User login

Tips, contraindications for superficial chemical peels reviewed

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

CHICAGO – Heather Woolery-Lloyd, MD, says she’s generally “risk averse,” but when it comes to superficial chemical peels, she’s in her comfort zone.

Superficial peeling is “one of the most common cosmetic procedures that I do,” Dr. Woolery-Lloyd, director of the skin of color division in the dermatology department at the University of Miami, said at the Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

In her practice, .

Contraindications are an active bacterial infection, open wounds, and active herpes simplex virus. “If someone looks like they even have a remnant of a cold sore, I tell them to come back,” she said.

Setting expectations for patients is critical, Dr. Woolery-Lloyd said, as a series of superficial peels is needed before the desired results are evident.

The peel she uses most is salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxy acid, at a strength of 20%-30%. “It’s very effective on our acne patients,” she said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! “If you’re just starting with peels, I think this is a very safe one. You don’t have to time it, and you don’t have to neutralize it,” and at lower concentrations, is “very safe.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd provided these other tips during her presentation:

- Even superficial peels can be uncomfortable, she noted, so she keeps a fan nearby to use when needed to help with discomfort.

- Find the peel you’re comfortable with, master that peel, and don’t jump from peel to peel. Get familiar with the side effects and how to predict results.

- Stop retinoids up to 7 days before a peel. Consider placing the patient on hydroquinone before the chemical peel to decrease the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Before the procedure, prep the skin with acetone or alcohol. Applying petrolatum helps protect around the eyes, alar crease, and other sensitive areas, “or anywhere you’re concerned about the depth of the peel.”

- Application with rough gauze helps avoid the waste that comes with makeup sponges soaking up the product. It also helps add exfoliation.

- Have everything ready before starting the procedure, including (depending on the peel), a neutralizer or soapless cleanser. Although peels are generally safe, you want to be able to remove one quickly, if needed, without having to leave the room.

- Start with the lowest concentration (salicylic acid or glycolic acid) then titrate up. Ask patients about any reactions they experienced with the previous peel before making the decision on the next concentration.

- For a peel to treat hyperpigmentation, she recommends one peel about every 4 weeks for a series of 5-6 peels.

- After a peel, the patient should use a mineral sunscreen; chemical sunscreens will sting.

Know your comfort zone

Conference chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of The Vitiligo & Pigmentation Institute of Southern California in Los Angeles, said superficial peels are best for dermatologists new to peeling until they gain comfort with experience.

Superficial and medium-depth peels work well for mild to moderate photoaging, she said at the meeting.

“We know that in darker skin we have more intrinsic aging rather than photoaging. We have more textural changes, hyperpigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said.

For Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, she said, “you can do superficial, medium, and deep peels.” For darker skin types, “I typically stay in the superficial, medium range.”

She said that she uses retinoids to exfoliate before a superficial peel but added, “you’ve got to stop them early because retinoids can make a superficial peel a medium-depth peel.”

Taking photos is important before any procedure, she said, as is spending time with patients clarifying their outcome expectations.

“I love peeling,” Dr. Grimes said. “And it’s cost effective. If you don’t want to spend a ton of money, it’s amazing what you can achieve with chemical peeling.”

When asked by a member of the audience whether they avoid superficial peels in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, both Dr. Woolery-Lloyd and Dr. Grimes said they do avoid them in those patients.

Dr. Grimes said she tells her patients, especially in the first trimester, “I am the most conservative woman on the planet. I do nothing during the first trimester.”

Dr. Woolery-Lloyd has been a speaker for Ortho Dermatologics, Loreal and EPI, and has done research for Pfizer, Galderma, Allergan, Arcutis, Vyne, Merz, and Eirion. She has been on advisory boards for Loreal, Allergan, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfize,r and Merz. Dr. Grimes reports grant/research Support from Clinuvel Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson, LASEROPTEK, L’Oréal USA, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, skinbetter science, and Versicolor Technologies, and is on the speakers bureau/receives honoraria for non-CME for Incyte and Procter & Gamble; and is a consultant or is on the advisory board for L’Oréal USA and Procter & Gamble. She has stock options in Versicolor Technologies.

AT THE MEDSCAPE LIVE! PIGMENTARY DISORDERS SYMPOSIUM

Medicaid patients with heart failure get poor follow-up after hospital discharge

Nearly 60% of Medicaid-covered adults with concurrent diabetes and heart failure did not receive guideline-concordant postdischarge care within 7-10 days of leaving the hospital, according to a large Alabama study. Moreover, affected Black and Hispanic/other Alabamians were less likely than were their White counterparts to receive recommended postdischarge care.

In comparison with White participants, Black and Hispanic adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory care visits after HF hospitalization or had a delayed visit, according to researchers led by Yulia Khodneva, MD, PhD, an internist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “This is likely a reflection of a structural racism and implicit bias against racial and ethnic minorities that persists in the U.S. health care system,” she and her colleagues wrote.

The findings point to the need for strategies to improve access to postdischarge care for lower-income HF patients.

Among U.S. states, Alabama is the sixth-poorest, the third in diabetes prevalence (14%), and has the highest rates of heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality, the authors noted.

Study details

The cohort included 9,857 adults with diabetes and first hospitalizations for heart failure who were covered by Alabama Medicaid during 2010-2019. The investigators analyzed patients’ claims for ambulatory care (any, primary, cardiology, or endocrinology) within 60 days of discharge.

The mean age of participants was 53.7 years; 47.3% were Black; 41.8% non-Hispanic White; and 10.9% Hispanic/other, with other including those identifying as non-White Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian. About two-thirds (65.4%) of participants were women.

Analysis revealed low rates of follow-up care after hospital discharge; 26.7% had an ambulatory visit within 0-7 days, 15.2% within 8-14 days, 31.3% within 15-60 days, and 26.8% had no follow-up visit at all. Of those having a follow-up visit, 71% saw a primary care physician and 12% saw a cardiologist.

In contrast, a much higher proportion of heart failure patients in a Swedish registry – 63% – received ambulatory follow-up in cardiology.

Ethnic/gender/age disparities

Black and Hispanic/other adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory visit (P <.0001) or had the visit delayed by 1.8 days (P = .0006) and 2.8 days (P = .0016), respectively. They were less likely to see a primary care physician than were non-Hispanic White adults: adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.00) and 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89-0.98), respectively.

Men and those with longer-standing heart failure were less likely to be seen in primary care, while the presence of multiple comorbidities was associated with a higher likelihood of a postdischarge primary care visit. Men were more likely to be seen by a cardiologist, while older discharged patients were less likely to be seen by an endocrinologist within 60 days. There was a U-shaped relationship between the timing of the first postdischarge ambulatory visit and all-cause mortality among adults with diabetes and heart failure. Higher rates of 60-day all-cause mortality were observed both in those who had seen a provider within 0-7 days after discharge and in those who had not seen any provider during the 60-day study period compared with those having an ambulatory care visit within 7-14 or 15-60 days. “The group with early follow-up (0-7 days) likely represents a sicker population of patients with heart failure with more comorbidity burden and higher overall health care use, including readmissions, as was demonstrated in our analysis,” Dr. Khodneva and associates wrote. “Interventions that improve access to postdischarge ambulatory care for low-income patients with diabetes and heart failure and eliminate racial and ethnic disparities may be warranted,” they added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Khodneva reported funding from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Forge Ahead Center as well as from the NIDDK, the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Alabama Medicaid Agency. Coauthor Emily Levitan, ScD, reported research funding from Amgen and has served on Amgen advisory boards. She has also served as a scientific consultant for a research project funded by Novartis.

Nearly 60% of Medicaid-covered adults with concurrent diabetes and heart failure did not receive guideline-concordant postdischarge care within 7-10 days of leaving the hospital, according to a large Alabama study. Moreover, affected Black and Hispanic/other Alabamians were less likely than were their White counterparts to receive recommended postdischarge care.

In comparison with White participants, Black and Hispanic adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory care visits after HF hospitalization or had a delayed visit, according to researchers led by Yulia Khodneva, MD, PhD, an internist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “This is likely a reflection of a structural racism and implicit bias against racial and ethnic minorities that persists in the U.S. health care system,” she and her colleagues wrote.

The findings point to the need for strategies to improve access to postdischarge care for lower-income HF patients.

Among U.S. states, Alabama is the sixth-poorest, the third in diabetes prevalence (14%), and has the highest rates of heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality, the authors noted.

Study details

The cohort included 9,857 adults with diabetes and first hospitalizations for heart failure who were covered by Alabama Medicaid during 2010-2019. The investigators analyzed patients’ claims for ambulatory care (any, primary, cardiology, or endocrinology) within 60 days of discharge.

The mean age of participants was 53.7 years; 47.3% were Black; 41.8% non-Hispanic White; and 10.9% Hispanic/other, with other including those identifying as non-White Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian. About two-thirds (65.4%) of participants were women.

Analysis revealed low rates of follow-up care after hospital discharge; 26.7% had an ambulatory visit within 0-7 days, 15.2% within 8-14 days, 31.3% within 15-60 days, and 26.8% had no follow-up visit at all. Of those having a follow-up visit, 71% saw a primary care physician and 12% saw a cardiologist.

In contrast, a much higher proportion of heart failure patients in a Swedish registry – 63% – received ambulatory follow-up in cardiology.

Ethnic/gender/age disparities

Black and Hispanic/other adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory visit (P <.0001) or had the visit delayed by 1.8 days (P = .0006) and 2.8 days (P = .0016), respectively. They were less likely to see a primary care physician than were non-Hispanic White adults: adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.00) and 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89-0.98), respectively.

Men and those with longer-standing heart failure were less likely to be seen in primary care, while the presence of multiple comorbidities was associated with a higher likelihood of a postdischarge primary care visit. Men were more likely to be seen by a cardiologist, while older discharged patients were less likely to be seen by an endocrinologist within 60 days. There was a U-shaped relationship between the timing of the first postdischarge ambulatory visit and all-cause mortality among adults with diabetes and heart failure. Higher rates of 60-day all-cause mortality were observed both in those who had seen a provider within 0-7 days after discharge and in those who had not seen any provider during the 60-day study period compared with those having an ambulatory care visit within 7-14 or 15-60 days. “The group with early follow-up (0-7 days) likely represents a sicker population of patients with heart failure with more comorbidity burden and higher overall health care use, including readmissions, as was demonstrated in our analysis,” Dr. Khodneva and associates wrote. “Interventions that improve access to postdischarge ambulatory care for low-income patients with diabetes and heart failure and eliminate racial and ethnic disparities may be warranted,” they added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Khodneva reported funding from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Forge Ahead Center as well as from the NIDDK, the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Alabama Medicaid Agency. Coauthor Emily Levitan, ScD, reported research funding from Amgen and has served on Amgen advisory boards. She has also served as a scientific consultant for a research project funded by Novartis.

Nearly 60% of Medicaid-covered adults with concurrent diabetes and heart failure did not receive guideline-concordant postdischarge care within 7-10 days of leaving the hospital, according to a large Alabama study. Moreover, affected Black and Hispanic/other Alabamians were less likely than were their White counterparts to receive recommended postdischarge care.

In comparison with White participants, Black and Hispanic adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory care visits after HF hospitalization or had a delayed visit, according to researchers led by Yulia Khodneva, MD, PhD, an internist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “This is likely a reflection of a structural racism and implicit bias against racial and ethnic minorities that persists in the U.S. health care system,” she and her colleagues wrote.

The findings point to the need for strategies to improve access to postdischarge care for lower-income HF patients.

Among U.S. states, Alabama is the sixth-poorest, the third in diabetes prevalence (14%), and has the highest rates of heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality, the authors noted.

Study details

The cohort included 9,857 adults with diabetes and first hospitalizations for heart failure who were covered by Alabama Medicaid during 2010-2019. The investigators analyzed patients’ claims for ambulatory care (any, primary, cardiology, or endocrinology) within 60 days of discharge.

The mean age of participants was 53.7 years; 47.3% were Black; 41.8% non-Hispanic White; and 10.9% Hispanic/other, with other including those identifying as non-White Hispanic, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Asian. About two-thirds (65.4%) of participants were women.

Analysis revealed low rates of follow-up care after hospital discharge; 26.7% had an ambulatory visit within 0-7 days, 15.2% within 8-14 days, 31.3% within 15-60 days, and 26.8% had no follow-up visit at all. Of those having a follow-up visit, 71% saw a primary care physician and 12% saw a cardiologist.

In contrast, a much higher proportion of heart failure patients in a Swedish registry – 63% – received ambulatory follow-up in cardiology.

Ethnic/gender/age disparities

Black and Hispanic/other adults were less likely to have any postdischarge ambulatory visit (P <.0001) or had the visit delayed by 1.8 days (P = .0006) and 2.8 days (P = .0016), respectively. They were less likely to see a primary care physician than were non-Hispanic White adults: adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91-1.00) and 0.91 (95% CI, 0.89-0.98), respectively.

Men and those with longer-standing heart failure were less likely to be seen in primary care, while the presence of multiple comorbidities was associated with a higher likelihood of a postdischarge primary care visit. Men were more likely to be seen by a cardiologist, while older discharged patients were less likely to be seen by an endocrinologist within 60 days. There was a U-shaped relationship between the timing of the first postdischarge ambulatory visit and all-cause mortality among adults with diabetes and heart failure. Higher rates of 60-day all-cause mortality were observed both in those who had seen a provider within 0-7 days after discharge and in those who had not seen any provider during the 60-day study period compared with those having an ambulatory care visit within 7-14 or 15-60 days. “The group with early follow-up (0-7 days) likely represents a sicker population of patients with heart failure with more comorbidity burden and higher overall health care use, including readmissions, as was demonstrated in our analysis,” Dr. Khodneva and associates wrote. “Interventions that improve access to postdischarge ambulatory care for low-income patients with diabetes and heart failure and eliminate racial and ethnic disparities may be warranted,” they added.

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Diabetes Research Center. Dr. Khodneva reported funding from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Forge Ahead Center as well as from the NIDDK, the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Alabama Medicaid Agency. Coauthor Emily Levitan, ScD, reported research funding from Amgen and has served on Amgen advisory boards. She has also served as a scientific consultant for a research project funded by Novartis.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Racial, ethnic disparities persist in access to MS care

Aurora, Colo. – , according to research on patient-reported health inequities presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

”Equal access to and quality of care are critical for managing a progressive disease such as multiple sclerosis,” said Chris Hardy, of Publicis Health Media, and her associates. “Despite increased awareness of health outcome disparities in the U.S., certain patients still experience inequities in care.”

The researchers sent emails to members of MyMSTeam, an online support network of more than 197,000 members, to request completion of a 34-question online survey. Questions addressed respondents’ ability to access care, resources in their neighborhood, and their interactions with their health care providers. Questions also addressed the burden of MS on individuals’ quality of life, which was considerable across all demographics. The 1,935 patients with MS who responded were overwhelmingly White, though the demographics varied by question.

A ‘widespread and significant problem’

“This study is important in pointing out the unfortunate, obvious [fact] that lack of access and lack of availability to treatment is still a widespread and significant problem in this country,” commented Mark Gudesblatt, MD, a neurologist at South Shore Neurologic Associates who was not involved in the study. “Improving effective treatment of disease requires a more granular understanding of disease impact on a quantitative, multidimensional, objective patient-centric approach,” he added. “Racial and ethnic barriers to effective treatment cannot be allowed nor tolerated. We need to be more acutely aware that outreach, digital health, and remote assessments are tools that we need to incorporate to improve access and do better.”

The pervasive impact of MS

Overall, 85% of respondents reported that MS made it harder to do everyday chores, and 84% said their MS made it harder to exercise and interfered with their everyday life. Similarly high proportions of respondents reported that their MS causes them a lot of stress (80%), makes them feel anxious or depressed (77%), disrupts their work/employment (75%), and interferes with their social life (75%). In addition, more than half said their diagnosis negatively affects their family (59%) and makes them feel judged (53%).

Deanne Power, RN, MSCN, the lead nurse care partner at Octave Bioscience, who spoke as a representative of the study authors, said it’s critical that clinicians be aware of the health inequities that exist among their patient population.

“Some patients have lower income or language issues where English is not their primary language, and they don’t have access and are even afraid to call doctor or reach out [for help],” Ms. Power said. “If providers aren’t actively aware of these situations and talk to their patients, they can’t just say, ‘Oh, well, I just want you to go fill this prescription,’ when they don’t have money to put food on their table. Providers have got to know their patients as [more than] just an MS patient. This is a human being in front of you, and you better know what their life is like, because it’s impacting their MS.”

Access to care varied by race

Among the 1,906 respondents who answered questions about access to care, 9% were Black, 5% were Hispanic, and the rest were White. In these questions, differences between demographics arose when it came to individuals’ ability to conveniently see an MS specialist and their subsequent use of emergency services. For example, only 64% of Hispanic respondents reported convenient access to a health care provider specializing in MS, compared with 76% of White and 78% of Black respondents.

A significantly higher proportion of Hispanics also reported that they could not take time off from work when they were sick (25%) or to attend a doctor appointment (20%), compared with White (15% and 9%, respectively) and Black (18% and 12%) respondents. Meanwhile, a significantly higher proportion of Hispanics (35%) reported visiting the emergency department in the past year for MS-related issues, compared with White (19%) or Black (25%) respondents.

White respondents consistently had greater convenient access to dental offices, healthy foods, outpatient care, gyms, and parks and trails, compared with Black and Hispanic patients’ access. For example, 85% of White patients had convenient access to dental offices and 72% had access to outpatient care, compared with Black (74% and 65%) and Hispanic (78% and 52%) patients. Two-thirds of Hispanic respondents (67%) reported access to healthy foods and to gyms, parks, or trails, compared with more than three-quarters of both White and Black patients.

Other barriers to MS care

Both racial/ethnic and gender disparities emerged in how patients felt treated by their health care providers. Men were significantly more likely (70%) than women (65%) to say their health care provider listens to and understands them. A statistically significant higher proportion of men (71%) also said their clinician explained their MS test results to them, compared with women (62%), and only 28% of women, versus 37% of men, said their provider developed a long-term plan for them.

Anne Foelsch, the vice president of strategic partnerships at MyHealthTeam, who works with the authors, noted the large discrepancy that was seen particularly for Hispanic patients in terms of how they felt treated by their health care provider.

“Doctors might perceive that the relationship is the same with all of their patients when their patients have a very different perception of what that relationship is and whether they’re not being heard,” Ms. Foelsch said. “It’s important that clinicians take a little bit of time and learn a little bit more about a patient’s perspective and what it’s like when they have a chronic condition like MS and how it impacts their life, looking for those nuances that are different based on your ethnicity.”

Just over half of Hispanic patients (54%) said their provider explained their MS test results, compared with nearly two-thirds of White patients (65%) and 61% of Black patients. Hispanic patients were also less likely (55%) to say they felt their provider listens to and understands them than White (67%) or Black (65%) patients. Two-thirds of White respondents (67%) said their doctor recommended regular check-ups, compared with just over half of Black and Hispanic respondents (55%).

Other statistically significant disparities by race/ethnicity, where a higher proportion of White patients responded affirmatively than Black or Hispanic patients, included feeling treated with respect by their health care provider, feeling their provider is nonjudgmental, and saying their provider spends enough time with them, addresses their MS symptoms, and encourages shared decision-making.

“This study nicely documents and points out that despite our best intentions, we need to do much better as a community to help those with chronic and potentially disabling diseases like MS,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. “The racial, ethnic, and gender disparities only result in greater disability and societal costs by those who can least afford it. All therapies fail due to nonadherence, limited access, lack of insurance coverage, limited insurance coverage, high copays, long waits, cultural biases, and more.”

The researchers acknowledged that their survey respondents may not be representative of all patients with MS because the survey relied on those who chose to respond to the online survey.

The study authors were all employees of Publicis Health Media or MyHealthTeam. Dr. Gudesblatt reported no disclosures.

Aurora, Colo. – , according to research on patient-reported health inequities presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

”Equal access to and quality of care are critical for managing a progressive disease such as multiple sclerosis,” said Chris Hardy, of Publicis Health Media, and her associates. “Despite increased awareness of health outcome disparities in the U.S., certain patients still experience inequities in care.”

The researchers sent emails to members of MyMSTeam, an online support network of more than 197,000 members, to request completion of a 34-question online survey. Questions addressed respondents’ ability to access care, resources in their neighborhood, and their interactions with their health care providers. Questions also addressed the burden of MS on individuals’ quality of life, which was considerable across all demographics. The 1,935 patients with MS who responded were overwhelmingly White, though the demographics varied by question.

A ‘widespread and significant problem’

“This study is important in pointing out the unfortunate, obvious [fact] that lack of access and lack of availability to treatment is still a widespread and significant problem in this country,” commented Mark Gudesblatt, MD, a neurologist at South Shore Neurologic Associates who was not involved in the study. “Improving effective treatment of disease requires a more granular understanding of disease impact on a quantitative, multidimensional, objective patient-centric approach,” he added. “Racial and ethnic barriers to effective treatment cannot be allowed nor tolerated. We need to be more acutely aware that outreach, digital health, and remote assessments are tools that we need to incorporate to improve access and do better.”

The pervasive impact of MS

Overall, 85% of respondents reported that MS made it harder to do everyday chores, and 84% said their MS made it harder to exercise and interfered with their everyday life. Similarly high proportions of respondents reported that their MS causes them a lot of stress (80%), makes them feel anxious or depressed (77%), disrupts their work/employment (75%), and interferes with their social life (75%). In addition, more than half said their diagnosis negatively affects their family (59%) and makes them feel judged (53%).

Deanne Power, RN, MSCN, the lead nurse care partner at Octave Bioscience, who spoke as a representative of the study authors, said it’s critical that clinicians be aware of the health inequities that exist among their patient population.

“Some patients have lower income or language issues where English is not their primary language, and they don’t have access and are even afraid to call doctor or reach out [for help],” Ms. Power said. “If providers aren’t actively aware of these situations and talk to their patients, they can’t just say, ‘Oh, well, I just want you to go fill this prescription,’ when they don’t have money to put food on their table. Providers have got to know their patients as [more than] just an MS patient. This is a human being in front of you, and you better know what their life is like, because it’s impacting their MS.”

Access to care varied by race

Among the 1,906 respondents who answered questions about access to care, 9% were Black, 5% were Hispanic, and the rest were White. In these questions, differences between demographics arose when it came to individuals’ ability to conveniently see an MS specialist and their subsequent use of emergency services. For example, only 64% of Hispanic respondents reported convenient access to a health care provider specializing in MS, compared with 76% of White and 78% of Black respondents.

A significantly higher proportion of Hispanics also reported that they could not take time off from work when they were sick (25%) or to attend a doctor appointment (20%), compared with White (15% and 9%, respectively) and Black (18% and 12%) respondents. Meanwhile, a significantly higher proportion of Hispanics (35%) reported visiting the emergency department in the past year for MS-related issues, compared with White (19%) or Black (25%) respondents.

White respondents consistently had greater convenient access to dental offices, healthy foods, outpatient care, gyms, and parks and trails, compared with Black and Hispanic patients’ access. For example, 85% of White patients had convenient access to dental offices and 72% had access to outpatient care, compared with Black (74% and 65%) and Hispanic (78% and 52%) patients. Two-thirds of Hispanic respondents (67%) reported access to healthy foods and to gyms, parks, or trails, compared with more than three-quarters of both White and Black patients.

Other barriers to MS care

Both racial/ethnic and gender disparities emerged in how patients felt treated by their health care providers. Men were significantly more likely (70%) than women (65%) to say their health care provider listens to and understands them. A statistically significant higher proportion of men (71%) also said their clinician explained their MS test results to them, compared with women (62%), and only 28% of women, versus 37% of men, said their provider developed a long-term plan for them.

Anne Foelsch, the vice president of strategic partnerships at MyHealthTeam, who works with the authors, noted the large discrepancy that was seen particularly for Hispanic patients in terms of how they felt treated by their health care provider.

“Doctors might perceive that the relationship is the same with all of their patients when their patients have a very different perception of what that relationship is and whether they’re not being heard,” Ms. Foelsch said. “It’s important that clinicians take a little bit of time and learn a little bit more about a patient’s perspective and what it’s like when they have a chronic condition like MS and how it impacts their life, looking for those nuances that are different based on your ethnicity.”

Just over half of Hispanic patients (54%) said their provider explained their MS test results, compared with nearly two-thirds of White patients (65%) and 61% of Black patients. Hispanic patients were also less likely (55%) to say they felt their provider listens to and understands them than White (67%) or Black (65%) patients. Two-thirds of White respondents (67%) said their doctor recommended regular check-ups, compared with just over half of Black and Hispanic respondents (55%).

Other statistically significant disparities by race/ethnicity, where a higher proportion of White patients responded affirmatively than Black or Hispanic patients, included feeling treated with respect by their health care provider, feeling their provider is nonjudgmental, and saying their provider spends enough time with them, addresses their MS symptoms, and encourages shared decision-making.

“This study nicely documents and points out that despite our best intentions, we need to do much better as a community to help those with chronic and potentially disabling diseases like MS,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. “The racial, ethnic, and gender disparities only result in greater disability and societal costs by those who can least afford it. All therapies fail due to nonadherence, limited access, lack of insurance coverage, limited insurance coverage, high copays, long waits, cultural biases, and more.”

The researchers acknowledged that their survey respondents may not be representative of all patients with MS because the survey relied on those who chose to respond to the online survey.

The study authors were all employees of Publicis Health Media or MyHealthTeam. Dr. Gudesblatt reported no disclosures.

Aurora, Colo. – , according to research on patient-reported health inequities presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

”Equal access to and quality of care are critical for managing a progressive disease such as multiple sclerosis,” said Chris Hardy, of Publicis Health Media, and her associates. “Despite increased awareness of health outcome disparities in the U.S., certain patients still experience inequities in care.”

The researchers sent emails to members of MyMSTeam, an online support network of more than 197,000 members, to request completion of a 34-question online survey. Questions addressed respondents’ ability to access care, resources in their neighborhood, and their interactions with their health care providers. Questions also addressed the burden of MS on individuals’ quality of life, which was considerable across all demographics. The 1,935 patients with MS who responded were overwhelmingly White, though the demographics varied by question.

A ‘widespread and significant problem’

“This study is important in pointing out the unfortunate, obvious [fact] that lack of access and lack of availability to treatment is still a widespread and significant problem in this country,” commented Mark Gudesblatt, MD, a neurologist at South Shore Neurologic Associates who was not involved in the study. “Improving effective treatment of disease requires a more granular understanding of disease impact on a quantitative, multidimensional, objective patient-centric approach,” he added. “Racial and ethnic barriers to effective treatment cannot be allowed nor tolerated. We need to be more acutely aware that outreach, digital health, and remote assessments are tools that we need to incorporate to improve access and do better.”

The pervasive impact of MS

Overall, 85% of respondents reported that MS made it harder to do everyday chores, and 84% said their MS made it harder to exercise and interfered with their everyday life. Similarly high proportions of respondents reported that their MS causes them a lot of stress (80%), makes them feel anxious or depressed (77%), disrupts their work/employment (75%), and interferes with their social life (75%). In addition, more than half said their diagnosis negatively affects their family (59%) and makes them feel judged (53%).

Deanne Power, RN, MSCN, the lead nurse care partner at Octave Bioscience, who spoke as a representative of the study authors, said it’s critical that clinicians be aware of the health inequities that exist among their patient population.

“Some patients have lower income or language issues where English is not their primary language, and they don’t have access and are even afraid to call doctor or reach out [for help],” Ms. Power said. “If providers aren’t actively aware of these situations and talk to their patients, they can’t just say, ‘Oh, well, I just want you to go fill this prescription,’ when they don’t have money to put food on their table. Providers have got to know their patients as [more than] just an MS patient. This is a human being in front of you, and you better know what their life is like, because it’s impacting their MS.”

Access to care varied by race

Among the 1,906 respondents who answered questions about access to care, 9% were Black, 5% were Hispanic, and the rest were White. In these questions, differences between demographics arose when it came to individuals’ ability to conveniently see an MS specialist and their subsequent use of emergency services. For example, only 64% of Hispanic respondents reported convenient access to a health care provider specializing in MS, compared with 76% of White and 78% of Black respondents.

A significantly higher proportion of Hispanics also reported that they could not take time off from work when they were sick (25%) or to attend a doctor appointment (20%), compared with White (15% and 9%, respectively) and Black (18% and 12%) respondents. Meanwhile, a significantly higher proportion of Hispanics (35%) reported visiting the emergency department in the past year for MS-related issues, compared with White (19%) or Black (25%) respondents.

White respondents consistently had greater convenient access to dental offices, healthy foods, outpatient care, gyms, and parks and trails, compared with Black and Hispanic patients’ access. For example, 85% of White patients had convenient access to dental offices and 72% had access to outpatient care, compared with Black (74% and 65%) and Hispanic (78% and 52%) patients. Two-thirds of Hispanic respondents (67%) reported access to healthy foods and to gyms, parks, or trails, compared with more than three-quarters of both White and Black patients.

Other barriers to MS care

Both racial/ethnic and gender disparities emerged in how patients felt treated by their health care providers. Men were significantly more likely (70%) than women (65%) to say their health care provider listens to and understands them. A statistically significant higher proportion of men (71%) also said their clinician explained their MS test results to them, compared with women (62%), and only 28% of women, versus 37% of men, said their provider developed a long-term plan for them.

Anne Foelsch, the vice president of strategic partnerships at MyHealthTeam, who works with the authors, noted the large discrepancy that was seen particularly for Hispanic patients in terms of how they felt treated by their health care provider.

“Doctors might perceive that the relationship is the same with all of their patients when their patients have a very different perception of what that relationship is and whether they’re not being heard,” Ms. Foelsch said. “It’s important that clinicians take a little bit of time and learn a little bit more about a patient’s perspective and what it’s like when they have a chronic condition like MS and how it impacts their life, looking for those nuances that are different based on your ethnicity.”

Just over half of Hispanic patients (54%) said their provider explained their MS test results, compared with nearly two-thirds of White patients (65%) and 61% of Black patients. Hispanic patients were also less likely (55%) to say they felt their provider listens to and understands them than White (67%) or Black (65%) patients. Two-thirds of White respondents (67%) said their doctor recommended regular check-ups, compared with just over half of Black and Hispanic respondents (55%).

Other statistically significant disparities by race/ethnicity, where a higher proportion of White patients responded affirmatively than Black or Hispanic patients, included feeling treated with respect by their health care provider, feeling their provider is nonjudgmental, and saying their provider spends enough time with them, addresses their MS symptoms, and encourages shared decision-making.

“This study nicely documents and points out that despite our best intentions, we need to do much better as a community to help those with chronic and potentially disabling diseases like MS,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. “The racial, ethnic, and gender disparities only result in greater disability and societal costs by those who can least afford it. All therapies fail due to nonadherence, limited access, lack of insurance coverage, limited insurance coverage, high copays, long waits, cultural biases, and more.”

The researchers acknowledged that their survey respondents may not be representative of all patients with MS because the survey relied on those who chose to respond to the online survey.

The study authors were all employees of Publicis Health Media or MyHealthTeam. Dr. Gudesblatt reported no disclosures.

At CMSC 2023

Why Is There a Lack of Representation of Skin of Color in the COVID-19 Literature?

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a striking paucity of representations of patients with skin of color (SOC) in the dermatology literature. Was COVID-19 underdiagnosed in this patient population due to a lack of patient-centered resources and inadequate dermatology training; reduced access to care, resulting from social determinants of health and reduced skin-color concordance; or the absence of population-based prevalence studies?

Tan et al1 reviewed 51 articles describing skin findings secondary to COVID-19. Patients were stratified by country of origin, which yielded an increased prevalence of cutaneous manifestations among Americans and Europeans compared to Asians, but patients were not stratified by race.1 However, in one case series of 318 predominantly American patients, 89% were White and 0.7% were Black.2 This systematic review by Tan et al1 suggested that skin manifestations of COVID-19 were present in patients with SOC but less frequently than in White patients. However, case series are not a strong proxy for population-level prevalence.

More broadly, patients with SOC are underrepresented in Google image search results, as the medical resource websites (eg, DermNet [https://dermnetnz.org], MedicalNewsToday [www.medicalnewstoday.com], and Healthline [www.healthline.com]) are lacking these images.3 As a result, it is difficult for patients with SOC to recognize diseases presenting in darker skin types. This same tendency may exist for COVID-19 skin manifestations. A systematic review found that articles describing cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 almost exclusively presented images of lighter skin and completely omitted darker skin.4 If images of patients with SOC are absent from online resources, it is increasingly unlikely for these patients to recognize if their skin lesions are associated with COVID-19, which may result in a decrease in the number of patients with SOC presenting with skin lesions secondary to COVID-19, thereby influencing the representation of patients with SOC in case studies.

The lack of representation of SOC in online resources mirrors the paucity of images in dermatology textbooks. According to a search of 7170 images in major dermatology textbooks, most images depicted light or white skin (80.6%), followed by medium or brown skin in 15.5% of images and dark or black skin in only 3.9%.5 Physicians rely on online and print resources for making diagnoses; inadequate resources highlight a component of a larger issue: inadequate training of dermatologists in SOC. In a survey of American dermatologists and dermatology residents (N=262), 47% thought that their medical education had not adequately trained them on skin conditions in Black patients.6

A lack of adequate training for dermatologists may decrease the rate of correct diagnosis of skin lesions secondary to COVID-19 in patients with SOC. A lack of trust in the health care system and social determinants of health may hinder patients with SOC from seeking medical help. Dermatology is the second least diverse of medical specialties; only 3% of dermatologists are Black.7 This is impactful: First, because minority physicians are increasingly likely to provide care for patients of the same race or background, and second, because race-concordant physician visits are associated with greater patient-reported positive affect.7 A lack of availability of race-concordant physicians or physicians with perceived cultural competence may deter patients with SOC from seeking help, which may be further prevalent in dermatologic practice.

Barriers at all levels of social determinants of health hinder access to health care. Patients with SOC experience greater housing insecurity, increased reliance on public transportation, more issues with health literacy, and limited English-language fluency.8 Combined, these factors equate to decreased access to health care resources and subsequently a lack of inclusion in case studies.

COVID-19 infection disproportionately affects patients with SOC,8 but there is a clear lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 dermatology literature. It is imperative to investigate factors that may contribute to this inequity. Recognizing skin manifestations can play a role in diagnosing COVID-19; increased awareness of its presentation in darker skin types may help bridge existing racial inequities. It is vital that physicians receive adequate resources and training to be able to recognize cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in all skin types. Finally, it is important to recognize that the lack of representation of SOC in the COVID-19 literature represents a larger trend that exists in dermatologic research that warrants further investigation and advocacy for inclusivity.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2020.12.003

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dematol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:E113-E114. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.097

- Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, et al. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:593-595. doi:10.1111/bjd.19258

- Kamath P, Sundaram N, Morillo-Hernandez C, et al. Visual racism in internet searches and dermatology textbooks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1348-1349. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.072

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59,viii. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.044

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, et al. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:703-706. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa815

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

THE COMPARISON

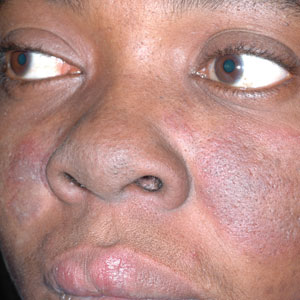

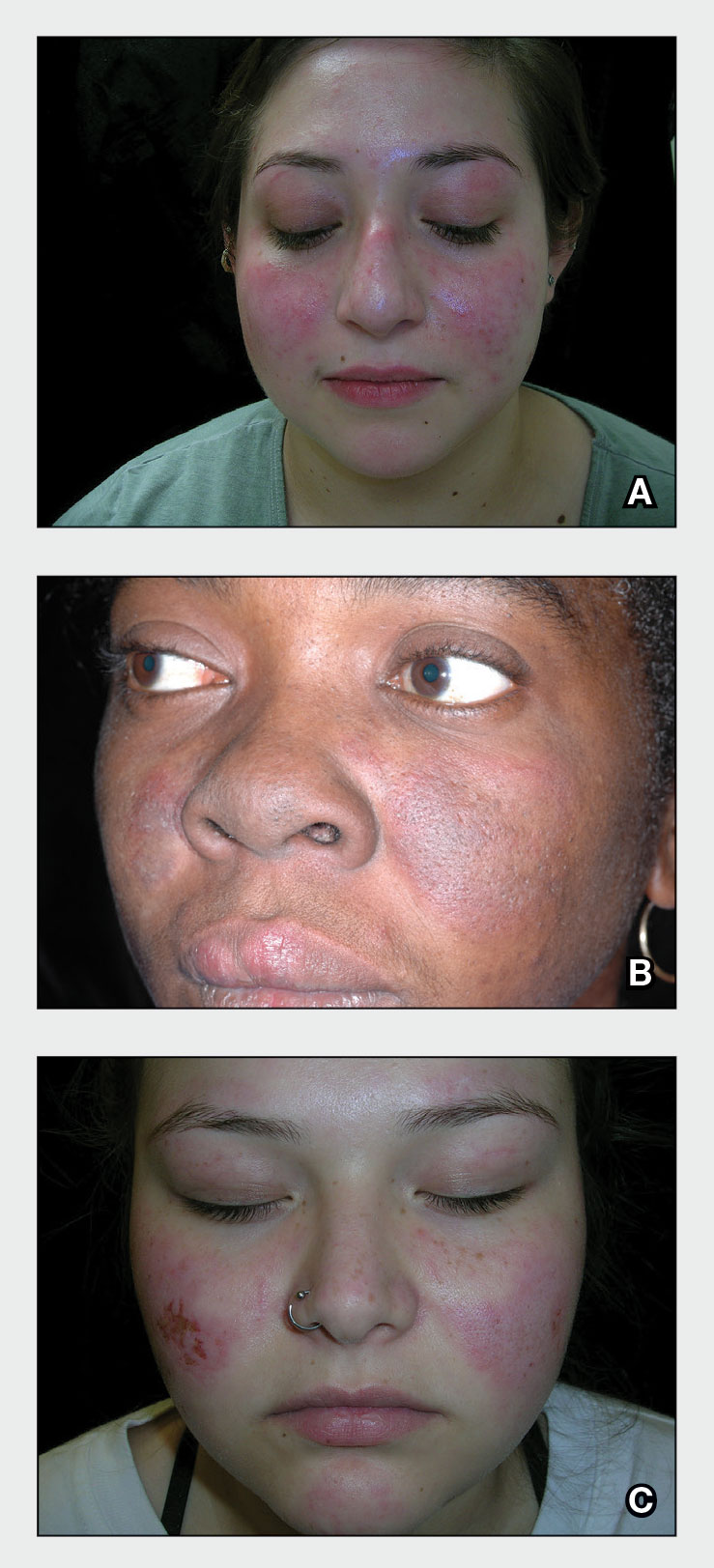

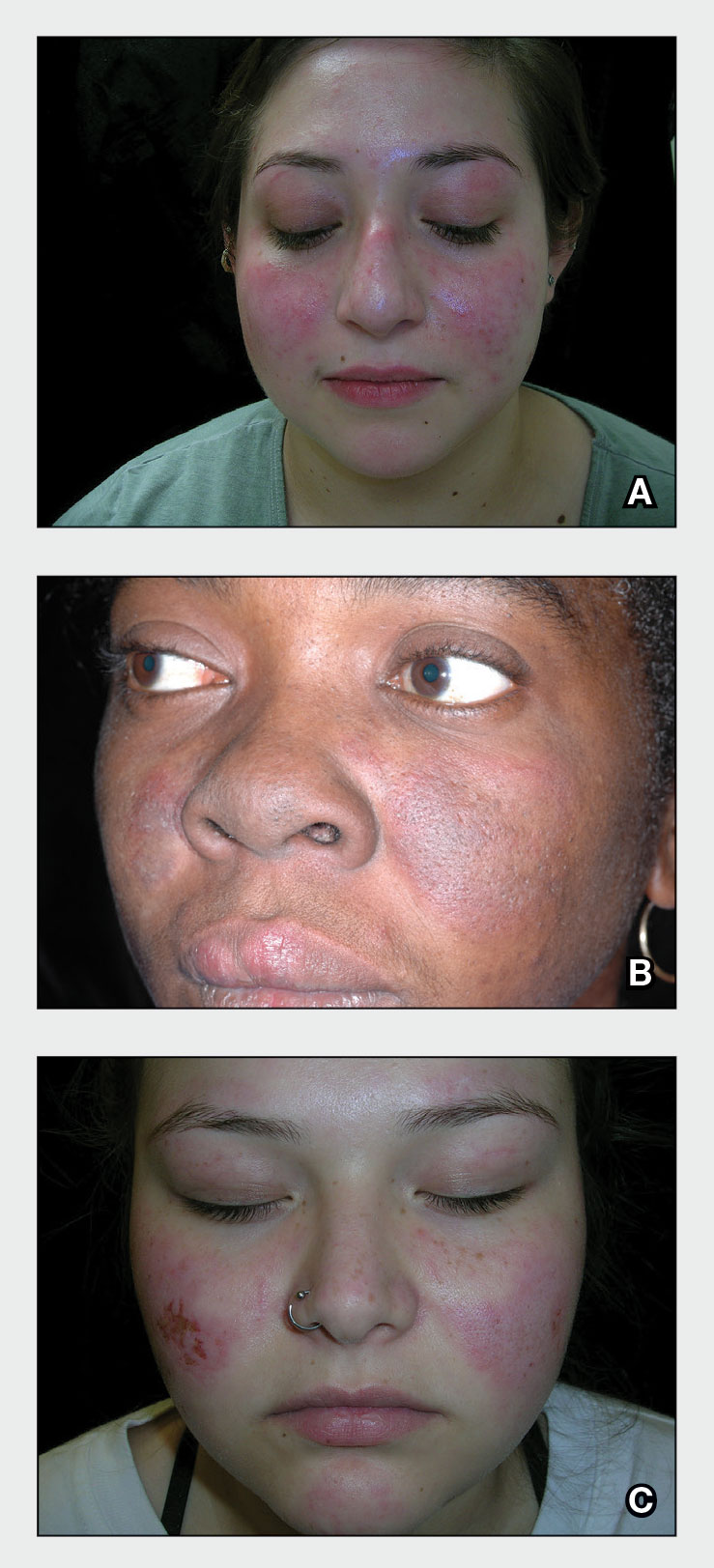

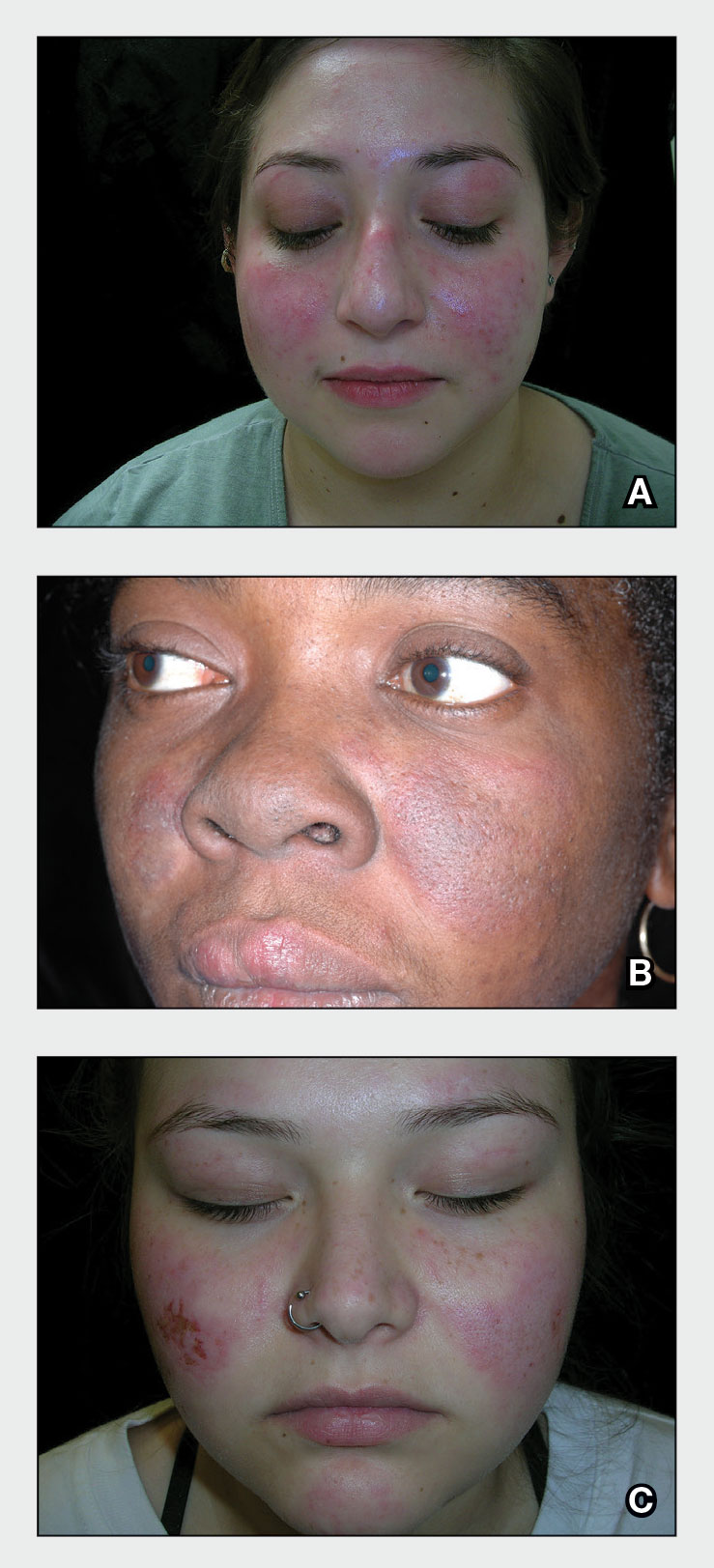

A A 23-year-old White woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds.

B A Black woman with malar erythema and hyperpigmentation from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The nasolabial folds are spared.

C A 19-year-old Latina woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose, chin, and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds. Cutaneous erosions are present on the right cheek as part of the lupus flare. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart, though it is not limited to these organs. Dermatologists and primary care physicians play a critical role in the early identification of SLE, particularly in those with skin of color, as the standardized mortality rate is 2.6-fold higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population.1 The clinical manifestations of SLE vary.

Epidemiology

A meta-analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registry network including 5417 patients revealed a prevalence of 72.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.2 The prevalence was higher in females than males and highest among females identifying as Black. White and Asian/Pacific Islander females had the lowest prevalence. The American Indian (indigenous)/Alaska Native–identifying population had the highest race-specific SLE estimates among both females and males compared to other racial/ethnic groups.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

The diagnosis of SLE is based on clinical and immunologic criteria from the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology.3,4 An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 or higher at least once is required for the diagnosis of SLE, as long as there is not another more likely diagnosis. If it is present, 22 additive weighted classification criteria are considered; each criterion is assigned points, ranging from 2 to 10. Patients with at least 1 clinical criterion and 10 or more points are classified as having SLE. If more than 1 of the criteria are met in a domain, then the one with the highest numerical value is counted.3,4 Aringer et al3,4 outline the criteria and numerical points to make the diagnosis of SLE. The mucocutaneous component of the SLE diagnostic criteria3,4 includes nonscarring alopecia, oral ulcers, subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus erythematosus,5 and acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, with acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus being the highest-weighted criterion in that domain. The other clinical domains are constitutional, hematologic, neuropsychiatric, serosal, musculoskeletal, renal, antiphosopholipid antibodies, complement proteins, and SLE-specific antibodies.3,4

The malar (“butterfly”) rash of SLE characteristically includes erythema that spares the nasolabial folds but affects the nasal bridge and cheeks.6 The rash occasionally may be pruritic and painful, lasting days to weeks. Photosensitivity occurs, resulting in rashes or even an overall worsening of SLE symptoms. In those with darker skin tones, erythema may appear violaceous or may not be as readily appreciated.6

Worth noting

• Patients with skin of color are at an increased risk for postinflammatory hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation (pigment alteration), hypertrophic scars, and keloids.7,8

• The mortality rate for those with SLE is high despite early recognition and treatment when compared to the general population.1,9

Health disparity highlight

Those at greatest risk for death from SLE in the United States are those of African descent, Hispanic individuals, men, and those with low socioeconomic status,9 which likely is primarily driven by social determinants of health instead of genetic patterns. Income level, educational attainment, insurance status, and environmental factors10 have far-reaching effects, negatively impacting quality of life and even mortality.

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus. 2016;25:727-734.

- Izmirly PM, Parton H, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: estimates from a meta-analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries [published online April 23, 2021]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:991-996. doi:10.1002/art.41632

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi:10.1002/art.40930

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1151-1159.

- Heath CR, Usatine RP. Discoid lupus. Cutis. 2022;109:172-173.

- Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, eds. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2008.

- Nozile W, Adgerson CH, Cohen GF. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:343-349.

- Cardinali F, Kovacs D, Picardo M. Mechanisms underlying postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: lessons for solar. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139(suppl 4):S148-S152.

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, et al. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:1043-1053. doi:10.1080/17446 66X.2018.1538789

- Carter EE, Barr SG, Clarke AE. The global burden of SLE: prevalence, health disparities and socioeconomic impact. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12:605-620. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.137

THE COMPARISON

A A 23-year-old White woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds.

B A Black woman with malar erythema and hyperpigmentation from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The nasolabial folds are spared.

C A 19-year-old Latina woman with malar erythema from acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The erythema also can be seen on the nose, chin, and eyelids but spares the nasolabial folds. Cutaneous erosions are present on the right cheek as part of the lupus flare. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the kidneys, lungs, brain, and heart, though it is not limited to these organs. Dermatologists and primary care physicians play a critical role in the early identification of SLE, particularly in those with skin of color, as the standardized mortality rate is 2.6-fold higher in patients with SLE compared to the general population.1 The clinical manifestations of SLE vary.

Epidemiology

A meta-analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registry network including 5417 patients revealed a prevalence of 72.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.2 The prevalence was higher in females than males and highest among females identifying as Black. White and Asian/Pacific Islander females had the lowest prevalence. The American Indian (indigenous)/Alaska Native–identifying population had the highest race-specific SLE estimates among both females and males compared to other racial/ethnic groups.2

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones