User login

Discoid Lupus

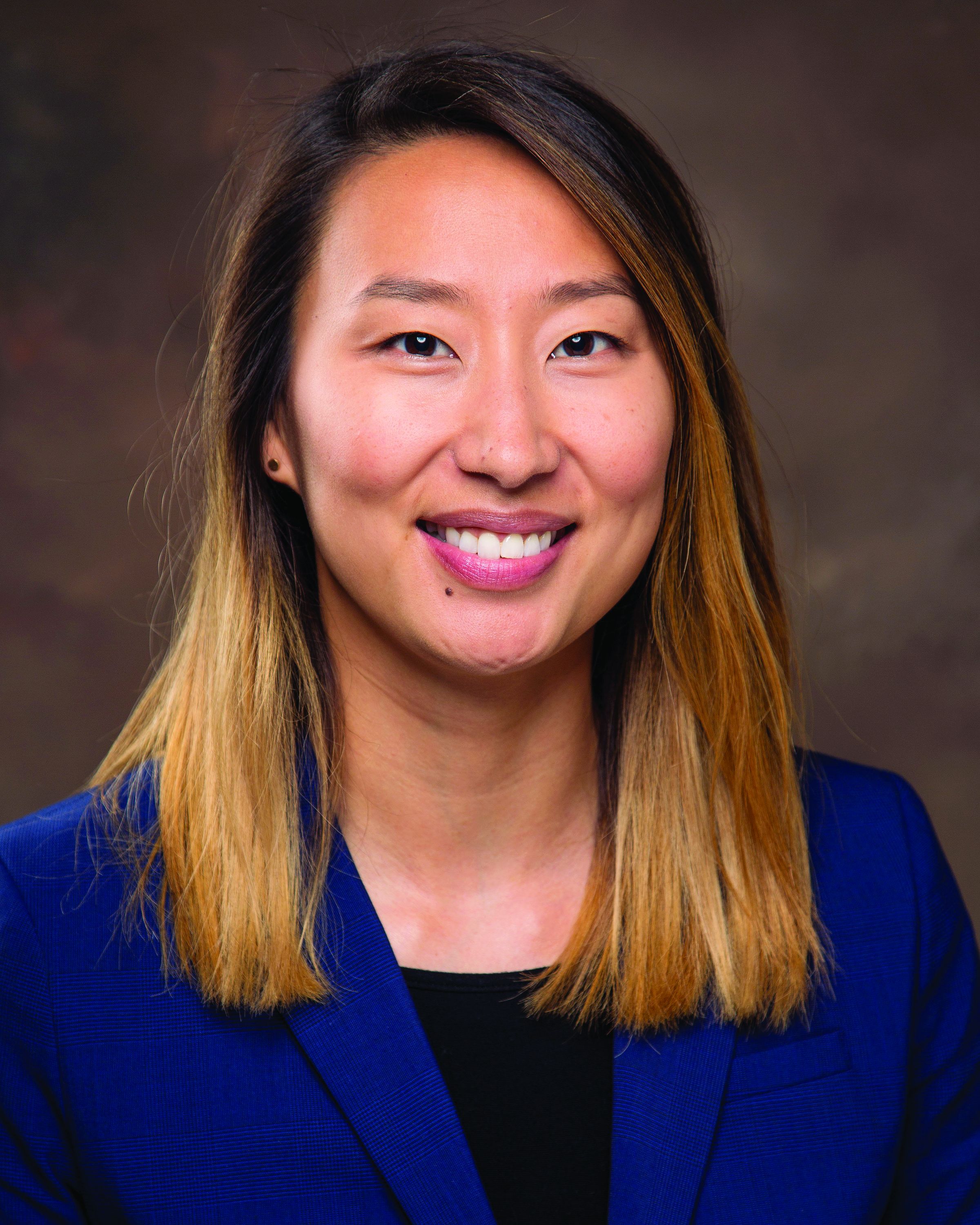

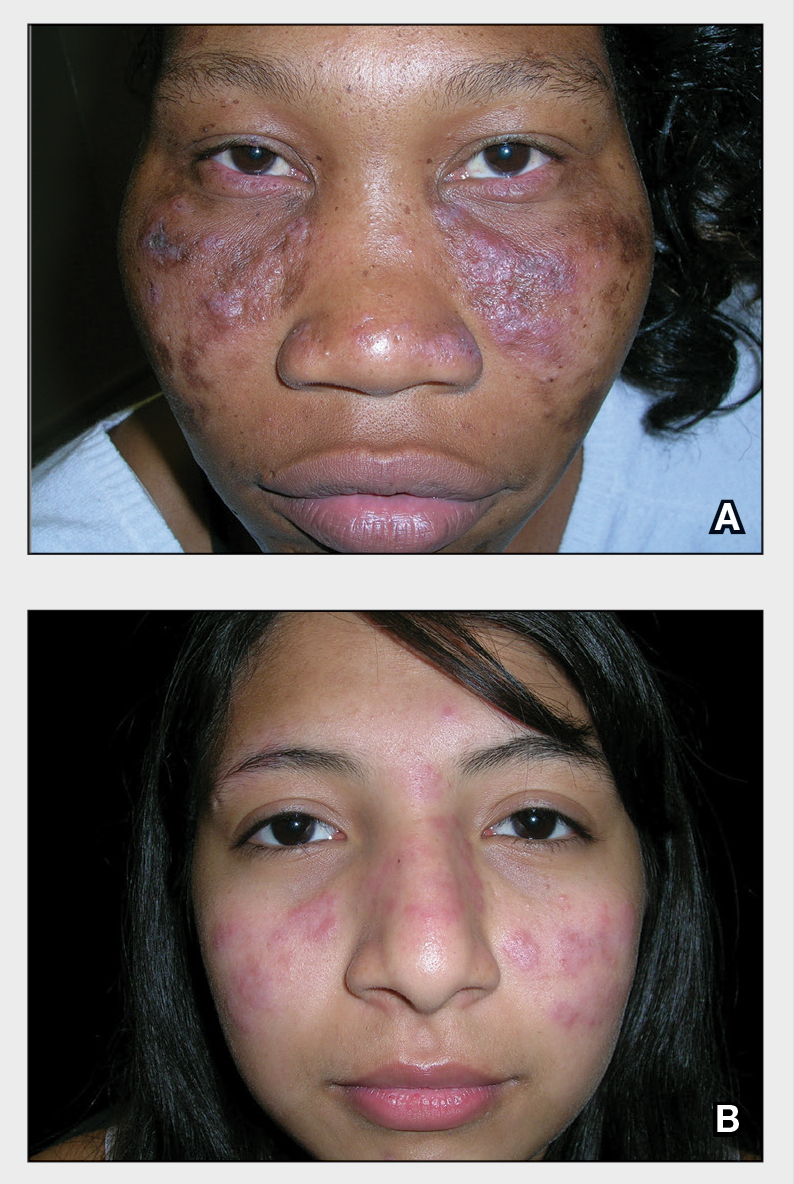

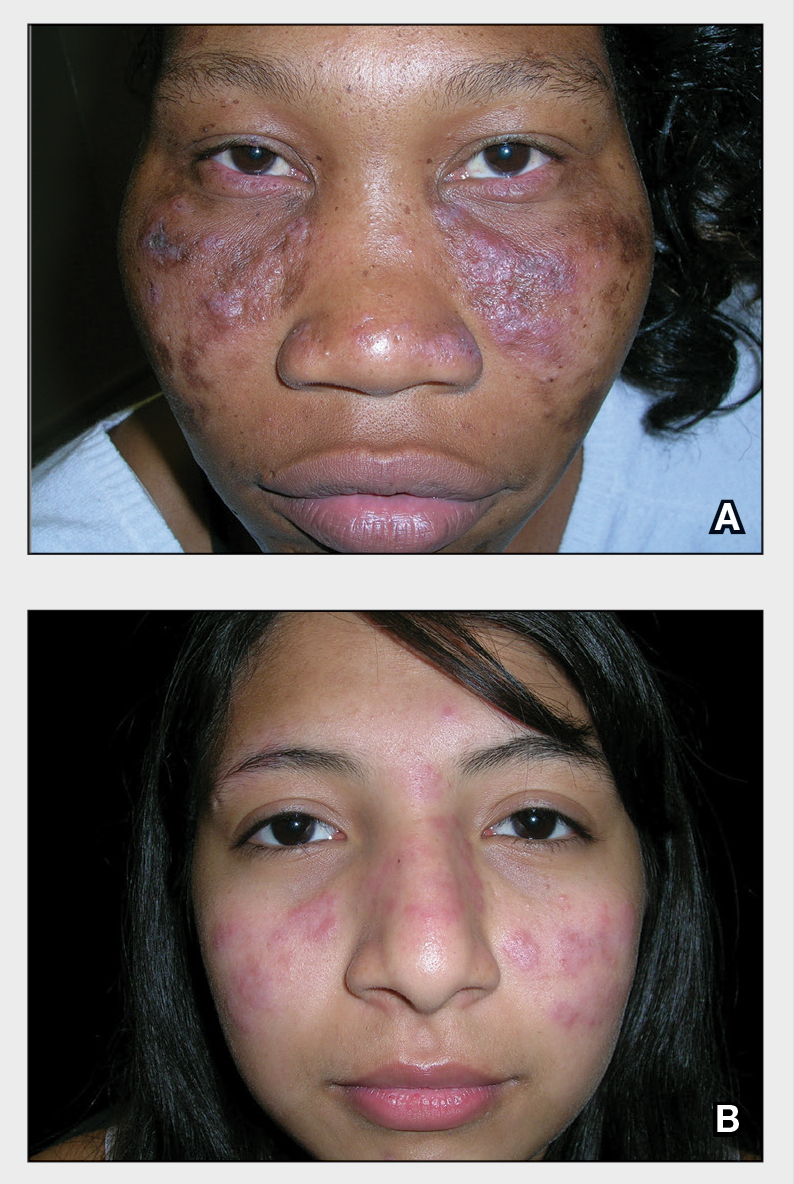

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

THE COMPARISON

A Multicolored (pink, brown, and white) indurated plaques in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 30-year-old woman with a darker skin tone.

B Pink, elevated, indurated plaques with hypopigmentation in a butterfly distribution on the face of a 19-year-old woman with a lighter skin tone.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus may occur with or without systemic lupus erythematosus. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a form of chronic cutaneous lupus, is most commonly found on the scalp, face, and ears.1

Epidemiology

Discoid lupus erythematosus is most common in adult women (age range, 20–40 years).2 It occurs more frequently in women of African descent.3,4

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones:

Clinical features of DLE lesions include erythema, induration, follicular plugging, dyspigmentation, and scarring alopecia.1 In patients of African descent, lesions may be annular and hypopigmented to depigmented centrally with a border of hyperpigmentation. Active lesions may be painful and/or pruritic.2

Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions occur in photodistributed areas, although not exclusively. Photoprotective clothing and sunscreen are an important part of the treatment plan.1 Although sunscreen is recommended for patients with DLE, those with darker skin tones may find some sunscreens cosmetically unappealing due to a mismatch with their normal skin color.5 Tinted sunscreens may be beneficial additions.

Worth noting

Approximately 5% to 25% of patients with cutaneous lupus go on to develop systemic lupus erythematosus.6

Health disparity highlight

Discoid lesions may cause cutaneous scars that are quite disfiguring and may negatively impact quality of life. Some patients may have a few scattered lesions, whereas others have extensive disease covering most of the scalp. Discoid lupus erythematosus lesions of the scalp have classic clinical features including hair loss, erythema, hypopigmentation, and hyperpigmentation. The clinician’s comfort with performing a scalp examination with cultural humility is an important acquired skill and is especially important when the examination is performed on patients with more tightly coiled hair.7 For example, physicians may adopt the “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method when counseling patients.8

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Otberg N, Wu W-Y, McElwee KJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19-26. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x

- Callen JP. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. clinical, laboratory, therapeutic, and prognostic examination of 62 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:412-416. doi:10.1001/archderm.118.6.412

- McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA Jr, et al. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1260-1270. doi:10.1002/art.1780380914

- Morquette AJ, Waples ER, Heath CR. The importance of cosmetically elegant sunscreen in skin of color populations. J Cosmet Dermatol. In press.

- Zhou W, Wu H, Zhao M, et al. New insights into the progression from cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16:829-837. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2020.1805316

- Grayson C, Heath C. An approach to examining tightly coiled hair among patients with hair loss in race-discordant patientphysician interactions. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:505-506. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0338

- Grayson C, Heath CR. Counseling about traction alopecia: a “compliment, discuss, and suggest” method. Cutis. 2021;108:20-22.

Columbia names interim chair of psychiatry after Twitter controversy

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, will take over for Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, who was suspended over a tweet he sent that was widely condemned as both racist and sexist.

She will also serve as interim director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and interim psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, the email stated.

All appointments were effective on Feb. 28.

Latest response

Dr. Simpson, who joined the faculty at Columbia in 1999, previously served as a professor and vice chair of research for the psychiatry department, director of Columbia’s Center for Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, and director of psychiatry research at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Simpson is associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and is president-elect of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America.

Her research has been continuously funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1999, and she has advised both the World Health Organization and the American Psychiatric Association on the diagnosis and treatment of OCD.

Dr. Simpson has a bachelor’s degree in biology from Yale University and completed an MD-PhD program at The Rockefeller University and Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. She did her residency in psychiatry at New York–Presbyterian.

The announcement is Columbia’s latest response to the furor that erupted on social media following Dr. Lieberman’s tweet about Sudanese model Nyakim Gatwech, in which he wrote, “Whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

Twitter reacted immediately and negatively to the tweet, which even Dr. Lieberman later acknowledged was “racist and sexist” in an email apology he sent Feb. 22 to faculty and staff in the department of psychiatry.

As reported by this news organization, Columbia suspended Dr. Lieberman from his chair position on Feb. 23 and permanently removed him from the post of psychiatrist-in-chief at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Lieberman also resigned as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

The email announcing Simpson’s appointment was signed by Katrina Armstrong, MD, incoming CEO, Columbia University Irving Medical Center and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons; Anil K. Rustgi, MD, interim executive vice president and dean of the Faculties of Health Sciences and Medicine; Steven J. Corwin, MD; president and CEO, New York–Presbyterian; and Ann Marie Sullivan, MD, commissioner of the New York State Office of Mental Health.

This is a developing story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health disparities exist all over rheumatology: What can be done?

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?

Eric Ruderman, MD, professor of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, commented that institutions have been forming committees and focus groups, but “not a lot of action.”

“They’re checking boxes,” he said, “which is very frustrating.” What can rheumatologists do in the short term, he asked?

Dr. Wells noted that there has been some success in using a “carrot” model of using payment models to reduce racial disparities. For example, a recent study analyzing the effects of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model highlighted the need for payment reform that incentivizes clinicians to spend wisely on patient treatment. Under a payment model that rewards clinicians for treating patients cost effectively, “if I do a great job cost effectively, I could just have more of that money back to my group,” he said.

George Martin, MD, a clinical dermatologist practicing in Maui, recalled the disparity in health care he observed as a child growing up in Philadelphia. “There’s really, within the city, there’s two different levels of health care,” he said. “There’s a tremendous disparity in the quality of the physician in hospital, and way out in the community. Because that’s the point of contact. That’s when either you’re going to prescribe a biologic, or [you’re] going to give them some aspirin and tell them go home. That’s where it starts, point of contact.”

Dr. Wells agreed that it is a big challenge, noting that cities also contribute to pollution, crowding, and other factors that adversely impact health care.

“It’s a shared responsibility. How do we solve that?” Dr. Martin asked. “And if you tell me, I’m going to give you a Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Wells reported he is a reviewer for the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?

Eric Ruderman, MD, professor of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, commented that institutions have been forming committees and focus groups, but “not a lot of action.”

“They’re checking boxes,” he said, “which is very frustrating.” What can rheumatologists do in the short term, he asked?

Dr. Wells noted that there has been some success in using a “carrot” model of using payment models to reduce racial disparities. For example, a recent study analyzing the effects of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model highlighted the need for payment reform that incentivizes clinicians to spend wisely on patient treatment. Under a payment model that rewards clinicians for treating patients cost effectively, “if I do a great job cost effectively, I could just have more of that money back to my group,” he said.

George Martin, MD, a clinical dermatologist practicing in Maui, recalled the disparity in health care he observed as a child growing up in Philadelphia. “There’s really, within the city, there’s two different levels of health care,” he said. “There’s a tremendous disparity in the quality of the physician in hospital, and way out in the community. Because that’s the point of contact. That’s when either you’re going to prescribe a biologic, or [you’re] going to give them some aspirin and tell them go home. That’s where it starts, point of contact.”

Dr. Wells agreed that it is a big challenge, noting that cities also contribute to pollution, crowding, and other factors that adversely impact health care.

“It’s a shared responsibility. How do we solve that?” Dr. Martin asked. “And if you tell me, I’m going to give you a Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Wells reported he is a reviewer for the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

Disparities in health care exist in every specialty. In rheumatology, health disparities look like lack of access to care and lack of education on the part of rheumatologists and their patients, according to a speaker at the 2022 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Health disparities can affect people based on their racial or ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, a mental or physical disability, socioeconomic status, or religion, Alvin Wells, MD, PhD, director of the department of rheumatology at Advocate Aurora Health in Franklin, Wisc., said in his presentation. But a person’s environment also plays a role – “where you live, work, play, and worship.”

Social determinants of health can affect short-term and long-term health outcomes, functioning, and quality of life, he noted. “It’s economic stability, it’s access not only to health care, but also to education. And indeed, in my lifetime, as you know, some individuals weren’t allowed to read and write. They weren’t allowed to go to schools. You didn’t get the same type of education, and so that made a dramatic impact in moving forward with future, subsequent generations.”

In a survey of executives, clinical leaders, and clinicians in NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 48% said widespread disparities in care delivery were present in their organizations. According to the social psychologist James S. House, PhD, some of these disparities like race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, genetics, and geography are fixed, while others like psychosocial, medical care/insurance, and environmental hazards are modifiable. While factors like education, work, and location might be modifiable for some patients, others don’t have the ability to make these changes, Dr. Wells explained. “It’s not that easy when you think about it.”

Within rheumatology, racial and ethnic disparities exist in rheumatoid arthritis when it comes to disease activity and use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Disparities in outcomes based on race and geographic location have also been identified for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, and based on race in osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. “Where people live, where they reside, where their zip code is,” makes a difference for patients with rheumatic diseases, Dr. Wells said.

“We’ve heard at this meeting [about] some amazing drugs in treating our patients, both [for] skin and joint disease, but not everybody has the same kind of access,” he said.

What actions can medical stakeholders take?

Health equity should be a “desirable goal” for patients who experience health disparities, but it needs to be a “continuous effort,” Dr. Wells said. Focusing on the “how” of eliminating disparities should be a focus rather than checking a box.

Pharmacoequity is also a component of health equity, according to Dr. Wells. Where a person lives can affect their health based on their neighborhood’s level of air pollution, access to green space, and food deserts, but where a person lives also affects what parts of the health system they have access to, according to an editorial published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. When patients aren’t taking their medication, it might be because that person doesn’t have easy access to a pharmacy, noted Dr. Wells. “It really kind of blows you away when you look at the data.”

Different stakeholders in medicine can tackle various aspects of this problem. For example, health care organizations and medical schools can make long-term commitments to prioritizing health equality, Dr. Wells said. “You want to make this a part of your practice, your group, or your university. And then once you get a process in place, don’t just check that box and move on. You want to see it. If you haven’t reached your goal, you need to revamp. If you met your goal, how do [you] improve upon that?”

Medical schools can also do better at improving misconceptions about patients of different races and ethnicities. Dr. Wells cited a striking paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. that compared false beliefs in biological differences between Black and White people held by White laypeople and medical students. The study found that 58% of laypeople and 40% of first-year medical students believed that Black people have thicker skin than White people. “It’s absolutely amazing when you think about what medical schools can do,” he said.

Increased access to care is another area for improvement, Dr. Wells noted. “If you take people who are uninsured and you look at their health once they get Medicare, the gaps begin to close between the different races.”

In terms of individual actions, Dr. Wells noted that researchers and clinicians can help to make clinical trials better represent the overall population. At your practice, “treat all your patients like a VIP.” Instead of being concerned about the cost of a treatment, ask “is your patient worth it?”

“I have one of my patients on Medicaid. She’s on a biologic drug. And one of the VPs of my hospital is on the same drug. We don’t treat them any differently.”

The private sector is also acting, Dr. Wells said. He cited Novartis’ pledge to partner with 26 historically Black colleges to improve disparities in health and education. “We need to see more of that done from corporate America.”

Are there any short-term solutions?

Eric Ruderman, MD, professor of rheumatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, commented that institutions have been forming committees and focus groups, but “not a lot of action.”

“They’re checking boxes,” he said, “which is very frustrating.” What can rheumatologists do in the short term, he asked?

Dr. Wells noted that there has been some success in using a “carrot” model of using payment models to reduce racial disparities. For example, a recent study analyzing the effects of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement model highlighted the need for payment reform that incentivizes clinicians to spend wisely on patient treatment. Under a payment model that rewards clinicians for treating patients cost effectively, “if I do a great job cost effectively, I could just have more of that money back to my group,” he said.

George Martin, MD, a clinical dermatologist practicing in Maui, recalled the disparity in health care he observed as a child growing up in Philadelphia. “There’s really, within the city, there’s two different levels of health care,” he said. “There’s a tremendous disparity in the quality of the physician in hospital, and way out in the community. Because that’s the point of contact. That’s when either you’re going to prescribe a biologic, or [you’re] going to give them some aspirin and tell them go home. That’s where it starts, point of contact.”

Dr. Wells agreed that it is a big challenge, noting that cities also contribute to pollution, crowding, and other factors that adversely impact health care.

“It’s a shared responsibility. How do we solve that?” Dr. Martin asked. “And if you tell me, I’m going to give you a Nobel Prize.”

Dr. Wells reported he is a reviewer for the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Disparities.

FROM RWCS 2022

Epidural may lower odds of severe maternal birth complications

Use of neuraxial analgesia for vaginal delivery is associated with a 14% decreased risk for severe maternal morbidity, in part from a reduction in postpartum hemorrhage, new research shows.

The findings indicate that increasing the use of epidural or combined spinal-epidural analgesia may improve maternal health outcomes, especially for Hispanic, Black, and uninsured women who are less likely than White women to receive these interventions, according to the researchers, who published their findings online in JAMA Network Open.

About 80% of non-Hispanic White women receive neuraxial analgesia during labor in the United States, compared with 70% of non-Hispanic Black women and 65% of Hispanic women, according to birth certificate data. Among women without health insurance, half receive epidurals.

Programs that inform pregnant women about epidural use, expand Medicaid, and provide in-house obstetric anesthesia teams “may improve patient participation in clinical decision making and access to care,” study author Guohua Li, MD, DrPH, of Columbia University, New York, said in a statement about the research.

Earlier data from France showed that neuraxial analgesia is associated with reduced risk for severe postpartum hemorrhage. To examine the association between labor neuraxial analgesia and severe maternal morbidity in the United States, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed more than 575,000 vaginal deliveries in New York hospitals between 2010 and 2017; about half (47.4%) of the women received epidurals during labor.

The researchers focused on severe maternal morbidity, including 16 complications, such as heart failure and sepsis, and five procedures, including hysterectomy and ventilation.

They also considered patient characteristics and comorbidities and hospital-related factors to identify patients who were at higher risk for injury or death.

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 1.3% of the women. Of the 7,712 women with severe morbidity, more than one in three (35.6%) experienced postpartum hemorrhage.

The overall incidence of severe maternal morbidity was 1.3% among women who received an epidural injection and 1.4% among those who did not. In a weighted analysis, the adjusted odds ratio of severe maternal morbidity associated with epidurals was 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.82-0.90).

The study is limited by its observational design and does not prove causation, the authors acknowledged.

“Labor neuraxial analgesia may facilitate early evaluation and management of the third stage of labor to avoid escalation of postpartum hemorrhaging into grave complications and death,” study author Jean Guglielminotti, MD, PhD, an anesthesiologist at Columbia University, said in a statement.

Concerning trends

The Department of Health & Human Services has labeled severe maternal morbidity a public health priority. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show an increase in maternal mortality rates and worsening disparities by race and ethnicity.

According to the CDC, 861 women died of maternal causes in 2020, up from 754 in 2019. The rate of maternal mortality increased from 20.1 to 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births.

For Black women, however, the maternal mortality rate was far higher: 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births – nearly triple the figure of 19.1 per 100,000 for White women. Between 2019 and 2020, the mortality rate increased significantly for Black and Hispanic women, but not White mothers.

Researchers affiliated with University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children agreed in an accompanying editorial that more access to neuraxial labor analgesia for vaginal delivery might improve maternal health outcomes and “may be a strategy well worth pursuing in public health policy.”

The intervention is relatively safe and can “alleviate discomfort and distress,” they wrote.

Neuraxial anesthesia in surgical procedures has been shown to decrease the risk for complications like deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, transfusion requirements, and kidney failure, said editorialists Evelina Pankiv, MD; Alan Yang, MSc; and Kazuyoshi Aoyama, MD, PhD.

Benefits potentially could stem from improving blood flow, mitigating hypercoagulation, or reducing surgical stress response. But there are rare risks to consider as well, including hemorrhage, infection, and neurologic injury, they added.

Guglielminotti disclosed grants from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Aoyama reported receiving grants from the Perioperative Services Facilitator Grant Program and Hospital for Sick Children. The other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of neuraxial analgesia for vaginal delivery is associated with a 14% decreased risk for severe maternal morbidity, in part from a reduction in postpartum hemorrhage, new research shows.

The findings indicate that increasing the use of epidural or combined spinal-epidural analgesia may improve maternal health outcomes, especially for Hispanic, Black, and uninsured women who are less likely than White women to receive these interventions, according to the researchers, who published their findings online in JAMA Network Open.

About 80% of non-Hispanic White women receive neuraxial analgesia during labor in the United States, compared with 70% of non-Hispanic Black women and 65% of Hispanic women, according to birth certificate data. Among women without health insurance, half receive epidurals.

Programs that inform pregnant women about epidural use, expand Medicaid, and provide in-house obstetric anesthesia teams “may improve patient participation in clinical decision making and access to care,” study author Guohua Li, MD, DrPH, of Columbia University, New York, said in a statement about the research.

Earlier data from France showed that neuraxial analgesia is associated with reduced risk for severe postpartum hemorrhage. To examine the association between labor neuraxial analgesia and severe maternal morbidity in the United States, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed more than 575,000 vaginal deliveries in New York hospitals between 2010 and 2017; about half (47.4%) of the women received epidurals during labor.

The researchers focused on severe maternal morbidity, including 16 complications, such as heart failure and sepsis, and five procedures, including hysterectomy and ventilation.

They also considered patient characteristics and comorbidities and hospital-related factors to identify patients who were at higher risk for injury or death.

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 1.3% of the women. Of the 7,712 women with severe morbidity, more than one in three (35.6%) experienced postpartum hemorrhage.

The overall incidence of severe maternal morbidity was 1.3% among women who received an epidural injection and 1.4% among those who did not. In a weighted analysis, the adjusted odds ratio of severe maternal morbidity associated with epidurals was 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.82-0.90).

The study is limited by its observational design and does not prove causation, the authors acknowledged.

“Labor neuraxial analgesia may facilitate early evaluation and management of the third stage of labor to avoid escalation of postpartum hemorrhaging into grave complications and death,” study author Jean Guglielminotti, MD, PhD, an anesthesiologist at Columbia University, said in a statement.

Concerning trends

The Department of Health & Human Services has labeled severe maternal morbidity a public health priority. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show an increase in maternal mortality rates and worsening disparities by race and ethnicity.

According to the CDC, 861 women died of maternal causes in 2020, up from 754 in 2019. The rate of maternal mortality increased from 20.1 to 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births.

For Black women, however, the maternal mortality rate was far higher: 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births – nearly triple the figure of 19.1 per 100,000 for White women. Between 2019 and 2020, the mortality rate increased significantly for Black and Hispanic women, but not White mothers.

Researchers affiliated with University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children agreed in an accompanying editorial that more access to neuraxial labor analgesia for vaginal delivery might improve maternal health outcomes and “may be a strategy well worth pursuing in public health policy.”

The intervention is relatively safe and can “alleviate discomfort and distress,” they wrote.

Neuraxial anesthesia in surgical procedures has been shown to decrease the risk for complications like deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, transfusion requirements, and kidney failure, said editorialists Evelina Pankiv, MD; Alan Yang, MSc; and Kazuyoshi Aoyama, MD, PhD.

Benefits potentially could stem from improving blood flow, mitigating hypercoagulation, or reducing surgical stress response. But there are rare risks to consider as well, including hemorrhage, infection, and neurologic injury, they added.

Guglielminotti disclosed grants from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Aoyama reported receiving grants from the Perioperative Services Facilitator Grant Program and Hospital for Sick Children. The other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of neuraxial analgesia for vaginal delivery is associated with a 14% decreased risk for severe maternal morbidity, in part from a reduction in postpartum hemorrhage, new research shows.

The findings indicate that increasing the use of epidural or combined spinal-epidural analgesia may improve maternal health outcomes, especially for Hispanic, Black, and uninsured women who are less likely than White women to receive these interventions, according to the researchers, who published their findings online in JAMA Network Open.

About 80% of non-Hispanic White women receive neuraxial analgesia during labor in the United States, compared with 70% of non-Hispanic Black women and 65% of Hispanic women, according to birth certificate data. Among women without health insurance, half receive epidurals.

Programs that inform pregnant women about epidural use, expand Medicaid, and provide in-house obstetric anesthesia teams “may improve patient participation in clinical decision making and access to care,” study author Guohua Li, MD, DrPH, of Columbia University, New York, said in a statement about the research.

Earlier data from France showed that neuraxial analgesia is associated with reduced risk for severe postpartum hemorrhage. To examine the association between labor neuraxial analgesia and severe maternal morbidity in the United States, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed more than 575,000 vaginal deliveries in New York hospitals between 2010 and 2017; about half (47.4%) of the women received epidurals during labor.

The researchers focused on severe maternal morbidity, including 16 complications, such as heart failure and sepsis, and five procedures, including hysterectomy and ventilation.

They also considered patient characteristics and comorbidities and hospital-related factors to identify patients who were at higher risk for injury or death.

Severe maternal morbidity occurred in 1.3% of the women. Of the 7,712 women with severe morbidity, more than one in three (35.6%) experienced postpartum hemorrhage.

The overall incidence of severe maternal morbidity was 1.3% among women who received an epidural injection and 1.4% among those who did not. In a weighted analysis, the adjusted odds ratio of severe maternal morbidity associated with epidurals was 0.86 (95% confidence interval, 0.82-0.90).

The study is limited by its observational design and does not prove causation, the authors acknowledged.

“Labor neuraxial analgesia may facilitate early evaluation and management of the third stage of labor to avoid escalation of postpartum hemorrhaging into grave complications and death,” study author Jean Guglielminotti, MD, PhD, an anesthesiologist at Columbia University, said in a statement.

Concerning trends

The Department of Health & Human Services has labeled severe maternal morbidity a public health priority. Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show an increase in maternal mortality rates and worsening disparities by race and ethnicity.

According to the CDC, 861 women died of maternal causes in 2020, up from 754 in 2019. The rate of maternal mortality increased from 20.1 to 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births.

For Black women, however, the maternal mortality rate was far higher: 55.3 deaths per 100,000 live births – nearly triple the figure of 19.1 per 100,000 for White women. Between 2019 and 2020, the mortality rate increased significantly for Black and Hispanic women, but not White mothers.

Researchers affiliated with University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children agreed in an accompanying editorial that more access to neuraxial labor analgesia for vaginal delivery might improve maternal health outcomes and “may be a strategy well worth pursuing in public health policy.”

The intervention is relatively safe and can “alleviate discomfort and distress,” they wrote.

Neuraxial anesthesia in surgical procedures has been shown to decrease the risk for complications like deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, transfusion requirements, and kidney failure, said editorialists Evelina Pankiv, MD; Alan Yang, MSc; and Kazuyoshi Aoyama, MD, PhD.

Benefits potentially could stem from improving blood flow, mitigating hypercoagulation, or reducing surgical stress response. But there are rare risks to consider as well, including hemorrhage, infection, and neurologic injury, they added.

Guglielminotti disclosed grants from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Aoyama reported receiving grants from the Perioperative Services Facilitator Grant Program and Hospital for Sick Children. The other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Former APA president suspended by Columbia for ‘racist’ tweet

The university had not confirmed the suspension to this news organization by press time, but a letter from the school’s leadership notifying staff of the suspension was posted on Twitter the morning of Feb. 23 by addiction psychiatrist Jeremy Kidd, MD, who is a colleague of Dr. Lieberman’s at Columbia.

The suspension comes in the wake of Dr. Lieberman’s Feb. 21 tweet that drew immediate backlash by Twitter users who characterized it as racist and misogynist.

Dr. Lieberman, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, reportedly deleted the tweet and his entire Twitter account soon after, according to NewsOne.

However, the tweet was captured by others, including Jack Turban, MD, a child psychiatry fellow at Stanford University. In Turban’s retweet, Dr. Lieberman commented on a tweet about a black model, noting, “whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

The response on Twitter was swift. “My ancestors would roll over in their graves if I refrained from commentary on how anti-Blackness shows up in ‘compliments,’” tweeted Jessica Isom, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist at Yale University.

Dr. Turban speculated that there will be no consequences for Dr. Lieberman, adding in his tweet, “He will continue to make the hiring decisions (including for faculty candidates who are women of color).”

Apology letter?

David Pagliaccio, a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, posted what appeared to be an apology letter from Dr. Lieberman, although it could not be verified by this news organization.

In it, Dr. Lieberman was quoted as saying, “Yesterday, I tweeted from my personal account a message that was racist and sexist,” adding that prejudices he didn’t know he had held had been exposed, “and I’m deeply ashamed and very sorry.”

“I’ve hurt many, and I am beginning to understand the work ahead to make needed personal changes and over time to regain your trust,” Dr. Lieberman added.

Dr. Kidd called the suspension “absolutely the right move.” He added in his tweet that it “is only the beginning of what Columbia must do to heal & earn the trust our patients & trainees place in us every day.”

This news organization’s queries to Columbia University and to Dr. Lieberman were not returned by press time.

Dr. Lieberman is also director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, was an advisory board member for Medscape Psychiatry and a frequent columnist for Medscape Medical News (sister organizations of MDedge.com), and was a consultant for Clinical Psychiatry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The university had not confirmed the suspension to this news organization by press time, but a letter from the school’s leadership notifying staff of the suspension was posted on Twitter the morning of Feb. 23 by addiction psychiatrist Jeremy Kidd, MD, who is a colleague of Dr. Lieberman’s at Columbia.

The suspension comes in the wake of Dr. Lieberman’s Feb. 21 tweet that drew immediate backlash by Twitter users who characterized it as racist and misogynist.

Dr. Lieberman, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, reportedly deleted the tweet and his entire Twitter account soon after, according to NewsOne.

However, the tweet was captured by others, including Jack Turban, MD, a child psychiatry fellow at Stanford University. In Turban’s retweet, Dr. Lieberman commented on a tweet about a black model, noting, “whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

The response on Twitter was swift. “My ancestors would roll over in their graves if I refrained from commentary on how anti-Blackness shows up in ‘compliments,’” tweeted Jessica Isom, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist at Yale University.

Dr. Turban speculated that there will be no consequences for Dr. Lieberman, adding in his tweet, “He will continue to make the hiring decisions (including for faculty candidates who are women of color).”

Apology letter?

David Pagliaccio, a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, posted what appeared to be an apology letter from Dr. Lieberman, although it could not be verified by this news organization.

In it, Dr. Lieberman was quoted as saying, “Yesterday, I tweeted from my personal account a message that was racist and sexist,” adding that prejudices he didn’t know he had held had been exposed, “and I’m deeply ashamed and very sorry.”

“I’ve hurt many, and I am beginning to understand the work ahead to make needed personal changes and over time to regain your trust,” Dr. Lieberman added.

Dr. Kidd called the suspension “absolutely the right move.” He added in his tweet that it “is only the beginning of what Columbia must do to heal & earn the trust our patients & trainees place in us every day.”

This news organization’s queries to Columbia University and to Dr. Lieberman were not returned by press time.

Dr. Lieberman is also director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, was an advisory board member for Medscape Psychiatry and a frequent columnist for Medscape Medical News (sister organizations of MDedge.com), and was a consultant for Clinical Psychiatry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The university had not confirmed the suspension to this news organization by press time, but a letter from the school’s leadership notifying staff of the suspension was posted on Twitter the morning of Feb. 23 by addiction psychiatrist Jeremy Kidd, MD, who is a colleague of Dr. Lieberman’s at Columbia.

The suspension comes in the wake of Dr. Lieberman’s Feb. 21 tweet that drew immediate backlash by Twitter users who characterized it as racist and misogynist.

Dr. Lieberman, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, reportedly deleted the tweet and his entire Twitter account soon after, according to NewsOne.

However, the tweet was captured by others, including Jack Turban, MD, a child psychiatry fellow at Stanford University. In Turban’s retweet, Dr. Lieberman commented on a tweet about a black model, noting, “whether a work of art or a freak of nature she’s a beautiful sight to behold.”

The response on Twitter was swift. “My ancestors would roll over in their graves if I refrained from commentary on how anti-Blackness shows up in ‘compliments,’” tweeted Jessica Isom, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist at Yale University.

Dr. Turban speculated that there will be no consequences for Dr. Lieberman, adding in his tweet, “He will continue to make the hiring decisions (including for faculty candidates who are women of color).”

Apology letter?

David Pagliaccio, a research scientist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, posted what appeared to be an apology letter from Dr. Lieberman, although it could not be verified by this news organization.

In it, Dr. Lieberman was quoted as saying, “Yesterday, I tweeted from my personal account a message that was racist and sexist,” adding that prejudices he didn’t know he had held had been exposed, “and I’m deeply ashamed and very sorry.”

“I’ve hurt many, and I am beginning to understand the work ahead to make needed personal changes and over time to regain your trust,” Dr. Lieberman added.

Dr. Kidd called the suspension “absolutely the right move.” He added in his tweet that it “is only the beginning of what Columbia must do to heal & earn the trust our patients & trainees place in us every day.”

This news organization’s queries to Columbia University and to Dr. Lieberman were not returned by press time.

Dr. Lieberman is also director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, was an advisory board member for Medscape Psychiatry and a frequent columnist for Medscape Medical News (sister organizations of MDedge.com), and was a consultant for Clinical Psychiatry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Poor trial representation tied to worse breast cancer survival

Women with early-stage breast cancer who are poorly represented in clinical trials have worse survival than their well-represented peers, according to a real-world analysis.

The study shows that more than half of women with early breast cancer are not well represented in clinical trials because of age, comorbidities, or race, yet they receive therapies based on the results of these trials.

“The most interesting finding is that patients with comorbidities resulting in lab abnormalities that would typically exclude them from receiving medication on a trial are still frequently receiving these medications and have an almost threefold higher mortality,” Gabrielle Rocque, MD, with the division of hematology and oncology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, told this news organization.

“We need to do a deeper dive to better understand what is driving this mortality difference and test specific medications in patients with these conditions to understand the optimal treatment for this population,” Dr. Rocque added.

The study was published Feb. 1 in JCO Oncology Practice.

Many patient groups are not well represented in clinical trials, including patients of color, older patients, and those with comorbidities, and it remains unclear how treatment outcomes may differ among these patients, compared with those who are well represented in trials.

To investigate, Dr. Rocque and colleagues looked at 11,770 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer between 2005 and 2015 in the American Society of Clinical Oncology CancerLinQ database.

White women between 45 and 69 years of age with no comorbid conditions were considered well represented and made up 48% of the cohort.

Non-White women and/or those younger than 45 years or older than 70 were considered under represented and made up 45% of the cohort. The unrepresented group (7%) included women with comorbidities – such as liver disease, renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, anemia, or uncontrolled diabetes – or concurrent cancer.

The majority of the women received a high-intensity chemotherapy regimen, including 58% of unrepresented, 66% of underrepresented, and 63% of well-represented patients.

Compared with well-represented women, unrepresented women had a higher risk of death at 5 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.71; 95% confidence interval, 2.08-3.52).

Overall, the team found no significant increase in the risk of death at 5 years in underrepresented vs. well-represented women (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.98-1.45). However, that risk varied with age. Among underrepresented women, those aged 70 and older had more than a twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 2.21), while those younger than 45 had a lower risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 0.63), compared with those aged 45-69 years.

For three cancer subtypes, unrepresented patients had a greater than twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality, compared with well-represented patients (aHR, 2.50 for HER2-positive disease; aHR, 2.54 for HR-positive/HER2-negative disease; and aHR, 2.75 for triple-negative disease).

Underrepresented patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease had a 38% increased risk of 5-year mortality, compared with their well-represented peers (aHR, 1.38). However, there were no significant differences in 5-year mortality for underrepresented vs. well-represented patients with HER2-positive or triple-negative subtypes.

Risky business?

This analysis shows that unrepresented populations receive common treatment regimens at a similar rate as well-represented patients, the researchers note.

“By excluding patients with differing clinical conditions from trials but including them in the population to which drugs can be disseminated, one runs the risk of inadvertently causing injury,” the authors caution.

“To inform the practice of evidence-based medicine in an equitable manner, our findings support a need to both expand clinical trial inclusion criteria and report on clinical trial outcomes by clinical and demographic characteristics,” Dr. Rocque and colleagues conclude.

Charles Shapiro, MD, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is not surprised by the findings of this study.

“We know that clinical trials are too restrictive and include only a selected population largely without comorbidities, but in the real world, people have comorbidities,” Dr. Shapiro, who was not involved in the research, told this news organization.

The study “starkly illustrates” the poorer survival of populations not represented in clinical trials.

“It could be that we need to change clinical trials, maybe ask fewer questions or maybe ask more important questions and loosen the eligibility up, because in the real world, there are people with comorbidities and people who are over 70,” Dr. Shapiro stated.

Are strides being made to change that? “Not really,” Dr. Shapiro said in an interview.

The study was supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the American Cancer Society. Dr. Rocque has served as a consultant or advisor for Pfizer; has received research funding from Carevive Systems, Genentech, and Pfizer; and has received travel, accommodations, and expenses from Carevive. Dr. Shapiro has financial relationships with UptoDate, 2nd MD, and Anthenum.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with early-stage breast cancer who are poorly represented in clinical trials have worse survival than their well-represented peers, according to a real-world analysis.

The study shows that more than half of women with early breast cancer are not well represented in clinical trials because of age, comorbidities, or race, yet they receive therapies based on the results of these trials.

“The most interesting finding is that patients with comorbidities resulting in lab abnormalities that would typically exclude them from receiving medication on a trial are still frequently receiving these medications and have an almost threefold higher mortality,” Gabrielle Rocque, MD, with the division of hematology and oncology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, told this news organization.

“We need to do a deeper dive to better understand what is driving this mortality difference and test specific medications in patients with these conditions to understand the optimal treatment for this population,” Dr. Rocque added.

The study was published Feb. 1 in JCO Oncology Practice.

Many patient groups are not well represented in clinical trials, including patients of color, older patients, and those with comorbidities, and it remains unclear how treatment outcomes may differ among these patients, compared with those who are well represented in trials.

To investigate, Dr. Rocque and colleagues looked at 11,770 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer between 2005 and 2015 in the American Society of Clinical Oncology CancerLinQ database.

White women between 45 and 69 years of age with no comorbid conditions were considered well represented and made up 48% of the cohort.

Non-White women and/or those younger than 45 years or older than 70 were considered under represented and made up 45% of the cohort. The unrepresented group (7%) included women with comorbidities – such as liver disease, renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, anemia, or uncontrolled diabetes – or concurrent cancer.

The majority of the women received a high-intensity chemotherapy regimen, including 58% of unrepresented, 66% of underrepresented, and 63% of well-represented patients.

Compared with well-represented women, unrepresented women had a higher risk of death at 5 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.71; 95% confidence interval, 2.08-3.52).

Overall, the team found no significant increase in the risk of death at 5 years in underrepresented vs. well-represented women (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.98-1.45). However, that risk varied with age. Among underrepresented women, those aged 70 and older had more than a twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 2.21), while those younger than 45 had a lower risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 0.63), compared with those aged 45-69 years.

For three cancer subtypes, unrepresented patients had a greater than twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality, compared with well-represented patients (aHR, 2.50 for HER2-positive disease; aHR, 2.54 for HR-positive/HER2-negative disease; and aHR, 2.75 for triple-negative disease).

Underrepresented patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease had a 38% increased risk of 5-year mortality, compared with their well-represented peers (aHR, 1.38). However, there were no significant differences in 5-year mortality for underrepresented vs. well-represented patients with HER2-positive or triple-negative subtypes.

Risky business?

This analysis shows that unrepresented populations receive common treatment regimens at a similar rate as well-represented patients, the researchers note.

“By excluding patients with differing clinical conditions from trials but including them in the population to which drugs can be disseminated, one runs the risk of inadvertently causing injury,” the authors caution.

“To inform the practice of evidence-based medicine in an equitable manner, our findings support a need to both expand clinical trial inclusion criteria and report on clinical trial outcomes by clinical and demographic characteristics,” Dr. Rocque and colleagues conclude.

Charles Shapiro, MD, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is not surprised by the findings of this study.

“We know that clinical trials are too restrictive and include only a selected population largely without comorbidities, but in the real world, people have comorbidities,” Dr. Shapiro, who was not involved in the research, told this news organization.

The study “starkly illustrates” the poorer survival of populations not represented in clinical trials.

“It could be that we need to change clinical trials, maybe ask fewer questions or maybe ask more important questions and loosen the eligibility up, because in the real world, there are people with comorbidities and people who are over 70,” Dr. Shapiro stated.

Are strides being made to change that? “Not really,” Dr. Shapiro said in an interview.

The study was supported by grants from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the American Cancer Society. Dr. Rocque has served as a consultant or advisor for Pfizer; has received research funding from Carevive Systems, Genentech, and Pfizer; and has received travel, accommodations, and expenses from Carevive. Dr. Shapiro has financial relationships with UptoDate, 2nd MD, and Anthenum.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with early-stage breast cancer who are poorly represented in clinical trials have worse survival than their well-represented peers, according to a real-world analysis.

The study shows that more than half of women with early breast cancer are not well represented in clinical trials because of age, comorbidities, or race, yet they receive therapies based on the results of these trials.

“The most interesting finding is that patients with comorbidities resulting in lab abnormalities that would typically exclude them from receiving medication on a trial are still frequently receiving these medications and have an almost threefold higher mortality,” Gabrielle Rocque, MD, with the division of hematology and oncology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, told this news organization.

“We need to do a deeper dive to better understand what is driving this mortality difference and test specific medications in patients with these conditions to understand the optimal treatment for this population,” Dr. Rocque added.

The study was published Feb. 1 in JCO Oncology Practice.

Many patient groups are not well represented in clinical trials, including patients of color, older patients, and those with comorbidities, and it remains unclear how treatment outcomes may differ among these patients, compared with those who are well represented in trials.

To investigate, Dr. Rocque and colleagues looked at 11,770 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer between 2005 and 2015 in the American Society of Clinical Oncology CancerLinQ database.

White women between 45 and 69 years of age with no comorbid conditions were considered well represented and made up 48% of the cohort.

Non-White women and/or those younger than 45 years or older than 70 were considered under represented and made up 45% of the cohort. The unrepresented group (7%) included women with comorbidities – such as liver disease, renal insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, anemia, or uncontrolled diabetes – or concurrent cancer.

The majority of the women received a high-intensity chemotherapy regimen, including 58% of unrepresented, 66% of underrepresented, and 63% of well-represented patients.

Compared with well-represented women, unrepresented women had a higher risk of death at 5 years (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.71; 95% confidence interval, 2.08-3.52).

Overall, the team found no significant increase in the risk of death at 5 years in underrepresented vs. well-represented women (aHR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.98-1.45). However, that risk varied with age. Among underrepresented women, those aged 70 and older had more than a twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 2.21), while those younger than 45 had a lower risk of 5-year mortality (aHR, 0.63), compared with those aged 45-69 years.

For three cancer subtypes, unrepresented patients had a greater than twofold higher risk of 5-year mortality, compared with well-represented patients (aHR, 2.50 for HER2-positive disease; aHR, 2.54 for HR-positive/HER2-negative disease; and aHR, 2.75 for triple-negative disease).

Underrepresented patients with HR-positive/HER2-negative disease had a 38% increased risk of 5-year mortality, compared with their well-represented peers (aHR, 1.38). However, there were no significant differences in 5-year mortality for underrepresented vs. well-represented patients with HER2-positive or triple-negative subtypes.

Risky business?

This analysis shows that unrepresented populations receive common treatment regimens at a similar rate as well-represented patients, the researchers note.

“By excluding patients with differing clinical conditions from trials but including them in the population to which drugs can be disseminated, one runs the risk of inadvertently causing injury,” the authors caution.

“To inform the practice of evidence-based medicine in an equitable manner, our findings support a need to both expand clinical trial inclusion criteria and report on clinical trial outcomes by clinical and demographic characteristics,” Dr. Rocque and colleagues conclude.

Charles Shapiro, MD, professor of medicine, hematology, and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, is not surprised by the findings of this study.