeks of gestation in general,” Dr. Mei said in an interview. “It is also possible this patient cohort faces more barriers in access to care and possible discrimination as sexual/gender minority patients.”

Rates of severe preeclampsia, induction of labor, cesarean delivery, preterm birth, low birth weight, and a low Apgar score were also higher among SGM patients, but these associations were no longer significant after adjustment for age, education, payment method, parity, prepregnancy weight, comorbidities, and multifetal gestation. The difference in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, postpartum hemorrhage, and postterm birth remained statistically significant after adjustment.

Past research has shown that only about a third of cisgender female same-sex marriages used ART, so the disparities cannot be completely explained by ART use, Dr. Leonard said.

“I think the main drivers are structural disparities,” Dr. Leonard said. “Every obstetric clinic is focused in a way that’s about mother-father, and many people who don’t feel like they fit into that paradigm feel excluded and disengage with health care.”

Elliott Main, MD, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University and coauthor of the study noted that discrimination and stigma likely play a substantial role in the disparities.

“Sexual and/or gender minority people face this discrimination at structural and interpersonal levels on a regular basis, which can lead to chronic stress and its harmful physical effects as well as lower-quality health care,” Dr. Main said in an interview.

Another coauthor, Juno Obedin-Maliver, MD, an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford, emphasized how much room for improvement exists in care for SGM obstetric patients.

“We hope that this study brings needed attention to the disparities in perinatal health experienced by sexual and/or gender minority people,” Dr. Obedin-Maliver said. “There is much we can do to better understand the family building goals of sexual and/or gender minority people and help those to be achieved with healthy outcomes for parents and their children.”

One limitation of the study is that it’s possible to misclassify individuals using the birth certificate data, and not everyone may be comfortable selecting the box that accurately represents their identity, particularly if they aren’t “out” or fear discrimination or stigma, so the population may underrepresent the actual numbers of sexual and gender minority individuals giving birth. Dr. Mei added that it would be helpful to see data on neonatal ICU admissions and use of ART.

It’s difficult to say how generalizable the findings are, Dr. Mei said. “It is possible the findings would be more exaggerated in the rest of the country outside of California, if we assume there is potentially lower health access and more stigma.” The fact that California offers different gender options for the birthing and nonbirthing parent is, by itself, an indication of a potentially more accepting social environment than might be found in other states.

”The take-home message is that this patient population is higher risk, likely partially due to baseline increased risk factors, such as older maternal age and likely use of ART, and partially due to possible lack of health access and stigma,” Dr. Mei said. “Health care providers should be notably cognizant of these increased risks, particularly in the psychosocial context and make efforts to reduce those burdens as much as possible.”

The research was funded by the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. Dr. Obedin-Maliver has consulted for Sage Therapeutics, Ibis Reproductive Health, and Hims. Dr. Mei and the other authors had no disclosures.

FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

How to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion in dermatology: Recommendations from an expert panel

– so he launched community outreach efforts with local businesses to attract patients from diverse backgrounds.

“For instance, I worked with U.S. Bank to give lectures on minorities in medicine and talked about outreach options and possible ways to include more ethnicities in medicine overall,” Dr. Qutub said during a panel discussion on equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) that took place at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “I also did outreach with medical clinics in the area. Once patients are referred to you, they start to talk to people in their communities about you, and before you know it, you get people from their church and family members in your clinic.”

Dr. Qutub, who is ODAC’s director of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, kept EDI in mind when hiring staff for his practice, “to include candidates with varying experiences and backgrounds,” he said. “The idea was to make sure that when patients came into the clinic, they saw a varied group of individuals that were working together to help improve their health care outcomes. I found that made patients more comfortable in the clinic. It’s also important to have that representation daily in a larger setting like residency programs or multispecialty groups.”

Educational resources

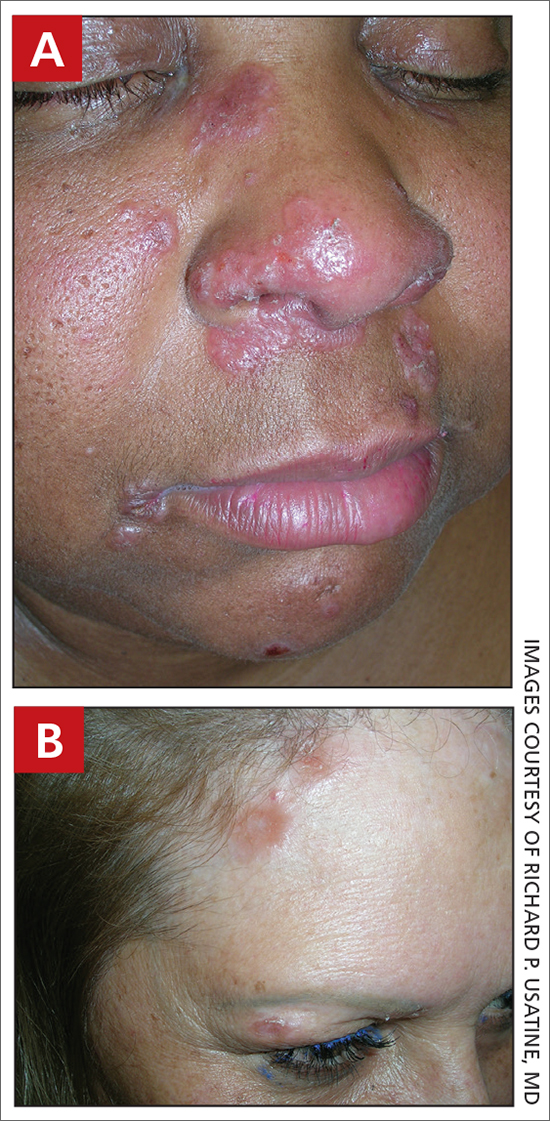

Another panelist, Adam Friedman, MD, emphasized inclusivity of educational resources to ensure a dermatology workforce that can take care of all patients. “How can we expect the dermatology community to be able to treat anyone who comes through the door of their clinic if we don’t provide the resources that highlight and showcase the nuances and the diversity that skin disease has to offer?” asked Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “It comes down to educational tools and being purposeful when you’re putting together a talk or writing a paper, to be inclusive and have that on the top of your mind. It’s about saying right here, right now, we have to purposefully make a decision to be inclusive, to be welcoming to all so that we can practice at the highest level of our calling to treat everyone effectively and equitably.”

A unique feature of the atlas “is that we have taken multiple skin conditions, even common features such as erythema, and placed different skin tones side by side at the same angle to appreciate the full spectrum, and highlight those nuances,” Dr. Friedman said. “When you’re in clinic, when you see even common things like acne or seborrheic dermatitis,” he recommended taking photos to create a repository, “because you never know when that will be helpful when you want to show a medical student or a patient what something can look like on someone with a similar skin tone, or even to share with them how diverse skin conditions can appear across populations.”

Clinical research

Another way to help close racial gaps in dermatology is to improve access to mentorships and clinical research, according to panelist Chesahna Kindred, MD, of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md. “We should be thoroughly embarrassed by the lack of diversity in our clinical trials,” she said.

In her role as chair of the dermatology section of the National Medical Association (NMA Derm), Dr. Kindred helped launch the NMA Derm research committee, which trains members to run clinical trials in their practices – an undertaking that was largely prompted by claims from pharmaceutical industry representatives that they struggle to find Black participants for clinical trials. “The truth of the matter is, if a Black patient doesn’t choose to go to Dr. Smith as a patient, they’re certainly not going to choose to go to Dr. Smith as a research participant,” Dr. Kindred said. “We have to meet those diverse populations where they are. By and large for Black patients, those are Black dermatologists.

In addition to meeting with primary investigators, she has been meeting with industry representatives, who she said are very interested in improving clinical trial diversity. “When a trial does not include a diverse population, we can call it out and say it is subpar,” she said.

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration announced the availability of a guidance document, “Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations – Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs,” which includes recommendations for sponsors on how to increase enrollment of underrepresented populations in their clinical trials of medical products.

Dr. Kindred has created a clinical research unit in her own practice, in partnership with Howard University’s department of dermatology and NMA Dermatology.

Studies Dr. Kindred is involved with include those looking at the relationship between hair care products targeted to Black women and the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA). CCCA is getting worse with each generation, “and we think the cause might be environmental,” she said. “Studies show that there are almost zero percent carcinogens in hair care products that target Whites. But close to 100% of hair care products that target Blacks contain carcinogens and endocrine disrupting chemicals, the most common being phthalates, which are found in relaxers, chemicals that patients use to straighten their hair.”

Urinary phthalate concentrations have been found to be much higher in Black women than in White women, and one of the pilot studies she is involved with is checking the urinary phthalate levels in Black women with and without CCCA, to see if there is a correlation.

Mentorships

DiAnne S. Davis, MD, of North Dallas Dermatology Associates, rounded out the panel discussion by underscoring the importance of mentorships for underrepresented minority medical students, which includes providing guidance through the application process. “Mentorship is key to closing some of these gaps, particularly in our field of dermatology,” Dr. Davis said.

Through NMA Derm, Dr. Davis was tasked by one of her mentors, Dr. Kindred, to spearhead a mentorship program that pairs medical students with a mentor in the dermatology field, “so we can help guide them not only on their medical school process but help in coordinating research projects, and make them successful in matching to dermatology,” she said. “When students reach out to you, it’s important to take them under your wing or connect them to somebody you know so that we can increase the number of minority dermatologists.”

None of the panelists reported having disclosures relevant to their presentations.

– so he launched community outreach efforts with local businesses to attract patients from diverse backgrounds.

“For instance, I worked with U.S. Bank to give lectures on minorities in medicine and talked about outreach options and possible ways to include more ethnicities in medicine overall,” Dr. Qutub said during a panel discussion on equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) that took place at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “I also did outreach with medical clinics in the area. Once patients are referred to you, they start to talk to people in their communities about you, and before you know it, you get people from their church and family members in your clinic.”

Dr. Qutub, who is ODAC’s director of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, kept EDI in mind when hiring staff for his practice, “to include candidates with varying experiences and backgrounds,” he said. “The idea was to make sure that when patients came into the clinic, they saw a varied group of individuals that were working together to help improve their health care outcomes. I found that made patients more comfortable in the clinic. It’s also important to have that representation daily in a larger setting like residency programs or multispecialty groups.”

Educational resources

Another panelist, Adam Friedman, MD, emphasized inclusivity of educational resources to ensure a dermatology workforce that can take care of all patients. “How can we expect the dermatology community to be able to treat anyone who comes through the door of their clinic if we don’t provide the resources that highlight and showcase the nuances and the diversity that skin disease has to offer?” asked Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “It comes down to educational tools and being purposeful when you’re putting together a talk or writing a paper, to be inclusive and have that on the top of your mind. It’s about saying right here, right now, we have to purposefully make a decision to be inclusive, to be welcoming to all so that we can practice at the highest level of our calling to treat everyone effectively and equitably.”

A unique feature of the atlas “is that we have taken multiple skin conditions, even common features such as erythema, and placed different skin tones side by side at the same angle to appreciate the full spectrum, and highlight those nuances,” Dr. Friedman said. “When you’re in clinic, when you see even common things like acne or seborrheic dermatitis,” he recommended taking photos to create a repository, “because you never know when that will be helpful when you want to show a medical student or a patient what something can look like on someone with a similar skin tone, or even to share with them how diverse skin conditions can appear across populations.”

Clinical research

Another way to help close racial gaps in dermatology is to improve access to mentorships and clinical research, according to panelist Chesahna Kindred, MD, of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md. “We should be thoroughly embarrassed by the lack of diversity in our clinical trials,” she said.

In her role as chair of the dermatology section of the National Medical Association (NMA Derm), Dr. Kindred helped launch the NMA Derm research committee, which trains members to run clinical trials in their practices – an undertaking that was largely prompted by claims from pharmaceutical industry representatives that they struggle to find Black participants for clinical trials. “The truth of the matter is, if a Black patient doesn’t choose to go to Dr. Smith as a patient, they’re certainly not going to choose to go to Dr. Smith as a research participant,” Dr. Kindred said. “We have to meet those diverse populations where they are. By and large for Black patients, those are Black dermatologists.

In addition to meeting with primary investigators, she has been meeting with industry representatives, who she said are very interested in improving clinical trial diversity. “When a trial does not include a diverse population, we can call it out and say it is subpar,” she said.

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration announced the availability of a guidance document, “Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations – Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs,” which includes recommendations for sponsors on how to increase enrollment of underrepresented populations in their clinical trials of medical products.

Dr. Kindred has created a clinical research unit in her own practice, in partnership with Howard University’s department of dermatology and NMA Dermatology.

Studies Dr. Kindred is involved with include those looking at the relationship between hair care products targeted to Black women and the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA). CCCA is getting worse with each generation, “and we think the cause might be environmental,” she said. “Studies show that there are almost zero percent carcinogens in hair care products that target Whites. But close to 100% of hair care products that target Blacks contain carcinogens and endocrine disrupting chemicals, the most common being phthalates, which are found in relaxers, chemicals that patients use to straighten their hair.”

Urinary phthalate concentrations have been found to be much higher in Black women than in White women, and one of the pilot studies she is involved with is checking the urinary phthalate levels in Black women with and without CCCA, to see if there is a correlation.

Mentorships

DiAnne S. Davis, MD, of North Dallas Dermatology Associates, rounded out the panel discussion by underscoring the importance of mentorships for underrepresented minority medical students, which includes providing guidance through the application process. “Mentorship is key to closing some of these gaps, particularly in our field of dermatology,” Dr. Davis said.

Through NMA Derm, Dr. Davis was tasked by one of her mentors, Dr. Kindred, to spearhead a mentorship program that pairs medical students with a mentor in the dermatology field, “so we can help guide them not only on their medical school process but help in coordinating research projects, and make them successful in matching to dermatology,” she said. “When students reach out to you, it’s important to take them under your wing or connect them to somebody you know so that we can increase the number of minority dermatologists.”

None of the panelists reported having disclosures relevant to their presentations.

– so he launched community outreach efforts with local businesses to attract patients from diverse backgrounds.

“For instance, I worked with U.S. Bank to give lectures on minorities in medicine and talked about outreach options and possible ways to include more ethnicities in medicine overall,” Dr. Qutub said during a panel discussion on equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) that took place at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “I also did outreach with medical clinics in the area. Once patients are referred to you, they start to talk to people in their communities about you, and before you know it, you get people from their church and family members in your clinic.”

Dr. Qutub, who is ODAC’s director of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, kept EDI in mind when hiring staff for his practice, “to include candidates with varying experiences and backgrounds,” he said. “The idea was to make sure that when patients came into the clinic, they saw a varied group of individuals that were working together to help improve their health care outcomes. I found that made patients more comfortable in the clinic. It’s also important to have that representation daily in a larger setting like residency programs or multispecialty groups.”

Educational resources

Another panelist, Adam Friedman, MD, emphasized inclusivity of educational resources to ensure a dermatology workforce that can take care of all patients. “How can we expect the dermatology community to be able to treat anyone who comes through the door of their clinic if we don’t provide the resources that highlight and showcase the nuances and the diversity that skin disease has to offer?” asked Dr. Friedman, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “It comes down to educational tools and being purposeful when you’re putting together a talk or writing a paper, to be inclusive and have that on the top of your mind. It’s about saying right here, right now, we have to purposefully make a decision to be inclusive, to be welcoming to all so that we can practice at the highest level of our calling to treat everyone effectively and equitably.”

A unique feature of the atlas “is that we have taken multiple skin conditions, even common features such as erythema, and placed different skin tones side by side at the same angle to appreciate the full spectrum, and highlight those nuances,” Dr. Friedman said. “When you’re in clinic, when you see even common things like acne or seborrheic dermatitis,” he recommended taking photos to create a repository, “because you never know when that will be helpful when you want to show a medical student or a patient what something can look like on someone with a similar skin tone, or even to share with them how diverse skin conditions can appear across populations.”

Clinical research

Another way to help close racial gaps in dermatology is to improve access to mentorships and clinical research, according to panelist Chesahna Kindred, MD, of Kindred Hair & Skin Center in Columbia, Md. “We should be thoroughly embarrassed by the lack of diversity in our clinical trials,” she said.

In her role as chair of the dermatology section of the National Medical Association (NMA Derm), Dr. Kindred helped launch the NMA Derm research committee, which trains members to run clinical trials in their practices – an undertaking that was largely prompted by claims from pharmaceutical industry representatives that they struggle to find Black participants for clinical trials. “The truth of the matter is, if a Black patient doesn’t choose to go to Dr. Smith as a patient, they’re certainly not going to choose to go to Dr. Smith as a research participant,” Dr. Kindred said. “We have to meet those diverse populations where they are. By and large for Black patients, those are Black dermatologists.

In addition to meeting with primary investigators, she has been meeting with industry representatives, who she said are very interested in improving clinical trial diversity. “When a trial does not include a diverse population, we can call it out and say it is subpar,” she said.

In 2020, the Food and Drug Administration announced the availability of a guidance document, “Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations – Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs,” which includes recommendations for sponsors on how to increase enrollment of underrepresented populations in their clinical trials of medical products.

Dr. Kindred has created a clinical research unit in her own practice, in partnership with Howard University’s department of dermatology and NMA Dermatology.

Studies Dr. Kindred is involved with include those looking at the relationship between hair care products targeted to Black women and the development of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA). CCCA is getting worse with each generation, “and we think the cause might be environmental,” she said. “Studies show that there are almost zero percent carcinogens in hair care products that target Whites. But close to 100% of hair care products that target Blacks contain carcinogens and endocrine disrupting chemicals, the most common being phthalates, which are found in relaxers, chemicals that patients use to straighten their hair.”

Urinary phthalate concentrations have been found to be much higher in Black women than in White women, and one of the pilot studies she is involved with is checking the urinary phthalate levels in Black women with and without CCCA, to see if there is a correlation.

Mentorships

DiAnne S. Davis, MD, of North Dallas Dermatology Associates, rounded out the panel discussion by underscoring the importance of mentorships for underrepresented minority medical students, which includes providing guidance through the application process. “Mentorship is key to closing some of these gaps, particularly in our field of dermatology,” Dr. Davis said.

Through NMA Derm, Dr. Davis was tasked by one of her mentors, Dr. Kindred, to spearhead a mentorship program that pairs medical students with a mentor in the dermatology field, “so we can help guide them not only on their medical school process but help in coordinating research projects, and make them successful in matching to dermatology,” she said. “When students reach out to you, it’s important to take them under your wing or connect them to somebody you know so that we can increase the number of minority dermatologists.”

None of the panelists reported having disclosures relevant to their presentations.

FROM ODAC 2022

Referrals to gender clinics in Sweden drop after media coverage

Media coverage of transgender health care judged to be “negative” was associated with a drop of around 30% in referral rates to gender identity clinics in Sweden among young people under age 19, a new study indicates.

Malin Indremo, MS, from the department of neuroscience, Uppsala (Sweden) University, and colleagues explored the effect of the documentaries, “The Trans Train and Teenage Girls,” which they explain was a “Swedish public service television show” representing “investigative journalism.” The two-part documentary series was aired in Sweden in April 2019 and October 2019, respectively, and is now available in English on YouTube.

In their article, published online in JAMA Network Open, the authors said they consider “The Trans Train” programs to be “negative” media coverage because the “documentaries addressed the distinct increase among adolescents referred to gender identity clinics in recent years. Two young adults who regretted their transition and parents of transgender individuals who questioned the clinics’ assessments of their children were interviewed, and concerns were raised about whether gender-confirming treatments are based on sufficient scientific evidence.”

The programs, they suggest, may have influenced and jeopardized young transgender individuals’ access to transgender-specific health care.

Stella O’Malley, a U.K.-based psychotherapist specializing in transgender care and executive director of Genspect, an international organization that provides support to the parents of young people who are questioning their gender, expressed her disappointment with the study’s conclusions.

“I’m really surprised and disappointed that the researchers believe that negative coverage is the reason for a drop in referrals when it is more accurate to say that the information provided by ‘The Trans Train’ documentaries was concerning and suggests that further critical analysis and a review needs to be carried out on the clinics in question,” she said in an interview.

Ms. O’Malley herself made a documentary for Channel 4 in the United Kingdom, broadcast in 2018, called: “Trans Kids: It’s Time to Talk.”

Rapidly increasing numbers of youth, especially girls, question gender

As Ms. Indremo and coauthors explained – and as has been widely reported by this news organization – “the number of referrals to gender identity clinics have rapidly increased worldwide” in recent years, and this “has been especially prominent in adolescents and young adults.”

In addition, they acknowledged, “there has been a shift in gender ratio, with a preponderance toward individuals who were assigned female at birth (AFAB).”

This was the topic of “The Trans Train” programs, and in fact, following their broadcast, Ms. Indremo and colleagues noted that “an intense debate in national media [in Sweden] arose from the documentaries.”

Their research aimed to explore the association between both “positive” and “negative” media coverage and the number of referrals to gender identity clinics for young people (under aged 19) respectively. Data from the six gender clinics in Sweden were included between January 2017 and December 2019.

In the period studied, the clinics received 1,784 referrals, including 613 referrals in 2017, 663 referrals in 2018, and 508 referrals in 2019.

From the age-specific data that included 1,674 referrals, 359 individuals (21.4%) were younger than 13 years and 1,315 individuals (78.6%) were aged 13-18 years. From the assigned sex-specific data that included 1,435 referrals, 1,034 individuals (72.1%) were AFAB and 401 individuals (27.9%) were assigned male at birth (AMAB). Information on sex assigned at birth was lacking from one clinic, which was excluded from the analysis.

When they examined data for the 3 months following the airing of the first part of “The Trans Train” documentary series (in April 2019), they found that referrals to gender clinics fell by 25.4% overall, compared with the 3 months before part 1 was screened. Specifically, they fell by 25.3% for young people aged 13-18 years and by 32.2% for those born female.

In the extended analyses of 6 months following part 1, a decrease of total referrals by 30.7% was observed, while referrals for AFAB individuals decreased by 37.4% and referrals for individuals aged 13-18 years decreased by 27.7%. A decrease of referrals by 41.7% for children aged younger than 13 years was observed in the 6-month analysis, as well as a decrease of 8.2% among AMAB individuals.

“The Trans Train” documentaries, Ms. Indremo and colleagues said, “were criticized for being negatively biased and giving an oversimplified picture of transgender health care.”

Did the nature of the trans train documentaries influence referrals?

In an invited commentary published in JAMA Network Open, Ken C. Pang, PhD, from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, and colleagues noted: “Although the mechanisms underlying this decrease [in referrals] were not formally explored in their study, the authors reasonably speculated that both parents and referring health professionals may have been less likely to support a child or adolescent’s attendance at a specialist pediatric gender clinic following the documentaries.”

Dr. Pang and colleagues went on to say it is “the ... responsibility of media organizations in ensuring that stories depicting health care for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) young people are fair, balanced, nuanced, and accurate.”

Often, media reports have “fallen short of these standards and lacked the voices of TGD young people who have benefited from gender-affirming care or the perspectives of health professionals with expertise in providing such care,” they added.

“For example, some [media reports] have suggested that the growing number of referrals to such clinics is not owing to greater awareness of gender diversity and empowerment of TGD young people but is instead being driven by other factors such as peer influence, while others have warned that the use of gender-affirming hormonal interventions in TGD young people represents an undue risk,” they continue.

Ms. Indremo and colleagues didn’t see any drop-in referrals after the second part of the series, aired in October 2019, but they say this was likely because referrals were “already lowered” by the airing of the first part of the documentaries.

Nor did they see an increase in referrals following what they say was a “positive” media event in the form of a story about a professional Swedish handball player who announced the decision to quit his career to seek care for gender dysphoria.

“One may assume that a single news event is not significant enough to influence referral counts,” they suggested, noting also that Sweden represents “a society where there is already a relatively high level of awareness of gender identity issues.”

“Our results point to a differential association of media attention depending on the tone of the media content,” they observed.

Dr. Pang and coauthors noted it would be “helpful to examine whether similar media coverage in other countries has been associated with similar decreases in referral numbers and whether particular types of media stories are more prone to having this association.”

Parents and doctors debate treatment of gender dysphoria

In Sweden, custodians’ permission as well as custodians’ help is needed for minors to access care for gender dysphoria, said Ms. Indremo and coauthors. “It is possible that the content of the documentaries contributed to a higher custodian barrier to having their children referred for assessment, believing it may not be in the best interest of their child. This would highly impact young transgender individuals’ possibilities to access care.”

They also acknowledge that health care practitioners who refer young people to specialist clinics might also have been influenced by the documentaries, noting “some commentators argued that all treatments for gender dysphoria be stopped, and that ‘all health care given at the gender identity clinics was an experiment lacking scientific basis.’ ”

In April 2021, Angela Sämfjord, MD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden, who started a child and adolescent clinic – the Lundstrom Gender Clinic – told this news organization she had reevaluated her approach even prior to “The Trans Train” documentaries and had resigned in 2018 because of her own fears about the lack of evidence for hormonal and surgical treatments of youth with gender dysphoria.

Following the debate that ensued after the airing of “The Trans Train” programs, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare published new recommendations in March 2021, which reflected a significant change in direction for the evaluation of gender dysphoria in minors, emphasizing the requirement for a thorough mental health assessment.

And in May 2021, Karolinska Children’s Hospital, which houses one of the leading gender identity clinics in Sweden, announced it would stop the routine medical treatment of children with gender dysphoria under the age of 18, which meant a total ban on the prescribing of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to minors. Such treatment could henceforth only be carried out within the setting of a clinical trial approved by the EPM (Ethical Review Agency/Swedish Institutional Review Board), it said.

The remaining five gender identity clinics in Sweden decided upon their own rules, but in general, they have become much more cautious regarding medical treatment of minors within the past year. Also, there is a desire in Sweden to reduce the number of gender identity clinics for minors from the current six to perhaps a maximum of three nationwide.

However, neither Ms. Indremo and colleagues nor Dr. Pang and colleagues mentioned the subsequent change to the Swedish NBHW recommendations on evaluation of gender dysphoria in minors in JAMA articles.

New NBHW recommendations about medical treatment of gender dysphoria with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for minors were due to be issued in 2021 but have been delayed.

Debate in other countries

Sweden is not alone in discussing this issue. In 2020, Finland became the first country in the world to issue new guidelines that concluded there is a lack of quality evidence to support the use of hormonal interventions in adolescents with gender dysphoria.

This issue has been hotly debated in the United Kingdom – not least with the Keira Bell court case and two National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence evidence reviews concluding there is a lack of data to support the use of puberty-blocking agents and “cross-sex” hormones in youth with gender dysphoria.

And a number of U.S. states are attempting to outlaw the medical and surgical treatment of gender dysphoria in minors. Even health care professionals who have been treating young people with gender dysphoria for years – some of whom are transgender themselves – have started to speak out and are questioning what they call “sloppy care” given to many such youth.

Indeed, a recent survey shows that detransitioners – individuals who suffer from gender dysphoria, transition to the opposite sex but then regret their decision and detransition – are getting short shrift when it comes to care, with over half of the 100 surveyed saying they feel they did not receive adequate evaluation from a doctor or mental health professional before starting to transition.

And new draft standards of care for treating people with gender dysphoria by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health have drawn criticism from experts.

‘First do no harm’

In their conclusion, Dr. Pang and coauthors said that, with respect to the media coverage of young people with gender dysphoria, “who are, after all, one of the most vulnerable subgroups within our society, perhaps our media should recall one of the core tenets of health care and ensure their stories ‘first, do no harm.’”

However, in a commentary recently published in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Alison Clayton, MBBS, from the University of Melbourne, and coauthors again pointed out that evidence reviews of the use of puberty blockers in young people with gender dysphoria show “there is very low certainty of the benefits of puberty blockers, an unknown risk of harm, and there is need for more rigorous research.”

“The clinically prudent thing to do, if we aim to ‘first, do no harm,’ is to proceed with extreme caution, especially given the rapidly rising case numbers and novel gender dysphoria presentations,” Clayton and colleagues concluded.

Ms. Indremo and coauthors reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pang reported being a member of the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health and its research committee. One commentary coauthor has reported being a member of WPATH.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Media coverage of transgender health care judged to be “negative” was associated with a drop of around 30% in referral rates to gender identity clinics in Sweden among young people under age 19, a new study indicates.

Malin Indremo, MS, from the department of neuroscience, Uppsala (Sweden) University, and colleagues explored the effect of the documentaries, “The Trans Train and Teenage Girls,” which they explain was a “Swedish public service television show” representing “investigative journalism.” The two-part documentary series was aired in Sweden in April 2019 and October 2019, respectively, and is now available in English on YouTube.

In their article, published online in JAMA Network Open, the authors said they consider “The Trans Train” programs to be “negative” media coverage because the “documentaries addressed the distinct increase among adolescents referred to gender identity clinics in recent years. Two young adults who regretted their transition and parents of transgender individuals who questioned the clinics’ assessments of their children were interviewed, and concerns were raised about whether gender-confirming treatments are based on sufficient scientific evidence.”

The programs, they suggest, may have influenced and jeopardized young transgender individuals’ access to transgender-specific health care.

Stella O’Malley, a U.K.-based psychotherapist specializing in transgender care and executive director of Genspect, an international organization that provides support to the parents of young people who are questioning their gender, expressed her disappointment with the study’s conclusions.

“I’m really surprised and disappointed that the researchers believe that negative coverage is the reason for a drop in referrals when it is more accurate to say that the information provided by ‘The Trans Train’ documentaries was concerning and suggests that further critical analysis and a review needs to be carried out on the clinics in question,” she said in an interview.

Ms. O’Malley herself made a documentary for Channel 4 in the United Kingdom, broadcast in 2018, called: “Trans Kids: It’s Time to Talk.”

Rapidly increasing numbers of youth, especially girls, question gender

As Ms. Indremo and coauthors explained – and as has been widely reported by this news organization – “the number of referrals to gender identity clinics have rapidly increased worldwide” in recent years, and this “has been especially prominent in adolescents and young adults.”

In addition, they acknowledged, “there has been a shift in gender ratio, with a preponderance toward individuals who were assigned female at birth (AFAB).”

This was the topic of “The Trans Train” programs, and in fact, following their broadcast, Ms. Indremo and colleagues noted that “an intense debate in national media [in Sweden] arose from the documentaries.”

Their research aimed to explore the association between both “positive” and “negative” media coverage and the number of referrals to gender identity clinics for young people (under aged 19) respectively. Data from the six gender clinics in Sweden were included between January 2017 and December 2019.

In the period studied, the clinics received 1,784 referrals, including 613 referrals in 2017, 663 referrals in 2018, and 508 referrals in 2019.

From the age-specific data that included 1,674 referrals, 359 individuals (21.4%) were younger than 13 years and 1,315 individuals (78.6%) were aged 13-18 years. From the assigned sex-specific data that included 1,435 referrals, 1,034 individuals (72.1%) were AFAB and 401 individuals (27.9%) were assigned male at birth (AMAB). Information on sex assigned at birth was lacking from one clinic, which was excluded from the analysis.

When they examined data for the 3 months following the airing of the first part of “The Trans Train” documentary series (in April 2019), they found that referrals to gender clinics fell by 25.4% overall, compared with the 3 months before part 1 was screened. Specifically, they fell by 25.3% for young people aged 13-18 years and by 32.2% for those born female.

In the extended analyses of 6 months following part 1, a decrease of total referrals by 30.7% was observed, while referrals for AFAB individuals decreased by 37.4% and referrals for individuals aged 13-18 years decreased by 27.7%. A decrease of referrals by 41.7% for children aged younger than 13 years was observed in the 6-month analysis, as well as a decrease of 8.2% among AMAB individuals.

“The Trans Train” documentaries, Ms. Indremo and colleagues said, “were criticized for being negatively biased and giving an oversimplified picture of transgender health care.”

Did the nature of the trans train documentaries influence referrals?

In an invited commentary published in JAMA Network Open, Ken C. Pang, PhD, from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, and colleagues noted: “Although the mechanisms underlying this decrease [in referrals] were not formally explored in their study, the authors reasonably speculated that both parents and referring health professionals may have been less likely to support a child or adolescent’s attendance at a specialist pediatric gender clinic following the documentaries.”

Dr. Pang and colleagues went on to say it is “the ... responsibility of media organizations in ensuring that stories depicting health care for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) young people are fair, balanced, nuanced, and accurate.”

Often, media reports have “fallen short of these standards and lacked the voices of TGD young people who have benefited from gender-affirming care or the perspectives of health professionals with expertise in providing such care,” they added.

“For example, some [media reports] have suggested that the growing number of referrals to such clinics is not owing to greater awareness of gender diversity and empowerment of TGD young people but is instead being driven by other factors such as peer influence, while others have warned that the use of gender-affirming hormonal interventions in TGD young people represents an undue risk,” they continue.

Ms. Indremo and colleagues didn’t see any drop-in referrals after the second part of the series, aired in October 2019, but they say this was likely because referrals were “already lowered” by the airing of the first part of the documentaries.

Nor did they see an increase in referrals following what they say was a “positive” media event in the form of a story about a professional Swedish handball player who announced the decision to quit his career to seek care for gender dysphoria.

“One may assume that a single news event is not significant enough to influence referral counts,” they suggested, noting also that Sweden represents “a society where there is already a relatively high level of awareness of gender identity issues.”

“Our results point to a differential association of media attention depending on the tone of the media content,” they observed.

Dr. Pang and coauthors noted it would be “helpful to examine whether similar media coverage in other countries has been associated with similar decreases in referral numbers and whether particular types of media stories are more prone to having this association.”

Parents and doctors debate treatment of gender dysphoria

In Sweden, custodians’ permission as well as custodians’ help is needed for minors to access care for gender dysphoria, said Ms. Indremo and coauthors. “It is possible that the content of the documentaries contributed to a higher custodian barrier to having their children referred for assessment, believing it may not be in the best interest of their child. This would highly impact young transgender individuals’ possibilities to access care.”

They also acknowledge that health care practitioners who refer young people to specialist clinics might also have been influenced by the documentaries, noting “some commentators argued that all treatments for gender dysphoria be stopped, and that ‘all health care given at the gender identity clinics was an experiment lacking scientific basis.’ ”