User login

Worse outcomes for patients with COPD and COVID-19

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study of COVID-19 outcomes across the United States bolsters reports from China and Europe that indicate that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and SARS-CoV-2 infection have worse outcomes than those of patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD.

Investigators at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Texas, combed through electronic health records from four geographic regions of the United States and identified a cohort of 6,056 patients with COPD among 150,775 patients whose records indicate either a diagnostic code or a positive laboratory test result for COVID-19.

Their findings indicate that patients with both COPD and COVID-19 “have worse outcomes compared to non-COPD COVID-19 patients, including 14-day hospitalization, length of stay, ICU admission, 30-day mortality, and use of mechanical ventilation,” Daniel Puebla Neira, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas Medical Branch reported in a thematic poster presented during the American Thoracic Society (ATS) 2021 virtual international conference.

A critical care specialist who was not involved in the study said that the results are concerning but not surprising.

“If you already have a lung disease and you develop an additional lung disease on top of that, you don’t have as much reserve and you’re not going to tolerate the acute COVID infection,” said ATS expert Marc Moss, MD, Roger S. Mitchell Professor of Medicine in the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The evidence shows that “patients with COPD should be even more cautious, because if they get sick and develop, they could do worse,” he said in an interview.

Retrospective analysis

Dr. Neira and colleagues assessed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with COPD who were treated for COVID-19 in the United States from March through August 2020.

Baseline demographics of the patients with and those without COPD were similar except that the mean age was higher among patients with COPD (68.62 vs. 47.08 years).

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients with COPD had comorbidities compared with those without COPD. Comorbidities included diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, stroke, heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease, and liver disease (P < .0001 for all comparisons).

Among patients with COPD, percentages were higher with respect to the following parameters: 14-day hospitalization for any cause (28.7% vs. 10.4%), COVID-19-related 14-day hospitalization (28.1% vs. 9.9%), ICU use (26.3% vs. 17.9%), mechanical ventilation use (26.3% vs. 16.1%), and 30-day mortality (13.6% vs. 7.2%; P < .0001 for all comparisons).

‘Mechanisms unclear’

“It is unclear what mechanisms drive the association between COPD and mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote. “Several biological factors have been proposed, including chronic lung inflammation, oxidative stress, protease-antiprotease imbalance, and increased airway mediators.”

They recommend use of multivariable logistic regression to tease out the effects of covariates among patients with COPD and COVID-19 and call for research into long-term outcomes for these patients, “as survivors of critical illness are increasingly recognized to have cognitive, psychological, and physical consequences.”

Dr. Moss said that in general, the management of patients with COPD and COVID-19 is similar to that for patients with COVID-19 who do not have COPD, although there may be “subtle” differences, such as ventilator settings for patients with COPD.

No source of funding for the study has been disclosed. The investigators and Dr. Moss have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atorvastatin: A potential treatment in COVID-19?

For patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care, giving atorvastatin 20 mg/d did not result in a significant reduction in risk for venous or arterial thrombosis, for treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or for all-cause mortality, compared with placebo in the INSPIRATION-S study.

However, there was a suggestion of benefit in the subgroup of patients who were treated within 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset.

The study was presented by Behnood Bikdeli, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, on May 16 at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He explained that COVID-19 is characterized by an exuberant immune response and that there is a potential for thrombotic events because of enhanced endothelial activation and a prothrombotic state.

“In this context, it is interesting to think about statins as potential agents to be studied in COVID-19, because as well as having lipid-lowering actions, they are also thought to have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects,” he said.

In the HARP-2 trial of simvastatin in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), published a few years ago, the main results were neutral, but in the subgroup of patients with hyperinflammatory ARDS, there was a reduction in mortality with simvastatin in comparison with placebo, Dr. Bikdeli noted.

Moreover, in a series of observational studies of patients with COVID-19, use of statins was associated with a reduction in mortality among hospitalized patients. However, there are limited high-quality data to guide clinical practice, he said.

The INSPIRATION study, conducted in 11 hospitals in Iran, had a two-by-two factorial design to investigate different anticoagulant strategies and the use of atorvastatin for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

In the anticoagulation part of the trial, which was published in JAMA in March 2020, there was no difference in the primary endpoint of an intermediate dose and standard dose of enoxaparin.

For the statin part of the trial (INSPIRATION-S), 605 patients were randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin 20 mg daily or placebo. Patients who had been taking statins beforehand were excluded. Baseline characteristics were similar for the two groups, with around a quarter of patients taking aspirin and more than 90% taking steroids.

Results showed that atorvastatin was not associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome – a composite of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with ECMO, or mortality within 30 days – which occurred in 32.7% of the statin group versus 36.3% of the placebo group (odds ratio, 0.84; P = .35).

Atorvastatin was not associated with any significant differences in any of the individual components of the primary composite endpoint. There was also no significant difference in any of the safety endpoints, which included major bleeding and elevations in liver enzyme levels.

Subgroup analyses were mostly consistent with the main findings, with one exception.

In the subgroup of patients who presented within the first 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, there was a hint of a potential protective effect with atorvastatin.

In this group of 171 patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 30.9% of those taking atorvastatin versus 40.3% of those taking placebo (OR, 0.60; P = .055).

“This is an interesting observation, and it is plausible, as these patients may be in a different phase of COVID-19 disease. But we need to be cognizant of the multiplicity of comparisons, and this needs to be further investigated in subsequent studies,” Dr. Bikdeli said.

Higher dose in less sick patients a better strategy?

Discussing the study at the ACC presentation, Binita Shah, MD, said the importance of enrolling COVID-19 patients into clinical trials was paramount but that these patients in the ICU may not have been the right population in which to test a statin.

“Maybe for these very sick patients, it is just too late. Trying to rein in the inflammatory cytokine storm and the interaction with thrombosis at this point is very difficult,” Dr. Shah commented.

She suggested that it might be appropriate to try statins in an earlier phase of the disease in order to prevent the inflammatory process, rather than trying to stop it after it had already started.

Dr. Shah also questioned the use of such a low dose of atorvastatin for these patients. “In the cardiovascular literature – at least in ACS [acute coronary syndrome] – high statin doses are used to see short-term benefits. In this very inflammatory milieu, I wonder whether a high-intensity regimen would be more beneficial,” she speculated.

Dr. Bikdeli replied that a low dose of atorvastatin was chosen because early on, several antiviral agents, such as ritonavir, were being used for COVID-19 patients, and these drugs were associated with increases in liver enzyme levels.

“We didn’t want to exacerbate that with high doses of statins,” he said. “But we have now established the safety profile of atorvastatin in these patients, and in retrospect, yes, a higher dose might have been better.”

The INSPIRATION study was funded by the Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Tehran, Iran. Dr. Bikdeli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care, giving atorvastatin 20 mg/d did not result in a significant reduction in risk for venous or arterial thrombosis, for treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or for all-cause mortality, compared with placebo in the INSPIRATION-S study.

However, there was a suggestion of benefit in the subgroup of patients who were treated within 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset.

The study was presented by Behnood Bikdeli, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, on May 16 at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He explained that COVID-19 is characterized by an exuberant immune response and that there is a potential for thrombotic events because of enhanced endothelial activation and a prothrombotic state.

“In this context, it is interesting to think about statins as potential agents to be studied in COVID-19, because as well as having lipid-lowering actions, they are also thought to have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects,” he said.

In the HARP-2 trial of simvastatin in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), published a few years ago, the main results were neutral, but in the subgroup of patients with hyperinflammatory ARDS, there was a reduction in mortality with simvastatin in comparison with placebo, Dr. Bikdeli noted.

Moreover, in a series of observational studies of patients with COVID-19, use of statins was associated with a reduction in mortality among hospitalized patients. However, there are limited high-quality data to guide clinical practice, he said.

The INSPIRATION study, conducted in 11 hospitals in Iran, had a two-by-two factorial design to investigate different anticoagulant strategies and the use of atorvastatin for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

In the anticoagulation part of the trial, which was published in JAMA in March 2020, there was no difference in the primary endpoint of an intermediate dose and standard dose of enoxaparin.

For the statin part of the trial (INSPIRATION-S), 605 patients were randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin 20 mg daily or placebo. Patients who had been taking statins beforehand were excluded. Baseline characteristics were similar for the two groups, with around a quarter of patients taking aspirin and more than 90% taking steroids.

Results showed that atorvastatin was not associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome – a composite of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with ECMO, or mortality within 30 days – which occurred in 32.7% of the statin group versus 36.3% of the placebo group (odds ratio, 0.84; P = .35).

Atorvastatin was not associated with any significant differences in any of the individual components of the primary composite endpoint. There was also no significant difference in any of the safety endpoints, which included major bleeding and elevations in liver enzyme levels.

Subgroup analyses were mostly consistent with the main findings, with one exception.

In the subgroup of patients who presented within the first 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, there was a hint of a potential protective effect with atorvastatin.

In this group of 171 patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 30.9% of those taking atorvastatin versus 40.3% of those taking placebo (OR, 0.60; P = .055).

“This is an interesting observation, and it is plausible, as these patients may be in a different phase of COVID-19 disease. But we need to be cognizant of the multiplicity of comparisons, and this needs to be further investigated in subsequent studies,” Dr. Bikdeli said.

Higher dose in less sick patients a better strategy?

Discussing the study at the ACC presentation, Binita Shah, MD, said the importance of enrolling COVID-19 patients into clinical trials was paramount but that these patients in the ICU may not have been the right population in which to test a statin.

“Maybe for these very sick patients, it is just too late. Trying to rein in the inflammatory cytokine storm and the interaction with thrombosis at this point is very difficult,” Dr. Shah commented.

She suggested that it might be appropriate to try statins in an earlier phase of the disease in order to prevent the inflammatory process, rather than trying to stop it after it had already started.

Dr. Shah also questioned the use of such a low dose of atorvastatin for these patients. “In the cardiovascular literature – at least in ACS [acute coronary syndrome] – high statin doses are used to see short-term benefits. In this very inflammatory milieu, I wonder whether a high-intensity regimen would be more beneficial,” she speculated.

Dr. Bikdeli replied that a low dose of atorvastatin was chosen because early on, several antiviral agents, such as ritonavir, were being used for COVID-19 patients, and these drugs were associated with increases in liver enzyme levels.

“We didn’t want to exacerbate that with high doses of statins,” he said. “But we have now established the safety profile of atorvastatin in these patients, and in retrospect, yes, a higher dose might have been better.”

The INSPIRATION study was funded by the Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Tehran, Iran. Dr. Bikdeli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care, giving atorvastatin 20 mg/d did not result in a significant reduction in risk for venous or arterial thrombosis, for treatment with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or for all-cause mortality, compared with placebo in the INSPIRATION-S study.

However, there was a suggestion of benefit in the subgroup of patients who were treated within 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset.

The study was presented by Behnood Bikdeli, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, on May 16 at the annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He explained that COVID-19 is characterized by an exuberant immune response and that there is a potential for thrombotic events because of enhanced endothelial activation and a prothrombotic state.

“In this context, it is interesting to think about statins as potential agents to be studied in COVID-19, because as well as having lipid-lowering actions, they are also thought to have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic effects,” he said.

In the HARP-2 trial of simvastatin in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), published a few years ago, the main results were neutral, but in the subgroup of patients with hyperinflammatory ARDS, there was a reduction in mortality with simvastatin in comparison with placebo, Dr. Bikdeli noted.

Moreover, in a series of observational studies of patients with COVID-19, use of statins was associated with a reduction in mortality among hospitalized patients. However, there are limited high-quality data to guide clinical practice, he said.

The INSPIRATION study, conducted in 11 hospitals in Iran, had a two-by-two factorial design to investigate different anticoagulant strategies and the use of atorvastatin for COVID-19 patients in the ICU.

In the anticoagulation part of the trial, which was published in JAMA in March 2020, there was no difference in the primary endpoint of an intermediate dose and standard dose of enoxaparin.

For the statin part of the trial (INSPIRATION-S), 605 patients were randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin 20 mg daily or placebo. Patients who had been taking statins beforehand were excluded. Baseline characteristics were similar for the two groups, with around a quarter of patients taking aspirin and more than 90% taking steroids.

Results showed that atorvastatin was not associated with a significant reduction in the primary outcome – a composite of adjudicated venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with ECMO, or mortality within 30 days – which occurred in 32.7% of the statin group versus 36.3% of the placebo group (odds ratio, 0.84; P = .35).

Atorvastatin was not associated with any significant differences in any of the individual components of the primary composite endpoint. There was also no significant difference in any of the safety endpoints, which included major bleeding and elevations in liver enzyme levels.

Subgroup analyses were mostly consistent with the main findings, with one exception.

In the subgroup of patients who presented within the first 7 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, there was a hint of a potential protective effect with atorvastatin.

In this group of 171 patients, the primary endpoint occurred in 30.9% of those taking atorvastatin versus 40.3% of those taking placebo (OR, 0.60; P = .055).

“This is an interesting observation, and it is plausible, as these patients may be in a different phase of COVID-19 disease. But we need to be cognizant of the multiplicity of comparisons, and this needs to be further investigated in subsequent studies,” Dr. Bikdeli said.

Higher dose in less sick patients a better strategy?

Discussing the study at the ACC presentation, Binita Shah, MD, said the importance of enrolling COVID-19 patients into clinical trials was paramount but that these patients in the ICU may not have been the right population in which to test a statin.

“Maybe for these very sick patients, it is just too late. Trying to rein in the inflammatory cytokine storm and the interaction with thrombosis at this point is very difficult,” Dr. Shah commented.

She suggested that it might be appropriate to try statins in an earlier phase of the disease in order to prevent the inflammatory process, rather than trying to stop it after it had already started.

Dr. Shah also questioned the use of such a low dose of atorvastatin for these patients. “In the cardiovascular literature – at least in ACS [acute coronary syndrome] – high statin doses are used to see short-term benefits. In this very inflammatory milieu, I wonder whether a high-intensity regimen would be more beneficial,” she speculated.

Dr. Bikdeli replied that a low dose of atorvastatin was chosen because early on, several antiviral agents, such as ritonavir, were being used for COVID-19 patients, and these drugs were associated with increases in liver enzyme levels.

“We didn’t want to exacerbate that with high doses of statins,” he said. “But we have now established the safety profile of atorvastatin in these patients, and in retrospect, yes, a higher dose might have been better.”

The INSPIRATION study was funded by the Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Tehran, Iran. Dr. Bikdeli has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 fallout makes case for promoting the mental health czar

When the Biden administration announced who would serve on its COVID-19 task force, some asked why a mental health expert had not been included. I have a broader question: In light of the magnitude of the pandemic’s fallout, why doesn’t the administration create a mental health post parallel to the surgeon general?

I have been making the case for creation of a high-level mental health post for quite some time. In fact, in the late 1970s, toward the end of then-President Jimmy Carter’s term, I wrote and talked about the need for a special cabinet post of mental health. At the time I realized that, besides chronic mental disorders, the amount of mental distress people experienced from a myriad of life issues leading to anxiety, depression, even posttraumatic stress disorder (although not labeled as such then), needed focused and informed leadership.

Before the pandemic, the World Health Organization reported that depression was the leading cause of disability worldwide. In the prepandemic United States, mental and substance use disorders were the top cause of disability among younger people.

We’ve lost almost 600,000 people to COVID-19, and people have been unable to grieve properly. More than 2 million women have left the labor force to care for children and sick family members. As we continue to learn about the mental health–related devastation wrought by SARS-CoV-2 – particularly long-haul COVID-19 – it’s time to dust off my proposal, update it, and implement it.

Building on a good decision

Back in 2017, President Trump appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, to a new post officially called “assistant secretary for mental health and substance use” and unofficially called the “mental health czar.” This was a groundbreaking step, because Dr. McCance-Katz, a psychiatrist, is known for developing innovative approaches to addressing the opioid crisis in her home state of Rhode Island. She resigned from her post on Jan. 7, 2021, citing her concerns about the Jan. 6 insurrection on the U.S. Capitol.

As of this writing, President Biden has nominated psychologist Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, PhD, who is commissioner of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, as mental health czar. I’m glad to see that the new administration wants a new czar, but I would prefer to see a more expansive role for a mental health professional at the federal level. The reason is because

Processing the current crisis

Americans managed to recover emotionally from the ravages of death and dying from World War II; we lived through the “atomic age” of mutual destruction, sometimes calling it the age of anxiety. But nothing has come close to the overwhelming devastation that COVID-19 has brought to the world – and to this country.

A recent Government Accountability Office report shows 38% of U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from April 2020 through February 2021. That was up from 11% from January to June 2019, the report said, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meanwhile, the report cites data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration showing that opioid deaths were 25%-50% higher during the pandemic than a year earlier.

My sense is that people generally have opened up regarding their emotional problems in a freer manner, thus allowing us to speak about and accept mental health problems as part of our human reality – just as we accept physical disorders and search for treatment and care.

In terms of talk therapy, I still believe that the “thinking” therapies, that is, cognitive therapies that involved getting a new perspective on problems, are most effective in dealing with the myriad of emotional issues people experience as well as those that have arisen because of COVID-19, and the tremendous fear of severe illness and death that the virus can bring. Besides anxiety, depression, and fear, the psychological toll of a fractured lifestyle, coupled with social isolation, will lead many into a variety of PTSD-related conditions. Many of those conditions, including PTSD, might lift when COVID-19 is controlled, but the time frame for resolution is far from clear and will vary, depending on each person. National leadership, as well as therapists, need to be ready to work with the many mental health problems COVID-19 will leave in its wake.

Therapeutically, as we develop our cognitive approaches to the problems this pandemic has brought, whether affecting people with no past psychiatric history or those with a previous or ongoing problems, we are in a unique position ourselves to offer even more support based on our own experiences during the pandemic. Our patients have seen us wear masks and work remotely, and just as we know about their suffering, they know we have been affected as well. These shared experiences with patients can allow us to express even greater empathy and offer even greater support – which I believe enhances the cognitive process and adds more humanism to the therapeutic process.

The therapists I’ve talked with believe that sharing coping skills – even generally sharing anxieties – can be very therapeutic. They compared these exchanges to what is done in support or educational groups.

As a psychiatrist who has been treating patients using cognitive-behavioral therapy – the thinking therapy – for more than 40 years, I agree that sharing our experiences in this worldwide pandemic with those we are helping can be extremely beneficial. Using this approach would not distract from other cognitive work. CBT, after all, is a far cry from dynamic or psychoanalytic talking or listening.

Change is in the air. More and more Americans are getting vaccinated, and the CDC is constantly updating its guidance on COVID-19. That guidance should have a mental health component.

I urge the president to put mental health at the forefront by nominating an expert who could offer mental health solutions on a daily basis. This person should be on equal footing with the surgeon general. Taking this step would help destigmatize mental suffering and despair – and create greater awareness about how to address those conditions.

Dr. London has been a practicing psychiatrist for 4 decades and a newspaper columnist for almost as long. He has a private practice in New York and is author of “Find Freedom Fast: Short-Term Therapy That Works” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). Dr. London has no conflicts of interest.

When the Biden administration announced who would serve on its COVID-19 task force, some asked why a mental health expert had not been included. I have a broader question: In light of the magnitude of the pandemic’s fallout, why doesn’t the administration create a mental health post parallel to the surgeon general?

I have been making the case for creation of a high-level mental health post for quite some time. In fact, in the late 1970s, toward the end of then-President Jimmy Carter’s term, I wrote and talked about the need for a special cabinet post of mental health. At the time I realized that, besides chronic mental disorders, the amount of mental distress people experienced from a myriad of life issues leading to anxiety, depression, even posttraumatic stress disorder (although not labeled as such then), needed focused and informed leadership.

Before the pandemic, the World Health Organization reported that depression was the leading cause of disability worldwide. In the prepandemic United States, mental and substance use disorders were the top cause of disability among younger people.

We’ve lost almost 600,000 people to COVID-19, and people have been unable to grieve properly. More than 2 million women have left the labor force to care for children and sick family members. As we continue to learn about the mental health–related devastation wrought by SARS-CoV-2 – particularly long-haul COVID-19 – it’s time to dust off my proposal, update it, and implement it.

Building on a good decision

Back in 2017, President Trump appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, to a new post officially called “assistant secretary for mental health and substance use” and unofficially called the “mental health czar.” This was a groundbreaking step, because Dr. McCance-Katz, a psychiatrist, is known for developing innovative approaches to addressing the opioid crisis in her home state of Rhode Island. She resigned from her post on Jan. 7, 2021, citing her concerns about the Jan. 6 insurrection on the U.S. Capitol.

As of this writing, President Biden has nominated psychologist Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, PhD, who is commissioner of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, as mental health czar. I’m glad to see that the new administration wants a new czar, but I would prefer to see a more expansive role for a mental health professional at the federal level. The reason is because

Processing the current crisis

Americans managed to recover emotionally from the ravages of death and dying from World War II; we lived through the “atomic age” of mutual destruction, sometimes calling it the age of anxiety. But nothing has come close to the overwhelming devastation that COVID-19 has brought to the world – and to this country.

A recent Government Accountability Office report shows 38% of U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from April 2020 through February 2021. That was up from 11% from January to June 2019, the report said, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meanwhile, the report cites data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration showing that opioid deaths were 25%-50% higher during the pandemic than a year earlier.

My sense is that people generally have opened up regarding their emotional problems in a freer manner, thus allowing us to speak about and accept mental health problems as part of our human reality – just as we accept physical disorders and search for treatment and care.

In terms of talk therapy, I still believe that the “thinking” therapies, that is, cognitive therapies that involved getting a new perspective on problems, are most effective in dealing with the myriad of emotional issues people experience as well as those that have arisen because of COVID-19, and the tremendous fear of severe illness and death that the virus can bring. Besides anxiety, depression, and fear, the psychological toll of a fractured lifestyle, coupled with social isolation, will lead many into a variety of PTSD-related conditions. Many of those conditions, including PTSD, might lift when COVID-19 is controlled, but the time frame for resolution is far from clear and will vary, depending on each person. National leadership, as well as therapists, need to be ready to work with the many mental health problems COVID-19 will leave in its wake.

Therapeutically, as we develop our cognitive approaches to the problems this pandemic has brought, whether affecting people with no past psychiatric history or those with a previous or ongoing problems, we are in a unique position ourselves to offer even more support based on our own experiences during the pandemic. Our patients have seen us wear masks and work remotely, and just as we know about their suffering, they know we have been affected as well. These shared experiences with patients can allow us to express even greater empathy and offer even greater support – which I believe enhances the cognitive process and adds more humanism to the therapeutic process.

The therapists I’ve talked with believe that sharing coping skills – even generally sharing anxieties – can be very therapeutic. They compared these exchanges to what is done in support or educational groups.

As a psychiatrist who has been treating patients using cognitive-behavioral therapy – the thinking therapy – for more than 40 years, I agree that sharing our experiences in this worldwide pandemic with those we are helping can be extremely beneficial. Using this approach would not distract from other cognitive work. CBT, after all, is a far cry from dynamic or psychoanalytic talking or listening.

Change is in the air. More and more Americans are getting vaccinated, and the CDC is constantly updating its guidance on COVID-19. That guidance should have a mental health component.

I urge the president to put mental health at the forefront by nominating an expert who could offer mental health solutions on a daily basis. This person should be on equal footing with the surgeon general. Taking this step would help destigmatize mental suffering and despair – and create greater awareness about how to address those conditions.

Dr. London has been a practicing psychiatrist for 4 decades and a newspaper columnist for almost as long. He has a private practice in New York and is author of “Find Freedom Fast: Short-Term Therapy That Works” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). Dr. London has no conflicts of interest.

When the Biden administration announced who would serve on its COVID-19 task force, some asked why a mental health expert had not been included. I have a broader question: In light of the magnitude of the pandemic’s fallout, why doesn’t the administration create a mental health post parallel to the surgeon general?

I have been making the case for creation of a high-level mental health post for quite some time. In fact, in the late 1970s, toward the end of then-President Jimmy Carter’s term, I wrote and talked about the need for a special cabinet post of mental health. At the time I realized that, besides chronic mental disorders, the amount of mental distress people experienced from a myriad of life issues leading to anxiety, depression, even posttraumatic stress disorder (although not labeled as such then), needed focused and informed leadership.

Before the pandemic, the World Health Organization reported that depression was the leading cause of disability worldwide. In the prepandemic United States, mental and substance use disorders were the top cause of disability among younger people.

We’ve lost almost 600,000 people to COVID-19, and people have been unable to grieve properly. More than 2 million women have left the labor force to care for children and sick family members. As we continue to learn about the mental health–related devastation wrought by SARS-CoV-2 – particularly long-haul COVID-19 – it’s time to dust off my proposal, update it, and implement it.

Building on a good decision

Back in 2017, President Trump appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, to a new post officially called “assistant secretary for mental health and substance use” and unofficially called the “mental health czar.” This was a groundbreaking step, because Dr. McCance-Katz, a psychiatrist, is known for developing innovative approaches to addressing the opioid crisis in her home state of Rhode Island. She resigned from her post on Jan. 7, 2021, citing her concerns about the Jan. 6 insurrection on the U.S. Capitol.

As of this writing, President Biden has nominated psychologist Miriam Delphin-Rittmon, PhD, who is commissioner of Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, as mental health czar. I’m glad to see that the new administration wants a new czar, but I would prefer to see a more expansive role for a mental health professional at the federal level. The reason is because

Processing the current crisis

Americans managed to recover emotionally from the ravages of death and dying from World War II; we lived through the “atomic age” of mutual destruction, sometimes calling it the age of anxiety. But nothing has come close to the overwhelming devastation that COVID-19 has brought to the world – and to this country.

A recent Government Accountability Office report shows 38% of U.S. adults reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from April 2020 through February 2021. That was up from 11% from January to June 2019, the report said, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meanwhile, the report cites data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration showing that opioid deaths were 25%-50% higher during the pandemic than a year earlier.

My sense is that people generally have opened up regarding their emotional problems in a freer manner, thus allowing us to speak about and accept mental health problems as part of our human reality – just as we accept physical disorders and search for treatment and care.

In terms of talk therapy, I still believe that the “thinking” therapies, that is, cognitive therapies that involved getting a new perspective on problems, are most effective in dealing with the myriad of emotional issues people experience as well as those that have arisen because of COVID-19, and the tremendous fear of severe illness and death that the virus can bring. Besides anxiety, depression, and fear, the psychological toll of a fractured lifestyle, coupled with social isolation, will lead many into a variety of PTSD-related conditions. Many of those conditions, including PTSD, might lift when COVID-19 is controlled, but the time frame for resolution is far from clear and will vary, depending on each person. National leadership, as well as therapists, need to be ready to work with the many mental health problems COVID-19 will leave in its wake.

Therapeutically, as we develop our cognitive approaches to the problems this pandemic has brought, whether affecting people with no past psychiatric history or those with a previous or ongoing problems, we are in a unique position ourselves to offer even more support based on our own experiences during the pandemic. Our patients have seen us wear masks and work remotely, and just as we know about their suffering, they know we have been affected as well. These shared experiences with patients can allow us to express even greater empathy and offer even greater support – which I believe enhances the cognitive process and adds more humanism to the therapeutic process.

The therapists I’ve talked with believe that sharing coping skills – even generally sharing anxieties – can be very therapeutic. They compared these exchanges to what is done in support or educational groups.

As a psychiatrist who has been treating patients using cognitive-behavioral therapy – the thinking therapy – for more than 40 years, I agree that sharing our experiences in this worldwide pandemic with those we are helping can be extremely beneficial. Using this approach would not distract from other cognitive work. CBT, after all, is a far cry from dynamic or psychoanalytic talking or listening.

Change is in the air. More and more Americans are getting vaccinated, and the CDC is constantly updating its guidance on COVID-19. That guidance should have a mental health component.

I urge the president to put mental health at the forefront by nominating an expert who could offer mental health solutions on a daily basis. This person should be on equal footing with the surgeon general. Taking this step would help destigmatize mental suffering and despair – and create greater awareness about how to address those conditions.

Dr. London has been a practicing psychiatrist for 4 decades and a newspaper columnist for almost as long. He has a private practice in New York and is author of “Find Freedom Fast: Short-Term Therapy That Works” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). Dr. London has no conflicts of interest.

New guidance for those fully vaccinated against COVID-19

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2

There are some important caveats to these updated guidelines. They do not apply to those who have immunocompromising conditions, including those using immunosuppressant agents. They also do not apply to locations subject to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

Those who work or reside in correction or detention facilities and homeless shelters are also still required to test after known exposures. Masking is still required by all travelers on all forms of public transportation into and within the United States.

Most importantly, the guidelines apply only to those who are fully vaccinated. Finally, no vaccine is perfect. As such, anyone who experiences symptoms indicative of COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, should obtain viral testing and isolate themselves from others.1,2

Pros and cons to new guidance

Both sets of updated guidelines are a great example of public health guidance that is changing as the evidence is gathered and changes. This guidance is also a welcome encouragement that the vaccines are effective at decreasing transmission of this virus that has upended our world.

These guidelines leave room for change as evidence is gathered on emerging novel variants. There are, however, a few remaining concerns.

My first concern is for those who are not yet able to be vaccinated, including children under the age of 12. For families with members who are not fully vaccinated, they may have first heard the headlines of “you do not have to mask” to then read the fine print that remains. When truly following these guidelines, many social situations in both the public and private setting should still include both masking and social distancing.

There is no clarity on how these guidelines are enforced. Within the guidance, it is clear that individuals’ privacy is of utmost importance. In the absence of knowledge, that means that the assumption should be that all are not yet vaccinated. Unless there is a way to reliably demonstrate vaccination status, it would likely still be safer to assume that there are individuals who are not fully vaccinated within the setting.

Finally, although this is great news surrounding the efficacy of the vaccine, some are concerned that local mask mandates that have already started to be lifted will be completely removed. As there is still a large portion of the population not yet fully vaccinated, it seems premature for local, state, and territorial authorities to lift these mandates.

How to continue exercising caution

With the outstanding concerns, I will continue to mask in settings, particularly indoors, where I do not definitely know that everyone is vaccinated. I will continue to do this to protect my children and my patients who are not yet vaccinated, and my patients who are immunosuppressed for whom we do not yet have enough information.

I will continue to advise my patients to be thoughtful about the risk for themselves and their families as well.

There has been more benefit to these public health measures then just decreased transmission of COVID-19. I hope that this year has reinforced within us the benefits of masking and self-isolation in the cases of any contagious illnesses.

Although I am looking forward to the opportunities to interact in person with more colleagues and friends, I think we should continue to do this with caution and thoughtfulness. We must be prepared for the possibility of vaccines having decreased efficacy against novel variants as well as eventually the possibility of waning immunity. If these should occur, we need to be prepared for additional recommendation changes and tightening of restrictions.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Public Health Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, May 13, 2021.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 27, 2021.

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2

There are some important caveats to these updated guidelines. They do not apply to those who have immunocompromising conditions, including those using immunosuppressant agents. They also do not apply to locations subject to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

Those who work or reside in correction or detention facilities and homeless shelters are also still required to test after known exposures. Masking is still required by all travelers on all forms of public transportation into and within the United States.

Most importantly, the guidelines apply only to those who are fully vaccinated. Finally, no vaccine is perfect. As such, anyone who experiences symptoms indicative of COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, should obtain viral testing and isolate themselves from others.1,2

Pros and cons to new guidance

Both sets of updated guidelines are a great example of public health guidance that is changing as the evidence is gathered and changes. This guidance is also a welcome encouragement that the vaccines are effective at decreasing transmission of this virus that has upended our world.

These guidelines leave room for change as evidence is gathered on emerging novel variants. There are, however, a few remaining concerns.

My first concern is for those who are not yet able to be vaccinated, including children under the age of 12. For families with members who are not fully vaccinated, they may have first heard the headlines of “you do not have to mask” to then read the fine print that remains. When truly following these guidelines, many social situations in both the public and private setting should still include both masking and social distancing.

There is no clarity on how these guidelines are enforced. Within the guidance, it is clear that individuals’ privacy is of utmost importance. In the absence of knowledge, that means that the assumption should be that all are not yet vaccinated. Unless there is a way to reliably demonstrate vaccination status, it would likely still be safer to assume that there are individuals who are not fully vaccinated within the setting.

Finally, although this is great news surrounding the efficacy of the vaccine, some are concerned that local mask mandates that have already started to be lifted will be completely removed. As there is still a large portion of the population not yet fully vaccinated, it seems premature for local, state, and territorial authorities to lift these mandates.

How to continue exercising caution

With the outstanding concerns, I will continue to mask in settings, particularly indoors, where I do not definitely know that everyone is vaccinated. I will continue to do this to protect my children and my patients who are not yet vaccinated, and my patients who are immunosuppressed for whom we do not yet have enough information.

I will continue to advise my patients to be thoughtful about the risk for themselves and their families as well.

There has been more benefit to these public health measures then just decreased transmission of COVID-19. I hope that this year has reinforced within us the benefits of masking and self-isolation in the cases of any contagious illnesses.

Although I am looking forward to the opportunities to interact in person with more colleagues and friends, I think we should continue to do this with caution and thoughtfulness. We must be prepared for the possibility of vaccines having decreased efficacy against novel variants as well as eventually the possibility of waning immunity. If these should occur, we need to be prepared for additional recommendation changes and tightening of restrictions.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Public Health Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, May 13, 2021.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 27, 2021.

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2

There are some important caveats to these updated guidelines. They do not apply to those who have immunocompromising conditions, including those using immunosuppressant agents. They also do not apply to locations subject to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

Those who work or reside in correction or detention facilities and homeless shelters are also still required to test after known exposures. Masking is still required by all travelers on all forms of public transportation into and within the United States.

Most importantly, the guidelines apply only to those who are fully vaccinated. Finally, no vaccine is perfect. As such, anyone who experiences symptoms indicative of COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, should obtain viral testing and isolate themselves from others.1,2

Pros and cons to new guidance

Both sets of updated guidelines are a great example of public health guidance that is changing as the evidence is gathered and changes. This guidance is also a welcome encouragement that the vaccines are effective at decreasing transmission of this virus that has upended our world.

These guidelines leave room for change as evidence is gathered on emerging novel variants. There are, however, a few remaining concerns.

My first concern is for those who are not yet able to be vaccinated, including children under the age of 12. For families with members who are not fully vaccinated, they may have first heard the headlines of “you do not have to mask” to then read the fine print that remains. When truly following these guidelines, many social situations in both the public and private setting should still include both masking and social distancing.

There is no clarity on how these guidelines are enforced. Within the guidance, it is clear that individuals’ privacy is of utmost importance. In the absence of knowledge, that means that the assumption should be that all are not yet vaccinated. Unless there is a way to reliably demonstrate vaccination status, it would likely still be safer to assume that there are individuals who are not fully vaccinated within the setting.

Finally, although this is great news surrounding the efficacy of the vaccine, some are concerned that local mask mandates that have already started to be lifted will be completely removed. As there is still a large portion of the population not yet fully vaccinated, it seems premature for local, state, and territorial authorities to lift these mandates.

How to continue exercising caution

With the outstanding concerns, I will continue to mask in settings, particularly indoors, where I do not definitely know that everyone is vaccinated. I will continue to do this to protect my children and my patients who are not yet vaccinated, and my patients who are immunosuppressed for whom we do not yet have enough information.

I will continue to advise my patients to be thoughtful about the risk for themselves and their families as well.

There has been more benefit to these public health measures then just decreased transmission of COVID-19. I hope that this year has reinforced within us the benefits of masking and self-isolation in the cases of any contagious illnesses.

Although I am looking forward to the opportunities to interact in person with more colleagues and friends, I think we should continue to do this with caution and thoughtfulness. We must be prepared for the possibility of vaccines having decreased efficacy against novel variants as well as eventually the possibility of waning immunity. If these should occur, we need to be prepared for additional recommendation changes and tightening of restrictions.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at [email protected].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Public Health Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, May 13, 2021.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 27, 2021.

COVID-19 in children: Weekly cases drop to 6-month low

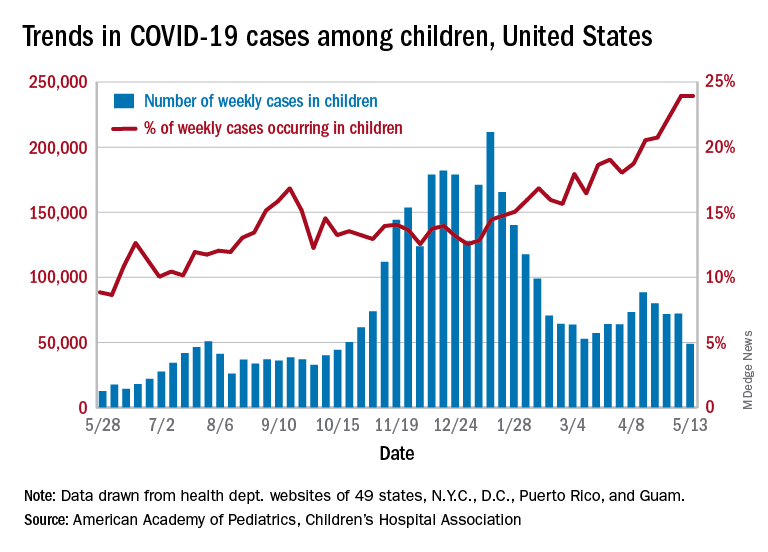

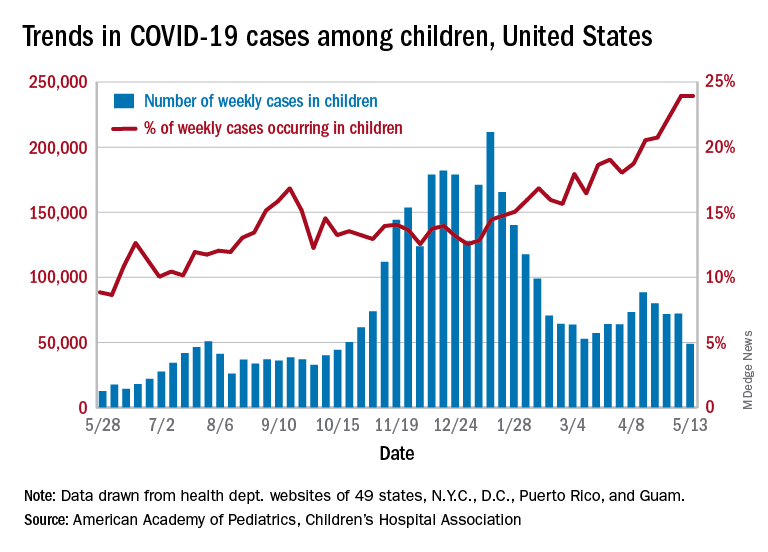

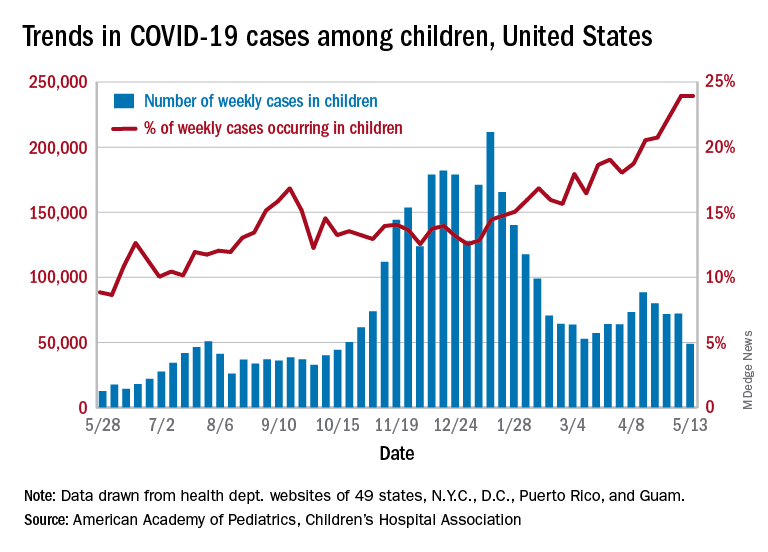

Just 1 week after it looked like the COVID-19 situation in children might be taking another turn for the worse, the number of new pediatric cases dropped to its lowest level since October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. During the week of April 30 to May 6 – the same week Rhode Island reported a large backlog of cases and increased its total by 30% – the number of new cases went up slightly after 2 weeks of declines.

Other positive indicators come in the form of the proportion of cases occurring in children. The cumulative percentage of cases in children since the start of the pandemic remained at 14.0% for a second consecutive week, and the proportion of new cases in children held at 24.0% and did not increase for the first time in 6 weeks, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of child COVID-19 cases reported in these jurisdictions is now up to 3.9 million, for a cumulative rate of 5,187 cases per 100,000 children in the United States. Among the states, total counts range from a low of 4,070 in Hawaii to 475,619 in California. Hawaii also has the lowest rate at 1,357 per 100,000 children, while the highest, 9,778 per 100,000, can be found in Rhode Island, the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children continue to accumulate at a relatively slow pace, with two more added during the week of May 7-13, bringing the total to 308 for the entire pandemic in 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children’s share of the mortality burden is currently 0.06%, a figure that has not changed since mid-December, and the death rate for children with COVID-19 is 0.01%, according to the report.

Almost two-thirds (65%) of all deaths have occurred in just nine states – Arizona (31), California (21), Colorado (13), Georgia (10), Illinois (18), Maryland (10), Pennsylvania (10), Tennessee (10), and Texas (52) – and New York City (24), while eight states have not reported any deaths yet, the two groups said.

Just 1 week after it looked like the COVID-19 situation in children might be taking another turn for the worse, the number of new pediatric cases dropped to its lowest level since October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. During the week of April 30 to May 6 – the same week Rhode Island reported a large backlog of cases and increased its total by 30% – the number of new cases went up slightly after 2 weeks of declines.

Other positive indicators come in the form of the proportion of cases occurring in children. The cumulative percentage of cases in children since the start of the pandemic remained at 14.0% for a second consecutive week, and the proportion of new cases in children held at 24.0% and did not increase for the first time in 6 weeks, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of child COVID-19 cases reported in these jurisdictions is now up to 3.9 million, for a cumulative rate of 5,187 cases per 100,000 children in the United States. Among the states, total counts range from a low of 4,070 in Hawaii to 475,619 in California. Hawaii also has the lowest rate at 1,357 per 100,000 children, while the highest, 9,778 per 100,000, can be found in Rhode Island, the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children continue to accumulate at a relatively slow pace, with two more added during the week of May 7-13, bringing the total to 308 for the entire pandemic in 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children’s share of the mortality burden is currently 0.06%, a figure that has not changed since mid-December, and the death rate for children with COVID-19 is 0.01%, according to the report.

Almost two-thirds (65%) of all deaths have occurred in just nine states – Arizona (31), California (21), Colorado (13), Georgia (10), Illinois (18), Maryland (10), Pennsylvania (10), Tennessee (10), and Texas (52) – and New York City (24), while eight states have not reported any deaths yet, the two groups said.

Just 1 week after it looked like the COVID-19 situation in children might be taking another turn for the worse, the number of new pediatric cases dropped to its lowest level since October, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. During the week of April 30 to May 6 – the same week Rhode Island reported a large backlog of cases and increased its total by 30% – the number of new cases went up slightly after 2 weeks of declines.

Other positive indicators come in the form of the proportion of cases occurring in children. The cumulative percentage of cases in children since the start of the pandemic remained at 14.0% for a second consecutive week, and the proportion of new cases in children held at 24.0% and did not increase for the first time in 6 weeks, based on data from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The total number of child COVID-19 cases reported in these jurisdictions is now up to 3.9 million, for a cumulative rate of 5,187 cases per 100,000 children in the United States. Among the states, total counts range from a low of 4,070 in Hawaii to 475,619 in California. Hawaii also has the lowest rate at 1,357 per 100,000 children, while the highest, 9,778 per 100,000, can be found in Rhode Island, the AAP and CHA said.

Deaths in children continue to accumulate at a relatively slow pace, with two more added during the week of May 7-13, bringing the total to 308 for the entire pandemic in 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children’s share of the mortality burden is currently 0.06%, a figure that has not changed since mid-December, and the death rate for children with COVID-19 is 0.01%, according to the report.

Almost two-thirds (65%) of all deaths have occurred in just nine states – Arizona (31), California (21), Colorado (13), Georgia (10), Illinois (18), Maryland (10), Pennsylvania (10), Tennessee (10), and Texas (52) – and New York City (24), while eight states have not reported any deaths yet, the two groups said.

Dr. Fauci: Extraordinary challenges, scientific triumphs with COVID-19

“Vaccines have been the bright light of this extraordinary challenge that we’ve gone through,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

In an address for the opening ceremony of the American Thoracic Society’s virtual international conference, Dr. Fauci emphasized the role of basic and clinical research and government support for science in helping turn the tide of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“A few weeks ago, I wrote an editorial in Science, because there was some misunderstanding about how and why we were able to go from a realization of a new pathogen in January of 2020, to getting doses of vaccines in the arms of individuals – a highly efficacious vaccine – 11 months later. Truly, an unprecedented accomplishment,” he said.

“But as I said in the editorial, the speed and efficiency with which these highly efficacious vaccines were developed, and their potential for saving millions of lives, are due to an extraordinary multidisciplinary effort, involving basic, preclinical, and clinical science that had been underway – out of the spotlight – for decades and decades before the unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic, a fact that very few people really appreciate: namely, the importance of investment in biomedical research.”

The general addresses the troops

Perhaps no other audience is so well suited to receive Dr. Fauci’s speech as those who are currently attending (virtually) the ATS conference, including researchers who scrutinize the virus from every angle to describe its workings and identify its vulnerabilities, epidemiologists who study viral transmission and look for ways to thwart it, public health workers who fan out to communities across the country to push vaccine acceptance, and clinicians who specialize in critical care and pulmonary medicine, many of whom staff the respiratory floors and intensive care units where the most severely ill patients are treated.

Speaking about the lessons learned and challenges remaining from the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Fauci briefly reviewed the epidemiology, virology and transmission, diagnostics, and clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infections and the therapeutics and vaccines for COVID-19.

Epidemiology

The pandemic began in December 2019 with recognition of a novel type of pneumonia in the Wuhan District of Central China, Dr. Fauci noted.

“Very quickly thereafter, in the first week of January 2020, the Chinese identified a new strain of coronavirus as [the] source of the outbreak. Fast forward to where we are right now: We have experienced and are experiencing the most devastating pandemic of a respiratory illness in the last 102 years, with already approximately 160 million individuals having been infected – and this is clearly a gross undercounting – and also 3.3 million deaths, again, very likely an undercounting,” he said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of May 9, 2021, there were approximately 32.5 million cases of COVID-19 and 578,520 deaths in the United States. Those cases and deaths occurred largely in three surges in the United States, in early spring, early summer, and late fall of 2020.

Virology and transmission

SARS-CoV-2 is a beta-coronavirus in the same subgenus as SARS-CoV-1 and some bat coronaviruses, Dr. Fauci explained. The viral genome is large, about 30,000 kilobases, and it has four structural proteins, most importantly the S or “spike” protein that allows the virus to attach to and fuse with cell membranes by binding to the ACE2 receptor on tissues in the upper and lower respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, cardiovascular system, and other organ systems.

The virus is transmitted mainly through exposure to respiratory droplets within 6 feet of an infected person, or sometimes through droplets or particles that remain in the air over time and various distances.

Contact with contaminated surfaces, once feared as a means of transmission, is now understood to be less common.

The virus has been detected in stool, blood, semen, and ocular secretions, although the role of transmission through these sources is still unknown.

“Some very interesting characteristics of this virus, really quite unique compared to other viruses, certainly other respiratory viruses, is [that] about a third to 40% of people who are infected never develop any symptoms,” Dr. Fauci said. “Importantly, and very problematic to what we do to contain it – particularly with regard to identification, isolation, and contract tracing – between 50% and 60% of the transmissions occur either from someone who will never develop symptoms, or someone in the presymptomatic phase of disease.”

The fundamentals of preventing acquisition and transmission are as familiar to most Americans now as the Pledge of Allegiance: universal mask wearing, physical distancing, avoiding crowds and congregate settings, preference for outdoor over indoor settings, and frequent hand washing, he noted.

Diagnostics