User login

De-pathologizing gender identity: Psychiatry’s role

Treating patients who are transgender or gender diverse (TGGD) requires an understanding of the social and psychological factors that have a unique impact on this population. As clinicians, it is our responsibility to understand the social, cultural, and political issues our patients face, both historically and currently. In this article, we provide information about the nature of gender and gender identity as separate from biological sex and informed by a person’s perception of self as male, female, nonbinary, or other variation.

Psychiatrists must be aware of how individuals who are TGGD have been perceived, classified, and treated by the medical profession, as this history is often a source of mistrust and a barrier to treatment for patients who need psychiatric care. This includes awareness of the “gatekeeping” role that persists in medical institutions today: applying strict eligibility criteria to determine the “fitness” of individuals who are transgender to pursue medical transition, as compared to the informed-consent model that is widely applied to other medical interventions. Our review of minority stress theory, as applicable to this patient population, provides a context and framework for empathic approaches to care for patients who are TGGD. Recognizing barriers to care and ways in which we can create a supportive environment for treatment will allow for tailored approaches that better fit the unique needs of this patient population.

The gender binary

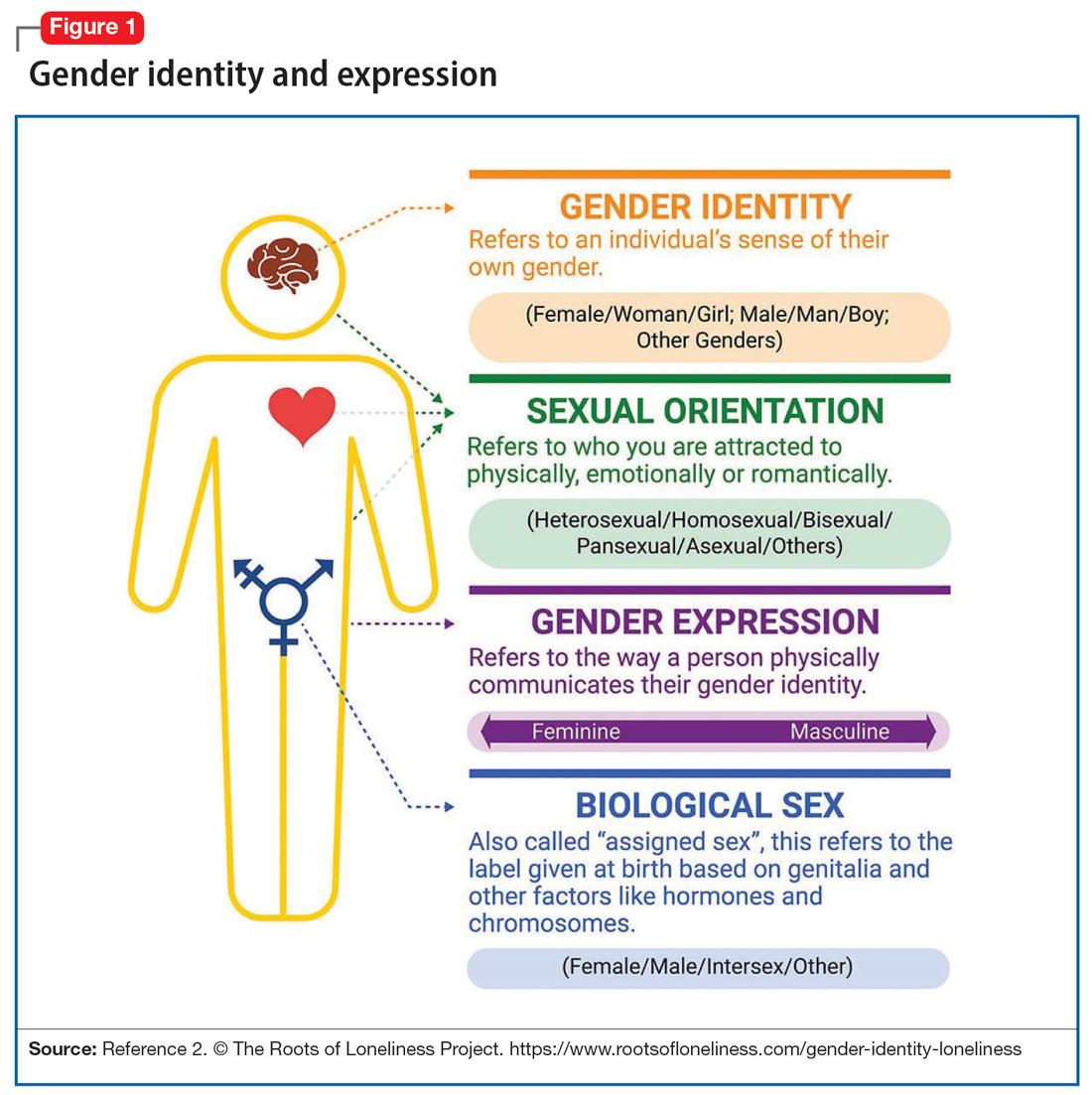

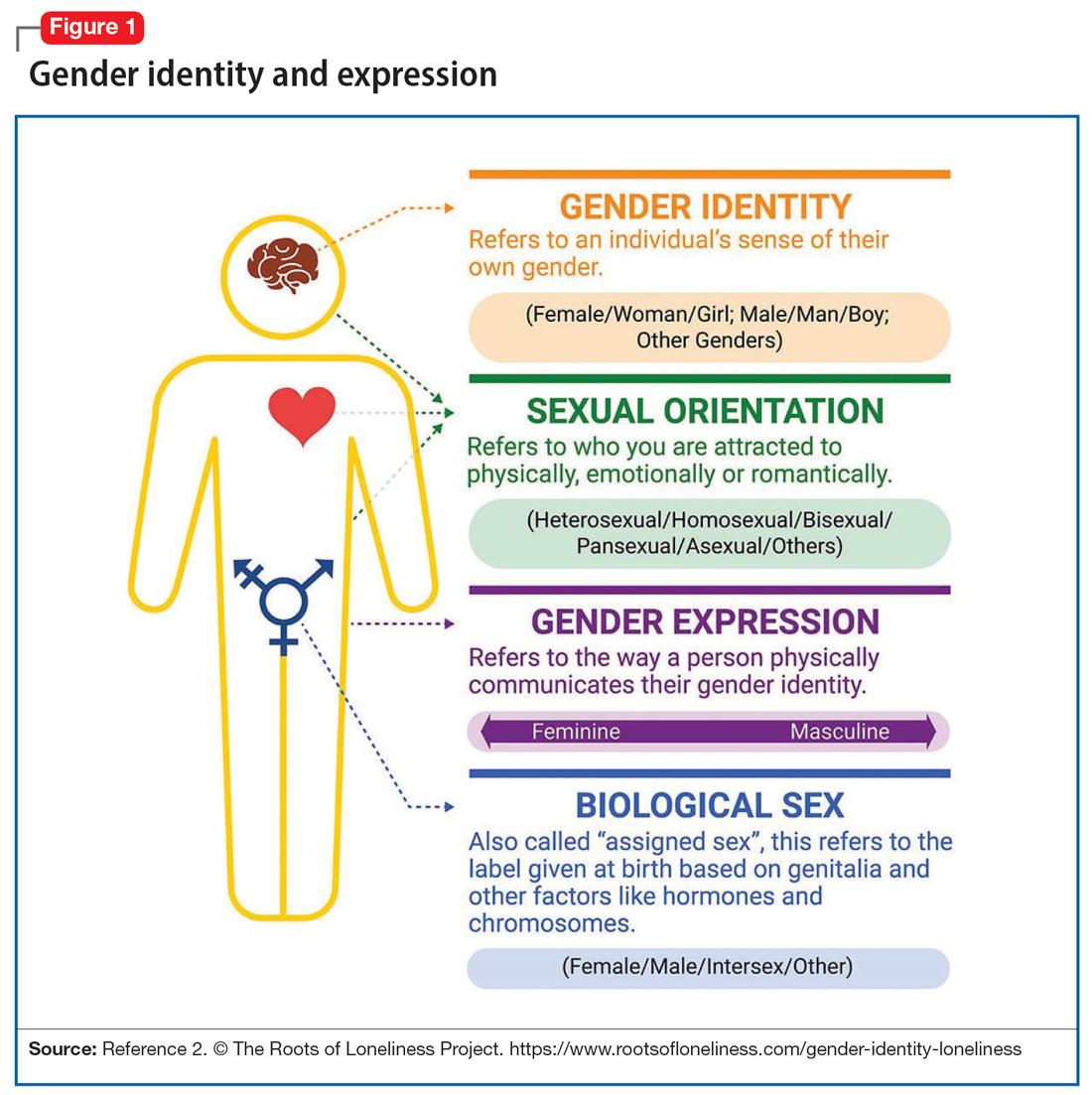

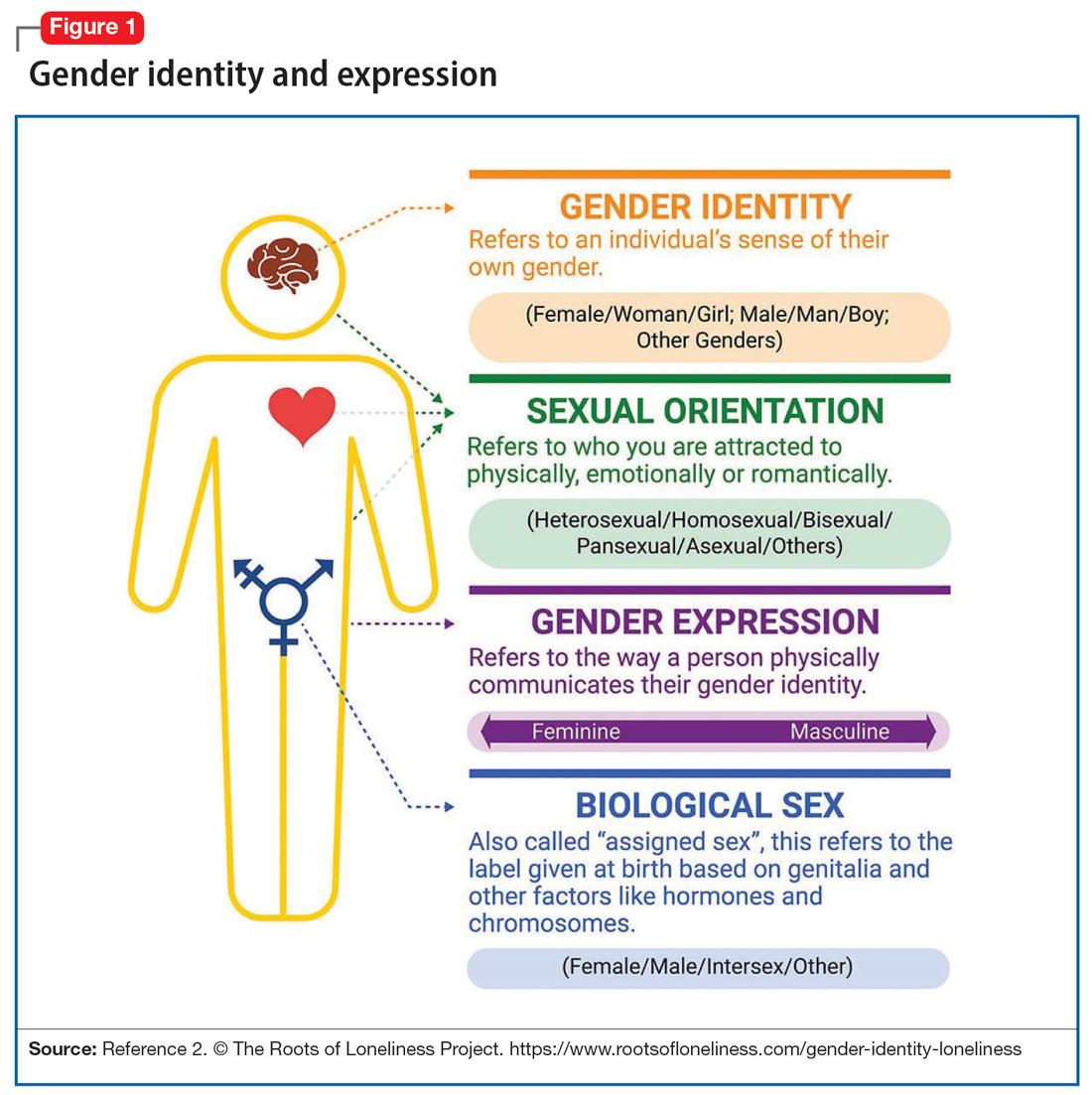

In Western societies, gender has often been viewed as “binary,” oppositional, and directly correlated with physical sex or presumed anatomy.1 The theory of gender essentialism insists that sex and gender are indistinguishable from one another and provide 2 “natural” and distinct categories: women and men. The “gender/sex” binary refers to the belief that individuals born with 2 X chromosomes will inherently develop into and fulfill the social roles of women, and those born with an X and a Y chromosome will develop into and fulfill the social roles of men.1 In this context, “sex” refers to biological characteristics of individuals, including combinations of sex chromosomes, anatomy, and the development of sex characteristics during puberty. The term “gender” refers to the social, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man, woman, both, or neither, and “gender identity” refers to one’s internal, individual sense of self and experience of gender (Figure 12). Many Western cultures are now facing destabilization of the gender/sex binary in social, political, and interpersonal contexts.1 This is perhaps most clearly seen in the battle for self-determination and protection by laws affecting individuals who are transgender as well as the determination of other groups to maintain traditional sex and gender roles, often through political action. Historically, individuals who are TGGD have been present in a variety of cultures. For example, most Native American cultures have revered other-gendered individuals, more recently referred to as “two-spirited.” Similarly, the Bugis people of South Sulawesi, Indonesia, recognize 5 genders that exist on a nonbinary spectrum.3

Despite its prevalence in Western society, scientific evidence for the gender/sex binary is lacking. The gender similarities hypothesis states that males and females are similar in most, but not all, psychological variables and is supported by multiple meta-analyses examining psychological gender differences.4 In a 2005 review of 46 meta-analyses of gender-differences, studied through behavior analysis, effect sizes for gender differences were trivial or small in almost 75% of examined variables.5 Analyzing for internal consistency among studies showing large gender/sex differences, Joel et al6 found that, on measures of personality traits, attitudes, interests, and behaviors were rarely homogenous in the brains of males or females. In fact, <1% of study participants showed only masculine or feminine traits, whereas 55% showed a combination, or mosaic, of these traits.6 These findings were supported by further research in behavioral neuroendocrinology that demonstrated a lack of hormonal evidence for 2 distinct sexes. Both estrogen (the “female” hormone) and testosterone (the “male” hormone) are produced by both biological males and females. Further, levels of estradiol do not significantly differ between males and females, and, in fact, in nonpregnant females, estradiol levels are more similar to those of males than to those of pregnant females.1 In the last decade, imaging studies of the human brain have shown that brain structure and connectivity in individuals who are transgender are more similar to those of their experienced gender than of their natal sex.7 In social analyses of intersex individuals (individuals born with ambiguous physical sex characteristics), surgical assignment into the binary gender system did not improve—and often worsened—feelings of isolation and shame.1

The National Institutes of Health defines gender as “socially constructed and enacted roles and behaviors which occur in a historical and cultural context and vary across societies and time.”8 The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a similar definition, and the evidence to support this exists in social-role theory, social-identity theory, and the stereotype-content model. However, despite evidence disputing a gender/sex binary, this method of classifying individuals into a dyad persists in many areas of modern culture, from gender-specific physical spaces (bathrooms, classrooms, store brands), language (pronouns), and laws. This desire for categorization helps fulfill social and psychological needs of groups and individuals by providing group identities and giving structure to the complexity of modern-day life. Identity and group membership provide a sense of belonging, source of self-esteem, and avoidance of ambiguity. Binary gender stereotypes provide expectations that allow anticipation and prediction of our social environments.9 However, the harm of perpetuating the false gender/sex binary is well documented and includes social and economic penalties, extreme violence, and even death. The field of medicine has not been immune from practices that implicitly endorse the gender/sex connection, as seen in the erroneous use of gender in biomedical writings at the highest levels and evidenced in research examining “gender” differences in disease incidence.

Gender diversity as a pathology

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has been a source of pathologizing gender diversity since the 1960s, with the introduction of “transsexualism” in DSM-II10 and “gender identity disorder of childhood” in DSM-III.11 These diagnoses were listed under the headings of “sexual deviations” and “psychosexual disorders” in the respective DSM editions. This illustrates how gender diversity was viewed as a mental illness/defect. As the DSM developed through various revisions, so have these diagnoses. DSM-IV used the diagnosis “gender identity disorder.”12 Psychiatry has evolved away from this line of thinking by focusing on the distress from biological sex characteristics that are “incongruent” with an individual’s gender identity, leading to the development of the gender dysphoria diagnosis.13 While this has been a positive step in psychiatry’s efforts to de-pathologize individuals who are gender-diverse, it raises the question: should such diagnoses be included in the DSM at all?

The gender dysphoria diagnosis continues to be needed by many individuals who are TGGD in order to access gender-affirming health care services. Mental health professionals are placed in a gatekeeping role by the expectation that they provide letters of “support” to indicate an individual is of sound mind and consistent gender identity to have services covered by insurance providers. In this way, the insurance industry and the field of medicine continue to believe that individuals who are TGGD need psychiatric permission and/or counsel regarding their gender identity. This can place psychiatry in a role of controlling access to necessary care while also creating a possible distrust in our ability to provide care to patients who are gender-diverse. This is particularly problematic given the high rates of depression, anxiety, trauma, and substance use within these communities.14 In the WHO’s ICD-11, gender dysphoria was changed to gender incongruence and is contained in the category of “Conditions related to sexual health.”15 This indicates continued evolution of how medicine views individuals who are TGGD, and offers hope that psychiatry and the DSM will follow suit.

Continue to: Minority stress theory

Minority stress theory

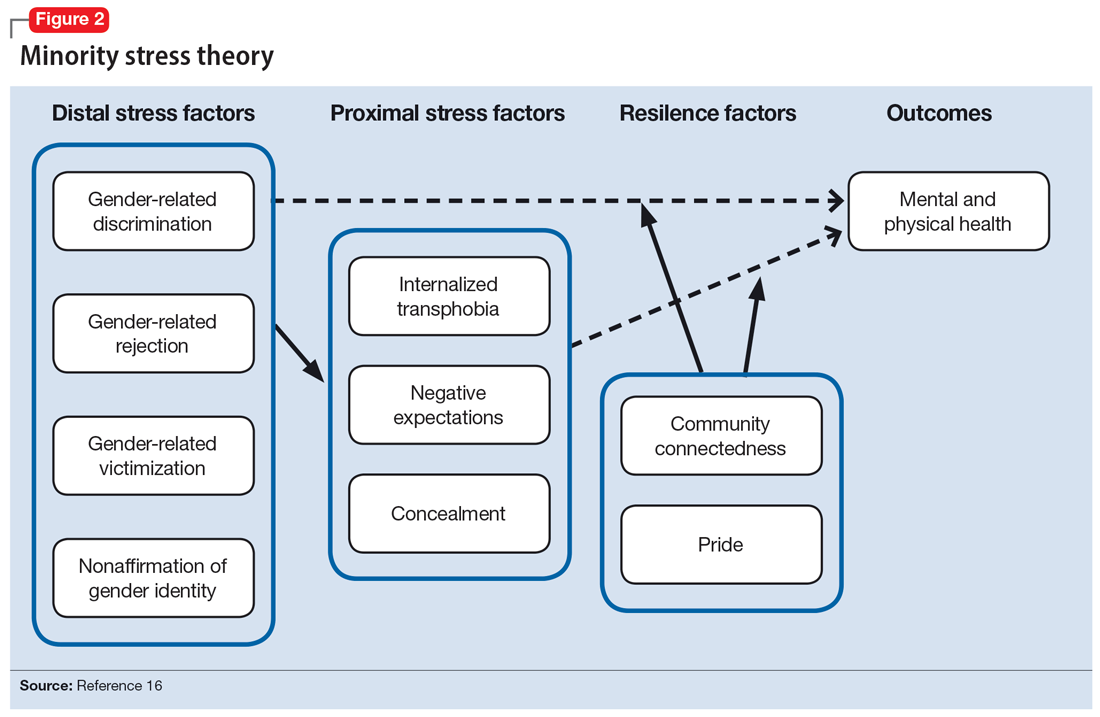

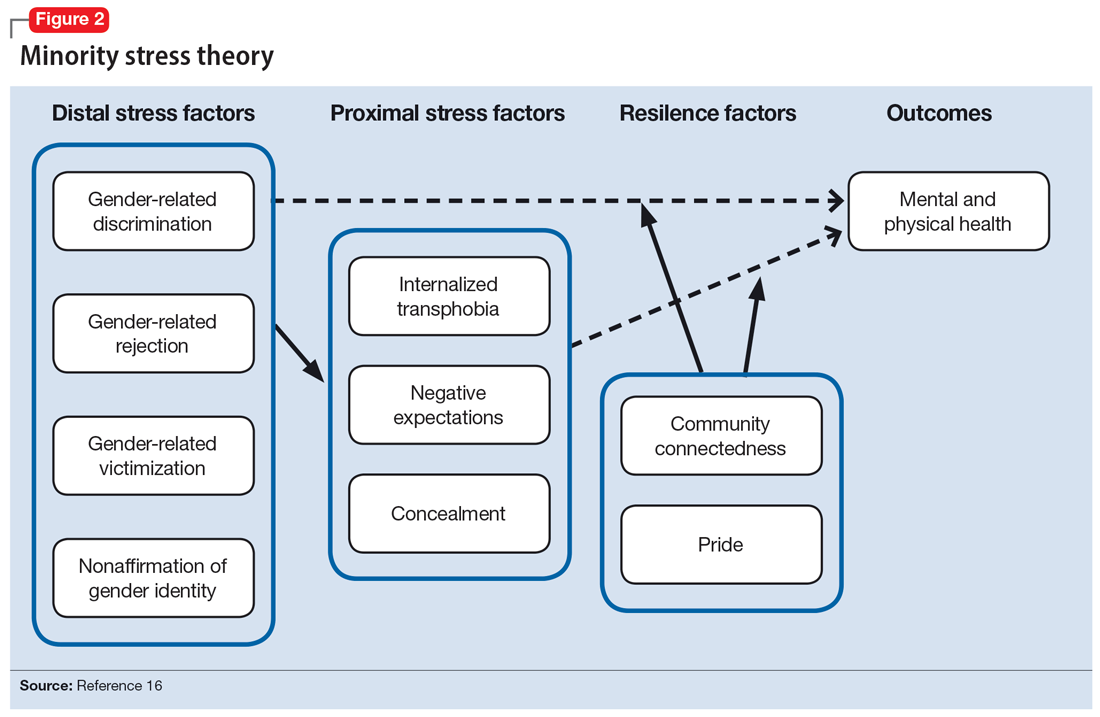

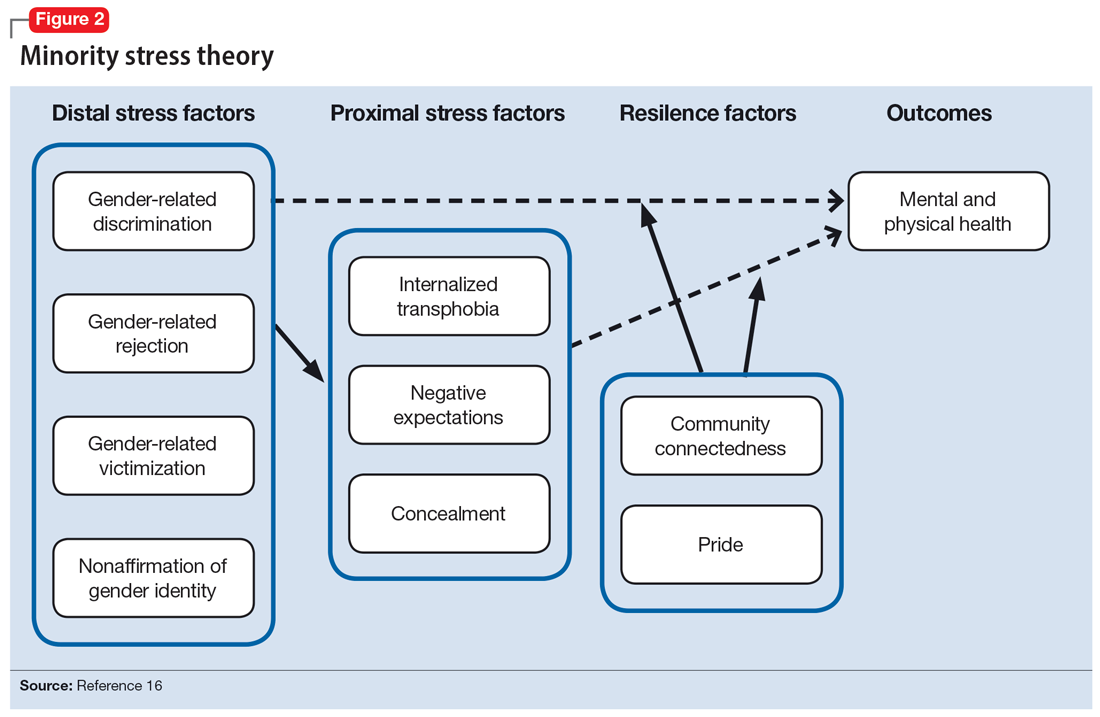

Ilan Meyer’s minority stress theory explores how cultural and social factors impact mental health functioning (Figure 216). Minority stress theory, which was originally developed for what at the time was described as the lesbian, gay, and bisexual communities, purports that the higher prevalence of mental health disorders among such individuals is likely due to social stigma, discrimination, and stressors associated with minority status. More recently, minority stress theory has been expanded to provide framework for individuals who are TGGD. Hendricks et al17 explain how distal, proximal, and resilience factors contribute to mental health outcomes among these individuals. Distal factors, such as gender-related discrimination, harassment, violence, and rejection, explain how systemic, cultural, and environmental events lead to overt stress. Proximal factors consist of an individual’s expectation and anticipation of negative and stressful events and the internalization of negative attitudes and prejudice (ie, internalized transphobia). Resilience factors consist of community connectedness and within-group identification and can help mediate the negative effects of distal and proximal factors.

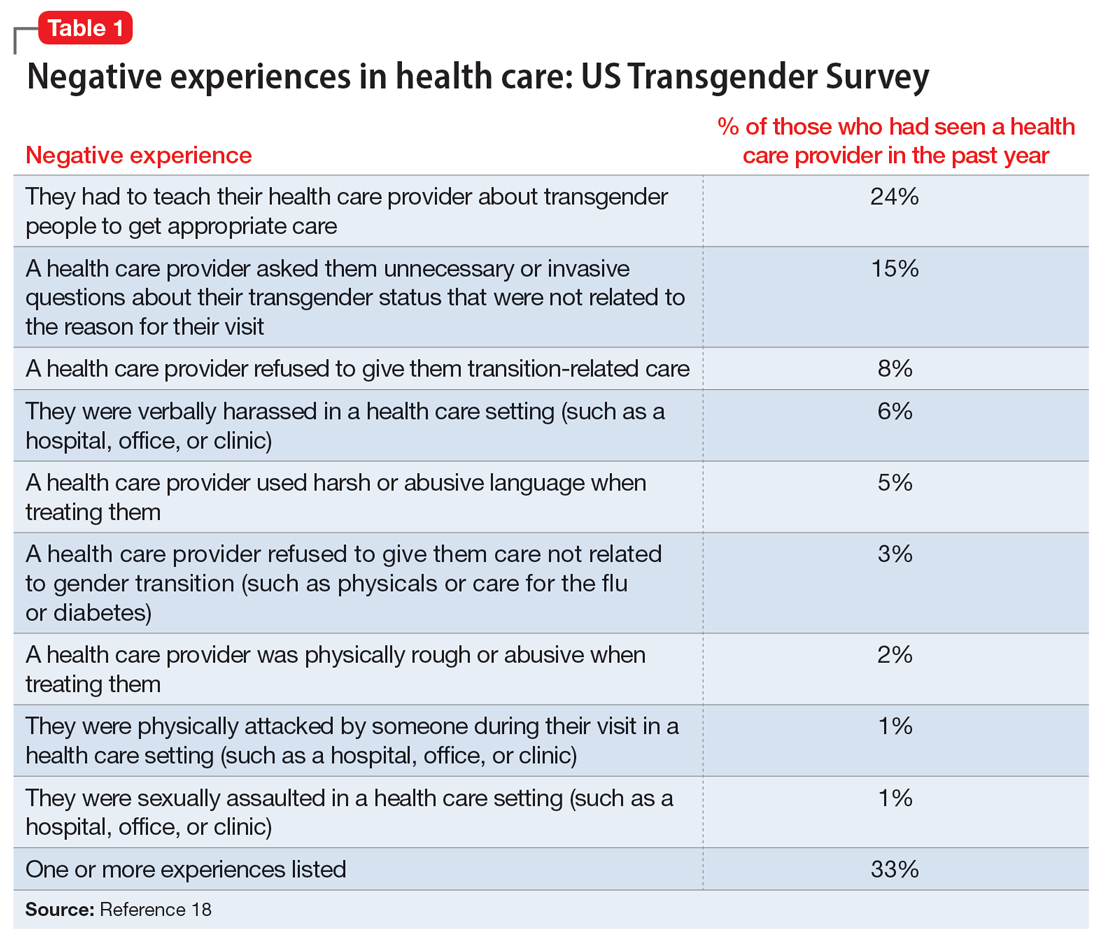

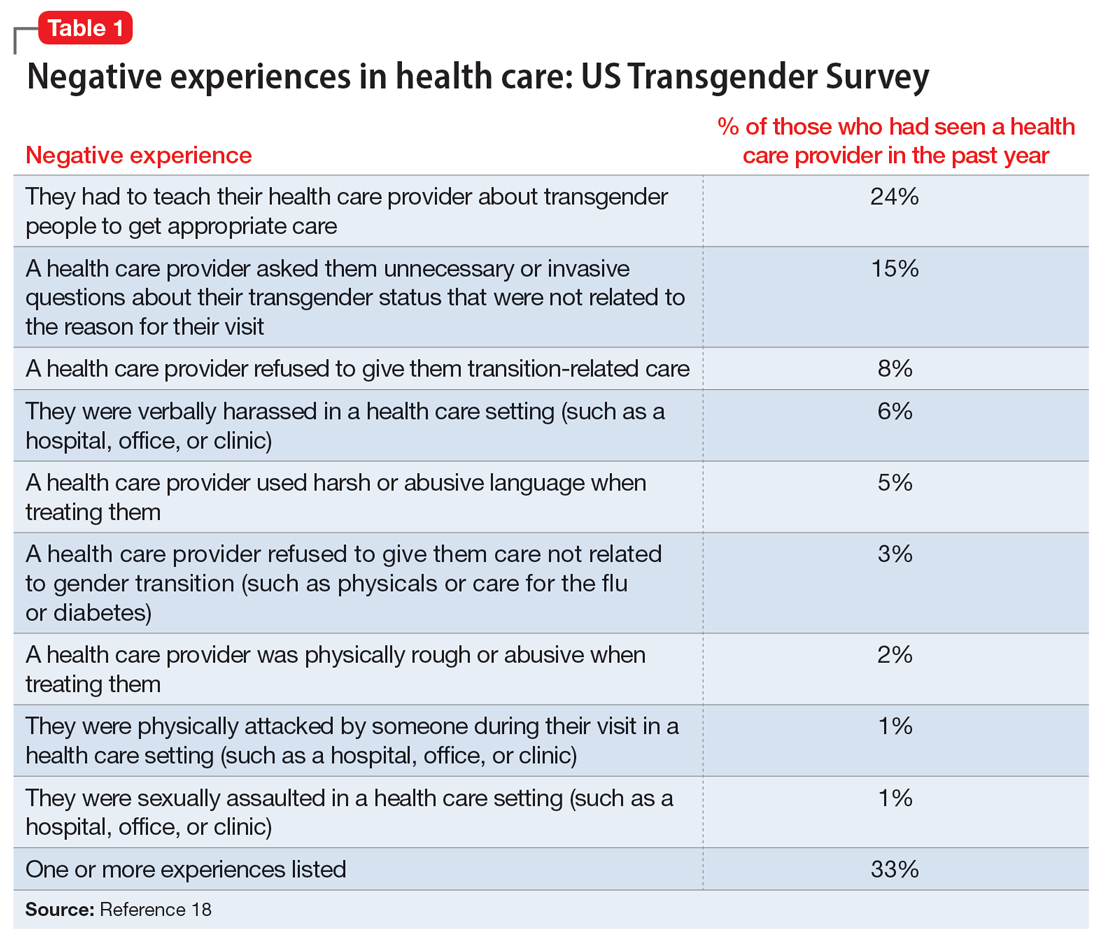

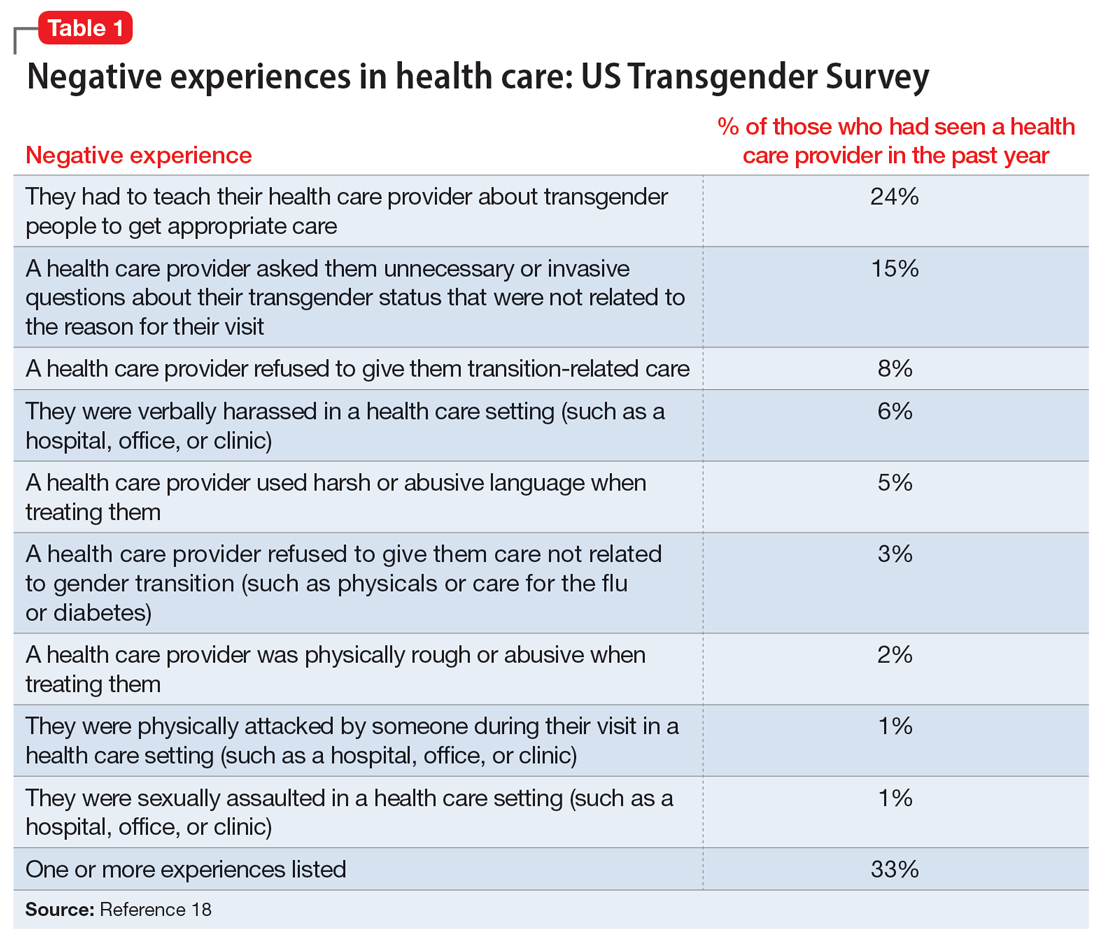

As clinicians, understanding our patients’ experiences and expectations can help us better engage with them and create an environment of safety and healing. Minority stress theory framework suggests that patients may start treatment with distrust or suspicion in light of previous negative experiences. They may also be likely to expect clinicians to be judgmental or to lack understanding of them. The 2015 US Transgender Survey found that 33% of individuals who are TGGD who sought medical treatment in the past year had at least 1 negative experience related to their gender identity (Table 118). Twenty-four percent reported having to educate their clinician about people who are TGGD, while 15% reported the health care professional asked invasive or unnecessary questions about their gender status that were unrelated to their visit. While psychiatry is often distinct from the larger medical field, it is important to understand the negative encounters individuals who are TGGD have likely experienced in medicine, and how those events may skew their feelings about psychiatric treatment. This is especially salient given the higher prevalence of various psychiatric disorders among individuals who are TGGD.18

According to the US Transgender Survey, 39% of participants were currently experiencing serious psychological distress, which is nearly 8 times the rate in the US population (5%).18 When extrapolated, this data indicates that we in psychiatry are likely to work with individuals who identify as TGGD, regardless of our expertise. Additionally, research indicates that having access to gender-affirming care—such as hormone replacement therapy, gender-affirming surgery, voice therapy, and other treatments—greatly improves mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and suicidality among individuals who are TGGD.19,20 It is in this way we in psychiatry must do more than just care for our patients by becoming advocates for them to receive the care they need and deserve. While at times we may want to stay out of politics and other public discourse, it is becoming increasingly necessary as health care is entrenched in politics.

Clinical applicability

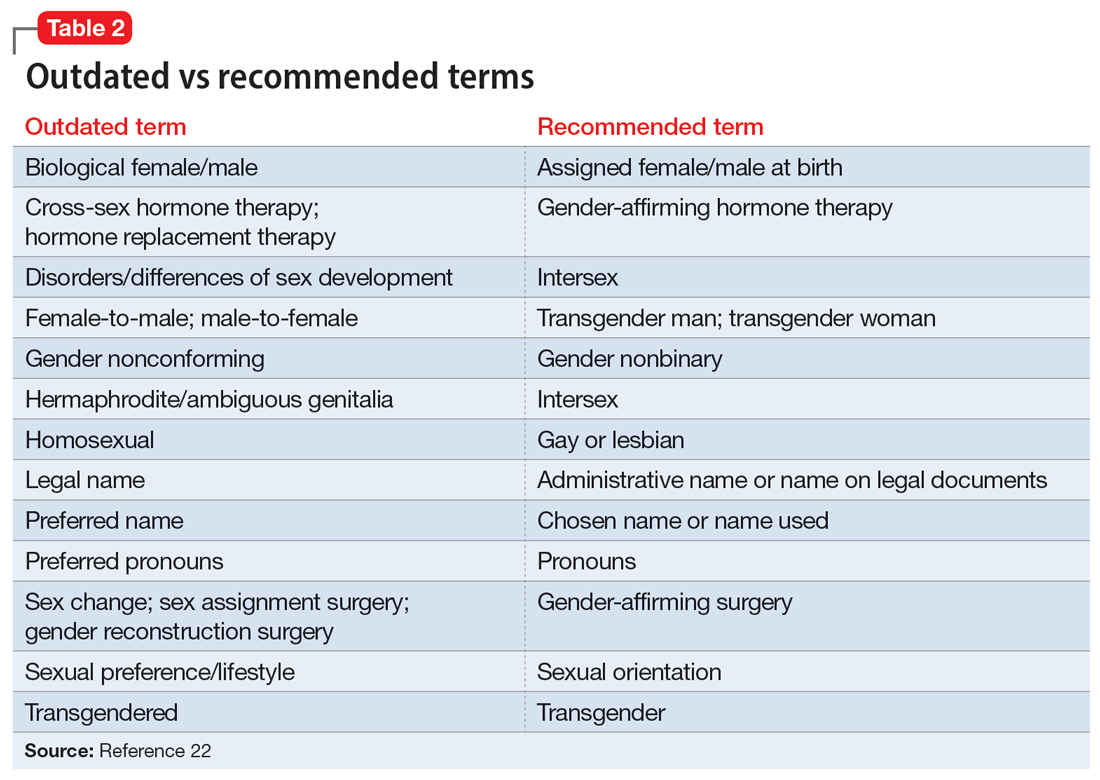

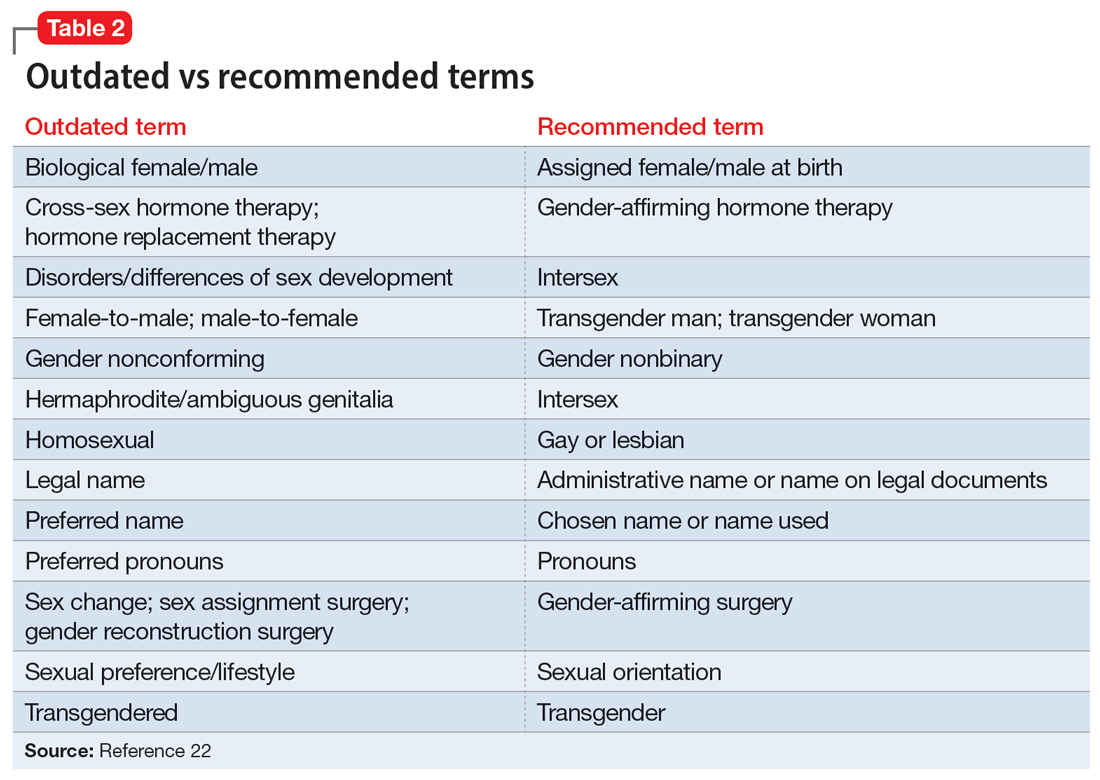

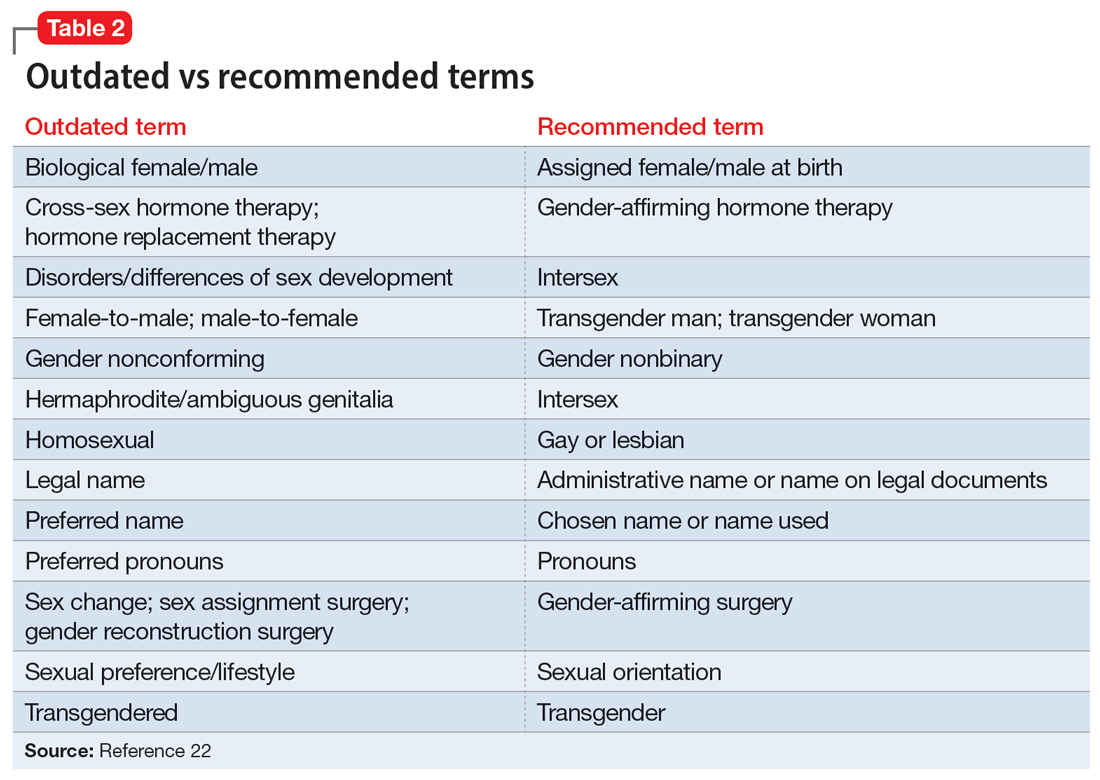

Because individuals who are TGGD experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance use, and other psychiatric disorders,14 it is increasingly likely that many clinicians will be presented with opportunities to treat such individuals. Despite high rates of psychiatric disorders, individuals who are TGGD often avoid treatment due to concerns about being pathologized, stereotyped, and/or encountering professionals who lack the knowledge to treat them as they are.21 Several studies recommend clinicians better equip themselves to appropriately provide services to individuals who are TGGD.21 Some advise seeking education to understand the unique needs of these patients and to help stay current with appropriate terminology and language (Table 222). This also implies not relying on patients to educate clinicians in understanding their specific needs and experiences.

Making assumptions about a patient’s identity is one of the most commonly reported issues by individuals who are TGGD. Therefore, it is critical to avoid making assumptions about patients based on binary stereotypes.23,24 We can circumvent these mistakes by asking every patient for their name and pronouns, and introducing ourselves with our pronouns. This illustrates an openness and understanding of the importance of identity and language, and makes it common practice from the outset. Integrating the use of gender-neutral language into paperwork, intake forms, charting, and conversation will also help avoid the pitfalls of misgendering and making false assumptions. This will also allow for support staff, medical assistants, and others to use correct language with patients. Having a patient’s used name and pronouns visible for everyone who works with the patient is necessary to effectively meet the patient’s needs. Additionally, understanding that the range of experiences and needs for individuals who are TGGD is heterogeneous can help reduce assumptions and ensure we are asking for needed information. It is also important to ask for only relevant information needed to provide treatment.

Continue to: Resources are widely available...

Resources are widely available to aid in the care of individuals who are TGGD. In 2022, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health released new guidelines—Standards of Care 8—for working with individuals who are TGGD.25 While these standards include a section dedicated to mental health, they also provide guidelines on education, assessments, specific demographic groups, hormone therapy, primary care, and sexual health. Additionally, while we may not want the role of gatekeeping for individuals to receive gender-affirming care, we work within a health care and insurance system that continues to require psychiatric assessment for such surgeries. In this role, we must do our part to educate ourselves in how to best provide these assessments and letters of support to help patients receive appropriate and life-saving care.

Finally, in order to provide a more comfortable and affirming space for individuals who are TGGD, develop ways to self-assess and monitor the policies, procedures, and language used within your practice, clinic, or institution. Monitoring the language used in charting to ensure consistency with the individual’s gender identity is important for our own understanding of the patient, and for patients to feel seen. This is especially true given patients’ access to medical records under the Cures Act. Moreover, it is essential to be cognizant of how you present clients to others in consultation or care coordination to ensure the patient is identified correctly and consistently by clinicians and staff.

Bottom Line

Understanding the social, cultural, and medical discrimination faced by patients who are transgender or gender diverse can make us better suited to engage and treat these individuals in an affirming and supportive way.

Related Resources

- World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care—8th edition. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- The Fenway Institute: National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. https://fenwayhealth.org/the-fenway-institute/education/the-national-lgbtia-health-education-center/

1. Morgenroth T, Ryan MK. The effects of gender trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16(6):1113-1142. doi:10.1177/1745691620902442

2. The Roots of Loneliness Project. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.rootsofloneliness.com/gender-identity-loneliness

3. Davies SG. Challenging Gender Norms: Five Genders Among Bugis in Indonesia. Thomson Wadsworth; 2007.

4. Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol. 2005;60(6):581-592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

5. Joel D. Beyond the binary: rethinking sex and the brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;122:165-175. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.22.018

6. Joel D, Berman Z, Tavor I, et al. Sex beyond the genitalia: the human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(50):15468-15473. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509654112

7. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. A universally accepted definition of gender will positively impact societal understanding, acceptance, and appropriateness of health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2235-2243. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.031

8. Office of Research on Women’s Health. Sex & Gender. National Institutes of Health. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender

9. Morgenroth T, Sendén MG, Lindqvist A, et al. Defending the sex/gender binary: the role of gender identification and need for closure. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021;12(5):731-740.

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1968.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

14. Wanta JW, Niforatos JD, Durbak E, et al. Mental health diagnoses among transgender patients in the clinical setting: an all-payer electronic health record study. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):313-315.

15. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases. 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

16. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

17. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Profess Psychol: Res Pract. 2012;43(5):460-467. doi:10.1037/a0029597

18. James SE, Herman J, Keisling M, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

19. Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):611-618. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952

20. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

21. Snow A, Cerel J, Loeffler DN, et al. Barriers to mental health care for transgender and gender-nonconforming adults: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Work. 2019;44(3):149-155. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlz016

22. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org

23. Baldwin A, Dodge B, Schick VR, et al. Transgender and genderqueer individuals’ experiences with health care providers: what’s working, what’s not, and where do we go from here? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(4):1300-1318. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0097

24. Kcomt L, Gorey KM, Barrett BJ, et al. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: a call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM-Popul Health. 2020;11:100608. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100608

25. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259.

Treating patients who are transgender or gender diverse (TGGD) requires an understanding of the social and psychological factors that have a unique impact on this population. As clinicians, it is our responsibility to understand the social, cultural, and political issues our patients face, both historically and currently. In this article, we provide information about the nature of gender and gender identity as separate from biological sex and informed by a person’s perception of self as male, female, nonbinary, or other variation.

Psychiatrists must be aware of how individuals who are TGGD have been perceived, classified, and treated by the medical profession, as this history is often a source of mistrust and a barrier to treatment for patients who need psychiatric care. This includes awareness of the “gatekeeping” role that persists in medical institutions today: applying strict eligibility criteria to determine the “fitness” of individuals who are transgender to pursue medical transition, as compared to the informed-consent model that is widely applied to other medical interventions. Our review of minority stress theory, as applicable to this patient population, provides a context and framework for empathic approaches to care for patients who are TGGD. Recognizing barriers to care and ways in which we can create a supportive environment for treatment will allow for tailored approaches that better fit the unique needs of this patient population.

The gender binary

In Western societies, gender has often been viewed as “binary,” oppositional, and directly correlated with physical sex or presumed anatomy.1 The theory of gender essentialism insists that sex and gender are indistinguishable from one another and provide 2 “natural” and distinct categories: women and men. The “gender/sex” binary refers to the belief that individuals born with 2 X chromosomes will inherently develop into and fulfill the social roles of women, and those born with an X and a Y chromosome will develop into and fulfill the social roles of men.1 In this context, “sex” refers to biological characteristics of individuals, including combinations of sex chromosomes, anatomy, and the development of sex characteristics during puberty. The term “gender” refers to the social, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man, woman, both, or neither, and “gender identity” refers to one’s internal, individual sense of self and experience of gender (Figure 12). Many Western cultures are now facing destabilization of the gender/sex binary in social, political, and interpersonal contexts.1 This is perhaps most clearly seen in the battle for self-determination and protection by laws affecting individuals who are transgender as well as the determination of other groups to maintain traditional sex and gender roles, often through political action. Historically, individuals who are TGGD have been present in a variety of cultures. For example, most Native American cultures have revered other-gendered individuals, more recently referred to as “two-spirited.” Similarly, the Bugis people of South Sulawesi, Indonesia, recognize 5 genders that exist on a nonbinary spectrum.3

Despite its prevalence in Western society, scientific evidence for the gender/sex binary is lacking. The gender similarities hypothesis states that males and females are similar in most, but not all, psychological variables and is supported by multiple meta-analyses examining psychological gender differences.4 In a 2005 review of 46 meta-analyses of gender-differences, studied through behavior analysis, effect sizes for gender differences were trivial or small in almost 75% of examined variables.5 Analyzing for internal consistency among studies showing large gender/sex differences, Joel et al6 found that, on measures of personality traits, attitudes, interests, and behaviors were rarely homogenous in the brains of males or females. In fact, <1% of study participants showed only masculine or feminine traits, whereas 55% showed a combination, or mosaic, of these traits.6 These findings were supported by further research in behavioral neuroendocrinology that demonstrated a lack of hormonal evidence for 2 distinct sexes. Both estrogen (the “female” hormone) and testosterone (the “male” hormone) are produced by both biological males and females. Further, levels of estradiol do not significantly differ between males and females, and, in fact, in nonpregnant females, estradiol levels are more similar to those of males than to those of pregnant females.1 In the last decade, imaging studies of the human brain have shown that brain structure and connectivity in individuals who are transgender are more similar to those of their experienced gender than of their natal sex.7 In social analyses of intersex individuals (individuals born with ambiguous physical sex characteristics), surgical assignment into the binary gender system did not improve—and often worsened—feelings of isolation and shame.1

The National Institutes of Health defines gender as “socially constructed and enacted roles and behaviors which occur in a historical and cultural context and vary across societies and time.”8 The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a similar definition, and the evidence to support this exists in social-role theory, social-identity theory, and the stereotype-content model. However, despite evidence disputing a gender/sex binary, this method of classifying individuals into a dyad persists in many areas of modern culture, from gender-specific physical spaces (bathrooms, classrooms, store brands), language (pronouns), and laws. This desire for categorization helps fulfill social and psychological needs of groups and individuals by providing group identities and giving structure to the complexity of modern-day life. Identity and group membership provide a sense of belonging, source of self-esteem, and avoidance of ambiguity. Binary gender stereotypes provide expectations that allow anticipation and prediction of our social environments.9 However, the harm of perpetuating the false gender/sex binary is well documented and includes social and economic penalties, extreme violence, and even death. The field of medicine has not been immune from practices that implicitly endorse the gender/sex connection, as seen in the erroneous use of gender in biomedical writings at the highest levels and evidenced in research examining “gender” differences in disease incidence.

Gender diversity as a pathology

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has been a source of pathologizing gender diversity since the 1960s, with the introduction of “transsexualism” in DSM-II10 and “gender identity disorder of childhood” in DSM-III.11 These diagnoses were listed under the headings of “sexual deviations” and “psychosexual disorders” in the respective DSM editions. This illustrates how gender diversity was viewed as a mental illness/defect. As the DSM developed through various revisions, so have these diagnoses. DSM-IV used the diagnosis “gender identity disorder.”12 Psychiatry has evolved away from this line of thinking by focusing on the distress from biological sex characteristics that are “incongruent” with an individual’s gender identity, leading to the development of the gender dysphoria diagnosis.13 While this has been a positive step in psychiatry’s efforts to de-pathologize individuals who are gender-diverse, it raises the question: should such diagnoses be included in the DSM at all?

The gender dysphoria diagnosis continues to be needed by many individuals who are TGGD in order to access gender-affirming health care services. Mental health professionals are placed in a gatekeeping role by the expectation that they provide letters of “support” to indicate an individual is of sound mind and consistent gender identity to have services covered by insurance providers. In this way, the insurance industry and the field of medicine continue to believe that individuals who are TGGD need psychiatric permission and/or counsel regarding their gender identity. This can place psychiatry in a role of controlling access to necessary care while also creating a possible distrust in our ability to provide care to patients who are gender-diverse. This is particularly problematic given the high rates of depression, anxiety, trauma, and substance use within these communities.14 In the WHO’s ICD-11, gender dysphoria was changed to gender incongruence and is contained in the category of “Conditions related to sexual health.”15 This indicates continued evolution of how medicine views individuals who are TGGD, and offers hope that psychiatry and the DSM will follow suit.

Continue to: Minority stress theory

Minority stress theory

Ilan Meyer’s minority stress theory explores how cultural and social factors impact mental health functioning (Figure 216). Minority stress theory, which was originally developed for what at the time was described as the lesbian, gay, and bisexual communities, purports that the higher prevalence of mental health disorders among such individuals is likely due to social stigma, discrimination, and stressors associated with minority status. More recently, minority stress theory has been expanded to provide framework for individuals who are TGGD. Hendricks et al17 explain how distal, proximal, and resilience factors contribute to mental health outcomes among these individuals. Distal factors, such as gender-related discrimination, harassment, violence, and rejection, explain how systemic, cultural, and environmental events lead to overt stress. Proximal factors consist of an individual’s expectation and anticipation of negative and stressful events and the internalization of negative attitudes and prejudice (ie, internalized transphobia). Resilience factors consist of community connectedness and within-group identification and can help mediate the negative effects of distal and proximal factors.

As clinicians, understanding our patients’ experiences and expectations can help us better engage with them and create an environment of safety and healing. Minority stress theory framework suggests that patients may start treatment with distrust or suspicion in light of previous negative experiences. They may also be likely to expect clinicians to be judgmental or to lack understanding of them. The 2015 US Transgender Survey found that 33% of individuals who are TGGD who sought medical treatment in the past year had at least 1 negative experience related to their gender identity (Table 118). Twenty-four percent reported having to educate their clinician about people who are TGGD, while 15% reported the health care professional asked invasive or unnecessary questions about their gender status that were unrelated to their visit. While psychiatry is often distinct from the larger medical field, it is important to understand the negative encounters individuals who are TGGD have likely experienced in medicine, and how those events may skew their feelings about psychiatric treatment. This is especially salient given the higher prevalence of various psychiatric disorders among individuals who are TGGD.18

According to the US Transgender Survey, 39% of participants were currently experiencing serious psychological distress, which is nearly 8 times the rate in the US population (5%).18 When extrapolated, this data indicates that we in psychiatry are likely to work with individuals who identify as TGGD, regardless of our expertise. Additionally, research indicates that having access to gender-affirming care—such as hormone replacement therapy, gender-affirming surgery, voice therapy, and other treatments—greatly improves mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and suicidality among individuals who are TGGD.19,20 It is in this way we in psychiatry must do more than just care for our patients by becoming advocates for them to receive the care they need and deserve. While at times we may want to stay out of politics and other public discourse, it is becoming increasingly necessary as health care is entrenched in politics.

Clinical applicability

Because individuals who are TGGD experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance use, and other psychiatric disorders,14 it is increasingly likely that many clinicians will be presented with opportunities to treat such individuals. Despite high rates of psychiatric disorders, individuals who are TGGD often avoid treatment due to concerns about being pathologized, stereotyped, and/or encountering professionals who lack the knowledge to treat them as they are.21 Several studies recommend clinicians better equip themselves to appropriately provide services to individuals who are TGGD.21 Some advise seeking education to understand the unique needs of these patients and to help stay current with appropriate terminology and language (Table 222). This also implies not relying on patients to educate clinicians in understanding their specific needs and experiences.

Making assumptions about a patient’s identity is one of the most commonly reported issues by individuals who are TGGD. Therefore, it is critical to avoid making assumptions about patients based on binary stereotypes.23,24 We can circumvent these mistakes by asking every patient for their name and pronouns, and introducing ourselves with our pronouns. This illustrates an openness and understanding of the importance of identity and language, and makes it common practice from the outset. Integrating the use of gender-neutral language into paperwork, intake forms, charting, and conversation will also help avoid the pitfalls of misgendering and making false assumptions. This will also allow for support staff, medical assistants, and others to use correct language with patients. Having a patient’s used name and pronouns visible for everyone who works with the patient is necessary to effectively meet the patient’s needs. Additionally, understanding that the range of experiences and needs for individuals who are TGGD is heterogeneous can help reduce assumptions and ensure we are asking for needed information. It is also important to ask for only relevant information needed to provide treatment.

Continue to: Resources are widely available...

Resources are widely available to aid in the care of individuals who are TGGD. In 2022, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health released new guidelines—Standards of Care 8—for working with individuals who are TGGD.25 While these standards include a section dedicated to mental health, they also provide guidelines on education, assessments, specific demographic groups, hormone therapy, primary care, and sexual health. Additionally, while we may not want the role of gatekeeping for individuals to receive gender-affirming care, we work within a health care and insurance system that continues to require psychiatric assessment for such surgeries. In this role, we must do our part to educate ourselves in how to best provide these assessments and letters of support to help patients receive appropriate and life-saving care.

Finally, in order to provide a more comfortable and affirming space for individuals who are TGGD, develop ways to self-assess and monitor the policies, procedures, and language used within your practice, clinic, or institution. Monitoring the language used in charting to ensure consistency with the individual’s gender identity is important for our own understanding of the patient, and for patients to feel seen. This is especially true given patients’ access to medical records under the Cures Act. Moreover, it is essential to be cognizant of how you present clients to others in consultation or care coordination to ensure the patient is identified correctly and consistently by clinicians and staff.

Bottom Line

Understanding the social, cultural, and medical discrimination faced by patients who are transgender or gender diverse can make us better suited to engage and treat these individuals in an affirming and supportive way.

Related Resources

- World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care—8th edition. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- The Fenway Institute: National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. https://fenwayhealth.org/the-fenway-institute/education/the-national-lgbtia-health-education-center/

Treating patients who are transgender or gender diverse (TGGD) requires an understanding of the social and psychological factors that have a unique impact on this population. As clinicians, it is our responsibility to understand the social, cultural, and political issues our patients face, both historically and currently. In this article, we provide information about the nature of gender and gender identity as separate from biological sex and informed by a person’s perception of self as male, female, nonbinary, or other variation.

Psychiatrists must be aware of how individuals who are TGGD have been perceived, classified, and treated by the medical profession, as this history is often a source of mistrust and a barrier to treatment for patients who need psychiatric care. This includes awareness of the “gatekeeping” role that persists in medical institutions today: applying strict eligibility criteria to determine the “fitness” of individuals who are transgender to pursue medical transition, as compared to the informed-consent model that is widely applied to other medical interventions. Our review of minority stress theory, as applicable to this patient population, provides a context and framework for empathic approaches to care for patients who are TGGD. Recognizing barriers to care and ways in which we can create a supportive environment for treatment will allow for tailored approaches that better fit the unique needs of this patient population.

The gender binary

In Western societies, gender has often been viewed as “binary,” oppositional, and directly correlated with physical sex or presumed anatomy.1 The theory of gender essentialism insists that sex and gender are indistinguishable from one another and provide 2 “natural” and distinct categories: women and men. The “gender/sex” binary refers to the belief that individuals born with 2 X chromosomes will inherently develop into and fulfill the social roles of women, and those born with an X and a Y chromosome will develop into and fulfill the social roles of men.1 In this context, “sex” refers to biological characteristics of individuals, including combinations of sex chromosomes, anatomy, and the development of sex characteristics during puberty. The term “gender” refers to the social, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man, woman, both, or neither, and “gender identity” refers to one’s internal, individual sense of self and experience of gender (Figure 12). Many Western cultures are now facing destabilization of the gender/sex binary in social, political, and interpersonal contexts.1 This is perhaps most clearly seen in the battle for self-determination and protection by laws affecting individuals who are transgender as well as the determination of other groups to maintain traditional sex and gender roles, often through political action. Historically, individuals who are TGGD have been present in a variety of cultures. For example, most Native American cultures have revered other-gendered individuals, more recently referred to as “two-spirited.” Similarly, the Bugis people of South Sulawesi, Indonesia, recognize 5 genders that exist on a nonbinary spectrum.3

Despite its prevalence in Western society, scientific evidence for the gender/sex binary is lacking. The gender similarities hypothesis states that males and females are similar in most, but not all, psychological variables and is supported by multiple meta-analyses examining psychological gender differences.4 In a 2005 review of 46 meta-analyses of gender-differences, studied through behavior analysis, effect sizes for gender differences were trivial or small in almost 75% of examined variables.5 Analyzing for internal consistency among studies showing large gender/sex differences, Joel et al6 found that, on measures of personality traits, attitudes, interests, and behaviors were rarely homogenous in the brains of males or females. In fact, <1% of study participants showed only masculine or feminine traits, whereas 55% showed a combination, or mosaic, of these traits.6 These findings were supported by further research in behavioral neuroendocrinology that demonstrated a lack of hormonal evidence for 2 distinct sexes. Both estrogen (the “female” hormone) and testosterone (the “male” hormone) are produced by both biological males and females. Further, levels of estradiol do not significantly differ between males and females, and, in fact, in nonpregnant females, estradiol levels are more similar to those of males than to those of pregnant females.1 In the last decade, imaging studies of the human brain have shown that brain structure and connectivity in individuals who are transgender are more similar to those of their experienced gender than of their natal sex.7 In social analyses of intersex individuals (individuals born with ambiguous physical sex characteristics), surgical assignment into the binary gender system did not improve—and often worsened—feelings of isolation and shame.1

The National Institutes of Health defines gender as “socially constructed and enacted roles and behaviors which occur in a historical and cultural context and vary across societies and time.”8 The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a similar definition, and the evidence to support this exists in social-role theory, social-identity theory, and the stereotype-content model. However, despite evidence disputing a gender/sex binary, this method of classifying individuals into a dyad persists in many areas of modern culture, from gender-specific physical spaces (bathrooms, classrooms, store brands), language (pronouns), and laws. This desire for categorization helps fulfill social and psychological needs of groups and individuals by providing group identities and giving structure to the complexity of modern-day life. Identity and group membership provide a sense of belonging, source of self-esteem, and avoidance of ambiguity. Binary gender stereotypes provide expectations that allow anticipation and prediction of our social environments.9 However, the harm of perpetuating the false gender/sex binary is well documented and includes social and economic penalties, extreme violence, and even death. The field of medicine has not been immune from practices that implicitly endorse the gender/sex connection, as seen in the erroneous use of gender in biomedical writings at the highest levels and evidenced in research examining “gender” differences in disease incidence.

Gender diversity as a pathology

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has been a source of pathologizing gender diversity since the 1960s, with the introduction of “transsexualism” in DSM-II10 and “gender identity disorder of childhood” in DSM-III.11 These diagnoses were listed under the headings of “sexual deviations” and “psychosexual disorders” in the respective DSM editions. This illustrates how gender diversity was viewed as a mental illness/defect. As the DSM developed through various revisions, so have these diagnoses. DSM-IV used the diagnosis “gender identity disorder.”12 Psychiatry has evolved away from this line of thinking by focusing on the distress from biological sex characteristics that are “incongruent” with an individual’s gender identity, leading to the development of the gender dysphoria diagnosis.13 While this has been a positive step in psychiatry’s efforts to de-pathologize individuals who are gender-diverse, it raises the question: should such diagnoses be included in the DSM at all?

The gender dysphoria diagnosis continues to be needed by many individuals who are TGGD in order to access gender-affirming health care services. Mental health professionals are placed in a gatekeeping role by the expectation that they provide letters of “support” to indicate an individual is of sound mind and consistent gender identity to have services covered by insurance providers. In this way, the insurance industry and the field of medicine continue to believe that individuals who are TGGD need psychiatric permission and/or counsel regarding their gender identity. This can place psychiatry in a role of controlling access to necessary care while also creating a possible distrust in our ability to provide care to patients who are gender-diverse. This is particularly problematic given the high rates of depression, anxiety, trauma, and substance use within these communities.14 In the WHO’s ICD-11, gender dysphoria was changed to gender incongruence and is contained in the category of “Conditions related to sexual health.”15 This indicates continued evolution of how medicine views individuals who are TGGD, and offers hope that psychiatry and the DSM will follow suit.

Continue to: Minority stress theory

Minority stress theory

Ilan Meyer’s minority stress theory explores how cultural and social factors impact mental health functioning (Figure 216). Minority stress theory, which was originally developed for what at the time was described as the lesbian, gay, and bisexual communities, purports that the higher prevalence of mental health disorders among such individuals is likely due to social stigma, discrimination, and stressors associated with minority status. More recently, minority stress theory has been expanded to provide framework for individuals who are TGGD. Hendricks et al17 explain how distal, proximal, and resilience factors contribute to mental health outcomes among these individuals. Distal factors, such as gender-related discrimination, harassment, violence, and rejection, explain how systemic, cultural, and environmental events lead to overt stress. Proximal factors consist of an individual’s expectation and anticipation of negative and stressful events and the internalization of negative attitudes and prejudice (ie, internalized transphobia). Resilience factors consist of community connectedness and within-group identification and can help mediate the negative effects of distal and proximal factors.

As clinicians, understanding our patients’ experiences and expectations can help us better engage with them and create an environment of safety and healing. Minority stress theory framework suggests that patients may start treatment with distrust or suspicion in light of previous negative experiences. They may also be likely to expect clinicians to be judgmental or to lack understanding of them. The 2015 US Transgender Survey found that 33% of individuals who are TGGD who sought medical treatment in the past year had at least 1 negative experience related to their gender identity (Table 118). Twenty-four percent reported having to educate their clinician about people who are TGGD, while 15% reported the health care professional asked invasive or unnecessary questions about their gender status that were unrelated to their visit. While psychiatry is often distinct from the larger medical field, it is important to understand the negative encounters individuals who are TGGD have likely experienced in medicine, and how those events may skew their feelings about psychiatric treatment. This is especially salient given the higher prevalence of various psychiatric disorders among individuals who are TGGD.18

According to the US Transgender Survey, 39% of participants were currently experiencing serious psychological distress, which is nearly 8 times the rate in the US population (5%).18 When extrapolated, this data indicates that we in psychiatry are likely to work with individuals who identify as TGGD, regardless of our expertise. Additionally, research indicates that having access to gender-affirming care—such as hormone replacement therapy, gender-affirming surgery, voice therapy, and other treatments—greatly improves mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and suicidality among individuals who are TGGD.19,20 It is in this way we in psychiatry must do more than just care for our patients by becoming advocates for them to receive the care they need and deserve. While at times we may want to stay out of politics and other public discourse, it is becoming increasingly necessary as health care is entrenched in politics.

Clinical applicability

Because individuals who are TGGD experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, substance use, and other psychiatric disorders,14 it is increasingly likely that many clinicians will be presented with opportunities to treat such individuals. Despite high rates of psychiatric disorders, individuals who are TGGD often avoid treatment due to concerns about being pathologized, stereotyped, and/or encountering professionals who lack the knowledge to treat them as they are.21 Several studies recommend clinicians better equip themselves to appropriately provide services to individuals who are TGGD.21 Some advise seeking education to understand the unique needs of these patients and to help stay current with appropriate terminology and language (Table 222). This also implies not relying on patients to educate clinicians in understanding their specific needs and experiences.

Making assumptions about a patient’s identity is one of the most commonly reported issues by individuals who are TGGD. Therefore, it is critical to avoid making assumptions about patients based on binary stereotypes.23,24 We can circumvent these mistakes by asking every patient for their name and pronouns, and introducing ourselves with our pronouns. This illustrates an openness and understanding of the importance of identity and language, and makes it common practice from the outset. Integrating the use of gender-neutral language into paperwork, intake forms, charting, and conversation will also help avoid the pitfalls of misgendering and making false assumptions. This will also allow for support staff, medical assistants, and others to use correct language with patients. Having a patient’s used name and pronouns visible for everyone who works with the patient is necessary to effectively meet the patient’s needs. Additionally, understanding that the range of experiences and needs for individuals who are TGGD is heterogeneous can help reduce assumptions and ensure we are asking for needed information. It is also important to ask for only relevant information needed to provide treatment.

Continue to: Resources are widely available...

Resources are widely available to aid in the care of individuals who are TGGD. In 2022, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health released new guidelines—Standards of Care 8—for working with individuals who are TGGD.25 While these standards include a section dedicated to mental health, they also provide guidelines on education, assessments, specific demographic groups, hormone therapy, primary care, and sexual health. Additionally, while we may not want the role of gatekeeping for individuals to receive gender-affirming care, we work within a health care and insurance system that continues to require psychiatric assessment for such surgeries. In this role, we must do our part to educate ourselves in how to best provide these assessments and letters of support to help patients receive appropriate and life-saving care.

Finally, in order to provide a more comfortable and affirming space for individuals who are TGGD, develop ways to self-assess and monitor the policies, procedures, and language used within your practice, clinic, or institution. Monitoring the language used in charting to ensure consistency with the individual’s gender identity is important for our own understanding of the patient, and for patients to feel seen. This is especially true given patients’ access to medical records under the Cures Act. Moreover, it is essential to be cognizant of how you present clients to others in consultation or care coordination to ensure the patient is identified correctly and consistently by clinicians and staff.

Bottom Line

Understanding the social, cultural, and medical discrimination faced by patients who are transgender or gender diverse can make us better suited to engage and treat these individuals in an affirming and supportive way.

Related Resources

- World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care—8th edition. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

- The Fenway Institute: National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. https://fenwayhealth.org/the-fenway-institute/education/the-national-lgbtia-health-education-center/

1. Morgenroth T, Ryan MK. The effects of gender trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16(6):1113-1142. doi:10.1177/1745691620902442

2. The Roots of Loneliness Project. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.rootsofloneliness.com/gender-identity-loneliness

3. Davies SG. Challenging Gender Norms: Five Genders Among Bugis in Indonesia. Thomson Wadsworth; 2007.

4. Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol. 2005;60(6):581-592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

5. Joel D. Beyond the binary: rethinking sex and the brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;122:165-175. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.22.018

6. Joel D, Berman Z, Tavor I, et al. Sex beyond the genitalia: the human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(50):15468-15473. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509654112

7. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. A universally accepted definition of gender will positively impact societal understanding, acceptance, and appropriateness of health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2235-2243. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.031

8. Office of Research on Women’s Health. Sex & Gender. National Institutes of Health. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender

9. Morgenroth T, Sendén MG, Lindqvist A, et al. Defending the sex/gender binary: the role of gender identification and need for closure. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021;12(5):731-740.

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1968.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

14. Wanta JW, Niforatos JD, Durbak E, et al. Mental health diagnoses among transgender patients in the clinical setting: an all-payer electronic health record study. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):313-315.

15. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases. 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

16. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

17. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Profess Psychol: Res Pract. 2012;43(5):460-467. doi:10.1037/a0029597

18. James SE, Herman J, Keisling M, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

19. Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):611-618. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952

20. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

21. Snow A, Cerel J, Loeffler DN, et al. Barriers to mental health care for transgender and gender-nonconforming adults: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Work. 2019;44(3):149-155. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlz016

22. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org

23. Baldwin A, Dodge B, Schick VR, et al. Transgender and genderqueer individuals’ experiences with health care providers: what’s working, what’s not, and where do we go from here? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(4):1300-1318. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0097

24. Kcomt L, Gorey KM, Barrett BJ, et al. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: a call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM-Popul Health. 2020;11:100608. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100608

25. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259.

1. Morgenroth T, Ryan MK. The effects of gender trouble: an integrative theoretical framework of the perpetuation and disruption of the gender/sex binary. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16(6):1113-1142. doi:10.1177/1745691620902442

2. The Roots of Loneliness Project. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.rootsofloneliness.com/gender-identity-loneliness

3. Davies SG. Challenging Gender Norms: Five Genders Among Bugis in Indonesia. Thomson Wadsworth; 2007.

4. Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol. 2005;60(6):581-592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581

5. Joel D. Beyond the binary: rethinking sex and the brain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;122:165-175. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.22.018

6. Joel D, Berman Z, Tavor I, et al. Sex beyond the genitalia: the human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(50):15468-15473. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509654112

7. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. A universally accepted definition of gender will positively impact societal understanding, acceptance, and appropriateness of health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(10):2235-2243. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.031

8. Office of Research on Women’s Health. Sex & Gender. National Institutes of Health. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex-gender

9. Morgenroth T, Sendén MG, Lindqvist A, et al. Defending the sex/gender binary: the role of gender identification and need for closure. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2021;12(5):731-740.

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1968.

11. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

14. Wanta JW, Niforatos JD, Durbak E, et al. Mental health diagnoses among transgender patients in the clinical setting: an all-payer electronic health record study. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):313-315.

15. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases. 11th ed. World Health Organization; 2019.

16. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

17. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Profess Psychol: Res Pract. 2012;43(5):460-467. doi:10.1037/a0029597

18. James SE, Herman J, Keisling M, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. Accessed April 6, 2023. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

19. Almazan AN, Keuroghlian AS. Association between gender-affirming surgeries and mental health outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(7):611-618. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0952

20. Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978

21. Snow A, Cerel J, Loeffler DN, et al. Barriers to mental health care for transgender and gender-nonconforming adults: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Work. 2019;44(3):149-155. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlz016

22. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org

23. Baldwin A, Dodge B, Schick VR, et al. Transgender and genderqueer individuals’ experiences with health care providers: what’s working, what’s not, and where do we go from here? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(4):1300-1318. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0097

24. Kcomt L, Gorey KM, Barrett BJ, et al. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: a call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM-Popul Health. 2020;11:100608. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100608

25. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgender Health. 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1-S259.