User login

Pediatricians see drop in income during the pandemic

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

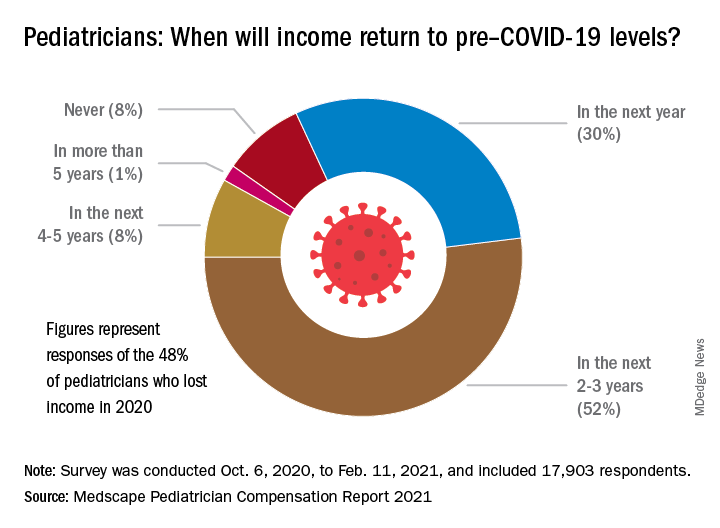

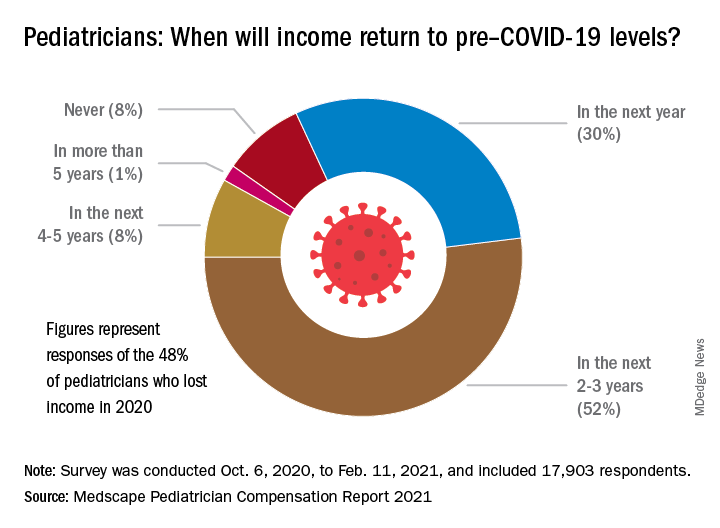

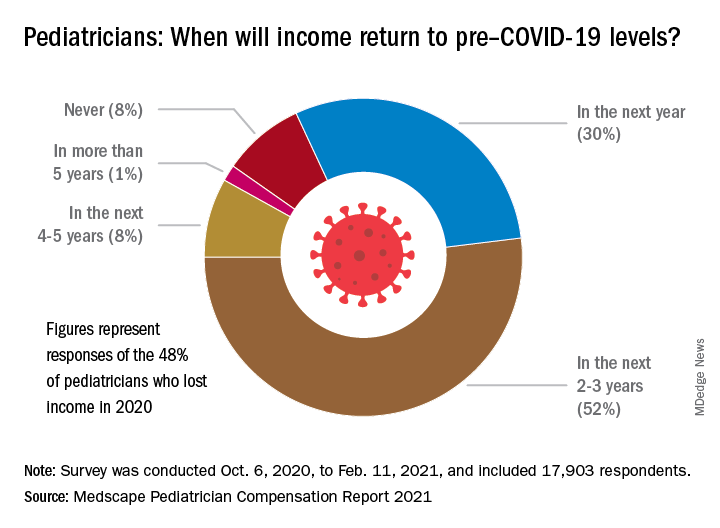

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

The average income for pediatricians declined slightly from 2019 to 2020, according to the Medscape Pediatrician Compensation Report 2021.

The report, which was conducted between October 2020 and February 2021, found that the average pediatrician income was down $11,000 – from $232,000 in 2019 to $221,000 in 2020, with 48% of pediatricians reporting at least some decline in compensation.

The specialty also earned the least amount of money in 2020, compared with all of the other specialties, which isn’t surprising since pediatricians have been among the lowest-paid physician specialties since 2013. The highest-earning specialty was plastic surgery with an average income of $526,000 annually.

Most pediatricians who saw a drop in income cited pandemic-related issues such as job loss, fewer hours, and fewer patients.

Jesse Hackell, MD, vice president and chief operating officer of Ponoma Pediatrics in New York, said in an interview the reduced wages pediatricians saw in 2020 didn’t surprise him because many pediatric offices saw a huge drop in visits that were not urgent.

“[The report] shows that procedural specialties tended to do a lot better than the nonprocedural specialties,” Dr. Hackell said. “That’s because, during the shutdown, if you broke your leg, you still needed the orthopedist. And even though the hospitals weren’t doing elective surgeries, they were certainly doing the emergency stuff.”

Meanwhile, in pediatrician offices, where Dr. Hackell said office visits dropped 70%-80% at the beginning of the pandemic, “parents weren’t going to bring a healthy kid out for routine visits and they weren’t going to bring a kid out for minor illnesses and expose them to possibly communicable diseases in the office.”

About 52% of pediatricians who lost income because of the pandemic believe their income levels will return to normal in 2-3 years. Meanwhile 30% of pediatricians expect their income to return to normal within a year, and 8% believe it will take 4 years for them to bounce back.

Physician work hours generally declined for some time during the pandemic, according to the report. However, most pediatricians are working about the same number of hours as they did before the pandemic, which is 47 hours per week.

Despite working the same number of hours per week that they did prepandemic, they are seeing fewer patients. They are currently seeing on average 64 patients per week, compared with the 78 patients they used to see weekly before the pandemic.

Dr. Hackell said that might be because pediatric offices are trying to make up the loss of revenue during the beginning of the pandemic, from the reduced number of well visits and immunizations, in the second half of the year with outreach.

“Since about June 2020, we’ve been making concerted efforts to remind parents that preventing other infectious diseases is critically important,” Dr. Hackell explained. “And so actually, for the second half of the year, many of us saw more well visits and immunization volume than in 2019 as we sought to make up the gap. It wasn’t that we were seeing more overall, but we’re trying to make up the gap that happened from March, April, May, [and] June.”

Most pediatricians find their work rewarding. One-third say the most rewarding part of their job is gratitude from and relationships with their patients. Meanwhile, 31% of pediatricians said knowing they are making the world a better place was a rewarding part of their job. Only 8% of them said making money was a rewarding part of their job.

Dr. Hackell said he did not go into pediatrics to make money, it was because he found it stimulating and has “no complaints.”

“I’ve been a pediatrician for 40 years and I wouldn’t do anything else,” Dr. Hackell said. “I don’t know that there’s anything that I would find as rewarding as the relationships that I’ve had over 40 years with my patients. You know, getting invited to weddings of kids who I saw when they were newborns is pretty impressive. It’s the gratification of having ongoing relationships with families.”

Furthermore, the report revealed that 77% of pediatricians said they would pick medicine again if they had a choice, and 82% said they would choose the same specialty.

The experts disclosed no relevant financial interests.

*This story was updated on 5/18/2021.

Patients with CLL have significantly reduced response to COVID-19 vaccine

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) have increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease as well as mortality.

Such patients are likely to have compromised immune systems, making them respond poorly to vaccines, as has been seen in studies involving pneumococcal, hepatitis B, and influenza A and B vaccination.

In order to determine if vaccination against COVID-19 disease will be effective among these patients, researchers performed a study to determine the efficacy of a single COVID-19 vaccine in patients with CLL. They found that the response rate of patients with CLL to vaccination was significantly lower than that of healthy controls, according to the study published in Blood Advances.

Study details

The study (NCT04746092) assessed the humoral immune responses to BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (Pfizer) vaccination in adult patients with CLL and compared responses with those obtained in age-matched healthy controls. Patients received two vaccine doses, 21 days apart, and antibody titers were measured 2-3 weeks after administration of the second dose, according to Yair Herishanu, MD, of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv University, and colleagues.

Troubling results

The researchers found an antibody-mediated response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in only 66 of 167 (39.5%) of all patients with CLL. The response rate of 52 of these responding patients with CLL to the vaccine was significantly lower than that occurring in 52 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (52% vs. 100%, respectively; adjusted odds ratio, 0.010; 95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.162; P < .001).

Among the patients with CLL, the response rate was highest in those who obtained clinical remission after treatment (79.2%), followed by 55.2% in treatment-naive patients, and it was only 16% in patients under treatment at the time of vaccination.

In patients treated with either BTK inhibitors or venetoclax with and without anti-CD20 antibody, response rates were low (16.0% and 13.6%, respectively). In particular, none of the patients exposed to anti-CD20 antibodies less than 12 months prior to vaccination responded, according to the researchers.

Multivariate analysis showed that the independent predictors of a vaccine response were age (65 years or younger; odds ratio, 3.17; P = .025), sex (women; OR, 3.66; P = .006), lack of active therapy (including treatment naive and previously treated patients; OR 6.59; P < .001), IgG levels 550 mg/dL or greater (OR, 3.70; P = .037), and IgM levels 40mg/dL or greater (OR, 2.92; P = .017).

Within a median follow-up period of 75 days since the first vaccine dose, none of the CLL patients developed COVID-19 infection, the researchers reported.

“Vaccinated patients with CLL should continue to adhere to masking, social distancing, and vaccination of their close contacts should be strongly recommended. Serological tests after the second injection of the COVID-19 vaccine can provide valuable information to the individual patient and perhaps, may be integrated in future clinical decisions,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) have increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease as well as mortality.

Such patients are likely to have compromised immune systems, making them respond poorly to vaccines, as has been seen in studies involving pneumococcal, hepatitis B, and influenza A and B vaccination.

In order to determine if vaccination against COVID-19 disease will be effective among these patients, researchers performed a study to determine the efficacy of a single COVID-19 vaccine in patients with CLL. They found that the response rate of patients with CLL to vaccination was significantly lower than that of healthy controls, according to the study published in Blood Advances.

Study details

The study (NCT04746092) assessed the humoral immune responses to BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (Pfizer) vaccination in adult patients with CLL and compared responses with those obtained in age-matched healthy controls. Patients received two vaccine doses, 21 days apart, and antibody titers were measured 2-3 weeks after administration of the second dose, according to Yair Herishanu, MD, of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv University, and colleagues.

Troubling results

The researchers found an antibody-mediated response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in only 66 of 167 (39.5%) of all patients with CLL. The response rate of 52 of these responding patients with CLL to the vaccine was significantly lower than that occurring in 52 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (52% vs. 100%, respectively; adjusted odds ratio, 0.010; 95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.162; P < .001).

Among the patients with CLL, the response rate was highest in those who obtained clinical remission after treatment (79.2%), followed by 55.2% in treatment-naive patients, and it was only 16% in patients under treatment at the time of vaccination.

In patients treated with either BTK inhibitors or venetoclax with and without anti-CD20 antibody, response rates were low (16.0% and 13.6%, respectively). In particular, none of the patients exposed to anti-CD20 antibodies less than 12 months prior to vaccination responded, according to the researchers.

Multivariate analysis showed that the independent predictors of a vaccine response were age (65 years or younger; odds ratio, 3.17; P = .025), sex (women; OR, 3.66; P = .006), lack of active therapy (including treatment naive and previously treated patients; OR 6.59; P < .001), IgG levels 550 mg/dL or greater (OR, 3.70; P = .037), and IgM levels 40mg/dL or greater (OR, 2.92; P = .017).

Within a median follow-up period of 75 days since the first vaccine dose, none of the CLL patients developed COVID-19 infection, the researchers reported.

“Vaccinated patients with CLL should continue to adhere to masking, social distancing, and vaccination of their close contacts should be strongly recommended. Serological tests after the second injection of the COVID-19 vaccine can provide valuable information to the individual patient and perhaps, may be integrated in future clinical decisions,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) have increased risk for severe COVID-19 disease as well as mortality.

Such patients are likely to have compromised immune systems, making them respond poorly to vaccines, as has been seen in studies involving pneumococcal, hepatitis B, and influenza A and B vaccination.

In order to determine if vaccination against COVID-19 disease will be effective among these patients, researchers performed a study to determine the efficacy of a single COVID-19 vaccine in patients with CLL. They found that the response rate of patients with CLL to vaccination was significantly lower than that of healthy controls, according to the study published in Blood Advances.

Study details

The study (NCT04746092) assessed the humoral immune responses to BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (Pfizer) vaccination in adult patients with CLL and compared responses with those obtained in age-matched healthy controls. Patients received two vaccine doses, 21 days apart, and antibody titers were measured 2-3 weeks after administration of the second dose, according to Yair Herishanu, MD, of the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv University, and colleagues.

Troubling results

The researchers found an antibody-mediated response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in only 66 of 167 (39.5%) of all patients with CLL. The response rate of 52 of these responding patients with CLL to the vaccine was significantly lower than that occurring in 52 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (52% vs. 100%, respectively; adjusted odds ratio, 0.010; 95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.162; P < .001).

Among the patients with CLL, the response rate was highest in those who obtained clinical remission after treatment (79.2%), followed by 55.2% in treatment-naive patients, and it was only 16% in patients under treatment at the time of vaccination.

In patients treated with either BTK inhibitors or venetoclax with and without anti-CD20 antibody, response rates were low (16.0% and 13.6%, respectively). In particular, none of the patients exposed to anti-CD20 antibodies less than 12 months prior to vaccination responded, according to the researchers.

Multivariate analysis showed that the independent predictors of a vaccine response were age (65 years or younger; odds ratio, 3.17; P = .025), sex (women; OR, 3.66; P = .006), lack of active therapy (including treatment naive and previously treated patients; OR 6.59; P < .001), IgG levels 550 mg/dL or greater (OR, 3.70; P = .037), and IgM levels 40mg/dL or greater (OR, 2.92; P = .017).

Within a median follow-up period of 75 days since the first vaccine dose, none of the CLL patients developed COVID-19 infection, the researchers reported.

“Vaccinated patients with CLL should continue to adhere to masking, social distancing, and vaccination of their close contacts should be strongly recommended. Serological tests after the second injection of the COVID-19 vaccine can provide valuable information to the individual patient and perhaps, may be integrated in future clinical decisions,” the researchers concluded.

The study was sponsored by the Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

How to improve our response to COVID’s mental tolls

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We have no way of precisely knowing how many lives might have been saved, and how much grief and loneliness spared and economic ruin contained during COVID-19 if we had risen to its myriad challenges in a timely fashion. However, I feel we can safely say that the United States deserves to be graded with an “F” for its management of the pandemic.

To render this grade, we need only to read the countless verified reports of how critically needed public health measures were not taken soon enough, or sufficiently, to substantially mitigate human and societal suffering.

This began with the failure to protect doctors, nurses, and technicians, who did not have the personal protective equipment needed to prevent infection and spare risk to their loved ones. It soon extended to the country’s failure to adequately protect all its citizens and residents. COVID-19 then rained its grievous consequences disproportionately upon people of color, those living in poverty, and those with housing and food insecurity – those already greatly foreclosed from opportunities to exit from their circumstances.

We all have heard, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

Bear witness, colleagues and friends: It will be our shared shame if we too continue to fail in our response to COVID-19. But failure need not happen because protecting ourselves and our country is a solvable problem; complex and demanding for sure, but solvable.

To battle trauma, we must first define it

The sine qua non of a disaster is its psychic and social trauma. I asked Maureen Sayres Van Niel, MD, chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Minority and Underrepresented Caucus and a former steering committee member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, to define trauma. She said, “It is [the product of] a catastrophic, unexpected event over which we have little control, with grave consequences to the lives and psychological functioning of those individuals and groups affected.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massively amplified traumatic event because of the virulence and contagious properties of the virus and its variants; the absence of end date on the horizon; its effect as a proverbial ax that disproportionately falls on the majority of the populace experiencing racial and social inequities; and the ironic yet necessary imperative to distance ourselves from those we care about and who care about us.

Four interdependent factors drive the magnitude of the traumatic impact of a disaster: the degree of exposure to the life-threatening event; the duration and threat of recurrence; an individual’s preexisting (natural and human-made) trauma and mental and addictive disorders; and the adequacy of family and fundamental resources such as housing, food, safety, and access to health care (the social dimensions of health and mental health). These factors underline the “who,” “what,” “where,” and “how” of what should have been (and continue to be) an effective public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet existing categories that we have used to predict risk for trauma no longer hold. The gravity, prevalence, and persistence of COVID-19’s horrors erase any differences among victims, witnesses, and bystanders. Dr Sayres Van Niel asserts that we have a “collective, national trauma.” In April, the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Vaccine Monitor reported that 24% of U.S. adults had a close friend or family member who died of COVID-19. That’s 82 million Americans! Our country has eclipsed individual victimization and trauma because we are all in its maw.

Vital lessons from the past

In a previous column, I described my role as New York City’s mental health commissioner after 9/11 and the many lessons we learned during that multiyear process. Our work served as a template for other disasters to follow, such as Hurricane Sandy. Its value to COVID-19 is equally apparent.

We learned that those most at risk of developing symptomatic, functionally impairing mental illness had prior traumatic experiences (for example, from childhood abuse or neglect, violence, war, and forced displacement from their native land) and/or a preexisting mental or substance use disorder.

Once these individuals and communities were identified, we could prioritize their treatment and care. Doing so required mobilizing both inner and external (social) resources, which can be used before disaster strikes or in its wake.

For individuals, adaptive resources include developing any of a number of mind-body activities (for example, meditation, mindfulness, slow breathing, and yoga); sufficient but not necessarily excessive levels of exercise (as has been said, if exercise were a pill, it would be the most potent of medicines); nourishing diets; sleep, nature’s restorative state; and perhaps most important, attachment and human connection to people who care about you and whom you care about and trust.

This does not necessarily mean holding or following an institutional religion or belonging to house of worship (though, of course, that melds and augments faith with community). For a great many, myself included, there is spirituality, the belief in a greater power, which need not be a God yet instills a sense of the vastness, universality, and continuity of life.

For communities, adaptive resources include safe homes and neighborhoods; diminishing housing and food insecurity; education, including pre-K; employment, with a livable wage; ridding human interactions of the endless, so-called microaggressions (which are not micro at all, because they accrue) of race, ethnic, class, and age discrimination and injustice; and ready access to quality and affordable health care, now more than ever for the rising tide of mental and substance use disorders that COVID-19 has unleashed.

Every gain we make to ablate racism, social injustice, discrimination, and widely and deeply spread resource and opportunity inequities means more cohesion among the members of our collective tribe. Greater cohesion, a love for thy neighbor, and equity (in action, not polemics) will fuel the resilience we will need to withstand more of COVID-19’s ongoing trauma; that of other, inescapable disasters and losses; and the wear and tear of everyday life. The rewards of equity are priceless and include the dignity that derives from fairness and justice – given and received.

An unprecedented disaster requires a bold response

My, what a list. But to me, the encompassing nature of what’s needed means that we can make differences anywhere, everywhere, and in countless and continuous ways.

The measure of any society is in how it cares for those who are foreclosed, through no fault of their own, from what we all want: a life safe from violence, secure in housing and food, with loving relationships and the pride that comes of making contributions, each in our own, wonderfully unique way.

Where will we all be in a year, 2, or 3 from now? Prepared, or not? Emotionally inoculated, or not? Better equipped, or not? As divided, or more cohesive?

Well, I imagine that depends on each and every one of us.

Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, is a psychiatrist, public health doctor, and writer. He is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Public Health, director of Columbia Psychiatry Media, chief medical officer of Bongo Media, and chair of the advisory board of Get Help. He has been chief medical officer of McLean Hospital, a Harvard teaching hospital; mental health commissioner of New York City (in the Bloomberg administration); and chief medical officer of the New York State Office of Mental Health, the nation’s largest state mental health agency.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among asymptomatic, 2% may harbor 90% of community’s viral load: Study

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About 2% of asymptomatic college students carried 90% of COVID-19 viral load levels on a Colorado campus last year, new research reveals. Furthermore, the viral loads in these students were as elevated as those seen in hospitalized patients.

“College campuses were one of the few places where people without any symptoms or suspicions of exposure were being screened for the virus. This allowed us to make some powerful comparisons between symptomatic vs healthy carriers of the virus,” senior study author Sara Sawyer, PhD, professor of virology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in an interview.

“It turns out, walking around a college campus can be as dangerous as walking through a COVID ward in the hospital, in that you will experience these viral ‘super carriers’ equally in both settings,” she said.

“This is an important study in advancing our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 is distributed in the population,” Thomas Giordano, MD, MPH, professor and section chief of infectious diseases at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

The study “adds to the evidence that viral load is not too tightly correlated with symptoms.” In fact, Dr. Giordano added, “this study suggests viral load is not at all correlated with symptoms.”

Viral load may not be correlated with transmissibility either, said Raphael Viscidi, MD, when asked to comment. “This is not a transmissibility study. They did not show that viral load is the factor related to transmission.”

“It’s true that 2% of the population they studied carried 90% of the virus, but it does not establish any biological importance to that 2%,” added Dr. Viscidi, professor of pediatrics and oncology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore,.

The 2% could just be the upper tail end of a normal bell-shaped distribution curve, Dr. Viscidi said, or there could be something biologically unique about that group. But the study does not make that distinction, he said.

The study was published online May 10, 2021, in PNAS, the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences.

A similar picture in hospitalized patients

Out of more than 72,500 saliva samples taken during COVID-19 screening at the University of Colorado Boulder between Aug. 27 and Dec. 11, 2020, 1,405 were positive for SARS-CoV-2.

The investigators also compared viral loads from students with those of hospitalized patients based on published data. They found the distribution of viral loads between these groups “indistinguishable.”

“Strikingly, these datasets demonstrate dramatic differences in viral levels between individuals, with a very small minority of the infected individuals harboring the vast majority of the infectious virions,” the researchers wrote. The comparison “really represents two extremes: One group is mostly hospitalized, while the other group represents a mostly young and healthy (but infected) college population.”

“It would be interesting to adjust public health recommendations based on a person’s viral load,” Dr. Giordano said. “One could speculate that a person with a very high viral load could be isolated longer or more thoroughly, while someone with a very low viral load could be minimally isolated.

“This is speculation, and more data are needed to test this concept,” he added. Also, quantitative viral load testing would need to be standardized before it could be used to guide such decision-making

Preceding the COVID-19 vaccine era

It should be noted that the research was conducted in fall 2020, before access to COVID-19 immunization.

“The study was performed prior to vaccine availability in a cohort of young people. It adds further data to support prior observations that the majority of infections are spread by a much smaller group of individuals,” David Hirschwerk, MD, said in an interview.

“Now that vaccines are available, I think it is very likely that a repeat study of this type would show diminished transmission from vaccinated people who were infected yet asymptomatic,” added Dr. Hirschwerk, an infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., who was not affiliated with the research.

Mechanism still a mystery

“This finding has been in the literature in piecemeal fashion since the beginning of the pandemic,” Dr. Sawyer said. “I just think we were the first to realize the bigger implications of these plots of viral load that we have all been seeing over and over again.”

How a minority of people walk around asymptomatic with a majority of virus remains unanswered. Are there special people who can harbor these extremely high viral loads? Or do many infected individuals experience a short period of time when they carry such elevated levels?

The highest observed viral load in the current study was more than 6 trillion virions per mL. “It is remarkable to consider that this individual was on campus and reported no symptoms at our testing site,” the researchers wrote.

In contrast, the lowest viral load detected was 8 virions per mL.

Although more research is needed, the investigators noted that “a strong implication is that these individuals who are viral ‘super carriers’ may also be ‘superspreaders.’ ”

Some of the study authors have financial ties to companies that offer commercial SARS-CoV-2 testing, including Darwin Biosciences, TUMI Genomics, Faze Medicines, and Arpeggio Biosciences.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Who is my neighbor? The ethics of sharing medical resources in the world

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.

Modern medical technology has created treatments that cost $10,000 a month to add a few extra months of life to geriatric patients with terminal cancer. Meanwhile, in more mundane care, efforts like Choosing Wisely seek to save money wasted on low-value, useless, and even harmful tests and therapies. There is no single person or agency managing this chaotic process of inventing expensive new technologies while inadequately addressing the widespread shortages of mental health care, disparities in education, and other social determinants of health. The pandemic has highlighted these preexisting weaknesses in the social fabric.

The cries from India have been accompanied by voices of anger from India and other nations accusing the United States of hoarding vaccines and the raw materials needed to produce them. This has been called vaccine apartheid. The United States is not alone in its political decision to prioritize domestic interests over international ones; India’s recent government is similarly nationalistic. Scientists warn that no one is safe locally as long as the pandemic rages in other countries. The Biden administration, in a delayed response to the crisis in India, finally announced plans to share some unused vaccines (of a brand not yet Food and Drug Administration approved) as well as some vaccine raw materials whose export was forbidden by a regulation under the Defense Production Act. Reading below the headlines, the promised response won’t be implemented for weeks or months. We must do better.

The logistics of sharing the benefits of advanced science are complicated. The ethics are not. Who is my neighbor? If you didn’t learn the answer to that in Sunday school, there isn’t much more I can say.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures, Email him at [email protected]

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.

Modern medical technology has created treatments that cost $10,000 a month to add a few extra months of life to geriatric patients with terminal cancer. Meanwhile, in more mundane care, efforts like Choosing Wisely seek to save money wasted on low-value, useless, and even harmful tests and therapies. There is no single person or agency managing this chaotic process of inventing expensive new technologies while inadequately addressing the widespread shortages of mental health care, disparities in education, and other social determinants of health. The pandemic has highlighted these preexisting weaknesses in the social fabric.

The cries from India have been accompanied by voices of anger from India and other nations accusing the United States of hoarding vaccines and the raw materials needed to produce them. This has been called vaccine apartheid. The United States is not alone in its political decision to prioritize domestic interests over international ones; India’s recent government is similarly nationalistic. Scientists warn that no one is safe locally as long as the pandemic rages in other countries. The Biden administration, in a delayed response to the crisis in India, finally announced plans to share some unused vaccines (of a brand not yet Food and Drug Administration approved) as well as some vaccine raw materials whose export was forbidden by a regulation under the Defense Production Act. Reading below the headlines, the promised response won’t be implemented for weeks or months. We must do better.

The logistics of sharing the benefits of advanced science are complicated. The ethics are not. Who is my neighbor? If you didn’t learn the answer to that in Sunday school, there isn’t much more I can say.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no financial disclosures, Email him at [email protected]

India is in a crisis as the burden of COVID-19 has collapsed parts of the health care system. There are not enough beds, not enough oxygen, and not enough crematoria to handle the pandemic. India is also a major supplier of vaccines for itself and many other countries. That production capacity has also been affected by the local events, further worsening the response to the pandemic over the next few months.

This collapse is the specter that, in April 2020, placed a hospital ship next to Manhattan and rows of beds in its convention center. Fortunately, the lockdown in March 2020 sufficiently flattened the curve. The city avoided utilizing that disaster capacity, though many New Yorkers died out of sight in nursing homes. When the third and largest wave of cases in the United States peaked in January 2021, hospitals throughout California reached capacity but avoided bursting. In April 2021, localized outbreaks in Michigan, Arizona, and Ontario again tested the maximum capacity for providing modern medical treatments. Great Britain used a second lockdown in October 2020 and a third in January 2021 to control the pandemic, with Prime Minister Boris Johnson emphasizing that it was these social interventions, and not vaccines, which provided the mitigating effects. Other European Union nations adopted similar strategies. Prudent choices by government guided by science, combined with the cooperation of the public, have been and still are crucial to mollify the pandemic.

There is hope that soon vaccines will return daily life to a new normal. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has loosened restrictions on social gathering. An increase in daily new cases of COVID-19 in April 2021 has turned into just a blip before continuing to recede. Perhaps that is the first sign of vaccination working at the level of public health. However, the May 2021 lockdown in highly vaccinated Seychelles is a warning that the danger remains. A single match can start a huge forest fire. The first 150 million cases of COVID-19 worldwide have, through natural rates of mutation, produced several variants that might partially evade current vaccines. The danger of newer variants persists with the next 150 million cases as the pandemic continues to rage in many nations which are just one airplane ride away. All human inhabitants of this blue-covered third rock from the sun are interconnected.

The benefits of scientific advancement have been extolled for centuries. This includes both individual discoveries as well as a mindset that favors rationalism over fatalism. On the whole, the benefits of scientific progress outweigh the negatives. Negative environmental impacts include pollution and climate change. Economic impacts include raising the mean economic standard of living but with greater inequity. Historically, governmental and social institutions have attempted to mitigate these negative consequences. Those efforts have attempted to provide guidance and a moral compass to direct the progress of scientific advancement, particularly in fields like gene therapy. Those efforts have called upon developed nations to share the bounties of progress with other nations.

Modern medicine has provided the fruit of these scientific advancements to a limited fraction of the world’s population during the 20th century. The improvements in life expectancy and infant mortality have come primarily from civil engineers getting running water into cities and sewage out. A smaller portion of the benefits are from public health measures that reduced tuberculosis, smallpox, polio, and measles. Agriculture became more reliable, productive, and nutritious. In the 21st century, medical care (control of hypertension, diabetes, and clotting) aimed at reducing heart disease and strokes have added another 2-3 years to the life expectancy in the United States, with much of that benefit erased by the epidemics of obesity and opioid abuse.